Jerry B. Jenkins's Blog, page 7

March 3, 2022

Participating in NaNoWriMo This Year? Caution!

The wildly popular phenomenon, National Novel Writing Month, starts November 1 every year, and you’re urged to write an entire 50,000-word novel by the end of the month.

Wouldn’t it be great to actually finish a novel in 30 days?

That very idea has inspired millions of writers from all over the world to embark on this journey.

Since it began in 1999, when a handful of aspirants tried it, around a half million entrants take part each year now. Only between 10 and 15% actually finish, and NaNoWriMo refers to them as novelists.

Sounds fabulous, right?

Need help writing your novel? Click here to download my ultimate 12-step guide. What is NaNoWriMo?The official challenge is to write the first draft of a new, 50,000-word novel in 30 days — an average of 1,667 words per day.

These days, you may continue a book you’ve already started as long as you count only new words written in November.

The goal of NaNoWriMo is to shake you out of your writing comfort zone and show you what’s possible while providing resources, support, and accountability.

You’re encouraged to outline your novel in September and October. You create an account on the NaNoWriMo site and log your daily progress starting at 12:01 a.m. on November 1.

Once you hit 50,000 words, you upload your manuscript to the site for verification.

If you complete or “win” the challenge, you earn banners and certificates and can purchase t-shirts and other merchandise.

NaNoWriMo BenefitsWell, I can’t argue with the upsides:

The NaNoWriMo folks “believe stories matter.” So do I.

And in the last 18 years since this effort began, countless writers have raved to me that NaNoWriMo was the vehicle that finally motivated them to actually finish.

That’s no small thing. Over my four decades teaching writing, I’ve learned that the single most debilitating barrier to writers finishing writing their novels has been fear—fear that kills impetus.

I can’t count the number who have told me they can’t get started, let alone finish.

And as my film director son says about movies, simply producing one is a major accomplishment, let alone a good one. He compliments novice filmmakers for merely finishing.

The same is true about writing a novel.

So, yes, I’m all for anything that motivates a would-be novelist to start and (more importantly) to finish.

NaNoWriMo DownsidesHowever, I also have reservations.

Now, hear me, I’m not trying to talk you out of trying this. If it’s the trigger that results in your first finished novel, bravo!

But let’s take a closer look:

NaNoWriMo reports that over the years, 250 of its participants have seen their manuscripts sell to traditional publishing houses. That means the authors were paid to be published rather than paying to be printed.

Nothing to sneeze at. Until you do the math.

A rule of thumb in book publishing is that an unsolicited manuscript has about a 1 in 1,000 chance of landing a traditional book deal. While the figure may be unscientific, it’s not hyperbole.

That’s why I teach writing and publishing—so you can improve your odds.

What are the odds your NaNoWriMo 2020 manuscript will be traditionally published? Without knowing the total number of novels written since the effort began (this is its 17th year), it’s impossible to say.

But one thing I can say for certain: The odds are way worse than 1 in 1,000.

In fact, if every success story had happened last year alone—in other words, had all 250 published novels come from only the 431,626 NaNoWriMo manuscripts completed last year—your chances of ultimate success would be 1 in more than 1,725.

But those 250 traditionally published novels have come from all the NaNoWriMo manuscripts written since 1999. While not every year would have represented more than 400,000 writers, surely the total is in the millions.

My NaNoWriMo Caution? Need help writing your novel? Click here to download my ultimate 12-step guide.As a writing coach, my goal is to help get your work to where it’s marketable to traditional publishers. That’s the sole purpose of this blog and The Jerry Jenkins Writers Guild. So, far be it from me to criticize a well-intentioned program like NaNoWriMo.

It appears to me their goal is not to see you finish a pristine manuscript ready for the marketplace. Their aim, and it’s a worthy one, is to encourage.

NaNoWriMo serves to prove to you that you can both start and finish a novel of at least 50,000 words. And that’s just what many writers need.

If you believe it would work for you, motivate you, get you to finally get going on your novel, I say go for it.

My caution is to not make more of the result than it deserves.The benefit: You knock out a first draft.

The danger: You assume your work is done.

Bottom line: I applaud NaNoWriMo for what it’s meant to so many writers who need a deadline to finally finish novel manuscripts. I urge you to see the result as only that for now.

Should You Enter NaNoWriMo?Yes, if it helps you:

Schedule non-negotiable writing time.Keep that writing time sacred.Establish your writing space.Start a daily writing routine.Overcome procrastination.Feel more confident about sharing your work.Push through the Marathon of the Middle.Join a writing critique group.Be accountable.Whatever you decide, remember that this is only the first stage. Your novel may not even be finished (an average novel is closer to 64,000 words).

But beyond that, the work has just begun.

Finishing your fiction manuscript doesn’t make you a novelist. You’re still an aspiring novelist, and I’d LOVE to see you fulfill your dream.

I’ve harped on this before: If getting traditionally published were easy, anyone could do it.

The part of the process NaNoWriMo proves can be done quickly is getting your first draft down. Just realize that if you were building a house, what you would have after a month of frenzied work is the foundation and shell.

Your novel’s foundation has been dug and laid, and its studded shell is standing. Now it’s time to pour yourself into wiring, plumbing, drywalling, trimming, painting, and furnishing it.

That’ll take a lot longer than a month, and I ought to know. I’ve averaged an output of four books a year since 1974.

Some things can’t — and simply shouldn’t — be rushed.

If you’re gearing up for the next NaNoWriMo challenge, I wish you the best. Check back here the first week of December for what to do next. My hope is that your foundation and frame are ready for a LOT of finish work.

Need help writing your novel? Click here to download my ultimate 12-step guide.The post Participating in NaNoWriMo This Year? Caution! appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

February 8, 2022

How to Write Plot Twists: Your Complete Guide

Mastering how to write plot twists involves more than just throwing a monkey wrench into your story.

A well-written plot twist must be subtle.

You’ll need to learn:

How to set up a plot twistWhere to insert oneHow to use it to drive the main plotMistakes to avoidWhat is a Plot Twist?If plot is the sequence of events that makes up your story — what happens to keep readers turning pages, plot twists are unexpected, unpredictable, surprising, events or revelations that turn everything inside out.

Why does surprise matter?

Predictability bores. And it’s a sin to bore your reader.

A good plot twist strengthens your story and can make it unforgettable.

So it’s worth your time to learn to write good ones.

How to Write Plot Twists That WorkOnce readers are confident about where your story’s going, upend their expectations with new developments.

While plot twists may most commonly be associated with endings, they can happen any time after you’ve established your readers’ expectations.

The most common plot twist pitfall is that they’re too obvious.

Avoid tropes — situations that have been so overused that your story becomes predictable and clichéd.

Also avoid dropping so many hints that the twist is easy to see coming.

If readers aren’t surprised, they’re bored.

So how do you know if your plot twist works?

Readers will tell you.

Well-written plot twists:

1. Are carefully foreshadowed.Plant enough clues so readers will be surprised but not feel swindled. Give away too much and the reader guesses what’s coming. While your twist shouldn’t be obvious, readers should be able to recognize the signs when they look back. Think The Sixth Sense or The Sting movies.

2. Use subtle misdirection.Be a little devious. Guide readers to suspect one resolution, and then reveal it as a dead end. But beware: A little goes a long way here. Be careful not to frustrate your audience.

3. Don’t rely on coincidence.The twist must make sense or readers won’t buy it. Sure, coincidences happen in real life, but too many stretch credibility.

4. Are consistent with your story.You can reveal new information, but it must be realistic and believable.

5. Maintain tension.Don’t take your foot off the gas. Keep tension building and you’ll ratchet up the excitement.

6. Don’t overdo it.Limit yourself to one plot twist per book. Any more will appear contrived.

12 Plot Twist Examples

Readers assume an early character is your lead — but he soon dies, disappears, or is revealed as the antagonist. False protagonist twists can be tricky, but they can result in memorable stories.

Killing off a character makes readers fear that no one is safe.

Examples include Ned Stark in Game of Thrones, Marion Crane in Psycho, and Don Vito Corleone in The Godfather.

2. Betrayal and secretsThe main character has been misled, lied to, used, or double-crossed. A character appears to be an ally, but once their true nature is revealed, the main character no longer knows who to trust.

3. Poetic justiceOne common example is a villain killed by his own gun.

Unfortunately, poetic justice has been used so much that it’s become a cliché. You risk alienating readers if you come across as too preachy.

The upside is that poetic justice can be emotionally satisfying to readers who love happy endings.

4. FlashbacksThe problem with these is that they take readers offstage to visit the past. Even if they reveal something important to the story, the danger is the cliché of a character daydreaming or actually dreaming and — after the flashback — being jarred back to the present by something or someone interrupting him.

Better to use backstory straightforwardly by simply using a time and location tag, flush left and in italics, and telling the story from the past as if it’s onstage now. In that way, backstory can propel your story.

5. Reverse chronologyNovels that start at the end and progress backwards use a series of backstories that result in a surprise.

The psychological thriller Memento features a main character who cannot retain new memories. The story starts at the end — with a shooting, and proceeds back as the protagonist pieces together his past. Such stories focus less on what happened than on why and how.

6. In medias resThis Latin term means “in the midst of things.” Don’t mistake this to mean your story must start with physical action. It certainly can, but in medias res specifically means that something must be happening.

Not setup, not scene setting, not description. It can be subtext, an undercurrent of foreboding, but something going on. The story essentially starts, giving the reader credit that he will catch on, with important information revealed later.

7. Red herringThis popular device, especially in mysteries and thrillers, seems to point to one conclusion — which turns out to be a dead end with a reasonable explanation.

Agatha Christie was a master at having several characters behave suspiciously, though in the end only one is guilty. Check out her And Then There Were None.

8. A good catastropheJ.R.R. Tolkien used this in his novels. When everything is going terribly and the characters believe they’re doomed, suddenly there’s salvation. The key is that the protagonist must believe his end is coming.

An example: In The Lord of the Rings, Gollum takes the ring from Frodo, and we think all is lost. But then he dives into the volcano, saving everyone.

9. Unreliable narratorIn this twist, the point of view character either doesn’t know the whole story (due to youth or naïveté), has a distorted perception, or is blatantly lying.

Popular examples include Pi Patel in The Life of Pi, Mrs. De Winter in Rebecca, and Forrest in Forrest Gump.

10. A twist of fateRandom chance ushers in a sudden reversal of fortune, usually from good to bad. The main character either gains or loses wealth, status, loved ones, or long-held beliefs.

It’s crucial to make such a twist believable. (See #3 under How to Write Plot Twists That Work above.)

11. RealizationThis turning point of deep recognition or discovery is my least favorite, to the point where I don’t recommend it. I prefer twists that come as a result of an external, physical act.

12. Deus ex machinaIn ancient Greek and Roman stories, this plot twist was known as an act of God, literally meaning “god from the machine.” This refers to a crane-like device play producers used to fly an angel or other ethereal being into a scene to save the day.

These days, the term refers to an implausible and unexpected introduction of a brand new element that does the same. Frankly, it’s a huge mistake and is seen by agents, publishers, and readers as the easy way out.

Avoid this twist at all costs, unless you’re writing parody or satire.

8 Plot Twist Tropes to Avoid

Several have been done to death, so recycling them risks a boring, predictable plot. You should read dozens and dozens of books in your genre so you’ll recognize what works and what doesn’t.

Tropes are often the result of lazy writing.

Long-lost family. A popular example is, “Luke, I am your father!” from Star Wars. In The Return of the Jedi we discover that Luke and Leia are twins. The dream. The entire story was a dream or hallucination, as in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and The Wizard of Oz. The elaborate ruse. The villain is so clever he can anticipate the protagonist’s choices at every step, leading the main character to an unlikely outcome. Beauty and the Beast. A beautiful woman falls for an ugly man because of his personality. The Chosen One. Especially in Young Adult fantasy, a young person is expected to save the world simply because of his birth lineage. The Resurrected. Someone presumed dead magically recovers to fatally shoot or injure an antagonist. The Love/Hate Dilemma. Two people who initially hate each other end up falling in love. This is one of the oldest tropes in the romance genre. The Unexpected Aristocrat. Discovering the lead character is actually part of a royal line.You Can Write Good Plot TwistsWatch your favorite movies or stream the latest series, paying attention to plot twists.

Then use your new understanding to make your next novel the best it can be, keeping these tips in mind.

And once you have a promising idea, head over to my 12-step novel writing guide.

The post How to Write Plot Twists: Your Complete Guide appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

January 18, 2022

How to Create a Character Profile: A Step-by-Step Guide For Beginners

List your favorite novels, those you can count on one hand, and I’ll bet they have one major thing in common — an unforgettable hero.

Regardless the genre, your characters must behave like real people in real-life situations who make mistakes, have regrets, and grow emotionally or spiritually throughout the story. Fail, and it shows.

Some master novelists make this look easy, but it’s a skill that takes time to refine.

As a Pantser (one who writes by by the seat of his pants as a process of discovery), I follow Stephen King’s practice of “putting interesting characters in difficult situations and writing to find out what happens.”

Part of the high wire act of writing as a Pantser, often the character surprises you and you must do some back hoeing to make it work. You may find yourself thinking, as I frequently do, Aah, so that’s why he’s the way he is.

But if you’re a novice writer, or you’d classify yourself as an Outliner rather than a Pantser, you might rather create a character profile before you begin writing your novel.

If that’s you, let me walk you through the various elements of a character profile and what questions to answer. Then I’ll leave you with a Character Profile Template I developed to help simplify the process.

What Is a Character Profile?It’s an in-depth life history of a fictional character.

Those who espouse building character profiles naturally advise that your protagonist, antagonist, and each of the more important orbital characters in your story get their own separate profile.

Many great novelists and colleagues of mine swear by them and wouldn’t dream of developing a character any other way. If you’ve never written one, you may find this tool helpful in jumpstarting your own creativity.

Character profiles can help you:

Write faster, because you’re not working from scratchMaintain continuityAdd plot twistsAdd character depthBuild stronger relationships between charactersThe more detailed the profile, the richer your character motivations are bound to be.

For example, a character bullied as a child might grow up a career criminal — or the opposite, someone empathetic with and compassionate to the disenfranchised.

Some writers delve deep enough to actually turn each profile into its own short story. Some add the character’s favorite quote, hobby, quirks, favorite foods, fears, and childhood memories.

But beware: don’t dump every detail into your story.

A profile is simply background information (backstory) designed to inform you about your characters. It helps you to get to know them well enough to be able to reveal to your readers what’s most important for the sake of the story.

Just be sure to allow readers to deduce some things for themselves, giving them a role in the reading experience. Avoid spoon feeding every detail. Allow the theater of their mind to fill in the blanks.

Create a Character Profile in 5 Steps

Determine the following with as much, or as little, detail as you feel you need to get to know your characters. In essence, you want to conduct an interview with your fictitious character.

You may find yourself a hybrid of an Outliner and Pantser (as I often do), meaning you do need the security of an outline, but you also enjoy the freedom of letting your story and your characters take you where they will.

It’s your story. Have fun developing each character. Enjoy the process — you never know where they’ll take you!

1. Determine the character’s role.Begin by deciding which role your character will play. (It may prove to be more than one on the list, and in that case, strive to combine characters so they’re easier for the reader to identify and keep track of.)

Protagonist: the main character or heroAntagonist: the villainSidekickOrbital: neither lead nor bad guy, but prominent throughoutLove InterestConfidante2. Decide on the basics.Ask your characters who they are today — the good, the bad, and the ugly. Remember, they need to feel real and knowable, not perfect. Not only does perfect not exist, it’s boring. So, be creative. Your readers will thank you.

Full nameA nickname? Where did it come from?AgeCurrent hometownOccupationIncomeSkillsTalentsHobbiesShort Term GoalsLong Term GoalsHabitsBest qualitiesWorst qualitiesFavorite bookFavorite movieFavorite possessionGreatest passionFavorite foodsBest friendWorst enemy2. Establish physical characteristics.What does your character look and sound like? Again, this is largely for your own information.

Gone are the days when novels describe even the main character in such detail. Except for characteristics that affect the story, why not let each reader see the person however they choose?

HeightWeightBody TypeFitness levelHair colorHair type/styleEye colorGlasses/contacts?EthnicityDistinguishing features (birthmarks/scars/tattoos)QuirksAllergiesOverall appearance/upkeep/styleLimitations/handicaps3. Layer in emotional characteristics.It’s easy to conjure the appearance of a character, but what your character thinks and feels is what really drives him. What comprises his emotional makeup?

PersonalityAttitudesIntroverted or Extroverted?Spiritual WorldviewPolitical WorldviewStrengthsWeaknessesMannerismsMotivationsFearsInternal StrugglesSecretsWhat makes him happy?Deepest longingIf he could do or be anything, what would it be?4. Create a past.Who we are is shaped by our family background and experiences. Get to know your character’s story, and you’ll likely learn what motivates them to get out of bed every morning.

BirthdateBirthplaceAccentFamily members/birth order (describe relationships)ChildhoodEducationFirst jobsAccomplishmentsFailures5. How is this character involved in the story?Dig deeper. Finish with these questions:

What does he want? (a novel-worthy goal or challenge)What are his needs or desires?What or who stands in his way?What will he do about it?What happens if he fails? (the stakes must be dire enough to carry an entire novel)What sacrifices will he have to make?What fundamental changes do you see coming in him?What heroic qualities need to emerge for him to succeed?Time to Get StartedReady to create a profile for your lead character? Feel free to create your own character questionnaire, or use the Character Profile Template I created.

You might base your first character on one of your best friends, a quirky relative, or an adult you remember from childhood — maybe a mixture of all three!

Regardless who you pattern him after, develop a character who feels real, and he could become unforgettable.

The post How to Create a Character Profile: A Step-by-Step Guide For Beginners appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

January 4, 2022

How to Write Flash Fiction: 5 Tips for Writing Short Short Stories

Imagine a short story, then make it even shorter.

That’s flash fiction.

Short stories run anywhere between 1,500 and 10,000 words. Flash fiction stories run up to 1,500 words — but often much shorter. Usually up to 500 words.

If you get down to 100 words or fewer, that’s micro fiction.

Flash fiction contests tempt new writers. After all, writing 500 words sounds a lot less daunting than 5,000.

But if you’re a brand new writer, flash fiction may not be for you. It takes skill to condense a story that much.

If you’re more experienced, flash fiction can be a great way to experiment with new story ideas, try a new style, and become a better writer — without committing a lot of time.

Tips for Writing Memorable Flash Fiction1. Include ConflictRegardless the length of your story, conflict is the engine of fiction. No conflict, no story.

Your flash fiction piece must have conflict. That could be external — between two characters, between a character and society, or even between a character and nature. Or it could be internal conflict, a struggle within the character’s own mind.

2. Avoid Throat ClearingYou won’t have the time or space for much description, backstory, philosophizing, or anything that slows your story. Rather than telling the reader everything about the setting, suggest a few details that’ll trigger the theater of the reader’s mind.

Most important, jump straight into your story. You don’t have words to spare on introducing your characters at length.

3. Use Dialogue SparinglyCut flash fiction dialogue to the bone. There’s no room in any length fiction for banal, on-the-nose greetings and small talk. Pared down dialogue should move the story along, helping to reveal character and advance the plot.

Cut the dead wood from your dialogue — and what’s left will be much more powerful. Remember, what remains unsaid, or appears as subtext, can also be hugely significant.

4. Aim for the HeartEven in 100 words, you should strive for an emotional connection. Your story should carry a punch. Without shoehorning it in or becoming maudlin or cheesy, you want to make the reader laugh, cry, feel moved.

Before you start, have an idea of what you want the reader to take away from your story and to feel. That’s the way to potentially write something truly memorable.

5. Keep the End in MindFrom the first word of your piece, know where you’re headed. Every sentence should lead to the final one. Your writing tone should be consistent throughout and build to the ending.

Flash fiction deserves aggressive, even ferocious, self-editing as much as a longer piece does. Edit thoroughly so that your whole piece builds to the end. This can be great training for getting to the place where you’re happy with every word.

Ready to Give Flash Fiction a Try?Do you have a few short stories under your belt already? Maybe it’s time to challenge yourself with a flash fiction piece. It can be fun, but perhaps not as easy as it looks.

Click here for plenty of free writing contests seeking stories as short as 53 words. Good luck!

The post How to Write Flash Fiction: 5 Tips for Writing Short Short Stories appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

December 21, 2021

How to Format a Manuscript for Self-publishing

Guest Post by Dave Chesson

It can seem complicated to format a manuscript for self-publishing, but with the right software and formatting knowledge, it’s not as difficult as you may think.

In this article, I’ll provide you with the know-how to properly format your manuscript for printing or ebook publication. You’ll also learn which software programs are best to help you through the process.

Why is Book Formatting Important?Because you want the words and images to make a cohesive unit. Otherwise, the finished project will look unprofessional, resulting in poor sales and bad reviews.

Good formatting means making sure all the text looks good, from margins and headers to pagination. You want a book that’s visually appealing and easy for readers to follow, so they never lose interest.

Certain guidelines must be followed when formatting ebooks or print books, including font styles, margins, and layout.

The Difference Between Formatting a Book and Formatting a Manuscript

Manuscript formatting is when you prepare a document to submit to an editor, publisher, or agent. It involves making sure your document has the right margins and spacing, but you are not preparing a finished product for sale.

Book formatting for self-publishers, on the other hand, is where you prepare an ebook or print book the way it will look when it actually ends up in the reader’s hands. It will no longer look like a manuscript. It must look the way a published book looks.

This article focuses exclusively on book formatting, not manuscript formatting.

Ebook vs. Print Formatting: What to Watch Out ForEbook FormattingEbooks differ from print books. First, you don’t have to worry about setting the font size, line height, page numbers, or margins, as these are automatically determined by the e-reader.

Additionally, individual users are able to change these inside their Kindle or Nook.

Instead, concentrate on:

Paragraph indentations: Make sure they’re uniform and similar to the indents in traditionally published books.Chapter titles: Professionalism is key here. Add images and tasteful fonts to make your chapter headings pop, but avoid extremes.Contents: In ebooks the Contents page should link directly to each section, rather than listing specific page numbers. Most formatting tools will automatically do this for you. And avoid the archaic label ”Table of Contents,” which says no more than “Contents.”Page breaks: Each new chapter should start on a new right hand page.Hyperlinks: Include such in your ebook to direct your reader to any place on the Internet.Footnotes: You can’t include footnotes on the same page as your text in an ebook, so they need to be converted to endnotes so they show up at the end of each chapter.Print Formatting

Formatting your print book can be a lot trickier if you’re not careful. Good formatting software will help.

Margins: You need to ensure the right margins so your text has plenty of white space around it and doesn’t get cut off. Amazon offers guidelines about how wide these margins should be.Gutter size: The gutter is the margin on the inside-facing part of your pages — in the middle. Naturally, it appears on the right of the left page and on the left of the right page. Its size should account for the space you need for bookbinding.Font: To avoid being a telltale self-published book, choose among the few fonts used by traditional publishers — a serif type and easily readable.Headings: Each page of your print book should contain the book title, the chapter title, or the author’s name.Trim size: This is the actual size of your printed book. It can range from a huge textbook to a mass-market paperback. Trim size affects page count.The above applies to formatting a standard print book. Click here if you are producing a large print book.

Formatting SoftwareWhile Microsoft Word is great for manuscript preparation, it’s not the best for formatting a book for self-publishing.

A few options:

AtticusAtticus is relatively new and is quickly becoming one of the leading choices.

It formats manuscripts for both ebook and print and even has large print options.

Plus it’s over $100 cheaper than the leading alternative and works on Windows, Mac, Linux, and Chromebook.

VellumVellum has many of the same features as Atticus.

It sells for $199 for basic ebook formatting and $249 if you want to add print formatting. It is known for resulting in beautiful books and for making the process easy.

Scrivener CompileCompared to Atticus or Vellum, the lower priced Scrivener is complicated.

However, you can make do with Scrivener’s compile feature.

Kindle CreateA free option, Kindle Create was designed by Amazon to format books. It is limited in its design functions and carries a learning curve.

I recommend Atticus as a first choice, followed by Kindle Create if you’re on a budget.

But what if you don’t want any of the tools on this list?

Should You Hire a Formatter?Formatting a book yourself may be too much to worry about. If that’s you, consider hiring a formatter. The best place to find one is on Fiverr or Upwork. Carefully vet the options and invest the time to find a good formatter you can afford.

However, formatters generally charge more than the cost of the formatting programs listed above.

What programs have you used? Was there one you love that I missed? Let me know in the comments, and I will check them out.

Dave Chesson is the creator of Kindlepreneur.com , a website devoted to teaching advanced book marketing . His tactics help both fiction and nonfiction authors of all levels get their books discovered by the right readers.

The post How to Format a Manuscript for Self-publishing appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

December 6, 2021

The Hemingway Editor: What is it and Can it Improve Your Writing?

Guest Post by Tami Nantz

If you want to be taken seriously as a writer, it’s imperative you become what Jerry calls a ferocious self-editor.

There’s no way around it.

Little irritates an agent or a publisher’s acquisitions editor more than having their time wasted by a writer who doesn’t edit and revise his own work before submitting it for consideration.

Given the vast array of training and resources for doing just that, now available on the internet, there’s no excuse.

You don’t have to be an English grammar expert to write well — but you do have to know how to self-edit. It takes work and perseverance, and most writers face a learning curve.

But in the end it’s worth it, and it can revolutionize your writing and your chance at success.

While learning to recognize and remedy your mistakes, an app like The Hemingway Editor can help save you time and frustration. And it can also make you a better self-editor, and thus, a better writer.

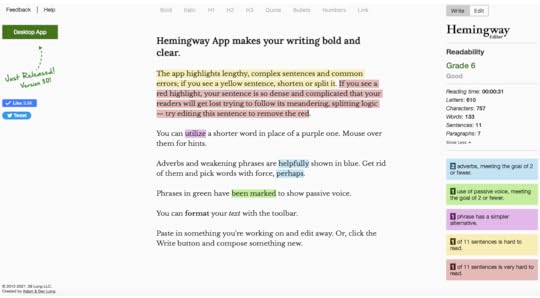

What is the Hemingway Editor?Ernest Hemingway was a pioneer in a simple, direct writing style, exactly what the Hemingway App seeks to deliver.

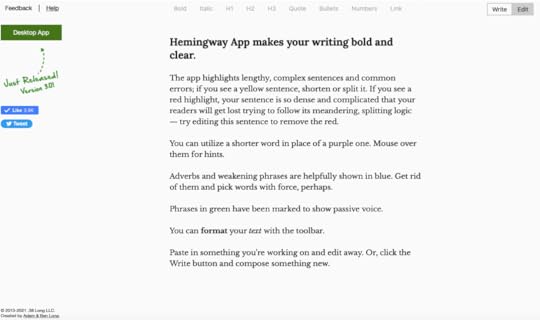

It’s a web and desktop self-editing tool created by Adam and Ben Long that highlights the overuse of adverbs and passive voice, and flags wordy sentences — common errors writers make.

It does not, however, highlight most grammatical or spelling errors, and is not intended to function as a comprehensive editor.

The web version of the app is free. The desktop version carries a one-time $19.99 fee and is available for both Mac (OSX 10.9+) and PC (Windows 7+) systems.

How the Hemingway Editor WorksAs editing apps go, this one ranks high in the easy-to-use category. Both versions allow you to work in write or edit mode and easily switch between the two.

Write ModeThe writing mode works like any word processor, but it won’t distract you by highlighting misspelled words as you go. To use the online version, simply highlight the sample text, delete it, and paste in or create your own.

But beware: There’s no automatic way to save or back up your work — so unless you copy and paste it into Word or something similar, if you lose your connection, you may lose your work.

You’re better off writing in a separate program and copying and pasting it into the Hemingway App before using the app.

Once you’re ready to edit, click on “Edit” mode in the upper right hand corner.

Edit mode displays formatting options at the top and allows you to view the Hemingway App’s suggested edits (highlighted), which are also summarized in the column on the right.

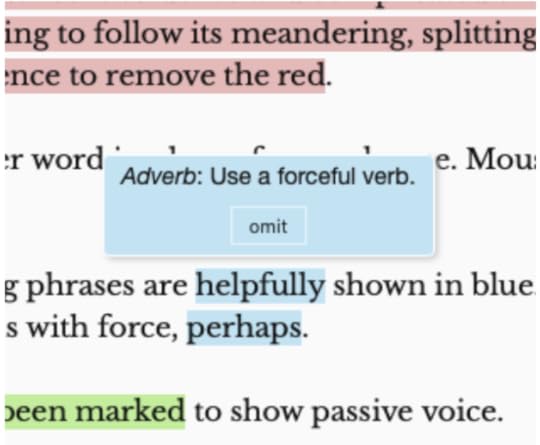

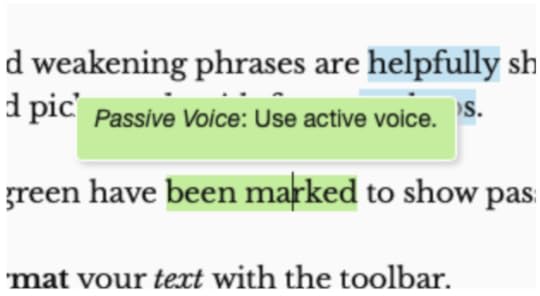

The varied colors allow you to easily identify each type of error.

In the case of words or short phrases, simply hover above the highlighted area for suggestions to appear.

Once you make the suggested edits, the highlights will disappear.

The Hemingway Editor also gives your writing a readability score, and displays just below it other specifics like word count and reading time.

Blue: highlights weak words, typically adverbs.

E.B. White, the author of Charlotte’s Web and one of the authors of The Elements of Style, suggests you “Write with nouns and verbs, not with adjectives and adverbs. The adjective hasn’t been built that can pull a weak or inaccurate noun out of a tight place.”

For additional help, I recommend Jerry’s post 249 Strong Verbs That’ll Instantly Supercharge Your Writing.

Green: highlights the use of passive voice.

Instead, eliminating as many state-of-being verbs as you can will tighten and clarify your writing.

For more on this common issue, read Jerry’s post, How to Fix Passive Voice.

Purple: highlights complicated words or phrases and sometimes suggests a replacement, aiming for clear, concise writing.

Yellow: highlights complex sentences and paragraphs and suggests shortening them.

Red: highlights complex, very hard-to-read sentences and paragraphs.

Two primary differences between the free and paid versions:

The free version does not allow you to export or save your work.The paid version not only allows you to save and export your documents, but you are also given the option of publishing directly to WordPress or Medium.Both versions offer the full Hemingway Editor analysis.

Bottom line, for short pieces and quick help, the free version is sufficient. If you’re writing anything longer, or planning to publish online, the paid version may be worth your investment.

Hemingway Editor Pros and ConsProsIt’s easy to use.You can test it without obligation.The offline editor is worth the price of the app.The free online version is sufficient for editing short pieces, though you will have to cut and paste when you’re finished.It’s great for helping you learn to be more concise.The separate modes allow you to edit while you write, if you wish.ConsThe free version doesn’t allow you to save your work.It’s not a comprehensive grammar or spelling checker.How Does the Hemingway Editor Stack Up Against the Competition?If you’re looking for a free app to help you self-edit, The Hemingway Editor can be a great addition to your writing toolbox.

For a more comprehensive editing program, ProWritingAid or Grammarly may be a better fit.

Hemingway App vs. ProWritingAidProWritingAid helps you edit every aspect of your writing, so it’s far more thorough in helping review and analyze your writing.

ProWritingAid also offers a less comprehensive free version that allows you to try the program, as well as an annual membership option with or without the plagiarism check.

Like the Hemingway App, you are able to download the ProWritingAid app for ease of use. It’s compatible with Microsoft Word, Scrivener, or any other writing program.

For more on ProWritingAid, click here to read Jerry’s full review.

Hemingway Editor vs. GrammarlyGrammarly is closer to the Hemingway Editor in terms of purpose, however, you must download the app to use it.

Grammarly beats the competition by spotting spelling errors and highlighting grammar and punctuation issues. It also spots passive voice, redundancies, and complex sentences.

The free version may be all you need, but the more comprehensive version will cost:

$30 per month for the monthly subscription$60 every three months for the quarterly subscription$144 for the annual subscription (billed as one payment)

For more on Grammarly, click here for Jerry’s full review.

The Hemingway Editor: Can it Really Improve Your Writing?If you’re a beginning writer or just looking for a free or reasonably-priced app that helps you tighten your writing, the Hemingway Editor could be a useful tool.

The app is helpful in recognizing complex, wordy sentences and passive voice, but because it misses so many other issues, it ranks below ProWritingAid and Grammarly for me.

Nothing replaces actually doing the writing and learning to effectively self-edit. Tools like the Hemingway Editor can help you, but they won’t write for you.

Tami Nantz is a freelance writer. She lives with her family near Washington, D.C. More of her work can be found at TamiNantz.com.

The post The Hemingway Editor: What is it and Can it Improve Your Writing? appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

November 22, 2021

How to Research a Nonfiction Book: 5 Tips for Writers

That you’ve landed here tells me you have a message you want to share in a book.

You’re eager to start writing, but you first need to conduct some research.

Problem is, you’re not sure how to research for a nonfiction book.

You may even wonder whether research is all that important.

You may be an excellent writer, but even a small factual mistake can cost you the credibility of your readers.

Over the last nearly half century, I’ve written 200 books, 21 of them New York Times bestsellers. So I ought to be able to write a book on my area of expertise — writing and publishing — based on my experience alone, right?

Wrong.

I wouldn’t dare write such a book without carefully researching every detail. Because if I get one fact wrong, my credibility goes out the window. And I’d have only my own laziness to blame.

Thorough research can set your book — your message — apart from the competition.

As you research, carefully determine:

How much detail should go into your bookWhether even if it’s interesting, is it relevant?To remain objective and not skew the results to favor your opinionsTo use research as seasoning rather than the main course (your message)As you weave in your findings, always think reader-first. This is the golden rule of writing.

Your job is to communicate so compellingly that readers are captivated from the get-go. This is as important to how-to manuals and self-help books as it is to a memoir.

5 Tips for Researching Your Nonfiction Book1. Start With an OutlineWhile the half or so population of novelists who call themselves Pantsers (like me), who write by the seat of their pants as a process of discovery, can get away without an outline, such is not true of nonfiction authors.

There is no substitute for an outline if you’re writing nonfiction.

Once you’ve determined what you’d like to say and to whom you want to say it, it’s time to start building your outline.

Not only do agents and acquisitions editors require this, but also you can’t draft a proposal without an outline.

Plus, an outline will keep you on track when the writing gets tough. Best of all, it can serve as your research guide to keep you focused on finding what you really need for your project.

That said, don’t become a slave to your outline. If in the process of writing you find you need the flexibility to add or subtract something from your manuscript, adjust your outline to accommodate it.

The key, again, is reader-first, and that means the best final product you can create.

Read my blog post How to Outline a Nonfiction Book in 5 Steps for a more in depth look at the outlining process.

2. Employ a Story StructureYes, even for nonfiction, and not only for memoirs or biographies.

I recommend the novel structure below for fiction, but — believe it or not — with only slight adaptations, roughly the same structure can turn mediocre nonfiction to something special.

While in a novel (and in biographical nonfiction), the main character experiences all these steps, they can also apply to self-help and how-to books.

Just be sure to sequence your points and evidence to promise a significant payoff, then be sure to deliver.

You or your subject becomes the main character in a memoir or a biography. Craft a sequence of life events the way a novelist would, and your true story can read like fiction.

Even a straightforward how-to or self-help book can follow this structure as you make promises early, triggering readers to anticipate fresh ideas, secrets, inside information — things you pay off in the end.

While you may not have as much action or dialogue or character development as your novelist counterpart, your crises and tension can come from showing where people have failed before and how you’re going to ensure your readers will succeed.

You might even make a how-to project look impossible until you pay off that setup with your unique solution.

Once you’ve mapped out your story structure, determine:

What parts of my book need more evidence? Would another point of view lend credibility?What experts do I need to interview?3. Research Your GenreI say often that writers are readers.

Good writers are good readers.

Great writers are great readers.

Learn the conventions and expectations of your genre by reading as many books as you can get your hands on. That means dozens and dozens to learn what works, what doesn’t, and how to make your nonfiction book the best it can be.

4. Use the Right Research ToolsDon’t limit yourself to a single research source. Instead, consult a range of sources.

For a memoir or biography, brush up on the geography and time period of where your story took place. Don’t depend on your memory alone, because if you get a detail wrong, some readers are sure to know.

So, what sources?InterviewsThere’s no substitute for an in-person interview with an expert. People love to talk about their work, and about themselves.

How do you land an appointment with an expert? Just ask. You’d be surprised how accessible and helpful most people are.

Be respectful of their time, and of course, promise to credit them on your Acknowledgments page.

Before you meet, learn as much as you can about them online so you don’t waste their time asking questions you could’ve easily answered another way.

Ask deep, fresh, personal questions unique to your subject. Plan ahead, but also allow the conversation to unfold naturally as you listen and respond with additional questions.

Most importantly, record every interview and transcribe it — or have it transcribed — for easy reference as you write.

World AlmanacsOnline versions save you time and include just about anything you would need: facts, data, government information, and more. Some are free, some require a subscription. Try the free version first to be sure you’ll benefit from this source.

AtlasesOn WorldAtlas.com, you’ll find nearly limitless information about any continent, country, region, city, town, or village.

Names, time zones, monetary units, weather patterns, tourism info, data on natural resources, and even facts you wouldn’t have thought to search for.

I get ideas when I’m digging here, for both my novels and my nonfiction books.

EncyclopediasIf you don’t own a set, you can access one at a library or online. Encyclopedia Britannica has just about anything you’d need.

YouTubeHere, you can learn a ton about people, places, addictions, hobbies, neuroses — you name it. (Just be careful to avoid getting drawn into clickbait videos.)

Search EnginesGoogle, Bing, DuckDuckGo, and the like have become the most powerful book research tools of all — the internet has revolutionized my research.

Type in any number of research terms and you’ll find literally (and I don’t say that lightly) millions of resources.

That gives you plenty of opportunity to confirm and corroborate anything you find by comparing it to at least 2 or 3 additional sources.

ThesauriThe Merriam Webster online thesaurus is great, because it’s lightning fast. You couldn’t turn the pages of a hard copy as quickly as you can get where you need to onscreen.

One caution: Never let it be obvious you’ve consulted a thesaurus. Too many writers use them to search for an exotic word to spice up their prose.

Don’t. Rather, look for that normal word that was on the tip of your tongue. Just say what you need to say.

Use powerful nouns and verbs, not fancy adjectives and adverbs.

Wolfram AlphaView this website as the genius librarian who can immediately answer almost any question.

Google ScholarThis website offers high quality, in depth academic information that far exceeds any regular search engine.

Library of CongressA rich source of American history that allows you to view photos, other media, and ask a librarian for help if necessary.

Your Local LibraryThe convenience of the internet has caused too many to abandon their local library. But that’s a mistake. Many local libraries offer all sorts of hands-on tools to enhance your research effort.

5. Avoid Procrastination: Set a DeadlineAt first glance, researching for your nonfiction book may sound like homework, but it can be fun. So fun it can be addicting — the more we learn, the more we tend to want to know.

Many writers use research as an excuse to procrastinate from writing.

To avoid this, set a firm deadline for your research, and get to your writing. If you need further research, you can always take a break and conduct it.

Time to Get StartedThere’s no substitute for meticulous research and the richness it lends to your nonfiction writing. The trust it builds with readers alone is worth the effort.

Start with your outline, and before you know it, you’ll be immersed in research and ready to begin writing.

I can’t wait to see what you come up with!

The post How to Research a Nonfiction Book: 5 Tips for Writers appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

November 8, 2021

What is an Antivillain? How to Write a Complex Bad Guy

Too many novelists create a villain who does bad things because he’s the bad guy. He might as well appear in a melodrama, wearing a black hat and a cape while twirling his handlebar mustache.

But a melodramatic villain is a cliché by definition — predictable, unrealistic, and there just for fun. Hissing at the bad guy when he comes on stage may add merriment, but in serious fiction such characters don’t work.

Creating a realistic, believable villain requires subtlety and genuine motivation.

Enter the character with actions so subtle readers may not even know he’s the villain until he reveals his true colors.

(Note: I use the male pronoun inclusively here to refer to both genders.)

In real life — as it should be in your story — real villains don’t know they’re villainous. They don’t think they’re wrong; they believe their actions are justified.

Villains have reasons for what they do — and sometimes those reasons are good. This doesn’t mean they’re always right, but they can rarely be persuaded they’re wrong.

What is an Antivillain?Some — including many experts — refer to such fictitious characters as Antivillains. I don’t.

To me, a villain is a villain, and the more complex you can render him, the better. While the term Antihero is valid and worth studying, I contend that Villain is the right term for your bad guy.

What others may parse as an Antivillain and ascribe to him even more villainous complexities, I would simply call the right kind of villain. So, in this post, we’ll discuss how you can best create a worthy adversary for your protagonist.

The best, most credible villain can be a mostly virtuous, likable antagonist with sometimes even heroic goals, but whose methods are questionable — and ultimately evil.

Their actions sometimes fall into a morally gray category — making the reader wonder whether they are truly well-intentioned or monstrous.

Readers should be able to relate to your villain. He’s believable, his actions (even though bad) are understandable, and his motivations are mostly good — unless they’re not.

Forget Antivillains: Make Your Villain Complex, Even Likable

Want to really stand a story on its head and compel readers to keep turning the pages? Avoid caricatures and straw men by refusing to paint your villain as all bad.

Too often we see villains who hold the opposite view of, say, a social issue than that of the author or the main character. Fine. That’s a recipe for conflict and tension.

But the mistake is to then make the villain a disgusting human being. Try making him a great spouse and parent, perhaps a helpful, giving person. Someone you’d enjoy being friends with.

Yet, because he’s on the other side of the hero’s issue, he is, indeed, the villain. But the reader likes him!

Don’t we often see this in real life? Someone diametrically opposed to our worldview fights against our worthy cause.

We want to despise them, see them in an evil light. Yet when we meet them, they’re charming. That’s complicated. That’s real life. That makes for a great story.

The villain must still be defeated and right must win out. But not because the bad guy in the story is repulsive. Rather, in spite of the opposite.

That kind of thinking about your villain makes him complex and, frankly, more interesting. It also challenges you to write with more finesse.

The villain’s motivations are good, or at least justified, in his own mind, but in the end, he must fail.

4 Types of Complex Villains1. NobleThis type acts because he believes duty calls. He’s merely doing what needs to be done. He’s still wrong, of course, but he doesn’t see it that way.

Examples:

Dracus Malfoy and Regulus Black from the Harry Potter seriesJesse Pinkman and Mike Ehrmantraut in Breaking Bad2. PitiableReaders feel sorry for this character because perhaps he didn’t begin the story a bad guy. But in his mind, desperate times call for desperate measures, so he goes all in.

His character arc can be dramatic because often he’s so psychologically damaged that there’s no turning back.

Examples:

Carrie in Stephen King’s CarrieFrankenstein’s monsterAnakin Skywalker and Darth Vader in Star WarsLoki from ThorThe Master from Doctor Who3. Well-MeaningEver know somebody who means well, but everything they do makes things worse?

His intentions are good, but he’ll do anything to accomplish his goal. Sometimes he becomes aware how wrong his actions are and his character arc becomes redemptive. Or he might double down and become even more evil.

Examples:

Javert in Les MiserablesLady Melisandre in A Song of Ice and FireMarvel’s ThanosRaymond Reddington in The Blacklist4. Villain In Name OnlyThis character actually mirrors the hero in many ways. In fact, they may pursue the same goal, but with opposite motives.

At his core, he’s not really a bad guy. His intentions may be mostly good, and he’s smart, but dangerous — mainly because he’s likable and no one suspects him.

Examples:

Many of the villains from Sherlock HolmesDr. Connors in The Amazing Spider-ManSergeant Shultz and Colonel Klink from Hogan’s Heroes5 Tips for Creating an Effective Villain

A good bad guy is foundational to powerful fiction — he can make or break your story. The more formidable your antagonist, the more compelling your hero.

Your villain must:

1. Have a realistic and sympathetic backstory.This gives him reasons for being who he is and doing what he does.

2. Have strong motivations.Reveal what drives him — his Why.

Potential stimuli:

FearCuriosityGreedHunger for powerRevengeHonorLoveEthicsPrideJusticePotential threats:

ViolenceAbuseInjuryIllnessNatural disasterLossGriefMilitary combat3. Exhibit power.He will stop at nothing to get what he wants. Avoid making him a bumbler. That doesn’t make for a worthy opponent for your hero.

4. Force your protagonist to make difficult decisions.Because your villain may seem to have mostly good intentions, it’s often hard to tell if he’s good or bad, which poses a problem for your hero.

Remember, your main character becomes more heroic the more worthy his opponent.

A truly authentic villain competes with your hero for the same goal — only for different reasons.

Writer and writing coach Joanna Penn says it’s important you make the conflict specific and the hero’s adversary appear unbeatable. This forces your main character to make difficult decisions and ultimately become heroic.

5. Cause the protagonist to grow.Increasingly difficult obstacles build the muscle a protagonist needs to become truly heroic.

Allow your villain to throw everything he’s got at your hero. His response will speak volumes about how he’s changed — or hasn’t.

Time to Get StartedDon’t shortchange your villain. Invest as much time crafting him as you do your lead.

Too many novelists create a deliciously evil but otherwise one-dimensional villain and wonder why their story falls flat.

Conjure instead a villain who surprises both your hero and your readers. Make him real and familiar and believable and credible — even attractive.

If you’re an Outliner, my character arc worksheet can help you get to know your villain.

If you’re a Pantser (like me), you may not have the patience for that and prefer to dive right into the writing. Do what works best for you.

I can’t wait to see what you come up with!

The post What is an Antivillain? How to Write a Complex Bad Guy appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

October 18, 2021

What is an Antihero? How to Write an Unconventional Protagonist

Everybody loves a story in which the hero is the ultimate good guy and triumphs over evil — like Superman or Harry Potter.

But beware. The #1 mistake you can make when developing characters is creating heroes that are perfect.

What reader can identify with perfection?

The most memorable, plausible, believable heroes exhibit human, flawed behavior.

Examples:

Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the LambsHolden Caulfield in The Catcher in the RyeJay Gatsby in The Great GatsbyScarlett O’Hara in Gone With the WindWalter White in Breaking BadThese less traditional character archetypes are so morally conflicted that they can often make much more realistic heroes than their traditional counterparts.

In this post, let’s explore the antihero archetype and examine five different types you can use to create a compelling character readers can’t help but love hating.

What is an Antihero?It’s a protagonist who lacks qualities portrayed in a traditional hero, like morality and courage, and often embodies behaviors you’d expect in a villain.

The motivation of antiheroes is mostly good — or they believe it is. Like villains, they are often sincere in justifying their behavior.

But they don’t always act for the right reasons. They are who they are — good when they need to be, bad when they believe circumstances dictate.

Fiction that resonates with readers is true to the human condition — characters must feel like real people in real situations.

One particularly satisfying character arc for an antihero that can make him resonate with readers and become unforgettable is when he becomes traditionally heroic in the end — like Scrooge in A Christmas Carol.

5 Types of Antiheroes

Too few real people change for the better throughout their lives. Things don’t turn out the way they dreamed, and they can become disillusioned, even bitter as reality sets in.

That’s one reason many escape to fiction — to live vicariously through someone for whom things turned out differently.

The antihero’s character arc must ring true, however. The last thing you want is your reader to say, “That would never happen.” When a surprising turn arises, it should seem inevitable but not predictable.

So, types of antiheroes you can create…

ClassicThe opposite of the traditional hero, this antihero is incapable of waging a good fight, self-absorbed, full of self-doubt, fearful, anxious, and not exactly the most balanced aerialist on the high wire.

Ideally, his character arc sees him become a true hero by overcoming the obstacles to his ultimate goal.

Examples:

Frodo from Lord of the RingsBilbo Baggins from The HobbitKnight in Sour ArmorThe most common antihero isn’t all that bad. His history explains, but doesn’t excuse his behavior.

He may be smart, know right from wrong, and ultimately have good intentions — he’s just a witty, sarcastic cynic who goes about things in the most logical way he believes possible.

Ideally, his character arc will see him overcome his shortcomings.

Examples:

Haymitch Abernathy from The Hunger GamesSeverus Snape from Harry PotterHan Solo in Star WarsRobert Ludlum’s Jason BourneMarvel’s Iron ManPragmaticThis antihero type knows right from wrong, but if something needs to be done, he’ll deal with the consequences. He’ll even kill if necessary.

Examples:

Sherlock HolmesTyrion Lannister in Game of ThronesEdmund Pevensie in Chronicles of NarniaWolverine in X-MenUnscrupulousSimilar to the Pragmatic antihero, this type will do anything to achieve his ultimate goal, but his morals are non-existent.

His character arc is basically flat, with him still doing whatever it takes to overcome his objective. Regardless how ruthless his actions, his intentions may be good.

Examples:

RamboJack Sparrow in Pirates of the CaribbeanConan the BarbarianJohn WickHero In Name OnlyOf all antihero types, this guy most blurs the line between hero and villain. His intentions are not mostly good; more often they’re not good at all.

In fact, he’s morally and ethically neutral. He does what has to do — to protect someone he loves, exact revenge, and he would qualify as the villain, were he not the protagonist.

We still pull for this antihero, but he might not win the day like the Classic or Knight in our Armor antiheroes.

Examples:

Walter White in Breaking BadHuckleberry in The Adventures of Huckleberry FinnWhat’s Your Favorite?Choose one type and brainstorm whom you might create to fit it.

If you’re an Outliner, my character arc worksheet can help you get to know your hero.

If you’re a Pantser (like me), you might rather dive directly into the writing. Do what works best for you.

Just remember, your antihero must overcome his obstacles, rise to the occasion, and win against all odds.

But he has to grow into that from a more than normal flawed state.

Credible, believable, antiheroes with dramatic character arcs make for the most memorable protagonists you can imagine.

I’m eager to see what you come up with. Let me know.

The post What is an Antihero? How to Write an Unconventional Protagonist appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.

October 5, 2021

How to Reveal a Character’s Internal Conflict

Guest post by Becca Puglisi

If you’ve been on the writing trail long enough, you’ve heard plenty of talk about conflict and the role it plays in storytelling.

Whatever form it takes, conflict creates tension while providing opportunities for characters to grow and evolve as they navigate their character arcs.

But some of the most compelling conflict doesn’t come from an external source. Rather, it comes from within the character. These character vs. self struggles include cognitive dissonance, with him wanting things at odds with each other.

Competing desires, moral quandaries, mental health battles, insecurity, confusion, self-doubt — internal conflict haunts the character because it affects not only how he sees himself, but it also alters his future and often the lives of the people he cares about.

They carry a heft that can’t easily be set aside.

Internal conflict is also critical for helping characters acknowledge habits that hold them back.

Without that soul-cleansing tug-of-war, Aragorn would still be a ranger instead of the rightful king. Anakin Skywalker would have denied the goodness within, leaving Luke to die at the hands of the emperor. The Grinch would’ve stolen Christmas.

So it’s important to include this inner wrestling match for any character experiencing a change arc. But equally important is how we reveal that struggle to readers. It’s all happening inside — meaning we have to be subtle.

The information has to be shared in an organic way through the natural context of the story. I’ve found the best method is to highlight the internal and external cues that hint at a character’s deeper problem.

Internal IndicatorsIf you’re writing from a viewpoint that allows you to reveal a character’s thoughts, it’s easier to draw attention to the struggle within. Just show the character experiencing the following:

Obsessive Thoughts

Whatever’s plaguing your character, she’s going to spend time figuring out what to do about it.

You don’t want to spend too much time in her head, because too much introspection can slow the pace and diminish the reader’s interest.

But the character should poke at the issue, examining it from different angles.

AvoidanceLike us, characters crave control and certainty, so not knowing what to do can make them feel incapable, afraid, and insecure.

Being constantly reminded of their unsolvable problem might be emotionally painful enough for them to try to escape it.

One way to convey this is by having them slam the door on a certain train of thought. Maybe they really immerse themselves into work as a form of distraction.

They may take avoidance a step further into full-blown denial, destroying paperwork or putting away mementos that remind them of the impossible decision. This shows the incongruence between what’s happening on the inside and the outside.

IndecisionWhen characters don’t know what to do, they must consider their options. Show the character vacillating between choices, playing out various scenarios, weighing the pros and cons.

External Indicators

If you’re limited in your ability to plumb a character’s depths — maybe because they’re not your perspective character — you can still show readers (and other cast members) that struggle by playing out the external signs of what’s happening inside.

Over- or Under-CompensationThe character won’t be happy with their own inability to make a decision or take action.

If their ego becomes involved or they’re the kind of person who wants to keep up pretenses, they may overcompensate by becoming pushy.

Controlling others may make them feel better about their inability to control their own lives.

Or, plagued with indecision, your character may become averse to making any choices at all. When even the smallest questions are raised, they defer to others.

Letting other people take the lead ensures the character won’t make a mistake, alleviating some of the pressure.

DistractionThe human brain can focus on only so many things at once. A character consumed with a troubling scenario isn’t going to have much mental time for anything else.

As a result, their productivity at work or school could take a hit. They may become forgetful. Responsibilities may be done halfway or fall to the wayside. These indicators evidence the chaos beneath the surface.

MistakesCharacters under pressure don’t always make the best decisions. Such mistakes can get them into trouble. For a usually level-headed character, this can serve as a neon sign to others that something isn’t right.

Emotional VolatilityA problem we can’t fix steals our peace, our sleep, and our joy. This may be normal for short periods, but when it continues for too long, one of the first things to go is emotional stability.

Such a character may lash out at others. Another may constantly be on the verge of tears, every little thing seeming like the last straw.

Your character’s responses depend on their personality and normal emotional range. Figure out which response makes the most sense and you’ll be consistent in your portrayal.

Reveal an inner struggle by focusing on the visible, underlying results of that conflict. Most important, know your character so you can predict how they’ll respond. Then you can clearly show what you know to readers.

Have questions about internal conflict? Find answers in my book The Conflict Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Obstacles, Adversaries, and Inner Struggles (Volume 1), available October 12, 2021.

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and other resources for writers.

Her books have sold over 700,000 copies and are sourced by US universities and used by novelists, screenwriters, editors, and psychologists around the world.

She shares her knowledge through her Writers Helping Writers blog and via One Stop For Writers—an online resource that’s home to the Character Builder and Storyteller’s Roadmap.

The post How to Reveal a Character’s Internal Conflict appeared first on Jerry Jenkins | Proven Writing Tips.