Jennifer Hallock's Blog: Sugar Sun Series Extras, page 17

May 2, 2017

Mogul and the Chinese Exclusion Act: An Interview with Joanna Shupe

Award-winning author Joanna Shupe writes the men of Edwardian era New York like no other. While some are born to the Knickerbocker Club set, others are self-made titans of industry. But whether they are from Five Points or Fifth Avenue, they are all swoon-worthy. In Mogul, one will battle a real historical injustice: the racist immigration laws of the late nineteenth century.

She never expected to find her former husband in an opium den.

Thus begins Mogul, Shupe’s last book in the Knickerbocker series. Calvin Cabot, the son of humble American missionaries in China, has grown up to become one of the most influential men in America. Even with his lucrative newspapers and powerful friends, though, can he find a way around one of the worst laws of the Gilded Age—the Chinese Exclusion Act—to reunite a friend’s family?

In this post, Joanna Shupe answers our questions about the Chinese Exclusion Act and how she came up with the idea to work such substantive history into the conflict of her novel.

What was the Chinese Exclusion Act, and how will it affect your characters?

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, signed into law by President Arthur, severely limited the ability of Chinese men and women to enter the United States. It’s the most restrictive immigration policy the U.S. has ever had to date and wasn’t repealed until the early 1940s.

So why were Chinese immigrants singled out? In the 19th century, America was undergoing a massive transformation. The Gold Rush and the railroad expansion led to the need for cheap labor, and many Chinese immigrants (mostly men) were able to find jobs here. Gradually, anti-Chinese sentiment increased, polarized by a few politicians who used the Chinese immigrants as excuses for why wages remained so low. Their solution was to call for the banning of any Chinese laborer, thereby freeing up those jobs for American workers.

Starting in 1882, no Chinese laborer could enter the United States—and it was nearly impossible to prove you weren’t a laborer. Only diplomatic officials and officers on business, along with their servants, were considered non-laborers, so the influx of Chinese immigrants came to a near standstill. They also tightened the rules for reentry once you left, which meant families were separated with little hope of ever reuniting.

How effective were the Chinese Exclusion Acts at excluding the Chinese? For the last half of the 1870s, immigration from China had averaged less than nine thousand a year. In 1881, nearly twelve thousand Chinese were admitted into the United States; a year later the number swelled to forty thousand. And then the gates swung shut. In 1884, only ten Chinese were officially allowed to enter this country. The next year, twenty-six.

— “An Alleged Wife: One Immigrant in the Chinese Exclusion Era” by Robert Barde, Prologue Magazine, National Archives, Spring 2004, Vol. 36, No. 1.

Mogul is set in 1889, and circumstances have separated the hero’s best friend from his wife, who is still back in China. His best friend is African American, so they decide to tell politicians and the government that she is really the hero’s wife. This presents a problem when the hero falls in love with—and impetuously marries—the heroine of the story.

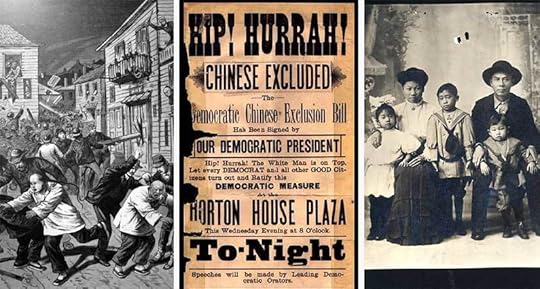

Racist illustrations from Australia and the United States.

Racist illustrations from Australia and the United States.This sounds like a pretty sobering piece of history. What inspired you to use the Exclusion Act as a central plot line in Mogul?

I started with this idea that my hero would be discovered in an opium den in New York City, so that was where my research began. I didn’t remember the CEA from my history classes, so I was floored when I discovered it. It’s tragic and racist, and yet seems still so relevant today.

As romance novelists, we love to find conflict for our characters. I thought the CEA might be an interesting way to drive the story forward. I wanted to both highlight the xenophobia of the CEA and use the forced familial separation to craft the plot.

From left: illustration of 1880 anti-Chinese riot in Denver; poster celebrating the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act; photo of Chin Quan Chan and family at the National Archives.

From left: illustration of 1880 anti-Chinese riot in Denver; poster celebrating the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act; photo of Chin Quan Chan and family at the National Archives.What kind of research did you need to do on the act itself and on the Chinese-American community in general? Do you have any sources that you recommend for students and researchers?

I read quite a bit online about the CEA and the effects of the legislation. The 19th century Chinese-American community was fascinating to research. A good friend of mine is Chinese-American, and I peppered her (as well as her family) with lots of questions about the language and culture. They were all very patient and helpful.

I used mostly archives of The New York Times for tidbits about Chinatown, opium, and the Tongs, which is how I saw a mention of the game fan tan and began researching that. As with most historical research, you can fall into a rabbit hole pretty easily because it’s all so fascinating.

Centerfold of “Uncle Sam’s Lodging House” from 7 June 1882 edition of Puck, accessed at the U.S. Library of Congress.

Centerfold of “Uncle Sam’s Lodging House” from 7 June 1882 edition of Puck, accessed at the U.S. Library of Congress.In a genre that some claim is about “escapism,” did you encounter any resistance to using this real history as a conflict in your book—either from editors, publisher, or readers?

I didn’t receive any resistance about this storyline, per se, but I’ve had readers tell me that they won’t read any historical set in America. The reason given is they can’t “romanticize” it the way they can with British history.

While I understand what they’re saying—after all, we’ve lived and breathed American history in school since Kindergarten—I don’t agree. We can’t assume we know everything in our history so well that we can’t learn something new or enjoy a compelling story. There’s so much history that isn’t taught—or isn’t taught well—and looking into the past gives us the clearest view of where we are today.

The Gilded Age is one of our finest eras…but also one of our nation’s low points. In each of the Knickerbocker Club books, I’ve tried to highlight some of the issues and problems as well as the opulence and wealth.

April 25, 2017

#RTRoadTrip is about to begin…

April 19, 2017

The Writer’s Toolbox: Character Development

Do you need to name a hero or heroine? Plan your heroine’s pregnancy? Determine the color of a child’s eyes? I do, too! Let’s go misuse the interwebs, shall we?

I suppose most people use naming sites to name their real children, not their imaginary ones. But we authors name more people than Octomom on a fertile day, so we need a site for power users. At , you can search names by letter, gender, derivation, usage, history, meaning, keyword, length, syllables, sound, and more. Its historical popularity tables include all of the data for American names. And, if you find something you like in Spanish usage, for example, it will give you every possible related name in other cultures. It even has a family tree for names. Moreover, you can ask it to randomly generate a name according to your criteria. The “submitted name” feature even allows you to browse the latest monikers that are not “official” in any country’s lexicon, keeping you ahead of the trends. There is a surname section, too! It is a very powerful tool, and I have used it in my Sugar Sun series from the very beginning. (I also browse names in cemeteries, which I cannot recommend highly enough, especially for historical fiction. You can bring those names back and read about them on this site.)

Okay, now you’re confused. What do random numbers have to do with fiction writing? Well, if you are a little obsessive about your characters, then…everything! I determine birthdays, anniversaries, number of children a couple has, how much a bribe costs, and more through the use of truly random numbers. Need to flip a coin, but don’t have any change on you? Random.org will do that for you, too. It will also pick your lottery numbers, practice your jazz scales with you, and randomly generate short prose. These last few features I cannot guarantee.

And, speaking of calendars, timeanddate.com is very powerful. You can quickly search the calendar of any year in any country. Wait, Jen, isn’t the calendar the same in all countries? No, there are many alternative calendars—Chinese, Islamic, Hebrew, Mayan, and others—all of which are on this site. But, more importantly, even though most countries have adopted the Gregorian calendar for civil use, not every country has the same weekend or holidays. This site has them all.

How about moon phases? If you write a night scene, don’t you want to know how much light there was outside? The site also has a sunrise, sunset, eclipse, and seasons calendar. (If you need tides, I like Tides4Fishing, which has historical data back a few years.)

I also frequently use the date duration calculator to figure out exactly how old my character is on a particular day. This is helpful when writing a series that spans several years. It will also tell you what years have the same calendar as the historical year you might be using. You can find out, for example, that 1815 (if writing Regency) or 1905 (my Edwardian series) both share the same calendar as 2017. This means that more limited internet calendar tools—like those below—can now be used with success. Just use the modern year that has the same calendar as the year you really want.

“Whoa, Jen! That’s an overshare! We don’t need to know about your menses.” No, I don’t use this myself. I mean, I could, but I’m not that organized about my own life. But I will find out every detail about my heroine’s ovulation, cramps, and menstruation. This kind of woman-centric focus is why I dig romance. In fairness, contemporary romance may gloss over periods of “indisposition” or “women’s troubles” because we have tampons and ibuprofen, thank the heavens. But in historical romance, I want to know when my characters are going to be inconvenienced—even if nothing is mentioned in the book. (Yes, I’m a little obsessive.) Now, thanks to Tampax’s Period Tracker, I know all: PMS time, heaviest flow, post-period, and peak ovulation. For people who don’t exist. I’m so messed up.

My characters screw like bunnies (ahem, romance!), and since they live in a Catholic country in the Edwardian period, conventional contraception is hard to find. So my ladies do get preggers. And since I, the author, have no children, what do I know about pregnancy? Very little. So I have Baby Center. Their due date, conception, and week-by-week pregnancy calendars are very helpful. You can also chart your heroine’s cycle with them, but it is a little more detailed than the Tampax site, and there is discussion of mucus, so enter at your own risk.

The Tech Museum of Innovation and the Stanford School of Medicine’s Department of Genetics did not create this eye color site for authors, but it is a brilliant tool for us. It is a part of a larger online exhibit on genetics. The scientists behind the site would tell you that their model is oversimplified, but since I have not had to take a real science class since high school, I think it’s perfect. But they also walk you through adding a little complexity to the model with these instructions.

You can either examine your results through numerical probability or through a random selection of six children produced by the model. In my work-in-progress, Sugar Moon, the heroine Allegra has a Spanish, blue-eyed biological father. Even though her mother was Filipina-Chinese, and despite Allie and her mother having brown eyes, she and her blue-eyed hero, Ben, have better than a 1 in 3 chance of a blue-eyed child. They could even produce a green-eyed baby (about a 13% chance), since Ben’s mother had green eyes, and his sister, Georgina, has green eyes. Are we having fun yet? I could play with this stuff for days.

Speaking of color, descriptions of skin tone can get offensive quickly. Using food is fetishizing, cliché, and worse. If you have questions on this premise, read more from Colette at the Writing with Color blog. Here, though, let me direct your attention to part two of this series where Colette gives many wonderful suggestions, clarifications, and resources to help you decide what to use. It is not just about sensitivity; it’s about good writing, no matter who your characters are. I highly recommend the whole site.

And so concludes the first in my writer’s toolbox series of posts. I hope these sites are as useful to you as they have been to me. Happy character creating, and happy writing!

April 14, 2017

Research Notes: Harper’s History of the War in the Philippines

Do you remember the days of card catalogs? Or the days when, if your library did not have the book you wanted, you had to wait weeks—maybe months—for interlibrary loan? (And that was if your library was lucky enough to be a part of a consortium. Many were not.) Even during my college years, I made regular trips to the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., because that was the only place I knew I could find what I needed. Since I could not check out the books, I spent a small fortune (and many, many hours) photocopying. I still have their distinctive blue copy card in my wallet.

The point is that “kids these days” are lucky. Do I sound old now? Sorry, not sorry—look at the wealth of sources on the internet! With the hard work of university librarians around the world, plus the search engine know-how of Google and others, you can find rare, out-of-print, and out-of-copyright books in their full-text glory.

Today, I (virtually) paged through an original 1900 copy of Harper’s History of the War in the Philippines to bring you some of the original images that you cannot find anywhere else. For example, you may know that almost every village in the Philippines—no matter how remote or small—had a band of some sort, whether woodwind, brass, or bamboo. In fact, these musicians learned American ragtime songs so quickly and so enthusiastically that many Filipinos thought “There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight” was the American national anthem. You may know this, but can you visualize it? You don’t have to anymore. Here is an image in color:

Full color image from the Harper’s History of the War in the Philippines, accessed at Google Books.

Full color image from the Harper’s History of the War in the Philippines, accessed at Google Books.Smaller bands than the one pictured above played at some of the hottest restaurants in Manila, like the Paris on the famous Escolta thoroughfare. I have seen the Paris’s advertisements in commercial directories, but I had never seen a photo of the interior of it (or really many buildings at all) since flash photography was brand new. Harper’s had a budget, though, so they spared no expense to bring you this image of American expatriate chic:

Image from the Harper’s History of the War in the Philippines, accessed at Google Books.

Image from the Harper’s History of the War in the Philippines, accessed at Google Books.Not every soldier or sailor ate as well as the officers at the Paris. The soldiers on “the Rock” of Corregidor Island, which guards the mouth of Manila Bay, had a more natural setting for their hotel and restaurant:

Image from the Harper’s History of the War in the Philippines, accessed at Google Books.

Image from the Harper’s History of the War in the Philippines, accessed at Google Books.Another interesting image is of a “flying mess” (or meal in the field). Notice the Chinese laborers in the bottom right hand corner. Despite banning any further Chinese immigration to the Philippines with the renewal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1902, the US government and military regularly employed Chinese laborers who were already in the islands.

Full color image from the Harper’s History of the War in the Philippines, accessed at Google Books.

Full color image from the Harper’s History of the War in the Philippines, accessed at Google Books.But enough politics. It’s almost the weekend, so this relaxing image might be the most appropriate:

Image from the Harper’s History of the War in the Philippines, accessed at Google Books.

Image from the Harper’s History of the War in the Philippines, accessed at Google Books.Want to learn how to find such cool sources yourself? Next weekend, on April 22nd at 1pm, I will give my research workshop, The History Games: Using Real Events to Write the Best Fiction in Any Genre, at the Hingham Public Library, in Hingham, Massachusetts. The hour-long workshop is free, but the library asks that you register because space is limited. Follow the previous library link, if interested. Hope to see you there!

(Featured banner image of card catalog from the 2011 Library of Congress Open House was taken by Ted Eytan and is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.)

April 4, 2017

Welcome to the Sugar Sun Series

Chronological Order*

*All books are standalone HEAs (happily-ever-afters) and do not have to be read in order.

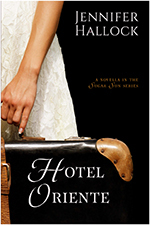

The Oriente is the finest hotel in Manila… but that’s not saying much.

Hotel manager Moss North already has his hands full trying to make the Oriente a respectable establishment amidst food shortages, plumbing disasters, and indiscreet guests. So when two VIPs arrive—an American congressman and his granddaughter Della—Moss knows that he needs to pull out all the stops to make their stay a success.

That won’t be easy: the Oriente is a meeting place for all manner of carpetbaggers hoping to profit off the fledgling American colony—and not all of these opportunists’ schemes are strictly on the up-and-up. Moss can manage the demanding congressman, but he will have to keep a close eye on Della—she is a little too nosy about the goings-on of the hotel and its guests. And there is also something very different about her…

Find Hotel Oriente at Amazon.com.

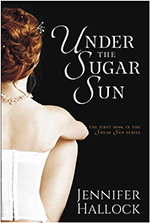

A schoolmarm, a sugar baron, and a soldier…

It is 1902 and Georgina Potter has followed her fiancé to the Philippines, the most remote outpost of America’s fledgling empire. But Georgina has a purpose in mind beyond marriage: her real mission is to find her brother Ben, who has disappeared into the abyss of the Philippine-American War.

To navigate the Islands’ troubled waters, Georgina enlists the aid of local sugar baron Javier Altarejos. But nothing is as it seems, and the price of Javier’s help may be more than Georgina can bear.

Find Under the Sugar Sun at Amazon.com.

A Missionary and a Sinner

Jonas Vanderburg volunteered his family for mission work in the Philippines, only to lose his wife and daughters in the 1902 cholera epidemic. He wishes his nurse would let him die, too.

Rosa Ramos wants nothing more to do with American men. Her previous Yankee lover left her with a ruined reputation and a child to raise alone. A talented nurse at a provincial hospital, she must now care for another American, this time a missionary whose friends believe her beyond redemption.

Find Tempting Hymn at Amazon.com.

April 1, 2017

Sugar Sun series glossary term #32: Ah Tay bed

I just wrote a hot sex scene for Sugar Moon that prominently features a wooden Ah Tay bed. It definitely makes an impression:

Ben’s hips flattened against hers, pinning her shoulder against the bed post. He nudged Allie harder and harder against the wood until she felt the carved floral pattern tattoo her skin.

I bet you’re wondering what that would look like—the carved bed post, not the sex. You can use your imagination with the sex.

An antique Ah Tay bed on auction. Leon Gallery opened the bidding at 160,000 pesos, or just over $3200. Salcedo Auctions hoped to get 350,000 pesos, or $7000, for theirs.

An antique Ah Tay bed on auction. Leon Gallery opened the bidding at 160,000 pesos, or just over $3200. Salcedo Auctions hoped to get 350,000 pesos, or $7000, for theirs.The elaborate four-poster Narra frame, with its intricately carved Art Nouveau posts, was the creation of Eduardo Ah Tay, an ethnic Chinese furniture maker in Binondo. The kalabasa, or squash-shaped, dome design became “a status symbol for the nineteenth century mestizo elite” in their bahay na bato houses.

Cheaper beds—versions not made by Ah Tay—had spiral posts. They were not as desirable as an Ah Tay but were still better than sleeping on the floor. However, if you were expecting a mattress on any of these platforms, think again.

“Look here, North,” the congressman said. “You gave us unmade rooms!”

Moss had checked the rooms himself. “What are you missing, sir?”

“Most of my bed!” Holt huffed. “Why, there isn’t a stitch of bedclothes on the blooming thing. Not even a mattress! I raised the mosquito-netting and found nothing but a bamboo mat.”

— Hotel Oriente, prequel novella to the Sugar Sun series.

Holt’s confusion was based on a real story of an irate newcomer to the Hotel de Oriente. The rattan platform, mattress-less bed was known among Americans for being “springless, unyielding, and anything but comfortable,” or “an instrument of torture, a rack, an inspirer of insomnia.” Even Philippine Commissioner Dean Worcester called the Philippine bed “that serious problem.”

Two photos of the “sleeping machine” at the Hotel de Oriente from the Burton Holmes Travelogue.

Two photos of the “sleeping machine” at the Hotel de Oriente from the Burton Holmes Travelogue.The real genius of the bed though was air flow. Woven rattan was both perforated and strong, which made it the go-to technique for a lot of local furniture, including the sillon chair. This ingenuous use of local materials kept you cool before the advent of air conditioning.

Eventually, Commissioner Worcester came to like the bed—he even regarded it a luxury of the tropics. Traveler Burton Holmes agreed the bed had been “unjustly ridiculed and maligned.” He said, “It is…perfectly adapted to local conditions, a bed evolved by centuries of experience in a moist, hot, insect-ridden tropic land, and from the artistic point of view is not unattractive.”

Left: A modern-sized reproduction of an Ah Tay bed in the Museo sa Parian (1730 Jesuit House) in Cebu. Photo by Looney Planet. Right: A large Ah Tay at Casa Consuelo Museum at Villa Escudero Plantations in San Pablo, Laguna, as photographed by the Philippine Inquirer.

Left: A modern-sized reproduction of an Ah Tay bed in the Museo sa Parian (1730 Jesuit House) in Cebu. Photo by Looney Planet. Right: A large Ah Tay at Casa Consuelo Museum at Villa Escudero Plantations in San Pablo, Laguna, as photographed by the Philippine Inquirer.But don’t try to sleep on an original Ah Tay: not only might it be in delicate condition, but most are far too small. (Humans have gotten bigger—both taller and rounder—in the last 120 years.) There is a decent sized one at the Casa Consuelo Museum in Tiaong, Quezon, and its owners even claim that it—and everything in the house—is authentic. Or you can build yourself a modern-sized reproduction, complete with solid mattress frame, like at the Museo sa Parian in Cebu.

Either way, this is the type of bed where Allegra Potter will bring her handsome, six-foot-plus suitor, Ben Potter. This is where she will debauch him in Sugar Moon. Look for it in late 2017.

Try an Ah Tay reproduction out for yourself at the Hotel Felicidad, photographed by InterAksyon.

Try an Ah Tay reproduction out for yourself at the Hotel Felicidad, photographed by InterAksyon.(The featured image is an architectural drawing by interior design student Marinelli Fabiona.)

March 24, 2017

Sugar Sun series location #7: Balangiga

My upcoming book, Sugar Moon, will be firmly rooted in history that I believe every American should know: the ambush of a company of American soldiers on September 28, 1901, in Balangiga, Philippines. Most people have never heard of it. What happened that day in Balangiga—and in the months of American counterattacks afterward—has been overshadowed by other towns that Americans do know, ones with names like My Lai and Fallujah. Had we learned the lesson of Balangiga, though, these two towns in Vietnam and Iraq might never have hit the headlines. In fact, they might not be noteworthy at all.

My photo of fishermen in Balangiga, at the junction of the Balangiga River and the Leyte Gulf. From there, it is not far until you are in the Pacific Ocean.

My photo of fishermen in Balangiga, at the junction of the Balangiga River and the Leyte Gulf. From there, it is not far until you are in the Pacific Ocean.How did I stumble upon Balangiga? When I started plotting my story about an American schoolteacher and a Filipino sugar baron—the story that became Under the Sugar Sun—I did a lot of research at Ateneo de Manila University, where I read through old issues of the Manila Times on microfiche. (By the way, if you want to entertain me, give me two rolls of that microfiche and leave me there all day. It’s like giving a child an iPad. History is my babysitter.) One of the articles I stumbled across was entitled: “Sister Hunting for Brother: His Name is E.L. Evans and He is Supposed to Be in the Philippines.” From there, I conjured up the idea of a missing brother to bring Georgina Potter to the Philippines. Yes, she was hired by the American colonial government to start a school in the Visayas, but her real motive in coming—and for letting herself get entangled with a jerk named Archie—was finding her brother, Ben Potter.

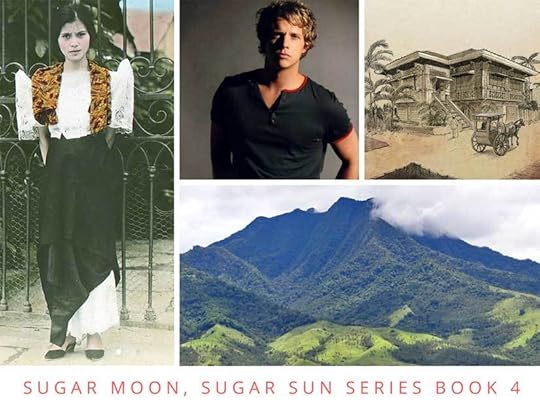

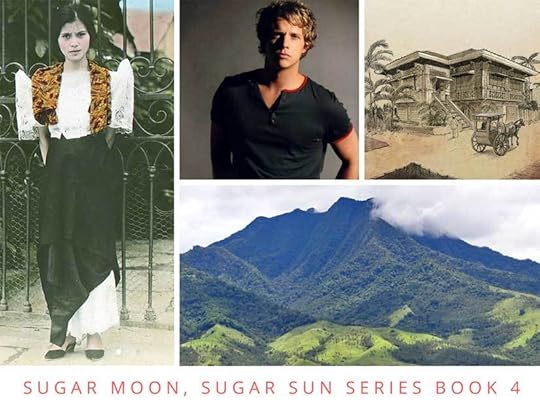

A character board for Sugar Moon. From left: a Filipina in 1900 who inspired Allegra Alazas; actor Chris Geere, one of my possible “castings” for Ben; a local house; and Mount Suiro on Biliran Island, location of some adventures. Sorry, no more spoilers!

A character board for Sugar Moon. From left: a Filipina in 1900 who inspired Allegra Alazas; actor Chris Geere, one of my possible “castings” for Ben; a local house; and Mount Suiro on Biliran Island, location of some adventures. Sorry, no more spoilers!Why was Ben missing? Maybe because he was in a significant battle? Or, at least, a very confusing one? In Under the Sugar Sun, Georgina goes to Army Headquarters in Fort Santiago in Manila to find out, and she lays out all the news articles from a battle in Balangiga. A clerk tries to help her, to no avail:

“Your brother should be in here one way or another.” The clerk put his finger on the article with the list. “Name and rank?”

If it were that easy, she thought, she would not have bothered crossing the Pacific. “Sergeant Benjamin Potter.”

“I see a Ben Cutter,” the clerk said. “That’s probably him.” He sounded sure, as if the Army made such mistakes all the time. Maybe they did. He would know.

Georgie pulled another article to compare side by side. “Half the names are spelled differently from one day to another,” she explained. “Cutter one day, then Carter, then Palmer. And here all of the Boston soldiers are described as dead. All of them! My mother and I bought every paper, every edition, for a month, trying to find a new official list that made any sense. And you know what the Army told us? Nothing! No telegram, no letter, nothing.” She was not normally one to create a scene, but she had come a long way for the truth, and she was going to get it.

The confusion of names and numbers really did happen, which is one of the reasons why I chose this setting for my character. It makes sense that if he survived, he still might not want to be found. Several survivors stayed in the Philippines afterward, much to the chagrin of their families.

So, it was decided: Ben served in Company C, Ninth Infantry, which saw action in China during the Boxer War, and then returned to the Philippines to be stationed in Balangiga. Poor Ben. Poor Balangiga.

Company C occupied this town, and occupation is ugly. It doesn’t matter how you justify it—in this case, blockading the southern coast of Samar so that the guerrillas in the mountains could not be resupplied, a legitimate military purpose. It also doesn’t matter if the occupation starts off peacefully, which it did in Balangiga. It is not going to stay that way. The lesson of occupation throughout world history—no matter whether we are talking about ancient Greek occupation of Jerusalem, Israeli occupation of Lebanon, the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, or the American occupation of the Philippines—things will go downhill.

The Americans called the Filipino guerrillas insurrectionists, and they labeled what happened in Balangiga a massacre, implying that the perpetrators had no just cause. On the other side, Filipinos call their soldiers revolutionaries, and they see the event itself as a just uprising. If you want to avoid all judgment, it was an incident, or more specifically an ambush. I am greatly indebted to Philippine historian Rolando O. Borrinaga and British writer Bob Couttie for their first-hand research and outstanding work on Balangiga. In my version of the story, I have taken some liberties—merging characters to simplify things for the reader, renaming a few people—but I hope that my unwitting mentors will find that I got the big brush strokes right. All errors are my own, of course.

Two outstanding scholars on the Balangiga Incident, Rolando O. Borrinaga and Bob Couttie. Bottom right is my photo of the monument to the attackers in Balangiga town.

Two outstanding scholars on the Balangiga Incident, Rolando O. Borrinaga and Bob Couttie. Bottom right is my photo of the monument to the attackers in Balangiga town.As we will see in Sugar Moon, at first things went okay. Uneasily, but okay. An American officer played chess with the parish priest. The man Sergeant Benjamin Potter is based on studied martial arts with the police chief. Individuals got along. But here’s the rub: if the townspeople became too friendly with the Americans, they would face retribution from the revolutionaries up in the mountains. So the town tried to play it cool, stay neutral.

The southern coast of Samar is not the easiest place to patrol. This is the Cadacan River near Basey. Image courtesy of Iloilo Wanderer on Wikimedia Commons.

The southern coast of Samar is not the easiest place to patrol. This is the Cadacan River near Basey. Image courtesy of Iloilo Wanderer on Wikimedia Commons.But the Americans noticed some strange things happening—like sweet potatoes planted in the jungle for the guerrilla soldiers, or townspeople not cutting down banana trees that could provide the guerrillas cover—and the Yanks thought they had been betrayed. They ordered the town to cut down essential food sources, to “clean up” the town. If the town complied, not only would they need to destroy their own property, they would also endanger the understanding they had with guerrillas. I think you probably see where this is going. The reality of a town like this during occupation is that it will be caught in between two armies, and if neither army can truly protect the civilians against the other, the people must try to play one off the other. That is a dangerous game.

Company C doubled down. They imprisoned the town’s men in conical tents that looked like Native American teepees. These Sibley tents were supposed to sleep 16, but were each jammed full with over 70 men and boys, who had to sit on their haunches all night. They were not fed dinner, and in the morning they were forced to cut down the food their families depended on. This went on for several days.

Several African-American Union Army Teamsters rest on a Sibley tent in 1865, giving some sense of their size (and age). It is a crowded sleep for 16 inside, let alone 70 or more. Winslow Homer’s The Bright Side, is in the public domain. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Several African-American Union Army Teamsters rest on a Sibley tent in 1865, giving some sense of their size (and age). It is a crowded sleep for 16 inside, let alone 70 or more. Winslow Homer’s The Bright Side, is in the public domain. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.The Americans did not see the town turning against them. They only saw their own frustration: they felt alone, vulnerable, on the edge of a hostile island, a day’s travel away from the nearest garrison. Yet they did not expect the ambush. My character Ben will narrate the whole debacle through his flashbacks, which starts with him trying to court a local woman. He’s a proper gentleman, don’t worry, but he’s smitten. This, by the way, is based on a real possible romance between an American sergeant and the local prayer leader of the town.

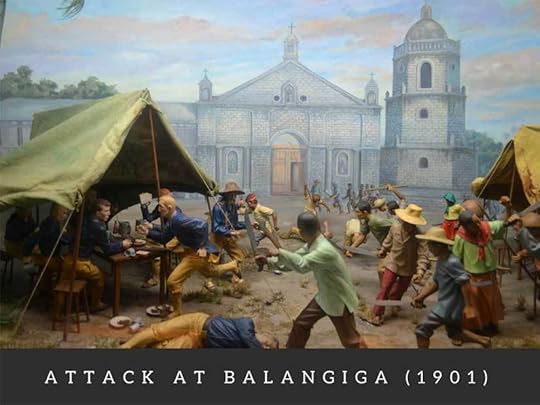

On Sunday, September 28, 1901, the morning after the town fiesta, a church bell rang. Nothing unusual about that—until men dressed as women streamed out of the church with machetes. The American soldiers were eating breakfast. Dozens would die immediately and gruesomely. A little more than half would manage to escape, but several of them would die along the way of their wounds or from other attacks. In total, 48 of 77 Americans would die.

One of many wonderful dioramas designed by the Ayala Museum and now viewable through the Google Cultural Institute.

One of many wonderful dioramas designed by the Ayala Museum and now viewable through the Google Cultural Institute.Americans blamed the Filipino revolutionaries for streaming out of the jungle to attack the town, but the truth Borrinaga and Couttie uncovered is that the town actually planned the attack themselves. They may have borrowed some men from villages outside Balangiga proper, and they may have coordinated with the revolutionaries, but this was a town fighting back against the soldiers who had imprisoned them.

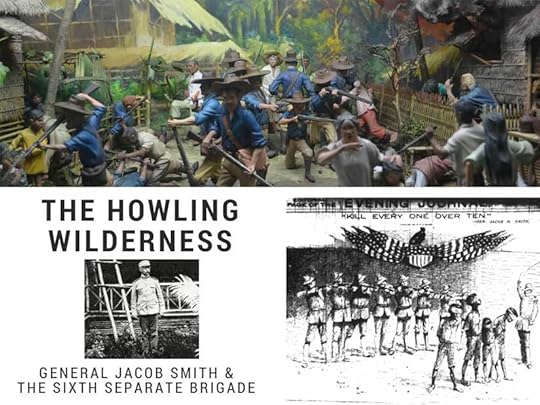

After that, all hell broke loose. If there is something more violent than the rising up of an occupied people, it is the revenge exacted by a conventional military force armed to the teeth. The American commander in Samar ordered his men to turn the entire island into “a howling wilderness” by striking down all men and boys capable of carrying arms, which he defined as all those over ten years old. (That’s not legal, by the way.) His men made a special trip back to Balangiga to burn down the town and kill anyone in sight. Months of revenge resulted in the deaths of thousands on Samar, maybe as many as 15,000, according to Borrinaga.

Another of the many wonderful dioramas designed by the Ayala Museum and now viewable through the Google Cultural Institute. Also included are a photo of General “Hell-Roaring Jake” Smith and the New York Journal editorial cartoon of his order. Both are in the public domain and are found on Wikipedia.

Another of the many wonderful dioramas designed by the Ayala Museum and now viewable through the Google Cultural Institute. Also included are a photo of General “Hell-Roaring Jake” Smith and the New York Journal editorial cartoon of his order. Both are in the public domain and are found on Wikipedia.This was the My Lai moment of the Philippine-American War, and it was just as explosive to the American public as that incident in Vietnam was. For the first time, with the advent of the trans-Pacific telegraph cable, the American public could follow events with an immediacy that had been previously impossible. The excesses of the Army now blanketed newspapers and magazines Stateside. Though military authorities tried to censor the press by controlling the telegraph lines out of Manila, reporters got around this by traveling to Hong Kong to wire their stories. The courts-martial of several American officers made daily headlines, and Senate hearings began on the issue of American atrocities in the Philippines.

The survivors of Balangiga in April 1902. Photo in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The survivors of Balangiga in April 1902. Photo in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.But how do you criticize the methods of occupation without questioning the whole endeavor to begin with? You can blame a few “bad apples” to satisfy the public, but is it enough? The general in Samar received a slap on the wrist from the court-martial that followed, and though popular outcry in the US later forced President Roosevelt to demand the general’s retirement, the punishment still didn’t fit the crime. The general retired with a full pension. The American lieutenant in command at My Lai, convicted of murdering 22 Vietnamese civilians, served only seven months of house arrest and then was pardoned.

A military hospital in Manila. Photo in the public domain.

A military hospital in Manila. Photo in the public domain.My character Ben tried hard to be better than the rest, but what happened in Balangiga tortures him. You are not supposed to have liked him in Under the Sugar Sun, and he does not like himself much, either. He suffers from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, something that two of my very best friends share with him. Soldiers with PTSD struggle with guilt, depression, substance abuse, anger management, insomnia, and other health problems. I am greatly indebted to these friends for letting me put some of their worst fears on the page. I hope they will also appreciate the redemptive journey Ben goes through and the healing power of love that he finds. They would tell me this is far too simplistic a cure, but I think they want Ben to have a happily-ever-after, so it’s okay.

George Santayana wrote in 1905: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” It is fitting he said so at the outset of what was later called the American Century. The vigorous debate about the use of military force abroad—and it’s aftereffects like PTSD—are familiar to people today. But they were not really a part of American discourse until the Philippine-American War. America’s professional army was born out of this war. Before 1898, the entire US Army was smaller than today’s New York City Police Department. Most of the Spanish-American War had to be fought with state volunteers whose enlistments lasted only a year. When hostilities broke out in Philippines, Congress promptly doubled the size of the regular army once, and then doubled it again. For the first time in its history, America had a significant standing army stationed far from its borders. And yet no one learned from Balangiga.

Maybe it is not good enough to just remember the past. You should experience it yourself. That’s the garden where empathy grows. That’s where you get all the feels. I hope Sugar Moon helps.

Photograph of an American reconcentrado camp, the exact tactic we blamed Spain for in Cuba.

Photograph of an American reconcentrado camp, the exact tactic we blamed Spain for in Cuba.

March 17, 2017

Spring into Romance!

My wonderful trip to Manila may be over (sigh), but that doesn’t mean sabbatical is over. In fact, since I don’t start the day job until September, I still have half a year left. What will I do with all that time?

I am currently editing Sugar Moon, Ben Potter’s redemption story. What woman is strong enough to bring this man to heel? There’s only one. Allegra Alazas, Javier’s spitfire cousin. This story is a grittier and more suspenseful than the others. Interested? Look for a late 2017 release. (Then, yes, Sugar Communion is next. That’s Andrés’s story. He’s a tough one.)

I also have some great reader and author events coming up. In addition to attending RT Booklovers Convention for the first time, I am helping to plan a smaller, more intimate conference right here in the Boston area. I am the assistant chair of the New England Chapter of RWA®’s Let Your Imagination Take Flight 2017 conference. In addition to all the amazing workshops, we have a big signing on the night of April 7th. Your favorite authors will be there, there will be over 20 baskets of books and goodies to win in our free raffle, and there’s a cash bar! See more details at the linked pages or in the banner at the top of this page.

By the way, I will be donating another #MabuhayLove basket to the raffle. The books might be slightly different (I picked up new ones in Manila!), but the concept is the same: emotionally-satisfying, beautifully written global romance.

Finally, I will be doing my research workshop one more time. It’s called The History Games: Using Real Events to Write the Best Fiction in Any Genre. The Hingham Public Library has invited me back to speak to their patrons on April 22nd at 1pm. As with all events I do for libraries, it is free! If you’re in the area, come check it out.

Thank you all for helping make my sabbatical the best year ever! Another big thank you to all the authors and readers who welcomed me so warmly in Manila. It was thrilling to meet all my #romanceclass friends in person. You guys are truly the best.

And, in case you missed it, Tempting Hymn is out and has been getting some nice buzz on social media. Thank you to all those who have helped others find my books by leaving a review. I really do appreciate the time it takes to share your thoughts.

March 10, 2017

Manila Tour 2017

I spent the last two weeks of February on an amazing trip to the Philippines. Packing everyone I wanted to see into 14 days—plus romance events!—was a little insane, but I made the most of every minute.

The #PHRomCon2017 Steamy Panel of Awesomeness: Bianca Mori, Georgette S. Gonzales, me, and Mina V. Esguerra. (I’m only awesome because of the company I’m keeping.)

The #PHRomCon2017 Steamy Panel of Awesomeness: Bianca Mori, Georgette S. Gonzales, me, and Mina V. Esguerra. (I’m only awesome because of the company I’m keeping.)I started the business end of things with an appearance at the Philippine Romance Convention 2017, hosted by the Romance Writers of the Philippines at Alabang Town Center—a mall that happens to be my old stomping grounds. I was honored to sit on the Steamy Romance Panel with Mina V. Esguerra, Georgette S. Gonzales, and Bianca Mori. These are three outstanding authors. Mina’s Iris After the Incident is such an important, sex-positive, feminist contemporary romance that I wrote a whole blog post about it. Georgette writes intense romantic suspense that tackles politics, corruption, and more. And Bianca’s globe-trotting romantic suspense Takedown trilogy is like a cocktail of Ocean’s 11 and Mr. and Mrs. Smith, but with more sex. It goes without saying that this was an amazing evening.

While I was there, author Ana Valenzuela and I grabbed a coffee at Starbuck’s so we could chat. That chat eventually turned into this hugely flattering article in the Manila Bulletin, the leading broadsheet newspaper in the Philippines.

A lovely article introducing the Sugar Sun series to the Philippine general reader. You can find a digital copy of the article at the Manila Bulletin.

A lovely article introducing the Sugar Sun series to the Philippine general reader. You can find a digital copy of the article at the Manila Bulletin.But I’m getting ahead of myself. Before that came out, I was able to do some awesome traveling that provided me inspiration for both my current Sugar Sun series and my anticipated second generation series, which will be set during World War II. I headed to Corregidor with three great friends: my amazing hostess and great friend, Regine; my former student and now accomplished Osprey pilot, Ginger; and Ginger’s husband, Tread, also an Osprey pilot.

Left: Ginger and me on the ferry to Corregidor. Right: the “tail” of the island, which is shaped like a tadpole.

Left: Ginger and me on the ferry to Corregidor. Right: the “tail” of the island, which is shaped like a tadpole.Even though I have been to the island several times, even staying the night before, I find each return trip gives me new ideas. I pick up different tidbits on the tour every time. This time, in the Malinta Tunnel, I heard about the crazy parties the Americans threw at the very end, when they expected to be defeated any day. They needed to consume their supplies before the Japanese arrived, and they really needed to get out of that tunnel at night. What happened under the stars, on the beach, when no one was watching? Yep, that is romance material, if I’ve ever heard it. A celebration of life in the midst of death.

Left: Regine and I on the ferry to Corregidor. Right: The Statue of MacArthur exclaiming, “I shall return!” (He did. It was a whole thing.)

Left: Regine and I on the ferry to Corregidor. Right: The Statue of MacArthur exclaiming, “I shall return!” (He did. It was a whole thing.)Only a few days later, I was on the other side of the channel, on the Bataan Peninsula. This, of course, is the site of the infamous Bataan Death March, where 76,000 Filipino and American soldiers were force marched over 100km without food or water. Tens of thousands died. This is not good romance novel material. But each marker we passed was a reminder of the sacrifice of others who came before.

Left: Bataan Death March markers at every kilometer along the road. They really make you aware of what happened here over seventy years ago. Right: A memorial to the Battle of Manila, which ended in February 1945.

Left: Bataan Death March markers at every kilometer along the road. They really make you aware of what happened here over seventy years ago. Right: A memorial to the Battle of Manila, which ended in February 1945.Regine and I had gone to Bataan to see some even older history—particularly the heritage homes being preserved at Las Casas Filipinas de Acuzar. On the one hand, I loved this place. It is a resort made up of bahay na batos, bought and moved from all over the Philippines. And, with no other cities or villages in sight, you can almost imagine that this is what Manila looked like during the time of the Sugar Sun series—if you squint your eyes to avoid seeing the ATM machine hidden in the bottom floor of one of the houses. The guides are informative, and the location by the sea is breathtaking. And, if given the choice between having a house moved here and letting it deteriorate or be bulldozed, then the choice seems obvious. With all these homes in one place, a person can truly appreciate the proud architectural tradition of the islands.

However, there are down sides, too. First, these homes are not in their original context, to be appreciated by those who have some claim over their heritage. They are also glorified hotel rooms, rented out for exorbitant prices by the park’s creator. Unlike a national museum, this park is for profit, and it is not cheap to get to, nor stay at. Therefore, the history of the Philippines cannot be equally shared among all Filipinos. Also, the location by the sea is questionable because the salty air will accelerate deterioration. Finally, there are a dozen building projects going on at a time, and meanwhile those already built or moved are degrading. It feels a little like a resort built by someone with ADHD—once one thing is halfway done, it gets pushed aside for a shiny new toy.

Left: The Hotel de Oriente and me! Right: The view out our hotel window to the heritage bahay na bato across the square. Parts of

Heneral Luna

were filmed here.

Left: The Hotel de Oriente and me! Right: The view out our hotel window to the heritage bahay na bato across the square. Parts of

Heneral Luna

were filmed here.But, it is beautiful. And I got to see a recreation of the Hotel de Oriente! I felt like I should be giving out copies of my novella at the door—but, alas, I did not have any with me. The building looked accurate on the outside, but there are no surviving photos of the inside, so they have improvised. And while I applaud them hiring all local craftsmen to do the ornate inlaid woodwork, this interior makes the a Baroque palace look minimalist. Still, I was thrilled to be there. It was a huge rush.

These amazing trips led up to the big event: the combined lecture of “History Ever After” at the Ayala Museum and the release of Tempting Hymn! It was such an amazing day. I talked for an hour about the history of the American colonial period, the Philippine-American War, and the Balangiga Incident. I wove in information about all my characters, even showing character boards with the casting of famous movie stars in the roles of each hero and heroine. (Piolo Pascual as Padre Andrés Gabiana was a special favorite.) I gave some special attention to the new novella, and then I signed and sold all the books I had brought with me. (One whole piece of checked baggage was just books!)

Left: The #romanceclass community comes out to see me at History Ever After. Thank you! Center: Me talking. Look how huge that projector screen was! Right: At the signing with Nash and Carole Tysmans.

Left: The #romanceclass community comes out to see me at History Ever After. Thank you! Center: Me talking. Look how huge that projector screen was! Right: At the signing with Nash and Carole Tysmans.What a fantastic day, and I have to thank the whole #romanceclass crowd for coming out. You guys were amazing! Thanks to Mina Esguerra and Marjorie de Asis-Villaflores organizing the event. It would not have been possible without you. And thank you to my wonderful friend Regine, my advisor, therapist, and accountant—as well as the best hostess ever.

The Transitio commemoration: burning prayers on the walls of Intramuros (left) and the arts festival on the grounds (right).

The Transitio commemoration: burning prayers on the walls of Intramuros (left) and the arts festival on the grounds (right).Regine and I spent my last evening in Manila at Intramuros at the 8th Annual Manila Transitio Festival commemorating the 100,000 dead in the Battle of Manila, 1945. Under the leadership of performer and popular historian extraordinaire, Carlos Celdran, we made wishes on the walls of Intramuros, listened to great music, ate great food, and even drank some buko (young coconut) vodka. Yep, that’s a thing.

Left: Ben and I at the Oarhouse. Right: Ben, Gina, Paul, Derek, me, and Regine at Fred’s Revolución in Escolta.

Left: Ben and I at the Oarhouse. Right: Ben, Gina, Paul, Derek, me, and Regine at Fred’s Revolución in Escolta.While much of this trip was devoted to writing, one of the truly best parts of being back was seeing my wonderful friends again, including people who have known my husband and me for over 20 years. The Philippines are beautiful, but it is the people who make this place so unforgettable. The fact that two of these people, Ben and Derek, now own three of the best bars in Manila doesn’t hurt, either!

Amazingly, I survived this whirlwind trip, but it only made me anxious for more. I cannot wait to go back. I need to write more books to justify the next trip, so off I go to write, write, write…!

March 3, 2017

American Colonial Missionaries in the Philippines

Once upon a time, Catholic-Protestant strife scorched Europe. In the seventeenth century, for example, about eight million people died in the Thirty Years War, almost a tenth of the estimated total population. Germany’s male population was cut by nearly half. There were also civil wars in France, England, Scotland, and Ireland, killing millions more. The Troubles in Northern Ireland in the late twentieth century were less deadly, but still deadly.

So intra-Christian conflict is not that unusual. Yet, far away in the Pacific, Spanish rule kept the competition away from Philippine shores. From northern Mindanao on up, there was no choice but Catholicism. When a hundred or so Yankee missionaries arrived on Philippine shores around 1900, though, things changed. There was no armed conflict, but the competition was still fierce. At least, the Protestants thought it was fierce. But over a hundred years later, only a small proportion of the Philippine population identify as Protestant—between two and ten percent, depending on whether you include independent nationalist movements with the American imports. Yet, despite this relatively small number, early American missionaries still had a significant impact on the face of Filipino society.

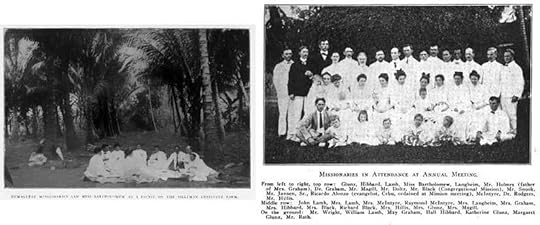

Presbyterian missionaries at Silliman University in Dumaguete, as pictured in The Assembly Herald.

Presbyterian missionaries at Silliman University in Dumaguete, as pictured in The Assembly Herald.American Protestants did not want to see the return of the Spanish friars who had fled the country in the 1896 Philippine Revolution, and so they spread themselves out as widely as possible throughout the islands, taking up positions in vacated towns. They divided the large islands among themselves: the Presbyterians got Negros and Samar; Panay went to the Baptists; Mindanao went mostly to the Congregationalists; and Luzon was split between the Presbyterians, Methodists, and United Brethren. Only the Seventh Day Adventists and Episcopalians did not ratify this agreement.

A picture of Silliman University dating from 1909 at the earliest.

A picture of Silliman University dating from 1909 at the earliest.Silliman University in Dumaguete was begun by the Presbyterian missionary couple David and Laura Hibbard. In my Sugar Sun series, I’ve renamed the school Brinsmade and taken a lot of liberties with the characters, but it’s not all fiction. A lot of the general priggishness that comes out of the mouth of my character Daniel Stinnett, president of Brinsmade, is stuff American missionaries really said or wrote down. In my new novella, Tempting Hymn, you get a very intimate look at what these communities might have been like. My hero, Jonas, is a good man whose ecumenical faith will be challenged by some of the more small-minded missionaries with whom he works. It was important to me that Rosa and Jonas find common ground in a world complicated by church politics and colonial attitudes. I sometimes get to write what I wished had happened in history.

Character board for

Tempting Hymn

.

Character board for

Tempting Hymn

.And, it is true, the missionaries did do some good work. First, they could be more inclusive than normal colonial officials. They offered opportunities for Filipinos to join their ranks as members, ministers, and missionaries. At Silliman, a Filipino had to pass an examination and earn the members’ vote, but if he or she (most likely he) did so, he could be tasked to spread the word throughout the rest of Negros and Cebu islands. By 1907, only six years after the founding of Silliman, there were five ordained Filipino ministers. They could preach in their vernacular languages—in fact, it was encouraged in order to reach a wider audience.

An assembly of students at Silliman Hall, reprinted from the

Sillimanian

.

An assembly of students at Silliman Hall, reprinted from the

Sillimanian

.The other key advantage of the missionaries’ presence were the services they provided, particularly in education and health. Silliman was a school, after all. The American missionaries understood that the Thomasites, the American public school teachers, were doing good work, but they still thought that a secular curriculum was incomplete. David Hibbard integrated religion into the regular coursework and included several prayer sessions a week, including three commitments on Sunday. But Silliman’s reading, writing, and arithmetic education did not suffer because of it. In fact, his students had good success in finding employment in the new colonial government:

One boy, Andres Pada, who came to us a raw unlikely specimen three years ago has been appointed an Inspector of the Secondary Public School building and is giving good satisfaction. Another boy named Apolonario Bagay has been appointed as overseer of the roads for a portion of the province and is doing good work there. Four or five of the boys have gone out this year as teachers in the public schools of the province, and though they have not had enough training to do very good work yet, I have heard no complaints.

Okay, that seems like being damned with faint praise, but it was quite complimentary by American missionary standards. And Silliman was so popular in the region that they had more applicants than they could handle. They had to turn away boarders and take only “externos,” or day students. The local elites embraced the Hibbards and Silliman in general. In 1907, Demetrio Larena, the former governor of Negros Oriental province (and brother to the mayor of Dumaguete), converted to Presbyterianism. Silliman is now one of the best private universities in the Philippines, and it might have grown strong partly because of the very favorable town-gown relations, right from the start.

Reverend Ricardo Alonzo, the first Presbyterian minister, and ex-Governor Demetrio Larena, Presbyterian convert, from The Assembly Herald.

Reverend Ricardo Alonzo, the first Presbyterian minister, and ex-Governor Demetrio Larena, Presbyterian convert, from The Assembly Herald.American missionaries did more than educate, though. They also brought medical personnel to Asia. Interestingly, several of these doctors were women. In the Presbyterians’ list of new missionaries in June 1907, there were three single female doctors—two were sent to China and one to the Philippines. Another woman physician, Dr. Mary Hannah Fulton, started a medical college for women in China. One female doctor, Rebecca Parrish, will be the model for a future character of mine, Liddy Sheppard, heroine of Sugar Communion. Parrish founded the Mary Johnston Hospital and School of Nursing in an impoverished area north of Manila, and she would give 27 years of service there before retiring. In 1950 Philippine president Elpidio Quirino bestowed upon her a medal of honor for her work. I’ve taken some liberties (as I do), but her passion for providing a safe place for women to give birth will translate to my heroine, Liddy.

Pictures of Dr. Rebecca Parrish, third from the left in the first photo. Images courtesy of She Has Done a Beautiful Thing for Me by Anne Kwantes.

Pictures of Dr. Rebecca Parrish, third from the left in the first photo. Images courtesy of She Has Done a Beautiful Thing for Me by Anne Kwantes.Of course, you might wonder why Christians would want to spread their faith to other Christians—until you realize that, at the turn of the century, many American Protestants did not think Catholics were Christians. They put “papists,” as they called them, right along side infidels, idolators, and heretics. Reverend Roy H. Brown said:

Three hundred years have passed since this people first heard the Gospel from the Catholic Priests, and yet their condition morally is appalling….Saints and Mary are revered and worshiped while Christ is forgotten, and His place usurped….They know nothing about Christ or the Bible; their religion is a mixture of paganism with Christianity with the religious nomenclature.

This bias included a proscription against marriage to Catholics. In the Presbyterian version of the Westminster Confession of Faith at the end of the nineteenth century, it said that those who “profess the true reformed religion should not marry with infidels, Papists, or other idolaters, neither should such as are godly be unequally yoked by marrying with such as are notoriously wicked in their life or maintain damnable heresies.” Since they did not consider marriage a sacrament, you did not have to marry in a church—but the church was still going to tell you whom to marry. I fudged the rules a bit in Tempting Hymn when I allowed Jonas to marry Rosa, a Catholic, though his Presbyterian friends are none too happy about it. (And, you may remember that in Under the Sugar Sun, Georgina and Ben’s parents’ Catholic-Protestant marriage had been a scandal back in Boston.)

Some more pictures of Silliman University that inspired my Brinsmade Institute, including the chapel and bell tower that Jonas plans to build (left) and the houses like the one in which Jonas and Rosa lived (right). Photos courtesy of The Assembly Herald in 1907 (left) and 1906 (right).

Some more pictures of Silliman University that inspired my Brinsmade Institute, including the chapel and bell tower that Jonas plans to build (left) and the houses like the one in which Jonas and Rosa lived (right). Photos courtesy of The Assembly Herald in 1907 (left) and 1906 (right).There were some more progressive missionaries, of course. In fact, the first Presbyterian missionary to arrive in the Philippines, Rev. Dr. James D. Rodgers, said that the purpose of the mission was “to help Christians of all classes to become better Christians.”

Still, in the end, the Protestants had more in common with each other than with the Catholics. And since the enemy of my enemy is my friend, the American denominations—the Presbyterians, Disciples of Christ, Evangelical United Brethren, Philippine Methodists, and the Congregational Church—would decide to merge into the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP). It was their hope that this would provide more unity to fight the Catholic front.

It was not very successful. These more traditional churches would end up losing the war to the nationalized independent churches (like Iglesia ni Cristo), along with the Seventh Day Adventists and more recent missionaries like the Jehovah’s Witnesses. But, in the end, numbers may not matter. The real impact these missionaries would have would be social and academic, not spiritual.

Featured image of an old Dumaguete postcard.

Sugar Sun Series Extras

- Jennifer Hallock's profile

- 38 followers