Roger Crowley's Blog, page 5

April 1, 2014

‘Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages’

The first of April. Here in Gloucestershire soft sunlight and birdsong. Nothing summons up for me this sense of early spring so beautifully as the start of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales – eighteen lines, one seamless sentence – that links humans to the stirring of the natural world. Written at the end of the Fourteenth Century the opening of the prologue catches this moment of the year – the tender crops and the young sun, the singing of birds and the inevitable awakening in people to be out there, to see the world, to travel. If we feel this in our modern centrally heated houses, how much more powerful must it have been for medieval people, sewn into their clothes all winter, eating whatever starveling rations they could get, trying to keep warm – and then the astonishment of new life, the vivid colours of flowers, the softer breeze and the sun on their faces – and the more material comfort of food crops growing again.

‘Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

Whan Zephyrus eek with his sweet breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tender croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his halve cours yronne,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open ye

(So priken hem nature in hir corages):

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes,

And specially from every shires ende,

Of Engelond to Caunterbury they wende,

The hooly blissful martir for to seke,

That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.’

Pilgrimage was both a powerful spiritual surge, as it still is today, but it was also travel, adventure, the chance ‘to seken straunge strondes and sondry londes’ – of course with its attendant risks: the pilgrims in Chaucer’s tales ride together for mutual security. Some of the Christian pilgrim narratives of the middle ages, particularly those to the Holy Land, stand as the first European travel literature.

I really like the sound of Middle English; it has an authentic music. You can hear this passage – the opening of the prologue – read here, with some variation in text and spelling.

Published on April 01, 2014 09:10

March 20, 2014

'Life is an inn'

I have been to Dartmoor for the weekend in the spring sunshine. It can’t be said that the southern half of England has any sense of wilderness by North American standards, but Dartmoor is as good as it gets – a bleak, eroded, atmospheric plateau of moorland and granite tors, once covered with trees, and peppered with prehistoric standing stones and hut circles, moss covered boulders, craggy, gnarled trees bent by the wind, bogs and fast flowing streams.

Under a light blue sky it’s cheery and bright. In the mist – think of the terrifying howl of the Hound of the Baskervilles. It comes with its own legends. Whilst camping here years ago with a handy little guide to the ghosts of Dartmoor as my sleeping bag side reading I was particularly appalled by the Story of the Hairy Hands, which would clutch the shoulders of petrified motorists driving the long lonely roads at night and wrest the steering wheel into a death crash. It’s easy to see how Conan Doyle got inspired…

And I visited a lovely Cornish church – St Swithins at Luancells outside Bude – a typical granite church, with its own holy well (good for eye complaints), set above a small stream, among trees animated by cawing, nest-building rooks, daffodils and celandines and the first bees.

It’s perfect. Ancient tombstones carrying the names of long generations of the same families – before people got restless and lost the sense of place; ancient wooden pews, gnawed by time; the local gentry reclining in leisurely fashion in their comfortable wall monuments; a list of vicars reaching back 700 years – men who sound like characters from Arthurian legend: Sir John de Launcelas, Sir Philip de Romelode, Sir Baldwin Tybot (they were a titled lot in the Middle Ages) – and the splendidly named Sir Walter Cola; fifteen century floor tiles and cheery epitaphs on memorial slabs, such as this:

Life is an inn; think man this truth upon;Some only to breakfast and are quickly gone;

Others to dinner stay and are full fed;

The oldest man sups and goes to bed.

Large is his debt who lingers out his day;

Who goes the soonest has the least to pay.

I think the light-hearted message here (apart from living being a form of gluttony) is that the sooner you die, the fewer sins you have to work off. Phew.

Published on March 20, 2014 03:51

March 12, 2014

The Way of the World

In between writing, I'm reading The Way of the World

by Nicolas Bouvier, a book I've been putting off for years, in the perverse belief that it would prove too enjoyable. Which it does.

It's the tale of a road trip taken by two young Swiss, Bouvier and his friend Thierry Vernet, from Serbiato Afghanistanaround 1953-54. They travel in a small underpowered tin Fiat at about 15 mph - so slowly they have time to see everything, record the world around them. They have an accordion and a guitar and they play music with the gypsies; they paint and write and see the world afresh, as if for the first time.

Here's Bouvet, snowed into Tabriz in Iran for six months, on the subject of bread:

"At daybreak the smell of the ovens drifted across the snow to delight our noses; the smell of the round, red-hot Armenian loaves with sesame seeds; the heady smell of sanjak bread; the smell of lavash bread in fine wafers dotted with scorch marks. Only a really old country rises to luxury in such ordinary things; you feel thirty generations and several dynasties lined up behind such bread. With bread, tea, onions, ewe’s cheese, a handful of Iranian cigarettes and the leisurely pace of winter, we were set for a good life."

And here on the Turkish plateau at night on the edge of autumn, the memory of one of those special moments that travel brings:

“East of Erzurum the road is very lonely. Vast distances separate the villages. For one reason or another we occasionally stop the car, and spend the rest of the night outdoors. Warm in big felt jackets and fur hats with ear-flaps, we listened to the water as it boiled on a primus in the lee of the wheel. Leaning against a mound, we gazed at the stars, the ground undulating towards the Caucasus, the phosphorescent eyes of the foxes.

Time passes in brewing tea, the odd remark, cigarettes, the dawn came up. The widening light caught the plumage of quails and partridges...and quickly I dropped this wonderful moment to the bottom of my memory, like a sheet anchor that one day I could draw up again. You stretch, pace to and fro feeling weightless, and the word ‘happiness’ seems too thin and limited to describe what happened.

In the end the bedrock of existence is not made up by the family or work or what others say or think about you, but of moments like this when you are exalted by a transcendent power that is more serene than love. Life dispenses them parsimoniously; our feeble hearts could not stand more.”

When I get to the end I’ll probably start again.

[image error]Nicolas Bouvier on the road in Turkey

It's the tale of a road trip taken by two young Swiss, Bouvier and his friend Thierry Vernet, from Serbiato Afghanistanaround 1953-54. They travel in a small underpowered tin Fiat at about 15 mph - so slowly they have time to see everything, record the world around them. They have an accordion and a guitar and they play music with the gypsies; they paint and write and see the world afresh, as if for the first time.

Here's Bouvet, snowed into Tabriz in Iran for six months, on the subject of bread:

"At daybreak the smell of the ovens drifted across the snow to delight our noses; the smell of the round, red-hot Armenian loaves with sesame seeds; the heady smell of sanjak bread; the smell of lavash bread in fine wafers dotted with scorch marks. Only a really old country rises to luxury in such ordinary things; you feel thirty generations and several dynasties lined up behind such bread. With bread, tea, onions, ewe’s cheese, a handful of Iranian cigarettes and the leisurely pace of winter, we were set for a good life."

And here on the Turkish plateau at night on the edge of autumn, the memory of one of those special moments that travel brings:

“East of Erzurum the road is very lonely. Vast distances separate the villages. For one reason or another we occasionally stop the car, and spend the rest of the night outdoors. Warm in big felt jackets and fur hats with ear-flaps, we listened to the water as it boiled on a primus in the lee of the wheel. Leaning against a mound, we gazed at the stars, the ground undulating towards the Caucasus, the phosphorescent eyes of the foxes.

Time passes in brewing tea, the odd remark, cigarettes, the dawn came up. The widening light caught the plumage of quails and partridges...and quickly I dropped this wonderful moment to the bottom of my memory, like a sheet anchor that one day I could draw up again. You stretch, pace to and fro feeling weightless, and the word ‘happiness’ seems too thin and limited to describe what happened.

In the end the bedrock of existence is not made up by the family or work or what others say or think about you, but of moments like this when you are exalted by a transcendent power that is more serene than love. Life dispenses them parsimoniously; our feeble hearts could not stand more.”

When I get to the end I’ll probably start again.

[image error]Nicolas Bouvier on the road in Turkey

Published on March 12, 2014 07:20

February 26, 2014

'Everything we experience as a gift we should pass on'

Yesterday I read the obituaries and articles about this wonderful woman, Alice Herz-Sommer. the oldest survivor of the Holocaust who had died aged 110 - who lived her life through music and without hatred: 'I have had such a beautiful life'. A couple of articles and obituaries here:

'She had no hatred in her'

Obituary

And a Youtube moment - she began each day practising Bach and Beethoven

Published on February 26, 2014 09:01

February 20, 2014

The Sons of Sindbad

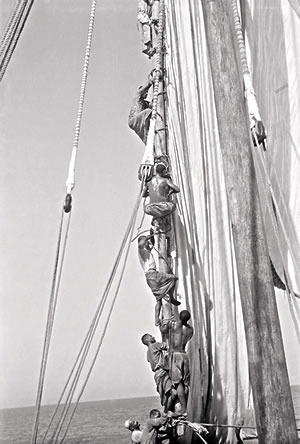

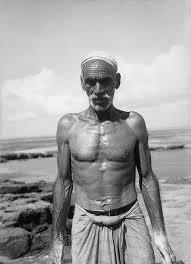

I have been deep in the Indian Oceanrecently – from the safety of my armchair, enraptured by a book called Sons of Sindbad by Allan Villiers. Villiers was an Australian master mariner, writer and photographer, who sailed and documented the last days of wind-powered navigation. In 1938-39, sensing the end of an era, he spent six months on an Arab dhow, sailing from Kuwait, down the coast of East Africa and back again.

It’s a fascinating read – Villiers is the Wilfred Thesiger of the Arabian Seas– experiencing the traditional life of Indian Oceanseafaring that stretched back thousands of years. He arranged passage on a big wooden dhow, The Triumph of Righteousness, living with the crew, learning Arabic and observing and participating in the working life of the ship, under its stern and imperious captain, Nejdi. The Triumph made no concessions to modernity. It had no radio, no navigational equipment beyond a compass, – and no lights at night. The great triangular lateen sail was manhandled by the crew who performed extraordinary feats of physical endurance. Everyone slept on deck under the stars – or in the rain – as the ship made its way down the coast of East Africa, trading, ferrying passengers and smuggling. At times it was unbearably cramped and Villiers does not romanticise the conditions. They transported a large party of Bedouin – 180 people in all – cramped onto an open deck 70 feet long all the way to Mombasa. The few women were stashed away in a malodorous rat infested cabin. Fully loaded with passengers the ship stank – a combination of fish oil, vomit and bilge water - and the food – rice and fermenting fish – cooked in a sandbox was at best monotonous. In this floating souk, goats are slaughtered, the Bedouin are seasick, quarrels break out – quelled by Captain Nejdi with a slashing cane. In the harem cabin a girl dies. Villiers with his small medicine chest is looked upon to pronounce the cause of death. The most likely explanation is poison – administered by a jealous rival.

Villiers does not romanticise the voyage but he was enthralled by the experience. He appreciated the extraordinary skill, fortitude and dignity of the crew and their captain, their handling of the ship and the timeless rhythm of the voyage. When a Bedouin boy is knocked off the ship into a shark infested sea, two sailors spontaneously dive in after him; Nejdi executes a skilful manoeuvre turning the ship round in the lee of a rocky shore; no one panics. The child is rescued. No one says a word. The sailors go back to work.

And there is always work to do – raising and lowering the sails, mending them, plaiting ropes; periodically the ship has to be hauled out of the water, the hull scraped down and coated with fish oil and camel tallow. Sleep is in snatches. The life is so hard that a man of thirty looks fifty. Five times a day they are led in prayer – and as they work they sing and dance, hammering the deck with their bare calloused feet, so loudly that sometimes the orders from the wheel are inaudible. They sing as they haul the sails up and down, they sing and dance as they enter and leave port to the banging of drums. They sing to the sails and they sing to their captain in a deep rumbling chant:

And there is always work to do – raising and lowering the sails, mending them, plaiting ropes; periodically the ship has to be hauled out of the water, the hull scraped down and coated with fish oil and camel tallow. Sleep is in snatches. The life is so hard that a man of thirty looks fifty. Five times a day they are led in prayer – and as they work they sing and dance, hammering the deck with their bare calloused feet, so loudly that sometimes the orders from the wheel are inaudible. They sing as they haul the sails up and down, they sing and dance as they enter and leave port to the banging of drums. They sing to the sails and they sing to their captain in a deep rumbling chant:“Nejdi has brought us here,

Nejdi, good master:

Thanks be to Allah,

Always the merciful.”

And at the end of each day they present themselves at the poop to ask their captain's blessing. There is no set itinerary. Villiers gives up asking exactly where they are going or how long they will stay in port. During a lunar eclipse, the whole ship is filled with superstitious dread and falls to its knees to pray for the return of the 'Prophet's Lantern'. It is an ancient world.

Sometimes the experience is ghastly – they spend a month in the delta of a miasmic tropical river, collecting mangrove poles to transport back to Kuwaitfor building projects. It rains continuously. The mosquitoes gather in swarms. There is no protection from them day or night. The men go down with fever. And the work is incredibly hard. Villiers is hit on the head by an object falling from the mast and blinded for a week. No one gives an explanation for the accident – everything is as Allah wills. But when the Triumph approaches Zanzibarrising excitement infects the crew. They don their best clothes, sing the ship in and depart to spend what money they have in the town’s brothels. Smugglers come and go at night.

Sometimes the experience is ghastly – they spend a month in the delta of a miasmic tropical river, collecting mangrove poles to transport back to Kuwaitfor building projects. It rains continuously. The mosquitoes gather in swarms. There is no protection from them day or night. The men go down with fever. And the work is incredibly hard. Villiers is hit on the head by an object falling from the mast and blinded for a week. No one gives an explanation for the accident – everything is as Allah wills. But when the Triumph approaches Zanzibarrising excitement infects the crew. They don their best clothes, sing the ship in and depart to spend what money they have in the town’s brothels. Smugglers come and go at night. The dhow captains smoke their hookahs as they sail their ships and yarn in coffee shops when they land. The sailors have almost nothing; many of them are permanently in debt to captains and merchants. At the end of the voyage some of them are compelled to the most dreadful of occupations – pearl diving in the Persian Gulf – that surpassed any maritime suffering Villiers had ever seen – a kind of bonded labour that kills men even faster than sailing the big dhows.

But sometimes the voyage is an enchantment. Villiers is enraptured by the beauty of these ships bowling along with a good wind like enormous white butterflies and the extraordinary craft skills of the sailors and navigators: “Nejdi had no tables and he did not even know the date. The moon, he said was enough; the moon, the stars and the behaviour of the sea.”

[image error]

It’s a moving snapshot of a vanished world. These boats were at the end of a lineage stretching far back into antiquity. The voyaging cost almost nothing beyond the labour of the men and a Spartan diet. The ancient cosmopolitan trading patterns were slowly being extinguished by colonial rule and nation states, by steel ships with diesel engines and the oil boom in the Gulf States that will take men away from the seafaring life.

Thirty years later Villiers returned to Kuwait. He met Nejdi, now a rich man, at the airport. Villiers recalled the meeting.

“Allah is great,” I said. “His winds are free.”

“Allah is great,” Nejdi replied…”and sometimes I wish that I could use His winds again. For it was a good life that my sons can never know – no Kuwaitsons shall know. We cannot bring those ways back again.”

“Swell out, great sail,

And gather to your breast

God's wind,

For we are bound for home”.

Published on February 20, 2014 14:36

February 2, 2014

A word from the sultan

In 1849, a British admiral, Sir Adolphus Slade, was seconded to the Ottoman sultan in Istanbul, where he served for seventeen years as administrative head of the navy. He wrote extensively about his experiences and travels. The Ottoman empire was in serial decline, already the Sick Man of Europe, trying to modernise itself amongst the rapidly developing industrial nations of Western Europe – at a time when Queen Victoria sat on the throne of England - yet still bound to the oriental practices of despotic sultans that stretched far into the past .

Probably no event impressed on Slade the character, institutions and power of the sultans so strongly as the fate of an Ottoman official, called Hamid.

Slade had a house on the Bosporus, looking out over the water. Hamid was his neighbour. The admiral recalled the fateful day in vivid detail.

“Poor Hamid, peace to his errors! I knew him well. The evening before his catastrophe we smoked a pipe together. Late that night the captain pasha [admiral of the fleet] returned from Constantinople, where he had been assisting at a divan [sultan’s council], with the fatal order in his bosom.

The next morning, the sun just peeping over the Asiatic hills, I saw a barge row swiftly from the flag-ship to the nazir’s [official’s] house, which overhung the water. Suspecting something I put a question to the officer of the boat, as he passed my window. He shook his head in reply.

The nazir was still reposing.

“The pasha wants you,” was the pithy reply.

“Why, what can he require?”

“You will soon learn. Rise.”

He adjusted his dress, performed his ablutions, prayed and stepped into the barge. I was already dressed and on the quay; passing which, he waved his hand to me, and said something, I thought “farewell’, so I took a caique and followed.

The principal officers of the fleet received him on the quarterdeck; the man whose smiles they courted the day before, they received with insults. Hassan, rialabey, gave him a kick. At this he crossed his hands and exclaimed, “I understand.”

He was then conducted down onto the main deck; there his accusation was read to him, amongst others, the unjust one of grinding the poor. He betrayed no fear, neither probably, would he have said one word, had not the captain pasha at that moment come out of his cabin to look at his old friend, who, one little spark still yet burning amongst the embers of hope, cried once, “Aman!” [mercy].

He might have spared his breath. The pasha answered by a slight wave of the hand, the usual signal in such cases. The guards understood it, and taking the nazir by the arms, led him below to the prison, where two slaves attended.

Not thinking for a moment that he was going straight to death, I was about to follow, moved by an impulse of pity or curiosity, when the pasha motioned me to come into his cabin. The bowstring soon did its task, and in a few minutes, the receipt, poor Hamid’s head, the countenance calm as in sleep, was brought up to be shown to the pasha before being transmitted to the seraglio [palace].

It is startling to see a human head carried in a platter up the ladder, down which you had seen it descend, just before, sentient and well posed on a pair of shoulders. This had an effect even on the cold-blooded Osmanleys under the half-deck. They involuntarily shuddered, as well they might: the reign of terror was begun, when no man might say that his turn would not come next.”

The sultan always required visible proof that his orders had been carried out. Neatly presented in a silken bag.

Published on February 02, 2014 09:50

January 22, 2014

'I smelt history'

It’s the kind of Indiana Jones moment that we all might dream of – I certainly did as a child, reading popular archaeology books about the discovery of Tutankhamun ‘s tomb and the pyramids of ancient Egypt. The moment when you make hole in the stone slab and peer down through the darkness of thousands of years to glimpse something quite extraordinary.

That moment came to the Egyptian archaeologist Kamal el-Mallakh in the spring of 1954. Workmen clearing debris around the base of the Great Pyramid of Giza hit upon a stone structure: forty-one limestone blocks with carefully mortared seams. El-Mallakh chiselled a hole in one of the blocks and peered down inside. A rectangular stone pit. Darkness. And an aroma rising from dry earth. He could make nothing out. ‘And then with my eyes closed, I smelt incense, a very holy, holy, holy smell. I smelt time…I smelt centuries…I smelt history.’

What El-Mallakh had found was not a glittering gold-masked mummy but something in its own way as valuable and miraculous. A boat – dry stored and completely intact in the airtight tomb – the funeral vessel of the pharaoh Khufu. The boat had been disassembled; but all the pieces were there, laid out intact as if they had been just cut. Forty-four metres long, constructed almost entirely with cedars from Lebanon, the pieces marked with carpenters’ symbols to aid its assembly, a construction as astonishing in its own way as the pyramids themselves. A testament to the technologies of the ancient Egyptians.

It took nearly thirty years to reconstruct this three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle, sewing it back together, as it had been, with five thousand metres of cordage – the traditional method of boat construction in large parts of the world, particularly the Indian Ocean, right into modern times.

Original rope from the boat made from grass

Original rope from the boat made from grassThis long slim processional craft might once have transported Khufu’s embalmed body to Giza –or been specially built to carry him on a journey into the afterlife. It has a deckhouse to the stern, then a light frame to support an awning, shielding the pharaoh from the fierce heat of the sun; its raised prow echoes the shape of the papyrus boats that once plied the Nile. The frustration of maritime archaeologists is that often so little survives of ancient ships - much is just guesswork based on out-of-

Published on January 22, 2014 03:41

January 13, 2014

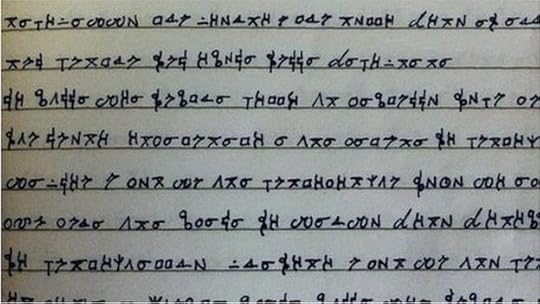

More from the mafia

This mysterious, neatly drawn secret code , found recently during the investigation of a Rome murder case, has become the subject of wide interest. It took two policemen with a fascination with crosswords several weeks to crack the invented alphabet. It's the formula for the initiation ceremony into the 'Ndrangheta, the criminal organisation based in Calabria in southern Italy now challenging the Sicilian Cos Nostra for supremacy amongst the Italian mafia clans. It's a rare glimpse into the inner world of mafia recruitment and affiliation - as reported in a BBC article recently.

Published on January 13, 2014 10:20

December 31, 2013

'Thus ends this year of public wonder and mischief'

I have been reading my way incredibly slowly - that is over a course of years - through the so-called Shorter Pepys (just 1000 pages -a third of the original diary). I read a chunk, put the marker in, then return to it at the same point a year or two later. It's a long term project, exploring the uncensored inner world of this complex, energetic man: ravenously alive, insatiably curious, egotistical, vain, compassionate and completely human. And I've got to 1666 - the year of the great fire of London, of which he wrote an extraordinarily vivid account.Pepys was methodical as well as spirited. On the last day of each year, he totted up his accounts, both financial and non-material. 1666 sees him extremely well-off. He has 6200 pounds - 1800 more than the previous year. It's unclear exactly where this money comes from - many of the nuances of his daily dealings pass over my head - but it seems he takes bribes in the course of his work, as secretary to the Navy Board concerned with the awarding of supply contracts during a tense period of war with the Dutch, yet at the same time, as a civil servant he's also outstandingly industrious, efficient and intelligent - by the standard of the times - and loyal to two kings, Charles II and James II, patently unworthy of respect. As the diary is written in a form of encoded shorthand he’s breathtakingly frank about himself – and other people, both low and high.'Thus ends this year of public wonder and mischief to this nation - and therefore generally wished by all people to have an end. Myself and family well, having four maids , and one clerk, Tom, in my house...Our healths all well; only, my eyes, with overworking them, as sore as soon as candlelight comes to them, and not else. Public matters in a most sad condition. Seamen discouraged for want of pay, and are become not to be governed...Our enemies, French and Dutch, great, and grow more, by our poverty. The Parliament backward in raising, because jealous of spending, of money. The City less and less likely to be built again, everybody settling elsewhere, and nobody encouraged to trade. A sad, vicious, negligent Court, and all sober men fearful of the ruin of the whole kingdom this next year - from which, good God deliver us.'And then, a typically, Pepysian cheering closing of the year’s account - moving from the state of the nation to worldly self-satisfaction: 'One thing I reckon remarkable in my own condition is that I am come to abound in good plate, so as at all entertainments to be wholly served with silver plates, having two dozen and a half.'Over the reach of three hundred years he gazes out at us from a portrait he had commissioned, and of which he was deeply proud, holding a musical composition of his own - he was not backward in praising his own songs - in a coat that has the sheen of prosperity to it. He looks sensuous, vain, inquisitive, interested, human. Happy New Year.

.

.

Published on December 31, 2013 08:44

December 20, 2013

An interview with Robert Horvat

Recently Robert Horvat, who writes a mean history blog - and far more attentively than I do, asked me some questions about history and writing. Here are the replies , woven around his own commentary. I'm not sure about being 'Narrative History's Man of the moment' - more like someone who writes the occasional book very slowly! Just now I'm crawling over the surface of the Portuguese history of two decades in the Indian Ocean during the early sixteenth century - though it's fascinating, and a privilege to be able to do such things.

Published on December 20, 2013 23:23

Roger Crowley's Blog

- Roger Crowley's profile

- 820 followers

Roger Crowley isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.