J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 407

January 27, 2018

Should-Read: 0.5%/year increase in ocean transport speeds...

Should-Read: 0.5%/year increase in ocean transport speeds in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries. A bunch of this is capital deepening���figure it is better thought of as a measure of the growth rate of the efficiency of labor E than of total factor productivity A: Morgan Kelly and Cormac �� Gr��da: Speed under sail during the early Industrial Revolution: "The consensus among economic (but not maritime) historians that maritime technology was more or less stagnant for 300 years...

...until iron steamships appeared in the mid-19th century is largely based on indirect measures, such as changes in the cost of shipping freight or the length of voyages. This column instead looks directly at how the speed of ships in different winds improved over time. The speed of British ships rose by around half between 1750 and 1830 (albeit from a low base) thanks to innovations like the copper plating of hulls and the move from wooden to iron joints and bolts...

Should-Read: Definitely an ongoing debate to follow: Brin...

Should-Read: Definitely an ongoing debate to follow: Brink Lindsey and Steven M. Teles: The Regulatory Subsidy for Extreme Leverage: A Reply to Mike Konczal: "We do not argue���although Konczal suggests we do���that the problem with financial regulation is a dearth of 'economic liberty'...

...that can be remedied by ���getting government out of the way.��� The modern state and modern finance have been inextricably connected since the origins of both. Accordingly, our analytical starting point is to take as given an active government role in overseeing the financial sector. The question, therefore, is entirely one of choosing which institutional arrangements the state uses to facilitate and structure financial markets, with a view to the different effects of various possible arrangements on stability, growth, and inequality. Our contention is that the United States has adopted���typically at the behest of the financial industry��� institutional arrangements that generate high system instability while redistributing income and wealth upwards. Nothing in our argument should be understood to suggest that the problem is ���too much regulation��� and the answer is ���deregulation,��� for the simple reason that, at the margin where policy change occurs, those terms are basically meaningless. Reducing regulation on the one hand (say, by reducing limits on leverage) may just increase the role of the state (through bailouts) on the other...

January 26, 2018

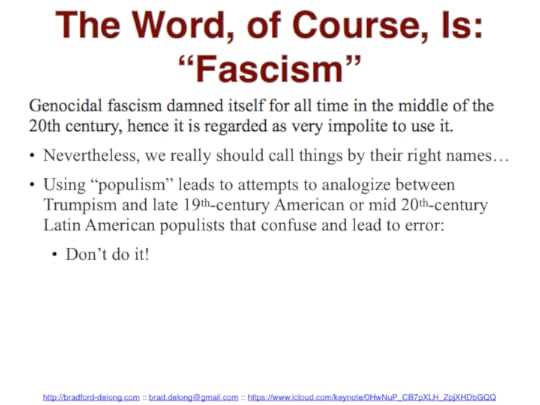

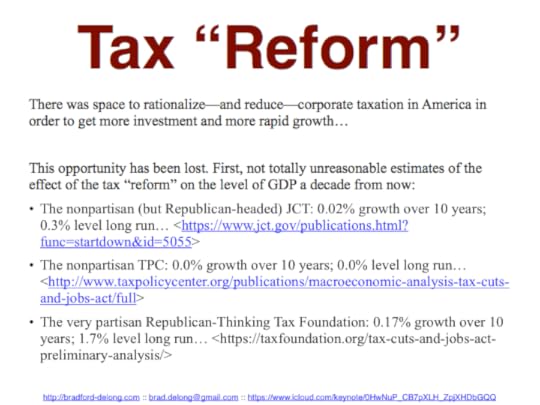

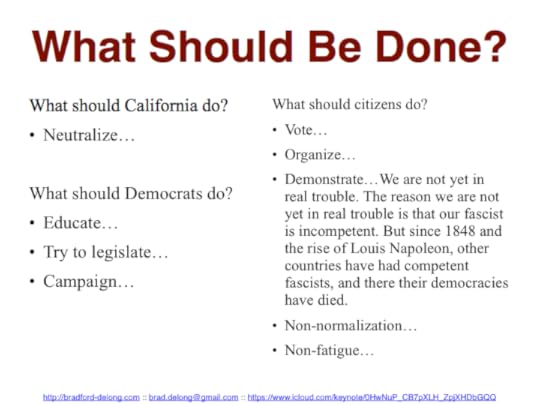

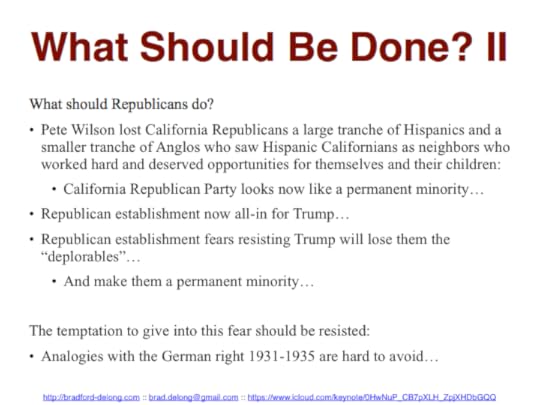

Thinking About President Donald Trump

Berkeley Faculty Club :: 5 PM :: Fri Jan 26, 2018

Slides: https://www.icloud.com/keynote/0HwNuP_CB7pXLH_ZpjXHDbGQQ

Must-Read*: Ursula K. LeGuin (1928-2018) against utilitar...

Must-Read*: Ursula K. LeGuin (1928-2018) against utilitarian moral philosophy: **Ursula K. LeGuin (1973): the ones who walk away from omelas: "With a clamor of bells that set the swallows soaring, the Festival of Summer came to the city of Omelas, bright towered by the sea...

...The rigging of the boats in the harbor sparkled with flags. In the streets between houses with red roofs and painted walls, between old moss-grown gardens and under avenues of trees, past great parks and public buildings, processions moved. Some were decorous: old people in long, stiff robes of mauve and grey, quiet, merry women carrying their babies and chatting as they walked. In other streets the music beat faster and the people were dancing. Children ran in and out, and boys and girls exercised their horses, getting them ready for the races. In the silence of the broad green meadow, one could hear the music winding through the city streets��� a cheerful faint sweetness of the air that from time to time trembled and gathered together and broke out in the great joyous clanging of the bells.

Joyous! How is one to tell about joy? How to describe the citizens of Omelas?

They were not simple folk, you see, though they were happy. But we do not say words of cheer anymore. All smiles have become old. Given a description such as this one tends to make you have certain assumptions. Given a description such as this one tends to make you look for the King, mounted on a great stallion, leading the processions of dancers and citizens of Omelas.

But there was no King.

They did not use swords or keep slaves in Omelas. They were not barbarians. I do not know the rules or laws of their society, but I suspect there were only a few. As they did without a King and without slavery, they also did without the stock exchange, the secret police, and bombs.

Yet I repeat these WERE NOT simple folk. They were not less complex than us. The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by scholars and philosophers, as considering happiness as a something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil is interesting. This is the sin of the artist: a refusal to admit that evil is dull and pain is boring.

How can I tell you about the people of Omelas? They were not na��ve and happy children, though their children were. They were mature, intelligent, passionate adults whose lives were not horrible. O Miracle! But I wish I could describe it better to you. I wish I could convince you! Omelas sounds in my words like a city in a fairy tale, long ago and far away, once upon a time. Perhaps it would be best if you imagined it however you want to��� for certainly I cannot describe well enough to suit you all. For instance, how about technology? I think that there would be no cars or helicopters in and above the streets of Omelas. Happiness is based on a just discrimination of what is necessary��� and in Omelas, cars and helicopters was just not necessary. The people of Omelas could have had central heating and air, subway trains, washing machines, and all kinds of marvelous devices not yet invented here like floating light sources and the cure for the common cold��� or they could have had none of that. It doesn���t really matter. As you like it. Imagine it as you will.

One thing I know there was none of in Omelas is guilt. But what else should there be? I thought at first there were no drugs there, but that is na��ve of me to think. What else? What else belongs in this joyous city? The sense of victory! The celebration of courage! There are no soldiers, therefore there is no war. Victory caused by death is not the right kind of joy. Being content, and in communion with everyone is what brings joy to the hearts of the people of Omelas. The victory they celebrate is life!

Most of the processions have reached the Green Fields by now. A marvelous smell of cooking goes forth from the red and blue tents of the cooks. The faces of small children are sticky, and in the grey beards of the elderly a couple of cupcakes crumbs are entangled. The youths and girls have mounted their horses and are beginning to group around the starting line of the race. An old woman, small, fat and laughing, is passing out flowers from a basket. Tall young men wear her flowers in their shining hair. A child of nine or ten sits as the edge of the crowd, alone, playing a wooden flute. People pause to listen, and they smile, but they do not speak to him, for he never stops playing and never sees them. He is so lost in his music, the sweet, thin magic of the tune. He finishes, and slowly lowers the flute.

As if that little private silence were the signal, all at once a trumpet sounds from the pavilion near the starting line: imperious, melancholy, piercing. The horses rear on their slender legs, and some of them neigh in answer. Sober-faced, the young riders calmly stroke the horses��� necks and soothe them, whispering, ���Quiet, quiet there my beauty��� my hope...��� They begin to form in rank along the starting line. The crowds along the race course are like a field of grass and flowers in the wind. The Festival of Summer has begun.

Do you believe? Do you accept the festival, the city, the joy? No? Then let me describe one more thing.

In the basement under one of the beautiful public buildings of Omelas, there is a room. It has one locked door, and no window. A little light seeps in dustily between the cracks in the boards, secondhand from a cobwebbed window somewhere across the cellar. In one corner of the little room a couple of mops, with stiff, clotted, foul-smelling heads stand near a rusty bucket. The floor is dirt, a little damp to the touch, as cellar dirt usually is. The room is about three feet long and two feet wide: a mere broom closet of a disused tool room.

In the room a child is sitting. It could be a boy or a girl. It looks about six years old, but actually it is near ten. It is feeble-minded and slow. Perhaps it was born defective, or perhaps it has become imbecile through fear, malnutrition, and neglect. It picks its nose and occasionally fumbles vaguely with its��� toes. It sits hunched in the corner farthest from the bucket and the two mops. It is afraid of the mops. It finds them horrible. It shuts its eyes, but it knows the mops are still standing there; and the door is locked; and no one will come.

The door is always locked and nobody ever comes, except that sometimes-the child has no understanding of time-sometimes the door rattles terribly��� and opens, and a person (or several people) are standing there. One of them may come in and kick the child to make it stand up. The others never come close, but peer in at it with frightened disgusted eyes. The food bowl and the water just are hastily filled, and the door is locked, the eyes disappear.

The people at the door never say anything. But the child, who has not always lived in the closet, and can remember sunlight and his mother���s voice, sometimes says, ���I will be good.��� It says, ���Please let me out. I will be good.��� They never answer it. The child used to scream for help at night, and cry a lot. But now it only makes a sort of whining, ���eh-haa, eh-haaaaaa,��� and it speaks less and less often. It is so thin there are no calves to its legs; its belly protrudes; it lives on a half-bowl of corn meal and grease a day. It is naked. Its buttocks and thighs are a mass of festered sores, as it sits in its own excrement continually.

They all know it is there, all the people of Omelas. Some of them have come to see it; others are content merely to know it is there. They all know that is HAS to be there. Some of them understand why, and some do not, but they all understand that their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the kindly weathers of their skies depend wholly on this child���s horrid misery.

This is usually explained to children when they are between eight and twelve, whenever they seem capable of understanding. And most of those who come to see the child are young people, though often enough an adult comes, or comes back, to see the child. No matter how well the matter has been explained to them, these young spectators are always shocked and sickened at the sight. They feel disgust, which they had thought themselves superior to. They feel anger and outrage despite all the explanations. They would like to do something for the child. But there is nothing they can do.

If the child were brought up into the sunlight out of that vile place, if it were cleaned and fed and comforted, that would be a good thing indeed; but if it were done, in that day and hour, all prosperity and beauty and delight of Omelas would wither and be destroyed. Those are the terms. To exchange all the goodness and grace of every life in Omelas for that single, small improvement: to throw away the happiness of thousands for the chance of the happiness of one: that would definitely let guilt within the walls of Omelas.

The terms are strict and absolute; there may NOT even be a kind word spoken to the child. Often the young people go home in tears, or in a tearless rage, when they have seen the child and faced this terrible paradox. They may brood over it for weeks or years.

But as times goes on they begin to realize that even if the child could be released, it would not get much good of its freedom; a little vague pleasure of warmth and food, no doubt, but little more. It is too degraded and dumb to know any real joy. It has been afraid too long ever to be free of fear. Its habits are too barbaric for it to respond to normal human treatment. Indeed, after so long it would probably be wretched without walls about it to protect it, and darkness for its eyes, and its own excrement to sit in.

The peoples��� tears at the injustice dry when they begin to perceive the terrible justice of reality, and to accept helplessness, which are perhaps the true source of splendor in their lives. They know that they, like the child, are not free. They know compassion. It is the existence of the child, and their knowledge of its existence, that makes possible their elaborate buildings and mansions, the magic of their music, the greatness of their science. It is because of the child that they are so gentle with children. They know that if the wretched one were not there suffering in the dark, the other one, the flute-payer, could make no joyful music as the young riders line up their horses for the race.

Now do you believe in them? Are they not more credible? But there in one more thing to tell, and this is quite incredible.

At times one of the adolescent girls or boys who go to see the child does not go home to weep or rage, does not, in fact, go home at all. Sometimes also a man or woman, much older, falls silent for a day or two, and then leaves home. These people go out into the street, and walk down the street alone. They keep walking, and walk straight out of the city of Omelas, through the beautiful gates. They keep walking across the farmlands of Omelas.

Each one goes alone, youth or girl, man or woman. Night falls; the traveler must pass down village streets, between the houses with yellow-lit windows, and on out into the darkness of the fields. Each alone, they go west or north, towards the mountains.

They go on. They leave Omelas, they walk ahead into the darkness, and they do not come back. The place they go towards is a place even less imaginable to most of us that the city of happiness. I cannot describe it at all. It is possible that it does not exist.

But they seem to know where they are going, the ones who walk away from Omelas.

January 22, 2018

Reading Question/Note Files for Bob Allen: Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction

Reading Question/Note Files for Bob Allen: Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction:

Robert Allen: Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction (0199596654):

http://www.bradford-delong.com/2017/01/reading-robert-allen-2011-global-economic-history-a-very-short-introduction-chapter-1.html

http://www.bradford-delong.com/2017/01/reading-robert-allen-2011-global-economic-history-a-very-short-introduction-chapter-2.html

http://www.bradford-delong.com/2017/01/reading-robert-allen-2011-global-economic-history-a-very-short-introduction-chapter-4.html

http://www.bradford-delong.com/2017/01/reading-robert-allen-2011-global-economic-history-a-very-short-introduction-chapter-5.html

http://www.bradford-delong.com/2017/01/reading-robert-allen-2011-_global-economic-history-a-very-short-introduction_-new-york-oxford-chapter-6.html

http://www.bradford-delong.com/2017/01/reading-robert-allen-2011-_global-economic-history-a-very-short-introduction_-new-york-oxford-chapter-7.html

http://www.bradford-delong.com/2017/01/reading-robert-allen-2011-global-economic-history-a-very-short-introduction-chapter-8.html

http://www.bradford-delong.com/2017/01/reading-robert-allen-2011-global-economic-history-a-very-short-introduction-chapter-9.html

http://www.bradford-delong.com/2017/01/robert-allen-2011-global-economic-history-a-very-short-introduction-epilogue.html

Should-Read: A very interesting paper by very sharp peopl...

Should-Read: A very interesting paper by very sharp people. The problem is that I do to know what it means. The post-2000 period has one huge, huge, huge shock in it: 2008-2009. How is the fact that the post-2000 sample has a Great Recession in it and the pre-2000 does not affect their conclusions? I don't know. And I don't think they know: Ryan A. Decker, John C. Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda: Changing Business Dynamism and Productivity: Shocks vs. Responsiveness: "The pace of job reallocation has declined in all U.S. sectors since 2000...

...In standard models, aggregate job reallocation depends on (a) the dispersion of idiosyncratic productivity shocks faced by businesses and (b) the marginal responsiveness of businesses to those shocks. Using several novel empirical facts from business microdata, we infer that the pervasive post-2000 decline in reallocation reflects weaker responsiveness in a manner consistent with rising adjustment frictions and not lower dispersion of shocks. The within-industry dispersion of TFP and output per worker has risen, while the marginal responsiveness of employment growth to business-level productivity has weakened. The responsiveness in the post-2000 period for young firms in the high-tech sector is only about half (in manufacturing) to two thirds (economy wide) of the peak in the 1990s. Counterfactuals show that weakening productivity responsiveness since 2000 accounts for a significant drag on aggregate productivity...

January 21, 2018

Weekend Reading: Winston Churchill on January 27, 1942 on the War Situation

Hansard: Winston Churchill (January 27, 1942): WAR SITUATION: "We prepared to set upon Rommel and try to make a good job of him...

...for the sake of this battle in the Libyan Desert we concentrated everything we could lay our hands on, and we submitted to a very long delay, very painful to bear over here, so that all preparations could be perfected. We hoped to recapture Cyrenaica and the important airfields round Benghazi. But General Auchinleck's main objective was more simple. He set himself to destroy Rommel's army. Such was the mood in which we stood three or four months ago. Such was the broad strategical decision we took.

Now, when we see how events, which so often mock and falsify human effort and design, have shaped themselves, I am sure this was a right decision.

General Auchinleck had demanded five months' preparation for his campaign, but on 18th November he fell upon the enemy. For more than two months in the desert the most fierce, continuous battle has raged between scattered bands of men, armed with the latest weapons, seeking each other dawn after dawn, fighting to the death throughout the day and then often long into the night. Here was a battle which turned out very differently from what was foreseen. All was dispersed and confused. Much depended on the individual soldier and the junior officer.

Much, but not all; because this battle would have been lost on 24th November if General Auchinleck had not intervened himself, changed the command and ordered the ruthless pressure of the attack to be maintained without regard to risks or consequences. But for this robust decision we should now be back on the old line from which we had started, or perhaps further back. Tobruk would possibly have fallen, and Rommel might be marching towards the Nile. Since then the battle has declared itself. Cyrenaica has been regained. It has still to be held. We have not succeeded in destroying Rommel's army, but nearly two-thirds of it are wounded, prisoners or dead.

Perhaps I may give the figures to the House. In this strange, sombre battle of the desert, where our men have met the enemy for the first time���I do not say in every respect, because there are some things which are not all that we had hoped for���but, upon the whole, have met him with equal weapons, we have lost in killed, wounded and captured about 18,000 officers and men, of whom the greater part are British. We have in our possession 36,500 prisoners, including many wounded, of whom 10,500 are Germans. We have killed and wounded at least 11,500 Germans and 13,000 Italians���in all a total, accounted for exactly, of 61,000 men. There is also a mass of enemy wounded, some of whom have been evacuated to the rear or to the Westward���I cannot tell how many.

Of the forces of which General Rommel disposed on 18th November, little more than one-third now remain, while 852 German and Italian aircraft have been destroyed and 336 German and Italian tanks. During this battle we have never had in action more than 45,000 men, against enemy forces���if they could be brought to bear���much more than double as strong. Therefore, it seems to me that this heroic, epic struggle in the desert, though there have been many local reverses and many ebbs and flows, has tested our manhood in a searching fashion and has proved not only that our men can die for King and country���everyone knew that���but that they can kill.

I cannot tell what the position at the present moment is on the Western front in Cyrenaica. We have a very daring and skillful opponent against us and, may I say across the havoc of war, a great General. He has certainly received reinforcements. Another battle is even now in progress, and I make it a rule never to try and prophesy beforehand how battles will turn out. I always rejoice that I have made that rule....

Whereas a year ago the Germans were telling all the neutrals that they would be in Suez by May, when some people talked of the possibility of a German descent upon Assiut, and many people were afraid that Tobruk would be stormed and others feared for the Nile Valley, Cairo, Alexandria and the Canal, we have conducted an effective offensive against the enemy and hurled him backward, inflicting upon him incomparably more���well, I should not say incomparably, because I have just given the comparison���but far heavier losses and damage than we have suffered ourselves. Not only has he lost three times our losses on the battlefield, approximately, but the blue waters of the Mediterranean have, thanks to the enterprise of the Royal Navy, our submarines and Air Force, drowned a large number of the reinforcements which have been continually sent. This process has had further important successes during the last few days.

Whether you call it a victory or not, it must be dubbed up to the present, although I will not make any promises, a highly profitable transaction, and certainly is an episode of war most glorious to the British, South African, New Zealand, Indian, Free French and Polish soldiers, sailors and airmen who have played their part in it. The prolonged, stubborn, steadfast and successful defence of Tobruk by Australian and British troops was an essential preliminary, over seven hard months, to any success which may have been achieved...

Should-Read: Josh Marshall: Trump, Wolff and The Secret o...

Should-Read: Josh Marshall: Trump, Wolff and The Secret of the Russia Story: "The onslaught of negative press allowed Wolff to pose as the only reporter who got the true nature of Trump���s greatness...

...not just publicly, but far more importantly in his private presentation and pitch.... Here was a prestige journalist who got it and could help. It was like offering crack.... Wolff... ���I certainly said what was ever necessary to get the story.��� To ensnare Trump���s coterie of gullible toadies he actually made the working title of his book ���The Great Transition: The First 100 Days of the Trump Administration.��� It was always hilarious and maddening to see Wolff... pose as the chronicler and connoisseur of Trumpite real America.... Trump got the biographer he deserved. Wolff is shamelessly manipulative and hasn���t the slightest hesitation about deceiving his sources to ���get the story���, as he puts it. Indeed, this is a long, even darkly august journalistic tradition. Not my cup of tea, personally. But if real facts are unearthed and they���re important ones to know, who can say it���s a bad thing? Such a reporter sacrifices their honor and honesty���perhaps often their dignity���in the service of the public good���if they���ve got a real story...

Yes, People at the Ludwig von Mises Institute Think Churchill Was a War Criminal for Not Making Peace with Hitler in May 1940. Why Do You Ask?: Hoisted from the Archives

Hoisted from the Archives: Yes, People at the Ludwig von Mises Institute Think Churchill Was a War Criminal for Not Making Peace with Hitler in May 1940. Why Do You Ask?: David Gordon:

Ludwig von Mises Institute: Given this sorry record, it is hardly surprising that the renewed outbreak of world war in September 1939, which returned Churchill to the British cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty, brought a new hunger blockade of Germany.... Franklin Roosevelt rivaled his British counterpart in his disregard for the rules of civilized warfare....

Long before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on that "date which will live in infamy," December 7, 1941, Roosevelt hoped that the Chinese would bomb the major cities of Japan. Because of the presence of closely packed together wooden buildings, entire cities could readily be set afire.... Roosevelt was anxious for confrontation with the Japanese. Roosevelt's stationing of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor was intended to provoke them....

The moral offenses of Churchill and Roosevelt were not confined to violations of the laws of war.... Hitler wished to expel [the Jews] from Germany, and those willing to emigrate were actively encouraged to do so.... Roosevelt did virtually nothing to help.... Neither did he show much interest in efforts to settle the Jews elsewhere. Churchill, despite his frequently expressed sympathy for Jews and Zionism, was little better....

[W]as it not a clear moral imperative to avoid the outbreak of war and, if possible, to secure the evacuation of the Jews from parts of Europe likely to fall under German control? Further, once war broke out, was it not imperative to end the war as soon as possible? Churchill rejected all efforts to reach a settlement [ending World War II]. He continued the hunger blockade, a move that could only exacerbate the most extreme Nazi policies...

Dictatorships and Double Standards: Jeet Heer Has a Ludwig Von Mises Quote: Hoisted from the Archies

Hoisted from the Archives: Dictatorships and Double Standards: Jeet Heer Has a Ludwig Von Mises Quote...: An example of classical liberalism's elective affinity with authoritarian politics? Ludwig:

It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aiming at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has, for the moment, saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history. But though its policy has brought salvation for the moment, it is not of the kind which could promise continued success. Fascism was an emergency makeshift. To view it as something more would be a fatal error...

So now I have to add Ludwig Von Mises, Liberalism to the pile...

UPDATE: Yes, Ludwig von Mises does indeed do it: he does claim that the reason Mussolini's thugs murdered Giacomo Matteotti was that they were driven to do it out of horror at the crimes committed by the Russian Bolsheviks. It's an old line: they are the monsters, and it's only because they are the monsters that they force us into a situation in which we must act monstrously:

Ludwig von Mises, Liberalism, 1.10: The Argument of Fascism: Only when the Marxist Social Democrats had gained the upper hand and taken power in the belief that the age of liberalism and capitalism had passed forever did the last concessions disappear that [social democracy] had still been thought necessary to make to the liberal ideology. The parties of the Third International consider any means as permissible.... The frank espousal of a policy of annihilating opponents and the murders committed in the pursuance of it have given rise to an opposition movement.... The militaristic and nationalistic enemies of the Third International felt themselves cheated by liberalism. Liberalism, they thought, stayed their hand when they desired to strike a blow against the revolutionary parties while it was still possible to do so....

The fundamental idea of these movements���which, from the name of the most grandiose and tightly disciplined among them, the Italian, may, in general, be designated as Fascist���consists in the proposal to make use of the same unscrupulous methods in the struggle against the Third International as the latter employs against its opponents. The Third International seeks to exterminate its adversaries and their ideas in the same way that the hygienist strives to exterminate a pestilential bacillus.... The Fascists, at least in principle, profess the same intentions.... Only under the fresh impression of the murders and atrocities perpetrated by the supporters of the Soviets were Germans and Italians able to block out the remembrance of the traditional restraints of justice and morality and find the impulse to bloody counteraction. The deeds of the Fascists and of other parties corresponding to them were emotional reflex actions evoked by indignation at the deeds of the Bolsheviks and Communists. As soon as the first flush of anger had passed, their policy took a more moderate course and will probably become even more so with the passage of time....

Now it cannot be denied that the only way one can offer effective resistance to violent assaults is by violence. Against the weapons of the Bolsheviks, weapons must be used in reprisal, and it would be a mistake to display weakness before murderers. No liberal has ever called this into question.... The great danger threatening domestic policy from the side of Fascism lies in its complete faith in the decisive power of violence.... What happens, however, when one's opponent... acts just as violently? The result must be a battle, a civil war. The ultimate victor to emerge from such conflicts will be the faction strongest in number.... The decisive question, therefore, always remains: How does one obtain a majority for one's own party? This, however, is a purely intellectual matter. It is a victory that can be won only with the weapons of the intellect, never by force. The suppression of all opposition by sheer violence is a most unsuitable way to win adherents to one's cause. Resort to naked force���that is, without justification in terms of intellectual arguments accepted by public opinion���merely gains new friends for those whom one is thereby trying to combat. In a battle between force and an idea, the latter always prevails. Fascism can triumph today because universal indignation at the infamies committed by the socialists and communists has obtained for it the sympathies of wide circles. But when the fresh impression of the crimes of the Bolsheviks has paled, the socialist program will once again exercise its power of attraction on the masses.... There is... only one idea that can be effectively opposed to socialism, viz., that of liberalism....

It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aiming at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has, for the moment, saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history. But though its policy has brought salvation for the moment, it is not of the kind which could promise continued success. Fascism was an emergency makeshift. To view it as something more would be a fatal error.

The kindest thing that can possibly be said, I think, is that Ludwig von Mises here demonstrates as little clue to what fascism is all about as he elsewhere demonstrates he understands about capitalism, social democracy, or--indeed-liberalism.

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers