J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2101

February 7, 2011

Mark Thoma: Prepared for the Worst

Mark Thoma explains why he is still looking at the lower tail:

Economist's View: The Slow Recovery of Unemployment: I don't like to make economic forecasts. Though I do it on occasion, I generally leave that to Tim Duy -- he's much more of a data grubber than I am so he's better at it anyway. I do try to comment on what data says when it's released, mostly at MoneyWatch, but I don't generally consider those to be formal forecasts of where the economy is headed. There's a good reason why I try to avoid forecasts. In the past, whenever I've tried to predict the path the economy would take, I've found myself reading subsequent data releases in a way that supports the forecast. I think that once you make a forecast, it affects your objectivity, and I think that applies generally, not just to me.

Perhaps that's why I'm feeling more and more alone in talking about the current state of the economy.... When people say, for example, that there's nothing in the latest employment report to change the relatively optimistic forecasts they've made recently, I try to say that there's nothing in the data to reject the alternative forecast either, i.e. that we are still headed for a very slow recovery of employment. Whatever your null hypothesis or prior beliefs were, the latest data did little to change that outlook.... I am very worried that we are, for all intents and purposes, about to abandon the millions who are still unemployed. Once we conclude that a robust recovery is underway, we will turn our attention to other things....

I fully understand the desire to have a perfect landing, to get policy just right. But just right when the costs of unemployment are so much higher than the costs of inflation means that we should bias policy toward the unemployment problem. If we are going to make a mistake, it should be too much employment, and the inflation that comes with it, rather than too little.

However, with the inflation hawks writing almost daily in the WSJ and elsewhere that we need to raise interest rates immediately to avoid inflation, and with all of the pressure to address the budget deficit, if anything the bias in policy seems to be in the other direction....

Until I am sure that the economy is on firmer footing than it's on now, and that employment prospects have improved substantially, I will continue to be the one who pushes back against optimistic reading of the data. And I will make no apologies for it beyond what I've said here.

Interest Rates Rise Not When the Deficit Outlook Gets Worse But Rather When It Looks Like the Economy Will Improve More Rapidly

The point? We are still very, very far away from a world in which fear of a future government-debt crisis is raising the cost of capital to businesses. It is slack demand and fear that it will continue that has pushed up the cost of capital to private businesses--the cost of capital to the government remains astonishingly low, and correlated with little other than the medium-term demand-driven price-level outlook.

Jonathan Cohn: Why Friends Really Don't Let Friends Support Republicans

JC on the Republican root-and-branch opposition to RomneyCare:

The Pathology Of Repeal: Yesterday I somewhat cynically suggested that Republicans were not interested in actually altering the individual mandate of the Affordable Care Act. Today, Mitch McConnell says he's not interested in altering anything about the law:

Republicans aren't likely to bury the hatchet with President Obama over the healthcare reform act, their Senate leader said Friday. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), fresh off an unsuccessful vote on Wednesday to repeal healthcare reform, said not to expect Republicans to strike any agreements with the president. "I think it’s clear that this is an area upon which we are not likely to reach any agreements with the president," McConnell said on conservative pundit Laura Ingraham's radio show.

If this was a dispute about policy, of course, Republicans would be willing to pursue alterations. Democrats didn't like the Bush tax cuts, but if Bush had been willing to tighten up some tax loopholes, maybe lose the estate tax cuts, then they'd have been happy to entertain some alterations. While they may not have liked the law, they could surely imagine ways to improve it that could meet with bipartisan approval, especially given President Obama's professed willingness to negotiate changes. They could do so while still pursuing their preferred model of health care reform.

But the Affordable Care Act has become tot he right a symbolic totem that has little to do with actual policies. Its very existence is an enduring emotional wound. Greg Sargent writes:

Consider this article by the Post's Amy Goldstein, which quotes a range of Tea Partyers talking about the repeal of "Obamacare" in fervent and even messianic tones. They are prepared to invest years in realizing this goal. It's clear that for an untold number of base GOP voters, major questions about political and national identity are now bound up in repeal. An entire industry has been created around this new Holy Grail. There is now a big stake for a whole range of actors, some less reputable than others, in keeping millions of Americans emotionally invested in the idea that total repeal is not only achievable, but absolutely necessary to preserving their liberty and the future of the republic.

The GOP is operating not on the basis of some analysis of public policy but from a sheer pathology.

Hoisted from the Archives: Nicollo Machievelli Begs for a Job

Nicollo Machiavelli, kept sane only by his library, tries to figure out how to get another White House job:

Machiavelli: Letter to Vettori: I am living on my farm, and since I had my last bad luck, I have not spent twenty days, putting them all together, in Florence. I have until now been snaring thrushes with my own hands. I got up before day, prepared birdlime, went out with a bundle of cages on my back, so that I looked like Geta when he was returning from the harbor with Amphitryon's books. I caught at least two thrushes and at most six. And so I did all September. Then this pastime, pitiful and strange as it is, gave out, to my displeasure. And of what sort my life is, I shall tell you.

I get up in the morning with the sun and go into a grove I am having cut down, where I remain two hours to look over the work of the past day and kill some time with the cutters, who have always some bad-luck story ready, about either themselves or their neighbors. And as to this grove I could tell you a thousand fine things that have happened to me, in dealing with Frosino da Panzano and others who wanted some of this firewood. And Frosino especially sent for a number of cords without saying a thing to me, and on payment he wanted to keep back from me ten lire, which he says he should have had from me four years ago, when he beat me at cricca at Antonio Guicciardini's. I raised the devil, and was going to prosecute as a thief the waggoner who came for the wood, but Giovanni Machiavelli came between us and got us to agree. Batista Guicciardini, Filippo Ginori, Tommaso del Bene and some other citizens, when that north wind was blowing, each ordered a cord from me. I made promises to all and sent one to Tommaso, which at Florence changed to half a cord, because it was piled up again by himself, his wife, his servant, his children, so that he looked like Gabburra when on Thursday with all his servants he cudgels an ox. Hence, having seen for whom there was profit, I told the others I had no more wood, and all of them were angry about it, and especially Batista, who counts this along with his misfortunes at Prato.

Leaving the grove, I go to a spring, and thence to my aviary. I have a book in my pocket, either Dante or Petrarch, or one of the lesser poets, such as Tibullus, Ovid, and the like. I read of their tender passions and their loves, remember mine, enjoy myself a while in that sort of dreaming. Then I move along the road to the inn; I speak with those who pass, ask news of their villages, learn various things, and note the various tastes and different fancies of men. In the course of these things comes the hour for dinner, where with my family I eat such food as this poor farm of mine and my tiny property allow. Having eaten, I go back to the inn; there is the host, usually a butcher, a miller, two furnace tenders. With these I sink into vulgarity for the whole day, playing at cricca and at trich-trach, and then these games bring on a thousand disputes and countless insults with offensive words, and usually we are fighting over a penny, and nevertheless we are heard shouting as far as San Casciano. So, involved in these trifles, I keep my brain from growing mouldy, and satisfy the malice of this fate of mine, being glad to have her drive me along this road, to see if she will be ashamed of it.

On the coming of evening, I return to my house and enter my study; and at the door I take off the day's clothing, covered with mud and dust, and put on garments regal and courtly; and reclothed appropriately, I enter the ancient courts of ancient men, where, received by them with affection, I feed on that food which only is mine and which I was born for, where I am not ashamed to speak with them and to ask them the reason for their actions; and they in their kindness answer me; and for four hours of time I do not feel boredom, I forget every trouble, I do not dread poverty, I am not frightened by death; entirely I give myself over to them.

And because Dante says it does not produce knowledge when we hear but do not remember, I have noted everything in their conversation which has profited me, and have composed a little work On Princedoms, where I go as deeply as I can into considerations on this subject, debating what a princedom is, of what kinds they are, how they are gained, how they are kept, why they are lost. And if ever you can find any of my fantasies pleasing, this one should not displease you; and by a prince, and especially by a new prince, it ought to be welcomed. Hence I am dedicating it to His Magnificence Giuliano. Filippo Casavecchia has seen it; he can give you some account in part of the thing in itself and of the discussions I have had with him, though I am still enlarging and revising it.

You wish, Magnificent Ambassador, that I leave this life and come to enjoy yours with you. I shall do it in any case, but what tempts me now are certain affairs that within six weeks I shall finish. What makes me doubtful is that the Soderini we know so well are in the city, whom I should be obliged, on coming there, to visit and talk with. I should fear that on my return I could not hope to dismount at my house but should dismount at the prison, because though this government has mighty foundations and great security, yet it is new and therefore suspicious, and there is no lack of wiseacres who, to make a figure, like Pagolo Bertini, would place others at the dinner table and leave the reckoning to me. I beg you to rid me of this fear, and then I shall come within the time mentioned to visit you in any case.

I have talked with Filippo about this little work of mine that I have spoken of, whether it is good to give it or not to give it; and if it is good to give it, whether it would be good to take it myself, or whether I should send it there. Not giving it would make me fear that at the least Giuliano will not read it and that this rascal Ardinghelli will get himself honor from this latest work of mine. The giving of it is forced on me by the necessity that drives me, because I am using up my money, and I cannot remain as I am a long time without becoming despised through poverty. In addition, there is my wish that our present Medici lords will make use of me, even if they begin by making me roll a stone; because then if I could not gain their favor, I should complain of myself; and through this thing, if it were read, they would see that for the fifteen years while I have been studying the art of the state, I have not slept or been playing; and well may anybody be glad to get the services of one who at the expense of others has become full of experience. And of my honesty there should be no doubt, because having always preserved my honesty, I shall hardly now learn to break it; and he who has been honest and good for forty-three years, as I have, cannot change his nature; and as a witness to my honesty and goodness I have my poverty.

I should like, then, to have you also write me what you think best on this matter, and I give you my regards. Be happy.

In Which Suresh Naidu Visits the New Jerusalem...

Luke the Physician wrote:

[T]he multitude of them that believed were of one heart and of one soul: neither said any of them that ought of the things which he possessed was his own; but they had all things common.... Neither was there any among them that lacked: for as many as were possessors of lands or houses sold them, and brought the prices of the things that were sold, and laid them down at the apostles' feet: and distribution was made unto every man according as he had need...

But it was not just on the consumption side: it was on the production side as well:

Agabus... [declared] there should be great dearth... which came to pass in the days of Claudius Caesar. Then the disciples, everyone according to his ability, determined to send relief unto the brethren which dwelt in Judaea, which also they did, and sent it to the elders by the hands of Barnabas and Saul...

Suresh Naidu reads G.A. Cohen and writes:

The Slack Wire: Redistributive Justice and Wonkery: There are murmurs on the intertubes about redistributive justice... related murmurs about the lack of seriously left-wing blogs.... I have just finished reading G.A. Cohen's "Rescuing Justice and Equality", which is essentially a critique of Rawls from the left. The point is that the Rawlsian difference principle legitimizes a lot of inequality that runs counter to some of our ethical intuitions.... Rawls' argument allows talented people to hold back exercising their talents until they are compensated enough.... Cohen's book suggests the superstar doctor monster, who has medical skills and talents that are very valuable to the poorest people, but demands so much compensation that the resulting inequality is horrific. Liberals have no criticism of the doctor, but socialists think the doctor is fundamentally an unethical jerk.... Socialists can believe that the doctor's lack of solidarity, despite material abundance, depends on the presence of capitalist institutions that encourage rapacity, and criticize that kind of selfish behavior....

At the core of Cohen's argument is this "trilemma", that it is impossible to have all three of efficiency, equality, and free allocation of labor. Basically any two of these precludes the third (Stalinist rule gets you the first two and Rawlsian justice gets you 1 and 3, and nobody really wants the homogeneously poor society entailed by dropping 1). In economics this is formalized in the Mirrlees optimal income taxation problem... [in which] talented people should not be taxed because they produce a large amount per hour worked. A lot of the knock-on early Mirrlees-derived literature had a zero top-tax rate at the optimum (but recent literature weakens this, basically because the income distribution is potentially unbounded above and has fat tails).

Rawls is ok with that kind of inequality.... So I don't think that Rawlsianism is a socialist principle of distributive justice. In fact it is the bedrock philosophy of left-liberal and social democratic interventions.... Rawlsianism is also therefore the bedrock philosophy of the policy wonk, who thinks that social justice is a property of states alone and not a whole suite of institutions and behaviors.... Hence the endless key-punching on the details and consequences of this or that Democratic proposal, but little dialogue with social movements, political campaigns that are outside the government (like labor and tenant organizations), or radically non-neoclassical visions of the economy. Make no mistake, I enjoy and benefit from it, but I don't think its particularly agenda-setting for the left.

Cohen offers a way out of the trilemma by suggesting that we expand the domain of justice to include labor-supply decisions and preferences more generally.... Cohen thinks about egalitarianism as an ethic, not just as a property of government. He draws on feminist (and I would add anarchist) ideas that "the personal is political", that people's preferences and values are objects of justice, and that we can have a free allocation of labor that maintains distributive justice if people have ideals and ethics of conduct that sustain egalitarian distributions. So we should have grounds for criticizing the bankers and doctors for demanding so much money to do their jobs... [we should] organize for values and ethics (and deliberative politics that let us collectively construct and enforce these values and ethics across a variety of social sites) that sustain a society where anybody with talent would feel ashamed and ridiculous for demanding large amounts of compensation.

The idea that talented labor should demand a high wage is repugnant to socialist ethics; as Cohen eloquently states "labor, like love, should be freely given". As a scholar, the gift (and status) based economy of tenured academia is a lovely alternative allocation mechanism for human labor (and the reason I shouldn't start blogging for another 7 years)....

Bringing this all back together, I think I want to make two points about Rawlsian social democracy: a) It is quite compatible with a large amount of inequality and this is partially because b) it restricts the domain of criticism to the wonk playground of state policy. The Cohen book has the seed of a criticism of social democratic bloggers; it is against both the amount of inequality that Rawlsian social democracy (the kind favored by Yglesias et al.) allows as well as the narrow spectrum of technocratic state-centered instruments by which any extra inequality is addressed, So I think Freddie deBoer's criticism of the left-liberal wonk blog stands, and is part of the general libertarian socialist critique of the social democratic left.

I think the weakest point of Suresh's argument is something he recognizes: the "(and status)" in his description of the economy of tenured academia, which elicits enormous amounts of work effort with relatively small (and not very important) amounts of material inequality.

You can have a situation in which people work hard because they really want to be, as somebody-or-other once said, "one of the three international economists in the top ten" and otherwise everybody dresses in identical blue overalls and eats sustainably-farmed root vegetables.

You can have a situation in which people work hard because they want to go on the meal plan at The French Laundry and want the worst bottle of wine that ever touches their lips to be the 2005 Petit Bocq from St. Estephe.

The first tends to be zero sum. The second is positive sum. Perhaps you can argue that a society can value average the high consumption produced by general prosperity while scorning the pleasures brought by high consumption produced by inequality, but that would be a neat trick to accomplish when the fires of ideology begin to die down.

Indeed, even by the time St. Luke wrote his narrative down, the from-each-according-to-his-ability-to-each-according-to-his-need ethic of the first generation was but a memory, never again to be seen in this fallen Sublunary sphere...

Time to Start Teaching the Undergraduates About Business Cycles

How to begin? What is the vision I went them to take away and remember?

How about this:

For some reason--it can be any of a large number of reasons, this time it is the blowback from excessive leverage and irrational exuberance, but it can be for any of a large number of reasons--the people in the economy decide that they are spending too much on currently-produced goods and services. They decide that they want to spend less and so build up their holdings of financial assets. People cut back on their spending on currently-produced goods and services, planning to use the margin they will create between income and spending to build up their holdings of financial assets.

The problem is that one person's spending is another person's production, and that one person's production is another person's income. Businesses see demand for what they produce fall off. They see their inventories of unsold goods rise. Businesses thus lay workers off in order to avoid making even more stuff that they cannot sell: production falls. And as production falls businesses stop paying the workers they have laid off: incomes fall.

People spend what they had planned on currently-produced goods and services. But they find that their incomes are less than they had thought they would be. Thus the margin they had hoped to create between their incomes and their spending does not exist. People find that they have not managed to carry out their plans to build up their holdings of financial assets. But they still want to. So people try to cut back on their spending on currently produce goods and services yet again to build up their holdings of financial assets. And the process repeats. Spending, production, and incomes fall again.

Why don't spending and production and incomes and production fall to zero in this downward spiral?

Because at some point incomes drop so low that people give up on the idea of building up their stocks of financial assets.

They still would like to build up their stocks of financial assets--if their incomes were normal. But keeping their standard of living from falling too much becomes a higher priority. The economy settles down at a spot where spending on currently-produced goods and services once again equals production and income. If finds itself at a short-run macroeconomic equilibrium where inventories are neither rising and causing businesses to fire more workers or falling and causing businesses to hire more workers. This equilibrium, however, has a lot of unemployment: a lot of unemployed workers looking for jobs, and few vacancies looking for workers.

How bad do things get as a result of this collective decision to try to build up stocks of financial assets?

For that we need to build an economic model And we need to build different economic model then the production function base growth economic model we been dealing with over the past two weeks...

February 5, 2011

Jack Stuef: Donald Rumsfeld Says "Nothing Is My Fault"

JF:

Donald Rumsfeld: It’s Not My Fault: Donald Rumsfeld.... Abu Ghraib? Not his fault, but he really wanted to resign over it and feels very emo that big meanie Bush wouldn’t let him. Initial troop levels? Not his fault, nobody in the military ever asked him for more troops. Guantanamo? Not his fault the jail existed, and actually he made sure there was less torture and fewer prisoners. Hmm, anything we’re forgetting here? Oh, that one war. What was it called again? Anyway, not his fault, Bush came to him about Iraq before the U.S. even invaded Afghanistan....

Just 15 days after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, President George W. Bush invited his defense secretary, Donald H. Rumsfeld, to meet with him alone in the Oval Office. According to Mr. Rumsfeld’s new memoir, the president leaned back in his leather chair and ordered a review and revision of war plans — but not for Afghanistan, where the Qaeda attacks on New York and Washington had been planned and where American retaliation was imminent. Rummy says Defense was preparing for offense on Afghanistan at the time, but Bush asked him to be “creative.” Creative! Perhaps the military could stage a production of Grease for the people of Iraq before taking a bow and dropping a bomb on them?...

[A]t the end of the same Oval Office session in which Mr. Bush asked for an Iraq war plan, Mr. Rumsfeld recounts, the president asked about Mr. Rumsfeld’s son, Nick, who struggled with drug addiction, had relapsed and just days before had entered a rehabilitation center. The president, who has written of his own battles to overcome a drinking problem, said that he was praying for Mr. Rumsfeld, his wife, Joyce, and all their children. “What had happened to Nick — coupled with the wounds to our country and the Pentagon — all started to hit me,” Mr. Rumsfeld writes. “At that moment, I couldn’t speak. And I was unable to hold back the emotions that until then I had shared only with Joyce.”

Ah, there you have it. Rumsfeld could have said:

What the f--- are you talking about going to war with Iraq for? Our country was just attacked by a foreign terrorist organization we need to go try to destroy. Iraq has nothing to do with this. Aren’t you more concerned with winning this war we haven’t even begun yet?

But instead, his son had done some drugs. Sure thing, Rumsfeld. Perfectly good excuse. You should drop some leaflets on the families of people, American and Iraqi, whose children have died in that war. “Sorry, my son was doing drugs. I was emotional at the time. Not my fault.”

Do Not Pass the Turing Test. Do Not Collect $200...

Charlie Stross examines the new, smarter spam:

On not passing the Turing Test: Spam: we hates it.... Sometimes it's a little hard to spot.... This one came up on an earlier topic (Where's Charlie?) half an hour ago:

kuaför malzemeleri | February 5, 2011 12:49 | Reply

58:

the world's oldest person as of yesterday now lives a few miles from me in Georgia. Besse Cooper, aged 114 years, 159 days, (born August 26, 1896) was a former schoolteacher who married in 1924 and has 4 children, 11 grandchildren, 15 great-grandchildren and 1 g'g'grandchild. She has credited her longevity to rtyh

How did I determine that it was spam?

Clue 1: The posting seemed suspiciously disconnected from the topic of discussion. In fact, it turns out to be a cut'n'paste job of EH's comment #52, earlier in the thread. (If I'd noticed the earlier comment it'd have been "case closed" on the spot, but EH posted his bit four days ago.)

Clue 2: The posting ended in random characters (A common trick used by spammers to fool Bayesian spam-spotting tools that identify duplicate postings).

Clue 3: The poster's email address "necati.turan@windowslive.com" does not match their user name "kuaför malzemeleri".

Clue 4: Googling "kuaför malzemeleri" confirmed that the name is a googleable term in Turkish.

Clue 5: Google language tools then translated "kuaför malzemeleri" from Turkish to English as "hairdressing supplies".

QED.

Anyway. I've noticed that some of you don't always use your real names when posting comments here. If you want to avoid being accidentally misidentified as a Turkish hairdressing supplies spammer, bear in mind the clues that lead me to diagnose that a comment is spam and avoid leaving them.

This lesson bought to you by Officer Friendly of the Turing Police.

Is the Economic System Self-Adjusting ?

Tom Walker quotes John Maynard Keynes from 1934:

Ecological Headstand: Is the Economic System Self-Adjusting ?: I was asked recently to take part in a discussion among English economists on the problem of poverty in the midst of potential plenty, which none of us can deny is the outstanding conundrum of today. We all agreed that, whatever the best remedy may be, we must reject all those alleged remedies that consist, in effect, in getting rid of the plenty. It may be true, for various reasons, that as the potential plenty increases, the problem of getting the fruits of it distributed to the great body of consumers will present increasing difficulties. But it is to the analysis and solution of these difficulties that we must direct our minds. To seek an escape by making the productive machine less productive must be wrong. I often find myself in favor of measures to restrict output as a temporary palliative or to meet an emergency. But the temper of mind that turns too easily to restriction is dangerous, for it has nothing useful to contribute to the permanent solution. But this is another way of saying that we must not regard the conditions of supply -— that is to say, our facilities to produce -— as being the fundamental source of our troubles. And, if this is agreed, it seems to follow that it is the conditions of demand that our diagnosis must search and probe for the explanation.

Up to this point of the argument, as I have said, we were all in substantial agreement. Each one of us was ready to find the major part of our explanation in some factor that relates to the conditions of demand. But, though we all started out in the same direction, we soon parted company into two main groups. What made the cleavage that thus divided us?

On the one side were those who believed that the existing economic system is in the long run self-adjusting, though with creaks and groans and jerks, and interrupted by time-lags, outside interference and mistakes. One adherent of this school of thought laid stress on the increasing difficulty of rapid self-adjustment to change in an environment where population and markets are no longer expanding rapidly, Another stressed the growing tendency for outside interference to hinder the processes of self-adjustment, while a third stressed the effect of business mistakes under the influence of the uncertainty and the false expectations caused by the faults of post-war monetary systems. These economists did not, of course, believe that the system is automatic or immediately self-adjusting, but they did maintain that it has an inherent tendency towards self-adjustment, if it is not interfered with, and if the action of change and chance is not too rapid.

Those on the other side of the gulf, however, rejected the idea that the existing economic system is, in any significant sense, self-adjusting. They believed that the failure of effective demand to reach the full potentialities of supply, in spite of human psychological demand being immensely far from satisfied for the vast majority of individuals, is due to much more fundamental causes. One of them stressed the great inequality of incomes, which causes a separation between the power to consume and the desire to consume. Another believed that the great resources at the disposal of the entrepreneur are a chronic cause of his setting up plant capable of producing more than the limited resources of the consumer can absorb. A third, not disagreeing with these two, demanded some method of increasing consumer power so as to overcome the difficulties they pointed out.

The gulf between these two schools of thought is deeper, I believe, than most of those on either side of it realize. On which side does the essential truth lie?

The strength of the self-adjusting school depends on its having behind it almost the whole body of organized economic thinking and doctrine of the last hundred years. This is a formidable power. It is the product of acute minds and has persuaded and convinced the great majority of the intelligent and disinterested persons who have studied it. It has vast prestige and a more far-reaching influence than is obvious. For it lies behind the education and the habitual modes of thought, not only of economists but of bankers and business men and civil servants and politicians of all parties. The essential elements in it are fervently accepted by Marxists. Indeed, Marxism is a highly plausible inference from Ricardian economics that capitalistic individualism cannot possibly work in practice. So much so, that, if Ricardian economics were to fall, an essential prop to the intellectual foundations of Marxism would fall with it.

Thus, if the heretics on the other side of the gulf are to demolish the forces of nineteenth-century orthodoxy —- and I include Marxism in orthodoxy equally with laissez-faire, these two being the nineteenth-century twins of Say and Ricardo—they must attack them in their citadel. No successful attack has yet been made. The heretics of today are the descendants of a long line of heretics who, overwhelmed but never extinguished, have survived as isolated groups of cranks. They are deeply dissatisfied. They believe that common observation is enough to show that facts do not conform to the orthodox reasoning. They propose remedies prompted by instinct, by flair, by practical good sense, by experience of the world —- half-right, most of them, and half-wrong. Contemporary discontents have given them a volume of popular support and an opportunity for propagating their ideas such as they have not had for several generations. But they have made no impression on the citadel. Indeed, many of them themselves accept the orthodox premises; and it is only because their flair is stronger than their logic that they do not accept its conclusions,

Now I range myself with the heretics. I believe their flair and their instinct move them towards the right conclusion. But I was brought up in the citadel and I recognize its power and might. A large part of the established body of economic doctrine I cannot but accept as broadly correct. I do not doubt it. For me, therefore, it is impossible to rest satisfied until I can put my finger on the flaw in the part of the orthodox reasoning that leads to the conclusions that for various reasons seem to me to be inacceptable. I believe that I am on my way to do so. There is, I am convinced, a fatal flaw in that part of the orthodox reasoning that deals with the theory of what determines the level of effective demand and the volume of aggregate employment; the flaw being largely due to the failure of the classical doctrine to develop a satisfactory and realistic theory of the rate of interest.

Put very briefly, the point is something like this. Any individual, if be finds himself with a certain income, will, according to his habits, his tastes and his motives towards prudence, spend a portion of it on consumption and the rest he will save. If his income increases, he will almost certainly consume more than before, but it is highly probable that he will also save more. That is to say, he will not increase his consumption by the full amount of the increase in his income. Thus if a given national income is less equally divided, or if the national income increases so that individual incomes are greater than before, the gap between total incomes and the total expenditure on consumption is likely to widen. But incomes can be generated only by producing goods for consumption or by producing goods for use as capital. Thus the gap between total incomes and expenditure on consumption cannot be greater than the amount of new capital that it is thought worth while to produce. Consequently, our habit of withholding from consumption an increasing sum as our incomes increase means that it is impossible for our incomes to increase unless either we change our habits so as to consume mote or the business world calculates that it is worth while to produce more capital goods. For, failing both these alternatives, the increased employment and output, by which alone increased incomes can be generated, will prove unprofitable and will not persist.

Now the school that believes in self-adjustment is, in fact, assuming that the rate of interest adjusts itself more or less automatically, so as to encourage, just the right amount of production of capital goods to keep our incomes at the maximum level that our energies and our organization and our knowledge of how to produce efficiently are capable of providing. This is, however, pure assumption. There is no theoretical reason for believing it to be true. A very moderate amount of observation of the facts, unclouded by preconceptions, is sufficient to show that they do not bear it out. Those, standing on my side of the gulf, whom I have ventured to describe as half-right and half-wrong, have perceived this; and they conclude that the only remedy is for us to change the distribution of wealth and modify our habits in such a way as to increase our propensity to spend our incomes on current consumption. I agree with them in thinking that this would be a remedy. But I disagree with them when they go further and argue that it is the only remedy. For there is an alternative, namely, to increase the output of capital goods by reducing the rate of interest and in other ways.

When the rate of interest has fallen to a very low figure and has remained there sufficiently long to show that there is no further capital construction worth doing even at that low rate, then I should agree that the facts point to the necessity of drastic social changes directed towards increasing consumption. For it would be clear that we already had as great a stock of capital as we could usefully employ.

Even as things are, there is a strong presumption that a greater equality of incomes would lead to increased employment and greater aggregate income. But hitherto the rate of interest has been too high to allow us to have all the capital goods, particularly houses, that would be useful to us. Thus, at present, it is important to maintain a careful balance between stimulating consumption and stimulating investment. Economic welfare and social well-being will be increased in the long run by a policy that tends to make capital goods so abundant that the reward that can be gained from owning them falls to so modest a figure as to be no longer a serious burden on anyone. The right course is to get rid of the scarcity of capital goods —- which will rid us at the same time of most of the evils of capitalism -— while also moving in the direction of increasing the share of income failing to those whose economic welfare will gain most by their having the chance to consume more.

None of this, however, will happen by itself or of its own accord. The system is not self-adjusting, and, without purposive direction, it is incapable of translating our actual poverty into our potential plenty.

If the basic system of thought on which the orthodox school relies is in its essentials unassailable, then there is no escape from their broad conclusions, namely, that, while there are increasingly perplexing problems and plenty of opportunities to make disastrous mistakes, yet nevertheless we must keep our heads and depend on the ultimate soundness of the traditional teaching —- the proposals of the heretics, however plausible and even advantageous in the short run, being essentially superficial and ultimately dangerous. Only if they are successfully attacked in the citadel can we reasonably ask them to look at the problem in a radically new way.

Meanwhile, I hope we shall await, with what patience we can command, a successful outcome of the great activity of thought among economists today —- a fever of activity such as has not been known for a century. We are, in my very confident belief —- a belief, I fear, shared by few, either on the right or on the left —- at one of those uncommon junctures of human affairs where we can be saved by the solution of an intellectual problem, and in no other way. If we know the whole truth already, we shall not succeed indefinitely in avoiding a clash of human passions seeking an escape from the intolerable. But I have a better hope.

Reprinted from The New Republic, February 20, 1985, pp. 85—87. The Editorial Board of the Nebraska Journal of Economics and Business wishes to express its appreciation to the Editors of The New Republic for their kind permission to reprint the above article by John Maynard Keynes.

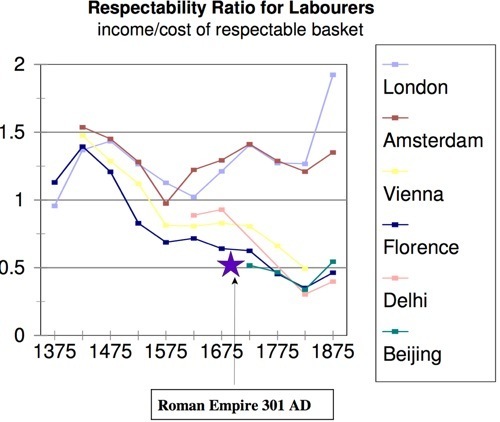

How Rich Was the Roman Empire?

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers