Jennifer Hallock's Blog: Sugar Sun Series Extras, page 22

March 9, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term(s) #16: sungka and panguingue.

It's game time! Now that American football season is over, I need a new hobby. I love old school games, and you cannot get more old school than these two.

According to a fantastic site (linked below), one of the first Jesuit priests to arrive in the Visayan islands, Father José Sanchez, wrote in 1692 about sungka, called kunggit in parts of Panay. Sungka is a form of mancala, the "sowing" or "count and capture" games known across Asia. However, it is distinctive enough in its play that it has become a cultural touchstone for Filipino migrants and overseas contract workers.

Sungka is played on a carved wooden board with seven small "houses" (bahay) and one head (ulo) at either end. Small stones or cowrie shells are placed in the houses and then redistributed in game play. The Filipino version has two especially cool rules if you're a mancala enthusiast. For example, the first move is played by both players simultaneously, and the player who runs out of stones first gets the next turn. Second, you can capture your opponent's pieces across from you when you land in an empty house on your side. These changes make the game both more fair and more fun.

Beyond mere entertainment, sungka has been used to teach advanced mathematical concepts and to divine one's marriage prospects—so everything important in life. "The feminist poet and communication scientist Alison M. De La Cruz wrote in 1999 a one-woman performance called Sungka, which analyses the societal and family-related expectations in regard to gender-specific behavior and sexuality, race, and ethnic affiliation, by comparing it to a game of sungka." That sounds interesting, eh?

Panguingue is a 19th century rummy card game that uses eight traditional Spanish decks. You can make your modern deck a pseudo-Spanish one by removing the 8s, 9s, and 10s, and some folks also remove a set of spades to make 310 cards total. With these cards removed, the jack follows the 7 card. This game is similar to the in-hand rummy you might already know, but one interesting distinction is the fact that you can fold your entire hand in the first move before you bet. After that, you're in it until someone wins it. Wait a second, you say. Betting? Oh, did I not mention there can be lots of gambling involved? That's the exciting bit.

A great site on sungka: http://mancala.wikia.com/wiki/Sungka

A ongoing blog on panguingue: http://panguingue.blogspot.com/

(Creative commons licenses on photos: dbgg1979 and Colleen Sullivan. Both auto-color corrected.)

According to a fantastic site (linked below), one of the first Jesuit priests to arrive in the Visayan islands, Father José Sanchez, wrote in 1692 about sungka, called kunggit in parts of Panay. Sungka is a form of mancala, the "sowing" or "count and capture" games known across Asia. However, it is distinctive enough in its play that it has become a cultural touchstone for Filipino migrants and overseas contract workers.

Sungka is played on a carved wooden board with seven small "houses" (bahay) and one head (ulo) at either end. Small stones or cowrie shells are placed in the houses and then redistributed in game play. The Filipino version has two especially cool rules if you're a mancala enthusiast. For example, the first move is played by both players simultaneously, and the player who runs out of stones first gets the next turn. Second, you can capture your opponent's pieces across from you when you land in an empty house on your side. These changes make the game both more fair and more fun.

Beyond mere entertainment, sungka has been used to teach advanced mathematical concepts and to divine one's marriage prospects—so everything important in life. "The feminist poet and communication scientist Alison M. De La Cruz wrote in 1999 a one-woman performance called Sungka, which analyses the societal and family-related expectations in regard to gender-specific behavior and sexuality, race, and ethnic affiliation, by comparing it to a game of sungka." That sounds interesting, eh?

Panguingue is a 19th century rummy card game that uses eight traditional Spanish decks. You can make your modern deck a pseudo-Spanish one by removing the 8s, 9s, and 10s, and some folks also remove a set of spades to make 310 cards total. With these cards removed, the jack follows the 7 card. This game is similar to the in-hand rummy you might already know, but one interesting distinction is the fact that you can fold your entire hand in the first move before you bet. After that, you're in it until someone wins it. Wait a second, you say. Betting? Oh, did I not mention there can be lots of gambling involved? That's the exciting bit.

A great site on sungka: http://mancala.wikia.com/wiki/Sungka

A ongoing blog on panguingue: http://panguingue.blogspot.com/

(Creative commons licenses on photos: dbgg1979 and Colleen Sullivan. Both auto-color corrected.)

March 8, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #15: pandesal.

Pan de sal. Salt bread, literally. Think of them as delicious little rolls that go with anything. My husband made pulled pork shoulder for an American Fourth of July while we lived in the Philippines, and I realized the pandesal was born to be a slider. It was like they were made for our cross-cultural family extravaganza.

Of course, they weren't. They were made for the Almighty. The Spanish brought wheat flour to the Philippines because how else can you make a proper Christian host for communion without wheat? Early versions were cooked directly on the oven's red brick floor, according to food historian Felice Prudente Sta. Maria.

This method gave the bun a crisp hard shell.

Americans, though, introduced metal pans in the name of hygiene, it is said, resulting in the softer bun which still dominates today. (They also introduced a reliance on American wheat by eliminating tariffs on US goods coming into the Philippines while still charging tariffs on Philippine goods sent to the States. A good old double-standard, but I digress.) Either way, the original pandesals were larger: 9 to 15 centimeters long, 7 to 9 centimeters wide, and 4 to 6 centimeters thick (according to a source in Sta. Maria's fantastic book, The Governor-General's Kitchen).

These days, a typical pandesal is about the size of a fist—or the maximum amount of bread you can stuff in your mouth at one time. I've tried. Instead of salty, they also tend toward the sweet, some being made with milk or even condensed milk. (This is similar to a Portuguese sweet bread roll, probably an ancestor or cousin of the pandesal.) Finally, they are rolled around in bread crumbs before baking, which gives it a great texture.

They are lovely for dipping in Spanish tsokolate (see glossary term #5) or coffee or anything you want. They are considered by many as the national bread of the Philippines. When fresh and hot, they are manna from heaven.

(Creative commons licenses on photos: simply anne and whologwhy.)

Of course, they weren't. They were made for the Almighty. The Spanish brought wheat flour to the Philippines because how else can you make a proper Christian host for communion without wheat? Early versions were cooked directly on the oven's red brick floor, according to food historian Felice Prudente Sta. Maria.

This method gave the bun a crisp hard shell.

Americans, though, introduced metal pans in the name of hygiene, it is said, resulting in the softer bun which still dominates today. (They also introduced a reliance on American wheat by eliminating tariffs on US goods coming into the Philippines while still charging tariffs on Philippine goods sent to the States. A good old double-standard, but I digress.) Either way, the original pandesals were larger: 9 to 15 centimeters long, 7 to 9 centimeters wide, and 4 to 6 centimeters thick (according to a source in Sta. Maria's fantastic book, The Governor-General's Kitchen).

These days, a typical pandesal is about the size of a fist—or the maximum amount of bread you can stuff in your mouth at one time. I've tried. Instead of salty, they also tend toward the sweet, some being made with milk or even condensed milk. (This is similar to a Portuguese sweet bread roll, probably an ancestor or cousin of the pandesal.) Finally, they are rolled around in bread crumbs before baking, which gives it a great texture.

They are lovely for dipping in Spanish tsokolate (see glossary term #5) or coffee or anything you want. They are considered by many as the national bread of the Philippines. When fresh and hot, they are manna from heaven.

(Creative commons licenses on photos: simply anne and whologwhy.)

Published on March 08, 2016 14:18

•

Tags:

bread, glossary, pan-de-sal, pandesal, sugar-sun

February 27, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #14: Goo-goo.

Part of me does not want to post this, but you’re going to see the word in the book, so…Sugar Sun series glossary term #14: Goo-goo.

It’s a terrible word. Don’t use it. If you are too young to understand how offensive it is, just trust me. This racial slur was used widely by American soldiers, politicians, and civilians to denigrate Filipinos—and later Koreans and Vietnamese in a slight variation (gook). The word apparently was meant to mock Tagalog speakers with their heavy use of the letter g. (G is four times more frequent in Tagalog as it is in English, and is the third most common letter overall in the language.) However, I also read a different explanation in a children’s book of the time called Uncle Sam’s Boys, where it was claimed that the word came from Filipino revolutionaries pretending to be the “good” guys around American soldiers, and somehow “good-good” got shortened. (Yes, they used racial slurs in a children’s book. When I say that racism popped up everywhere in my research, I really mean it.)

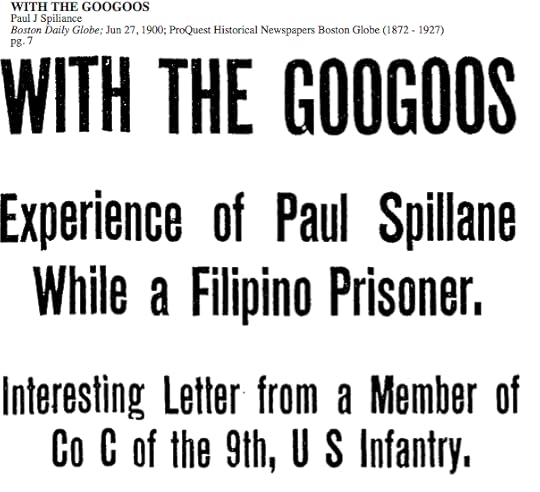

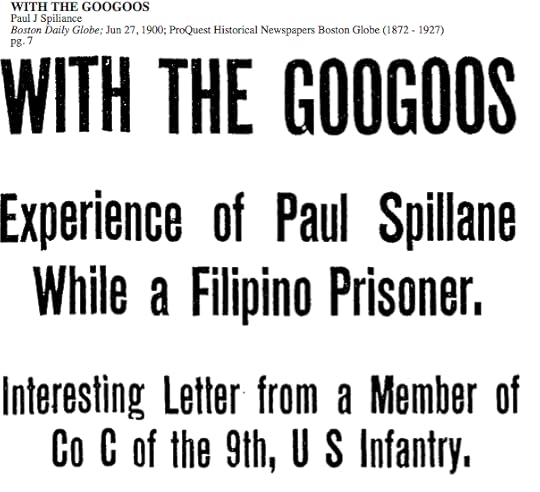

Of course, no matter how the Americans came up with the word, the fact that they used it with such vitriol is all on them. This brings up a problem for my writing. How accurate should a historical romance novel be? Americans called Filipinos everything from the N-word to the G-word and more, and they even published these words in their newspapers. (See the headline from the Boston Globe below.) I could have ignored this record, but sanitizing history does not help those who were oppressed. As I recently heard author Wes Moore say: “The worst thing we can take away from a tragedy is to pretend the tragedy did not happen.” If learning about how Americans treated Filipinos makes you angry, then good.

How blind were those Americans to their own small-mindedness? This may help you understand: English did not even have a word for racism yet. There was no single term to convey the idea that discrimination based upon race was wrong—not until 1903, and it was not widely used until the 1930s. There was a similar-sounding word, racialism, which was the pseudo-scientific study of traits according to race—as if eugenics was the most natural thing in the world. Yikes.

Therefore, my characters do not come to an epiphany about racial harmony because that would be wildly anachronistic. Georgie falls in love with a man based on his qualities as a man. Javier falls in love with a woman based on her qualities as a woman. That will have to be enough. In fact, Georgie’s relationship with Javier is more complicated than race. It involves class, too. Javier is more wealthy, more cultured, more connected, and more powerful than she is. Javier also has the edge on education and certainly on languages. They do not occupy the same social sphere, no, but it is hard to say whose sphere is higher. The irony of American “benevolent assimilation” (read: “civilizing mission”) is that many of the Yankees Javier meets are less “civilized” than he is. Sometimes he cannot help but point that out to them. (No, it doesn’t go well.)

The truly sad part of this all is that I borrowed the most outrageous insults straight from period sources. I found it distasteful to make these things up, so I relied upon distasteful people to do it for me. Maybe readers will mistakenly believe that I believe these things, but I hope not. Really, I did tone it down. The serious historian inside of me says this book is all unicorns and rainbows, but there is only so much my romantic side can stomach.

On Twitter recently, an author said that she received a two-star ratings on Amazon for NOT warning readers of a non-white main character. Clearly, racism is still out there. I just hope people understand that accepting something is true to history does not make it the historian’s preference.

It’s a terrible word. Don’t use it. If you are too young to understand how offensive it is, just trust me. This racial slur was used widely by American soldiers, politicians, and civilians to denigrate Filipinos—and later Koreans and Vietnamese in a slight variation (gook). The word apparently was meant to mock Tagalog speakers with their heavy use of the letter g. (G is four times more frequent in Tagalog as it is in English, and is the third most common letter overall in the language.) However, I also read a different explanation in a children’s book of the time called Uncle Sam’s Boys, where it was claimed that the word came from Filipino revolutionaries pretending to be the “good” guys around American soldiers, and somehow “good-good” got shortened. (Yes, they used racial slurs in a children’s book. When I say that racism popped up everywhere in my research, I really mean it.)

Of course, no matter how the Americans came up with the word, the fact that they used it with such vitriol is all on them. This brings up a problem for my writing. How accurate should a historical romance novel be? Americans called Filipinos everything from the N-word to the G-word and more, and they even published these words in their newspapers. (See the headline from the Boston Globe below.) I could have ignored this record, but sanitizing history does not help those who were oppressed. As I recently heard author Wes Moore say: “The worst thing we can take away from a tragedy is to pretend the tragedy did not happen.” If learning about how Americans treated Filipinos makes you angry, then good.

How blind were those Americans to their own small-mindedness? This may help you understand: English did not even have a word for racism yet. There was no single term to convey the idea that discrimination based upon race was wrong—not until 1903, and it was not widely used until the 1930s. There was a similar-sounding word, racialism, which was the pseudo-scientific study of traits according to race—as if eugenics was the most natural thing in the world. Yikes.

Therefore, my characters do not come to an epiphany about racial harmony because that would be wildly anachronistic. Georgie falls in love with a man based on his qualities as a man. Javier falls in love with a woman based on her qualities as a woman. That will have to be enough. In fact, Georgie’s relationship with Javier is more complicated than race. It involves class, too. Javier is more wealthy, more cultured, more connected, and more powerful than she is. Javier also has the edge on education and certainly on languages. They do not occupy the same social sphere, no, but it is hard to say whose sphere is higher. The irony of American “benevolent assimilation” (read: “civilizing mission”) is that many of the Yankees Javier meets are less “civilized” than he is. Sometimes he cannot help but point that out to them. (No, it doesn’t go well.)

The truly sad part of this all is that I borrowed the most outrageous insults straight from period sources. I found it distasteful to make these things up, so I relied upon distasteful people to do it for me. Maybe readers will mistakenly believe that I believe these things, but I hope not. Really, I did tone it down. The serious historian inside of me says this book is all unicorns and rainbows, but there is only so much my romantic side can stomach.

On Twitter recently, an author said that she received a two-star ratings on Amazon for NOT warning readers of a non-white main character. Clearly, racism is still out there. I just hope people understand that accepting something is true to history does not make it the historian’s preference.

January 15, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #13: Kristo.

Sundays and saints’ days were the only days when cockfighting was legal under the Spanish—and since this weekend happens to be both (see term #12, Sinulog), it is a good time to introduce the kristo, or all-around bookie and cashier. A kristo brokers bets by pointing at the two opposing parties, arms outstretched like Christ on the cross, hence kristo. Hand signals indicate the amount of the bet and other details. You had better know what you’re doing and be able to choose fast.

I don’t think I could—both because of my general indecisiveness, and because I have pet chickens now and have become squeamish about the whole enterprise. I know that many prizewinning cockerels in the Philippines are very well cared for birds. Until the fight itself, these birds live far better than their factory-farmed chicken nugget brothers in America. What can I say? My poultry ethics are convenient, not consistent.

Nevertheless, I do want to see a kristo in action. These men manage to keep track of dozens of bets in each fight, all in different amounts, all in quick succession, and without the use of a computer or even pen and paper. In fact, kristos in the early American period were often illiterate—which, if you think about it, makes sense. Literacy ruined memory. Our forefathers learned poems, songs, stories, histories, and religious revelations by rote, yet I can’t keep track of my grocery list without Google Keep on my Android.

Pathetic, the kristo says. Pathetic.

By the way, when the kill-joy Americans arrived, they tried to replace cockfighting with baseball. Though the great American pastime caught on—shout out to the Manila-based champions of the 2012 Big League Softball World Series—it never replaced cockfighting.

Creative commons photo, "Taking Bets," by Paul on Flickr.

I don’t think I could—both because of my general indecisiveness, and because I have pet chickens now and have become squeamish about the whole enterprise. I know that many prizewinning cockerels in the Philippines are very well cared for birds. Until the fight itself, these birds live far better than their factory-farmed chicken nugget brothers in America. What can I say? My poultry ethics are convenient, not consistent.

Nevertheless, I do want to see a kristo in action. These men manage to keep track of dozens of bets in each fight, all in different amounts, all in quick succession, and without the use of a computer or even pen and paper. In fact, kristos in the early American period were often illiterate—which, if you think about it, makes sense. Literacy ruined memory. Our forefathers learned poems, songs, stories, histories, and religious revelations by rote, yet I can’t keep track of my grocery list without Google Keep on my Android.

Pathetic, the kristo says. Pathetic.

By the way, when the kill-joy Americans arrived, they tried to replace cockfighting with baseball. Though the great American pastime caught on—shout out to the Manila-based champions of the 2012 Big League Softball World Series—it never replaced cockfighting.

Creative commons photo, "Taking Bets," by Paul on Flickr.

January 9, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #12: Sinulog.

It's fiesta time, people! You thought the holidays were over, but in Cebu they are just beginning. All you need is some nutmeg, a drum, and a statue of Baby Jesus.

The nutmeg is a nod to history. Spices are why Magellan sailed to Cebu. In medieval Europe, this stuff was more valuable than its weight in gold. It not only tasted good, it warded off the bubonic plague, too! (Don’t try that at home, folks.) By the early 1500s, the Portuguese had locked up the eastern trading routes around Africa and India, leaving the Spanish to sail west off the edge of the world. No, just kidding. Anyone with education back then knew the world was round, but they didn’t know a good route around the Americas. Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan told King Charles I of Spain that he could find a western passage for the right price. It took him two years to make good on that promise—two years of being chased by the angry Portuguese navy; surviving mutinies, storms, starvation, and winter; and crossing the un-pacific Pacific Ocean. Finally, Magellan and his remaining crew arrived in Cebu in 1521.

There Magellan managed to convince the raja of Cebu, his harem, and the entire settlement to convert to Christianity. The people already had their own idols they danced to, but they pledged to put those away in favor of a present from Magellan: the Santo Niño, or Child Jesus. Magellan even offered to make Christianity work for his new ally, Raja Humabon, now called Don Carlos. Carlos pointed out that the raja of Mactan, a small neighboring island, was spurning the right and true religion. Off Magellan went to fight Lapu-Lapu with an unnecessarily small number of Spanish troops: forty-nine to Lapu-Lapu’s fifteen hundred. Magellan must have never heard MacArthur’s (or the Princess Bride’s) twentieth century warning to “never fight a land war in Asia.” Intending to be a Christian miracle worker, he died a Christian martyr. His body was not found after being torn apart by the Mactan defenders, adding to Lapu-Lapu’s legend as a true nationalist hero. He even has a delicious fish (local grouper) named after him. Very cool.

The Spaniards staying with Don Carlos overstayed their welcome, possibly raping some of the raja’s women after a fiesta (not a tradition of Sinulog). A few of Magellan’s crew, under the captaincy of Juan Sebastian del Cano, made it back to Spain after circumnavigating the globe for the first time. This was the last the native Filipinos saw of the Spanish for a while. Other Spaniards made it to the southern tip of Mindanao long enough to name the islands Las Islas Felipinas in honor of Phillip II, but it took 43 years for Miguel Lopez de Legaspi to make it to Cebu. What did he see there? People dancing to the Santo Niño! (Probably among other idols, but he did not emphasize that part.) A miracle!

Soon came the friars, and Catholicism was in the Philippines to stay. Every town’s church is named after a saint, and that saint’s festival day is celebrated with a procession of the wooden santo statue along the main thoroughfare. In Cebu the sinulog, or “current of the river,” was also danced to please the Santo Niño during his parade. Native drums, gongs, and frenzied movement resemble the pagan festival it once was. Sometime in the 1980s Cebu’s Sinulog became big business, and people travel from all over the world to see it. The schedule for this year’s event includes an entire month’s worth of events, from a historical recreation of Don Carlos’s baptism to a singing competition (Sinulog Idol, of course!). The Santo Niño also travels round trip to Mactan (Lapu-Lapu would not be happy, I think) the day before the big parade, which itself lasts about twelve hours. The costumes are out of sight. In comparison, Americans have no idea how to throw a parade. Even the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade cannot beat this, especially since Sinulog is a regional celebration. I’ve not even mentioned Quiapo's Black Nazarene, Iloilo’s Dinagyang, Bacolod’s Masskara, Kalibo’s Ati-Atihan, and so on.

If you live in Cebu, I hope that you were not planning to drive anywhere this week or next. Happy Sinulog!

(Creative commons licenses on photos: Billy Lopue, Rusty Ferguson, J3SSL33, Kenneth Gaerlan)

The nutmeg is a nod to history. Spices are why Magellan sailed to Cebu. In medieval Europe, this stuff was more valuable than its weight in gold. It not only tasted good, it warded off the bubonic plague, too! (Don’t try that at home, folks.) By the early 1500s, the Portuguese had locked up the eastern trading routes around Africa and India, leaving the Spanish to sail west off the edge of the world. No, just kidding. Anyone with education back then knew the world was round, but they didn’t know a good route around the Americas. Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan told King Charles I of Spain that he could find a western passage for the right price. It took him two years to make good on that promise—two years of being chased by the angry Portuguese navy; surviving mutinies, storms, starvation, and winter; and crossing the un-pacific Pacific Ocean. Finally, Magellan and his remaining crew arrived in Cebu in 1521.

There Magellan managed to convince the raja of Cebu, his harem, and the entire settlement to convert to Christianity. The people already had their own idols they danced to, but they pledged to put those away in favor of a present from Magellan: the Santo Niño, or Child Jesus. Magellan even offered to make Christianity work for his new ally, Raja Humabon, now called Don Carlos. Carlos pointed out that the raja of Mactan, a small neighboring island, was spurning the right and true religion. Off Magellan went to fight Lapu-Lapu with an unnecessarily small number of Spanish troops: forty-nine to Lapu-Lapu’s fifteen hundred. Magellan must have never heard MacArthur’s (or the Princess Bride’s) twentieth century warning to “never fight a land war in Asia.” Intending to be a Christian miracle worker, he died a Christian martyr. His body was not found after being torn apart by the Mactan defenders, adding to Lapu-Lapu’s legend as a true nationalist hero. He even has a delicious fish (local grouper) named after him. Very cool.

The Spaniards staying with Don Carlos overstayed their welcome, possibly raping some of the raja’s women after a fiesta (not a tradition of Sinulog). A few of Magellan’s crew, under the captaincy of Juan Sebastian del Cano, made it back to Spain after circumnavigating the globe for the first time. This was the last the native Filipinos saw of the Spanish for a while. Other Spaniards made it to the southern tip of Mindanao long enough to name the islands Las Islas Felipinas in honor of Phillip II, but it took 43 years for Miguel Lopez de Legaspi to make it to Cebu. What did he see there? People dancing to the Santo Niño! (Probably among other idols, but he did not emphasize that part.) A miracle!

Soon came the friars, and Catholicism was in the Philippines to stay. Every town’s church is named after a saint, and that saint’s festival day is celebrated with a procession of the wooden santo statue along the main thoroughfare. In Cebu the sinulog, or “current of the river,” was also danced to please the Santo Niño during his parade. Native drums, gongs, and frenzied movement resemble the pagan festival it once was. Sometime in the 1980s Cebu’s Sinulog became big business, and people travel from all over the world to see it. The schedule for this year’s event includes an entire month’s worth of events, from a historical recreation of Don Carlos’s baptism to a singing competition (Sinulog Idol, of course!). The Santo Niño also travels round trip to Mactan (Lapu-Lapu would not be happy, I think) the day before the big parade, which itself lasts about twelve hours. The costumes are out of sight. In comparison, Americans have no idea how to throw a parade. Even the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade cannot beat this, especially since Sinulog is a regional celebration. I’ve not even mentioned Quiapo's Black Nazarene, Iloilo’s Dinagyang, Bacolod’s Masskara, Kalibo’s Ati-Atihan, and so on.

If you live in Cebu, I hope that you were not planning to drive anywhere this week or next. Happy Sinulog!

(Creative commons licenses on photos: Billy Lopue, Rusty Ferguson, J3SSL33, Kenneth Gaerlan)

January 5, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #11: Lechon.

Vegetarians beware.

To be honest, I've known very few Filipino vegetarians, though maybe it's simply the company I keep. This does not mean that I'm a huge fan of roast suckling pig, or lechon, but I see its attraction.

To appreciate the Filipino national dish, you have to be willing to see your animal go from farm to table right in front of you. To spare you that privilege, I've used a photo of how the lechon would likely be served to you, cut right off the pig after being roasted on a spit for hours. (Creative commons license by Scott Mindeaux.)

Typically, the younger the piglet, the more fatty and therefore the more prized the lechon. Personally, I prefer more meaty lechon, which my barkada (my peeps) took as evidence of my poor taste. I let them have the lechon while I slyly ate all the kinilaw na tanigue (ceviche Spanish mackerel) or fresh lumpia (spring rolls), among other dishes.

The lesson is this: do not disparage Filipino food. Anthony Bourdain has visited the islands twice—most recently this past month—and he called the local lechon the "best pig ever."

To be honest, I've known very few Filipino vegetarians, though maybe it's simply the company I keep. This does not mean that I'm a huge fan of roast suckling pig, or lechon, but I see its attraction.

To appreciate the Filipino national dish, you have to be willing to see your animal go from farm to table right in front of you. To spare you that privilege, I've used a photo of how the lechon would likely be served to you, cut right off the pig after being roasted on a spit for hours. (Creative commons license by Scott Mindeaux.)

Typically, the younger the piglet, the more fatty and therefore the more prized the lechon. Personally, I prefer more meaty lechon, which my barkada (my peeps) took as evidence of my poor taste. I let them have the lechon while I slyly ate all the kinilaw na tanigue (ceviche Spanish mackerel) or fresh lumpia (spring rolls), among other dishes.

The lesson is this: do not disparage Filipino food. Anthony Bourdain has visited the islands twice—most recently this past month—and he called the local lechon the "best pig ever."

January 4, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #10: Thomasite.

In August 1901 over five hundred American teachers arrived in Manila aboard the USAT Thomas, and the term "Thomasite" was born. A strategy begun by the Army to "pacify" the islands, the American colonial authorities established a coeducational, secular, public school system throughout the Philippines. Often seen as the best thing the Americans did in the islands, it is not without its critics. Here's the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The Good: Many Thomasites were flexible, adventurous people who truly loved their students and their host towns. Some never left. I modeled Georgina Potter on some of these people, including Mary Fee, who will come up again. The best, most democratic administrator was David Barrows, who emphasized solid academic subjects like reading, writing, and arithmetic so that Filipinos could find professions, not just jobs. He also implemented a test-based scholarship system to American universities, which will be the topic of another post. Barrows opened more schools and trained Filipino teachers to take them over—something now termed sustainable development.

The Bad: In his time, Barrows was considered a failure because Filipino students were not achieving to the level of Americans in standardized testing—yes, back then we were just starting to "teach to tests." A thinking person might understand that this is because Filipino students were being taught in a foreign language. This is a good time to mention that everything was taught in English. Why? The Americans said that Filipinos had not learned enough Spanish to justify that medium, and the local languages were too many and too varied to be practical. And, let's face it: Americans, particularly the Easterners and Midwesterners who came to the Philippines, only spoke English. Moreover, they already had the textbooks printed. Hence, Filipino boys and girls were learning poems about snowflakes. Huh? Fortunately, Mary Fee and others rewrote some of these early readers with local themes, proving that not all Yankees are idiots.

The Ugly: The next superintendent after Barrows returned the educational system to its original focus: industrial education, based on what were then called "negro schools" in the States. White (really his name) thought that Filipinos should be taught "practical subjects" like carpentry and gardening, as well as "character training" like cleanliness and conduct. (Such prejudice was so prevalent at the time that English-speakers had not yet coined the word "racism." It was simply the norm.) And then there were some individual Americans who, in the words of Javier Altarejos, were "unfit for travel abroad." Harry Cole, stationed in Palo, Leyte, wrote that "when I get home, I want to forget about this country and people as soon as possible. I shall probably hate the sight of anything but a white man the rest of my life." Archie Blaxton channels good ol' Harry quite a lot. Fortunately or unfortunately, I did not have to make up horrible, racist stuff for my characters to say. I just looked up what real Americans did say. It was not encouraging.

In the end, the educational program was successful in making Filipinos believe that a brighter future was possible under the Americans—not fighting the Americans. Whether this was cynical manipulation by the colonial government or a sincere intention to do good abroad, that's up to you. From my research, the two were tied up together in what President McKinley termed "Benevolent Assimilation." Many Filipinos did like the schools, and they certainly respected their teachers. Most importantly, some families managed to do what Barrows wanted: to "destroy that repellent peonage or bonded indebtedness" in which they found themselves. And the Thomasites gave me great plot ideas, so I'm not complaining.

The Good: Many Thomasites were flexible, adventurous people who truly loved their students and their host towns. Some never left. I modeled Georgina Potter on some of these people, including Mary Fee, who will come up again. The best, most democratic administrator was David Barrows, who emphasized solid academic subjects like reading, writing, and arithmetic so that Filipinos could find professions, not just jobs. He also implemented a test-based scholarship system to American universities, which will be the topic of another post. Barrows opened more schools and trained Filipino teachers to take them over—something now termed sustainable development.

The Bad: In his time, Barrows was considered a failure because Filipino students were not achieving to the level of Americans in standardized testing—yes, back then we were just starting to "teach to tests." A thinking person might understand that this is because Filipino students were being taught in a foreign language. This is a good time to mention that everything was taught in English. Why? The Americans said that Filipinos had not learned enough Spanish to justify that medium, and the local languages were too many and too varied to be practical. And, let's face it: Americans, particularly the Easterners and Midwesterners who came to the Philippines, only spoke English. Moreover, they already had the textbooks printed. Hence, Filipino boys and girls were learning poems about snowflakes. Huh? Fortunately, Mary Fee and others rewrote some of these early readers with local themes, proving that not all Yankees are idiots.

The Ugly: The next superintendent after Barrows returned the educational system to its original focus: industrial education, based on what were then called "negro schools" in the States. White (really his name) thought that Filipinos should be taught "practical subjects" like carpentry and gardening, as well as "character training" like cleanliness and conduct. (Such prejudice was so prevalent at the time that English-speakers had not yet coined the word "racism." It was simply the norm.) And then there were some individual Americans who, in the words of Javier Altarejos, were "unfit for travel abroad." Harry Cole, stationed in Palo, Leyte, wrote that "when I get home, I want to forget about this country and people as soon as possible. I shall probably hate the sight of anything but a white man the rest of my life." Archie Blaxton channels good ol' Harry quite a lot. Fortunately or unfortunately, I did not have to make up horrible, racist stuff for my characters to say. I just looked up what real Americans did say. It was not encouraging.

In the end, the educational program was successful in making Filipinos believe that a brighter future was possible under the Americans—not fighting the Americans. Whether this was cynical manipulation by the colonial government or a sincere intention to do good abroad, that's up to you. From my research, the two were tied up together in what President McKinley termed "Benevolent Assimilation." Many Filipinos did like the schools, and they certainly respected their teachers. Most importantly, some families managed to do what Barrows wanted: to "destroy that repellent peonage or bonded indebtedness" in which they found themselves. And the Thomasites gave me great plot ideas, so I'm not complaining.

January 3, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #9: Carabao.

The carabao is the national animal of the Philippines. It's a good choice because this beast of burden can do everything. It can haul a house's worth of goods (up to 3500 kilos or 7700 pounds), turn a mill stone, or carry several passengers for hours. It is your pick-up truck, tractor, and engine all in one. A contemporary observer wrote that the carabao was "patient and tractable so long as he can enjoy a daily swim. If cut off from water the beast becomes irritable [and] will attack men or animals and gore them with its sharp horns." Americans were a bit dramatic, of course. They resented the carabao for clogging carriage traffic as it lumbered through Manila at two miles per hour.

The true test of the carabao's usefulness is that there are still 3.2 million in the Philippines. According to a 2005 United Nations report, "99 percent belong to small farmers that have limited resources, low income, and little access to other economic opportunities." At the dawn of the 20th century, though, every farmer and hacendero relied upon the carabao, which is why the rinderpest epidemic of 1901 hurt the islands so badly. This was one of Javier Altarejos's biggest problems at the beginning of the book: finding the money to replace his herd.

The true test of the carabao's usefulness is that there are still 3.2 million in the Philippines. According to a 2005 United Nations report, "99 percent belong to small farmers that have limited resources, low income, and little access to other economic opportunities." At the dawn of the 20th century, though, every farmer and hacendero relied upon the carabao, which is why the rinderpest epidemic of 1901 hurt the islands so badly. This was one of Javier Altarejos's biggest problems at the beginning of the book: finding the money to replace his herd.

Sugar Sun series glossary term #8: Insurrecto.

Though the conflict began over events in Cuba, America fought its first battle of the Spanish-American War in Manila. Historians debate what President McKinley's intentions were—did he want to take the Philippines in its entirety, just keep Manila, or defeat Spain and leave? But, as they say, "appetite comes with eating." Once the Americans had Manila, they wanted all the islands. Only problem? The Philippine revolutionaries who helped defeat the Spanish did not want the Americans to stay—and they controlled most of the rest of the country.

Instead of calling what followed a war—assuming two equal adversaries—the Americans called it the Philippine Insurrection—with only one legitimate authority. (The Spanish sold the islands to the Americans for $20 million in December 1898, which was the basis of their legal claim. On what authority the Spanish sold the Philippines, that is another question.) So instead of calling the Filipinos revolutionaries, patriots, or nationalists, they called them insurgents, bandits, and ladrones. (The last two are the same thing, the latter in Spanish.) The favorite American term, though, was insurrecto (insurrectionist).

Now the conflict is called the Philippine-American War, and it officially lasted from 1899 to 1902, though hostilities did not fully end until 1913. Despite the name change, Filipinos after 1899 are rarely called revolutionaries, even in the more balanced American textbooks. In my books, I use the term insurrecto whenever Americans are speaking because that term is true to the period. It is not a political statement (as you could probably tell by the tone of my posts).

Instead of calling what followed a war—assuming two equal adversaries—the Americans called it the Philippine Insurrection—with only one legitimate authority. (The Spanish sold the islands to the Americans for $20 million in December 1898, which was the basis of their legal claim. On what authority the Spanish sold the Philippines, that is another question.) So instead of calling the Filipinos revolutionaries, patriots, or nationalists, they called them insurgents, bandits, and ladrones. (The last two are the same thing, the latter in Spanish.) The favorite American term, though, was insurrecto (insurrectionist).

Now the conflict is called the Philippine-American War, and it officially lasted from 1899 to 1902, though hostilities did not fully end until 1913. Despite the name change, Filipinos after 1899 are rarely called revolutionaries, even in the more balanced American textbooks. In my books, I use the term insurrecto whenever Americans are speaking because that term is true to the period. It is not a political statement (as you could probably tell by the tone of my posts).

Published on January 03, 2016 09:14

•

Tags:

glossary, insurrecto, mckinley, philippine-american-war, spanish-american-war, sugar-sun, treaty-of-paris

Sugar Sun series glossary term #7: Hacendero.

When I first chose to write a Fil-Am romance, I had to make my hero a sugar baron to best fit the model of popular Regency historical romance. There are some superficial similarities between my fictional hacienda owner, Javier Altarejos, and a fictional English gentleman, like Jane Austen's Fitzwilliam Darcy. Both came from wealth. Javier grew up in the 1880s and 1890s, when Negros ruled the Philippine (and European) sugar markets. His parents traveled to Europe in the off-season, and they brought back champagne and horses. He grew up in a beautiful local-style mansion, attended by maids, cooks, and nannies. Darcy's income of ten thousand pounds a year was 300 times the average income of the day—some of which could have come from West Indies plantations. And no matter what production of Pride and Prejudice you see, Pemberley is singularly impressive.

However, the true model for Javier (other than Enrique Iglesias, above) was less Darcy and more John Thornton of Elizabeth Gaskell's North and South. (See the 4-part BBC series. You won't be disappointed.) By the time Javier inherits Hacienda Altarejos, the boom times are gone. He has to deal with war (several of them), closed ports, labor shortages, rinderpest and cholera epidemics, drought, and American trade restrictions. Moreover, without a sugar central, his product is no longer the best available. Javier is a good man doing the best he can to keep a major economic enterprise going in tough times. Hacenderos had a reputation of getting rich off the work of their wage laborers, much like the bourgeoisie of industrial Britain—or the fictional factory owners like Thornton. But the reality is that the workers' jobs depended on Javier and Thornton keeping their doors open, which was not a simple task.

This is not a blanket defense of hacenderos. My story has some "sugar coating." It is romance, after all!

(Note: Hacendero is the older Spanish spelling, though you will often see haciendero in the Philippines and elsewhere. However, in my research, the version without the added i was more popular in contemporary sources.)

However, the true model for Javier (other than Enrique Iglesias, above) was less Darcy and more John Thornton of Elizabeth Gaskell's North and South. (See the 4-part BBC series. You won't be disappointed.) By the time Javier inherits Hacienda Altarejos, the boom times are gone. He has to deal with war (several of them), closed ports, labor shortages, rinderpest and cholera epidemics, drought, and American trade restrictions. Moreover, without a sugar central, his product is no longer the best available. Javier is a good man doing the best he can to keep a major economic enterprise going in tough times. Hacenderos had a reputation of getting rich off the work of their wage laborers, much like the bourgeoisie of industrial Britain—or the fictional factory owners like Thornton. But the reality is that the workers' jobs depended on Javier and Thornton keeping their doors open, which was not a simple task.

This is not a blanket defense of hacenderos. My story has some "sugar coating." It is romance, after all!

(Note: Hacendero is the older Spanish spelling, though you will often see haciendero in the Philippines and elsewhere. However, in my research, the version without the added i was more popular in contemporary sources.)

Published on January 03, 2016 07:28

•

Tags:

austen, darcy, enrique-iglesias, gaskell, glossary, hacendero, hacienda, north-and-south, pride-and-prejudice, richard-armitage, sugar-sun, thornton

Sugar Sun Series Extras

Illustrate the Sugar Sun Series with maps of the islands and Manila in 1902, as well as an annotated glossary of terms unfamiliar to some American readers. If you would like to view my blog (from when

Illustrate the Sugar Sun Series with maps of the islands and Manila in 1902, as well as an annotated glossary of terms unfamiliar to some American readers. If you would like to view my blog (from whence these came) go to jenniferhallock.com. Thank you!

...more

- Jennifer Hallock's profile

- 38 followers