Felicity Hayes-McCoy's Blog

December 26, 2020

The Wran's Day in Dingle 2020

December 26, just after the winter solstice, is The Wran's Day, as much a part of the holiday season here in Corca Dhuibhne as Christmas Day itself. This year, because of Covid, and for the first time in living memory, the celebrations have had to be cancelled. The sorrow is palpable but so is the determination to come back even stronger next year. Here's an extract from my 2013 memoir The House on an Irish Hillside, to give an idea of what we're missing, and what we look forward to. 'If you study folklore or anthropology, you learn that the Wran’s Day belongs to a tradition that stretches back to the first people who came here, thousands of years before Christianity. Its name is a corruption of the English word ‘wren’, and in Irish it’s Lá an Dreoilín. There’s endles research on the Wran’s Day, and suggestions that dreoilín, the word for wren, comes from draoi-éan, ‘druid’s bird’. It’s linked to ancient midwinter festivals and shamanism, when a shared web of ideas and information was accessed like a form of internet powered by human energy, and to later folk traditions like Straw Boys and Guisers. Its rituals belong to a dream state beyond stories, or even words, when there were just images and rhythms. But if you turn up in Dingle on 26 December, what you’ll see is one big party. Basically, the town gets taken over by musicians and dancers. In the past, the boys back west used to dress up in rags and old coats turned inside out. They’d smear soot on their faces, or wear masks, and go from house to house, playing music and asking for pennies ‘to bury the wran’. Then they’d use the money to buy food and drink and throw a dance. Earlier still, live wrens used to be hunted and killed and carried in procession. Earlier than that, at huge ritual gatherings, kings offered themselves to be killed at the turn of the year, in an extreme version of sacrificing the best you’ve got in times of scarcity. Through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Church did its best to suppress the Wran’s Day. But it never succeeded; and its ancient, wordless rhythms are still felt here every year. Some kids still walk the country roads in costumes, and turn up at their neighbours’ houses to dance in the kitchen. Each group is called a ‘wran’. You hear the creak of the gate and the rattle of a drum outside the window. Then tattered figures with masked and painted faces crowd into the house, disguised in their granny’s aprons, padded with rolled-up socks; or their dad’s pyjamas, tied with rope and stuffed into wellingtons. As they come into the room, accordion players pull their masks down over their faces and whistle players push them onto their foreheads; the smaller figures giggle and shuffle. Then someone gives a note and the little group breaks into a jig or a polka. But these days most people head for Dingle instead, and join the rival parades that march and dance through the streets playing music. Máire Begley blames it on the carpets. "The real Wran went out the door the day the carpets came into the houses. No one wants mud on the floors nowadays. That’s why they all go in to Dingle!" The Wran’s Day in Dingle is famous. Nowadays, when the collections are for charities, the wrans compete to see who can raise the most money on the streets and in the pubs. Different tunes belong to particular streets, and each wran carries its own banner. They march wearing different colours, green and gold, crimson and white, and chequered white and blue. Each wran is led by a prancing horse with a wooden head and snapping jaws. They’re echoes of Lugh and his fiery stallions and of the Goddess, one of whose names was Epona, Mother of Mares. The horses’ cloth bodies, stretched on wooden frames, hang from the shoulders of the marchers. Behind them are jostling figures in high, pointed masks, whirling skirts and woven breastplates, made from oat straw. They march in line, beating drums and playing fifes and whistles. The golden skirts swing in time to the music as the horses whirl and caper in front of the marchers, and dart through the crowds that follow them. The traditional carved wooden heads and the straw costumes are beautiful. And slightly sinister. Under the straw masks, faces are painted in stripes, or blackened. Eyes gleam through painted eyeholes. One horse’s snapping teeth are the dentures of a dead man who used to dance in him. And weaving through the crowd are other dancers. Figures with rubber pigs’ heads, in high heels and paint-spattered boiler suits. Skeletons with padded buttocks and breasts. Wolves in wraparound Aviators. Farmers with soot-smeared faces dance past in blue wigs wreathed in tinsel. Grannies wear beards and flashing Santa hats. Onlookers scream as they’re dragged into the street and chased by the snapping horses. People stand in doorways and lean out of windows, throwing coins. As each wran swings by, through the streets and in and out of the pubs, scattered groups are left behind, laughing and taking photographs. Last year, on the streets of Dingle, I watched a dancing figure in a straw skirt and a painted paper mask. I don’t know if it was a man or a woman. The feet were in heavy boots and the hands wore outsize gardening gloves. The head was crowned with horns. The dance was a little, circular, shuffling jig. Three steps forward, two back and then three steps forward. Then the dancer whirled round,and the circle began again. And from behind me, I heard a bellow of answering voices. ‘Fair play to you! Keep at it! We never died a winter yet!’

Extracted from The House on an Irish Hillside, Chapter 12 'Dancing Through Darkness'.

November 11, 2020

FROM IRISH LOCKDOWN TO TRANSATLANTIC LAUNCH PARTY

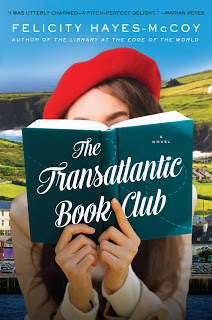

Yesterday was The Transatlantic Book Club's US and Canadian publication day, the launch of the fourth Finfarran novel published there by HarperPerennial.

Normally I'd have been dressing up and setting off for a celebratory party with hugs and kisses and glasses of wine and much posing for photographs and signing of readers' copies. But this is 2020 and I'm in Ireland, where right now we're all living in lockdown, unable even to visit family members and confined to a radius of 5 measly kilometers from our homes. I'm also at the very end of the Dingle Peninsula, so - while a 5 kilometer radius offers some of Ireland's most glorious mountains and long, deserted beaches - it's not exactly thronging with cheering Finfarran fans. So I'd resigned myself to a phone conversation or two, emails from my agents and publisher and a bit of tweeting. Which would have been fine. But instead - because I have the best and kindest readers in the world - I had a brilliant celebratory event that kept me up until past two in the morning and from which I'm still recovering as I type this.

The Transatlantic Book Club is about Cassie, a girl from Canada, who visits her recently widowed Irish granny and, to cheer her up, persuades the local librarian to start an online book club. The club links my fictional rural community in Ireland with an equally fictional one in upstate New York, where Cassie's gran spent a summer when she was young. And last night, to my delight, I clicked on a link in an email and took part in a real transatlantic book club discussion which transformed itself into one of the most enjoyable launch parties I've ever had.

There we were, me and the member of the KCBookClub, linking Kansas to the end of the Dingle Peninsula. They were all wearing hats as a hat-tip to the book's charming cover (see what they did there?). We made friends, talked Finfarran, shared this strange year's stories of isolation, courage, hope and humanity. It was past midnight by my time and my broadband connection was dodgy due to the wild Atlantic gale that was blowing outside. But I could have stayed up forever. The broadband held, I had the fire lit and it felt as if I was welcoming every one of them into my home here in Ireland, with the added bonus of being able to join them in theirs.

There was wine, tea, and egg nog with Irish whiskey. The was so much warmth and humour and such a sense of celebration ...

... and I realised that, on both sides of the Atlantic, people are finding that reading books and keeping in touch on the internet are wonderful ways of helping each other to get through this weird time.

Click here to buy your copy of The Transatlantic Bookclub

May 25, 2020

The Rythms of Life in Lockdown London

Last September our TV signal went down. We’d just travelled from Ireland to London, where settling into our two room flat normally takes five minutes. Boiler on, yep we’ve got hot water. Fingers crossed, deep breath, phew, the broadband’s still working. Stick a pizza in the oven and watch an episode of Taskmaster. Totally normal. But that night, we had a crisis. An ominous blank, black TV screen.

I should explain that our two rooms are in an inner-city block, part of a former jam factory with an eighty- foot, redbrick chimney that says HARTLEY in huge white tiles. In Ireland, our stone house - two rooms again, plus a dodgy back kitchen - is up the side of a mountain in the West Kerry Gaeltacht. It has a compost bin, ridges for growing spuds in the front garden and apple trees, fuchsia hedges and gooseberry bushes round the back.

Anyway, there we were in London with no TV signal and, since I’m talking Freeview, with no chance of finding a human being to set us right. So my husband spent an hour cursing his way round the Freeview website until, several screens beyond the FAQ one, he discovered the entire system had been shut down and reconfigured while we were away. Eventually, when the pizza was cold and we’d nearly murdered each other, we got it working again. Except for one thing. The clock was set wrong. Now, as everyone knows, there are two things you can do in this situation. One is to go back online, find a ‘solution’, and take the risk of screwing things up again. The other is to put up with it and wait. Because, you know that the passage of time will bring a temporary solution, and that, in the interim, a better one might emerge.

I’m writing this in lockdown in our two rooms in London, living through a different kind of crisis. I know we’re lucky. We’re well, we work from home and (touch wood) the boiler, broadband and TV are fine, But my mind is over in Ireland where, at this time of year, I’d normally be walking Atlantic beaches, visiting neighbours, earthing-up spuds, or just sitting in the garden, writing my next novel.

When we first began to till that garden nearly twenty years ago, our neighbour, Jack, came and introduced himself. He enquired our names, told us his, and we stood at the gate talking. He had two dogs then, Sailor and Spot, and a cat who could open doors and ate cabbage. Next day, when we walked down the hill, he invited us in and we sat at his kitchen table. The cat lay on Spot’s back and Spot lay on the floor. As we drank tea, I looked out through the door at three red hens pecking watercress by a stream. Later that week Jack came to help us make the ridges. He had a long-handled spade, perfectly balanced for this work he’d done each year of his life since he was a boy. He moved backwards in an unbroken rhythm, breathing to the swing of the spade and turning the heavy, oblong sods with a twist of the handle. A robin darted out of the hedge and joined him, stabbing at snails in the freshly-turned earth. Beak and blade moved steadily across the garden in counterpoint. It was like watching music.

I’m remembering that today in lockdown London. No ridges were made this year in our garden over in Ireland, and the robin is darting about among uncut grass. Scarlet and orange nasturtiums will be creeping towards the front step, and scrambling over the compost bin. No neighbours will stop at the gate for a chat.

Here at the jam factory we haven’t a garden, and the one walk we’re allowed each day takes us down eerily empty city streets. And it feels weird. I’ve written a novel called The Heart of Summer about a woman who flies off on a life-changing holiday, yet, right now, my own life is on hold. Like every other author with a book about to be published, I feel frozen. My signings, talks and library events have been cancelled. I’ve seen my book on a screen but haven’t yet held it in my hand. Nothing is normal.

But we’re growing radishes. Three frail, green shoots have emerged from a seed pot we got for free at a supermarket, after queuing two metres apart to buy a plastic bag of spuds. Right now it feels as if the clocks will always be wrong, that we’ll never get back to the life we knew, that we’re all holding our breath for fear of some new crisis. Sometimes, not knowing what will happen next feels like the worst part of all. But not knowing what will happen next is the heart of the human condition, and I do know one thing when I look at my gallant, green radishes. The earth is still turning and, all across it, the rhythm of the seasons still goes on.Visit my Author Page on Facebook

A version of this piece appeared in the Irish Mail's You Magazine May 2020

March 28, 2020

It's Perfectly Okay Not To Be Shakespeare

Here's one of my occasional writing tips. I hope those of you who aren't writers will find it helpful too.

As more and more people are required to stay at home, for the sake of our own health and others', we're increasingly being exhorted to take this time to be creative. "Write a diary!", people say; or "here's your chance to start that novel"; or "why not take up a new hobby?; or "Shakespeare used downtime during the plague to write King Lear, you know!"

Well, yes, that was what Shakespeare did, but a/ he was a brilliant, professional playwright and b/ he and his contemporaries were accustomed to the frequent, localised, bouts of plague that disrupted their lives and work and closed London's theatres. Most of us are neither of those things so, personally, I'd forget about using Shakespeare as a role model.

Instead, I'd suggest this. In these unprecedented times, many of us may be helped by writing down thoughts or recording experiences, but noone should feel any pressure to do so. Not everyone is creative, assuming "creative" means designing or making things. And even naturally "creative" people may find that, right now, setting ourselves tasks and projects isn't helpful.

Every single one of us is feeling scared an apprehensive. If turning to writing - or painting, or embroidery - helps us feel better, that's a good thing. But it won't make you feel better if it becomes a new source of stress.

In circumstances beyond our control, we tend to focus on anything that gives us a sense of empowerment. Structuring your day with projects can mitigate feelings of helplessness. But, sometimes, self-imposed tasks can make matters worse, especially if we find ourselves "failing" at them. Please believe me when I say that failure doesn't come into it. It's fine to write if and when you want to. It's equally fine not to write (or paint, or sew, or declutter your house, or catalogue all your photographs) if that's not what you feel like doing. And it's important to remain flexible and to know that your feelings may change - even from hour to hour - and that that's okay too.

Incidentally, for writers like me, still working to deadlines, the same tip applies. I haven't been getting my full day's quota of words written lately, which is absolutely fine because I know I need to adapt to my new circumstances. And - here's the thing - in adapting, I've remembered something that stress might well have led me to forget ...

... stillness and awareness are important elements of the creative process, and I know they'll get me back on track with the day job. They're also healing and empowering. Try sitting still and watching the patterns made by sunlight falling through wind-blown branches. Look at a flower or an object and take delight in counting its colours. Close your eyes and be aware of simply breathing in and out. Make no demands on yourself and be kind to others.

Kindness itself is a form of creativity, and it flourishes best when it's alowed to flow gently into our lives.

June 17, 2019

Are you sure you're Editing?

You know how, when you’re writing something, you go over it time and again, re-reading, changing and cutting it? Some people love this process and find it energising. Others get confused feel it’s a kind of required self-censorship which drags flights of fancy down to earth.

“Editing” and “doing an edit” are terms sometimes used for this process, in writers’ groups, masterclasses and on social media. But, in my view, choosing a different term might be helpful.

First things first.

The primary definition of “edit” is “to prepare written material for publication”. Secondary definitions are “be editor of (a newspaper or magazine) – eg ‘he edited the New Yorker’”, and, as a noun, “a change or correction made as a result of editing – eg ‘the edits required considerable time’.”

So, here are some thoughts.

1/ Unless you’re certain that what you’re writing WILL BE and IS READY TO BE, published, it’s actually not appropriate to think about “editing” it.

2/ Unless you’re in charge of running a newspaper or magazine, you’re not an editor – and therefore shouldn’t be “editing”.

3/ Unless your work is at the editing stage (ie written to your own satisfaction) you shouldn’t be dealing with “edits” at all.

What you should be doing is writing.

Of course there’s an overlap between an editor’s work and a writer’s. Both tasks involve elements of what another dictionary definition of “edit” defines as “correcting, condensing, or otherwise modifying” text.

But what’s important is to remind yourself that, as a writer, you’re correcting, condensing, or otherwise modifying all the time.

That’s what writing consists of. You think of something and attempt to express it in words, which you write down. Then you read what you’ve written and fiddle about to find ways of expressing it better. This isn’t about constraining what you’ve written (or, more importantly, what you want to say). It's about exploring, crafting and releasing it.

Of course, if you’re happy to use the word “edit” for this part of the writing process, that’s fine. But if it ever feels like self-censoring, rather than releasing, please stop using it. Tell yourself, and everyone else, not that you’re editing but that you’re writing.

And then work away, correcting, condensing and modifying, till you’ve found what you want to say, and you’ve said it to your own satisfaction.

Visit my Facebook Author Page

April 20, 2019

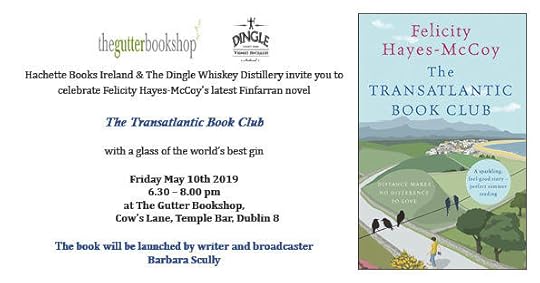

YOU'RE ALL INVITED TO A BOOK LAUNCH

My Irish publishers Hachette are bringing out my fifth Finfarran novel on May 2nd and the Gutter Bookshop in Dublin is hosting its launch, with drinks provided by my lovely West Kerry neighbours, The Dingle Whiskey Distillery. So here's an invitation to join the celebration. Do, please, come along if you're in Dublin on May10th.

Writing the Finfarran novels is always a joy but this one is special because its plot came about by sheer happenstance.

A few years ago, in a gift shop, I picked up a birthday card with the caption ‘My book club can beat up your book club'. A lady beside me had spotted it too and we got chatting. The card had caught her eye, she said, because she was a member of "Ireland’s only Skype book club", hosted by her rural local library and a public library in Peoria, Illinois, USA.

Months later, when I was chatting to my agent about possible plots for the next Finfarran novel, it struck me that a book club based in two countries might make a good story line. My agent and my editor loved the idea - as did my publisher over in the US - so I sat down to write in the knowledge that they were as excited about it as I was.

Then, with a sickening thud, I realised that I hadn’t a clue how a Skype book club worked. Was it a kind of conference call and, if so, why would the members get together physically? Wouldn't they just log in from their home computers? I couldn’t begin plotting until I’d properly grasped the logistics, which meant that I needed to get in touch with the library the lady had mentioned. But to my shame, I’d forgotten both her name and the town she’d said she was from.

So I took a tea break and walked around the house, afraid I'd have to tell everyone that I'd need to rethink the storyline. But then I was inspired to log onto Twitter and tweet

#Irish #Librarians Help! What local library hosts a transatlantic book club?

Twenty minutes later Twitter delivered. I had responses from two different Irish libraries, putting me on to Marie, a librarian in Co. Tipperary. So I called Marie and, once again, was blessed by happenstance. The next of the club’s quarterly meetings was scheduled for the following week and I was invited to come and join in. So a week later I was on my way to visit Ireland's only Skype book club, which has quietly been flourishing for to past eleven years.

It was wonderful and felt completely surreal. The lady I’d met in Dingle, was there to greet me, and we chatted while the Tipperary group gathered and Skype contact was established on a laptop linked to a screen on the wall. Then, suddenly, the screen sprang to life and there was the group in Illinois, sitting on rows of chairs, just as we were in Ireland. Immediately, the logistics became obvious. There was a facilitator on either side of the ocean, and everyone was accustomed to raising their hands before making a comment, and to facing their camera and microphone when they spoke. (Turning round to respond to a comment meant strained faces on the opposite side of the Atlantic, where people could neither see your face nor hear what you wanted to say.)

The club’s choice for the session was Sebastian Barry’s Days Without End. It was remarkable to see and hear the different takes and ideas bouncing back and forth across the ocean and, by the end of the session, it was evident that everyone would be going home with a new, communal sense of what they’d read as individuals.

I’d known before setting out that day that my fictional book club would read a classic detective story, and I’d planned how my various story strands could come together via that device. Before returning home to begin writing, I fixed on the title The Transatlantic Book Club, and got the real Skype book club's permission to dedicate it to their members. I've since heard from Marie, the Tipperary librarian, that, when it's out on both sides of the Atlantic, they plan to discuss it at one of their club meetings. And, wonderfully, they've invited me to come and join in.

Meanwhile, Marie will be among the guests raising a glass in The Gutter Bookshop in Dublin on Friday May 10th. I hope you'll be able to join us. If you do, come up and say hi and tell me you heard about it here.

And if you can't make it to the Dublin launch, I hope you'll enjoy reading The Transatlantic Book Club.There's a special pre-publication price on the Kindle edition now!

January 6, 2019

Mighty Women: Nollaig na mBan in Ireland

Nollaig na mBan means ‘Women’s Christmas.’ The last of the twelve days of the Christmas season, it’s celebrated on 6 January, when the men take over the household duties and women of all ages get together and party. They meet at home, or go out in groups, to eat, sing, drink, dance and generally hang out together. The village pubs and restaurants are full all night, and the dancing often spills onto the street. Grannies and aunties dance with little girls, friends get up and sing songs together, and houses are full of music. Nollaig na mBan used to be celebrated all over Ireland, and in lots of places it still is. It’s a meeting of generations and a time for sharing.

I remember the first time I joined a table of women in a candlelit pub in Ballyferriter for Nollaig na mBan. The singing had already begun. The barman was carrying trays of drinks and platters of food from the kitchen. A couple of older women, in seats closest to the fire, were keeping an eye on a group of little girls, dressed in their best, who were already jigging to the music. It was a cheerful, welcoming night of shared talk and laughter. And when the dancing started, it was the oldest women who were first onto the floor.

I can’t remember if that was the first time I saw Cáit dancing, but I’ve seen her many times since. I’ve even seen her dance to the music of the organ as she walks out of a church. The first money she ever earned she spent on a bicycle, so she could cycle to the dancehalls. Cáit grew up at a time when the grip of the Roman Catholic Church on the community was rigid here, and priests often broke in on dances with threats of hellfire. “They’d come into Muiríoch Hall and they’d scatter the dancers. They’d drive us out the back and through the river!” “They would! And they’d break into the houses cursing us.” “He’d be reading out of his book.” “He’d be in one door and we’d all be out the other!”

The women laugh now when they remember it, but at the time it must have been frightening. The priests tried to ban music and dancing at the crossroads too, and at the patterns by the holy wells. Mostly they succeeded, and for most of the twentieth century the Irish state was dominated by the Church’s ideal of celibacy, so authorities’ attitudes towards sexuality, and towards women, became more and more warped. Yet nothing stopped the dancing in Corca Dhuibhne. Jack’s sister Nóirín can remember girls cycling through the dark to the dancehalls with high heels hanging round their neck. I’ve heard that same story from almost every woman of her generation.

Ireland rears powerful women. I have neighbours who grew up without electricity or running water, on isolated farms, doing back-breaking work. They led lives that would exhaust the average woman today. They looked after families, milked cows, made butter, cared for calves, raised poultry and baked their bread in iron pots at the side of an open fire. As children, they walked barefoot to school. As adults they often worked barefoot too, and helped the men in the fields. I once asked a neighbour how a woman coped if a man was hurt and couldn’t work. She told me she got up sooner and went to bed later. ‘Whoever did it, the work still had to be done.’

And beneath a compliant surface, women hereabouts never lost a sense of their own identities. Cáit’s generation grew up with the tradition of arranged marriages. Some friend or relation would act as matchmaker, and couples might spend very little time together before their wedding. But traditionally, a girl could send an offer to a man just as easily as a man could send one to a woman and if a man married into a woman’s people’s land, he was expected to bring a dowry. Cáit sent an offer to the man she married. “I chose my husband. I said no one else would satisfy me, and if I didn’t get him, I’d go to America.” She sent him a message by her aunt. He was twelve years older than Cáit, and had ‘two left feet’ on the dance floor. But “he was kind and good humoured, and he was good company.” They had a long and happy marriage and, even when he was dead and gone and she faced old age without him, it needed no more than two bars of a tune to get Cait up dancing.

Text extracted from my memoir The House on an Irish Hillside

Visit my Author Page on Facebook

December 26, 2018

The Wran's Day on the Dingle Peninsula

The Wran, or Wren's, Day is celebrated on 26 December, just after the winter solstice. It’s as much a part of the holiday season here on the Dingle Peninsula as Christmas Day itself. If you study folklore or anthropology, you learn that it belongs to a tradition that stretches back to the first people who came here, thousands of years before Christianity. Its name is a corruption of the English word ‘wren’, and in Irish it’s Lá an Dreoilín (which is pronounced something like “Law Un Dro-leen”.)

There’s endless research on the Wran’s Day, and suggestions that dreoilín, the word for wren, comes from ‘draoi-éan’, ‘druid’s bird’. It’s linked to ancient midwinter festivals and shamanism, when a shared web of ideas and information was accessed like a form of internet powered by human energy, and to later folk traditions like Straw Boys and Guisers. Its rituals belong to a dream state beyond stories, or even words, when there were just images and rhythms.

But if you turn up in Dingle on 26 December, what you’ll see is one big party. Basically, the town gets taken over by musicians and dancers. In the past, the boys back west used to dress up in rags and old coats turned inside out. They’d smear soot on their faces, or wear masks, and go from house to house, playing music and asking for pennies ‘to bury the wran’. Then they’d use the money to buy food and drink and throw a dance. Earlier still, live wrens used to be hunted and killed and carried in procession. Earlier than that, at huge ritual gatherings, kings offered themselves to be killed at the turn of the year, in an extreme version of sacrificing the best you’ve got in times of scarcity to invoke future fertility.

Through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Church did its best to suppress the Wran’s Day. But it never succeeded and the ancient, wordless rhythms are still felt here every year.

Some kids still walk the roads in costumes back west, and turn up at their neighbours’ houses to dance in the kitchen. Each separate group is called a ‘wran’. You hear the creak of the gate and the rattle of a drum outside the window. Then tattered figures with masked and painted faces crowd into the house, disguised in their grannys’ aprons padded with rolled-up socks; or their dads’ pyjamas, tied with rope and stuffed into wellingtons. As they enter the room, accordion players pull their masks down over their faces and whistle players push them onto their foreheads; the smaller figures giggle and shuffle. Then someone gives a note and the little group breaks into a jig or a polka.

But, these days, most people head for Dingle instead and join the rival parades that march and dance through the streets playing music. Máire Begley blames it on the carpets. “The real Wran went out the door the day the carpets came into the houses. No one wants mud on the floors nowadays. That’s why they all go in to Dingle!”

The Wran’s Day in Dingle town is famous. Nowadays the collections are for charities, and the wrans compete to see who can raise the most money on the streets and in the pubs. Different tunes belong to particular streets, and each wran carries its own banner.

They march wearing different colours, green and gold, white and green, crimson and white, and chequered white and blue.

Each is led by a swordsman and prancing horse with snapping jaws, echoes of Lugh and his fiery stallions, and of the Good Goddess, one of whose names was Epona, Mother of Mares. The horses’ cloth bodies, stretched on wooden frames, hang from the shoulders of the marchers.

Behind them are jostling figures in high, pointed masks, whirling skirts and woven breastplates, made from oat straw. They march in line, beating drums and playing fifes and whistles. The golden skirts swing in time to the music as the horses whirl and caper in front of the marchers, and dart through the crowds that follow them. The traditional carved horses' heads and the straw costumes are beautiful. And slightly sinister.

Behind them are jostling figures in high, pointed masks, whirling skirts and woven breastplates, made from oat straw. They march in line, beating drums and playing fifes and whistles. The golden skirts swing in time to the music as the horses whirl and caper in front of the marchers, and dart through the crowds that follow them. The traditional carved horses' heads and the straw costumes are beautiful. And slightly sinister. The modern costumes echo and express the ritual's ancient roots. Under the straw masks, faces are painted in stripes, or blackened. Eyes gleam through painted eye holes. One horse’s snapping teeth are the dentures of a dead man who used to dance in him.

The modern costumes echo and express the ritual's ancient roots. Under the straw masks, faces are painted in stripes, or blackened. Eyes gleam through painted eye holes. One horse’s snapping teeth are the dentures of a dead man who used to dance in him.And weaving through the crowd are other dancers. Figures with rubber pigs’ heads, in high heels and paint-spattered boiler suits. Skeletons with padded buttocks and breasts. Wolves in wraparound Aviators. Farmers with soot-smeared faces dance past in blue wigs wreathed in tinsel. Grannies wear beards and flashing Santa hats. Onlookers scream as they’re dragged into the street and chased by the snapping horses.

People stand in doorways and lean out of windows, throwing coins. As each wran swings by, through the streets and in and out of the pubs, scattered groups are left behind, laughing and taking photographs.

And the wran boys' shouts echo down through the streets " We never died a winter yet!"

All photos (c. copyright fhayes-mccoy) taken in Dingle town Dec 26th 2018 Text extracted from my memoir The House on an Irish Hillside

Visit my Author Page on Facebook

August 28, 2018

The Secret of How to Start Writing

"The secret of getting ahead is getting started."

This quote, variously attributed to Mark Twain, Agatha Christie and Anon,often appears as Number #1 in lists of Top Writers' Tips. It's true, of course, but for many of us it simply isn't helpful. Because getting started can be difficult, and emphasising what's difficult isn't always the the best way to get ahead.

When I was at drama school, I learned a wonderful lesson from a voice teacher. Don't try hard, try soft. Trying hard implies tension. You grit your teeth and square up to a challenge. You stick out your jaw and clench your fists and tell yourself that nothing and no one will keep you from reaching your goal. Trying hard may get your adrenaline flowing but, equally, it can impede your creative flow.

As always, different things work for different writers. Some people find that sitting down and requiring oneself to write is the best way to begin. For others, that just isn't helpful - so much energy is channeled into 'discipline' that there's none left for getting in touch with what you have to say.

So here are four ways to begin by trying soft:

1/ Don't set yourself a regimen: write at different times of day and in different places.

2/ Forget about word count: use pages of different sizes on different occasions, so you're less conscious of how much you've written in any one session.

3/ Allow yourself displacement activity: sometimes going for a walk or doing the ironing is the gentlest way of allowing your mind to gather the thoughts and ideas about which you want to write.

4/ Imagine your way through a paragraph, shaping the sentences in your mind and speaking them aloud till you have too many to remember, and you find yourself longing to write them down.

And if you find that you can't begin to write no matter how soft or hard you try, be kind to yourself. Remember that if you don't live, you'll have nothing to write about. So give yourself a break. Literally. Time spent panicking in front of a blank screen or an empty page is time wasted. Get up and live instead.

Visit my Author Page on Facebook

August 7, 2018

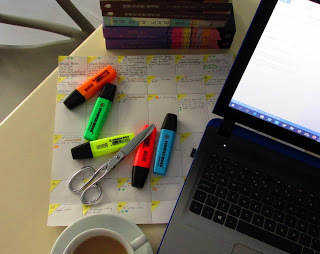

Plotting the Finfarran Novels

Years ago, when I was writing for tv drama series, I learned to carry a very small notebook indeed. This was back in the days before notebooks were digital, when writers still suffered from stationary-envy and every meeting began with covert glances at other people’s desirable A4 Filolfaxes. Actually, back in those days, large-format notebooks had much to do with power games. The subliminal message of a really big leather-bound tome and a flashy Parker pen was that your agent had bumped up your fee for the series, or that your last show had just been sold as a franchise in the US.

My own titchy little notebooks had nothing to do with poverty, or even reverse psychology. They were a cunning way of controlling an impulse to express my emerging ideas in diagrams rather than words.

At development meetings attended by a producer and several other, highly articulate, writers, bits of paper covered with arrows and interlocking circles weren’t approved of. Hence the voluntary strait-jacket of a notebook so small that it fitted into the pocket of my jeans. But now, sitting at home in my PJs, preparing to start on a novel, I can indulge in what, to me, is a vital part of plotting a work.

Visuals are particularly useful if you’re working on a series of novels. With the Finfarran books I began by sketching a map of a fictional peninsula before creating my characters, some of whom were peripheral in the first book, led by my librarian protagonist, Hanna Casey. Working from the map, I located each in terms of where they lived and/or worked: and knowing where they came from in this literal sense fed into their development. Hitherto shadowy characters often come forward in subsequent books, so I still review the map whenever I’m planning the next book. But, as each novel stands alone as well as being part of the series, each has its own chart.

Beginning with a draft in a squared copy book and moving on to a wall chart, drawn up on A3 paper, I can plot the shape and flow of a book in purely visual terms. The starting point is my 90k word count. Rounding it up to 100k, to make the maths easier, I divide it into chapters of a notional two and a half thousand words. Then, using a pencil and a ruler, I allot a box to each chapter, and number them.

The narrative thrust of the Finfarran novels has so far been largely carried through internal monologues, and dialogue. This contributes to the readers’ sense of involvement in, and being part of, a fictional community. In structuring, I generally attribute a chapter to each of the principal characters and, by mapping these across the chart, ensure the characters’ presence is evenly balanced across the book.

Then, having established A, Band C story arcs which will span the entire novel, I plot them across the chart, indicating where they’ll begin and end. Each story arc will belong to one or two principal characters or families. The A story - which in The Library at the Edge of the World and Summer at the Garden Café was Hanna Casey and her family’s, and in The Mistletoe Matchmaker was Cassie Fitzgerald’s - will span the whole book from Chapter One. The B and C stories will begin later and end somewhere in the last few chapters, with Bcontinuing longest. Both of these are always wrapped up before the final dénouement.

Each character has a colour, indicated on the chart with a hi-viz sticky dot, square or triangle. The beats in each storyline are indicated by symbols. Then the passage of fictional time across the book is marked – weeks or months, for example; or seasons when the landscape will change; or the occurrence of calendar-related events like Easter or Ramadan. And there are other specifics: for example, in The Month of Borrowed Dreams, the latest in the series, I also needed to indicate each character's process in reading the book my fictional library film club was discussing.

Though the initial process might seem prescriptive, in practice the way I use the chart is fluid. It hangs by my desk and, to begin with, tends to be fairly neat. Over the months of writing, it gets increasingly messy, with the chapter boxes filling up with notes and scribbled memos, and arrows and crossings-out indicating changes of mind. The coloured character dots are sticky because I often find I need to move them. In writing the story, certain characters take over, jostling others out of their place in my scheme: but by moving the dots I can see at a glance if the book has lost its rhythm, which can happen if particular voices are present or absent too long.

Sometimes the evolving storylines require structural changes. In Summer at the Garden Café , for example, my editor pointed out that it was Jazz, not Hanna, who really had the A story and, to make this work, I introduced Jazz earlier in the book. This involved moving chapters which, on the chart, had appeared later – which, inevitably, meant other adjustments too. But with the chart at my elbow, I could see at a glance not just how I’d affected the narrative but what the knock-on effect would be on three interwoven storylines, each of which exposed and advanced the book’s underlying themes.

Themes and characters’ personal relationships can’t be contained in squares or circles, or held in place with arrows. They emerge from the writer’s unconscious in the telling of a story, with the same thrill of discovery that drives an author to write and compels a reader to read. For that to happen, I find I need a safe space for freefall. And before taking that leap, I need to create a reliable structure - firm enough to act as a template but supple enough to bend in the creative process without breaking.

Maybe that’s why I created a protagonist whose dream was to work in an art library, and whose first experience of books arose from a love of colour and shape.

A version of this piece first appeared on the Irish writers' website Writing.ie

Come and say Hi on my official Facebook Page