Roger Crowley's Blog, page 3

June 22, 2015

Greek tragedies

Storm clouds over the Parthenon. As Greece continues to stagger on through its financial crises I found myself going back through some of my photographs and stumbled upon the cheery image of the Greek flag waving in the Aegean wind on the ferry from Santorini to Piraeus:

And uninhabited islands rising like mirages out of the sea:

And remembered too some words of the great Greek poet George Seferis, writing about his country's unhealed wounds:

Wherever I travel Greece wounds me,

curtains of mountains, archipelagos, naked granite.

They call the one ship that sails AG ONIA 937.

Let's hope for the best for Greece - and the whole of Europe.

And uninhabited islands rising like mirages out of the sea:

And remembered too some words of the great Greek poet George Seferis, writing about his country's unhealed wounds:

Wherever I travel Greece wounds me,

curtains of mountains, archipelagos, naked granite.

They call the one ship that sails AG ONIA 937.

Let's hope for the best for Greece - and the whole of Europe.

Published on June 22, 2015 01:00

May 28, 2015

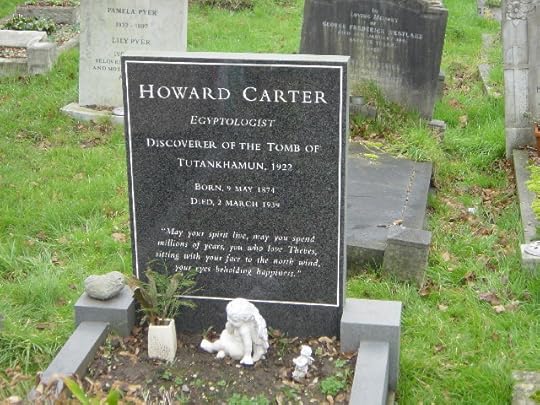

An epitaph

"May your spirit live,

May you spend millions of years,

You who love Thebes,

Sitting with your face to the north wind,

Your eyes beholding happiness."

A small cutting from a newspaper fell out of one of my old notebooks recently with this lovely epitaph to someone. I had no idea where it came from. A quick google revealed that it's an inscription on a wonderful alabaster cup from Tutankhamun's tomb:

Howard Carter had to step over it as he entered the antechamber of the tomb for the first time, and it forms his own epitaph too.

May you spend millions of years,

You who love Thebes,

Sitting with your face to the north wind,

Your eyes beholding happiness."

A small cutting from a newspaper fell out of one of my old notebooks recently with this lovely epitaph to someone. I had no idea where it came from. A quick google revealed that it's an inscription on a wonderful alabaster cup from Tutankhamun's tomb:

Howard Carter had to step over it as he entered the antechamber of the tomb for the first time, and it forms his own epitaph too.

Published on May 28, 2015 23:35

April 10, 2015

Two hours, ten minutes of war

Recently I unearthed a copy of a letter written during the First World War – exactly a hundred years ago, in 1915 – from my great-uncle to his sister, my grandmother. Charles Hudson was a British officer serving on the Western Front at the Ypres salient. He was a daredevil, addicted to adventure, and not beyond disobeying orders. To offset the passive endurance of trench warfare, he had developed a taste for ‘night crawling’ – creeping out in the dark, usually unarmed, and accompanied by one of his men to inspect enemy positions and cut their barbed wire. On one occasion he finds himself peering through a chink into a German dugout: ‘The door in the trench was open…the men in the dugout lit a candle as the door closed and in the light I could see the men opposite me quite distinctly. Three sat in a row on a bench. I had never seen the enemy, other than prisoners, at a range of a few feet and I was vastly intrigued. Then a man just the other side of the wall shifted his position so that the back of his neck blocked my view. I blew gently and the man scratched his neck but did not move.’!

The letter to my grandmother details his next - illegal - excursion. I’ve shortened it somewhat but it’s a vivid, heart stopping account of living in the moment.

Dear Dolly,

You may be pleased to hear I was absolutely forbidden by the General to go again as I am Coy [Company] commander, rather rot for me but…

I went with Stafford again, at 4.30 am.

Conversation:

“Damned cold, Sergeant.”

“Yes Sir, moon’s a bit bright, but it will be going down soon.” “Yes Sir, better take some bombs.” “Yes Sir, shall I get them Sir?”

“We’ll pick them up at the listening post (in front). Sentries warned?”

“Yes Sir.”

So off we go through a covered gap in the parapet and down the ledge.

“Who’s that?” (whispered)

“Sherwood Foresters. Captain Hudson. All quiet Corporal?”

“Yes Sir.”

“We’re going out in front to the left.”

“Very well Sir.”

We are now 150 yards from Fritz and the moon is bright, so we bend and walk quietly onto the road running diagonally across the front into the Bosche line. There is a stream the far side of this – boards have been put down across it at intervals and must have fallen it – about 20 yards down we can cross. We stop and listen – Swish! – and down we plop (for a flare lights everything up). It goes out with a hiss and over the board we trundle on hands and knees.

Still.

Apparently no one has seen so we proceed to crawl through a line of ‘French’ wire. Now for 100 yards dead flat weed land with here and there a shell hole or old webbing equipment lying in little heaps! These we avoid. This means a slow, slow crawl head down, propelling ourselves by toes and forearm, body and legs flat on the ground, like a snake.

A working party of Huns are in their lair. We can just see dark shadows and hear the sergeant, who is sitting down. He’s got a bad cold! We must wait a bit, the moon’s getting low but it’s too bright. Now 5 a.m. They will stop soon and if we go on we may meet a covering party lying low.

5.10.

5.15.

5.25.

5.30.

And the moon’s gone.

“Got the bombs Sergeant?”

“No Sir, I forgot them!”

‘Huns’ and the last crawl starts.

The Bosch is moving and we crawl quickly on to the wire – past two huge shell holes to the first row…Out comes the wire cutter. I hold the strands to prevent them jumping apart when cut and Stafford cuts…Two or three tins are cut off as we go. (These tins are hung to give warning and one must beware of them)…

It is getting light, a long streak has already appeared…

Stafford has to extract me twice from the wire…He leads back down a bit of ditch.

Suddenly a sentry fires two shots which spit on the ground a few yards in front. We lie absolutely flat, scarcely daring to breathe – has he seen? Then we go on with our trophies [pieces of wire], the ditch gets a little deeper, giving cover! My heart beating 19 to the dozen – will it mean a machine gun? Stafford is gaining and leads by ten yards.

“My God,” I think, “it is a listening post ahead and this is the ditch to it. I must stop him.”

I whisper “Stafford, Stafford!” and feel I am shouting. He stops, thinking I have got it.

“Do you think it’s a listening post? There! By the mound – listen.”

“Perhaps we had better cut across to the left Sir.”

“Very well.”

This time I lead. Thank God, the ditch and the road over the ditch, and we run like hell, bent double. Suddenly I go a fearful cropper and a machine gun is rattling in the distance and the streak is getting bigger every minute.

“Are you all right Sir?” From Stafford.

I laugh, “Forgot that damned wire.” (Our own wire outside our listening post.)

Soon we are behind the friendly parapet and it is day. We are ourselves again, but there’s a subtle cord between us, stronger than barbed wire, that will take a lot of cutting. Twenty to seven, 2 hours 10 minutes of life – war at its best. But shelling, no, that’s death at its worst. And I can’t go again, it’s a vice. Immediately after I swear I’ll never do it again. The next night I find myself aching after ‘No Man’s Land’.

Some yarn I think, worse than the Wide World, tell me if it sounds realistic, it’s all the truth.

My nerve has quite come back again. I felt a bit shaky when I started…

Bye-bye

Ever your loving Brother

Charlie

Charles Hudson V.C.

Charles Hudson V.C.

Published on April 10, 2015 01:12

March 28, 2015

Tomas Tranströmer

When I heard of the death of Tomas Tranströmer, the Swedish Nobel prize winning poet, I fetched down my copy (English translation only!). I have no idea what his poems sound like in Swedish but I imagine that they translate well. He’s a writer who conjures a sense of place: the forests and snowy distances of Sweden, the mist-shrouded islands of the Baltic. There's a feeling of imminence in the pine trees and the deep silence, moments of mysterious epiphany and transcendence. A train stops suddenly at 2 a.m. on a lonely plain. 'Days - like Aztec hieroglyphs'. The impact of a death.

After someone’s deathOnce there was a shock

which left behind a long pallid glimmering comet's tail.

It contains us. It makes TV pictures blurred.

It deposits itself as cold drops on the aerials.

You can still shuffle along on skis in the winter sun

among groves where last year's leaves still hang

They are like pages torn from old telephone directories -

the subscriber's names are consumed by the cold.

It is still beautiful to feel your heart throbbing.

But often the shadow feels more real than the body.

The samurai looks insignificant

besides his armour of black dragon-scales.

(Translated by Robin Fulton)

Published on March 28, 2015 06:09

March 19, 2015

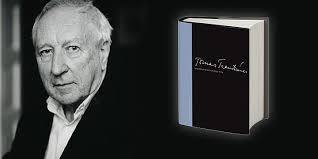

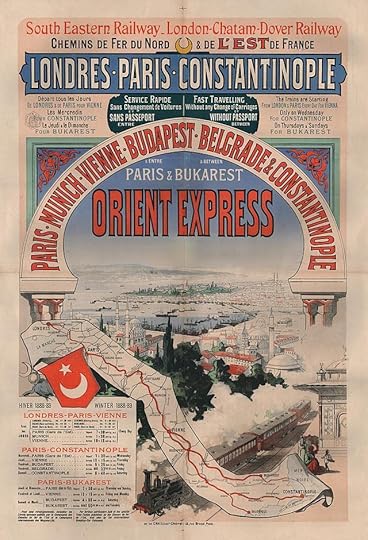

End of the line for Istanbul's Ottoman railway station?

Nostalgia comes in many forms. Quite high up the scale for me is the Haydarpaşa railway terminus in Istanbul. For over a century this magnificent ormolu late Ottoman edifice with its nods at art deco, has been the beginning and the end of journeys. It ‘s a place of grandeur and confusion – where Europe tilts into the Orient. It looks out over the sea: at the Galata bridge that spans the Golden Horn; at the fussy steamers smudging the sky with smoke as they ply the Bosphorus; at the swarms of people passing to; at the incessant buying, selling, loitering, fishing and travelling to and from mysterious destinations.

Through the Haydarpaşa ran the Berlin to Baghdad railway. The Orient Express ended here. It has seen pass along its platforms explorers, spies, soldiers, diplomats, refugees, gastarbeiter, pilgrims to Mecca – and the plain curious. Agatha Christie came on this line. Old postcards summon up a lost world of moustachioed porters, portmanteaux and the grand Pera Palace Hotel, fezzes and dragomans.

The Orient 'Express' brought me to and from Istanbul a few times in the 1970s – not a plush Pullman service, but a slow, low-grade clanking journey courtesy of the unreliable rolling stock of central Europe, two days sitting semi-upright, semi-comatose with brief stops to encounter the expensive air of Switzerland, the stern demeanour of Bulgarian customs officials, the offerings of food salesmen on the platforms of Belgrade and Sofia, the enjoyment and annoyance of fellow travellers.

The train came via Calais and Paris, Mussolini’s slab of a station in Venice and Tito’s Yugoslavia, through fields of sunflowers and wheat where headscarved women wielded large scythes, past beehives, tiny houses, flocks of birds, communist apartment blocks and sleeping dogs. And on into Istanbul, running along the shore, with the Sea of Marmara glittering in the sunlight on one side, on the other the crumbling walls of old Constantinople and the ruins of Byzantine palaces converted into shacks and metal bashing workshops. Finally, exhausted but exhilarated by this jumble of passing life, the train ushers you under the iron pillared canopy of the station – and Istanbul begins. You step out of the doors, startled and disorientated by the pounding of new sensations: the smell of frying fish, car exhaust, roasting chestnuts and sea water; the street cries of sellers of sesame rolls, lottery tickets, shoe shining services, football shirts and mobile phone services; the squabbling of gulls; the viscid, malodorous waters of the once Golden Horn – admittedly cleaner today than forty years ago. And the Galata Bridge across it, now a fixed structure, but until the 1990s a series of connected pontoons that rippled disconcertingly beneath your feet, evidence that Istanbul that possesses a vivid magic.

The last time I looked in, the Haydarpaşa was still receiving trains. Now it’s probably a shell. A new station has been constructed on the Marmara shore and the Haydarpaşa seems on the way to becoming a piece of real estate up for grabs to private interests. An 'accidental' fire ripped through its roof in 2010. Istanbul is falling prey to the blight of many big cities: the privatisation of public spaces, around which the protests in Taksim Square revolved, the squeezing out of the poor, the destruction of inconvenient but iconic buildings – an attack not quite on the scale of the Mafia’s sack of Palermo in the 1960s, but the cold hand of big money is clutching at the city's fabric. The Haydarpaşa came to mind because I read a Turkish blogger on all this.

‘It seems to me,’ said Pierre Gilles, a sixteenth century visitor, ‘that while other cities may be mortal, this one will remain as long as there are men on earth.’ Let’s hope.

Published on March 19, 2015 05:44

March 11, 2015

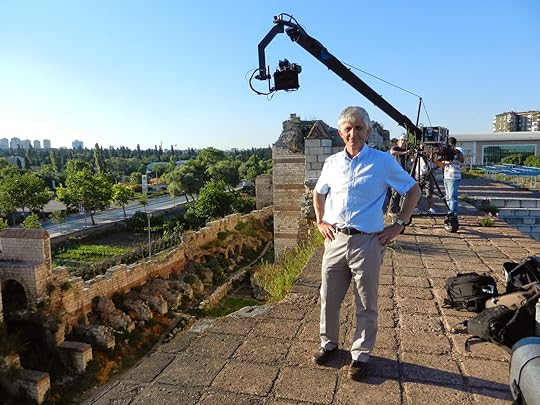

Ten years of history writing

I’ve been sitting at a desk writing history books for something over ten years . It’s been engrossing, demanding and occasionally exhausting. This is a good moment to take stock. What does it add up to? Four books in various languages (the last still in proof), thousands of pages of handwritten notes:

Despite the impressive number of different language versions it’s been a modest living not a handsome one – I’m still waiting for the film rights. People come by and take out options but I’ve become realistic. I spent three unpaid months writing outlines for a Game of Thrones style history epic based on one of my books at a publisher’s behest – no luck so far. There’s an element of gambling in all this – the next book could make it, a producer could get serious, but I’ve learned that seasoned punters read the odds – a history of Venice is never going to be Fifty Shades of Grey.

Writing about the history of the Mediterranean has its pluses and minuses. It’s not an area of heavy publishing traffic such as the Second Word War or the Tudors, but it does translate: there’s a slow burn of foreign rights. I’ve written for personal interest but with an eye to the market: I’ve benefited from a post- 9/11 interest in Islam/Christianity issues. I’ve missed tricks, sometimes using up my material too fast, got titles wrong. I’ve created what post hoc looks like a trilogy of books about Mediterranean history but if I’d been more strategic I’d have done it differently. You live and hope to learn. I now think that skirting round heavily covered topics can be a mistake. There’s a reason for the squillions of books on Henry VIII and Hitler. People read them. I do study carefully (and sometimes enviously) what sells. It’s also apparent that you’re only as good as your last book: point of sale information, available to all publishers, mercilessly reveals your sales graph. On it can hang the size of your next advance. You always have to be on the top of your game.

I’ve learned that writing the books is not enough. Staggering from the desk, you then have to promote both the book and yourself: as in life generally, we are continuously reminded that we’re all our own brands. A good website is invaluable. Mine has brought me quite a number of interesting opportunities, but I don’t write enough articles or feed the Twitter beast (slowly working on that). I do literature festivals – stimulating to do and they put your name about – but their pure sales value seems dubious. Ideally all authors need to construct their own marketing plans – publishers only do so much – and we’re all invited to talk directly to our readers these days. Over time you get slightly better at judging opportunity costs after being ignored at bookshop signings or trying to animate tiny audiences.

But it’s not all orthopaedic risk at the desk or promotional boasting. We historians are lucky. They let us out to do research. We get to ramble around libraries and museums and go on trips. In my case, because the Mediterranean world is my main subject, I’ve been to fossick around Istanbul, Venice, Crete, Cyprus, Lisbon and various other places. And from time to time unexpected offers and opportunities pop into the inbox. I’ve been to study days with the US Navy in Washington and to NATO HQ in Belgium. I get to talk to varied audiences ranging from the Old Folks home down the road, to the Hay Festival to the US Army in Stuttgart and BBC radio. I’ve been to bob up and down in a boat at the site of the battle of Lepanto and to the Topkapi Palace outside opening hours for TV documentaries. I’ve given one day personalised tours of Istanbul and been on quite a few ships. I do one cruise a year with a small US company and I’ve spent nine days with my wife on a luxury vessel consisting entirely of privately owned apartments.

It’s the unexpected variety that makes these sidelines so engaging. A few weeks ago I was invited to talk to the cast of the Royal Shakespeare Company about the siege of Malta as background for their forthcoming production of Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta, for which I’ve also written programme notes. In a couple of weeks we’re going to see the results at the opening night in Stratford. Then it’s back to the desk, I guess, and what to write next. The house and garden could also do with attention.

It’s the unexpected variety that makes these sidelines so engaging. A few weeks ago I was invited to talk to the cast of the Royal Shakespeare Company about the siege of Malta as background for their forthcoming production of Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta, for which I’ve also written programme notes. In a couple of weeks we’re going to see the results at the opening night in Stratford. Then it’s back to the desk, I guess, and what to write next. The house and garden could also do with attention.My latest book, Conquerors: How Portugal seized the Indian Ocean and forged the First Global Empirewill be out in the UK on 17 September, in the US on 1 December

Published on March 11, 2015 07:51

March 4, 2015

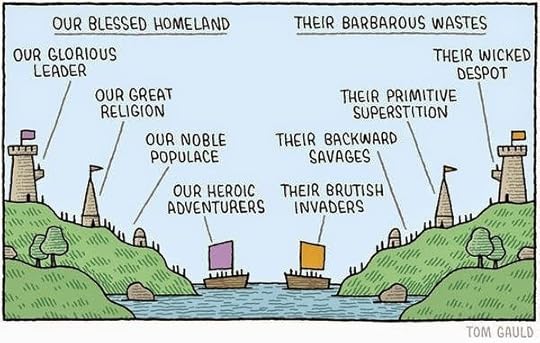

Pirates or Discoverers?

The book I've just written about the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean - is finished and in production. All my ponderings on historical perspective can be summed up in this one brilliant cartoon I saw in the Guardian at the weekend. On the left hand side Vasco da Gama and the Portuguese arrive on the coast of India. On the right, the perspective from the inhabitants of the Malabar Coast:

Published on March 04, 2015 14:41

February 28, 2015

The wealth of medieval England

This week we took advantage of an almost early spring day to explore the landscapes and little stone villages of the Cotswolds – bright sunshine, rooks cawing in the trees, small fast flowing rivers that form the headwaters of the Thames. This was a landscape made rich by wool, which was packed away across England on good straight routes left by the Romans, shipped to Flanders, Genoa, Venice and beyond. Merchants in Cairo wore Cotswold wool; so did the Janissaries, the crack troops of the Ottoman Empire. The grazing hills of the Cotswolds produced this wealth, and the villages and churches, built out of oolitic limestone, ranging in colour from pale grey to warm honey, contain a unique heritage of medieval architecture and art.

The church of East Leach Martin

The church of East Leach Martin

Published on February 28, 2015 03:11

February 17, 2015

'Take only what you can carry'

Thinking about refugees - and not a day goes by but the displacement of people gets worse and the tales more traumatic - I've just written a post for the interesting Museum of Marco Polo blog on the expulsion of the Greeks from the Ottoman Empire, particularly from the Black Sea region, and the massive population exchanges of 1923.

Visit the Marco Polo Museum site to read here.

Visit the Marco Polo Museum site to read here.

Published on February 17, 2015 02:05

February 3, 2015

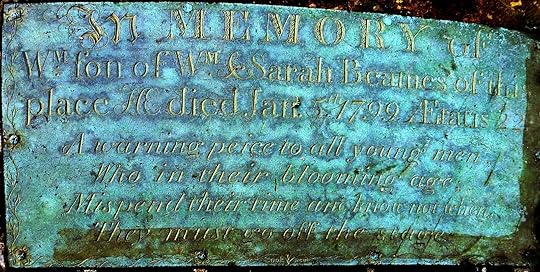

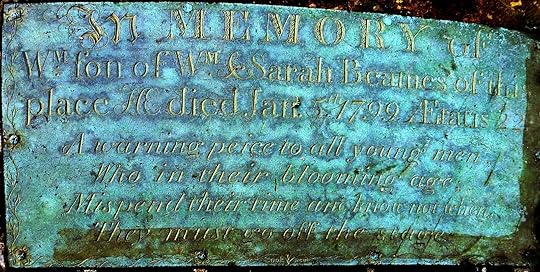

A warning to us all

Seen in a country churchyard recently - the memorial to the unfortunate William Beames, aged 22.

' A warning peice to all young men

Who in their blooming age

Mispend their time and know not when

They must go off the stage.'

I wonder what he could possibly have got up to in rural Gloucestershire in the late eighteenth century. I'm interested in the 'ei' spelling in 'peice' - it seems to have been quite common at the time.

' A warning peice to all young men

Who in their blooming age

Mispend their time and know not when

They must go off the stage.'

I wonder what he could possibly have got up to in rural Gloucestershire in the late eighteenth century. I'm interested in the 'ei' spelling in 'peice' - it seems to have been quite common at the time.

Published on February 03, 2015 09:21

Roger Crowley's Blog

- Roger Crowley's profile

- 820 followers

Roger Crowley isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.