Jerry B. Jenkins's Blog, page 8

September 14, 2021

5 Types of Conflict to Use For Memorable Stories

Stories without conflict, where the main character faces zero opposition, fail because they bore readers.

In real life, harmony and agreement are worthy goals that produce a harmonious existence. But such is no recipe for stories that captivate readers.

Readers love conflict. It’s the engine of compelling fiction.

Conflict creates tension, and tension keeps readers turning the pages.

Internal and External ConflictAt the risk of insulting your intelligence, these definitions are self-explanatory. Internal conflict is your main character’s battle with his* own demons, self-doubt, etc.

[*Note: I use male pronouns to refer to both heroes and heroines.]

For instance, he might struggle with desiring independence while fearing stepping into the world alone.

External conflict is simply the obstacle or challenge your character faces. What does he want or need, what are the stakes, and what stands in his way?

Internal and external conflict work together. Your character’s fears, doubts, or false beliefs often arise from outside forces and in turn make it tougher for him to overcome them.

5 Types of ConflictMan vs. SelfThis type of conflict is usually caused by something external — but the battle itself takes place within. Your character might fight opposing desires — such as whether to violate his moral principles in the pursuit of self-gain.

Internal conflict can manifest itself in dialogue, through action or inaction, in thoughts, or even through dreams, nightmares, or hallucinations.

Example: The Narrator in Fight Club conflicts with society (which he finds empty and consumeristic), with his boss, and with others, but the story is ultimately about the internal conflict between two halves of his personality.

Man vs. ManDon’t make the mistake of assuming this type of conflict requires physical fighting or even an argument — though, of course, those also fit the definition. Conflict between the hero and villain is common.

But a character might also oppose your protagonist with his best interest in mind. For instance, a father might try to keep his teenager close, conflicting with the teen’s desire for independence.

Example: The conflict in Iron Man is a power struggle for the future of Stark Industries — between Tony Stark and his former mentor, Obadiah Stane.

Man vs. Nature

When a character struggles to survive in a hostile environment — such as on a mountain, or in a desert, ocean, or jungle — he might face extreme cold or heat, dangerous animals, or other threats to his life.

This is one of the conflict types often present in dystopian stories where the world has been devastated by a cataclysmic event like a plague or a nuclear apocalypse.

Example: The conflict between humans and dinosaurs in Jurassic Park.

Man vs. SocietyThis type of conflict pits a character against his government, the police, the military, or some other powerful force — including social norms. It’s usually most effective when Society is personified by a specific villain.

Example: Atticus Finch defending a black man in To Kill a Mockingbird, despite the pervasive racism of the time.

Man vs. Supernatural

Characters fighting vampires, werewolves, aliens, or wizards usually occurs in science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels.

Example: Buffy (and her friends) taking on vampires and demons in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

How to Create Conflict in a StoryThe best stories involve layers of conflict. Your hero might fight the villain — and his own self-doubt. Or your hero might struggle against both society and nature, perhaps thrown out of his community to survive in the wilderness.

The more types of conflict you inject in your story, the more compelling readers are likely to find it… and the more powerful your ending will be.

Stories Need Conflict — and Plenty of ItIf you’ve stalled halfway through your writing because scenes seem to fall flat, do whatever you need to to inject conflict. Is it sarcasm, a character flying off the handle for seemingly no reason, a friend all of a sudden in your character’s face?

As soon as that conflict is inserted, you (and your characters) must scramble to deal with it. And that creates page-turning tension. What’s going on?

Trust your gut, and your characters to the challenge.

For more help adding conflict to your stories, check out my articles on character motivation, character empathy, and story structure.

The post 5 Types of Conflict to Use For Memorable Stories appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

6 Types of Conflict to Use For Memorable Stories

Stories without conflict, where the main character faces zero opposition, fail because they bore readers.

In real life, harmony and agreement are worthy goals that produce a harmonious existence. But such is no recipe for stories that captivate readers.

Readers love conflict. It’s the engine of compelling fiction.

Conflict creates tension, and tension keeps readers turning the pages.

Internal and External ConflictAt the risk of insulting your intelligence, these definitions are self-explanatory. Internal conflict is your main character’s battle with his* own demons, self-doubt, etc.

[*Note: I use male pronouns to refer to both heroes and heroines.]

For instance, he might struggle with desiring independence while fearing stepping into the world alone.

External conflict is simply the obstacle or challenge your character faces. What does he want or need, what are the stakes, and what stands in his way?

Internal and external conflict work together. Your character’s fears, doubts, or false beliefs often arise from outside forces and in turn make it tougher for him to overcome them.

6 Types of ConflictMan vs. SelfThis type of conflict is usually caused by something external — but the battle itself takes place within. Your character might fight opposing desires — such as whether to violate his moral principles in the pursuit of self-gain.

Internal conflict can manifest itself in dialogue, through action or inaction, in thoughts, or even through dreams, nightmares, or hallucinations.

Example: The Narrator in Fight Club conflicts with society (which he finds empty and consumeristic), with his boss, and with others, but the story is ultimately about the internal conflict between two halves of his personality.

Man vs. ManDon’t make the mistake of assuming this type of conflict requires physical fighting or even an argument — though, of course, those also fit the definition. Conflict between the hero and villain is common.

But a character might also oppose your protagonist with his best interest in mind. For instance, a father might try to keep his teenager close, conflicting with the teen’s desire for independence.

Example: The conflict in Iron Man is a power struggle for the future of Stark Industries — between Tony Stark and his former mentor, Obadiah Stane.

Man vs. Nature

When a character struggles to survive in a hostile environment — such as on a mountain, or in a desert, ocean, or jungle — he might face extreme cold or heat, dangerous animals, or other threats to his life.

This is one of the conflict types often present in dystopian stories where the world has been devastated by a cataclysmic event like a plague or a nuclear apocalypse.

Example: The conflict between humans and dinosaurs in Jurassic Park.

Man vs. SocietyThis type of conflict pits a character against his government, the police, the military, or some other powerful force — including social norms. It’s usually most effective when Society is personified by a specific villain.

Example: Atticus Finch defending a black man in To Kill a Mockingbird, despite the pervasive racism of the time.

Man vs. Supernatural

Characters fighting vampires, werewolves, aliens, or wizards usually occurs in science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels.

Example: Buffy (and her friends) taking on vampires and demons in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

How to Create Conflict in a StoryThe best stories involve layers of conflict. Your hero might fight the villain — and his own self-doubt. Or your hero might struggle against both society and nature, perhaps thrown out of his community to survive in the wilderness.

The more types of conflict you inject in your story, the more compelling readers are likely to find it… and the more powerful your ending will be.

Stories Need Conflict — and Plenty of ItIf you’ve stalled halfway through your writing because scenes seem to fall flat, do whatever you need to to inject conflict. Is it sarcasm, a character flying off the handle for seemingly no reason, a friend all of a sudden in your character’s face?

As soon as that conflict is inserted, you (and your characters) must scramble to deal with it. And that creates page-turning tension. What’s going on?

Trust your gut, and your characters to the challenge.

For more help adding conflict to your stories, check out my articles on character motivation, character empathy, and story structure.

The post 6 Types of Conflict to Use For Memorable Stories appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

September 7, 2021

A Step-by-Step Guide to Immersive World Building

A book like A Game of Thrones, a movie like Star Wars, or even a video game like Final Fantasy can make it appear their creators have effortlessly built a fantasy world out of nothing.

In fact, these worlds may feel as real as the world you live in.

How do they do it? More importantly, how can you do it?

More than two-thirds of my 200 books are novels, but creating fictional worlds never seems to get easier.

It’s an art, and in genres such as Fantasy or Science Fiction, world building is more important than ever. It can make or break your story.

In this guide, I’ll give you tips to follow and errors to avoid. But first…

Need help writing your novel? Click here to download my ultimate 12-step guide.

What is World Building?

Writing a story is much like building a house — you can have all the right ideas, materials, and tools, but if your foundation isn’t solid, not even the most beautiful structure will stand.

World building is how you create that foundation — the Where of your story.

World building involves more than just the setting. It can be as complex as a unique venue with exotic creatures, rich political histories, and even new religions. Or it can be as simple as tweaking the history of the world we live in.

Go as big as you want, but remember: world building is serious business.

Create a world in which readers can lose themselves.

Do this well and they become not just fans, but also fanatics. Like those who obsess over:

Star Wars

Star Trek

Harry Potter

A Game of Thrones

The Marvel Universe

Halo

Each approaches world building in a different way:

1. Real-World Fantasy

Here you set your story in the world we live in, but your plot is either based on a real event (as in Outlander) or is one in which historical events occur differently (for instance, had Germany won World War 2).

In Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, he imagines a world in which Franklin Roosevelt was assassinated in the early 1930s.

2. Second-World Fantasy

Here you create new lands, species, and government. You also invent a world rich in its own history, geography, and purpose.

Examples include:

A Game of Thrones

The Lord of the Rings

Star Wars

Discworld

Eragon

Some novels combine the Real World and Second World Fantasy. The Harry Potter series, for instance, is set in the world we live in but with rules and history foreign to us.

(The Chronicles of Narnia and Alice in Wonderland are also examples of this.)

Your job is to take readers on a journey so compelling they can’t help but keep reading to the very end.

A World Building Guide

Step 1: Plan but Don’t Over-Plan

Outliners prefer to map out everything before they start writing.

Pantsers (those who write by the seat of their pants) write as a process of discovery — or, as Stephen King puts it, they “put interesting characters in difficult situations and write to find out what happens.”

Though I’m a Pantser, I can tell you that discovering a new world is a whole lot harder than building it before you get too deep into the writing.

Build your world first, then you can better focus on your story.

However, over-planning can also be a problem.

Many fantasy writers tell me they become so engrossed in world building that they find reasons not to write.

World building must not come at the expense of your story.

If you’re like me, you may have to spend more time planning than you’re used to.

If you’re an Outliner, draw a line in the sand and start writing as soon as you’re ready, even if you suspect you’ll have more spadework to do as you go.

Step 2: Describe Your World

Once you’ve determined your genre, paint for your reader a world that transports them, allowing them to see, smell, hear, and touch their surroundings. Show them, don’t tell them.

Which idea for this new world most excites you ? An other-worldly landscape? A new language? Strange creatures? Build on that to give you the momentum you need when the going gets tough.

Consider:

Climate / Environment

Resources

Geography

When James Cameron wrote the movie Avatar, he created countless reference books on Pandora’s vegetation and climate and even botany.

In Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, the main characters live in a post-apocalyptic world covered in ash and largely devoid of life. Their entire journey revolves around finding food and water and how to stay warm.

In A Game of Thrones, George R.R. Martin went as far as creating maps.

Other stories that feature maps:

The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis

Discworld by Terry Pratchett

The Princess Bride by William Goldman

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

Winnie the Pooh by A.A. Milne

A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin

World Building Questions:

Was your world always the way it is now? If not, what was it like before and what caused the change?

How much of your world do you need to show to support the story?

How does the terrain influence your story?

What is the weather like and does it impact your story?

How many mountains, oceans, deserts, forests?

Where are the borders?

What are the natural resources and how do they impact your story?

Be sure to focus on all five senses, not just seeing and hearing. Touch, taste, and smell will make your world feel real and familiar, even if it’s fantasy.

Step 3: Populate Your World

Are the inhabitants people, but somehow different from you and me?

Are they aliens, monsters, or some new species?

In The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien gave Frodo a past, personality traits, and morals. But he first determined what a hobbit looked like and how he lived.

World Building Character Questions:

How big is their population (i.e., how big is your world)?

How did they become part of your world (their backstory )?

Do they have a class system?

What are the genders, races, and species?

Does everyone speak the same language?

How do they get along?

Are there alliances?

What resources do they enjoy?

What resources do they lack?

Step 4: Establish the History of Your World

The Lord of The Rings focuses on an ancient war.

The Hunger Games is built on decades of oppression.

The Divergent trilogy characters are unaware of what their world used to be like.

When world building, consider:

The Deep Past: What happened to fuel the present economy, environment, culture, etc.

Trauma: Wars, famines, plagues.

Power Shifts: Political, religious, or technological.

World Building Questions:

Who have been the major rulers?

What took place during their reigns?

Who are the enemies of your world?

Step 5: Determine the Culture of Your World

Religion

Society

Politics

In Star Wars, for instance, religion (The Jedi vs. The Dark Side), societal structure (slaves and free), and politics (the trade wars) play huge roles.

World Building Questions:

Is your world totalitarian, authoritarian, or democratic?

Do your inhabitants speak a common language?

How do your characters behave? Will they break the rules?

Are the rules considered fair, or is society opposed to them?

How are inhabitants punished?

What is the religious belief system?

What gods exist?

How do religious rituals or customs manifest themselves?

Is there conflict between religious groups?

How do different social classes behave?

What do they wear?

How do families, marriages, and other relationships operate?

How do inhabitants respond to love and loss?

What behaviors are forbidden?

How are gender roles defined?

What defines their success and failure?

What and how do they celebrate?

Do they work?

Step 6: Power Your World

Is your world energized by equipment or magic?

Equipment involves technology like Artificial Intelligence, space or time travel, or futuristic weaponry.

Or it could focus on simpler technology like swords, guns, or horses.

Magic allows you to take your worldbuilding to new realms.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, Arthur C. Clarke explained how things worked and why, making it as realistic and factual as possible.

When writing his futuristic novels, Iain M. Banks referenced droids and spaceships but never explained how they worked.

The same applies to magic in your story.

You can either explain how it all works or simply focus on how it is used and why.

World Building Questions:

Does magic exist in your world?

How powerful is it?

Where does it come from?

How does it manifest itself?

Can it be controlled?

Who wields it?

Can it be learned or are people born with it?

Are wands or staffs, etc., needed?

How does it affect the user?

Do people fear it or embrace it, and what makes the difference?

Is there good and evil magic?

What other technologies do people use?

Who controls it?

How do they travel and communicate?

How do they use these technologies day-to-day?

Do they use technology for entertainment?

Do governments use it to gain or maintain power?

In Fantastic Beasts, J.K. Rowling wrote a guide that focuses on how the magic works.

If magic or futuristic technology play roles in your world, consider doing the same.

It doesn’t have to be as detailed or as complete as Fantastic Beasts. So long as you have a resource that keeps all the rules in one place, you’ll keep your world (and the rules it lives by) consistent.

Write Attention-Grabbing Fiction

No two writers will approach world building the same. Just be careful not to get so bogged down in world building that it keeps you from writing your story.

Have fun with it!

Write a story that keeps your readers riveted to the end.

Need help writing your novel? Click here to download my ultimate 12-step guide.

The post A Step-by-Step Guide to Immersive World Building appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

August 23, 2021

6 Best Practices for Writing Creative Nonfiction

People browsing books usually scan the cover for the title, author, and whoever wrote the foreword. Then they glance at the back cover.

If intrigued, they’ll turn to the first chapter.

Your first paragraph—from the first sentence—must compel your reader to continue.

The power of creative nonfiction comes from using a technique common in fiction—rendering a visual to trigger the theater of the readers’ minds.

Certain stories should be told exactly as they happened. Take it from a novelist who also writes nonfiction: You don’t have to resort to fiction to captivate readers. Creative nonfiction is often the best way to go.

What is Creative Nonfiction?

Also referred to as literary or narrative nonfiction (and sometimes literary journalism), the term can be confusing. “Creative” is usually associated with make-believe. So can nonfiction be creative?

It not only can, but should be to gain the attention of an agent or publisher—and ultimately your readership.

Unlike academic and technical writing (and even objective journalism), creative nonfiction uses many of the techniques and devices employed in fiction to tell a compelling true story. The goal is the same as in fiction: a story well told.

Some nonfiction narratives carry a literary flair every bit as beautiful as classic novels.

My very favorite book ever, Rick Bragg’s memoir All Over but the Shoutin’, won rave reviews all over the country. Bragg’s haunting, poetic prose was a byproduct of the point of his book, not the reason for it.

The Best Creative Nonfiction Writers Are…1. Avid readers.

Writers are readers. Good writers are good readers. Great writers are great readers.

Read everything you can find in your genre before trying to write in it.

You’ll quickly learn the conventions and expectations, what works and what doesn’t.

2. Focused on the heart, but not preachy.Creative nonfiction consists of an emotionally powerful message that moves readers, potentially changing their lives. But don’t preach. True art gives your reader credit for getting the point.

Readers love to be educated and entertained, but move them emotionally and they’ll never forget it.

3. Precise.Employing fictional literary tools doesn’t mean being loose with the facts. Become an avid researcher.

Your story should be:

FactualRelevantInterestingAre you being objective or spinning your own angle?

Your research should contribute to real stories well told.

Remember to use your research to season your main course—the point of your book. Resist the urge to show off all you learned with an information dump.

4. Rule followers.Writing a story is like building a house—if the foundation’s not solid, even the most beautiful structure won’t stand.

Experts agree that these 7 elements must exist in a story (follow the links to study further).

ThemeCharactersSettingPoint of ViewPlotConflictResolution5. Not afraid to get personal.Include your unique voice and perspective, even if the book or story is not about you.

6. Creative (pun intended).Readers bore quickly, so don’t just review a Chinese restaurant—explain how they get that fortune inside the cookie without getting it soggy.

Don’t just write a standard business piece on a store. Profile one of its most loyal customers.

ExamplesAutobiography: First We Have Coffee by Margaret Jensen, Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain, The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank, The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

Biography: A Passion for the Impossible by Miriam Huffman Rockness, Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson, John Adams by David McCullough, Churchill: A Life by Martin Gilbert, Son of the Wilderness: The Life of John Muir by Linnie Marsh Wolfe

Memoir: All Over but the Shoutin’ by Rick Bragg, Cultivate by Lara Casey, A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway, Out of Africa by Karen Blixen, Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt

How-to: Reconcilable Differences by Jim Talley, the …For Dummies guides, The Magical Power of Tidying Up by Marie Kondo, Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott, The 4-Hour Work Week by Tim Ferris

Motivational: The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey, The War of Art by Steven Pressfield, Think and Grow Rich by Napoleon Hill, The Seven Decisions by Andy Andrews, Intentional Living by John Maxwell

Christian Living: Chasing God by Angie Smith, The Search for Significance by Robert McGee, The 5 Love Languages: The Secret to Love That Lasts by Gary Chapman, Boundaries by John Townsend, Love Does by Bob Goff

Children’s Books: Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson, The Right Word: Roget and His Thesaurus by Jen Bryant, My Brother’s Book by Maurice Sendak

Inspirational: Joni by Joni Eareckson Tada with Joe Musser, Wild by Cheryl Strayed, The Hiding Place by Corrie ten Boom with John and Elizabeth Sherrill, Undone: A Story of Making Peace with an Unexpected Life by Michele Cushatt, You’ve Gotta Keep Dancin’ by Tim Hansel

Expository: Mere Christianity by C. S. Lewis, Desiring God by John Piper, Breaker Boys: How a Photograph Helped End Child Labor by Michael Burgan, Who Was First? Discovering the Americas by Russell Freedman, The Pursuit of God by A.W. Tozer

Time to Get to Work

Few pleasures in life compare to getting lost in a great story. The stories we tell can live for years in the hearts of readers.

Do you have an idea, an insight, a challenge, or an experience you long to share?

Don’t let it rest just because of all the work it takes. If it was easy, anybody could do it.

Master the best practices I’ve shared above so you can do justice to the important stories you have to tell.

For additional help writing creative nonfiction:

How to Write Your Memoir: A 5-Step Guide and How to Start Writing Your MemoirHow to Write an Anecdote and Why Stories Bring Your Nonfiction to LifeHow to Write a Devotional: The Definitive GuideHow to Edit a Book: 7 Steps for Becoming a Ferocious Self EditorThe post 6 Best Practices for Writing Creative Nonfiction appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

August 9, 2021

How to Outline a Nonfiction Book in 5 Steps

There’s no way around it. You need a book outline if you’re writing nonfiction.

For a novel, if you’re a Pantser (one who writes by the seat of your pants—like I do) as opposed to an Outliner, you can get away with having a rough idea where you’re going and how to get there.

But for nonfiction, a book outline is non-negotiable.

Potential agents and publishers’ acquisitions editors require it in a proposal. They want to know you know where you’re going, chapter by chapter.

Over the past nearly 50 years, I’ve written 200 books, 21 of them New York Times bestsellers—a third of them nonfiction. I’ve come to appreciate the discipline of outlining, though that doesn’t work for me with fiction.

I’ve developed an easy-to-use book outline process I believe will help you organize your manuscript.

But first, a word about your topic…

Don’t make the mistake of trying to make a book of something that could—and should—be covered in an article or blog post.

You need a topic worthy of a book. Can it bear at least 12 chapters?

What is a Book Outline?If you’ve forgotten the basics of classic outlining or have never felt comfortable with the concept, you can still manage this. Your book outline must serve you, not the other way around.

You don’t have to think in terms of 20+ pages of Roman numerals and capital and lowercase letters followed by Arabic numerals—unless that best serves your project. For me a bullet point list of sentences that synopsize my idea works fine.

Don’t even call it an outline if that offends your sensibilities. But fashion some sort of a document that provides direction and structure—which will also serve as a safety net to keep you on track.

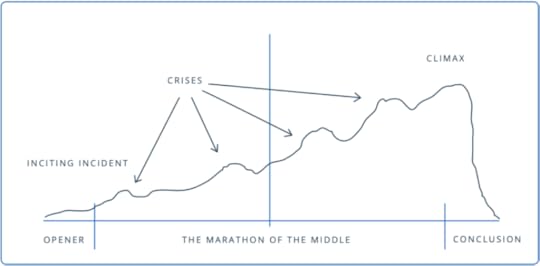

A Winning Strategy for Outlining a BookIf you lose interest in your manuscript somewhere in what I call the Marathon of the Middle, you likely didn’t begin with enough ideas. A book outline will reveal such a weakness in advance. You want confidence your structure will carry you through to the end.

I recommend the novel structure illustration below for fiction, but with only slight adaptations it can work for nonfiction as well.

The same structure can turn mediocre nonfiction to something special. Arrange your points and evidence to set up a huge payoff, then make sure to deliver.

If you’re writing a memoir, an autobiography, or a biography, you or your biographical subject becomes the main character. Craft a sequence of life events like a novel, and watch the true story come to life.

But even if you’re writing a straightforward how-to or self-help book, stay as close to this structure as possible.

Make promises early, triggering readers to anticipate fresh ideas, secrets, inside information—something major that will thrill them with the finished product.

While you may not have as much action or dialogue or character development as your novelist counterpart, your crises and tension can come from showing where people have failed before and how you’re going to ensure your readers will succeed.

You can even make a how-to project look impossible until you pay off that setup with your unique solution.

How to Outline a Book in 5 StepsAlways view your outline as fluid. You can expand or condense it as you go, and of course move things around.

Your outline should answer:

What’s my ultimate goal—my message?About what am I trying to convince, inform, educate, entertain, or move my readership?What progression sequence, chapter by chapter, best serves my purpose?Begin with a one-page road map that gives you a bird’s eye view of what you intend your book to become.

What to include:

1. Your Message in One SentenceThis can also serve as your Elevator Pitch—what you’d share with a publishing professional between the time you meet him on the elevator and the time he gets off.

Think big. This is not your book, but the idea behind it.

What message can you communicate with the potential to change lives? It should be one you’re passionate about, because it changed your life.

People love to be educated and entertained, but they never forget if you move them emotionally.

I wrote As You Leave Home: Parting Thoughts from a Loving Parent to our eldest son when he left home for college.

My elevator pitch: “I want to express my unconditional love for my child as he leaves the nest.”

Gift books for grads are a dime a dozen, so what made mine stand out and be excerpted in the in-flight magazines of United and American Airlines, and land a guest spot on James Dobson’s Focus on the Family radio program?

Why did this book resonate with tens of thousands of parents facing the same season?

The emotional nature of the message.

By declaring my love for my son, I connected with the hearts of parents during this same bittersweet season.

Without contriving, by letting it bubble up through true passion, aim for the heart.

2. Your Target ReadershipResist the temptation to say it’s for everyone. We all like to think our message is for both genders and all ages, but that’s unrealistic and viewed as naïve by agents and publishers.

Three of the bestselling nonfiction books of all time eventually landed in the everyone category but were originally aimed at specific readerships:

How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie, released in 1936, has sold more than 30 million copies and still sells roughly a quarter million a year. Target: business people.The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen R. Covey, released in 1989, and has sold more than 25 million copies in 40 languages. Target: business people.Written as the sequel to The Purpose Driven Church, The Purpose Driven Life by Rick Warren, released in 2002, has sold more than 50 million copies in 85 languages. Target: adult Christians.One way to determine your target readership is to imagine a single reader.

What’s their problem (felt need)?What takeaway value can you offer?What’s the most compelling approach you can use to reach them?I used to imagine my mother as my target reader when she was in the demographic most likely to buy inspirational books. If I could make sense to her, I’d hit the mark.

If you’re still fuzzy on your readership, look in the mirror. Write the book you’d read.

And, be specific. If your book is about your life as a veterinary surgeon, its primary target would be aspiring vets, then practicing vets, and finally animal lovers.

Research the numbers of people who populate these categories so you can give agents and publishers an idea of the potential market.

3. How You’ll Convey Your Message

Imagine you’ve confided to two friends about a personal problem.

The first says, “Here’s what you need to do…”

The second drapes an arm around your shoulder and says, “I was in your place once. Let me tell you what I learned and how I got out of it.”

Which are you more likely to listen to?

I call that second approach the Come-Alongside Method. It avoids preachiness and allows readers to get and apply the point on their own.

A story well told drives home a point much more powerfully than narrative summary.

Think reader first.

4. A One-Sentence Synopsis of Each ChapterThink in stages, so your chapters flow logically.

Begin with a promise—a setup you’ll pay off in the end.

For example, with a how-to topic like Time Management, your first few chapters should dangle a carrot, either with a story about a chronic time waster who became a consummate success, or by simply implying, Stick with me and you’ll be a time management pro by the time you finish this book.

Then list chapters that:

cover the background of your topicanalyze current theories and opinionsreview case historiespresent innovations and experimentsfeature interviews with expertsNow summarize your chapters to help divide your research into categories.

Example Chapters:

One: In Time, You Can Be a ProTwo: Time Management Since Bible TimesThree: What the Experts SayFour: Technology and Time Management5. Your Research and Stories

Getting every fact right adds polish to your finished product.

Even a small mistake due to a lack of research can cause your reader to lose confidence—and interest—in your book.

Research TipsEssential tools:

Atlases and World Almanacs to confirm geography and cultural norms.Online Encyclopedias.YouTube and online search engines can yield tens of thousands of results. (Just be careful to avoid getting drawn into endless clickbait videos)A Thesaurus, but not to find the most exotic word. Look for that normal word on the tip of your tongue.In-person, online, or even email interviews with experts. People love to talk about their work, and often such lead to more anecdotes to support your message.When choosing anecdotes, remember:

A memoir, autobiography, or biography doesn’t need to be in chronological order. Sequence your stories to best serve your theme.For how-to and self-help, include only stories that support your points.Readers love stories.

If you don’t have a story to support a point, get creative! Feel free to invent stories, but always clearly differentiate between which are true and which are imagined.

If you begin a story, “A friend of mine…,” the reader will assume it’s true.

If you begin with something like, “Consider a mother of preschoolers…,” the reader understands you’re suggesting a scenario.

Now expand each chapter summary into a synopsis of a few sentences.

Under each, list the stories you’ll use and tell how each supports your theme and message

Next, for self-help, psychology, business, or other non-character driven nonfiction books: examine the primary message of each chapter. Note whether it meets the needs of your readers.

For chapters in memoirs, biographies, historical fiction, or any other character-driven nonfiction, examine:

Your POV characterWhat’s happeningWhen it’s happeningWhere it’s happeningIts contribution to your main character’s terrible troubleYou Can Do ItOutlining a book is crucial to your success. Carefully follow the steps above to give you the structure you need to write the nonfiction book you’ve always dreamed of writing.

Click here for additional resources, like help with writing your memoir, a devotional, or my start-to-finish book writing process.

The post How to Outline a Nonfiction Book in 5 Steps appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

August 3, 2021

How to Start a Story: 5 Proven Strategies and Why They Matter

Acquisitions editors and agents reject some manuscripts within the first page or two.

That doesn’t sound fair—and maybe it isn’t—but that’s the reality we writers face.

Even if you’re self-publishing and avoiding the harsh glare of professional eyes, you must rivet your readers from the get-go or most will close your book without a second thought.

Novelist Les Edgerton started a short story this way:

He was so mean that wherever he was standing became the bad part of town.

I’d keep reading, wouldn’t you?

If you’re stuck on how to start a story, you’re not alone.

Settling on a compelling opener is critical to the success of the rest—whether you’re writing a short story or a novel, your first sentence will be the most important. If it fails, readers stop reading.

How to Start a Story

As a novelist, you owe your reader certain things from page one.

By investing in your novel, your reader tacitly agrees to willingly suspend disbelief and trust you to provide entertainment, inspiration, or education—sometimes all three.

In exchange, the reader expects to be given credit for having a brain, not spoon fed. They want to participate in the experience. Set the tone of your novel early.

Whether your opening scene is funny or serious, the rest should follow suit.

The first few paragraphs serve as your calling card not only to readers but also to the potential agents or acquisitions editors who precede them.

To help you develop a strong beginning and get out of the way so your readers can, as Canadian author Lisa Moore puts it, begin to create your story in their head:

1. Begin in medias res.That’s Latin for “in the midst of things.” It doesn’t have to be slam-bang action, unless that fits your genre. But start with something happening. Give the reader the sense he’s in the middle of something.

Don’t waste your opener (the highest price real estate in your manuscript) on backstory or setting or description. Layer these in as the story progresses. Get to the good stuff—the guts of your story—and trust your reader to deduce what’s going on.

The goal of every sentence, in fact of every word, is to get force the reader to read the next.

2. Introduce your main character early.One of the biggest mistakes you can make is to introduce your main character too late. ()

As a rule, he* should be the first person on stage.

[*I use he inclusively to refer to both genders.]

Naming your character can be almost as stressful as naming a newborn, so take the time you need to get it right. Make it interesting and memorable, but not quirky or outrageous.

Search online for baby names by ethnicity and sex. Consult World Almanacs for foreign names. Be sure they’re historically and geographically accurate. You wouldn’t have characters named Jaxon and Brandi, for instance, in a story set in Elizabethan England.

Work in just enough detail to get readers to care what happens to him. Is he a spouse, a parent, troubled, worried, hopeful? Then get to the problem, the quest, the challenge, the danger—whatever drives your story.

3. Don’t describe; layer in.Agents and editors say a common mistake in beginners’ manuscripts is starting a story by describing the setting.

Don’t get me wrong—setting is important. But we’ve all been put to sleep by an opening scene that began something like:

The house sat in a deep wood surrounded by…

Don’t.

Rather than employing description as a separate element, layer it in as part of your story. That way the reader subconsciously becomes aware of it while you’re focusing on the plot itself—what’s happening.

For example, instead of:

The house sat in a deep wood surrounded by… (Description as a separate element.)

Try this:

Wondering what could be so urgent that he had to meet Tim in the middle of the night, Fred pulled deep into the woods on an unpaved road and came upon… (Layering in the details.)

4. Show, Don’t TellWhen you tell rather than show, you simply inform your reader of information rather than allowing him to deduce anything.

You’re supplying information by simply stating it. You might report that a character is “tall,” or “angry,” or “cold,” or “tired.”

That’s telling.

Showing paints a picture readers see in their minds’ eyes.

Telling: She could tell he had been smoking and that he was scared.

Showing: She wrapped her arms around him and smelled tobacco. He shivered.

Layered in as part of the action, what things look and feel and smell and sound like register in the theater of your readers’ minds, while they’re concentrating on the action, the dialogue, the tension and drama and conflict that keeps them turning those pages.

That way, you can subtly work in all the details they need to get the full picture and enjoy the experience from the first sentence.

5. Find your writing voice.

This isn’t as complicated as it sounds.

Put simply, your writing voice is you.

It reveals your:

PersonalityCharacterPassionEmotionPurposeImagine saying to your best friend, “Have I got something to tell you…”

What comes next will likely be in your most passionate voice.

You at your most engaged is the voice you want on the page.

That’s what your writing voice should sound like.

To use it in fiction, give that voice to your perspective character.

Remember, the goal of your opener is to leave your reader with no choice but to turn the page.

Need help writing your novel? Click here to download my 12-step guide to writing a novel.

4 Ways to Start a StoryLearn from those who’ve done it successfully. Examples:

1. Surprise“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” —Gabriel Garcia Marquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967)

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” —George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

“It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not.” —Paul Auster, City of Glass (1985)

“It was the day my grandmother exploded.” —Iain M. Banks, The Crow Road (1992)

“High, high above the North Pole, on the first day of 1969, two professors of English Literature approached each other at a combined velocity of 1200 miles per hour.” —David Lodge, Changing Places (1975)

“A screaming comes across the sky.” —Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow (1973)

“It was a pleasure to burn.” —Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451 (1953)

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.” —Franz Kafka, The Metamorphosis (1915)

“I write this sitting in the kitchen sink.” —Dodie Smith, I Capture the Castle (1948)

“Marley was dead, to begin with.” —Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol (1843)

2. Dramatic Statement“Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins.” —Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita (1955)

“I am an invisible man.” —Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952)

“He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty-four days now without taking a fish.” —Ernest Hemingway, The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

“Someone must have slandered Josef K., for one morning, without having done anything truly wrong, he was arrested.” —Franz Kafka, The Trial (1925)

“They shoot the white girl first.” —Toni Morrison, Paradise (1998)

“You better not never tell nobody but God.” —Alice Walker, The Color Purple (1982)

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” —Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice (1813)

3. Philosophical

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” —Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina (1877)

“This is the saddest story I have ever heard.” —Ford Madox Ford, The Good Soldier (1915)

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” —L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between (1953)

“Of all the things that drive men to sea, the most common disaster, I’ve come to learn, is women.” —Charles Johnson, Middle Passage (1990)

“Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.” —Charles Dickens, David Copperfield (1850)

“Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board.” —Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937)

“No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own; that as men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinised and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water.” —H.G. Wells, The War of the Worlds (1898)

4. Poetic“When I finally caught up with Abraham Trahearne, he was drinking beer with an alcoholic bulldog named Fireball Roberts in a ramshackle joint just outside of Sonoma, California, drinking the heart right out of a fine spring afternoon.” —James Crumley, The Last Good Kiss (1978)

“It was just noon that Sunday morning when the sheriff reached the jail with Lucas Beauchamp though the whole town (the whole county too for that matter) had known since the night before that Lucas had killed a white man.” —William Faulkner, Intruder in the Dust (1948)

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.” —Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

“In certain latitudes there comes a span of time approaching and following the summer solstice, some weeks in all, when the twilights turn long and blue.” —Joan Didion, Blue Nights (2011)

“Francis Marion Tarwater’s uncle had been dead for only half a day when the boy got too drunk to finish digging his grave and a Negro named Buford Munson, who had come to get a jug filled, had to finish it and drag the body from the breakfast table where it was still sitting and bury it in a decent and Christian way, with the sign of its Saviour at the head of the grave and enough dirt on top to keep the dogs from digging it up.” —Flannery O’Connor, The Violent Bear it Away (1960)

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.” —J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit (1937)

Writing a Great Opening Line Is Only the BeginningFew pleasures in life compare to getting lost in a great story.

The story worlds you and I create and the characters we birth can live in the hearts of readers for years.

It begins with writing an opener so compelling they can’t help but continue turning the pages.

The post How to Start a Story: 5 Proven Strategies and Why They Matter appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

July 23, 2021

Dynamic and Static Characters: The Difference and Why it Matters

Guest Post by Tami Nantz

Memorable, believable characters are crucial to every good story.

Consider what makes these literary classics so unforgettable:

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

Each has a cast of flawed characters whose growth—their character arcs—makes all the difference.

Two essential types of characters exist in a story: dynamic and static. Understanding them can help you compel readers to keep turning the pages.

What is a Dynamic Character?

One who, because of the internal and external obstacles he faces, and the lessons he learns, experiences significant change by the end of a story.

The more challenges, the better the story. The toughest challenges beget the most radical transformations.

Lead characters are usually dynamic, but not always.

Dynamic Character Examples:Katniss Everdeen: She begins The Hunger Games trying to feed and protect her family following the death of her father.

But when Prim, her sister, is selected as Tribute for District 12, Katniss knows she won’t survive, so she volunteers to take her place alongside the baker’s son Peeta, the chosen male Tribute.

Peeta has had a crush on Katniss since childhood, but does Katniss feel the same way, or does she merely pretend for strategic reasons?

As Katniss and Peeta fight to survive, the twists and turns of the game keep readers wondering if either will. In the end, Katniss becomes a hero who inspires hope (and a rebellion) in her countrymen.

Ebenezer Scrooge: He begins A Christmas Carol selfish, miserly, and miserable, an old man who seems to despise anything good, even carolers trying to spread cheer on Christmas Eve.

But that very night he’s visited by the ghost of his former business partner and then the ghosts of Christmas past, present, and future. He watches as not a single soul cares enough about him to mourn his death.

In the end, he becomes a generous, gracious, kindhearted gentleman bent on keeping the Christmas Spirit alive for the rest of his life.

Walter White: The main character in the hit AMC series Breaking Bad begins as a high school science teacher who learns he has cancer. His insurance company refuses to cover all his treatments, putting him on the verge of bankruptcy.

He’s already working two jobs and has taken out a second mortgage on his home. A ride-along on a drug bust with his DEA brother-in-law gives Walter an idea: he could use his scientific knowledge to develop quality meth and make a bundle.

A chance encounter with a former student results in an unlikely partnership, and so begins the secret life of Walter White. Not only is he able to quickly meet the financial needs of his family, but his drug business also becomes so lucrative it ultimately destroys everyone involved.

The opposite character arc from Scrooge, for example, White has gone from high school teacher to drug lord.

Dynamic vs. Static CharactersStatic characters often get a bad rap, but that’s not always deserved.

While dynamic characters experience life-altering changes, the personalities, behaviors, and morals of static characters remain largely unchanged.

But that doesn’t have to mean they’re boring. It just means they don’t experience a major internal transformation like dynamic characters do.

Static Character Examples:James Bond: In his 12-novel series, Ian Fleming created the perfect static character. Though he’s a charming, sophisticated, dangerous British Secret Service Agent who fights crime, he personally remains unchanged.

Smaug: The deadly, fire breathing dragon who captures Erebor in The Hobbit, sits atop a golden treasure he’ll protect at any cost.

When Bilbo steals a chalice, Smaug wakes and fights, which results in his ultimate downfall. His character remains unchanged throughout.

Albus Dumbledore: For most of the Harry Potter series, Dumbledore is seen as the beloved grandfatherly Headmaster at Hogwarts.

We readers grow fond of him too, as we learn his backstory, but his character remains unchanged during the series.

Only after his death do we learn more about his sins and virtues, and that he never fully rid himself of the dark side he hid so well.

How to Create a Dynamic Character1. Give him a history.Your character’s history—his backstory—shaped him into the person he is today.

The more thoroughly you know him, the easier it’ll be to determine where change can occur during your story.

Things you should know, whether or not you choose to include them:

When and where was he born?Who are his parents?Does he have brothers and sisters (include names and ages)?Did he attend high school? College? Graduate school? Where and for how long?What’s his political affiliation?What’s his occupation?How much does he make?What are his goals?What are his skills and talents?What does his spiritual life look like?Who are his friends?Who is his best friend?Is he single? Dating? Married?What’s his worldview?What’s his personality type?What triggers his anger?What gives him joy?What’s he afraid of?2. Give him human qualities.To be human is to be flawed and vulnerable.

Even superheroes have weaknesses. Superman’s is Kryptonite. Daredevil’s is a high-pitched sound. Thor is stronger when he has his hammer. The Green Lantern can stop just about anything unless it’s made of wood.

If you want readers to identify with dynamic characters, those characters must have human weaknesses and vulnerabilities.

Just make sure those faults aren’t irreparable—don’t make your protagonist a fearful, wimpy slob who can do nothing right.

3. Give him heroic qualities, too.Plunge him into terrible trouble and allow him to learn valuable lessons as he tries (and fails) to fight his way out. But eventually allow him to show readers what he’s made of.

Have him develop courage and conviction. Make him grow strong, selfless, honest, and determined. Give him moral integrity.

Maybe he begins as the underdog deathly afraid of spiders or heights, or has an unhealthy addiction. But in the end, he must rise above his flaws, overcome the challenge, and become the hero who keeps readers turning the pages

4. Make sure there’s internal and external conflict.

Conflict is the engine of fiction—and that’s usually external.

But what happens to your character internally is also important. What your hero thinks, feels, and tells himself directly influences his eventual transformation.

Draw upon your own experience to create a whole character, inside and out.

What are your innermost doubts and fears? How do you respond to danger?

Mix and match behaviors from yourself and others to determine your hero’s natural internal and external responses.

5. Show, don’t tell.Like Jerry always says, this is the cardinal rule of fiction.

Show readers who your character is through his thoughts, actions, and dialogue. Then trust readers enough to let them deduce the rest.

That gives readers the best reading experience.

Start Developing Dynamic CharactersPositive growth or not, a dynamic character always changes over the course of a story.

Explore dynamic characters in stories you read to learn what makes them work, and how you can do it.

Develop dynamic characters who feel real, and they’ll become unforgettable.

For additional help developing your characters, visit:

Your Ultimate Guide to Character Development: 9 Steps to Creating Memorable HeroesInternal and External Conflict: Tips for Creating Unforgettable CharactersHow to Create a Powerful Character ArcCharacter Motivation: How to Craft Realistic Characters12 Character Archetypes You Can Use to Create Heroes Your Reader Will LoveThe post Dynamic and Static Characters: The Difference and Why it Matters appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

July 8, 2021

How to Edit a Book: 7 Steps For Becoming a Ferocious Self-Editor

So you want to get published?

To give yourself the best chance, you need to learn how to edit your manuscript so a publisher will want to turn it into a book.

Whether you want to self-publish or land a traditional publishing deal (where they take all the financial risk and pay you, rather than the other way around), your manuscript must be the best it can be.

With self-publishing, anyone can get anything printed or turned into an ebook.

It doesn’t even have to be good. If you have the money, someone will print whatever you submit. Or you can create an ebook by simply uploading your manuscript to Amazon and other online stores.

But you’re not likely to impress readers if your book is full of typos or lacks proper formatting.

Admittedly, the odds of landing a traditional publishing contract are slim.

So you must separate yourself from the competition by ensuring your manuscript is the best you can imagine.

Yes, a traditional publisher will have its own editors and proofreaders. But to get that far, your manuscript has to be better than about a thousand other submissions.

And if you’re self-publishing, the way to stand out is by ferociously editing your manuscript until it’s as crisp and clean as possible and you’re happy with every word.

There’s little worse than a self-published book that looks like one.

Learning to Ferociously Self-Edit

Whether you’re going to hire an editor, or be assigned one by a traditional publisher, your responsibility is to get your book manuscript to the highest level it can be before you pass it on.

Never settle for, “That’s the best I can do; now fix it for me.”

Why?

Because sadly, if you attempt the traditional publishing route, you could pour your whole life into a manuscript and get just five minutes of an editor’s time before your book is rejected.

Sounds unfair, doesn’t it?

But as one who has been on both sides of the desk for more half a century, let me tell you there are reasons for it:

Why Agents and Publishers Reject Some Manuscripts After Just Two PagesProfessionals can tell within a page or two how much editing would be required to make a manuscript publishable; if it would take a lot of work in every sentence, the labor cost alone would disqualify it.

They’ll consider:

Does the writer grab readers by the throat from the get-go?Have too many characters been introduced too quickly?Does the writer understand point of view?Are the setting and tone compelling?Is there too much throat clearing (explanation below)?Is the story subtle and evocative, or is it on-the-nose (also clarified below)?Yes, an agent or acquisitions editor often determines all this with a read of the first two to three pages.

If you’re thinking, But they didn’t even get to the good stuff, put the good stuff earlier in your manuscript.

So today, I want to zero in on tight writing and self-editing.

Author Francine Prose says:

For any writer, the ability to look at a sentence and see what’s superfluous, what can be altered, revised, expanded, or especially cut, is essential. It’s satisfying to see that sentence shrink, snap into place, and ultimately emerge in a more polished form: clear, economical, sharp.

Seven Steps to Self-Editing Your Book Manuscript Click here to download your copy of the ultimate self-editing checklist. Step 1. First, Separate Writing From RevisingI start every writing day by first conducting a heavy edit and rewrite of what I wrote the day before. Don’t try to edit as you write. That’s likely to slow you to a crawl.

Why?

Because rough draft writing is vastly different from revising. The latter accommodates our perfectionist tendencies. Writing needs to be done with our perfectionist caps off.

Step 2. Read Through Your ManuscriptFor best results, read it out loud.

Have a notebook (or blank document) open to make notes as you spot pacing or character development issues, or even easily fixable issues like that are too similar.

Step 3. Start With the Big PictureThe editing process begins with big picture edits: major changes, like moving scenes, removing characters, or even changing the plot.

As you begin to self-edit:

Make sure you’ve introduced your main character early.Ensure the reader understands what motivates your characters (including the villain)—both internally and externally, their goals, strengths, and weaknesses.Remove scenes (or even chapters) that don’t move the story along.Fix issues with the plot of your story, like gaps or inconsistencies. If you’re a Pantser, pay particular attention to the logic of your plot.Be sure the structure of your story works.Ensure you’ve established character empathy for your hero and supporting cast. You even want some degree of reader empathy for your villain.Ensure your hero’s growth (character arc) is clear.Rework any scenes that seem rushed—and trim scenes that drag.Remember that conflict is the engine of fiction—both internal and external conflict.Make sure each scene is told from a single point of view. Failing is a mistake made by too many beginning writers. You can switch between points of view (multiple main characters), but never within the same scene.Conduct further research if necessary to strengthen your plot or make your novel more believable.Step 4. Hone Each SceneAt this stage of editing a manuscript, you should be confident that each scene develops your story or reveals character.

As you refine each scene:

Avoid throat-clearing—a literary term for a story or chapter that finally begins after a page or two of scene setting and background. Get on with it.Avoid too much stage direction. You don’t need to tell every action of every character in each scene, what they’re doing with each hand, etc.Avoid cliches. This doesn’t just apply to words and phrases. There are also clichéd situations, like starting your story with the main character waking to an alarm clock; having a character describe herself while looking in a full-length mirror; having future love interests literally bump into each other upon first meeting, etc.Use specifics. They add the ring of truth (even to fiction). Not tree, but oak. Not bird, but magpie.Avoid telling what’s not happening, like “He didn’t respond,” “She didn’t say anything,” or “The crowded room never got quiet.” If you don’t say these things happened, the reader will assume they didn’t.Give the reader credit. Example: “They walked through the open door and sat down across from each other in chairs.” If they walked in and sat, we can assume the door was open, the direction was down, and—unless told otherwise—there were chairs. Instead, try: “They walked in and sat across from each other.”Resist the urge to explain. Marian was mad. She pounded the table. “George, you’re going to drive me crazy,” she said, angrily. We don’t need to be told Marian was mad, or that she spoke angrily. It’s clear how she feels from her pounding the table and from the words she chooses.Show, don’t tell. As above, don’t tell us “Marian was mad.” Show us through her actions.Cut on-the-nose writing—a Hollywood term for writing that mirrors real life but fails to propel the story. Don’t distract the reader with minutia; stick to what matters.Avoid passive voice. Eliminate as many state-of-being verbs as possible to make your writing more powerful.Make sure your dialogue provides information, advances the plot, or reveals character. If it doesn’t, cut it.Step 5. Root Out Weasel or Crutch Words

Words and phrases you overuse weaken your sentences and distract readers. You might already be aware of some of yours.

For instance, maybe you describe eyes as sparkling more than once, or you use really or very a lot. Watch out for these as you self-edit your book.

As you root out such words:

Choose the normal word over the obtuse. When you’re tempted to show off your vocabulary or a fancy turn of phrase, think reader-first and keep your content king. Don’t intrude. Get out of the way of your message.Avoid the words up and down…unless they’re really needed. They can be cut from sentences like “He rigged [up] the device” and “She sat [down] on the couch.”Usually, delete the word that. Use it only for clarity. “I told Joe that he needed to come home” is stronger as “I told Joe he needed to come home.”Avoid hedging verbs like smiled slightly, almost laughed, frowned a bit, etc.Refrain from using literally when you mean figuratively. “My eyes literally fell out of my head.” There’s a story I’d like to read.Avoid mannerisms of attribution. People say things; they don’t wheeze, gasp, sigh, laugh, grunt, snort, reply, retort, exclaim, or declare them. Such descriptors distract from the dialogue.Where appropriate, drop the attribution and use actions instead. Jim sighed. “I just can’t take any more.” This doesn’t need a he said at the end: we know it’s Jim speaking from the action preceding the dialogue.Step 6. Conduct a Final Run-ThoroughThe final revision stage checks every word to be sure it’s as strong as possible. Also watch for typos or grammatical errors. Writing and editing tools like ProWritingAid can help.

When you copy edit:

Avoid mannerisms of punctuation, typestyles, and sizes. “He…was… DEAD !” doesn’t make a character any more dramatically expired than “He was dead.”Use adjectives sparingly. Good writing is a thing of strong nouns and verbs, not adjectives. Novelist and editor Sol Stein says one plus one equals one-half (1+1=1/2), meaning the power of your words is diminished by not picking just the better one. “He proved a scrappy, active fighter,” is more powerful if you settle on the stronger of those two adjectives. Where possible, use a strong verb in place of an adjective plus a weaker verb.Omit needless words. This should be the hallmark of every writer.Avoid subtle redundancies. “She nodded her head in agreement.” Those last four words could be deleted. What else would she nod but her head? And when she nods, we need not be told she’s in agreement.Read your book aloud to spot sentences that are confusing, too long, or poorly constructed.Look for typos, grammatical errors, and inconsistencies. You may want to keep a running list of how you spell specific words (e.g. ebook, eBook, or e-book).Fix punctuation errors.Remove double spaces at the ends of sentences: yes, you might’ve learned to use them in school, but the modern standard is a single space between sentences.Step 7. Conduct a Final Proofread

During this step, you’re simply checking for things like spelling mistakes, stray punctuation, or misformatted dialogue.

It can be tricky to spot your own mistakes,so you might want to ask someone to help.

Proofreading is particularly vital if you’re self-publishing. You may not notice your mistakes, but readers will.

I’ve added a downloadable self-editing checklist below to help you master these seven steps. The more boxes you can check for your manuscript, the leaner, meaner, and more ready it will be for submission to an agent or publisher.

Click here to download your copy of the ultimate self-editing checklist.The post How to Edit a Book: 7 Steps For Becoming a Ferocious Self-Editor appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

July 1, 2021

A Comprehensive Guide to Creating an Effective Author Website

If you’re an author, published or not, you need your own website. Period.

Why am I so forthright about this? Because of the realities of publishing today.

You’ve heard and read of your need for an author platform—a following, a tribe, visibility. Well, that all starts with having your own author website.

Regardless of what you say about yourself and your work when pitching agents and publishers, one of the first things they do—sometimes even before reading the rest of your proposal—is conduct an internet search for your name.

The first thing that ought to pop up is your author website. Google my name and you’ll be directed to JerryJenkins.com.

In fact, you’d be hard-pressed to Google any published author’s name and not find their author website with a custom domain name (usually, like mine, their own name).

No way around it, an author website is crucial.

The Purpose of an Author WebsiteIt’s where agents, publishers, readers, and fans learn about your work and communicate with you. It gives you:

1. Instant credibility.A professional-looking author website puts your best foot forward and implies you’re a serious professional.

2. A showcase for your work.Once you’re a published author, it’s where you can connect directly with your readers.

3. An opportunity to build a following.This is what publishers and agents look for in potential authors. It’s where you collect email addresses and build a list.

Get your growing audience interacting with you and each other by posing a simple question or taking a brief survey on their favorite things: books, movies, celebrities—you name it.

If the Idea of an Author Website Intimidates YouMaybe, like me, you’re not a techie. Don’t worry. Below are simple instructions to get you started.

1. Choose Your PlatformA website platform is the foundation on which a website is built. It provides the best interactive experience for your readers.

Forty percent of all websites use WordPress, including me. Its user-friendly platform offers a huge variety of themes and allows us laypeople to build a professional looking website quickly and for very little or no cost.

In addition to WordPress, my team also recommends Squarespace, Blogger, or Wix.

2. Select a Domain HostIf even the idea of “hosting” a site sounds foreign to you (it did to me at first), think of the Internet as an apartment complex. Tenants decorate their apartments the way they want—but they don’t own that space. The landlord does.

Landlords own the hardware that makes websites work. These are also called hosting companies, so you rent your online space from them.

Of course, they don’t own your author website. You are responsible for everything posted there. Your hosting company makes sure your website is broadcast on the internet 24/7.

Free hosting is available. Most free host sites require you to either use their address (for example: yourname.wordpress.com or Ilovebooks.wordpress.com) or purchase the domain name from them.

In exchange for using their “free” space, they’ll place ads on your author website. You have little control over what those include.

If you can afford to pay for web hosting, you’ll find companies like GoDaddy, HostGator, and others. I recommend Bluehost. Until you start reaching hundreds of thousands of readers, Bluehost should be all you need.

It broadcasts a website for less than $9 per month and offers a 30-day money-back guarantee.Bluehost customer service is accessible 24/7.And should you choose WordPress, Bluehost has supported that platform for more than 10 years and has in-house WordPress experts.

To get started with Bluehost, click this link.

Full disclosure: I get a commission (at no extra cost to you) if you use that link to sign up for a Bluehost service. But I’d recommend Bluehost regardless.

3. Pick a Domain Name (URL)This is your web address, your URL. (which stands for Universal Resource Locator—I had to look that up). The most economical way to purchase one is through your hosting site. I pay an annual fee to own JerryJenkins.com.

Choosing yours is easier than it sounds—just use the name under which you publish or plan to publish.

I recommend capitalizing each of your names for easier readability, but that’s not mandatory.

If your domain name is already in use, you’ll get a message that says your choice is “not available for registration” or something similar.

You have a couple options:

Choose a different website extension. “.com” is preferred because it’s most common, but “.net” or “.co” work just as wellChoose a new domain nameKeep it simple—“TimothyWoodfordWriting.com” is good; “TimothyWoodfordsGreatWritingWebsite.com” is not. Keep your domain name simple, professional, and clear—not quirky or extravagant.

Other ideas:

[YourName]Author.com[YourName]Writer.com[YourName]Books.com[YourName]Writes.com[YourName]Blog.com4. Add Domain SecurityWhen you purchase a domain name, ICANN requires you to provide your personal contact information, making it publicly available.

When you purchase domain security, a third party becomes the owner, thus protecting your personal information by taking over as landlord.

Bluehost calls it Domain Privacy Protection. It’s included in the Prime Plan at no additional charge. If you opt for the Plus or Basic plans, the fee is well worth the extra 99¢ per month.

Build and Design Your Author Website YourselfAvoid the temptation to settle for one of the quick and easy website designs that look like everyone else’s, giving it a small-time feel. Creating your own great-looking custom site has become easier and cheaper than ever.

If, however, you simply don’t want the hassle, and your budget allows it, hire someone to do it.

Pages to Include on Your WebsiteKeep your menu simple and uncluttered. The last thing you want is to confuse your visitors.

HomeThe homepage is the landing page, the reader’s first impression.

As you choose your design and layout, keep in mind the real estate at the top of your homepage is the most valuable on your entire website.

Most designs include:

A header that identifies you, and offers a tagline that usually appears at the top of every page. My tagline is “New York Times Bestselling Novelist.” Novelist Brandilyn Collins uses Seatbelt Suspense®. Novelist DiAnn Mills uses Expect an adventure.The cover of your most recent book, or the latest work you wish to promote. I offer a link to a free writing assessment to help writers find the guidance they need to begin writing the book they’ve always dreamed of writing.Links to the social media sites you appear on.A unique invitation to connect via email (called a lead magnet), so you can communicate with visitors regularly. I offer a quiz to help writers reveal what’s holding them back. I offer to email free material that will help them grow as a writer.Reader reviews and media coverage.Do not include “Home” as part of your website’s navigation. Since it’s the landing page readers see first, that’s obvious.

Whatever your design, be sure it quickly identifies who you are and what you offer.

AboutThis is one of the highest ranked (and most overlooked) pages on most websites. A reader wouldn’t visit your website if they weren’t curious about you, so use this to get them up to speed.

On my About Jerry page, I begin with a brief bio and immediately focus on engaging my readers and what I offer them. I link to a longer Bio and close with a note about my family and home.

ContactMake it as easy as possible for readers to communicate with you by posting a brief list of reasons they might contact you:

“I’d love to hear your thoughts on…”“If you’re looking for a speaker on…”“If you’re looking for a writer who…”And then, of course, link to your contact information and include an invitation to opt-in to your email list.

Books PageIf you’re a published author, include a list of your book(s).

I mention my bestselling series at the top of my ‘About Jerry’ page, and numerous titles and links to books I’ve written, as well as a link to the complete list on my Biography page.

Wherever you place yours, include:

Your book cover(s)A brief description of the book(s)A link to where your book(s) can be purchasedA link to any other materials you offer, like the introduction or first chapter, FAQs, or a study guide.If you’re unpublished, you could link to any work you’ve published online or describe your work-in-progress.

BlogA blog helps establish your credibility as an expert in your area of expertise.

If you add a blog, don’t make it your homepage. Linking to specific posts that direct them to your blog makes for a less cluttered appearance.

Regularity is more important than quantity. Visitors to your site appreciate knowing when they can expect a new entry.

Make more content visible on your blog page by offering the image, title, and the beginning of your most recent posts.

Because of the variety I offer writers, I include a dropdown menu that categorizes my content.

EventsIf you host book signings or speaking events, post your schedule on this page.

The Fine PrintYour website should include:

A link to your Terms of Service: what happens when you collect an email address, what you’ll send, whether you’ll sell your email list, etc. (here’s mine)A Copyright notificationTrack Your Website’s PerformanceNow what?

How do you know readers are finding your site and reading your content?

Many free tools can tell you everything you need to know.

Google AnalyticsThis is the most in-depth and is used by more than half of all websites.

It’ll help you understand:

Who’s visitingWhere they’re coming from (online source and geographical location)Whether they’re on a mobile or desktop deviceHow many and which pages they’re visitingHow long the visits lastWhich page they visit before they exitHow long the entire visit lastedHow to set it up:

You’ll need a Google account. Then go to Google Analytics and click “Start for Free.”That will lead you to a page that invites you to “start measuring.”Click there and enter the requested information. When finished, click on “Get Tracking ID.”Accept the Terms and Services to obtain a tracking ID, a number that looks like this: UA-123456-7. Beware: this number is unique to the security of your website.Once you have your tracking ID, you’ll be directed to the Admin page where your tracking code will be provided.Copy the tracking code and install it on every page of your website. This will enable Google Analytics to measure and report your activity.Search Engine Optimization (SEO)……is a way to increase traffic to your website and improve your ranking on search engines like Google, Bing,Yahoo, DuckDuckGo, Dogpile, and others.

A tool like this can greatly contribute to your success.

A Google search will yield far more detailed information on SEO than I can provide, but meanwhile, make this incredible tool work for you by: