J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 402

February 14, 2018

Should-Read: If the Federal Reserve's 2%/year PCE (2.5%/y...

Should-Read: If the Federal Reserve's 2%/year PCE (2.5%/year CPI) inflation target were appropriate, there would no be only a weak case for the proposition that the Federal Reserve is following an inappropriately tight monetary policy. Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve's current inflation target is not appropriate: the zero lower bound, and the Federal Reserve's limited power and willingness to do "what it takes" at the zero lower bound, means that a 2%/year PCE inflation target is almost surely inappropriately low. It runs enormous risks of prolonged, deep recession for no countervailing gain. Hence even with today's inflation number, I still say that there is a strong case for the proposition that the Federal Reserve is following an inappropriately tight monetary policy: Katia Dmitrieva: U.S. Consumer Prices Top Forecasts, Sending Markets Tumbling: "Core gauge advances 0.3% from prior month, above projections. Apparel index rises 1.7%, most in almost three decades...

...U.S. consumer prices rose by more than projected in January as apparel costs jumped the most in nearly three decades. The report sent Treasuries and stocks tumbling, as it added to concerns about an inflation pickup that have roiled financial markets this month. The consumer price index rose 0.5 percent from the previous month, above the median estimate of economists for a 0.3 percent increase, a Labor Department report showed Wednesday. Excluding volatile food and energy costs, the so-called core gauge increased 0.3 percent, also above forecasts for 0.2 percent. It was up 1.8 percent from a year earlier, higher than the 1.7 percent estimate. The yield on 10-year Treasuries rose to 2.86 percent, while U.S. stock futures fell, as the figures renewed investor concerns that the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates at a faster pace than anticipated...

Should-Read: Ian Morris (2013): The Measure of Civilizati...

Should-Read: Ian Morris (2013): The Measure of Civilization: How Social Development Decides the Fate of Nations (0691155682): "In the last thirty years, there have been fierce debates over how civilizations develop and why the West became so powerful...

...The Measure of Civilization presents a brand-new way of investigating these questions and provides new tools for assessing the long-term growth of societies. Using a groundbreaking numerical index of social development that compares societies in different times and places, award-winning author Ian Morris sets forth a sweeping examination of Eastern and Western development across 15,000 years since the end of the last ice age. He offers surprising conclusions about when and why the West came to dominate the world and fresh perspectives for thinking about the twenty-first century.

Adapting the United Nations' approach for measuring human development, Morris's index breaks social development into four traits--energy capture per capita, organization, information technology, and war-making capacity--and he uses archaeological, historical, and current government data to quantify patterns. Morris reveals that for 90 percent of the time since the last ice age, the world's most advanced region has been at the western end of Eurasia, but contrary to what many historians once believed, there were roughly 1,200 years--from about 550 to 1750 CE--when an East Asian region was more advanced. Only in the late eighteenth century CE, when northwest Europeans tapped into the energy trapped in fossil fuels, did the West leap ahead.

Resolving some of the biggest debates in global history, The Measure of Civilization puts forth innovative tools for determining past, present, and future economic and social trends.

February 13, 2018

Live from Tarantinoland: Jules Winnfield: Pulp Fiction: E...

Live from Tarantinoland: Jules Winnfield: Pulp Fiction: Ezekiel 25:17. "'The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the inequities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men...

...Blessed is he who, in the name of charity and good will, shepherds the weak through the valley of the darkness. For he is truly his brother's keeper and the finder of lost children. And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger those who attempt to poison and destroy my brothers. And you will know I am the Lord when I lay my vengeance upon you.

I been sayin' that shit for years. And if you ever heard it, it meant your ass. I never really questioned what it meant. I thought it was just a cold-blooded thing to say to a motherfucker before you popped a cap in his ass. But I saw some shit this mornin' made me think twice. Now I'm thinkin': it could mean you're the evil man. And I'm the righteous man. And Mr. .45 here, he's the shepherd protecting my righteous ass in the valley of darkness. Or it could be you're the righteous man and I'm the shepherd and it's the world that's evil and selfish. I'd like that. But that shit ain't the truth. The truth is you're the weak. And I'm the tyranny of evil men. But I'm tryin, Ringo. I'm tryin' real hard to be the shepherd...

Should-Read: Marta Lachowska, Alexandre Mas, Stephen Wood...

Should-Read: Marta Lachowska, Alexandre Mas, Stephen Woodbury: Sources of displaced workers��� long-term earnings losses: "We estimate the earnings losses of a cohort of workers displaced during the Great Recession...

...decompose those long-term losses into components attributable to fewer work hours and to reduced hourly wage rates. We also examine the extent to which the reduced earnings, work hours, and wages of these displaced workers can be attributed to factors specific to pre- and post-displacement employers; that is, to employer-specific fixed effects. The analysis is based on employer-employee linked panel data from Washington State assembled from 2002-2014 administrative wage and unemployment insurance (UI) records.

Three main findings emerge from the empirical work. First, five years after job loss, the earnings of these displaced workers were 16 percent less than those of comparison groups of nondisplaced workers. Second, earnings losses within a year of displacement can be explained almost entirely by lost work hours; however, five years after displacement, the relative earnings deficit of displaced workers can be attributed roughly 40 percent to reduced hourly wages and 60 percent to reduced work hours. Third, for the average displaced worker, lost employer-specific premiums account for about 11 percent of long-term earnings losses and nearly 25 percent of lower long-term hourly wages. For workers displaced from employers paying top-quintile earnings premiums (about 60 percent of the displaced workers in the sample), lost employer specific premiums account for more than half of long-term earnings losses and 83 percent of lower long-term hourly wages...

Live from the Orange-Haired Baboon Cage: Trump is meaner ...

Live from the Orange-Haired Baboon Cage: Trump is meaner in rhetoric than the orthodox Republicans, but not meaner than them in their lack of concern for the well-being of Americans: Jonathan Chait: Obama���s Gone, So Republicans Stopped Sabotaging the Economy: "During the Obama era, Democrats frequently believed, but only rarely uttered aloud in official forums, that the Republican Party was engaged in economic sabotage...

...Now that Republicans have reversed their position once again, also in a way that happens to redound to their political benefit, the answer seems a little more clear. Republicans have used their control of government to virtually double the budget deficit, which had been hovering around half a trillion dollars per year, and will now likely run well over $1 trillion���during the peak of an economic expansion. There is no economic rationale for this behavior. Their policy is simply to support fiscal contraction under Democratic presidents and fiscal expansion under Republican ones. Cynicism is the only basis to explain their behavior.

During the Bush administration, the party followed Dick Cheney���s famous dictum, ���Reagan proved deficits don���t matter,��� as a basic guide. Republicans financed two large tax cuts, a Medicare prescription-drug benefit, two wars, and a large domestic-security hike entirely through higher borrowing. Importantly, in addition to supporting permanent deficit increases, they also supported temporary deficit increases in order to ward off recessions....

When the economy entered another recession at the end of Bush���s second term, Republicans again overwhelmingly supported another temporary stimulus bill.... ���This is the Senate at its finest, recognizing this was an opportunity to demonstrate to the public that we could come together, do something important for the country and do it quickly,��� said a satisfied Mitch McConnell.... By 2009, the economy was plunging into the deepest crisis since the Great Depression. But at that point, which also coincided with partisan control of the presidency changing hands, Republicans decided they no longer agreed with Keynesian economics.... So thoroughly and so rapidly did this conversion permeate the Republican Party that, by the time Obama took office, it was almost impossible to find a conservative of any sort who had a kind word for the stimulus....

Once a Republican held the White House, Republicans simply abandoned the whole idea that sequestration, or anything at all, needed to be paid for. They have happily reverted to the Bush-era practice of putting everything on the national credit card.... Supporting fiscal stimulus now with unemployment close to 4 percent while opposing it when unemployment was far higher is a position no economist in the world would justify....

Whether this represents a conscious strategy of economic sabotage is not exactly an answerable question. The human brain is very good at concocting rationales for our self-interest. Republicans found reason to be receptive to arguments for Keynesianism under Bush, to reject them under Obama, and then to forget their old position under Trump...

Comment of the Day: RW: Disrupting Education: "'Will we e...

Comment of the Day: RW: Disrupting Education: "'Will we ever create tech (even for a few subjects) that will work as well as good one-on-one tutoring?'...

...That already has been done in a limited, skill-building way; e.g., Kahn Academy as noted in the root ms of this thread. But teaching is more complicated than that; e.g., developing the abilities of groups of students who are not your own children or even your own tribe introduces wrinkles even before you get the question of what kinds of abilities the students might consider most valuable. Tech can't be about teaching (yet) and if it is to be about tutoring at more complex levels it needs to emphasize tech's strengths rather than attempting to emulate teachers; i.e., what computers do best is exhaustive data traversal and rules-based analysis.

NB: Years ago I had a discussion with some folks developing a biochemistry program at UCLA that involved tracking each student's steps in solving a problem set and generated a report showing the path each student took. This was not constrained to achieving the correct answer or even just the number of steps it took. The program conducted a path analysis and one of the report elements was how 'splayed' the path appeared; that is, did the path reveal a tighter pattern suggestive of conceptual understanding or did it suggest the student was following leads in unprofitable directions, not intuitively sure of where the answer might lie. Not sure where that program wound up but it seemed like the right idea to me: let the computer do what it does best then let the teacher do what they do best.

"In the last analysis, we must come to the inevitable conclusion that education can be imparted only by a teacher and not wholly by a method ... Just as a water tank can be filled only with water and fire can be kindled with fire, life can be inspired with life ... However it may be, we want a human being in every sphere of our life. The mere pill of a method instead shall not bring us salvation." ���Rabindranath Tagore

Should-Read: Max's Our World in Data is a highly cool inf...

Should-Read: Max's Our World in Data is a highly cool information source: Max Roser: Economist: "What I���ve been up to during the last year...

...I haven���t written much on this blog recently and so I thought it might make sense to just list���and link to���a couple of the projects that I���ve been working on during the last year.... What kept me busy mostly was the work on Our World in Data, the free online publication on global development that I started some years ago. Unfortunately quite a lot of time I spent on the search for funding. But there were also a lot of very positive developments! The publication grew quite a bit���we now have 87 entries on Our World in Data! You find them all listed on the landing page. Two of my favorite recent entries are: (1) The very long and quite detailed entry on global extreme poverty that Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and I wrote; (2) The still growing entry on yields and land use in agriculture that Hannah Ritchie and I are still working on. Jaiden Mispy, the web developer in our team, keeps making our own open source data visualization tool���the Our World in Data Grapher���more and more useful. Aibek Aldabergenov, our database developer, made it possible to access large development datasets directly (without uploading them manually) and that made the work of the authors much faster and more fun. And while I wasn���t active here on my personal blog, we actually now publish very regularly on the OWID-blog...

Max Roser: About: Our World in Data: "Our World in Data is an online publication that shows how living conditions are changing...

...The aim is to give a global overview and to show changes over the very long run, so that we can see where we are coming from and where we are today. We need to understand why living conditions improved so that we can seek more of what works. We cover a wide range of topics across many academic disciplines: Trends in health, food provision, the growth and distribution of incomes, violence, rights, wars, culture, energy use, education, and environmental changes are empirically analyzed and visualized in this web publication. For each topic the quality of the data is discussed and, by pointing the visitor to the sources, this website is also a database of databases. Covering all of these aspects in one resource makes it possible to understand how the observed long-run trends are interlinked. The project, produced at the��University of Oxford, is made available in its entirety as a public good. Visualizations are licensed under CC BY-SA and may be freely adapted for any purpose. Data is available for download in CSV format. Code we write is open-sourced under the MIT license...

Should-Read: Our fearless leader Heather Boushey has a pi...

Should-Read: Our fearless leader Heather Boushey has a piece in the New Republic on why there are so many fewer female economists in America than one would expect. The thing that strikes me most comes from following Heather's link to Bayer and Rouse: "gender-neutral policies to stop the tenure clock for new parents substantially reduce female tenure rates while substantially increasing male tenure rates..." A man who has a kid and stops the tenure clock for a year has many sleepless nights and has an extra year to polish journal submissions. A woman has those, and also has nine months growing a human being inside of her and three years eating for two. The two experiences are simply not analogous. Treating them as if they are is anti-female discrimination���in effect, if not in intent: Heather Boushey: Gaps in the Market: "it���s not about the math. Women account for more than 40 percent of undergraduate math majors...

...At this year���s annual economics conference, a number of scholars presented papers examining why there are so few women in economics and what we can do about it. A recent working paper by the University of North Carolina���s Anusha Chari and Paul Goldsmith-Pinkham of the New York Federal Reserve even found that the overall share of women participating in a prestigious annual economics conference hasn���t improved in over 15 years. But the profession has been slow to deliver real fixes. One reason for this may be that economists are predisposed to believe discrimination is nonsensical. Standard economic theory tells us that firms���and people���who favor one group over another irrespective of their productivity will be driven out by market competition....

Because the process is so market-driven, the question that economists need to ask is whether gender and racial bias in the profession indicates something more troubling about economics itself.... If the market for economists isn���t efficient, what market is? Amanda Bayer and Cecilia Elena Rouse tackled this issue in their 2016 article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives. They argue that ���the social science discipline of economics will be strengthened if it is built on a broader segment of the population,��� and outline steps the profession could take to address the problem. Some of these are simple, such as changing the way we teach undergraduate economics, and some will require more work, such as providing better early career support and breaking down implicit bias in the profession.... For any profession���but particularly for an academic discipline that describes itself as scientific���to reject its own core findings is stupid at best, deeply hypocritical at worst. This is the profession that established the fact that labor-market discrimination contributes to lower productivity, lower economic growth, and lower wage growth. Of all people, economists cannot fail to address discrimination in our own ranks...

Noise Trading, Bubbles, and Excess Stock Market Volatility: Hoisted from the Archives from 2013

Noise Trading, Bubbles, and Excess Stock Market Volatility: Hoisted from the Archives from 2013: Noah Smith has a very nice post this morning:

Noah Smith: Risk premia or behavioral craziness?:

John Cochrane is quite critical of Robert Shiller.... He... thinks that Shiller is trying to make finance less quantitative and more literary (I somehow doubt this, given that Shiller is first and foremost an econometrician, and not that literary of a guy).

But the most interesting criticism is about Shiller's interpretation of his own work. Shiller showed... stock prices mean-revert. He interprets this as meaning that the market is inefficient and irrational... "behavioral craziness". But others--such as Gene Fama--interpret long-run predictability as being due to predictable, slow swings in risk premia.

Who is right? As Cochrane astutely notes, we can't tell who is right just by looking at the markets themselves. We have to have some other kind of corroborating evidence. If it's behavioral craziness, then we should be able to observe evidence of the craziness elsewhere in the world. If it's predictably varying risk premia, then we should be able to measure risk premia using some independent data source...

Let's back up to do some explaining...

When economists think about the prices rational people are willing to pay for financial security, they assume that people ask themselves six questions:

What is the expected future value of the security--what would be the case if I were neither lucky nor unlucky in this investment?

By how much should I discount that future value because I expect to be richer in the future than I am now, and so value extra purchasing power now more than extra purchasing power in the future?

Suppose I were lucky in this investment: how much more would I make than if things were neutral?

Suppose I were unlucky in this investment: how much would I lose relative to if things were neutral?

If I were lucky I would be richer, and so the things I buy with my money won't be as urgent: how much would I value the extra money if I am lucky taking account of the fact that I would be richer, and so how much should I elevate my willingness to pay above what I calculated in (2)?

If I were unlucky I would be poorer, and so the things I would have bought with the money I won't have would be more urgent: how much would I miss the money I lose if I am unlucky, taking account of the fact that I would be poorer, and so how much should I depress my willingness to pay below what I calculated in (5)?

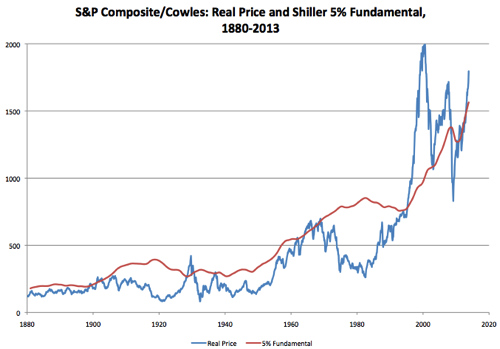

Now look at the stock market since 1880:

The blue line is the inflation-adjusted value of a representative basket of stocks--or equity claims to the assets and future profits of America's companies.

The red line is what you would be willing to pay for a basket of stocks if your answers to (2) through (6) made you willing to pay 20 times the fundamental earning power of the companies whose stocks you are buying, and if you calculated that fundamental earning power by simply taking a ten-year lagged moving average of the earnings that the companies report. It is thus a crude and simple-minded measure of "fundamentals"--ignoring variations in the amount of upside (3) and downside risks (4), ignoring variations in willingness to pay (5) for a given amount of upside and desire to insure (6) against a given amount of downside risk, and ignoring variations in the slope of the intertemporal price system (2).

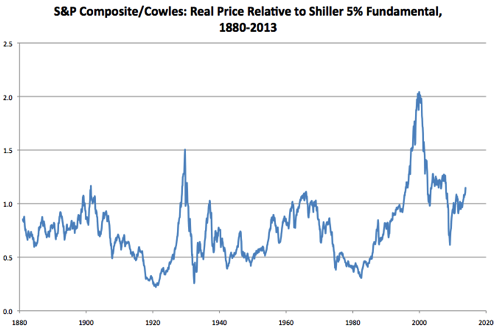

The variations of the price at which the stock market sells around this crude and simple-minded measure of fundamentals are enormous:

Sometimes (i.e., 1900) the stock market as a whole can be selling for 15% above its Shiller fundamental and then four years later be selling for 30% below. Sometimes (i.e., 1920) the market can be selling for 70% below its Shiller fundamental and then nine years later be selling for 50% above. Sometimes (i.e., 1996) the market can be selling at its Shiller fundamental and then four years later be selling for 100% above and three years after that be back at the fundamental again.

(A) Do these big swings relative to the crude Shiller fundamental primarily occur because the crude Shiller fundamental is a lousy proxy--because the market knows more and better about the profitability of American companies then simply taking a ten-year trailing average of earnings, rebasing it to the present, and capitalizing it at 5%?

No.

I am not aware of any serious economist today who thinks it more likely than not--or even possible--that the big swings of the market around the crude Shiller fundamental occur because the market knows more about the current earnings power of operating companies.

(B) Do these big swings relative to the crude Shiller fundamental primarily occur because technological progress speeds up and slows down, hence we alternately expect to be richer and poorer in the future, and thus the discount factor (2) we apply varies? Or, conversely, because as technological progress speeds up and slows down we mark our expectations of future values in (1) up and down?

No.

For one thing, these two effects nearly offset each other in general equilibrium: situations in which we mark up expected future values are situations in which we expect to be rich and so mark down the marginal value of wealth in the future. For another, news about the importance of technological revolutions arrives slowly and continuously over decades--it doesn't look at all like the changes in the market relative to the crude Shiller fundamental.

I am not aware of any serious economist today who thinks it more likely than not--or even possible--that the big swings of the market around the crude Shiller fundamental occur because the market is changing its assessment of future earnings growth or of the slope of the intertemporal price system.

(C) Do these big swings relative to the crude Shiller fundamental primarily occur because the market gets it wrong? The market is a voting mechanism that aggregates and averages the wealth-weighted views of the current crop of active traders. As the lucky double-down and the unlucky vanish and as the herd of investors are buffeted by fads and fashions, they buy and sell and push prices up and down, and the little bit of sober long-horizon smart money in the market is unable to do much to damp the irrational bull-market bubble of the late 1920s and the late 1990s or the bear bubble of the 1970s.

This is Bob Shiller's view. This is my view. This is Andrei and Jeremy's view. This is, I think, Noah's view--but as an untenured junior faculty member who will someday need a broad spectrum of supporting outside letters, he is... diplomatic. Note the role of "astutely" in the paragraph I quoted from Noah above...

(D) Do these big swings relative to the crude Shiller fundamental primarily occur because of changes in upside and downside risk (3) and (4)? This is the fearfully intelligent Robert Barro's and T.A. Reitz's view. I, at least, think his model is simply wrong: model doesn't fit the data very well, and it requires that there be no safe assets in the economy to drive the conclusion that the average price of safe bonds relative to risky equities. But the discussion is ongoing, and it is definitely a possibility: some at least of the 1933, 1975, and 2008-9 troughs in the market were due to a sudden increase in the perceived risk that things would go to hell in a hand basket.

(E) Do these big swings relative to the crude Shiller fundamental primarily occur because of shifts in (5) and (6), because of "time varying risk premia"--that sometimes the marginal utility of wealth of everyone's utility is constant and so people are indifferent between a lifetime income of $2,000,000 with certainty and a 1/3 chance of getting a lifetime income of $4,000,000 accompanied by a 2/3 chance of getting only $1,000,000; and sometimes the marginal utility of wealth is steeply curved so that people really, strongly prefer the first; and preferences are so unstable that society's preferences as a whole rapidly shift from one state to another in a matter of little more than months.

Now when Gene Fama and John Cochrane and company back in the 1980s raised this as their interpretation of Bob Shiller, I at first thought really did think it was a joke--my genuine reaction was "you're putting me on".

The curvature of any individual's utility function--how close any individual is to material satiation given current technological possibilities--is a deep psychological parameter that would require a radical rewiring of the brain to accomplish. Yet Fama, Cochrane, and company propose that such rewirings took place between 1996 and 2000, and that the rewirings were then unrewired between 2000 and 2002? Even if some individual has a Damascus moment and decides that while they value all of their current wealth greatly they would value extra wealth not at all--the kind of thing you need to have happen in order to account for the 2000-2002 movements in the stock market--that is just one individual. Fama, Cochrane, and company require that these complete neural rewirings happen to nearly everybody in the entire economy, because in a rational financial market risk is carried by those who are the least risk-averse--who are least subject to sudden satiation--and if one person's brain becomes rewired somebody else who was almost as far from satiation will take up the slack.

Let's go back to Noah:

Personally I suspect that it's behavioral spazzing....

Experimental asset markets exhibit highly predictable and significant spazzing that looks suspiciously like real-world "bubble" episodes....

Robin Greenwood and Andrei Shleifer... collate six different data sets that ask investors about their expectations of stock returns. The six series are highly correlated, meaning that they are really capturing some general phenomenon in the market. The stated expectations all seem to be "extrapolative", meaning that when returns have been good recently, people think they will continue to be good. But the stated expectations are usually wrong; when people think returns will be high, returns tend to fall soon after. What's more, that fall could be predicted by a simple asset pricing model. In other words, these stated expectations are not rational expectations. So if these stated expectations really do represent investors' beliefs, then we have direct evidence of behavioral spazzing...

Here I become very uneasy with the state of dialogue. Noah writes "So if these stated expectations really do represent investors' beliefs..." How could they not? Is Noah saying that people are misleading Andrei and Jeremy? No. He is saying that perhaps people do not actually believe what they think they believe--or, rather, that when economists talk about how somebody has a "belief" they are not referring to what people actually believe but to something else that is not a belief but that economists find convenient to say is a belief or to call a belief. This way, it seems to me, lies madness.

Noah explicates:

Cochrane has suggested that people responding to these surveys are not reporting their true beliefs, but rather their "risk-neutral probabilities".... If that's true, then these surveys wouldn't be good evidence of behavioral spazzing. So the issue has not been decided yet...

Now when I taught and when I discuss finance with the graduate students both in the Econ Department and at the Haas Business School, I find as a rule that only one in five or so is actually able to understand and use risk-neutral probability measures to analyze a situation. (This may be because "risk-neutral probabilities" may be the worst-named concept in economics: they are not probabilities, and they are definitely not risk-neutral.) To claim that we should model investors' thought processes and claim that they are rational utility-maximizers using concepts that most people with graduate training in finance do not understand seems... silly.

Noah continues:

But progress has been made. In my opinion, the available evidence is suggestive of the "behavioral spazzing" explanation, but not conclusive. The important thing is that this is not one of those "this will never be resolved" sorts of debates. This is a debate that can and will be resolved, as better and better data becomes available. Science progresses.

But let me be skeptical. Let's replay the debate:

Shiller shows up with evidence showing extraordinary excess volatility in the stock market relative to fundamentals. Fama and company claim that he has committed gross econometric errors and that his work is useless.

Shiller and others bound the biases and find that, yes, there is still extraordinary excess volatility in the aggregate market. Poterba and Summers and Fama and French and others confirm Shiller's statistics. Fama and company, however, say that it is not evidence of bubbles or noise-trading or irrational herding, but, rather, of "time-varying risk premia".

Fama and company present no evidence of the kinds of rapid neural rewiring of the entire population to shift the shape of declining marginal utility of wealth that would be needed to drive such time-varying risk premia, but rather seize the high ground of the null hypothesis for themselves.

Micro studies show that small toy financial markets where students can trivially and easily solve for fundamental values nevertheless exhibit lots of noise trading of various forms. Fama and company ignore it.

Shiller, Greenwood and Shleifer, Case and Quigley, many others show up with an increasing body of evidence that, yes, it is people's beliefs about future market prices that are irrational, extrapolative, and drivers of excess volatility. Fama and Cochrane and company say now that people's "beliefs" do not bear any relationship to what people say they believe and actually do believe.

More important: the excess volatility/return predictability we see in episodes like 1996-2000, 2000-2002, 2007-2009, 2009-2013, 1920-1929, 1900-1904, and so forth has a half-life of ten years. That means that in Fama and Campbell's schema that in 2000--when the market price was twice its 5% Shiller fundamental--the expected one-year real return on the market was the 5% fundamental return minus a 10% "mean reversion of risk premia back to their norm" term. I don't care how far from satiation your marginal utility of wealth is: nobody rational should have been holding their pro-rata share of equities in 2000, and to claim that the people doing so had simply decided that they were less risk-averse than normal is... something that leads words to fail me...

So I look at the situation, and I have to judge that those who explain aggregate stock market deviations from the crude Shiller fundamental as driven by rational agents' revising their views of the curvature of their utility functions are people--some of them very smart indeed, some of them not smart at all--who are themselves in an irrational intellectual bubble. They really do appear to me to be people who ought to have been persuaded by Shiller a generation ago. They were not. And so now they are are turning their smarts to constructing reasons to justify their not having been persuaded.

And, in so doing, I think that they are not acting very intelligently.

Thus I am less optimistic than Noah about how, or whether, this thing will be settled in my lifetime. We have already progressed to the stage of "people's beliefs are not what they believe". Where will we go next? I do not know. But I do not expect to see intellectual convergence to what I think is the justified true belief: that Bob Shiller is right.

Should-Read: Starting from a competitive benchmark and as...

Should-Read: Starting from a competitive benchmark and assuming one market failure is not enough to fit anything anymore. Oleg and Dmitry have three, if I can count: Oleg Itskhoki and Dmitry Mukhin: Exchange Rate Disconnect in General Eqilibrium: "We propose a dynamic general equilibrium model of exchange rate determination...

...which simultaneously accounts for all major puzzles associated with nominal and real exchange rates. This includes the Meese-Rogo disconnect puzzle, the PPP puzzle, the terms-of-trade puzzle, the Backus- Smith puzzle, and the UIP puzzle.

The model has two main building blocks���the driving force (or the exogenous shock process) and the transmission mechanism���both crucial for the quantitative success of the model. The transmission mechanism���which relies on strategic complementarities in price setting, weak substitutability between domestic and foreign goods, and home bias in consumption���is tightly disciplined by the micro-level empirical estimates in the recent international macroeconomics literature. The driving force is an exogenous small but persistent shock to international asset demand, which we prove is the only type of shock that can generate the exchange rate disconnect properties. We then show that a model with this financial shock alone is quantitatively consistent with the moments describing the dynamic comovement between exchange rates and macro variables. Nominal rigidities improve on the margin the quantitative performance of the model, but are not necessary for exchange rate disconnect, as the driving force does not rely on the monetary shocks. We extend the analysis to multiple shocks and an explicit model of the nancial sector to address the additional Mussa puzzle and Engel���s risk premium puzzle...

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers