Jerry B. Jenkins's Blog, page 12

February 4, 2020

Inspirational Writing Quotes From Famous Authors

Ever been told your writing belongs in the toilet?

I have.

As a 19-year-old sportswriter for a daily newspaper, I wanted more than anything to place an article in the Features section. I submitted one, complete with photos, to the editor.

He responded quickly in red at the top of the first page: “Great pictures. Bad story.”

Crushed, I mustered the courage to approach his desk.

“Sir, could you tell me what’s wrong with this so I can fix it?”

“Sure, Jenkins,” he said. “It’s sh–.”

If you’ve ever taken a hit like that, you know what comes to mind:

I’m not cut out for this.It’s too hard.I should quit.

I staggered back to my desk where my boss—the sports editor—offered powerful advice.

“Did you have any misgivings about it?”

I suggested several things I could’ve done differently.

“There you go. Anything you should have done is what you ought to do.”

The next day, I submitted the rewritten piece, and the editor immediately accepted it.

I’m sure glad I didn’t quit. That’s never the answer.

My mistake? Turning in writing I should have known was less than my best—which I vowed never to do again.

We writers all face roadblocks, but sound advice can help us smash through them.

I’ve compiled inspirational writing quotes from some of the world’s most successful authors—the kind we all need at times.

Quotes On Writing

If you want to change the world, pick up your pen and write. — Martin Luther

It takes a heap of sense to write good nonsense. — Mark Twain

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, therefore, is not an act but a habit. — Aristotle

By God’s design, I believe our hearts and minds are shaped by story. It’s how we learn. It’s how we make sense of the world. ― Liz Curtis Higgs

We are all apprentices in a craft where no one ever becomes a master. — Ernest Hemingway

I do not write with ease, nor am I ever pleased with anything I write. And so I rewrite. — Margaret Mitchell

There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at the typewriter and bleed. — Ernest Hemingway

We do not need magic to change the world; we carry all the power we need inside ourselves already. We have the power to imagine better. ― J.K. Rowling

You can make anything by writing. ― C.S. Lewis

Play around. Dive into absurdity and write. Take chances. You will succeed if you are fearless of failure. ― Natalie Goldberg

Exercise the writing muscle every day, even if it is only a letter, notes, a title list, a character sketch, a journal entry. Writers are like dancers, like athletes. Without that exercise, the muscles seize up. ― Jane Yolen

You don’t write because you want to say something; you write because you have something to say. ― F. Scott Fitzgerald

I’m a little pencil in the hand of a writing God, who is sending a love letter to the world. ― Mother Teresa

Words are a lens to focus one’s mind. — Ayn Rand

Get it down. Take chances. It may be bad, but it’s the only way you can do anything really good. — William Faulkner

The difference between fiction and reality? Fiction has to make sense. — Tom Clancy

I can shake off everything as I write; my sorrows disappear, my courage is reborn. ― Anne Frank

If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write. Simple as that. ― Stephen King

Start writing, no matter what. The water does not flow until the faucet is turned on. — Louis L’Amour

A professional writer is an amateur who didn’t quit. — Richard Bach

If you have other things in your life—family, friends, good productive day work—these can interact with your writing and the sum will be all the richer. — David Brin

I am not at all in a humor for writing; I must write on until I am. — Jane Austen

When I sit down to write, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art.’ I write because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing. — George Orwell

Fill your paper with the breathings of your heart. — William Wordsworth

Write what disturbs you, what you fear, what you have not been willing to speak about. — Natalie Goldberg

The most valuable of all talents is that of never using two words when one will do. — Thomas Jefferson

No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader. — Robert Frost

People on the outside think there’s something magical about writing, that you go up in the attic at midnight and cast the bones and come down in the morning with a story. But it isn’t like that. You work, and that’s all there is to it. — Harlan Ellison

All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know. — Ernest Hemingway

I would advise any beginning writer to write the first drafts as if no one else will ever read them — without a thought about publication — and only in the last draft to consider how the work will look from the outside. — Anne Tyler

Write what should not be forgotten. — Isabel Allende

Writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way. — E. L. Doctorow

I write to discover what I know. — Flannery O’Conner

A writer has the duty to be good, not lousy; true, not false; lively, not dull; accurate, not full of error; He should tend to lift people up, not lower them down. Writers do not merely reflect and interpret life, they inform and shape life. — E.B. White

Writing is the painting of the voice. — Voltaire

If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it. — Elmore Leonard

Read, read, read. Read everything — trash, classics, good and bad, and see how they do it. Just like a carpenter who works as an apprentice and studies the master. Read! You’ll absorb it. Then write. If it’s good, you’ll find out. If it’s not, throw it out of the window. — William Faulkner

Talent is cheaper than table salt. What separates the talented from the successful is a lot of hard work. — Steven King

Everybody walks past a thousand story ideas every day. The good writers are the ones who see five or six of them. Most people don’t see any. — Orson Scott

We read five words on the first page of a really good novel and we begin to forget we are reading printed words on a page; we begin to see images. — John Champion Gardner

A true piece of writing is a dangerous thing; it can change your life. — Tobias Wolff

Ready to start writing? Here are a few of my best guides:

How to Write a Book From Start to Finish

How to Write a Short Story That Captivates Your Reader

How to Write a Novel: A 12-Step Guide

How to Overcome Writer’s Block Once and For All: My Surprising Solution

The post Inspirational Writing Quotes From Famous Authors appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

January 8, 2020

How to Create a Powerful Character Arc

Page-turning novels have plausible, believable, memorable characters.

Consider these classics:

Gone With The Wind by Margaret MitchellThe Old Man and the Sea by Ernest HemingwayThe Sherlock Holmes novels by Arthur C. DoyleTo Kill a Mockingbird by Harper LeeAnne of Green Gables by L.M. MontgomeryThe Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum

All have unforgettable lead characters.

Those characters’ growth, their character arcs, makes all the difference.

So, What is Character Arc?

It’s simply the difference between who your character is at the beginning and who he is by the end [I use he inclusively to mean he or she] .

That doesn’t mean he has to go from flawed to fabulous. It just means he faces obstacles—both internal and external—that fundamentally change him..

In the most memorable classics—especially those with happy endings—the character develops skills and strengths that transform him.

The more challenges he faces, the better for your story and for his arc. Bestselling novelist Dean Koontz recommends “plunging your character into terrible trouble as soon as possible.”

Resist the temptation to make his life easy. Only the toughest challenges transform characters.

Click here to download my character arc worksheet.

Types of Character Arcs

1. Positive

The most common and popular arc sees your main character face myriad obstacles and challenges, which—in the end—he overcomes and becomes heroic. Naturally, the bigger the change from beginning to end, the more dramatic the arc.

Example: Perhaps the best known such arc is that of Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. So specific was the author’s portrayal that the very name Scrooge has become synonymous with a selfish, miserly, miserable curmudgeon.

Yet what reader can fail to thrill at the character arc that sees him become an entirely new man, joyful, generous, and loving?

2. Negative

Done well, this arc can be every bit as compelling, though it doesn’t result in a feel-good ending.

The character makes bad decisions and dangerous choices and ends far worse off than when the story began.

Example: In the popular binge worthy TV series Breaking Bad, Walter White begins as a nerdy, naïve, kind, and thoughtful high school science teacher who learns he has cancer.

Out of desperation, because his insurance won’t cover enough of his treatment to keep from bankrupting him, he uses his skills to develop and sell quality methamphetamine, which allows him to afford the treatments and dig his family out of a financial hole.

Even after he finds his cancer is in remission, he embraces the illegal drug culture and in the end destroys his own life, his family, and many other lives.

3. Flat

Too many writers reserve this wholly unacceptable approach for orbital characters or for main characters who may influence the world but remain personally unchanged.

Of course you will often have big part characters that aren’t even named and whose arcs would be irrelevant to the story and to the reader. But it’s otherwise unwise to assume significant secondary characters can have flat arcs. The more readers recognize changes in characters, the more compelling your story.

Examples: Often superheroes appear to have flat character arcs. But this is also a mistake. It proves much more interesting when even a lead character with superpowers faces a personal crisis and initially makes bad choices.

Maybe he responds out of pique or jealousy and must change his ways before succeeding.

How to Create a Powerful Character Arc

To maintain the all-important page-turning energy of your novel, your characters must be credible and believable.

Your lead must grow inwardly throughout.

Begin by asking yourself these questions:

#1 — What does your lead character want or need, and why?

Be sure it’s crucial enough and the stakes high enough to warrant an entire novel.

#2 — What or who is keeping him from what he wants or needs?

To keep your reader engaged and turning pages, you must challenge your character at every turn, removing every support and convenience. Thrust him into the most difficult predicaments you can imagine.

It’s tempting to equip our characters with whatever they need, because that’s the way we’d like our lives to be. But as authors, we should do the opposite. Take away the hero’s house, car, income, maybe even his spouse or lover.

Force your character to act in spite of it all. That will make his character arc the most dramatic.

#3 — What personal flaws and weaknesses emerge during his ordeal, and how do they keep him from his goals?

Readers relate to flawed characters. And every obstacle and challenge your character faces builds new muscles in him (inwardly and outwardly) that equip him to change in the end.

#4 — What inner struggles keep him from achieving his ultimate goal?

How does your character react when the going gets tough?

The best character arc reveals inner transformation, not just a change in circumstances.

#5 — What will he do to accomplish his goals?

Whatever you do, resist the temptation to explain to readers how your character is changing. Make sure they can deduce it from the story by what you show them. Do it right and you should experience an Author Arc as well. That’s a double win: you change and grow too.

That’s a double win: you change and grow too.

#6 — What heroic qualities emerge during the finale?

Your character must do more than realize the errors of his previous thoughts and actions. He must be proactive and flex those new muscles and insights to become the hero he really is.

His change must make sense and result from taking action, doing something.

Get this right and readers will remember your story forever.

Great Character Arcs…

…result from conflict:

Man vs. manMan vs. natureMan vs. GodMan vs. self

Give your hero flaws that aren’t repulsive or irredeemable. And imbue him with a foundation of kindness. A hero who shows respect to those who might be considered beneath him—say a doorman or wait staff—endear him to your reader.

Credible, believable characters with dramatic arcs make for the best, most memorable fiction you can imagine.

Character Arc Worksheet

This character arc worksheet can help Outliners get to know their hero.

But Pantsers (like me) will not likely have the patience for it and might rather dive right into the writing. So, don’t feel obligated to use it. Some Pantsers find it helpful to fill in missing pieces as they write.

Click here to download my character arc worksheet.

The post How to Create a Powerful Character Arc appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

January 6, 2020

How to Write a Book From Start to Finish: A Proven Guide

So you want to write a book. Becoming an author can change your life—not to mention give you the ability to impact thousands, even millions, of people.

But writing a book isn’t easy. As a 21-time New York Times bestselling author, I can tell you: It’s far easier to quit than to finish.

You’re going to be tempted to give up writing your book when you run out of ideas, when your own message bores you, when you get distracted, or when you become overwhelmed by the sheer scope of the task.

But what if you knew exactly:

Where to start…What each step entails…How to overcome fear, procrastination, and writer’s block …And how to keep from feeling overwhelmed?

You can write a book—and more quickly than you might think, because these days you have access to more writing tools than ever.

The key is to follow a proven, straightforward, step-by-step plan.

My goal here is to offer you that book-writing plan.

I’ve used the techniques I outline below to write more than 195 books (including the Left Behind series) over the past 45 years. Yes, I realize writing over four books per year on average is more than you may have thought humanly possible.

But trust me—with a reliable blueprint, you can get unstuck and finally write your book.

This is my personal approach to how to write a book. I’m confident you’ll find something here that can change the game for you. So, let’s jump in.

Want to download this 20-step guide so you can read it whenever you wish? Click here.

How to Write a Book From Start to Finish

Part 1: Before You Begin Writing Your Book

Establish your writing space. Assemble your writing tools.

Part 2: How to Start Writing a Book

Break the project into small pieces. Settle on your BIG idea. Construct your outline. Set a firm writing schedule. Establish a sacred deadline. Embrace procrastination (really!). Eliminate distractions. Conduct your research. Start calling yourself a writer.

Part 3: The Book-Writing Itself

Think reader-first. Find your writing voice. Write a compelling opener. Fill your story with conflict and tension. Turn off your internal editor while writing the first draft. Persevere through The Marathon of the Middle. Write a resounding ending.

Part 4: Editing Your Book

Become a ferocious self-editor. Find a mentor.

Part 5: Publishing Your Book

Decide on your publishing avenue. Properly format your manuscript. Set up and grow your author platform.

Part One: Before You Begin Writing Your Book

You’ll never regret—in fact, you’ll thank yourself later—for investing the time necessary to prepare for such a monumental task.

You wouldn’t set out to cut down a huge grove of trees with just an axe. You’d need a chain saw, perhaps more than one. Something to keep them sharp. Enough fuel to keep them running.

You get the picture. Don’t shortcut this foundational part of the process.

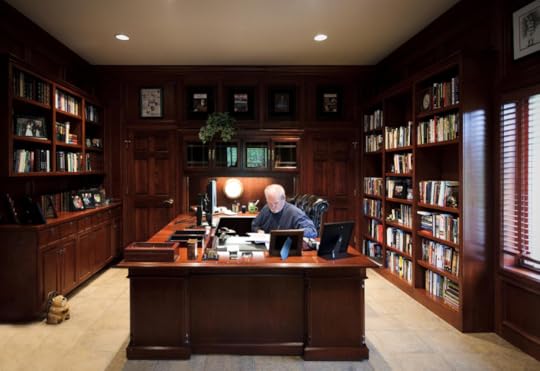

Step 1. Establish your writing space.

To write your book, you don’t need a sanctuary. In fact, I started my career on my couch facing a typewriter perched on a plank of wood suspended by two kitchen chairs.

What were you saying about your setup again? We do what we have to do.

And those early days on that sagging couch were among the most productive of my career.

Naturally, the nicer and more comfortable and private you can make your writing lair (I call mine my cave), the better.

Real writers can write anywhere.

Some authors write their books in restaurants and coffee shops. My first full time job was at a newspaper where 40 of us clacked away on manual typewriters in one big room—no cubicles, no partitions, conversations hollered over the din, most of my colleagues smoking, teletype machines clattering.

Cut your writing teeth in an environment like that, and anywhere else seems glorious.

Step 2. Assemble your writing tools.

In the newspaper business, there was no time to hand write our stuff and then type it for the layout guys. So I have always written at a keyboard and still write my books that way.

Most authors do, though some hand write their first drafts and then keyboard them onto a computer or pay someone to do that.

No publisher I know would even consider a typewritten manuscript, let alone one submitted in handwriting.

The publishing industry runs on Microsoft Word, so you’ll need to submit Word document files. Whether you prefer a Mac or a PC, both will produce the kinds of files you need.

And if you’re looking for a musclebound electronic organizing system, you can’t do better than Scrivener. It works well on both PCs and Macs, and it nicely interacts with Word files.

Just remember, Scrivener has a steep learning curve, so familiarize yourself with it before you start writing.

Scrivener users know that taking the time to learn the basics is well worth it.

Tons of other book writing tools exist to help you. I’ve included some of the most well known in my blog post on book writing software and my writing tools page for your reference.

So, what else do you need?

If you are one who handwrites your first drafts, don’t scrimp on paper, pencils, or erasers.

Don’t shortchange yourself on a computer either. Even if someone else is keyboarding for you, you’ll need a computer for research and for communicating with potential agents, editors, publishers.

Get the best computer you can afford, the latest, the one with the most capacity and speed.

Try to imagine everything you’re going to need in addition to your desk or table, so you can equip yourself in advance and don’t have to keep interrupting your work to find things like:

StaplersPaper clipsRulersPencil holdersPencil sharpenersNote padsPrinting paperPaperweightTape dispensersCork or bulletin boardsClocksBookendsReference worksSpace heatersFansLampsBeverage mugsNapkinsTissuesYou name itLast, but most crucial, get the best, most ergonomic chair you can afford.

If I were to start my career again with that typewriter on a plank, I would not sit on that couch. I’d grab another straight-backed kitchen chair or something similar and be proactive about my posture and maintaining a healthy spine.

There’s nothing worse than trying to be creative and immerse yourself in writing while you’re in agony. The chair I work in today cost more than my first car!

If you’ve never used some of the items I listed above and can’t imagine needing them, fine. But make a list of everything you know you’ll need so when the actual writing begins, you’re already equipped.

As you grow as a writer and actually start making money at it, you can keep upgrading your writing space.

Where I work now is light years from where I started. But the point is, I didn’t wait to start writing until I could have a great spot in which to do it.

Part Two: How to Start Writing a Book

Step 1. Break your book into small pieces.

Writing a book feels like a colossal project, because it is! But your manuscript will be made up of many small parts.

An old adage says that the way to eat an elephant is one bite at a time.

Try to get your mind off your book as a 400-or-so-page monstrosity.

It can’t be written all at once any more than that proverbial elephant could be eaten in a single sitting.

See your book for what it is: a manuscript made up of sentences, paragraphs, pages. Those pages will begin to add up, and though after a week you may have barely accumulated double digits, a few months down the road you’ll be into your second hundred pages.

So keep it simple.

Start by distilling your big book idea from a page or so to a single sentence—your premise. The more specific that one-sentence premise, the more it will keep you focused while you’re writing.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Before you can turn your big idea into one sentence, which can then be expanded to an outline, you have to settle on exactly what that big idea is.

Step 2. Settle on your BIG idea.

To be book-worthy, your idea has to be killer.

You need to write something about which you’re passionate, something that gets you up in the morning, draws you to the keyboard, and keeps you there. It should excite not only you, but also anyone you tell about it.

I can’t overstate the importance of this.

If you’ve tried and failed to finish your book before—maybe more than once—it could be that the basic premise was flawed. Maybe it was worth a blog post or an article but couldn’t carry an entire book.

Think The Hunger Games, Harry Potter, or How to Win Friends and Influence People. The market is crowded, the competition fierce. There’s no more room for run-of-the-mill ideas. Your premise alone should make readers salivate.

Go for the big concept book.

How do you know you’ve got a winner? Does it have legs? In other words, does it stay in your mind, growing and developing every time you think of it?

Run it past loved ones and others you trust.

Does it raise eyebrows? Elicit Wows? Or does it result in awkward silences?

The right concept simply works, and you’ll know it when you land on it. Most importantly, your idea must capture you in such a way that you’re compelled to write it. Otherwise you’ll lose interest halfway through and never finish.

Want to download this 20-step guide so you can read it whenever you wish? Click here.

Step 3. Construct your outline.

Writing your book without a clear vision of where you’re going usually ends in disaster.

Even if you’re writing a fiction book and consider yourself a Pantser* as opposed to an Outliner, you need at least a basic structure.

[*Those of us who write by the seat of our pants and, as Stephen King advises, put interesting characters in difficult situations and write to find out what happens]

You don’t have to call it an outline if that offends your sensibilities. But fashion some sort of a directional document that provides structure for your book and also serves as a safety net.

If you get out on that Pantser highwire and lose your balance, you’ll thank me for advising you to have this in place.

Now if you’re writing a nonfiction book, there’s no substitute for an outline.

Potential agents or publishers require this in your proposal. They want to know where you’re going, and they want to know that you know. What do you want your reader to learn from your book, and how will you ensure they learn it?

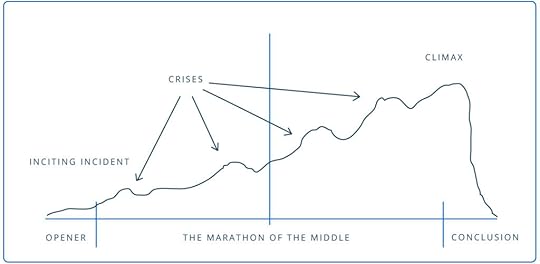

Fiction or nonfiction, if you commonly lose interest in your book somewhere in what I call the Marathon of the Middle, you likely didn’t start with enough exciting ideas.

That’s why and outline (or a basic framework) is essential. Don’t even start writing until you’re confident your structure will hold up through the end.

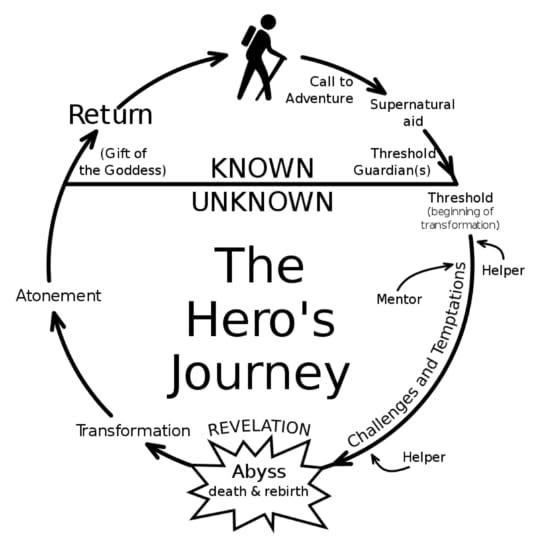

You may recognize this novel structure illustration.

Did you know it holds up—with only slight adaptations—for nonfiction books too? It’s self-explanatory for novelists; they list their plot twists and developments and arrange them in an order that best serves to increase tension.

What separates great nonfiction from mediocre? The same structure!

Arrange your points and evidence in the same way so you’re setting your reader up for a huge payoff, and then make sure you deliver.

If your nonfiction book is a memoir, an autobiography, or a biography, structure it like a novel and you can’t go wrong.

But even if it’s a straightforward how-to book, stay as close to this structure as possible, and you’ll see your manuscript come alive.

Make promises early, triggering your reader to anticipate fresh ideas, secrets, inside information, something major that will make him thrilled with the finished product.

While a nonfiction book may not have as much action or dialogue or character development as a novel, you can inject tension by showing where people have failed before and how your reader can succeed.

You can even make the how-to project look impossible until you pay off that setup with your unique solution.

Keep your outline to a single page for now. But make sure every major point is represented, so you’ll always know where you’re going.

And don’t worry if you’ve forgotten the basics of classic outlining or have never felt comfortable with the concept.

Your outline must serve you. If that means Roman numerals and capital and lowercase letters and then Arabic numerals, you can certainly fashion it that way. But if you just want a list of sentences that synopsize your idea, that’s fine too.

Simply start with your working title, then your premise, then—for fiction, list all the major scenes that fit into the rough structure above.

For nonfiction, try to come up with chapter titles and a sentence or two of what each chapter will cover.

Once you have your one-page outline, remember it is a fluid document meant to serve you and your book. Expand it, change it, play with it as you see fit—even during the writing process.

Step 4. Set a firm writing schedule.

Ideally, you want to schedule at least six hours per week to write your book.

That may consist of three sessions of two hours each, two sessions of three hours, or six one-hour sessions—whatever works for you.

I recommend a regular pattern (same times, same days) that can most easily become a habit. But if that’s impossible, just make sure you carve out at least six hours so you can see real progress.

Having trouble finding the time to write a book? News flash—you won’t find the time. You have to make it.

I used the phrase carve out above for a reason. That’s what it takes.

Something in your calendar will likely have to be sacrificed in the interest of writing time.

Make sure it’s not your family—they should always be your top priority. Never sacrifice your family on the altar of your writing career.

But beyond that, the truth is that we all find time for what we really want to do.

Many writers insist they have no time to write, but they always seem to catch the latest Netflix original series, or go to the next big Hollywood feature. They enjoy concerts, parties, ball games, whatever.

How important is it to you to finally write your book? What will you cut from your calendar each week to ensure you give it the time it deserves?

A favorite TV show?An hour of sleep per night? (Be careful with this one; rest is crucial to a writer.)A movie?A concert?A party?

Successful writers make time to write.

When writing becomes a habit, you’ll be on your way.

Step 5. Establish a sacred deadline.

Without deadlines, I rarely get anything done. I need that motivation.

Admittedly, my deadlines are now established in my contracts from publishers.

If you’re writing your first book, you probably don’t have a contract yet. To ensure you finish your book, set your own deadline—then consider it sacred.

Tell your spouse or loved one or trusted friend. Ask that they hold you accountable.

Now determine—and enter in your calendar—the number of pages you need to produce per writing session to meet your deadline. If it proves unrealistic, change the deadline now.

If you have no idea how many pages or words you typically produce per session, you may have to experiment before you finalize those figures.

Say you want to finish a 400-page manuscript by this time next year.

Divide 400 by 50 weeks (accounting for two off-weeks), and you get eight pages per week.

Divide that by your typical number of writing sessions per week and you’ll know how many pages you should finish per session.

Now is the time to adjust these numbers, while setting your deadline and determining your pages per session.

Maybe you’d rather schedule four off weeks over the next year. Or you know your book will be unusually long.

Change the numbers to make it realistic and doable, and then lock it in. Remember, your deadline is sacred.

Step 6. Embrace procrastination (really!).

You read that right. Don’t fight it; embrace it.

You wouldn’t guess it from my 195+ published books, but I’m the king of procrastinators.

Surprised?

Don’t be. So many authors are procrastinators that I’ve come to wonder if it’s a prerequisite.

The secret is to accept it and, in fact, schedule it.

I quit fretting and losing sleep over procrastinating when I realized it was inevitable and predictable, and also that it was productive.

Sound like rationalization?

Maybe it was at first. But I learned that while I’m putting off the writing, my subconscious is working on my book. It’s a part of the process. When you do start writing again, you’ll enjoy the surprises your subconscious reveals to you.

So, knowing procrastination is coming, book it on your calendar.

Take it into account when you’re determining your page quotas. If you have to go back in and increase the number of pages you need to produce per session, do that (I still do it all the time).

But—and here’s the key—you must never let things get to where that number of pages per day exceeds your capacity.

It’s one thing to ratchet up your output from two pages per session to three. But if you let it get out of hand, you’ve violated the sacredness of your deadline.

How can I procrastinate and still meet more than 190 deadlines?

Because I keep the deadlines sacred.

Step 7. Eliminate distractions to stay focused.

Are you as easily distracted as I am?

Have you found yourself writing a sentence and then checking your email? Writing another and checking Facebook? Getting caught up in the pictures of 10 Sea Monsters You Wouldn’t Believe Actually Exist?

Then you just have to check out that precious video from a talk show where the dad surprises the family by returning from the war.

That leads to more and more of the same. Once I’m in, my writing is forgotten, and all of a sudden the day has gotten away from me.

The answer to these insidious timewasters?

Look into these apps that allow you to block your email, social media, browsers, game apps, whatever you wish during the hours you want to write. Some carry a modest fee, others are free.

Freedom app FocusWriter StayFocusd WriteRoom

Step 8. Conduct your research.

Yes, research is a vital part of the process, whether you’re writing fiction or nonfiction.

Fiction means more than just making up a story.

Your details and logic and technical and historical details must be right for your novel to be believable.

And for nonfiction, even if you’re writing about a subject in which you’re an expert—as I’m doing here—getting all the facts right will polish your finished product.

In fact, you’d be surprised at how many times I’ve researched a fact or two while writing this blog post alone.

The last thing you want is even a small mistake due to your lack of proper research.

Regardless the detail, trust me, you’ll hear from readers about it.

Your credibility as an author and an expert hinges on creating trust with your reader. That dissolves in a hurry if you commit an error.

My favorite research resources:

World Almanacs : These alone list almost everything you need for accurate prose: facts, data, government information, and more. For my novels, I often use these to come up with ethnically accurate character names. The Merriam-Webster Thesaurus : The online version is great, because it’s lightning fast. You couldn’t turn the pages of a hard copy as quickly as you can get where you want to onscreen. One caution: Never let it be obvious you’ve consulted a thesaurus. You’re not looking for the exotic word that jumps off the page. You’re looking for that common word that’s on the tip of your tongue. WorldAtlas.com : Here you’ll find nearly limitless information about any continent, country, region, city, town, or village. Names, monetary units, weather patterns, tourism info, and even facts you wouldn’t have thought to search for. I get ideas when I’m digging here, for both my novels and my nonfiction books.

Step 9. Start calling yourself a writer.

Your inner voice may tell you, “You’re no writer and you never will be. Who do you think you are, trying to write a book?”

That may be why you’ve stalled at writing your book in the past.

But if you’re working at writing, studying writing, practicing writing, that makes you a writer. Don’t wait till you reach some artificial level of accomplishment before calling yourself a writer.

A cop in uniform and on duty is a cop whether he’s actively enforced the law yet or not. A carpenter is a carpenter whether he’s ever built a house.

Self-identify as a writer now and you’ll silence that inner critic—who, of course, is really you.

Talk back to yourself if you must. It may sound silly, but acknowledging yourself as a writer can give you the confidence to keep going and finish your book.

Are you a writer? Say so.

Want to download this 20-step guide so you can read it whenever you wish? Click here.

Part Three: The Book-Writing Itself

Step 1. Think reader-first.

This is so important that that you should write it on a sticky note and affix it to your monitor so you’re reminded of it every time you write.

Every decision you make about your manuscript must be run through this filter.

Not you-first, not book-first, not editor-, agent-, or publisher-first. Certainly not your inner circle- or critics-first.

Reader-first, last, and always.

If every decision is based on the idea of reader-first, all those others benefit anyway.

When fans tell me they were moved by one of my books, I think back to this adage and am grateful I maintained that posture during the writing.

Does a scene bore you? If you’re thinking reader-first, it gets overhauled or deleted.

Where to go, what to say, what to write next? Decide based on the reader as your priority.

Whatever your gut tells you your reader would prefer, that’s your answer.

Whatever will intrigue him, move him, keep him reading, those are your marching orders.

So, naturally, you need to know your reader. Rough age? General interests? Loves? Hates? Attention span?

When in doubt, look in the mirror.

The surest way to please your reader is to please yourself. Write what you would want to read and trust there is a broad readership out there that agrees.

Step 2. Find your writing voice.

Discovering your voice is nowhere near as complicated as some make it out to be.

You can find yours by answering these quick questions:

What’s the coolest thing that ever happened to you?Who’s the most important person you told about it?What did you sound like when you did?That’s your writing voice. It should read the way you sound at your most engaged.

That’s all there is to it.

If you write fiction and the narrator of your book isn’t you, go through the three-question exercise on the narrator’s behalf—and you’ll quickly master the voice.

Here’s a blog I posted that’ll walk you through the process.

Step 3. Write a compelling opener.

If you’re stuck because of the pressure of crafting the perfect opening line for your book, you’re not alone.

And neither is your angst misplaced.

This is not something you should put off and come back to once you’ve started on the rest of the first chapter.

Oh, it can still change if the story dictates that. But settling on a good one will really get you off and running.

It’s unlikely you’ll write a more important sentence than your first one, whether you’re writing fiction or nonfiction. Make sure you’re thrilled with it and then watch how your confidence—and momentum—soars.

Most great first lines fall into one of these categories:

1. Surprising

Fiction: “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” —George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four

Nonfiction: “By the time Eustace Conway was seven years old, he could throw a knife accurately enough to nail a chipmunk to a tree.” —Elizabeth Gilbert, The Last American Man

2. Dramatic Statement

Fiction: “They shoot the white girl first.” —Toni Morrison, Paradise

Nonfiction: “I was five years old the first time I ever set foot in prison.” —Jimmy Santiago Baca, A Place to Stand

3. Philosophical

Fiction: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” —Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

Nonfiction: “It’s not about you.” —Rick Warren, The Purpose Driven Life

4. Poetic

Fiction: “When I finally caught up with Abraham Trahearne, he was drinking beer with an alcoholic bulldog named Fireball Roberts in a ramshackle joint just outside of Sonoma, California, drinking the heart right out of a fine spring afternoon. —James Crumley, The Last Good Kiss

Nonfiction: “The village of Holcomb stands on the high wheat plains of western Kansas, a lonesome area that other Kansans call ‘out there.’” —Truman Capote, In Cold Blood

Great opening lines from other classics may give you ideas for yours. Here’s a list of famous openers.

Step 4. Fill your story with conflict and tension.

Your reader craves conflict, and yes, this applies to nonfiction readers as well.

In a novel, if everything is going well and everyone is agreeing, your reader will soon lose interest and find something else to do.

Are two of your characters talking at the dinner table? Have one say something that makes the other storm out.

Some deep-seeded rift in their relationship has surfaced—just a misunderstanding, or an injustice?

Thrust people into conflict with each other.

That’ll keep your reader’s attention.

Certain nonfiction genres won’t lend themselves to that kind of conflict, of course, but you can still inject tension by setting up your reader for a payoff in later chapters. Check out some of the current bestselling nonfiction works to see how writers accomplish this.

Somehow they keep you turning those pages, even in a simple how-to title.

Tension is the secret sauce that will propel your reader through to the end.

And sometimes that’s as simple as implying something to come.

Step 5. Turn off your internal editor while writing the first draft.

Many of us perfectionists find it hard to write a first draft—fiction or nonfiction—without feeling compelled to make every sentence exactly the way we want it.

That voice in your head that questions every word, every phrase, every sentence, and makes you worry you’re being redundant or have allowed cliches to creep in—well, that’s just your editor alter ego.

He or she needs to be told to shut up.

This is not easy.

Deep as I am into a long career, I still have to remind myself of this every writing day. I cannot be both creator and editor at the same time. That slows me to a crawl, and my first draft of even one brief chapter could take days.

Our job when writing that first draft is to get down the story or the message or the teaching—depending on your genre.

It helps me to view that rough draft as a slab of meat I will carve tomorrow.

I can’t both produce that hunk and trim it at the same time.

A cliche, a redundancy, a hackneyed phrase comes tumbling out of my keyboard, and I start wondering whether I’ve forgotten to engage the reader’s senses or aimed for his emotions.

That’s when I have to chastise myself and say, “No! Don’t worry about that now! First thing tomorrow you get to tear this thing up and put it back together again to your heart’s content!”

Imagine yourself wearing different hats for different tasks, if that helps—whatever works to keep you rolling on that rough draft. You don’t need to show it to your worst enemy or even your dearest love. This chore is about creating. Don’t let anything slow you down.

Some like to write their entire first draft before attacking the revision. As I say, whatever works.

Doing it that way would make me worry I’ve missed something major early that will cause a complete rewrite when I discover it months later. I alternate creating and revising.

The first thing I do every morning is a heavy edit and rewrite of whatever I wrote the day before. If that’s ten pages, so be it. I put my perfectionist hat on and grab my paring knife and trim that slab of meat until I’m happy with every word.

Then I switch hats, tell Perfectionist Me to take the rest of the day off, and I start producing rough pages again.

So, for me, when I’ve finished the entire first draft, it’s actually a second draft because I have already revised and polished it in chunks every day.

THEN I go back through the entire manuscript one more time, scouring it for anything I missed or omitted, being sure to engage the reader’s senses and heart, and making sure the whole thing holds together.

I do not submit anything I’m not entirely thrilled with.

I know there’s still an editing process it will go through at the publisher, but my goal is to make my manuscript the absolute best I can before they see it.

Compartmentalize your writing vs. your revising and you’ll find that frees you to create much more quickly.

Step 6. Persevere through The Marathon of the Middle.

Most who fail at writing a book tell me they give up somewhere in what I like to call The Marathon of the Middle.

That’s a particularly rough stretch for novelists who have a great concept, a stunning opener, and they can’t wait to get to the dramatic ending. But they bail when they realize they don’t have enough cool stuff to fill the middle.

They start padding, trying to add scenes just for the sake of bulk, but they’re soon bored and know readers will be too.

This actually happens to nonfiction writers too.

The solution there is in the outlining stage, being sure your middle points and chapters are every bit as valuable and magnetic as the first and last.

If you strategize the progression of your points or steps in a process—depending on nonfiction genre—you should be able to eliminate the strain in the middle chapters.

For novelists, know that every book becomes a challenge a few chapters in. The shine wears off, keeping the pace and tension gets harder, and it’s easy to run out of steam.

But that’s not the time to quit. Force yourself back to your structure, come up with a subplot if necessary, but do whatever you need to so your reader stays engaged.

Fiction writer or nonfiction author, The Marathon of the Middle is when you must remember why you started this journey in the first place.

It isn’t just that you want to be an author. You have something to say. You want to reach the masses with your message.

Yes, it’s hard. It still is for me—every time. But don’t panic or do anything rash, like surrendering. Embrace the challenge of the middle as part of the process. If it were easy, anyone could do it.

Step 7. Write a resounding ending.

This is just as important for your nonfiction book as your novel. It may not be as dramatic or emotional, but it could be—especially if you’re writing a memoir.

But even a how-to or self-help book needs to close with a resounding thud, the way a Broadway theater curtain meets the floor.

How do you ensure your ending doesn’t fizzle?

Don’t rush it. Give readers the payoff they’ve been promised. They’ve invested in you and your book the whole way. Take the time to make it satisfying.Never settle for close enough just because you’re eager to be finished. Wait till you’re thrilled with every word, and keep revising until you are.If it’s unpredictable, it had better be fair and logical so your reader doesn’t feel cheated. You want him to be delighted with the surprise, not tricked.If you have multiple ideas for how your book should end, go for the heart rather than the head, even in nonfiction. Readers most remember what moves them.

Want to download this 20-step guide so you can read it whenever you wish? Click here.

Part Four: Rewriting Your Book

Step 1. Become a ferocious self-editor.

Agents and editors can tell within the first two pages whether your manuscript is worthy of consideration. That sounds unfair, and maybe it is. But it’s also reality, so we writers need to face it.

How can they often decide that quickly on something you’ve devoted months, maybe years, to?

Because they can almost immediately envision how much editing would be required to make those first couple of pages publishable. If they decide the investment wouldn’t make economic sense for a 300-400-page manuscript, end of story.

Your best bet to keep an agent or editor reading your manuscript?

You must become a ferocious self-editor. That means:

Omit needless wordsChoose the simple word over one that requires a dictionaryAvoid subtle redundancies, like “He thought in his mind…” (Where else would someone think?)Avoid hedging verbs like almost frowned, sort of jumped, etc.Generally remove the word that—use it only when absolutely necessary for clarityGive the reader credit and resist the urge to explain, as in, “She walked through the open door.” (Did we need to be told it was open?)Avoid too much stage direction (what every character is doing with every limb and digit)Avoid excessive adjectives Show, don’t tell And many more

For my full list and how to use them, click here. (It’s free.)

When do you know you’re finished revising? When you’ve gone from making your writing better to merely making it different. That’s not always easy to determine, but it’s what makes you an author.

Step 2. Find a mentor.

Get help from someone who’s been where you want to be.

Imagine engaging a mentor who can help you sidestep all the amateur pitfalls and shave years of painful trial-and-error off your learning curve.

Just make sure it’s someone who really knows the writing and publishing world. Many masquerade as mentors and coaches but have never really succeeded themselves.

Look for someone widely-published who knows how to work with agents, editors, and publishers.

There are many helpful mentors online. I teach writers through this free site, as well as in my members-only Writers Guild.

Part 5: Publishing Your Book

Step 1. Decide on your publishing avenue.

In simple terms, you have two options when it comes to publishing your book:

1. Traditional publishing

Traditional publishers take all the risks. They pay for everything from editing, proofreading, typesetting, printing, binding, cover art and design, promotion, advertising, warehousing, shipping, billing, and paying author royalties.

2. Self-publishing

Everything is on you. You are the publisher, the financier, the decision-maker. Everything listed above falls to you. You decide who does it, you approve or reject it, and you pay for it. The term self-publishing is a bit of a misnomer, however, because what you’re paying for is not publishing, but printing.

Both avenues are great options under certain circumstances.

Not sure which direction you want to take? Click here to read my in-depth guide to publishing a book. It’ll show you the pros and cons of each, what each involves, and my ultimate recommendation.

Step 2: Properly format your manuscript.

Regardless whether you traditionally or self-publish your book, proper formatting is critical.

Why?

Because poor formatting makes you look like an amateur.

Readers and agents expect a certain format for book manuscripts, and if you don’t follow their guidelines, you set yourself up for failure.

Best practices when formatting your book:

Use 12-point typeUse a serif font; the most common is Times RomanDouble space your manuscriptNo extra space between paragraphsOnly one space between sentencesIndent each paragraph half an inch (setting a tab, not using several spaces)Text should be flush left and ragged right, not justifiedIf you choose to add a line between paragraphs to indicate a change of location or passage of time, center a typographical dingbat (like ***) on the lineBlack text on a white background onlyOne-inch margins on the top, bottom, and sides (the default in Word)Create a header with the title followed by your last name and the page number. The header should appear on each page other than the title page.

If you need help implementing these formatting guidelines, click here to read my in-depth post on formatting your manuscript.

Step 3. Set up your author website and grow your platform.

All serious authors need a website. Period.

Because here’s the reality of publishing today…

You need an audience to succeed.

If you want to traditionally publish, agents and publishers will Google your name to see if you have a website and a following.

If you want to self-publish, you need a fan base.

And your author website serves as a hub for your writing, where agents, publishers, readers, and fans can learn about your work.

Don’t have an author website yet? Click here to read my tutorial on setting this up.

You Have What It Takes to Write a Book

Writing a book is a herculean task, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be done.

You can do this.

Take it one step at a time and vow to stay focused. And who knows, maybe by this time next year you’ll be holding a published copy of your book. :)

I’ve created an exclusive writing guide called How to Maximize Your Writing Time that will help you stay on track and finish writing your book.

Get your FREE copy by clicking the button below.

Click here to download How to Maximize Your Writing Time.

The post How to Write a Book From Start to Finish: A Proven Guide appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

January 1, 2020

Your Ultimate Guide to Writing Contests Through 2021

Regardless where you are on your writing journey—from wannabe to bestseller—you can benefit from entering contests.

Why?

Because the right contest can tell you:

Where you standHow you measure up against the competitionWhat you still need to learn

Not to mention, you could win prizes. :)

That’s why my team and I conducted extensive research to not only find free, high-quality writing contests, but to also give you the best chance to win.

Last Updated: 1/1/20

Need help writing your novel? Click here to download Jerry’s ultimate 12-step guide.

Free Writing Contests Through 2021

53-Word Story Contest

Prize: Publication, a free book from Press 53

Deadline: Frequent contests

Sponsor: Prime Number Magazine

Description: Each month Prime Number Magazine invites writers to submit a 53-word story based on a prompt.

The Jeff Sharlet Memorial Award for Veterans

Prize:

1st: $1,000 and publication in The Iowa Review

2nd: $750

3rd (3 selected): $500

Deadline: 5/1/20 – 5/31/20

Sponsor: The Iowa Review

Description: Due to a donation from the family of veteran and antiwar author, Jeff Sharlet, The Iowa Review is able to hold The Jeff Sharlet Memorial Award for Veterans. Note: Only U.S. military veterans and active duty personnel may submit writing in any genre about any topic.

St. Francis College Literary Prize

Prize: $50,000

Deadline: TBD 2021

Sponsor: St. Francis College

Description: For mid-career authors who have just published their 3rd, 4th, or 5th fiction book. Self-published books and English translations are also considered.

New Writers Awards

Prize: The winning authors tour several colleges, giving readings, lecturing, visiting classes, conducting workshops, and publicizing their books. Each writer receives an honorarium of at least $500 from each college visited, as well as travel expenses, hotel accommodations, and hospitality.

Deadline: TBD 2020

Sponsor: Great Lakes Colleges Association

Description: Every year since 1970, the Association has honored newly published writers with an award for a first published volume of poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction. Note: Publishers (not the writers) are invited to submit works that “emphasize literary excellence.” All entries must be written in English and published in the United States or Canada.

Young Lions Fiction Award

Prize: $10,000

Deadline: 6/11/20

Sponsor: New York Public Library

Description: Each Spring, the Library gives a writer 35 years old or younger $10,000 for a novel or a collection of short stories. This award seeks to encourage young and emerging writers of contemporary fiction.

The Iowa Short Fiction Award

Prize: Publication in the University of Iowa Press

Deadline: 9/30/20

Sponsor: University of Iowa Press

Description: Seeking 150-page (or longer) collections of fiction by writers who have not previously traditionally published a novel or fiction collection.

Pen/Faulkner Award for Fiction

Prize: $15,000

Deadline: TBD 2020

Sponsor: Pen/Faulkner Foundation

Description: Mary Lee established the Award in 1980 to recognize excellent literary fiction. It accepts published books and is peer-juried. The winner is honored as “first among equals.”

Friends of American Writers Literary Award

Prize: $1,000 – $3,000

Deadline: TBD 2020

Sponsor: Friends of American Writers Chicago

Description: Current or former residents of the American Midwest (or authors whose book takes place in the Midwest) are invited to submit to the FAW Literary Award. Published novels or nonfiction books are welcome. Authors must have three or fewer books published, including the submission.

Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards

Prize: $10,000

Deadline: 12/31/20

Sponsor: Cleveland Foundation

Description: The Award seeks fiction, poetry, and nonfiction books published the previous year (books published in 2019 are eligible for the 2020 prize) “that contribute to our understanding of racism and our appreciation of cultural diversity.” Self-published work not accepted.

Cabell First Novelist Award

Prize: $5,000

Deadline: 12/31/20

Sponsor: Virginia Commonwealth University

Description: Seeks to honor first-time novelists “who have navigated their way through the maze of imagination and delivered a great read.” Novels published the previous year are accepted.

The Gabo Prize

Prize: $200

Deadline: Every February and August

Sponsor: Lunch Ticket

Description: Awards translators and authors of multilingual texts (poetry and prose) with $200 and publication in Lunch Ticket.

Transitions Abroad Expatriate and Work Abroad Writing Contest

Prize:

First: $500

Second: $150

Third: $100

All Finalists: $50

Deadline: 9/15/20

Sponsor: Transitions Abroad Publishing, Inc.

Description: Seeking inspiring articles or practical mini-guides that also provide in-depth descriptions of your experience moving, living, and working abroad (including teaching, internships, volunteering, short-term jobs, etc.). Work should be between 1,200-3,000 words. All writers welcome.

Short Fiction Prize

Prize: $1,000 and a scholarship to the 2021 Southampton Writers Conference.

Deadline: 6/1/20

Sponsor: Stony Brook University

Description: Seeking short stories by undergraduates at American or Canadian colleges.

The Wallace Stegner Prize in Environmental Humanities

Prize: $5,000 and publication.

Deadline: 12/30/21

Sponsor: The University of Utah Press

Description: Wallace Stegner was a student of the American West, an environmental spokesman, and a creative writing teacher. In his memory, the University of Utah Press seeks book-length monographs in the field of environmental humanities. Projects focusing on the American West preferred.

Drue Heinz Literature Prize

Prize: $15,000 and publication

Deadline: May 1 – June 30 yearly

Sponsor: University of Pittsburgh Press

Description: Seeks short fiction or novella collections. Writers who have published a novel or a book-length collection of fiction with a traditional book publisher, or a minimum of three short stories or novellas in magazines or journals of national distribution are accepted.

Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence

Prize: $15,000

Deadline: TBD

Sponsor: Baton Rouge Area Foundation

Description: Honors novels and story collections by African American writers. Entries that will be published in 2019 are accepted.

Brooklyn Nonfiction Prize

Prize: $500

Deadline: TBD

Sponsor: Brooklyn Film & Arts Festival

Description: Showcases essays set in Brooklyn. Five authors will be asked to read their pieces at the Brooklyn Film & Arts Festival.

International Flash Fiction Competition

Prize:

First: $20,000

Three runners-up: $2,000

Deadline: TBD

Sponsor: The César Egido Serrano Foundation

Description: With over 40,000 participants last year, this prize invites authors to submit flash fiction in Spanish, English, Arabic, and Hebrew.

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction

Prize: $1,000

Deadline: 12/1/20

Sponsor: The Langum Foundation

Description: To make American history accessible to general educated readers, the Foundation seeks American historical novels published in the previous year. Novels should take place in America before 1950 (split-time novels accepted). Novels set outside American but including American values and characters accepted (such as about the American military). Self-published novels not accepted.

W.Y. Boyd Literary Award

Prize: $5,000

Deadline: 12/1/20

Sponsor: American Library Association

Description: The Association seeks Military fiction published in the previous year. Children’s books not accepted—young adult and adult novels only.

BCALA Literary Awards

Prize: $500

Deadline: TBD

Sponsor: Black Caucus of the American Library Association

Description: For literary fiction, nonfiction, and poetry books as well as first novels. Books written by African Americans and published the previous year accepted.

John Gardner Fiction Book Award

Prize: $1,000

Deadline: 2/1/20

Sponsor: Binghamton University

Description: Seeks original novels or collections of fiction published the previous year.

Nelson Algren Short Story Award

Prize:

First: $3,500

Finalists (5): $750

Deadline: 2/17/20

Sponsor: Chicago Tribune

Description: Original, unpublished short stories under 8,000 words accepted for this award given in honor of the late Chicago writer.

Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize

Prize: $12,000 and publication

Deadline: 1/31/20

Sponsor: Graywolf Press

Description: Awarded to the most promising and innovative literary nonfiction project by a writer not yet established in the genre. Accepts memoirs, essays, biographies, histories, and more, but emphasizes innovation over straightforward memoirs.

New Voices Award

Prize: $2,000 and publication ($1,000 for the Honor Award winner)

Deadline: 8/31/20

Sponsor: Lee and Low Books

Description: Seeks a children’s picture book manuscript by a writer of color or a Native/Indigenous writer. Only U.S. residents who have not previously published a children’s picture book are eligible. Fiction, nonfiction, and poetry accepted that addresses the needs of children of color and Native nations by providing stories with which they can identify and which promote a greater understanding of one another. Work should be under 1,500 words.

St. Martin’s Minotaur / Mystery Writers of America First Crime Novel Competition

Prize: Publication and a $10,000 advance

Deadline: 1/3/20

Sponsor: Minotaur Books and Mystery Writers of America

Description: Seeks mysteries by writers who have never published a novel (not including self-publishing). Serious crime must be at the heart of the work.

Stowe Prize

Prize: $10,000

Deadline: TBD

Sponsor: Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

Description: Named for the abolitionist and author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, recognizes a U.S. author whose work has made a tangible impact on a social justice issue critical to contemporary society. Can be for a single work or a body of work (fiction or nonfiction) within two years of submission.

ServiceScape Short Story Award

Prize: $1,000

Deadline: 11/30/20

Sponsor: ServiceScape

Description: Accepts original, unpublished work (5,000 words or fewer) in any genre.

The Marfield Prize

Prize: $10,000

Deadline: TBD

Sponsor: The Arts Club of Washington

Description: Celebrates nonfiction books about an artistic discipline published the previous year.

Narrative Prize

Prize: $4,000

Deadline: 6/15/20

Sponsor: Narrative

Description: Awarded annually for the best short story, novel excerpt, poem, one-act play, graphic story, or work of literary nonfiction published by a new or emerging writer in Narrative.

Bacopa Literary Review Contest

Prize: $300

Deadline: 5/21/20

Sponsor: The Writers Alliance of Gainesville

Description: Seeks work in the categories of haiku, poetry, prose poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction

Jim Baen Memorial Short Story Award

Prize: $.08 per word and publication

Deadline: 2/1/20

Sponsor: National Space Society and Baen Books

Description: The National Space Society and Baen Books applaud the role that science fiction plays in advancing real science and have teamed up to sponsor this short fiction contest in memory of Jim Baen.

Hektoen Grand Prix Essay Competition

1st Prize: $3,000

2nd Prize: $800

Deadline: 1/25/20

Sponsor: Hektoen Institute of Medicine

Description: Seeks essays about medicine under 1,600 words. Topics might include art, history, literature, education, etc., as they relate to medicine.

James Laughlin Award

Prize: $5,000, an all-expenses-paid weeklong residency at The Betsy Hotel in Miami Beach, Florida, and distribution of the winning book to approximately one thousand Academy of American Poets members.

Deadline: Submissions accepted yearly between January 1 and May 15

Sponsor: The Academy of American Poets

Description: Offered since 1954, the James Laughlin Award is given to recognize and support a second book of poetry forthcoming in the next calendar year.

Parsec Short Story Contest

Prize:

First: $200

Second: $100

Third: $50

Deadline: 4/15/20

Sponsor: Parsec, Inc.

Description: This annual contest seeks science fiction, fantasy, and horror short stories from non-professional writers.

Owl Canyon Press Short Story Hackathon

Prize:

First: $3,000

Second: $2,000

Third: $1,000

Finalists (24): Publication

Deadline: TBD 2020

Sponsor: Owl Canyon Press

Description: Seeks stories with 50 paragraphs, but the first and twentieth paragraphs are provided by the judges.

Tony Hillerman Prize

Prize: Publication and a $10,000 advance

Deadline: TBD 2020

Sponsor: Western Writers of America and St. Martin’s Press, LLC

Description: Seeks unpublished mystery novels set in the Southwest by authors who haven’t previously published a mystery novel.

The Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing

Prize: $10,000 and publication

Deadline: 3/31/20

Sponsor: Restless Books

Description: Looking for complete, unpublished fiction manuscripts from emerging writers (unpublished) who are first-generation residents of their country.

Need help writing your novel? Click here to download Jerry’s ultimate 12-step guide.

Related Posts:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

How to Publish a Book: My Ultimate Guide from 40+ Years of Experience

How to Overcome Writer’s Block Once and for All: My Surprising Solution

The post Your Ultimate Guide to Writing Contests Through 2021 appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

December 23, 2019

Unique Gifts for Writers

I LOVE finding just the right gift for the people I most care about, don’t you?

Believe it or not, writers are easy—and fun—to buy for.

If you thought there weren’t many options beyond:

Paper and pensAn Amazon or bookstore gift cardA notebookA book by their favorite author

You’ll be happy with what my team and I have found!

Many great options exist, and I can even save you the time of searching for them.

Here, then, is a massive list of gifts for writers.

(Full disclosure: If you decide to purchase an item after clicking one of the links below, I may get a small commission at no extra cost to you. I promise to invest any and all such commissions directly into writer training.)

CONTENTS

Gifts for Young Writers Gifts for Aspiring Authors Home Decor Gifts for Writers Gifts Any Writer Would Love Tech Gifts for Writers Writing Tools High-Ticket Gifts for Authors

Gifts for Young Writers

The Writer’s Toolbox

Created by a creative writing teacher, the box is full of exercises designed to teach kids how to kickstart story ideas and sprinkle in plot twists.

Price: $22.11

Mad Libs Book

Mad Libs is a fun way for kids to practice different parts of speech and learn storytelling.

Includes Mad Libs about world history, dogs, unicorns, road trips, and even Frozen.

Price: From $4.99

Man Bites Dog

Have a budding journalist or blogger in the family? Man Bites Dog is a card game that can help them learn to write outrageous, attention-grabbing headlines.

Price: $7.85

The Storymatic Game

Draw two gold cards for the main character’s two defining characteristics and a copper card to reveal the situation or motivation.

Helps aspiring writers practice storytelling and stretch their imaginations.

Price: $29.95

Spilling Ink: A Young Writer’s Handbook 1st Edition

Spilling Ink is full of practical advice to give ambitious authors the direction to craft spellbinding stories.

Price: $7.79

642 Big Things to Write About: Young Writer’s Edition

642 Big Things to Write About is a journal full of prompts encouraging writers to think outside the box. For a budding writer who wants to practice short story writing or novel plotting.

Price: $19.06

Gamewright Rory’s Story Cubes

Rory’s Story Cubes is a pocket-sized creative story generator. Simply role the nine cubes and let your imagination run wild with an infinite number of ways to play. Contributes to literacy development, problem-solving, and storytelling abilities.

Price: $19.99

“Write On” T-shirt

From Etsy.

Choose from a range of colors and styles.

Price: From $22

Gifts for Aspiring Authors

Writing Magic: Creating Stories that Fly

Writing Magic teaches writers of all ages how to turn their ideas into spellbinding stories.

How to find ideasCreating intriguing beginnings and satisfying endings Character developmentWhat to do when you’re feeling stuck

Price: $6.98

Writer’s Market 2020

The Writer’s Market 2020 is one of the best gifts for writers ready to start making money from their work.

The comprehensive guide includes contact information for magazines, publishers, and literary agents who can help your writer get published.

Also includes information on:

Literary competitionsSubmission informationHow to market your writingCreating a business plan Crafting an attention-grabbing query letter

Price: From $14.99

The Elements of Style (Illustrated)

I read this at least once every year. The Illustrated Elements of Style guide is the go-to manual on clear, direct writing.

Price: $11.49

Writer’s Digest Critiques

If your writer has finished a manuscript and is eager to know if it has merit, consider gifting them a Writer’s Digest Critique. Few things can be more valuable and instructive to an aspiring writer than expert input.

Price: Varies by length of submission

On Writing by Stephen King

On Writing, is one of my favorites and is among the best books I’ve read on the craft.

Full of anecdotes and tips, it tells his story of going from unknown and unpublished to one of the most celebrated writers of our day..

Warning: Not for kids. Contains adult language.

Price: $15.14

Plot & Structure by James Scott Bell

Plot & Structure is a book every writer should read. Written by a longtime friend and colleague, it’s a resource I often refer to often in my blog. A great gift for beginners to experts.

Price: $12.77

Writer Emergency Pack

Have a writer friend who’s feeling stuck? The Writer Emergency Pack could be the perfect gift.

It helps weed out plot holes, spice up bland characters, and pose questions that lead to intriguing solutions.

Price: $9.99

The 3 A.M. Epiphany: Uncommon Writing Exercises that Transform Your Fiction

The 3 A.M. Epiphany takes authors out of their comfort zones and throws them into impossible situations — making for compelling fiction.

Designed to stretch the imagination and transform stale writing.

Price: $12.75

The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Expression

The Emotion Thesaurus includes over 130 entries on facial expressions, mental responses, and body language to help writers show characters’ emotions, rather than telling readers about them.

Price: $17.09

Home Decor Gifts for Writers

Custom Typewriter Pillow

Searching for personalized gifts for writers?

This pillow from Etsy may be the answer.

You can customize it with a personal message, their favorite quote, a joke, or even the title of their book.

Price: $31

Bathtub Book Caddy

The book caddy lets your writer enjoy a book hands-free.

Price: $29.98

Gifts Any Writer Would Love

Audible Subscription

Audible Subscriptions make great gifts for writers. I listen to one book or another every day — while working out, walking, driving, or waiting in line. And the list of titles is endless!

Price: From $15

“I’m Plotting” T-shirt

Stocking stuffer gifts don’t have to be boring.

The “I’m Not Quiet, I’m Plotting” T-shirt from Etsy is costs less than $20 and is sure to be a hit.

Price: $14.40

Writers Gonna Write Pencil Set

The “Writers Gonna Write” pencil set includes six No. 2 pencils with phrases like “I’d Rather Be Writing” and “Write. Edit. Repeat” embossed in gold foil.

Price: $10

A Wireless Typewriter Keyboard

This is one of my all-time favorite purchases! In fact, I have one of these for each of my desktop computers. I enjoy the look and feel (and sound) of my first manual typewriter but with all the bells and whistles the modern keyboard needs.

Price: $269.99

The Little Literary Cookbook

The Little Literary Cookbook is the perfect companion for writers looking to whip up a dose of inspiration from their favorite books.

Make Paddington Bear’s famous marmalade, decadent Queen of Hearts tarts, and The Great Gatsby’s classic Mint Julep.

Price: $14.89

The Book HookUp Subscription Box

The Book HookUp Subscription Box comes in themes such as Political Nonfiction, Mystery, Fantasy, and more, making it easy to select a genre your friend will love.

The subscription box is sent quarterly and includes a signed first edition of a highly anticipated title, a paperback, and other literary goodies.

A single box is $50, and a full-year subscription is $200.

Price: $50-$200

Tech Gifts for Writers

Kindle + Kindle Unlimited Subscription

Kindle’s Paperwhite is the lightest, thinnest, and most durable model. It’s waterproof, glare-free, and has twice the storage of previous models.

A subscription to Kindle Unlimited gives members access to over one million titles and thousands of audiobooks.

Price: $129.99

Dragon Naturally Speaking Software

I swear by this technology. I find some use for it everyday, and it really saves time.

They’re improving the technology all the time, so opt for the latest version you can afford.

Price: $150

Writing Tools

Grammarly Premium

Whether your writer is penning their debut novel or writing blogs, Grammarly can help them nail their punctuation and grammar.

The premium subscription is full of features like style suggestions, sentence structure checks, and a plagiarism checker to give any piece of writing the final polish it needs.

Price: From $29.95

Scapple

Scapple is a powerful tool that helps writers see connections between ideas.

It can prove a useful gift for writers who want a visual way to track their structure.

Price: $17

Scrivener

Scrivener is one of the most popular writing tools on the market. The editing software lets you keep track of all your ideas, common themes, and words throughout your manuscript.

I’ve found its most valuable feature is the virtual cork board that allows me to organize all my research in one place and arrange it in whatever order I choose.

Price: $44

ProWritingAid

ProWritingAid is a powerful grammar checker, style editor, and writing mentor, employing several search lists to evaluate your manuscript.

It’s a great gift for writers of all levels and can greatly assist in self-editing.

Price: $70 per year

High-Ticket Gift Ideas for Authors

Writers Retreats

One of the most valuable and inspirational gifts for a writer, a retreat can take them to a far-flung destinations to solely focus on their work.

Feedback from an expert in publishing will improve their writing.

Price: $1,000+

Resources:

https://thewritelife.com/writing-retreats/https://www.juniperediting.com/new-blog/10-amazing-writing-retreats-in-canada-and-usahttp://www.oneworld365.org/blog/most-inspiring-writers-retreats-in-the-world

Creative Writing Workshops & Courses

An online writing workshop can help writers hone their skills and solve the problems stopping their manuscript from selling.

Find a creative workshop or gift an online writing course on a specific topic like editing or storytelling.

Price: $49 – $1,997+

Professional Editing

A session with a professional editor could save your favorite writer hundreds of hours of writing in the wrong direction and get them feedback on their strengths and weaknesses.

Price: From $350

A Weekend Getaway

Quality writing often comes from having time to process ideas and reflect.

If the writer in your life displays signs of cabin fever, a weekend away might help.

And it doesn’t have to break the bank.

Book them a room at a nice hotel nearby.

Price: From $130

The post Unique Gifts for Writers appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

November 12, 2019

12 Character Archetypes You Can Use to Create Heroes Your Reader Will Love

Guest post by Tami Nantz

There’s no way around it:

If you want to write a story that pulls in readers, you must include compelling characters.

They need to feel:

BelievableMysteriousRelatable

But that’s difficult to pull off—one reason most stories are unpublishable.

Maybe you’re feeling this tension right now.

Maybe you’ve created a character with an amazing backstory that includes everything from where he was born to his hair and eye color, where he works, who his best friends are, and what hobbies he enjoys.

Yet it’s obvious something is still missing. And you can’t put your finger on what that is.

That’s why I wrote this character archetype guide: to give you a shortcut to giving your characters a set of desires, fears, and struggles that feel familiar—and because of that, believable.

For a character to be believable, he needs to be realistic.

[I use male pronouns inclusively here to represent both genders to avoid the awkward he/she or him/her, fully recognizing that many lead characters are female, as are a majority of readers.]