Jennifer Hallock's Blog: Sugar Sun Series Extras, page 21

July 28, 2016

July 21, 2016

The Gilded Age: A Romantic History

What is the chief end of man?—to get rich. In what way?—dishonestly if we can; honestly if we must. Who is God, the one only and true? Money is God. God and Greenbacks and Stock—father, son, and the ghost of same—three persons in one; these are the true and only God, mighty and supreme…

—Mark Twain, in “The Revised Catechism,” printed in the New York Tribune on September 27, 1871

Twain didn’t hold back, especially not when criticizing society’s ills. In fact, he is the one who coined the term the “Gilded Age” to describe a time of conspicuous consumption, wealth disparity, and pervasive corruption. Sound familiar? In fact, esteemed economists (here and here) claim that we are smack dab in the middle of a new Gilded Age: the era of the one percenters.

The robber barons of Twain’s time were innovators, though, not fund managers. They were builders, not firm-breakers. They were self-made men who harnessed the raw power of the industrial age: Carnegie casted the steel, Rockefeller drilled the oil, and Vanderbilt laid the railroad track. Though not of noble birth—far from it—they were still the new kings, and they lived like them.

I recently traveled to Newport, Rhode Island, where the Gilded Age rich of New York spent hundreds of millions of today’s dollars building “cottages” that they lived in for only 8-12 weeks in the summer. Let me say that again: the equivalent of $30-200 million on a house used two months out of the year! Yeah, that’s almost criminal.

Creative commons photo of the Vanderbilts’ seaside getaway, The Breakers, by Wally Gobetz.

Creative commons photo of the Vanderbilts’ seaside getaway, The Breakers, by Wally Gobetz.These days, the houses of Newport’s Cliff Walk and Bellevue Avenue are open to the public. Crowds mill through The Breakers, but I actually prefer The Elms, which was built by coal tycoon Edward Julius Berwind. It seems more livable—or just more endearingly excessive.

Clockwise from left: The Elms front facade, Mr. Berwind’s office, and the dining room.

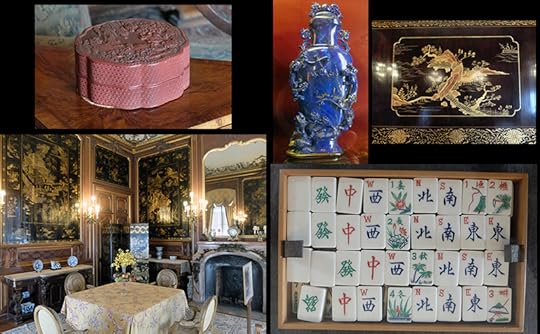

Clockwise from left: The Elms front facade, Mr. Berwind’s office, and the dining room.Interestingly, the Berwinds were particularly fascinated with Asian art. While the Vanderbilts built Italian palazzos and French châteaux, the Berwinds were the ones who added mahjong and black lacquer wall panels to the mix.

Some of the Asian treasures found at The Elms: lacquer panels, carved boxes, a jade collection, and mahjong tiles. Mr. Berwind’s sister did actually play mahjong—or at least the tiles seemed used and she had a well-loved instruction book. She was also one of the few to live in Newport year round, so she needed something to do when the socialites went home. But with whom did she play?

Some of the Asian treasures found at The Elms: lacquer panels, carved boxes, a jade collection, and mahjong tiles. Mr. Berwind’s sister did actually play mahjong—or at least the tiles seemed used and she had a well-loved instruction book. She was also one of the few to live in Newport year round, so she needed something to do when the socialites went home. But with whom did she play?An Asian touch was fitting since the Americans were not the only ones who lived large at the turn of the twentieth century. Prominent Filipino ilustrados had risen to the top by virtue of their education, their enterprise, and their mestizo connections, and they had their own gilded treasures, as the León Gallery’s recent exhibition in Manila shows.

The gallery was able to repatriate previously unknown artwork produced by Filipinos, often for European patrons, including pieces produced by Juan Luna and Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo for the General Exposition of the Philippines Islands, Madrid, 1887. The gallery owners wanted to show us that the Philippine Gilded Age was just as progressive and cosmopolitan as that of their arriving American conquerors. Javier Altarejos would agree.

Photos of the Filipino Gilded Age exhibition by Inquirer and Spot.ph.

Photos of the Filipino Gilded Age exhibition by Inquirer and Spot.ph.Since I am stuck in New England, I had to send my always-curious friend Suzette de Borja to investigate. (Thank you, Suzette!) The furniture was beautiful. Suzette’s daughter especially loved the Manila aparador made from kamagong wood (above left), with a price tag of only P25 million, or about US$500,000.

Photographs by the intrepid Suzette de Borja.

Photographs by the intrepid Suzette de Borja.Suzette and I have more modest tastes. I liked the bahay kubo painted on a local oyster shell, and she liked the drawing of the man with his fighting cock because it reminded her of this line of Under the Sugar Sun: “A local wag once said that in case of fire a Filipino would rescue his rooster before his wife and children—and hadn’t Georgie witnessed that with her own eyes in Manila?” You can also see a casco in the background, which is the type of boat that Della Berget comes ashore in at the beginning of Hotel Oriente. It is strange that Filipino artists wanted to immortalize such average scenes of local life because we all can agree that it is—and was—good to be rich.

But I know what you’re saying: weren’t these robber barons or hacenderos bad people? Why are we so fascinated with them?

Well, this is romance, so we romanticize them, of course. I romanticized Hacienda Altarejos, and I knew it while I was doing it. The true history of sugar in the Philippines is a story of great injustice. If you did not know that, there is a new documentary out there to guide you through that reality called Pureza: The Story of Negros Sugar. The Gilded Age was fraught with labor disputes on the other side of the Pacific, as well—the Pullman Strike, the Haymarket Riots, the Coal Strike of 1902, just to name a few. This was the other reason Twain used the term Gilded Age, because all that glitters is not gold.

But historical romance has always been fascinated with the obscenely rich because wouldn’t we love to live that lifestyle? I mean we were raised on fairy tales of Cinderellas and Prince Charmings—and we hardly spared a thought about the peasants of the kingdom. I teach my students about the horrible injustices of the early industrial age, but you better believe that John Thornton of Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South gets my engine going! (And, yes, it helps that he is played by Richard Armitage in the BBC version. Don’t worry, it’s on Netflix.) Gaskell wrote her novel in 1855—smack dab in the worst excesses of this period—and she still made a factory owner swoon-worthy.

BBC classics in my stable:

North and South

and

Pride and Prejudice

.

BBC classics in my stable:

North and South

and

Pride and Prejudice

.What about our Regency bookshelf? We don’t ask where Fitzwilliam Darcy got his ten thousand (pounds) a year—which, in present value, could be close to $6 million, or, in prestige value, maybe as much as $18 million. Yes, he earned interest on government bonds, but where did he get his principal wealth? From the sweat on the brows of farmers on “his” estate, of course. And, according to Joanna Trollope, Pemberly was built on the proceeds of coal mines. As a granddaughter of a coal miner, I can tell you that line of work not only sucks, but it will also kill you.

And it gets worse: men like Darcy were probably invested in another lucrative crop, one grown across the Atlantic in the West Indies. You guessed it. Sugar again! This was the “dark underbelly” of the British peerage, according to Trollope. And the sugar industry in the Caribbean and South America was the worst in the world: the average life of a slave there was five years. Hacienda Altarejos is practically a hippie commune, in comparison.

So, if we squint hard, we won’t see the nasty side of our historical romances, leaving us free to imagine the great parties, the family sagas, and the romantic intrigue. This is, after all, entertainment.

A great thing about Gilded Age tycoons—whether American or Filipino—in comparison to our Regency heroes is that at least they had to do something to earn their money. This was the era of manliness, after all. You were supposed to roll up your shirtsleeves and get your hands dirty:

Javier placed the shovel in line with the stones, put his foot on the top of the blade, and pushed it deep. It slid into the soil. Georgie watched Javier reach down and grip the handle low, a position that gave him more control. He lifted the earth and placed it carefully to the side. When he raised his foot again to the top of the blade, the tight line of his trousers revealed a strong thigh and backside. Color rose to her cheeks. She felt a whole different kind of dirty watching him.

If you want more Gilded Age romance, Joanna Shupe’s Knickerbocker Club series has a very delicious hero, Emmett Cavanaugh, whose rags-to-riches story was the embodiment of everyone’s hopes and dreams in the period.

Emmett is rough, yet gentle. Arrogant, but thoughtful. He’s that classic Type A hero we love so much, but instead of spending his excess energy whoring or hunting as a peer would do, he’s actually got shit to do. (He does box, though. Yum.)

Another recent release with a Gilded Age merchant-on-the-rise is Marrying Winterborne by Lisa Kleypas. Rhys Winterborne is a Welsh department store owner, a terrific choice of occupation since these diverse enterprises, selling all types of ready-made goods to the blossoming middle class, were an industrial age phenomenon—a true “retail revolution.”

Do not forget that all of these men would have been snubbed by the vaunted ton of London. John Thornton, Emmett Cavanaugh, Rhys Winterborne, and Javier Altarejos—none would have received an invitation to Almack’s. But, as Kleypas herself said: “There’s something invigorating about a hero who has created his own success.”

The Gilded Age can offer you something no other historical romances can: a self-made Prince Charming—what else could you want? Just relax and enjoy the fairy tale.

July 15, 2016

Sugar Sun series reading order

I am often asked which book in the Sugar Sun series is meant to be first, and my answer so far has been either one—an ambiguity not appreciated amongst fans of series romance. And I don’t blame you. It’s a crap answer. I like to read in order, too.

The main books of the Sugar Sun series—Under the Sugar Sun (published 2015), Sugar Moon (coming in late 2016), and Sugar Communion (look for it in early 2017)—should be read in order. Do not pass go. Do not collect 9430 pesos (US$200 as of this posting).

But the novellas have more flexibility. While they fit into specific moments on the timeline, there are no spoilers, nor do they propel major plot points. They are pure fun—my chance to redeem some side characters, like Rosa Ramos, or explore some minor heroes in more depth, like Moss North. You will be able to read these novellas at any time without worry of ruining the overall hacendero experience.

However, if you want more guidance, I made the graphic below to help new readers.

And for those of you who want even more details, here’s the chronology: Hotel Oriente is set in 1901; Under the Sugar Sun picks up next in 1902-1903; an upcoming novella on Rosa follows in 1904; and then Sugar Moon very deliberately continues through 1905-1906, when the proverbial shit is hitting the fan again in Samar. Sugar Communion spans the longest period yet, going back through Andrés’s childhood (yay!), with the main part of the action happening between 1906-1913. (As I’ve said before, it’s complicated. The man’s a priest, after all. He does “not go gentle into that good night,” to borrow from Dylan Thomas.)

If you are unfamiliar with Philippine-American history in general, start with Hotel Oriente. Its American hero and heroine are meant to quite literally orient my Stateside readers to Manila. It will warm you up—see what I did there?—for the more immersive historical experience in Under the Sugar Sun. By then, you’ll be like, “Bring on the historical smooching, bitches!” (And, yes, they do more than smooching. Yay!)

July 8, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #22: bahay na bato

Last week I discussed the clever, airy design of a native cube house on stilts, the bahay kubo. The Spanish saw these kubos and thought: how we could steal their environmentally-intelligent design, yet make it a whole lot more posh and expensive? The original bahay na bato (stone house) was born.

Three views of the Balay Negrense, or the Victor Fernandez Gaston Ancestral House, in Silay City, outside Bacolod, in Negros Occidental. This is a Philippine Cultural Heritage Monument. Beautiful creative commons photos by Kenji Punzalan.

Three views of the Balay Negrense, or the Victor Fernandez Gaston Ancestral House, in Silay City, outside Bacolod, in Negros Occidental. This is a Philippine Cultural Heritage Monument. Beautiful creative commons photos by Kenji Punzalan.Though the stilts of the bahay na bato are hidden by a stone wall “curtain,” the concept is really the same. This bottom story, or zaguan—vaguely resembling a dungeon—is a combination garage, warehouse, office, and stables. From my character Javier Altarejos’s perspective, it is a highly practical design: “The stone base of the house served as a storeroom for everything that made the hacienda hum: carriages, rice, tools, chickens, and—of course—sugar.”

In fact, Casa Altarejos was modeled on the Museo De La Salle at De La Salle University-Dasmariñas, an ilustrado lifestyle museum built upon the models of the Constantino house in Balagtas, Bulacan; the Arnedo-Gonzales house in Sulipan, Apalit, Pampanga; and the Santos-Joven-Panlilio house in Bacolor, Pampanga. One thing a visitor will immediately notice at Museo de la Salle is that the building is a perfect square—a bahay kubo writ large. Georgina’s impression of Casa Altarejos mirrored mine at the Museo de la Salle: “A wooden top floor overhung the gray stone foundation by a few feet on all sides, an elegant-yet-clumsy layer cake decorated in white and green frosting.”

The Museo De La Salle (clockwise from top left): exterior of bahay na bato, puerta mayor with postigo, portico around edge of house, and zaguan staircase.

The Museo De La Salle (clockwise from top left): exterior of bahay na bato, puerta mayor with postigo, portico around edge of house, and zaguan staircase.Javier again focuses on the logic of the construction: “The architecture was a…patchwork of foreign and native elements: stone foundations topped by light wood structures, an elegant yet practical design in earthquake country. Huge sliding panels opened up to the breeze, their rectangular frames checkered with iridescent capiz shells that let in light but wouldn’t shatter at every tremor. It was a mongrel style, and it suited Javier.”

A hacienda guest would enter through the zaguan, walk past the overseer’s desk and waiting workers, and ascend up to the second story: “The ‘princess’ steps had been fashioned deliberately shallow to allow for the modest ascent of a young lady in her skirts. Javier had stumbled down them many times, both as a child and an adult, and he never failed to swear up a storm as he did. Sometimes he wanted to take an axe to them, and he might have done that long ago if they were not such a rich Narra wood.” That’s such a guy thing to think, I suppose. Men didn’t have to wear full skirts with tiny slippers, nor did they have to worry about the grace of their entrance.

The sala of the Crisologo House and Museum in Vigan, Luzon. Photo by Jennifer Hallock.

The sala of the Crisologo House and Museum in Vigan, Luzon. Photo by Jennifer Hallock.Like a bahay kubo, the real house is upstairs: the caida (foyer), sala mayor (sitting room), comedor (dining room), the cuartos (bedrooms), the cocina or kusina (kitchen), despacho (office), comun or banyo (toilet), often an azotea (open balcony), and maybe an oratorio (prayer room). None of these “rooms” are really separate, though. Georgina notices right away that “carved moldings—the design as fine as lace—divided the large space into separate salons.” In other words, none of the walls were complete. Air circulated freely through the entire story, and so did noise. As one author points out:

So much for privacy. However, in houses like these, residents found enough privacy to conceive, deliver and nurse babies, to care for the sick and the aged….When in need of solitude, a thin cloth curtain strung over an opening stakes out a private section. Temporary as the privacy may turn out to be, the fluttering illusion of an unlatchable door screens the rest of the family out. Blissful seclusion means not being able to see the others, but still remaining within full hearing range.

According to a friend of mine who is descended from Bacolod sugar royalty, everyone could hear a couple having sex, so this meant that enterprising couples stole any moment they could: dressed or not, standing or lying down, in a secluded corner or in the open portico walk that lined the house. The growing pack of children of Hacienda Altarejos will be proof that Javier and Georgina manage to find a little privacy wherever they can.

See more images of Philippine ancestral homes at my Pinterest site.

July 1, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #21: bahay kubo

As Fernando Zialcita and Martin Tinio Jr. wrote in their beautiful book, Philippine Ancestral Houses: “Southeast Asians share many things in common: patis [fish sauce], bagoong [fermented fish paste], certain linguistic patterns, and a high regard for women’s rights. But the most visible symbol is surely the ubiquitous house on stilts.”

An 1898 photo of three American soldiers in front of a bahay kubo. This house is particularly low, so it does not include the thatched siding used for the bottom silong area, as seen in later photos.

An 1898 photo of three American soldiers in front of a bahay kubo. This house is particularly low, so it does not include the thatched siding used for the bottom silong area, as seen in later photos.In the Philippines, if you are looking for traditional architecture untouched by Spanish and American influences, look no further than the bahay kubo, or “cube house.” And though there are many regional variations, in the lowland areas a cube is a perfect description:

These houses are usually about fifteen feet square, with one large room, and are raised about six feet from the ground. Under the house is kept the live stock. When the family has a horse or cow or carabao the house is ten feet from the ground, and these animals are stabled underneath. In nearly every house or yard may be found a game cock tied by the leg to prevent him from roaming and fighting.

Street of nipa huts in 1900 Manila, in a photograph from the University of Michigan archive.

Street of nipa huts in 1900 Manila, in a photograph from the University of Michigan archive.Americans often called these residences nipa huts, even though not all have roofs of thatched nipa palm. Anahaw palm leaves or cogon grass are similarly popular. The frames are made of coco lumber, hardwood (if you were rich), and split bamboo. Again, here is Zialcita and Tinio:

A unique feature of the bahay kubo is that its floor is, by turns, a horizontal window, a permanent bed or a basket, for it is made of thin bamboo slats, each around two and a half centimeters wide and spaced from each other at regular intervals. Even when the wall windows are closed, light and air pass through the floor to ripen piles of vegetables or to soothe anybody sleeping on the well-polished slats. At the same time, waste matter can be thrown out through the gaps….For bodily needs, there are always the bushes; at night, however, especially when it is storming, the slatted floor becomes a convenient enough substitute.

Call me spoiled, but when my husband had our own bahay kubo built on our farm, I had him install a toilet. It was still bucket flush, but you’ve got to admit it was nice. His own choice of improvement was a wind turbine to power our computers, stereo and speakers, and wifi access. It was definitely a twenty-first century kubo.

The twenty-first century extras of our bahay kubo in Cavite: wind generation and indoor plumbing. both projects designed and completed by Mr. H, some some help. I was impressed.

The twenty-first century extras of our bahay kubo in Cavite: wind generation and indoor plumbing. both projects designed and completed by Mr. H, some some help. I was impressed.Early American writers were fascinated with the one-room living accommodations of most Filipino families—how quickly they had forgotten that working-class houses in the United States and Europe were frequently one room per floor, and American frontier homes were single rooms, as well. In these northern hemisphere cases, the choice was essential because it was the easiest way to heat a home around a single stove. Where I live in New England, every town has proudly preserved its original one-room schoolhouse. But this is not all past glory. The single-room style has come back to modern architecture, just with a new name: open plan.

Of course, the bahay kubo does take open plan a step further than we would like—a step right into the bedroom. As Zialcita and Tinio wrote: “Nor does each member insist on a well-demarcated sleeping territory, a mat unto himself. Children sleep with their parents and grandparents on the same mat till they are ready to marry.” Again, though, this was the norm in American households through the early twentieth century. Either that, or you let the children sleep in the attic, which is exactly what Louisa May Alcott did at her house in Harvard, Massachusetts, at the Fruitlands Museum. I’ve seen her bunk, and I think I’d prefer a mat in the open-plan kubo.

Children of guests at our bahay kubo in Cavite, with sunflower in the foreground.

Children of guests at our bahay kubo in Cavite, with sunflower in the foreground.The bahay kubo was actually ahead of its time in many ways. It was not only well suited to its environment, but friendly to the environment, as well. Architect Angelo Mañosa has said:

In its form, it already embodies all the design principles we think of as ‘green.’ It is made of low-cost, readily available indigenous materials and it is designed for our tropical climate: the tall, steeply-pitched roof sheds monsoon rain while creating ample overhead space for dissipating heat, the long eave lines provide shade. The silong underneath the house creates a simple, utilitarian space while allowing ventilation from below through the bamboo slat floors. The large awning windows, held open by a simple tukod (sturdy rod), provide cross ventilation and natural light. All of the materials used in it are organic, renewable, and readily available at little cost. And yet it is strong enough to withstand typhoons. The bahay kubo even survived the ash fall from Mt. Pinatubo, when more ’modern’ houses collapsed.

This is all true. However, Zialcita and Tinio are a little more ambivalent about the kubo’s resistance to the elements. As they point out, it does sway with the shock of an earthquake. “Indeed, even without earthquakes, the bahay kubo sways to and fro when someone within runs or moves about brusquely. Repeated shocks, however, can collapse the bahay kubo.” Moreover, it is no match for a strong typhoon. And then there’s fire.

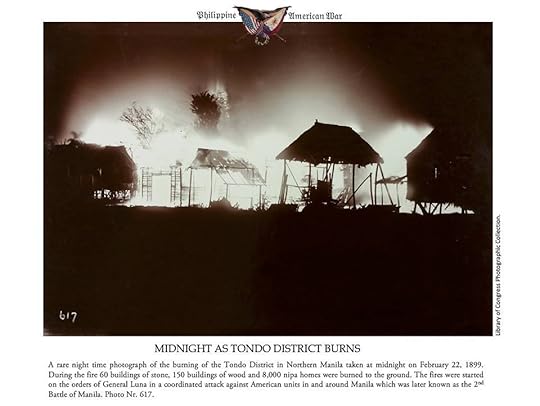

An excellent photograph from the Philippine-American War Facebook group, moderated by Scott Slaten and David Metherell.

An excellent photograph from the Philippine-American War Facebook group, moderated by Scott Slaten and David Metherell.While the above Tondo fire was believed to be set by insurgents, the Americans torched their fair share of homes. In fact, it was sometimes policy:

A piece of fiery thatch floated through the air near [Georgie’s] head. A fresh gust of wind blew it up and over the street toward a cluster of neighboring homes whose occupants were still in the process of pulling out their belongings. The fireball rose and fell, dancing through the dark sky in slow motion, until it landed on the grass roof of one of the huts, igniting in seconds.

Everyone, including the firemen, rushed to warn those inside, but somehow Georgie got there first. She climbed the ladder into the hut and found a small boy holding a baby. He looked at Georgie with wide eyes as if she, not the fire, was the monster devouring his home.

—Under the Sugar Sun

In the opening scene of my novel, the cholera police have set fire to a whole neighborhood to rid the area of disease—which, in fact, was one of the methods that American officials used in the terrible epidemic of 1902. (They believed they were being scientific, but they probably scattered the carriers of the disease farther than the old Spanish system of in-home quarantine.) I think that part of the American willingness to torch the homes was a suspicion of the kubo, which wore off on the locals, too.

It is true that kubos are not that durable. According to Zialcita and Tinio again, the bamboo rafters only last through about five rainy seasons, the rest of the bamboo becomes brittle in a decade, and (from my own experience) cogon roofs need to be patched and replaced far more often than corrugated iron. Some provinces like Surigao Del Norte still brag that over 50% of their houses’ roofs are made from natural materials, but city residences have embraced utilitarian concrete (and air conditioning). (Stone was a choice of the Spanish and mestizo elite, but most of the non-volcanic kind had to be imported, so it was not an option for most.)

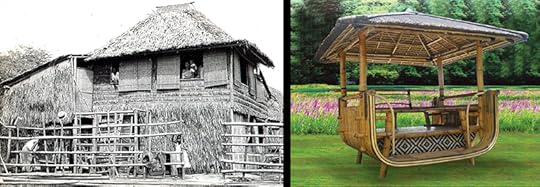

A street scene in 1899 suburban Manila.

A street scene in 1899 suburban Manila.You cannot blame people for choosing the most long-lasting and comfortable option available to them individually, but at what social cost? How much material culture has been lost? In 2014 a town in Pangasinan revived its bahay kubo heritage with a fiesta display on the town square. Each of 21 barangays competed to build the best kubo to showcase its construction skills and to promote the local bamboo industry. But how long before a village cannot find someone to build a real, quality kubo—not just one of the roadside-style gazebos? Of course, this is an easy question for an academic like me to ask, but I did not live in my own kubo full time. Fortunately, Angelo Mañosa has come up with 18 ways to use the design elements of a bahay kubo as a template for a green modern house, a fitting way to preserve history and embrace the future at the same time.

A comparison of a large nipa house and an elegant nipa gazebo.

A comparison of a large nipa house and an elegant nipa gazebo.

June 23, 2016

Sugar Sun series location #6: Luneta

Wealthy doñas, notoriously late risers, would bathe and dress just in time to catch the evening breeze that cooled the bay and blew away the mosquitos. Once there, they would catch up on the latest tsismis, gossip passed from calesa to calesa like a tattler’s telegraph. Then they would be off to eat and dance at a friend’s house, returning home shortly before dawn to sleep through another morning. Meanwhile, their servants ran their households, farms, and shops.

Javier’s carriage got in line with the others circling in comfort, leaving the poor to walk the shoreline. Calling the Luneta a park was a bit generous, considering the utter lack of trees or foliage. The only decorations were incandescent gas lanterns circling the perimeter, sort of like candles on a vast birthday cake.

— Under the Sugar Sun

The Luneta at sunset.

The Luneta at sunset.Called the “Champs-Elysées of the Philippines” by a French physician in the early nineteenth century, Luneta Park was also dubbed “the favorite drive of the wealthy [and] the favorite walk of the poor people.”

There were three good reasons for this. First, as one American wrote: “The sunsets from the Luneta have been more than pyrotechnic, and I now believe that nowhere do you see such displays of color as in the Orient, Land of the Sunrise.” Troubling Orientalist fetish aside, I think he’s right. And the sunsets may have actually gotten better with pollution, as long as you like the color red. Hey, don’t blame me—Scientific American actually agrees.

Creative commons image of a Manila sunset by Randy Galang.

Creative commons image of a Manila sunset by Randy Galang.The second and third reasons for the popularity of the Luneta come from Edith Moses, wife of one of the first Philippine commissioners: “There is always a breeze and there are no mosquitoes; besides that, one meets everyone he knows, and ladies visit in each other’s carriages in an informal way….There is the comfort of dispensing with hat and gloves, and many ladies and almost all young girls drive in low-necked dinner or evening dresses.” It boils down to (2) no mosquitos and (3) a serious party.

If the Luneta was the place to be, naturally it was where Javier took Georgina on their first “date,” though she did not realize that’s what it was. He’s a sly dog, that Javier. He’s also part Spanish, and the Spanish were the first to ritualize visits at the Luneta, including the rules of the road, prompting Georgina to ask:

“What would happen if we turned the carriage around and circled in the other direction?”

Javier laughed. “You are a rebel, Maestra.”

“No, really,” she urged on. “This whole orderly migration—I just can’t reconcile it with the chaos of the rest of the city.”

“That’s why the Spanish liked it,” he answered. “Only the archbishop and governor-generals’ carriages were allowed to pass against the line. That way you had no excuse but to recognize and salute them as they passed.”

“You could get in trouble for forgetting?”

“Absolutely. The Peninsulares believed it important to punish people for small sins lest they attempt any larger ones. It’s not an uncommon assumption among occupiers.”

— Under the Sugar Sun

Ouch. Javier was not a huge fan of the newly-arrived Americans, as most readers know, which is why of course he was destined to fall in love with one. But he had a point: the Yankees ultimately ruined a good thing.

The featured 1899 photo of the Luneta. These girls look like they’re having fun! (Umm, that was sarcasm. Look at the companion on the left with her arms folded across her chest.)

The featured 1899 photo of the Luneta. These girls look like they’re having fun! (Umm, that was sarcasm. Look at the companion on the left with her arms folded across her chest.)Maybe it was because the Luneta was not grand enough for them. The wife of Governor William Howard Taft was underwhelmed at first:

“And now we come to the far-famed Luneta,’ said Mr. Taft, quite proudly.

“Where?” I asked. I had heard much of the Luneta and expected it to be a beautiful spot.

“Why, here. You’re on it now,” he replied. An oval drive, with a bandstand inside at either end—not unlike a half-mile race track—in an open space on the bay shore; glaringly open. Not a tree; not a sprig of anything except a few patches of unhappy looking grass. There were a few dusty benches around the bandstands, nothing else—and all burning in the white glare of the noonday sun.

While Helen Taft did eventually warm to this “unique and very delightful institution,” it was not love at first sight. She was not the only one, either. One American wrote a letter back to her friend in Scranton, Pennsylvania, which the friend sought fit to publish in the local Republican newspaper: “The Luneta is crowded every afternoon with officers dressed in spotless white from their heads to their heels driving fast horses and flirting with other men’s wives. The husbands, as a rule, are at the front and only get in occasionally, tired out and dirty, and it makes me sick.”

There had always been a social side to what went on at the park—innocent courtship right under the friars’ and nuns’ noses—which is why the place was an early favorite of my character Allegra. But it took American naval officers to add infidelity to the list of pastimes. Officers courting a querida was common enough that it was captured in this awesome 1899 Harper’s Weekly centerfold, of which an original hangs in my dining room (because eBay makes such delights possible).

G. W. Peter’s illustration, “An Evening Concert on the Luneta,” which was published in Harper’s Weekly as the centerfold on 25 November 1899. I color-corrected a high resolution image I found to bring out the American soldiers on the right side.

G. W. Peter’s illustration, “An Evening Concert on the Luneta,” which was published in Harper’s Weekly as the centerfold on 25 November 1899. I color-corrected a high resolution image I found to bring out the American soldiers on the right side.There seems to have always been music at the Luneta—small bands were ubiquitous in the islands, and every village had at least one—but the Americans congratulated themselves for adding the Philippine Constabulary Band to the regular roster. These musicians, led by African-American conductor Lt. Walter H. Loving, were widely noted for their excellence. They not only traveled to St. Louis for the 1904 World’s Fair, but they were also invited to play at President Taft’s 1909 inauguration.

Part of the March 8, 1909, feature on the band’s concert for Taft’s inauguration. In an earlier Boston Globe article, it quoted Maj. Gen. Franklin J. Bell, of American reconcentrado fame, as calling for an end to “freak features” of the parade. Even the above article, which was very favorable to the band, claims that the men had “never seen an instrument” before the American arrival, which is so preposterous a claim that only other Americans would believe it.

Part of the March 8, 1909, feature on the band’s concert for Taft’s inauguration. In an earlier Boston Globe article, it quoted Maj. Gen. Franklin J. Bell, of American reconcentrado fame, as calling for an end to “freak features” of the parade. Even the above article, which was very favorable to the band, claims that the men had “never seen an instrument” before the American arrival, which is so preposterous a claim that only other Americans would believe it. A photo of the band in the March 1909 blizzard inauguration of President William Howard Taft.

A photo of the band in the March 1909 blizzard inauguration of President William Howard Taft.One of the Constabulary Band’s favorite numbers was one Americans would still recognize, as it is played by modern university marching bands at football games:

“Hey, that’s ‘Hot Time in the Old Town,’” Georgina exclaimed. “How’d they learn American music?”

“The ‘Hototay’ we call it,” Allegra said. She sat between Javier and Georgina, but she was too tiny to be much of a barrier. “The song is everywhere, even funerals. Filipinos think it is your national anthem.”

Georgina laughed. “Maybe it should become yours.”

“You suggest we adopt the drinking song of an occupying army?” Even before Javier finished the question, he regretted asking it. Hay sus, why couldn’t he keep his mouth shut?

—Under the Sugar Sun

Maybe Javier was a bit sensitive, but Georgina certainly did arrive in the Philippines with the “benevolent assimilation” bias of the other Insulares and Thomasites, though she will take her mission to an interesting and sexy extreme. Though it is important to point out that even at the beginning, she was not hateful. Many were. Take the author of those 1900 letters published in the Scranton Republican, who said: “As soon as the concert is over, ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ is played…Every soldier and sailor and all the Filipinos (deceitful wretches) stand with uncovered heads until the last strains die away…” (italics mine).

Maybe you can forgive the woman her racism because Manila was still a field of battle in the Philippine-American War, but maybe not. The Americans were, after all, the intruders. My husband gave me a huge coffee table book from 1899 entitled Our Islands and Their People—a threatening premise, as if “their people” are infesting “our islands,” and how dare they! The text of the book is pretty neutral, and the photographs themselves beautiful, but the captions are outrageous. You can read more on the racism of the day here.

The Americans believed that they were improving the islands, but they did not improve the Luneta. In fact, they may have ruined it. If you have been the Luneta, you are probably confused by everything written above because the main body of the park is most definitely not along the shoreline—not anymore. In the construction of the port of Manila in 1909, the Americans reclaimed 60 hectares of land, the first of many expansions.

The map of Manila’s shoreline before and after the 1909 port and land reclamation project.

The map of Manila’s shoreline before and after the 1909 port and land reclamation project.By 1913, a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle wrote: “Today the Luneta remains as it was in the old Spanish days, but its chief charm, the seaward view, is gone. This is due to the filling in of the harbor front, which has left the Luneta a quarter of a mile from the waterfront.” On their new land, the Americans built a “Gringo Luneta,” in the words of Nick Joaquin, and it was here that they eventually put their own exclusive social clubs, like the Elks Club, the Army and Navy Club, and the Manila Hotel—all gated or indoor establishments. They managed to keep the seaside space for themselves and relegate the poor to their own homes. Shame.

A postcard from the Commonwealth period, 1934-1946.

A postcard from the Commonwealth period, 1934-1946.One thing that hasn’t changed in Manila since 1900 is the traffic. The anonymous visitor who called the Filipinos “deceitful wretches” also said about the end of the evening: “there is a crack of the whip and a grand hurrah and one mad dash for the different homes. I wonder there are not dozen smash ups each afternoon, but there are not. I used to melt and close my eyes, expecting to be dashed into eternity any moment, but I have learned to like it, and I don’t want any one to pass me on the road.” We’ve all been there.

A vintage postcard of the Malecón.

A vintage postcard of the Malecón.Some park goers did not wait for the end of the evening to race, though. With the old shoreline, the water went right up to the walls of Fort Santiago—or almost. There was a single open road there, called the Malecón, where carriages practically flew:

The two vehicles ate up the open road. Georgie did not consider herself a coward, but she was torn between fearing for the horses’ safety and for her own. Maybe sensing that, Javier put his arm around her shoulders, pulling her closer to his side. It was too cozy by half, but it steadied her enough to make the frenetic motion bearable.

The two nags kept changing the lead. One would break out in a small burst of speed, and then slow in recovery while the other made his move. They had at least a mile to go until the “finish” at Fort Santiago, and it seemed that Georgie’s original prediction was on the mark: the sole surviving animal would win. It was less a race than a gladiatorial bout. Unfortunately, their own horse showed signs of exhaustion first, probably because he pulled an extra passenger. His movements became choppy. His head drifted to the side, and he kept jerking it forward, again and again, as if the motion could create the winning momentum.

With every spasm of the horse’s head, the carriage jolted. Soon, the frame on Georgie’s side started shaking. The roof above them was supported by three thin pieces of bamboo, and she watched one pull out of its fastener. The front corner of fabric flapped wildly in the wind, pulling hard at the other two rods. Even more worrisome was the squeak of the wooden wheel to her left. If that splintered, the whole apparatus would collapse, probably pulling the two men and the horse right on top of her. The sound of hooves, wind, and screaming jockeys drowned out Georgie’s increasingly frantic warnings.

Or so she thought.

Javier tapped the driver’s shoulder. Hard. When the man didn’t respond, he grabbed the fellow’s arm and shouted. The driver argued back, probably insisting his animal could still win. Javier glanced over at Georgie briefly and added something in Spanish about “the lady.” He signaled again, this time his face quite stern. Javier’s scowl was, no doubt, the most effective weapon he had.

Georgie was grateful. They were finally slowing down. “The carriage is falling apart,” she tried to explain when she could finally be heard over the din.

“I know,” Javier said in quick English, peering over her lap to the wheel beneath. “We’ll make it, don’t worry. But I blamed quitting on you, so act like you might swoon.”

Georgie fanned herself wildly with her hand and threw back her head. Was that right? She had never before tried to feign fragility—it was not a safe thing to do in South Boston.

Javier watched her for a second, an unreadable expression on his face. Then he laughed—at her this time, not with her. “Wow, you do that badly.”

She gave him a little swat on the arm. “What a terrible thing to say.”

One eyebrow rose. “I don’t think so. I dislike weak women.”

“Then why put on a charade for the driver?”

Javier glanced up at the disappointed Filipino. “So he and his horse wouldn’t lose face. Honor matters even for a Manila cabbie, so I thought a little play-acting from you would be an easy solution. Now I’m not so sure.”

Georgie did not like her competency questioned, even in such a ridiculous arena. “I had no idea that theater was required. How convincing does this have to be?”

He looked at her intently. “Very.”

She slumped back in the seat, trying again to look helpless.

“Ridiculous,” Javier murmured under his breath as he reached out to her. Before she could react, he pulled her close, tucking her right shoulder under his arm and pressing her solidly against his chest. He gently brushed her cheek with his fingertips, the way one might soothe a skittish child. Up until that moment, Georgie had only pretended to faint; now she actually felt light-headed.

“Are you okay, mi cariño?” His words played to the driver, but they felt genuine enough to her.

She looked up. This close, she could see honey-colored circles in his brown irises. They looked like rings on a tree. Did she see in them the same fire she felt, or was this a part of the show?

Gently Javier tilted her chin up, his lips now inches away. No one had ever tried to kiss her, not even Archie–his amorous attentions had all been by pen. She thought about resisting, but that was all it was, a thought. Javier’s breath was clean. Only the smallest bite of scotch lingered from lunch. Given her past, Georgie had never believed alcohol could be an aphrodisiac, but on this man the crisp scent was provocative. He smelled of confidence and power, yet his lips looked surprisingly soft—

—Under the Sugar Sun

Ha ha, I think I’m going to leave it there. You’re welcome.

June 17, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #20: insular

Georgie looked over at the weapon Pedro still held in his hand, and she shivered. No matter how she felt about Rosa, she could not send her away with this man.

She had to figure out a way to scare Pedro off. “The Insulares will come. Soldatos!”

Filipinos had been put to death for far less than waving a knife in the face of an American. And what good was the Insular bogeyman if she didn’t let him out of the closet once in a while?

— Under the Sugar Sun

The Insular bogeyman? Is this some strange Grimm’s fairy tale you haven’t heard of?

Oh, no, it is something far more insidious: it’s a euphemism. And a legal one, no less.

Euphemisms were a whole new tongue spoken in nineteenth century America. In fact, I should not even say “tongue” because it could give you all sorts of salacious ideas. English naval captain Edward Marryat got in trouble for asking a female companion if she had hurt her leg when she had tripped, and he was informed that proper Americans did not use that word (leg). Limb was specific enough, thank you very much.

So, if you cannot say leg, you probably cannot say colony. No, the word colony does not have sexual undertones—at least, not that I know of—but it is still a troubling word for a formerly rebellious colony founded upon Enlightenment ideals of self-determination and personal liberty. What, the United States an empire?

Well, Thomas Jefferson said yes, actually, but he called it an “empire of liberty” that would expand westward and check the growth of the British menace, beginning with the 1803 purchase of Louisiana from the French. Jefferson wrote to James Madison: “I am persuaded no constitution was ever before so well calculated as ours for extensive empire and self government.” He saw no irony in defending, in the same breath, the right of self-government alongside the right to empire. In fact, he (like many today) believed that America’s democratic history, transparent legal system, and free market economy made it especially suited to transform the world for good and fight barbarism.

Out-of-copyright map of the American frontier.

Out-of-copyright map of the American frontier.In the resulting growth of (mostly white) settlements across the North American continent, the word “empire” was actually avoided. These were “territories” along America’s “frontier,” and to be fair these were territories on their way to statehood, a distinction that would not be granted to later acquisitions. According to Frederick Jackson Turner, the frontier helped preserve liberty and egalitarianism through free access to land (by taking it from the First Nations), preventing a landed aristocracy from developing. Out on the frontier, any (white) man could make something of himself, as long as he survived.

(If none of this sounds truly democratic, you’re right. You’re not the first modern reader to notice, trust me. As even Mark Twain wrote in 1901: “The Blessings of Civilization are all right, and a good commercial property; there could not be a better, in a dim light.” [Emphasis mine.] So don’t look too closely.)

Back to our discussion of “territories.” In the Treaty of Paris ending the Spanish-American War in December 1898, the United States purchased the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam from Spain. While the western frontier had expanded slowly enough to look like natural growth, this acquisition came in one fell swoop. What makes a piece of land a colony for Spain and not a colony when purchased from Spain by America? Good question.

Illustration (and featured image above) from an 1898 E. E. Strauss advertisement. Notice the spelling errors?!

Illustration (and featured image above) from an 1898 E. E. Strauss advertisement. Notice the spelling errors?!Clearly, we needed a new word. That word was insular. Geographer Scott Kirsch commented that the choice insular reflected “novel anxieties over America’s new place at the seat of an interconnected global empire.” It fit for three reasons:

First, these new possessions were islands, and the primary definition of insular is “of or pertaining to islands.” What a great way to differentiate the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam from the continental territories. Interestingly, though, Hawaii will not become an insular territory, despite being a cluster of islands. Instead, in the midst of the Spanish-American War, Hawaii had been enthusiastically annexed by Congress, an about-face since the country had rejected that opportunity only five years previously. A lot had happened in those five years, as you can read here. And if Hawaii didn’t count as insular, there had to be more to the word than just geography.

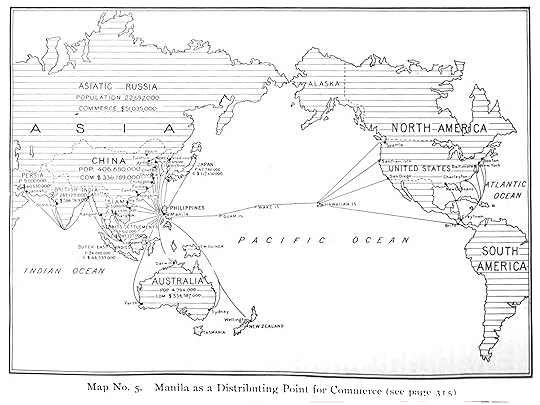

A second meaning of insular is “Detached or standing out by itself like an island; insulated.” This is where the word becomes perfect for how America wants to see its new acquisitions, particularly as relates to the Philippines. In the “scramble for the Pacific,” America had found itself left out of China. Secretary of State John Hay would address this particular issue in the Open Door memos, asserting the right of all nations to trade freely and equally in China. But the truth was that the US did not want to get too involved in China. It wanted the benefit of a Pacific entrepôt without being too sinified.

Manila had been the Spanish answer to cashing in on China while simultaneously insulating themselves from China, and the Americans thought it a brilliant idea. In a 1902 National Geographic article by the Honorable O. P. Austin, the Chief of the Bureau of Statistics of the Treasury Department, Manila would become the channel through which all of this wealth would pass, an off-shore customs and clearing house for goods bound for the United States. With the 1902 extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act—extended now to exclude Chinese from the Philippines, too—our new insular possessions would not be a conduit for people, just money. According to Scott Kirsch, this “coupled the virtues of proximity to Asia with a distinctive sense of separation from it.”

The insular plan of O. P. Austin.

The insular plan of O. P. Austin.Because, really, America wanted to be insulated from their own empire. This is the third reason the term insular fits so well. The definition of a colony is “a body of people who settle in a new locality, forming a community subject to or connected with their parent state.” This implies spreading both people and ideas to the new lands. Americans were willing to do the latter. In fact, President William McKinley asserted the idea of “benevolent assimilation”—that “we come not as invaders or conquerors, but as friends, to protect the natives in their homes, in their employments, and in their personal and religious rights.” Americans spread their language, their pedagogical ideals (see posts on Thomasites and pensionados), their sanitation principles, their political administration, and their products (Spam, anyone?) to the Philippines with gusto.

1899 Judge cartoon of Uncle Sam to Filipinos: “You’re next.”

1899 Judge cartoon of Uncle Sam to Filipinos: “You’re next.”But most Americans did not intend to settle in the Philippines permanently, which meant that it was not a colony in the true sense of the word. They meant to fashion Filipinos as Americans and leave, hence the emphasis on shaping the educational system with an eye toward self-replication. Even anti-imperialists like William Jennings Bryan, the failed 1900 Democratic candidate for president, felt this way. He wanted to close the door to Asian immigration, and during the debate about Chinese exclusion, he wrote:

“Let us educate the Chinese who desire to learn of American institutions; let us offer courtesy and protection to those who come here to travel and investigate, but it will not be of permanent benefit to either the Chinese or to us to invite them to become citizens or to permit them to labor here and carry the proceeds of their toil back to their own country.”

He felt the same about the Japanese and all other Asian races. His article is a defense of exclusion and intolerance: “It is not necessary nor even wise that the family environment should be broken up or that all who desire entrance should be admitted to the family circle. In a larger sense a nation is a family.” Bryan’s English and Irish ancestors had immigrated two hundred years earlier, so you can pardon him for forgetting that he was an immigrant, too. But he was typical in wanting to turn off the tap, and a colony would not have permitted that insularity as easily.

The San Francisco Call announces the extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act in April 1902.

The San Francisco Call announces the extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act in April 1902.This was not just about race, though. Americans wanted the Philippines to remain politically and economically separate. Eventually, one had to ask as the United States grew bigger: does the Constitution follow the flag? If the people of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam are living under American government, should they have the rights of American citizens? A longer treatment of this topic is handled here, but the short answer for the Philippines was no. The Insular Cases in the United States Supreme Court maintained that the Philippines was an unincorporated territory, and while its citizens had natural rights, such as religion and property, they did not have full political rights, nor citizenship. This was an easier line to skirt when the government ruling the Philippines was part of the Bureau of Insular Affairs in the War Department, not a Colonial Office. Labels do matter.

And strangely William Jennings Bryan, no friend of the Asian immigrant in general, actually pointed out the inconsistency of Americans flooding the Philippines while not allowing the same in return:

“If…the Filipinos are prohibited from coming here (if a republic can prohibit the inhabitants of one part from visiting another part of the republic), will it not excite a just protest on the part of the Filipinos? How can we excuse ourselves if we insist upon opening the Philippine islands to the invasion of American capital, American speculators, and American task-masters, and yet close our doors to those Filipinos who, driven from home, may seek an asylum here?”

Bryan’s solution was immediate independence for the Philippines, but the Supreme Court had a different solution: the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam were not a part of our republic. Insular was not inside. The justices bent over backwards to draw the distinction that Americans wanted, even if they essentially made up law to do it. Since both imperialists and anti-imperialists both agreed, in the words of Andrew Carnegie, that “Americans cannot be grown [in the Philippines],” no one complained that the court had exceeded its mandate. The insular designation stuck.

Escolta, the business district of Manila, on July 4, 1899.

Escolta, the business district of Manila, on July 4, 1899.Another benefit of insular territories was that free trade need not be extended right away—especially if there were concerns that the islands might compete too well in certain key industries, like sugar and tobacco. It was favorable for American producers to keep them out. While American goods could enter the Philippines freely—because Americans in the Insular Government set Philippine trade policy—Filipino goods were taxed both leaving the Philippines and entering the United States because the U.S. Congress set American trade policy. That was the beauty of the insular cases.

December 1898 Puck cartoon shows Uncle Sam welcoming world trade in his off-shore entrepôt.

December 1898 Puck cartoon shows Uncle Sam welcoming world trade in his off-shore entrepôt.When I teach my course on America in the Philippines, students who have at least read the course description know that the United States had its own empire—but surprisingly few adults do. They might know about Guam or Puerto Rico, and they might even call these “territories,” but if you ask them the difference between a colony and a territory, they do not have a good answer. And I do not blame them because America’s “insular” language has left its citizens deliberately insulated from clarity.

I do not think Filipinos are confused, though. They easily call the years between 1898 and 1934 the American Colonial Period, and many would also include the 1934 to 1946 Commonwealth Period (not counting the Japanese occupation of 1941-1945).

Unfortunately, if we Americans do not take a hard look at our history, we are doomed to repeat our mistakes and therefore reinforce the (mis)perceptions others have of us. One of my goals in writing the Sugar Sun series was to bring this history to a general public—along with some sex, drugs, and violence to really sell it. I love romance, so it was my medium of choice, but the Philippine setting, diverse characters, and political undertones are all part of my historical mission.

The Person Sitting in Darkness is almost sure to say: “There is something curious about this–curious and unaccountable. There must be two Americas: one that sets the captive free, and one that takes a once-captive’s new freedom away from him, and picks a quarrel with him with nothing to found it on; then kills him to get his land.”

— Mark Twain, “To the Person Sitting in Darkness,” 1901

June 10, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #19: pensionado

What did the Common App look like for Filipinos in 1905? Could you gain admission, let alone earn a scholarship?

While much of the American educational system in the Philippines was geared around a racist “industrial” model—in other words, teaching Filipinos the skills they needed to produce goods for American businesses—there was an advanced track to train the best and brightest for government work.

Here’s how it worked: young men and women aged 16-21 took an examination that included questions on grammar, geography, American history, math, and physiology. For example: “Give three differences between young rivers and old rivers.” Or “Name and describe three early and successful North American settlements.” Or “Divide 1003 3/4 by 847 4/5.” (Without a calculator, mind you. I could do it, but not happily. Multiply by the reciprocal, right? I’m already bored…)

Questions from the first scholarship exam of 1903, reprinted in a government circular as sample questions for teachers. Check out number 7 of the Arithmetic section. Yes, this was real.

Questions from the first scholarship exam of 1903, reprinted in a government circular as sample questions for teachers. Check out number 7 of the Arithmetic section. Yes, this was real.Where did such smart kids come from? Everywhere, actually. Even, or especially, the provinces. Despite its flaws, the American Bureau of Education did set up a public, secular, and coeducational system throughout the Philippines. Higher education had been open to elites under the Spanish, but for barangay children this was a brand new opportunity. The whole point of education, according to the 1903 census, was to pacify the islands—to give parents a good reason to set down arms and take a chance with Yankee rule.

And in order to truly “benevolently assimilate” these future elites, the Americans would need to shape their minds and careers in the American heartland: Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Iowa, New York, and Minnesota mainly, with a few in California, of course. The first group of 100 boys of “good moral character” and “sound physical condition” were selected: 75 from public schools throughout the islands and 25 at large by executive committee. In succeeding years, much smaller numbers would be chosen, a dozen or two at a time, including women. Each student was required to take an oath of allegiance to the United States before enrolling in the program.

Photos of Miguel Manresa, Jr., at Iowa State University, doing research on the effect of vitamins on the reproduction of intestinal protozoa in the rat. Photo 1 and Photo 2 from the Library of Congress.

Photos of Miguel Manresa, Jr., at Iowa State University, doing research on the effect of vitamins on the reproduction of intestinal protozoa in the rat. Photo 1 and Photo 2 from the Library of Congress.With $500 per year to cover expenses—two-thirds of an average American family’s income at the time—the Filipinos could live well in the smaller towns of the American Midwest. They went to football games, joined fraternities, and went out on dates. (More on that later.) Many did a year in an American high school first to polish their English, and then did three to four years of advanced study. Author Mario Orosa estimates that the Insular (colonial) Government spent the modern equivalent $50,000 or more educating his father in Cincinnati.

Students could study whatever subjects they wished, but they would have to put this knowledge to use: each year of study in the United States meant a year working (with a full salary) for the Insular Government in the fields of education, medicine, forestry, engineering, textiles, or finance.

In 1905, the highest scoring tester was a 12-year old girl named Felisberta Asturias. She may have been too young to go to the U.S., but the next highest scorer, Honoria Acosta from Dagupan, would become the first Filipina to graduate from an American university (Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania), and therefore the first Filipina physician, as well as the founder of obstetrics and gynecology as a specialized field in the Philippines.

Photos from pages 6-7 of the March 1906 issue of The Filipino, a pensionado journal.

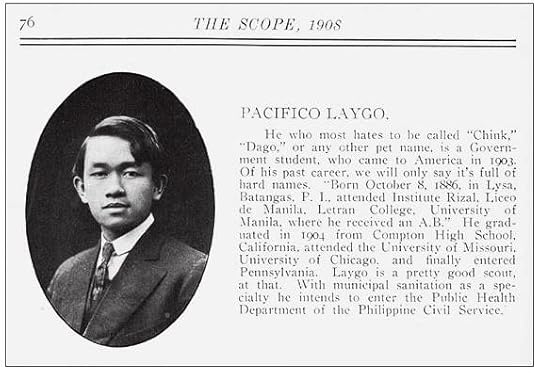

Photos from pages 6-7 of the March 1906 issue of The Filipino, a pensionado journal.Winning the scholarship was only half the battle, though. While in the United States, these students encountered their fair share of racism, as Pacifico Laygo’s yearbook entry illustrates.

Photo from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School yearbook, republished in Filipinos of Greater Philadelphia.

Photo from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School yearbook, republished in Filipinos of Greater Philadelphia.How tiring it is, this insistence of Lagyo’s that he not be called a racial slur! But he is a “pretty good scout, at that,” so it’s okay, right? That’s only patronizing, not explicitly racist. At Cornell, Apolinario Balthazar, one of those who would be responsible for rebuilding Manila after World War II, was told by one American bully that “no matter how much you wash your hands, you cannot change your color.” Southern states just outright refused to host the Filipino students.

Antonio Sison, future husband of Honoria Acosta, also at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. Photo from Filipinos of Greater Philadelphia.

Antonio Sison, future husband of Honoria Acosta, also at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. Photo from Filipinos of Greater Philadelphia.Newspapers got into the act, too. According to Victor Román Mendoza, the Omaha Daily Bee downplayed the athletic achievements of the local Filipinos students, saying: “That Filipino students are showing well as runners in college athletic events is not surprising to those who remember the good races won by the followers of Aguinaldo during the insurrection.”

Maybe it wasn’t all bad, though. There were the romances, especially those between Filipino men (the majority of pensionados) and American women. James Charles Araneta—yes, those Aranetas—stayed two years with the Newell family in Berkeley, California, and when he left he took their sixteen-year old daughter, Lillian, with him. As the Aranetas were both wealthy and well-connected in the new American administration—Negrense sugar barons!—the news reports on the match were both breathless and lurid at the same time. It was national news, from the front page of the San Francisco Call to the Des Moines Register to the Pittsburgh Press.

“Berkeley Girl Won by Young Filipino” as reported by the San Francisco Call, above the fold, on February 20, 1906.

“Berkeley Girl Won by Young Filipino” as reported by the San Francisco Call, above the fold, on February 20, 1906.If the groom was less flush, though, an otherwise respectable marriage might be kept secret from friends and family on both sides. That wasn’t enough to stop it from happening, though, so officials in Indiana tried (and failed) to pass a law against whites marrying anyone with more than one-eighth Filipino blood. They portrayed the pensionados not as scholars but as “slick” operators eager to “stain America’s future brown,” in the words of University of Michigan English professor Ruby C. Tapia. This was the world Javier and Georgina had to fight against, and I know the racism in the book was hard for some to read, but reality was far uglier.

Articles from the San Francisco Call and the Valentine Democrat in early 1905.

Articles from the San Francisco Call and the Valentine Democrat in early 1905.Proving that you can never catch a break, returning home was not easy for the Filipinos, either. Generally, pensionados were given immediate supervisory positions over their countrymen, who in turn resented the “Amboys.” On the other hand, the Amboys were not American enough for the Americans in Manila, who refused to admit the pensionados to their private clubs, no matter how Midwestern their education, manners, or dress. Many of these men and women would be pioneers in their fields and are heroes to us now, but at the time they struggled to fit in anywhere.

Eventually, the pensionados would make their own place in society—and it was an exalted one. While only a small part of the population, these 700 men and women educated from 1903-1945 would shape the Philippine Commonwealth and Republic. They became cabinet members, department secretaries, university presidents, deans and professors, designers of national irrigation systems, builders of bridges, lawyers, justices, titans of industry, doctors, archbishops, and, unfortunately, martyrs to the Japanese occupation. Mario Orosa has an extensive list by name and short biography, and it is an impressive read.

The pensionado system will feature in two of my upcoming books, but only one character will pass the test and take the scholarship. Can you guess who? Maybe I shouldn’t tell you. It will spoil the surprise.

March 24, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #18: sipa.

In other words, while wearing a skirt, Allegra lifted her foot almost to hip height, exposing her thighs for several minutes at a time as she bounced an object on her foot in a Filipino version of hacky sack. (By the way, if you think Allegra will give up the pastime as she matures, you don’t have a real good grip on her character. And Javier will ultimately wish that sipa had been his greatest worry for his ward. In book two, Sugar Moon, she will fall for the very worst scoundrel possible—two, actually, though she’ll use one to make the other jealous. She does like mischief.)

In the case of sipa, though, Allegra is at least troublesome in a very patriotic way. “Sipa” or “kick” is a sport that predates the arrival of the Spanish. The earliest sources date to the 11th century in Southeast Asia and maybe all the way back to China’s legendary Emperor Huangdi in 2600 BCE! There are several ancient Moro legends that revolve around sipa. For example, storm gods were said to kick around fireball sipas, and they kicked them so hard that they flew horizontally across the sky (i.e. lightning). Another legend says that the son of the sun and moon fell to earth while playing sipa, igniting a battle over parental supervision that ended in a prehistoric separation, which is why the sun and moon no longer share the sky. Yet another legend tells of a hero bouncing a rattan ball on his foot for two hours straight without fault in order to charm a widow out of her mourning.

When the Americans arrived in 1898, sport became a critical part of their “benevolent assimilation” plans. Yet, while the sanctimonious Yankees did try to eliminate cockfighting (unsuccessfully), they appreciated—or, at least, tolerated—sipa. True, one American called it “a very light form of sport” that was only “suited to an anemic people” and could not compete with “the more stirring games of modern basketball and baseball.” (See post #14 on racism.) However, another American described sipa as “a form of civilized football.” He explained that it “consists of really kicking the wicker ball, rather than the heads, ribs, etc., of fellow players in the game, as is customary in more boastful centers of civilization.”

One constabulary officer pointed out that since Moros used to have slaves to do ordinary work, they spent most of their latent energy on war or sipa. The officer was especially impressed at “the seeming ease with which a man's foot appeared to reach behind and to the level of the opposite shoulder blade.” Sipa was even described in the souvenir brochure to the Philippine exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis World’s Fair) in 1904. The Americans allowed prisoners to play the game in penal colonies—along with basketball, volleyball, and other redeeming pursuits.

Since the earliest time of sipa in the Philippines, there were many regional variations, both in gameplay and in kicking object. There is the community game, where a circle of people keep the object in the air. Or there is the challenge type, where you try to make the most kicks in a row (Allegra’s choice). Or the distance game, where you try to kick it the farthest.

One could use a shuttlecock made of a washer with paper or feather, and this type of fly could be bounced off feet or elbows or hands, depending on preference. A woven rattan ball was used consistently in the Moro lands, which makes sense given the cultural link these areas had with their Malay neighbors. This ball is what is used today in the energetic off-shoot of sipa called sepak takraw—a gymnastic blend of volleyball, badminton, and soccer. The net was added sometime around the turn of the 20th century, and each country has its own claim to put to the invention. (In the Philippines, it is Teodoro Valencia who supposedly created this sipa lambatan in the 1940s.)

Proof of how ingrained this sport was in 20th century Philippine culture, overseas workers took the game with them, even to Alaska. Filipinos working in salmon canneries in the 1930s described playing sipa until ten at night, as long as the daylight lasted.

However, by the 1990s sipa was on the wane. In 2009 President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo dethroned it as the national sport in favor of arnis, a martial art whose popularity has spread even to my small town in New Hampshire. (Known also as eskrima, this Filipino fighting technique will make an appearance in Sugar Moon, too.)

Some folks blame technology for taking kids off the playground and away from their traditional sports, a trend I see happening in the United States, as well. But, as with America, I wonder if our organized sports culture is really to blame. Kids do not run out and play pickup games anymore. They play on teams with coaches, referees, and uniforms. Sipa was actually removed from the elementary division of the Palarong Pambansa (National Games) in 2014. Now even the little ones play “sepak takraw junior,” a modified version of the regional net game. Maybe there is more future in that sport—one can travel and compete throughout ASEAN—but with all this competition, are we losing sight of fun?

Missing sipa? Don’t worry. There’s an app for that. The first Filipino-designed app on iTunes and Android was—yep, you guessed it—SIPA: Street Hacky Sack. There’s terrible irony here, I know, but the app looks beautiful. It takes the user through a tour of cultural Manila and encourages the player to pick up virtual litter along the way. (Genius, that.) In the “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” school of thought, the app is a winner. But I just can’t see Allegra playing it. Too tame.

App (iTunes): https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/sipa/...

App (Android): https://play.google.com/store/apps/de...

Student Filipino-narrated video on sipa: https://youtu.be/pW8jF6s3iRc

Make your own sipa: http://www.wikihow.com/Play-and-Make-...

Philippine Magazine cover:

Congson, Gavino Reyes. "Mother and Child at the Game of Sipa." Philippine Magazine, November 1940, Cover. Accessed March 23, 2016. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acd5869.00....

Other photos used according to Creative Commons by: Sunny Tall, Abel Francés Quesada, Victor Dumesny, Kesavan Muruganandan.

More sources available upon request.

March 12, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term(s) #17: bodbod (also spelled budbud).

Under the Sugar Sun

Needless to say, Georgina liked the bodbod. I mean, what's not to like? Sticky rice with mango alone was responsible for a fifteen-pound weight gain back when I was 19. Add chocolate to that mix? I'm a goner.

I was inspired to write this post because Suzette sent me a picture of a the Budbud-Kabog stall in Legazpi Market in Makati, and I got all jealous, like Fifty Shades of Green. And the owner is from Bais! And he has sugar baron stories! I've got more research to do...checking PAL fares now.

Anyway, bodbod was one of the highlights of my research trip to Bais, Tanjay, and Dumaguete. Apparently, I'm not the only one: Andrews Calumpang wrote a song about the delight, entitled “Ang Budbud sa Tanjay." Tanjay even has a festival to bodbod every third week in December, where they make the world's biggest bodbod (80 kilos) and the world's smallest (fits in a matchbox).

If you're new to street food, you'll notice the eco-friendly banana leaf packaging. Given my fight to extricate new earbuds out of their blister pack this morning, I think we should sell everything in banana leaves. According to Choose Philippines, the antibacterial properties of the coconut oil will keep the bodbod fresh for a week.

All signs point to bodbod! Fate wants me to eat all the sweet treats. It's destiny!

Choose Philippines: http://www.choosephilippines.com/…/lo...

Go to the Bodbod Festival!: http://www.tourism.gov.ph/sitepages/F...

Both photos by Jennifer Hallock, 2010.

Sugar Sun Series Extras

- Jennifer Hallock's profile

- 38 followers