Jerry B. Jenkins's Blog, page 17

July 19, 2017

How to Write Your Memoir: A 4-Step Guide

Memoir is not just a fancy literary term for an autobiography. I say that from the start, because I hear the terms used interchangeably so often.

Your memoir will be autobiographical, but it will not be your life story.

Confused yet? Stay with me.

Simply put, an autobiography is likely to cover one’s birth to the present — emphasis often on accomplishments, but the more honest and revelatory the better.

A memoir draws on selected anecdotes from your life to support a theme and make a point. For instance, if your point is how you came from some unlikely place to where you are now, you would choose scenes from your life to support that.

Maybe you came from:

The wrong side of the tracks

A broken home

Having been a victim of abuse

Addiction

An orphanage

To a position of:

Wealth

Status

Happiness

Health

Faith

You might start with memories that show how bad things once were for you. Then you would show pivotal experiences in your life, important people in your transformation, what you learned, and how you applied certain principles to see this vast change.

Naturally, the better the stories, the better the memoir. However, great stories are not the point — and frankly, neither is the memoirist (you).

What Publishers Look For

Don’t buy into the idea that only famous people can sell a memoir. Sure, if you’re a household name and people are curious about you, that’s an advantage.

But memoirs by nobodies succeed all the time — and for one reason: they resonate with readers because readers identify with truth. Truth, even hard, gritty, painful truth, bears transferrable principles.

Memoirs full of such relatable candor attract readers, and readers are what publishers want. An astute agent or acquisitions editor can predict how relatable a memoir will be and take a chance on one from an unpublished unknown.

Agents and editors tell me they love to discover such gems — the same way they love discovering the next great novelist.

So, when writing your memoir…

You may be the subject, but it’s not about you — it’s about what readers can gain from your story.

It may seem counterintuitive to think reader-first while writing in the first-person about yourself. But if your memoir doesn’t enrich, entertain, or enlighten readers, they won’t stay with it long, and they certainly won’t recommend it.

Want to save this guide to read, save, or print whenever you wish? Click here.

How to Write a Memoir in 4 Steps

1. Know Your Theme

And remember, it’s not that you’ve made something of yourself — even if you have. Sorry, but nobody cares except those who already love you.

Your understated theme must be, “You’re not alone. What happened to me can also happen to you.”

That’s what appeals to readers. Even if they do come away from your memoir impressed with you, it won’t be because you’re so special — even if you are. Whether they admit it or not, readers care most about their own lives.

Imagine a reader picking up your memoir and thinking, What’s in this for me? The more of that you offer, the more successful your book will be. Think transferable principles in a story well told.

Cosmic Commonalities

All people, regardless of age, ethnicity, location, and social status, share certain felt needs: food, shelter, and love. They fear abandonment, loneliness, and the loss of loved ones. Regardless your theme, if it touches on any of those wants and fears, readers will identify.

I can read the memoir of someone of my opposite gender, for whom English is not her first language, of a different race and religion, who lives halfway around the world from me — and if she tells the story of her love for her child or grandchild, it reaches my core.

Knowing or understanding or relating to nothing else about her, I understand love of family.

Worried About Uniqueness?

Many writers tell me they fear their theme has been covered many times by many other memoirists. While it’s true, as the Bible says, that there’s nothing new under the sun, no one has written your story, your memoir, your way.

While I still say it’s not about you but really about your reader, it’s you who lends uniqueness to your theme. Write on!

How to Write a Memoir Without Preaching

Trust your narrative to do the work of conveying your message. Too many amateurish memoirists feel the need to eventually turn the spotlight on the reader with a sort of “So, how about you…?”

Let your experiences and how they impacted you make their own points, and trust the reader to get it. Beat him over the head with your theme and you run him off.

You can avoid being preachy by using what I call the Come Alongside Method. When you show what happened to you, if the principles apply to your reader he doesn’t need that pointed out. Give him credit.

2. Carefully Select Your Anecdotes

The best memoirs let readers see themselves in your story so they can identify with your experiences and apply to their own lives the lessons you’ve learned.

If you’re afraid to mine your pain deeply enough tell the whole truth, you may not be ready to write your memoir. There’s little less helpful — or marketable — than a memoir that glosses over the truth.

So feature anecdotes from your life that support your theme, regardless how painful it is to resurrect the memories. The more introspective and vulnerable you are, the more effective will be your memoir.

3. Write It Like a Novel

It’s as important in a memoir as it is in a novel to show and not just tell.

Example:

Telling

My father was a drunk who abused my mother and me. I was scared to death every time I heard him come in late at night.

Showing

As soon as I heard the gravel crunch beneath the tires and the car door open and shut, I dove under my bed. I could tell by his footsteps whether Dad was sober and tired or loaded and looking for a fight. I prayed God would magically make me big enough to jump between him and my mom, because she was always his first target…

Use every trick in the novelist’s arsenal to make each anecdote come to life: dialogue, description, conflict, tension, pacing, everything.

Worry less about chronology than theme. You’re not married to the autobiographer’s progressive timeline. Tell whatever anecdote fits your point for each chapter, regardless where they fall on the calendar. Just make the details clear so the reader knows where you are in the story.

You might begin with the most significant memory of your life, even from childhood. Then you can segue into something like, “Only now do I understand what was really happening.” Your current-day voice can always drop in to tie things together.

Character Arc

As in a novel, how the protagonist (in this case, you) grows is critical to a successful story. Your memoir should make clear the difference between who you are today and who you once were. What you learn along the way becomes your character arc.

Point of View

It should go without saying that you write a memoir in the first-person. And just as in a novel, the point-of-view character is the one with the problem, the challenge, something he’s after. Tell both your outer (what happens) and your inner (its impact on you) story.

Structure

In his classic How to Write Bestselling Fiction, novelist Dean Koontz outlines what he calls the Classic Story Structure. Though intended as a framework for a novel, it strikes me that this would be perfect for a memoir too — provided you don’t change true events just to make it work.

For fiction, Koontz recommends writers:

1 — Plunge your main character into terrible trouble as soon as possible

2 — Everything he does to try to get out of it makes it only progressively worse until…

3 — His situation appears hopeless

4 — But in the end, because of what he’s learned and how he’s grown through all those setbacks, he rises to the challenge and wins the day.

You might be able to structure your memoir the same way merely by how you choose to tell the story. As I say, don’t force things, but the closer you can get to that structure, the more engaging your memoir will be.

For your purposes, Koontz’s Terrible Trouble would be the nadir of your life. (If nadir is a new word for you, it’s the opposite of zenith.) Take the reader with you to your lowest point, and show what you did to try to remedy things. If your experience happens to fit the rest of the structure, so much the better.

Setups and Payoffs

Great novels carry a book-length setup that demands a payoff in the end, plus chapter-length setups and payoffs, and sometimes even the same within scenes. The more of these the better.

The same is true for your memoir. Virtually anything that makes the reader stay with you to find out what happens is a setup that demands a payoff. Even something as seemingly innocuous as your saying that you hoped high school would deliver you from the torment of junior high makes the reader want to find out if that proved true.

Make ‘em Wait

Avoid using narrative summary to give away too much information too early. I’ve seen memoir manuscripts where the author tells in the first paragraph how they went from abject poverty to independent wealth in 20 years, “…and I want to tell you how that happened.”

To me, that just took the air out of the tension balloon, and many readers would agree and see no reason to read on. Better to set them up for a payoff and let them wait. Not so long that you lose them to frustration, but long enough to build tension.

4. Tell Your Story (Without Throwing People Under the Bus)

If you’re brave enough to expose your own weaknesses, foibles, embarrassments, and yes, failures to the world, what about those of your friends, enemies, loved ones, teachers, bosses, and co-workers?

If you tell the truth, are you allowed to throw them under the bus?

In some cases, yes.

But should you?

No.

Even if they gave you permission in writing, what’s the upside?

Usually a person painted in a negative light—even if the story is true—would not sign a release allowing you to expose them publicly.

But even if they did, would it be the right, ethical, kind thing to do?

All I can tell you is that I wouldn’t do it. And I wouldn’t want it done to me.

If the Golden Rule alone isn’t reason enough not to do it, the risk of being sued certainly ought to be.

So, What to Do?

On the one hand I’m telling you your memoir is worthless without the grit, and on the other I’m telling you not to expose the evildoers.

Stalemate? No.

Here’s the solution:

Changing names to protect the guilty is not enough. Too many people in your family and social orbit will know the person, making your writing legally actionable.

So change more than the name.

Change the location. Change the year. Change their gender. You could even change the offense.

If your own father verbally abused you so painfully when you were thirteen that you still suffer from the memory decades later, attribute it to a teacher and have it happen at an entirely different age.

Is that lying in a nonfiction book? Not if you include a disclaimer upfront that stipulates: “Some names and details have been changed to protect identities.”

So, no, don’t throw anyone under the bus. But don’t stop that bus!

Common Memoir Mistakes to Avoid

Making it too much like an autobiography (missing a theme)

Including minutiae

Bragging

Glossing over the truth

Preaching

Effecting the wrong tone : funny, sarcastic, condescending

How to Start Your Memoir

Your goal is to hook your reader, so begin in medias res—in the middle of things.

If you start slowly, you lose readers interest. Jump right into the story!

Memoir Examples

Thoroughly immerse yourself this genre before attempting to write in it. I read nearly 50 memoirs before I wrote mine (Writing for the Soul). Here’s a list to get you started:

All Over But the Shoutin’ by Rick Bragg (my favorite book ever)

Cultivate by Lara Casey

A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

Out of Africa by Karen Blixen

Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt

Still Woman Enough by Loretta Lynn

Born Standing Up by Steve Martin

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

This Boy’s Life by Tobias Wolff

Molina by Benjie Molina and Joan Ryan

Want to save this guide to read, save, or print whenever you wish? Click here.

Are you working on your memoir or planning to? Do you have any questions on how to write a memoir? Share with me in the comments below.

Related Posts:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

How to Overcome Writer’s Block Once and for All: My Surprising Solution

How to Make an Author Website in the Next Hour…And Why You Need To

The post How to Write Your Memoir: A 4-Step Guide appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

How to Write Your Memoir: A 3-Step Guide

Memoir is not just a fancy literary term for an autobiography. I say that from the start, because I hear the terms used interchangeably so often.

Memoir is not just a fancy literary term for an autobiography. I say that from the start, because I hear the terms used interchangeably so often.

Your memoir will be autobiographical, but it will not be your life story.

Confused yet? Stay with me.

Simply put, an autobiography is likely to cover one’s birth to the present — emphasis often on accomplishments, but the more honest and revelatory the better.

A memoir draws on selected anecdotes from your life to support a theme and make a point. For instance, if your point is how you came from some unlikely place to where you are now, you would choose scenes from your life to support that.

Maybe you came from:

The wrong side of the tracks

A broken home

Having been a victim of abuse

Addiction

An orphanage

To a position of:

Wealth

Status

Happiness

Health

Faith

You might start with memories that show how bad things once were for you. Then you would show pivotal experiences in your life, important people in your transformation, what you learned, and how you applied certain principles to see this vast change.

Naturally, the better the stories, the better the memoir. However, great stories are not the point — and frankly, neither is the memoirist (you).

What Publishers Look For

Don’t buy into the idea that only famous people can sell a memoir. Sure, if you’re a household name and people are curious about you, that’s an advantage.

But memoirs by nobodies succeed all the time — and for one reason: they resonate with readers because readers identify with truth. Truth, even hard, gritty, painful truth, bears transferrable principles.

Memoirs full of such relatable candor attract readers, and readers are what publishers want. An astute agent or acquisitions editor can predict how relatable a memoir will be and take a chance on one from an unpublished unknown.

Agents and editors tell me they love to discover such gems — the same way they love discovering the next great novelist.

So, when writing your memoir…

You may be the subject, but it’s not about you — it’s about what readers can gain from your story.

It may seem counterintuitive to think reader-first while writing in the first-person about yourself. But if your memoir doesn’t enrich, entertain, or enlighten readers, they won’t stay with it long, and they certainly won’t recommend it.

3 Steps to Writing an Effective Memoir

1. Know Your Theme

And remember, it’s not that you’ve made something of yourself — even if you have. Sorry, but nobody cares except those who already love you.

Your understated theme must be, “You’re not alone. What happened to me can also happen to you.”

That’s what appeals to readers. Even if they do come away from your memoir impressed with you, it won’t be because you’re so special — even if you are. Whether they admit it or not, readers care most about their own lives.

Imagine a reader picking up your memoir and thinking, What’s in this for me? The more of that you offer, the more successful your book will be. Think transferable principles in a story well told.

Cosmic Commonalities

All people, regardless of age, ethnicity, location, and social status, share certain felt needs: food, shelter, and love. They fear abandonment, loneliness, and the loss of loved ones. Regardless your theme, if it touches on any of those wants and fears, readers will identify.

I can read the memoir of someone of my opposite gender, for whom English is not her first language, of a different race and religion, who lives halfway around the world from me — and if she tells the story of her love for her child or grandchild, it reaches my core.

Knowing or understanding or relating to nothing else about her, I understand love of family.

Worried About Uniqueness?

Many writers tell me they fear their theme has been covered many times by many other memoirists. While it’s true, as the Bible says, that there’s nothing new under the sun, no one has written your story, your memoir, your way.

While I still say it’s not about you but really about your reader, it’s you who lends uniqueness to your theme. Write on!

How to Avoid Preaching in Your Memoir

Trust your narrative to do the work of conveying your message. Too many amateurish memoirists feel the need to eventually turn the spotlight on the reader with a sort of “So, how about you…?”

Let your experiences and how they impacted you make their own points, and trust the reader to get it. Beat him over the head with your theme and you run him off.

You can avoid being preachy by using what I call the Come Alongside Method. When you show what happened to you, if the principles apply to your reader he doesn’t need that pointed out. Give him credit.

2. Carefully Select Your Anecdotes

The best memoirs let readers see themselves in your story so they can identify with your experiences and apply to their own lives the lessons you’ve learned.

If you’re afraid to mine your pain deeply enough tell the whole truth, you may not be ready to write your memoir. There’s little less helpful — or marketable — than a memoir that glosses over the truth.

So feature anecdotes from your life that support your theme, regardless how painful it is to resurrect the memories. The more introspective and vulnerable you are, the more effective will be your memoir.

Worried about throwing family members under the bus by telling the truth? That’s a legitimate concern. Click on the link above for suggestions.

3. Write It Like a Novel

It’s as important in a memoir as it is in a novel to show and not just tell.

Example:

Telling

My father was a drunk who abused my mother and me. I was scared to death every time I heard him come in late at night.

Showing

As soon as I heard the gravel crunch beneath the tires and the car door open and shut, I dove under my bed. I could tell by his footsteps whether Dad was sober and tired or loaded and looking for a fight. I prayed God would magically make me big enough to jump between him and my mom, because she was always his first target…

Use every trick in the novelist’s arsenal to make each anecdote come to life: dialogue, description, conflict, tension, pacing, everything.

Worry less about chronology than theme. You’re not married to the autobiographer’s progressive timeline. Tell whatever anecdote fits your point for each chapter, regardless where they fall on the calendar. Just make the details clear so the reader knows where you are in the story.

You might begin with the most significant memory of your life, even from childhood. Then you can segue into something like, “Only now do I understand what was really happening.” Your current-day voice can always drop in to tie things together.

Character Arc

As in a novel, how the protagonist (in this case, you) grows is critical to a successful story. Your memoir should make clear the difference between who you are today and who you once were. What you learn along the way becomes your character arc.

Point of View

It should go without saying that you write a memoir in the first-person. And just as in a novel, the point-of-view character is the one with the problem, the challenge, something he’s after. Tell both your outer (what happens) and your inner (its impact on you) story.

Structure

In his classic How to Write Bestselling Fiction, novelist Dean Koontz outlines what he calls the Classic Story Structure. Though intended as a framework for a novel, it strikes me that this would be perfect for a memoir too — provided you don’t change true events just to make it work.

For fiction, Koontz recommends writers:

1 — Plunge your main character into terrible trouble as soon as possible

2 — Everything he does to try to get out of it makes it only progressively worse until…

3 — His situation appears hopeless

4 — But in the end, because of what he’s learned and how he’s grown through all those setbacks, he rises to the challenge and wins the day.

You might be able to structure your memoir the same way merely by how you choose to tell the story. As I say, don’t force things, but the closer you can get to that structure, the more engaging your memoir will be.

For your purposes, Koontz’s Terrible Trouble would be the nadir of your life. (If nadir is a new word for you, it’s the opposite of zenith.) Take the reader with you to your lowest point, and show what you did to try to remedy things. If your experience happens to fit the rest of the structure, so much the better.

Setups and Payoffs

Great novels carry a book-length setup that demands a payoff in the end, plus chapter-length setups and payoffs, and sometimes even the same within scenes. The more of these the better.

The same is true for your memoir. Virtually anything that makes the reader stay with you to find out what happens is a setup that demands a payoff. Even something as seemingly innocuous as your saying that you hoped high school would deliver you from the torment of junior high makes the reader want to find out if that proved true.

Make ‘em Wait

Avoid using narrative summary to give away too much information too early. I’ve seen memoir manuscripts where the author tells in the first paragraph how they went from abject poverty to independent wealth in 20 years, “…and I want to tell you how that happened.”

To me, that just took the air out of the tension balloon, and many readers would agree and see no reason to read on. Better to set them up for a payoff and let them wait. Not so long that you lose them to frustration, but long enough to build tension.

Common Memoir Mistakes to Avoid

Making it too much like an autobiography (missing a theme)

Including minutiae

Bragging

Glossing over the truth

Preaching

Effecting the wrong tone: funny, sarcastic, condescending

How to Start Your Memoir

Your goal is to hook your reader, so begin in medias res—in the middle of things.

If you start slowly, you lose readers interest. Jump right into the story!

Memoir Examples

Thoroughly immerse yourself this genre before attempting to write in it. I read nearly 50 memoirs before I wrote mine (Writing for the Soul). Here’s a list to get you started:

All Over But the Shoutin’ by Rick Bragg (my favorite book ever)

Cultivate by Lara Casey

A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

Out of Africa by Karen Blixen

Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt

Still Woman Enough by Loretta Lynn

Born Standing Up by Steve Martin

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

This Boy’s Life by Tobias Wolff

Molina by Benjie Molina and Joan Ryan

Are you working on your memoir or planning to? Share with me in the comments below.

The post How to Write Your Memoir: A 3-Step Guide appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

July 10, 2017

How to Create Dazzling Dialogue

Guest blog by Gabriela Pereira

Of all aspects of the writing craft, dialogue is by far my favorite. Maybe it’s because dialogue makes me feel like I’m in the scene with the characters or lets me see their dynamic personalities bounce off each other. Or maybe it’s just because I’m impatient and don’t like to weed through pages of boring description.

Whatever the reason, I always look forward to dialogue passages… except when the dialogue is bad. Because to paraphrase from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, when dialogue is bad it is horrid.

The good news is that there are a few easy ways to fix less-than-stellar dialogue. I call these the “Nine NO’s”—as opposed to the “Nine Nevers”—because while these are things that writers should try to avoid, they are not hard and fast rules. You should not have to commit verbal acrobatics in order to eliminate them from your writing completely.

Here are the Nine No’s of Dialogue:

1. Name-Calling

Name-calling is when characters call each other by name in dialogue. For example:

“So Bill, how’s everything going?” Jill asked.

“Not too bad, Jill,” Bill replied. “Thanks for asking.”

While this tactic might seem like a convenient way to establish who is saying what, it also sounds terrible and people don’t speak this way in real conversations. Name-calling smacks of distrust—as though the writer is afraid the reader won’t figure out who’s talking—but instead of solving the problem, name-calling only makes the dialogue sound clunky and stilted.

2. Fussy Tags

Tags are the “he said, she said” part of dialogue. In other words, if you want to establish which character is talking, tags are the way to do it. The problem arises when writers get a carried away with tags, using words like cajoled, reiterated, or guffawed. Have you ever heard someone “guffaw” a line of dialogue? Didn’t think so.

When in doubt, use “said” because it blends into the background and doesn’t draw attention to itself. tags like “asked” or “replied” are also okay in moderation. But for the love of all that is literary, do not use fancy tags at random, just for the sake of switching things up. Fussy tags steal attention away from the important part of the dialogue: what the characters are saying.

3. Talking-Head Syndrome

Sometimes writers go to the opposite extreme, crafting dialogue that bounces back and forth between characters like a pingpong ball. When this happens, the reader has no idea where the characters are, or they’re even talking in the first place.

I call this Talking-Head Syndrome and the solution is simple:

Add stage directions.

If dialogue is the part that’s spoken by the characters, then stage directions are the actions that accompany those lines. Imagine the scene you’re writing is part of a play and you are the director. You need to tell the characters when to clear their throats, sip their tea, or grab the gun from the mantelpiece and pull the trigger.

Stage directions are especially useful if you want to create subtext. When a character’s actions contradict what he’s saying, that gives the reader a window into what the character is thinking or feeling. Remember, actions can speak much louder than words.

4. On-the-Nose Dialogue

On-the-nose dialogue is when people say exactly what they mean. This, of course, never happens in real life. Take for example that scene in the movie Clueless where the protagonist, Cher, comes downstairs wearing a revealing dress. This is the exchange she has with her father:

“What’s that?”

“A dress, Daddy.” She giggles.

“Says who?”

“Calvin Klein.”

If we take the dialogue literally, it seems like the father is asking his daughter about the outfit she is wearing. The truth is, this conversation has very little to do with couture and everything to do with the father-daughter relationship.

When he asks “What’s that?” Cher’s father is really saying “What on earth do you think you’re wearing?” But the subtext doesn’t end there.

Cher’s response is as sweet as it is patronizing, and when her dad responds with “Says who?” he might as well be telling her to go upstairs and change her clothes. Instead, she volleys back with a roll of the eyes and the words: “Calvin Klein.”

Game. Set. Match.

The dialogue itself consists of nine words, but it says so much more. This scene would be far less interesting—and less funny—if the characters say what they actually mean.

5. Rambling Start

In real life dialogue, people usually build up toward the heart of the conversation. They ask each other how they’re doing or comment about the weather, because that’s the polite thing to do. It might take several minutes until one of the speakers gets to the real reason for the conversation.

You don’t have time for small talk on the page. If you waste words on a rambling start, you risk losing your readers before you get to the good stuff. Skip to where the dialogue gets interesting and start there. Wouldn’t you rather read a passage that starts with “Why the hell have you been sleeping with my husband?” than something like “Hey Sally, nice to see you”? Forget the lead-up and get to the juicy stuff.

6. Adverb Overload

Nouns and verbs are the “meat and potatoes” of vibrant language. Adverbs are a condiment: a little goes a long way. This is especially true with dialogue.

Adverb overload is often a sign that you are not choosing the right verbs. If a verb is pulling its weight, you shouldn’t have to qualify it with an adverb. “He said softly” becomes much more specific when you say “He said, his breath tickling her ear” or “He said, his voice like syrup.” The word softly doesn’t convey who the character is or what his intentions are, but when you add the stage directions, suddenly the character comes to life. In the words of Strunk & White: “Do not dress up words by adding -ly to them, as if putting a hat on a horse.”

7. Exposition in Dialogue

Sometimes, writers use dialogue to convey information to the reader. Remember, the conversation is between the characters and the reader is just a casual observer. Suppose one character says to another: “Dude, you’ve failed all your classes two semesters in a row. Your parents are gonna have a cow.” Clearly Dude knows that he’s failed his classes two semesters in a row. He was there. He made it happen. The only reason for his buddy to tell him that in dialogue is because the writer needs to convey this valuable insight to the reader.

We see exposition in dialogue all the time—the comic book villain gives the “this is why I tried to take over the world” monologue, or a mentor character shows up just in time to give the protagonist a pep talk—but just because writers use this device doesn’t mean it works.

Repeat after me: dialogue is communication between characters, not communication between the writer and reader. Unless the character receiving the information doesn’t already know it, find another way to convey it to your reader.

8. Dialogue Blips

In real life people insert blips into dialogue like “um,” “so,” and “well.” They do this to give themselves time to think of what they’re going to say. But in fictional dialogue you have all the time in the world to figure out what the characters will say. These blips are not only unnecessary but also distracting. These hems and haws are the equivalent of red zits on your dialogue’s nose. They might seem insignificant, but they’ll distract readers so much they won’t see anything else. distraction. Sure, there may be the occasional situation where a “well” or a “hmm” or some other such blip might come in handy, but if you find your characters are leaning on these words too much, get rid of them pronto.

9. Breaking Character

Perhaps one of the biggest problems in dialogue is when a character says something that is out of character. This often happens because the writer is putting words in the character’s mouth that the character would never say. Does the character talk as though she’s memorized the dictionary, or does he simple slang?

Sometimes you can use the contrast between the character and the out-of-character dialogue for humor. Consider for example the movie Catch Me If You Can when con artist Frank Abagnale is posing as a doctor and tries to master doctor lingo by watching hospital soap operas. On those shows the doctors are always asking each other if they “concur” with a diagnosis, so when Frank finds himself having to impersonate a doctor, he keeps asking the other doctors if they “concur” even though it’s obvious to the audience that he has no idea what anybody is saying, much less what he’s concurring to. In this situation, the character’s fancy language underscores his ignorance about all the medical terminology being thrown at him.

Putting It All Together

In the end, these “rules” are not etched in stone and if you need to break one now and then, do it. Think of the Nine No’s as being like signal flares, telling you when to give a passage of dialogue a second look. If you need to use one of these Nine No’s, do it with intention rather than by accident or—worse yet—out of laziness. Like my middle school band teacher used to say:

“If you’re gonna play it wrong, make it good and loud and wrong.”

BIO:

Gabriela Pereira is a writer, speaker, and self-proclaimed word nerd who wants to challenge the status quo of higher education. As the founder and instigator of DIYMFA.com, her mission is to empower writers to take an entrepreneurial approach to their professional growth. Gabriela earned her MFA in creative writing from The New School and teaches at national conferences, regional workshops, and online. She is also the host of DIY MFA Radio, a popular podcast where she interviews bestselling authors and publishing experts. Her book DIY MFA: WRITE WITH FOCUS, READ WITH PURPOSE, BUILD YOUR COMMUNITY is out now from Writer’s Digest Books. To connect with Gabriela, join the word nerd crew, and get a free DIY MFA starter kit, go to: DIYMFA.com/join.

Related Posts:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

How to Write a Short Story That Captivates Your Reader

How to Overcome Writer’s Block Once and for All: My Surprising Solution

The post How to Create Dazzling Dialogue appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

How to Write Dazzling Dialogue

Guest blog by Gabriela Periera

Of all aspects of the writing craft, dialogue is by far my favorite. Maybe it’s because dialogue makes me feel like I’m in the scene with the characters or lets me see their dynamic personalities bounce off each other. Or maybe it’s just because I’m impatient and don’t like to weed through pages of boring description.

Whatever the reason, I always look forward to dialogue passages… except when the dialogue is bad. Because to paraphrase from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, when dialogue is bad it is horrid.

The good news is that there are a few easy ways to fix less-than-stellar dialogue. I call these the “Nine NO’s”—as opposed to the “Nine Nevers”—because while these are things that writers should try to avoid, they are not hard and fast rules. You should not have to commit verbal acrobatics in order eliminate them from your writing completely.

Here are the Nine No’s of Dialogue:

1. Name-Calling

Name-calling is when characters call each other by name in dialogue. For example:

“So Bill, how’s everything going?” Jill asked.

“Not too bad, Jill,” Bill replied. “Thanks for asking.”

While this tactic might seem like a convenient way to establish who is saying what, it also sounds terrible and people don’t speak this way in real conversations. Name-calling smacks of distrust—as though the writer is afraid the reader won’t figure out who’s talking—but instead of solving the problem, name-calling only makes the dialogue sound clunky and stilted.

2. Fussy Tags

Tags are the “he said, she said” part of dialogue. In other words, if you want to establish which character is talking, tags are the way to do it. The problem arises when writers get a carried away with tags, using words like cajoled, reiterated, or guffawed. Have you ever heard someone “guffaw” a line of dialogue? Didn’t think so.

When in doubt, use “said” because it blends into the background and doesn’t draw attention to itself. tags like “asked” or “replied” are also okay in moderation. But for the love of all that is literary, do not use fancy tags at random, just for the sake of switching things up. Fussy tags steal attention away from the important part of the dialogue: what the characters are saying.

3. Talking-Head Syndrome

Sometimes writers go to the opposite extreme, crafting dialogue that bounces back and forth between characters like a pingpong ball. When this happens, the reader has no idea where the characters are, or they’re even talking in the first place.

I call this Talking-Head Syndrome and the solution is simple:

Add stage directions.

If dialogue is the part that’s spoken by the characters, then stage directions are the actions that accompany those lines. Imagine the scene you’re writing is part of a play and you are the director. You need to tell the characters when to clear their throats, sip their tea, or grab the gun from the mantelpiece and pull the trigger.

Stage directions are especially useful if you want to create subtext. When a character’s actions contradict what he’s saying, that gives the reader a window into what the character is thinking or feeling. Remember, actions can speak much louder than words.

4. On-the-Nose Dialogue

On-the-nose dialogue is when people say exactly what they mean. This, of course, never happens in real life. Take for example that scene in the movie Clueless where the protagonist, Cher, comes downstairs wearing a revealing dress. This is the exchange she has with her father:

“What’s that?”

“A dress, Daddy.” She giggles.

“Says who?”

“Calvin Klein.”

If we take the dialogue literally, it seems like the father is asking his daughter about the outfit she is wearing. The truth is, this conversation has very little to do with couture and everything to do with the father-daughter relationship.

When he asks “What’s that?” Cher’s father is really saying “What on earth do you think you’re wearing?” But the subtext doesn’t end there.

Cher’s response is as sweet as it is patronizing, and when her dad responds with “Says who?” he might as well be telling her to go upstairs and change her clothes. Instead, she volleys back with a roll of the eyes and the words: “Calvin Klein.”

Game. Set. Match.

The dialogue itself consists of nine words, but it says so much more. This scene would be far less interesting—and less funny—if the characters say what they actually mean.

5. Rambling Start

In real life dialogue, people usually build up toward the heart of the conversation. They ask each other how they’re doing or comment about the weather, because that’s the polite thing to do. It might take several minutes until one of the speakers gets to the real reason for the conversation.

You don’t have time for small talk on the page. If you waste words on a rambling start, you risk losing your readers before you get to the good stuff. Skip to where the dialogue gets interesting and start there. Wouldn’t you rather read a passage that starts with “Why the hell have you been sleeping with my husband?” than something like “Hey Sally, nice to see you”? Forget the lead-up and get to the juicy stuff.

6. Adverb Overload

Nouns and verbs are the “meat and potatoes” of vibrant language. Adverbs are a condiment: a little goes a long way. This is especially true with dialogue.

Adverb overload is often a sign that you are not choosing the right verbs. If a verb is pulling its weight, you shouldn’t have to qualify it with an adverb. “He said softly” becomes much more specific when you say “He said, his breath tickling her ear” or “He said, his voice like syrup.” The word softly doesn’t convey who the character is or what his intentions are, but when you add the stage directions, suddenly the character comes to life. In the words of Strunk & White: “Do not dress up words by adding -ly to them, as if putting a hat on a horse.”

7. Exposition in Dialogue

Sometimes, writers use dialogue to convey information to the reader. Remember, the conversation is between the characters and the reader is just a casual observer. Suppose one character says to another: “Dude, you’ve failed all your classes two semesters in a row. Your parents are gonna have a cow.” Clearly Dude knows that he’s failed his classes two semesters in a row. He was there. He made it happen. The only reason for his buddy to tell him that in dialogue is because the writer needs to convey this valuable insight to the reader.

We see exposition in dialogue all the time—the comic book villain gives the “this is why I tried to take over the world” monologue, or a mentor character shows up just in time to give the protagonist a pep talk—but just because writers use this device doesn’t mean it works.

Repeat after me: dialogue is communication between characters, not communication between the writer and reader. Unless the character receiving the information doesn’t already know it, find another way to convey it to your reader.

8. Dialogue Blips

In real life people insert blips into dialogue like “um,” “so,” and “well.” They do this to give themselves time to think of what they’re going to say. But in fictional dialogue you have all the time in the world to figure out what the characters will say. These blips are not only unnecessary but also distracting. These hems and haws are the equivalent of red zits on your dialogue’s nose. They might seem insignificant, but they’ll distract readers so much they won’t see anything else. distraction. Sure, there may be the occasional situation where a “well” or a “hmm” or some other such blip might come in handy, but if you find your characters are leaning on these words too much, get rid of them pronto.

9. Breaking Character

Perhaps one of the biggest problems in dialogue is when a character says something that is out of character. This often happens because the writer is putting words in the character’s mouth that the character would never say. Does the character talk as though she’s memorized the dictionary, or does he simple slang?

Sometimes you can use the contrast between the character and the out-of-character dialogue for humor. Consider for example the movie Catch Me If You Can when con artist Frank Abagnale is posing as a doctor and tries to master doctor lingo by watching hospital soap operas. On those shows the doctors are always asking each other if they “concur” with a diagnosis, so when Frank finds himself having to impersonate a doctor, he keeps asking the other doctors if they “concur” even though it’s obvious to the audience that he has no idea what anybody is saying, much less what he’s concurring to. In this situation, the character’s fancy language underscores his ignorance about all the medical terminology being thrown at him.

Putting It All Together

In the end, these “rules” are not etched in stone and if you need to break one now and then, do it. Think of the Nine No’s as being like signal flares, telling you when to give a passage of dialogue a second look. If you need to use one of these Nine No’s, do it with intention rather than by accident or—worse yet—out of laziness. Like my middle school band teacher used to say:

“If you’re gonna play it wrong, make it good and loud and wrong.”

BIO:

Gabriela Pereira is a writer, speaker, and self-proclaimed word nerd who wants to challenge the status quo of higher education. As the founder and instigator of DIYMFA.com, her mission is to empower writers to take an entrepreneurial approach to their professional growth. Gabriela earned her MFA in creative writing from The New School and teaches at national conferences, regional workshops, and online. She is also the host of DIY MFA Radio, a popular podcast where she interviews bestselling authors and publishing experts. Her book DIY MFA: WRITE WITH FOCUS, READ WITH PURPOSE, BUILD YOUR COMMUNITY is out now from Writer’s Digest Books. To connect with Gabriela, join the word nerd crew, and get a free DIY MFA starter kit, go to: DIYMFA.com/join.

The post How to Write Dazzling Dialogue appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

July 4, 2017

How to Create Your Own Author Website in the Next Hour…And Why You Need To

If yo u’re an author, published yet or not, you need your own website. Period.

u’re an author, published yet or not, you need your own website. Period.

Why am I so forthright about this? Because of the realities of publishing today.

You’ve heard and read of your need for a platform—a following, a tribe, visibility. Well, that all starts with your own author website.

Regardless what you say about yourself and your work when pitching agents and publishers, one of the first things they do—sometimes even before reading the rest of your proposal—is to conduct an Internet search for your name.

The first thing that ought to pop up is your author website. Google my name and you’ll be directed to JerryJenkins.com.

In fact, you’d be hard-pressed to Google any published author’s name and not find their website with a custom domain name (usually, like mine, their own name).

No way around it, this is crucial today.

Your author website serves as a hub for your writing. It’s where agents, publishers, readers, and fans can learn about your work, put a face to your name, and contact you.

I urge you to avoid the temptation to settle for one of the quick and easy website solutions that looks like everyone else’s and has a small-time feel. Maybe you’ve already done this, unaware of a vastly superior option.

To gain serious credibility with publishers and agents, I recommend creating your own great-looking custom domain site…

…which I’m about to show you in this guide.

Give me about half an hour, and you—and anyone you tell about it—could be admiring a gorgeous new site all your own.

Imagine a publisher trying to decide between you and another writer trying to break into the business or pitch a book. What will they find if they Google your name?

A handsome, compelling site can put you ahead of the pack by giving you:

1. Instant credibility

Just like dressing your best for a job interview, your professional-looking website puts your best foot forward. It establishes you as a serious professional.

2. A showcase for your work.

Your author website becomes your home base, as if you had a corporate headquarters. It’s your showroom on the Internet where you can display your best work.

Your author website lets you host a blog, as I do here. That becomes another showcase of your writing, and it also lets others contact you. People who enjoy a blog like to get in touch with the writer and say so. They also like commenting, discussing, criticizing, praising, opining.

And once you’re a published author, this is where readers of your book can connect with you.

3. An opportunity to build a following.

This is one of the best benefits of an author website, because it’s what publishers and agents look for in potential authors. Here is where you can collect email addresses and build a list.

Get your growing tribe interacting with you and with each other by posing a simple question or taking a brief survey on their favorite things: books, movies, celebrities, you name it.

You’ll find that as your list of followers grows, you’ll gain self-confidence. But even better, publishers will discover you have a following, a tribe—a platform.

Creating an Author Website: The Simple Process

So, you’re convinced of the need and eager to enjoy the advantages of your own author website, but maybe, like me, you’re not a techie. The whole idea of creating a website intimidates you.

Don’t worry. With the following simple instructions, you should be able to build yours from scratch in the next hour. Imagine enjoying your very own great-looking site, bearing the .com name you choose (Hint: it should always be your name).

Here’s all you need to do:

1. Choose a company to host your site.

If even the idea of “hosting” a site sounds foreign to you (it did to me at first too), think of the Internet as an apartment complex. Tenants decorate their apartments the way they want—but they don’t own that space. The landlord does. The tenants simply rent.

On the Internet, a few landlords own the hardware that makes websites work. These landlords are called hosting companies, so you rent your online space from them.

Of course, they don’t own your website. You own that and are responsible for everything posted there. Your hosting company sees to it that your website is broadcast onto the internet.

For most budding authors and bloggers, I recommend Bluehost as your hosting company. Until you start reaching hundreds of thousands of readers, Bluehost should be perfect for you.

Why? Because:

Bluehost is inexpensive. It broadcasts a website for less than $9 per month, about 30¢ a day—a wise investment in your writing career. Plus, they offer a 30-day money back guarantee.

Bluehost has great customer service. Their people are available and easily accessible 24/7.

Bluehost works with WordPress.

WordPress is a simple tool that helps you easily create a good-looking website. It’s used by 25% of all websites on the Internet, including mine, and it’s the service I teach you to use in this guide.

Bluehost has supported WordPress for over 10 years and has in-house WordPress experts, if you ever have a question about it.

To get started with Bluehost, click this link.

Full disclosure: I get a commission (at no extra cost to you) if you use this link to sign up for a Bluehost service. But I’d recommend Bluehost regardless. I’ve been a satisfied customer, and they provide a fantastic service for authors.

After that page opens in your web browser, click the green “get started now” button.

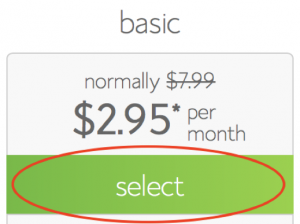

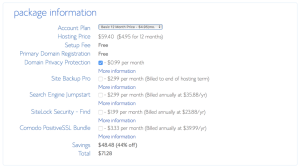

That takes you to a page where you can select your plan from four options:

Basic ($8.99/month)

Plus ($12.99/month)

Prime ($16.99/month)

Pro ($25.99/month)

Note: Bluehost requires at least a one-year payment, which is how they can remain so affordable. The prices above reflect their standard 12-month plan.

Bluehost often runs promotions that provide discounts for first-time users.

Their longer term plans will save you money for two reasons:

The longer the term, the lower the monthly price.

Their promotional prices apply to the first term only. So, the longer your first term, the longer you receive the discounted price.

If you’re new to this and envision one website, Basic should be all you need. If you’re considering multiple websites, you’ll want to study the more extensive plans.

Click the green “select” button under the price.

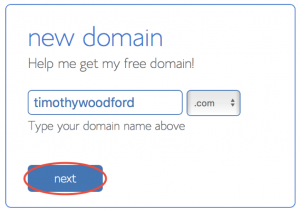

2. Pick a domain name.

This is easier than it sounds—just use your name!

I recommend capitalizing each of your names for easier readability, but that’s not mandatory.

If your domain name is already in use, you’ll get a message that says your choice is “not available for registration” or something similar.

In that case, you have a couple options:

A. Choose a different website extension.

“.com” is preferred because it’s most common, but “.net” or “.co” work just as well.

B. Choose a new domain name.

Keep it simple—“TimothyWoodfordWriting.com” is good; “TimothyWoodfordsGreatWritingWebsite.com” is not. Keep your domain name simple, professional, and clear—not quirky or extravagant.

Some other ideas:

[YourName]Author.com

[YourName]Writer.com

[YourName]Books.com

[YourName]Writes.com

[YourName]Blog.com

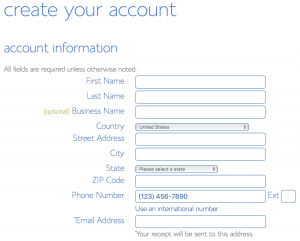

After you type in your new domain name, click “Next” and you will be taken to the “create your account” page.

After completing this form, scroll down and complete the “package information” section. Bluehost tries to upsell a few things here.

In my opinion, the one worth buying is Domain Privacy Protection—but it’s your call. With the Prime Plan, this is included free. It is not included in Plus or Basic.

Domain Privacy Protection ensures that when someone looks up your website, they do not see your individual contact information, but rather Bluehost’s. It’s an extra 99¢ per month.

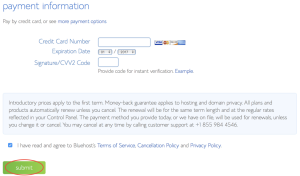

The last section on this page is “payment information.” Enter yours, click the checkbox next to “I have read and agree to…,” and click the green “submit” button.

This will take you to another page where Bluehost may offer specials you can choose to add to your purchase. Or not. You can click the “no thanks” button.

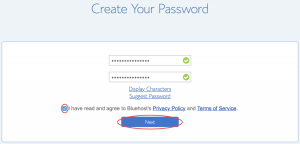

Then you will be taken to a “Welcome to Bluehost” page to create a password.

On the next page, create your password, click the checkbox next to “I have read and agree to…,” then click “Next.”

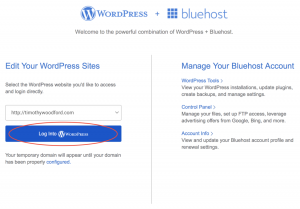

After this, you’ll be taken to a WordPress + Bluehost page, where you can begin to edit your site. Click the blue “Log Into WordPress” button on the left side of the screen.

3. Launch your website.

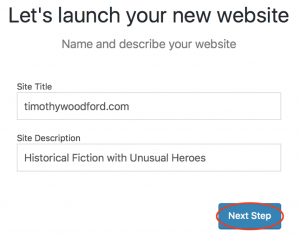

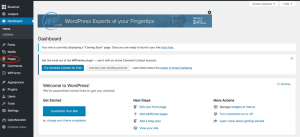

After that, you’ll be taken to your new WordPress dashboard. Let’s make your site look professional! Click “Business.”

Now you want to create a tagline. (Example: Mine is “New York Times Bestselling Novelist & Biographer.”) Jean Oram has a great post on creating author taglines. You’ll find more very effective examples there, which should give you some powerful ideas for your own.

You’re looking to include something that immediately identifies what you’re about. Novelist Brandilyn Collins uses Seatbelt Suspense®. Novelist DiAnn Mills uses Expect an adventure.

After you create your own tagline, click “Next Step.”

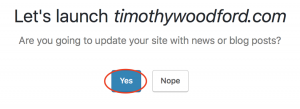

On the next page, you’ll be asked if you’d like to “update your site with news or blog posts.” I recommend clicking “Yes,” even if all you enter there for now is a paragraph saying, “Welcome to my new blog! Check back here on [date] when I plan to blog on [subject]. See you then!”

Your goal should be to create a blog through which you can build a following. If you’d rather skip this step for now and have your first entry be your first complete blog post, that’s fine, too.

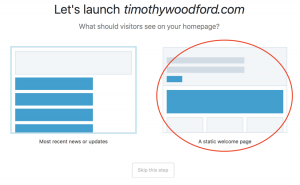

Next, give your visitors access to a welcome page (some call this the landing page) where they can get acquainted with you and your site, even before you start blogging consistently. This would be a good place for a photo of you and a brief bio. I’ll get to those specifics a bit later.

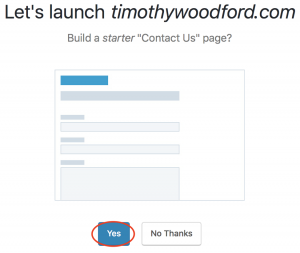

The next page asks if you would like WordPress to create a “Contact Us” page. Click “yes.” This will give site visitors access to you. If you’re like me, this will quickly become one of your favorite features. I love to know people are visiting and what they think. But of course the best benefit is giving agents or publishers a quick way to reach you if they happen to see something they like. While that may seem a remote possibility now, new authors are discovered every day.

And remember, when you’re pitching you work, your website is the first place an agent or editor will look for to learn more about you. You want it—and you—to appear as engaging and professional as possible.

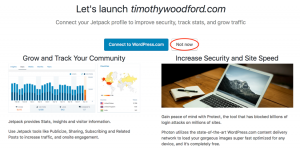

The next page asks if you would like to connect your Jetpack profile to WordPress. This refers to a statistical tracking program some site owners love and others ignore. You can determine later if it’s something you want to pursue. Click “Not now.” You can always come back to this later.

The next page gives you the option to customize your site. Let’s wait on that for now too. Click the blue “X” in the right-hand corner of the window.

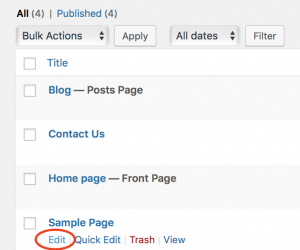

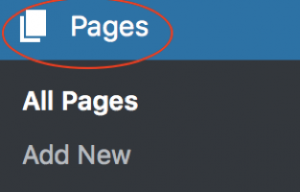

This takes you to your WordPress Dashboard. Click “Pages” on the left sidebar.

After that, click “Edit” under “Sample Page.”

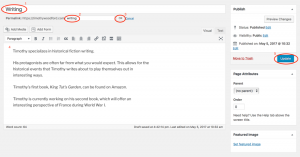

You have a few things to do here:

Step 1: Change the title of the page to “Writing.”

Step 2: Change the URL extension to “writing.” URL stands for Universal Resource Locator (I had to look that up), and simply means the address you type in to go to any webpage. The extension is what comes after that web address. For instance, notice the extension to my webpage URL, which takes you to my How to Write a Book guide: https://www.jerryjenkins.com/how-to-write-a-book/. (This is also referred to as a permalink in WordPress.)

Step 3: Click the “OK” button.

Step 4: Add a description of your writing. Remember brevity and professionalism, but be sure you include what visitors—including agents and publishers—would want to see.

One departure I would make from Bluehost’s example below is to urge you to write in the first-person. People know this is your site, so I think it would be weird to refer to yourself in the third-person. Be open, engaging, friendly, and personable. Example: I’m working on my first novel, the story of a writing coach who tries to make technical-sounding computer lingo understandable to aspiring authors…

Tell of your previous projects, and add links (clickable web addresses) to them. If that’s beyond your capabilities right now, trust me, someone in your orbit will be able to show you how to do this. If I learned it, you certainly can. Pretty much anyone under 30 will be computer literate and can help you quickly master this. Meanwhile, I’ll list the steps if you’d like to try it on your own.

Step 5: Click the blue “Update” button.

If you want to add a link to a site where visitors can buy your book or see a sample of your writing, here’s how to do it:

Step 1: Highlight the text you want to turn into a hyperlink (making it clickable). For instance, highlight “A list of my published works.”

Step 2: Click the chain link icon (circled in red below).

Step 3: Copy and paste into the text box the URL (web address, like www.JerryJenkins.com/books) you want to link to.

Step 4: Click the blue Apply icon. That turns your text into a clickable URL, and it will now look like this: A list of my published works. (Right click on that and you’ll see the URL it would take you to.)

After you’ve done that, click the blue “Update” button.

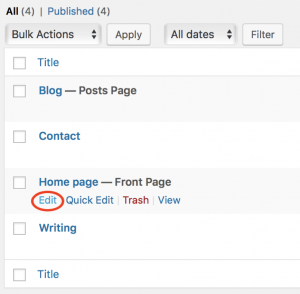

After you click the “Update” button, click “Pages” in the sidebar on the left side of the screen.

Scroll down to the “Home page” label, and click “Edit.”

This will be that first page visitors see at your site—the welcome or landing page. Remember, this is where you show a good photo of yourself and tell a bit about yourself.

Step 1: Change the title of the page to “About.”

Step 2: Click the “Add Media” button.

Click the “Select Files” button on the page that opens, and find the photo of yourself you want to use.

Click “Insert into page.”

After your photo has been inserted into the page, add a short bio. Focus mainly on your writing, but add a little personal information as well.

Walking the line between just enough and too much can be tricky. Write in the first-person, but remember that less is more. People will be interested in your family and where you live, but lean toward, “We’re the proud parents of…” rather than, “…where we’re raising the three most adorable kids in the history of the universe.”

June 21, 2017

10 Tips for Pitching Your Writing

Literary agents and publishers reject more manuscripts today than ever before—well more than 90%.

Literary agents and publishers reject more manuscripts today than ever before—well more than 90%.

Though they want your submissions—they really do—and are sincerely hoping they’ll discover the next successful writer, the sheer volume of submissions causes many to not even respond unless their answer is Yes.

Check the Submission Guidelines of many agents and publishers and you’ll find they tell you this upfront—some variation of “If you don’t hear from us in due time, assume we’re not interested.”

That sounds as lazy and inconsiderate to me as it does to you. How hard is it in this day of single-keystroke technology to at least let a writer know, “Sorry, we’re passing”?

I tell you all this not to discourage you but to give you a realistic picture of what you face in the marketplace.

And I have advice on how to separate yourself from much of the competition to give yourself the best chance at landing a contract.

Make a great first impression by nailing your presentation. Your query letter or proposal must look like you know what you’re doing. Avoid amateur mistakes and put your best foot forward by applying these techniques:

10 Ways to Enhance Your Queries and Proposals

1. You’ve heard the advertising slogan Just do it. Learn to Just say it. Write as if talking to a friend or writing a letter. Good writing is not filled with adjectives and adverbs. It consists of powerful nouns and verbs. Read what sells. You’ll usually find it simple and straightforward.

2. Avoid a colored or tinted screen background as your stationery, even if you did that when we all used real paper and snail mail. Editors universally see this as the sign of a rookie. The emphasis should be on your idea, content, and writing—not a fancy look. Black type on a white background is what they’re looking for.

3. Avoid boldfacing or ALL CAPS anywhere in a letter, proposal, or manuscript, and never use more than one font (typeface). Make sure that font is a serif type (not sans serif as this blog is). That means 12 pt. Times New Roman or something very similar.

4. Your manuscript should be aligned Left not Justified—which would make the copy on the right look like a published book. Justified Right causes awkward spacing between words to make it work, and you’re submitting a manuscript to be considered and hopefully edited, not a book ready for the printer yet.

5. While your letter can and should be single spaced, a manuscript, even transmitted electronically, must be double-spaced (not single- or triple-spaced, or even some variation just because it’s your computer program’s default choice). Also, delete extra spaces between sentences. Though you may have been taught to use two, one is what you want, because that’s how sentences appear in print.

6. Set the space between paragraphs to zero, not another default. There should be one doublespace, just like the space between lines.

7. Publishers are looking for positivity, even if your subject is difficult. Title your work Winning Over Depression, not Don’t Let Depression Defeat You.

8.The word by rarely appears on the cover of a book unless it is self-published, and even then it is the sign of an amateur. Your byline should consist of only your name.

9. Another amateur error is misspelling Acknowledgments (as Acknowledgements, a British variation) or Foreword (as Forward or Foreward or Forword). Foreword means “before the text” and has nothing to do with direction.

10. If the publisher asks for a hard copy (rare these days), your manuscript should not be bound, stapled, clipped, or in a three-ring binder. Send the pages stacked, each numbered and bearing your name.

What are you planning to submit next? Tell me in the Comments below.

The post 10 Tips for Pitching Your Writing appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

June 6, 2017

How to Write a Short Story That Captivates Your Reader

Trying to write a short story is the perfect place to begin your writing career.

Why?

Because it reveals many of the obstacles, dilemmas, and questions you’ll face when creating fiction of any length. If you find these things knotty in a short story, imagine how profound they would be in a book-length tale.

Most writers need to get a quarter million clichés out of their systems before they hope to sell something. And they need to learn the difference between imitating their favorite writers and emulating their best techniques.

Mastering even a few of the elements of fiction while learning the craft will prove to be quick wins for you as you gain momentum as a writer.

I don’t mean to imply that learning how to write a short story is easier than learning how to write a novel—only that as a neophyte you might find the process more manageable in smaller bites.

So let’s start at the beginning.

What Is a Short Story?

Don’t make the mistake of referring to short nonfiction articles as short stories. In the publishing world, short story always refers to fiction. And short stories come varying shapes and sizes:

Traditional: 1,500-5000 words

Flash Fiction: 500-1,000 words

Micro Fiction: 5 to 350 words

Is there really a market for a short story of 5,000 words (roughly 20 double-spaced manuscript pages)? Some publications and contests accept entries that long, but it’s easier and more common to sell a short story in the 1,500- to 3,000-word range.

And on the other end of the spectrum, you may wonder if I’m serious about short stories of fewer than 10 words (Micro Fiction). Well, sort of. They are really more gimmicks, but they exist. The most famous was Ernest Hemingway’s response to a bet that he couldn’t write fiction that short. He wrote: For sale: baby shoes. Never worn.

That implied a vast backstory and deep emotion.

Writing a compelling short story is an art, despite that they are so much more concise than novels. Which is why I created this complete guide:

9 Steps to Writing a Short Story

1. Read as Many Great Short Stories as You Can Find

Read hundreds of them—especially the classics.

You learn this genre by familiarizing yourself with the best. See yourself as an apprentice. Watch, evaluate, analyze the experts, then try to emulate their work. Soon you’ll learn enough about how to write a short story that you can start developing your own style.

A lot of the skills you need can be learned through osmosis.

Where to start? Read Bret Lott, a modern-day master. (He chose one of my short stories for one of his collections.)

Reading two or three dozen short stories should give you an idea of their structure and style. That should spur you to try one of your own while continuing to read dozens more.

Remember, you won’t likely start with something sensational, but what you’ve learned through your reading—as well as what you’ll learn from your own writing—should give you confidence. You’ll be on your way.

2. Aim for the Heart

The most effective short stories evoke deep emotions in the reader.

What will move them? The same things that probably move you:

Love

Redemption

Justice

Freedom

Heroic sacrifice

What else?

3. Narrow Your Scope

It should go without saying that there’s a drastic difference between a 450-page, 100,000-word novel and a 10-page, 2000-word short story. One can accommodate an epic sweep of a story and cover decades with an extensive cast of characters. The other must pack an emotional wallop and tell a compelling story with a beginning, a middle, and an end—with about 2% of the number of words.

Naturally, that dramatically restricts your number of characters, scenes, and even plot points. The best short stories usually encompass only a short slice of the main character’s life—often only one scene or incident that must also bear the weight of your Deeper Question, your theme or what it is you’re really trying to say.

Tightening Tips

If your main character needs a cohort or a sounding board, don’t give her two. Combine characters where you can.

Avoid long blocks of description; rather, write just enough to trigger the theater of your reader’s mind.

Eliminate scenes that merely get your characters from one place to another. The reader doesn’t care how they got there, so you can simply write: Late that afternoon, Jim met Sharon at a coffee shop…

Your goal is to get to a resounding ending by portraying a poignant incident that tell a story in itself and represents a bigger picture.

4. Make Your Title Sing

Work hard on what to call your short story. Yes, it might get changed by editors, but it must grab their attention first. They’ll want it to stand out to readers among a wide range of competing stories, and so do you.

5. Use the Classic Story Structure

Once your title has pulled the reader in, how do you hold his interest? As you might imagine, this is as crucial in a short story as it is in a novel. So use the same basic approach:

Plunge your character into terrible trouble from the get-go.

Of course, terrible trouble means something different for different genres.

In a thriller, your character might find himself in physical danger, a life or death situation.

In a love story, the trouble might be emotional, a heroine torn between two lovers.

In a mystery, your main character might witness a crime, and then be accused of it.

Don’t waste time setting up the story. Get on with it. Tell your reader just enough to make her care about your main character, then get to the the problem, the quest, the challenge, the danger—whatever it is that drives your story.

6. Suggest Backstory, Don’t Elaborate

You don’t have the space or time to flash back or cover a character’s entire backstory. Rather than recite how a Frenchman got to America, merely mention the accent he had hoped to leave behind when he emigrated to the U.S. from Paris.

Don’t spend a paragraph describing a winter morning. Layer that bit of sensory detail into the narrative by showing your character covering her face with her scarf against the frigid wind.

7. When in Doubt, Leave it Out

Short stories are, by definition, short. Every sentence must count. If even one word seems extraneous, it has to go.

8. Ensure a Satisfying Ending

This is a must. Bring down the curtain with a satisfying thud. In a short story this can often be accomplished quickly, as long as it resounds with the reader and makes her nod. It can’t seem forced or contrived or feel as if the story has ended too soon.

In a modern day version of the Prodigal Son, a character calls from a taxi and leaves a message that if he’s allowed to come home, his father should leave the front porch light on. Otherwise, he’ll understand and just move on.

The rest of the story is him telling the cabbie how deeply his life choices have hurt his family. The story ends with the taxi pulling into view of his childhood home, only to find not only the porch light on, but also every light in the house and more out in the yard.

That ending needed no elaboration. We don’t even need to be shown the reunion, the embrace, the tears, the talk. The lights say it all.

9. Cut Like Your Story’s Life Depends on It

Because it does.

When you’ve finished your story, the real work has just begun. It’s time for you to become a ferocious self-editor. Once you’re happy with the flow of the story, every other element should be examined for perfection: spelling, grammar, punctuation, sentence construction, word choice, elimination of clichés, redundancies, you name it. Also, pour over the manuscript looking for ways to engage your reader’s senses and emotions.

All writing is rewriting. And remember, tightening nearly always adds power. Omit needless words.

Examples:

She shrugged her shoulders.

He blinked his eyes.

Jim walked in through the open door and sat down in a chair.

The crowd clapped their hands and stomped their feet.

Learn to tighten and give yourself the best chance to write short stories that captivate your reader.

Where to Sell Your Short Stories

To get the lowdown on this, I consulted my longtime friend and colleague, Dr. Dennis Hensley—director of Taylor University’s writing program (in my opinion the best in the country). Also a widely-published short story writer, Doc says that—contrary to what many believe—the short story market is NOT dead.

He recommends these main market targets:

1. Contests

Doc highly recommends entering contests, because the winners usually get published in either a magazine or online—which means instant visibility for your name.

Many pay cash prizes up to $5,000. But even those that don’t offer cash give you awards that lend credibility to your next short story pitch.

2. Genre-Specific Periodicals

Such publications cater to audiences who love stories written in their particular literary category. If you can score with one of these, the editor will likely come back to you for more.

Any time you can work with an editor, you’re developing a skill that will well serve your writing.

3. Popular Magazines

Plenty of print and online magazines still buy and publish short stories. A few examples:

The Atlantic

Harper’s Magazine

Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine

The New Yorker

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine

Woman’s World

4. Literary Magazines

While, admittedly, this market calls for a more intellectual than mass market approach to writing, getting published in one is still a win. If you enjoy this genre and can compete here, Doc Hensley says you get more than just exposure through a byline; it also helps you establish a track record and might even get you discovered by a book publisher, as editors and agents scour such magazines looking for talent.

Here’s a list of literary magazine short story markets.

5. Short Story Books

Yes, some publishers still publish these. They might consist entirely of short stories from one author, or they might contain the work of several, but usually tied together by theme.

Regardless which style you’re interested in, remember that while each story should fit the whole, it must also work on its own, complete and satisfying in itself.

What’s Your Story?

You’ll know yours has potential when you can distill its idea to a single sentence. You’ll find that this will keep you on track during the writing stage. Here’s mine for a piece I titled Midnight Clear (which became a movie starring Stephen Baldwin):

An estranged son visits his lonely mother on Christmas Eve before his planned suicide, unaware she is planning the same, and the encounter gives them each reasons to go on.

In the comments below, write the one-sentence essence of your short story.

The post How to Write a Short Story That Captivates Your Reader appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

How to Write Short Stories that Captivate Your Reader

Ever dived into a new interest hoping to be an expert from day one?

Ever dived into a new interest hoping to be an expert from day one?

I have.

Bowling looked easy. So did racquetball. Someone even made banjo playing look simple.

So I skipped learning the basics, had no clue of the fundamentals, and jumped in.

You can guess the results—fall-on-my-face failure.

I see beginning fiction writers do this every day. They think writing could become a hobby, a diversion, something they could excel at “if only I had the time.”

So they try to begin their careers before learning the craft. Many even start by writing a novel.

That’s like starting your education in graduate school when you should be in kindergarten. Or like me hauling my brand new banjo onto the stage of the Grand Ole Opry.

A novel is not where you start—it’s where you arrive.

So how should a fiction writer begin? By reading.

That’s right. Don’t even attempt to compete in the marketplace of your chosen genre without immersing yourself in the discipline.

What are the rules of the game, the assumptions, the expectations of readers? How do the best writers do what you want to do?

Maybe you aim to change the genre, improve on it, break the rules. Fine, but you’d better know what they are before your set about reforming them.

Next, when you try your hand at writing, don’t start with a 300-400-page manuscript. Learn the basics first: things like dialogue, point of view, characterization, description, tension, conflict, setups and payoffs, submitting your story, working with an editor.

Start with short stuff: short stories or even flash fiction.

Trying to write a short story is the perfect place to begin, because it reveals many of the obstacles, dilemmas, and questions you’ll face when creating fiction of any length. If you find these things knotty in a short story, imagine how profound they would be in a book-length tale.

Most writers need to get a quarter million clichés out of their systems before they hope to sell something. And they need to learn the difference between imitating their favorite writers and emulating their best techniques.

Mastering even a few of the elements of fiction while learning the craft will prove to be quick wins for you as you gain momentum as a writer.

I don’t mean to imply that learning to write a short story is easier than learning to write a novel—only that as a neophyte you might find the process more manageable in smaller bites.

So let’s start at the beginning.

What Is a Short Story?

Don’t make the mistake of referring to short nonfiction articles as short stories. In the publishing world, short story always refers to fiction. And short stories come varying shapes and sizes:

Traditional: 1,500-5000 words

Flash Fiction: 500-1,000 words

Micro Fiction: 5 to 350 words

Is there really a market for a short story of 5,000 words (roughly 20 double-spaced manuscript pages)? Some publications and contests accept entries that long, but it’s easier and more common to sell a short story in the 1,500- to 3,000-word range.

And on the other end of the spectrum, you may wonder if I’m serious about short stories of fewer than 10 words (Micro Fiction). Well, sort of. They are really more gimmicks, but they exist. The most famous was Ernest Hemingway’s response to a bet that he couldn’t write fiction that short. He wrote: For sale: baby shoes. Never worn.