J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2091

February 17, 2011

Republicans Lie, All the Time, About Everything: Speaker Boehner's Statistics

Outsourced to David Leonhardt:

Speaker Boehner's 200,000: When I read that John Boehner, the speaker of the House, had said that the federal government added 200,000 federal workers under President Obama, I wondered, “Really? Where?” I’m not aware of any major federal hiring initiatives since January 2009. Ezra Klein asked the same question, and, even better, answered it. It turns out that the 200,000 number is simply incorrect.

First, Mr. Boehner was excluding postal workers, according to his spokesman. Why? It’s not clear.

Second, Mr. Boehner was starting his clock in December 2008, the month before Mr. Obama became president. The Bureau of Labor Statistics conducts its monthly survey during the week that contains the 12th day of each month, so there is no reason to start the clock in December 2008 as opposed to January 2009. On Jan. 12, 2009, George W. Bush was still president.

Finally, Mr. Boehner appears to be an aggressive rounder of numbers. Even if postal workers were excluded and even if Mr. Obama’s inauguration were retroactively moved to Dec. 20, 2008, the federal government has added only 153,000 jobs — not 200,000....

[T]here’s an important underlying issue here. You often hear politicians say that government needs to get out of the way so private companies can start hiring. But government has been getting out of the way, at least in terms of employment. Total government employment — federal, state and local — peaked last May and is now about 350,000 below its level in January 2009. Yet those cuts don’t seem to have spurred much private-sector hiring. So to focus on government employment as the economy’s problem is to misdiagnose the situation.

Here, for the record, is a quick tally of how Mr. Boehner gets to 200,000:

Actual federal government jobs added since January 2009, mostly in security — Homeland Security, Defense, State and Justice: 57,000.

Federal jobs added during Mr. Bush’s last month in office: 11,000.

Postal Service jobs cut since January 2009 (thus boosting the net gain if you exclude the Postal Service, as Mr. Boehner did): 85,000.

Effect of rounding 153,000 up to 200,000: 47,000.

Deficit Reduction Plans

Jonathan Chait reads Jonathan Weisman in the Wall Street Journal and writes that he finds Weisman's story:

JC: actually hard to believe. According to [Weisman's] story, the [possible Senate ten-year budget] deal calls for nearly ten times as much spending cuts ($1.7 trillion) as higher revenue ($180 billion.) Do you know how little $180 billion over ten years is? It's essentially nothing. It's one-quarter as much as the cost of extending the Bush tax cuts only on income over $250,000.

And Chait asks:

Are Democrats Negotiating A Monumentally Stupid Deficit Deal?

Could centrist Democrats really endorse a package that cuts spending by $9 for every $1 of revenue raised?

Check first to see if Chait is correctly reading Weisman. Yep. Weisman says that the Group of Six is following Simpson-Bowles on the spending side and strongly implies that it is going to follow Simpson-Bowles on the tax side as well:

Jonathan Weisman: Senate Deficit Plan Details Emerge: The Senate group's working plan calls for placing separate caps on security and nonsecurity spending, and missing a budget target in one area would not trigger mandatory cuts in the other. The spending targets would follow proposals laid out by the deficit commission, which recommended cutting discretionary spending by $1.7 trillion through 2020. Lawmakers on the spending committees would draft legislation to meet the targets. But if they were not met, automatic, across-the-board cuts would go into effect. The tax-writing committees would be given two years to overhaul both the individual and corporate tax codes, with general instructions to close tax breaks and minimize or eliminate tax deductions while lowering tax rates. The committees would be given a target for additional revenues to be raised by the new code. The deficit commission's version of tax reform would net $180 billion in additional revenues over 10 years...

But centrist Senate and White House sources both say that the $1.7 trillion spending cut and $180 billion tax increase numbers in Weisman's article are simply not comparable, and should not have been compared.

Me? If I were a centrist Democrat, I would start negotiating from a baseline that assumes the expiration of all of the 2001 and 2003 revenue measures and that also imposes an high-income surtax to pay for Medicare Part D, and start the negotiation from there. But that is just me.

Centrists--Democrats and Republicans--should be shooting for a 1-to-1 ratio, not a 9-to-1 ratio.

February 16, 2011

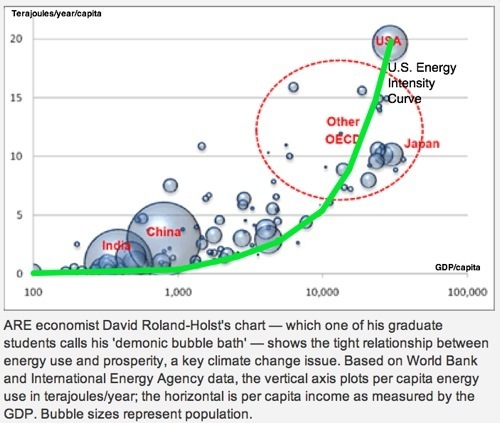

The Energy Intensity of GDP Curve

Tom Levenson: Megan McArdle is Always Wrong: Reading Papers Is Hard Edition

Tom Levenson:

Megan McArdle is Always Wrong: Reading Papers Is Hard edition: [P]rofound differences between what she says the research reveals and what in fact you find should you read the stuff yourself... consider this from McArdle:

One of the things the legacy of racism has taught us is just how good dominant groups are at constructing narratives that justify their dominance. Somehow, the problem is never them. It’s always the out group.... So while in theory, it’s true that you can’t simply reason from disparity to bias, I have to say that when you’ve identified a statistical disparity, and the members of the in-group immediately rush to assure you that this isn’t because of bias... discrimination starts sounding pretty plausible. When that group of people is assuring you that the reason conservatives can’t be in charge is that they do not have open minds... it starts sounding very plausible. More plausible than I, who had previously leaned heavily on things like affinity bias to explain the skew, would have thought.

Moreover, what evidence we have does not particularly support many of the alternative theories.... I’d say it’s more consistent with the possibility that they’re disproportionately having a hard time getting hired, or retained.

I quote at length to avoid McArdle’s common dodge when caught in hackery that crucial context has been omitted that would reveal her ultimate wisdom.... But all that aside, look to that last paragraph:

what evidence we have does not particularly support many of the alternative theories (to bias).

The “evidence” at that link is a study by two social scientists, Neil Gross of Harvard and Solon Simmons of George Mason University, titled “The Social and Political Views of American Professors,” distributed in 2007. A reasonable person would, I think, interpret McArdle’s cite of this paper as claiming that Gross and Simmons’ research supports her statement that the most plausible explanation for the ratio of liberals to conservatives in the academy is bias.

I’m guessing folks know what’s coming next.... So: does the paper McArdle relies on for her claims of bias state that the academy is clearly overwhelmingly liberal?

No:

Where other recent studies have characterized the American college and university faculty as not simply extremely liberal, but nearly uniformly so.... [W]hile conservatives, Republicans, and Republican voters are rare within the faculty ranks, on many issues there are as many professors who hold center/center-left views as there are those who cleave to more liberal positions, while the age distribution indicates that, in terms of their overall political orientation, professors are becoming more moderate over time...

What does academic faculty actually look like?:

Collapsing the data accordingly to a three point scale, we find that 44.1 percent of respondents can be classified as liberals, 46.6 percent as moderates, and 9.2 percent as conservatives...

Well, maybe that just reflects an aging, embattled cohort of moderation losing ground to ivy-covered radicals. Or maybe not:

Table 4 shows that the youngest age cohort – those professors aged 26-35 – contains the highest percentage of moderates, and the lowest percentage of liberals. Self-described liberals are most common within the ranks of those professors aged 50-64, who were teenagers or young adults in the 1960s... in recent years the trend has been toward increasing moderatism...

Is there nonetheless a monolithic culture of opinion in the classroom or on tenure review boards?

What overall conclusion can be drawn from our analysis of the attitudes items? What we wish to emphasize is simply that there is more attitudinal complexity and heterogeneity in the professorial population than second wave researchers have attended to. It seems to us unlikely that a simplistic notion like “groupthink” – more of a political slur than a robust social-scientific concept – can do very much to help explain...

Finally, is bias really the one best explanation social scientists see to explain the political landscape of American universities? As discussed in Neil Gross’s paper with Ethan Fosse “Why Are Professors Liberal” (2010 – link at Gross’s webpage), the answer is again (guess!)... No:

For example, Woessner and Kelly-Woessner (2009) find that twice as many liberal as conservative college students aspire to complete a doctorate... conservative students at a major public university regard faculty members disparagingly and do not seek to emulate them in any way... high levels of religious skepticism result not from professional socialization, but from the greater tendency of religious skeptics to become scientists... conservatism, Republican Party affiliation, and evangelical identity are associated with less confidence in higher education and diminished evaluations of the occupational prestige of professors...

There’s lots more, as I’m sure you’ve guessed by now. But I think y’all get the idea:

There is, contra McArdle, plenty of research out there on academic political attitudes. That which she invokes, does not conform to the myth she wishes to advance here. The specific paper she cites explicitly contradicts the thrust of her argument...

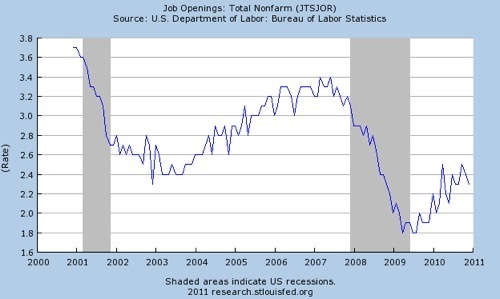

Where Oh Where Is My Structural Unemployment?

Where oh where are my lots of job openings going begging for lack of skilled workers to fill them?

Where oh where is the upward pressure on earnings in occupations where demand for labor has outstripped supply?

Oh. You say that compensation for hedge fund managers and lobbyists is rising?

Ethan Pollack and Josh Bivens: An Investment That Worked: The Recovery Act Two Years Later

Ethan Pollack and Josh Bivens:

An investment that worked: The Recovery Act two years later: The Recovery Act, signed into law Feb. 17, 2009... designed to cushion the economy’s free-fall, create jobs, and return the country to economic growth.... The Recovery Act clearly has been effective at providing the economic support for spurring output and employment that was promised by its architects:

The Recovery Act was enacted at a time when the private economy was contracting by more than a 6% annual rate and losing more than 750,000 jobs a month. In the first full quarter after its enactment, the Recovery Act had cut average monthly private job losses by more than half and slowed the economic contraction to a -0.7% annual rate. Private job loss fell again, by a third, in the following quarter and then fell by nearly three-fourths in the quarter after that, at which point the economy was growing at a 5% annual rate. Clearly, the economy and private job market began to recover right when the Recovery Act began to take effect.

EPI analysis shows that by the end of 2010 the Recovery Act had created or saved 3-4 million jobs, and up to 5 million full-time equivalent jobs. It had also boosted gross domestic product by up to $560 billion and reduced the unemployment rate up to 1.8 percentage points. (This finding is consistent with analyses by the Congressional Budget Office, the Council of Economic Advisors, and private-sector forecasters.)

The process by which the Recovery Act produced positive economic activity is straightforward. The bursting of the housing bubble inflicted a huge negative shock on spending in the U.S. economy. As household wealth evaporated due to plummeting real estate prices, both households and businesses radically cut back their demand for goods and services and demand for new construction dried up.. The Recovery Act helped offset this decline in private-sector demand by boosting public sector purchasing. Many kinds of spending outlays (or tax cuts) could have fulfilled this shock-absorbing function in the very short-run. And indeed, the Recovery Act was a portfolio of various spending increases and tax cuts (a portfolio much more heavily weighted toward tax cuts than most observers realized)...

Paul Waldmann: Curveball (Bush Administration Incompetence Watch)

Paul Waldmann:

: As you might have seen -- though it wasn't the front-page news it ought to have been -- "Curveball," the Iraqi defector who provided the casus belli the Bush administration was searching for to justify the invasion of Iraq, has now admitted he made everything up. To review: In February 2003, noted motivational speaker Colin Powell went before the United Nations and delivered a terrifying presentation demonstrating that Iraq was brimming with horrific weapons of mass destruction, all poised to launch at the United States and who knows who else, obviously some time within the next 10 minutes or so, and therefore we just had no choice but to invade. Much of Powell's case was built on the allegations of "Curveball," a person who had left Iraq five years before and whom U.S. intelligence officials had never interrogated. He was interviewed by German intelligence officials, who passed them to the Americans while insisting that they were probably bogus, as indeed they turned out to be. But everything he said was assumed by the administration to be 100 percent true -- Powell even showed computer animations of mobile chemical weapons labs, based on Curveball's invented stories. Powell's show included lots of other falsehoods and intentionally misleading claims, from those "nuclear" aluminum tubes to phantom VX nerve gas to nonexistent long-range missiles (there's a good run-down here).

Things move fast these days, and 2003 can seem like ancient history to some. But given that the run-up to the war in Iraq was the greatest media failure in decades, I thought this would be a good opportunity to remind ourselves of the tears of joy and gratitude that greeted Powell's U.N. speech. What's important to keep in mind is that a lot of Powell's bogus claims were known at the time to be false or baseless, if reporters had bothered to ask around. But they didn't, because they were so blinded by how awesome Powell was. Think I exaggerate? Let's take a look back:

"Secretary of State Colin Powell's strong, plain-spoken indictment of the Saddam Hussein regime before the UN Security Council Wednesday embodies something truly great about the United States. Those around the world who demanded proof must now be satisfied, or else admit that no satisfaction is possible for them." -- Chicago Sun-Times

"In a brilliant presentation as riveting and as convincing as Adlai Stevenson's 1962 unmasking of Soviet missiles in Cuba, Powell proved beyond any doubt that Iraq still possesses and continues to develop illegal weapons of mass destruction. The case for war has been made. And it's irrefutable." -- New York Daily News

"Only those ready to believe Iraq and assume that the United States would manufacture false evidence against Saddam would not be persuaded by Powell's case." -- San Antonio Express-News

"The evidence he presented to the United Nations -- some of it circumstantial, some of it absolutely bone-chilling in its detail -- had to prove to anyone that Iraq not only hasn't accounted for its weapons of mass destruction but without a doubt still retains them. Only a fool -- or possibly a Frenchman -- could conclude otherwise." -- Richard Cohen, Washington Post

That's just a small sample, but you see the pattern: Not only was Powell's show presented as settling the matter of whether Iraq had this terrifying arsenal and would use it on us, but if you didn't agree, you were either an Iraqi sympathizer or at the very least anti-American. At that point, the debate over whether we would invade was pretty much over -- the only question was when the bombs would start falling. It may boggle the mind that so much of the case for war was based on the testimony of one absurdly unreliable guy. But that was what passed for "intelligence" during the Bush years.

Magic Budget Asterisks Watch

Paul Krugman send us to Bob Greenstein:

Asterisks: The Gall: “I’m very frustrated by the debate in the media over this,” [Greenstein] told [Ezra Klein]. “The whole discussion starts from the following assumption: The president had a fiscal commission, they stepped up to the plate, identified the big changes, and he walked away. The assumption was wrong. Simpson-Bowles was one big magic asterisk.

And Paul comments:

Indeed. Simpson-Bowles was, essentially, a Disappearing Zonkers Trick. And like the Ryan plan, which I also described that way, it does not deserve respect

America's Fiscal Problem Is Something We Can Fix Only at the Ballot Box

And we are live at The Economist:

"How close is America to fiscal crisis?" The London Economist asks: "The Congressional Budget Office projects that America's 2011 deficit will be $1.5 trillion, or 9.8% of GDP, and debt held by the public in the 2011 fiscal year will approach 70% of GDP..."

We get a bunch of responses.

John Makin laments that "a a fiscal crisis—signalled by sharply higher borrowing costs for the United States government—probably won’t emerge" soon. Stephen King laments that "America's fiscal arithmetic simply does not add up." Scott Sumner laments that "our fiscal regime is becoming increasingly dysfunctional... radical reform would be quite helpful." "The ingredients are in place for a crisis," claims Peter Boone. "America is bankrupt," claims Larry Kotlikoff.

These seem, to me at least, to completely miss the point.

Tom Gallagher, by contrast, seems to me to at least get his finger on a piece of the problem when he writes: "[W]hat the economy could use is a debate over medium-term entitlement and tax changes. Instead what it's getting is a debate over near-term non-security discretionary spending."

What is going on? What is our problem, really?

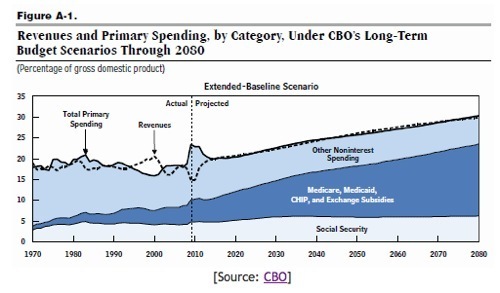

Start with Figure A-1 from the CBO's 2010 Long-Term Budget Outlook:

This shows that America has a large short-term deficit now: we are still in a deep downturn, and as a result revenues are temporarily below trend and spending is temporarily above trend.

This also shows that, as the CBO projects in its current-law extended baseline, when the economy recovers revenues will rise and spending will decline, and from 2015 on the revenue line matches the total primary spending line.

Now our current deficit is not a problem: running a deficit during an economic downturn is healthy and appropriate. Our short-term deficit problem is that our deficit is not large enough given that if congress simply goes on autopilot the revenue and primary spending lines are likely to cross by themselves in four years.

And our long term projected spending and revenue balance is not a problem. There is no imbalance. Or, rather, there is no imbalance if. If the economy and if programs perform as expected, if the U.S. government continues to be able to finance its debt at a real interest rate less than the growth of labor productivity plus the labor force, and if congress and the president do not do anything further to raise spending above or decrease taxes below current law, the United States simply does not have a fundamental fiscal crisis.

The problems are all in the ifs. If people fear that there will be a fiscal crisis they could demand an interest rate premium for rolling over U.S. government debt, and then we would we have a non-fundamental fiscal crisis. Could we have one? Yes: the East Asian economies had one in 1997-1998. Had foreign investors not panic and fled, there would have been no problem. Those foreign investors who did not panic did well. Those who bailed themselves in at the bottom of the crisis did extremely well. But that was no consolation to the East Asian governments that faced the crisis, or to the East Asian workers rendered unemployed by the consequences of the crisis.

However, today there are no signs of any possibility of a collapse of foreign investor confidence in their U.S. Treasury holdings. A non-fundamental crisis is not even a cloud on the horizon.

But there are the other ifs.

The big if is, to put it simply, this: congress will pass something stupid and the president will sign. Congress might never come up with payfors for its recurrent AMT patches. Congress might remove the revenue raising parts of the Affordable Care Act. Congress might remove the cost saving parts of the Affordable Care Act. The Supreme Court might decide, just for the hell of it, to rule that the cost saving parts of the Affordable Care Act are unconstitutional. Congress might pass a big unfunded tax-cut just for the hell of it. Congress might pass a big unfunded spending increase just for the hell of it.

All of these ifs are very real worries.

But none of them can be fixed by legislative action now.

No congress now can cement up the exits to keep some future congress from doing something really stupid.

And dinking around with cuts to non-security discretionary spending right now doesn't do anything to help.

What is the solution to our long-run deficit problem? It is simply this: elect honorable and intelligent women and men to Congress. Elect representatives who will not pass unfunded tax cuts--as the Republicans did in 2001. Elect representatives who will not pass unfunded spending increases--as the Republicans did in 2003. Elect presidents who will promise at the start of their turns to veto legislative acts that do not meet long run paygo requirements. Choose supreme court justices who will not prostitute their high office for the short term political benefit of the party they happen to belong to--as the Republican justices did after the 2000 election.

Gee. I guess our long run fiscal problem is really dire and insoluble.

Mark Thoma: Barking Up the Wrong Tree: Social Security is *Not* the Problem

MT:

Economist's View: Barking Up the Wrong Tree: Social Security is Not the Problem: Though there seems to be a concerted effort to get people to believe otherwise, Social Security has very little to do with our long-run budget problem.

Let me add: the worries about the long-term deficit--the worries about the unsustainability of our current fiscal plans--are all worries that congress will not stick to PAYGO when it changes current law. If it sticks to current law, then we have a we-are-not-getting-fair-value-for-our-health-spending problem but not a government solvency problem. If tax cuts relative to current law are financed by spending cuts, then we simply do not have a government solvency problem.

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers