J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 398

February 26, 2018

Should-Read: I could not enthusiastically support���I cou...

Should-Read: I could not enthusiastically support���I could barely support���the old TPP: it charged poor countries too much through the nose to use U.S.-located intellectual property, for little if not negative benefit to the median U.S. citizen and for substantial harm to world economic growth. This new CPTPP is significantly better, and I can enthusiastically endorse the U.S.'s joining it on its present terms: Zachary Torrey: TPP 2.0: The Deal Without the US: "What���s new about the CPTPP and what do the changes mean?...

...The new Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) is still a powerful pact in its own right... includes all the original members of the TPP except the United States: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam. The total combined gross domestic product of the CPTPP would be $13.5 trillion or 13.4��percent of global GDP... one of the biggest trade agreements in the world.... When Trump withdrew from the TPP he also withdrew two of the most controversial provisions for which the United States had been advocating. One of the most ridiculed provisions in the TPP, the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) provision, has been scaled back while a government���s right to regulate its markets has been afforded increased protections. This was only possible after the United States withdrew.... Another key provision the United States pushed for that has fallen to the side is the extension of copyright, or intellectual property, protections.��Washington had negotiated��for copyright to exist for��the author���s lifetime plus an additional 70 years.... The removal of these two provisions highlights what happens when��the United States is not involved in regional affairs: the region moves on without it....

Washington could rejoin the agreement.... Far from being dead, the CPTPP perhaps signals a new chapter in global trade, one without the United States...

Should-Read: I had thought that the Chinese bureaucracy u...

Should-Read: I had thought that the Chinese bureaucracy understood in its bones the Five Good Emperors problem���that after Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius there came Commodus���as sufficient reason never to allow the restoration of lifetime tenures or single-dominant-politican practices. It looks like I was wrong: Willy Lam: China Paves Way For Xi Jinping To Extend Rule Beyond 2 Terms: "'Xi Jinping has finally achieved his ultimate goal when he first embarked on Chinese politics...

...that is to be the Mao Zedong of the 21st century,��� said Willy Lam, a political analyst at the Chinese University in Hong Kong.... Last year... his name and a political theory attributed to him were added to the party constitution as he was given a second five-year term as general secretary. It was the latest move by the party signaling Xi���s willingness to break with tradition and centralize power.... ���What is happening is potentially very dangerous because the reason why Mao Zedong made one mistake after another was because China at the time was a one-man show,��� Lam said. ���For Xi Jinping, whatever he says is the law. There are no longer any checks and balances.��� Xi is coming to the end of his first five-year term as president and is set to be appointed to his second term at an annual meeting of the rubber-stamp parliament that starts March 5. The proposal to end term limits will likely be approved at that meeting. Term limits on officeholders have been in place since they were included in the 1982 constitution, when lifetime tenure was abolished...

February 25, 2018

Live from the State with the Extremely Strong Democratic ...

Live from the State with the Extremely Strong Democratic Bench: Alexei Koseff: Feinstein denied Democratic endorsement in CA Senate race: "Delegates at the California Democratic Party convention... the veteran lawmaker... received only 37 percent...

...Her principal challenger, state Senate leader Kevin de Le��n, received 54 percent of the vote, just short of the 60 percent threshold to capture the Democratic endorsement.... After announcing his candidacy in mid-October, de Le��n raised about $500,000 by the end of the year. Feinstein raised double that amount during the same period and kicked in $5 million of her own money, giving her nearly $10 million on hand at the start of 2018. A poll released earlier this month by the Public Policy Institute of California found Feinstein leading among likely voters by nearly 30 points���46 percent to 17 percent���while nearly two-thirds of respondents had never heard of de Le��n or didn���t know enough about him to form an opinion..... The convention delegates reflect only a highly-involved slice of the party.

No endorsements were handed out in several other hotly contested races, including for governor, where four Democratic candidates vied for delegates��� support. Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom led the vote with 39 percent, followed by Treasurer John Chiang with 30 percent, former Superintendent of Public Instruction Delaine Eastin with 20 percent, and former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa with 9 percent.

Should-Read: Steven K. Vogel: Marketcraft: How Government...

Should-Read: Steven K. Vogel: Marketcraft: How Governments Make Markets Work (019069985X): "Modern-day markets do not arise spontaneously or evolve naturally...

...Rather they are crafted by individuals, firms, and most of all, by governments. Thus "marketcraft" represents a core function of government comparable to statecraft and requires considerable artistry to govern markets effectively. Just as real-world statecraft can be masterful or muddled, so it is with marketcraft. In Marketcraft, Steven Vogel builds his argument upon the recognition that all markets are crafted then systematically explores the implications for analysis and policy. In modern societies, there is no such thing as a free market. Markets are institutions, and contemporary markets are all heavily regulated. The "free market revolution" that began in the 1980s did not see a deregulation of markets, but rather a re-regulation. Vogel looks at a wide range of policy issues to support this concept, focusing in particular on the US and Japan. He examines how the US, the "freest" market economy, is actually among the most heavily regulated advanced economies, while Japan's effort to liberalize its economy counterintuitively expanded the government's role in practice.

Marketcraft demonstrates that market institutions need government to function, and in increasingly complex economies, governance itself must feature equally complex policy tools if it is to meet the task. In our era-and despite what anti-government ideologues contend-governmental officials, regardless of party affiliation, should be trained in marketcraft just as much as in statecraft...

books

Should-Read: Once again: I believe this fundamentally mis...

Should-Read: Once again: I believe this fundamentally misconceives the origins and the utility of New Keynesian models. There are things that they are good for. But there are things that they are not good for. Getting a sensitivity of aggregate demand to the real interest rate via an Euler equation is not a good thing. Calvo pricing is not a good thing. Technology shocks as putting the residual from a production function on the right hand side and claiming it as a primitive shock is not a good thing. And what else is there in a New Keynesian model? A money demand function (or an interest rate rule). That is not very much that is useful. The things that make New Keynesian models different from VARs are, pretty much, things that make them less accurate and valuable. Do a VAR. And then argue about what the underlying shocks behind the VAR shocks really are, and how the VAR impulse response coefficients constrain the underlying structural shock ones: David Vines and Samuel Wills: rebuilding macroeconomic theory project: an analytical assessment: "We asked a number of leading macroeconomists to describe how the benchmark New Keynesian model might be rebuilt...

...The need to change macroeconomic theory is similar to the situation in the 1930s, at the time of the Great Depression, and in the 1970s, when inflationary pressures were unsustainable. Four main changes to the core model are recommended: to emphasize financial frictions, to place a limit on the operation of rational expectations, to include heterogeneous agents, and to devise more appropriate microfoundations. Achieving these objectives requires changes to all of the behavioural equations in the model governing consumption, investment, and price setting, and also the insertion of a wedge between the interest rate set by policy-makers and that facing consumers and investors. In our view, the result will not be a paradigm shift, but an evolution towards a more pluralist discipline...

February 24, 2018

Keynes's General Theory Contains Oddly Few Mentions of "Fiscal Policy"

Something that has puzzled me for quite a while: Keynes's General Theory contains remarkably few references to fiscal policy in any form:

"Government spending": no matches...

"Government purchases": no matches...

"Fiscal policy": 6 matches:

Four in one paragraph about how fiscal policy is the fifth in an enumerated list of factors affecting the marginal propensity to consume...

One about how an estate tax changes the marginal propensity to consume...

One about how fiscal policy in ordinary times is "not likely to be important"...

"Public works": 10 matches:

Three in a paragraph about how the multiplier amplifies the employment effect from public works...

Two in a paragraph warning that multiplier calculations are overoptimistic because of import, interest rate, and confidence crowding-out...

Four on how public works have a much bigger effect when unemployment is high and "public works even of doubtful utility may pay for themselves..."

One a criticism of Pigou's logic...

And yet it also contains this one paragraph:

In some other respects the foregoing theory is moderately conservative in its implications. For whilst it indicates the vital importance of establishing certain central controls in matters which are now left in the main to individual initiative, there are wide fields of activity which are unaffected. The State will have to exercise a guiding influence on the propensity to consume partly through its scheme of taxation, partly by fixing the rate of interest, and partly, perhaps, in other ways. Furthermore, it seems unlikely that the influence of banking policy on the rate of interest will be sufficient by itself to determine an optimum rate of investment. I conceive, therefore, that a somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment; though this need not exclude all manner of compromises and of devices by which public authority will co-operate with private initiative...

Chasing back this "banking policy" that is the alternative to the "somewhat comprehensive socialization of investment", there are three cites to "banking policy": this paragraph is one, and the others are:

"to every banking policy there corresponds a different long-period level of employment..."

and the "it is, I think, arguable that a more advantageous average state of expectation might result from a banking policy which always nipped in the bud an incipient boom by a rate of interest high enough to deter even the most misguided optimists. The disappointment of expectation, characteristic of the slump, may lead to so much loss and waste that the average level of useful investment might be higher if a deterrent is applied.... [But] the austere view, which would employ a high rate of interest to check at once any tendency in the level of employment to rise appreciably above the average of; say, the previous decade, is, however, more usually supported by arguments which have no foundation at all apart from confusion of mind..."

The question of why "it seems unlikely that the influence of banking policy on the rate of interest will be sufficient by itself... a somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment..." is left hanging. And how "a somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment" is to be implemented are left hanging as well.

So will somebody please explain to me why "fiscal policy" plays such a small part in the General Theory and yet such a large part in mindshare perceptions of "Keynesianism"?

(Early) Monday Smackdown/Hoisted from the Archives: Thinking Math Can Substitute for Economics Turns Economists Into Real Morons Department

The highly estimable Tim Taylor wrote:

Tim Taylor: Some Thoughts About Economic Exposition in Math and Words: "[Paul Romer's] notion that math is 'both more precise and more opaque' than words is an insight worth keeping..."

And he recommends Alfred Marshall's workflow checklist:

Use mathematics as a shorthand language; rather than as an engine of inquiry.

Keep to them till you have done.

Translate into English.

Then illustrate by examples that are important in real life.

Burn the mathematics.

If you can't succeed in 4, burn 3.

This is sage advice.

And to underscore the importance of this advice, I think it is time to hoist the best example I have seen in a while of people with no knowledge of the economics and no control over their models using���simple���math to be idiots: Per Krusell and Tony Smith trying and failing to criticize Thomas Piketty:

(2015) The Theory of Growth and Inequality: Piketty, Zucman, Krusell, Smith, and "Mathiness": It is Krusell and Smith (2014) that suffers from "mathiness"--people not in control of their models deploying algebra untethered to the real world in a manner that approaches gibberish.

I wrote about this last summer, several times:

Department of "Huh?!"--I Don't Understand More and More of Piketty's Critics: Per Krusell and Tony Smith

The Daily Piketty: Ryan Avent on Housing in the Twenty-First Century: Wednesday Focus for June 18, 2014

In Which I Continue to Fail to Understand Why Critics of Piketty Say What They Say: (Late) Friday Focus for June 6, 2014

Depreciation Rates on Wealth in Thomas Piketty's Database

This time, [it was a] reply... to Paul Romer... with a Tweetstorm. Here it is, collected, with paragraphs added and redundancy deleted:

My objection to Krusell and Smith (2014) was that it seemed to me to suffer much more from what you call "mathiness" than does Piketty or Piketty and Zucman. Recall that Krusell and Smith began by saying that they:

do not quite recognize... k/y=s/g...

But k/y=s/g is Harrod (1939) and Domar (1946). How can they fail to recognize it? And then their calibration--n+g=.02, ��=.10--not only fails to acknowledge Piketty's estimates of economy-wide depreciation rate as between .01 and .02, but leads to absolutely absurd results:

For a country with a K/Y=4, ��=.10 -> depreciation is 40% of gross output.

For a country like Belle ��poque France with a K/Y=7, ��=.10 -> depreciation is 70% of gross output....

Krusell and Smith had no control whatsoever over the calibration of their model at all. Note that I am working from notes here, because http://aida.wss.yale.edu/smith/piketty1.pdf no longer points to Krusell and Smith (2014). It points, instead, to Krusell and Smith (2015), a revised version. In the revised version, the calibration differs. It differs in:

raising (n+g) from .02 to .03,

lowering �� from .10 or .05 (still more than twice Piketty's historical estimates), and

changing the claim that as n+g->0 K/Y increases "only very marginally" to the claim that it increases "only modestly". The right thing to do, of course, would be to take economy-wide ��=.02 and say that k/y increases "substantially".)

If Krusell and Smith (2015) offer any reference to Piketty's historical depreciation estimates, I missed it. If it offers any explanation of why they decided to raise their calibration of n+g when they lowered their ��, I missed that too.

Piketty has flaws, but it does not seem to me that working in a net rather than a gross production function framework is one of them.

And Krusell and Smith's continued attempts to demonstrate otherwise seem to me to suffer from "mathiness" to a high degree.

Here are the earlier pieces:

[DEPARTMENT OF "HUH?!"--I DON'T UNDERSTAND MORE AND MORE OF PIKETTY'S CRITICS: PER KRUSELL AND TONY SMITH](DEPARTMENT OF "HUH?!"--I DON'T UNDERSTAND MORE AND MORE OF PIKETTY'S CRITICS: PER KRUSELL AND TONY SMITH): As time passes, it seems to me that a larger and larger fraction of Piketty's critics are making arguments that really make no sense at all--that I really do not understand how people can believe them, or why anybody would think that anybody else would believe them. Today we have Per Krusell and Tony Smith assuming that the economy-wide capital depreciation rate �� is not 0.03 or 0.05 but 0.1--and it does make a huge difference...

Per Krusell and Tony Smith: Piketty���s ���Second Law of Capitalism��� vs. standard macro theory: "Piketty���s forecast does not rest primarily on an extrapolation of recent trends...

...[which] is what one might have expected, given that so much of the book is devoted to digging up and displaying reliable time series.... Piketty���s forecast rests primarily on economic theory. We take issue.... Two ���fundamental laws���, as Piketty dubs them... asserts that K/Y will, in the long run, equal s[net]/g.... Piketty... argues... s[net]/g... will rise rapidly in the future.... Neither the textbook Solow model nor a ���microfounded��� model of growth predicts anything like the drama implied by Piketty���s theory.... Theory suggests that the wealth���income ratio would increase only modestly as growth falls...

And if we go looking for why they believe that "theory suggests that the wealth���income ratio would increase only modestly as growth falls", we find:

Per Krusell and Tony Smith: Is Piketty���s ���Second Law of Capitalism��� Fundamental? : "In the textbook model...

...the capital- to-income ratio is not s[net]/g but rather s[gross]/(g+��), where �� is the rate at which capital depreciates. With the textbook formula, growth approaching zero would increase the capital-output ratio but only very marginally; when growth falls all the way to zero, the denominator would not go to zero but instead would go from, say 0.12--with g around 0.02 and ��=0.1 as reasonable estimates--to 0.1.

But with an economy-wide capital output ratio of 4-6 and a depreciation rate of 0.1, total depreciation--the gap between NDP and GDP--is not its actual 15% of GDP, but rather 40%-60% of GDP. If the actual depreciation rate were what Krussall and Smith say it is, fully half of our economy would be focused on replacing worn-out capital.

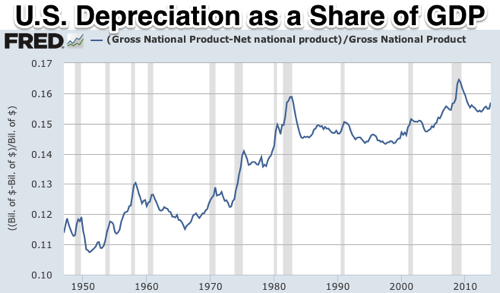

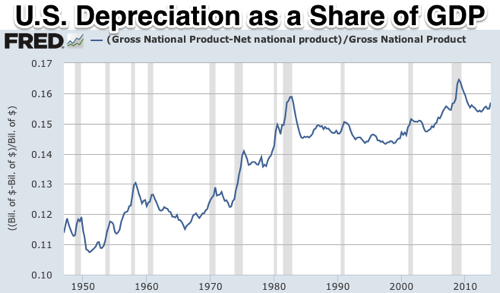

It isn't:

That makes no sense at all.

For the entire economy, one picks a depreciation rate of 0.02 or 0.03 or 0.05, rather than 0.10.

I cannot understand how anybody who has ever looked at the NIPA, or thought about what our capital stock is made of, would ever get the idea that the economy-wide depreciation rate ��=0.1.

And if you did think that for an instant, you would then recognize that you have just committed yourself to the belief that NDP is only half of GDP, and nobody thinks that--except Krusall and Smith. Why do they think that? Where did their ��=0.1 estimate come from? Why didn't they immediately recognize that that deprecation estimate was in error, and correct it?

Why would anyone imagine that any growth model should ever be calibrated to such an extraordinarily high depreciation rate?

And why, when Krusell and Smith snark:

we do not quite recognize [Piketty's] second law K/Y = s/g. Did we miss something quite fundamental[?]... The capital-income ratio is not s/g but rather s/(g+��) no reference to Piketty's own explication of s/(n+��), where �� is the rate at which capital depreciates...

do they imply that this is a point that Piketty has missed, rather than a point that Piketty explicitly discusses at Kindle location 10674?

?One can also write the law ��=s/g with s standing for the total [gross] rather than the net rate of saving. In that case the law becomes ��=s/(g+��) (where �� now stands for the rate of depreciation of capital expressed as a percentage of the capital stock)...

I mean, when the thing you are snarking at Piketty for missing is in the book, shouldn't you tell your readers that it is explicitly in the book rather than allowing them to believe that it is not?

I really do not understand what is going on here at all...

In Which I Continue to Fail to Understand Why Critics of Piketty Say What They Say: "Per Krusell II: So I wrote this on Friday, and put it aside because I feared that it might be intemperate, and I do not want to post intemperate things in this space.

Today, Sunday, I cannot see a thing I want to change���save that I am, once again, disappointed by the quality of critics of Piketty: please step up your game, people!

In response to my Department of ���Huh?!������I Don���t Understand More and More of Piketty���s Critics: Per Krusell and Tony Smith, Per Krusell unfortunately writes:

Brad DeLong has written an aggressive answer to our short note���. Worry about increasing inequality��� is no excuse for [Thomas Piketty���s] using inadequate methodology or misleading arguments���. We provided an example calculation where we assigned values to parameters���among them the rate of depreciation. DeLong���s main point is that the [10%] rate we are using is too high���. Our main quantitative points are robust to rates that are considerably lower���. DeLong���s main point is a detail in an example aimed mainly, it seems, at discrediting us by making us look like incompetent macroeconomists. He does not even comment on our main point; maybe he hopes that his point about the depreciation rate will draw attention away from the main point. Too bad if that happens, but what can we do���

Let me assure one and all that I focused���and focus���on the depreciation assumption because it is an important and central assumption. It plays a very large role in whether reductions in trend real GDP growth rates (and shifts in the incentive to save driven by shifts in tax regimes, revolutionary confiscation probabilities, and war) can plausibly drive large shifts in wealth-to-annual-income ratios. The intention is not to distract with inessentials. The attention is to focus attention on what is a key factor, as is well-understood by anyone who has control over their use of the Solow growth model.

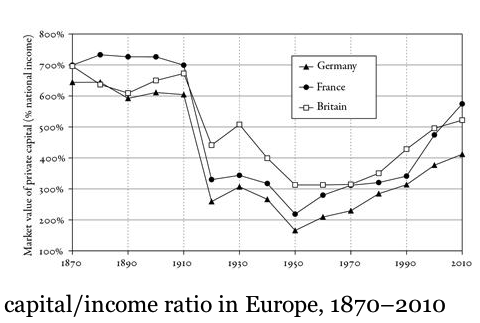

Consider the Solow growth model Krusell and Smith deploy, calibrated to what Piketty thinks of as typical values for the 1914-80 Social Democratic Era: a population trend growth rate n=1%/yr, a labor-productivity trend growth rate g=2%/yr, W/Y=3.

Adding in the totally ludicrous Krusell-Smith depreciation assumption of 10%/yr means (always assuming I have not made any arithmetic errors) that a fall in n+g from 3%/yr to 1%/yr, holding the gross savings rate constant, generates a rise in the steady-state wealth-to-annual-net-income ratio from 3 to 3.75���not a very big jump for a very large shift in economic growth: the total rate of growth n+g has fallen by 2/3, but W/Y has only jumped by a quarter.

Adopting a less ludicrously-awry ���Piketty��� depreciation assumption of 3%/yr generates quantitatively (and qualitatively!) different results: a rise in the steady-state wealth-to-annual-net-income ratio from 3 to 4.708���the channel is more than twice has powerful.

We have a very large drop in Piketty���s calculations of northwest European economy-wide wealth-to-annual-net-income ratios from the Belle ��poque Era that ended in 1914 to the Social Democratic Era of 1914-1980 to account for. How would we account for this other than by (a) reduced incentives for wealthholders to save and reinvest and (b) shifts in trend rates of population and labor-productivity growth? We are now in a new era, with rising wealth-to-annual-net-income ratios. We would like to be able to forecast how far W/Y will rise given the expected evolution of demography and technology and given expectations about incentives for wealthholders to save and reinvest.

How do Krusell and Smith aid us in our quest to do that?

Depreciation Rates on Wealth in Thomas Piketty's Database:: Thomas Piketty emails:

We do provide long run series on capital depreciation in the "Capital Is Back" paper with Gabriel [Zucman] (see http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/capitalisback, appendix country tables US.8, JP.8, etc.). The series are imperfect and incomplete, but they show that in pretty much every country capital depreciation has risen from 5-8% of GDP in the 19th century and early 20th century to 10-13% of GDP in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, i.e. from about 1%[/year] of capital stock to about 2%[/year].

Of course there are huge variations across industries and across assets, and depreciation rates could be a lot higher in some sectors. Same thing for capital intensity.

The problem with taking away the housing sector (a particularly capital-intensive sector) from the aggregate capital stock is that once you start to do that it's not clear where to stop (e.g., energy is another capital intensive sector). So we prefer to start from an aggregate macro perspective (including housing). Here it is clear that 10% or 5% depreciation rates do not make sense.

No, James Hamilton, it is not the case that the fact that "rates of 10-20%[/year] are quite common for most forms of producers��� machinery and equipment" means that 10%/year is a reasonable depreciation rate for the economy as a whole--and especially not for Piketty's concept of wealth, which is much broader than simply produced means of production.

No, Pers Krusell and Anthony Smith, the fact that:

[you] conducted a quick survey among macroeconomists at the London School of Economics, where Tony and I happen to be right now, and the average answer was 7%[/year...

for "the" depreciation rate does not mean that you have any business using a 10%/year economy-wide depreciation rate in trying to assess how the net savings share would respond to increases in Piketty's wealth-to-annual-net-income ratio.

Who are these London School of Economics economists who think that 7%/year is a reasonable depreciation rate for a wealth concept that attains a pre-World War I level of 7 times a year's net national income? I cannot imagine any of the LSE economists signing on to the claim that back before WWI capital consumption in northwest European economies was equal to 50% of net income--that depreciation was a third of gross economic product.

One more remark: if more than half LSE macroeconomists really do believe that net domestic product is 28% lower than gross domestic product���for that is what a depreciation rate of 7% per year gets you with an aggregate capital-output ratio of 4���then more than half of LSE macroeconomists need to be in a different profession. I don't believe Krusell and Smith's survey. I don't believe their LSE colleagues told them what they claimed they had...

Books That It Is Time to Reread: Richard H. Thaler (2015)...

Books That It Is Time to Reread: Richard H. Thaler (2015): Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics: (0393080943): A Rationalist writes: "'The foundation of political economy and, in general of every social science, is evidently psychology...

...A day may come when we shall be able to deduce the laws of social science from the principles of psychology. ���Vilfredo Pareto, 1906

Misbehaving is a thoroughly enjoyable read, both comprehensive and replete with historical context, but "neither a treatise nor a polemic" as prefaced by Thaler. Instead, it is a memoir and a chronological history on the rise of behavioral economics as a legitimate discipline, making it an excellent introduction to the field. The book is lengthy, an un-lazy 358 pages, but an easy read because of Thaler's self-deprecating style and numerous examples that are both funny and informative (like oenophile mental accounting). My favorite illustrative anecdote, however, was the kerfuffle that ensued among the "efficient market" professors at the University of Chicago when it came time to hold a lottery on allocating offices in their new academic building - hilarious.

I got hooked on behavioral economics almost 20 years ago at a conference held on the topic at Harvard's Kennedy School, featuring Richard Thaler, Richard Zeckhauser, Arnie Wood and others. The seeds planted from that fascinating seminar led me to be a lifelong student of this emerging, multi-disciplinary field and the importance of metacognition - quite literally, thinking about thinking. For an alcoholic, admitting you have a problem is the first step towards recovery. Analogously, it is impossible to temper evolutionarily prewired heuristics and biases unless you have studied them - and even then, it is too easy to 'fall off the wagon.' Anchoring, myopic loss aversion, overconfidence and hyperbolic discounting are all pervasive, but you have to understand the nature of these inherent biases to have any chance of counteracting them in your own behavior, both personally and professionally...

Should-Read: Very smart pickup about teaching���and doin...

Should-Read: Very smart pickup about teaching���and doing���economics from Paul Romer and Alfred Marshall by the highly estimable Tim Taylor: Tim Taylor: Some Thoughts About Economic Exposition in Math and Words: "[Paul Romer's] notion that math is 'both more precise and more opaque' than words is an insight worth keeping...

...It reminded me of an earlier set of rules from the great economist Alfred Marshall, who... wrote in 1906 letter to Alfred Bowley (reprinted in A.C. Pigou (ed.), Memorials of Alfred Marshall,��1925 edition, quotation on p. 427):��

But I know I had a growing feeling in the later years of my work at the subject that a good mathematical theorem dealing with economic hypotheses was very unlikely to be good economics; and I went more and more��on the rules:

Use mathematics as a shorthand language; rather than as an engine of inquiry.

Keep to them till you have done.

Translate into English.

Then illustrate by examples that are important in real life.

Burn the mathematics.

If you can't succeed in 4, burn 3.

This last I did often.... Mathematics used in a Fellowship thesis by a man who is not a mathematician by nature���and I have come across a good deal of that���seems to me an unmixed evil. And I think you should do all you can to prevent people from using Mathematics in cases in which the English language is as short as the Mathematical...

February 23, 2018

Should-Read: Saying that gender inequality in Denmark is ...

Should-Read: Saying that gender inequality in Denmark is one third wage and salary rates, one third hours conditional on participation in the paid labor force, and one third labor force participation simply does not do it for me. Informed people make choices in environments. Discrimination and unfreedom is found not in outcome measures but in choice sets���plus the knotty question of how and what people are taught they should prefer, and how such preferences are then enforced: Hate the game, not the players. And does the departure of children from the household then close the gap? The authors take a stab at this with their analyses of the intergenerational transmission of lowered female earnings upon child arrival through the female line. But I want MOAR!: Henrik Kleven, Camille Landais, and Jakob Egholt S��gaard: CHILDREN AND GENDER INEQUALITY: EVIDENCE FROM DENMARK: "Despite considerable gender convergence over time, substantial gender inequality persists in all countries...

...Using Danish administrative data from 1980-2013 and an event study approach, we show that most of the remaining gender inequality in earnings is due to children. The arrival of children creates a gender gap in earnings of around 20% in the long run, driven in roughly equal proportions by labor force participation, hours of work, and wage rates. Underlying these ���child penalties���, we find clear dynamic impacts on occupation, promotion to manager, sector, and the family friendliness of the firm for women relative to men. Based on a dynamic decomposition framework, we show that the fraction of gender inequality caused by child penalties has increased dramatically over time, from about 40% in 1980 to about 80% in 2013. As a possible explanation for the persistence of child penalties, we show that they are transmitted through generations, from parents to daughters (but not sons), consistent with an influence of childhood environment in the formation of women���s preferences over family and career...

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers