Jennifer Hallock's Blog: Sugar Sun Series Extras - Posts Tagged "glossary"

Sugar Sun series glossary term #1: Calesa.

The calesa, or kalesa, is a two-wheeled carriage drawn by a single horse. It has one or two benches, plus a small seat for the driver (typically up front). Introduced in the 18th century by the Spanish, the calesa was a fashionable and popular mode of transportation in Philippine cities before the automobile. Wealthy people owned their own (and hired their own cochero, or driver) and others rented them for the day or a single ride, like taxis. The going rate in 1908 was 40 centavos for the first hour, and 30 for each additional hour. Tourist calesas can still be seen and ridden in Intramuros (Manila) or Vigan today, but don't try to offer 40 centavos! (Rates start at about 250 pesos, last I heard.)

This colorized photo in the public domain, and was found at the Philippines Photograph Digital Archive at the University of Michigan.

This colorized photo in the public domain, and was found at the Philippines Photograph Digital Archive at the University of Michigan.

Sugar Sun series glossary term #2: Casco.

Since we're on the subject of transportation, we cannot forget the casco—or, as the Americans dubbed them, "lighters." These were the workhorses of Manila. Until 1908 there was no port where ships could dock directly on shore, so cascos were sent out to meet them in the bay. All foreigners, therefore, had their first glimpse of Manila aboard a casco. They would pass Fort Santiago, enter the mouth of the Pasig River, and dock on the north bank, next to the warehouses of Binondo (see photo, also from the Philippines Photograph Digital Archive). A casco pilot often lived in his boat, along with his wife, children, and of course fighting cocks. As a person who raises chickens, I can say that had to smell lovely. Poor family.

Sugar Sun series glossary term #3: Capiz.

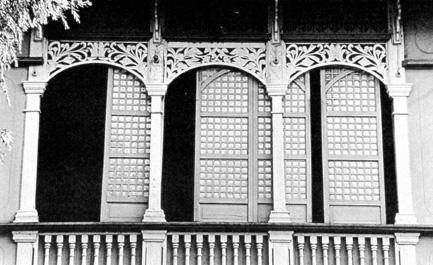

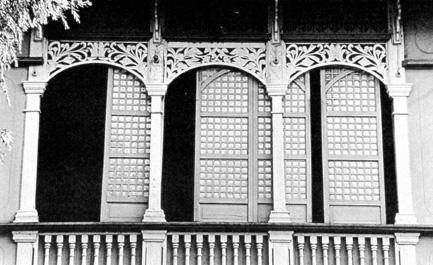

What do you do if you need windows—lots of them—but your country also happens to be prone to earthquakes? Use oyster shells instead of glass, of course! The Placuna placenta is a mollusk found throughout Asia, particularly in mangrove swamps. You can see almost anything made of capiz, or kapis, in the Philippines, but best use has always been the large wooden windows found on traditional houses and buildings (see photo from the "Manila 1571-1898, The West in East" below). The key is to keep the windows closed during the daytime, keeping the sun out, and then open them wide at night to draw in the evening breezes.

Sugar Sun series glossary term #4: Calamansi

This term was originally posted on Facebook on New Year's—appropriate since had you been in the Philippines with your vodka and tonic, you might have spritzed it up with one of these. The calamansi, or kalamansi, is called a lime, but many people compare the taste more to a lemon—or, as I've read recently, to a cross between a lemon and a mandarin orange. I'll have to think about that one. The calamansi does have a unique flavor—deliciousness—which spices up everything from noodles to fish to cocktails. It is quite sour, but there is nothing more refreshing that a calamansi juice on a hot day. Mix in a lot of water and at least some sugar! (Creative commons photos from Flickr: Drew Coffman.)

Sugar Sun series glossary term #5: Tsokolate

Being colonized by Spanish priests put more emphasis on other worldly bliss rather than good old fashioned worldly bliss, like cooking. However, the Spanish did chocolate well, and, in the end, isn't that all that matters? One might think that hot chocolate would not be desirable in a tropical country, but it was not always served steaming hot. And for several months, the weather in the islands can be downright cool—okay, "coolish" to New Englanders. And, okay, only in the mornings, but this is when tsokolate is served. Chocolate in the mornings? Sign me up!

Making it in the early 1900s went like this. First, you had to be sure your lechera (milkmaid) had come and filled the earthen jar in your kitchen. She probably did that in the wee hours of the morning, so you're good. Grab your chocolatera—the brew pot, maybe made of blue enameled metal—and add milk, a chocolate tablea or two (sold in tiny cacao hockey pucks or even handmade balls with ground cashew nut), sugar, and sometimes egg white. The trick is that you cannot just let it burn on the range. You must constantly mix and beat it with your batidor, the wooden implement in the picture above. You swirl the batidor between your palms and it smooths and froths as you cook. The result is thicker and less sweet than American hot chocolate, but it is more true to the Mesoamerican drink the Spanish adopted.

(Creative commons photos from Chip Sillesa and twinkletuason. Tablea photo from Marketman at Market Manila.)

Making it in the early 1900s went like this. First, you had to be sure your lechera (milkmaid) had come and filled the earthen jar in your kitchen. She probably did that in the wee hours of the morning, so you're good. Grab your chocolatera—the brew pot, maybe made of blue enameled metal—and add milk, a chocolate tablea or two (sold in tiny cacao hockey pucks or even handmade balls with ground cashew nut), sugar, and sometimes egg white. The trick is that you cannot just let it burn on the range. You must constantly mix and beat it with your batidor, the wooden implement in the picture above. You swirl the batidor between your palms and it smooths and froths as you cook. The result is thicker and less sweet than American hot chocolate, but it is more true to the Mesoamerican drink the Spanish adopted.

(Creative commons photos from Chip Sillesa and twinkletuason. Tablea photo from Marketman at Market Manila.)

Sugar Sun series glossary term #6: Ilustrado.

Here's the thing about imperialism: every major colonial power sowed the seeds of its own destruction. How? Unwilling to do all the work of running a colony themselves, they sent the best and brightest of every generation off to be educated, sometimes in the home capital itself. Thus, Mohandas Gandhi studied law in London, and even scrappy Ho Chi Minh learned about communism while doing odd jobs in Paris. José Rizal and Antonio Luna, among others, were educated in Spain. Though we may consider these men elites, they often were of middle-class backgrounds. Like the liberal bourgeoisie of Europe, what made the ilustrados different was their education.

I don't know you, but I do know that Rizal was smarter than either you or me. He was conversant in at least 11 languages and could translate another 7. He was an ophthalmologist by training and a patriotic novelist by necessity. And then there's Luna. In addition to arguably being the greatest Filipino general of the Philippine-American War, Luna was also a widely respected epidemiologist and had a PhD in chemistry.

In Europe, these "enlightened ones" were taught the principals of liberal constitutions—rights that we take for granted, such as the freedoms to assemble, speak freely, practice a chosen religion, and have due process of law. All they asked was that these rights apply to the people of the colonies, too. Gandhi, Ho, and Rizal all wanted equality before they wanted independence. When the Europeans would not give it, their hypocrisy was obvious. Though Asian nations did not fully break away until after World War II, the seeds of revolution were planted at the turn of the 20th century with the ilustrados.

I don't know you, but I do know that Rizal was smarter than either you or me. He was conversant in at least 11 languages and could translate another 7. He was an ophthalmologist by training and a patriotic novelist by necessity. And then there's Luna. In addition to arguably being the greatest Filipino general of the Philippine-American War, Luna was also a widely respected epidemiologist and had a PhD in chemistry.

In Europe, these "enlightened ones" were taught the principals of liberal constitutions—rights that we take for granted, such as the freedoms to assemble, speak freely, practice a chosen religion, and have due process of law. All they asked was that these rights apply to the people of the colonies, too. Gandhi, Ho, and Rizal all wanted equality before they wanted independence. When the Europeans would not give it, their hypocrisy was obvious. Though Asian nations did not fully break away until after World War II, the seeds of revolution were planted at the turn of the 20th century with the ilustrados.

Published on January 03, 2016 07:19

•

Tags:

colonialism, colony, glossary, ilustrado, imperialism, luna, rizal, sugar-sun

Sugar Sun series glossary term #7: Hacendero.

When I first chose to write a Fil-Am romance, I had to make my hero a sugar baron to best fit the model of popular Regency historical romance. There are some superficial similarities between my fictional hacienda owner, Javier Altarejos, and a fictional English gentleman, like Jane Austen's Fitzwilliam Darcy. Both came from wealth. Javier grew up in the 1880s and 1890s, when Negros ruled the Philippine (and European) sugar markets. His parents traveled to Europe in the off-season, and they brought back champagne and horses. He grew up in a beautiful local-style mansion, attended by maids, cooks, and nannies. Darcy's income of ten thousand pounds a year was 300 times the average income of the day—some of which could have come from West Indies plantations. And no matter what production of Pride and Prejudice you see, Pemberley is singularly impressive.

However, the true model for Javier (other than Enrique Iglesias, above) was less Darcy and more John Thornton of Elizabeth Gaskell's North and South. (See the 4-part BBC series. You won't be disappointed.) By the time Javier inherits Hacienda Altarejos, the boom times are gone. He has to deal with war (several of them), closed ports, labor shortages, rinderpest and cholera epidemics, drought, and American trade restrictions. Moreover, without a sugar central, his product is no longer the best available. Javier is a good man doing the best he can to keep a major economic enterprise going in tough times. Hacenderos had a reputation of getting rich off the work of their wage laborers, much like the bourgeoisie of industrial Britain—or the fictional factory owners like Thornton. But the reality is that the workers' jobs depended on Javier and Thornton keeping their doors open, which was not a simple task.

This is not a blanket defense of hacenderos. My story has some "sugar coating." It is romance, after all!

(Note: Hacendero is the older Spanish spelling, though you will often see haciendero in the Philippines and elsewhere. However, in my research, the version without the added i was more popular in contemporary sources.)

However, the true model for Javier (other than Enrique Iglesias, above) was less Darcy and more John Thornton of Elizabeth Gaskell's North and South. (See the 4-part BBC series. You won't be disappointed.) By the time Javier inherits Hacienda Altarejos, the boom times are gone. He has to deal with war (several of them), closed ports, labor shortages, rinderpest and cholera epidemics, drought, and American trade restrictions. Moreover, without a sugar central, his product is no longer the best available. Javier is a good man doing the best he can to keep a major economic enterprise going in tough times. Hacenderos had a reputation of getting rich off the work of their wage laborers, much like the bourgeoisie of industrial Britain—or the fictional factory owners like Thornton. But the reality is that the workers' jobs depended on Javier and Thornton keeping their doors open, which was not a simple task.

This is not a blanket defense of hacenderos. My story has some "sugar coating." It is romance, after all!

(Note: Hacendero is the older Spanish spelling, though you will often see haciendero in the Philippines and elsewhere. However, in my research, the version without the added i was more popular in contemporary sources.)

Published on January 03, 2016 07:28

•

Tags:

austen, darcy, enrique-iglesias, gaskell, glossary, hacendero, hacienda, north-and-south, pride-and-prejudice, richard-armitage, sugar-sun, thornton

Sugar Sun series glossary term #8: Insurrecto.

Though the conflict began over events in Cuba, America fought its first battle of the Spanish-American War in Manila. Historians debate what President McKinley's intentions were—did he want to take the Philippines in its entirety, just keep Manila, or defeat Spain and leave? But, as they say, "appetite comes with eating." Once the Americans had Manila, they wanted all the islands. Only problem? The Philippine revolutionaries who helped defeat the Spanish did not want the Americans to stay—and they controlled most of the rest of the country.

Instead of calling what followed a war—assuming two equal adversaries—the Americans called it the Philippine Insurrection—with only one legitimate authority. (The Spanish sold the islands to the Americans for $20 million in December 1898, which was the basis of their legal claim. On what authority the Spanish sold the Philippines, that is another question.) So instead of calling the Filipinos revolutionaries, patriots, or nationalists, they called them insurgents, bandits, and ladrones. (The last two are the same thing, the latter in Spanish.) The favorite American term, though, was insurrecto (insurrectionist).

Now the conflict is called the Philippine-American War, and it officially lasted from 1899 to 1902, though hostilities did not fully end until 1913. Despite the name change, Filipinos after 1899 are rarely called revolutionaries, even in the more balanced American textbooks. In my books, I use the term insurrecto whenever Americans are speaking because that term is true to the period. It is not a political statement (as you could probably tell by the tone of my posts).

Instead of calling what followed a war—assuming two equal adversaries—the Americans called it the Philippine Insurrection—with only one legitimate authority. (The Spanish sold the islands to the Americans for $20 million in December 1898, which was the basis of their legal claim. On what authority the Spanish sold the Philippines, that is another question.) So instead of calling the Filipinos revolutionaries, patriots, or nationalists, they called them insurgents, bandits, and ladrones. (The last two are the same thing, the latter in Spanish.) The favorite American term, though, was insurrecto (insurrectionist).

Now the conflict is called the Philippine-American War, and it officially lasted from 1899 to 1902, though hostilities did not fully end until 1913. Despite the name change, Filipinos after 1899 are rarely called revolutionaries, even in the more balanced American textbooks. In my books, I use the term insurrecto whenever Americans are speaking because that term is true to the period. It is not a political statement (as you could probably tell by the tone of my posts).

Published on January 03, 2016 09:14

•

Tags:

glossary, insurrecto, mckinley, philippine-american-war, spanish-american-war, sugar-sun, treaty-of-paris

Sugar Sun series glossary term #9: Carabao.

The carabao is the national animal of the Philippines. It's a good choice because this beast of burden can do everything. It can haul a house's worth of goods (up to 3500 kilos or 7700 pounds), turn a mill stone, or carry several passengers for hours. It is your pick-up truck, tractor, and engine all in one. A contemporary observer wrote that the carabao was "patient and tractable so long as he can enjoy a daily swim. If cut off from water the beast becomes irritable [and] will attack men or animals and gore them with its sharp horns." Americans were a bit dramatic, of course. They resented the carabao for clogging carriage traffic as it lumbered through Manila at two miles per hour.

The true test of the carabao's usefulness is that there are still 3.2 million in the Philippines. According to a 2005 United Nations report, "99 percent belong to small farmers that have limited resources, low income, and little access to other economic opportunities." At the dawn of the 20th century, though, every farmer and hacendero relied upon the carabao, which is why the rinderpest epidemic of 1901 hurt the islands so badly. This was one of Javier Altarejos's biggest problems at the beginning of the book: finding the money to replace his herd.

The true test of the carabao's usefulness is that there are still 3.2 million in the Philippines. According to a 2005 United Nations report, "99 percent belong to small farmers that have limited resources, low income, and little access to other economic opportunities." At the dawn of the 20th century, though, every farmer and hacendero relied upon the carabao, which is why the rinderpest epidemic of 1901 hurt the islands so badly. This was one of Javier Altarejos's biggest problems at the beginning of the book: finding the money to replace his herd.

Sugar Sun series glossary term #10: Thomasite.

In August 1901 over five hundred American teachers arrived in Manila aboard the USAT Thomas, and the term "Thomasite" was born. A strategy begun by the Army to "pacify" the islands, the American colonial authorities established a coeducational, secular, public school system throughout the Philippines. Often seen as the best thing the Americans did in the islands, it is not without its critics. Here's the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The Good: Many Thomasites were flexible, adventurous people who truly loved their students and their host towns. Some never left. I modeled Georgina Potter on some of these people, including Mary Fee, who will come up again. The best, most democratic administrator was David Barrows, who emphasized solid academic subjects like reading, writing, and arithmetic so that Filipinos could find professions, not just jobs. He also implemented a test-based scholarship system to American universities, which will be the topic of another post. Barrows opened more schools and trained Filipino teachers to take them over—something now termed sustainable development.

The Bad: In his time, Barrows was considered a failure because Filipino students were not achieving to the level of Americans in standardized testing—yes, back then we were just starting to "teach to tests." A thinking person might understand that this is because Filipino students were being taught in a foreign language. This is a good time to mention that everything was taught in English. Why? The Americans said that Filipinos had not learned enough Spanish to justify that medium, and the local languages were too many and too varied to be practical. And, let's face it: Americans, particularly the Easterners and Midwesterners who came to the Philippines, only spoke English. Moreover, they already had the textbooks printed. Hence, Filipino boys and girls were learning poems about snowflakes. Huh? Fortunately, Mary Fee and others rewrote some of these early readers with local themes, proving that not all Yankees are idiots.

The Ugly: The next superintendent after Barrows returned the educational system to its original focus: industrial education, based on what were then called "negro schools" in the States. White (really his name) thought that Filipinos should be taught "practical subjects" like carpentry and gardening, as well as "character training" like cleanliness and conduct. (Such prejudice was so prevalent at the time that English-speakers had not yet coined the word "racism." It was simply the norm.) And then there were some individual Americans who, in the words of Javier Altarejos, were "unfit for travel abroad." Harry Cole, stationed in Palo, Leyte, wrote that "when I get home, I want to forget about this country and people as soon as possible. I shall probably hate the sight of anything but a white man the rest of my life." Archie Blaxton channels good ol' Harry quite a lot. Fortunately or unfortunately, I did not have to make up horrible, racist stuff for my characters to say. I just looked up what real Americans did say. It was not encouraging.

In the end, the educational program was successful in making Filipinos believe that a brighter future was possible under the Americans—not fighting the Americans. Whether this was cynical manipulation by the colonial government or a sincere intention to do good abroad, that's up to you. From my research, the two were tied up together in what President McKinley termed "Benevolent Assimilation." Many Filipinos did like the schools, and they certainly respected their teachers. Most importantly, some families managed to do what Barrows wanted: to "destroy that repellent peonage or bonded indebtedness" in which they found themselves. And the Thomasites gave me great plot ideas, so I'm not complaining.

The Good: Many Thomasites were flexible, adventurous people who truly loved their students and their host towns. Some never left. I modeled Georgina Potter on some of these people, including Mary Fee, who will come up again. The best, most democratic administrator was David Barrows, who emphasized solid academic subjects like reading, writing, and arithmetic so that Filipinos could find professions, not just jobs. He also implemented a test-based scholarship system to American universities, which will be the topic of another post. Barrows opened more schools and trained Filipino teachers to take them over—something now termed sustainable development.

The Bad: In his time, Barrows was considered a failure because Filipino students were not achieving to the level of Americans in standardized testing—yes, back then we were just starting to "teach to tests." A thinking person might understand that this is because Filipino students were being taught in a foreign language. This is a good time to mention that everything was taught in English. Why? The Americans said that Filipinos had not learned enough Spanish to justify that medium, and the local languages were too many and too varied to be practical. And, let's face it: Americans, particularly the Easterners and Midwesterners who came to the Philippines, only spoke English. Moreover, they already had the textbooks printed. Hence, Filipino boys and girls were learning poems about snowflakes. Huh? Fortunately, Mary Fee and others rewrote some of these early readers with local themes, proving that not all Yankees are idiots.

The Ugly: The next superintendent after Barrows returned the educational system to its original focus: industrial education, based on what were then called "negro schools" in the States. White (really his name) thought that Filipinos should be taught "practical subjects" like carpentry and gardening, as well as "character training" like cleanliness and conduct. (Such prejudice was so prevalent at the time that English-speakers had not yet coined the word "racism." It was simply the norm.) And then there were some individual Americans who, in the words of Javier Altarejos, were "unfit for travel abroad." Harry Cole, stationed in Palo, Leyte, wrote that "when I get home, I want to forget about this country and people as soon as possible. I shall probably hate the sight of anything but a white man the rest of my life." Archie Blaxton channels good ol' Harry quite a lot. Fortunately or unfortunately, I did not have to make up horrible, racist stuff for my characters to say. I just looked up what real Americans did say. It was not encouraging.

In the end, the educational program was successful in making Filipinos believe that a brighter future was possible under the Americans—not fighting the Americans. Whether this was cynical manipulation by the colonial government or a sincere intention to do good abroad, that's up to you. From my research, the two were tied up together in what President McKinley termed "Benevolent Assimilation." Many Filipinos did like the schools, and they certainly respected their teachers. Most importantly, some families managed to do what Barrows wanted: to "destroy that repellent peonage or bonded indebtedness" in which they found themselves. And the Thomasites gave me great plot ideas, so I'm not complaining.

Sugar Sun Series Extras

Illustrate the Sugar Sun Series with maps of the islands and Manila in 1902, as well as an annotated glossary of terms unfamiliar to some American readers. If you would like to view my blog (from when

Illustrate the Sugar Sun Series with maps of the islands and Manila in 1902, as well as an annotated glossary of terms unfamiliar to some American readers. If you would like to view my blog (from whence these came) go to jenniferhallock.com. Thank you!

...more

- Jennifer Hallock's profile

- 38 followers