Jerry B. Jenkins's Blog, page 10

October 26, 2020

How to Overcome Writer’s Block Once and for All: My Surprising Solution

You well know the frustration.

It comes time to write, and you can’t produce a single word.

Maybe you’ve tried for weeks, months, or even years. But still nothing comes.

You’re suffering the dreaded Writer’s Block while your writing dream, your story, and the message you long to share with the world all collect dust in the attic of your mind.

If you don’t find a cure soon, you’re going to give up—and your story will never reach the masses like you hoped.

Good news! I’ve discovered how to crush Writer’s Block once and for all, and my more nearly 200 books, 21 of which have been New York Times bestsellers, prove it.

You don’t have to quit, and if you already have, you can change your mind and get back to writing.

So what’s my secret?

I treat Writer’s Block as the myth it is.

“Wait!” you’re saying. “Foul! If it’s a myth why am I suffering from it right now?”

Believe me, I know what you’re going through. I’m not saying I don’t have those days when I roll out of bed feeling I’d rather do anything but put words on the page.

But I know how to get unstuck.

During my career I’ve learned to turn on a faucet of creativity—even when, in fact especially when, I find myself staring at a blank page.

My approach stops Writer’s Block in its tracks, and it can do the same for you.

How can I call Writer’s Block a myth when you and countless others seem plagued by it?

Let’s think this through.

If Writer’s Block were real, why would it affect only writers? Imagine calling your boss and saying, “I can’t come in today. I have worker’s block.”

You’d be laughed off the phone! And you’d likely be told never to come in again.

No other profession accommodates block as an excuse to quit working, so we writers shouldn’t either.

If writing is just a hobby to you, a diversion, something you can take or leave, it shouldn’t surprise you that you find ways to avoid it when it’s hard.

What Is Writer’s Block? Something All Writers Need to Know…

What we call Writer’s Block is really a cover for something much deeper.

Identify that deeper issue and you can overcome Writer’s Block and finally start writing.

Overcoming Writer’s Block: Confronting the 4 Real Causes

Want a PDF of this guide to read whenever you wish? Click here.

Cause #1: Fear

Do you fear you’re not good enough?

That you don’t know enough?

Do you fear the competition? Editors? Writing itself?

You have big dreams and good intentions, but you can’t get past your fear?

Would you believe all of the above describes me too? Yes, even now, every time I begin a new book.

Let’s be honest: Writing a book is hard.The competition is vast and the odds are long.

That kind of fear can paralyze. Maybe it’s what has you stuck.

Solution

So how can I suffer from that same fear and yet publish all those titles?

Because I discovered something revolutionary: After failing so many times to overcome fear, it finally dawned on me—my fear is legitimate.

It’s justified. I ought to be afraid.

So now I embrace that fear! Rather than let it overwhelm and keep me from writing, I acknowledge the truth of what I’m afraid of and let that humble me.

Legitimate fear humbles me. That humility motivates me to work hard. And hard work leads to success.

That’s why fear doesn’t have to be a bad thing.

Better to fear you’re not good enough than to believe you’re great.

Dean Koontz, who has sold more than 450 million books, says:

“The best writing is borne of humility. The great stuff comes to life in those agonizing and exhilarating moments when writers become acutely aware of the limitations of their skills, for it is then that they strain the hardest to make use of the imperfect tools with which they must work.”

I’ve never been motivated by great amounts of money (not that I have anything against it!), but that quote comes from a man worth $145 million, earned solely from his writing.

How humble would you be if writing had netted you $145 million? Yet, humility is the attitude Dean Koontz takes to the keyboard every day.

If you’re afraid, fear the “limitations of your skills.” Then, “strain the hardest to make use of those imperfect tools with which you must work.”

That’s how to turn fear into humility, humility into motivation, motivation into hard work, and hard work into success.

Fear can be a great motivator.

Cause #2: Procrastination

Everywhere I teach, budding writers admit Procrastination is killing their dream.

When I tell them they’re talking to the king of procrastinators, their looks alone call me a liar.

But it’s true.

Most writers are masters at finding ways to put off writing. I could regale you for half a day with the ridiculous rituals I perform before I can start writing.

But my track record says I must have overcome Procrastination the way I have overcome Writer’s Block, right?

In a way, yes. But I haven’t defeated Procrastination by eliminating it. Rather, I have embraced it, accommodated it.

After years of stressing over Procrastination and even losing sleep over it, I finally concluded it was inevitable.

Regardless my resolve and constant turning over new leaves, it plagued me.

Solution

I came to see Procrastination as an asset.

I find that when I do get back to my keyboard after procrastinating, my subconscious has been working on my project. I’m often surprised at what I’m then able to produce.

So if Procrastination is both inevitable and an asset, I must accept it and even schedule it.

That’s right. When I’m scoping out my writing calendar for a new book, I decide on the number of pages I must finish each writing day to make my deadline. Then I actually schedule Procrastination days.

By accommodating Procrastination, I can both indulge in it and make my deadlines.

How?

By managing the number of pages I must finish per day.

If Procrastination steals one of my writing days, I have to adjust the number of pages for each day remaining.

So here’s the key: I never let my pages-per-day figure get out of hand.

It’s one thing to go from 5 or 6 pages a day to 7 or 8. But if I procrastinate to where now I have to finish 20 pages per day to make my deadline, that’s beyond my capacity.

Keep your deadline sacred and your number of pages per day workable, and you can manage Procrastination.

Cause #3: Perfectionism

Many writers struggle with Perfectionism, and while it can be a crippling time thief, it’s also a good trait during certain stages of the writing process.

Not wrestled into its proper place, however, Perfectionism can prove frustrating enough to make us want to quit altogether.

Yes, I’m a perfectionist too. I’m constantly tempted to revise my work until I’m happy with every word.

Solution

Separate your writing from your editing.

As I said, Perfectionism can be a good thing—at the right time.

While writing your first draft, take off your Perfectionist cap and turn off your internal editor.

Tell yourself you can return to that mode to your heart’s content while revising, but for now, just get your story or your thoughts down.

I know this is counterintuitive. When you spot an error, you want to fix it. Most of us do.

But start revising while writing and your production slows to a crawl.

You’ll find yourself retooling, editing, and rearranging the same phrases and passages until you’ve lost the momentum you need to get your ideas down.

Force yourself to keep these tasks separate and watch your daily production soar.

Cause #4: Distractions

It’s like clockwork.

Every time you sit down to write, something intrudes on your concentration.

Whether it’s a person, social media, or even a game on your phone, distractions lure you from writing.

Solution

How serious is your writing dream? If it remains your priority, It’s time to take a stand.

Establish these two ground rules to safeguard your work time:

Set a strict writing schedule.

Tell anyone who needs to know that aside from an emergency, you’re not available. That should eliminate friends and loved ones assuming “you’re not doing anything right now, so…”

It’s crucial you learn to say No. During your writing hours, you’re working.

Turn off all other media.

That means radio, TV, email, or social media.

When we feel stuck, our inclination is to break from the work and find something fun to occupy our minds.

That’s why Facebook, online shopping, and clickbait stories and pictures can keep us from writing.

When we should be bearing down and concentrating on solutions, we’re following links from the “10 Ugliest Actors of All Time” to “15 Sea Creatures So Ugly You Won’t Believe They Exist.”

Before you know it, your time has evaporated and you’ve accomplished nothing.

A Writer’s Block App I Recommend

To stay focused on writing, use a distraction-blocking app called Freedom. (This is an affiliate link, so I earn a small commission at no cost to you.)

Freedom allows you to schedule your writing time and blocks social media, browsing, and notifications on your devices till you’re done.

You set the parameters and can override it for emergencies, but it’s a powerful tool.

Other Strategies to Overcome Writer’s Block

1 — Just write.

You don’t get better at anything without practice. Writing is no different.

John Grisham established his writing routine long before he became famous. He got up early every morning and wrote for an hour before work.

“Write a page every day. That’s about 200 words, or 1,000 words a week. Do that for two years and you’ll have a novel that’s long enough. Nothing will happen until you are producing at least one page per day.”

2 — Lower your expectations.

You aren’t going to do your best writing every day. Show up anyway, do the necessary research, and write. Even when it’s not your best work.

“Never to sit down and imagine that you will achieve something magical and magnificent. I write a little bit, almost every day, and if it results in two or three or (on a good day) four good paragraphs, I consider myself a lucky man. Never try to be the hare. All hail the tortoise.” ― Malcolm Gladwell

3 — Get to know your characters.

Instead of focusing on the big picture, the late bestselling author Tom Clancy thought about his characters:

“ … and then I sit down and start typing and see what they will do. … It amazes me to find out, a few chapters later, why I put someone in a certain place when I did.”

4 ― Read.

Writers are readers. Good writers are good readers. Great writers are great readers.

Read at least 200 titles in your genre.

Read everything you can get your hands on.

It’ll help you grow in your craft and inspire you when you come up empty.

“If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write. Simple as that.” — Stephen King

“Read, read, read. Read everything — trash, classics, good and bad, and see how they do it. Just like a carpenter who works as an apprentice and studies the master. Read! You’ll absorb it. Then write. If it’s good, you’ll find out. If it’s not, throw it out of the window.” — William Faulkner

5 ― Give yourself a break.

Sometimes you need a break. Sometimes your best writing ideas come when you’re not in front of the computer.

“Plots come to me at such odd moments, when I am walking along the street, or examining a hat shop … suddenly a splendid idea comes into my head.” — Agatha Christie

“Some days all I do is stare at the wall. That can be productive, too, if you’re working out character and plot problems. The rest of the time, I walk around with the story slipping in and out of my thoughts.” — Suzanne Collins

6 ― Start at the end of your book.

John Grisham finds it helpful to begin at the end.

“Don’t write the first scene until you know the last scene. If you always know where you’re going, it’s hard to get lost.”

7 ― Brainstorm.

Set a timer and throw caution to the wind.

Think of ideas for a short story or novel.

Don’t worry about grammar, punctuation, or spelling.

Imagine great characters, names, traits, story settings, themes … anything that comes to mind.

All you need is the germ of an idea to start creating a story.

“Everybody walks past a thousand story ideas every day. The good writers are the ones who see five or six of them. Most people don’t see any.” — Orson Scott

8 ― Get a change of scenery.

While having a space set aside for writing is important, sometimes what you need is a change of scenery.

Write in a coffee shop, the park, get away for the weekend by yourself. That may be just what you need to get your creative juices flowing.

9 ― Stop while you’re ahead.

Ernest Hemingway loved to stop when he was on a roll.

“Always stop when you are going good and when you know what will happen next. If you do that every day … you will never be stuck. Don’t think about it or worry about it until you start to write the next day. That way your subconscious will work on it all the time. ”

Writer’s Block Quotes from Bestselling Authors

“Amateurs sit and wait for inspiration; the rest of us get up and go to work.” — Stephen King

“My cure for writer’s block? The necessity of earning a living.” — James Ellroy

“Writer’s block is just another name for fear.” — Jacob Nordby

“I don’t believe in writer’s block. Just pick up a pen and physically write.” — Natalie Goldberg

“If I waited till I felt like writing, I’d never write at all.” — Anne Tyler

“If you tell yourself you are going to be at your desk tomorrow, you are by that declaration asking your unconscious to prepare the material. ‘Count on me,’ you are saying: ‘I will be there to write.’” — Norman Mailer in The Spooky Art: Some Thoughts on Writing

“The secret to getting started is breaking your complex overwhelming tasks into small manageable tasks, and then starting on the first one.” — Mark Twain

“The wonderful thing about writing is that there is always a blank page waiting. The terrifying thing about writing is that there is always a blank page waiting.” ― J.K. Rowling

“I don’t sit around waiting for passion to strike me. I keep working steadily, because I believe it is our privilege as humans to keep making things. Most of all, I keep working because I trust that creativity is always trying to find me, even when I have lost sight of it.” ― Elizabeth Gilbert

“You can’t wait for inspiration. You have to go after it with a club.” ― Jack London

“What I try to do is write. I may write for two weeks ‘the cat sat on the mat, that is that, not a rat.’ And it might be just the most boring and awful stuff. But I try. When I’m writing, I write. And then it’s as if the muse is convinced that I’m serious and says, ‘Okay. Okay. I’ll come.’” — Maya Angelou

“It doesn’t really matter much if on a particular day I write beautiful and brilliant prose that will stick in the minds of my readers forever, because there’s a 90 percent chance I’m just gonna delete whatever I write anyway. I find this hugely liberating. I also like to remind myself of something my dad said in [response] to writers’ block: ‘Coal miners don’t get coal miners’ block.’” — John Green

“If I waited for perfection, I’d never write a word.” — Margaret Atwood

“Close the door. Write with no one looking over your shoulder. Don’t try to figure out what other people want to hear from you; figure out what you have to say. It’s the one and only thing you have to offer.” — Barbara Kingsolver

“Don’t waste time waiting for inspiration. Begin, and inspiration will find you.” — J. Jackson Brown, Jr.

“You can always edit a bad page. You can’t edit a blank page.” — Jodi Picoult

“I’ve often said that there’s no such thing as writer’s block; the problem is idea block. When I find myself frozen–whether I’m working on a brief passage in a novel or brainstorming about an entire book–it’s usually because I’m trying to shoehorn an idea into the passage or story where it has no place.” — Jeffrey Deaver

Click here for more inspiring writing quotes.

You Can Defeat Writer’s Block

Stand up to it the way you would a bully

See it for the myth it is

Turn your fear into humility and humility into hard work

That’s how to defeat Writer’s Block once and for all.

Want a PDF of this guide to read whenever you wish? Click here.

The post How to Overcome Writer’s Block Once and for All: My Surprising Solution appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

15 Daily Writing Exercises to Unblock You, Improve Your Craft, and Trigger Your Next Big Idea

Writing can be grueling.

Some days you feel you have what it takes.

Other days, you want to go back to bed.

Even after writing almost 200 books, including 21 New York Times bestsellers, some mornings the blank page just stares at me.

I feel like a fraud, fear I’ve lost it or never had it to begin with.

Can you relate? Few writers escape it. Not even the legends.

Hemingway wrote, “There’s no rule on how it is to write … Sometimes it comes easily and perfectly. Sometimes it is like drilling rock and then blasting it out with charges.”

Margaret Atwood says, “If I waited for perfection, I would never write a word.”

Yet fear holds back so many.

Am I good enough? Will I ever be?

You’re not alone. There’s no magic to successful writing. It’s all about hard work.

Even when you don’t have the energy.

Even when you’re second-guessing yourself.

All writing is rewriting, and you can’t rewrite a blank page.

So what to do?

Some writers motivate themselves with prompts or other exercises, just to start getting words onto the page. Might that work for you? Try these and see.

Here is a writing exercise for each day of the week, designed to keep you at the keyboard and producing.

Need help getting more words on the page when you write? Click here to download my free guide: How to Maximize Your Writing Time.

Daily Writing Exercises

1: Answer these Questions

See if these stimulate you.

Who just entered your office?

What is he or she carrying?

What does he or she want?

2: Write a Letter To Your Younger Self

Tap into your emotions and imagine this as a real, separate person you might be able to move with your words.

3: Imagine a Scene

An ex-love walks into a coffee shop but hasn’t yet noticed you. Should you greet them? What do you say to someone whose heart you broke five years ago?

You’re a child who’s been told Santa isn’t real. Write about your feelings and how you might interact with younger kids who still believe.

You find a peculiar device in your pocket and have no idea how it got there. You feel someone’s watching you. What do you do?

In fewer than 250 words, describe a defining moment in your life.

Write about how your character’s best friend’s body shows up in front of their house. What will they do to find out who’s responsible?

4: Write a Story Someone Once Told You

Exercise your storytelling muscles.

5: Write From a New Point of View

If you find yourself most often writing from the same perspective, try a different voice.

First-person (I, Me, My).

Second-person (You, Your). This POV is more common in non-fiction, rarely used by novelists .

Third-person limited (He, She). Common in commercial fiction, the narrator uses the main character as the camera.

Third-person omniscient. The narrator has access to the thoughts of ALL characters (not recommended except as a writing exercise).

6: Write About Someone Who Inspires You

a family member

a friend

a historical figure

a teacher

any hero of yours

Try writing a short story in first-person from their perspective.

7: Write About Someone You Know

With this exercise, you create a story with a lead character based on a family member, best friend, or anyone else you know well.

8: Free Write

Set a timer.

Write the first thing that comes to your mind.

No agenda, no filter. Ignore the urge to self edit, and don’t worry about grammar, punctuation, or spelling.

Just write.

9: Omit needless words

Find a piece you’ve written and edited but still needs work.

Ferociously excise every extraneous word and see if that doesn’t add power. This is a fun exercise that should be the hallmark of every writer.

10: Blog

Blogging is a great way to get yourself in the habit of writing regularly and sharing your work with an audience.

11. Analyze Your Favorite Book

Evaluate what kept you interested.

Favorite character? Why?

Setting?

Theme?

The writing style?

12: Create a Timeline of Significant Moments for Your Protagonist

The better you know your main character, the richer your story will be.

Go beyond birthdays, graduations, and anniversaries. Focus on events that make a real difference in her life and how you tell her story.

13: Write About Somewhere You’ve Been

Mine your memory for every sensory detail.

14: Use Writing Prompts for Practice

They’re all around you. In real life, in magazines, online lists, even six-word stories.

A writing prompt is simply a starting place. An idea.

The rest is up to you.

15: Write About Something You’re Good At

What’s your expertise? Write about it in detail.

16: Play Devil’s Advocate

Write a strong argument for the other side of an issue about which you’re passionate.

These exercises should get you unstuck and writing like never before.

Need help getting more words on the page when you write? Click here to download my free guide: How to Maximize Your Writing Time.

The post 15 Daily Writing Exercises to Unblock You, Improve Your Craft, and Trigger Your Next Big Idea appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

October 19, 2020

How to Start a Story: 4 Proven Tips

Acquisitions editors and agents can reject some manuscripts within the first two pages.

If they aren’t hooked immediately, they move on. That doesn’t sound fair — and maybe it isn’t — but that’s the reality we writers face.

Even if you’re self-publishing and avoiding the harsh glare of professional eyes, rivet your readers from the get-go or most will close your book without a second thought.

Novelist Les Edgerton started a short story this way:

He was so mean that wherever he was standing became the bad part of town.

I’d keep reading, wouldn’t you?

How to Start a Story

As a novelist, you owe your reader certain things from page one.

By investing in your novel, your reader tacitly agrees to willingly suspend disbelief and trust you to provide entertainment, inspiration, or education — and sometimes all three.

In exchange, the reader expects

to be treated with intelligence, not spoon fed everything

to participate in the journey of discovery

you to conform the conventions of your genre

So set the tone of your novel early and stick to it.

Whether your opening scene is funny or serious, the rest should follow suit.

The first few paragraphs serve as your calling card not only to readers but also to the potential agents or acquisitions editors who precede them.

To help you develop a strong beginning and get out of the way so your readers can, as Canadian author Lisa Moore puts it, begin to create your story in their head:

1. Begin in medias res.

That’s Latin for “in the midst of things.” It doesn’t have to be slam-bang action, unless that fits your genre. But start with something happening. Give the reader the sense he’s in the middle of something.

Don’t waste your opener (the highest price real estate in your manuscript) on backstory or setting or description. Layer these in as the story progresses. Get to the good stuff.

2. Introduce your main character early, by name.

One of the biggest mistakes you can make is to introduce your main character too late. ()

As a rule, he* should be the first person on stage.

[*I use he inclusively to refer to both genders.]

Work in enough details to get readers to care what happens to him. Is he a spouse, a parent, troubled, worried, hopeful? Then get to the problem, the quest, the challenge, the danger—whatever will drive your story.

3. Don’t describe; layer in.

We’ve all been sent napping by an opening scene that began something like:

The house sat in a deep wood surrounded by…

Don’t.

Rather than describing the setting as a separate element, make it part of your story. This way the reader subconsciously becomes aware of it while you’re focusing on the plot itself — what’s happening.

For example, instead of:

The house sat in a deep wood surrounded by… (Description as a separate element.)

Try this:

Wondering what could be so urgent that he had to meet Tim in the middle of the night, Fred pulled deep into the woods on an unpaved road and came upon… (Layering in the details.)

4. Show, Don’t Tell

Not: She could tell he had been smoking and that he was scared. (Telling)

Rather: She wrapped her arms around him and smelled tobacco. He shivered. (Showing)

Layered in as part of the action, what things look and feel and smell and sound like register in the theater of your readers’ minds, while they’re concentrating on the action, the dialogue, the tension and drama and conflict that keeps them turning those pages.

That way, you can subtly work in all the details they need to get the full picture and enjoy the experience.

5. Find your distinct writing voice.

This isn’t as complicated as it sounds.

Put simply, your writing voice is you.

It reveals on the page your distinct…

Personality

Character

Passion

Emotion

Purpose

Imagine saying to your best friend, “Have I got something to tell you…”

What comes next will be in your most passionate voice.

You at your most engaged is the voice you want on the page.

That’s what your writing voice should sound like.

To use it in fiction, give that voice to your perspective character.

Remember, the goal of your opener is to leave your reader with no choice but to turn the page.

4 Types of Lines You

Can Use to Start Your Story

1. Surprise

Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice. —Gabriel Garcia Marquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967)

It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen. —George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not. —Paul Auster, City of Glass (1985)

It was the day my grandmother exploded. —Iain M. Banks, The Crow Road (1992)

High, high above the North Pole, on the first day of 1969, two professors of English Literature approached each other at a combined velocity of 1200 miles per hour. —David Lodge, Changing Places (1975)

A screaming comes across the sky. —Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow (1973)

It was a pleasure to burn. —Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451 (1953)

As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect. —Franz Kafka, The Metamorphosis (1915)

I write this sitting in the kitchen sink. —Dodie Smith, I Capture the Castle (1948)

2. Dramatic Statement

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. —Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita (1955)

I am an invisible man. —Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952)

“He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty-four days now without taking a fish.” —Ernest Hemingway, The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

Someone must have slandered Josef K., for one morning, without having done anything truly wrong, he was arrested. —Franz Kafka, The Trial (1925)

They shoot the white girl first. —Toni Morrison, Paradise (1998)

You better not never tell nobody but God. —Alice Walker, The Color Purple (1982)

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair. —Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

3. Philosophical

Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. —Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina (1877)

This is the saddest story I have ever heard. —Ford Madox Ford, The Good Soldier (1915)

The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there. —L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between (1953)

Of all the things that drive men to sea, the most common disaster, I’ve come to learn, is women. —Charles Johnson, Middle Passage (1990)

Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show. —Charles Dickens, David Copperfield (1850)

4. Poetic

When I finally caught up with Abraham Trahearne, he was drinking beer with an alcoholic bulldog named Fireball Roberts in a ramshackle joint just outside of Sonoma, California, drinking the heart right out of a fine spring afternoon. —James Crumley, The Last Good Kiss (1978)

It was just noon that Sunday morning when the sheriff reached the jail with Lucas Beauchamp though the whole town (the whole county too for that matter) had known since the night before that Lucas had killed a white man. —William Faulkner, Intruder in the Dust (1948)

Writing A Great Opening Line

Is Only the Beginning

It’s your job to keep the reader with you.

So study storytelling, create compelling characters, and become a ferocious self-editor.

The post How to Start a Story: 4 Proven Tips appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

October 6, 2020

8 Types of Characters to Include in Your Story

Why do we remember characters like Huckleberry Finn, Oliver Twist, Frodo Baggins, and Harry Potter years after we meet them?

Page-turning novels feature believable characters with human flaws, people who grow heroic in the end.

So how do you conjure up characters like that?

First, it pays to understand the basic types of characters that exist in a story and the roles they play.

Types of Characters in a Story

1. Protagonist

Your main character or hero is, naturally, the essential player. He* is your focus, the person you want readers to invest in and care about.

(*I use the pronoun “he” inclusively to represent both genders, male and female.*)

He’s the center of attention.

He drives the plot, pursues the goal, changes and grows as your story progresses.

He must possess:

redeemable human foibles

potentially heroic qualities that emerge in the climax

a character arc (becoming a different, better, stronger person by the end)

Resist the temptation to create a perfect lead character.

Perfect is boring. (Even Indiana Jones was afraid of snakes.)

No protagonist, no story, so develop this character first.

Get him on stage early, introduce him by name, and immediately start layering in personal details that give readers reasons to care about what happens to him.

Protagonist examples:

Romeo and Juliet in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet

Elizabeth Bennet in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice

Dorothy in L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Wilbur in E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web

Jack Ryan and Marko Ramius in Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October

Katniss Everdeen in Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games

2. Antagonist

This is the villain, the character who opposes and undermines your protagonist.

The more formidable your antagonist, the more compelling your hero.

The antagonist must:

have a realistic and sympathetic backstory

exhibit power

force the protagonist to make difficult choices

cause the protagonist to grow

Be careful not to make the villain bad just because he’s the bad guy.

Make him a worthy foe by giving him realistic, believable motives.

The most compelling villains have had bad things happen to them.

They don’t see themselves as bad. They see themselves as justified.

Antagonist examples:

Lord Voldemort in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series

Mayor Larry Vaughn in Peter Benchley’s Jaws

Mr. Darcy in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice

President Coriolanus Snow in Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games

Professor James Moriarty in many of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes mysteries

3. Sidekick

The character second in importance to the protagonist, not all sidekicks support the protagonist.

Some switch back and forth, hindering him. Others turn out to be the villain.

But most often, the sidekick is a friend who supports the protagonist, offering advice, adding depth to the story.

Sidekick examples:

Dr. John Watson in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes

Runaway slave Jim in Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Samwise Gamgee in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings series

Iago from Shakespeare’s Othello

4. Orbital Character

Third in importance behind the protagonist and the sidekick, this character is usually an instigator, causing trouble for the protagonist and giving him plenty of opportunity to shine.

Sometimes he also turns out to be the antagonist.

Orbital Character examples:

Tom Sawyer in Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Hermione in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series

Princess Leia and Han Solo in George Lucas’s Star Wars

Khan in Star Trek

5. Love Interest

The object of your protagonist’s deepest affection often serves as a prize, but she could also function as an obstacle to attaining his goal.

Rendered well, the love interest reveals the main character’s strengths and vulnerabilities.

But be careful.

As with your main character, a too perfect love interest will fall flat and come off unrealistic.

Love Interest examples:

Rhett Butler in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind

Peeta in Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games

Mr. Darcy in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice

Daisy in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby

6. Confidante

The character in whom the protagonist trusts the most is often a best friend, a love interest, or a mentor. But sometimes he can be an unlikely character.

The confidante is an essential tool through whom your protagonist’s thoughts and feelings are revealed.

Confidante examples:

Samwise Gamgee in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings series

Albus Dumbledore and Hermione in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series

Horatio in Shakespeare’s Hamlet

Cinna in Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games

7. Extras

You’ll likely need Central Casting-type characters for specific, limited purposes.

These are background characters who come and go, but they often lend meaning to the story.

So be careful not to make clichés of them.

These are people your main character encounters, like the repairman, a clerk, a teller, a waiter, or someone he sits next to on a bus.

Extras examples:

Madame Stahl in Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina

Radagast in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings

Parvati and Padma Patil in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter

8. Foil

Like the villain, this is an opposite of the protagonist, highlighting his strengths.

But the foil isn’t usually the antagonist. Rather, he exposes things about your protagonist you want more sharply focused, while the antagonist is his enemy.

Foil examples:

Effie Trinket to Katniss Everdeen in Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games

Draco Malfoy to Harry Potter in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series

Dr. John Watson to Sherlock Holmes in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes

You Can Do This

Remember, you may only use one or two types of characters from this list.

Next time you watch a Netflix series or read a novel, try identifying the different types of characters in the story.

The protagonist should be easy, but some others can be a fun challenge.

Other helpful blog posts on character development:

Your Ultimate Guide to Character Development: 9 Steps to Creating Memorable Heroes

Character Motivation: How to Craft Realistic Characters

How to Create a Powerful Character Arc

12 Character Archetypes You Can Use to Create Heroes Your Reader Will Love

The post 8 Types of Characters to Include in Your Story appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

August 28, 2020

The 7 Main Story Elements and Why They Matter

You’ve got a story idea you’re certain has the potential to impact lives.

Where do you start?

There’s enough writing advice on the internet to overwhelm you and make you want to quit before you even begin.

So let’s simplify things.

Writing a story is like building a house. You may have all the tools and design ideas, but if your foundation isn’t solid, even the most beautiful structure won’t stand.

Most storytelling experts agree that 7 key elements must exist in your story.

Make sure they’re all included to boost your chance of selling your writing.

What are the Elements of a Story?

Effective, compelling stories contain:

1 — A Theme

Plot (#5) is what happens in a story, a theme is why it happens—which you need to know while you’re writing the plot.

So, before you even begin writing, determine why you want to tell this story.

What message do you wish to convey?

What will it teach the reader about life?

Resist the urge to explicitly state your theme. Just tell your story and let it explore your theme and make its own point.

Give your readers some credit, they’re smart. Subtly weave it into the story and trust them to get it. Don’t rob them of their part of the writing/reading experience.

They may remember your plot, but ideally you want them to think long about your theme.

2 — Characters

I’m talking believable characters who feel knowable.

Your main character is the protagonist, also known as the lead or hero/heroine.

The protagonist must have:

redeemable human flaws

potentially heroic qualities that emerge in the climax

a character arc (he must be a different, better, stronger person by the end)

Resist the temptation to create a perfect lead character. Perfect is boring. (Even Indiana Jones suffered a snake phobia.)

You also need an antagonist, the villain.

Your villain should be every bit as formidable and compelling as your hero. Just don’t make the bad guy bad because he’s the bad guy. Make him a worthy foe by giving him motives for his actions.

Villains don’t see themselves as bad. They think they’re right! A fully rounded bad guy is much more realistic and memorable.

Depending on the length of your story, you may also need important orbital cast members.

For each, ask:

What do they want?

What or who is keeping them from getting it?

What will they do about it?

The more challenges your characters face, the more relatable they are.

Much as in real life, the toughest challenges transform the most.

3 — Setting

This may include location, time, or era, but it should also include how things look, smell, taste, feel, and sound.

Thoroughly research details about your setting, but remember this is the seasoning, not the main course. The main course is the story itself.

But, beware. Agents and acquisitions editors tell me one of the biggest mistakes beginning writers make is feeling they must begin by describing the setting.

It’s important, don’t get me wrong. But a sure way to put readers to sleep is to promise a thrilling story on the cover—only to begin with some variation of:

The house sat in a deep wood surrounded by…

Don’t.

Rather than describing the setting, subtly layer it into your story.

Show readers your setting, don’t tell them.

Do this, and what things look and feel and sound like subtly register in the theater of the readers’ minds while they’re concentrating on the action, the dialogue, the tension, the drama, and conflict that keep them turning the pages.

4 — Point of View

To determine Point of View (POV) for your story, decide two things:

the voice you will use to write your story: First Person (I, me), Second Person (you, your), or Third Person (he, she or it), and

who will serve as your story’s camera?

The cardinal rule is one perspective character per scene, but I prefer only one per chapter, and ideally one per novel.

Readers experience everything in your story from this character’s perspective. (No hopping into the heads of other characters.) What your POV character sees, hears, touches, smells, tastes, and thinks is all you can convey.

Some writers think this limits them to First Person, but it doesn’t.

Most novels are written in Third Person Limited: one perspective character at a time, usually the one with the most at stake.

Writing your novel in First Person makes it easiest to limit yourself to that one perspective character, but Third-Person Limited is most popular for a reason.

Read current popular fiction to see how the bestsellers do it.

Point of View can be confusing, but it’s foundational. Overlook it at your peril.

5 — Plot

Plot is the sequence of events that make up a story. It’s what compels your reader to either keep turning the pages, or set the book aside.

Think of plot as the storyline of your novel.

A successful story answers two questions:

What happens? (Plot)

What does it mean? (Theme; see #1 above—it’s foundational)

Writing coaches call story structures by different names, but they’re all largely similar. All story structures include some variation of:

An Opener

An Inciting Incident that changes everything

A series of crises that build tension

A Climax

A Resolution (or Conclusion)

How effectively you create drama, intrigue, conflict, and tension, determines whether you can grab readers from the start and keep them to the end.

6 — Conflict

Conflict is the engine of fiction and is crucial to effective nonfiction as well.

Readers crave conflict and long to see what results from it.

If everything in your plot is going well and everyone is agreeing, you’ll quickly bore your reader—a cardinal sin.

Are two characters chatting amiably?

Have one say something that makes the other storm out, revealing a deep-seeded rift in their relationship.

What is it? What’s behind it? Readers will keep turning the pages to find out.

7 — Resolution

Whether you’re an Outliner or a Pantser like me (one who writes by the seat of your pants), you must have an idea where your story is going and think about your ending every day.

How you expect the story to end should inform every scene and chapter. It may change, evolve, grow as you and your characters experience the inevitable arcs, but never leave it to chance.

Keep your lead character center stage to the very end. Everything he learns through all the complications that arise from his trying to fix the terrible trouble you plunged him into should, in the end, make him rise to the occasion.

If you get near the end and feel something’s missing, don’t rush. Give it a few days, a few weeks if necessary.

Read through everything you’ve written. Take a long walk. Think on it. Sleep on it. Jot notes about it. Let your subconscious work on it. Play what-if games. Be outrageous if you must. But deliver a satisfying ending that resonates.

Give your readers a payoff for their investment by making it unforgettable. Do this by reaching for the heart.

Readers love to be educated and even entertained, but they never forget being emotionally moved.

You Can Do This

Focus on these 7 story elements, and when you’re ready to dig deeper, click here to read my 12-step process for How to Write a Novel.

The post The 7 Main Story Elements and Why They Matter appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

August 21, 2020

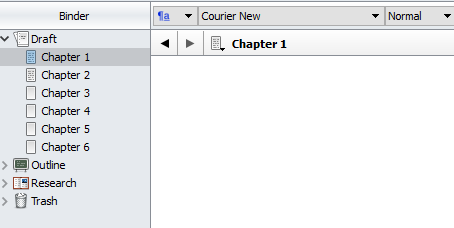

Scrivener Review: Is It For You?

Writing a book can be an organizational nightmare.

You find yourself scribbling ideas, scenes, research notes, you name it, on napkins, in notebooks, on sticky pads, or keyboarding stuff into files you can’t find later on your computer.

What if you could keep ALL that stuff, even photos and graphs and charts, all in one place?

Enter Scrivener.

This book writing software calls itself the ultimate organization tool for writers.

So, is it? Could it be just the thing you’ve been looking for?

Let me cover its benefits, features, and pros and cons so you can decide.

(Note: If you click on a link herein to purchase Scrivener, I get a small commission at no cost to you.)

What is Scrivener?

Scrivener is book writing software developed more than a dozen years ago by an aspiring author frustrated with trying to keep his notes organized.

The result was a word-processing tool similar to Microsoft Word with the organization capabilities of a tool like Evernote.

How Much Does Scrivener Cost?

It varies depending on your system:

Mac OS: $49

Windows: $45

iOS (iPad): $19.99

These are one-time payments, but you do have to purchase separate licenses if you want it on both your computer and tablet/phone.

Pros and Cons

PROS

30-day free trial: Before you purchase Scrivener, a free 30-day trial gives you access to all its features.

Free templates: Scrivener takes into account that not all writers need the same type of help. A screenwriter requires something different from a poet, etc., so you can choose from among dozens of templates.

Personalized setup and interfaces: Scrivener allows you to customize many of its features to suit your needs.

Key features for all stages of the writing process

Support: Scrivener includes tutorials to walk you through its features.

CONS:

Licenses for each platform: If you work on both a Mac and a Windows computer, you would have to buy a license for each.

Steep learning curve: Even its most enthusiastic supporters admit it takes time to master Scrivener’s many features.

Key Features

Binders

This sidebar on the left side of your screen keeps chapters, notes, and research in one place.

You can create as many folders as you like, even folders inside of folders, along with images, documents, and notes.

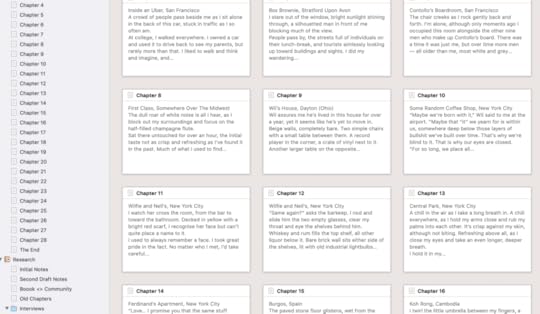

The Cork Board

Scrivener’s Cork Board takes what appears in your Binder and lays it out like sticky notes on a wall. You can move these around as you wish.

Templates

A nonfiction author will lay out their project differently from a novelist. Scrivener provides free templates to choose from.

It also allows you to import third-party templates (hundreds available online).

Project Goals and Targets

Scrivener allows you to set targets and goals for your project, prompting you with how you’re doing. You can also set targets for individual writing sessions and track your progress with the “Writing History” feature.

Color Coding

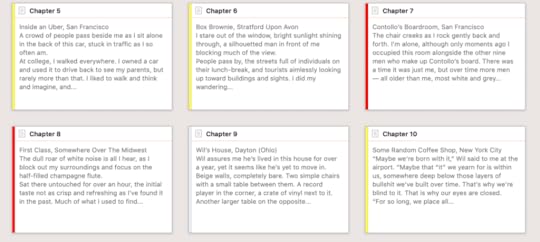

To help keep you on track, Scrivener allows you to color code its various elements.

From chapters and scenes to research and notes, you can customize labels to represent chapters still in outline form, in draft stage, or complete.

Distraction Free Mode

Scrivener has so many features that this can become distracting. Their “Distraction Free Mode” allows the user to focus on only one thing at a time.

You can customize the page to feature notes or images or copy you want to work with, while removing anything you don’t need.

Statistics

As well as tracking word count, Scrivener allows you to also monitor everything from character count, average sentence length, and even how often you use a certain word.

When editing your work, you can analyze individual documents or chapters.

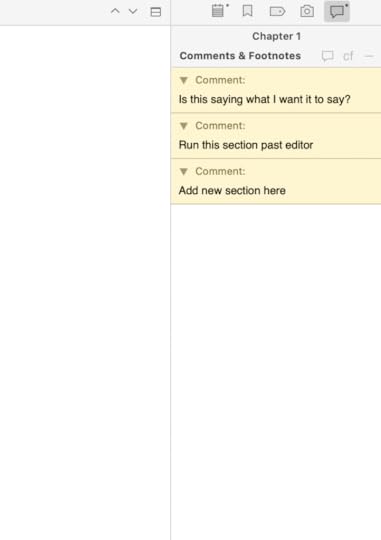

The Inspector Tool

In addition to the Binder Feature, you can also open a customizable inspector in the right-hand sidebar of your page where you can add notes, comments, pictures, and keywords.

Some Scrivener users find this feature distracting, but others find it helpful during the revision phase.

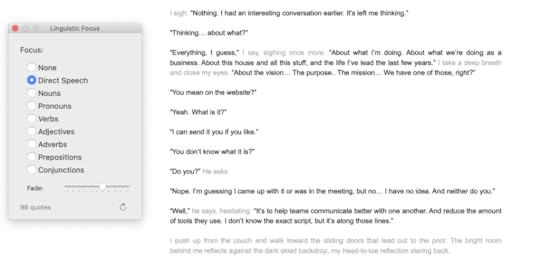

Linguistic Focus

This is a new feature in Scrivener 3, highlighting certain sections of your text. You can use this to home in on your dialogue or your use of adjectives, adverbs, and pronouns.

AutoSave

This common feature in book writing software solves a writer’s worst nightmare—your computer crashing before saving your work.

Scrivener auto-saves your work as you write.

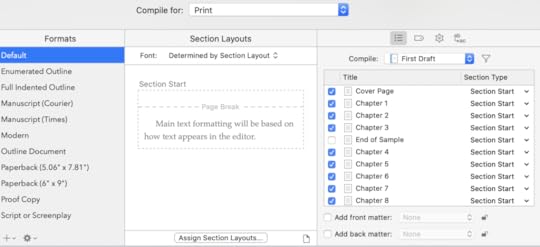

Publish To Almost Any Format

Finally, Scrivener allows self-publishing writers to export or print manuscripts into almost any format. You can save your project for paperback, hardcover, and eBook without having to create separate documents for each.

Scrivener Alternatives

Bibisco

COST: Pay what you want

PROS:

Autosaves your work

Drag and drop feature allows you to rearrange your chapters

The ability to create character and settings lists

CONS:

No mobile or tablet version

Limitations on exports (PDF and .doc only)

Some say the software feels outdated

Bibisco was created with novelists in mind, and its features help you research your book and stay organized.

The Novel Factory

COST: from $39.99

PROS:

Customizable story templates

Tools to help create and research characters

Autosaves your work

CONS:

Importing previous drafts is time consuming

Available Only for PC

Some find the software less intuitive than Scrivener

Campfire Pro

COST: from $49.99

PROS:

Easy to use

The ability to import and export characters

Worldbuilding features

CONS:

Standard version offers limited features

No built-in word processor, so you’ll need other software to accompany Campfire Pro

Some features are too complex

Campfire Pro is designed to help you plan and research your book. It isn’t a word processor like Scrivener.

Scrivener Review: Verdict

Many of my widely-published colleagues swear by Scrivener, though they admit it comes with a steep learning curve. I personally use it mostly for managing my research. I still use Word to actually write my manuscripts.

If you’re willing to invest the time to master this powerful tool, it could well be worth its modest price.

Click here to check out Scrivener.

The post Scrivener Review: Is It For You? appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

August 13, 2020

Grammarly Review: Is Premium Worth It?

The wrong word choice or even a spelling mistake can turn off your reader.

So I hope you’re rereading and editing everything you write.

A tool like Grammarly can help.

(Note: this post contains affiliate links. If you click to purchase Grammarly, I get a small commission at no extra cost to you.)

What is Grammarly and What Does it Do?

Grammarly helps you check and edit your work.

It’s an app (or web browser extension) you can use wherever you are on the internet. It even has a desktop extension you can use with Word, which is the writing software on which the publishing industry runs.

Grammarly spots spelling errors, highlights grammar issues, and offers suggestions to help you remove passive language, redundant words, or complex sentences. It helps you revise emails, messages, and manuscripts before you submit them to agents or publishers. .

Is Grammarly For You?

It can be, because it offers a quick overview of issues you can self-edit. Grammarly isn’t a replacement for you as a ferocious self-editor.

Grammarly Key Features

Many features are available free, while the rest are exclusive to its Premium version.

Grammarly’s core features:

Spelling and Grammar Check

Writing Style Evaluator

Plagiarism Detector

Suggestions

1: Spelling and Grammar Check

Grammarly automatically checks everything you write for spelling, grammar, and punctuation errors. It underlines these in red and offers suggestions on what you should change.

This fundamental feature is available in both Grammarly’s Free and Premium versions.

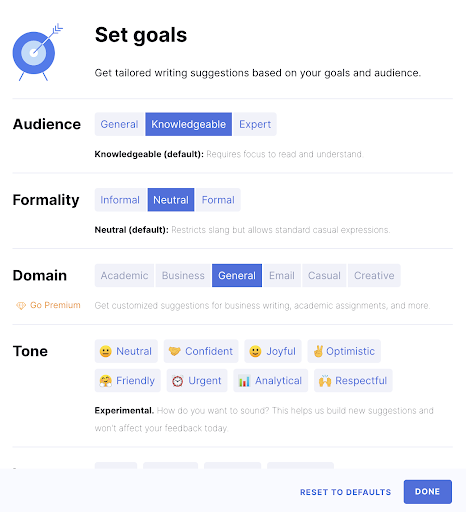

2: Writing Style Evaluator

Grammarly advises you on tone, readability, vocabulary, and even how formal your writing is.

Grammarly helps you home in on this, advising on sentence length, word choice, and language.

You can alter this in Settings, based on your specific needs.

Some aspects of this appear in the Free version, but most is reserved for Grammarly Premium.

3: Plagiarism Detector

Not all plagiarism is intentional, so Grammarly can help you avoid such a pitfall.

4: Grammarly Suggestions

This helps catch spelling mistakes and punctuation errors, and you have the option to accept or ignore these.

Grammarly Price

The Free version gives you access to spelling, grammar, and punctuation. The Premium version adds Fluency, Readability, Word choice, Plagiarism detection, Inclusive language, Formality level, and additional advanced corrections.

Currently, the Premium version is $11.66 a month if you pay annually (a 61% discount). Otherwise it’s $59.95 per quarter (a 33% discount) or 29.95 a month.

So, is Grammarly Premium worth it?

Grammarly Free vs. Premium

Grammarly Free is probably all you need. It gives you the essentials.

With a free version, Grammarly can help keep your work free of obvious mistakes.

Grammarly Pros and Cons

PRO 1: Easy To Use

You don’t have to be experienced with a computer to use Grammarly. Once installed, it works in the background whenever you write.

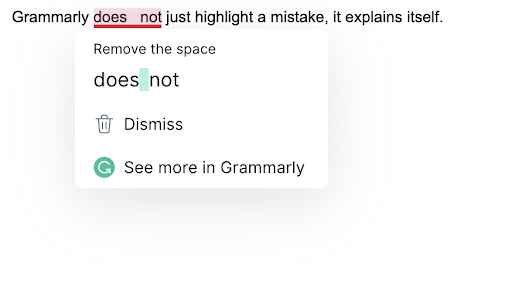

PRO 2: Real-Time Corrections and Suggestions

As soon as you’ve spelled a word wrong or used a word wrong, Grammarly notifies you.

PRO 3: Easy To Understand

Grammarly explains itself when suggesting a change.

In the example above, Grammarly suggests removing the space between does and not. You can also “see more in Grammarly.”

CON 1: Aggressive Marketing

Grammarly wants you to upgrade to Premium, so you’ll notice ads, emails, call to actions, and up-sell messages.

CON 2: It Doesn’t Replace You

As helpful as Grammarly can be, some writers think they can break from so much self-editing. They’re wrong.

Grammarly Alternatives

ProWritingAid

ProWritingAid, like Grammarly, checks spelling and grammar but also helps tighten your writing by checking for style, cliches, overused words, or complex sentences.

Its annual subscription price ranges between $60-70.

Ginger

Offers many of the same features as Grammarly, but can translate your work in 60 languages. It starts at $89.88 per year.

Whitesmoke

Offers many of the same features as Grammarly (as well as a translation tool similar to Ginger). Its annual subscription starts at $59.95.

You can upgrade to its premium service for $79.95.

Is Grammarly Premium Worth It?

All writing is rewriting, so a tool like Grammarly can help you tighten your writing.

But the features you really need are available in Grammarly’s free version.

The post Grammarly Review: Is Premium Worth It? appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

August 7, 2020

The Hero’s Journey: A Classic Story Structure

Writing a compelling story, especially if you’re new at this, can be grueling.

Conflicting advice online can overwhelm you, making you want to quit before you’ve written a word.

But you know more than you think.

Stories saturate our lives. We talk, think, and communicate with story in music, on television, in video games, in books, and in movies.

Every story, regardless of genre or plot, features a main character who begins some adventure or quest, overcomes obstacles, and is transformed.

This is generically referred to as The Hero’s Journey, a broad story template popularized by Joseph Campbell in his The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949).

In essence, every story ever told includes at least some of the seventeen stages he outlined.

In 1985, screenwriter Christopher Vogler wrote a memo for Disney titled The Practical Guide to Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces that condensed the seventeen steps to twelve.

The Hero’s Journey template has influenced storytellers worldwide, most notably George Lucas (creator of Star Wars and Indiana Jones).

Vogler says of Campbell’s writings: “The ideas are older than the pyramids, older than Stonehenge, older than the earliest cave painting.”

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins is a prime example of The Hero’s Journey, so I use “she” inclusively to represent both genders.

The 3 Hero’s Journey Stages

1. The Departure (Separation)

The hero is compelled to leave her ordinary world.

She may have misgivings about this compulsion, and this is where a mentor may come to encourage and guide her.

Example: Katniss Everdeen is a devoted sister, daughter, and friend. She’s an avid hunter, well acquainted with the forbidden forest outside District 12, where she and her friend Gale hunt to keep their families from starving. The Hunger Games, wherein only one winner survives, loom, and she fears she or one of her friends will be chosen.

2. Initiation

The hero crosses into the other world, where she faces obstacles.

Sometimes she’s alone, sometimes she’s joined by a companion. Maybe a few.

Here she must use the tools she’s been given in her ordinary life to overcome each obstacle. She’ll be rewarded, sometimes tangibly.

Eventually she must return to the ordinary world with her reward.

Example: District 12’s Representative and Stylist Effie Trinket arrives to choose the Tributes who will compete in The Hunger Games.

Katniss and her family attend, and she breathlessly wills Effie not to draw her name. She gets her wish, but to her horror, her little sister Primrose is chosen.

Peacekeepers shove Prim toward the stage before Katniss volunteers to take her place. She’s joined by the male tribute, the baker’s son Peeta. They are soon whisked away for training and then the competition.

3. Return

The hero crosses the threshold back into her ordinary world, which looks different now. She brings with her the rewards and uses them for good.

Example: Unexpectedly, Katniss and Peeta are told there can be two victors instead of one. But Katniss and Peeta, to the dismay of the Capitol, decide they’ll die together or emerge as victors together. They emerge not only as victors, but also as celebrities. They have changed in unimaginable ways.

The 12 Hero’s Journey Steps (and How to Use Them)

Departure

1 — Ordinary World

Before your hero is transported to another world, we want to see her in her ordinary world—who is she when no one is watching? What drives her?

This sets the stage for the rest of your story, so show her human side. Make her real and knowable.

But don’t wait long to plunge her into terrible trouble. Once you give your readers a reason to care, give them more to keep them turning the pages.

Example: Katniss Everdeen is introduced as a teenager for whom life isn’t easy. Her father is dead, her mother depressed, and Katniss will do anything to provide for her family and protect her little sister.

2 — The Call to Adventure

This is the point at which your hero’s world can never be the same. A problem, a challenge, or an adventure arises—is she up to the challenge?

Example: The Reaping, where Katniss volunteers to take Prim’s place.

3 — Refusal of the Call

Occasionally, a hero screeches to a halt before the adventure begins. When faced with adversity, she hesitates, unsure of herself.

She must face her greatest fears and forge ahead.

Example: There is no refusal of the call in The Hunger Games. Katniss eagerly steps forward.

4 — Meeting With the Mentor

The mentor may be an older individual who offers wisdom, a friend, or even an object, like a letter or map.

Whatever the form, the mentor gives your hero the tools she needs for the journey—either by inspiring her, or pushing her in the direction she needs to go.

Example: Katniss is introduced to Haymitch the minute she reaches the stage to accept the challenge. He’s the only person from District 12 to have ever won The Hunger Games. She’s not initially impressed, but he eventually becomes her biggest ally.

5 — Crossing the First Threshold

In the final step of the departure phase, your hero musters the courage to forge ahead, and the real adventure begins.

There’s no turning back.

By now, you’ve introduced your hero and given your readers a reason to care what happens to her. You should have also introduced the underlying theme of your story.

Why is it important for your hero to accomplish this task?

What are the stakes?

What drives her?

Example: Katniss is transported via train to the Capitol to begin training for The Hunger Games. She’s promised Prim she’ll do everything in her power to return home.

Initiation

Your hero is laser focused, but this is the point at which she faces her first obstacle. She will meet her enemies and be forced to build alliances. She will be tested and challenged.

Can she do it?

What does she learn in this initiation phase?

Example: Katniss meets her competitors for the first time during training and is able to watch them to get a sense of what challenges lie ahead.

6 — Tests, Allies, and Enemies

Things have shifted in the new world. Danger lies ahead. Alliances are formed, chaos ensues.

Your hero may fail tests she’s confronted with at first, but her transformation begins. She has the ability and knowledge to accomplish her tasks, but will she succeed?

Example: The Hunger Games begin. Tributes die. Katniss fights without water or a weapon. Her allies are Peeta and young Rue (the 12-year-old Tribute from District 11). The strongest players have illegally spent their young lives training for The Hunger Games and loom as her enemies from the start.

7 — Approach to the Inmost Cave

Your hero approaches danger—often hidden, sometimes more mental than physical. She must face her greatest fears time again and may even be tempted to give up. She has to dig deep to find courage.

Example: Katniss is in the arena, the games underway. There’s no escape. She’s seen death, fears she may be next, and must find water and a weapon to survive.

8 — The Ordeal

Your hero’s darkest moment and greatest challenge so far, in a fight for her life, she must find a way to endure to the end.

This may or may not be the climax of your story, but it is the climax of the initiation stage.

During this terrible ordeal, the steepest part of her character arc takes place.

Example: Katniss faces dying of thirst (if she’s not killed by another Tribute first) and faces every obstacle imaginable, including the death of Rue, before she finally wins the battle.

9 — Reward (Seizing the Sword)

Against all odds, your hero survives. She’s defeated her enemies, slain her dragons—she has overcome and won the reward.

Whether her reward is tangible depends on the story. Regardless, your hero has undergone a total inward and outward transformation.

Example: Peeta and Katniss stand alone in the arena, told that because they are from the same district they can both claim the victory—or can they?

Return

10 — The Road Back

As she begins to cross the threshold back into the ordinary world, she learns the battle isn’t finished.

She must face the consequences for her actions during the initiation stage.

She’s about to face her final obstacle.

Example: The Capitol reverses and announces that only one winner will be allowed.

11 — The Resurrection

During this climax of your story, your hero faces her final, most threatening challenge.

She may even face death one more time.

Example: Katniss and Peeta decide that if they can’t win together, there will be no winner. They decide to call the Capitol’s bluff and threaten to die together. As they are about to eat poison berries, the Capitol is forced to allow two winners.

12 — Return With the Elixir

Your hero finally crosses the threshold back into her ordinary life, triumphant. Only things aren’t so ordinary anymore.

She’s been changed by her adventure. She brings with her rewards, sometimes tangible items she can share, sometimes insight or wisdom. Regardless, this all impacts her life in ways she never imagined.

Example: Katniss and Peeta return home celebrities. They’re given new homes, plenty of food to share, and assistants who tend to their needs. Katniss learns that her defiance of the Capitol has sparked a revolution in the hearts of residents all across Panem.

Hero’s Journey Examples

You may recognize The Hero’s Journey in many famous stories, including Greek Mythology and even the Bible. Other examples:

Sleeping Beauty

Star Wars

Lord of the Rings

The Hobbit

Indiana Jones

Sherlock Holmes

Jane Eyre

Pilgrim’s Progress

The Wizard of Oz

Toy Story

Should You Use The Hero’s Journey Story Structure?

Structure is necessary to a story, regardless which you choose. Because the Hero’s Journey serves as a template under which all story structures fall, each bears some variation of it.

For fiction or nonfiction, your story structure determines how effectively you employ drama, intrigue, and tension to grab readers from the start and keep them to the end.

For more on story structure, visit my blog post 7 Story Structures Any Writer Can Use.

The post The Hero’s Journey: A Classic Story Structure appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

July 7, 2020

Character Motivation: How to Craft Realistic Characters

List a handful of your favorite novels and I’ll bet they have one thing in common: an unforgettable main character.

From Captain Ahab to Atticus Finch and from Harry Potter to Katniss Everdeen, such memorable characters seem like long-lost friends.

Inventing characters and infusing them with the internal strength to become heroic is an art you can spend a lifetime trying to master.

Not only must your characters grow throughout a story and evidence a true arc, but they must also feel real and knowable—to make them believable.

How can you breathe such life into your main character?

It’s no secret.

You must build them with realistic, credible motivations.

Do this well, and who knows? You might create your own Dorothy Gale or George Bailey.

What is Character Motivation?

Our main characters have to behave like real people in real situations, not like pawns to make a story work.

Even if your star is a superhero or lives in a land far, far away, give him* needs, wants, and dreams. (*I use male pronouns inclusively to represent both genders.)

Allow him flaws, mistakes, regrets.

These will account for his why—his motivation. In the end, we need characters with character.

What he does with that motivation will make him a hero or a failure—or a villain.

When he finally faces his crucible, where will he find his resolve?

The better you create and render your main character’s motivations, the more believable, memorable, and compelling your story will become.

That’s how we create an emotional connection between your reader and your character.

As I’ve said many times, readers like to be educated and entertained, but they never forget being emotionally moved.

That’s the way to keep them turning those pages until the end.

Types of Character Motivation

The late humanist psychologist Abraham Maslow believed that certain intrinsic needs must be met for anyone to be satisfied and motivated to meet their other needs.

He listed these as universal human needs:

Physical: food, water, sleep, shelter, and clothing. If one’s energy is devoted entirely to survival, his focus on anything else is diminished.

Safety: once physical needs are met, security becomes important: personal, financial, emotional, and physical.

Social: the longing for love and acceptance can be satisfied by family, friends, and intimate relationships.

Self-esteem: once this need to be valued by those around us—personally or professionally—is fulfilled, the desire to accomplish something greater begins to grow.

Self-actualization: once our basic needs are met and we are comfortable psychologically, we desire to fulfill the purpose for which we were created.

A complete list of character motivations would result in endless combinations of the above.

As writers, however, we should concern ourselves with two primary types of motivation:

Internal Motivations

Fear

Curiosity

Greed

Power

Revenge

Honor

Love

External Motivations

Physical reactions to outside influence or material reward don’t always come naturally, but happen because of an unexpected or undesired outcome.

Money

Laws

Deadlines

Praise

Survival

Competition

Trauma could also motivate your character.

Threat of violence

Witnessing violence

Sexual abuse

Physical abuse

Emotional abuse

Neglect (physical or emotional)

Accident or illness

Natural disaster

Loss/grief

War

How to Craft Your Character’s Motives

So, creating your character’s why means more than just choosing from a list of motivations.

Weave character motivation into your story by:

1 — Not neglecting your villain.

One of the most common mistakes I see in novels is a villain who acts nasty, but we never learn why.

Apparently he does bad things because that’s his role—he’s the bad guy.

Give your villain a history that tells your reader how he justifies his own behavior.

Too many fictitious villains seem to simply delight in being bad. In the real world, villains don’t see themselves as villains at all.

They have reasons to believe they’re right.

A realistic antagonist should have enough motivation in his backstory that the reader is almost tempted to sympathize with him.

2 — Using backstory.

Backstory is everything that’s happened prior to Chapter 1.

What shaped your hero/villain into the person he is today?

Things you should know, whether or not you include them:

When, where, and to whom he was born

Siblings

Where he attended school

Political affiliation

Occupation

Income

Goals

Skills

Spiritual life

Friends

Best friend

Whether he’s single, dating, or married

Worldview

Personality type

Anger triggers

Joys, pleasures

Fears

And anything else relevant to your story

3 — Employing plot twists.

Few people change for the better throughout life. They become bitter, angry as reality sets in, and they abandon their dreams.

That’s one of the reasons they escape to fiction, to live vicariously through someone for whom things did turn out better.

Allow your hero to grow and change, giving your reader that escape.

Your character arc must ring true, however, so your reader can’t say, “That would never happen.”

Readers want your story to make sense.

Plant clues that reveal strengths and weaknesses, so a surprising turn will seem inevitable in retrospect, but not predictable.

4 — Complicating things.

Speaking of predictable, don’t limit your character to one motivation.

Mix things up. Combine internal and external motivations.

A hero can struggle with not wanting to repeat the sins of his father (internal fear) while inadvertently repeating those very mistakes.

That’s real life.

And when the conflicts are resolved, the payoff is sweet.

5 — Determining your character’s goals.

But don’t confuse goals with motivation.

Motivation is your character’s why.

Goals give him direction.

Your hero may want to save the world from terrorists (goal), because a loved one was killed in the attack on the World Trade Center (motivation).

So give your hero external goals and the real (internal) reasons to achieve them.

6 — Showing, not telling.

This Cardinal rule of fiction also applies to character motivation.

Trust readers to deduce your character’s why by what they see in your scenes and hear in your dialogue.

If you have to tell about your character in narrative summary, you’ve failed.

The theater of the reader’s mind is more powerfully imaginative than anything Hollywood can put on the screen. Triggering it makes reading a joy.

Show who your character is through what he says, his body language, his thoughts, and actions.

Don’t just tell me he’s brave. Show him being brave.

For more on this, see my blog: Showing vs. Telling: What You Need to Know.

Character Motivation Examples

David Morrell says his students who fought in Vietnam inspired him to create the character John Rambo and the 5-movie Rambo franchise.

Rambo, a decorated war hero, returns home deeply disturbed, haunted by war, and suffering from PTSD.

That’s more than enough motivation to cause him to take actions he would otherwise not take to protect the people he loves.

Few stories offer a greater variety of character motivation than Winnie the Pooh by A.A. Milne.

Each character is relatable and endears himself to readers as shenanigans unfold.

Pooh, the main character, is lovable, quiet, friendly, thoughtful, and wise.

Christopher Robin, the only human, is one of Pooh’s best friends. He’s compassionate and wise beyond his years.

Piglet, Pooh’s other best friend, is small, shy, and fearful. But he exhibits great courage when faced with adversity.

Eeyore is the epitome of gloomy. He’s Pooh’s slow-moving, sarcastic donkey friend who always sees the negative.

Kanga, the only girl, is the protective mom of Roo, but really mothers the entire bunch. Always kind-hearted, she’s quick to offer gentle advice and feed her friends.

Roo, Kanga’s son, is a ray of sunshine in the Hundred Acre Wood, ever cheerful and full of energy.

Tigger epitomizes energy. He’s clumsy and can’t talk well but makes up for that with abundant confidence.

Rabbit is the smart one (or so he thinks) and is obsessively compulsive, angry, bossy, and impatient, but cares deeply about his friends.

Owl is the elder and enjoys hearing himself talk. He is wise and kind but often gets irritated when the others tire of his long-windedness.

Maintain Your Character’s Believability

A character doesn’t feel authentic if he’s missing that feeling of true humanity.

He must feel real or readers will lose interest.

They want to see weakness, both internal and external struggles, and how your character overcomes these.

Without a why, true motivation, he won’t likely overcome anything.

So give him a compelling motivation and you could create a story your readers will remember forever.

Character Arc Worksheet

If you’re an Outliner, this tool can help you get to know your hero before you start writing.

If you’re a Pantser (like me), you might rather dive right into the writing.

Still, you may find this helpful to fill in missing pieces as you write.

Do what works best for you and your story.

Click here to download my character arc worksheet!

The post Character Motivation: How to Craft Realistic Characters appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

June 10, 2020

How Many Words in a Novel? Your Guide to Fiction and Nonfiction Book Word Counts

As a reader, I’ve never felt a good book was too long, even more than a thousand pages. And I’ve never found a bad book short enough.

One of the most common questions writers ask me: “How long should my manuscript be?”

Well, different publishers look for different lengths for different genres. Helpful, eh?