Felicity Hayes-McCoy's Blog, page 7

March 12, 2013

The Next Big Thing

Last week I was surprised and delighted to be tagged by the poet Aine Macaodha in a Blog Hop called 'THE NEXT BIG THING' in which writers answer ten questions on their work in progress and tag other writers to do the same.

(Image © National Museum of Ireland)

(Image © National Museum of Ireland)When I'm sailing uncharted waters my mind's mostly on feeling the current, so I tend to be fairly useless when it comes to talking about work that's unfinished. But Aine's invitation arrived when the draft of my next book was already off my desk and with my agent. That means that although it's still a work in progress I do have some degree of separation from it. So here are my responses to the ten questions.

1) What is the title of your next book?

Currently it's called The Songs Within Birdsong - titles often change before publication, though.

2) Where did the idea come from for the book?

I've been exploring its themes all my life. The immediate impulse came from the social and physical dynamics of the area of inner London where I live when I'm not in Corca Dhuibhne. One central part of the plot arose from a conversation with my literary agent, Gaia Banks, who, as well as being an agent, is a born editor and creative facilitator.

3) What genre does your book fall under?

It's a novel.

4) What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

When it comes to movies everyone wants a name attached, to secure funding. Yet at the same time you long for a producer and director with the courage and imagination to think actor first and funding second. Since one of my protagonists is an adolescent there'd probably be a decent chance of that with this book. And since the other principle character is Central European and in her eighties there are wonderful choices to be made. (Many of whom are names, actually - look at the casting for Hoffman's Quartet.) (Looks. Drools. Pulls herself together.) Casting's a funny thing, anyway. Sometimes you set your heart on an actor, get someone else and find yourself unable to conceive of a better performance than the one you end up with.

5) What is a one sentence synopsis of your book?

Can't really answer that. I don't write to say something so much as to find out what it is I have to say. One sentence synopses can't be produced till a work's completely finished. Besides, I'm never sure the author's the right person to come up with them.

6) Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

My initial job's done once I deliver a draft that I'm happy with to Gaia and she's happy too. Then I drink tea, walk beaches and get on with the next thing till we get an offer from a publisher.

7) How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

My first drafts usually take a few months. Sometimes, as with this one, there are long breaks in the process. While writing my last book, which is a memoir, I realised that the oral, Irish language, tradition of storytelling has had as much influence on my work as the literary, English language tradition. That, combined with the fact that I've been a scriptwriter and playwright for most of my career, means I tend to see, hear and work on things in my head before I write them down.

(There's a story about someone asking the Regency playwright Richard Sheridan if he'd completed a play he was working on. 'Yes,' he said, 'all that remains now is to write it.')

8) What other books would you compare yours to?

That's another thing I'm not sure authors should do.

9) Who or what inspired you to write this book?.

The starting point was Kindertotenlieder, a song-cycle by Gustav Mahler. The first title for the book was Dead Children Songs, which is a direct translation of Mahler's title.

10) What else about the book might pique the reader’s interest?

Can't speak for my readers but the songs within birdsong concept delights and fascinates me because it exposes how much happens beyond human awareness. The heart of the book is the relationship between an adolescent and her grandmother.

This is how it opens:-

'Birds speak in myriad fragments and complex patterns beyond our awareness. The stories of their lives reach us in disconnected snatches. In an egg a bundle of cells is suspended in liquid. Time brings a bird with the message of its cells imprinted in its voice. It speaks of danger, fear, hunger, aggression and desire. We hear songs.

The detail is lost. Digitally recorded birdsong, slowed down but played at pitch, reveals sounds within sounds, like painted Easter eggs one inside another. We now know that birds sing too fast for human ears.

Analysts have linked the speed of birds’ communication to the relative shortness of their lifespan. Humans, who live longer, have more time. But what we have to tell can also be lost. Sometimes because it’s too hard to bear.'

So that's it. Thanks for thinking of me, Aine. And, by the way, as I've been typing this I've had an email from Gaia saying she loves the draft.

So .....

.... onwards and upwards.

.... onwards and upwards.Next week on THE NEXT BIG THING are two writers whose work I admire, one of whom I met recently, having read her blog, and one I've known and worked with in broadcast for many years. Many thanks to them both for accepting my invitation to blog hop.

Emily Benet

Emily Benet is a writer based in London. Her debut book, Shop Girl Diaries, began as a weekly blog about working in her mum’s unusual chandelier shop. Her blog was the winner of the CompletelyNovel Author Blog Awards at the London Book Fair 2010. She has written about the benefits of Social Media for writers in Publishing Talk, Mslexia and The New Writer and runs Blogging for Beginners and Improvers workshops. She is currently editing a romantic comedy called Spray Painted Bananas which she serialised on Wattpad. She blogs at www.emilybenet.blogspot.com

Michael Bartlett

As well as being a professional writer and a producer with a long and distinguished career in broadcasting, Michael Bartlett is a partner in Crimson Cats, a UK based audio book publishing company specialising in producing and publishing unusual and quirky audio books, mostly material which does not exist elsewhere in audio. From 1975 to the end of 1982 he worked for BBC Radio Drama, initially as a producer, then as Editor of Afternoon Theatre on Radio 4. Before that he worked as a Director in Children's Television, a reader in the Television Script Unit and a producer in Schools Radio. He blogs at http://www.crimsoncats.co.uk/

And do check out Aine's work too.http://aine-macaodha.blogspot.co.uk/ http://ainemacaodha.webs.com/index.htm

Published on March 12, 2013 15:12

March 8, 2013

Thinking about mothers on International Women's Day

This week, intoxicated by the sense of spring in the air, I tweeted this photo of primroses. I love spring. I love its sense of expectation and anticipation, the gleam of celandines among green leaves and the way that primroses unfurl on the roadside ditches behind the dead, curling tendrils of last year's briars.

When I was a child my favourite season was autumn. Spring was my mother's. I asked her why once and she told me that she loved its quiet promise of renewal and growth. I'd forgotten that conversation when I tweeted the photo. But the response to my tweet brought it back to me. Because so many of the replies I got were about mothers.

Here's a typical example: -

'Lovely - not out here yet - always remember being little girl picking them for Mam.' It's touching and fascinating to see how many women share the same memories of their mothers. But the response that touched me most was a series of Direct messages from a man. I've never met him and he'd never contacted me before.

Here's what he said:-

'Hi felicity that was the first image I saw of the primrose this year its a good sign. Immediately thought of my mother ... She was a national school teacher all her life died 2008. On my birthcert it says she's a housewife as she was forced to quit her job 58 irl ... I think its terrible she was a writer poet musician storyteller historian homemaker choirmistress educator mother a woman's woman.... '

He went on to describe his own work as a creative artist, how he's recently felt frustrated, excited and full of anticipation as a current project nears completion. His message ended with renewed commitment to getting his work done.

Reading what he wrote I was moved to tears. In 1940s Ireland my own mother had to quit a job she loved when she married and became a housewife. She too was a woman's woman, a thinker who'd wanted to become a journalist, and a storyteller who'd dreamed of being a playwright. She had a happy marriage and raised five children. She believed, as I do, in the value of a housewife's skills. But she never fulfilled those personal dreams.

Looking back, I know that the love of spring and its promise of renewal was one of her many gifts to me, one that I need to grow into and didn't really recognise until long after she was dead.

Looking back, I know that the love of spring and its promise of renewal was one of her many gifts to me, one that I need to grow into and didn't really recognise until long after she was dead. I know too that without her quiet, dogged support I'd never have become a writer. So on International Women's Day I thought I'd write this.

Visit The House on an Irish Hillside on Facebook

Published on March 08, 2013 03:21

February 19, 2013

Circles, spirals, links and layers.

Last weekend, at the end of Ireland's Dingle peninsula, singers, musicians, students, teachers and locals, all gathered in Ballyferriter, a little village that gets taken over each spring by a dynamic school and festival of traditional Irish music.

Every year each available room in the village gets colonised - in the school, the pubs, the café, shops and the local museum. There are classes on a multitude of instruments, including the harp, fiddle, accordion, bodhrán, banjo and mandolin, pipes, flute, mouth organ and concertina. There’s set dancing and step dancing. And then, at night, there are concerts with lineups of traditional musicians that bring audiences from Europe and America as well as from all over Ireland.

As long as I’ve been coming to Corca Dhuibhne I’ve heard discussions about how changing customs are changing the way that traditional music’s shared. Now, when everything’s globally accessible and often shared through video and sound files, individual styles belonging to particular places can easily be lost. That's one reason why Niamh Ní Bhaoill and Brenndán Ó Beaglaoich, co-founders of the Ballyferriter Scoil Cheoil an Earraigh, established their Spring Music School several years ago. It’s about the genuine, native, West Kerry musical style. The emphasis is on the passing on of a living inheritance rooted in the language and landscape of the place.

Yet the same global accessibility which can threaten local musical traditions brings together musicians with shared cultural roots on a wider scale, practitioners in specific styles on different instruments who revel in reaching out and finding links between Ireland's inheritance and their own.

On Saturday in Ballyferriter the Gallician piper Anxo Lorenzo led a parade through the village and into the church, the only space large enough to accomodate the whole school of musicians playing together. Wrapped up in scarves and woolly hats, facing into a chilly wind blowing off the Atlantic Ocean, drummers in hi-vis jackets and tin whistle players in fingerless gloves crowded happily along the village street behind him. Inside, in pews, gathered around pillars, and standing on the altar steps, drums, fiddles, accordians, mouth organs, concertinas, guitars, harps, flutes, singers and pipers performed individually and together.

The heart of the music was Irish. But guest performers had arrived from Estonia, Sweden and Norway as well as from Galicia and Wales. And each evening guests, locals, students and teachers played and sang together in the pubs and the hotel bar, sharing, listening and teaching across nations and generations.

Last night, thinking about the cultural links between Ireland and the other countries represented at the Scoil Cheoil, I remembered that for centuries Dingle was the main embarkation point for pilgrims setting out on the long and hazardous journey from Ireland to Galicia, to the shrine of St. Iago de Compostela .

And then I remembered something else, about the shrine itself. Once there was a bishop in Galicia whose name was Priscillian. According to legend, his Christian teaching was full of echoes of pre-Christian Celtic beliefs, in which each element in the universe was linked by shared energy.

As a result, Priscillian was accused of heresy and executed in Rome, in 385AD. After his death his disciples are said to have brought his body back to Galicia. For centuries the site of his grave was unknown. But now it's thought that an early Christian burial discovered beneath the shrine in Santiago de Compostela may be evidence that the cult of the Celtic Christian bishop was supressed by concealing Priscillian's shrine under that of the Roman St. Iago, or James.

Meanwhile, back in Ireland, the present church of St. James in Dingle's Main Street stands on the site of an early medieval one, built and dedicated in token of the generations of pilgrims who once set sail from Dingle harbour on their voyage to Santiago de Compostela.

Incidentally, that Celtic belief in a universe linked by shared energy was held in ancient Persia as well. And in medieval Europe it was expressed in the concept of the music of the spheres.

Circles, spirals, links and layers. I love them.

Visit The House on an Irish Hillside on Facebook

Published on February 19, 2013 16:13

February 7, 2013

Who Needs St. Valentine?

I have nothing at all against St. Valentine. He's a perfectly good excuse for consuming chocolate. And, given that there appear to be at least eleven possible versions of him, he's a very typical Christian saint.

Among the many legends about him is one which claims he was an early Christian priest, martyred for secretly marrying ancient Roman lovers. Another says he was a bishop who cured a pagan judge's daughter of blindess, converted the judge and baptised him, but later was stoned to death. Most of the stories make him Roman. But there's also a fairly convincing theory that both the saint and his cult of love were invented by the medieval English poet Chaucer, who also decided his feast day should be February 14th.

Typical too, are the stories about Valentine's relics. Venerated bits of him turn up all over the place, a fact that's a bit embarrassing because his complete body's supposed to be enshrined in a cathedral in Birmingham, England. Oh, and in a Carmelite church in Dublin, Ireland. The Dublin remains were deposited as a gift from Pope Gregory XVI in 1836. The Birmingham ones were a gift from Pope Pius IX in 1847. (Equally embarrassing and looks a bit like carelessness, but there you are.)

Despite all this dodginess, the presence of St. Valentine's shrine in Dublin has led to repeated attempts over the years to sell him as Ireland's Patron Saint of Love. Which, given the rival shrine in England and the unfortunate number of skulls and toes and things scattered round Europe, seems pretty daft to me. Especially as we've already got our own Irish God of Love who, let's face it, beats eleven sprurious Roman St. Valentines into a cocked, chocolate mitre.

Just listen to this:- He was a beautiful young man, with high looks, and his appearance was more beautiful than all beauty, and there were ornaments of gold on his dress; in his hand he held a silver harp with strings of red gold, and the sound of its strings was sweeter than all music under the sky; and over the harp were two birds that seemed to be playing on it. -

His name is Aengus Óg, and in Irish mythology he's the son of the great Dagda Mór and the goddess Boann, famed for his championship of lovers.

- The birds, now, that used to be with Aengus were four of his kisses that turned into birds and that used to be coming about the young men of Ireland, and crying after them. "Come, come," two of them would say, and 'I go, I go," the other two would say, and it was hard to get free of them.-

Admittedly, he doesn't do chocolate but he's ours and he's seriously sexy. I think we should dump dodgy St. Valentine and have Aengus Óg's day instead.

Visit The House on an Irish Hillside on Facebook

Published on February 07, 2013 10:15

January 3, 2013

Me and Gandalf: Not Quite There and Back Again

So, there I was this morning, staring at my computer screen having just typed the words Chapter Six, when it seemed that the sensible thing to do next was to log on toTwitter. I believe it's called displacement activity. It appears to happen when I'm working on a novel.

Normally I scroll down the latest tweets, admiring other people's input, wondering if I should come up with something myself, and knowing I'd be far better employed getting back to my deadline. But today I found myself catapulted straight back to one of the most exciting days of my life.

The day I heard that my father knew Gandalf.

I was probably six or seven. My father was a professor at University College Galway in Ireland - since renamed NUI Galway. He'd recently given me a copy of The Hobbit and I'd loved it. It was the first book I'd read which echoed the folktales I'd been told by my Galway granny, yet had a distinctly different flavour. And it was the beginning of my awareness of, and delight in, the similarities and contrasts between stories from different traditions. And between literary and oral storytelling. Not that I knew that at the time. I just loved the fact that my Granny's stories and the book I'd been given by my father were what I called 'the same only different.'

Then, about the time I was finishing The Hobbit, I overheard my father and mother chatting. And one name, casually mentioned, leapt out of their conversation. Daddy had a meeting with Tolkien. It seemed so unlikely that I said nothing. Then I edged over to my father's chair and stood staring at him. Eventually he looked down and I heard myself asking if he'd take me to his meeting. He was baffled. But a lot of the things I said in those days baffled my parents, so he just laughed and pulled my hair.

Next day I watched him pack his bags and set off to take the train from our home in Dublin to the university in Galway. I was absolutely certain that in a few hours time he'd be hanging out with a wizard. Possibly Smaug and the dwarves as well, but they didn't interest me. I wanted to be introduced to Gandalf. Naturally he'd be there. The Tolkien guy probably never travelled without him. They might even be going to Galway on the same train as my father.

But he didn't take me with him. Instead he left saying he'd be back again on Thursday. So it never happened.

If I've thought of it at all since that day in the 1950s, I've wondered if I imagined it.

And then this morning there was this

NUI Galway Archives

Happy Birthday to JRR

Felicity Hayes-McCoy

Felicity Hayes-McCoy  NUI Galway Archives

NUI Galway Archives I love Twitter. Now I'm going back to Chapter Six of the new novel.

My mother, my father and me in the late 1950s

My mother, my father and me in the late 1950sVisit The House on an Irish Hillside on Facebook

Published on January 03, 2013 08:20

December 18, 2012

Thinking About The Gathering 2013

I became aware of The Gathering 2013 back in 2011. It was a corner-of-the-eye thing, spotted online and then forgotten. I was in Ireland writing The House on an Irish Hillside, a book that's part memoir, part exploration of my own sense of identity as a member of the Irish diaspora, and partly an examination of the Dingle Peninsula's Celtic inheritance. Which, I suppose, is why something called The Gathering caught my eye.

The ancient Celts disapproved of writing. They believed it weakened their ability to remember; and in their worldview shared memory was the vital component that bound people together in a web of individual awareness of communal identity. In Ireland they reinforced and passed on their sense of community at seasonal tribal gatherings deliberately sited on mountaintops which gave them the widest possible view of the landscape with which they identified.

It was a formidably successful culture, characterized by its own diaspora which was apparently fuelled by expanding tribal populations, a warrior ethos, and a culture of maintaining close links with its homelands. Celts seem to have started out east of the Rhine and expanded across huge areas, including much of Britain, Ireland, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Austria and Italy. They spread along the Danube towards the Black Sea, pressed on to Thrace and Macedonia and made contact with the Scythians. At the height of their expansion they crossed into Asia Minor, founded settlements in Galatia, in eastern Phrygia, and occupied the site of modern Ankara. What's remarkable is that they did this without financial systems, written records, or administrative centres. Instead, their cultural identity was expressed across vast territories by shared language, belief systems, customs, skills and art.

The Gathering 2013 is a government initiative reaching out to Ireland's worldwide diaspora. It's designed to boost the tourist trade and encourage emotional and financial investment in the home country. Glamourised by identification with the concept of ancient Celtic gatherings, it's a feelgood project in a time of world recession, intended to showcase Ireland's willingness to embrace not only those with Irish roots but those who identify with Irishness.

And as 2013 approaches I'm fascinated by the emotions it's arousing in Ireland.

What delights me about those ancient Celtic gatherings is that they seem to have made no distinction between their spiritual, social and economic elements. They involved sacred shamanist rituals to promote, balance and support the powerful flow of energy which, in their belief system, linked and animated each element in the universe. But they were also huge, cheerful parties at which goods were bartered, marriages arranged, and animals bought and sold, amidst feasting, music and dancing. It was a system designed to reinforce shared identity by identifying and passing on shared values. And it took place in settings intended to reflect an ideal state of balanced interdependence.

Part of the challenge for The Gathering 2013 is that it's a response to economic crisis. Recession's hit hard in Ireland and anti-government feeling's rife since the latest budget proposals have been unveiled. There's general resentment and trepidation, and cuts to child benefit and carers' allowances in particular are seen as indications that our politicians have little respect for women. Added to that, in the wake of a young woman called Savita Halappanavar's tragic death in a Galway hospital, many Irish people currently feel ashamed rather than proud of their inherited values.

Savita, an Indian immigrant to Ireland, was pregnant but it became clear that the pregnancy wasn’t medically viable. Her own medical condition was deteriorating so, recognising that they’d already lost their baby, she and her husband asked for a termination. But an unresolved discrepancy between Ireland’s legislation and its constitution led to the conclusion that termination would be illegal while a foetal heartbeat remained detectable. Ultimately Savita and her baby both died.

The case is still under investigation but when the story broke thousands of Irish people took to the streets with banners. Abortion’s a political hot potato in Ireland where part of our cultural inheritance is a legacy of state subservience to the Roman Catholic Church. Many people, including some with moral objections to abortion, believe Savita's death occurred as a result of political unwillingness to confront that legacy. Others, including myself, feel shamed by our unawareness of the legislative position and its implications and, to that extent, believe we own a share in the responsibility for what happened.

Coming in the wake of a series of revelations about paedophilia in the priesthood and the Vatican's response to them, the combination of the Halappanavar's tragedy, the government's austerity measures, and its plans for The Gathering 2013 seem to have touched a deep nerve in Ireland's national consciousness. Last month the image of one placard protesting at Savita's death went viral on the internet. “You Wanted A Gathering,” it read, "You Got It.”

So the feelgood initiative's become a focus for protest. But, in my opinion, that’s not a bad thing.

A few weeks ago I was asked if I’d take part in a Gathering 2013 events launch in Dingle town on New Year’s Eve. I was glad to. Here on the Dingle peninsula, an area that's suffered successive, crippling waves of emigration since the nineteenth century, The Gathering offers a practical boost to the tourist trade on which hundreds of families depend for employment. The same applies all across Ireland, where individuals and locals have come together with energy, creativity and wit to embrace the initiative as an expression of self-help and solidarity in recession. That in itself seems a valid reason to support it.

But to my mind there are other reasons as well. For me they're rooted in the template provided by those ancient gatherings that seem actively to have made no distinction between the spiritual, social and economic elements of the society they expressed. Recently, responding to public pressure, the Irish government’s announced its intention to introduce new legislation on abortion. I can’t think of any subject so much in need of a broad, balanced context for debate. Or any country in which the sacred needs so badly to be reconciled with the profane.

On that basis I can’t imagine a better forum for debate on Irish values than The Gathering 2013. It seems to me that its greatest strength lies in the fact that the government’s reached out to the worldwide diaspora, contextualizing national issues and encouraging input across vast territories from people with a shared sense of identity but strongly contrasting ideas about what that might actually mean. I think that if we grab it by the scruff of the neck and use it, The Gathering can be more than just a huge, year-long party to boost the economy. It can be a creative focus for something profound.

Visit The House on an Irish Hillside on Facebook

Published on December 18, 2012 12:33

November 20, 2012

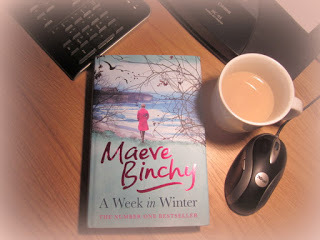

Thinking about Maeve Binchy

This time last year I wrote a sentence which I remember erasing twice. Each time I typed it I was afraid it might seem pretentious. And each time I erased it I felt like a coward and typed it again. ' My own trade', I wrote, 'is crafting the world into words'. In the end it took assurances and endorsement from others before I could let it stand.

Why is it so hard for a writer to have confidence in what she does? Why should I feel my statements need external endorsement before I can write them down? In the past I believed it's because writers work alone. There's a sense in which we create without any context: and that's ironic because creation is about contextualisation; the act of writing is about framing and re-framing life as a series of pictures, juxtaposing one against another to provide the balance and perspective that enhance awareness of the world. All in an attempt to understand it.

For over a year, as I wrote The House on an Irish Hillside, I explored the ancient Celtic concept of a joined-up universe in which everything that exists, or ever has existed, shares a living soul. It's a worldview that expands the idea of individuality and redefines the function of community. It's rooted in the idea that balance is the essence of health. And it rejects the idea that death destroys life.

During that year, and in the months before it, my own life was shaken by death, and my perceptions of health and how to maintain it were challenged. Unable to write, sometimes unable to think, eat, sleep or - it seemed - even to breathe, I experienced two apparent opposites. One was the emptiness of feeling utterly alone. The other was the incomparable comfort of communal support from neighbours and individual support from friends.

Among those friends was Maeve Binchy, whose warm, unsentimental, practical advice arrived in a series of phone calls and postcards, supplemented by large glasses of white wine and plates of smoked salmon sandwiches. I'd known Maeve since I was a child and when she died in August this year my world, which still felt delicately balanced, was suddenly shaken again.

Maeve's funeral was a celebration of her life. Her coffin emerged from the church to the soaring sound of traditional Irish music. Her photo was displayed in shop windows in the streets of the little town she'd lived in, where her neighbours lined the pavements to say goodbye. Tributes poured in from statesmen, fellow-writers and readers, all praising her talent, generosity, compassion and charm. Along with huge numbers of her friends throughout the world, I've missed her ever since.

A few days ago I travelled from Corca Dhuibhne back to London and found a padded envelope waiting among my post. Inside was a copy of Maeve's latest book, A Week in Winter. It was sent, said the inscription, because Maeve had wanted me and my husband to have it and it came 'with her love'. It's vintage Maeve Binchy - warm, compassionate and astringent, razor sharp and richly intelligent. And, like everything she wrote, it's informed by equal measures of energy, enthusiasm and optimism.

Before she died Maeve made a statement. She didn't believe in god, she wrote. She'd thought about it for a lifetime, wanting to hold onto the faith in which she'd been raised. But she now knew that what she believed in was life, love and kindness, and human potential for good. It was a brave statement and I suspect that in making it she may have lost some fans who saw her as a feelgood writer who dealt in certainties, not soul-searching. But a life of examined awareness had led to her conclusion and, as a writer, she needed to share what she perceived to be true. Her funeral was held in a church where the priest reiterated her statement from the altar. It was an honest, dignified memorial characterised by no hypocrisy, deep grief and much humour.

Like Maeve, I don't believe in a god. But I don't believe either that death's destroyed her life. In the obvious sense she still lives in her books. But that's not what I mean. Everything I've learned from my own experience suggests that our Celtic ancestors were right. On some level that exists now, in a circular universe in which linear time as a concept is irrelevant, everything that exists continues to exist and shares a living soul. So, although it wasn't published until after she died, I think that the book that's beside me on the desk as I write this really has come with her love.

In the past I believed that isolation was part of the writer's condition. In a practical sense that's true, and it makes the perfect environment for crises of confidence. But the real truth, I think, is that it's impossible to be alone. I believe that as writers we create as individuals. But we reflect a world within a universe where everything's joined up - a state in which each element is vital and equal, and all are balanced by an animating flow of energy which means death's always pregnant with life.

I wish I could talk to Maeve about that. Balance expressed with humour inhabits the heart of her work. For much of her life she lived with ill health. She knew light doesn't register without darkness. There've been so many times since she's died that I've reached for the phone and been stabbed by the memory that she's gone. She was a mentor as well as a friend. I loved her bossy, witty, crystal clear analysis of situations and ideas, the stories with which she illustrated them, her certainties and her doubts. I'd value her opinion of my own new, still slightly precarious worldview.

And I'd like her to know that I no longer need anyone's endorsement to have the courage to write it down.

Visit The House on an Irish Hillside on Facebook

Published on November 20, 2012 10:28

November 15, 2012

A Winter Day on the Dingle Peninsula

Preheat the oven to c230/ gas 8. Scatter flour thickly on a large, heavy baking tray. Sieve twelve ounces of plain, white, unbleached flour and a level teaspoon of bicarbonate of soda into a large bowl. Hold the sieve as high as you dare, to incorporate plenty of air. Add a large pinch of salt if you want to. I never do. Then sieve four ounces of wholemeal flour into the bowl as well, tip the residue of bran in after it, and throw in a handful of linseed or sunflower seeds, and maybe a fistful of oats.

Tap the bowl on the table to bring everything to the bottom. Then combine the lot with a swirl of your hand in one direction and a turn of the bowl in the other.

Next make a well in the centre of the mixture and add 350ml of buttermilk all in one go. (I know I've mixed metric and imperial measures, that's the way my mind works. And anyway I just use the full of a big glass for the buttermilk.)

Then, using one hand and turning the bowl with the other, draw the flour into the buttermilk, combining them.

Work from the sides to the centre; it shouldn't take more than a minute. The ball of dough you end up with should be soft, but not wet or sticky. If you need to, add a bit more flour or buttermilk. You'll know you're right if the dough comes together quickly, and it leaves the bowl perfectly clean.

Throw some flour on your table and turn out the dough. Wash and dry your hands. Knead your bread from the sides to the centre for just a few seconds, turning it, to make a round loaf.

Flip it over onto the baking tray. Pat it down with a floury hand. You want it about two and a half centimetres thick. Then cut a deep cross through the loaf, almost dividing it into triangles. It'll come together as it rises.

Bake for fifteen minutes in the hot oven, then reduce the heat to c200/ gas 6 for another twenty. Keep an eye on it for the last ten minutes. You can turn it upside down if it's getting too brown.

It's done when the bottom sounds hollow when you tap it with your knuckle.

Cool the bread on a wire rack. Eat it on the day you bake it - hot, with butter and honey. Or with blackcurrant jam.

Visit The House on an Irish Hillside on Facebook

Published on November 15, 2012 13:09

November 11, 2012

Echoes of ancient Irish ritual on St. Martin's Day

It was dark last night as we drove home across the country. Our last stop had been in Clonmel at the seventh bookshop in three days in which I'd met booksellers, chatted to readers and signed copies of The House on an Irish Hillside before taking photos, grabbing another coffee and a sandwich and taking to the road again with the mapbook on my knee.

It had been a lovely trip along autumnal Irish roads that snaked between broad, harvested fields edged by stone walls, tall trees or golden-brown beech hedgerows. But as darkness fell and rain began to spatter the windscreen my mind was reaching out for the rougher, wilder landscape of West Kerry, Tí Neillí Mhuiris and home.

We lit the fire when we came in, sweeping away the soot and ashes blown down onto the stone hearth in our absence, and heated soup for our supper. A fierce wind was gusting from the ocean. Later we slept again in our own bed, protected from the gale by the cluster of ashtrees planted at our north gable nearly a hundred years ago by Neillí's husband, Paddy.

This morning we got up late, pottered round a bit and walked down the hill to see Jack.

His kitchen was warm and welcoming, full of the lingering smell of a fine chicken dinner, just being cleared from the table. We sat down and chatted about book signing and the weather, and the birth of a new baby to a neighbour below in Ballyferriter. The table was cleared and wiped clean, the scraps were gathered onto a plate, and outside the door Spot twitched in anticipation of her own dinner. She eats it each day from an old fryingpan at the corner of the house, scrupulously leaving a few mouthfuls behind her for the hens to eat in their turn.

As the chicken carcass was removed from the table we were still talking schedules and booksignings. Someone asked about the date - was today the tenth or the eleventh? 'It's the eleventh,' said Jack as the rest of us glanced round for the calendar or reached for the local paper. 'It's St. Martin's day'.

And he told us another story about Tí Neillí Mhuiris.

Neillí always killed a hen for St. Martin's day and Paddy took his dog up onto the mountain and killed a hare: they were plucked, skinned and prepared by Neillí and cooked over the fire on the hearth I swept last night. It was always the way on St. Martin's day, to eat a fine dinner.

I asked Jack why and he just shook his head. 'It was always the custom'.

When we came back to the house I switched on the computer.

St. Martin's Day, or Martinmas, is a time for feasting, when autumn wheat seeding was completed, fattened cattle were slaughtered and, historically, hiring fairs were held where farm labourers gathered looking for work. In the Christian calendar November 11th is dedicated to St. Martin of Tours, a Roman soldier who was baptized as an adult and became a monk. From the fourth century AD to the late middle ages much of Europe observed a period of forty days of fasting beginning from St. Martin's Day. And on the eve of the fast people cooked and ate a fine dinner, which traditionally included a cockerel, a goose or a hen.

But the tradition of feasting on St. Martin's day is far older than Christianity. November 11th falls roughly midway between the September Equinox and the Midwinter Solstice. It's one of the ancient Celtic festivals associated with harvest-time, when bonfires were lit on the hills, cattle were slaughtered, and the blood of sacrificed cockerels was sprinkled on thresholds to bring fertility to the farm and protect the household from famine in the dark months ahead. It was a ritual act, traditionally carried out by the woman of the house. Afterwards the whole family would feast on the sacrificial victim.

'It was always the custom to have a good dinner on St. Martin's day,' said Jack. 'Paddy hunted a hare on the mountain. And Neillí always killed a hen.'

Visit The House on an Irish Hillside on Facebook

Published on November 11, 2012 09:50

November 2, 2012

Memories Of My Enniscorthy Granny

I'm writing this on a chilly evening in Tí Neillí Mhuiris after a long day spent making arrangements for an Irish book signing tour. Hours on the phone talking to lovely, welcoming booksellers, eager to advise me where to park when Wilf and I arrive in Cork, Clonmel, Wexford or Waterford next week. Emails confirming dates. Updates on local radio slots. Interviews with local newspapers. Piles of notes on my desk waiting to become the orderly schedule I always need to type out for myself before we set off.

But now, with a glass of wine by my elbow, I'm able to think past logistics to the joy that's to come. This time next week I'll be back in the soft green landscape of Wexford amongst memories of my Enniscorthy granny, a tiny, gentle lady who marched through life with the courageous motto that one should always 'keep the best side out.'

In Chapter Five of The House on an Irish Hillside I write about the starched cloth on the polished table where we had tea when we visited Enniscorthy; granny's own mother’s blue and white china, patterned with roses; and pink biscuits in a cut glass biscuit barrel. For some reason, they were known as ‘curly-wees’. I remember gooseberry jam, made with fruit from granny's garden, and ‘country butter’ served on thin slices of brown soda bread.

Granny's house in Enniscorthy was built on a hill and the long garden had a raised terrace running along one side. I remember conifers, and tall ivory-coloured lilies on thick green stems, with golden stamens and petals like curled vellum powdered with pollen. There were flagstones outside the kitchen door and a path that ran down the garden to apple trees and fruit bushes.

One day, when I was four or five, I was sent out to play. Running at full tilt, I tripped on a stone and landed flat on my front in a puddle. I can remember my nose streaming and the salty taste of tears as I stumbled, dripping, back up the path and into the kitchen. After I was washed, dried and put into a clean frock, I was given a curly-wee and told to sit on the doorstep while my damp socks were hung by the fire. Granny left me there with a kiss and one of her brisk, ritual sayings. ‘It’s-all-over-now-throw-my-hat-in-the-sky!’ I never quite knew what that meant, but my mother used to say it too when things had gone wrong and it was immeasurably comforting.

Later, the three of us walked down the garden together, the mother, the child and the old woman. I remember the strength of their hands as they swung me across the puddle, and standing between them as we counted the hard, green apples setting on the apple trees. The same trees are still there today. Spring blossom still sets on their gnarled branches, now propped with stakes and powdered with grey lichen.

Each autumn when I was a child, Granny sent boxes of apples on the train from Enniscorthy to Dublin, carefully tied with twine and addressed to my mother, ‘to be collected’. I remember learning to make apple tart in our kitchen in Dublin, the print of my mother's thumb crimping the edges, and the mark of her wedding ring on the pastry scraps she’d flatten with her hand and pinch into leaves for decoration. When I look down at my hands as I type this I can see that ring on my own finger.

Next week as I sit signing copies in a Wexford bookshop, I'll be thinking of my granny. Wexford's only about fifteen miles from Enniscorthy but going there after she was widowed meant a lonely, daunting trip to the big city. I still remember her tiny, upright figure, shining buttoned shoes, and the jaunty tilt of her hat as she walked down the hill to the station, shoulders back, head up, keeping the best side out.

And sitting here now I realise I'm just a bit daunted myself. Booksignings are like that. You wonder if people will come. If they've liked your book. If you'll spill your coffee or your pen will leak. You worry that you'll lose your schedule or the car keys or forget how to spell your own name.

But my granny had another saying, ritually produced whenever I got shy before a party. 'You'll-love-it-when-you-get-there-so-you-will.' And I know she's right. I've never arrived at a signing to anything but broad smiles and cheerful welcomes. It's great to meet friendly readers, hear fascinating stories, and put faces to names you've only known from Twitter or Facebook, or from warm, perceptive comments on your blog.

In fact the only daunting thing is crossing so many new thresholds. And that's just a matter of keeping your shoulders back, head up, and the best side out.

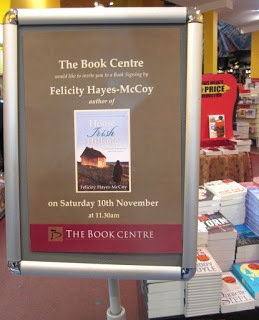

I'll be signing copies of The House on an Irish Hillside in Cork Thurs. Nov 8th Easons, Patrick St. 12.00 noon/ Mahon Shopping Centre 2.30pm: Wexford Fri. Nov 9th The Book Centre, South Main St. 2.00pm: Waterford Sat Nov 10th The Book Centre John Robert Sq. 11.00am: Clonmel Sat Nov 10th Easons, Gladstone St. 3.30pm.

Visit The House on an Irish Hillside on Facebook

Published on November 02, 2012 14:18