Jerry B. Jenkins's Blog, page 14

April 16, 2019

4 Ways to Create Tension in Your Story

Guest post by Bridget McNulty

Tension is the secret sauce that ensures that “I’ll read just one more page before bed” feeling. Four ways to ensure your story has the right amount:

1. Create a conflict your characters care about

Before you plan your story’s main conflicts, choose carefully. You want to create conflict that your characters care about. What does your character want to achieve and what could stand in their way? Conflict can be as seemingly insignificant as an internal struggle or a relationship breaking down. Or it can be as large as fate itself.

What matters is not the size of the conflict but how much the character (and thus the reader) cares about the outcome. The conflict must threaten the things most important to your characters. The first step? Work out your characters’ first goals and the rising and falling action.

2. Allow an ebb and flow of tension

The last thing you want is for your story to read like an endless episode of The Amazing Race — with tension after tension and no breathing spaces. Your goal is to keep people reading, not to wear them out! You need quiet periods to build character and subtle plot points — gaps in the excitement to let readers fall in love with the characters.

It’s important to pace your suspense, and while the big moments may grow until you reach the climax at the end of the book, along the way there should be smaller moments of tension and ease, too.

3. Raise the stakes — again and again

Your story will be too quick (and predictable) if your protagonist tries something and immediately succeeds. To maintain suspense and tension, your protagonist needs to try and fail a number of times. Or, if they succeed in reaching their goal at first, adverse consequences must lurk in the background.

To ensure rising conflict throughout, keep in mind the rule of threes. This simply means there should be two unsuccessful attempts to solve a problem before the third succeeds. Don’t you often try a few times before you succeed? We want art to mirror life in this way.

Brainstorm rising and falling plot points and create two situations that take your character further from where they want to be before an event improves their situation. This is less a hard-and-fast rule than a reminder that success is often hard-won — the interesting and exciting type of success, that is!

4. Keep your reader curious

How did you feel the last time you read a really great book? Curious, engaged, excited? One of the keys to sustaining tension in a story is to keep the reader asking questions — particularly important for keeping readers engaged in the quieter moments of your story.

Essential to keeping your reader curious is to create characters who are interesting even when not in a state of emergency. Weave in questions your readers want answered. Try to raise these at the ends of chapters in particular, so you create a sense of propulsion to the next event — just enough so the one-more-page-before-bed becomes another, and another, and another.

Bridget McNulty is an author, journalist, and editor. She studied Creative Writing at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, before writing her first novel. Bridget is also cofounder of NowNovel.com.

Similar Posts

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

How to Write a Novel: A 12-Step Guide

How to Overcome Writer’s Block Once and For All: My Surprising Solution

The post 4 Ways to Create Tension in Your Story appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

March 26, 2019

How to Get a Literary Agent (And Why You Need One)

Book publishing can be…

ConfusingComplicatedStressful

Especially when you face it alone.

But even I don’t try to navigate the publishing world by myself, despite having been an author, an editor, a publisher, and a writing coach over the last 45 years.

That’s why I have an agent.

To land a traditional publishing deal—where the publishing house pays you and takes 100% of the financial risk, you’ll need an agent, too.

But know this: While you may be writing out of your passion for a burning message you want to share with the world, agents might appear to base their decisions solely on money.

But don’t despair.

That doesn’t mean they don’t share your passion—in fact you wouldn’t want an agent UNLESS they shared it. It simply means they must make a profit to stay in business

You want a literary agent who also:

Likes you Clicks with youKnows the publishing landscapeHas enjoyed success in your genreCarries an impeccable reputation

What A Literary Agent Does

He (and I’m using He inclusively here to represent men or women agents) handles the business side of your career, representing your writing to publishers.

While you would still work directly with the publishing house’s editor and proofreader, your agent would negotiate your agreement so you can stay in your lane.

It’s difficult to negotiate for yourself, even if you’re a veteran in the publishing industry.

Ultimately, an agent’s job is to make you money. He profits only when you do.

He receives thousands of manuscripts every year, searching for the next mega-bestseller, that rare gem that captures his attention so completely he forgets he’s reading.

That’s the one he will shop to publishers on the writer’s behalf.

He will negotiate every clause in the publishing contract to secure the best deal for the author.

Standard commission for a U.S.-based agent is 15% of all proceeds from the book, and 20% of any international income.

A common question is whether it makes sense for a writer to cede 15% of his income to an agent.

The answer is yes. It is unlikely you could negotiate a deal at the level an agent can, and they earn their cut.

What A Literary Agent Doesn’t Do

Landing an agent does not guarantee you a publishing deal.

Your agent will be your cheerleader and should guide you to your best work.

He may even help fine tune your manuscript before he submits it anywhere. But he not your editor, nor is it his job to rework your manuscript.

Do You Need a Literary Agent to Get Published?

Besides the instant credibility of an agent’s interest—establishing that you and your writing has survived a rigorous vetting process, you’ll also get valuable input and coaching on how to fashion your query and proposal.

Though it’s as hard to find an agent as it is to find a publisher, it’s nearly impossible to get traditionally published without one.

Most publishers do not accept unsolicited manuscripts, but even those who do would insist that you find representation if they offer a contract, so there will be no question they took advantage of you.

They might recommend a specific one, but you should do your own due diligence to find your own.

How to Get a Literary Agent

Check The Writer’s Market Guide for agents who specialize in the general market or The Christian Writer’s Market Guide for agents in the Inspirational market.

Where else to look:

Friends in the industry who might recommend someone PublishersMarketplace.com AgentQuery.com

I’m not going to sugarcoat it: the process is difficult.

Writing and publishing coach Jane Friedman likens it to finding a spouse—a deeply personal search best done by you alone.

How do you know who to trust? A credible agent welcomes scrutiny. Find reviews. Check with clients they represent.

Once you’ve determined potential agents who ply their trade in your genre, follow their submission guidelines to a T.

They’ll ask for a query letter, synopsis, fiction or nonfiction book proposal, and sample chapters.

If you’re new author, they may want to see a finished manuscript. (For help with your Query Letter, see my post How to Write A Query Letter That Grabs an Agent’s Attention)

If an agent asks for any sort of reading fee or other payment, eliminate them as candidates. Legitimate agents make their money placing your manuscript with a publisher.

Review the submission guidelines from these agents with whom I’m familiar:

Steve Laube’s guidelines

Hartline Literary’s guidelines

Their pages are helpful and sound and will give you an idea of what typical agents look for.

Once I’ve Submitted, Now What

Some agents say that if you get no response after a certain period, assume they’re not interested.

I find that rude. Sometimes you’re not even told they received your material. In that case, wait six weeks and follow up with a kind note asking about the status.

Ideally the agent asks for more. That’s rare, but it happens.

Agents reject nearly all submissions, usually within minutes.

Too many writers give them too many reasons.

My goal is to get you to where an agent sees you and your writing as the next success. That’s why they’re in the business.

They’re longing to discover the next bestseller. Be the one who writes it.

Related posts:

How to Improve Your Writing Skills: 15 Simple Tips

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

How to Write a Novel: A 12-Step Guide

The post How to Get a Literary Agent (And Why You Need One) appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

February 26, 2019

The Writer’s Guide to Creating the Plot of a Story

Great page-turning stories live or die by their plots.

“I took the dog to the park” doesn’t interest me.

“You won’t believe what happened when I took the dog to the park” interests me. I want to know what happened, so I’ll stick with you as long as your story holds me.

To keep me turning the pages of your book, you need a plot that grabs me by the throat and keeps me with you to the end.

So What Is the Plot of a Story?

Plot is the sequence of events that makes up your story. It’s what compels your reader to either keep turning pages or set your book aside.

Think of Plot as the engine of your novel.

A successful story answers two questions:

1. What happens?

2. What does it mean?

What happens is your Plot.

What it means is your Theme.

For example, my novel Riven has two lead characters—Brady Wayne Darby (a no-account loser from a broken home) and Thomas Carey (a struggling small church pastor).

Their lives initially play out in separate settings, but eventually their stories intersect. My Theme ties the stories together: The extent of forgiveness for even the most heinous crime..

Can Thomas forgive those who’ve treated him so shabbily that his own daughter has abandoned her faith?

Can Brady Darby be forgiven for the ultimate mortal sin?

Ideally your readers think for days about your theme. They may remember the plot, but they should chew on the theme.

Digging Deeper: 7 Plot Types

While stories seem limitless, most plots fall into these categories:

1. Adventure: A person goes to new places, tries new things, and faces myrid obstacles. Examples: Harry Potter, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Chronicles of Narnia, Gulliver’s Travels, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.

2. Change: A person undergoes a dramatic transformation. Examples: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Great Expectations, Beauty and the Beast, A Little Princess, Don Quixote, Moby Dick, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, The Lord of the Rings.

3. Romance: Jealousy and misunderstandings threaten lovers’ happiness. Examples: Sense and Sensibility, Titanic, The Fault in Our Stars, The Notebook, Wuthering Heights, Water for Elephants, Redeeming Love.

4. Mistake: An innocent person caught in a situation he doesn’t understand must overcome foes and dodge dangers he never expected. Examples: Indiana Jones, Finding Nemo, The Color Purple, To Kill a Mockingbird, Left Behind.

5. Lure: A person must decide whether to give in to temptation, revenge, rage, or some other passion. He grows from discovering things about himself. Examples: The Green Mile, Shawshank Redemption, Riven, A Christmas Carol, Les Miserables, The Scarlet Letter, Of Mice and Men, The Hobbit, MacBeth, The Pearl, Oliver Twist, The Secret Life of Bees, Animal Farm.

6. Race: Characters chase wealth or fame but must overcome others to succeed. Examples: The Great Gatsby, Catch 22, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Treasure Island, Chariots of Fire, The Pursuit of Happyness, The Devil Wears Prada.

7. Gift: An ordinary person sacrifices to aid someone else. The lead may not be aware of his own heroism until he rises to the occasion. Examples: A Prayer for Owen Meany, The Red Badge of Courage, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Odyssey, The Green Mile, Charlotte’s Web, Schindler’s List.

Regardless which basic plot you choose, your goal should be to grab your reader by the throat from the get-go and never let go.

Plot Development Secrets

Ask yourself two questions: Is your story idea weighty enough to warrant 75,000 to 100,000 words, and Is it be powerful enough to hold the reader to the end?

Discovering novelist Dean Koontz’s Classic Story Structure (in his How to Write Best-Selling Fiction) was the best thing that ever happened to my career. I immersed myself in this book in the 1980s, and my writing has never been the same. It has informed every novel I’ve written since, and several have sold in the tens of millions.

If, like me, you’re not an Outliner but write by the seat of your pants (we call ourselves Pantsers), don’t panic—this is just a basic structure, not an outline. But, even we Pantsers need a basic idea where we’re headed.

Dean Koontz’s Classic Story Structure

1. Plunge your main character into terrible trouble as soon as possible.

The terrible trouble depends on your genre, but in short it’s the worst possible dilemma you can think of for your main character. For a thriller it might be a life or death situation. In a romance novel, it could mean a young woman must decide between two equally qualified suitors—and then her choice is revealed a disaster.

Just remember, this trouble must bear stakes high enough to carry the entire novel.

One caveat: whatever the dilemma, it will mean little to readers if they don’t first find reasons to care about your character. The trouble is seen in an entirely different light once a reader is invested in the character.

2. Everything your character does to try to get out of that trouble makes it only worse…

Avoid the temptation to make life easy for your protagonist.

Every complication must be logical (not the result of coincidence), and things must grow progressively worse.

3. …until the situation appears hopeless.

Novelist Angela Hunt refers to this as The Bleakest Moment. Even you should wonder how you’re ever going to write your character out of this.

Make your predicament so hopeless that it forces your lead to take action, to use every new muscle and technique gained from facing a book full of obstacles to become heroic and prove that things only appeared beyond repair.

4. Finally, your hero learns succeeds against all odds..

Reward readers with the payoff they expected by keeping your hero on stage, taking action. Give them a finish that rivets them to the very last word.

Beware These Deadly Plot Killers

Beginning with chapter one, page one, your singular mission is to make every word count.

Gone are the days when a reader enjoyed curling up with a book and spending the first hour or two by immersing herself in the beauty of the setting and culture. These are important, certainly, and must be woven into the narrative as seasoning.

But today’s readers have nanosecond attention spans. By the end of the first page, they should be hooked.

One final piece of advice: avoid main characters who can do no wrong.

Heroes should be fundamentally likable, but we need to see their struggles too. They shouldn’t be wimps or cowards, but they must have imperfections. Character arc is crucial to a successful plot.

Villains must be three-dimensional too. Yes, even bad guys need a soft side, a weak spot, maybe even a modicum of generosity. And their evil has to have some genuine motivation. No one is simply mean for no reason.

Adding dimension to your characters gives dimension to your plot.

More in-depth plotting resources

Plot and Structure by James Scott Bell The Secrets of Story Structure by K. M. Weiland The Snowflake Method by Randy Ingermanson

Novels worth studying

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three by Morton Freedgood11/22/63 by Stephen KingPresumed Innocent by Scott Turow

As novelists, you and I have one job: to invent a story for readers that delivers a satisfying experience. Readers love to be educated and entertained, but they never forget what moves them.

Stephen King advises, “Put interesting characters in difficult situations and write to find out what happens. But you’ll find that a whole lot easier if you take the time to develop the plot of your story using the powerful tools above.

Related Posts:

How to Improve Your Writing Skills: 15 Simple Tips

How to Publish a Book: My Ultimate Guide From 40+ Years of Experience

Writing Tips 40 Experts Wish They’d Known as Beginners

The post The Writer’s Guide to Creating the Plot of a Story appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

January 29, 2019

Got Subtext? Writing Better Dialogue

Guest post by Becca Puglisi

Realistic, evocative dialogue is an important part of any successful story. We need our characters’ interactions to be authentic, consistent, and engaging to draw readers in to what’s happening. So when we’re learning to write, we spend a lot of time on mechanics—learning all the grammar and punctuation rules. But proper form is just the first step.

When writing strong dialogue, we often forget that real-life conversations are rarely straightforward. On the surface, it may seem we’re engaging in simple back-and-forth, but if you look deeper, to some degree our conversations are carefully constructed. We hide our emotions, withhold information, dance around what we really mean, avoid certain topics, downplay shortcomings, or emphasize strengths—all of which leads to exchanges that aren’t totally honest.

Completely candid dialogue scenes fall flat because that’s not the way people converse. Subtext plays a huge role in conversation. It’s often tied to how characters are feeling, which can trigger readers’ emotions and increase their engagement. So we need to include this crucial element in our dialogue scenes.

Simply, subtext is the underlying meaning. Hidden elements the character isn’t comfortable sharing—their true opinions, what they really want, what they’re afraid of, and emotions that make them feel vulnerable—constitute the subtext. They’re important because the character wants them hidden. This results in contradictory words and actions.

A Subtext Example

Consider this exchange between a teenaged daughter and her dad.

“So how’d the party go?”

Dionne plastered on a smile and buried herself in Instagram. “Great.”

“See, I knew you’d have a good time. Who was there?”

Her mouth went dry, but she didn’t dare swallow. Despite the hour, Dad’s eyes shone and searched, spotlights carving her mocha-infused fog.

“The usual. Sarah, Allegra, Jordan.” She shrugged. Nothing to see here. Move along.

“What about Trey? I ran into his mom at the office yesterday and she said he was going.”

“Um, yeah. I think he was there.” She scrolled, images blurring.

“He sounds like a good kid. Maybe we could have him and his mom over for dinner.”

Her stomach lurched. “Oh, I don’t know.” Her fingers trembled, so she abandoned the phone and sat on her hands to keep them still. “We don’t really hang with the same crowd.”

“Well, think about it. Couldn’t hurt to branch out and get to know some new people.”

Dionne blew out a shaky breath. How could her dad be so smart at work and so stupid about people?

Something happened at the party involving a boy Dionne’s now avoiding, and she clearly doesn’t want her father to know about it. While Dad is kept in the dark, the reader becomes privy to Dionne’s true emotions: nervousness, fear, and possibly guilt.

This is the beauty of subtext in dialogue. It allows the character to carry on whatever subterfuge she deems necessary while revealing her true emotions and motivations to the reader. It’s also a great way to add tension and conflict. Without subtext, this scene is boring, just two people chatting. With it, we see Dionne desperately trying to keep her secrets while it becomes increasingly difficult—even unhealthy—to do so.

So how do we write subtext into our characters’ conversations without confusing the reader? It just requires combining five common vehicles for showing emotion. Let’s look at how these were used in the example.

1. Dialogue

We all go a little Pinocchio when we start talking, and Dionne is no exception. Her words scream status quo: nothing happened at the party and she doesn’t feel anything in particular. But the reader can clearly see this isn’t the case.

2. Body Language

Nonverbal communication often reveals to readers the truth beneath a character’s words. Notice Dionne’s body language: the plastered-on smile, frantic social media scrolling, and trembling hands. Readers hear what she’s saying, but her body language clues them in that something else is going on.

3. Visceral Reactions

These are the internal physical responses to high emotion. They’re not visible, but the point-of-view character will likely reference them, since they’re so strong. Here, Dionne’s dry mouth and lurching stomach contradict her claims that everything went swimmingly at the party.

4. Thoughts

Because they’re private, thoughts are honest. Dionne’s mental musings (nothing to see here; move along) show that she desperately wants her father to drop this line of questioning. And her final bit of internal dialogue reinforces that she knows something he doesn’t. Because there’s no reason for characters to disguise their thoughts, this can be the best vehicle for showing readers the truth behind the words.

5. Vocal Cues

We choose our words carefully when we’re hiding something; we may even do certain things with our body to fool others. But when emotions are in flux, the voice often changes, and at first, there’s nothing we can do to stop it. Shifts in volume, pitch, timbre, and speed of speech happen before the character can force the voice back into submission. So variations in vocal cues can show readers that not all is as it seems.

Nonverbal vehicles are like annoying little brothers and sisters, tattling on the dialogue and revealing true emotion. Put them all together and they fill out the character’s narrative and paint a complete picture for readers. And you’ll end up with nuanced and emotionally layered dialogue that can intrigue readers and pull them deeper into your story.

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and author. Her latest publication is a second edition of the bestselling Emotion Thesaurus, an updated and expanded version of the bestselling original volume. Her books are used by novelists, screenwriters, editors, and psychologists around the world. You can find Becca at her Writers Helping Writers blog and her website for authors, One Stop For Writers.

Related Posts:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

How to Write a Novel: A 12-Step Guide

How to Publish a Book: My Ultimate Guide From 40+ Years of Experience

The post Got Subtext? Writing Better Dialogue appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

January 8, 2019

How To Write a Query Letter That Grabs an Agent’s Attention

You’ve done the hard part.

You’ve spent ages researching, writing, and rewriting until you finally feel your book is ready to share with the world.

Not so fast.

Your next step is one of the most important. Writing a query letter can determine whether a literary agent asks to see more or sends you a cordial form letter intended to let you down easy.

It’s time to move from author to salesman.

You’re about to make a virtual sales call, and your query letter makes the first impression.

Nothing can be more important.

What is a Query Letter?

It was once customary for a bachelor to request permission to call on a woman by having his calling card delivered to her.

You’re courting an agent on behalf of your manuscript, and the query letter is your calling card.

This one-page letter must masterfully sell. Write it poorly and an agent will assume your book is also poorly written.

It must stimulate and intrigue to secure your all-important first date.

A Query Letter Format That Makes Agents Take Notice…

1—Speaks to a specific person.

Get the agent’s name and title right. You’re not sending this “To Whom It May Concern.”

It should be clear you’ve done your research and are targeting an agent who represents your genre and that you’re aware of similar books he has represented to publishers.

2—Presents your book idea simply.

Include a one-sentence summary. Here was mine for my first novel: “A judge tries a man for a murder the judge committed.”

It worked.

3—Evidences your style.

Grab the agent with compelling writing. Briefly tell the plot of your novel or the purpose of your nonfiction book. Write with the same voice you’d use when telling your best friend about it. Your passion must be obvious.

4—Show you know who your readers are.

An agent needs to believe he can sell your book before he’ll ask for more.

Be specific about your target audience, and “everyone” doesn’t count. Agents know the business and cannot be persuaded that “everyone will find this amazing.”

Tell what you hope readers will take away from your book and why.

5—Clarifies your qualifications.

Briefly summarize why you’re the one to write this book.

What else have you published? What platform have you built? What education do you have? Link to your website.

The more you’ve done, the less you need say about it. Don’t emphasize your lack of experience, but resist the urge to exaggerate or embellish.

You need not list your entire resume. Instead, refer to a web page where an agent can find more details.

Better to just say something like, “I’ve been a professor of astrophysics for more than two decades, the last four years at Notre Dame.”

An amazing book idea can even transcend the need for a vast platform. So if you don’t have one, it’s all the more important to well represent the potential of your book.

6—Exhibits your flexibility and professionalism.

Keep it brief and express your ability to provide whatever is requested: proposal, synopsis, sample chapters, whatever. Conclude with a simple “Thanks for your consideration. I look forward to hearing from you.”

Be sure to:

Include your book’s genre, title, and expected word count.

Properly format: limit yourself to a single page, single-spaced, and use a 12 pt. serif type. The shorter your letter the better, but say what you need to.

Follow the agent’s submission guidelines to a T, including how to send (via email attachment, not as an attachment, by snail mail [rare], etc.).

Query Letter Examples

Here’s a great example with a breakdown of why it works, by Brian Klems of Writer’s Digest.

Study Writer’s Digest’s list of successful query letters .

Cardinal Sins

Overselling—let your premise speak for itself.

Gushing, flattering, or waxing obvious, like, “You’ll notice I got it to you early, because I’m so excited,” or “I hope you like it.” Represent yourself as more potential colleague than fan. Be professional.

Submitting more than one page. Trust me, your query will be ignored if it’s too long.

Querying only one agent at a time. Volume is your friend.

Typos. Proofread! Then proofread it again. Even one typo in such a short document smacks of amateurism. Have someone read it with fresh eyes.

“I sent my query letter, now what do I do?”

Be patient. Occupy yourself with your next project idea.

Some agencies say that if you get no response after a certain period, assume they’re not interested. That’s rude, and sometimes you’re not even told whether they received it in the first place. In that case, wait six weeks and follow up with kind note asking about the status.

Best case: the agent reads your query and immediately asks for more. That’s rare, but it happens.

Agents get thousands of submissions, and they reject most of them within minutes.

Too many writers give them too many reasons.

My goal is to get you to where you’re seen as the next success. That’s why agents are in the business.

Despite how many ideas they reject, they’re longing to discover the next bestseller. Be the one who writes it!

Related Posts:

How to Write a Short Story That Captivates Your Reader

Writing Tips 40 Experts Wish They’d Known As Beginners

The Ultimate Guide to Character Development: 10 Steps to Creating Memorable Heroes

The post How To Write a Query Letter That Grabs an Agent’s Attention appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

December 6, 2018

Your Ultimate Guide to Writing Contests Through 2019

Regardless where you are on your writing journey—from wannabe to bestseller—you can benefit from entering contests.

Why?

Because the right contest can tell you:

Where you stand

How you measure up against the competition

What you still need to learn

Not to mention, you could win prizes. :)

That’s why my team and I conducted extensive research to not only find free, high-quality writing contests, but to also give you the best chance to win.

(We’ll update this post frequently with new writing contest details.)

Need help writing your novel? Click here to download my ultimate 12-step guide.

Free Writing Contests

53-Word Story Contest

Prize: Publication, a free book from Press 53

Deadline: Frequent contests

Sponsor: Prime Number Magazine

Description: Each month Prime Number Magazine invites writers to submit a 53-word story based on a prompt.

The Crucible

Prize: $150 1st, $100 2nd

Deadline: 5/1/19

Sponsor: Barton College

Description: Crucible and the Barton College Department of English welcome all writers to submit original, unpublished poems and stories. Writers are limited to 5 poems and stories no longer than 8,000 words. Entries must not be entered in other competitions.

The Jeff Sharlet Memorial Award for Veterans

Prize:

1st: $1,000 and publication in The Iowa Review

2nd: $750

3rd (3 selected): $500

Deadline: 5/1/20 – 5/31/20

Sponsor: The Iowa Review

Description: Due to a donation from the family of veteran and antiwar author, Jeff Sharlet, The Iowa Review is able to hold The Jeff Sharlet Memorial Award for Veterans. Note: Only U.S. military veterans and active duty personnel may submit writing in any genre about any topic.

St. Francis College Literary Prize

Prize: $50,000

Deadline: 5/15/19

Sponsor: St. Francis College

Description: For mid-career authors who have just published their 3rd, 4th, or 5th fiction book. Self-published books and English translations are also considered.

New Writers Awards

Prize: $500

Deadline: 7/25/18

Sponsor: Great Lakes Colleges Association

Description: Every year since 1970, the Association has honored newly published writers with an award for a first published volume of poetry, fiction, and creative non-fiction. Note: Publishers (not the writers) are invited to submit works that “emphasize literary excellence.” All entries must be written in English and published in the United States or Canada.

Young Lions Fiction Award

Prize: $10,000

Deadline: TBD 2019

Sponsor: New York Public Library

Description: Each Spring, the Library gives a writer 35 years old or younger $10,000 for a novel or a collection of short stories. This award seeks to encourage young and emerging writers of contemporary fiction.

The Iowa Short Fiction Award

Prize: Publication in the University of Iowa Press

Deadline: TBD 2019

Sponsor: University of Iowa Press

Description: Seeking 150-page (or longer) collections of fiction by writers who have not previously traditionally published a novel or fiction collection.

Pen/Faulkner Award for Fiction

Prize: $15,000

Deadline: TBD 2019

Sponsor: Pen/Faulkner

Description: Mary Lee established the Award in 1980 to recognize excellent literary fiction. It accepts published books and is peer-juried. The winner is honored as “first among equals.”

Friends of American Writers Literary Award

Prize: $1,000 – $2,000

Deadline: 12/10/18

Sponsor: Friends of American Writers Chicago

Description: Current or former residents of the American Midwest (or authors whose book takes place in the Midwest) are invited to submit to the FAW Literary Award. Published novels or non-fiction books are welcome.

Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards

Prize: $10,000

Deadline: 12/31/18

Sponsor: Cleveland Foundation

Description: The Award seeks fiction, poetry, and nonfiction books published the previous year “that contribute to our understanding of racism and our appreciation of cultural diversity.” Self-published work not accepted.

Christopher Doheny Award

Prize: $10,000

Deadline: TBD 2018

Sponsor: The Center for Fiction

Description: Recognizes excellence in fiction or creative nonfiction on the topic of serious physical illness. The award is presented annually for a completed manuscript that has not yet been published. It was founded in honor of Audible employee Chris Doheny, a writer himself, who was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis as a baby and passed away on February 20, 2013. The winner of the award must demonstrate both high literary standards and a broad audience appeal while exploring the impact of illness on the patient, family and friends, and others.

Cabell First Novelist Award

Prize: $5,000

Deadline: 12/31/19

Sponsor: Virginia Commonwealth University

Description: Seeks to honor first-time novelists “who have navigated their way through the maze of imagination and delivered a great read.” Novels published the previous year are accepted.

The Gabo Prize

Prize: $200

Deadline: TBD

Sponsor: Lunch Ticket

Description: Awards translators and authors of multilingual texts (poetry and prose) with $200 and publication in Lunch Ticket.

Transitions Abroad Expatriate and Work Abroad Writing Contest

Prize: $500

Deadline: 9/1/19

Sponsor: Transitions Abroad Publishing, Inc.

Description: Seeking inspiring articles or practical mini-guides that also provide in-depth descriptions of your experience moving, living, and working abroad (including teaching, internships, volunteering, short-term jobs, etc.).” Work should be between 1,200-3,000 words. All writers welcome.

Short Fiction Prize

Prize: $1,000

Deadline: 6/1/18

Sponsor: Stoney Brook University

Description: Seeking short stories by undergraduates at American or Canadian colleges.

The Wallace Stegner Prize in Environmental Humanities

Prize: $5,000

Deadline: 12/30/19

Sponsor: The University of Utah Press

Description: Wallace Stegner was a student of the American West, an environmental spokesman, and a creative writing teacher. In his memory, the University of Utah Press seeks book-length monographs in the field of environmental humanities. Projects focusing on the American West preferred.

Drue Heinz Literature Prize

Prize: $15,000

Deadline: 6/30/19

Sponsor: University of Pittsburgh Press

Description: Seeks short fiction collections. Writers who have published a novel or a book-length collection of fiction with a traditional book publisher, or a minimum of three short stories or novellas in magazines or journals of national distribution are accepted.

Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence

Prize: $10,000

Deadline: TBD 2019

Sponsor: Baton Rouge Area Foundation

Description: Honors novels and story collections by African American writers. Entries that will be published in 2019 are accepted.

Brooklyn Nonfiction Prize

Prize: $500

Deadline: TBD

Sponsor: Brooklyn Film & Arts Festival

Description: Showcases essays set in Brooklyn. Five authors will be asked to read their pieces at the Brooklyn Film & Arts Festival.

International Flash Fiction Competition

Prize: $20,000

Deadline: TBD

Sponsor: The César Egido Serrano Foundation

Description: With over 40,000 participants last year, this prize invites authors to submit flash fiction in Spanish, English, Arabic, and Hebrew.

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction

Prize: $1,000

Deadline: 12/1/19

Sponsor: Langum Charitable Trust

Description: To make American history accessible to general educated readers, the Trust seeks American historical novels published in the previous year. Novels should take place in America before 1950 (split-time novels accepted). Novels set outside American but including American values and characters accepted (such as about the American military). Self-published novels not accepted.

Y. Boyd Literary Award

Prize: $5,000

Deadline: 12/1/18

Sponsor: American Library Association

Description: The Association seeks Military fiction published in the previous year. Children’s books not accepted—young adult and adult novels only.

Thomas and Lillie D. Chaffin Award

Prize: $1,000

Deadline: 12/1/18

Sponsor: Morehead State University

Description: Accepts outstanding books of all genres by Appalachian writers. Writers will have the opportunity to interact with students.

BCALA Literary Awards

Prize: $500

Deadline: 12/31/18

Sponsor: Black Caucus of the American Library Association

Description: For literary fiction, nonfiction, and poetry books as well as first novels. Books written by African Americans and published the previous year accepted.

Desert Writers Award

Prize: $5,000

Deadline: 1/15/19

Sponsor: Ellen Meloy Fund

Description: Accepts proposals for creative nonfiction about the desert that reflects the spirit and passions embodied in Ellen’s writing and her commitment to a “deep map of place.”

John Gardner Fiction Book Award

Prize: $1,000

Deadline: 2/1/19

Sponsor: Binghamton University

Description: Seeks original novels or collections of fiction published the previous year.

Nelson Algren Short Story Award

Prize: $3,500

Deadline: 1/31/19

Sponsor: Chicago Tribune

Description: Original, unpublished short stories under 8,000 words accepted for this award given in honor of the late Chicago writer.

Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize

Prize: $12,000 and publication

Deadline: TBD 2020

Sponsor: Graywolf Press

Description: Awarded to the most promising and innovative literary nonfiction project by a writer not yet established in the genre. Accepts memoirs, essays, biographies, histories, and more, but emphasizes innovation over straightforward memoirs.

New Voices Award

Prize: $2,000 and publication ($1,000 for the Honor Award winner)

Deadline: 8/31/18

Sponsor: Lee and Low Books

Description: Seeks a children’s picture book manuscript by a writer of color or a Native/Indigenous writer. Only U.S. residents who have not previously published a children’s picture book are eligible. Fiction, nonfiction, and poetry accepted that addresses the needs of children of color and Native nations by providing stories with which they can identify and which promote a greater understanding of one another. Work should be under 1,500 words.

St. Martin’s Minotaur / Mystery Writers of America First Crime Novel Competition

Prize: Publication and a $10,000 advance

Deadline: 1/11/19

Sponsor: Mystery Writers of America

Description: Seeks mysteries by writers who have never published a novel (not including self-publishing). Serious crime must be at the heart of the work.

Stowe Prize

Prize: $10,000

Deadline: 5/29/19

Sponsor: Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

Description: Named for the abolitionist and author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, recognizes a U.S. author whose work has made a tangible impact on a social justice issue critical to contemporary society. Can be for a single work or a body of work (fiction or nonfiction) within two years of submission.

ServiceScape Short Story Award

Prize: $1,000

Deadline: 11/29/19

Sponsor: ServiceScape

Description: Accepts original, unpublished work (5,000 words or fewer) in any genre.

The Marfield Prize

Prize: $10,000

Deadline: 10/15/19

Sponsor: The Arts Club of Washington

Description: This award celebrates nonfiction books about an artistic discipline published the previous year.

The Glenna Luschei Prize for African Poetry

Prize: $1,000

Deadline: TBD

Sponsor: African Poetry Book Fund

Description: This annual prize honors published books by African poets.

The Roswell Award

Prize: $500

Deadline: 1/28/19

Sponsor: Light Bringer Project and Sci-Fest L.A.

Description: Explore the future of humankind with science fiction short stories between 1,500 and 500 words by authors over 18. Also includes prizes for translated work and feminist work.

2018 Inkshares Mystery & Thriller Contest

Prize: Publication

Deadline: 12/14/18

Sponsor: Inkshares

Description: Seeking unpublished mystery and thriller novels.

Narrative Prize

Prize: $4,000

Deadline: 6/15/19

Sponsor: Narrative

Description: The $4,000 Narrative Prize is awarded annually for the best short story, novel excerpt, poem, one-act play, graphic story, or work of literary nonfiction published by a new or emerging writer in Narrative.

What’s your favorite writing contest—and why? Tell me in the comments.

Need help writing your novel? Click here to download my ultimate 12-step guide.

Related Posts:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

How to Publish a Book: My Ultimate Guide from 40+ Years of Experience

How to Overcome Writer’s Block Once and for All: My Surprising Solution

The post Your Ultimate Guide to Writing Contests Through 2019 appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

November 27, 2018

How to Format Your Manuscript (Even If You Hate Computers)

Before an Acquisitions Editor or an Agent reads a word of your manuscript, they can tell if it’s properly formatted.

That’s crucial. Why?

It’s about more than looks. Sure, they’re going to decide on buying your work largely on the writing and market potential.

So why is formatting so important?

Any errors will have to be fixed before printing — which adds costs on their end.

Poor formatting indicates that either you didn’t read their submission guidelines or can’t follow directions.

Proper formatting doesn’t guarantee publication, nor does poor formatting guarantee rejection. But you’ve worked hard on your manuscript. You want to give it the best chance to become a book.

This guide offers you:

Formatting guidelines to ensure your manuscript looks professional

Simple instructions to formatting in Microsoft Word.

An example from my own writing

Getting Started: What is a Manuscript?

A manuscript is your work of fiction or nonfiction that you submit to a publisher or agent in the hope that someone will turn it into a published book.

What is Formatting?

Formatting is how your manuscript looks. This includes things like whether the lines are single- or double-spaced. What size font? What typeface? How are numbers rendered — as digits or written out?

Manuscript Formatting Guidelines

Each agent and publisher may have slightly different submission guidelines — some specifying that they prefer The Chicago Manual of Style or the AP (Associated Press) Style, and some offering style specifics of their own.

If you’re submitting to one who specifies, naturally you want to give them what they want.

But some don’t give instructions beyond “standard manuscript format.” Then your best bet is to make your own choices, but be sure you’re consistent.

For instance, if you write out numbers between zero and nine and use digits for any after that, do it the same way every time. If they wanted to change them, they can do it easily.

As for how to layout your manuscript pages and determine their look, following certain general rules will make your manuscript look professional. For more detail, refer to the “Implementing Formatting” section.

Use 12-point type

Use a serif font; the most common choice is Times Roman

Double space your manuscript

No extra space between paragraphs

Only one space between sentences

Indent each paragraph half an inch (setting a tab, not using several spaces)

Text should be flush left and ragged right, not justified

If you choose to add a line between paragraphs to indicate a change of location or passage of time, center a typographical dingbat (like ***) on the line

Black text on a white background only

One-inch margins (the default in Word)

Create a header with the title followed by your last name and the page number. The header should appear on each page after the title page.

Additionally, agents and publishers want your name, email, address, and phone number in the top left and word count to the nearest hundred in the top right of your title page. Your title should be about a third of the the page from the top and centered. It should be the same size and font as the rest of the text. Don’t make it bold, italic, or larger.

Implementing the Format

Here’s more detail on each of these rules to help you understand how to format your manuscript in Microsoft Word.

Use 12-Point Type:

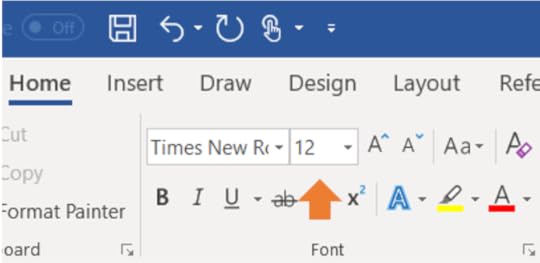

Twelve-point is the size of the text (letters an inch high would be 72-point type). Make sure your formatting is set to 12 by clicking this button in Word.

To format your document all at once, press and hold Ctrl and press A to select the whole document, then use the font change box to change all the text. You can apply this same procedure to any editorial change you wish to make in an entire file at a time.

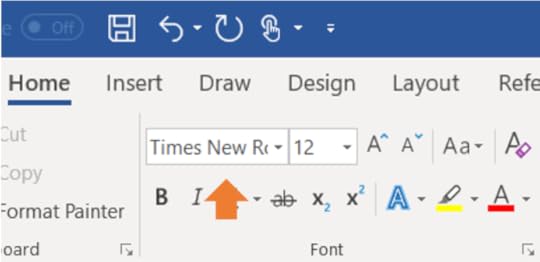

Use a Serif Font:

Fonts are the various designs of typefaces. Serifs are those small projects that finish off a letter, as in Times Roman type. Choose Times New Roman, and you can’t go wrong. Here’s how to change your font, if necessary, using the same procedure we used to change the type size:

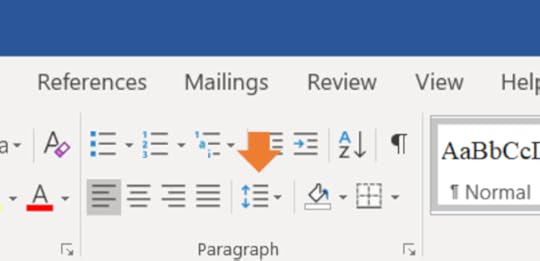

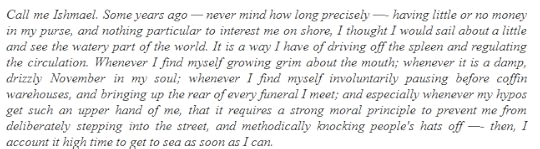

Double Space Your Manuscript:

This means your manuscript will a space between lines, like this:

This is an example of double spacing, as opposed to the single spacing of the rest of this blog post. You do not want to accomplish this by hitting Enter at the end of each line. That will result in such garbled formatting that it’s an almost automatic rejection. Set your word processor to double space using this button:

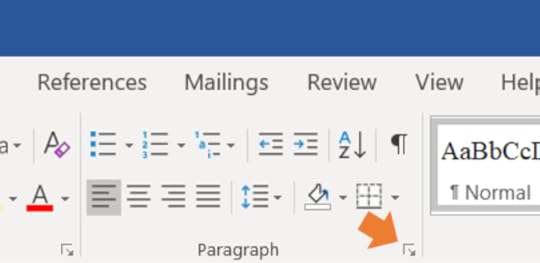

No Extra Space Between Paragraphs:

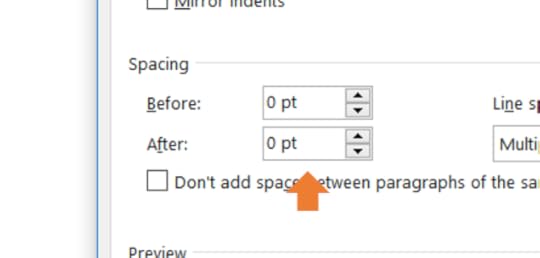

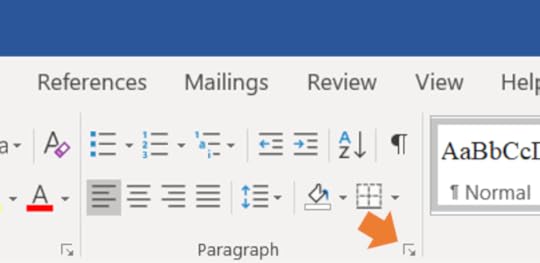

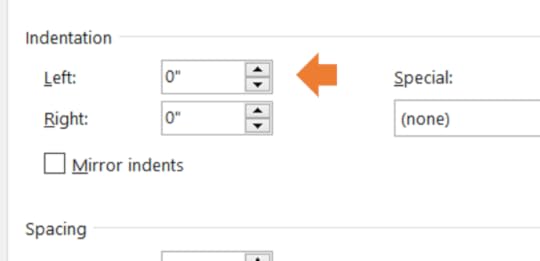

Notice the extra space between the paragraphs of this blog post? Manuscripts shouldn’t have those because published books customarily don’t. (And if they do, it’s an indication the book was self-published.). Unfortunately, Word is often defaulted to adding .8 points extra between paragraphs, so you’ll want to change that this way (and make it your default):

Only One Space Between Sentences:

Those of us who learned to type on typewriters were taught to hit the space bar twice between sentences, and it’s a hard habit to break. But you never see more than one space between sentences in published books.

So if you’ve already written your manuscript with two spaces between sentences, don’t despair. There’s a shortcut to fixing this in Microsoft Word.

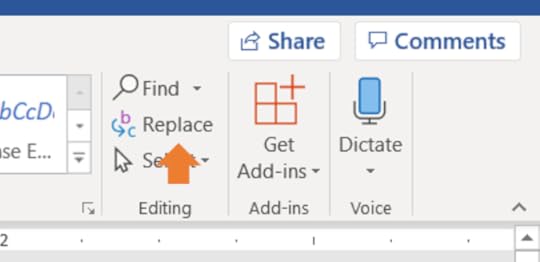

First, click Replace.

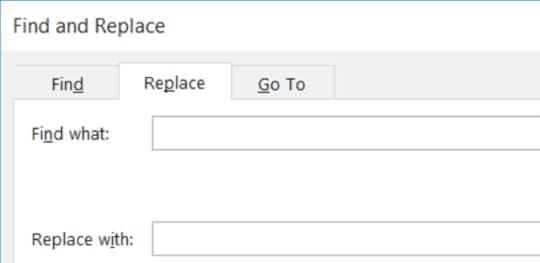

You should see a box labeled “Find and Replace.” In the first box, type two spaces. In the second box type one space. This tells the word processor, “Wherever you see two spaces together, change that to one space.”

Finally, click “Replace All.”

Indent Each Paragraph Half an Inch:

Choose this option in the menu shown here, not by hitting the space bar several times at the beginning of each paragraph. This way your new paragraphs are automatically indented when you hit Enter at the end of the previous one.

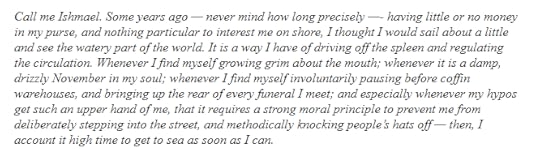

Text Should Ragged Right, not Justified:

Ragged Right means your text doesn’t line up perfectly against the right side of the page the way it does on the left. In a published book, text is often Justified, but that’s after editing and proofreading and final formatting. For your manuscript, any copy that you don’t want centered (like chapter titles) should be Flush Left and Ragged Right.

Your text should look like this:

Not like this:

Notice that the second paragraph adds space between the words to make the lines all the same length. Click here to make your text ragged right.

One Inch Margins:

Your margins are the white space at the tops and bottoms and sides of the page where there is no text. They should be one inch by default.

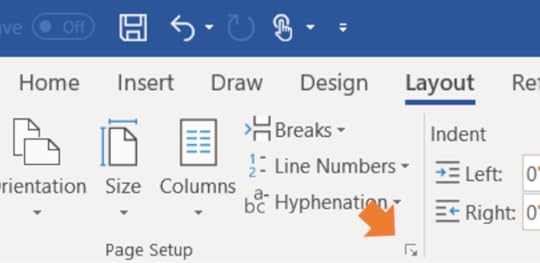

If you need to adjust them in Microsoft Word, simply click on Layout, then Margins, and choose the first option, Normal.

Creating a Header:

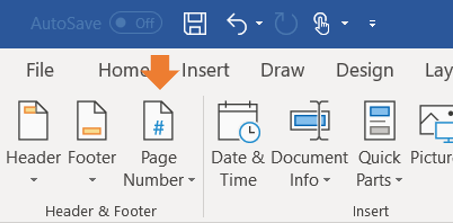

A header is text that appears above each page before the first line. For your manuscript it should show your last name at the left, the book title centered, and the page number to the right.

Do not include a header on the title page.

To create a header in Microsoft Word, move your cursor into the margin above the top line and click twice. A new tab should appear at the top that reads “Header and Footer Tools.” Within that, click the button labeled “Page Number.” You’ll see a drop-down menu that allows you to place the page number on the right.

To keep your header from appearing on the first page, press “Different First Page” under the “Header and Footer Tools” tab.

Example from My Own Writing

Here’s the title page of the manuscript of my new novel, Dead Sea Rising, that I submitted to my publisher. Yours should look something like this:

Don’t Fret

Too many writers worry more about formatting that they do the writing of their nonfiction book or novel manuscript.

If all the above tips read like Greek to you, get a young person to walk you through them. And if all else fails, follow as many of the basics as you can. The crucial ones are san serif typeface and 12 pt. size, Ragged Right, double spaced lines, one space between sentences, and indented paragraphs.

Most important to an Agent or an Acquisitions Editor is whether you have something to say, can write it engagingly, and tell a story (fiction or nonfiction).

Similar Posts:

How to Overcome Writer’s Block Once and For All: My Surprising Solution

How to Become a Better Writer: 15 Simple Ways to Hone Your Writing Skills

Book Writing Software to Help You Create, Organize, and Edit Your Manuscript

The post How to Format Your Manuscript (Even If You Hate Computers) appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

November 13, 2018

How to Improve Your Writing Skills: 15 Simple Tips

Would you believe that even after writing and publishing nearly 200 books, including 21 New York Times bestsellers, I still take daily steps to hone my writing skills?

Whether you’re a beginner or have been at it for decades as I have, writing well takes work.

No shortcut, no secret sauce will turn you into a bestselling author overnight.

But there are steps to take if you want to become a better writer.

Need help writing your book? Click here to download my ultimate 20-step guide.

Focus on These 15 Tips to Become a Better Writer

1 – Write what inspires you.

Sports became my passion as a kid.

I ate, drank and slept baseball until an injury took me out of the game and I started sportswriting.

I remain passionate about sports, so more than 20 of my titles are as-told-to autobiographies of famous athletes.

When I felt called into full-time Christian work, I thought I’d have to give up writing and become a pastor or missionary. I was thrilled to discover I could use my writing to follow that call.

What drives you?

What’s your passion? Your strength?

Write about that.

Your passion will carry you when the writing becomes difficult — and if you’re doing it right, it always does.

2 – Establish a writing routine and stick to it.

Treat your writing schedule like it’s your job.

Show up and work.

There’ll always be something to do: writing, editing, researching… You’ll be astonished at what you can get done when you plant yourself in your chair for a specific period every day.

And let people know that aside from an emergency, you’re not available for that block of time.

Respect your writing time and others will too.

3 – Become an avid reader.

Writers are readers. Good writers are good readers. Great writers are great readers.

Want to write in a favorite genre? Read at least 200 titles in it first.

Read everything you can. You’ll soon learn what works and what doesn’t.

4 – Start small.

Take time to build your craft and hone your skills on smaller projects before you try to write a book.

Journal. Write a newsletter. Start a blog. Write short stories. Submit articles to magazines, newspapers, or e-zines.

Take a night school or online course in journalism or creative writing.

Attend a writers conference.

5 – Write, write, write.

Dreamers talk about writing. Writers write.

Keep writing even when you don’t feel like it.

Write every day. And don’t expect to be good at it at first. You were bad at walking until you learned to walk, bad at riding a bike until you learned how, bad at baking until you mastered it. Allow yourself room to grow.

6 – See yourself as a writer.

If you’ve read this far, I assume you’d like to become a better writer.

Don’t let imposter syndrome* crush your dream before you even give yourself a chance. [*Feeling as if you’re pretending because you don’t feel like a real writer.]

Do you have a message to share with the world?

Don’t listen to those who tell you you’ll never be good enough — even if they’re just voices in your head. You’ll guarantee failure if you don’t muster the courage to try.

If you’re writing, regardless how well or how successful, call yourself a writer and stay at it.

7 – Become a ferocious self-editor.

Agents and editors can tell within the first two pages whether a manuscript is worthy of further consideration.

That sounds unfair, and maybe it is. But it’s a reality we writers need to face.

Learn to aggressively self-edit, and never submit writing you’re not entirely happy with. Learn to:

Show, don’t tell

Avoid throat-clearing

Resist the urge to explain

Avoid clichés

Avoid telling what’s not happening

Click this link for my complete 21-step self-editing checklist where I explain each principle. Apply these to your writing and see if it doesn’t make you a better writer.

8 – Join a writers critique group.

One fast way to get better at writing is through valuable input from other writers.

Find a writer’s critique group or mentor who’ll be brutally honest with you.

Be prepared to take an ego-bruising at first. But I promise you’ll become a better writer if you’re held accountable, not allowed to quit, and encouraged that you’re not alone on this journey.

One caveat: Be sure at least one person, preferably the leader, is experienced and understands the writing business. A group of only beginners risks the blind leading the blind.

Need help writing your book? Click here to download my ultimate 20-step guide.

9 – Master the craft.

Every writer needs to regularly brush up on the basics.

I’ve read The Elements of Style at least once a year for more than 40 years. This short easy read covers everything from style and grammar to usage.

Make it a major tool in your writing arsenal.

10 – Grab your reader from the get-go.

The opener to any piece of writing is the most important work you’ll do. Lose your reader here, and you’ve lost him for good.

Your goal with every word is to make your reader want to read the next and the next. Hook him and don’t let him go.

That doesn’t mean violence or chase scenes — unless you’re writing a thriller. It means avoiding too much scene setting and description and getting to the good stuff — the guts of the story — as soon as possible.

11 – Search and destroy passive voice.

I could tell you about subjects and objects and verbs and which is acting vs. being acted upon, avoiding adverbs, and all that. But unless you excelled at grammar and diagramming sentences, that’s going to sound like gibberish.

The easiest way to spot passive voice is to look for state-of-being verbs and often the word by.

Passive: The party was planned by Jill.

Active: Jill planned the party.

Passive: The wedding cake was created by Ben.

Active: Ben created the wedding cake.

Avoiding passive voice will set you apart from much of your competition and add power to your writing.

12 – Use powerful verbs. Avoid adverbs.

Ever wonder why an otherwise grammatically correct sentence lies there like a dead fish?

Your sentence might be full of those adjectives and adverbs your teachers and loved ones so admired in your writing when you were a kid. But the sentence doesn’t work.

Something I learned from The Elements of Style years ago changed the way I write and added verve to my prose: “Focus on nouns and verbs, not adjectives and adverbs.”

To learn how, read my post 249 Strong Verbs That’ll Instantly Supercharge Your Writing.

13 – Always think reader-first.

This is so fundamentally important that you should write it on a sticky note and put it on your monitor so you’re reminded of it every time you write.

Every writing decision should be run through this filter. Not you-first, not book-first, not editor-first, agent-first, or publisher-first. Certainly not your inner-circle-of critics-first.

Treat readers like you want to be treated and write what you would read. Never let up, never bore.

14 – See Writer’s Block for the myth it is..

“Wait, what?” you say. “I know it’s real, I’m suffering from it right now!”

Believe me, I know what you’re going through. I’m not saying I don’t have those days when I roll out of bed feeling I’d rather do anything but put words on the page.

The difference is, I know how to get unstuck, and you can too.

What we call Writer’s Block is really just a cover for much deeper issues:

Fear

Laziness

Perfectionism

If Writer’s Block were real, why would it affect only writers? Imagine calling your boss and saying, “I can’t come in today. I have worker’s block.”

You’d be laughed off the phone! And you’d likely be told never to come in again.

No other profession accommodates this malady, so we writers shouldn’t either.

Stand up to Writer’s Block like you would stand up to a bully. Allow your fear to humble you, and that humility to motivate you to do your best work. That’s what leads to success.

15 – Listen to the experts.

There’s no greater inspiration than learning the good and the bad from experts willing to share from their wealth of experience.

I asked 39 of the best authors, writing coaches, and publishing experts I know:

“If you could go back to the beginning of your writing career and give yourself one piece of advice, what would it be?”

Here are some of their answers:

Joe Bunting, founder of The Write Practice:

Always be learning.

You think you’re pretty talented. You think you’re pretty smart. And you are. But the best way to fail at being a writer is to spend all your time proving you know what you’re doing rather than learning from the people and resources around you.

Stop posturing. Start practicing. And have fun.

K.M. Weiland, novelist and writing coach:

I would want my younger self to realize that as wonderful as publication is, it isn’t the point of the writing process.

It’s just a stop along the road. Writing is more about the journey than the destination. As award-winning author Anne Lamott points out, “Being published isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Writing is.” So don’t let your non-published status get you down. Just enjoy where you are right now.

Joanna Penn, novelist and writing coach:

Schedule time to write, show up for that meeting with yourself, and put words onto the page.

It doesn’t matter if those words aren’t very good — they probably won’t be, but that’s OK because you can make them better when you edit them later.

But you can’t edit a blank page, so get your butt into the chair and write!

James Scott Bell, novelist and writing coach:

Don’t be so impatient!

It takes time to develop your craft.

You spent your 20s believing what so many told you, that you can’t learn to write. But then you tried, and you discovered you CAN learn.

Keep learning. Keep writing.

Click here to read each of the 39 answers.

Put in the Time, and You Can Get Better at Writing

I’ve made it my life’s work to coach writers because I’d love to see you enjoy the benefits I’ve enjoyed.

These 15 steps aren’t overnight fixes. The process can be long and messy, but don’t quit. Commit to putting words on the page every day, and remain a lifelong learner. Then share your progress with me.

Need help writing your book? Click here to download my ultimate 20-step guide.

Related Posts:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

How to Publish a Book: My Ultimate Guide from 40+ Years of Experience

How to Write a Novel: A 12-Step Guide

The post How to Improve Your Writing Skills: 15 Simple Tips appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

How to Become a Better Writer: 15 Simple Ways to Hone Your Writing Skills

Would you believe that even after writing and publishing nearly 200 books, including 21 New York Times bestsellers, I still take daily steps to hone my writing skills?

Whether you’re a beginner or have been at it for decades as I have, writing well takes work.

No shortcut, no secret sauce will turn you into a bestselling author overnight.

But there are steps to take if you want to become a better writer.

Focus on These 15 Tips to Become a Better Writer

1 – Write what inspires you.

Sports became my passion as a kid.

I ate, drank and slept baseball until an injury took me out of the game and I started sportswriting.

I remain passionate about sports, so more than 20 of my titles are as-told-to autobiographies of famous athletes.

When I felt called into full-time Christian work, I thought I’d have to give up writing and become a pastor or missionary. I was thrilled to discover I could use my writing to follow that call.

What drives you?

What’s your passion? Your strength?

Write about that.

Your passion will carry you when the writing becomes difficult — and if you’re doing it right, it always does.

2 – Establish a writing routine and stick to it.

Treat your writing schedule like it’s your job.

Show up and work.

There’ll always be something to do: writing, editing, researching… You’ll be astonished at what you can get done when you plant yourself in your chair for a specific period every day.

And let people know that aside from an emergency, you’re not available for that block of time.

Respect your writing time and others will too.

3 – Become an avid reader.

Writers are readers. Good writers are good readers. Great writers are great readers.

Want to write in a favorite genre? Read at least 200 titles in it first.

Read everything you can. You’ll soon learn what works and what doesn’t.

4 – Start small.

Take time to build your craft and hone your skills on smaller projects before you try to write a book.

Journal. Write a newsletter. Start a blog. Write short stories. Submit articles to magazines, newspapers, or e-zines.

Take a night school or online course in journalism or creative writing.

Attend a writers conference.

5 – Write, write, write.

Dreamers talk about writing. Writers write.

Keep writing even when you don’t feel like it.

Write every day. And don’t expect to be good at it at first. You were bad at walking until you learned to walk, bad at riding a bike until you learned how, bad at baking until you mastered it. Allow yourself room to grow.

6 – See yourself as a writer.

If you’ve read this far, I assume you’d like to become a better writer.

Don’t let imposter syndrome* crush your dream before you even give yourself a chance. [*Feeling as if you’re pretending because you don’t feel like a real writer.]

Do you have a message to share with the world?

Don’t listen to those who tell you you’ll never be good enough — even if they’re just voices in your head. You’ll guarantee failure if you don’t muster the courage to try.

If you’re writing, regardless how well or how successful, call yourself a writer and stay at it.

7 – Become a ferocious self-editor.

Agents and editors can tell within the first two pages whether a manuscript is worthy of further consideration.

That sounds unfair, and maybe it is. But it’s a reality we writers need to face.

Learn to aggressively self-edit, and never submit writing you’re not entirely happy with. Learn to:

Show, don’t tell

Avoid throat-clearing

Resist the urge to explain

Avoid clichés

Avoid telling what’s not happening

Click this link for my complete 21-step self-editing checklist where I explain each principle. Apply these to your writing and see if it doesn’t make you a better writer.

8 – Join a writers critique group.

One fast way to get better at writing is through valuable input from other writers.

Find a writer’s critique group or mentor who’ll be brutally honest with you.

Be prepared to take an ego-bruising at first. But I promise you’ll become a better writer if you’re held accountable, not allowed to quit, and encouraged that you’re not alone on this journey.

One caveat: Be sure at least one person, preferably the leader, is experienced and understands the writing business. A group of only beginners risks the blind leading the blind.

9 – Master the craft.

Every writer needs to regularly brush up on the basics.

I’ve read The Elements of Style at least once a year for more than 40 years. This short easy read covers everything from style and grammar to usage.

Make it a major tool in your writing arsenal.

10 – Grab your reader from the get-go.

The opener to any piece of writing is the most important work you’ll do. Lose your reader here, and you’ve lost him for good.

Your goal with every word is to make your reader want to read the next and the next. Hook him and don’t let him go.

That doesn’t mean violence or chase scenes — unless you’re writing a thriller. It means avoiding too much scene setting and description and getting to the good stuff — the guts of the story — as soon as possible.

11 – Search and destroy passive voice.

I could tell you about subjects and objects and verbs and which is acting vs. being acted upon, avoiding adverbs, and all that. But unless you excelled at grammar and diagramming sentences, that’s going to sound like gibberish.

The easiest way to spot passive voice is to look for state-of-being verbs and often the word by.

Passive: The party was planned by Jill.

Active: Jill planned the party.

Passive: The wedding cake was created by Ben.

Active: Ben created the wedding cake.

Avoiding passive voice will set you apart from much of your competition and add power to your writing.

12 – Use powerful verbs. Avoid adverbs.

Ever wonder why an otherwise grammatically correct sentence lies there like a dead fish?

Your sentence might be full of those adjectives and adverbs your teachers and loved ones so admired in your writing when you were a kid. But the sentence doesn’t work.

Something I learned from The Elements of Style years ago changed the way I write and added verve to my prose: “Focus on nouns and verbs, not adjectives and adverbs.”

To learn how, read my post 249 Strong Verbs That’ll Instantly Supercharge Your Writing.

13 – Always think reader-first.

This is so fundamentally important that you should write it on a sticky note and put it on your monitor so you’re reminded of it every time you write.

Every writing decision should be run through this filter. Not you-first, not book-first, not editor-first, agent-first, or publisher-first. Certainly not your inner-circle-of critics-first.

Treat readers like you want to be treated and write what you would read. Never let up, never bore.

14 – See Writer’s Block for the myth it is..

“Wait, what?” you say. “I know it’s real, I’m suffering from it right now!”

Believe me, I know what you’re going through. I’m not saying I don’t have those days when I roll out of bed feeling I’d rather do anything but put words on the page.

The difference is, I know how to get unstuck, and you can too.

What we call Writer’s Block is really just a cover for much deeper issues:

Fear

Laziness

Perfectionism

If Writer’s Block were real, why would it affect only writers? Imagine calling your boss and saying, “I can’t come in today. I have worker’s block.”

You’d be laughed off the phone! And you’d likely be told never to come in again.

No other profession accommodates this malady, so we writers shouldn’t either.

Stand up to Writer’s Block like you would stand up to a bully. Allow your fear to humble you, and that humility to motivate you to do your best work. That’s what leads to success.

15 – Listen to the experts.

There’s no greater inspiration than learning the good and the bad from experts willing to share from their wealth of experience.

I asked 39 of the best authors, writing coaches, and publishing experts I know:

“If you could go back to the beginning of your writing career and give yourself one piece of advice, what would it be?”

Here are some of their answers:

Joe Bunting, founder of The Write Practice:

Always be learning.

You think you’re pretty talented. You think you’re pretty smart. And you are. But the best way to fail at being a writer is to spend all your time proving you know what you’re doing rather than learning from the people and resources around you.

Stop posturing. Start practicing. And have fun.

K.M. Weiland, novelist and writing coach:

I would want my younger self to realize that as wonderful as publication is, it isn’t the point of the writing process.

It’s just a stop along the road. Writing is more about the journey than the destination. As award-winning author Anne Lamott points out, “Being published isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Writing is.” So don’t let your non-published status get you down. Just enjoy where you are right now.

Joanna Penn, novelist and writing coach:

Schedule time to write, show up for that meeting with yourself, and put words onto the page.

It doesn’t matter if those words aren’t very good — they probably won’t be, but that’s OK because you can make them better when you edit them later.

But you can’t edit a blank page, so get your butt into the chair and write!

James Scott Bell, novelist and writing coach:

Don’t be so impatient!

It takes time to develop your craft.

You spent your 20s believing what so many told you, that you can’t learn to write. But then you tried, and you discovered you CAN learn.

Keep learning. Keep writing.

Click here to read each of the 39 answers.

Put in the Time, and You Can Get Better at Writing

I’ve made it my life’s work to coach writers because I’d love to see you enjoy the benefits I’ve enjoyed.

These 15 steps aren’t overnight fixes. The process can be long and messy, but don’t quit. Commit to putting words on the page every day, and remain a lifelong learner. Then share your progress with me.

Related Posts:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

How to Publish a Book: My Ultimate Guide from 40+ Years of Experience

How to Write a Novel: A 12-Step Guide

The post How to Become a Better Writer: 15 Simple Ways to Hone Your Writing Skills appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

October 16, 2018

Writing Groups: How To Find the Right One

When we writers spend hours alone at the keyboard, that isolation can get to even us introverts.

The solution is to find a writers group—populated by like-minded fellow strugglers.

I belong to three—one that meets in person and two that interact online, and I encourage Jerry Jenkins Writers Guild members to find one or form their own.

If you’re serious about your writing dreams, a writers group can help you fulfill them.

Why?

Writers understand each other.

You can look to family and friends for support, but unless they’re writers, they’re not likely to really comprehend what you’re going through.

You want someone who’s been where you are.

Whatever your challenge, someone in your writers group has experienced the same and gained insight they’re happy to share.

Late motivational speaker Jim Rohn said we are the average of the five people we spend the most time with.

That’s why I enjoy spending time with writers.

Before Joining a Writers Group

Know what you hope to gain from it.

A writers group should help you become a better craftsperson, not serve only as a cheerleading squad for you. And neither should it be the opposite—a gaggle of critics that leaves you feeling low after every meeting.

Rather, seek (or form) a group that includes at least one member who has succeeded in the business. Ideally, the leader should be someone who has published two or more books, has an agent, and knows how to work with editors at publishing houses.

Most important, be sure the leader allows both praise and constructive criticism. Otherwise you could wind up in a writers group where everyone praises everyone else’s work, yet no one gets published. Or one in which everyone criticizes each other’s writing but no one learns how to improve.

Guidelines for Joining a Writers Group

Choose as specific a writers group as possible. Some have writers of all sorts who write in a variety of genres—fiction, nonfiction, children’s, sci-fi, fantasy, memoir, you name it.

That isn’t all bad, but such assemblages tend to discuss what applies to all—the business side of things, like agents, contracts, promotion. If you’re looking to specifically improve your writing, look for a writers group made up of others in your genre.

How to Find a Writers Group

Finding an online writers group is as easy as publicizing your interest. Google or announce in social media your desire to interact with other writers in your genre.

In-person groups offer more dynamic interaction, but you may find online groups easier to form by genre.

For in-person writers groups, check:

Your library

Your community center

Meetup.com

Word Weavers International (designed for Christian writers)

For online writers groups, check:

Facebook (search “writers group” and remember—the more specific, the better)

Critters

The Jerry Jenkins Writers Guild

Scribophile

If you can’t find a writers group that seems the right fit, consider starting one. Word Weavers offers a great model.

Even if you don’t live near other writers (don’t assume that till you’ve sought others in your area online), you could meet using video conferencing tools like Zoom and sharing manuscripts through email or via collaboration tools like Google Docs.

The #1 thing to remember when searching for a writers group:

You’re not alone. And you have plenty of options to find out who’s out there with you and for you.

The right writers group can help improve your craft, motivate you, and give you confidence. Finding one is worth the search.

Are you already in a writers group you love? Tell me about it in the comments.

Related Posts:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

How to Write a Novel: A 12-Step Guide

How to Overcome Writer’s Block Once and For All: My Surprising Solution

The post Writing Groups: How To Find the Right One appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.