J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2100

February 8, 2011

Hudson Bay Still Not Frozen Solid...

NSIDC:

Arctic Sea Ice News & Analysis:

Arctic sea ice extent averaged over January 2011 was 13.55 million square kilometers (5.23 million square miles). This was the lowest January ice extent recorded since satellite records began in 1979. It was 50,000 square kilometers (19,300 square miles) below the record low of 13.60 million square kilometers (5.25 million square miles), set in 2006, and 1.27 million square kilometers (490,000 square miles) below the 1979 to 2000 average.

Ice extent in January 2011 remained unusually low in Hudson Bay, Hudson Strait (between southern Baffin Island and Labrador), and Davis Strait (between Baffin Island and Greenland). Normally, these areas freeze over by late November, but this year Hudson Bay did not completely freeze over until mid-January. The Labrador Sea remains largely ice-free.

Robert Kuttner on the Obama Puzzle

RK:

Unequal to the Moment: How do we explain... the inversion of a Franklin D. Roosevelt moment into a new period dominated by the corporate elite and the far right?.... The first batch of books from relatively friendly analysts of Obama's presidency falls into two broad categories.... Jonathan Alter, Richard Wolffe, Bob Woodward, and David Remnick... cut him a huge amount of slack. He was, after all, facing a severe recession, the collapse of the financial sector, and a dysfunctional political system in which 41 determined senators could block any legislative action. Others, such as Ari Berman, emphasized the fragmented Democratic Party but also faulted Obama's failure to convert a campaign movement into a governing strategy. Eric Alterman has single-handedly created a third category in his important new book, Kabuki Democracy. This short volume, an elaboration of an influential essay that he published last year in The Nation, is surprisingly kind to Obama--maybe a little too kind--and instead takes systematic stock of structural barriers to American progressivism.... Alterman goes well beyond the standard checklist (big money, the filibuster, right-wing media).... [T]he system is rigged, and it's rigged against us.

Some of this will be familiar--the time bombs left by the Bush-Cheney presidency; the weakness and ideological division within the Democratic Party compared to the GOP... the multiple tools and uses of legislative obstructionism; the increasing dominance of big money; and, of course, the asymmetric power of right-wing media.... Alterman's contribution is to add new insights and to connect more dots.... I have two quibbles.... Alterman is too gentle on Obama.... The second weakness is... "the Chapter 10 problem"--what do we do about this depressing picture?...

Liveblogging World War II: February 8, 1941

World War II Day-By-Day: Day 527 February 8, 1941:

The first Afrika Korps troops sail for Tripoli from Naples, Italy, aboard German steamers Ankara, Arcturus & Alicante (escorted by Italian destroyer Turbine and 3 torpedo boats)...

Peters Agonistes (Peter Orszag and Peter Baker, That Is)

We are live at The Week: http://mobile.theweek.com/bullpen/column/211888/the-ny-times-flunks-the-policy-test:

The NY Times flunks the policy test: When economics reporting at the nation's leading newspaper reads like gossip, we've got a problem:

Partisans of left and right complain that the mainstream media gets things wrong. I've been known to make that complaint once or twice. But I'm not sure that getting things wrong is as serious a problem in the press right now as not getting things at all.

I've been thinking about that a lot since reading Peter Baker's New York Times Magazine story about economic policy-making in the Obama administration. It is a subject that I have rather keen interest in.

Let me first recount my own perspective on President Obama's former Director of the Office of Management and Budget, Peter Orszag.

In January 2009 Peter Orszag took office as OMB director. The institutional role of the OMB director is to be the guardian of the long-run coherence of the government's tax and spending plans: To make sure that the receipts coming into the Treasury will, over the long run, match the spending commitments that the government has made. When you have OMB Directors who do not perform this institutional role — as David Stockman and James Miller failed to do their job in the Reagan administration, as Mitch Daniels, Josh Bolten, and Rob Portman failed to do their job in the Bush II administration — the economy gets into trouble. Excessive government borrowing crowds out productive private investment, businesses concerned about prospective tax hikes (to cover the government's spending commitments) cut back on their expansion plans, and economic growth slows.

When Orszag took office the U.S. government faced a very large gap between its long-run spending commitments and its plans for taxes because of the exploding costs of the government health-care programs Medicare and Medicaid — costs driven by rapidly rising costs in the health care sector generally. America's long-run fiscal gap had roughly tripled over the Bush II administration because if there was one thing the Bush II administration loved more than huge additional increases in spending — Medicare Part D and the post-9/11 defense buildup, anyone? — it was cutting taxes without caring for the long-run coherence of their policies. So Orszag turned his energy to figuring out some way, somehow, to get the government's taxes and spending commitments back in line with each other.

But January 2009 also saw America confront another more immediate and urgent economic problem than the long-run financing of government commitments. The wake of the financial crisis saw unemployment rise toward 10 percent as private-sector spending collapsed. The long-run fiscal dilemma required economy: That the government find ways to cut back its spending. The short-run downturn and recession required that the government do the opposite of economy: When the private sector sits down and stops spending, the government needs to stand up and spend in order to keep the economy near full employment. Government economy measures needed to be prepared but delayed until the crisis of elevated unemployment ended.

In the initial round of White House decision-making — the round that decided on the Recovery Act passed in February 2009 — Orszag agreed with his fellow members of Obama's National Economic Council that recovery in the short term was more important than deficit-reduction in the long term, and that the government should spend more without worrying just then how the debt it issued was to be repaid.

After that, however, Orszag's position shifted. As best as I can see (and I may be wrong here), others wanted to separate policy into two tracks — on the one hand a long-term track to balance the budget, focusing on health care reform to slow the growth of Medicare and Medicaid spending through increased efficiency; on the other hand, a short-term track focusing on getting America back to work by spending more money over the next few years without worrying about the effect of the short-term policy measures on the long term. Some policy makers believed that tying the two tracks together would diminish President Obama's chances of successfully getting the Congress to take action on either: Deficit hawks would not vote for long-term economy measures if they were tied to costly short-term stimulus; those worried about reducing unemployment would not vote for short-term stimulus measures if they were tied to long-term economy measures like tax increases and benefit cuts that they found distasteful.

Orszag, by contrast, thought that tying the two tracks together offered President Obama his best chance of success. Senate moderates, who were the swing votes on every issue, needed a story line on how the deficit would be brought under control in the long run to make them comfortable voting for stimulus in the short run. Thus attempts to decouple short-term and long-term were, in Orszag's view, the administration shooting itself in the foot. Moreover, if short-term stimulus was not going to be enacted on a sufficient scale, then hopes of a strong economic recovery would have to be pinned on a restoration of business confidence — and measures to put the long-run finances of the U.S. government on a sound basis were pretty much the only policy the administration could push that had a chance of restoring business confidence.

This was the message and the policy that Orszag pushed relentlessly throughout his time in the administration.

Now I think Orszag was wrong. I am more on the side of his adversaries inside the Obama administration, who were more inclined to decouple short-term stimulus from long-term economy measures. I am on their side because even the largest proposed stimulus plans were so small in the perspective of the long term as to be irrelevant to the debate over what to do in the long-term. I am on their side because even though I agree with Peter Orszag that tying the two tracks together would have been the best economic policy, the weight of people whose political judgment I trust is that Orszag is wrong on the legislative politics. (And, I must admit, I am on their side because I am better friends with some of his adversaries than with him.)

So why have I spent 1,000 words on Peter Orszag's positions and the economic policy dilemmas of the Obama administration?

Because I am still troubled by Peter Baker's New York Times Magazine piece on the positions and economic policy dilemmas of Peter Orszag and the other economic policymakers in the Obama administration. Because the striking thing about Peter Baker's piece — or, indeed, about practically everything that you read in MSM publications, since Peter Baker is not an anomalous outlier but rather a typical White House reporter — is that the article tells you remarkably little of what I have just recounted.

Instead, what the Times Magazine piece tells you about Orszag and Obama is that:

Obama is unhappy with the menu of policy options his advisors have been giving him.

Obama is so focused on the economy that he cancels lunch breaks to continue conversations.

Obama is pragmatic.

The process of making economic policy inside the Obama administration was no fun and was "dysfunctional."

Talking to Obama's economic policy staff is like "picking through the wreckage of a messy divorce."

Paul Volcker felt ignored by Peter Orszag and others.

Peter Orszag "was considered... arrogant. When Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood mentioned to a reporter that he had settled a dispute with Orszag by going around him to Emanuel, a peeved Orszag would not take his apology calls; LaHood ultimately sent a case of wine to make amends. Orszag also exchanged testy emails with Emanuel over the health care effort."

Other officials "tired of Orszag's refrain" about cutting the long-term deficit.

Orszag believes, "Unfortunately, I think the environment often brought out the worst in people instead of the best in people. And I'd include myself in that."

Of Larry Summers's replacement, Gene Sperling: "The selection of Sperling, who held the same job under Clinton, was telling. A onetime boy wonder who, despite his graying hair, still has the same whirling-dervish, work-till-midnight energy, Sperling... eventually won over Obama with his doggedness. As a champion of the payroll tax holiday, he proved critical to shaping Obama's tax deal with Republicans and so many other issues that White House officials refer to him as B.O.G., the Bureau of Gene. Where Summers was a master macroeconomic thinker, Sperling is known for his mastery of getting things done, or at least waging the fight, in the place where policy, politics and media meet."

Now (10) should simply make you laugh. It is a pure "beat sweetener" — a reporter who covers a regular beat extravagantly puffing up the reputation of somebody whom the reporter hopes will become a regular and reliable source of inside information. Gene is extremely talented and hard-working with enormous strengths — the same is true of Larry Summers, Christy Romer, and Peter Orszag — but he does not raise the dead, walk on water, or leap tall buildings with a single bound.

And (1) through (9)? Do you learn anything about the policy dilemmas faced by the Obama administration, about why different members of the administration took the positions that they did, or about why the push-and-pull led the administration to adopt the policies that it did? No.

Peter Baker's article reads like Hollywood celebrity journalism: 95 percent gossip, and perhaps 5 percent policy. This, to me, is a big problem. Celebrity gossip is the wrong rhetorical mode for a story in the nation's leading newspaper about White House economic policymaking. If The New York Times does not share that belief, if it views decision making on matters of state in the same light as decision making on matters concerning the Academy Awards, that may partially explain the fix the paper is in. It may also determine whether The Times ever emerges from its troubles with its influence and dignity intact.

In Which Suresh Naidu Has a Vision of the New Jerusalem...

Luke the Physician wrote:

[T]he multitude of them that believed were of one heart and of one soul: neither said any of them that ought of the things which he possessed was his own; but they had all things common.... Neither was there any among them that lacked: for as many as were possessors of lands or houses sold them, and brought the prices of the things that were sold, and laid them down at the apostles' feet: and distribution was made unto every man according as he had need...

But it was not just on the consumption side: it was on the production side as well:

Agabus... [declared] there should be great dearth... which came to pass in the days of Claudius Caesar. Then the disciples, everyone according to his ability, determined to send relief unto the brethren which dwelt in Judaea, which also they did, and sent it to the elders by the hands of Barnabas and Saul...

Suresh Naidu reads G.A. Cohen and writes:

The Slack Wire: Redistributive Justice and Wonkery: There are murmurs on the intertubes about redistributive justice... related murmurs about the lack of seriously left-wing blogs.... I have just finished reading G.A. Cohen's "Rescuing Justice and Equality", which is essentially a critique of Rawls from the left. The point is that the Rawlsian difference principle legitimizes a lot of inequality that runs counter to some of our ethical intuitions.... Rawls' argument allows talented people to hold back exercising their talents until they are compensated enough.... Cohen's book suggests the superstar doctor monster, who has medical skills and talents that are very valuable to the poorest people, but demands so much compensation that the resulting inequality is horrific. Liberals have no criticism of the doctor, but socialists think the doctor is fundamentally an unethical jerk.... Socialists can believe that the doctor's lack of solidarity, despite material abundance, depends on the presence of capitalist institutions that encourage rapacity, and criticize that kind of selfish behavior....

At the core of Cohen's argument is this "trilemma", that it is impossible to have all three of efficiency, equality, and free allocation of labor. Basically any two of these precludes the third (Stalinist rule gets you the first two and Rawlsian justice gets you 1 and 3, and nobody really wants the homogeneously poor society entailed by dropping 1). In economics this is formalized in the Mirrlees optimal income taxation problem... [in which] talented people should not be taxed because they produce a large amount per hour worked. A lot of the knock-on early Mirrlees-derived literature had a zero top-tax rate at the optimum (but recent literature weakens this, basically because the income distribution is potentially unbounded above and has fat tails).

Rawls is ok with that kind of inequality.... So I don't think that Rawlsianism is a socialist principle of distributive justice. In fact it is the bedrock philosophy of left-liberal and social democratic interventions.... Rawlsianism is also therefore the bedrock philosophy of the policy wonk, who thinks that social justice is a property of states alone and not a whole suite of institutions and behaviors.... Hence the endless key-punching on the details and consequences of this or that Democratic proposal, but little dialogue with social movements, political campaigns that are outside the government (like labor and tenant organizations), or radically non-neoclassical visions of the economy. Make no mistake, I enjoy and benefit from it, but I don't think its particularly agenda-setting for the left.

Cohen offers a way out of the trilemma by suggesting that we expand the domain of justice to include labor-supply decisions and preferences more generally.... Cohen thinks about egalitarianism as an ethic, not just as a property of government. He draws on feminist (and I would add anarchist) ideas that "the personal is political", that people's preferences and values are objects of justice, and that we can have a free allocation of labor that maintains distributive justice if people have ideals and ethics of conduct that sustain egalitarian distributions. So we should have grounds for criticizing the bankers and doctors for demanding so much money to do their jobs... [we should] organize for values and ethics (and deliberative politics that let us collectively construct and enforce these values and ethics across a variety of social sites) that sustain a society where anybody with talent would feel ashamed and ridiculous for demanding large amounts of compensation.

The idea that talented labor should demand a high wage is repugnant to socialist ethics; as Cohen eloquently states "labor, like love, should be freely given". As a scholar, the gift (and status) based economy of tenured academia is a lovely alternative allocation mechanism for human labor (and the reason I shouldn't start blogging for another 7 years)....

Bringing this all back together, I think I want to make two points about Rawlsian social democracy: a) It is quite compatible with a large amount of inequality and this is partially because b) it restricts the domain of criticism to the wonk playground of state policy. The Cohen book has the seed of a criticism of social democratic bloggers; it is against both the amount of inequality that Rawlsian social democracy (the kind favored by Yglesias et al.) allows as well as the narrow spectrum of technocratic state-centered instruments by which any extra inequality is addressed, So I think Freddie deBoer's criticism of the left-liberal wonk blog stands, and is part of the general libertarian socialist critique of the social democratic left.

I think the weakest point of Suresh's argument is something he recognizes: the "(and status)" in his description of the economy of tenured academia, which elicits enormous amounts of work effort with relatively small (and not very important) amounts of material inequality.

You can have a situation in which people work hard because they really want to be, as somebody-or-other once said, "one of the three international economists in the top ten" and otherwise everybody dresses in identical blue overalls and eats sustainably-farmed root vegetables.

You can have a situation in which people work hard because they want to go on the meal plan at The French Laundry and want the worst bottle of wine that ever touches their lips to be the 2005 Petit Bocq from St. Estephe.

The first tends to be zero sum. The second is positive sum. Perhaps you can argue that a society can value average the high consumption produced by general prosperity while scorning the pleasures brought by high consumption produced by inequality, but that would be a neat trick to accomplish when the fires of ideology begin to die down.

Indeed, even by the time St. Luke wrote his narrative down, the from-each-according-to-his-ability-to-each-according-to-his-need ethic of the first generation was but a memory, never again to be seen in this fallen Sublunary sphere.

This is an old, old fight in progressive political theory and practice. On the one hand we have the believers in the New Jerusalem, the advocates of a Republic of Virtue--the Jean Calvins and the Jean-Jacques Rousseaus and the Maximilien Robespierres and the Karl Marxes. As Robespierre said, we don't need no stinking checks-and-balances or optimal incentive schemes, for:

[T]he fundamental principle of the democratic or popular government... the essential strength that sustains it and makes it move... is virtue... the public virtue which brought about so many marvels in Greece and Rome and which must bring about much more astonishing ones yet in republican France; of that virtue which is nothing more than love of the fatherland and of its laws...

Of course Robespierre went on to say immediately thereafter:

[T] the strength of popular government in revolution is both virtue and terror; terror without virtue is disastrous, virtue without terror is powerless. Terror is nothing but prompt, severe, and inflexible justice; it is thus an emanation of virtue; it is less a particular principle than a consequence of the general principle of democracy applied to the most urgent needs of the fatherland...

The other side of the argument, of course, is that of Bernard de Mandeville on how clever institutional arrangements can harness the engine of selfishness to drive forward the public good and thus derive public benefits from private vices...

February 7, 2011

Did the Stimulus Stimulate? Real Time Estimates of the Effects of the American Readjustment and Recovery Act

James Feyrer and Bruce Sacerdote:

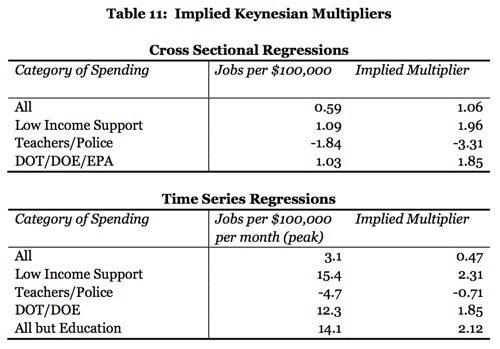

Did the Stimulus Stimulate? Real Time Estimates of the Effects of the American Readjustment and Recovery Act: We use state and county level variation to examine the impact of the American Readjustment and Recovery Act on employment. A cross state analysis suggests that one additional job was created by each $170,000 in stimulus spending. Time series analysis at the state level suggests a smaller response with a per job cost of about $400,000. These results imply Keynesian multipliers between 0.5 and 1.0, somewhat lower than those assumed by the administration. However, the overall results mask considerable variation for different types of spending. Grants to states for education do not appear to have created any additional jobs. Support programs for low income households and infrastructure spending are found to be highly expansionary. Estimates excluding education spending suggest fiscal policy multipliers of about 2.0 with per job cost of under $100,000.

All of these estimates are what we call "imprecisely estimated": whatever your prior beliefs were, they should not move very much.

Mark Thoma on the Remarkably Two-Faced Representative Darrell Issa (R-CA)

MT:

Economist's View: Issa: We've Know for Decades That the Policies I Called for Don't Work: IRepublican House member Darrell Issa has an op-ed in the Financial Times complaining that the stimulus did not stimulate (contrary to research such as this that finds "programs to support low-income households were highly stimulative, as was spending on infrastructure projects"). He says:

The abysmal results came as no surprise to those who knew that the Keynesian doctrine of spending your way to prosperity had been discredited decades ago...

[But t]his is what he said around the time when the stimulus package was put in place....

Economic Stimulus: There is bipartisan agreement for emergency spending on infrastructure and tax cuts that will create new jobs and reinvigorate private sector investments. Unfortunately, H.R. 1, the "American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009," falls short on both fronts.... To respond to an emergency, you must act quickly. According to the Congressional Budget Office, only 7 percent of the $355 billion in discretionary spending included in the bill would be injected into the economy by the end of fiscal year 2009. By the end of 2010, only 12 percent of the funds set aside for highway construction will be spent. Stimulus funds must be targeted to be effective. Only 3 percent of the $825 billion will go toward road and highway construction that creates jobs and aids individuals and private businesses alike.... An effective stimulus can be accomplished through tax cuts and targeted spending...

Targeted spending and tax cuts are effective stimulus, and he supports them, but we've known for decades that such Keynesian remedies don't work?...

A failure of due diligence on the part of the Financial Times, I must say. Have they no interns to read what the members of congress they commission wrote on the same topic two years ago?

Why Is There No Ebook of Ken Macleod's "The Restoration Game"?

Austin Frakt: The Individual Mandate Is the Last Line of Defense Before Single Payer

AF:

The simplest (political, not legal) defense of the mandate: If one wants to address the problems in health insurance markets and/or to get providers to accept payment reforms, the mandate–or something like it–is the political price. Yes, it’s about money. What else? Put it this way, if one wants to retain a private market-based health insurance system (which ours largely is), it takes a mandate. Reject the mandate without replacement with a similar mechanism and the whole thing unravels, not just as a matter of health economics (adverse selection) but as a matter of politics. If the private solutions fail, what’s left? It’s rather obvious, isn’t it? Yet this seems not to be widely appreciated.

The State of Working America

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers