David Clinton's Blog, page 6

June 28, 2016

Why Is so Much Enterprise Documentation so Awful?

I spend a very large portion of my professional workday reading through technology documentation. Perhaps “reading through” isn’t quite the right way to describe it. At this point, it’s more like quickly scanning menus, FAQs, and paragraph headings for clues to where I can find the exact piece of information I’m after. With some exceptions, this tends to be the case whether I’m just looking for a quick confirmation of the right command line syntax or whether I’m trying to get my mind around a whole new technology.

I spend a very large portion of my professional workday reading through technology documentation. Perhaps “reading through” isn’t quite the right way to describe it. At this point, it’s more like quickly scanning menus, FAQs, and paragraph headings for clues to where I can find the exact piece of information I’m after. With some exceptions, this tends to be the case whether I’m just looking for a quick confirmation of the right command line syntax or whether I’m trying to get my mind around a whole new technology.

Web-based Technology Documentation: The art of underperformance

Now, I have no complaints with the people who provide detailed syntax guides and man pages – why should they reformat their entire document to highlight some obscure detail for which I may someday come searching? But when I’m trying to introduce myself to a complicated software package – to figure out its purpose and primary use-case – then it’s reasonable for me to expect a relatively predictable and comfortable route to my goal. Instead, I often encounter a project home page with links to multiple targets with names like “Getting Started,” “How to use…?” “Documentation” and, buried deeply under a few menu layers, “Quick Start Guide.”

Often, the pages I’m sent to will be incomplete, apparently the victims of changed minds and budget overruns. Others will cover outdated versions of the software that might easily have a feature set that’s significantly different than the latest version. Worse: the features might actually still exist but, between then and now, they’ve changed names and even icons.

Even if we ignore the quality of the writing – something that can be remarkably difficult and costly to control – and the intelligibility of individual documents, there often seem to be significant version control and project management problems. I can usually guess what happened: some customers complained that they couldn’t figure out how to use the software, so management – unable to properly assess the current state of the documentation on their own – ordered the creation of a complete new set from scratch. The project starts, but about half way through, the key contributor either leaves the company or is distracted by other deadlines and demands.

And there it sits until a few more customers complain that they, too, can’t figure out how to use the software. Rinse. Repeat.

Is poor documentation always evil? Absolutely not. I’m often amazed at just how much some open source projects manage to accomplish considering the limited resources they’re usually working with. And, in any case, as long as people (like me) aren’t volunteering to help out, we have no right to grumble.

Is all documentation evil? Nope. While you could argue that there’s way too much of it, Amazon’s AWS maintains a magnificent documentation resource that’s well-written, well-designed, and so well organized across the system that finding elements within any given page is predictable and fast. AWS isn’t the only success story out there, but it’s not exactly part of an overcrowded field, either.

Technology Books: the art of overperformance

At the other end of the documentation continuum lie books. Remember those? While I may not have purchased a tech book for years, many thousands of other people do it all the time. In fact, at least in the short term, the technology publishing industry seems remarkably healthy.

The better traditional publishers will subject a book proposal to very close analysis before concluding that the idea makes sense and that there are enough readers interested to make it worthwhile. Once the writing begins, they’ll throw layers and layers of editors and reviewers at every stage of a book’s production. And when they’ve run out of editors, they’ll stage an editorial board review to make sure it wasn’t all a terrible mistake.

That’s how my editors at Manning work. And it’s also quite similar to the process I go through producing my video courses at Pluralsight.

When it’s done properly, the system creates checkpoints at the theme, style, chapter, and even paragraph levels, asking whether this element is needed, is presented as well as it can be, and will fit properly into the greater vision. These checkpoints make for great books, but they tend to be very expensive.

Is it overdone? Sometimes. Is the full-blown multi-level editorial system going to be affordable for web-based documentation projects? Perhaps not always.

But creating high-quality, readable, and well-organized documentation is a significant business need for many companies, so it would probably be a really good idea for them to at least submit what they’ve already got to a thorough audit by someone with experience, technical knowledge, and – most important of all – objectivity. The odds are, that will lead to a far more useful documentation product. And yes: documentation is also a product.

April 20, 2016

How do you Learn New Technologies?

I can’t prove this, but I suspect that most IT and developer types tend to work under pressure. Those folks are either in the middle of a big project with a looming deadline (or a recent catastrophic crash), or they’re struggling to learn a whole new technology. Either way, they’re looking to master the material as soon as possible.

Broadly speaking, there are three categories of training content: product documentation (like the man files that come with Linux programs), learn-from-doing user guides, and in-depth (700+ page) books that are heavy enough to substitute for military ordinance (if necessary). Of course, there are loads of resources that straddle two or more of those categories, but I think this is a decent working taxonomy.

Broadly speaking, there are three categories of training content: product documentation (like the man files that come with Linux programs), learn-from-doing user guides, and in-depth (700+ page) books that are heavy enough to substitute for military ordinance (if necessary). Of course, there are loads of resources that straddle two or more of those categories, but I think this is a decent working taxonomy.

Now, each kind has both strengths and weaknesses. Product documentation tents to be complete, and often instantly accessible, but it can be difficult to find the information you’re after right now from the middle of an ocean of dozens or even hundreds of arguments and use-cases that don’t interest you right now. It’s also very hard to retain all the important details you might encounter when its presentation is so formulaic.

User guides – with their paste-this-here and paste-that-there style – are excellent at getting you to specific goals quickly, but they might sometimes leave out important background information. They might also be less useful if the case you’re working on right now is just a little bit different – or if the one you’ll be working on next week isn’t quite the same.

In-depth books can be just right for providing a topic’s full historical and technical context and – when well executed – for teaching the troubleshooting tools that will make it possible for you to attack and solve future challenges on your own. One thing these generally do not provide, however, is speed.

Naturally, there will probably be times when you’ll call on resources from each category…depending on your immediate need and on what’s available. But, in general, how do people tend to learn best?

Let me illustrate the question with an example from my own career. On the first day on a new job as a system administrator, my boss told me to start off by building my own workstation. He dictated to me the way it should be built and then added that I should configure it to get its NTP service from a local server. I smiled, nodded, and turned to go, while trying to remember what NTP stood for. Of course, once my panic subsided, I remembered having learned about NTP (it stands for Network Time Protocol, as it turns out) but, since I’d never actually installed and configured it before in the real world, I didn’t really know where to start.

Google gave me what I needed in no time at all and, within no more than ten minutes, my new workstation was happily synced with the outside world. So what kind of resource served my needs on that particular occasion? There’s no competition: the user guide. All I really needed was the name of the installation package:

sudo apt-get install ntp

..and after that, a quick read through the /etc/ntp.conf file told me everything I needed to know about things like servers, pools, and drift. It took a bit more research over the next few days to get me up to speed on the difference between stratum 1 and stratum 2 servers and jitter and insane time, but the initial hands-on experience taught me more than a dozen pages of abstract backgrounders.

Ok. Now if I were to write a chapter on NTP in a Linux administration guide, what should I include? Certainly, I would start with basic installation and configuration that would include setting up an NTP server (which is actually not a difficult task). What else? There’s plenty more on technical topics like jitter and drift that might prove useful some time down the line. And some people will definitely want to know about certain security weaknesses that have been historically associated with NTP. Perhaps it would also be fun and useful to create a guide to building a stratum 1 server using a Raspberry Pi and an old GPS device.

But by this time, though, I will have distracted a great many of my readers from their immediate goals, as they really only need to get NTP up and running. But, on the other hand, leaving out all the more arcane technical details might make it harder for them to reach the kind of level of understanding that will allow them to make smarter decisions in the future. But on the other other hand, can’t they just look that stuff up on line when it becomes necessary?

Three questions:

When designing a technical guide for a specific audience, which will be most efficient? Probably something that’s closer to the how-to-guide end of the spectrum.

Which might have the best long-term outcomes? More likely the full-service version.

If I aim to serve the greatest proportion of the population the greatest proportion of the time, which of these will work best?

What do you think?

April 5, 2016

Microsoft and Linux Bash: Window’s interesting new doorway

Who saw that one coming?

Last week’s announcement from Microsoft that Windows 10 is now able to run the Linux Bash interpreter shell natively within a virtualized image of Ubuntu was certainly a shocker. This, after all, is the same Microsoft that within living memory vigorously challenged the value of an open source operating system and the usefulness (and reliability) of its products.

But while the move might have been unexpected, it does make a lot of sense. Microsoft is making no secret of the fact that most serious app development – and especially web and cloud-based development – is happening with open source software tools and, in particular, within Linux. Even Microsoft’s own Azure cloud platform is more and more like a mainstream Linux shop. Now, if a developer is going to spend most of his day up to his elbows in Linux, how much sense does it make for him to do his work from a Windows PC? Sure, there are workarounds for most tasks, but who wants to live life as one long hack?

Now, don’t forget that developers tend to be both heavy PC users and active, trend-setting tech consumers. If your business sold an operating system – let’s call it Windows – and other products within its software ecosystem, then you would really want to attract as many members of that demographic as you can. All that is perfectly reasonable.

However, doorways tend to allow movement in both directions. If a native Windows Bash interpreter allows more open source developers to choose Windows as their home base, it will also offer Windows-only developers the opportunity to taste the power of Linux. Of course, that might not convince them to tear up their MS user licenses and embrace the Ubuntu desktop experience, but it will make it much more likely they’ll deploy their next apps directly to some kind of Linux environment.

However, doorways tend to allow movement in both directions. If a native Windows Bash interpreter allows more open source developers to choose Windows as their home base, it will also offer Windows-only developers the opportunity to taste the power of Linux. Of course, that might not convince them to tear up their MS user licenses and embrace the Ubuntu desktop experience, but it will make it much more likely they’ll deploy their next apps directly to some kind of Linux environment.

Which brings me to the shameless self-promotion paragraph. My recent Linux Server Skills for Windows Administrators course from Pluralsight is just the ticket for someone with admin skills, but on the “wrong” operating system. If you or someone you love is looking to open new doors, this one might help.

March 18, 2016

Technology books: short is the new long

You think you’ve got a lot to read for your work? A client who’s been having latency trouble with their e-commerce server sent me a database log file yesterday that contained more than 1.3 million lines of text.

Now as much as I’d just love to curl up in front of the fireplace and slowly savor the whole thing (the prose is truly a thing of beauty), I don’t think that’s realistic. Instead, I chose to use some of the Linux command line’s powerful text manipulation tools to filter out the information I needed. I can’t resist sharing the way I approached the data problem, and I’ll get to that in just a minute or two. But this also got me thinking a bit about how we process the oceans of information that often characterize our professional lives.

Technology Information Overload: am I part of the problem?

Last week I had a very pleasant conversation with my publisher at Manning Publications. I had just signed a contract with Manning to write a book called “Learn Bash in a Month of Lunches”, and the two of us were speaking for the first time. I mentioned that, for strategic reasons, some technology publishers try to put out books in the 700-800 page range – sometimes whether or not the content requires it. I’m not sure this is a conscious process, but I can say that I’ve seen some books that are way longer than they need to be.

My own recent “Teach Yourself Linux Administration” book is less than a third the length of any of its competitors. That’s not to say that the other books in this genre aren’t worth reading – the ones I’ve seen most definitely are – but that it’s also possible that you can plan a book to focus on just the critical information that your readers will almost always need, and guide them to research some of the less common details on their own. You know, using that Internet thingy that they all seem to have.

In other words: short is the new long.

Now, let’s get back to my data problem.

Filtering large data stores

The log file contains records of requests against a large MySQL database. I quickly noticed that the second line of each record had a “Query_time:” value, usually of around 0.5 seconds or lower. I did, however, see some values that were higher than 1.0 seconds, and I thought I should try to find out just how high they went. Rather than visually scanning through screen after screen of text hoping to find something, I turned the problem over to cat (the Linux tool for reading text streams) and grep (for filtering).

The log file contains records of requests against a large MySQL database. I quickly noticed that the second line of each record had a “Query_time:” value, usually of around 0.5 seconds or lower. I did, however, see some values that were higher than 1.0 seconds, and I thought I should try to find out just how high they went. Rather than visually scanning through screen after screen of text hoping to find something, I turned the problem over to cat (the Linux tool for reading text streams) and grep (for filtering).

Here’s how it looked:

cat mysql-slow.log | grep Query_time

Now, of course, all that will do is print all the many thousands of lines in the file containing the string “Query_time”. I only wanted those lines with a value above, say, 3.0. I’m sure there are more straightforward ways of doing this, but I can’t see why I shouldn’t just run a second grep filter against my initial results. Now that will be a bit more complicated since, by default, grep interprets the dot (.) as a meta character and not as a simple dot. To get around that problem, I’ll run grep with the -F (fixed string) argument, and have it search for all occurrences of the number 3 followed by a dot (anything between 3.0 and 3.999, in other words).

cat mysql-slow.log.2016-03-15 | grep Query_time | grep -F '3.'

That gave me some useful output and it was something I could repeat for 4, 5, and 6 second responses (besides 1 and 2, of course). There were still way too many results to read, but I could at least use them to comfortably browse through the source records within the file and look for any patterns that might point to a recurring problem. Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately), I couldn’t see any obvious issues that would explain all the delays.

I then wondered just how many instances there were of each delay block. That was easy: simply pipe my grep output to wc, which will count the number of lines (and words and characters – but I didn’t care about those).

cat mysql-slow.log.2016-03-15 | grep Query_time | grep -F '3.' | wc

Here’s what I got:

Response times:

Number of instances (over 24 hours):

1-2 seconds

7076

2-3 seconds

2697

3-4 seconds

591

4-5 seconds

329

5-6 seconds

91

6-7 seconds

56

Those look like really big numbers. In fact, it means that the total number of requests that could not be completed in less than 1 second was 10,840. But of course, I needed to put that into context. How many requests were there in total on that day? That was easy, just grep for all Query_time lines and count them with wc.

cat mysql-slow.log.2016-03-15 | grep Query_time | wc

That one came to 333,257. Meaning the number of slow responses came to just over 3% of the total requests which, in the context of the problems the site had been experiencing, wasn’t significant.

February 29, 2016

Three great sandboxing tools for learning IT skills

The quickest way to learn some unfamiliar software technology is to dive right in and try it out. There will always be plenty of time to read the “Getting Started” page later.

But since installing new software usually involves messing with your own workstation’s configuration, it’s only a matter of time before your system stability is broken beyond repair. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with reformatting your drive and starting over from scratch – in fact, enjoying a nice fresh beginning every now and again can be liberating – but most of us would probably rather not have to rebuild our digital lives more than once a year or so.

If you can see yourself benefiting from access to fast-loading, isolated, and completely disposable working environments – known as sandboxes – where you can fearlessly test to your heart’s content, then here are some virtualization tools you’ll love.

LXC (LinuX Containers)

Working from a Linux terminal shell? Install the LXC userspace tool and run any number of independent (but networked) virtual machines on your own workstation. Besides two flavors of Ubuntu, my Ubuntu 14.04 system lets me choose from more than a dozen templates, including CentOS, Fedora, Gentoo, and OpenSUSE. All it takes is a single lxc-create command and about three minutes’ wait, and you’ll be inside a fully-functioning Linux environment.

You can install and remove packages (either manually or through the normal managed software repositories), edit configuration files, explore file systems and generally make yourself at home. Something went wrong? No problem. lxc-destroy is only as far away as your keyboard…as is another round of lxc-create.

Interested? Read my 60 second orientation tour of LXCs in the introduction to my “Teach Yourself Linux Administration and Prepare for the LPIC-1 Certification Exams” book.

LXC Strengths:

Speed (a container will often reboot in less time than it takes me to retype my password)

Light footprint (I’ve never come close to hitting a limit to the number of containers I can run at the same time).

LXC Weaknesses:

While you can run any operating system for which you have a template, you can only use those releases built for your host system’s kernel. If you need to use earlier or later releases, you’re out of luck.

Even if there are hacks, LXCs are not ideal for applications requiring a GUI desktop.

Will only run on Linux hosts (which, to be honest, I consider a feature rather than a weakness).

You have only limited control over the boot process (i.e., there’s no real GRUB implementation).

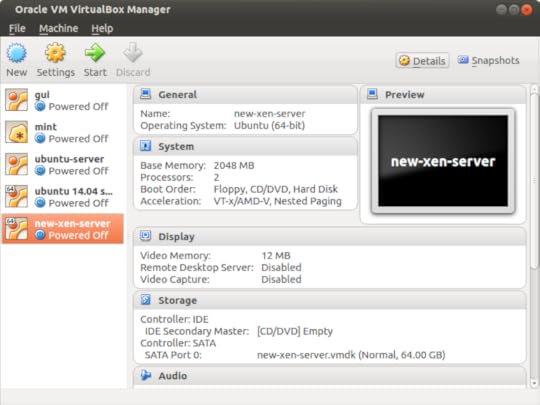

VirtualBox

Oracle’s free virtualization manager has become something of a standard in the computing world. It runs on just about anything (Linux, Windows, Mac) and supports a huge range of client OS images. VirtualBox provides a very close approximation of the full OS experience, but running safely in a window on your desktop.

VirtualBox Strengths:

You get a GUI interface (if necessary) and the ability to customize the installation process.

VirtualBox Weaknesses:

VB is not nearly as quick and light as LXC.

Networking can be a bit more complex.

Amazon EC2

Assuming that you’ve already got an Amazon AWS account, you can have a hosted EC2 (Elastic Compute Cloud) virtual machine – called an “instance” in AWS terms – up and running in the cloud in less than a minute. And if your AWS account is less than twelve months old, your instance could be covered under their free tier, so it won’t cost you anything either.

But why would you want to? Because this “sandbox” won’t be running in some cave deep in the dark recesses of your home PC, but at the heart of the busiest cloud on earth. Does your experimental project only make sense if you can test it out over the real Intertubes? Do you need to work with a very wide range of real-world security, storage, and data tools? Would you like to be SSH-ing into your own cloud server running one of hundreds of pre-built OS images designed for just about any general or specific use you can imagine within 90 seconds? Consider EC2.

Amazon EC2 Strengths:

Considering it’s not running on your hardware, it won’t slow you down.

Perfectly painless startup. Perfectly painless shutdown.

Huge range of freely-available OS images and storage, networking, and compute tools.

Amazon EC2 Weaknesses:

The life cycle process isn’t quite as quick as LXC, and the getting-started learning curve is a bit steeper.

This isn’t really a weakness but, since you’ll be in the real cloud, you have to be much more conscious of security and cost issues than on your own PC: AWS is a bit less of a sandbox.

February 14, 2016

Citizen Developers: where should they (and their tools) fit into the IT cycle?

How can you know that you’re doing something the best way if you haven’t even seen all the best tools available on the market? When it comes to “citizen developers,” the how, why, and what are obvious: it’s the when and which that’ll get you.

How can you know that you’re doing something the best way if you haven’t even seen all the best tools available on the market? When it comes to “citizen developers,” the how, why, and what are obvious: it’s the when and which that’ll get you.

I’ve been reading about the citizen developer movement (from the perspective of system administration: my primary focus). This covers a number of platforms designed to allow non-developers to translate their business needs into live software services using visual drag-and-drop tools and no – or very little – code. The pain point this tries to remove is a product of how frustrating and expensive it can be to get developers to deliver solutions to the actual problem you face. The frustration can sometimes come from how hard it can be for a non-business professional to accurately visualize the full scope of the need.

Getting your mind around large IT trends

When I come across an IT industry trend or paradigm with which I’m largely unfamiliar, properly understanding its importance and impact can be a struggle. I usually need to find some conceptual hook before it all starts to make sense to me.

As an example, I remember being a bit puzzled by configuration management tools like Chef and Puppet until I saw them as, essentially, formalized templates for defining and provisioning complex virtualized compute environments. Identical – or dynamically edited – copies can be deployed on demand by the service by simply reading the template script.

Wikipedia can be very helpful in such early-stage research, as its entry for a particular solution will often include a link to a page on the larger technology which, in turn, will provide a full definition and added examples. Once I get to that point, I will usually be able to quickly identify the main players and begin to zero in on each one’s unique strengths.

Where do citizen developers fit?

But “citizen development” hasn’t been so easy to define. Unlike “configuration management”, there doesn’t even seem to be a single way to describe the process. Besides “low coding,” I’ve also seen “drag-and-drop development tools,” “end-user application development (EUAD),” “non-coding development,” and, of course, citizen development. But the total number of Wikipedia pages devoted to any one of those descriptions currently sits at precisely zero. There seem to be a lot of players (like Intuit’s QuickBase, ViziApps and, of course, Salesforce’s Lightning App Builder for Force.com), but they’re not yet part of a recognized industry sector.

Now, I can hear you screaming: but aren’t they all PaaS (Platform as a Service) offerings? Well, yes. But then so are AWS’s Elastic Beanstalk, Heroku, and Salesforce.com itself. So PaaS is a bit too broad a definition to be useful.

Which isn’t to say that I don’t completely understand what the people who use these tools are ultimately after. I once worked for a company that was struggling to find the right integrated team-wide workflow management tool. There was nothing off-the-shelf that quite fit their needs, but the overhead of building a custom interface from scratch was simply out of reach. They might well have quickly solved their problems through one of those citizen development platforms had they pushed in that direction.

But, as I said, I’m having trouble getting the perspective I’d need to make intelligent choices over which platform might be best for a particular project, and what kinds of limitations and risks to watch out for. I’m not even 100% sure I haven’t completely missed an important provider.

What’s more important from a systems administration perspective, is how this kind of application development will effectively and securely live within the context of your total company infrastructure. Will you need to expose your data more than is wise to accommodate a citizen development project? Will it introduce vulnerabilities that might be hard to anticipate?

Whichever way you slice it, it’s important to be comfortable with your mastery of the medium…something I definitely still lack.

Has anyone already traveled down this route? Anything to share?

February 4, 2016

Tech training: using Internet search to get what you need

You’re really motivated this time. No, pumped is a better word. And you’re absolutely ready to invest some significant time and energy into reaching your learning goals. There are all kinds of reasons why you just have to master “that” skill. What is it: Python? HTML? Linux? You’re ready to rumble.

Got a great how-to book or video course to work with? Check. Suitable environment for some serious skills’ practice (because you know that it won’t work if you just sit back and passively watch or read)? Check. But what will you do when you run into trouble: if you’re going to spend a lot of time playing with an unfamiliar software platform, there will be setbacks and you will need help.

Who ya gonna call? Google search, of course. Here’s how to make that call work for you:

Use your problem to find a solution

Considering that countless thousands of people have worked with the same technology you’re now learning, the odds are very high that at least some of them have run into the same trouble as you. And at least a few of those will have posted their questions to an online user forum like Stack Overflow. The quickest way to get at look at the answers they received is to search using the exact language that you encountered.

Did your problem generate an error message? Paste exactly that text into your Google search engine. Were there any log messages? Find and post those, too.

How do you find log messages? On older Linux distributions, you could search through the /var/log/syslog file for events occurring around the time you encountered the problem. Alternatively, you could filter for a specific text string:

$ cat /var/log/syslog | grep filename.php

Some programs, like the Apache web server, have their own log files (/var/log/apache2/error.log on Ubuntu 14.04, for example). Details about most HTTP and PHP problems will eventually end up there.

On more recent Linux systems that use the Systemd process manager, logs are handled by journald. You can simply run journalctl and filter for a likely text string:

$ journalctl | grep filename.php

…or restrict your search to entries from within a specific time range:

journalctl --since "2016-02-14 14:25:00" --until "2016-02-14 14:35:00"

Once you find a likely-looking log entry, copy and paste it into Google and see what comes back.

Be precise

Google covers billions of pages of content from the entire public Internet, so your search results are bound to include a whole lot of false positives. That’s why you want to be as precise as possible. One powerful trick is to enclose your error message in quotation marks, telling Google that you’re looking for an exact phrase, rather than a single result containing all or most of the words somewhere on the page. However, you don’t want to be so specific that you end up narrowing your results down to zero.

Therefore, for an entry from the Apache error log like this:

[Fri Dec 16 02:15:44 2015] [error] [client 54.211.9.96] Client sent malformed Host header

…you should leave out the date and client IP address, because there’s no way anyone else got those exact details, and include only the “Client sent…” part in quotations:

"Client sent malformed Host header"

If that’s still too broad, consider adding the strings Apache and [error] outside the quotation marks:

"Client sent malformed Host header" apache [error]

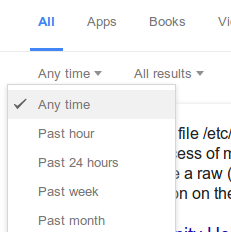

Be timely

Be timelyGoogle, through their “Search Tools” option, lets you narrow down your search by time. If your problem is specific to a relatively recent release version, restrict your search to just the last month or year.

Search in all the right places

Sometimes Google will do a better job searching through a large web site than the site’s own search engine (I’m looking at you: Government of Canada). If you feel the solution to your problem is likely to be somewhere on a particular site – like Stack Overflow’s admin cousin, Server Fault – but you can’t find it yourself, you can restrict Google results to just that one site:

"gss_accept_sec_context(2) failed:" site:serverfault.com

Know what you don’t want

Finally, if you see that many or all of the false positives you’re getting seem to include a single word (that is very unlikely to occur in the pages you’re looking for), exclude it with a dash:

writing scripts -movie

There’s really no end of helpful information waiting for you out there on the Internet. With just a little careful planning, you’ll be amazed how quickly you can get to it.

January 28, 2016

Linux training: it’s 2016 and you’re going to use a BOOK to teach yourself stuff?

You mean they’re still publishing books? And on Linux administration of all things?

When you consider just how inefficient books are at delivering knowledge when compared to digital networks, and when you consider just how many first rate and freely accessible how-to guides already exist out there, you’ve got to wonder why a guy like me would spend time writing a book. More than that, I would argue that there aren’t too many topics with more free documentation than Linux administration. Standing at the head of the Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) movement, the operating system is steeped in a culture that has always highly valued sharing, mentoring, and community.

So why did I do it? What possessed me to write a book guiding readers through their preparations for the LPIC-1 Linux Server Professional certification exams?

Well, first of all, it turns out that the book industry isn’t quite dead yet. A well written technical book on a particularly popular subject can still sell more than ten thousand copies, and that means there are still thousands of people who prefer to get the information they need the old fashioned way. And the fact that there are still more than a few active technical publishers, each putting out dozens of titles a year, suggests that there’s a healthy and diverse market.

But why should people spend money for material that’s mostly available free online? I think part of the answer is that not everyone is able or willing to do the digging it might take to get all of the answers they need through search engines and online forums. But it’s also about how each individual approaches learning. If, for instance, you absorb difficult technical information better when it’s well organized, then it may be worth it for you to spend a few bucks and take advantage of someone else’s research and organization. In the larger scheme of things, the cost of the book might be repaid many times over by the time and effort you save.

But, even so, you’ll have to be careful not to rely too heavily on the work of others. A million years ago (or so), when I was a high school teacher, I sometimes wondered if I wasn’t “too good” at what I did. What I meant was that if the way I presented the material to my students was too clear, I might be leaving them with nothing to do. Or, in other words, there may be no incentive for them to engage with the material in any active way. If students become nothing more than an audience, then they’re not really learning.

In such moments, I would simply stop talking and throw the ball back in their laps: “you figure out where this lesson was going and finish it yourselves.”

The case for book-based Linux training

That’s how I wrote my LPIC-1 book. All the exam objectives are covered and I don’t believe there’s a single question that’s not addressed but, unless you’ve got a photographic memory, you won’t possibly be able to master the material by just reading it. You’ll need to open up a Linux command line terminal and try everything out for yourself. You’ll need to make mistakes, spend frustrating hours digging yourself out, and then doing it one or two more times the right way. And you’ll need to attempt your own projects – perhaps following the suggested projects I included at the end of each chapter or, even better, things you need and want to do.

That’s how I wrote my LPIC-1 book. All the exam objectives are covered and I don’t believe there’s a single question that’s not addressed but, unless you’ve got a photographic memory, you won’t possibly be able to master the material by just reading it. You’ll need to open up a Linux command line terminal and try everything out for yourself. You’ll need to make mistakes, spend frustrating hours digging yourself out, and then doing it one or two more times the right way. And you’ll need to attempt your own projects – perhaps following the suggested projects I included at the end of each chapter or, even better, things you need and want to do.

To learn something, you need skin in the game.

That’s why Bootstrap IT’s motto is “Teach yourself…” And that’s why I think that this book – even though it’s less than a third the length of its competitors – might just have more value.

January 25, 2016

Using Ed Tech for Tech Ed

People don’t all learn new skills the same way. I create IT training videos for a living and you can take my word for it that there are all kinds of folks out there who really appreciate this kind of learning. But at the same time, I can tell you that others just haven’t got the patience to sit through long videos and prefer to quickly scan how-to articles or well-designed documentation for the information they need. How do I know that? Because, ironically, I’m very definitely a member of that club.

Similarly, when faced with large and complex topics, some look for information sources that are sequentially organized and that follow a simple-to-difficult narrative arc. Others just dive right in, grabbing whatever tools will quickly solve the most pressing roadblocks preventing them from reaching their long term goals.

Similarly, when faced with large and complex topics, some look for information sources that are sequentially organized and that follow a simple-to-difficult narrative arc. Others just dive right in, grabbing whatever tools will quickly solve the most pressing roadblocks preventing them from reaching their long term goals.

I’m not convinced that either approach will, by definition, produce better results, but I do know that the wealth of high-quality (and often free) resources made available through the Internet make them both possible.

So what?

Take another look at the title of this post. Ed tech – the way people normally use the term – describes technology used in education: flipped classrooms, smart assessment tools, OLPC, classroom-optimized Chromebooks, electric lights. That kind of thing. But tech ed is about learning technology. Even if they do overlap, the two aren’t the same at all.

I guess you could say that this site’s larger goal is to promote the integration of ed tech into tech ed so that, no matter how you learn best, you’ll find just the tools you need to reach your goals quickest. Whether it’s hands-on and deeply practical as my bootstrap methodology would have it, or through “blended books” that provide core information, but also encourage the use of other resources. The common denominator is that every student should become an active and intelligent participant in the educational process and should take responsibility for their own progress.

I hope to have more to say on that topic over the next while. But I also hope you’ll chime in with your own thoughts, too.

Be in touch,

January 24, 2016

Installing WordPress from the Ubuntu repository: here be filesystem bloat

Since this is the very first post on my shiny new Bootstrap-IT site blog, why not start things off with some of the joys and regrets that can accompany WordPress installations? I’ve built all kinds of WordPress sites but, until now, I’ve always done it the old fashioned way: Get the latest archive from the WordPress web site, upload it to my backend, create a database and user within MySQL (or, more recently, MariaDB), edit the wp-config.php file accordingly, copy the files to my document root directory, and set it all up from the browser configuration page.

This time, so I could rely on apt to keep me properly updated and patched, I thought I’d use the WP version from the Ubuntu 14.04 repository.

This time, so I could rely on apt to keep me properly updated and patched, I thought I’d use the WP version from the Ubuntu 14.04 repository.

In some ways, it’s a lot simpler. Just run apt-get:

sudo apt-get install wordpress

You will need to create a symbolic link between your document root directory and the WordPress files in /usr/share/, which should look something like this:

sudo ln -s /usr/share/wordpress /var/www/html/wordpress

Then you will extract the setup script:

sudo gzip -d /usr/share/doc/wordpress/examples/setup-mysql.gz

…and run the script specifying a database/user name (myname, in this hypothetical example), and the blog location. Choosing the right details can sometimes be a bit tricky. Hint: don’t include a dash (-) in your values.

sudo bash /usr/share/doc/wordpress/examples/setup-mysql -n myname localhost

Now point your browser to http://yourdomain.com/wordpress, set things up, and you’re done.

Except that you may find you’re not done. Even if the installation went smoothly, you’ll probably need to add a new theme and some plugins. If you’re planning to do that manually, you’ll have to do it on Ubuntu’s terms, and those terms are, to be charitable, a bit strange. Here’s the thing: for some reason, the setup script created directories containing WP files (or links to other directories) in as many as SIX different places! And, while they often look identical to each other, they sometimes seem to perform very different tasks – at least as far as I can see.

First of all, as I already mentioned, you will have created a symlink within your document root (usually var/www/html/) to /usr/share/wordpress/. The full set of working WP files will therefore appear in both of those locations.

My installation had another wp-content directory in /srv/www/ – this one containing only a directory named localhost – probably the result of my use of “localhost” when running the setup-mysql script. Then there’s a completely NEW set of plugins and themes, etc., in the wp-content directory that, for some reason, makes an appearance in /var/lib/wordpress/. And all that is besides the WP configuration and htaccess files in /etc/wordpress/.

Here’s where things got fun for me. To manually install a new theme, it turns out that I needed to upload it to the themes directory in /usr/share/wordpress/wp-content, and THEN create a symlink to it in /srv/www/wpcontent/localhost/themes/.

sudo ln -s /usr/share/wordpress/wp-content/themes/hiero /srv/www/wp-content/localhost/themes/hiero

Again, this might be due to my choice of “localhost” during setup, but it’s an odd set of hoops to jump through. And it’s made a whole lot more odd by the fact that this workaround will only work for themes, but not for plugins. I suppose those little guys wouldn’t be seen dead in same directory tree as themes. Instead, you’ll have to put their royal highnesses in /var/lib/wordpress/wp-content/plugins/.

I thought that I had a pretty good understanding of the Linux filesystem hierarchy standard – in fact, I’ve taught it a bunch of times as part of LPIC-1 certification preparation courses – but I’m not sure I understand what lies behind this tangled mess.

But what about the comfort of knowing that my package will be automatically kept up to date? The apt-get repo version is WordPress 3.8.2, while the direct-download version is 4.4.1. I absolutely love the Debian software repositories: their tireless good work makes access to really outstanding software both reliable and safe. But it’s not always the best choice.

The bottom line? The post you’re reading right now is part of a blog created using an up-to-date archive downloaded directly from the WordPress site.