J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2093

February 15, 2011

Jonathan Zasloff: The Easy Way to Cut the Federal Deficit

JZ:

The Easy Way to Cut the Federal Deficit « The Reality-Based Community: One can debate the political pros and cons of President Obama’s proposed budget: Jonathan Chait does an excellent job here debating with — himself! But in fact there is a quite simple way to reduce federal spending by $47 billion a year as a conservative estimate: that old public health care option. Such things, however, cannot be discussed in polite company, so let’s just reduce Pell Grants, maternal and child health, and food safety inspections instead. Whew! Glad we dodged that bullet.

IAS 107: Revised Schedule

IAS 107: Intermediate Macroeconomics: U.C. Berkeley: Spring 2011:

J. Bradford DeLong, Dariush Zahedi

Introduction:

Tu Jan 18: The Four Branches of Macroeconomics (read ch. 1: Introduction to Macroeconomics).

Th Jan 20: Keeping Track of the Macroeconomy (read chs. 2 and 3: Measuring the Macroeconomy and Thinking Like an Economist).

Growth Economics:

Tu Jan 25: Economic Growth Overview (read ch. 4: The Theory of Economic Growth).

Th Jan 27: Why Is the World So Divergent? (read ch. 5: The Reality of Economic Growth) (problem set 1 due).

Tu Feb 01: Economic Growth since 1800.

Th Feb 03: The Efficiency of Labor/Spurring the Rate of Technological and Organizational Progress (problem set 2 due).

Depression Economics:

Tu Feb 08: Introduction to Depression Economics.

Th Feb 10: INSTRUCTOR SICK

Tu Feb 15: The Income-Expenditure Model (read chs. 6 and 9: Building Blocks of the Flexible-Price Model and The Income-Expenditure Framework) (problem set 3 due).

Th Feb 17: The Investment-Savings Model (read ch. 10: Investment, Net Exports, and Interest Rates) (problem set 4 due).

Tu Feb 22: The Central Bank, Interest Rates, and Financial Markets (read ch 11: Extending the Sticky Price Model).

Th Feb 24: The Financial Crisis and the Economic Downturn (problem set 5 due).

Tu Mar 01: Policies to Fight the Great Recession.

Th Mar 03: Price Stickiness (read chs. 8 and 12: Money, Prices, and Inflation and The Phillips Curve and Expectations) (problem set 6 due).

Midterm:

Tu Mar 08: Pre-Midterm Review.

Th Mar 10: Growth-and-Depression Midterm.

Inflation Economics:

Tu Mar 15: Inflation and the Phillips Curve

Th Mar 17: Expected Inflation and the Natural Rate of Unemployment.

Tu Mar 29: Monetary Policy Reactions (read ch. 13: Stabilization Policy).

Th Mar 31: From the Short-Run to the Long-Run (problem set 7 due).

Debt-and-Deficit Economics:

Tu Apr 5: The Government's Taxes and Spending.

Th Apr 7: Depression-and-Inflation Midterm

Tu Apr 12: Debt Economics: Crowding Out and Crowding In (read chs. 7 and 14: Equilibrium in the Flexible Price Model and The Budget Balance, the National Debt, and Investment).

Th Apr 14: The Long-Run Budget Problem (problem set 8 due).

Topics

Tu Apr 19: Topics.

Th Apr 21: Topics (problem set 9 due).

Tu Apr 25: Topics.

Final:

Th Apr 28: Final Review

Th May 12: 8-11: FINAL EXAM

Mark Thoma: The Bush Tax Cuts and the New Normal for Unemployment?

Mark Thoma:

Economist's View: "What Is the New Normal Unemployment Rate?": Justin Weidner and John Williams of the San Francisco Fed attempt to estimate the increase in the unemployment rate due to structural factors. They find the increase is relatively modest.... [A] large part of the problem is cyclical, not structural and it is expected that "significant labor market slack will persist for several years." That calls for more aggressive policy from Congress, but that is unlikely to happen.

The unwillingness of Congress to provide more help can be traced in large part to the shape of the budget when the crisis hit. With the tax cuts and the increase in government expenditures for wars and other things during the Bush administration, the budget was in poor shape even before the crisis hit. When the crisis did hit, the poor shape of the budget led to an initial stimulus package that was much too small, and there was very little follow up when it became clear that the initial stimulus was insufficient. Now, although the the economic limits have not been reached -- helping the unemployed would have little impact on the long-run budget problem -- it appears that the political limits have been reached and more help for the unemployed is all but out of the question.

Thus, while the Bush tax cuts did very little to spur economic growth, they were costly, and those costs go beyond the hole in the budget caused by the cuts. The resulting budget problems also limited our ability to respond to the recession, and all of the additional struggles that households will endure because we were unable to give them the help they need are part of the Bush tax cut legacy.

The Tech Bubble Was a Good Thing

I agree with Tim Duy here. We got a lot of business-model development, a lot of fiber installed, and a huge amount of social surplus created by the tech bubble--the only thing missing were the returns to investors.

Tim Duy:

Economist's View: "The Upside of the Tech Bubble": I think [Felix] Salmon goes a bit far when describing the tech stock bubble of the 1990s:

The NYSE is place for algorithms and speculators to make bets on financial assets. It last funneled real amounts of money into the broader economy during the dot-com boom, leaving behind a lot of Aeron chairs and little else.

I have gone back and forth on this topic.... But when you scrape away the detritus, you find the building blocks of all the technology that is increasingly integrated in our everyday life. The bubble-driven intensity of activity in information technology almost certainly accelerated its development and adaptation. Many news ideas were explored; some failed, some succeeded. The successes, however, outweighed the failures, leaving productivity much higher as a result (that this productivity has not translated into higher real wages, however, remains a disappointment).... [T]he tech bubble was a wild ride, but I am wary about declaring it an absolute failure of the capital allocation process.

Kate Sheppard: Republicans in South Dakota Legislature Call to Legalize Killing Doctors, Nurses, and Receptionists

Kate Sheppard:

South Dakota Moves To Legalize Killing Abortion Providers | Mother Jones: A law under consideration in South Dakota would expand the definition of "justifiable homicide" to include killings that are intended to prevent harm to a fetus.... The Republican-backed legislation, House Bill 1171, has passed out of committee on a nine-to-three party-line vote, and is expected to face a floor vote in the state's GOP-dominated House of Representatives soon.

The bill, sponsored by state Rep. Phil Jensen, a committed foe of abortion rights, alters the state's legal definition of justifiable homicide by adding language stating that a homicide is permissible if committed by a person "while resisting an attempt to harm" that person's unborn child or the unborn child of that person's spouse, partner, parent, or child.... Jensen did not return calls to his home or his office requesting comment on the bill, which is cosponsored by 22 other state representatives and four state senators....

The original version of the bill did not include the language regarding the "unborn child"; it was pitched as a simple clarification of South Dakota's justifiable homicide law. Last week, however, the bill was "hoghoused"—a term used in South Dakota for heavily amending legislation in committee—in a little-noticed hearing. A parade of right-wing groups—the Family Heritage Alliance, Concerned Women for America, the South Dakota branch of Phyllis Schlafly's Eagle Forum, and a political action committee called Family Matters in South Dakota—all testified in favor of the amended version of the law...

A Republic, If You Can Keep It...

Back in nineteenth-century western Europe--back when the laboring classes and the dangerous classes did not have the franchise--the material interests of the laboring classes and the dangerous classes entered the political calculus through revolutionary threat: D'Israeli and Gladstone and Napoleon III and Bismarck and company were extremely anxious to produce broad-based economic growth lest 1793 come again.

And today? How do the material interests of America's laboring classes and dangerous classes enter the political calculus today?

Matthew Yglesias:

Yglesias » The Base and Bloggers:One of the most important facts about present-day American politics is that poor people have essentially no political “voice” in Washington. They do, however, vote. And they’re also human beings with moral worth and interests who count. What often winds up happening is that you get liberal bloggers, whose opinions about things are easy to find out since we publish them on the Internet, used as a generalized proxy for a huge swathe of the electorate. Hence this kind of thing from Michael Shear [of the New York Times]:

One liberal supporter who listened to the [conference] call described it as “mostly boring,” an indication that the president’s base was not particularly upset about the budget. During the call, Mr. Plouffe also offered some comfort to the bloggers by suggesting that Mr. Obama is not interested in big reductions in Social Security.

As a colleague of mine snarks, “because if one thing is indicative of how poor people feel about cuts, it’s white upper class bloggers.”

Right. As best I can tell the electoral base of the Democratic Party continues to be low-income people and racial minorities. Obviously better-off white people with idiosyncratic ideological motivations also play an important role in progressive politics on a practical level. But I often thought during the health care debate that poor people would be saying:

hell no I’m not going to give up this Medicaid expansion so you can hold out indefinitely for a public option.

Conversely, the political tactics of calling for an overall discretionary budget freeze while insisting on investments in energy, infrastructure, and education has a lot of merit but it necessarily entails taking the hammer to programs that subsidize consumption for poor people. I kind of doubt that all that many LIHEAP recipients eagerly downloaded the budget yesterday morning and then blogged about it in the afternoon and got on a press call in the evening.

February 14, 2011

Berkeley Friday Afternoon Political Economy Colloquium: Friday February 18, 2011: "Austerity" in the Context of the Global Economic Downturn

Spring 2011: Alternate Fridays 2-4 PM

Sponsored by the Blum Center on Developing Economies, the Political Economy Major, and the Institute for New Economic Thinking through the Berkeley Economic History Lab

February 18, 2011: "Austerity" in the Context of the Global Economic Downturn

Topic:

For nearly 200 years economists from John Stuart Mill through Walter Bagehot and John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman to Ben Bernanke have known that a depression caused by a financial panic is not properly treated by starving the economy of government purchases and of money. So why does "austerity" have such extraordinary purchase on the minds of North Atlantic politicians right now?

Panel:

Chair: J. Bradford DeLong, UCB Economics

Speaker: Joseph Lough, UCB Political Economy

Speaker: Rakesh Bhandari, UCB Interdisciplinary Studies

Location: Blum Hall Plaza Level

Time: 2:10-2:40: Panelists. 2:40-3:10: Discussion. 3:10-4:00: Reception.

Let me speak as a card-carrying neoliberal, as a bipartisan technocrat, as a mainstream neoclassical macroeconomist--a student of Larry Summers and Peter Temin and Charlie Kindleberger and Barry Eichengreen and Olivier Blanchard and many others.

We put to one side issues of long-run economic growth and of income and wealth distribution, and narrow our focus to the business cycle--to these grand mal seizures of high unemployment that industrial market economies have been suffering from since at least 1825. Such episodes are bad for everybody--bad for workers who lose their jobs, bad for entrepreneurs and equity holders who lose their profits, bad for governments that lose their tax revenue, and bad for bondholders who see debts owed them go unpaid as a result of bankruptcy. Such episodes are best avoided.

From my perspective, the technocratic economists by 1829 had figured out why these semi-periodic grand mal seizures happened. In 1829 Jean-Baptiste Say published his Course Complet d'Economie Politique... in which he implicitly admitted that Thomas Robert Malthus had been at least partly right in his assertions that an economy could suffer from at least a temporary and disequliibrium "general glut" of commodities. In 1829 John Stuart Mill wrote that one of what was to appear as his Essays on Unsettled Questions in Political Economy in which he put his finger on the mechanism of depression.

Semi-periodically in market economies, wealth holders collectively come to the conclusion that their holdings of some kind or kinds of financial assets are too low. These financial assets can be cash money as a means of liquidity, or savings vehicles to carry purchasing power into the future (of which bonds and cash money are important components), or safe assets (of which, again, cash money and bonds of credit-worthy governments are key components)--whatever. Wealth holders collectively come to the conclusion that their holdings of some category of financial assets are too small. They thus cut back on their spending on currently-produced goods and services in an attempt to build up their asset holdings. This cutback creates deficient demand not just for one or a few categories of currently-produced goods and services but for pretty much all of them. Businesses seeing slack demand fire workers. And depression results.

What was not settled back in 1829 was what to do about this. Over the years since, mainstream technocratic economists have arrived at three sets of solutions:

Don't go there in the first place. Avoid whatever it is--whether an external drain under the gold standard or a collapse of long-term wealth as in the end of the dot-com bubble or a panicked flight to safety as in 2007-2008--that creates the shortage of and excess demand for financial assets.

If you fail to avoid the problem, then have the government step in and spend on currently-produced goods and servicesin order to keep employment at its normal levels whenever the private sector cuts back on its spending.

If you fail to avoid the problem, then have the government create and provide the financial assets that the private sector wants to hold in order to get the private sector to resume its spending on currently-produced goods and services.

There are a great many subtleties in how a government should attempt to do (1), (2), and (3). There is much to be said about when each is appropriate. There is a lot we need to learn about how attempts to carry out one of the three may interfere with or make impossible attempts to carry out the other branches of policy. But those are not our topics today.

Our topic today is that, somehow, all three are now off the table. There is right now in the North Atlantic no likelihood of reforms of Wall Street and Canary Wharf to accomplish (1) and diminish the likelihood and severity of a financial panic. There is right now in the North Atlantic no likelihood at all of (2): no political pressure to expand or even extend the anemic government-spending stimulus measures that have ben undertaken. And there is right now in the North Atlantic little likelihood of (3): the European Central Bank is actively looking for ways to shrink the supply of the financial assets it provides to the private sector, and the Federal Reserve is under pressure to do the same--both because of a claimed fear that further expansionary asset provision policies run the risk of igniting unwarranted inflation.

But there is no likelihood of unwarranted inflation that can be seen either in the tracks of price indexes or in the tracks of financial market readings of forecast expectations.

Nevertheless, you listen to the speeches of North Atlantic policymakers and you read the reports, and you hear things like:

“Obama said that just as people and companies have had to be cautious about spending, ‘government should have to tighten its belt as well...’”

Now there were—and perhaps there still are—people in the White House who took these lines out of speeches as fast as they could But the speechwriters keep putting them in, and President Obama keeps saying them, in all likelihood because he believes them.

And here we reach the limits of my mental horizons as a neoliberal, as a technocrat, as a mainstream neoclassical economist. Right now the global market economy is suffering a grand mal seizure of high unemployment and slack demand. We know the cures--fiscal stimulus via more government spending, monetary stimulus via provision by central banks of the financial assets the private sector wants to hold, institutional reform to try once gain to curb the bankers' tendency to indulge in speculative excess under control. Yet we are not doing any of them. Instead, we are calling for "austerity."

John Maynard Keynes put it better than I can in talking about a similar current of thought back in the 1930s:

It seems an extraordinary imbecility that this wonderful outburst of productive energy [over 1924-1929] should be the prelude to impoverishment and depression. Some austere and puritanical souls regard it both as an inevitable and a desirable nemesis on so much overexpansion, as they call it; a nemesis on man's speculative spirit. It would, they feel, be a victory for the Mammon of Unrighteousness if so much prosperity was not subsequently balanced by universal bankruptcy.

We need, they say, what they politely call a 'prolonged liquidation' to put us right. The liquidation, they tell us, is not yet complete. But in time it will be. And when sufficient time has elapsed for the completion of the liquidation, all will be well with us again.

I do not take this view. I find the explanation of the current business losses, of the reduction in output, and of the unemployment which necessarily ensues on this not in the high level of investment which was proceeding up to the spring of 1929, but in the subsequent cessation of this investment. I see no hope of a recovery except in a revival of the high level of investment. And I do not understand how universal bankruptcy can do any good or bring us nearer to prosperity...

I do not understand it either. But many people do. And I do not understand why such people think as they do. So let me turn it over to the first of our speakers, Joseph Lough, to try to provide some answers.

Paul Krugman: There Is No Structural Shift to Cause Unemployment

Paul Krugman:

Who's Unemployed?: Larry Mishel emails me to second my concern about Charles Plosser’s blithe assertion that unemployment is about shifting workers out of construction. As Larry points out, the BLS provides data on the previous employment of the unemployed. There were 7.7 million more unemployed workers in 2010 than there were in 2007; of those extra 7.7 million, only 1.1 million had previously been employed in construction.... [H]ere’s the increase in unemployment 2007-2010 by industry of previous employment. See the structural shift? Neither do I. As others have noted, basically unemployment doubled for every industry, every occupation, every state. Where are the sectors/occupations/regions gaining jobs? Nowhere to be found. There’s nothing structural about it.

Scott Lilly: John Boehner's Big Earmark

SL:

No, He Wouldn’t—Would He?: Leaders of the new majority in the House of Representatives promised to cut spending and eliminate earmarks. But House budget legislation filed Friday night contains a provision that looks very much like an earmark that would benefit the hometown and congressional district of Rep. John Boehner (R-OH), above.... [B]uried deeply in these 359 pages of ugly surprises is a provision that would mean one community in America would do a lot better than all of the others. The legislation added an estimated $450 million for a particular bit of defense spending that the Department of Defense did not ask for and does not want.

The item is a down payment that would obligate the federal government to future payments that could well be three or four times the increased spending added to this particular piece of legislation, with a big portion of the funds flowing to two cities in Ohio—Cincinnati, where Speaker of the House John Boehner (R-OH) grew up, and Dayton, the largest city in his congressional district. The money will go to pay the costs to General Electric Co.’s General Electric Aviation unit and the British-owned Rolls Royce Group for their development of an engine for the new Joint Strike Fighter aircraft—money that looks, feels, and smells very much like an earmark.

Should the Department of Defense end up paying the two companies to develop the engine it is hoped that they will then buy significant numbers of them for the aircraft. The problem that the Pentagon has with this plan for using tax dollars is that they already have an engine for the plane—an engine that was decided on when the contract for production of the plane was agreed to 10 years ago. But that does not deter union leaders, company executives, and local government officials in Dayton and Cincinnati from arguing their case....

The Pentagon insists GE’s second engine isn’t needed, that it has no use for it, and that further development is a waste of money. But the engine’s supporters in Congress—and Evendale, where GE employs more than 7,000—beg to differ...“It’s a huge issue. There’s a lot at risk here,” said Gary Jordan, president of United Aerospace Workers Local 647.

The increased funding added to the new House budget bill was done in a manner even more “stealthy” than the plane that the would-be engine hopes to power. It is believed to be mixed in with much larger spending totals in one or more of the bill’s military research and development accounts. Appropriations Defense Subcommittee Chairman Rep. C.W. Bill Young (R-FL) conceded to Reuters on Friday that "the bill that we're going to deal with next week has the money in it," referring to the GE-Rolls Royce engine...

Paul Krugman: Expansionary Fiscal Policy Was Never Tried

Paul Krugman:

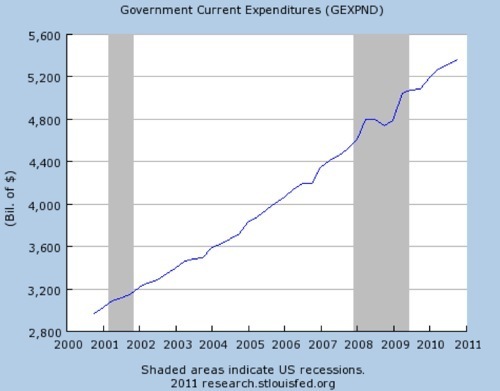

The Great Abdication: What is Obama saying here? The important thing, I think, is that he has effectively given up on the idea that the government can do anything to create jobs in a depressed economy. In effect, although without saying so explicitly, the Obama administration has accepted the Republican claim that stimulus failed, and should never be tried again. What’s extraordinary about all this is that stimulus can’t have failed, because it never happened. Once you take state and local cutbacks into account, there was no surge of government spending....

[T]he failure of the stimulus that never happened has become conventional wisdom — which is what I feared would happen, two years ago, when I was tearing my hair out over the inadequacy of the original plan.

Yes, I know, it’s argued that Obama couldn’t have gotten anything more. I don’t really want to revisit all of that; my point here is simply that everyone is drawing the wrong lesson. Fiscal policy didn’t fail; it wasn’t tried.

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers