Roger Crowley's Blog, page 8

March 30, 2013

‘A new life! Freedom! Something to write about!’

Two young men setting out on foot, nearly 80 years ago, on almost parallel journeys that would change their lives:

Winter 1933‘I was signalling frantically back as the hawsers were cast loose and the gangplank shipped. Then they were gone. The anchor-chain clattered through the ports and the vessel turned into the current with a wail of her siren. How strange it seemed, as I took shelter in the little saloon to be setting off from the heart of London.’

Summer 1935‘The stooping figure of my mother, waist-deep in the grass and caught there like a piece of sheep's wool, was the last I saw of my country home as I left it to discover the world. She stood old and bent at the top of the bank, silently watching me go, one gnarled red hand raised in farewell and blessing, not questioning why I went. At the bend of the road I looked back again and saw the gold light die behind her; then I turned the corner, passed the village school, and closed that part of my life for ever.’

Recently I’ve been reading the biographies of the two men who wrote these passages. The first was by

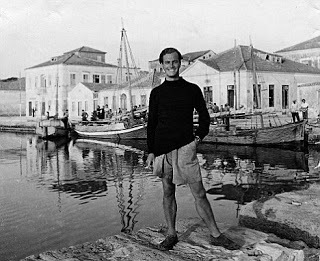

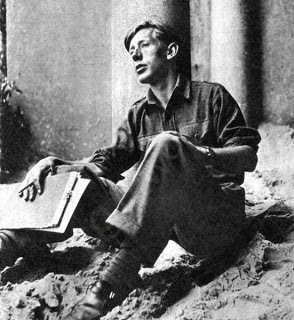

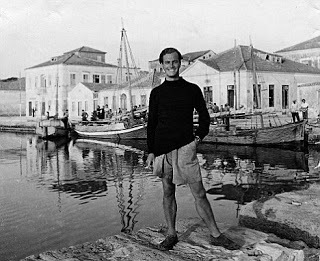

Patrick Leigh-Fermor Patrick Leigh-Fermor, public school educated rebel, restless, adventurous and reckless, with the clipped accent of a 1930s BBC news reader. The second was Laurie Lee, a boy of much humbler background from rural Gloucestershire – he described himself as a peasant, though he was slightly more than that – with the soft burr of his native valley in his speech. Young men from different worlds but fired by the same romantic vision: to escape the cramping, class-confined dullness of interwar England and see the world. Both went, in Leigh-Fermor’s words, ‘to set out across Europe like a tramp..A new life! Freedom! Something to write about!’

Patrick Leigh-Fermor Patrick Leigh-Fermor, public school educated rebel, restless, adventurous and reckless, with the clipped accent of a 1930s BBC news reader. The second was Laurie Lee, a boy of much humbler background from rural Gloucestershire – he described himself as a peasant, though he was slightly more than that – with the soft burr of his native valley in his speech. Young men from different worlds but fired by the same romantic vision: to escape the cramping, class-confined dullness of interwar England and see the world. Both went, in Leigh-Fermor’s words, ‘to set out across Europe like a tramp..A new life! Freedom! Something to write about!’

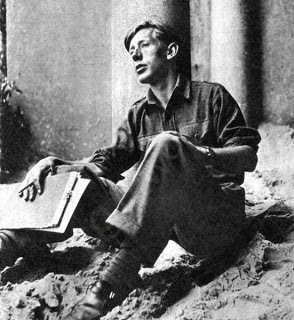

Laurie Lee

Laurie Lee

Both travelled on foot on what would prove to be life-changing experiences; both would write brilliantly about what they’d seen. Leigh-Fermor walked the length of Europe – from the tip of Holland to Constantinople. The journey took him a year; but he didn’t see the white cliffs of Dover again for three, ‘a whole life time later it seemed then – and, for better or for worse, utterly changed by my travels.’ Along the way he learned multiple languages, stayed with the aristocracy of central Europe, fell in love and lived the days with a thrilling intensity.

Laurie caught a boat to Spain and walked across the heat-stunned landscapes of the central plateau, sleeping out under olive trees, welcomed in to share the food of its peasants who were enchanted by the fair-haired stranger. His passport was his violin. In this Homeric world, he captivated the souls of the people with his music. He made them laugh, dance, cry and temporarily forget their suffering: ‘They lived hard and semi-starved lives, but if I unrolled my blanket…and they saw my violin their faces would soften and crease, there’d be a cry of Musica! Musica!...I’d play paso dobles and even the old ladies would dance a few creaky steps around the patio.’

Laurie caught a boat to Spain and walked across the heat-stunned landscapes of the central plateau, sleeping out under olive trees, welcomed in to share the food of its peasants who were enchanted by the fair-haired stranger. His passport was his violin. In this Homeric world, he captivated the souls of the people with his music. He made them laugh, dance, cry and temporarily forget their suffering: ‘They lived hard and semi-starved lives, but if I unrolled my blanket…and they saw my violin their faces would soften and crease, there’d be a cry of Musica! Musica!...I’d play paso dobles and even the old ladies would dance a few creaky steps around the patio.’

These were young men’s experiences – Leigh-Fermor was 18, Laurie Lee 21 –journeys of adventure, escape, romance. They both looked at new worlds for the first time, entranced, and noticed everything. They kept note books – and years later they would produce extraordinary artfully-shaped classics of travel writing: Patrick Leigh-Fermor’s A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water, Laurie Lee’s As I Walked out One Summer Morning and A Rose for Winter.

Both men had complex, adventurous and – in ways – difficult lives after these first journeys. Laurie Lee returned to Spain to fight in the Civil War; Patrick Leigh-Fermor became immensely famous for his years in the Cretan mountains in the Second World War and the kidnapping of the German general there. They both drank too much, had complicated love lives, wrote too little and perhaps squandered their talents. Laurie Lee is now best known for his childhood account of the village he grew up in – Cider with Rosie (in the US, Edge of Day), but you have the feeling that nothing ever equalled the intense experiences of those early travels. And in a world in which everything can now be seen from Google Earth it’s hard not to envy their journeys without maps.

I was once tempted to send Patrick Leigh-Fermor a copy of my book on the fall of Constantinople, as he knew the Greek world deeply and lived there for most of his life, but never did, and didn’t want to be a ‘fan’. Laurie Lee I never spoke to but knew by sight as he returned to Slad, the village of his childhood, and we live nearby. (My wife once helped him plant a commemorative tree by our village cricket pitch, which he owned: she almost had to stop the sadly decrepit old man falling into the hole dug for the planting. I once watched him shuffling off the train at the local station with a half-drunk bottle of whisky stuffed in his coat pocket.) Both men lie buried in Gloucestershire churchyards.

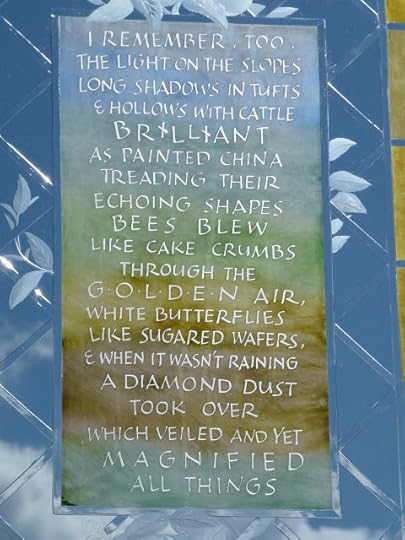

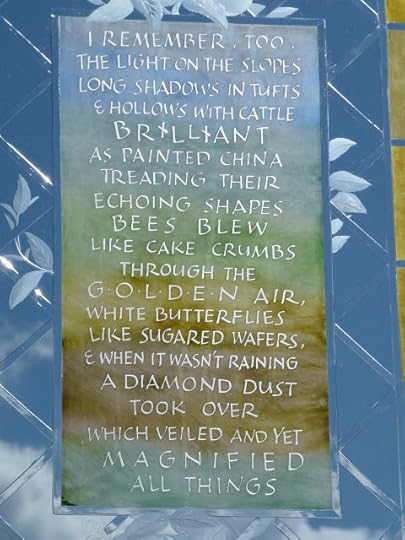

Today – on a blue, sunny, bone-dry, and unseasonably cold Spring morning – I went on a whim to pay my respects to Laurie in the Slad churchyard looking across the road down which he departed that summer day in 1935 to the valley and the hills beyond. Inside the church there are some quite lovely stained glass windows that depict his travels to Spain, his violin and his words.

Today – on a blue, sunny, bone-dry, and unseasonably cold Spring morning – I went on a whim to pay my respects to Laurie in the Slad churchyard looking across the road down which he departed that summer day in 1935 to the valley and the hills beyond. Inside the church there are some quite lovely stained glass windows that depict his travels to Spain, his violin and his words.

Winter 1933‘I was signalling frantically back as the hawsers were cast loose and the gangplank shipped. Then they were gone. The anchor-chain clattered through the ports and the vessel turned into the current with a wail of her siren. How strange it seemed, as I took shelter in the little saloon to be setting off from the heart of London.’

Summer 1935‘The stooping figure of my mother, waist-deep in the grass and caught there like a piece of sheep's wool, was the last I saw of my country home as I left it to discover the world. She stood old and bent at the top of the bank, silently watching me go, one gnarled red hand raised in farewell and blessing, not questioning why I went. At the bend of the road I looked back again and saw the gold light die behind her; then I turned the corner, passed the village school, and closed that part of my life for ever.’

Recently I’ve been reading the biographies of the two men who wrote these passages. The first was by

Patrick Leigh-Fermor Patrick Leigh-Fermor, public school educated rebel, restless, adventurous and reckless, with the clipped accent of a 1930s BBC news reader. The second was Laurie Lee, a boy of much humbler background from rural Gloucestershire – he described himself as a peasant, though he was slightly more than that – with the soft burr of his native valley in his speech. Young men from different worlds but fired by the same romantic vision: to escape the cramping, class-confined dullness of interwar England and see the world. Both went, in Leigh-Fermor’s words, ‘to set out across Europe like a tramp..A new life! Freedom! Something to write about!’

Patrick Leigh-Fermor Patrick Leigh-Fermor, public school educated rebel, restless, adventurous and reckless, with the clipped accent of a 1930s BBC news reader. The second was Laurie Lee, a boy of much humbler background from rural Gloucestershire – he described himself as a peasant, though he was slightly more than that – with the soft burr of his native valley in his speech. Young men from different worlds but fired by the same romantic vision: to escape the cramping, class-confined dullness of interwar England and see the world. Both went, in Leigh-Fermor’s words, ‘to set out across Europe like a tramp..A new life! Freedom! Something to write about!’

Laurie Lee

Laurie LeeBoth travelled on foot on what would prove to be life-changing experiences; both would write brilliantly about what they’d seen. Leigh-Fermor walked the length of Europe – from the tip of Holland to Constantinople. The journey took him a year; but he didn’t see the white cliffs of Dover again for three, ‘a whole life time later it seemed then – and, for better or for worse, utterly changed by my travels.’ Along the way he learned multiple languages, stayed with the aristocracy of central Europe, fell in love and lived the days with a thrilling intensity.

Laurie caught a boat to Spain and walked across the heat-stunned landscapes of the central plateau, sleeping out under olive trees, welcomed in to share the food of its peasants who were enchanted by the fair-haired stranger. His passport was his violin. In this Homeric world, he captivated the souls of the people with his music. He made them laugh, dance, cry and temporarily forget their suffering: ‘They lived hard and semi-starved lives, but if I unrolled my blanket…and they saw my violin their faces would soften and crease, there’d be a cry of Musica! Musica!...I’d play paso dobles and even the old ladies would dance a few creaky steps around the patio.’

Laurie caught a boat to Spain and walked across the heat-stunned landscapes of the central plateau, sleeping out under olive trees, welcomed in to share the food of its peasants who were enchanted by the fair-haired stranger. His passport was his violin. In this Homeric world, he captivated the souls of the people with his music. He made them laugh, dance, cry and temporarily forget their suffering: ‘They lived hard and semi-starved lives, but if I unrolled my blanket…and they saw my violin their faces would soften and crease, there’d be a cry of Musica! Musica!...I’d play paso dobles and even the old ladies would dance a few creaky steps around the patio.’ These were young men’s experiences – Leigh-Fermor was 18, Laurie Lee 21 –journeys of adventure, escape, romance. They both looked at new worlds for the first time, entranced, and noticed everything. They kept note books – and years later they would produce extraordinary artfully-shaped classics of travel writing: Patrick Leigh-Fermor’s A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water, Laurie Lee’s As I Walked out One Summer Morning and A Rose for Winter.

Both men had complex, adventurous and – in ways – difficult lives after these first journeys. Laurie Lee returned to Spain to fight in the Civil War; Patrick Leigh-Fermor became immensely famous for his years in the Cretan mountains in the Second World War and the kidnapping of the German general there. They both drank too much, had complicated love lives, wrote too little and perhaps squandered their talents. Laurie Lee is now best known for his childhood account of the village he grew up in – Cider with Rosie (in the US, Edge of Day), but you have the feeling that nothing ever equalled the intense experiences of those early travels. And in a world in which everything can now be seen from Google Earth it’s hard not to envy their journeys without maps.

I was once tempted to send Patrick Leigh-Fermor a copy of my book on the fall of Constantinople, as he knew the Greek world deeply and lived there for most of his life, but never did, and didn’t want to be a ‘fan’. Laurie Lee I never spoke to but knew by sight as he returned to Slad, the village of his childhood, and we live nearby. (My wife once helped him plant a commemorative tree by our village cricket pitch, which he owned: she almost had to stop the sadly decrepit old man falling into the hole dug for the planting. I once watched him shuffling off the train at the local station with a half-drunk bottle of whisky stuffed in his coat pocket.) Both men lie buried in Gloucestershire churchyards.

Today – on a blue, sunny, bone-dry, and unseasonably cold Spring morning – I went on a whim to pay my respects to Laurie in the Slad churchyard looking across the road down which he departed that summer day in 1935 to the valley and the hills beyond. Inside the church there are some quite lovely stained glass windows that depict his travels to Spain, his violin and his words.

Today – on a blue, sunny, bone-dry, and unseasonably cold Spring morning – I went on a whim to pay my respects to Laurie in the Slad churchyard looking across the road down which he departed that summer day in 1935 to the valley and the hills beyond. Inside the church there are some quite lovely stained glass windows that depict his travels to Spain, his violin and his words.

Published on March 30, 2013 09:56

March 17, 2013

Plague routes

This week I have found myself staring at photographs in the press of a perfectly round, very deep and ominously black pit. At the bottom a row of human skeletons.

It’s probably a plague pit discovered during the building of a cross-London rail link, going back to the arrival of the Black Death in London in 1348. Paleoepidemiologists – it’s a new job to me – are hoping to extract sufficient DNA material from bone samples to determine the cause of death.

Because I wrote something about the origins of the Black Death in my book about Venice, I found myself thinking back to the winter of 1344, when a large Mongol army was beseiging the Genoese fortress of Kaffa on the Crimean peninsula. The attackers failed to take the fort – its walls were thick and Mongol siege equipment evidently wasn’t up to the job. As they sat outside the walls the Mongols mysteriously started to die. A contemporary chronicler recorded what happened next:

‘Disease seized and struck down the whole Tatar army. Every day unknown thousands perished . . . they died as soon as the symptoms appeared on their bodies, the result of coagulating humours in their groins and armpits followed by putrid fever. All medical advice and help was useless. The Tatars, exhausted, astonished and completely demoralised by the appalling catastrophe and virulent disease, realised that there was no hope of avoiding death . . . and ordered the corpses to be loaded into their catapults and flung into Caffa, so that the enemy might be wiped out by the terrible stench. It appears that huge piles of dead were hurled inside, and the Christians could neither hide, flee nor escape from these corpses, which they tried to dump in the sea, as many as they could. The air soon became completely infected and the water supply was poisoned by rotting corpses.’

When the siege failed, the Genoese (and Venetians) sailed away, carrying the Black Death with them so efficiently that it had ringed the western world within a couple of years, spreading down the maritime trade routes of Europe – ships were the engines of globalization in all its forms:

Maybe now it’s the plane. This week scientists recorded tremors of a modern pandemic threat: the Sars virus killed a man in London who had taken the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. Where humans meet in large numbers the potential for interactions are uncontrollable. The great flu pandemic of 1918 that killed more people than the First World War (perhaps 50 to 100 million) was efficiently spread across Europe by the large troop concentrations in camps in Belgium and Northern France. Let’s hope the epidemiologists don’t let anything lethal escape from the sub-soil of London.

It’s probably a plague pit discovered during the building of a cross-London rail link, going back to the arrival of the Black Death in London in 1348. Paleoepidemiologists – it’s a new job to me – are hoping to extract sufficient DNA material from bone samples to determine the cause of death.

Because I wrote something about the origins of the Black Death in my book about Venice, I found myself thinking back to the winter of 1344, when a large Mongol army was beseiging the Genoese fortress of Kaffa on the Crimean peninsula. The attackers failed to take the fort – its walls were thick and Mongol siege equipment evidently wasn’t up to the job. As they sat outside the walls the Mongols mysteriously started to die. A contemporary chronicler recorded what happened next:

‘Disease seized and struck down the whole Tatar army. Every day unknown thousands perished . . . they died as soon as the symptoms appeared on their bodies, the result of coagulating humours in their groins and armpits followed by putrid fever. All medical advice and help was useless. The Tatars, exhausted, astonished and completely demoralised by the appalling catastrophe and virulent disease, realised that there was no hope of avoiding death . . . and ordered the corpses to be loaded into their catapults and flung into Caffa, so that the enemy might be wiped out by the terrible stench. It appears that huge piles of dead were hurled inside, and the Christians could neither hide, flee nor escape from these corpses, which they tried to dump in the sea, as many as they could. The air soon became completely infected and the water supply was poisoned by rotting corpses.’

When the siege failed, the Genoese (and Venetians) sailed away, carrying the Black Death with them so efficiently that it had ringed the western world within a couple of years, spreading down the maritime trade routes of Europe – ships were the engines of globalization in all its forms:

Maybe now it’s the plane. This week scientists recorded tremors of a modern pandemic threat: the Sars virus killed a man in London who had taken the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. Where humans meet in large numbers the potential for interactions are uncontrollable. The great flu pandemic of 1918 that killed more people than the First World War (perhaps 50 to 100 million) was efficiently spread across Europe by the large troop concentrations in camps in Belgium and Northern France. Let’s hope the epidemiologists don’t let anything lethal escape from the sub-soil of London.

Published on March 17, 2013 15:02

March 7, 2013

Down to the sea in ships

I spend a fair amount of my writing time thinking about boats. Maritime history features quite prominently in my books and I try to get a clear sense of what it would be like to have been on a particular type of ship – and the life of the men who sailed, explored and fought on them. I’ll visit maritime museums at the drop of a hat to peer at seamen’s chests, charts, compasses, paintings and rusting pieces of iron salvaged from the depths.

The one thing that’s usually missing – when you go back more than a couple of hundred years – is the ships themselves. The sea is an unforgiving medium for wood. There is, to my knowledge, only one authentic galley still in existence – and that’s from the eighteenth century. It’s in the Istanbul naval museum – photographed at rather a curious angle it must be said – but it gives a good idea of the claustrophobia of the galley life.

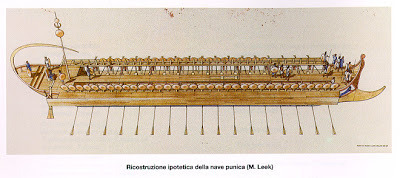

All that’s often recovered from silt-covered underwater burial sites, are a few unspectacular fragments. Here’s the earliest recovered remains of a warship, which I saw last year.

All that’s often recovered from silt-covered underwater burial sites, are a few unspectacular fragments. Here’s the earliest recovered remains of a warship, which I saw last year.

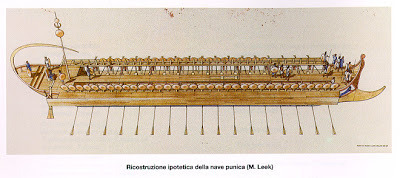

It’s a Phoenician vessel sunk off Sicily in 241 BC in a decisive battle against the Romans during the contest for control of the Mediterranean. I guess it’s about typical of what can be retrieved. The rest has to be re-imagined. Archaeologists have reconstructed this:

Though the battle was made more vivid by the recovery from the sea bed of bronze plated fighting rams and Phoenician helmets:

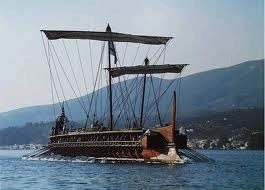

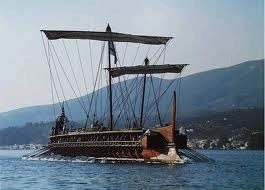

Because of the sketchy physical evidence there seems to be lively debate among maritime historians and archaeologists about what many of these ships really looked like – how big they were, their steering devices, fighting equipment and so on. There are occasional fascinating projects to recreate vessels from the past. There was a famous reconstruction of a Greek trireme in the 1980s which settled an academic argument – proving that a three-level arrangement of oars was practical:

The trireme Olympias

The trireme Olympias

And I’ve been interested by a recent recreation of a Bronze Age British boat, hewn out of oak, and caulked with moss and animal fat, to answer questions about seafaring 4000 years ago: Here’s the launch. It leaked somewhat!

Here’s the launch. It leaked somewhat!

I hugely enjoyed stepping aboard a replica caravel last year in Lisbon harbour. Caravels, with their triangular ‘Latin’ sails were the ships that launched the Portuguese on their voyages of discovery in the fifteenth century:

The Vera Cruz

The Vera Cruz

Good at sailing against the wind and shallow-draughted enough to sail up rivers, they enabled the exploration of the whole of the coast of West Africa and the decoding of the Atlantic wind systems. They paved the way for the final cracking of a route to India by Vasco da Gama in 1498. Stepping aboard, you get an idea of just how small these boats were, as they ploughed their way through the mountainous ocean seas. The Vera Cruz is only 23 metres, 75 feet long. There’s precious little room for the crew working the enormous sails – the main mast is longer than the ship – in all weathers.

All that’s missing is a sense of the sheer toughness of the sailor’s life: the swamping seas, the terrible calms under the hot sun, the foetid squalour and stink of a vessel during a long voyage, the fleas and the rancid biscuits and the foul drinking water, the scurvy and the accidental drownings. In fact I realise I’m quite happy just to write about it all!

The one thing that’s usually missing – when you go back more than a couple of hundred years – is the ships themselves. The sea is an unforgiving medium for wood. There is, to my knowledge, only one authentic galley still in existence – and that’s from the eighteenth century. It’s in the Istanbul naval museum – photographed at rather a curious angle it must be said – but it gives a good idea of the claustrophobia of the galley life.

All that’s often recovered from silt-covered underwater burial sites, are a few unspectacular fragments. Here’s the earliest recovered remains of a warship, which I saw last year.

All that’s often recovered from silt-covered underwater burial sites, are a few unspectacular fragments. Here’s the earliest recovered remains of a warship, which I saw last year.

It’s a Phoenician vessel sunk off Sicily in 241 BC in a decisive battle against the Romans during the contest for control of the Mediterranean. I guess it’s about typical of what can be retrieved. The rest has to be re-imagined. Archaeologists have reconstructed this:

Though the battle was made more vivid by the recovery from the sea bed of bronze plated fighting rams and Phoenician helmets:

Because of the sketchy physical evidence there seems to be lively debate among maritime historians and archaeologists about what many of these ships really looked like – how big they were, their steering devices, fighting equipment and so on. There are occasional fascinating projects to recreate vessels from the past. There was a famous reconstruction of a Greek trireme in the 1980s which settled an academic argument – proving that a three-level arrangement of oars was practical:

The trireme Olympias

The trireme OlympiasAnd I’ve been interested by a recent recreation of a Bronze Age British boat, hewn out of oak, and caulked with moss and animal fat, to answer questions about seafaring 4000 years ago:

Here’s the launch. It leaked somewhat!

Here’s the launch. It leaked somewhat!I hugely enjoyed stepping aboard a replica caravel last year in Lisbon harbour. Caravels, with their triangular ‘Latin’ sails were the ships that launched the Portuguese on their voyages of discovery in the fifteenth century:

The Vera Cruz

The Vera Cruz

Good at sailing against the wind and shallow-draughted enough to sail up rivers, they enabled the exploration of the whole of the coast of West Africa and the decoding of the Atlantic wind systems. They paved the way for the final cracking of a route to India by Vasco da Gama in 1498. Stepping aboard, you get an idea of just how small these boats were, as they ploughed their way through the mountainous ocean seas. The Vera Cruz is only 23 metres, 75 feet long. There’s precious little room for the crew working the enormous sails – the main mast is longer than the ship – in all weathers.

All that’s missing is a sense of the sheer toughness of the sailor’s life: the swamping seas, the terrible calms under the hot sun, the foetid squalour and stink of a vessel during a long voyage, the fleas and the rancid biscuits and the foul drinking water, the scurvy and the accidental drownings. In fact I realise I’m quite happy just to write about it all!

Published on March 07, 2013 02:37

February 24, 2013

'I feel the shake and am obliged to stop'

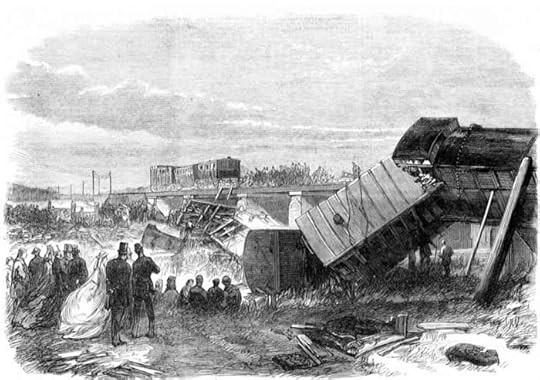

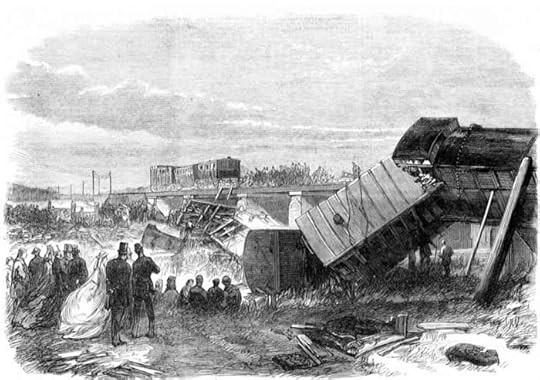

At 3.13pm on 9 June 1865, the Folkestone to London train was derailed whilst crossing a viaduct in Kent. Half the coaches were whipped over the edge and smashed into a dry river 10 feet below. One of the carriages remained suspended, half on and half off the bridge.

The Staplehurst rail crash, in which ten people died, became famous, not just for its casualties, but for the presence and actions of one of the passengers left precariously hanging between life and death in that first class carriage. He was Charles Dickens. In a letter to a friend he described the moment of impact:

‘I was in the only carriage that did not go over into the stream. It was caught upon the turn by some of the ruin of the bridge, and hung suspended and balanced in an apparently impossible manner. Two ladies were my fellow passengers; an old one, and a young one. Suddenly we were off the rail and beating the ground as the car of a half emptied balloon might. The old lady cried out “My God!” and the young one screamed.

I caught hold of them both (the old lady sat opposite, and the young one on my left) and said: “We can't help ourselves, but we can be quiet and composed. Pray don't cry out.” The old lady immediately answered, “Thank you. Rely upon me. Upon my soul, I will be quiet.” The young lady said in a frantic way, Let us join hands and die, friends.” We were then all tilted down together in a corner of the carriage, and stopped. I said to them thereupon: “You may be sure nothing worse can happen. Our danger must be over. Will you remain here without stirring, while I get out of the window?” They both answered quite collectedly.’

Dickens climbed out the carriage – to survey a terrible scene.

‘Looking down, I saw the bridge gone and nothing below me but the line of the rail. Some people in the two other compartments were madly trying to plunge out of the window, and had no idea there was an open swampy field 15 feet down below them and nothing else! The two guards (one with his face cut) were running up and down on the down side of the bridge (which was not torn up) quite wildly. I called out to them “Look at me. Do stop an instant and look at me, and tell me whether you don't know me.” One of them answered, “We know you very well, Mr Dickens.” “Then,” I said, “my good fellow for God's sake give me your key, and send one of those labourers here, and I'll empty this carriage.”

We did it quite safely, by means of a plank or two and when it was done I saw all the rest of the train except the two baggage cars down in the stream. I got into the carriage again for my brandy flask, took off my travelling hat for a basin, climbed down the brickwork, and filled my hat with water. Suddenly I came upon a staggering man covered with blood (I think he must have been flung clean out of his carriage) with such a frightful cut across the skull that I couldn't bear to look at him. I poured some water over his face, and gave him some to drink, and gave him some brandy, and laid him down on the grass, and he said, “I am gone”, and died afterwards.

Then I stumbled over a lady lying on her back against a little pollard tree, with the blood streaming over her face (which was lead colour) in a number of distinct little streams from the head. I asked her if she could swallow a little brandy, and she just nodded, and I gave her some and left her for somebody else. The next time I passed her, she was dead. Then a man…came running up to me and implored me to help him find his wife, who was afterwards found dead. No imagination can conceive the ruin of the carriages, or the extraordinary weights under which the people were lying, or the complications into which they were twisted up among iron and wood, and mud and water. ‘

For his coolness and attempts at rescue Dickens emerged from this scene of carnage as the hero of the hour. ‘I don't want to be examined at the inquests,’ he wrote, ‘and I don't want to write about it. It could do no good either way, and I could only seem to speak about myself, which, of course, I would rather not do. I am keeping very quiet here. I have a – I don't know what to call it – constitutional (I suppose) presence of mind, and was not in the least flustered at the time. I instantly remembered that I had the manuscript of a novel with me, and clambered back into the carriage for it.’

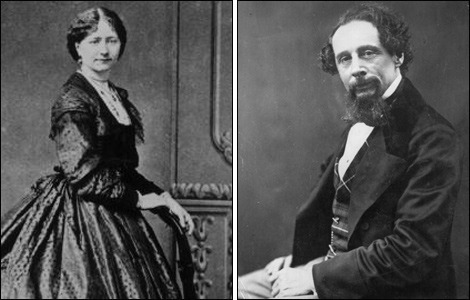

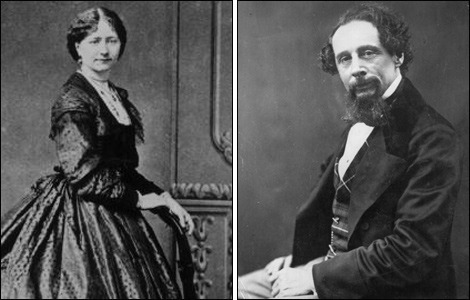

Dickens had other reasons, apart from dreadful recollection, for not wanting to attend the inquest. The two unnamed women in the carriage were his secret mistress, Ellen Ternan ‘the invisible woman’, and her mother. Both were spirited away quickly from the scene – Dickens, with the reputation of an adoring public to maintain, wanted no publicity.

Ellen Ternan and Charles DickensThe Staplehurst railway crash reads like a melodramatic scene from one of his own novels – and he drew on it for a ghost story, The Signal Man, that he subsequently wrote. In truth it spooked him badly. He lost his voice for a fortnight and never fully recovered. ‘I am a little shaken,' he added in his letter, ‘not by the beating and dragging of the carriage in which I was, but by the hard work afterwards in getting out the dying and dead, which was most horrible…in writing these scanty words of recollection, I feel the shake and am obliged to stop.’ It was almost a harbinger of his own death. He died five years later to the day, on 9 June 1870.

Ellen Ternan and Charles DickensThe Staplehurst railway crash reads like a melodramatic scene from one of his own novels – and he drew on it for a ghost story, The Signal Man, that he subsequently wrote. In truth it spooked him badly. He lost his voice for a fortnight and never fully recovered. ‘I am a little shaken,' he added in his letter, ‘not by the beating and dragging of the carriage in which I was, but by the hard work afterwards in getting out the dying and dead, which was most horrible…in writing these scanty words of recollection, I feel the shake and am obliged to stop.’ It was almost a harbinger of his own death. He died five years later to the day, on 9 June 1870.

The Staplehurst rail crash, in which ten people died, became famous, not just for its casualties, but for the presence and actions of one of the passengers left precariously hanging between life and death in that first class carriage. He was Charles Dickens. In a letter to a friend he described the moment of impact:

‘I was in the only carriage that did not go over into the stream. It was caught upon the turn by some of the ruin of the bridge, and hung suspended and balanced in an apparently impossible manner. Two ladies were my fellow passengers; an old one, and a young one. Suddenly we were off the rail and beating the ground as the car of a half emptied balloon might. The old lady cried out “My God!” and the young one screamed.

I caught hold of them both (the old lady sat opposite, and the young one on my left) and said: “We can't help ourselves, but we can be quiet and composed. Pray don't cry out.” The old lady immediately answered, “Thank you. Rely upon me. Upon my soul, I will be quiet.” The young lady said in a frantic way, Let us join hands and die, friends.” We were then all tilted down together in a corner of the carriage, and stopped. I said to them thereupon: “You may be sure nothing worse can happen. Our danger must be over. Will you remain here without stirring, while I get out of the window?” They both answered quite collectedly.’

Dickens climbed out the carriage – to survey a terrible scene.

‘Looking down, I saw the bridge gone and nothing below me but the line of the rail. Some people in the two other compartments were madly trying to plunge out of the window, and had no idea there was an open swampy field 15 feet down below them and nothing else! The two guards (one with his face cut) were running up and down on the down side of the bridge (which was not torn up) quite wildly. I called out to them “Look at me. Do stop an instant and look at me, and tell me whether you don't know me.” One of them answered, “We know you very well, Mr Dickens.” “Then,” I said, “my good fellow for God's sake give me your key, and send one of those labourers here, and I'll empty this carriage.”

We did it quite safely, by means of a plank or two and when it was done I saw all the rest of the train except the two baggage cars down in the stream. I got into the carriage again for my brandy flask, took off my travelling hat for a basin, climbed down the brickwork, and filled my hat with water. Suddenly I came upon a staggering man covered with blood (I think he must have been flung clean out of his carriage) with such a frightful cut across the skull that I couldn't bear to look at him. I poured some water over his face, and gave him some to drink, and gave him some brandy, and laid him down on the grass, and he said, “I am gone”, and died afterwards.

Then I stumbled over a lady lying on her back against a little pollard tree, with the blood streaming over her face (which was lead colour) in a number of distinct little streams from the head. I asked her if she could swallow a little brandy, and she just nodded, and I gave her some and left her for somebody else. The next time I passed her, she was dead. Then a man…came running up to me and implored me to help him find his wife, who was afterwards found dead. No imagination can conceive the ruin of the carriages, or the extraordinary weights under which the people were lying, or the complications into which they were twisted up among iron and wood, and mud and water. ‘

For his coolness and attempts at rescue Dickens emerged from this scene of carnage as the hero of the hour. ‘I don't want to be examined at the inquests,’ he wrote, ‘and I don't want to write about it. It could do no good either way, and I could only seem to speak about myself, which, of course, I would rather not do. I am keeping very quiet here. I have a – I don't know what to call it – constitutional (I suppose) presence of mind, and was not in the least flustered at the time. I instantly remembered that I had the manuscript of a novel with me, and clambered back into the carriage for it.’

Dickens had other reasons, apart from dreadful recollection, for not wanting to attend the inquest. The two unnamed women in the carriage were his secret mistress, Ellen Ternan ‘the invisible woman’, and her mother. Both were spirited away quickly from the scene – Dickens, with the reputation of an adoring public to maintain, wanted no publicity.

Ellen Ternan and Charles DickensThe Staplehurst railway crash reads like a melodramatic scene from one of his own novels – and he drew on it for a ghost story, The Signal Man, that he subsequently wrote. In truth it spooked him badly. He lost his voice for a fortnight and never fully recovered. ‘I am a little shaken,' he added in his letter, ‘not by the beating and dragging of the carriage in which I was, but by the hard work afterwards in getting out the dying and dead, which was most horrible…in writing these scanty words of recollection, I feel the shake and am obliged to stop.’ It was almost a harbinger of his own death. He died five years later to the day, on 9 June 1870.

Ellen Ternan and Charles DickensThe Staplehurst railway crash reads like a melodramatic scene from one of his own novels – and he drew on it for a ghost story, The Signal Man, that he subsequently wrote. In truth it spooked him badly. He lost his voice for a fortnight and never fully recovered. ‘I am a little shaken,' he added in his letter, ‘not by the beating and dragging of the carriage in which I was, but by the hard work afterwards in getting out the dying and dead, which was most horrible…in writing these scanty words of recollection, I feel the shake and am obliged to stop.’ It was almost a harbinger of his own death. He died five years later to the day, on 9 June 1870.

Published on February 24, 2013 02:45

February 16, 2013

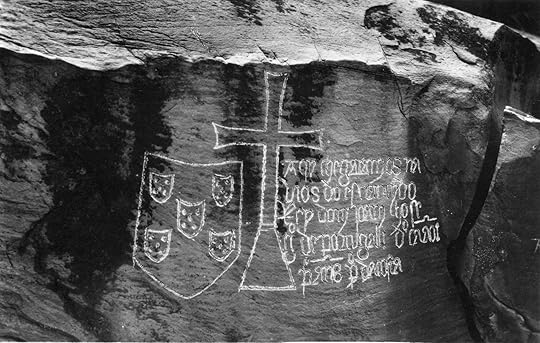

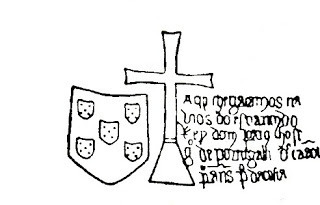

Scratchings on a rock

At present I’m writing a book about the Portuguese exploration of the world. Vasco da Gama’s rounding of Africa in 1497 stands as a pivotal moment in world history – the start of the long process of globalization which preoccupies us so much today – but his arrival in India was no overnight breakthrough. It came on the back of half a century of slogging exploration of the African coast. In retrospect the Portuguese seemed indefatigable in their endurance and their willingness to push themselves over the edge of the known world. Men vanished in small ships and rough seas, or died of malaria and poisoned arrows on probes up the continent’s vast rivers, the Senegal, the Gambia and the Niger, in search of an elusive short cut to the Indian Ocean

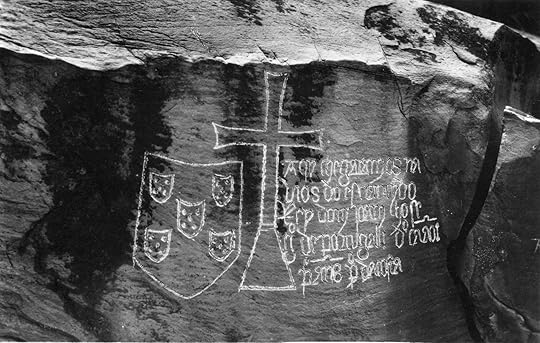

There is no more poignant memorial to this process than a monument left by the sailors of the Portuguese captain Diogo Cao up the River Congo at the Yellala Falls, a site so remote that there would be no further recorded European visitor for 300 years. Whoever came here in about 1485, sailed, or rowed 100 miles upstream from the sea along the mysterious and densely forested banks of this immensely powerful river. As they pushed their way east, the current increased in ferocity until they reached a rocky gorge, and the thunder of mighty waterfalls, a colossal torrent of water pouring out of the heart of Africa. The Portuguese could sail no further. Undeterred they abandoned their ship or ships and scrambled ten miles over the rocks, in the hope of finding navigable water upstream, but the succession of rapids defeated them.

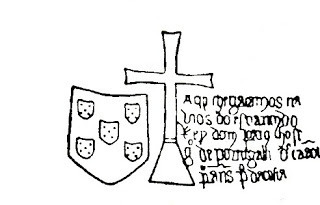

This venture is completely unrecorded in Portuguese chronicles. The only testimony is hidden on the rock wall of an overhanging cliff high above the crashing torrent, where the seamen left a carving. It shows the arms of King John II, the energetic Portuguese king who must have ordered this expedition. Next to it there is a cross and some names: ‘Here arrived the ships of the illustrious monarch Dom Joao the Second of Portugal, Diogo Cao, Pedro Anes, Pedro da Costa, Alvaro Pyris, Pero Escolar A…’ To the lower right and carved in a different hand, there is a second group of names: ‘Joao de Samtyago, Diogo Pinheiro, Goncalo Alvares + of sickness Joao Alvares…’ And in another place, just a Christian name: ‘Antam' [Antao = Anthony]

To the lower right and carved in a different hand, there is a second group of names: ‘Joao de Samtyago, Diogo Pinheiro, Goncalo Alvares + of sickness Joao Alvares…’ And in another place, just a Christian name: ‘Antam' [Antao = Anthony]

All these inscriptions seem broken off – their circumstances as ambiguous as a last entry in the diary of a polar explorer. They give us the names of the men who commanded the ships – Diogo Cao and the others by the cross; but the commanders were probably not present. It is likely that Cao sent the expedition upriver to probe the navigability of the Congo and it is the men in the second group who actually made the trip. It is probable that both inscriptions were being carved at the same time; and both are incomplete, as if interrupted at the same moment. Evidently men were ill or dead – probably of malaria. There is no date. Were they too weak to continue? Were they surprised or attacked as they scratched away at the rock? No date is recorded; nor is there any other record of this probe into the heart of Africa, which remained undiscovered until 1911. We know at least that some of the men must have made it back because one of them, Joao de Samtyago [Santiago], was a pilot on a famous follow-up voyage by Bartolomeu Dias, who rounded the Cape of Good Hope for the first time in 1488.

There is no more poignant memorial to this process than a monument left by the sailors of the Portuguese captain Diogo Cao up the River Congo at the Yellala Falls, a site so remote that there would be no further recorded European visitor for 300 years. Whoever came here in about 1485, sailed, or rowed 100 miles upstream from the sea along the mysterious and densely forested banks of this immensely powerful river. As they pushed their way east, the current increased in ferocity until they reached a rocky gorge, and the thunder of mighty waterfalls, a colossal torrent of water pouring out of the heart of Africa. The Portuguese could sail no further. Undeterred they abandoned their ship or ships and scrambled ten miles over the rocks, in the hope of finding navigable water upstream, but the succession of rapids defeated them.

This venture is completely unrecorded in Portuguese chronicles. The only testimony is hidden on the rock wall of an overhanging cliff high above the crashing torrent, where the seamen left a carving. It shows the arms of King John II, the energetic Portuguese king who must have ordered this expedition. Next to it there is a cross and some names: ‘Here arrived the ships of the illustrious monarch Dom Joao the Second of Portugal, Diogo Cao, Pedro Anes, Pedro da Costa, Alvaro Pyris, Pero Escolar A…’

To the lower right and carved in a different hand, there is a second group of names: ‘Joao de Samtyago, Diogo Pinheiro, Goncalo Alvares + of sickness Joao Alvares…’ And in another place, just a Christian name: ‘Antam' [Antao = Anthony]

To the lower right and carved in a different hand, there is a second group of names: ‘Joao de Samtyago, Diogo Pinheiro, Goncalo Alvares + of sickness Joao Alvares…’ And in another place, just a Christian name: ‘Antam' [Antao = Anthony]All these inscriptions seem broken off – their circumstances as ambiguous as a last entry in the diary of a polar explorer. They give us the names of the men who commanded the ships – Diogo Cao and the others by the cross; but the commanders were probably not present. It is likely that Cao sent the expedition upriver to probe the navigability of the Congo and it is the men in the second group who actually made the trip. It is probable that both inscriptions were being carved at the same time; and both are incomplete, as if interrupted at the same moment. Evidently men were ill or dead – probably of malaria. There is no date. Were they too weak to continue? Were they surprised or attacked as they scratched away at the rock? No date is recorded; nor is there any other record of this probe into the heart of Africa, which remained undiscovered until 1911. We know at least that some of the men must have made it back because one of them, Joao de Samtyago [Santiago], was a pilot on a famous follow-up voyage by Bartolomeu Dias, who rounded the Cape of Good Hope for the first time in 1488.

Published on February 16, 2013 03:19

February 8, 2013

Bring up the bodies?

A last post about Richard III. Here’s his face reconstructed from the skull.

What’s really fascinated me about the finding of his body – apart from the discovery itself – has been the reactions to it. Fellow academic historians and archaeologists seem to have been depressingly dismissive about the historical value of Leicester’s find and the way that the University have played it up. There’s a shrivelling whiff of miserablist sour grapes about all this. The finding of named individuals from the past is incredibly rare – and I bet if any classicist were offered the chance to look on the mortal remains of Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar the response would be rather different. This find is a chance for ordinary people to touch the past – to be thrilled by the reality of what happened long ago and for academic work to spark popular interest. The professionals should be celebrating a moment for their discipline to make it into the limelight.

There’s also something wonderfully medieval about the attitude to these bones. The city of York has made a counterclaim for the body because that’s where Richard came from. It’s just a modern squabble over who gets a saint’s relics – the citizens of Bari and Venice fighting over who had the bones of St Nicholas in the Middle Ages. It has, of course, nothing to do with the fitting place, but all about the modern religion of tourism – the bones of King Richard, wherever they are buried, will bring visitors to the city. The Venetians knew this well – and were prime holy body snatchers. St Mark was their trump card (if his bones ever existed) and ensured a rich stream of paying guests.

The Richard thing has also sparked a potential chain reaction of similar attempts. There’s a vicar in Winchester who thinks King Alfred is buried in his church and would like to find out. The Richard III society wants to exhume the bones of the princes in the Tower from Westminster Abbey for DNA testing. The Church of England is likely to stand firm on this. Richard was found in a car park but the Church is worried that voyeuristic exhumations from holy ground could open up a can (or coffin?) of worms. ‘Inter their bodies as becomes their births’, says the victorious Henry Tudor in Shakespeare’s play about Richard III.

What’s really fascinated me about the finding of his body – apart from the discovery itself – has been the reactions to it. Fellow academic historians and archaeologists seem to have been depressingly dismissive about the historical value of Leicester’s find and the way that the University have played it up. There’s a shrivelling whiff of miserablist sour grapes about all this. The finding of named individuals from the past is incredibly rare – and I bet if any classicist were offered the chance to look on the mortal remains of Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar the response would be rather different. This find is a chance for ordinary people to touch the past – to be thrilled by the reality of what happened long ago and for academic work to spark popular interest. The professionals should be celebrating a moment for their discipline to make it into the limelight.

There’s also something wonderfully medieval about the attitude to these bones. The city of York has made a counterclaim for the body because that’s where Richard came from. It’s just a modern squabble over who gets a saint’s relics – the citizens of Bari and Venice fighting over who had the bones of St Nicholas in the Middle Ages. It has, of course, nothing to do with the fitting place, but all about the modern religion of tourism – the bones of King Richard, wherever they are buried, will bring visitors to the city. The Venetians knew this well – and were prime holy body snatchers. St Mark was their trump card (if his bones ever existed) and ensured a rich stream of paying guests.

The Richard thing has also sparked a potential chain reaction of similar attempts. There’s a vicar in Winchester who thinks King Alfred is buried in his church and would like to find out. The Richard III society wants to exhume the bones of the princes in the Tower from Westminster Abbey for DNA testing. The Church of England is likely to stand firm on this. Richard was found in a car park but the Church is worried that voyeuristic exhumations from holy ground could open up a can (or coffin?) of worms. ‘Inter their bodies as becomes their births’, says the victorious Henry Tudor in Shakespeare’s play about Richard III.

Published on February 08, 2013 08:24

February 4, 2013

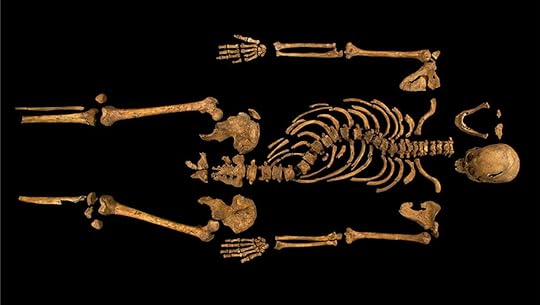

A wonderful day for archaeology

This morning I watched the quite extraordinary press conference called by the archaeologists of Leicester University in which they explained how they now know that this skeleton, found under a city car park, was, beyond all doubt, that of Richard III, the last Plantagenet king, killed on Bosworth Field on 22 August 1485. They walked soberly through the evidence – carbon-dating, osteo analysis, DNA capture from the bones and from known descendants, to construct an overwhelmingly convincing account of the man, his physique, his wounds and his manner of death in battle. The shiver of touching the past.

He had been wounded in ten places. His skull had been grievously injured – probably Richard lost his helmet.

The major wounds are to the base of the skull, either side of the spine, and would have been caused by heavy bladed weapons. His body was subsequently mutilated after death, tossed naked onto a horse and dumped in a rough grave in the now vanished church of Greyfriars. Richard III, ‘deform'd, unfinish'd, sent before my time/Into this breathing world, scarce half made up’ - Shakespeare’s hunchback - did indeed have a curvature of the spine.

It was all incredibly moving. We were reminded by the canon of Leicester Cathedral, that this is not just a historically gripping discovery. It concerns the remains of a human being. Richard will be reburied in the cathedral.

Archaeology is a Cinderella profession in these cash-strapped times but this was an astonishing testimony to its ability to bring all the tools of scientific analysis to unlock the past. For the men and women who talked at the press conference – and for the hundreds of hours of patient analysis by them and many others in universities and laboratories across Britain – this must have been a crowning moment in their professional lives.

Published on February 04, 2013 09:02

February 3, 2013

Tomorrow we will know

If the skeleton found under a carpark in Leicester is that of Richard III, the last king of England to die in battle - at Bosworth in 1485 - an event which ended the civil wars and ushered in the Tudors...

There's a Richard III Society in England, keen to re-establish the reputation of the man whom Shakespeare smeared on behalf of Elizabeth, the Tudor queen - and who may or may not have been responsible for the deaths of the princes in the Tower. Watch this space!

Published on February 03, 2013 11:44

January 27, 2013

Carnival season in Venice

The start of the Venice carnival. Almost a scene invented by Fellini: torches flaring on the water; beaked masks; gondolas carrying winged animals; enormous wheeled water machines; fantastic animals; mystery and drifting smoke in the darkness. The origins of the Venetian carnival are very old, even if in its recreated form it’s modern. Carnival was a time of celebration, of freedom from the restraints of your own social identity, of licence. A man or woman could become something else. Like all winter festivals it served a psychological function – here a release for people in this most constrained and self-disciplined of cities.

There was something grotesque as well as gorgeous in the spectacle. With the freedom came sinister overtones too: opportunity for anonymous crime – the blade slipped between the ribs by a man in a back street masked as a plague doctor, dangerous liaisons, gambling debts. The carnival – which traditionally lasted from St Stephen’s day (26 December) until Shrove Tuesday – also made the authorities nervous. The wearing of masks became fiercely controlled, circumscribed with prohibitions – the spectacle and its liberties tested the boundaries of social control. But sometimes, after extraordinary events, such as news of the victory of the great sea battle of Lepanto in October 1571, the masks would be given an extra licence, shops would shut, prisoners let out of jail, and Venice would become again a fantastic and brilliantly coloured dream, a creation of the imagination unlike anything in the visible world.

There was something grotesque as well as gorgeous in the spectacle. With the freedom came sinister overtones too: opportunity for anonymous crime – the blade slipped between the ribs by a man in a back street masked as a plague doctor, dangerous liaisons, gambling debts. The carnival – which traditionally lasted from St Stephen’s day (26 December) until Shrove Tuesday – also made the authorities nervous. The wearing of masks became fiercely controlled, circumscribed with prohibitions – the spectacle and its liberties tested the boundaries of social control. But sometimes, after extraordinary events, such as news of the victory of the great sea battle of Lepanto in October 1571, the masks would be given an extra licence, shops would shut, prisoners let out of jail, and Venice would become again a fantastic and brilliantly coloured dream, a creation of the imagination unlike anything in the visible world.

There was something grotesque as well as gorgeous in the spectacle. With the freedom came sinister overtones too: opportunity for anonymous crime – the blade slipped between the ribs by a man in a back street masked as a plague doctor, dangerous liaisons, gambling debts. The carnival – which traditionally lasted from St Stephen’s day (26 December) until Shrove Tuesday – also made the authorities nervous. The wearing of masks became fiercely controlled, circumscribed with prohibitions – the spectacle and its liberties tested the boundaries of social control. But sometimes, after extraordinary events, such as news of the victory of the great sea battle of Lepanto in October 1571, the masks would be given an extra licence, shops would shut, prisoners let out of jail, and Venice would become again a fantastic and brilliantly coloured dream, a creation of the imagination unlike anything in the visible world.

There was something grotesque as well as gorgeous in the spectacle. With the freedom came sinister overtones too: opportunity for anonymous crime – the blade slipped between the ribs by a man in a back street masked as a plague doctor, dangerous liaisons, gambling debts. The carnival – which traditionally lasted from St Stephen’s day (26 December) until Shrove Tuesday – also made the authorities nervous. The wearing of masks became fiercely controlled, circumscribed with prohibitions – the spectacle and its liberties tested the boundaries of social control. But sometimes, after extraordinary events, such as news of the victory of the great sea battle of Lepanto in October 1571, the masks would be given an extra licence, shops would shut, prisoners let out of jail, and Venice would become again a fantastic and brilliantly coloured dream, a creation of the imagination unlike anything in the visible world.

Published on January 27, 2013 08:58

January 20, 2013

‘Sende som more canon bulletts’

Further on the battle for Painswick in the Civil War, following on from last week’s post. Someone sent me a copy of a letter from the Royalist commander, Sir William Vavasour, on the taking of the town. Seventeenth century English spelling is evidently more an art than a science and time has eaten holes in the original, which it’s a short, sharp request for some more artillery to flush out Parliamentary troops still holed up in the town:

My Lo(rd)We have taken Painswicke, with ye loss of some men and ........ of much ......... the Rebells have possessed themselves of many Howses, wch wilbe taken in by canon, it must thearefore delyver yr Lo(rd) to sende mee 20 ...arelle of powdre more, with some hande granadoes and if you please to send a mortier peece, I shalbe able to doe his ma(jes)tye ye better servise and yr Lo will much obleige by it.Yr Lo most humble servantWill VavasourPainswicke 29th March 1643I beseach yr Lo sende som more canon bullets

Today Painswick, my local small town, is a more peaceful place – an old church, still bearing the scars of this battle, a picturesque churchyard famous for its yews and crumbling tombs, and streets of stone houses built on the prosperity of the Cotswold wool trade.

My Lo(rd)We have taken Painswicke, with ye loss of some men and ........ of much ......... the Rebells have possessed themselves of many Howses, wch wilbe taken in by canon, it must thearefore delyver yr Lo(rd) to sende mee 20 ...arelle of powdre more, with some hande granadoes and if you please to send a mortier peece, I shalbe able to doe his ma(jes)tye ye better servise and yr Lo will much obleige by it.Yr Lo most humble servantWill VavasourPainswicke 29th March 1643I beseach yr Lo sende som more canon bullets

Today Painswick, my local small town, is a more peaceful place – an old church, still bearing the scars of this battle, a picturesque churchyard famous for its yews and crumbling tombs, and streets of stone houses built on the prosperity of the Cotswold wool trade.

Published on January 20, 2013 13:19

Roger Crowley's Blog

- Roger Crowley's profile

- 820 followers

Roger Crowley isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.