J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2098

February 10, 2011

And Will Wilkinson Eats His Wheaties...

WW on yet another of Michael Kinsley's mortal sins, Stephen Landsburg:

: LAST week, I posted a video of an impressive young man delivering a moving short speech in opposition to the attempt to add an amendment to Iowa's constitution outlawing gay marriage. Steven Landsburg, an economist at the University of Rochester, was not impressed.

In a video that’s begun to go viral, University of Iowa engineering student Zach Wahls attempts to refute this notion [that gay people, on average, are less successful as parents] without offering a shred of evidence beyond a single cherry-picked case (his own) to prove that children of gay parents sometimes turn out just fine (except, perhaps, for their ability to reason)...What’s particularly disturbing to me is all the chatter about how eloquent this kid is, as if eloquence in the service of intellectual misdirection were somehow something to be admired.

There are a number of things one might like to say to Mr Landsburg, but let me congratulate him instead for his inspiring opposition to fallacious arguments from anecdote. One may wonder, however, whether this commonplace error is among our society's most pressing problems, much less among our society's most serious epistemological failings.

I take it that Mr Wahls' problem, the problem he was addressing in his uplifting oration, is that a powerful political faction convinced of the essential evil of homosexuality by a magical book seeks to injure his family by voiding his mothers' marriage of its legal standing and stripping his family of the status and respect that flow from that.

The science-minded Mr Landsburg may be shocked to learn the assault on marriage equality in Iowa and elsewhere is not predicated upon the modest empirical hypothesis "that gay people, on average, are less successful as parents"; it is based on a conviction of faith that homosexuality is a sinful perversion inherently corrosive to the values that make healthy families possible. Mr Wahls' upstanding, A-student, Eagle-Scout character together with his normatively wholesome family life is sufficient to cast rational doubt on this rather sweeping article of faith.

Let's suppose, though, that there is a credible basis for the proposition "that gay people, on average, are less successful as parents", and that this has something to do with the gay-marriage debate we have been having here in Iowa. What then? Consider an analogy. There is evidence that people in dire poverty are, for a number of reasons, less "successful" as parents. Suppose some of us therefore proposed banning marriages between poor people. The first argument against this proposal is that the right to marry should not depend on membership in a class that is, on average, as successful at parenting as other classes. The second argument is that stripping poor people of the right to marry strips them of legal equality and what John Rawls, the great political philosopher, called "the social bases of self-respect". This harmful injustice would be suffered by the whole class marginalised by official discrimination, but it would be especially salient in the case of exemplary poor families clearly deserving of equal standing, recognition, and social esteem. The moving story of an exceptional family that would be harmed by the proposed codification of inequality draws our attention germanely toward the broader injustice such a law would create. Mr Wahls' primary argument seems to me to be of this sort. Again, this former logic instructor can see no sophistry in it.

Economists like Mr Landsburg specialise in the study of instrumental rationality. To act rationally in this sense is to take the means most conducive to one's ends. Sadly, means-ends rationality and epistemic rationality are often at odds. Fallacious arguments can be the best means to noble ends. If we were to concede, for the sake of argument, that Mr Wahls did fallaciously attempt to rebut a statistical argument with an anecdote, it may remain that he acted not "in the service of intellectual misdirection", but instead acted with exemplary rationality and morality by speaking eloquently in the service of justice. The kind of humanising anecdote Mr Wahls offered does in fact tend to elicit sympathy and weaken ill-founded prejudice. Maybe the relatively tolerant attitude of people with gay friends and family flows from some kind of statistical slip-up, but that's how we are. A rational rhetorician takes his audience's inclinations, rational or not, into account....

So what gives? My guess is that, like a number of right-leaning economists, Mr Landsburg has a regrettable tendency toward tone-deaf, context-dropping, contrarian provocation based on an unexamined assumption that this is what it means to be bravely rational. It is not. In any case, I think we can all agree that, other things equal, intellectual misdirection is not "something to be admired".

Will Wilkinson Ought to Be Better than This...

No, Will, Opinions of the Shape of the Earth Do Not Differ. The Earth Is Round. Global Warming Is a Serious Threat. Stimulative Monetary and Fiscal Policies Boost Output. The IPAB Will Reduce the Rate of Growth of Medicare Costs. Taxing High Cost Health Plans Will Put Downward Pressure on Health Costs.

Will Wilkinson:

: YESTERDAY, Ben Bernanke, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, appeared on Capitol Hill to field questions from the House Budget Committee. The committee's new Republican chairman, Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, pressed Mr Bernanke to defend the Fed's efforts to quicken recovery through it's latest round of "quantitative easing", citing "a sharp rise in a variety of key global commodity and basic material prices" as a herald of inflation. In his opening statement, Mr Ryan acknowledged that "these cost pressures have not yet been passed along to consumers"—emphasis on "yet"—before worrying aloud that Mr Bernanke and his Fed minions threaten to wreck the economy.

"Our currency should provide a reliable store of value—it should be guided by the rule of law, not the rule of men," Mr Ryan informed Mr Bernanke. "There is nothing more insidious that a country can do to its citizens than debase its currency". And who would disagree? Yet why all this hand-wringing about inflation now? Mr Bernanke sensibly pointed out that rising prices in global commodities markets reflect rising demand in emerging markets and, in some markets, constrained supply. American monetary policy? Not so much. Furthermore, inflation is low, and inflation expectations remain steady, as Mr Bernanke duly noted. Nevertheless, the breathless rhetoric of insidious currency debasement continues to spill forth even from sober, economically-literate Republicans such as Mr Ryan....

At a time when most economists saw deflation and long-term, Japanese-style stagnation as a far greater danger than inflation, and when high unemployment and below-target inflation indicated that monetary policy was too tight, Republicans were hyperventilating about "currency debasement" and denouncing the Fed's efforts to expand the money supply.

I think if we add to this the reinforcing influence of an especially simplistic strain of Austrian monetary theory, we have a fairly solid account of the source of Mr Ryan's inflated worries about inflation.

Yes, yes, conservatives: there is an analogous Donkeynomics (or whatever you'd call it) that combines cold-fusion Keynesianism, occult health-care cost-curve bending, green-energy magic beanism, etc. But today is Mr Ryan's day to shine.

Why oh why can't we have a better press corps?

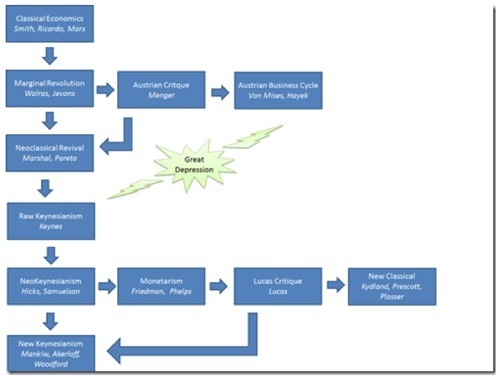

Karl Smith's Map of Macroeconomic Ideas

Greg ip Argues Against Those Convinced That America Today = Weimar Germany

GI:

Commodity prices: Inflation lessons from the Asian crisis | The Economist: ust as the plunge in the price of oil in 1998 did not signal deflationary pressure in America, its rise today does not signal inflationary pressure here, unless it works its way into expectations and wages, of which there’s no sign yet. (The 0.4% rise in hourly wages in January looks weird; for now, I’d discount it.) In fact, it could do the opposite: by draining more American purchasing power to overseas suppliers, higher oil prices leave less money to spend on stuff made in America. (America is a net food exporter so higher food prices are positive for American growth.) If the Fed were to tighten monetary policy today in response to Asia’s inflation problem, it could be the opposite of the mistake it made in 1998, compounding a deflationary shock at a time when the economy is significantly below potential.

Nick Rowe Is Puzzled by the War on Demand...

NR:

Worthwhile Canadian Initiative: The War on Demand, and the short-side rule.: Paul Krugman thinks the War on Demand is strange. I think it's weird. But I've got a different take on what's happening.

Let's start with some very basic theory. It takes two to trade. A buyer and a seller. If the buyer is willing and the seller is willing, there's a trade. If the buyer is not willing there's no trade. If the seller is not willing there's no trade. Quantity actually bought and sold is whichever is less: quantity demanded; or quantity supplied. Q=min{Qd,Qs}. That's the short side rule. The short side of the market determines the quantity traded.

Most people figure this out.

Now look around. Not just here and today, but anywhere, at any time. (OK, maybe not Cuba or North Korea.) Everywhere you look you see people trying to sell more. If you want to buy something, and are willing to hand over the money, you can nearly always buy it. The seller is almost always able and willing to sell you one. Very willing. Would you like to buy two? The short side of the market is nearly always the demand side.... If you increase quantity supplied, without increasing quantity demanded, nothing will happen. But if you increase quantity demanded, even if you don't increase quantity supplied, the quantity bought and sold will increase.... The policy conclusion is that we should almost always increase demand, at least a bit. It will almost always make us better off....

[W]hat's really strange is that we could ever get people to believe that demand is not the problem. For decades my job has been to teach students that, despite the evidence of their senses, and contrary to their hearsay of the heretical teachings of the Keynesian Cross, aggregate output is basically supply-determined. Which it is. Basically. Though short-run fluctuations in demand can and will cause short run fluctuations in aggregate output around an average level that is determined by the supply-side.

And, for once, the memories of their parents are actually supporting me in my job. Look what happened in the 1970's, when demand increased. Printing too much money and increasing demand really did cause inflation. It really didn't make us all richer. It didn't reduce unemployment. Now, just for once, we have to switch gears. These times are not normal. Just for once, the demand side really is the problem. Just for once, the overly obvious truth your senses are telling you really is the truth. Just for once, your parents' experience of the 1970's doesn't apply. Just for once, it really is OK to have a drink, even though you are a recovering alcoholic.

Who Are You Calling "We," Kemosabe?

Ezra Klein writes:

I'd add one caveat to DeLong's complaint that much of the reporting on the administration's internal disputes "reads like Hollywood celebrity journalism: 95 percent gossip, and perhaps 5 percent policy." There's a tendency to blame reporters for the stories they tell, and I'm not arguing with it. Ultimate responsibility lies with us...

There is something wrong with the "us" that Ezra uses here. Nobody calls his work "95 percent gossip, and perhaps 5 percent policy." Indeed, one of the alpha readers of my piece emailed me that: "indeed, on an average day you learn more of policy substance from Ezra Klein than from the entire national news staff of the New York Times..."

Ezra Klein:

Ezra Klein - Reporters aren't the only ones who like to gossip: This is a very good post by Brad DeLong on the substance of the debates between Peter Orszag and others in the Obama administration. I'm a bit more sympathetic to Orszag's position than Brad is, primarily because I think the administration essentially allowed the Republicans to define "deficit reduction " as "spending cuts," and that's going to have some bad consequences over the next few years. But you should read it rather than having me summarize it.

But I'd add one caveat to DeLong's complaint that much of the reporting on the administration's internal disputes "reads like Hollywood celebrity journalism: 95 percent gossip, and perhaps 5 percent policy." There's a tendency to blame reporters for the stories they tell, and I'm not arguing with it. Ultimate responsibility lies with us. And for my part, I stay away from doing tick-tocks of meetings and arguments unless I think there are serious implications for policy. But these sorts of gossipy, "so-and-so did such-and-such at this-or-that meeting" stories are often an honest reflection of what you get when you talk to the people who were in the meetings. Sometimes, it's actually difficult to get to the meat of the dispute because people are so much more interested in how the dispute was handled.

I guess that's natural. The people working in politics are human and they're ticked off by how they were treated, or by the way their boss spoke about them, or by something they heard someone else said about them, or by a meeting they weren't called into. Think about your job, which probably involves issues that are more important than office politics. Now think about how often you complain to your friends or spouse about office politics. It happens in the White House and Congress, too. That's not to say reporters don't spend too much time on it, or that they shouldn't toss a lot of that stuff out and tell the story lurking behind the anecdotes. But before coming to DC, I operated from the mental model that political actors were always begging reporters to cover the substance and reporters were always ignoring them and covering quarrels. To a degree I find disappointing, that's not really true.

I guess the more positive spin on all this is that it's important for administrations to be well managed and thus these stories actually do get at something important, which is that management has broken down and the White House is functioning poorly. That probably does have consequences for policy, though I think the consequences are often overstated by the people involved. If the administration's economic policy process had been 30 percent more collegial and professional, would our economic policy be any different today? I'm skeptical.

February 9, 2011

Liveblogging World War II: February 10, 1941

Prime Minister Winston Churchill instructs General Wavell to give a higher priority to aiding Greece than in exploiting the victories in the Western Desert to secure North Africa for the allies.

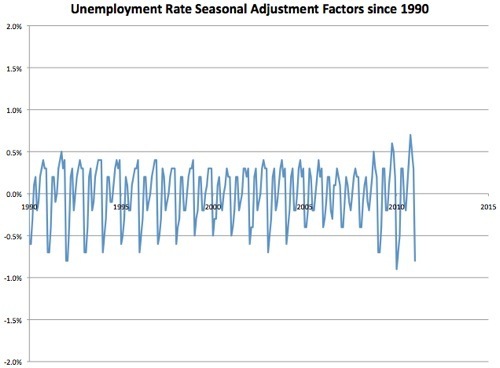

No. I Do Not Believe in the BLS's Seasonal Adjustment Filter. Why Do You Ask?

Put me down as somebody who does not believe that the seasonal factor in the unemployment rate is twice as big today as it was four short years ago, or was half as big four short years ago as it was in the early 1990s...

Not that I am complaining about the BLS, you understand. If I could do better, they would already have done better. Nevertheless this is a source of nervousness...

Dean Baker: Wall Street Journal Finds Evidence that Employers Cannot Find Qualified Staff for Top Management Positions

DB:

Wall Street Journal Finds Evidence that Employers Cannot Find Qualified Staff for Top Management Positions | Beat the Press: The Wall Street Journal ran a piece on how some companies are unable to fill positions even when more than 14 million workers are unemployed. The article indicates that the management personnel used as sources are either not competent or not being truthful. All the people used as sources for the article complained that they were unable to find qualified workers. For example, Josh Williams, the chief executive of Gowalla, a social networking start-up, is quoted complaining that: "most people we want are employed somewhere already. We don't get a lot of applications coming in."

The way employers are supposed to deal with this situation is to offer a higher wage than their competitors in order to attract away good workers. Apparently Mr. Williams has not thought of this approach. Later, the article comments on the experience of Toll Brothers Inc. a major builder. It cites a senior vice president of human resources, who claims that it has taken six months to find qualified applicants for some of its IT and Web developer openings. Here also, raising the offered wage likely would have reduced the search time substantially. It will always be the case that employers will have difficulty attracting skilled workers to positions where they are offering below market wages. This seems to be the problem identified in this article, not a lack of qualified workers.

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers