J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2170

October 23, 2010

Economist's View: What's the Big Idea?

Mark Thoma appears to despair:

What's the Big Idea?: I started this blog shortly after George Bush was reelected.... [T]he biggest factor was that I felt Democrats were being misrepresented in the media. CNN in particular comes to mind. In the run-up to the election, it was the same people day after day representing Democrats in the media, and I did not feel they were doing a good job -- at all -- of representing the Party's views on economics or anything else.... It was as though the TV shows would pick the most clueless, outlandish, easiest people to dismiss whenever they interviewed Democrats or pitted Democrats against Republicans. If only people knew who we really are, I would think, and what we actually stand for, certainly they would be persuaded. I never thought it would go anywhere, but starting the blog was part of the reaction to the feeling that Democrats in the silent majority needed to start speaking up and making their voices heard.

Now I'm frustrated again.... Right now, there is no voice, at least not one I can hear. There are plenty of Democrats talking with loud voices, more than ever I'd guess, but there is no leadership.... We finally have control of the ship, and the captain is wandering aimlessly. What is Obama's vision? Where are we trying to go? What is the grander goal that is being served by the polices and strategies he is pursuing? Yes, he gives good speeches, but what is the single theme that runs through them all to coordinate and steer the party toward this larger vision?...

And Josh Marshall says that there are rumors that Bill Clinton appears to half-despair:

Bill's Frustration: A report surfaced today that Bill Clinton is frustrated as heck that the Dems can't manage to get a coherent or persuasive message together for the midterms. And he's even doing what he can to get together good talking points for candidates and stump in all the right places to help save the Democratic majorities even if the current leaders can't manage it themselves.... [A]s you've seen if you've read what I've written over the last three months, I've been distressed by the Democrats' inability or unwillingness to grasp hold of what winning political issues there are in such a rough climate.

But let's not be born yesterday. Anyone over 35 has a good adult memory of the 1994 midterm. That's when Stan Greenberg was telling congressional candidates to run away from President Clinton, just two years after Stan helped engineer his election. Clinton was considered toxic politically in broad swathes of the country... [which] look an awful lot like the swathes where President Obama is toxic today.... [F]or all his political skills President Clinton couldn't do anything the stem the tide. He was impotent, diminished, helpless, crushed and all the rest. Being president is hard. Being president two years into your first term is hard. And being at the center of the polarizing political storm -- as Obama is today and Clinton was 16 years ago -- tends to wipe the political genius and midas touch and all the other good stuff right off of you. 10% unemployment doesn't make you look that good either.

This isn't justifying any mistakes. But I'm surprised how short the memories are of many people who do this political analysis thing for a living.

But Caren Bohan says that Barack Obama does not despair:

Obama accuses Republicans of peddling "snake oil" | TPM News Pages: President Barack Obama... accused Republicans on Friday of peddling discredited "snake oil ideas" about the economy.... Obama portrayed the embattled Reid as a champion for the middle class who stays awake at night worrying about people whose houses have been foreclosed. "You know, Harry's not the flashiest guy, let's face it," Obama told a crowd of about 9,000 people in Las Vegas. "Harry kind of speaks in a very soft voice. He doesn't move real quick. He doesn't get up and make big stem-winding speeches. But Harry Reid does the right thing."...

California Democratic Senator Barbara Boxer is facing a tough challenge from Republican Carly Fiorina, a former chief executive of Hewlett-Packard.... At a rally at the University of Southern California that drew more 37,000 people, Obama portrayed the election as a "choice between the policies that got us into this mess and the policies that will get us out." He acknowledged that economic woes made for a tough election climate for Democrats, but said Republicans seeking control of Congress did not have the answer. "They are clinging to the same worn-out, tired snake oil ideas that they were peddling before," Obama said, referring to Bush-era policies he blames for putting the economy in a deep hole that it is still struggling to climb out of...

Why Quantitative Easing Needs to Involve Securities Other than Government Securities

Paul Krugman writes:

How To Think About QE2 (Wonkish): Still on the run, so no long posts. But with all the talk about further quantitative easing by the Fed — QE2, for quantitative easing, the sequel — I think it’s worth sharing one way of thinking about what’s on the table — and why you shouldn’t be too optimistic about its effects. This isn’t original, although I don’t know who deserves the credit.

So, here it is: in effect, QE2 amounts to a decision by the US government to shorten the maturity of its outstanding debt, paying off long-term bonds while borrowing short-term. This should drive down long-term interest rates. But how much?

How do we get to this view? Think first of the Fed’s balance sheet. The Fed’s liabilities are the monetary base — currency in circulation, plus bank reserves. Those bank reserves are essentially short-term borrowing: the Fed pays a small interest rate on them, which is comparable to the interest rate on Treasury bills. More broadly, in a near-zero-rate world, cash — an official liability that pays no interest — is essentially equivalent to T-bills — another official liability that pays more or less no interest.

What happens when the Fed buys long-term government securities? If we consider the Fed and Treasury as a consolidated entity — which, for fiscal purposes, they are — then what happens is that some long-term federal debt is taken off the market, and paid for by issuing more short-term debt in the form of monetary base. It’s just as if Treasury sold 3-month T-bills and used the proceeds to buy back 10-year bonds.

So the question to ask is, how much do we think federal management of its maturity structure matters for the real economy? I think if you put it that way, most people wouldn’t be terribly optimistic.

Anyway, my jet-lagged thought for the day.

I would put it differently. The point--from one point of view, the neo-Wicksellian point of view--behind quantitative easing is to reduce the interest rate that matters for private business investment: the long-term, default-risky, systemic-risky, beta-risky, real interest rates at which private businesses finance their capital expenditures. You can reduce this flow-of-funds equilibrium interest rate and raise the level of economic activity in any neo-Wicksellian framework in two ways:

Reduce the "safe" real interest rate on short-term, safe government bonds.

Reduce the various premia--duration, default, systemic risk, and beta risk--between the rates the Treasury pays to borrow in T-bills and the rates businesses pay to borrow.

Conventional open-market operations that lower the nominal interest rate on T-bills accomplish the first. Once the nominal interest rate on T-bills has been pushed to zero, quantitative easing policies that create expectations of higher future inflation continue to lower the real interest rate on T-bills and thus help the situation.

Suppose, however, that the nominal interest rate on T-bills is zero and that you cannot alter inflation expectations--cannot commit to keeping your quantitative easing permanent, cannot commit to an exchange rate path, whatever, you cannot do it and inflation expectations are immovable. Then what?

Then, as Paul Krugman says, quantitative easing is working be altering the spread between the short-term safe T-bill rate and the long-term, systemic-risky, beta-risky, default-risky rate. How does it do that? Lloyd Metzler and James Tobin would say that it does so by altering relative asset supplies--by taking duration risk, systemic risk, beta risk, and default premia off of private savers' books and placing them on the government's books (and thus on the taxpayers, who are a very different group of people than are private savers). To the extent that quantitative easing thus involves assets whose risk characteristics are very similar--federal funds and two-year T-notes, say--we would not expect even a lot of quantitative easing to have much of an effect on anything.

Thus a quantitative easing program that is going to have bite should involve Federal Reserve purchases of long-term risky private assets rather than merely long-term U.S. Treasuries. Hiring PIMCO as an agent to manage a long bond index portfolio naturally comes to mind--if one could avoid its front-running.

And, of course, the most effective quantitative easing program of all would involve the Federal Reserve issuing reserve deposits and using that purchasing power to buy the assets that are the furthest away in their risk characteristics from short-term government bonds: bridges, dams, the human capital of American citizens, police protection, research and development. The best quantitative easing program of all is a money-financed fiscal stimulus, as Jacob Viner said back in 1933:

It is often said that the federal government and the Federal Reserve system have practiced inflation during this depression no and that no beneficial effects resulted from it. What in fact happened was that they made mild motions in the direction of inflation, which did not succeed in achieving it.... [If] a deliberate policy of inflation should be adopted, the simplest and least objectionable procedure would be for the federal government to increase its expenditures or to decrease its taxes, and to finance the resultant excess of expenditures over tax revenues either by the issue of legal tender greenbacks or by borrowing from the banks...

Does Bank of America Need to File Its Paperwork?

I am with Duncan Black on this one:

Eschaton: I'm not as optimistic that judges will be all that concerned about whether banks actually have standing to foreclose. People in those homes are bad and owe somebody money and deserve to be chucked out. It doesn't really matter who they owe the money to.

Joe Nocera thinks Bank of America is in trouble:

Bank of America’s Foreclosure Mess Won’t Disappear Quickly: Like everyone else, I’d been reading with amazement the stories about one of those legal problems: the robo-signing scandal that has ensnared all the banks with mortgage servicing subsidiaries, Bank of America included. That’s the scandal in which a tiny handful of employees had signed — or allowed others to forge their signatures — on thousands of affidavits confirming that the banks had the legal right to foreclose on properties they serviced. In truth, they had often never seen the documents proving the bank had that legal right. In some cases, the documents didn’t even exist.... Mr. Moynihan said that, at Bank of America, at least, the foreclosure halt in 23 states that require judicial proceedings was over. It had reviewed some 102,000 affidavits and — guess what? — no big problem! “The teams reviewing data have not found information which was inaccurate” or that would change the plain facts of foreclosure — namely that the homeowners it wanted to foreclose on were in serious arrears. Thus the bank’s central position is that, since it is so doggone obvious that the homeowners can’t pay their mortgages, the fact that the affidavits might not have complied with the law shouldn’t cause anyone to break into a sweat.... The prospect of a second legal assault is more recent. Shortly before the earnings call, Bank of America received a letter from a lawyer representing eight powerful institutional investors, including BlackRock, Pimco and — most amazing of all — the New York Federal Reserve. The letter was a not-so-veiled threat to sue the bank unless it agrees to buy back billions of dollars worth of loans that are in securitized mortgage bonds the investors own..... Mr. Moynihan and Mr. Noski made it clear that Bank of America was going to use hand-to-hand combat to fight back these claims. “We’re protecting the shareholders’ money,” Mr. Moynihan said. Mr. Noski questioned whether the investors even had the right to bring the case. “We continue to review and assess the letter and have a number of questions about its content including whether these investors actually have standing to bring these claims,” he said.

So there you have it. Having convinced millions of Americans to buy homes they couldn’t afford, Bank of America is now revving up its foreclosure efforts on these same homeowners. At the same time, having sold tens of thousands of these same terrible loans to investors, it is going to spend tens of millions of dollars on lawyers to keep from having to buy back their junky loans.

Apparently, being the biggest bank in the country means never having to say you’re sorry...

links for 2010-10-23

slacktivist: The fatted calf is delicious, you should come inside and join the party

Liu Xiaobo and the '300 Years' Problem - James Fallows - International - The Atlantic

Tim Geithner's poor imitation of John Maynard Keynes | Analysis & Opinion |

Making Light: My luve's like a red-shifted light source

British Fashion Victims - NYTimes.com

Yglesias » Deleveraging

Brain Mounted Computers are a Dominant Strategy Equilibrium « Modeled Behavior

FT.com / Comment - Price limits could help to avert 'flash crash' havoc

FT.com / Comment / Editorial - The challenge facing China

Wikileaks Iraq: A Quick Summary - Marc Ambinder - Politics - The Atlantic

Lillian McEwen breaks her 19-year silence about Justice Clarence Thomas

On Hill And The Thomases: How Far Have We Come? : NPR

Republicans Rip into One of Their Own Over VAT Tax - TheFiscalTimes.com

October 22, 2010

A Centrist Critique of Obama

In my inbox:

When it turned out that "post-partisanship" actually meant creating a consensus among wealthy people about how best to repair the damage of the Bush years without in any other way disturbing the status quo—well, who could blame independent voters for being disappointed?

The Physics of Wet Dogs

Can I Call for Replacing the Milibands as the Heads of Britain's Labour Party with Ed Balls?

Ed Balls, August 26:

‘There is an alternative’: I am very grateful to Bloomberg for giving me the opportunity to come here this morning to respond to the bullish speech given from this same platform by George Osborne 10 days ago. That speech is the clearest articulation of the Cameron-Clegg Coalition strategy for this parliament. In it, their Chancellor repeated his claim that fiscal retrenchment through immediate and deep public spending cuts to reduce the fiscal deficit would build financial market confidence in the UK economy, keep interest rates low and secure economic recovery by boosting private investment. And the Chancellor once again declared that his was the only possible credible course....

This is a risky and dangerous time for the world economy. History teaches us that economic recovery following a large-scale financial crisis can be slow and stuttering. In the US, the debate is not about fiscal tightening but whether further stimulus is needed.... Here in Britain we have seen, in recent days, MPC member Martin Weale warn of the risk of a double-dip recession as a result of the current fiscal tightening. But whether our economy continues to recover or slips back into sustained slow growth – even recession again – is not just a concern for Treasury ministers and financial analysts. Whether our leaders make the right calls now on growth and jobs, the deficit, public spending and welfare reform will determine the future of our country for the next decade or more and shape the kind of society we want to be.

I do believe we face a choice as a country – on the economy and the future of our public services and the welfare state. And today I want to respond to what I believe was a fundamentally flawed speech ten days ago: - wrong in its analysis of the past; - reckless in its diagnosis of the current situation; and - dangerous in its prescription for the future.

This week’s IFS analysis of the June Budget has confirmed what we already knew – that the Coalition’s economic and fiscal strategy is deeply unfair. In this speech I will argue that it is also unnecessary, unsafe for our economy and unsafe for our public services too....

We do need a credible and medium-term plan to reduce the deficit and to reduce our level of national debt – a pre-announced plan for reducing the deficit based on a careful balance between employment, spending and taxation – but only once growth is fully secured and over a markedly longer period than the government is currently planning.... [B]y ripping away the foundations of growth and jobs in Britain – David Cameron, Nick Clegg and George Osborne are not only leaving us badly-exposed to the new economic storm that is coming, but are undermining the very goals of market stability and deficit reduction which their policies are designed to achieve. Far from learning from our history it is my fear that the new Coalition government is set to repeat the mistakes of history – and that George Osborne’s declaration of ‘cautious optimism’ on this platform a fortnight ago may go down in history alongside Norman Lamont singing in his bath.

But it is not too late to change course....

First, let me say why I think it is so important for me – and indeed every other candidate who seeks to lead the Opposition – to stand up now and challenge the current consensus that – however painful – there is no alternative to the Coalition’s austerity and cuts. Because as someone who was at the heart of the decision on whether Britain should join the Euro, it seems incredible to me that such fundamental and far-reaching economic decisions are being taken by the coalition government with so little debate and – let us be clear – with no mandate from the British people for their rise in VAT or immediate and deep spending cuts. Yes, there is plenty of discussion up and down the country about where the axe should fall on public services – as my opposite number Michael Gove has discovered. There are intense disputes, not least within the Conservative Party, about whether welfare reform can deliver the impact and savings claimed by Iain Duncan Smith. And there are very important arguments taking place about the universality of benefits, and the age at which pension-related entitlements should kick in.

These are all important debates. But the fundamental questions we face now – Is it right to be cutting billions of pounds from public services and taking billions of pounds out of family budgets this financial year and next? what will that do to jobs and growth? and ultimately, what will that mean for the deficit? – are almost ignored.

Yes, there are some important warning voices – Anatole Kaletsky, Paul Krugman, Lord Skidelsky, David Blanchflower to name a few – who have written powerful critiques on the comment pages of the broadsheets. But for the most part, the political and media consensus has dictated that the deficit is the only issue that matters in economic policy, that the measures set out in the Budget to reduce it are unavoidable, and that there is no alternative to the timetable the Budget set out....

So the first lesson I draw from history is to be wary of any British economic policy-maker or media commentator who tells you that there is no alternative or that something has to be done because the markets demand it. Adopting the consensus view may be the easy and safe thing to do, but it does not make you right and, in the long-term, it does not make you credible. We must never be afraid to stand outside the consensus – and challenge the view of the Chancellor, the Treasury, even the Bank of England Governor – if we believe them to be wrong.

But there is a second lesson too – which is also very pertinent at the present time for the Labour opposition and those of us who aspire to be the next Labour leader: it’s not enough to be right if you don’t win the argument. For – as Keynes found in 1925 and 1931 and Alan Walters found in 1990 – being right in the long run and well-judged by history is no great comfort.... [T]o sit back and wait for the pain to be felt is a huge trap for Labour... it is time for Labour to take on and win the argument with David Cameron, Nick Clegg, George Osborne and others who share their views.... [W]e cannot start waging the argument for a credible alternative path for growth, jobs, continued recovery and the eventual reduction of the deficit without first setting out why we believe the new government has got it so fundamentally wrong....

So let me turn to George Osborne’s speech and his triumphant espousal of the current consensus....

So first, is the current economic situation all Labour’s fault, the consequence irresponsible levels of public spending and borrowing in the early part of the last decade?... [I]t is a question of fact that we entered this financial crisis with low inflation, low interest rates, low unemployment and the lowest net debt of any large G7 country – and the second highest levels of foreign investment too.... [O]ur low debt position, our low inflation and low interest rates meant that we were the only government in post-war British history which – faced with recession and deflation – had both the will and the means to fight it through a classic Keynesian response... the effects of our actions are clear to see from the data on jobs, growth and the public finances from the first half of this year, before George Osborne’s ‘Emergency Budget’....

But rather than continue with a strategy that was working, George Osborne is doing the exact opposite. As the second storm looms on the horizon, everything he is doing is designed to suck money out of the economy and cut public investment, while his tax rises and benefit cuts will directly hit household finances at the worst possible time.... George Osborne was fond of saying – wrongly – that the Labour government had failed to fix the roof while the sun was shining. What he is now doing is the equivalent of ripping out the foundations of the house just as the hurricane is about to hit....

So what of George Osborne’s second contention – strongly supported by Nick Clegg – that the demand from the international money markets for fiscal consolidation is so strong that Britain and other countries must cut the deficit to avoid a ‘Greek-style’ financial crisis?... I do not have to tell this audience that what matters for credibility is not how tough politicians talk, but if their plans work and can be delivered..... Britain faces no difficulty servicing its debts as recent debt auctions have demonstrated – and the term structure of our debt is long thanks to the brilliant work of the Debt Management Agency. As US economist Brad DeLong said last month:

History teaches us that when none of the three clear and present dangers that justify retrenchment and austerity – interest-rate crowding-out, rising inflationary pressures on consumer prices, national overleverage via borrowing in foreign currencies – are present, you should not retrench.”

And yet in recent months, as Britain has followed the rest of Europe down a reckless commitment to immediate deficit reduction, we are now seeing very real worry in financial markets as fears of stagnation or even a double-dip recession grow....

Which brings us to the issue of George Osborne’s cautious optimism.... I would like him to point to the precedent from British economic history which says that, with slowing growth in our main trading partners and companies de-leveraging, it is possible for public sector retrenchment to stimulate private sector growth and job creation. The 1930s and 1980s proved the opposite.... For all George Osborne’s talk of ‘deficit-deniers’ – where is the real denial in British politics at the moment?... Against all the evidence, both contemporary and historical, he argues the private sector will somehow rush to fill the void left by government and consumer spending, and become the driver of jobs and growth.

This is ‘growth-denial’ on a grand scale.

It has about as much economic credibility as a Pyramid Scheme....

Then – having blamed the Labour government for his cuts plan, and insisted the markets are guiding his hand – George Osborne went on to make a further bold claim.... The Chancellor says that there is no alternative.... George Osborne includes in his charge Alistair Darling and David Miliband, who have suggested the lesser plan of halving the deficit over four years. I told Gordon Brown and Alistair Darling in 2009 that – whatever the media clamour at the time – even trying to halve the deficit in four years was a mistake. The pace was too severe to be credible or sustainable. As both history and market realities teach us, the danger of too rapid deficit reduction is that it proves counter-productive....

But whatever our competing visions for the economy, growth and deficit reduction, there is also a wider and more fundamental issue at stake which could be easily forgotten or postponed as we focus on how best to protect the current status quo in terms of growth, jobs and living standards.

It is the fairness of our society....

David Cameron has a narrow view of the role of the state – that it stifles society and economic progress. I have a wider view of the role of state – a coming together of communities through democracy to support people, to intervene where markets fail, to promote economic prosperity and opportunity.

He has a narrow view of justice – you keep what you own and whatever you earn in a free market free for all. My vision of a just society is a wider view of social justice that goes beyond equal opportunities, makes the positive case for fair chances, recognises that widely unequal societies are unfair and divisive and relies on active government and a modern welfare state to deliver fair chances for all.

Far from thinking that electoral success is based on the shedding or hiding of values, I believe we now need to champion those values and the importance of a fairer Britain – to show we are on peoples’ side after all.

Labour’s next leader needs a much stronger, clearer vision of the fairer Britain we will fight for – very different from the unfairness and unemployment the Coalition’s savage and immediate cuts will cause...

No, Our Excess Unemployment Today Is Not Structural

In three years, however--unless the Federal Reserve or the Obama administration take much stronger action than they are currently contemplating--it will be.

Mike Konczal:

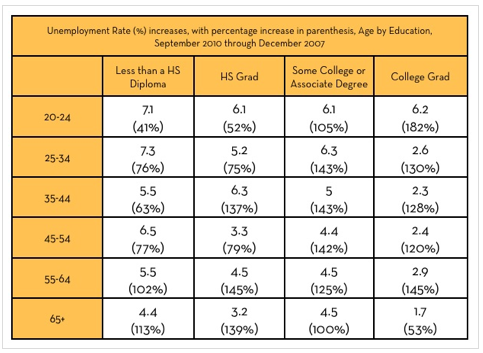

The Young, the Old, the Unemployed: Roosevelt Institute intern Charlie Eisenhood dug up this data on the unemployment rate by age and education.... September 2010.... December 2007 when the recession started.... Here is the difference between the two, along with the percent increase....

What jumps out for me? College educated 20-24 year olds have the highest percentage increase in unemployment. This should go against a structural unemployment story, as college educated people have the ‘freshest’ skills and incredibly high mobility. It’s worth pointing them out in particular because if their careers hit a rough spot, hysteresis sets in and they’ll have serious wage losses years down the road (see this classic White House blog post on the subject by Peter Orszag).

Their situation is also important because the crisis is often seen as a small deal for college educated workers.

The other thing that jumps out at me is that the unemployment rate for everyone 55-64 has more than doubled. One thing we aren’t talking about enough is that someone who is 60 and has been unemployed for a year isn’t going to find a decent job again. Other ways of looking at the labor search outcomes of 55-64 year olds are even more worrying. Why don’t we temporarily lower the retirement age, conditional on a bunch of hoops? Why don’t we give them some relief, rather than raising the retirement age (a subject likely to be at the center of the December debate), when 55-64 year olds have had such a large increase in unemployment?

Paul Krugman: British Fashion Victims

Paul Krugman:

British Fashion Victims: In the spring of 2010, fiscal austerity became fashionable. I use the term advisedly: the sudden consensus among Very Serious People that everyone must balance budgets now now now wasn’t based on any kind of careful analysis. It was more like a fad, something everyone professed to believe because that was what the in-crowd was saying.

And it’s a fad that has been fading lately, as evidence has accumulated that the lessons of the past remain relevant, that trying to balance budgets in the face of high unemployment and falling inflation is still a really bad idea. Most notably, the confidence fairy has been exposed as a myth. There have been widespread claims that deficit-cutting actually reduces unemployment because it reassures consumers and businesses; but multiple studies of historical record, including one by the International Monetary Fund, have shown that this claim has no basis in reality.

No widespread fad ever passes, however, without leaving some fashion victims in its wake. In this case, the victims are the people of Britain....

[T]here’s no question that Britain will eventually need to balance its books with spending cuts and tax increases. The operative word here should, however, be “eventually.” Fiscal austerity will depress the economy further unless it can be offset by a fall in interest rates. Right now, interest rates in Britain, as in America, are already very low, with little room to fall further. The sensible thing, then, is to devise a plan for putting the nation’s fiscal house in order, while waiting until a solid economic recovery is under way before wielding the ax. But trendy fashion, almost by definition, isn’t sensible — and the British government seems determined to ignore the lessons of history....

The British government’s plan is bold, say the pundits — and so it is. But it boldly goes in exactly the wrong direction. It would cut government employment by 490,000 workers — the equivalent of almost three million layoffs in the United States — at a time when the private sector is in no position to provide alternative employment. It would slash spending at a time when private demand isn’t at all ready to take up the slack. Why is the British government doing this? The real reason has a lot to do with ideology: the Tories are using the deficit as an excuse to downsize the welfare state. But the official rationale is that there is no alternative.

Indeed, there has been a noticeable change in the rhetoric of the government of Prime Minister David Cameron over the past few weeks — a shift from hope to fear. In his speech announcing the budget plan, George Osborne, the chancellor of the Exchequer, seemed to have given up on the confidence fairy — that is, on claims that the plan would have positive effects on employment and growth. Instead, it was all about the apocalypse looming if Britain failed to go down this route. Never mind that British debt as a percentage of national income is actually below its historical average; never mind that British interest rates stayed low even as the nation’s budget deficit soared, reflecting the belief of investors that the country can and will get its finances under control. Britain, declared Mr. Osborne, was on the “brink of bankruptcy.”

What happens now? Maybe Britain will get lucky, and something will come along to rescue the economy. But the best guess is that Britain in 2011 will look like Britain in 1931, or the United States in 1937, or Japan in 1997. That is, premature fiscal austerity will lead to a renewed economic slump. As always, those who refuse to learn from the past are doomed to repeat it.

"Mice with Fully Functioning Human Brains..."

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers