Roger Crowley's Blog, page 7

July 17, 2013

Voices from Cairo

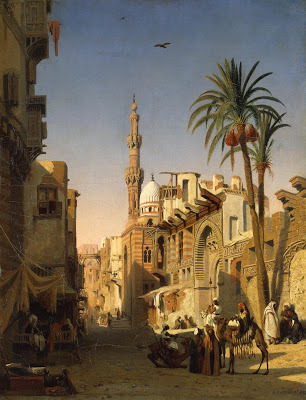

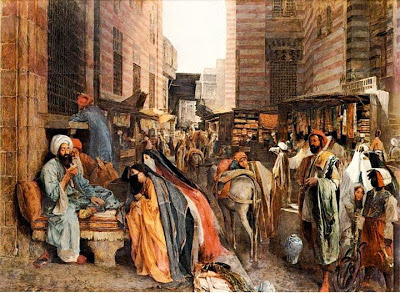

As Cairo becomes a turbulent battleground for the soul of modern Egypt I have found myself reading about its equally turbulent, exotic and frankly weird past.

I’ve been trying to skip read a chronicle covering the years roughly 1500- 1515 to discover how the sultan in Cairoreacted to the aggressive arrival of the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean. The trouble is that the detailed accounts of daily life in the city are so fascinating that I keep getting distracted. It’s an extraordinary Arabian Nights world – violent, fantastical, prone to bouts of superstition and magic, obsessed with rituals, exotic pageantry and terrible deaths. It charts the dying years of the Mamluk dynasty who ruled much of the Middle East – Egypt, Syria, the Arabian Peninsula– for some two hundred and fifty years – a dynasty on the edge of collapse, like the last years of Tsarist Russian, before extinction at the hands of the Ottomans who marched in and killed the last sultan in 1517. It’s living on borrowed time – but vividly.

The writer, Ibn Iyas, captures everything. There are firework displays and processions to mark the great days of the Muslim year; the construction of scented palaces, adorned with fruit trees and aromatic plants, streams of running water and shady pavilions; the polo season is declared open in the hippodrome, a horse falls during the match, the state of sultan’s health is a subject of public interest (colic, diarrhoea). The seasons are marked by his change of costume from wool to white cotton. The rise and fall of ‘the blessed Nile’, on which everything depends, is obsessively measured at the ‘Nileometer’. Plague cuts a swathe through the city; an outbreak of bird flu kills all the chickens; earth tremors shake the minarets. Three people are trampled to death during a free handout of food to the unemployed. Law and order is, to put it mildly, something of an issue: a man kills his wife, puts her body in a barrel of tar and sets fire to it; robbers ransack a market – they are caught and torn in two; a revolt by the Bedouin is put down, a grand procession includes 800 heads fixed to spears; the sheik Ahmad ibn Muhamma is paraded on a camel then hung from the city gates…

It’s a phantasmagoria of incredible vividness…two camels carrying flax brush the lantern hanging from a stall and catch fire. The terrified animals stampede with their flaming cargo and trample people underfoot, crashing through the markets, spreading death and destruction. A report from Gaza tells of an enormous sea creature washed ashore; the sultan writes to the governor asking him ‘to send this fish to Cairo, if it’s feasible.’ A dervish is hung. A Turk escapes in a borrowed uniform. Terrible tortures are inflicted on Badr al-din ibn Muzhir. The sultan’s performance at polo is judged mediocre. The Portuguese interrupt Muslim shipping and cause a shortage of turban material. A man has a dream that a huge treasure is buried under the pillars supporting a mosque, but he is unable to say exactly which one; the sultan orders the demolition of all the pillars; a huge crowd gathers to watch but the sultan then changes his mind - the dreamer is thought unreliable. A one year old elephant from Zanzibaris processed through the streets – the whole city turns out to watch, no elephant has been seen in the city for forty years. There are bloody quarrels among the black slaves. At night an eerie light is seen, shaped like the sail of a ship – there is no explanation. It’s a world of colour, passion, magic and dreams!

And ‘in the first days of this month, one heard of the death of Aziza bint Sathi, one of the most famous singers in Egypt, the marvel of the age. Her diction and her voice were admirable and were worthy of the poetic language (of the words). No other singer afterwards could be compared with her. No other chanteuse enjoyed such an appreciation among the nobles and grand functionaries of the state. This woman, whose reputation has been immense throughout Egypt, was over eighty when she died.’

I wonder what she sounded like. I’d love to have heard her sing.

I’ve been trying to skip read a chronicle covering the years roughly 1500- 1515 to discover how the sultan in Cairoreacted to the aggressive arrival of the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean. The trouble is that the detailed accounts of daily life in the city are so fascinating that I keep getting distracted. It’s an extraordinary Arabian Nights world – violent, fantastical, prone to bouts of superstition and magic, obsessed with rituals, exotic pageantry and terrible deaths. It charts the dying years of the Mamluk dynasty who ruled much of the Middle East – Egypt, Syria, the Arabian Peninsula– for some two hundred and fifty years – a dynasty on the edge of collapse, like the last years of Tsarist Russian, before extinction at the hands of the Ottomans who marched in and killed the last sultan in 1517. It’s living on borrowed time – but vividly.

The writer, Ibn Iyas, captures everything. There are firework displays and processions to mark the great days of the Muslim year; the construction of scented palaces, adorned with fruit trees and aromatic plants, streams of running water and shady pavilions; the polo season is declared open in the hippodrome, a horse falls during the match, the state of sultan’s health is a subject of public interest (colic, diarrhoea). The seasons are marked by his change of costume from wool to white cotton. The rise and fall of ‘the blessed Nile’, on which everything depends, is obsessively measured at the ‘Nileometer’. Plague cuts a swathe through the city; an outbreak of bird flu kills all the chickens; earth tremors shake the minarets. Three people are trampled to death during a free handout of food to the unemployed. Law and order is, to put it mildly, something of an issue: a man kills his wife, puts her body in a barrel of tar and sets fire to it; robbers ransack a market – they are caught and torn in two; a revolt by the Bedouin is put down, a grand procession includes 800 heads fixed to spears; the sheik Ahmad ibn Muhamma is paraded on a camel then hung from the city gates…

It’s a phantasmagoria of incredible vividness…two camels carrying flax brush the lantern hanging from a stall and catch fire. The terrified animals stampede with their flaming cargo and trample people underfoot, crashing through the markets, spreading death and destruction. A report from Gaza tells of an enormous sea creature washed ashore; the sultan writes to the governor asking him ‘to send this fish to Cairo, if it’s feasible.’ A dervish is hung. A Turk escapes in a borrowed uniform. Terrible tortures are inflicted on Badr al-din ibn Muzhir. The sultan’s performance at polo is judged mediocre. The Portuguese interrupt Muslim shipping and cause a shortage of turban material. A man has a dream that a huge treasure is buried under the pillars supporting a mosque, but he is unable to say exactly which one; the sultan orders the demolition of all the pillars; a huge crowd gathers to watch but the sultan then changes his mind - the dreamer is thought unreliable. A one year old elephant from Zanzibaris processed through the streets – the whole city turns out to watch, no elephant has been seen in the city for forty years. There are bloody quarrels among the black slaves. At night an eerie light is seen, shaped like the sail of a ship – there is no explanation. It’s a world of colour, passion, magic and dreams!

And ‘in the first days of this month, one heard of the death of Aziza bint Sathi, one of the most famous singers in Egypt, the marvel of the age. Her diction and her voice were admirable and were worthy of the poetic language (of the words). No other singer afterwards could be compared with her. No other chanteuse enjoyed such an appreciation among the nobles and grand functionaries of the state. This woman, whose reputation has been immense throughout Egypt, was over eighty when she died.’

I wonder what she sounded like. I’d love to have heard her sing.

Published on July 17, 2013 06:00

June 29, 2013

Midsummer England

It’s the Glastonbury Festival this weekend but we went to a more cultural version of this midsummer celebration of tribal identity – the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of As You Like It in Stratford-on-Avon. Every thing the RSC do is amazing, and this was quite quite wonderful. Drawing on Shakespeare’s deep affinity with the folk customs and seasonal rhythms of the forest of Arden – the area around Stratford – the RSC dreamed up a modernised, Glastonbury-like, recreation of the earth celebrations of pagan England – a world of horned men, primal dancing, cross-dressing and fertility rites, exquisite music by Laura Marling and the kind of audience connection that only fantastically well-done live theatre can provide. An energetic celebration of the spirit of midsummer.

Coming out into the dark, swans float asleep on the River Avon; the trees of Warwickshire are in full sail, like ships on an inland sea; a deer crosses the road as we drive home; the year is at its height. Here's the trailer and some of Laura Marling's music for the play.

Published on June 29, 2013 02:51

June 20, 2013

Monty's hat

British icons from the Second World War: Churchill with his cigar and his Victory sign, General Montgomery in his black beret. I read the story of the beret yesterday with the death of Jim Fraser, aged 92, a humble tank driver in the North Africa campaign. Jim drove the tank from which Monty liked to address the troops. Monty also liked to wear a broad-brimmed Australian hat. The problem was that the desert wind kept whipping the hat off; the tank had to stop so that the hat could be retrieved.

This finally proved too much for Jim. He recalled in his memoirs: "I shoved my beret up into the turret, muttering: 'Tell him to wear this and we'll get there quicker.' The aide-de-camp handed the beret to Monty who tried it on and liked it." Immortality for the ordinary man!

Jim (in the goggles) with Monty in Jim's (first?) hat

Jim (in the goggles) with Monty in Jim's (first?) hat

Jim, wounded three times, a winner of the Military Cross, and a proud beret wearer to the end.

This finally proved too much for Jim. He recalled in his memoirs: "I shoved my beret up into the turret, muttering: 'Tell him to wear this and we'll get there quicker.' The aide-de-camp handed the beret to Monty who tried it on and liked it." Immortality for the ordinary man!

Jim (in the goggles) with Monty in Jim's (first?) hat

Jim (in the goggles) with Monty in Jim's (first?) hat

Jim, wounded three times, a winner of the Military Cross, and a proud beret wearer to the end.

Published on June 20, 2013 03:48

June 8, 2013

Beneath the Cretan earth

I still find myself pondering, almost haunted by, a story I was told a few years ago on a trip to Crete. I was looking for signs of Crete’s Venetian past and had come to a village that had been overlaid by Venetian houses sometime in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. But in Crete the layers lie one on top of the other, the Ottoman on the Venetian, the Venetian on the Byzantine, far back through the Romans to the Dorians and the Minoans, sea people who came to the Great Island in boats. This village was typical – it was a site of great antiquity, of considerable interest to archaeologists

We stayed in a small hotel there, run by a local family; also staying were an English couple who were regular visitors and good friends of the owners. They related to us a curious tale, told to them by the owners.

Some while back, an English archaeologist and his family had come to live in the village; their children were the same age as those of the hotel owners, and they became very close friends. The families spent a lot of time together; the Cretan children learned English from the visitors who would come most evenings to the hotel and pass time with them. The archaeologist was also deeply occupied studying the land and drawing plans of the ancient field systems.

One day the archaeologist was walking in some fields that belonged to the Cretan family, with, I think, all the children – certainly the Cretan children were with him. He spotted an interesting hole in the ground but nothing much was said about it.

That evening, I think or maybe the next, the details aren’t exactly clear, the English family didn’t appear at the hotel, which was extremely unusual. In due course the Cretans went round to the archaeologist’s house to see what had happened. They found no one there. Their land drover had gone; the house had been emptied of possessions. The English family had vanished into thin air.

The children thought back to the hole in the field which had caught the archaeologist’s attention. They returned to look. It was obvious that it had been dug open. There was a pit inside which was empty. They never saw or heard from their good English friends again. Something had been found there that caused the archaeologist to scoop up his family and vanish. The Cretan hoteliers had since become very suspicious of visiting archaeologists and over-friendly foreigners… It almost has the quality of a ghost story.

We stayed in a small hotel there, run by a local family; also staying were an English couple who were regular visitors and good friends of the owners. They related to us a curious tale, told to them by the owners.

Some while back, an English archaeologist and his family had come to live in the village; their children were the same age as those of the hotel owners, and they became very close friends. The families spent a lot of time together; the Cretan children learned English from the visitors who would come most evenings to the hotel and pass time with them. The archaeologist was also deeply occupied studying the land and drawing plans of the ancient field systems.

One day the archaeologist was walking in some fields that belonged to the Cretan family, with, I think, all the children – certainly the Cretan children were with him. He spotted an interesting hole in the ground but nothing much was said about it.

That evening, I think or maybe the next, the details aren’t exactly clear, the English family didn’t appear at the hotel, which was extremely unusual. In due course the Cretans went round to the archaeologist’s house to see what had happened. They found no one there. Their land drover had gone; the house had been emptied of possessions. The English family had vanished into thin air.

The children thought back to the hole in the field which had caught the archaeologist’s attention. They returned to look. It was obvious that it had been dug open. There was a pit inside which was empty. They never saw or heard from their good English friends again. Something had been found there that caused the archaeologist to scoop up his family and vanish. The Cretan hoteliers had since become very suspicious of visiting archaeologists and over-friendly foreigners… It almost has the quality of a ghost story.

Published on June 08, 2013 14:47

May 29, 2013

Constantinople fell today - and new covers!

29 May 1453 - the fall of Constantinople. In Istanbul processions and re-enactments. For the Greeks the memory of a painful loss - not that they need anything else painful to think about just now.

My UK publisher, Faber, have just given me wonderful new covers for Constantinople and Empires of the Sea. Just to warn you - one or two people have seen these on Amazon and think, particularly with Constantinople, that they are new books...unfortunately I don't write that fast, but I do almost have a brand! Constantinople carries the double-headed eagle of the Palaiologi - the Byzantine dynasty whose last emperor, Constantine XI, died fighting bravely on the city walls this afternoon, 560 years ago. It seems long ago and yet fresh in the memory of the Greek and Turkish peoples.

My UK publisher, Faber, have just given me wonderful new covers for Constantinople and Empires of the Sea. Just to warn you - one or two people have seen these on Amazon and think, particularly with Constantinople, that they are new books...unfortunately I don't write that fast, but I do almost have a brand! Constantinople carries the double-headed eagle of the Palaiologi - the Byzantine dynasty whose last emperor, Constantine XI, died fighting bravely on the city walls this afternoon, 560 years ago. It seems long ago and yet fresh in the memory of the Greek and Turkish peoples.

Published on May 29, 2013 05:39

May 27, 2013

The Portuguese empire

Further on the Portuguese, this wonderful, melancholic Youtube video, accompanied by an aching soundtrack from Madredeus, a contemporary music group, highlights the reach of their empire - from Macau to Morocco, the straits of Hormuz to the west coast of Africa, Goa to Brazil. Both a snapshot of the extent and durability of the Portuguese achievement, linked to a palpable sense of nostalgia for vanished glory that, I guess, haunts all empires that have had their day - the British Empire not excluded.

Published on May 27, 2013 14:34

May 19, 2013

The Pope's elephant

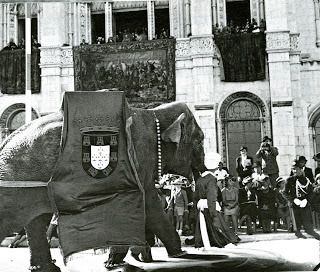

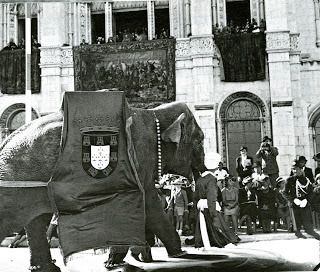

I’ve been in Portugal for the last couple of weeks doing background research into the Portuguese exploration of the world. Whilst there I picked up a magazine with an old photograph of an elephant in a procession, which reminded me of the elephant the Portuguese once sent to the pope.

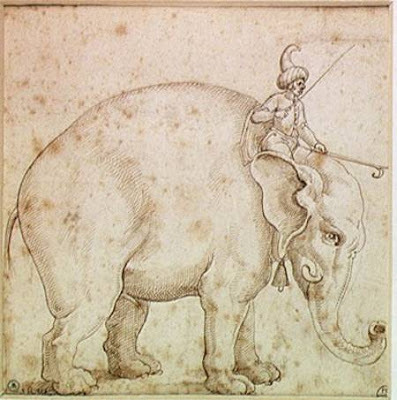

In 1514, King Manuel II of Portugal sent Pope Leo X an Indian elephant. It’s interesting to speculate on the process of shipping an elephant on a sailing ship from India in the sixteenth century. I guess it would have been winched on board, and somehow restrained in a hold for the long sea journey – 12, 000 miles and six months – and fed on what? As the elephant was accompanied by its Indian mahout it must have been in expert hands. Moving animals about on ships has always been something of a problem – the crusaders suspended their warhorses in slings so that they could roll with the movement of the ship, but elephants are a different proposition. (There’s an account of a celebrity elephant in Europe in the late fifteenth century being carried to England in a ship and being thrown overboard when it became a liability in a storm.)

The Portuguese elephant was especially dramatic. It was white in colour – and Manuel, who knew a thing or two about propaganda, contrived a wildly exotic advertisement for his country's discoveries in the New World. He despatched the elephant to Rome under the command of his ambassador, Tristão da Cunha, the navigator and explorer. In March 1514 a cavalcade of 140 people, including some Indians, and an assortment of wild animals – leopards, parrots and a panther – entered Rome watched by a gawping crowd who had never seen the like of it before. The elephant carried a silver castle on its back with rich presents for the pope, who christened it Hanno, after Hannibal’s elephants in Italy.

At the papal audience, Hanno bowed three times and amused and alarmed the cardinals of the Holy Church by spraying the contents of a bucket of water over them. He was an immediate animal star – painted by artists, memorialized by poets, the subject of a now-lost fresco and a scandalous satirical pamphlet ‘The Last Will and Testament of the Elephant Hanno’. He was housed in a specially constructed building, took part in processions and was greatly loved by the pope. Unfortunately Hanno’s diet was probably not up to scratch and he died two years after his arrival, aged seven, having been dosed with a laxative laced with gold. The grieving Leo X was at his side. He was buried with honour.

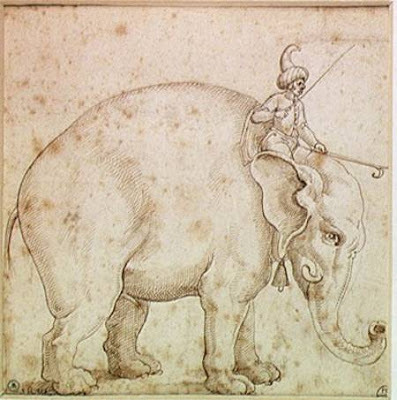

Hanno and his mahout

Hanno and his mahout

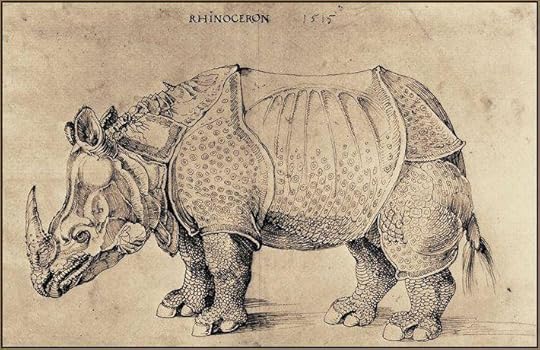

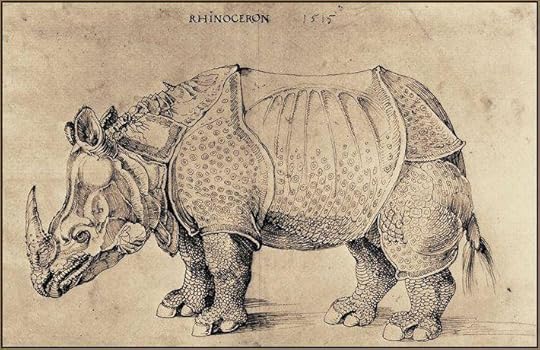

Even less fortunate was Manuel’s follow-up gift – a rhinoceros – dispatched from Lisbon in a green velvet collar. The ship was wrecked off the coast of Genoa in 1515. The animal drowned and was washed up on the seashore. Its hide was recovered, returned to Lisbon and stuffed. Albrecht Dürer saw a letter describing the stuffed creature, and possibly a sketch. He produced his famous print without ever having seen a rhino – not a bad attempt under the circumstances.

The old photograph I saw in the Portuguese magazine dates from a celebration of the Portuguese world in 1940, in which Hanno’s entry into Rome was re-enacted in Lisbon.

In 1514, King Manuel II of Portugal sent Pope Leo X an Indian elephant. It’s interesting to speculate on the process of shipping an elephant on a sailing ship from India in the sixteenth century. I guess it would have been winched on board, and somehow restrained in a hold for the long sea journey – 12, 000 miles and six months – and fed on what? As the elephant was accompanied by its Indian mahout it must have been in expert hands. Moving animals about on ships has always been something of a problem – the crusaders suspended their warhorses in slings so that they could roll with the movement of the ship, but elephants are a different proposition. (There’s an account of a celebrity elephant in Europe in the late fifteenth century being carried to England in a ship and being thrown overboard when it became a liability in a storm.)

The Portuguese elephant was especially dramatic. It was white in colour – and Manuel, who knew a thing or two about propaganda, contrived a wildly exotic advertisement for his country's discoveries in the New World. He despatched the elephant to Rome under the command of his ambassador, Tristão da Cunha, the navigator and explorer. In March 1514 a cavalcade of 140 people, including some Indians, and an assortment of wild animals – leopards, parrots and a panther – entered Rome watched by a gawping crowd who had never seen the like of it before. The elephant carried a silver castle on its back with rich presents for the pope, who christened it Hanno, after Hannibal’s elephants in Italy.

At the papal audience, Hanno bowed three times and amused and alarmed the cardinals of the Holy Church by spraying the contents of a bucket of water over them. He was an immediate animal star – painted by artists, memorialized by poets, the subject of a now-lost fresco and a scandalous satirical pamphlet ‘The Last Will and Testament of the Elephant Hanno’. He was housed in a specially constructed building, took part in processions and was greatly loved by the pope. Unfortunately Hanno’s diet was probably not up to scratch and he died two years after his arrival, aged seven, having been dosed with a laxative laced with gold. The grieving Leo X was at his side. He was buried with honour.

Hanno and his mahout

Hanno and his mahoutEven less fortunate was Manuel’s follow-up gift – a rhinoceros – dispatched from Lisbon in a green velvet collar. The ship was wrecked off the coast of Genoa in 1515. The animal drowned and was washed up on the seashore. Its hide was recovered, returned to Lisbon and stuffed. Albrecht Dürer saw a letter describing the stuffed creature, and possibly a sketch. He produced his famous print without ever having seen a rhino – not a bad attempt under the circumstances.

The old photograph I saw in the Portuguese magazine dates from a celebration of the Portuguese world in 1940, in which Hanno’s entry into Rome was re-enacted in Lisbon.

Published on May 19, 2013 23:39

April 21, 2013

The Jump

Belgian resistant fighters manage to halt the train, long enough to unlock a door. Then it starts again. Your mother pushes you towards the opening, impelled by hope – that you might survive. She hands you a hundred franc note. You tuck it into your sock. She lowers you onto the foot rail below the door. You prepare to jump. You are eleven years old.

"I saw the trees go by and the train was getting faster. The air was crisp and cool and the noise was deafening. I remember feeling surprised that it could go so fast with 35 cars being towed. But then at a certain moment, I felt the train slow down. I told my mother: 'Now I can jump.' She let me go and I jumped off. First I stood there frozen, I could see the train moving slowly forward - it was this large black mass in the dark, spewing steam."

This week, to coincide with the seventieth anniversary, the BBC website retold the story of the survival of Simon Gronowski and the daring hijack of a train bound for Auschwitz. The three resistant fighters pulled off this feat armed with one pistol, a lantern, a sheet of red paper and four pairs of pliers. 118 Jews managed to escape alive. The date was April 19 1943 – the day the Warsaw Uprising started. The last of the resistance fighters, Robert Maistriau, died in 2008. Here is his account of that day. Simon Gronowski, now a jazz playing grandfather, recently returned to the scene of his jump, the place where he spoke those last words to his mother, ‘the first of my heroes’.

"I saw the trees go by and the train was getting faster. The air was crisp and cool and the noise was deafening. I remember feeling surprised that it could go so fast with 35 cars being towed. But then at a certain moment, I felt the train slow down. I told my mother: 'Now I can jump.' She let me go and I jumped off. First I stood there frozen, I could see the train moving slowly forward - it was this large black mass in the dark, spewing steam."

This week, to coincide with the seventieth anniversary, the BBC website retold the story of the survival of Simon Gronowski and the daring hijack of a train bound for Auschwitz. The three resistant fighters pulled off this feat armed with one pistol, a lantern, a sheet of red paper and four pairs of pliers. 118 Jews managed to escape alive. The date was April 19 1943 – the day the Warsaw Uprising started. The last of the resistance fighters, Robert Maistriau, died in 2008. Here is his account of that day. Simon Gronowski, now a jazz playing grandfather, recently returned to the scene of his jump, the place where he spoke those last words to his mother, ‘the first of my heroes’.

Published on April 21, 2013 02:26

April 14, 2013

Voices from the Black Sea

'Greetings, passer by!'

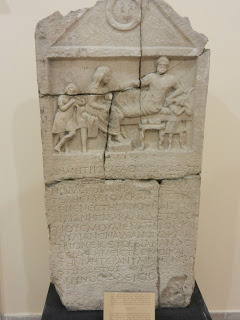

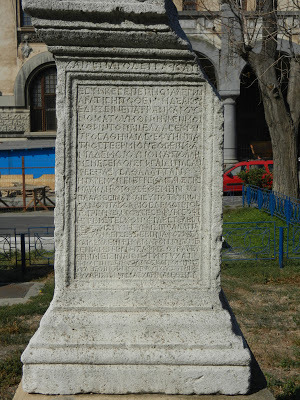

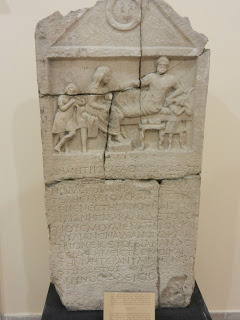

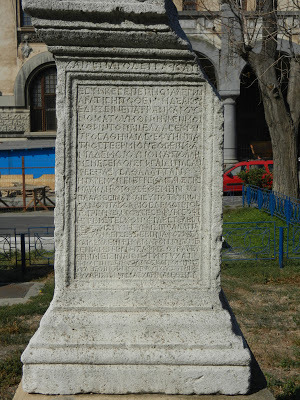

Looking over some material I collected on a trip round the Black Sea a couple of years ago, I was again struck by the inscriptions on Greek grave stones from the early centuries AD. There's a tradition of the dead speaking directly on these memorials, being ventriloquised by their surviving relatives, so that we feel that we're hearing the people of the past talking to us personally over a gap of two thousand years. There's something incredibly moving in these inscriptions. They beg the passer by to stop and remember; they tug at our sleeves and demand our attention; they bewail their fates or celebrate their time on earth and give us accounts of their lives.

'Hades came towards me so fast' laments Hegesandros, 'the famous son of Eros and Apphia', in Amasra on the Turkish coast. 'Listen, stranger' says Ephipania from ancient Tomis in modern Rumania, 'my place of origin was Greece....I saw many lands and sailed over the sea because my father, as well as my husband, were ship owners, whom after death I laid in the grave with clean hands. My life was really happy before! I was born among muses and shared the goods of wisdom. As a woman, I gave much help to women, to abandoned wives, being ruled by pious sentiments, and I helped people confined to their beds by suffering, because I realised that mortals' fates are not according to their piousness. Hermogenes full of gratitude devoted this monument as a remembrance'. A life well lived.

And Cecilia, also from Tomis, gives us her life story.

'If you want to know, passer by, who and whose I am, listen: when I was thirteen a young man loved me, worthy of us: then I married him and bore three children. A son, first and then two daughters, the very image of my face. Finally I bore a fourth one, but I should not have had any more, because the child died first and I did too a little time later. I left the light of the sun when I was thirty. Perinthos is my husband and my home. My son's name is Priscus, my daughter's Hieronis. As regards Theodora she was a child in the house when I died. My husband, Perinthos, lives and mourns me with a faint voice. My good father also weeps because I retreated here. I also have here in the grave my mother Flavia Theodora. My husband's father, Caecilius Priscus, also lies here. A greeting to you too whoever you are, you who pass by our graves!'

I feel somehow oddly cheered by these friendly greetings from the people of the past.

Looking over some material I collected on a trip round the Black Sea a couple of years ago, I was again struck by the inscriptions on Greek grave stones from the early centuries AD. There's a tradition of the dead speaking directly on these memorials, being ventriloquised by their surviving relatives, so that we feel that we're hearing the people of the past talking to us personally over a gap of two thousand years. There's something incredibly moving in these inscriptions. They beg the passer by to stop and remember; they tug at our sleeves and demand our attention; they bewail their fates or celebrate their time on earth and give us accounts of their lives.

'Hades came towards me so fast' laments Hegesandros, 'the famous son of Eros and Apphia', in Amasra on the Turkish coast. 'Listen, stranger' says Ephipania from ancient Tomis in modern Rumania, 'my place of origin was Greece....I saw many lands and sailed over the sea because my father, as well as my husband, were ship owners, whom after death I laid in the grave with clean hands. My life was really happy before! I was born among muses and shared the goods of wisdom. As a woman, I gave much help to women, to abandoned wives, being ruled by pious sentiments, and I helped people confined to their beds by suffering, because I realised that mortals' fates are not according to their piousness. Hermogenes full of gratitude devoted this monument as a remembrance'. A life well lived.

And Cecilia, also from Tomis, gives us her life story.

'If you want to know, passer by, who and whose I am, listen: when I was thirteen a young man loved me, worthy of us: then I married him and bore three children. A son, first and then two daughters, the very image of my face. Finally I bore a fourth one, but I should not have had any more, because the child died first and I did too a little time later. I left the light of the sun when I was thirty. Perinthos is my husband and my home. My son's name is Priscus, my daughter's Hieronis. As regards Theodora she was a child in the house when I died. My husband, Perinthos, lives and mourns me with a faint voice. My good father also weeps because I retreated here. I also have here in the grave my mother Flavia Theodora. My husband's father, Caecilius Priscus, also lies here. A greeting to you too whoever you are, you who pass by our graves!'

I feel somehow oddly cheered by these friendly greetings from the people of the past.

Published on April 14, 2013 09:16

April 7, 2013

The Fairford demons

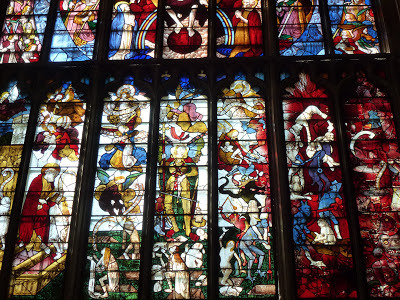

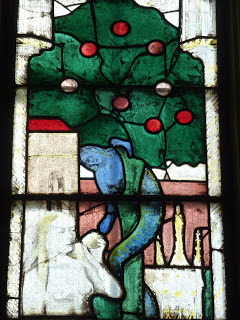

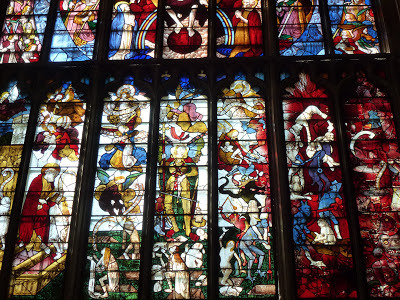

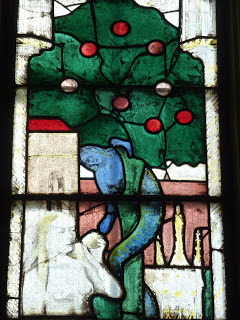

On Easter day we went to Fairford – an old Cotswold market town through which the river Coln quietly flows – to see one of England’s great surviving works of medieval art: the stained glass in its church. Such glass is a rarity – so much was destroyed in the Reformation: the sculptures pulverized, the wall paintings plastered over, the windows smashed. Whatever the corruption, the cynicism, the extortion of the Church, it provided medieval people with colour, pageantry, festivals, entertainment, visions of heaven.

Somehow the glass at Fairford survived this purge almost intact. On a right sunny Easter afternoon, brilliant blues and greens, purples and scarlets glow with an astonishing depth of colour.

For the illiterate shepherd or peasant, accustomed to the dull colours of earth, stone and bleached grass, it must have been the most luminous vision they’d ever see. It’s not only a visual bible story but a wondrous inventory of late medieval life. Amongst the lives of saints and old testament prophets, there are men in armour, distant turreted castles, brilliantly coloured gown and hats, animals, fruits, plants and trees.

Most extraordinary of all is the west window - the last judgement. The upper half has been replaced by dull Victorian glass, but below, the scene of the weighing of souls - those destined for heaven, those for hell - is quite extraordinary. Whilst the virtuous are whirled up towards the light by piping angels, the sinful are being carried off to hellfire by terrible creatures - green monsters with scaly tales, spotted demons with horns and whips, purple ones hauling their pallid victims away in chains. Their mouths are open in silent horror as they slide down into the flames. It is too late to repent.

And at the bottom Satan waits, multi-eyed, lustful, pitiless, his gobbling stomach ready to devour the screaming souls being sucked into his blast-furnace so fiercely red you can almost feel the scorching heat coming off the sheets of glass. It could be a scene from Hieronymus Bosch - and you wonder if the men who made the glass, who were Flemish, could have shared his imaginative world. It must have scared the living daylights out of the humble folk of Fairford five hundred years ago.

Somehow the glass at Fairford survived this purge almost intact. On a right sunny Easter afternoon, brilliant blues and greens, purples and scarlets glow with an astonishing depth of colour.

For the illiterate shepherd or peasant, accustomed to the dull colours of earth, stone and bleached grass, it must have been the most luminous vision they’d ever see. It’s not only a visual bible story but a wondrous inventory of late medieval life. Amongst the lives of saints and old testament prophets, there are men in armour, distant turreted castles, brilliantly coloured gown and hats, animals, fruits, plants and trees.

Most extraordinary of all is the west window - the last judgement. The upper half has been replaced by dull Victorian glass, but below, the scene of the weighing of souls - those destined for heaven, those for hell - is quite extraordinary. Whilst the virtuous are whirled up towards the light by piping angels, the sinful are being carried off to hellfire by terrible creatures - green monsters with scaly tales, spotted demons with horns and whips, purple ones hauling their pallid victims away in chains. Their mouths are open in silent horror as they slide down into the flames. It is too late to repent.

And at the bottom Satan waits, multi-eyed, lustful, pitiless, his gobbling stomach ready to devour the screaming souls being sucked into his blast-furnace so fiercely red you can almost feel the scorching heat coming off the sheets of glass. It could be a scene from Hieronymus Bosch - and you wonder if the men who made the glass, who were Flemish, could have shared his imaginative world. It must have scared the living daylights out of the humble folk of Fairford five hundred years ago.

Published on April 07, 2013 10:01

Roger Crowley's Blog

- Roger Crowley's profile

- 820 followers

Roger Crowley isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.