The Sons of Sindbad

I have been deep in the Indian Oceanrecently – from the safety of my armchair, enraptured by a book called Sons of Sindbad by Allan Villiers. Villiers was an Australian master mariner, writer and photographer, who sailed and documented the last days of wind-powered navigation. In 1938-39, sensing the end of an era, he spent six months on an Arab dhow, sailing from Kuwait, down the coast of East Africa and back again.

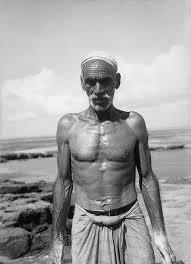

It’s a fascinating read – Villiers is the Wilfred Thesiger of the Arabian Seas– experiencing the traditional life of Indian Oceanseafaring that stretched back thousands of years. He arranged passage on a big wooden dhow, The Triumph of Righteousness, living with the crew, learning Arabic and observing and participating in the working life of the ship, under its stern and imperious captain, Nejdi. The Triumph made no concessions to modernity. It had no radio, no navigational equipment beyond a compass, – and no lights at night. The great triangular lateen sail was manhandled by the crew who performed extraordinary feats of physical endurance. Everyone slept on deck under the stars – or in the rain – as the ship made its way down the coast of East Africa, trading, ferrying passengers and smuggling. At times it was unbearably cramped and Villiers does not romanticise the conditions. They transported a large party of Bedouin – 180 people in all – cramped onto an open deck 70 feet long all the way to Mombasa. The few women were stashed away in a malodorous rat infested cabin. Fully loaded with passengers the ship stank – a combination of fish oil, vomit and bilge water - and the food – rice and fermenting fish – cooked in a sandbox was at best monotonous. In this floating souk, goats are slaughtered, the Bedouin are seasick, quarrels break out – quelled by Captain Nejdi with a slashing cane. In the harem cabin a girl dies. Villiers with his small medicine chest is looked upon to pronounce the cause of death. The most likely explanation is poison – administered by a jealous rival.

Villiers does not romanticise the voyage but he was enthralled by the experience. He appreciated the extraordinary skill, fortitude and dignity of the crew and their captain, their handling of the ship and the timeless rhythm of the voyage. When a Bedouin boy is knocked off the ship into a shark infested sea, two sailors spontaneously dive in after him; Nejdi executes a skilful manoeuvre turning the ship round in the lee of a rocky shore; no one panics. The child is rescued. No one says a word. The sailors go back to work.

And there is always work to do – raising and lowering the sails, mending them, plaiting ropes; periodically the ship has to be hauled out of the water, the hull scraped down and coated with fish oil and camel tallow. Sleep is in snatches. The life is so hard that a man of thirty looks fifty. Five times a day they are led in prayer – and as they work they sing and dance, hammering the deck with their bare calloused feet, so loudly that sometimes the orders from the wheel are inaudible. They sing as they haul the sails up and down, they sing and dance as they enter and leave port to the banging of drums. They sing to the sails and they sing to their captain in a deep rumbling chant:

And there is always work to do – raising and lowering the sails, mending them, plaiting ropes; periodically the ship has to be hauled out of the water, the hull scraped down and coated with fish oil and camel tallow. Sleep is in snatches. The life is so hard that a man of thirty looks fifty. Five times a day they are led in prayer – and as they work they sing and dance, hammering the deck with their bare calloused feet, so loudly that sometimes the orders from the wheel are inaudible. They sing as they haul the sails up and down, they sing and dance as they enter and leave port to the banging of drums. They sing to the sails and they sing to their captain in a deep rumbling chant:“Nejdi has brought us here,

Nejdi, good master:

Thanks be to Allah,

Always the merciful.”

And at the end of each day they present themselves at the poop to ask their captain's blessing. There is no set itinerary. Villiers gives up asking exactly where they are going or how long they will stay in port. During a lunar eclipse, the whole ship is filled with superstitious dread and falls to its knees to pray for the return of the 'Prophet's Lantern'. It is an ancient world.

Sometimes the experience is ghastly – they spend a month in the delta of a miasmic tropical river, collecting mangrove poles to transport back to Kuwaitfor building projects. It rains continuously. The mosquitoes gather in swarms. There is no protection from them day or night. The men go down with fever. And the work is incredibly hard. Villiers is hit on the head by an object falling from the mast and blinded for a week. No one gives an explanation for the accident – everything is as Allah wills. But when the Triumph approaches Zanzibarrising excitement infects the crew. They don their best clothes, sing the ship in and depart to spend what money they have in the town’s brothels. Smugglers come and go at night.

Sometimes the experience is ghastly – they spend a month in the delta of a miasmic tropical river, collecting mangrove poles to transport back to Kuwaitfor building projects. It rains continuously. The mosquitoes gather in swarms. There is no protection from them day or night. The men go down with fever. And the work is incredibly hard. Villiers is hit on the head by an object falling from the mast and blinded for a week. No one gives an explanation for the accident – everything is as Allah wills. But when the Triumph approaches Zanzibarrising excitement infects the crew. They don their best clothes, sing the ship in and depart to spend what money they have in the town’s brothels. Smugglers come and go at night. The dhow captains smoke their hookahs as they sail their ships and yarn in coffee shops when they land. The sailors have almost nothing; many of them are permanently in debt to captains and merchants. At the end of the voyage some of them are compelled to the most dreadful of occupations – pearl diving in the Persian Gulf – that surpassed any maritime suffering Villiers had ever seen – a kind of bonded labour that kills men even faster than sailing the big dhows.

But sometimes the voyage is an enchantment. Villiers is enraptured by the beauty of these ships bowling along with a good wind like enormous white butterflies and the extraordinary craft skills of the sailors and navigators: “Nejdi had no tables and he did not even know the date. The moon, he said was enough; the moon, the stars and the behaviour of the sea.”

[image error]

It’s a moving snapshot of a vanished world. These boats were at the end of a lineage stretching far back into antiquity. The voyaging cost almost nothing beyond the labour of the men and a Spartan diet. The ancient cosmopolitan trading patterns were slowly being extinguished by colonial rule and nation states, by steel ships with diesel engines and the oil boom in the Gulf States that will take men away from the seafaring life.

Thirty years later Villiers returned to Kuwait. He met Nejdi, now a rich man, at the airport. Villiers recalled the meeting.

“Allah is great,” I said. “His winds are free.”

“Allah is great,” Nejdi replied…”and sometimes I wish that I could use His winds again. For it was a good life that my sons can never know – no Kuwaitsons shall know. We cannot bring those ways back again.”

“Swell out, great sail,

And gather to your breast

God's wind,

For we are bound for home”.

Published on February 20, 2014 14:36

No comments have been added yet.

Roger Crowley's Blog

- Roger Crowley's profile

- 820 followers

Roger Crowley isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.