J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 403

February 12, 2018

Reading: Robert Allen (2009): The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective

Robert Allen (2009): The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective | <http://amzn.to/2mR3bKX>

Start with the mysterious "Pseudoerasmus": Random thoughts on critiques of Allen���s theory of the Industrial Revolution:

I love the work of Robert Allen... steel... the Soviet Union... English agriculture. And his little book on global economic history���is there a greater marvel of illuminating concision than that?... His point of departure is always the very concrete reasons that a firm or an industry or a country is more productive than another. I���m not rubbishing institutions or culture as explanations���I���m just saying, Allen���s virtue is to start with problems of production first. Yet I always find myself in the peculiar position of loving his work like a fan-girl and disagreeing with so much of it. In particular, I���m sceptical of his theory of the Industrial Revolution.

Allen has been advocating for at least 20 years now that... England���s high wages relative to its cheap energy and low capital costs biased technical innovation in favour of labour-saving equipment, and that is why it was cost-effective to industrialise in England first,��before the rest of Europe (let alone Asia).... Allen���s is not a monocausal theory... but his distinctive contribution is the high-wage economy.... The theory is appealing, in part, because the technological innovations of the early Industrial Revolution were not exactly rocket science (a phrase used by Allen himself), so one wonders why they weren���t invented earlier and elsewhere. (Mokyr paraphrasing Cardwell said something like nothing invented in the early IR period would have puzzled Archimedes.) But... as Mokyr has tirelessly argued, inventions were too widespread across British society to be a matter of just the right incentives and expanding markets���and this is a point now being massively amplified by Anton Howes....

Kelly, Mokyr, & �� Gr��da (2014)... pointed out... [that] Allen must��assume��that unit labour costs (wage divided by labour productivity) were... higher. But��if the��Anglo-French wage gap were matched by a commensurate labour productivity gap,��then the labour cost to the employer would have been��the same in the two countries.... Besides, you already had capital-intensive production techniques in several sectors well before the classic industrial revolution period���especially in silk and calico-printing. Silk-throwing (analogous to spinning in cotton) was mechanised in Italy before 1700. The idea was pirated by Lombe��who set up a water-powered silk-throwing factory��circa 1719, and he was imitated��by many others by��the 1730s. Then you had heavily machine-dependent��printing works for textiles (especially calicoes) in many European cities��before the canonical industrial revolution period.��None of these seemed to require Allen���s�����high wage economy���. (Not to mention, Allen���s model has implications for the diffusion of the Industrial Revolution, and Scottish industrialisation was almost simultaneous with the English one, despite wage differences.)

Nonetheless,��I had mentally reconciled Allen and Mokyr in the manner of��Crafts by considering Mokyr = supply of inventions, Allen = demand. But there has been a spate of critiques.... Humphries & Schneider... show that the estimated 1 million women and children who spun yarn with��wool, linen, and cotton in their rural homes were paid��much��lower wages than Allen���s narrative has relied on: ~4 d [pence] per day, rather than the >8d/day assumed in Allen.��And one of the showcases of his��theory is the series of inventions mechanising yarn spinning!... persuasive, but it���s also theoretically compelling. Men, especially in big cities, may have been paid higher wages, but women and children in the countryside were not. This makes early modern England much more like a ���surplus labour economy��� with an ���unlimited supply of labour��� �� la Arthur Lewis.... Labour market monopsonists also loom large in modern development microeconomics!...

Outline:

The Industrial Revolution and the pre-industrial economy

The Commercial Revolution generated a unique structure of wages and prices in eighteenth-century Britain

The Industrial Revolution simply would not have been profitable in other times and places

The slow adoption of British technology was because the first generation technologies were not profitable to adopt outside Britain

But the third generation technologies were

The high-wage economy of pre-industrial Britain

The agricultural revolution

The cheap energy economy

Why England succeeded

Why was the Industrial Revolution British

The steam engine

Cotton

Coke smelting

Inventors, Enlightenment, and human capital

From Industrial Revolution to modern economic growth

Eight Orienting Questions:

Pseudoerasmus says: Mokyr = supply; Allen = demand; both were essential. No Enlightenment, no Industrial Revolution. Is he (probably) right?

How do we assess how much encouragement was provided to inventors and innovators by Britain's uniquely high labor/energy price ratio?

What are the other places that Allen has in mind (since Hiero of Alexandria's aeropile in which building a first generation "steam engine" would have been possible as a marvel?

Say that there are three breakpoints in which the rate of growth of the global average efficiency of labor E jumps--the Commercial Revolution, which sees the growth rate of E jump from 0.1%/year to 0.3%/year; the Industrial Revolution, with sees the growth rate of E jump from 0.3%/year to 1.4%/year; and then the coming of Modern Economic Growth around 1870 which sees the growth rate of E jump from 1.4%/year to 5.2%/year. What would the world be like if that third jump had not occurred? What if that second jump had not occurred?

Had French Marshal Tallard won at Blenheim and French Marshal Villeroy won at Ramillies, France would have had the resources to build a fleet to win control over Atlantic trade. What form would a French-led European economy have taken in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries? Why is Allen so certain that it would not have created a profession of engineering?

Weren't there other roads to industrialization that involved technological change that economized on something other than labor--on energy, on capital, on other scarce inputs of one sort or another?

So you economize on labor by inventing the spinning machine and the steam engine. Why does it go further? What are the forward inventive linkages here?

If there were no oats--which British workers refused to eat in bulk--Allen would characterize Britain not as a high-wage but as an overvalued exchange rate economy. But such economies typically export not manufactures but financial and other services. How is it that Britain exports manufactures?

Allen's conclusion:

I have argued that the famous inventions of the British Industrial Revolution were responses to Britain's unique economic environment and would not have been developed anywhere else.... Buy why did those inventions matter?.... Weren't there alternative paths to the twentieth century? These questions are closely related to another... asked by Mokyr: why didn't the Industrial Revolution peter out after 1815?... [O]ne-shot rise[s] in productivity [before] did not translate into sustained economic growth. The nineteenth century was different--the First Industrial Revolution turned into Modern Economic Growth. Why? Mokyr's answer... that scientific knowledge increased enough to allow continuous invention [is incomplete]....

Britain's pre-1815 inventions were particularly transformative.... Cotton was the wonder industry.... [T]he great achievement of the British Industrial Revolution was... the creation of the first large engineering industry that could mass-produce productivity-raising machinery. Machinery production was the basis of three developments that were the immeiate explanations of the continuation of economic growth until the First World War... (1) the general mechanization of industry; (2) the railroad; and (3) steam-powered iron ships. The first raised productivity... the second and third created the global economy and the international division of labor... (O'Rourke and Williamson, 1999). Steam... accounted for close to half of the growth in labor productivity in Britain in the second half of the nineteenth century (Crafts 2004). The nineteenth-century engineering industry was a spin-off from the coal industry. All three of the developments... depended on two things: the steam engine and cheap iron....

Cotton played a supporting role in the growth of the engineering industry.... The first is that it grew to immense size.... Mechanization in other activities did not have the same potential... global industry with.. price-responsive demand... cotton... sustained the engineering industry by providing it with a large and growing market for equipment....

There was a great paradox... the macro-inventions of the eighteenth century... increased the demand for capital and energy relative to labour. Since capital and energy were relatively cheap in Britain, it was worth developing the macro-inventions there and worth using them in their early, primitave forms. These forms were not cost-effective elsewhere.... However, British engineers improved this technology.... This local learning often saved the input that was used excessively in the early years of the invention's life and which restricted its use to Britain. As the coal consumption of rotary steam power declined from 35 pounds per horsepower-hour to 5 pounds, it paid to apply steam power to more and more uses.... Old fashioned, thermally inefficient steam engines were not "appropriate" technology for countries where coal was expensive. These countries did not have to invent an "appropriate" technology for their conditions, however. The irony is that the British did it for them....

The British inventions of the eighteenth century--cheap iron and the steam engine, in particular--were so transformative.... The technologies invented in France--in paper production, glass, and knitting--were not, The French innovations did not lead to general mechanization or globalization.... The British were not more rational or prescient than the French... simply luckier in their geology. the knock-on effect was large, however: there is no reason to believe that French technology would have led to the engineering industry, the general mechanization of industrial processes, the railway, the steamship, or the global economy.... [T]here was only one route to the twentieth century--and it traversed northern Britain.

Cf: Jane Humphries: The Lure of Aggregates and the Pitfalls of the Patriarchal Perspective: A Critique of the High Wage Economy Interpretation of the British Industrial Revolution <http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00663.x/pdf>

Cf: Robert C. Allen (2011): Why the Industrial Revolution Was British: Commerce, Induced Invention and the Scientific Revolution, Economic History Review 64, pp. 357-384. <http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2010.00532.x/pdf>

Everytime I reread http://www.ehs.org.uk/ehs/conference2007/Assets/AllenIIA.pdf, I think: Robert Allen is a fracking genius!:

The Industrial Revolution is one of the most celebrated watersheds in human history. It is no longer regarded as the abrupt discontinuity that its name suggests, for it was the result of an economic expansion that started in the sixteenth century. Nevertheless, the eighteenth century does represent a decisive break in the history of technology and the economy. The famous inventions���the spinning jenny, the steam engine, coke smelting, and so forth���deserve their renown1, for they mark the start of a process that has carried the West, at least, to the mass prosperity of the twenty-first century. The purpose of this essay is to explain why they occurred in the eighteenth century, in Britain, and how the process of their invention has transformed the world... [���]

The industrial revolution was fundamentally a technological revolution, and progress in understanding it can be made by focussing on the sources of invention.... [T]he reason the industrial revolution happened in Britain, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, was not because of luck (Crafts 1977) or British genius or culture or the rise of science. Rather it was Britain���s success in the international economy that set in train economic developments that presented Britain���s inventors with unique and highly remunerative possibilities. The industrial revolution was a response to the opportunity��� [���]

What commercial success did for Britain was to create a structure of wages and prices that differentiated Britain from the continent and, indeed, Asia: In Britain, wages were remarkably high and energy cheap. This wage and price history was a fundamental reason for the technological breakthroughs of the eighteenth century whose object was to substitute capital and energy for labour. Scientific discoveries and scientific culture do not explain why Britain differed from the rest of Europe. They may have been necessary conditions for the industrial revolution, but they were not sufficient: Without Britain���s distinctive wage and price environment, Newton would have produced as little economic progress in England as Galileo produced in Italy... [...]

The working assumption of this paper is that technology was invented by people in order to make money.... [L]abour was particularly expensive and energy particularly cheap in Britain, so inventors in Britain were led to invent machines that substituted energy and capital for labour.... The scale of the mining industry in eighteenth century Britain was much greater than anywhere else, so the return to inventing improved drainage machinery (a.k.a. the steam engine) was greater in Britain than in France or China. Third, patents that allow the inventor to capture all of the gains created by his invention raise the rate of return and encourage invention... [...]

Britain was a high wage economy in four senses:1. At the exchange rate, British wages were higher than those of its competitors. 2. High silver wages translated into higher living standards than elsewhere. 3. British wages were high relative to capital prices. 4. Wages in northern and western Britain were exceptionally high relative to energy prices...

The different trajectories of the wage-rental ratio created different incentives to mechanize production in the two parts of Europe. In England, the continuous rise in the cost of labour relative to capital led to an increasingly greater incentive to invent ways of substituting capital for labour in production. On the continent, the reverse was true���. It was not Newtonian science that inclined British inventors and entrepreneurs to seek machines that raised labour productivity but the rising cost of labour... [...]

Britain���s unusual wages and prices were due to two factors. The first was Britain���s success in the global economy, which was in part the result of state policy. The second was geographical���Britain had vast and readily worked coal deposits���. The superior real wage performance of northwestern Europe was due to a boom in international trade���. In a mercantilist age, imperialism was necessary to expand trade, and greater trade led to urbanization.... Coal deposits were a second factor contributing to England���s unusual wage and price structure���. First, inexpensive coal raised the ratio of the price of labour to the price of energy (Figure 4), and, thereby, contributed to the demand for energy-using technology. In addition, energy was an important input in the production of metals and bricks, which dominated the index of the price of capital services.... [C]oal is a ���natural��� resource, but the coal industry was not a natural phenomenon.... It was the growth of London in the late sixteenth century, however, that caused the coal industry to take off. The Dutch cities provide a contrast that reinforces the point (Pounds and Parker 1957, de Vries and van der Woude 1997, Unger 1984). The coal deposits that stretched from northeastern France across Belgium and into Germany were as useful and accessible as Britain���s.... The pivotal question is why city growth in the Netherlands did not precipitate the exploitation of Ruhr coal in a process parallel to the exploitation of Northern English coal. Urbanization in the Low Countries also led to a rise in the demand for fuel. In the first instance, however, it was met by exploiting Dutch peat. This checked the rise in fuel prices, so that there was no economic return to improving transport on the Ruhr or resolving the political-taxation issues related to shipping coal down the Rhine. Once the Newcastle industry was established, coal could be delivered as cheaply to the Low Countries as it could be to London, and that trade put a ceiling on the price of energy in the Dutch Republic that forestalled the development of German coal. This was portentous: Had German coal been developed in the sixteenth century rather than the nineteenth, the industrial revolution might have been a Dutch-German breakthrough rather than a British achievement... [...]

The following generalizations apply to many inventions including the most famous: 1. The British inventions were biased. They were labour saving and energy and capital using.... 2. As a result of 1, cost reductions were greatest at British factor prices, so the new technologies were adopted in Britain and not on the continent.... [C]oke smelting was not profitable in France or Germany before the mid-nineteenth century (Fremdling 2000). Continuing with charcoal was rational behaviour in view of continental factor prices. This result looks general; in which case, adoption lags mean that British technology was not cost-effective at continental input prices. 3. The famous inventions of the industrial revolution were made in Britain rather than elsewhere in the world because the necessary R&D was profitable in Britain (under British conditions) but unprofitable elsewhere.... 4. Once British technology was put into use, engineers continued to improved it, often by economizing on the inputs that were cheap in Britain. This made British technology cost-effective in more places and led to its spread across the continent later in the nineteenth century.... The theory advanced here explains the technological breakthroughs of the industrial revolution in terms of the economic base of society���natural resources, international trade, profit opportunities. Through their impact on wages and prices, these prime movers affected both the demand for technology and its supply... [...]

Why did the French ignore the new spinning machines? Cost calculations for France are not robust, but the available figures indicate that jennies achieved consistent savings only at high count work, which was not the typical application (Ballot 1923, pp. 48-9). In France, a 60 spindle jenny cost 280 livre tournois in 1790 (Chassagne 1991, p. 191), while a labourer in the provinces earned about three quarters of a livre tournois per day, so the jenny cost 373 days labour. In England, a jenny cost 140 shillings and a labourer earned about one shilling per day, so the jenny was worth 140 days labour (Chapman and Butt 1988, p. 107). In France, the value of the labour saved with the jenny was not worth the extra capital cost, while in England it was. French cost comparisons show that Arkwright���s water frame, a much more capital intensive technique, was no more economical than the jenny. The reverse was true in England where water frames were rapidly overtaking jennies. The French lag in mechanization was the result of the low French wage��� [���]

Why did the industrial revolution lead to modern economic growth? I have argued that the famous inventions of the British industrial revolution were responses to Britain���s unique economic environment and would not have been developed anywhere else. This is one reason that the Industrial Revolution was British. But why did those inventions matter? The French were certainly active inventors, and the scientific revolution was a pan-European phenomenon. Wouldn���t the French, or the Germans, or the Italians, have produced an industrial revolution by another route? Weren���t there alternative paths to the twentieth century? These questions are closely related to another important question asked by Mokyr: Why didn���t the industrial revolution peter out after 1815? He is right that there were previous occasions when important inventions were made. The result, however, was a one-shot rise in productivity that did not translate into sustained economic growth. The nineteenth century was different���the First Industrial Revolution turned into Modern Economic Growth. Why? Mokyr���s answer is that scientific knowledge increased enough to allow continuous invention. Technological improvement was certainly at the heart of the matter, but it was not due to discoveries in science���at least not before 1900. The reason that incomes continued to grow in the hundred years after Waterloo was because Britain���s pre-1815 inventions were particularly transformative, much more so than continental inventions. That is a second reason that the Industrial Revolution was British and also the reason that growth continued throughout the nineteenth century.... The nineteenth century engineering industry was a spin-off of the coal industry. All three of the developments that raised productivity in the nineteenth century depended on two things���the steam engine and cheap iron. Both of these, as we have seen, were closely related to coal. The steam engine was invented to drain coal mines, and it burnt coal. Cheap iron required the substitution of coke for charcoal and was prompted by cheap coal. (A further tie- in with coal was geological���Britain���s iron deposits were often found in proximity to coal deposits.) There were more connections: The railroad, in particular, was a spin-off of the coal industry. Railways were invented in the seventeenth century to haul coal in mines and from mines to canals or rivers. Once established, railways invited continuous experimentation to improve road beds and rails. Iron rails were developed in the eighteenth century as a result, and alternative dimensions and profiles were explored. Furthermore, the need for traction provided the first market for locomotives. There was no market for steam-powered land vehicles because roads were unpaved and too uneven to support a steam vehicle (as Cugnot and Trevithick discovered). Railways, however, provided a controlled surface on which steam vehicles could function, and colliery railways were the first purchasers of steam locomotives. When George Stephenson developed the Rocket for the Rainhill trials, he tested his design ideas by incorporating them in locomotives he was building for coal railways. In this way, the commercial operation of primitive versions of technology promoted further development as R&D expenses were absorbed as normal business costs.... The reason that the British inventions of the eighteenth century���cheap iron and the steam engine, in particular���were so transformative was because of the possibilities they created for the further development of technology. Technologies invented in France���in paper production, glass, knitting���did not lead to general mechanization or globalization. One of the social benefits of an invention is the door it opens to further improvements. British technology in the eighteenth century had much greater possibilities in this regard than French inventions. The British were not more rational or prescient than the French in developing coal-based technologies: The British were simply luckier in their geology. The knock-on effect was large, however: There is no reason to believe that French technology would have led to the engineering industry, the general mechanization of industrial processes, the railway, the steam ship, or the global economy. In other words, there was only one route to the twentieth century���and it went through northern Britain...

Cf: <https://www.icloud.com/keynote/04hxeReqzLNViuLXuAn2bEFFA#2017-02-01_Allen_.IEH>

Thomas Jefferson: "I Tremble for My Country..."

Live from Monticello: Human rationality can be thought of in three ways: as rational beings, as rational_izing_ beings, and as debating beings who reach rough consensus and are much smarter collectively than they were individually. One of the attractions���in the sense that we find ourselves compelled to register, wrestle with, admire, and loathe him whether we will or no���of Thomas Jefferson is that he was outsized and gigantic in all three of these aspects: Thomas Jefferson (1981): Notes on the State of Virginia, Query XVIII: Manners: "It is difficult to determine on the standard by which the manners of a nation may be tried, whether catholic, or particular.... It is more difficult for a native to bring to that standard the manners of his own nation, familiarized to him by habit. There must doubtless be an unhappy influence on the manners of our people produced by the existence of slavery among us...

...The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. Our children see this, and learn to imitate it; for man is an imitative animal. This quality is the germ of all education in him. From his cradle to his grave he is learning to do what he sees others do. If a parent could find no motive either in his philanthropy or his self-love, for restraining the intemperance of passion towards his slave, it should always be a sufficient one that his child is present. But generally it is not sufficient. The parent storms, the child looks on, catches the lineaments of wrath, puts on the same airs in the circle of smaller slaves, gives a loose to his worst of passions, and thus nursed, educated, and daily exercised in tyranny, cannot but be stamped by it with odious peculiarities. The man must be a prodigy who can retain his manners and morals undepraved by such circumstances.

And with what execration should the statesman be loaded, who permitting one half the citizens thus to trample on the rights of the other, transforms those into despots, and these into enemies, destroys the morals of the one part, and the amor patriae of the other? For if a slave can have a country in this world, it must be any other in preference to that in which he is born to live and labour for another: in which he must lock up the faculties of his nature, contribute as far as depends on his individual endeavours to the evanishment of the human race, or entail his own miserable condition on the endless generations proceeding from him.

With the morals of the people, their industry also is destroyed. For in a warm climate, no man will labour for himself who can make another labour for him. This is so true, that of the proprietors of slaves a very small proportion indeed are ever seen to labour. And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath?

Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep for ever: that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation, is among possible events: that it may become probable by supernatural interference! The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest.

���But it is impossible to be temperate and to pursue this subject through the various considerations of policy, of morals, of history natural and civil. We must be contented to hope they will force their way into every one���s mind. I think a change already perceptible, since the origin of the present revolution. The spirit of the master is abating, that of the slave rising from the dust, his condition mollifying, the way I hope preparing, under the auspices of heaven, for a total emancipation, and that this is disposed, in the order of events, to be with the consent of the masters, rather than by their extirpation.

February 11, 2018

Should-Read: We are giving away a huge amount of fiscal s...

Should-Read: We are giving away a huge amount of fiscal space that we will in all likelihood very much want in the future, we are giving our income distribution another whack in a destructive direction, and we are getting very, very little in the way of effective economic stimulus for it. Neil Irwin of the Upshot may say that "this is the fiscal stimulus the left has been asking for". That is false. He is totally wrong here: Paul Krugman: How Big a Bang for Trump���s Buck?: "I���m having a hard time figuring out exactly how big a stimulus we���re looking at...

...but it seems to be around 2 percent of GDP for fiscal 2019. With a multiplier of 0.5, that would add 1 percent to growth. That said, I���d suggest that this is a bit high. For one thing, it���s not clear how much impact corporate tax cuts, which are the biggest item, will really have on spending. Meanwhile, unemployment is only 4 percent; given Okun���s Law, the usual relationship between growth and changes in unemployment, an extra 1 percent growth would bring unemployment down to 3.5%, which is really low by historical standards, so that the Fed would probably lean especially hard against this stimulus. So we���re probably looking at adding less than 1 percent, maybe much less than 1 percent, to growth. This isn���t trivial, but it���s not that big a deal...

Live from Rant Central: Charlie Stross has had it with yo...

Live from Rant Central: Charlie Stross has had it with you people���those of you people who abandon worldbuilding and the exploration of possible human civilizations different from ours in the future direction for spectacle, and warmed over Napoleonic or WWII stories in fancy future dress: Charlie Stross: Why I barely read SF these days: "Storytelling is about humanity and its endless introspective quest to understand its own existence and meaning...

...Humans are social animals.... If we're going to write a fiction about people who live in circumstances other than our own, we need to understand our protagonists' social context.... Technology and environment inextricably dictate large parts of that context. You can't write a novel of contemporary life in the UK today without acknowledging that almost everybody is clutching a softly-glowing fondleslab that grants instant access to the sum total of human knowledge, provides an easy avenue for school bullies to get at their victims out-of-hours, tracks and quantifies their relationships (badly), and taunts them constantly with the prospect of the abolition of privacy in return for endless emotionally inappropriate cat videos. We're living in a world where invisible flying killer robots murder wedding parties in Kandahar, a billionaire is about to send a sports car out past Mars, and loneliness is a contagious epidemic. We live with constant low-level anxiety and trauma induced by our current media climate, tracking bizarre manufactured crises that distract and dismay us and keep us constantly emotionally off-balance. These things are the worms in the heart of the mainstream novel of the 21st century. You don't have to extract them and put them on public display, but if they aren't lurking in the implied spaces of your story your protagonists will strike a false note, alienated from the very society they are supposed to illuminate....

Now, what's my problem with contemporary science fiction? Simply put, plausible world-building in the twenty-first century is incredibly hard work.... A lot of authors seem to have responded to this by jettisoning consistency and abandoning any pretense at plausibility.... Plausible internal consistency is generally less of a priority than spectacle.... In Independence Day we see vast formations of F/A-18s (a supersonic jet) maneuvering as if they're Sopwith Camels.... Spectacle in place of insight, decolorized and pixellated by authors who haven't bothered to re-think their assumptions and instead simply cut and paste Lucas's cinematic vision....

Look back two centuries, to before the germ theory of disease brought vaccination and medical hygeine: about 50% of children died before reaching maturity and up to 10% of pregnancies ended in maternal death���childbearing killed a significant minority of women and consumed huge amounts of labour, just to maintain a stable population, at gigantic and horrible social cost. Energy economics depended on static power sources (windmills and water wheels: sails on boats), or on muscle power. To an English writer of the 18th century, these must have looked like inevitable constraints on the shape of any conceivable future���but they weren't....

SF should���in my view���be draining the ocean and trying to see at a glance which of the gasping, flopping creatures on the sea bed might be lungfish. But too much SF shrugs at the state of our seas and settles for draining the local aquarium, or even just the bathtub, instead. In pathological cases it settles for gazing into the depths of a brightly coloured computer-generated fishtank screensaver. If you're writing a story that posits giant all-embracing interstellar space corporations, or a space mafia, or space battleships, never mind universalizing contemporary norms of gender, race, and power hierarchies, let alone fashions in clothing as social class signifiers, or religions... then you need to think long and hard about whether you've mistaken your screensaver for the ocean. And I'm sick and tired of watching the goldfish.

Should-Read: When it is optimal not to experiment but ins...

Should-Read: When it is optimal not to experiment but instead to order (what you think is) the best thing on the menu? It is optimal surprisingly often���or so says the best job-market paper I have read this year; Xiaosheng Mu, Annie Liang, and Vasilis Syrgkanis: Dynamic Information Acquisition from Multiple Sources: "Decision-makers often aggregate information across many sources, each of which provides relevant information...

...We introduce a dynamic learning model where a decision-maker learns about unknown states by sequentially sampling from a finite set of Gaussian signals with arbitrary correlation. Such a setting describes sequential search between similar products, as well as reading news articles with correlated biases. We study the optimal sequence of information acquisitions. Assuming the final decision depends linearly on the states, we show that myopic signal acquisitions are nonetheless optimal at sufficiently late periods. For classes of informational environments that we describe, the myopic rule is optimal from period 1. These results hold independently of the decision problem and its (endogenous or exogenous) timing. We apply these results to characterize dynamic information acquisition in games...

Comment of the Day: Meno: Disruptive Technology and Educa...

Comment of the Day: Meno: Disruptive Technology and Education: "The main example of "disruptive" technology Rogoff gives in education is replacing live lectures with filmed ones. Quite obviously this is 1940s technology...

...Given that lectures weren't replaced by films in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980, 1990s, 2000s or 2010s, that suggests that the economic advantages to removing social contact with teachers from learning clearly aren't what Rogoff thinks they are...

Comment of the Day: Robert Waldmann: Fiscal Policy: "I th...

Comment of the Day: Robert Waldmann: Fiscal Policy: "I think that Jared Bernstein puts much too little emphasis on caveat 2b���the FOMC...

...He discusses the Fed's response to fiscal stimulus only as a minor aspect of possibly low multipliers. It is easy (easier) to argue that it will guarantee that the fiscal multiplier is zero.

Congress should make policy with the Fed it has not the Fed it wants. If the Fed is convinced the US is at full employment, it will not allow fiscal policy to push up output. If they are wrong, they will still make sure the fiscal multiplier is very small.

An argument for fiscal stimulus with the Fed we have, must be an argument that a higher nominal interest rate allows more room for conventional monetary stimulus if (and when) the next recession comes. Bernstein's argument is based on the assumption that tax cuts and spending increases cause higher output no matter how the monetary authority responds. He doesn't really believe this and shouldn't assume it...

Why Low Inflation in the Global North Should Be No Surprise

No Longer Fresh Over at Project Syndicate: Why Low Inflation in the Global North Should Be No Surprise: Late last summer the thoughtful and very sharp Nouriel Roubini used his space here at Project Syndicate to attribute the stubborn and, by many, unexpected persistence of low inflation in the Global North to "positive" (so-called, even though a number of them are on balance unwelcome) shocks to aggregate supply: Nouriel Roubini: The Mystery of the Missing Inflation:

The recent growth acceleration in the advanced economies would be expected to bring with it a pickup in inflation.... Yet core inflation has fallen.... Developed economies have been experiencing positive supply shocks.... The Fed has justified its decision to start normalizing rates... by arguing that the inflation-weakening supply-side shocks are temporary.... Central banks aren���t willing to give up on their formal 2% inflation target, [but] they are willing to prolong the timeline for achieving it...

This is, I believe, significantly more likely than not to be a faulty diagnosis. It is, I think, based on a fundamental misreading of the historical evidence from the 1970s through the 1990s about what has, historically since World War II, driven inflation in the countries of the Global North. The near-consensus belief since the 1970s has been and remains that the Phillips Curve has a substantial slope���a strong reaction of prices to demand pressure or slack���so that relatively small excursions of aggregate demand above levels consistent with full employment would have substantial impact on inflation, and that expectations of inflation are rapidly adaptive: easy de-anchored via a process in which accelerations of inflation in the recent past get rapidly and substantially incorporated into inflation expectations for the future.

More than twenty years ago I wrote an article, America's Peacetime Inflation: the 1970s challenging this standard near-consensus narrative as it had developed back then. The excursions of aggregate demand above levels consistent with full employment were few, short, and small. The incorporation of past inflation jumps into expectations of future inflation took place not rapidly but slowly. It took three large adverse supply shocks���the Yom Kippur War, the Iranian Revolution, and the 1970s productivity slowdown in the context of an economy in which unions still had substantial pricing power and previously-contracted wage increases. And even then more was required: hesitation on the part of central bankers, chiefly Arthur Burns, to commit to achieving price stability. Burns, rather, tended to (understandably) shrink from the consequence that focusing on price stability would bring deep recession, and to kick the can down the road in the hope that something would turn up. And so the stage was set for 1979, the Volcker Disinflation, and the Near-Great Recession of 1979-1982.

Yet, somehow, this actual history of what had happened was swallowed up by a peculiar and particular narrative. The narrative went and goes something like this:

Keynesian economists in the 1960s did not understand the natural rate of unemployment.

Hence they convinced central bankers and governments to run overly-expansionary policies that pushed aggregate demand above levels consistent with full employment.

And this sin against the Gods of the Market was followed by the natural retribution, in the form of high and persistent inflation.

This sin then had to be expunged by the sacrifice of the jobs and incomes of millions of workers via the Volcker Disinflation.

We must not allow economists and central bankers to commit this same sin of running overly expansionary policies again.

Why does this���not very true���story of what happened in the 1970s have such a hold on us? Why has it continued to have a hold even though it has been a bad guide to the economy since? Those relying on the 1970s and using their image of it to argue for imminent upward outbreaks of Global North inflation in the 1990s, 2000s, and now 2010s have all been wrong. The idea that the natural rate of unemployment was a stable parameter or, indeed, something that could be effectively estimated was also exploded by Staiger, Stock, and Watson more than twenty years ago. The belief that the Phillips Curve has a substantial slope did not survive Blanchard, Cerutti, and Summers. And the belief that the slope of the Phillips Curve was substantial even in the 1970s depends on one's averting one's eyes from the supply shocks of that decade, and thus attributing to demand events that are more plausibly attributed to supply.

Yet not the memory of what happened in the 1970s but rather the constructed image still has a powerful hold today. Why?

The best���although still inadequate, and highly, highly tentative���explanation of this that I have heard is that this story pattern fits with our cognitive biases. This story pattern is one we expect and like to hear. We appear to be pre-programmed at a deep level to seek for and resonate with stories of sin and retribution, crime and punishment, error and comeuppance. From whence this cognitive bias arises may launch many careers in psychology in the future. But we do not have to be prisoners of our heuristics and biases. And we should not be.

Donald Trump Is Playing to Lose: Live at Project Syndicate

Live at Project Syndicate: Donald Trump Is Playing to Lose: America certainly has a different kind of president than what it is used to. What distinguishes Donald Trump from his predecessors is not just his temperament and generalized ignorance, but also his approach to policymaking. Consider Bill Clinton, who in 1992 was, like Trump, elected without a majority of voters. Once in office, Clinton appealed to the left with fiscal-stimulus and health-care bills (both unsuccessful), but also tacked center with a pro-growth deficit-reduction bill. He appealed to the center right by concluding the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which had been conceived under his Republican predecessors; and by signing a major crime bill. And he reappointed the conservative stalwart Alan Greenspan to chair the US Federal Reserve. Clinton hoped to achieve three things with this ���triangulation��� strategy... READ MOAR at Project Syndicate

When Globalization is Public Enemy Number One: No Longer Fresh at the Milken Institute Review

*Milken Institute Review: When Globalization is Public Enemy Number One: The first 30 years after World War II saw the recovery and reintegration of the world economy (the ���Thirty Glorious Years,��� in the words of French economist Jean Fourasti��). Yet after a troubled decade ��� one in which oil shocks, inflation, near-depression and asset bubbles temporarily left us demoralized ��� the subsequent 23 years (1984-2007) of perky growth and stable prices were even more impressive as far as the growth of the world's median income were concerned.

This period, dubbed the ���Great Moderation,��� was by most economists��� reckoning largely the consequence of the process of knitting the world together. The mechanism (and impact) was largely economic. But the consequences of globalization were also felt in cultural and political terms, accelerating the tides of change that have roughly tripled global output and lifted more than a billion people from poverty since 1990.

So why is globalization now widely viewed as the tool of the sorcerer���s apprentice? I am somewhat flummoxed by the fact that a process playing such an important role in giving the world the best two-thirds of a century ever has fallen out of favor. But I believe that most of the answer can be laid out in three steps:

The past 40 years have not been bad years, but they have been disappointing ones for the working and middle classes of what we now call the ���Global North��� (northwestern Europe, America north of the Rio Grande and Japan).

There is a prima facie not implausible argument linking those disappointing outcomes for blue-collar workers to ongoing globalization.

*���In any complicated policy debate that becomes politicized, the side that blames foreigners has a very powerful edge. Politicians have a strong incentive to pin it on people other than themselves or those who voted for them. The media, including the more fact-based media, tend to let elected officials set the agenda.

Hence it doesn���t take much of a crystal ball to foresee a few decades of backlash to globalization in our future. More of what is made will probably be consumed at home rather than linked into global supply chains. Businesses, ideas and people seeking to cross borders will face more daunting barriers.

Some of the consequences are predictable. The losses to income created by cross-border barriers to competition will grow. And more of the focus of economic policy will be on the division of the proverbial pie rather than how to make it larger. Small groups of well-organized winners will take income away from diffuse and unorganized groups of losers.

Measured in absolute numbers, an awful lot of wealth will be lost. But those losses won���t approach, say, the scale of the output foregone in the Great Recession. Figure on a 3 percent reduction in income, equivalent to the loss of two years��� worth of growth in the advanced industrialized economies.

Most well-educated Americans, I suspect, will either be net beneficiaries of the reshuffling of income or won���t lose enough to notice. Disruption often redounds to the benefit of the sophisticated who can see it coming in time to get out of the way or turn it to their own advantage. But that���s a minority of the population, even in rich countries. Real fear about where next week���s mac and cheese is going to come from applies for a tenth, while fear about survival through the hard times is still a thing for a quarter of humanity.

Why do I believe all this? Bear with me, for my explanation demands an excursion down the long and winding road of centuries of globalization.

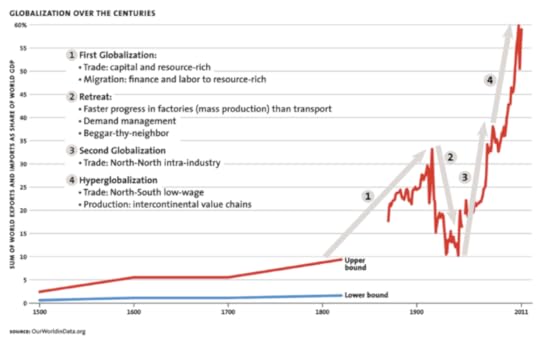

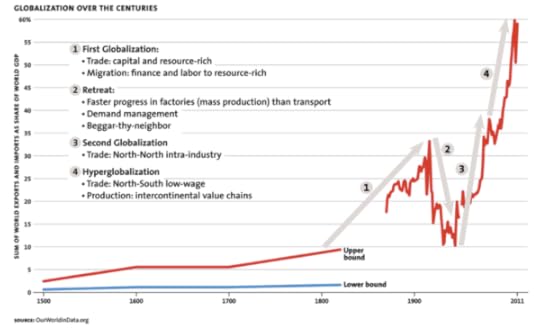

Globalization in Historical Perspective: On the brilliant date-visualization website, Our World in Data, Oxford researcher Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, along with site founder Max Roser, has plotted best estimates of the relative international ���trade intensity��� of the world economy ��� the sum of exports and imports divided by total output over a very long time. In my reproduction I have divided the years since 1800 into four periods and drawn beginning- to end-of-period arrows for each.

In the years from 1800 to 1914, which I call the First Globalization, world trade intensity tripled, driven mostly by exchange between capital-rich, labor-intensive and resource-rich regions. Countries with both sorts of endowments benefit by specializing production in their areas of comparative advantage. Meanwhile, huge migrations of (primarily) people and (secondarily) financial capital to resource-rich regions established a truly integrated global economy for the first time in history.

The period from 1914 to 1945 saw a dramatic retreat, with the relative intensity of international trade slipping back to little more than its level in 1800. There are multiple, complementary explanations for this setback. Faster progress in mass production than in long-distance transport made it efficient to bring production back home to where the demand was. The Great Depression created a path of least political resistance in which governments sought to save jobs at home at the expense of trading partners. And wars both blocked trade and made governments leery of an economic structure in which they had to rely on others.

This retrenchment, however, was reversed after World War II. The years 1945 to 1985 saw the Second Globalization, which carried trade intensity well above its previous high tide in the years before World War I. But this time, the bulk of trade growth was not among resource-rich, capital-rich and labor-intensive economies exchanging the goods that were their comparative advantage in production. It largely took place within the rich Global North, as industrialized countries developed communities of engineering expertise that gave them powerful comparative advantages in relatively narrow slices of manufacturing production in everything from machine tools (Germany) to consumer electronics (Japan) to commercial aircraft (the United States).

After 1985, however, there was a marked shift to what Ortiz-Ospina calls ���hyperglobalization.��� Multinational corporations began building their international value chains across crazy quilts of countries. The Global South���s low wages gave it an opportunity to bid for the business of running the assembly lines for products designed and engineered in the Global North. Complementing this value-chain-fueled boost to world trade came the other aspects of hyperglobalization: a global market in entertainment that created the beginnings of a shared popular culture; a wave of mass international migration and the extension of northern financial markets to the Global South, cutting the cost of capital and increasing its volatility even as it facilitated portfolio diversification across continents.

Hyperglobalization, Up Close and Personal: Of these value-chain-fueled boosts to international trade, perhaps the first example was the U.S.-Mexico division of labor in the automobile industry enabled by the North American Free Trade Agreement of the early 1990s. The benefits were joined to the more standard comparative-advantage-based benefits of reduced trade barriers. At the 2017 Milken Institute Global Conference, Alejandro Ram��rez Maga��a, the founder of Cin��polis, the giant Mexican theater group that is investing heavily in the United States, summed up the views of nearly all the economists and business analysts in attendance:

Between the U.S. and Mexico, trade has grown by more than six-fold since 1994 ��� 6 million U.S. jobs depend on trade with Mexico. Of course, Mexico has also enormously benefited from trade with the U.S.��� We are actually exporting very intelligently according to the relative comparative advantage of each country. Nafta has allowed us to strengthen the supply chains of North America, and strengthened the competitiveness of the region...

Focus on the reference to "supply chains". Back in 1992, my friends on both the political right and left feared���really feared���that Nafta would kill the U.S. auto industry. Assembly-line labor in Hermosillo, Mexico had such an enormous cost advantage over assembly-line labor in Detroit or even Nashville that the bulk of automobile manufacturing labor and value added was, they claimed, destined to move to Mexico. There would be, in the words of 1992 presidential candidate Ross Perot, ���a giant sucking sound,��� as factories, jobs and prosperity decamped for Mexico.

But that did not happen. Only the most labor-intensive portions of automobile assembly moved to Mexico. And by moving those segments, GM, Ford and Chrysler found themselves in much more competitive positions vis-a-vis Toyota, Honda, Volkswagen and the other global giants.

Fear of Globalization: Barry Eichengreen, my colleague in the economics department at Berkeley, wrote that there is unlikely to be a second retreat from globalization:

U.S. business is deeply invested in globalization and would push back hard against anything the Trump administration did that seriously jeopardized Nafta or globalization more broadly. And other parts of the world remain committed to openness, even if they are concerned about managing openness in a way that benefits everyone and limits stability risks that openness creates...

But I see another retreat as more likely than not. For one thing, anti-globalization forces have expanded to include the populist right as well as the more familiar populist left. It was no surprise when primary contender Bernie Sanders struck a chord by condemning Nafta and the opening of mass trade with China as ���the death blow for American manufacturing.��� But it was quite another matter when the leading Republican candidate (and now president) claimed that globalization would leave ���millions of our workers with nothing but poverty and heartache��� and that Nafta was ���the worst deal ever��� for the United States.

The line of argument is clear enough. Globalization, at least in its current form, has greatly expanded trade. This has decimated good (high-paying) jobs for blue-collar workers, which has led to a socioeconomic crisis for America���s lower-middle class. U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer buys this:

Nafta has fundamentally failed many, many Americans. ��� [Trump] is not interested in a mere tweaking of a few provisions and a couple of updated chapters. ��� We need to ensure that the huge [bilateral trade] deficits do not continue, and we have balance and reciprocity...

It���s conceivable that the Trump administration will yet pay homage to the post-World War II Republican Party���s devotion to open trade. But it seems unlikely in light of the resonance protectionism has had with Trump supporters. And if the Trump administration proves not to be a bellwether on globalization, it is surely a weathervane.

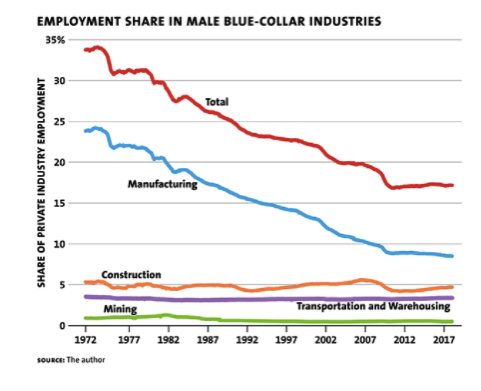

The Real Impact of Globalization: Portions of the case against globalization have some traction. It is, indeed, the case that the share of employment in the sectors we think of as typically male and typically blue-collar has been on a long downward trend. Manufacturing, construction, mining, transportation and warehousing constituted nearly one-half of nonfarm employment way back in 1947. By 1972, the fraction had slipped to one-third, and it is just one-sixth today.

But consider what the graph does not show: the decline (from about 45 percent to 30 percent) in the share of these jobs from 1947 to 1980 was proceeding at a good clip before U.S. manufacturing faced any threat from foreigners. And the subsequent fall to about 23 percent by the mid-1990s took place without any ���bad trade deals��� in the picture. The narrative that blames declining blue-collar job opportunities on globalization does not fit the timing of what looks like a steady process over nearly three-quarters of the last century.

Wait, there���s a second disconnect. Look at the way the declines in output divide among the sub-sectors (see page 29). Manufacturing was about 15 percent of nonfarm production in the mid-1990s and was still about 14 percent at the end of 2000, even as trade with Mexico and China accelerated into hyperdrive. Indeed, the bulk of the fall in ���men���s work��� has been in construction, which represented 7 percent of private industry production in 1997 and represents just 4 percent today. Warehousing and transportation have also taken a big hit in terms of proportion.

The biggest factors on the real production side over the past 20 years have not been the out-migration of manufacturing, but the depression of 2007-10 and the dysfunction of the construction finance market that continues to this day.

The China Shock: The case that the workings of globalization have had a major destructive effect on the employment opportunities of blue-collar men over the past two decades received a major intellectual boost from the research of David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson on the impact of the ���China shock.���

One of their bottom lines is that the loss of some 2.4 million American manufacturing jobs ���would have been averted without further increases in Chinese import competition after 1999.��� Moreover, the effects on workers and their communities were dislocating in a way in which manufacturing job loss generated by incremental improvements in productivity not associated with factory closings was not.

The China shock was very real and very large: its significance shouldn���t be discounted, especially in the context of a close presidential election whose outcome may have a large, enduring impact on the United States ��� and, for that matter, the world. But some perspective is needed if one is to allow the tale of the China shock to influence thinking about globalization.

Start with the fact that, in most ways, this is a familiar story in the American economy that long preceded the rise of China. Dislocation associated with the relocation of production facilities is more damaging to people and places than incremental changes in production processes, whether the movement is across state lines or across continents.

When my grandfather and his brothers closed down the Lord Bros. Tannery in Brockton, Massachusetts to reopen in lower-wage South Paris, Maine, the move was a disaster for the workers and the community of Brockton ��� and a major boost for South Paris. When, a decade and a half later, my grandfather found he could not make a go of it in South Paris and started a new business in Lakeland, Florida, it was the workers and the community of South Paris who suffered.

The fact that, in the case of globalization-driven dislocation, the jobs cross international borders adds some wrinkles, but not all of them are obvious. As demand shifts, jobs vanish for some in some locations and open for others in other locations. Dollars that in the past were spent purchasing manufactures from Wisconsin and Illinois and are now spent purchasing manufactured imports from China do not vanish from the circular flow of economic activity. The dollars received by the Chinese still exist and have value to their owners only when they are used to buy American-made goods and services.

Demand shifts, yes ��� but the dollars paid to Chinese manufacturing companies eventually reappear as financing for, say, new apartment buildings in California or to pay for a visit to a dude ranch in Montana or even to buy an American business that otherwise might close. GE, which had been openly seeking a way to offload its household appliance division for many years, sold the business to the Chinese firm Haier, the largest maker of appliances in the world. How different might the world have been for the employees of White-Westinghouse who were making appliances if a Chinese firm had been trolling the waters for an acquisition before the brand disappeared for good in 2006?

Only with the coming of the Great Recession do we see not blue-collar job churn but net blue-collar job loss in America. And that was due to the government���s failure to properly regulate finance to head off the housing meltdown, the subsequent failure to properly intervene in financial markets to prevent depression, and the still later failure to pursue policies to rapidly repair the damage.

All that said, the connection between the China shock in the 2000s and increasing blue-collar distress in the 2000s on its face lends some plausibility to the idea that globalization bears responsibility for most of their distress, and needs to be stopped.

The Globalization Balance Sheet: Last winter, in a piece for http://vox.com, I made my own rough assessment of the factors responsible for the 28 percentage point decline in the share of sectors primarily employing blue-collar men since 1947. I attributed just 0.1 percentage points to our ���trade deals,��� 0.3 points to changing patterns of trade in recent years (primarily the rise of China), 2 percentage points to the impact of dysfunctional fiscal and monetary policies on trade, and 4.5 percent to the recovery of the North Atlantic and Japanese economies from the devastation of World War II. I attributed the remaining 21 percentage points to labor-saving technological change.

This 21 percentage points has very little to do with globalization. Yes, with low barriers to trade, technology allows foreign exporters to make better stuff at lower cost. But American producers have the parallel option to sell them better stuff for less. And thanks to technology, consumers on both sides get more good stuff cheap. Economists slaving away in musty offices can invent scenarios in which technological change favors foreign producers over their American counterparts and thereby directly costs blue-collar jobs. But the assumptions needed to get that result are highly unrealistic.

To repeat, because it bears repeating: globalization in general and the rise of the Chinese export economy have cost some blue-collar jobs for Americans. But globalization has had only a minor impact on the long decline in the portion of the economy that makes use of high-paying blue-collar labor traditionally associated with men.

Why is this View so Hard to Sell?: Pascal Lamy, the former head of the World Trade Organization, likes to quote China���s sixth Buddhist patriarch: ���When the wise man points at the moon, the fool looks at the finger.��� Market capitalism, he says, is the moon. Globalization is the finger.

In a market economy, the only rights universally assured by law are property rights, and your property rights are only worth something if they give you control of resources (capital, land, etc.) ��� and not just any resources, but scarce resources that others are willing to pay for. Yet most people living in market economies believe their rights extend far beyond their property rights.

The way mid-20th century sociologist Karl Polanyi put it, people believe that they have rights to land whether they own the land or not ��� that the preservation and stability of their community is their right. People believe that they have rights to the fruits of labor ��� that if they work hard and play by the rules they should be able to reach the standard of living they expected. People believe that they have rights to a stable financial order ��� that their employers and jobs should not suddenly disappear because financial flows have been withdrawn at the behest of the sinister gnomes of Zurich or some other tribe of rootless cosmopolites.

Dealing with these hard to define, sometimes conflicting claims to rights beyond property is one of the major political-rhetorical-economic challenges of every society that is not stagnant. And blaming globalization for the unfulfilled claims of this group or that is a very handy way to pass the buck.

The good news is that, whatever the merits of the grievances of those who see themselves as losers in a globalizing economy, sensible public policy could go a long way to making them whole. Three keys would open the lock:

The failure of regional markets to sustain good jobs could be managed by much more aggressive social-insurance ��� unemployment, moving allowances, retraining and the like ��� along with the redistribution of government resources to create jobs where they have been lost.

More aggressive fiscal measures to keep job markets tight.

Karl Polanyi���s key remains at hand, too. While many Americans claim to worship at the altar of free markets, they still believe that they have all kinds of extra socioeconomic rights ��� to healthy communities, to stable occupations, to appropriate and rising incomes ��� that are not backed up by property rights. Governments could intervene on their behalf.

That way lies tyranny, we���ve been told, but also very high-functioning social democracies like Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands.

The bad news, of course, is that the public policies needed to soothe the grievances blamed on globalization seem further out of reach today than they were decades ago. Probably the best one can hope for is that the fever subsides sufficiently to allow for a realistic debate over who owes what to whom.

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers