J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2095

February 12, 2011

DRAFT Preparing to Launch the Berkeley Friday Afternoon Political Economy Colloquium...

DRAFT Colloquium: Spring 2011: Fridays 2-4 PM

Sponsored by the Blum Center on Developing Economies, the Political Economy Major, and the Institute for New Economic Thinking through the Berkeley Economic History Lab

February 18, 2011: "Austerity"

Topic:

For nearly 200 years economists from John Stuart Mill through Walter Bagehot and John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman to Ben Bernanke have known that a depression caused by a financial panic is not properly treated by starving the economy of government purchases and of money. So why does "austerity" have such extraordinary purchase on the minds of North Atlantic politicians right now?

Panel:

Chair: J. Bradford DeLong, UCB Economics

Speaker: Joseph Lough, UCB Political Economy

Speaker: Rakesh Bhandari, UCB Interdisciplinary Studies

Location: Blum Hall Plaza Level

Time: 2:10-2:40: Panelists. 2:40-3:10: Discussion. 3:10-4:00: Reception.

Let me speak as a card-carrying neoliberal, as a bipartisan technocrat, as a mainstream neoclassical macroeconomist--a student of Larry Summers and Peter Temin and Charlie Kindleberger and Barry Eichengreen and Olivier Blanchard and many others.

We put to one side issues of long-run economic growth and of income and wealth distribution, and narrow our focus to the business cycle--to these grand mal seizures of high unemployment that industrial market economies have been suffering from since at least 1825. Such episodes are bad for everybody--bad for workers who lose their jobs, bad for entrepreneurs and equity holders who lose their profits, bad for governments that lose their tax revenue, and bad for bondholders who see debts owed them go unpaid as a result of bankruptcy. Such episodes are best avoided.

From my perspective, the technocratic economists by 1829 had figured out why these semi-periodic grand mal seizures happened. In 1829 Jean-Baptiste Say published his Course Complet d'Economie Politique... in which he implicitly admitted that Thomas Robert Malthus had been at least partly right in his assertions that an economy could suffer from at least a temporary and disequliibrium "general glut" of commodities. In 1829 John Stuart Mill wrote that one of what was to appear as his Essays on Unsettled Questions in Political Economy in which he put his finger on the mechanism of depression.

Semi-periodically in market economies, wealth holders collectively come to the conclusion that their holdings of some kind or kinds of financial assets are too low. These financial assets can be cash money as a means of liquidity, or savings vehicles to carry purchasing power into the future (of which bonds and cash money are important components), or safe assets (of which, again, cash money and bonds of credit-worthy governments are key components)--whatever. Wealth holders collectively come to the conclusion that their holdings of some category of financial assets are too small. They thus cut back on their spending on currently-produced goods and services in an attempt to build up their asset holdings. This cutback creates deficient demand not just for one or a few categories of currently-produced goods and services but for pretty much all of them. Businesses seeing slack demand fire workers. And depression results.

What was not settled back in 1829 was what to do about this. Over the years since, mainstream technocratic economists have arrived at three sets of solutions:

Don't go there in the first place. Avoid whatever it is--whether an external drain under the gold standard or a collapse of long-term wealth as in the end of the dot-com bubble or a panicked flight to safety as in 2007-2008--that creates the shortage of and excess demand for financial assets.

If you fail to avoid the problem, then have the government step in and spend on currently-produced goods and servicesin order to keep employment at its normal levels whenever the private sector cuts back on its spending.

If you fail to avoid the problem, then have the government create and provide the financial assets that the private sector wants to hold in order to get the private sector to resume its spending on currently-produced goods and services.

There are a great many subtleties in how a government should attempt to do (1), (2), and (3). There is much to be said about when each is appropriate. There is a lot we need to learn about how attempts to carry out one of the three may interfere with or make impossible attempts to carry out the other branches of policy. But those are not our topics today.

Our topic today is that, somehow, all three are now off the table. There is right now in the North Atlantic no likelihood of reforms of Wall Street and Canary Wharf to accomplish (1) and diminish the likelihood and severity of a financial panic. There is right now in the North Atlantic no likelihood at all of (2): no political pressure to expand or even extend the anemic government-spending stimulus measures that have ben undertaken. And there is right now in the North Atlantic little likelihood of (3): the European Central Bank is actively looking for ways to shrink the supply of the financial assets it provides to the private sector, and the Federal Reserve is under pressure to do the same--both because of a claimed fear that further expansionary asset provision policies run the risk of igniting unwarranted inflation.

But there is no likelihood of unwarranted inflation that can be seen either in the tracks of price indexes or in the tracks of financial market readings of forecast expectations.

Nevertheless, you listen to the speeches of North Atlantic policymakers and you read the reports, and you hear things like:

“Obama said that just as people and companies have had to be cautious about spending, ‘government should have to tighten its belt as well...’”

Now there were—and perhaps there still are—people in the White House who took these lines out of speeches as fast as they could But the speechwriters keep putting them in, and President Obama keeps saying them, in all likelihood because he believes them.

And here we reach the limits of my mental horizons as a neoliberal, as a technocrat, as a mainstream neoclassical economist. Right now the global market economy is suffering a grand mal seizure of high unemployment and slack demand. We know the cures--fiscal stimulus via more government spending, monetary stimulus via provision by central banks of the financial assets the private sector wants to hold, institutional reform to try once gain to curb the bankers' tendency to indulge in speculative excess under control. Yet we are not doing any of them. Instead, we are calling for "austerity."

John Maynard Keynes put it better than I can in talking about a similar current of thought back in the 1930s:

It seems an extraordinary imbecility that this wonderful outburst of productive energy [over 1924-1929] should be the prelude to impoverishment and depression. Some austere and puritanical souls regard it both as an inevitable and a desirable nemesis on so much overexpansion, as they call it; a nemesis on man's speculative spirit. It would, they feel, be a victory for the Mammon of Unrighteousness if so much prosperity was not subsequently balanced by universal bankruptcy.

We need, they say, what they politely call a 'prolonged liquidation' to put us right. The liquidation, they tell us, is not yet complete. But in time it will be. And when sufficient time has elapsed for the completion of the liquidation, all will be well with us again.

I do not take this view. I find the explanation of the current business losses, of the reduction in output, and of the unemployment which necessarily ensues on this not in the high level of investment which was proceeding up to the spring of 1929, but in the subsequent cessation of this investment. I see no hope of a recovery except in a revival of the high level of investment. And I do not understand how universal bankruptcy can do any good or bring us nearer to prosperity...

I do not understand it either. But many people do. And I do not understand why such people think as they do. So let me turn it over to the first of our speakers, Joseph Lough, to try to provide some answers.

Adrian Hon: Disruptive Change in the Book Industry

AH:

More on the Death of Publishers: If book publishers want to see the next decade in any reasonable health, then it’s absolutely imperative that they rethink their pricing strategies and business models right now. Hopefully this example will illustrate why:

I’m a big fan of Iain Banks’ novels.... His latest novel, Surface Detail... 627 pages.... I lugged the thing home and began reading it this morning.... I found it difficult to pull myself away from it.... I didn’t have any space left in my bag, so I did the unthinkable – I googled "surface detail ePub" so I could download and read it on my iPad.... I try doing this every six months or so, and I usually end up mired in a swamp of fake torrent links and horrible PDF versions; for what it’s worth, this was mostly out of curiosity, since six months ago I didn’t own an iPad. This time, it took me 60 seconds to download a pristine ePub file, and another five minutes to move it to my iPad and iPhone. While this was going on, I took the opportunity to poke around the torrent sites and forums that my search had yielded, and discovered a wonderful selection of books.... “Oh, but we’ve still got the backlist!” I hear some publisher cry. No such luck... some helpful pirate... ePub, mobi, PDF and every other popular format (the non-fiction and literary selection is much worse though, which probably reflects the tastes of the people uploading the torrents – that’ll change soon enough).

I am not a torrent-finding genius – I just know how to add ‘ePub’ to the name of a book or author. I don’t need a fast internet connection, because most books are below 1MB in size, even in a bundle of multiple formats. I don’t need to learn how to use Bittorrent, because I already use that for TV shows. And Apple has made it very easy for me to add ePub files to my iPad and iPhone. So really, there is nothing stopping me from downloading several hundred books other than the fact that I already have too much to read and I think authors should be paid.

But why would the average person not pirate eBooks? Like Cory Doctorow says, it’s not going to become any harder to type in ‘Toy Story 3 bittorrent’ in the future – and ‘Twilight ePub’ is even easier to type, and much faster to download to boot....

But of course I’m exaggerating. Most publishers won’t go bust. eBook prices will be forced down, margins will be cut, consolidation will occur. New publishers will spring up, with lower overheads and offering authors a bigger cut. A few publishers will thrive; most publishers will suffer. Some new entrants will make a ton of cash; maybe there’ll be a Spotify or Netflix for books. Life will go on. Authors will continue writing – it’s not as if they ever did it for the money – and books will continue being published.

Three years ago, I wrote a blog post called The Death of Publishers.... Here’s an excerpt:

Book publishers have had a longer grace period than the other entertainment industries.... This has led many publishers to complacency, thinking there’s something special about books that will spare them.... They’re wrong. eBook readers are about to get very good, very quickly. A full colour wireless eBook reader with a battery life of over a week, a storage capacity of a thousand books, and a flexible display will be yours for $150 in ten years time....

How wrong I was! It’s only taken us three years to get the Kindle 3 at a mere $189, with a battery life of a month and a storage capacity of 3500 books.... But I was right about the complacency of publishers. They’ve spent three years bickering about eBook prices and Amazon and Apple and Andrew Wylie, and they’ve ignored that massive growling wolf at the door, the wolf that has transformed the music and TV so much that they’re forced to give their content away for practically nothing.

Time’s up. The wolf is here.

Adrian Hon, Copyright Criminal

AH:

More on the Death of Publishers: If book publishers want to see the next decade in any reasonable health, then it’s absolutely imperative that they rethink their pricing strategies and business models right now. Hopefully this example will illustrate why:

I’m a big fan of Iain Banks’ novels.... His latest novel, Surface Detail... 627 pages.... I lugged the thing home and began reading it this morning.... I found it difficult to pull myself away from it.... I didn’t have any space left in my bag, so I did the unthinkable – I googled "surface detail ePub" so I could download and read it on my iPad.... I try doing this every six months or so, and I usually end up mired in a swamp of fake torrent links and horrible PDF versions; for what it’s worth, this was mostly out of curiosity, since six months ago I didn’t own an iPad. This time, it took me 60 seconds to download a pristine ePub file, and another five minutes to move it to my iPad and iPhone. While this was going on, I took the opportunity to poke around the torrent sites and forums that my search had yielded, and discovered a wonderful selection of books.... “Oh, but we’ve still got the backlist!” I hear some publisher cry. No such luck... some helpful pirate... ePub, mobi, PDF and every other popular format (the non-fiction and literary selection is much worse though, which probably reflects the tastes of the people uploading the torrents – that’ll change soon enough).

I am not a torrent-finding genius – I just know how to add ‘ePub’ to the name of a book or author. I don’t need a fast internet connection, because most books are below 1MB in size, even in a bundle of multiple formats. I don’t need to learn how to use Bittorrent, because I already use that for TV shows. And Apple has made it very easy for me to add ePub files to my iPad and iPhone. So really, there is nothing stopping me from downloading several hundred books other than the fact that I already have too much to read and I think authors should be paid.

But why would the average person not pirate eBooks? Like Cory Doctorow says, it’s not going to become any harder to type in ‘Toy Story 3 bittorrent’ in the future – and ‘Twilight ePub’ is even easier to type, and much faster to download to boot....

But of course I’m exaggerating. Most publishers won’t go bust. eBook prices will be forced down, margins will be cut, consolidation will occur. New publishers will spring up, with lower overheads and offering authors a bigger cut. A few publishers will thrive; most publishers will suffer. Some new entrants will make a ton of cash; maybe there’ll be a Spotify or Netflix for books. Life will go on. Authors will continue writing – it’s not as if they ever did it for the money – and books will continue being published.

Three years ago, I wrote a blog post called The Death of Publishers.... Here’s an excerpt:

Book publishers have had a longer grace period than the other entertainment industries.... This has led many publishers to complacency, thinking there’s something special about books that will spare them.... They’re wrong. eBook readers are about to get very good, very quickly. A full colour wireless eBook reader with a battery life of over a week, a storage capacity of a thousand books, and a flexible display will be yours for $150 in ten years time....

How wrong I was! It’s only taken us three years to get the Kindle 3 at a mere $189, with a battery life of a month and a storage capacity of 3500 books.... But I was right about the complacency of publishers. They’ve spent three years bickering about eBook prices and Amazon and Apple and Andrew Wylie, and they’ve ignored that massive growling wolf at the door, the wolf that has transformed the music and TV so much that they’re forced to give their content away for practically nothing.

Time’s up. The wolf is here.

Avram on Heinlein...

Avram:

Making Light: Among Others Spoiler Thread: In general, and in keeping with Patrick's mention of "rewiring one's consciousness" by reading SF and fantasy, it seems to me that one of the important steps in a young [science fiction] fan's journey to maturity is realizing that Heinlein's ability to sound as if he knew what he was talking about was much greater than his ability to actually know what he was talking about...

Peter Dorman: The Weak Efficient Market Hypothesis Says Nothing about the Ability to Identify Bubbles

Not quite nothing, but almost nothing.

PD:

EconoSpeak: Why the Efficient Market Hypothesis (Weak Version) Says Nothing about the Ability to Identify Bubbles:One answer we keep hearing to that entirely reasonable question, “Why didn’t economists predict the crash?”, is that economic theory, in the form of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis, proves that reliable prediction is impossible.... The logical fallacy here is so obvious that I would not bother with this post if it were not for the persistence of the EMH defense. So here goes.... Let’s put aside the possibility that even the weak EMH can be wrong from time to time. We don’t need to go there; the error is more basic than this.

Let’s put ourselves back in 2005. It is two years before the unraveling of the financial markets, but I don’t know this; all I know is what I can see in front of me, publicly available 2005 data. I can look at this and see that there is a housing bubble, that prices are rising far beyond historical experience or relative to rents. The “soft” warning signs are all around me, like the explosion of cheap credit, the popularity of credit terms predicated on ever-rising prices, and the talk of a new era in real estate. Based on my perceptions, I anticipate a collapse in this market. What can I do? If I am an investor, I can short housing in some fashion. My problem is that I have no idea how long the bubble will go on, and if I take this position too soon I could lose a bundle. In fact, anyone who went short in 2005 and passed on the following two years are price frothery grossly underperformed relative to the market as a whole. Indeed, you might not have the liquidity to hold your position for two long years and could end up losing everything.... [N]ot even your prescient analysis of the fundamentals of the housing market would enable you to outperform more myopic investors or even a trading algorithm based on a random number generator.

The logical error lies in confusing the purposes of an investor with those of a policy analyst. Suppose I work for the Fed, and my goal is not to amass a personal stash but to formulate economic policies that will promote prosperity for the country as a whole. In that case, it doesn’t much matter whether the bubble bursts in 2006, 2007 or 2010. In fact, the longer the bubble goes on, the more damage will result from its deflation. At the policy level, the relevant question is whether trained analysts, assembling data and drawing on centuries of experience in financial manias, can outperform, say, tarot cards in identifying bubbles. The EMH does not defend tarot.

To profit from one’s knowledge of a market condition one needs to be able to outperform the mass of investors in predicting market turns, which the EMH says you can’t do. Good policy may have almost nothing to do with the timing of market turns, however.

Bruce Bartlett on Why Friends Don't Let Friends Support the Republican Party in Any Way: Federal Budget Edition

BB:

GOP Cuts Budget with an Axe Instead of a Scalpel: The point is not that there are no government programs worthy of cutting, but rather that this is a really stupid way to do it. The vast bulk of government spending, which goes to mandatory programs such as Social Security and Medicare, is completely exempted. And Republicans have effectively exempted the departments of Defense, Homeland Security and Veterans Affairs from cuts. This leaves only 16 percent of the budget from which they will extract their pound of flesh to satisfy voters who demand huge budget cuts but also oppose cutting just about any program except foreign aid....

[T]he fact is that millions of Americans benefit from government programs without realizing it. Indeed, research by Cornell political scientist Suzanne Mettler shows that many recipients of government benefits don’t believe that they have received any benefits..... The most recent study I could find that tried to do that was published by the Tax Foundation in 2007. It found that in 2004, a typical middle class family in the middle income quintile received $16,781 in benefits from the federal government.

No doubt, many of these people will very quickly find out who they are as soon as lobbyists start fighting the proposed cuts. Advertising, news stories, congressional testimony, and analyses from trade associations and think tanks will all be mobilized to identify, precisely, who will lose from the Republican meat ax and to make their views known. We could soon have a reverse Tea Party of laid off government workers, farmers and who knows how many other people irate at losing government benefits or government services such as post offices that will probably have to be closed.

We are already seeing some Tea Party favorites backtracking on their budget-cutting promises. For example, Rep. Michele Bachmann, R-MN, had promised to cut veterans benefits by $4.5 billion. But when veterans complained, she quickly took those cuts off the table. And on the House floor, Republican leaders have had difficulty getting the votes for their silly budget cut of the week plan.

It may turn out that the Republican effort is all for show... like their symbolic vote to repeal the Affordable Care Act....

[C]tting spending is neither easy, nor simple, nor fast. Republicans may imagine that they are leading a Blitzkrieg against government, but the reality is that it is trench warfare. Every serious budget expert knows this. Republicans have been deluding their allies in the Tea Party movement with promises that they knew they couldn’t keep. Soon, everyone else will know, too.

Felix Salmon: Treasurys Housing Report

FS:

Judging Treasury’s housing report: I’m impressed with Treasury’s long-awaited report on reforming the US housing market.... The message is clear: what we have right now is unacceptable, and we need to do something big; the main choice facing Congress is between a modest government housing guarantee, a tiny one, or none at all.... One very welcome theme running through the report, from the beginning of the introduction, is that an important part of “affordable housing” is giving people “rental options near good schools and good jobs” which don’t take up an inordinate proportion of total income.... The report is also clear-eyed about two aspects of the US mortgage market which seem to be sacrosanct: the pre-payable, 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, on the one hand, and the mortgage-interest tax deduction, on the other. It notes that both are pretty much unique to the US, and cause significant distortions and risks...

The main problem I have with Treasury’s report is that it simply assumes that if government support for the housing market is slowly removed, then private money will come in to take its place — at a higher price, to be sure, but at some price. The big risk is that private money won’t come in, at any price, if there isn’t a guarantee — that the amount of private funding for the US mortgage market will be substantially lower than the demand for mortgage loans. The result would be a broken, non-clearing market, with people stuck in their homes because they can’t sell them, and the idea of a “market price” being somewhere between a purely theoretical entity and an outright joke.

That’s why my preference would be for Treasury’s third option, where the government guarantee remains extant, just with a lot more safeguards....

As this debate moves to Congress, it’s going to be crucial to be able to examine such claims impartially, and to decide whether Treasury’s optimism regarding the future risk appetite of private capital is justified. Any bright ideas as to how to do that? Because I can’t think of anything offhand.

Jeremiah Dittmar: The Impact of the Printing Press

JD:

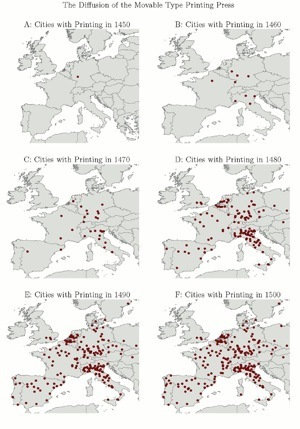

Information technology and economic change: The impact of the printing press: Using data on 200 European cities between 1450 and 1600... economic growth was higher by as much as 60 percentage points in cities that adopted the technology.

That's 60% over 150 years--0.4%/year:

Printing, lately invented in Mainz, is the art of arts, the science of sciences. Thanks to its rapid diffusion the world is endowed with a treasure house of wisdom and knowledge, till now hidden from view. An infinite number of works which very few students could have consulted in Paris, or Athens or in the libraries of other great university towns, are now translated into all languages and scattered abroad among all the nations of the world. --Werner Rolewinck (1474)

JD:

The movable type printing press was the great revolution in Renaissance information technology.... Contemporaries saw the technology ushering in dramatic changes in the way knowledge was stored and exchanged (Rolewinck 1474). But what was the economic impact of this revolution in information technology?... [E]conomists have struggled to find any evidence of this information technology revolution in measures of aggregate productivity or per capita income.... I examine the revolution in Renaissance information technology from a new perspective by assembling city-level data on the diffusion of the printing press in 15th-century Europe.... [C]ities in which printing presses were established 1450-1500 had no prior growth advantage, but subsequently grew far faster than similar cities without printing presses....

Did printers simply pick locations that were already bound for growth? This question can be addressed by exploiting supply-side constraints that limited the diffusion of the technology over the infant industry period.... The key innovation in printing – the precise combination of metal alloys and the process used to cast the metal type – were trade secrets. The underlying knowledge remained quasi-proprietary for almost a century.... Over the period 1450-1500, the master printers who established presses in cities across Europe were overwhelmingly German. Most had either been apprentices of Gutenberg and his partners in Mainz or had learned from former apprentices.... [C]ities relatively close to Mainz were more likely to receive the technology.... The geographic pattern of diffusion thus arguably allows us to... [use] distance from Mainz as an instrument for adoption.... The importance of distance from Mainz is supported by an exercise using “placebo” distances. When I employ distance from Venice, Amsterdam, London, or Wittenberg instead of distance from Mainz as the instrument, the estimated print effect is statistically insignificant.

Cities that adopted print media benefitted from positive spillovers in human capital accumulation and technological change broadly defined. These spillovers exerted an upward pressure on the returns to labour, made cities culturally dynamic, and attracted migrants.... Print media played a key role in the development of skills that were valuable to merchants.... [P]rint media was also associated with the diffusion of cutting-edge business practice (such as book-keeping), literacy, and the social ascent of new professionals – merchants, lawyers, officials, doctors, and teachers...

Jeremiah Dittmer: The Impact of the Printing Press

JD:

Information technology and economic change: The impact of the printing press: Using data on 200 European cities between 1450 and 1600... economic growth was higher by as much as 60 percentage points in cities that adopted the technology.

That's 60% over 150 years--0.4%/year:

Printing, lately invented in Mainz, is the art of arts, the science of sciences. Thanks to its rapid diffusion the world is endowed with a treasure house of wisdom and knowledge, till now hidden from view. An infinite number of works which very few students could have consulted in Paris, or Athens or in the libraries of other great university towns, are now translated into all languages and scattered abroad among all the nations of the world. --Werner Rolewinck (1474)

JD:

The movable type printing press was the great revolution in Renaissance information technology.... Contemporaries saw the technology ushering in dramatic changes in the way knowledge was stored and exchanged (Rolewinck 1474). But what was the economic impact of this revolution in information technology?... [E]conomists have struggled to find any evidence of this information technology revolution in measures of aggregate productivity or per capita income.... I examine the revolution in Renaissance information technology from a new perspective by assembling city-level data on the diffusion of the printing press in 15th-century Europe.... [C]ities in which printing presses were established 1450-1500 had no prior growth advantage, but subsequently grew far faster than similar cities without printing presses....

Did printers simply pick locations that were already bound for growth? This question can be addressed by exploiting supply-side constraints that limited the diffusion of the technology over the infant industry period.... The key innovation in printing – the precise combination of metal alloys and the process used to cast the metal type – were trade secrets. The underlying knowledge remained quasi-proprietary for almost a century.... Over the period 1450-1500, the master printers who established presses in cities across Europe were overwhelmingly German. Most had either been apprentices of Gutenberg and his partners in Mainz or had learned from former apprentices.... [C]ities relatively close to Mainz were more likely to receive the technology.... The geographic pattern of diffusion thus arguably allows us to... [use] distance from Mainz as an instrument for adoption.... The importance of distance from Mainz is supported by an exercise using “placebo” distances. When I employ distance from Venice, Amsterdam, London, or Wittenberg instead of distance from Mainz as the instrument, the estimated print effect is statistically insignificant.

Cities that adopted print media benefitted from positive spillovers in human capital accumulation and technological change broadly defined. These spillovers exerted an upward pressure on the returns to labour, made cities culturally dynamic, and attracted migrants.... Print media played a key role in the development of skills that were valuable to merchants.... [P]rint media was also associated with the diffusion of cutting-edge business practice (such as book-keeping), literacy, and the social ascent of new professionals – merchants, lawyers, officials, doctors, and teachers...

Pessimism of the Intellect...

Reading three things from Paul Krugman:

Medicare Recipients Against Handouts: You know, I’d always thought that the “don’t let the government get its hands on Medicare” contingent, while picturesque, wasn’t all that large. But noooo: 44 percent of Social Security recipients, and 40 percent of Medicare recipients, believe that they don’t benefit from any government social program. Democracy really is the worst system there is, except for all the others.

And:

Eat the Future: The public says it wants to see government spending cut — and the Tea Partiers really, really want spending cut — but people don’t want to cut any program they like; and they like almost everything. What’s a conservative to do? The obvious answer, once you think about it, is to eat the future: to cut spending in a way that undermines the nation’s long-run prospects, but doesn’t impose all that much pain on voters right now. And that, as best as I can tell, is the running theme in the cuts proposed by House Republicans. The proposal is, deliberately I think, hard to read and interpret; I hope and assume that the good folks at CBPP will do the detail soon. But on a quick read.... WIC is nutritional aid for pregnant women and women with young children; let’s cut that, because the damage to the nation from malnourishment is a problem for future politicians. NOAA is weather and climate — hey, what we don’t know can’t hurt us. Nuclear nonproliferation — well, we probably won’t feel the pain of a terrorist nuke assembled from old Soviet fissile material for a couple of years. FEMA — well, how often do hurricanes hit New Orleans? CDC — with luck, by the time plague hits someone else can be blamed. Don’t start thinking about tomorrow.

And worst of all:

Structural Impediment: Interesting and depressing interview with Charles Plosser, the Fed’s reigning inflation hawk. What’s striking is that he is completely committed to the view that we’re experiencing structural employment:

Mr. Plosser’s answer is unequivocal: This mess was caused by over-investment in housing, and bringing down unemployment will be a gradual process. “You can’t change the carpenter into a nurse easily, and you can’t change the mortgage broker into a computer expert in a manufacturing plant very easily. Eventually that stuff will sort itself out. People will be retrained and they’ll find jobs in other industries. But monetary policy can’t retrain people. Monetary policy can’t fix those problems.”

It really makes you despair: we’ve been over and over the evidence, and there’s not a hint in the data that a mismatch between occupations and jobs can explain any important fraction of the jobless rate. But Plosser doesn’t even consider the case that this might not be the story. Oh, and later he argues that monetary policy should be based on growth rates, not estimates of the output gap; clearly the Fed needed to tighten sharply in 1934...

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers