Jennifer Hallock's Blog: Sugar Sun Series Extras, page 14

August 29, 2017

Jennifer Hallock’s Advice for New Teachers

Teaching can be one of the most emotionally rewarding professions out there, which is why most teachers still scrape by on the low salary. (Notice that I did not say “accept the low salary” because I do not accept it. This country’s priorities are totally screwed up.)

The best part of the job is when your students tell you that you’ve made a positive difference in their lives. This may be an academic difference (you sparked a life-long interest in a subject) or a personal boost (you gave the support that he or she needed to deal with a tough problem). If you are a new teacher, trust me: both of these things will happen…eventually.

Why the teachers of my generation became teachers: we thought we would be like Robin Williams in

Dead Poets Society

.

Why the teachers of my generation became teachers: we thought we would be like Robin Williams in

Dead Poets Society

.But do not shoot for popularity right out of the gate. In the teenage world, popularity is fleeting—and it is not handed out for the best of reasons. I mean, you have seen Breakfast Club or Mean Girls, right? (Or, my favorite, Heathers? It’s a little twisted.)

Respect means so much more than popularity. Even if a student does not like your subject, does not like his or her grade, or does not even like you, he or she might still respect what you do and how you do it. That will have to be enough.

The following is what I have learned in twenty-two years in the classroom:

[Note: These twenty-two years were all spent in college-prep high schools. This does not mean my advice cannot apply to a more general educational environment (whether continuing education, at-risk youth, or college). But it might not. I don’t know. Use your best judgment.]

Kids will not judge you by where you went to college or graduate school, so take that silly pennant off the wall. In fact, the more impressive the name of the school you went to, the less they want to know about it. It reminds them too much of their own college stress.

They will not judge you by what you know, but by how well you explain what you know. That is one of your jobs as a teacher: to untangle, sort, classify, and construct digestible chunks of information for your students.

There is nothing less cool than an adult trying to be cool. Kids want a captain at the helm of the ship. Not a Captain Ahab on a fanatical mission, or a cruel, by-the-book Captain Bligh—but a captain, nonetheless. You are asked to evaluate students—in a permanent, and sometimes public way—and they must trust your maturity, experience, and judgment to do so.

If you have to discipline a student, pull him or her aside and speak privately. Remember that students are learning how to be adults, so treat them how you want them to treat others.

Have a sense of humor. Even better, have patience. When you’ve lost your patience, you’ve lost the room.

Remember that the kids believe their time is valuable: every minute in class is a minute not learning another subject, not running on a field, not making friends, not flirting, not eating, and (most importantly) not sleeping. They have stuff to do, and to them none of this stuff is trivial. So, if they have to be in your class, make it count.

A lot of folks will give you the advice to “warm up” your class for five minutes by talking about their lives or the latest tv shows. Here’s my problem with this idea: by shaving off time here or there, you are teaching your students that class time is subjective. How can the first five minutes not be important when the remaining minutes are? Because you are the teacher and you say so? (This kind of specious reasoning does not fly in teenager-ville.)

I treat every minute of class time as valuable. When the bell rings, we get started. Yes, I tend to start by making announcements, which is a warm up of sorts. I might even talk about current events that are directly relevant to your class material. But I expect my students to pay attention. In fact, I expect them to pay attention all the way until the bell rings again. And, if I have time left over after my planned lesson is finished (ha!), I always have a backup activity or two that I can throw in: review, writing, upcoming prep, etc.

One caveat: if you teach longer than 50-minute class periods, I understand the need to break the class into two “sessions,” with a small break in the middle. But once the break is over, get back to it.

If you have nothing of value for your students to read, write, or drill at night, do not give them make-work. My subject, history, is full of endless reading, but I never, ever, ever give students an assignment that I have not pre-read and pre-approved. If there is a middle section to that reading that is not valuable, or is boring, or is badly written, I cut it out or tell them to skim it. If you give students a bad assignment, they will no longer prioritize your work in the future. Teenagers are rational actors…sometimes.

While I do not teach classes that are pivotal to the college admissions process—I teach 9th grade, before they are applying, and 12th grade, as they’re sending in the forms—my students still do the homework in my class. They even claim to find it interesting. Are the Bhagavad Gita or Enuma Elish really relevant to their lives? (Well, they might be—the Gita, in particular. Its themes are timeless!) But I think my kids read this stuff because I give them pieces that are accessible, important, and interesting. (And challenging, too, but a reasonable challenge.)

As my former colleague and star teacher, Rachelle Sam, says: “Leave room for zest.” Students will find anything interesting if you can show them it is interesting. I teach world religions, and my students have a game going every year (which I do not encourage) about which tradition I call my own. They actually debate this question with each other, and almost every religion we study is in the mix. I hope that this means that I am treating each unit with equal enthusiasm and esteem.

A scene from Teachers (1984), with Richard Mulligan as Herbert Gower, a “wandering mental institution outpatient mistaken for a substitute teacher and put in charge of a U.S. History class” (Wikipedia). His enthusiasm for the job was infectious.

A scene from Teachers (1984), with Richard Mulligan as Herbert Gower, a “wandering mental institution outpatient mistaken for a substitute teacher and put in charge of a U.S. History class” (Wikipedia). His enthusiasm for the job was infectious.

One reason that energy is so important is that you are teaching students how to approach the material. They will remember how you tackled difficult problems, how you found answers to questions you did not know, and how much you truly enjoyed the journey. You are teaching them how to learn. That is far more important than content, which they will not remember so well in a few years. (Remembering it for the test is hard enough for many of them.)

Now, you might notice that I have said two seemingly contradictory things: (1) your job is to communicate content, but (2) they will not remember content. Both may be true, but that does not mean teach nothing at all. Students need to learn rigor and skills, but they can only do so by working with content. Hold them accountable for a reasonable amount of material—but know that in the medium and long term, they will remember you and the skills you taught them more than that stuff you talked about.

Plan your assignments to build upon each other. Start with the most discrete building block of a skill, and then add to it in successive assessments. For example, before I ask students to write a 750-word essay, they need to be able to construct a proper thesis statement. Otherwise, what are they writing about?

This sounds obvious, but you would be surprised by how many veteran teachers just throw excrement at a wall to see what sticks. If you have not figured out what you are trying to accomplish in the classroom, that is your problem, not your students’. Do not ask kids to find meaning when you cannot.

I am ruthlessly organized. “Obsessive” has been bandied about. Fortunately, kids like an organized teacher.

For all my classes, students are given the syllabus for the entire term (or year!) on day one. They know what the plan is for today, what it is for tomorrow, next week, for exam prep, and so on. In this way, it is like a college course. I can do this because I have taught the same courses several times (ahem…dozens of times) in a row. But even by year two or three, I had a working syllabus going.

Why? It goes back to valuing kids’ time. They know that their back-to-back travel game nights are going to get busy, so they want to get ahead with the history reading. Guess what? They can! They have the syllabus in their notebooks and online. (Pro tip: I don’t date my syllabus. It’s Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, etc. in order.)

As you can probably tell from the above advice, I over-prepare for every lesson, new or old. Even if I have taught the lesson 23 times, I still go over my notes. I reread most of the readings every time, too. (Admittedly, it’s a little easier when you are re-reading something that you have already annotated and highlighted. That’s a point I make to my students while teaching note-taking.) Reviewing everything is important: the material must be as fresh to you as it is to them. If your students know better than you what was included in the reading you assigned, then shame on you.

Now, let’s say you’ve put together the best lesson plan of all time. I mean, they should give you a Nobel Prize of Lesson Plans based on this thing, right? But you might still need to scrap it. Sometimes, you realize that the students are not ready for what you’ve prepared. Or, gulp, your technology fails you. Improvise. Be flexible. Figure it out. Think on the fly. Make those minutes count. Teach it a new way.

This matters in class and in your assessments. It is okay to be a tough teacher. You may think the “cool teachers” give everyone good grades, but here’s a secret: smart kids want to earn their grades. They want to achieve something they did not think previously possible. And they do not want to get the same grade as a kid who half-assed it. If you give everyone an A, they will know you do not respect their effort or their time.

Never, ever, ever have “A students.” Every student comes into an assessment as a totally new individual. If a normally top kid turns in crappy work, then he or she gets a crappy grade. (If that student is truly capable, he or she will recover.)

All of this seems so obvious, but the biggest complaint that I hear from students is that a teacher has pegged them as an 82, and no matter how hard they work on something, they get essentially the same grade. This is a big problem in essay grading, which can be somewhat subjective. How can you be sure that you are grading the work fairly? Well…

I hate eduspeak acronyms and pedagogical platitudes. But I do like using good rubrics. Design your own. They keep you honest. Let me use an example from teaching history. Compare student A, who uses accurate, specific evidence in an essay, but she does not use it to prove a consistent argument; versus student B, who creates a brilliant thesis argument, but her evidence is thin. How do you grade these two against one another?

Already I have set up the question in an unfair way. Do not judge them against each other. That is not fair, nor is it a transparent standard. You cannot show the students each other’s essays as a basis for a grade. Not only is it a violation of privacy, it is a standard that did not exist when the original essay was being drafted. No one wants to be graded on a moving target.

By using a rubric, you will be giving students A and B concrete feedback on how to improve—the most important job of a teacher. You will be giving this feedback without even writing a word of commentary, too. (Though I recommend at least a few comments on every assignment.)

So, what’s the answer to the question: would student A or B score higher? Honestly, it would depend on the whole rubric picture. I cannot say for sure. Sorry. (See my analytical essay rubric, Essay Rubric Hallock Sample , for more information. Feel free to use any part of it you find helpful in your classroom.)

My rubrics do not have a category for effort. I evaluate tangible quality markers, like proofreading or following directions—but how can you really judge effort? On the student’s say-so? There are a lot of kids who work very, very hard, and they will never boast (or whine) about it.

Now, sometimes you meet with a student a lot, and you can see the hard-won improvement. Definitely, compliment the student on their determination, and tell the parents about it in the written comments home.

But if a student understood a task the first time around, should he or she be effectively punished? Or what if he or she worked very hard to develop good skills last year, and it has made their job this year easier? This is not golf; do not handicap them for proficiency.

You are always safe if you grade the work on the page. End of story.

Kids ask for extensions, extra credit, extra points, more, more, more. Know that every advantage you give one student may be a disadvantage to another, so think through each case carefully. Every time a student asks me for something, I mentally prepare myself to say no while they are still speaking. I have said no a lot.

Your school will have procedures that make these decisions more straightforward: automatic extensions due to illness, the maximum number of tests a student can take in a day, and so on. And sometimes life happens—things beyond a kid’s control—and you give the extension because it is the right thing to do. But, before you do, imagine having to explain your choice to another student, one who did not get the extension. If the student who didn’t get the extra time would still agree with the fairness of the extension, then you’re good.

Fair. Consistent. Transparent. That’s the gold standard.

There is one syllabus that I have taught for 12 years, three sections a day. You would think those kids would know it already, right?

No. Every class is new. Every year you have to start from zero. Ze-ro.

All that great teaching you did last year, when you took your kids from barely coherent paragraphs to brilliant analytical essays? When they went from plot summary hell to analytical writing heaven? Well, those kids have gone on to delight another teacher, not you. And you get to go back to explaining that, yes, students really do need to write their answers in complete sentences because this is high school, for goodness sake!

As a teacher, your job is not to get smarter. I mean, you will. It happens. But your job is to make them smarter. That means sometimes you are going to be a little bored by stuff you already know. Suck it up, buttercup.

One of the best ways to make every year different is to let the students imprint their own curiosity, personality, and character on the class. Let them talk, as long as they talk to the group, not their neighbors.

Students ask great questions. Let them struggle with the material a bit. You will clear up their confusion in a minute or two. Let them invest themselves in the question first, and then help them find the answer. (And if you do not know the answer, be honest and say you will get back to them.)

Students also know a surprising amount of stuff from other teachers, books they have read, personal experience, and more. Let them learn from each other.

Activities that require the kids to participate—debates, games, simulations, labs, and more—are wonderful. I like to have my students do occasional seminars, in which I am not allowed to say a word for 30 minutes or more. I listen to them and evaluate how well they use the reading in their arguments and questions. These seminars tend to crystalize around critical issues that we would have never discussed had I merely lectured.

Almost every piece of advice will boil down to this. When training intelligence officers, the CIA says that the best lie is one that is closest to the truth. You are less likely to be exposed this way. Well, kids are a suspicious lot: if you pretend to be something you are not, they will expose you like the KGB spymasters they are.

Moreover, assimilation is not a good exemplar. Most of your kids feel like misfits in one way or another, no matter how much confidence they project. (High school sucks, remember?) Let them see that adults, at least, are allowed to be themselves. Don’t rob them of this hope in the toughest time of their lives.

I am a history geek, and I embrace it. I am also oblivious to a lot of pop culture. The kids don’t care. I reach some kids more than others, but I am not the only teacher in the school. All of us as a team provide the support that the student body as a whole needs.

Binge-watch Netflix on the weekends. Paint. Do jigsaw puzzles. Knit. Play rec league hockey. Form a fantasy football league. Write a book. (Or a whole historical romance series set in the American colonial Philippines. No, wait, I did that.) You need something other than school to keep you human. You will do your job better if you value something other than your job. Sneaky logic, ain’t it?

Did you pay attention? Jack Black in

School of Rock

.

Did you pay attention? Jack Black in

School of Rock

.I hope this post has been useful. I do not know why I am putting it on my romance author blog—but since this is my best platform, here it is. Also, I have noticed that a disproportional number of authors are also teachers. And if you say, “Those who cannot do, teach,” then you probably did not care to read this far to begin with. And I’m sticking my tongue out at you. So there.

August 25, 2017

Where Econ Geeks Go on Tour

Yes, there are economics geeks. Mr. Hallock and I are two of them. As international affairs majors, we were required to study two years of economics: macro, micro, international trade, and international finance. And each of us took a few additional electives. So when we decided to go up Mount Washington on the cog railway this week, it seemed silly not to go to the Omni Mount Washington Resort for a tour. Why? You might know the Omni better as Bretton Woods.

Still nothing? Maybe you know it for its skiing, which I have heard is incredible. But to me Bretton Woods will always mean the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference of 1944, which set up the Bretton Woods System and created the International Monetary Fund and part of the World Bank at the end of World War II.

Forty-four Allied nations came to northern New Hampshire to discuss how to stabilize postwar monetary systems. (It seems a little cocky to plan for your victory a year early, but the D-Day landings had just been a surprising success.) From the hotel tour guide, we learned that the international delegates and their subordinates were instructed not to bring their families. The hotel had just been bought by the US government after being thoroughly run down and maltreated by the founder’s heir. The government had “fixed” everything by painting it all white, even the Tiffany stained glass, but they were not ready to put up thousands of guests.

Yes, the Commonwealth of the Philippines was there, represented by Colonel Andres Soriano, a Spanish-Filipino industrialist who expanded San Miguel beer, founded Philippine Airlines, and served on General MacArthur’s staff during World War II. An interesting bit of trivia: he had been a Spanish citizen until the 1930s, when he officially became Filipino. After the war, he was also granted American citizenship.

Yes, the Commonwealth of the Philippines was there, represented by Colonel Andres Soriano, a Spanish-Filipino industrialist who expanded San Miguel beer, founded Philippine Airlines, and served on General MacArthur’s staff during World War II. An interesting bit of trivia: he had been a Spanish citizen until the 1930s, when he officially became Filipino. After the war, he was also granted American citizenship.Guess what? The delegates brought their families, of course. Of course! So the hotel employees had to sleep in tents and other temporary quarters to make room. There were originally only 230+ rooms in the Mount Washington Hotel because they had all been designed as huge suites, since the wealthy families of the Gilded Age stayed here for the whole season, from Memorial Day to Labor Day. (These were the people who did not have their own “cottages” in Newport, of course.) Between 44 countries’ top delegates, their aides, and all their loved ones, the place was packed to the rafters.

Jen sitting at the table—and in one of the original chairs—of the Gold Room, where the Bretton Woods Agreement was signed.

Jen sitting at the table—and in one of the original chairs—of the Gold Room, where the Bretton Woods Agreement was signed.But back to economics: the delegates agreed to peg the world’s currencies to the dollar, the only currency they considered a strong enough shore of value to hold true in the upcoming tough times. The US agreed to make the dollar convertible to gold at a standard rate of $35 an ounce. If you are looking for the moment when the United States became a global economic superpower, this would be it.

Check out this five dollar bill from 1950. Notice the promise to “pay to the bearer on demand”? Pull a five dollar bill out your pocket, if you have one. It doesn’t say that anymore. Also, the text in the top left corner promises that this bill is “redeemable in lawful money” at the Treasury or Federal Reserve. Um, yeah, not anymore.

Check out this five dollar bill from 1950. Notice the promise to “pay to the bearer on demand”? Pull a five dollar bill out your pocket, if you have one. It doesn’t say that anymore. Also, the text in the top left corner promises that this bill is “redeemable in lawful money” at the Treasury or Federal Reserve. Um, yeah, not anymore.Now, accounting for inflation, that peg price to gold is only about $485 an ounce in 2016 dollars, which is a third of today’s (8/25/17) spot price of $1300 an ounce. The US could not keep the dollar strong enough to hold its own against rising gold prices, especially during the economic crises of the late 60s and early 70s. In 1971 President Nixon announced that the US dollar would no longer be convertible to gold.

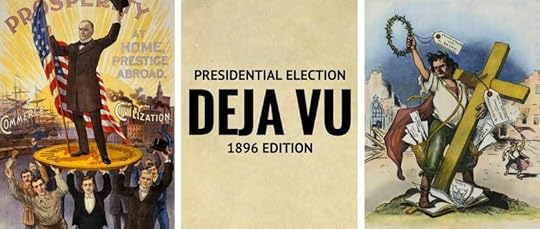

Republican William McKinley (left, from his own campaign poster) and Democrat William Jennings Bryan (right, in a critical Judge magazine cover). Both images found at Wikimedia Commons: McKinley’s poster and Judge‘s cover on “Cross of Gold.”.

Republican William McKinley (left, from his own campaign poster) and Democrat William Jennings Bryan (right, in a critical Judge magazine cover). Both images found at Wikimedia Commons: McKinley’s poster and Judge‘s cover on “Cross of Gold.”.This spelled the end of Bretton Woods and the gold standard. Whether or not you think this is a good thing, it is an interesting conclusion to the gold-bug-versus-silverite debate that dominated the election of 1896. If you were to travel back in time to the Gilded Age and announce this was where we would end up, they would laugh in your face and call you insane. US “greenbacks” are now fiat currency, backed only by the world’s faith in their value, nothing more. (And, well, petroleum, since members of the OPEC cartel agreed that oil would be bought and sold in dollars, starting in 1971. Convenient, eh?)

The monetary conference was not the only interesting part of the Bretton Woods tour. The Cave Grill in the basement used to be a speakeasy! They paid fourteen-year-old boys to keep a look out for cops. Supposedly, if the authorities arrived, you were supposed to throw your whiskey in the barrel, and it would be hidden in the floor. That never happened, apparently, because the cops never came.

Above all, Bretton Woods is a lovely place to lunch, which is exactly what Mr. Hallock and I did on this porch. What a view!

August 22, 2017

The Hallocks Hit Mount Washington

After the loss of our beloved dogs, Jaya and Grover, Mr. Hallock and I decided to get out of the house. We wanted to take a trip that we could never have done while taking care of two geriatric dogs. So what is there to see in New Hampshire? How about the highest peak in the northeastern US, Mount Washington!

Mount Washington as viewed from Bretton Woods, the Omni Mount Washington Hotel. The cog railway is the line going up the left side of the mountain.

Mount Washington as viewed from Bretton Woods, the Omni Mount Washington Hotel. The cog railway is the line going up the left side of the mountain.Now, Mr. H and I are not big hikers. Back in the day, maybe. Now? Up a mountain? No. I won’t even drive up the harrowing Auto Road. (There are no guard rails.) Nope, the Cog Railway is my style. It’s historic, too, built in 1868. This is the way that tourists have visited Mount Washington since the days of President Ulysses S. Grant. They still run two original steam locomotives—one from 1895 and one from 1908—up and down the mountain each day. (The rest are bio-diesel, which the environment appreciates.)

The approaching 1908 steam locomotive, Waumbek, as it descends Mount Washington.

The approaching 1908 steam locomotive, Waumbek, as it descends Mount Washington. The 1908 Waumbek descending the mountain. Notice that the boiler looks tilted. In fact, it is perfectly level, and the rest of the locomotive and passenger car are tilted along the slope of the mountain. The engine is on hinges to keep it operating.

The 1908 Waumbek descending the mountain. Notice that the boiler looks tilted. In fact, it is perfectly level, and the rest of the locomotive and passenger car are tilted along the slope of the mountain. The engine is on hinges to keep it operating.How does it work, you ask? The key is the cog in the middle of the track. The outer two rails do nothing but balance the load, but the train actually clicks up the mountain with a large spoked wheel. The sprockets fit in between the links of the metal chain bolted to the tracks. Smart, isn’t it? It is one of only two mountain-climbing cog railways still in existence.

Close up of the rack-and-pinion mechanism of the cog railway.

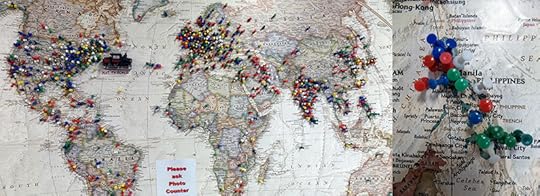

Close up of the rack-and-pinion mechanism of the cog railway.People travel all over the world to visit Mount Washington and ride the cog railway. Yeah, I did not believe that, either, but the push pin map does not lie! The owners of the railway invite guests to place a pin on the map to represent their home—and they start over with an empty map every year. So all the pins you see? New this year. Check out the representation from the Philippines! Impressive.

I should not have been that surprised. Even on the platform, I saw a Philippines flag, so they know where their fans are from.

In case you’re wondering how the workers in the 1860s descended the mountain, check out the cog slide on the right—it’s like an old-fashioned luge. Mr. H and I did not get to slide down the mountain at 60 mph—they’ve changed the mechanism to prevent such adventurism. And, honestly, I was relieved. Am I getting old?

Once we got to the top, we hoped to have a nice venue for eclipse viewing. The Weather Warrior from NBC Boston had the same idea. All of us were out of luck, though. Even though it was the middle of August, it was foggy and 48°F at the peak.

Inside the Tip Top House, it was clear and…still the nineteenth century. If a person did climb Mount Washington back in the day, this was the only place to stay. And, trust me, it could not have been that comfortable. The record low at Mount Washington is -50°F, and it is the home of the world record surface wind speed—231 miles per hour! I would have stayed home, thank you very much.

People climb Mount Washington for this extreme weather, especially if they are preparing a trek to the Himalayas. Though the altitude is not world-breaking, this peak is considered the best place to test your clothing and gear for the elements. I was happy to get up there through less blizzard-defying means. And I had the best of company.

August 19, 2017

Philippine-American War in the News

What a week for the Philippine-American War in the news! Last October, I wrote a post entitled, “Why a War You’ve Never Heard of Matters More than Ever.” Back then I argued that the Philippine-American War defined the American century, but now I see that it might be redefining the next century, too. Whose century will this one be? I leave that to you.

The war has gotten a lot of attention this week—or maybe notoriety is a better word. If you need to catch up with (1) how this war started; (2) how it grew to include the Philippines; and (3) how the Americans ruled, check out this page of history posts from the website.

But let’s get to this week, shall we?

Pershing and the Moros:

It started with this tweet:

This old chestnut, again? My job is not politics, but when politics tries to leverage Philippine-American War history, it’s game on! What President Trump is referring to is his (false) claim that General Pershing used bullets dipped in pig’s blood to pacify the Moros of the southern Philippines. Not true. This myth has been debunked many, many times.

First of all, the Moros were not terrorists:

In the first decades of the 20th century, Muslim Filipinos weren’t targeting American cities or kidnapping tourists. They were attacking American soldiers for one simple reason: The United States had invaded and was occupying their home.

— Jonathan M. Katz in the Atlantic

Therefore, Pershing was carrying out imperial policy, not an Islamophobic agenda. (Not that imperialism isn’t problematic, but you have to remember that it was the official policy of the US government after the 1898 Treaty of Paris, when the Americans bought the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam for $20 million and decided to keep them as “insular possessions.”)

The Moros wanted assurances that the Americans would not try to change their culture or religion; Pershing wanted assurances that the Moros would not challenge US rule. This compact was not as easy as it sounds. One of the cultural practices the Moros wanted to defend was slavery. What would you do? The Americans had already quelled resistance in the rest of the islands, so they decided they could not let slavery stand. And they wanted the Moros to pay taxes, of course. This is where Pershing came in, but his attitude was not what Trump suggests.

Pershing (third from left) at Gen. Sumner’s conference with sultans of Bayang and Oato, at Camp Vicars, Mindanao. Photo from the John Joseph Pershing Collection at the Library of Congress.

Pershing (third from left) at Gen. Sumner’s conference with sultans of Bayang and Oato, at Camp Vicars, Mindanao. Photo from the John Joseph Pershing Collection at the Library of Congress.In 1911, Pershing suggested that the Moros use the Qur’an as a guide for their behavior. He even gave a Qur’an as a gift to one of the leaders, documents show. And that’s not all:

[Pershing] studied their language to the point where, he boasted, he could take low-level meetings without an interpreter. In return, Pershing was elected a datu, a position of respect and leadership in Moro society. He was the only U.S. official to be so honored.

— Daniel Immerwahr from Slate

Now, I should be clear: Pershing did use force. A lot of it. Over 500 Moros died at the Battle of Bud Bagsak in 1913. This active siege may have included women and children, which Vic Hurley admitted was the “big problem the Americans faced.” He indicated that this was not Pershing’s preferred way to do battle.

(The more notorious massacre of Moro civilians, the Battle of Bud Dajo, happened during Pershing’s absence from the Philippine campaign, in 1906. You can blame General Leonard Wood for that one. And you can blame General Jacob Smith for the campaign to turn Samar into a “howling wilderness” in 1901-1902. The fact that Smith and Wood’s campaigns were so public—and so publicly criticized—means that Pershing would not have risked the same condemnation willingly. Nor would he have used pig blood bullets.)

Bodies of dead Filipino Muslims killed at the First Battle of Bud Dajo during the Moro Rebellion. Photo from the Library of Congress.

Bodies of dead Filipino Muslims killed at the First Battle of Bud Dajo during the Moro Rebellion. Photo from the Library of Congress.Pershing did mention in his memoir that others buried Moro fighters in graves with pigs to deter them, but it was not a practice he took part in. Besides, this threat only made sense in American minds—anything done against one’s will would not result in punishment, according to the Qur’an.

Finally, force itself was only one-half of the US military’s policy in the Philippines. If “chastisement” was the stick, “attraction” was the carrot: schools, medicine, infrastructure, limited self-governance, and so on. And then there was another piece, something surprising: forgiveness. The men who most dangerously opposed the Americans—men like Malvar (in Batangas) and Lukban (in Samar)—were granted amnesties in exchange for the surrender of their men and weapons.

General Vicente Lukbán, center, who led the revolution on the islands of Samar and Leyte. He is seated with 1st Lt. Alphonse Strebler, 39th Philippine Scouts, and 2nd Lt. Ray Hoover, 35th Philippine Scouts. Image in the public domain from the Library of Congress, scanned by Scott Slaten.

General Vicente Lukbán, center, who led the revolution on the islands of Samar and Leyte. He is seated with 1st Lt. Alphonse Strebler, 39th Philippine Scouts, and 2nd Lt. Ray Hoover, 35th Philippine Scouts. Image in the public domain from the Library of Congress, scanned by Scott Slaten.Another Roosevelt?

There was another misappropriation of Gilded Age history this week: Vice President Pence compared Trump to Teddy Roosevelt. Roosevelt was the one who put 230 million acres of American soil under conservation. He also first signed the Antiquities Act, which “affords the president the authority to designate national monuments—one of the most important mechanisms for conserving wilderness and wildlife habitat,” according to Field & Stream. Trump, on the other hand, directed the Interior Department to consider withdrawing protected status to 27 national monuments in order to make more room for gas and oil production. Not a great likeness there.

President Roosevelt running an American steam-shovel at Culebra Cut, Panama Canal. Photo from the Library of Congress.

President Roosevelt running an American steam-shovel at Culebra Cut, Panama Canal. Photo from the Library of Congress.Pence made his comparison between Trump and Roosevelt while speaking at the opening ceremonies of the new Cocoli Locks at the Panama Canal. This brings up another contrast: Roosevelt oversaw the construction of this massive infrastructure project, but Trump’s promised infrastructure plans are falling apart after his unwillingness to condemn the neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville:

The president’s much vaunted $1tn plan for American infrastructure now lies in ruins. On Thursday, he dropped plans for an advisory council on the issue, following the disbanding of two business advisory councils after an exodus of several chief executives.

There were other ways in which we could compare the two men. Both set out to change the Republican parties that elected them, but Roosevelt’s progressivism ran directly counter to Trump’s proposed tax reform for the wealthy. According to Roosevelt:

A heavy progressive tax upon a very large fortune is in no way such a tax upon thrift or industry as a like would be on a small fortune. No advantage comes either to the country as a whole or to the individuals inheriting the money by permitting the transmission in their entirety of the enormous fortunes which would be affected by such a tax; and as an incident to its function of revenue raising, such a tax would help to preserve a measurable equality of opportunity for the people of the generations growing to manhood.

A Puck illustration by Udo J. Keppler (27 July 1898) and a Scribner’s essay.

A Puck illustration by Udo J. Keppler (27 July 1898) and a Scribner’s essay.Roosevelt also had a bombastic foreign policy like Trump has warmed up to, but remember this: though Roosevelt helped start the Spanish-American War (and ordered Dewey to expand the battle to Manila), he actually fought in it himself. He resigned his post, recruited his own unit (1st Volunteer Cavalry or “Rough Riders”), and shipped out to Cuba. Given how many physical ailments Teddy Roosevelt overcame early in his life, if he’d had “heel spurs,” he would not have told a single person about it.

Conclusion:

I am glad to see attention given to the Philippine-American War and the Gilded Age in general, but none of the claims by Trump or Pence stand up to the test of history.

(Featured Photo: American soldiers of the 20th Kansas in trenches in the Philippines during the insurrection. Note the open baked beans can in the left foreground. Photo from the Library of Congress.)

August 14, 2017

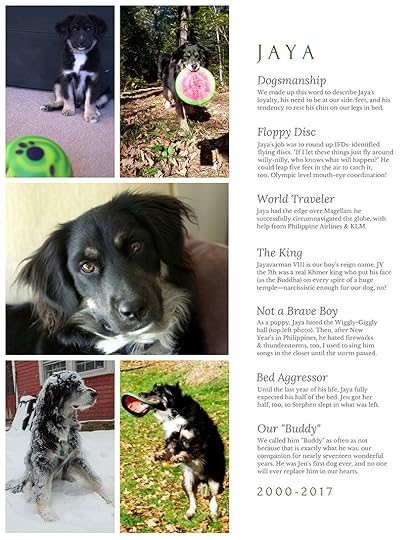

Jaya and Grover: A Writer’s Best Friends

My sabbatical is a story of two spectacular dogs with strange names. It started with sad news when we lost our nearly 15-year-old dog, Grover. She was quite a character. Had she been human, she would have headed up a crime syndicate.

Grover had struggled with back problems for years, occasionally losing control of her hind legs. But she always bounced back—until she didn’t.

Our older dog, Jaya, was the one we had expected to go first—but just to spite his sister he hung on for another whole year. He was by my side through my whole sabbatical, but today it was time to say goodbye. He was almost seventeen years old—approximately 108 in dog years!—but he took a turn for the worse.

We had Jaya for 17 of our 19 years of marriage, and he truly made us a family. Both dogs helped “encourage” our move to the Philippines by getting in a wee tussle with a student in our dorm, but that move led to me writing romance—one of the greatest gifts anyone could have given me.

To quote the Gilded Age cowboy philosopher Will Rogers: “If there are no dogs in heaven, then when I die I want to go where they went.”

August 9, 2017

Sugar Sun series location #10: Fort Santiago

Georgina looked up at Fort Santiago, the stone embodiment of Spanish paranoia that capped the fortress city of old Manila. A bas-relief of Saint James the Moor-Slayer stood guard over the gate. Not the most observant Catholic, Georgie liked the thought of Iberian explorers braving the long, lonely journey across the Pacific only to find themselves back where they started—fighting Muslims. Judging by the number of churches they left behind, conversion had been a spiritual test they had met with gusto.

Saint James the Moorslayer, a close up of the main gate to Fort Santiago. Creative Commons photo by John Tewell.

Saint James the Moorslayer, a close up of the main gate to Fort Santiago. Creative Commons photo by John Tewell.The defensive embankment of Fort Santiago (“Saint James”) has been around since shortly after the Spanish took Manila from its indigenous Muslim rajahs in 1571—hence, the tone-deaf dedication to Saint James the Moorslayer. (The Spanish converted or chased out most Muslims in the archipelago, but not all. Still today, 5% of Filipinos are Muslim, mostly in southern Mindanao and the surrounding islands.)

A bird’s eye view of Manila by Johannes Vingboons, painted in 1665.

A bird’s eye view of Manila by Johannes Vingboons, painted in 1665.When a Dutch traveler painted Manila in 1665, you can already see the walled city of Intramuros, capped by Fort Santiago at the mouth of the Pasig river. That was where the Spanish Army was headquartered. Almost 240 years later, my heroine Georgina Potter had no choice but to search for her missing soldier brother at Fort Santiago because that was where the US Army was headquartered, too. (The relatively brief US stewardship may be the only time this citadel was not a fortress of Catholicism.)

Raising the American flag over Fort Santiago, Manila, on the evening of August 13, 1898. From Harper’s Pictorial History of the War with Spain, Vol. II, published by Harper and Brothers in 1899.

Raising the American flag over Fort Santiago, Manila, on the evening of August 13, 1898. From Harper’s Pictorial History of the War with Spain, Vol. II, published by Harper and Brothers in 1899.Through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Manila grew into a thriving commercial and cosmopolitan center. Every vessel that entered the city—from local casco to Manila galleon—had to sail past the intimidating cannons of Fort Santiago to reach the docks on the north side of the river.

Walls of the old city of Manila. Fort Santiago with gorletas anchored in front of it, 1898. Photo from the Philippine Photographs Digital Archive.

Walls of the old city of Manila. Fort Santiago with gorletas anchored in front of it, 1898. Photo from the Philippine Photographs Digital Archive.Importantly for Filipino history, Fort Santiago is also where national hero José Rizal spent his last days. In his spare time, this polyglot ophthalmologist authored the seminal work of Philippine fiction, Noli Me Tangere (Touch Me Not). The Noli blasts the corruption of the Spanish friars who ruled the countryside and reveals how young, intelligent Filipinos (like Rizal) were denied human and political rights. Since Rizal was executed for writing a work of fiction, the Spanish ironically proved his claims true.

National hero José Rizal was held by the Spanish at Fort Santiago until his execution at the Luneta in 1896, sparking the Philippine Revolution. Images from left to right: a common portrait of Rizal; the statue of Rizal in Fort Santiago, as photographed by Frisno Böstrom; and the entrance to Rizal’s prison, as photographed by Barbara Jane.

National hero José Rizal was held by the Spanish at Fort Santiago until his execution at the Luneta in 1896, sparking the Philippine Revolution. Images from left to right: a common portrait of Rizal; the statue of Rizal in Fort Santiago, as photographed by Frisno Böstrom; and the entrance to Rizal’s prison, as photographed by Barbara Jane.Rizal may have had revolutionary sentiments—how revolutionary is hotly debated—but his fate was ultimately sealed by priests, not politicians. Of course, these friars thought they were the government of the Philippines, so a challenge to them was a challenge to Spanish rule. Where did the friars put him? In their fortress of Saint James, of course. Rizal wrote these last words in his jailhouse poem, later named Mi Ultimo Adios:

My idolized Country, for whom I most gravely pine,

Dear Philippines, to my last goodbye, oh, harken

There I leave all: my parents, loves of mine,

I’ll go where there are no slaves, tyrants or hangmen

Where faith does not kill and where God alone does reign.

Jose Rizal wrote his farewell letter, Mi Ultimo Adios, while being held in a prison cell in Fort Santiago. Now the cell has been converted as the Rizal Shrine where a life-size diorama of his last hours is depicted before his execution. Creative Commons photo by Christian Sangoyo.

Jose Rizal wrote his farewell letter, Mi Ultimo Adios, while being held in a prison cell in Fort Santiago. Now the cell has been converted as the Rizal Shrine where a life-size diorama of his last hours is depicted before his execution. Creative Commons photo by Christian Sangoyo.Scratch a stone in Manila and you’ll dig up all kinds of interesting history, right? By the way, the Creative Commons image at the top of this post is by Fechi Fajardo. If you’re wondering what that net is, it’s a practice driving range for the Intramuros golf course! Oh, what would Rizal think?

August 4, 2017

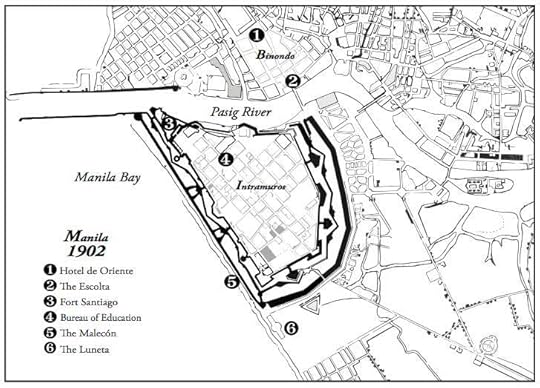

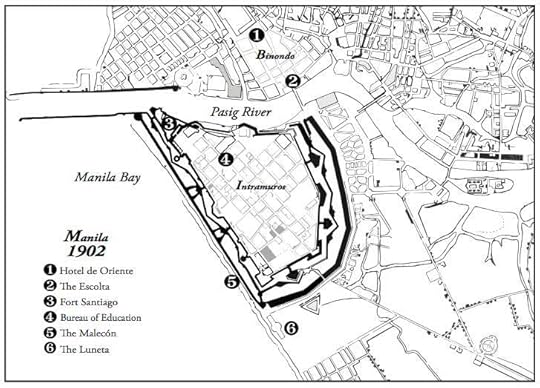

Sugar Sun series location #9: Intramuros

In the opening chapter of Hotel Oriente, heroine Della Berget describes Manila’s Intramuros as “an old Spanish walled enclave in the style of Gibraltar, plunked down in the middle of the tropics.”

And, in fact, that is exactly what the city’s name means: inside the walls that the Spanish built (and rebuilt and rebuilt) to protect them from those who lived outside, the Filipinos and the Chinese. Capping off the walled city was the armed citadel of Fort Santiago:

And, in fact, that is exactly what the city’s name means: inside the walls that the Spanish built (and rebuilt and rebuilt) to protect them from those who lived outside, the Filipinos and the Chinese. Capping off the walled city was the armed citadel of Fort Santiago:

The Spanish did leave their walls on occasion. They had to if they wanted to do anything commercial. They shopped extramuros in Binondo, Manila’s Chinatown, which was within a cannon’s shot of Fort Santiago in Intramuros. The range was very intentional, by the way. The Spanish had a love-hate relationship with their Chinese immigrant neighbors, who, in many cases, had been in Manila longer than they had. Sometimes the “hate” end of things meant firing volleys. The love-hate relationship also played out in shopping, especially on a street called the Escolta. The Spanish claimed the Escolta exclusively for European merchants, but some of those merchants were supplied by Chinese in the neighboring streets. After a full day of shopping in Escolta and a lovely evening on the Luneta, the Spanish would retreat within their walls to sleep.

What was inside the walls? Della calls it a “Catholic wonderland”: “If she glanced up, the city was all domes, crosses, and oyster shell windows.” And no wonder: there were seven churches in Intramuros before World War II. Seven churches—grand ones, too—in a space of a mere 1/4 square mile (166 acres). It should be no surprise to you, then, if I point out that it was really the Catholic Church, via the regular orders of friars, who controlled the Philippines. This was a Crown colony in name only. The real administrators? The Dominicans, the Franciscans, the Recollects, the Augustinians, the Vincentians, the Jesuits, and more. And Intramuros was the seat of their power, where the Manila Cathedral towered over the secular offices of the governor and loomed over the general’s desk in Fort Santiago.

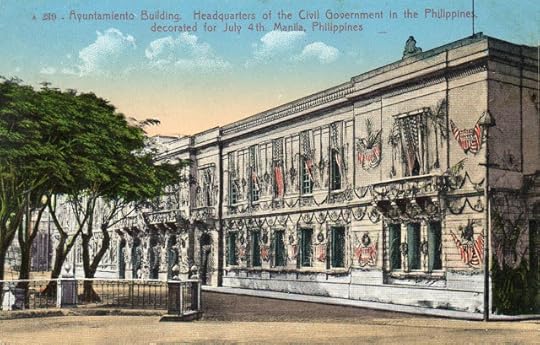

The Ayuntamiento (City Hall, or “Palace” as the Americans misleadingly called it) was the headquarters of the civil government of the American Philippines.

The Ayuntamiento (City Hall, or “Palace” as the Americans misleadingly called it) was the headquarters of the civil government of the American Philippines.When the Americans came, they used the necessary parts of Intramuros, especially Fort Santiago and the city hall (which they confusingly mislabeled the Palace, even though the governor’s—and now president’s—residence is not inside the walls).

The Puerta de Santa Lucia Gate into Intramuros, Manila, Philippines, 1899. You can see the clogged moat was a health hazard. Photo republished by John Tewell.

The Puerta de Santa Lucia Gate into Intramuros, Manila, Philippines, 1899. You can see the clogged moat was a health hazard. Photo republished by John Tewell.Actually, the Americans preferred a fresh sea breeze to the cloistered staleness of Intramuros, and they began to build up the areas south of the Luneta, including Malate and Ermita (where the US embassy compound still sits). And, in their port expansion, they would create a whole “New Luneta” in what had previously been the Bay, and this is where they would build new social establishments, including the Manila Hotel and the Army and Navy Club. After this, many Americans had few reasons to enter Intramuros at all. Too bad.

Nor did the Americans like the medieval air (really, stench) of the moat surrounding Intramuros. In classic American form, they turned it into a golf course.

Intramuros Golf Club photo used under Creative Commons license by Marc Gerard Del Rosario. You can see that water still exists, but as manicured ponds to trap your golf balls.Yes, this hardly sounds very populist, but the colonial administration was not inclusive—and, to be fair, the short but challenging par-66 18-hole course is now owned by the government and can be played by anyone for around $20 (residents) or $30 (tourists).

This original US Army Signal Corps photograph is in the personal collection of John Tewell. Notice San Agustin Church on the top right hand corner, the only of Intramuros’s seven churches to survive somewhat intact due to the red cross on the roof. This and the Manila Cathedral are the only two (of the original seven) to remain operating Catholic churches to the present day.

This original US Army Signal Corps photograph is in the personal collection of John Tewell. Notice San Agustin Church on the top right hand corner, the only of Intramuros’s seven churches to survive somewhat intact due to the red cross on the roof. This and the Manila Cathedral are the only two (of the original seven) to remain operating Catholic churches to the present day.Intramuros suffered most at the end of World War II, when it was the site of the last stand between the occupying Japanese and liberating American forces. The Japanese unleashed a reign of terror on the occupants of Intramuros and Manila at large, known as the Rape of Manila. The Americans, seeking to force a surrender, bombed the city into oblivion, including 6 of the 7 churches in Intramuros. Intramuros was such a disaster that it was ignored during the post-war rebuilding phase and has only recently started to see a renaissance of cultural, social, and commercial activities. If you are in Manila, take a tour with performance artist Carlos Celdran, and he will make you see Intramuros in a whole new light.

The Transitio commemoration with Carlos Celdran: burning prayers on the walls of Intramuros (left) and the arts festival on the grounds (right).

The Transitio commemoration with Carlos Celdran: burning prayers on the walls of Intramuros (left) and the arts festival on the grounds (right).

July 29, 2017

The Weare Area Writers Group

One of the highlights of my sabbatical has been joining the Weare Area Writers Group. The gang meets twice a month on a Friday morning at the Weare Public Library. We workshop our writing and pool our knowledge about the changing world of publishing. This group came about because of the efforts of one woman—our organizer extraordinaire and our biggest cheerleader, Sharon Czarnecki.

Sharon Czarnecki, founder of WAWG, and me at the Dunbarton Arts on the Common this past May.

Sharon Czarnecki, founder of WAWG, and me at the Dunbarton Arts on the Common this past May.What the above description does not capture is how much fun we have together. Members of the group share very personal memories—in every format from poetry to prose—which has allowed us to move right on past superficial friendship into something deeper and more meaningful. I cannot believe that I have only known this group a year. It feels like we have been friends for ages. Since I am a relatively new transplant to Weare, New Hampshire, their support has been especially important.

From left to right: authors Marjorie Burke, Ellen H. Reed, and me (Jennifer Hallock). Impressive table, no?

From left to right: authors Marjorie Burke, Ellen H. Reed, and me (Jennifer Hallock). Impressive table, no?There is a social component to what we do, too. So far four of our members are published, in genres ranging from memoir to time travel mystery to historical fiction to my own steamy historical romance series. One of our favorite things to do is to take our show on the road by selling books at craft and book fairs in the area. Our next date on the calendar is Weare Old Home Day on August 26th. Come see us, check out our books, and ask about the group.

Here’s a little about the other published authors and what they will be selling:

Connie and I joined WAWG the very same day, and a year later I was in the room when Connie pressed “publish” at Amazon! It was so exciting. I have no doubt this will be a bestseller at Old Home Day.

The book I have shared with the WAWG folks is the upcoming Sugar Moon, small excerpts of which you can read here. But while I’ve been a part of WAWG, I did publish a new novella in the Sugar Sun series, Tempting Hymn:

These books and more will all be ready for purchase and signing at Old Home Day. We hope to see you there!

July 25, 2017

Screw upon a Screw: Sex Education in the Gilded Age

When I started writing historical romance set in the Gilded Age, I needed to know what level of sexual ignorance I was dealing with.

Did doctors of the day believe in “virginity tests”?

Did they understand a woman’s body and how to bring it pleasure?

Did they think that sex should be pleasurable for women in the first place?

Finally, how did they feel about masturbation, or self-pleasure?

In my unscientific, random sampling of (cishet) primary sources, the Gilded Age scored 2.5 out of 4, which was a little better than I anticipated. Let’s investigate:

“Virginity tests”:

The hymen does not start whole—a perforation is needed to allow menstrual fluid to escape, after all—but a woman can easily tear and rub away the rest through an active lifestyle. Horseback riding, yes. Sneezing? Eh, probably not. But it was nice that Dr. Foote erred in her favor. It is also nice that he acknowledged that the hymen test was “cruel and unusual.”

However, it is depressing to also note that, due to “popular prejudice,” even the best physicians concealed the whole hymen truth. This led some fearful young women to try to “tighten” their vagina with alum, something I found discussed in a magazine of 1880 erotica (written by and for men). The alum suggestion wasn’t new—women had been encouraged to try this since medieval times—but it didn’t work then, and it still doesn’t. It just dries you out. There is no virginity test other than asking a person.

a woman’s body:

This may be the Gilded Age quote that surprised me the most. I had thought for sure that today’s popular culture would be more knowledgeable than 150 years ago, especially regarding the clitoris, but no! In fact, did you know that even in the eighteenth century, the most widely printed medical book in Europe and America informed men about the clitoris? Yay, cliteracy!

A complete drawing from the 5th edition (1914) of Human Anatomy: A Complete Systematic Treatise by Henry Morris. This textbook, first published in 1893, was used by the American teachers in the Philippines in the early 1900s.

A complete drawing from the 5th edition (1914) of Human Anatomy: A Complete Systematic Treatise by Henry Morris. This textbook, first published in 1893, was used by the American teachers in the Philippines in the early 1900s.Fortunately, my heroine Allegra will have a Gilded Age anatomy book (the one above) to guide her explorations. Every virgin should have one! Her hero, Ben, will appreciate her sharing her new knowledge with him, too. This is why I love writing romance, a genre that prioritizes the needs, strengths, and happiness of women. Real romance doesn’t ignore the clitoris! I’m going to cross-stitch that on a pillow someday.

A woman’s pleasure:

Pleasure and procreation may coincide, but one is not required for the other—for women. Herein lies a problem with how we teach (or don’t teach) women about their bodies. Even today, students may be taught reproductive biology, but that curriculum illustrates a prudish bias: a woman’s anatomy is described like plumbing, with pipes only used for pumping out children. In this narrative, only the male’s sexual pleasure is required for procreation, leaving the impression that men are the only ones who experience desire (or who should experience it).1

How sex-positive were Gilded Age experts? Did they think women should receive pleasure from the act? Dr. Foote, author of the above quote about the clitoris, believed that all aspects of sexual interaction—from friendly conversation to full, pleasurable intercourse—were absolutely necessary for good health: “I place sexual starvation among the principal causes of derangements of the nervous and vascular systems,” he said.

Now let’s check in with a woman, “sexual outlaw” Ida Craddock, who was sent to jail for sending “obscene” sexual education materials through the mail (to subscribers).2 Craddock’s description of a woman taking an active part in intercourse, even to the point of describing specific motions, is refreshing. She also claims that these motions will improve a woman’s sexual passion, which is encouraging. But—and this is a big BUT—Craddock believes the woman’s passion is irrelevant. A fortunate by-product, yes, but unnecessary. Bummer.

In fact, Craddock believed so strongly that sex was for procreation that her vision of contraception was coitus without orgasm—for both partners—for the entire duration of pregnancy and two years following. She thought this sexual brinksmanship would make both partners stronger. Three years of deliberate sexual arousal without release? No wonder Anthony Comstock, self-appointed male protector of American postal virtue, had her thrown her in jail.3

Overall, I’ll give the Gilded Age half a point here, and that’s being generous.

self-pleasure:

Your own pleasure starts with you:

Rosa did not have a lot of experience—none very good, at least—but neither did Jonas, it seemed. And Rosa knew something he did not. She knew what she liked.

“Look,” she said. She parted her lower lips to reveal the ridge that gave her the most pleasure when she was alone.

Or was this too much? To admit such a dirty secret, especially to a man—had she not learned her lesson? When she had tried to show Archie, he had lectured her about sin and a woman’s shame. Now she risked her husband’s disapproval, too.

Jonas looked up. “Show me what you want,” he said.

If Rosa could do it, so could anyone in the Gilded Age, right? Well, maybe not. Masturbation has long been considered a sin in the Judeo-Christian tradition, ever since Onan spilled his seed on the ground (rather than give his brother’s widow an heir) and God smote him (Genesis 38:9-10). In many traditional sources, the act is called Onanism. Thus, we are back to the idea that sex is only for procreation, a mission that made sense for the small, struggling band of Hebrews trying to survive the rough-and-tumble world of the ancient Near East.

A more recent concern by the Catholic Church about masturbation is the idea that it draws away from the sexual relationship—a withholding of yourself from what should be the most intimate aspect of marriage. It is considered “radically self-centered.” While, yes, an addiction to masturbation may be unhealthy, the knowledge of one’s own body cannot help but lead to a better shared experience. A shocking idea, I know.

And it was shocking in the Gilded Age. Edwardian prophets took the above warnings and turned them into near paranoia. The same level-headed, seemingly enlightened Dr. Foote who criticized the hymen test, described the importance of the clitoris, and said sex was healthy—well, he had only dire warnings about masturbation in 1887: “Many a promising young man has lost his mind and wrecked his hopes by self-induced pleasures.” Another author agreed: “That solitary vice is one of the most common causes of insanity, is a fact too well established to need demonstration here.” (That logic is convenient: it’s so true that I don’t need to prove it. Hmm…)

Dr. Jeffries (1985) listed more terrible symptoms of this vice: a slimy discharge from the urethra, a “wasting away” of the testicles, ringing in the ears, heat flashes, large spots under the eyes, nervous headache, giddiness, solitariness, gloominess, and the inability to look the doctor in the eye. Others added cancer (!), acne (yep, that old hogwash), and a craving for salt, pepper, spices, cinnamon, cloves, vinegar, mustard, and horseradish. That last one is a head-scratcher. So if you wanted to eat anything with flavor at all, that was a giveaway? I’m in trouble.

Dr. Jeffries’s unexplained (and unverified) diagram of what happens to semen after masturbation. Are you wondering how he obtained the first sample without masturbation? Me, too.

Dr. Jeffries’s unexplained (and unverified) diagram of what happens to semen after masturbation. Are you wondering how he obtained the first sample without masturbation? Me, too.Speaking of food, did you know that Corn Flakes were invented in 1898 to keep you from masturbating? For real.4

The John Harvey Kellogg quoted above is the Kellogg of breakfast cereal fame. His obsession with sexual purity was so extreme that he never consummated his own marriage. He and his wife slept in separate bedrooms and adopted their children. By the way, who did Kellogg believe were the worst masturbatory offenders? Foreigners, of course. Russians especially.

The John Harvey Kellogg quoted above is the Kellogg of breakfast cereal fame. His obsession with sexual purity was so extreme that he never consummated his own marriage. He and his wife slept in separate bedrooms and adopted their children. By the way, who did Kellogg believe were the worst masturbatory offenders? Foreigners, of course. Russians especially.

The cure? Clean living, of course! Rising early in the morning, eating the recommended bland breakfast, abstaining from smoke and drink, keeping busy, avoiding solitude, and circumcision. This is why the procedure became routine in American hospitals in the twentieth century and still predominates today. It is not good medicine but good morals. Or so they said.

There is still a bit of taboo in talking about masturbation today—well, maybe more than a bit. In 1994 President Bill Clinton forced his Surgeon General Joycelyn Elders to resign because she said that masturbation should be taught in schools as a preventative for teenage pregnancy and sexually-transmitted diseases. Still, I think we are a far cry from saying it causes cancer. And we’ve sweetened breakfast cereals beyond recognition, so there, John Harvey Kellogg! More and more parents are questioning routine circumcision for non-religious reasons, though the procedure has traction because it is what people in the US are used to.

All this brings me to an interesting realization: if you asked me which parts of my books would have most shocked real Gilded Age readers, it would have been the openness most of my characters have toward masturbation. And, guess what? I’m not going to stop writing it, historical accuracy be damned. Long live romance!

(Featured photograph is a close up of a Fallopian tube and ovarian ligaments in Henry Morris’s Human Anatomy: A Complete Systematic Treatise by English and American Authors, 5th edition, 1914, p. 1270.)

Footnotes:

1. What follows is a whole domino chain of bad decisions, including a teenage “hook up” culture that emphasizes sexual trophy hunting (most often by boys), rather than two people finding mutual pleasure in a mature relationship built on respect and trust.↩

2. The law against this distribution of “obscene” materials, the Comstock Law, is still on the books in a modified form. It no longer covers sexual education or contraception, the latter of which became a legally protected right—to married couples, originally—under the 1965 Supreme Court decision Griswold v Connecticut, also known as the Birth Control Revolution. Good thing, too, because this post would have gotten me jailed.↩

3. And she was not the only sexual rights crusader to have disturbing ideas. Marie Stopes believed in eugenics and forcible sterilization for those “unfit” to carry on their genes. She even “disinherit[ed] her son when he married a woman who had poor eyesight.” Yikes. And Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger dabbled in eugenics, too, by the way. We need to question everything from this period because racism, classism, and ableism were pervasive.↩

4. The original purity food was the graham cracker, which was nothing like your s’mores building block of today. It was made of unrefined flour with no sugars or spices—deliberately bland. Because that contained sexual desire, didn’t you know?↩

July 18, 2017

Sugar Sun extras: A complete list

When I was writing Under the Sugar Sun, I imagined annotating it with all sorts of fake documents: telegrams, ledgers, even Javier’s high school report card from Seminario-Colegio de San Carlos! Yep. Apparently, I thought that needed to happen.

I was looking through these documents the other day, bemoaning how much time I wasted making them, and then realized: I have a website. Junk is what the web is for, right? So, here you go: Sugar Sun extras! Enjoy.

Sugar Sun Series Extras

- Jennifer Hallock's profile

- 38 followers