Jennifer Hallock's Blog: Sugar Sun Series Extras, page 18

February 22, 2017

The Hymns of Tempting Hymn

Tempting Hymn is about two people of faith—different faiths, actually, which is one of many obstacles the characters must overcome. Jonas is an American Presbyterian missionary, and Rosa is a Filipina Catholic nurse. The book has spiritual elements, but it is not an inspirational romance. (In other words, there is explicit sex. Yay!)

No matter if you are a religious person or not, good music is good music—and that includes hymns. At the school where I teach, we have all-school chapels four mornings a week. The prayers are interfaith and the talks secular, but we sing from the Episcopalian 1982 Hymnal at the end of every service. After a while, a person gets to have favorites. She might even recognize hymns by number.

It was during Lessons & Carols—which is a Christmas-time chapel on steroids—that the idea for Jonas and Rosa’s story came to me. I still have the program I ruined with all my scribbles. When ideas come, you do not wait two hours to go home and write them down. No, you borrow a pen and write furiously throughout the entire concert. Was that a little rude? Yes. But, in my defense, I think the choir would have really appreciated how much their singing moved me. When I finished the book, I knew what the epilogue scene had to be: my favorite solo that opens Lessons & Carols, sung in my imagination by Rosa.

I chose the other hymns in the book based upon their beauty and meaning. I had to be historically accurate, of course, so I worked from the 1895 revision of The Hymnal, approved by the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. Most of the hymns below can be found by the identifying number given.

Photo of a church’s hymn board by Charles Clegg.

Photo of a church’s hymn board by Charles Clegg.Prologue: “Amazing Grace.” This is one of the few not included in the hymnal mentioned above. Though this early 19th century song was included in earlier Presbyterian versions—for example, it was hymn number 519 in the 1874 Hymnal—they omitted it in 1895 for reasons I cannot fathom. But I still used the song. Jonas would have certainly learned this song from older versions, and he would have sung it often for his daughter, Grace. Now the song is the single most frequently sung hymn in the Presbyterian Church USA, with more than sixty-six percent of their congregations singing it twice or more per year. For your listening pleasure, I chose Elvis Presley’s version (below) so that I could showcase a male voice. (And, if you want to hear the bass of the tune as a solo, listen to this version by Acappella with Tim Faust.)

Chapter Two: Number 589, “Come, Thou Fount of Every Blessing.” The reader may not recognize the middle verses I used in this scene, but they will likely recognize the title of the song. Everyone from Mumford & Sons to the Christian punk band Eleventyseven has covered it. Sufjan Stevens has a wonderful version in his Complete Christmas Collection, but that video was removed from YouTube. Instead, I found this version by Sarah Noëlle, which is lovely:

Chapter Three: Number 524, “Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah.” I fudged the history here just a bit. The 18th century words for this song are correct, but do not try to sing the notes printed there. This hymn really did not catch on until the tune Cwm Rhondda was written, a year after my character Jonas sings it in the book. I hope you will forgive the anachronism. As befits a Welsh tune by a Welsh composer, the version I have chosen to post here is sung by the Tabernacle Welsh Baptist Church, Cardiff:

Chapter Five: Number 98, “The Spacious Firmament on High.” This is, without doubt, my favorite hymn—and yet it seems to be the least popular to cover. The reason I love it may be the same reason most choirs do not: it is very deist in theology, with a vague “supreme architect” Creator fashioning the universe of planets, stars, and orbs. Moreover, the hymn is by Hadyn. It’s gorgeous! I chose an a cappella version (by a group named Acappella) because it allows you to hear the bass clearly, though the beat is a little fast:

Chapter Seven: “Adoro Te Devote.” Since this is a Catholic hymn, you will not find it in the Presbyterian hymnal. The mass described in this chapter was a Tridentine Mass (pre-1962 Second Vatican Council), which means it would have been all in Latin, and the hymns would have been Gregorian. Have you listened to Gregorian music? Beautiful, but not catchy. And Latin. Did I mention the Latin? Of the various hymns I listened to, this one has the most identifiable melody, probably because the music was not written until after the seventeenth century. Therefore, it was the best choice for Jonas to sing on the fly:

Chapter Eight: Number 24, “Abide with Me.” I used this song as both a hymn to be sung by Jonas while he fixes the mill, and also, later, as a chapter title. It is the kind of hymn that I think a man with a natural bass would enjoy singing because it stays within his range. The lyrics also tell the story of the big decision he is about to make. The version below is sung by George Beverly Shea:

Chapter Twelve: Number 304, “The Church’s One Foundation.” In the story, I make a point of the different directions the bass and sopranos go in this song—opposite, but complimentary. To hear the bass part only, listen to this great tutorial by BassHymn:

To hear all the parts together, I have chosen a video by King’s College Cambridge:

Chapter Twelve (again): Number 692, “Now the Day is Over.” I found this hymn in the Children’s Services section of the hymnal, and it fits perfectly as a lullaby. This version is by Pat Boone:

Chapter Nineteen: Number 276, “Gracious Spirit, Holy Ghost.” I chose this hymn because of its paraphrasing of the Apostle Paul’s I Corinthians 13. You know the passage I’m talking about:

Love is patient; love is kind; love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice in wrongdoing, but rejoices in the truth. It bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things….And now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; and the greatest of these is love.

I wanted this sentiment in hymn form, which is surprisingly hard to find. Here, at least, is the common tune used for the hymn:

Epilogue: Number 696, “Once in Royal David’s City.” Sitting through this service in December 2013 gave me the seeds of Rosa and Jonas’s story, so I end the book (and this post) with the real deal. No substitutions. In this, the 2015 Groton School Lessons & Carols service, the soprano solo is sung by Phoebe Fry, Form of 2017 (and Barnard College class of 2021). She is a talented singer-songwriter in the folk-pop tradition, so please check out her amazing songs. (The orchestra prelude is wonderful, but you can skip right to the hymn at minute 12:15.) Enjoy!

Thanks for listening, and I hope you enjoy Rosa and Jonas’s story. It is about finding a home for love.

February 10, 2017

Where to Find Me in the Philippines

I’m leaving in two days for the Philippines!…snowstorm permitting. Then, again, it’s New England. We’re used to this crap. We have four seasons up here: winter, more winter, mud season, and construction.

Dunkin Donuts meme courtesy of Massachusetts Memes.

Dunkin Donuts meme courtesy of Massachusetts Memes.For those of you who are under the sugar sun in the Philippines (see what I did there?), I can’t wait to see you! Where? I’m glad you asked. I have two public events planned:

First, I will be on the steamy romance panel of Romance Writers of the Philippines RomCon at Alabang Town Center on February 19th! Starting at 3pm, Bianca Mori, Georgette Gonzales, Mina V. Esguerra, and I will be talking about our deliciously naughty novels. We will answer all your questions—ALL of them. If you’re too shy to ask something, find me afterwards. I’ve taught health and human sexuality to teenagers for almost 20 years. It is very hard to embarrass me.

Second, I will be giving a talk called History Ever After at the Ayala Museum on February 24th at 2pm. It’s sort of a mix of history and fiction. Don’t worry—I’ll tell you which is which…most of the time. I will also be talking about my latest novella in the Sugar Sun series, Tempting Hymn, which releases that very day! Real events write the best fiction, don’t you think? Mina will be there, as well, encouraging you to ask me the tough questions. (See disclaimer above. Bring ’em on!)

Thanks to Mina V. Esguerra of #romanceclass, Liana Smith Bautista of Will Read for Feels and Romance Writers of the Philippines, and Marjorie De Asis-Villaflores of the Ayala Museum for all their help in planning and producing these events. I am indebted to you all!

February 3, 2017

More about History Ever After at the Ayala Museum (24 February 2017)

“Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn’t.”

Mark Twain said that. He’s one of my favorite authors and personalities in the American canon. Did you also know he was one of the leaders of the anti-imperialism movement, and that he argued for giving the Philippines its freedom in the early twentieth century? Interested?

If you live in Manila, I hope you can come to the Ayala Museum on February 24th, from 2-5pm, to hear my talk “History Ever After.” What will I talk about? Good question. I will start with truth and weave in the fiction, and I think Mark Twain would be proud:

I will prove that our news is not new. In fact, America’s current debates over global economic integration, nation-building, immigration, and the use of military force echo the real and vigorous debate that started with the conquest of the Philippines.

I will show how this history helps me develop my unusual, precocious, and maybe even dangerous heroes and heroines. I will talk about each, too, including the main characters of my new novella, Tempting Hymn. Real history writes the best fiction in any genre.

Finally, I will address one of the most difficult questions in historical romance: how do you write happily ever after when your audience knows the next war is just around the corner? In other words, how do you walk the line between romancing history and romanticizing it?

Maybe you want to know about the shared history of Filipinos and Americans, or maybe you want to hear the latest updates in the Sugar Sun series. Or maybe you’re a writer, and you want to know how to shape conflict and character development with real history. If any of these three are true, there’s something for you here!

Tickets and more information at the Ayala Museum website.

January 27, 2017

“History Ever After” at the Ayala Museum

Real history writes the best fiction in any genre. The unusual, precocious, and even dangerous heroes and heroines of real life are the ones who inspire us to start typing. But how do you write happily ever after when your audience knows the next war is just around the corner? How do you walk the line between romancing history and romanticizing it?

As historian and author Camille Hadley Jones posted on Facebook: “I’m finding [writing] difficult because I don’t want to ‘escape’ into the past, I want to confront it—with a HEA of course—yet I know that’s not what’s many readers seek from [historical romance].” Maybe not, but I am right there with her on “confronting history.” That is why I write my books set in the American colonial Philippines. It is why I put Javier and Georgie in the midst of the 1902 cholera epidemic in chapter one of Under the Sugar Sun.

Advice often given to authors is: “Don’t underestimate your reader.” Don’t gloss over the inconvenient, gritty truth just because you think your readers cannot handle it. Use it to create real characters and real conflict—but make sure that no matter how dark the dark moment, love will overcome all.

This is the subject of my talk “History Ever After” at the Ayala Museum, Makati City, on February 24, 2017, from 2-5pm. With the help of Mina V. Esguerra of #romanceclass, I will answer questions about how I balance courtship and calamity in my Sugar Sun romance series, set in the Philippine-American War. Hope to see you there!

January 20, 2017

Raise the Red Flag: Cholera in Colonial Manila

My upcoming novella Tempting Hymn will be the second in my series to mention the 1902 cholera epidemic in the Philippines. The book’s hero, Jonas Vanderburg, volunteered his family for mission work in the Philippines, only to lose his wife and daughters in the same outbreak that Georgina Potter dodged when she arrived in Manila in Under the Sugar Sun. Do I just need a new idea? I would argue that I’m writing about what people feared most in the Edwardian era. Before the mechanical death of the Great War, disease was the worst of the bogeymen.

In the movie in my head of Tempting Hymn, Mercedes Cabral plays Rosa, and Daniel Craig plays Jonas. Cholera is an important part of the backstory to this novella.

In the movie in my head of Tempting Hymn, Mercedes Cabral plays Rosa, and Daniel Craig plays Jonas. Cholera is an important part of the backstory to this novella.My books may be historical romance, but this post will not romanticize the history. Census figures put the total death toll from Asiatic cholera in the Philippines (1902-1904) between 100,000 and 200,000 people. Even that number might be low. This strain of the disease was particularly virulent, killing 80 to 90 percent in the hospitals. The disease progressed rapidly and painfully:

Often the disease appears to start suddenly in the night with a violent diarrhea, the matter discharged being whey-like, ‘rice-water’ stools…Copious vomiting follows, accompanied by severe pain in the pit of the stomach, and agonizing cramps of the feet, legs, and abdominal muscles. The loss of liquid is so great that the blood thickens, the body becomes cold and blue or purple in color…Death often occurs in less than a day, and the disease may prove fatal in less than two hours. (A.V.H. Hartendorp, editor of Philippine Magazine)

The Yanks saw cholera as a personal challenge to their colonial ideology. They had come to the Philippines to “Fill full the mouth of famine and bid the sickness cease,” in the words of Rudyard Kipling. What was the point of bringing the “blessings of good and stable government upon the people of the Philippine Islands” if they could not prove the value of their civilization with some “modern” medicine?

Cholera was not a new killer in the islands, nor did the Americans bring the disease with them. Though the Eighth and Ninth Infantries were initially blamed, the epidemic had its roots in China. As Ken de Bevoise said in his outstanding work, Agents of Apocalypse: “The volume of traffic…between Hong Kong and Manila in 1902 was so high that it is pointless to try to pinpoint the exact source.” However, just because Americans did not bring cholera does not mean that they are off the hook.

Amoeba with cholera vibrio and leprosy bacillus, as pictured in the Twelfth Annual Report of the Bureau of Science in Manila, courtesy of the Internet Archive.

Amoeba with cholera vibrio and leprosy bacillus, as pictured in the Twelfth Annual Report of the Bureau of Science in Manila, courtesy of the Internet Archive.War weakens and disperses a population, leaving it more vulnerable to disease. And the way the war was fought south of Manila in 1902 was particularly brutal. General J. Frederick Bell had set up “protection zones” where all civilians were forced to live in close quarters without access to their homes, farms, and wells. Once cholera hit these zones, there was no escape. 11,000 people died while being “protected” from anti-American forces. Even worse, mass starvation forced the general public to ignore the food quarantine, meant to keep tainted vegetables from being sold on the market. The Americans blamed Chinese cabbages for bringing cholera spirilla to the Philippines to begin with, but then gave the people no other choice but to eat (possibly contaminated) contraband to survive.

Inside Manila itself people were also quarantined—not a terrible idea on the face of it. The traditional Filipino home quarantine had worked well in the past: infected homes were marked with a red flag to signal people to stay away while loved ones were cared for. But the Americans thought bigger. They “collected” the infected and brought them to centralized hospitals outside of the city. Hospitals…detention camps…who’s to say? According to De Bevoise, eighty percent of the time, when the patient was dragged out of their home and carted off to this “hospital,” which suspiciously also housed a morgue and crematorium, that was the last their family saw of them. Despite the Manila Times portraying the Santiago Cholera Hospital as a “little haven of rest, rather than a place to be shunned,” and bragging that it was staffed by the “gentle…indefatigable, ever cheerful” Sisters of Mercy, people knew better. They would do anything to keep their family members from being taken there. They fled. They hid their sick. Because cremation was forbidden for Catholics at this time, the Filipinos hid their dead.

And the disease spread.

Burning of the cholera-stricken lighthouse neighborhood of the Tondo district, Manila, 1902, by the health authorities. Photo courtesy of Arnaldo Dumindin.

Burning of the cholera-stricken lighthouse neighborhood of the Tondo district, Manila, 1902, by the health authorities. Photo courtesy of Arnaldo Dumindin.My book Under the Sugar Sun began with a dramatic house burning scene, where public health officials destroyed an entire neighborhood in the name of sanitation. The road to hell is not just paved with good intentions. It is also littered the corpses of industrious, exuberant, and dogmatic government officials. Any houses found to be infected were burned, “because the nipa hut cannot be properly disinfected,” in the words of one American commissioner’s wife. People were forced to find refuge elsewhere in the city, carrying the disease with them. Because it was such a bad policy, Filipinos thought the American officials must an ulterior motive in the burnings: to drive the poor out of their homes, clear the land, and build their own palaces. The commissioner’s wife, Edith Moses, herself said: “Sometimes, when I think of our rough ways of doing things, I feel an intense pity for these poor people, who are being what we call ‘civilized’ by main force….it seems an act of tyranny worse than that of the Spaniards.”

American instructions to the sick were also confusing—and sometimes bizarre. Clean water was a necessity, but this was not something the poor had access to. Commissioner Dean C. Worcester claimed: “Distilled water was furnished gratis to all who would drink it, stations for its distribution being established through the city, supplemented by large water wagons driven through the streets.” But no other source mentions such bounty. In fact, as author Gilda Cordero-Fernando pointed out in her article, “The War on Germs,” in Filipino Heritage, most people treated distilled water like a magic tonic, it was so rare: “Asked whether a certain family was drinking boiled water, as prescribed, one’s reply was ‘Yes, regularly—one teaspoon, three times a day.’” Even worse, though, was this advice by Major Charles Lynch, Surgeon, U.S. Volunteers, which was reprinted in the Manila Times:

Chlorodyne, or chlorodyne and brandy, have been found especially useful; lead and opium pills, chalk, catechu, dilute sulphuric acid, etc., have all been used. With marked abdominal pain and little diarrhea, morphine should be given…Ice and brandy, or hot coffee, may be given in small quantities, and water, in small sips, may be drunk when they do not appear to increase the vomiting…cocaine and calomel in minute doses—one-third grains—every two hours, having been used with benefit in some cases.

Lead pills. Opium. Morphine. Chalk. Cocaine. And do you know what “calomel” is? Mercurous chloride. If the cholera doesn’t kill you, Dr. Lynch’s treatment will! Though the coffee and brandy sounds nice…

Dr. Moffett’s Teethina Powder claims to cure “cholera-infantum,” which is a form of severe diarrhea and vomiting, with powdered opium. This ad is from Abilene Weekly Reflector, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Dr. Moffett’s Teethina Powder claims to cure “cholera-infantum,” which is a form of severe diarrhea and vomiting, with powdered opium. This ad is from Abilene Weekly Reflector, courtesy of the Library of Congress.When the Americans could not control the spread of the disease with their ridiculous treatments and counterproductive policies, they blamed the epidemic on the victims. As public health historians Roy M. MacLeod and Milton James Lewis wrote:

American cleanliness was being undermined by Philippine filth. The Manila Times lamented the cholera deaths of “clean-lived Americans.” It identified the “native boy” as “the probable means of infection” since in hotels and houses he prepared and served food and drinks to unwitting Americans. The newspaper reminded its American readers that “cholera germs exude with the sweat through the pores of the [Filipino servant’s] skin”and that “his hands may be teeming with the germs.”

Racist Pears’ soap ads of the Edwardian era. Notice that the ad on the left borrows from Kipling’s poem, “The White Man’s Burden,” and equates virtue with cleanliness. The one on the right is even more offensive, equating cleanliness (and virtue) with fair skin.

Racist Pears’ soap ads of the Edwardian era. Notice that the ad on the left borrows from Kipling’s poem, “The White Man’s Burden,” and equates virtue with cleanliness. The one on the right is even more offensive, equating cleanliness (and virtue) with fair skin.Racism figured in every aspect of American rule. According to the Manila Times, the Americans organized their cholera hospitals by race: the tent line marked street A was “Chinatown,” street B was for the Spanish, street C for white Americans, street D for black Americans, and E through G for Filipinos. The Chinese-Filipinos may have come first because they had the lowest death rate of any group, including Americans. A Yankee health official ascribed this to the fact that they “eat only long-cooked and very hot food, in individual bowls and with individual chopsticks, and that they drink only hot tea.”

The epidemic reached its peak in Manila in July 1902, and in the provinces in September 1902, before running its course. Even though its decline was probably due to the heavy rains cleansing the city, increased immunity among the remaining population, and a strategic call by the Archbishop of Manila to encourage Filipinos to bury their dead quickly, the Americans still congratulated themselves on their great efforts. And they had worked hard, it is true: Dr. Franklin A. Meacham, the chief health inspector, and J. L. Judge, superintendent of sanitation in Manila, died from exhaustion. The Commissioner of Public Health, Lt. Col. L. M. Maus, suffered a nervous breakdown. Even the American teachers on summer vacation were encouraged to moonlight as health inspectors—for free, in the end. The wages paid to them by the Police Department were deducted from their vacation salaries because no civil employee was allowed to receive two salaries at once. (The relevant Manila Times article explaining this policy is not online, but its title, “Teachers are Losers” is worth mentioning.)

The hope of a quick end to the cholera outbreak was dashed by July and August 1902, as shown in these three articles from the San Francisco Call, the Akron (Ohio) Daily Democrat, and the Butte (Mont.) Inter Mountain.

The hope of a quick end to the cholera outbreak was dashed by July and August 1902, as shown in these three articles from the San Francisco Call, the Akron (Ohio) Daily Democrat, and the Butte (Mont.) Inter Mountain.All their hard work might have been for nought, though. Filipino policies of quarantine would have probably been more effective, had they been given the chance to work. Whipping up the population into a panic was exactly what the Americans should not have done. In the name of containing the disease, they caused the real carriers—people—to disperse wider and faster throughout the country. The Yanks thought they knew better, but instead they made things worse. Americans today need to be on guard against such hubris, which is why I write my love stories in the middle of strange settings like cholera fires and open insurrections. Come for the sexy times, stay for the political messages. Enjoy!

Featured image is of the cholera squad hired by the Americans in the Philippine outbreak of 1902. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

January 13, 2017

Sugar Sun series glossary term #30: babaylan

Taking their name from the Visayan words for “woman” and “spirit,” the babaylans were “mystical women who wielded social and spiritual power in pre-colonial Philippine society,” according to Marianita “Girlie” Villariba. Because the Spanish viewed these women as a threat to the spread of Catholicism and patriarchy, the friars discredited the babaylans by spreading rumors that they were really vampire-like mythical creatures, or aswangs.

But babaylans did not have to be women. You could be a man—or you could be a man living under an adopted female identity, part of the long proto-transgender tradition in Southeast Asia. (By the way, the Philippines just elected their first transgender congresswoman.) Anyone who had a lifetime’s track record of helping the community—through both bandages (healers) or swords (warriors)—could be selected. This range of duties will be important to the way the identity of babaylans will evolve, especially at the turn of the twentieth century.

A dancer in Bago City’s 2015 Babaylan Festival.

A dancer in Bago City’s 2015 Babaylan Festival.The babaylan’s unique blend of nationalism and traditionalism pushed them to challenge both Americans and hacenderos at the same time. Babaylans spoke to God in their native language, and God told them to oppose the changes hitting their island. They believed that God inhabited all of nature, so the destruction of nature—particularly by industrial machines—was against the will of the universe. Men joined the movement in large numbers in the late 19th and early 20th century, particularly “discontented marginalized peasants,” according to Violeta Lopez-Gonzaga. This made the babaylans “a peasant protest movement with messianic, revivalistic, and nativistic overtones.”

The largest of these revolts was led by Dionisio Sigobela, also known as Papa (Pope) Isio. As historian Renato Constantino wrote, the situation in the early 1900s was particularly tenuous. War and revolution had closed ports and destroyed farmland. Natural disasters like drought, locusts, and rinderpest made the situation worse. Laborers were rapidly being replaced by machines, though both were in short supply. According to Constantino, only one-fifth of 1898’s arable land was planted four years later, in 1902.

Papa Isio might be dismayed to know that his anti-mercantile legacy has been turned into commercial gold. He is now given credit for a new, posh brand of Don Papa Rum.

Papa Isio might be dismayed to know that his anti-mercantile legacy has been turned into commercial gold. He is now given credit for a new, posh brand of Don Papa Rum.Times were tough, as Javier Altarejos will tell you in my upcoming novella, Tempting Hymn. In this scene, Javier reveals the babaylan ties of one of his former employees, Peping Ramos, whom you may remember as the disgruntled cane slasher who shot a young boy in Under the Sugar Sun. Javier is speaking to the hero of Tempting Hymn, an American named Jonas Vanderburg. Jonas is curious about the babaylans because he is falling in love with Peping’s daughter, Rosa Ramos.

“When I took over the hacienda, Peping was sure he could manage me.” Javier took a sip of his drink. “He was wrong.”

“So he ran off to join the madmen in the mountains?”

“They’re not all madmen—though they do attract every troublemaker on the island. The babaylan are more like the trade unionists you have in America.”

“But their popes and special charms—”

“Give them credibility.”

That credibility came from the traditional role of babaylans as priest(ess), sage, and seer. People admired the babaylans, and they would not stop admiring them just because the Americans said so. In fact, the Yanks were not able to put down Papa Isio’s insurrection until 1907—a tough reality for Americans to stomach since they had made such a big deal of declaring peace in 1902.

A Samareño

pulahan

amulet jacket from the 1890s, along with a rare photo of pulahans on the attack.

A Samareño

pulahan

amulet jacket from the 1890s, along with a rare photo of pulahans on the attack.The declaration fooled no one because Samar was rising up again, too. In fact, Samar had a very similar movement to the babaylans, complete with its own popes and sacred amulets: the pulahans (or “red pants”). The pulahans will be an important theme in my upcoming novel, Sugar Moon. Both the pulahans and the babaylans believed that:

an apocalyptic clash was coming;

they alone would survive; and

a new independent world order would be built upon the ashes of imperialism and industrialism.

If this sounds familiar, take a look at the Boxer Rebellion in China—same time, same motives, and same ideology. It’s not a coincidence. As a teacher of world history, imperialism, and comparative religions, movements like the babaylans and the pulahans represent the intersection of everything that interests me. And, of course, I like to work these complicated trends into kissing books. Enjoy!

Featured image includes three babaylan mandalas, created by artist Perla Daly.

January 5, 2017

Iris After the Incident: Love Post-Scandal

In the last twenty years or so, “Cringe humor,” with its “painful laughs,” has become a popular genre of television. Think The Office, especially the British version. We watch our favorite and least favorite characters embarrass themselves for our amusement. Wait—“amusement”? Some of these shows used real people and their real names. Time Magazine said of the Da Ali G Show: “The way Baron Cohen incorporated real people into his cringe-comedy was mean and unfair, but if it hadn’t been, it wouldn’t have been so revealing—or so funny.” I imagine for those people captured on camera, though, it was not just social awkwardness they felt afterwards. It was humiliation.

Where’s the line? We all have our little embarrassing moments we would like to forget. Many of us were socially awkward at one time or another. Maybe even outcasts. Growing up is hard. But what happens when our greatest humiliation comes in young adulthood, the time of life when we are supposed to be getting our act together? How do we go on? How do we find love? This is the reason why I was originally hesitant to read what you might call “cringe romance”: romance where one or both main characters must overcome a very public shame. But these stories need to be told. I am going to review one. And I ended up writing one, too.

The Chic Manila series and more can be found at Mina’s website.

The Chic Manila series and more can be found at Mina’s website.Mina V. Esguerra’s Iris After the Incident

Writing about humiliation and redemption is hard. It is a rare subject in romance because even if readers want their heroines to be “identifiable,” who wants to feel the humiliation of the main character so acutely? (Unless it is “humiliation kink,” which, yes, is a thing, and no one writes it better than Tamsen Parker in True North.)

I finally picked up the latest in the Chic Manila series after listening to Mina V. Esguerra talk about it on the Book Thingo’s podcast. Esguerra is the leader and pioneer of the #romanceclass group of Filipino writers who innovate and entertain at the same time. I have read others in her Chic Manila series and have loved them. Because kilig (feels). I love that Esguerra is not afraid to make heroines out of her previous antagonists—like Kimmy Domingo, the anti-heroine of Love Your Frenemies. And, yay, Kimmy is in this book, too!

But Iris is not just rough around the edges, like Kimmy. She is not a difficult person. She is quite nice, actually. She has a good job helping young women get scholarships for math and science degrees. She works hard and seeks little credit for it.

But she is broken all the same. She has been utterly humiliated on a worldwide scale. Worst of all, the family who shuns her for shaming them were complicit in making her shame public. It is a real Charlie Foxtrot, as the book blurb says:

Whether she likes it or not, Iris’s life has been divided into two: Before the Incident, and After the Incident. Something very private was made very public, and since then life has been about recovering from being shamed, discovering her true friends, and struggling to find a new normal.

The “something very private” is revealed less than ten percent into the story, but if you do not want to know what it is, stop reading here.

No, really. If you don’t want to know, you need to stop reading now.

Okay. You want to know. Yes, it’s a sex tape. But that sounds more sordid than it really was. Let Iris tell it:

I had sex with my boyfriend.

And we took a video.

And it accidentally got out on the internet.

People saw it.

When Iris says “accidentally,” she really does mean it. It should not have happened. But it did.

And in the beginning, it was still an anonymous sex tape. Life could go on—until a certain member of Iris’s family tried to “clear the air” and blew the lid right off the scandal. Iris’s humiliation is especially acute in the context of Philippine society. To be “walang hiya”—shameless or unconscionable— is one of the worst insults in the Tagalog language. Because Iris’s scandal becomes the whole family’s scandal, the family blames Iris for their collective misfortune.

The character Pascalle West of New Zealand’s addictive show Outrageous Fortune uses public nudity and a sex tape to launch what she hopes is a Kardashian-sized career.

The character Pascalle West of New Zealand’s addictive show Outrageous Fortune uses public nudity and a sex tape to launch what she hopes is a Kardashian-sized career.The full scope of Iris’s mortification may be hard for non-Filipino readers to understand. In the New Zealand television show Outrageous Fortune, a young woman named Pascal sets up and leaks her own sex tape in order to encourage notoriety. In the United States of Real Life, Kim Kardashian, Paris Hilton, and Rob Lowe made (or remade) careers out of this kind of “fame.” But for Iris Len-Larioca, the heroine of Esguerra’s novel, her sex tape is The End of Days. And she does what you might expect: she hides.

No, she really hides. She moves out of her family home into a small one-bedroom apartment, works a graveyard shift to avoid people in the office, and takes a demotion so she can cower behind a computer instead of wooing clients in person. For a while, she makes her own baking soda toothpaste to avoid the local convenience store.

Surprisingly, though, this broken woman still has a great sense of humor. She retells her own story as if she is writing a grant application—because her job is evaluating grant applications. Bitter sarcasm, self deprecation, and witty rejoinders abound. Iris’s voice is very Bridget-Jones-meets-Jessica-Jones. For example, in a particularly embarrassing scene on a cable car in Tagaytay, she shocks everyone with her honesty: “I’d opened the can of worms, anyway,” Iris thinks to herself. “Worms all over the place.”

The cable car at Tagaytay Highlands. You would not want to be trapped in here with your worst enemy—or your boyfriend’s ex.

The cable car at Tagaytay Highlands. You would not want to be trapped in here with your worst enemy—or your boyfriend’s ex.Esguerra has made Iris real. And unique. While her voice can be funny, it is also determined, level, and self-aware:

Sometimes I wished that I could be that person that no one singled out, that no one used as an example or a cautionary tale.

Good luck.

We could only move forward.

And Iris tries to move forward. The real story is, in fact, a romance. She tries to move forward with a man just as broken as she is—and for similar reasons. Gio Mella’s sexual skeletons were plastered all over the internet, too. He is also hiding, but in a different way. While Iris wants to know everything said on the internet about her—she has even set up email alerts—Gio has no internet and no phone. The Philippines is the twelfth largest cell phone market in the world, so that essentially makes Gio a unicorn. The lack of phone provides both conflict and wonderful feels in the resolution of the book.

You should know, though, that this book is not plot heavy. No one is kidnapped. No commandos storm the compound. A little bit of scholarship and cosmetic business is conducted—great alternatives to the typical billionaire romance trope—but all of these minor adventures merely serve to put two recluses into closer and closer contact with the world. And we get to see how they fare.

And there is sex. Wonderful, hot sex.

As Sue of Hollywood News Source wrote on Goodreads: “Iris After the Incident is the most feminist & empowering romance book I’ve ever read.” This book is sex-positive. Because the sex on Iris’s tape was consensual, sex itself is not ruined for Iris—just trust. Iris will have to learn to trust Gio, but she knows that she wants to have sex with him—and how. She and Gio have chemistry. Literally:

What I liked about him being on top was I got to watch him. Watched the tension in his arms, his shoulders, the way his hips, his torso, his entire body worked for his pleasure and mine. It was hot, and one of the best ways to cap an hour-long discussion on chemistry, in my humble opinion.

Obviously, there is a future for this couple. If I called it “happy for now,” that would be accurate, but it would minimize the strength of the relationship. “Happy for now” is “happily ever after” for people like Iris and Gio. “Ever after” is too much to think about. Now is the victory. They have now, and I know they will keep having now for many, many nows in the future.

My only quibble with the ending was that Tita Ara did not get vanquished in some spectacularly vivid fashion. I am not usually a mean-spirited person, but there it is.

Iris After the Incident takes on a devastating challenge, but it wins our hearts. It is both a cautionary tale—for my students who put private information on the internet all the time—and an encouragement to persevere.

Tempting Hymn, novella 1.5 of the Sugar Sun series

The heroine in my upcoming book, Rosa Ramos, goes through struggles similar to Iris, but in a very Edwardian era sort of way. Her mistakes were not broadcast on the internet, of course, because it is 1904. But that also means Rosa cannot hide away in the anonymity of modern society. Everyone in Bais knows her story—and if you’ve read Under the Sugar Sun, then you do, too. Rosa was left not only with a soiled reputation, but also a child to support. Adding to her problems—and everyone’s problems, really—are the issues of class and race in the American colonial period.

Mercedes Cabral as Rosa, and Daniel Craig as Jonas.

Mercedes Cabral as Rosa, and Daniel Craig as Jonas.My hero, Jonas Vanderburg, is broken, too—but in a very different way than Gio, Iris, or Rosa. This Midwestern missionary’s entire family died in Manila during the cholera epidemic of 1902—an unexpected sacrifice that Jonas has no intention of surviving alone. But Rosa, his nurse, needs to heal him so that she can support her son and redeem her professional reputation. Neither of them want a marriage of convenience, but you can’t always get what you want.

I look forward to sharing this story with you next month. Stay tuned for news. And, until then, read Iris After the Incident, the whole Chic Manila series, and the rest of the #romanceclass collection. I will leave you with a poem:

Poem by Barbara Jane Reyes.

Poem by Barbara Jane Reyes.Featured image is a trilogy of sorts: Iris After the Incident builds upon characters introduced in Love Your Frenemies, which in turn redeems a character you love to hate in My Imaginary Ex (pictured here in a three-book set).

December 29, 2016

New Year’s 1900: Y1.9K

Do you remember when New Year’s Eve 1999 was dominated by Y2K fears? (I know, it seems so naive and innocent, in retrospect.) Was there a similar Y1.9K crisis? What were Edwardian era fears? Thanks to the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America catalog of historical American newspapers from 1690 to the present, I was able to take a peak into the past. Through a search of front pages on New Year’s Eve 1899 and New Year’s Day 1900, I found both more and less than I expected.

In terms of hard news, the concerns were much as any other day, and any other year: war, terrorism, natural disasters, fires, religion, disease, health care, and politics. I did not keep track, but the most prevalent story seemed to be the Boer War in South Africa. And, no, the Americans were not a party to this conflict, but that did not mean Americans did not have opinions. (Do Americans ever not have opinions?) The war was a part of Britain’s attempt to annex two gold- and diamond-producing Boer Republics, where descendants of Dutch colonists lived. They wanted to stitch them into a British-federated South Africa—and they would eventually be successful. But, at the end of 1899, the Boers were winning. The Boers had besieged three cities and won several significant battles against the underprepared and undermanned British. In the United States, sentiment was generally unfavorable to British—especially in areas of large Germanic or Dutch settlement in the American Midwest, where newspapers depicted the British as mired in a “densely stupid policy.” According to the New York Sun, the American Irish also gave widespread support for Boers, based upon their hatred for British. “The enemy of my enemy is my friend.” And so it goes.

The Boer War was a guerrilla insurgency similar to the Philippine-American War—which was happening at the exact same time—and generally the papers who were critical of British efforts to “pacify” the Boers were maybe a little more honest about the difficulty of “pacifying” the Filipinos, too. One way they could do this was to cover an attempt by Filipino partisans to launch an assault on the funeral of General Henry Ware Lawton, the only American general to be killed in action during the conflict. The Americans caught wind of the plan and found a stash of four bombs meant to be dropped from the rooftops, along with five hundred rounds of ammunition and a few firearms. Other papers, interestingly enough, did not mention the “diabolical plot” at all. Instead they gave detailed coverage of the people at the funeral and the new cabinet planned by Governor Leonard Wood.

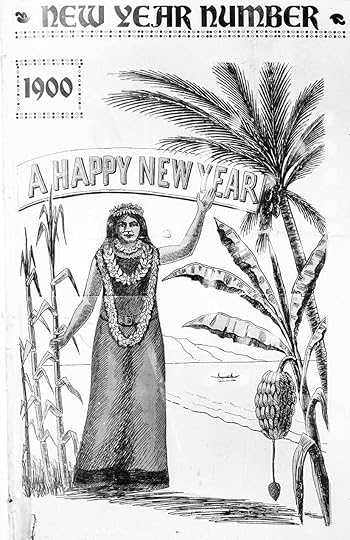

In Hawaii, the Pacific Advertiser welcomed the new year with an illustration of sugar cane, banana trees, and palm trees.

In Hawaii, the Pacific Advertiser welcomed the new year with an illustration of sugar cane, banana trees, and palm trees.Some papers were admiringly local in their coverage. Both Hawaii papers (The Hawaiian Star and The Evening Bulletin) were devoted to either island news or, at their most global, Pacific Rim events. One such story was the Black Plague outbreak in China. The Tombstone Epitaph reported on local weather and wedding announcements on the front page. Both Richmond (VA) papers were darned near full of advertisements—for the city itself. The Richmond Dispatch reported on “A Year of Great Prosperity” and that the “Future [Would Be] a Brilliant One.” The Times (of Richmond) proudly proclaimed that “Everywhere in Virginia People Busy and Happy.” How nice. The Brownsville (TX) Daily Herald was an odd little paper.Their front page was devoted to vignettes and humorous stories collected from other papers. One revealing piece applauded how the people of Leadville, Texas, ran two law-abiding Chinese (“celestials”) out of town.

“M’Coy Won in Five Rounds” because “Maher was outclassed.” Even in 1900, sports dominated some papers. From the New York Evening World.

“M’Coy Won in Five Rounds” because “Maher was outclassed.” Even in 1900, sports dominated some papers. From the New York Evening World.And, of course, some papers did not cover hard news at all. The New York Evening World’s front page was dedicated to the results of the McCoy-Maher boxing bout. Pugilism mattered to the readers of the Daily Inter Mountain of Butte, Montana, as well.

The Ocala (FL) Evening Star and the Morning Appeal of Carson City, Nevada were all advertisements. One product featured in the Carson City paper was one of the biggest patent medicines of the turn of the century: “Dr. Pierce’s Favorite Prescription for the relief of the many weaknesses and complaints particular to females.” This gave a “fountain of health for weak and nervous women.” The nostrum was a botanical mix of many relaxants designed mostly to help with menstrual pain—though no one would say such a thing, of course. It was just a “weakness” or “complaint.”

An advertisement and bottle of Dr. Pierce’s Favorite Prescription. Images courtesy of the Library of Congress and the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry.

An advertisement and bottle of Dr. Pierce’s Favorite Prescription. Images courtesy of the Library of Congress and the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry.Y1.9K did have some technological fears, especially centered around the newest invention of the day: the horseless carriage, or the automobile. There were no alarmist articles about how motorized transport would lead to lazier Americans, more fractured and transient communities, suburbs, and eventually mechanized weapons. Nope, the sentiment was more subtle, as captured in a political cartoon of Father Time saying: “They want me to try that. Guess I’ll stick to wings.”

Cartoon from the St. Paul Globe.

Cartoon from the St. Paul Globe.I am not sure what I expected when I began this search, but I think I wanted the papers to seem a little silly. A little quaint. (And Dr. Pierce’s medicine was both of those.) In the end, the biggest surprise may have been the optimism of some of the papers. At first I snickered, but now I realize that this positivity is the very reason I write romance. After being the cynical, hard-headed history teacher all day long, I love the idea that love can triumph over all. Maybe not “everywhere,” but at least somewhere people can be “busy and happy”—even if in my mind. May your New Year be full of happily-ever-afters.

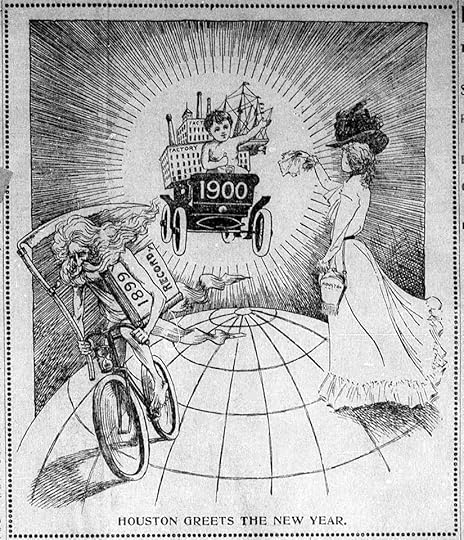

New Year’s wishes from the Houston Daily Post.

New Year’s wishes from the Houston Daily Post.Featured image banner is from the Richmond (VA) Dispatch.

December 22, 2016

Sugar Sun series glossary term #29: daigon (or daygon)

Christmas in New Hampshire feels surprisingly quiet this year. The holiday season traditionally begins the day after Thanksgiving on “Black Friday”—marking the start of the shopping season, which will bring stores out of the red and into the black with holiday sales. Recently Black Friday has become Black-Thursday-the-hour-after-you-load-the-dirty-plates-in-the-dishwasher. And then this year I noticed advertisements for Christmas-themed books, movies, and products on or before Halloween.

Amateurs.

The Philippines celebrates the longest Christmas season in the world, starting on September 1st—when you’ve officially entered the “Ber” months—and lasting through the beginning of January. (Or Easter, according to how long some of my neighbors had their decorations up.) Once September arrives, stores break out the holiday albums, parols are offered for sale alongside highways, and malls get so crowded that you literally cannot drive by them. Seriously, don’t plan on it. And if you do, don’t fight the standstill. Just put on some good tunes, sit back, and relax. You’re going nowhere quick.

This may not be a picture of me driving by SM Southmall in Christmas season, but it is close enough. Photo by Matzky.

This may not be a picture of me driving by SM Southmall in Christmas season, but it is close enough. Photo by Matzky.But here’s the secret: if you want to drive anywhere in Manila during Christmas season, do so on Christmas Eve. The roads are deserted. The toll booths are unmanned. Skyway is free for everybody!

This “good night,” Noche Buena, is the real holiday. The day begins with a midnight (or pre-dawn) mass called the Misa de Gallo, or mass of the rooster. (Because by the time you leave church, the roosters are crowing.) The evening is for family dinners, and by midnight on Christmas Day the faithful head back to mass.

There is one tradition that may have gotten lost in big city life in Manila and elsewhere: pastores, or shepherds. This pageant-carol of the Nativity drama came from Mexico, thanks to sailors on the Spanish galleons. Its details, though, soon varied by region. The villains could be anyone from the devil (in half-man, half-monkey form) to King Herod to snooty homeowners.

A cultural dance performance at the 2015 Daygon performance in Dumaguete. Photo from Dumaguete.com.

A cultural dance performance at the 2015 Daygon performance in Dumaguete. Photo from Dumaguete.com.Today, in many places, the daigon has become a set piece dancing and singing performance. But in the early 1900s Visayas, the daigon (or daygon, from “starting a fire” or “lighting up”) was more like what I described in Under the Sugar Sun:

Javier guided Georgina to a house with a pronounced balcony, the perfect place to start the daigon. Mary, Joseph, and a chorus of shepherds and angels were already assembled. Mary was dressed in a blue and white gown, her “pregnant” belly stuffed full of pillows. The band fell silent as the holy couple sang a plea for shelter to the owners of the house. One did not have to know Visayan to understand the girl’s predicament.

The owners of the house responded in turn, and Javier translated in a whisper. “They’re saying that the house is already bursting with people.”

Then Mary sang again. “She’s promising them heavenly rewards,” he explained. “I think a literal translation is that ‘their names will be written in the book of the chosen few.’”

“It’s beautiful,” the maestra whispered. “What did the people in the house just say?”

“They’ve turned her down. They said their house is not for the poor.”

“How awful.”

He found Georgina’s innocence endearing. No doubt she knew the story of the Nativity as well as he did—probably better, since she actually went to all the novenas—but her rapt expression made it seem like she was hearing the story for the first time.

They trailed the crowd to the next house, where Joseph begged for a place for his wife, “even in the kitchen,” but was told that the mansion was “only for nobles.” When Mary insisted, the doña threatened to let loose her dogs on them.

Georgina looked around, noticing that they were almost at the school building. “They won’t sing to us, will they? More importantly, I don’t have to sing back?” She looked truly alarmed.

“No, don’t worry. They’ll finish before that, at the ‘stable’—by which I mean the church. The crowd and the band will amble on, though, begging for refreshments, so we should go prepare.”

Georgina’s eyes lit up. “Your aguinaldos!”

He laughed and squeezed her hand on his arm. “Exactly—including your favorite: chocolate.”

There is a fair amount of seduction over food in that book, even at fiesta. Maybe especially at fiesta!

For a young woman, landing the role of Mary was like being crowned the homecoming queen, though she had better be able to sing, too. Fortunately, my character Rosa Ramos was both pretty and talented:

Singing had pulled her through her childhood, proving that she was more than just the daughter of a disciplined maid and an undisciplined field hand. For a time, it had made her the best known fifteen-year-old in Bais. Out of all the girls on all the haciendas, she had been cast as the Virgin Mary in the local Christmas pageant. It said something about her life back then that she could not have imagined anything as grand anywhere in the world. She could have been crowned queen of Spain and still not been as happy as she had been that night.

That was a little holiday gift for you—a taste of Tempting Hymn, coming early 2017. Here is another gift: the lighting of the huge Christmas tree at Bais.

I hope everyone has a Merry Christmas (Maligayang Pasko!), Happy Hanukkah, Happy Kwanzaa, and Happy New Year.

Featured image of the 2010 nativity from the Dusit Thani hotel in Makati, Metro Manila. Creative commons photo courtesy of Daniel Go.

December 16, 2016

Gibson Girls Gone Wild!

In February I will be boarding a plane for Manila. It will take me 24 hours airport to airport, and that will feel like a long time. I will probably complain about how tired I am, or how small airline seats have become. Both will be true.

But my Edwardian sisters—known as “Gibson girls” after popular illustrator Charles Dana Gibson—would be shocked by how spoiled I am. For them, a trip from Boston to the Philippines would have taken seven weeks. And they thought themselves lucky, since the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal cut the trip in half. Their bargain ticket would have cost $120 in 1900—the equivalent of almost $3500 today. My ticket cost around $800.

I also have another advantage: knowledge. I know what the Philippines are like. Things may have changed in the last five years, as things do, but generally I know what I will find. But my three Gibson girls featured here—Mary Fee, Annabelle Kent, and Rebecca Parrish, M.D.—did not. These women either had no information or bad information about the Philippines. For example, a United States senator, John W. Daniel, from Virginia explained that “there are spotted people there, and, what I have never heard of in any other country, there are striped people there with zebra signs upon them.” To you or me such drivel is beyond racist to the point of being ludicrously stupid, but Senator Daniel thought this information important enough to pass along in the middle of a government hearing.

If travel to the Philippines was long, expensive, and potentially dangerous, why did women like Fee, Kent, and Parrish do it? Their reasons probably varied. Fee, a teacher, may have gone for the good salary; Kent wanted to prove that she could travel the globe alone; and Parrish was a medical missionary whose faith led her to the islands. But there is one thing all three women had in common: they were more adventurous than the average man of their day. And they were probably more intrepid than me.

From left to right: the cover of Mary H. Fee’s memoir (from the New York Society Library); a portrait of Annabelle Kent in China (from her book Round the World in Silence); the legacy of Rebecca Parish as seen through a nurses’ basketball team for the Mary Johnston Hospital in 1909 (print for sale on eBay); and the classic Gibson girl image on a music score (courtesy of the Library of Congress).

From left to right: the cover of Mary H. Fee’s memoir (from the New York Society Library); a portrait of Annabelle Kent in China (from her book Round the World in Silence); the legacy of Rebecca Parish as seen through a nurses’ basketball team for the Mary Johnston Hospital in 1909 (print for sale on eBay); and the classic Gibson girl image on a music score (courtesy of the Library of Congress).Let’s start with Mary Fee, principal of the Philippine School of Arts and Trades in Roxas City. Fee was one of the first teachers sent by the U.S. Government to establish a secular, coeducational, public school system throughout the Philippines. The Thomasites, as they were called, were sent all over the islands with their Baldwin Primers to read lessons on snow, apples, and George Washington—and none of the students knew what the heck they were talking about. Mary Fee realized that the point was to teach her students to read and write in English, not to have a comprehensive understanding of American meteorology. Soon she was one of four authors (including another woman) of a new Philippine Education series. The First Year Book had lessons about Ramon and Adela, not Jack and Jill. They learned about carabao, not cows. Stories included the American flag, but it was small and in black-and-white, not a full-page color spread. The women went to market for fish and mangoes, and they wore traditional clothing. In other words, the book made sense to the children who had to read it.

Two pages from The Baldwin Primer and two from The First Year Book, showing the differences in content for the Philippine audience.

Two pages from The Baldwin Primer and two from The First Year Book, showing the differences in content for the Philippine audience.I relied upon Fee’s memoir, A Woman’s Impressions of the Philippines, for help in creating my character Georgina Potter in Under the Sugar Sun. I exercised artistic license, of course: Fee’s faithful description of the Christmas Eve pageant, for example, was turned into a courtship opportunity for my hero, Javier Altarejos. Though Fee would eventually return to the United States—not marry a Filipino sugar baron—I am happy to say that her spirit lives on.

In comparison to my careful researching of Mary Fee, I stumbled upon Annabelle Kent’s raucous description of arriving in Manila by ship. While everyone else had horrible seasickness, Kent thought the bumpy ride a blast. The ship bucked like a bronco, and she reveled in it. As I read more, though, I found Kent’s explanation for her sturdy sea-legs: she was deaf. She traveled the globe by herself without an ASL interpreter, and that takes guts. It seemed to have started on a type of dare. Kent wrote:

A deaf young lady made the remark to me once that it was a waste of time and money for a deaf person to go to Europe, as she could get so little benefit from the trip. I told her that as long as one could see there was a great deal one could absorb and enjoy.

I knew right then that Annabelle Kent would be my model for a new character, Della Berget, in Hotel Oriente. At a time when American senators were postulating about people striped like zebras, Kent was getting a steamer and seeing everything for herself, including schools for the deaf in China and Japan. The book is the most positive, joyful travel memoir I have ever read.

My final Gibson girl, Rebecca Parrish, was used to being a trendsetter. She was a doctor at a time when medicine was a possible career choice for a woman, but not a common one. And, in the Philippines, it was unheard of. One of her first skeptical patients asked, “Can a woman know enough to be a doctor?” Parrish had to prove herself a million times, by her own account, but she did.

Philippines stamp commemorating the centennial of Parrish’s creation, the Mary Johnson Hospital. Image courtesy of Colnect stamp catalog.

Philippines stamp commemorating the centennial of Parrish’s creation, the Mary Johnson Hospital. Image courtesy of Colnect stamp catalog.Parrish built a 55-bed hospital in Tondo, the Mary Johnston Hospital, that operated on the principle that no one could be turned away. The hospital began its working life fighting a cholera epidemic but transitioned into a maternity clinic with a milk feeding station. Today, it is a teaching hospital specializing in internal medicine, obstetrics, gynecology, and pediatrics. Parrish also opened a training institute for nurses. If the doctor seems like a busy woman, you are correct. She wrote: “Hundreds of days—thousands of days, I worked twenty hours of the twenty-four among the sick, doing all that was in my power to do my part, and hoping the best that could be had for all.” I get tired just thinking about it.

Maybe these Gibson girls—Mary Fee, Annabelle Kent, and Rebecca Parrish—did not go “wild” in the cheap DVD series kind of way, but by contemporary standards they were braver than Indiana Jones. My trip to Manila will be tame by comparison—though I think they would have enjoyed the in-flight movies.

Featured image is “Girls Will Be Girls” by Charles Dana Gibson, found at Blog of an Art Admirer.

Sugar Sun Series Extras

- Jennifer Hallock's profile

- 38 followers