Felicity Hayes-McCoy's Blog, page 2

April 9, 2018

I'M PROOFREADING

There are different stages to writing a novel.

The initial inspiration which seems to happen in dream time, when you wake one morning - or pause in the midst of cooking or doing your laundry - with a fully formed concept in your mind.

The hours, and sometimes days, you spend crafting a pitch for your editor, which needs to demonstrate the essence of your book in a few paragraphs.

The period of meticulous plotting which, in my case, involves squared paper and coloured markers. And then the long months of writing when you live in a sort of cocoon.

Then finally, after the copy edit, there's the proof stage, when you're back to colour - this time a red pen.

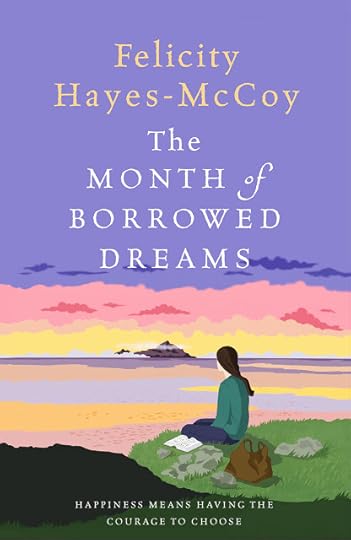

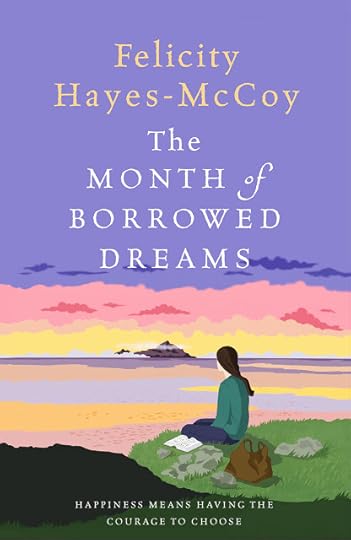

At the moment I'm finishing the proofs of The Month of Borrowed Dreams, the fourth Finfarran novel about local librarian Hanna Casey and her neighbours. It's set in May time on Ireland's western seaboard and, given that we're well into April, the pages I'm reading should describe a version of the view from the window by my desk. The wildflowers on the ditches should be budding perhaps, not blooming, but the mountains should be glowing against blue skies and the garden bursting into life.

Instead, as my characters move through green fields and picnic on sunny beaches, the view from my desk is lost in mist and the windows stream with rain.Because, as I proof read The Month of Borrowed Dreams, I'm living through the borrowed days.

Let me explain. There’s an Irish folktale about a cow on a mountain who boasts that the weather in March can't kill her. So March borrows a few days from April and batters the old cow to death with a violent storm. That's why the first days of April are known in Ireland as laethanta na riabhaiche, which means ‘the borrowed days’. (You pronounce them 'lay-han-ta nah reeve-uk-ah')

This year the borrowed days have lasted longer than usual. It's cold and everything's stagnant; and whenever the season seems to move on the rain and hail return. Yet you know it's just a stage that has to be gone through and that, once it's over, the sun will emerge, calling you out of doors.

Like the turn of the year from one season to another, each stage of writing a novel carries a particular pulse. Proof reading is nothing like the dream time of inspiration, or the heavy cocoon of creation, or the in-between stage when you try to capture the essence of something yet to be explored. Instead it's nit-picking and finicky, and sometimes it feels as if it will never be done.

Today I'm wearing a fleece over three T-shirts, heavy trousers, Uggs and woolly socks. I sit here with my red pen noting misalignment and misplaced commas, and double-checking the publisher's proof reader's queries about the text. I'm polishing and refining, ensuring that the book's transition to the page is unimpeded by errors. Basically, it's a matter of hard slog.

But there's pleasure in this link between the writer's craft and the typesetter's skill, and in the promise of the finished book to come and feedback from readers all over the world.

And, with this book, there's the added satisfaction of borrowed days in which to proof read, before the beaches and the mountains call, and the ditches start to bloom.

Pre-order/Read about The Month of Borrowed Dreams

Visit my Author Page on Facebook

The initial inspiration which seems to happen in dream time, when you wake one morning - or pause in the midst of cooking or doing your laundry - with a fully formed concept in your mind.

The hours, and sometimes days, you spend crafting a pitch for your editor, which needs to demonstrate the essence of your book in a few paragraphs.

The period of meticulous plotting which, in my case, involves squared paper and coloured markers. And then the long months of writing when you live in a sort of cocoon.

Then finally, after the copy edit, there's the proof stage, when you're back to colour - this time a red pen.

At the moment I'm finishing the proofs of The Month of Borrowed Dreams, the fourth Finfarran novel about local librarian Hanna Casey and her neighbours. It's set in May time on Ireland's western seaboard and, given that we're well into April, the pages I'm reading should describe a version of the view from the window by my desk. The wildflowers on the ditches should be budding perhaps, not blooming, but the mountains should be glowing against blue skies and the garden bursting into life.

Instead, as my characters move through green fields and picnic on sunny beaches, the view from my desk is lost in mist and the windows stream with rain.Because, as I proof read The Month of Borrowed Dreams, I'm living through the borrowed days.

Let me explain. There’s an Irish folktale about a cow on a mountain who boasts that the weather in March can't kill her. So March borrows a few days from April and batters the old cow to death with a violent storm. That's why the first days of April are known in Ireland as laethanta na riabhaiche, which means ‘the borrowed days’. (You pronounce them 'lay-han-ta nah reeve-uk-ah')

This year the borrowed days have lasted longer than usual. It's cold and everything's stagnant; and whenever the season seems to move on the rain and hail return. Yet you know it's just a stage that has to be gone through and that, once it's over, the sun will emerge, calling you out of doors.

Like the turn of the year from one season to another, each stage of writing a novel carries a particular pulse. Proof reading is nothing like the dream time of inspiration, or the heavy cocoon of creation, or the in-between stage when you try to capture the essence of something yet to be explored. Instead it's nit-picking and finicky, and sometimes it feels as if it will never be done.

Today I'm wearing a fleece over three T-shirts, heavy trousers, Uggs and woolly socks. I sit here with my red pen noting misalignment and misplaced commas, and double-checking the publisher's proof reader's queries about the text. I'm polishing and refining, ensuring that the book's transition to the page is unimpeded by errors. Basically, it's a matter of hard slog.

But there's pleasure in this link between the writer's craft and the typesetter's skill, and in the promise of the finished book to come and feedback from readers all over the world.

And, with this book, there's the added satisfaction of borrowed days in which to proof read, before the beaches and the mountains call, and the ditches start to bloom.

Pre-order/Read about The Month of Borrowed Dreams

Visit my Author Page on Facebook

Published on April 09, 2018 10:17

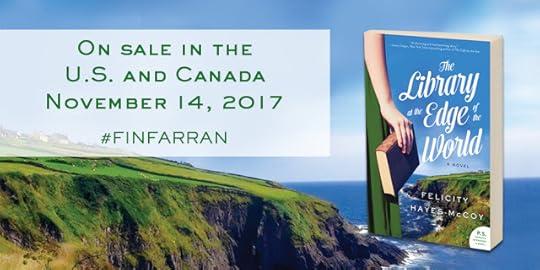

November 12, 2017

The First Finfarran Book Crosses The Atlantic

Well, look at this. My North American debut. When I was an actress I thought that word only applied to performance but, no, it's what publishers say about books as well.

Actually, the dictionary definition is as follows:-

A person's first appearance or performance in a particular capacity or role.

Synonyms: first appearance, first showing, first performance, launch, launching, coming out, entrance, premiere, beginning, introduction, inception, inauguration.

informal:kick-off.

I love

"informal:kick-off".

I may substitute it for "debut" in conversation from now on.

I've always been a sucker for synonyms and dictionary definitions, which is one of the reasons why working with my US editor on The Library at the Edge of the World has been such fun.

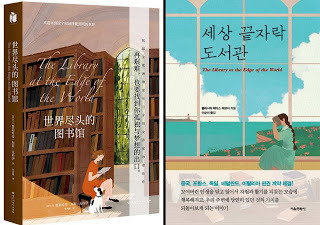

The book, the first in my "Finfarran" series of novels, is already available, with two others, across Europe, and in Australia, China and South Korea. In the case of the latter two, the covers are stunning but I've no idea what the lovely typography actually says. My name and the title, obviously. But which is which?

When it came to preparing the US and Canadian edition I'd never imagined there'd be issues of translation. But, of course, in a way, there were. The book went through a process known as 'Americanization' (note the 'z') in which spelling, grammar and, very occasionally, idiom were checked and changed where appropriate, for North American readers.

It was fascinating. As Oscar Wilde wrote in 1887 "We have really everything in common with America nowadays except, of course, language". Or as George Bernard Shaw said - according to Reader’s Digest, November 1942 - "England and America are two countries separated by the same language".

The manuscript, in digital form, went to and fro across the ocean, with my editor and her colleagues meticulously checking every point with me. Would it be okay to change the word for a piece of furniture in Maggie's house from the Irish "dresser" to the US "hutch"? Definitely not! What about changing 'petrol station' to 'gas station'? Absolutely. And 'mobile' to 'cell phone'? But of course!

There was careful consultation about the differences between "timber" and "lumber", and the correct words to describe the materials Fury O'Shea stripped from Hanna's roof when her back was turned. There was the knotty question of whether or not "a súgan chair" needed to be explained. And that heated moment when we faced the fact that there isn't an American equivalent for Jazz's favourite childhood treat "fat chips".

And always there were reassurances, in phone calls and in emails, from my editor. "We want to be sure to preserve the characters' voices". "We mustn't lose the shape and the flow of the text."

They didn't. The result is a beautiful new edition, and an author who's had a brilliant time browsing through US dictionaries - and, incidentally, discovering how often "Irish English" echoes the rhythms and vocabulary of the English carried from Plymouth by America's Pilgrim Fathers.

Nothing had prepared me for the unexpected pleasures of the editorial journey I made myself. And now the books are off on their way to US and Canadian bookstores (note "stores", not "shops"

Published on November 12, 2017 05:51

September 17, 2017

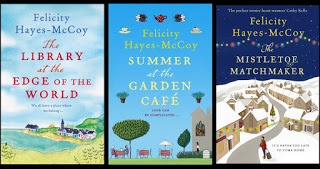

Six Tips For Writing A Successful Book Series

One result of a lifetime of writing in different genres and media is that you end up with transferable skills and systems. Now, with the third novel in my Finfarrran series about to appear in the bookshops, I can see just how useful that process of transfer can be. Much of what I've learned in my career has been passed on to me by other writers, so here are some hints that I thought I should pass on myself.

#1. I started out as a freelance writer in radio and television, where deadlines are paramount. Whether you're writing scripts for dramas, documentaries or features, the bottom line is that it must be delivered on time. A reputation for reliability is one of your greatest references, and that applies to print publishing as well.

#2. Because novelists work alone at a screen, it's easy to feel that writing your book is a private enterprise. But if you're working on a series commissioned by a publisher, it's not. Just as plays or projects for broadcast media, books - and especially book series - are created by a team. As a writer you may be crafting a fictional world or a community of characters but you can't retreat into a world of your own. Claim the space you need for your own creativity but be aware of the importance of other people's input. The idea for my Finfarran books for example, was conceived as the result of a series of conversations with my agent and, when new books are pitched, my editor comes back with her thoughts on storylines, as well as on how each book will fit into the series as a whole.

#3. Some books can take years to write and require endless re-thinking and redrafting. With books like those, you can often afford to make the work organically, discovering the shape of your story as you write. But with a series, where you'll be contracted for two, three or even more books at a time, each with a specific deadline, being disciplined about structure helps. Different writers have different systems: I find that working backwards from my total word count and laying out the whole book chapter by chapter on a chart is the best way for me. It's a shape rather than a rigid system, and allows for flexibility, but I never begin without it and I always have it hanging by my desk.

#4. Writing for television drama, I got used to the idea of every series having a bible - a document which constantly updated details of each character, from personal history and relationships, to favourite foods and physical appearance, as well as information about every setting. For the Finfarran book series I began by drawing a map of my fictional Irish peninsula, adding more information as the various strands in each book focused on different settings. I also list and update facts - physical, emotional and otherwise - about my characters, avoiding contradictions between one book and the next.

#5. In a theatre production, the director and designer can use colour, light and costume to indicate turning points in a story, and to mirror or give hints about a character's emotional state. In a book, a writer can do the same, and weather, the landscape and the seasons can provide a sense of both setting and the passage of time. My Finfarran stories are about modern life in a rural Irish community, so each book carries a strong awareness of the season in which its story happens. That, in turn, gives me opportunities for comedy, empathy or drama: - in The Library at The Edge of The World, Conor, Hanna Casey's assistant, is focused on the birth of a bull calf when he ought to be trying to impress Tim, the county librarian; the regeneration of the old herb garden mirrors the emergence of the community's sense of empowerment; and, in Summer at The Garden Café, the second book in the series, the forest with its dark undergrowth and sun-filled clearing is the meeting-place where Jazz may find herself too deeply involved with Gunther, her employer.

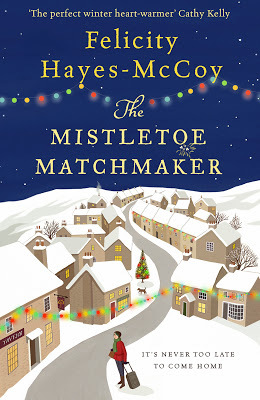

#6. Scripting broadcast documentaries and writing non-fiction books, I became used to researching and cross-checking facts. If you want to create a series that will engage a reader you need to give your fictional world internal logic. Currently I'm writing the fourth book in the Finfarran series, and I'm constantly aware of the importance of consistency. I know how long it takes for my characters to travel from Lissbeg, where Hanna's library is, to the nearest town of Carrick, and how levels of traffic on the road will change at different times of the year. I know how the local council works; when the convent school in Lissbeg closed; where the old marketplace used to be; and when and where they built the new mart. And, as in The Mistletoe Matchmaker, for which, among other things, I needed to check timetables for winter flights to Ireland from Canada, I cross-refer that internal logic with facts and figures in the real world, so that readers are willing to suspend disbelief and accept - at least while they're engrossed in reading - that the Finfarran Peninsula really does exist.

Publication date October 19th 2017. Pre-order your copy online now.

Published on September 17, 2017 12:38

August 25, 2017

The Fabric of Memory

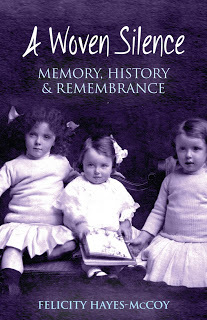

For my grandmother, the white piqué skirts and satin hair-ribbons, and the lace pinafore worn by baby Evie, in this photo of my mother and her sisters were expressions of respectability as well as style. Money was scarce and my granny's motto was "we have to keep the best side out."

That motto was used in many an Irish family. As I say in my memoir A Woven Silence, I find it admirable and disturbing in equal measure. It has certainly contributed to Ireland's continuing unwillingness to confront its culture of gender inequality.

Evie died young but Cathleen, on the left in the photo on the cover above, and my mother, on the right, grew up with my grandmother's sense of style. Which I think must be why, as I drafted the book, I found that my own image of my aunt Cathleen expressed itself continually in images of fabric and fashion.

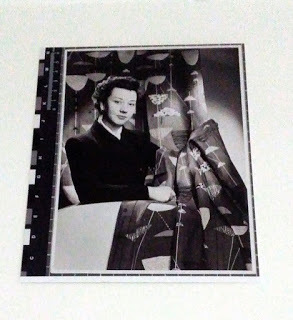

She was unmarried and a career-woman, the only role-model in my childhood that offered an alternative to the accepted vision of an Irishwoman as a wife and stay at home mother. I remember her tiny Dublin flat where her favourite travel books jostled with catalogues from art exhibitions, how she could pack for a flight at ten minutes notice, and how she had a dozen different ways of twisting and tying a scarf.

She was unmarried and a career-woman, the only role-model in my childhood that offered an alternative to the accepted vision of an Irishwoman as a wife and stay at home mother. I remember her tiny Dublin flat where her favourite travel books jostled with catalogues from art exhibitions, how she could pack for a flight at ten minutes notice, and how she had a dozen different ways of twisting and tying a scarf.And yesterday, in a shop called Britain Can Make It, in Elephant and Castle Shopping Centre, she sprang vividly to my mind.

Cathleen adored the work of the designer Lucienne Day, an exponent of a visual modernism that had little or no place in post-World War Two Ireland.

Cathleen adored the work of the designer Lucienne Day, an exponent of a visual modernism that had little or no place in post-World War Two Ireland. I remember worn-out 1940s and 50s dresses and curtain fabric in Day's stunning colours and designs jumbled together in my mother's rag bag and recycled into smocks for me and shirts for my sisters. And the Belfast linen tray cloths and tea towels that Cathleen would produce as presents and my mother would tuck away in drawers as too good for everyday use.

And then there they were again yesterday in Elephant and Castle. The colours and shapes and designs and that beautiful linen. All the cosmopolitan courage and flair that Ireland lacked in my youth.

Visit my Author Page on Facebook

Published on August 25, 2017 09:52

June 23, 2017

Oíche Shin Sheáin: St John's Eve is Bone Fire night in West Kerry.

The word 'bonfire' derives from the Late Middle English 'bone fire' and originally referred to large, open-air fires on which bones were burnt, often as part of communal celebrations.

The word 'bonfire' derives from the Late Middle English 'bone fire' and originally referred to large, open-air fires on which bones were burnt, often as part of communal celebrations. June 23rd is St John's Eve when, in many parts of Ireland, a 'tine chnámh', or 'bone fire' was traditionally lit at sundown as the focal point of festivities concerned with fertility and the land. The nature of the ritual and the proximity of the saint's day to the summer solstice, on or about June 21st, indicate the subsuming of pagan fertility rites into Christian worship.

Fires fuelled by bones, timber or turf were lit on boundaries, promontories, shorelines and hilltops, where communities gathered to sing, feast and dance, and young men would compete to leap through the flames.

In some places cattle were ritually driven between two fires to protect their health, and prayers and charms were recited to promote the year's successful harvest.

The bone fire flames were considered lucky. Bringing embers into houses to rekindle cooking fires on the hearth promoted the health of the household; while healthy crops were ensured by burning weeds, scattering ashes on the land, and walking field boundaries with lighted sods of turf or branches.

Similar rites can be found on St John's Eve throughout Europe and Scandinavia where the festival is also linked to bone fires.

June 23rd is also the night on which women traditionally gather healing herbs, such as St John's Wort, Meadowsweet and Yarrow. These were burned to promote health as well as prepared and stored to be used medicinally. In Galicia herbs gathered on St John's Eve, called herbas de San Xoán, are still left to steep overnight in water, while in some parts of Ireland they were exposed overnight to dewfall and used as a cosmetic face-wash the following day.

Here in Corca Dhuibhne, some farmers still light a tine cnámh on field boundaries on St John's Eve, and people still gather to celebrate the festival.

And tonight, on yet another long midsummer evening, the healing smoke and flames will rise again in a tradition that, in these parts, stretches across millennia to the time of the Corcu Dhuibhne - the People of The Goddess Danú.

************* Follow my Author Page on Facebook

Published on June 23, 2017 04:58

June 20, 2017

Danny Sheehy: Loss of a Voyager.

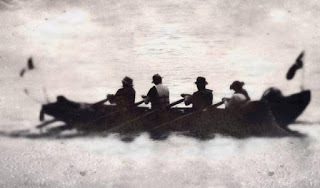

Tonight in Corca Dhuibhne neighbours came together to wake Danny Sheehy in his home in Baile Eaglaise close to the burial ground at Dún Urlann where he'll be carried tomorrow after his funeral mass. He died on Friday June 9th after a boat which he and a friend had built, and of which he was a crew member, overturned off the northwest coast of Spain.

Danny and his companions were returning from a sea pilgrimage, taking the old medieval pilgrim route of The Camino de Santiago in a naomhóg - a traditional Irish boat with a wooden frame over which a covering of tarred canvas or calico is stretched. The boat was called the Naomh Gobnait, after a legendary saint associated with the area, and, according to the medieval Nauigatio sancti Brendani abbatis, a similar craft carried the monks who took part in the Voyage of St Brendan, the saint after whom Corca Dhuibhne's Mount Brandon is named.

Over a period of years, beginning in 2014, the Naomh Gobnait had continued on its journey each summer, arriving last year in Santiago de Compostela, where it was carried into the Cathedral to the sound of music played by the traditional Irish musician, Breanndán Ó Beaglaoich, one of the crew.

Over a period of years, beginning in 2014, the Naomh Gobnait had continued on its journey each summer, arriving last year in Santiago de Compostela, where it was carried into the Cathedral to the sound of music played by the traditional Irish musician, Breanndán Ó Beaglaoich, one of the crew.

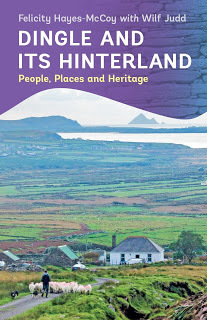

Others, who knew Danny better than I did, will write about his prowess as a boatman; a boat builder and a poet; a folklorist; a storyteller; a philosopher; and a friend. Here, in his own words, are some of his thoughts about his voyaging, given to Wilf and me last year when we were collecting the conversations which are the core of each chapter of Dingle And Its Hinterland: People, Places and Heritage.

We recorded Danny as he and I sat in the back of a car by the sea, near Baile Eaglaise, and when I came to transcribe and translate his words from Irish to English they flowed smoothly and steadily, like the powerful rhythm of the waves.

‘It’s hard to know why something like Camino na Sáile happens. You’re going into great danger and I don’t think you’re ever able to tell yourself why. You never have the answer. But it comes from a love of the sea. Love of your own place – the hills and the cliffs and the mountains and the sea. When you’re at sea there’s always a connection with the place you came from. Your mind is always going back to it.'

'I made many a voyage before the Camino. Around Ireland. Across the Atlantic in a Connemara Hooker. To Spain that way as well – from Dublin to Santander. And other voyages. One from Trieste down to the Adriatic and the Mediterranean and back to Connemara. And one from Dingle in 2011, up to Shetland and on to the Faroe Islands and across to Iceland and back again to Dingle. I suppose there was spirituality involved in all of them.'

'Mount Brandon is very important to me. Before I take such a voyage I’ll constantly go up Mount Brandon by way of preparation. Before going to Iceland I’d say I went up and down at least twenty times. It made me think. It made me remember. It prepared my mind. Because it’s so hard. You have to focus your mind and your soul – everything. And you have to strengthen your body.'

'When you walk alone to prepare yourself you think of how your ancestors took those same paths up the mountain. You think about God. I do that. I believe in God. I suppose many people don’t, but I do. I believe that there’s another life in which the people who died before us live, and that they’re still all around us. And that if I trust them they help me.’

'There’s a difference between fighting against the odds and winning as a voyager and winning a game or a competition if you’re an athlete. When you’re the victor at sea you’ve beaten no one. You’ve done something remarkable, but what you’ve been fighting is the sea itself and the weather and fear - and even ignorance. You learn something. About yourself and about the world you live in.'

'People are very important. Before I leave this place it’s important that people bless me and wish me well. There are people who say they’ll pray for me. That they’ll light a candle for me. I know one man who will keep a candle lit here without ever quenching it throughout the whole voyage. Such things help you and give you energy. The energy crosses the space between you. Another important thing – I think I learnt this from going up Mount Brandon – is that you must never complain. You can’t complain on a sea voyage. It doesn’t matter what pain you might be in or how much other people might be upsetting you, or whatever happens, you mustn’t complain. You must take pleasure in everything or you lose the energy that sustains you.’

'There’s a saying in Irish that there are three things that are magical - music, fog and sailing. I’d say myself that sailing in a naomhóg is the most magical of the three.’

Danny and his companions were returning from a sea pilgrimage, taking the old medieval pilgrim route of The Camino de Santiago in a naomhóg - a traditional Irish boat with a wooden frame over which a covering of tarred canvas or calico is stretched. The boat was called the Naomh Gobnait, after a legendary saint associated with the area, and, according to the medieval Nauigatio sancti Brendani abbatis, a similar craft carried the monks who took part in the Voyage of St Brendan, the saint after whom Corca Dhuibhne's Mount Brandon is named.

Over a period of years, beginning in 2014, the Naomh Gobnait had continued on its journey each summer, arriving last year in Santiago de Compostela, where it was carried into the Cathedral to the sound of music played by the traditional Irish musician, Breanndán Ó Beaglaoich, one of the crew.

Over a period of years, beginning in 2014, the Naomh Gobnait had continued on its journey each summer, arriving last year in Santiago de Compostela, where it was carried into the Cathedral to the sound of music played by the traditional Irish musician, Breanndán Ó Beaglaoich, one of the crew. Others, who knew Danny better than I did, will write about his prowess as a boatman; a boat builder and a poet; a folklorist; a storyteller; a philosopher; and a friend. Here, in his own words, are some of his thoughts about his voyaging, given to Wilf and me last year when we were collecting the conversations which are the core of each chapter of Dingle And Its Hinterland: People, Places and Heritage.

We recorded Danny as he and I sat in the back of a car by the sea, near Baile Eaglaise, and when I came to transcribe and translate his words from Irish to English they flowed smoothly and steadily, like the powerful rhythm of the waves.

‘It’s hard to know why something like Camino na Sáile happens. You’re going into great danger and I don’t think you’re ever able to tell yourself why. You never have the answer. But it comes from a love of the sea. Love of your own place – the hills and the cliffs and the mountains and the sea. When you’re at sea there’s always a connection with the place you came from. Your mind is always going back to it.'

'I made many a voyage before the Camino. Around Ireland. Across the Atlantic in a Connemara Hooker. To Spain that way as well – from Dublin to Santander. And other voyages. One from Trieste down to the Adriatic and the Mediterranean and back to Connemara. And one from Dingle in 2011, up to Shetland and on to the Faroe Islands and across to Iceland and back again to Dingle. I suppose there was spirituality involved in all of them.'

'Mount Brandon is very important to me. Before I take such a voyage I’ll constantly go up Mount Brandon by way of preparation. Before going to Iceland I’d say I went up and down at least twenty times. It made me think. It made me remember. It prepared my mind. Because it’s so hard. You have to focus your mind and your soul – everything. And you have to strengthen your body.'

'When you walk alone to prepare yourself you think of how your ancestors took those same paths up the mountain. You think about God. I do that. I believe in God. I suppose many people don’t, but I do. I believe that there’s another life in which the people who died before us live, and that they’re still all around us. And that if I trust them they help me.’

'There’s a difference between fighting against the odds and winning as a voyager and winning a game or a competition if you’re an athlete. When you’re the victor at sea you’ve beaten no one. You’ve done something remarkable, but what you’ve been fighting is the sea itself and the weather and fear - and even ignorance. You learn something. About yourself and about the world you live in.'

'People are very important. Before I leave this place it’s important that people bless me and wish me well. There are people who say they’ll pray for me. That they’ll light a candle for me. I know one man who will keep a candle lit here without ever quenching it throughout the whole voyage. Such things help you and give you energy. The energy crosses the space between you. Another important thing – I think I learnt this from going up Mount Brandon – is that you must never complain. You can’t complain on a sea voyage. It doesn’t matter what pain you might be in or how much other people might be upsetting you, or whatever happens, you mustn’t complain. You must take pleasure in everything or you lose the energy that sustains you.’

'There’s a saying in Irish that there are three things that are magical - music, fog and sailing. I’d say myself that sailing in a naomhóg is the most magical of the three.’

Published on June 20, 2017 13:43

May 15, 2017

Summer and The Rough Month of the Cuckoo

This week sees the publication of the second in my series of Finfarran novels, set on a fictional peninsula on Ireland's west coast where, in real life, I have my own home. Both the book's name and its release date, May 18th, signal the approach of long, lazy summer days of reading.

And, in my case, gardening.

It's important not to get ahead of yourself where the garden's concerned, though. Because, round these parts, we still have to get through The Rough Month of The Cuckoo.Scairbhín na gCuach* (The Rough Month of The Cuckoo) is the name given in Irish to the uncertain weeks between mid April to mid May when chilly winds from the north and the east can blast the early growth in the garden and send us scuttling home from walks on the mountain to nights of music by the fire. You could call it the extra month in the Irish calendar.

It's important not to get ahead of yourself where the garden's concerned, though. Because, round these parts, we still have to get through The Rough Month of The Cuckoo.Scairbhín na gCuach* (The Rough Month of The Cuckoo) is the name given in Irish to the uncertain weeks between mid April to mid May when chilly winds from the north and the east can blast the early growth in the garden and send us scuttling home from walks on the mountain to nights of music by the fire. You could call it the extra month in the Irish calendar.One day you can be strolling on a beach by a shimmering ocean.

The next day you can wake up to find snow powdering the mountain.

The next day you can wake up to find snow powdering the mountain.

Writing and gardening teach you the same lessons. The best things in life come when the time is right for them to happen. Sometimes you need to be patient and wait till an idea is ready to blossom or a seed to be set.

Writing and gardening teach you the same lessons. The best things in life come when the time is right for them to happen. Sometimes you need to be patient and wait till an idea is ready to blossom or a seed to be set.Every author knows the slow, steady process of drafting, re-working and editing, the discussions about cover images and colour, and the careful distilling of the heart of a work to produce the description on the jacket. It all takes time and, towards the end, you almost feel jaded by the process.

And then - just as the day comes when, at last, the Scairbhín is over - the advance copies arrive through the post, you find yourself doing interviews, and it hits you that, any day now, your book will appear in the shops.

Summer at the Garden Café, the sequel to The Library at The Edge of The World, is about secrets hidden and shared between four generations of women, the fact that love can be complicated, and the healing power of friendship and books. I hope you'll enjoy reading it as much as I loved writing it.

Summer at the Garden Café, the sequel to The Library at The Edge of The World, is about secrets hidden and shared between four generations of women, the fact that love can be complicated, and the healing power of friendship and books. I hope you'll enjoy reading it as much as I loved writing it.The Book Depository has FREE DELIVERY WORLDWIDE on Summer at the Garden Cafe.

* You pronounce it something like 'Skarv-een nah Goo-ock'.

Published on May 15, 2017 07:34

March 13, 2017

St Patrick's Day 2017: A Different Story.

Green flags, gold harps and shamrocks, dancing, drinking and celebration - the whole world will go green next weekend for the bearded bishop in the green robes with his fistful of shamrock and his gleaming golden crozier.

So this is the story...

Patrick approached the High King's fort at Tara, where the Druids stood by the chair of the High Kind. And every fire in Ireland was quenched that night. Because there was a low that no fire whould burn on the eve of the festival of Bealtine, when the druids themselves lit a fire to their pagan gods.'

'But Patrick came to the Hill of Slane and lit a fire there, and prayed for the people of Ireland. The druids saw the flames of his fire from the height of the Hill of Tara, and they spoke to the king and told him that Patrick should be killed. But Patrick came to the Hill of Tara, and he praised God there and told the High King of God's goodness. And the High King fell to his knees.'

'Then Patrick plucked a shamrock. It had three leaves on a single stem. And Patrick taught them the wonder of the Holy Trinity, that three persons existed in one God, truly distinct and equal in all things, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. And the druids were amazed and fell to their knees and worshiped God.'

Generations of Irish children grew up with that story, passed on from generation to generation, by firesides and in schools. And, annually, it was preached from the pulpit on March 17th, when we all leapt to our feet and chanted Hail, Glorious St Patrick ( ... DEER saint OV our isle ...). Usually followed by that other hymn, Faith of Our Fathers, ('... how SWEET would be thy childrens' FAY-ate, if DEY, like dem, could die for DEE-eee?) After which, having marched through the streets wearing shamrocks, we went home to devour sweets before the resumption of Lent. He was a great saint that way, Patrick. If you were Irish he'd sneak you a bit of chocolate behind God's back.

I remember the story of St Patrick from my first picture book, in which the green-robed bishop towered above the dark-faced druids with firelight behind him and the shamrock held aloft. Behind the druids the High King knelt by his carved throne. And behind the throne a man with a gold harp, with his head bowed, was holding the palms of his hands on the harpstrings to silence its pagan music, and accept the robust authority of a new regime.

But this year we may have to find a new one.

At home in Ireland, faced with new evidence of the vicious criminality of the Catholic Church and the stranglehold that it's had on our State institutions, we'll be asked to celebrate that overt and dangerous identification of Church with State, and of Christianity with Irishness.

In The US, Irish-Americans in Boston have already seen their St Patrick's Day parade threatened by the pernicious homophobia of the Trump administration, and, on March 17th, NYC will see 'Irish Stand', a rally to assert that anyone who supports Trump's travel ban has 'forgotten the Irish story'.

And all over the world, the 'greening' of rivers, symbolic landmarks and buildings will push the message of Ireland as a great place to be altogether, and the perfect destination in which to spend your holiday money.

Though, maybe less so if you're a woman of childbearing age. Or a refugee. Or someone desperately trying to discover whether the Church falsified official documents, buried your sibling in an unmarked grave, or trafficked him or her to America.

Meanwhile, on the hills and in the valleys of Ireland, the earth itself is going green. And this was the wonder celebrated by the druids. Because, for our pagan ancestors, the ritual fire kindled in darkness at the feast of Bealtaine symbolised the triumph of light over darkness, the return of seedtime, and the eternal need for balance.

They too gathered to celebrate with dancing and music, parades, religious rites and wild parties. But they needed no explanation of the concept of a triple-aspect deity. Their own vision both of springtime and balance was contained in the image of a triple-aspect goddess, the Maiden, the Mother and the Crone. She was memory and potential, childhood, maturity and old age.

Here in Corca Dhuibhne her name was Danú, which means Water. Elsewhere she has other names. But everywhere she brings health and balance to the universe and fertility back to the earth.

This St Patrick's Day it might be good to remember that the hallmark of authoritarianism is the desire to control and corrupt the stories of who we are and where we came from.

Dingle And Its Hinterland: People, Places and Heritage

Out April 2017 from The Collins Press.

So this is the story...

Patrick approached the High King's fort at Tara, where the Druids stood by the chair of the High Kind. And every fire in Ireland was quenched that night. Because there was a low that no fire whould burn on the eve of the festival of Bealtine, when the druids themselves lit a fire to their pagan gods.'

'But Patrick came to the Hill of Slane and lit a fire there, and prayed for the people of Ireland. The druids saw the flames of his fire from the height of the Hill of Tara, and they spoke to the king and told him that Patrick should be killed. But Patrick came to the Hill of Tara, and he praised God there and told the High King of God's goodness. And the High King fell to his knees.'

'Then Patrick plucked a shamrock. It had three leaves on a single stem. And Patrick taught them the wonder of the Holy Trinity, that three persons existed in one God, truly distinct and equal in all things, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. And the druids were amazed and fell to their knees and worshiped God.'

Generations of Irish children grew up with that story, passed on from generation to generation, by firesides and in schools. And, annually, it was preached from the pulpit on March 17th, when we all leapt to our feet and chanted Hail, Glorious St Patrick ( ... DEER saint OV our isle ...). Usually followed by that other hymn, Faith of Our Fathers, ('... how SWEET would be thy childrens' FAY-ate, if DEY, like dem, could die for DEE-eee?) After which, having marched through the streets wearing shamrocks, we went home to devour sweets before the resumption of Lent. He was a great saint that way, Patrick. If you were Irish he'd sneak you a bit of chocolate behind God's back.

I remember the story of St Patrick from my first picture book, in which the green-robed bishop towered above the dark-faced druids with firelight behind him and the shamrock held aloft. Behind the druids the High King knelt by his carved throne. And behind the throne a man with a gold harp, with his head bowed, was holding the palms of his hands on the harpstrings to silence its pagan music, and accept the robust authority of a new regime.

But this year we may have to find a new one.

At home in Ireland, faced with new evidence of the vicious criminality of the Catholic Church and the stranglehold that it's had on our State institutions, we'll be asked to celebrate that overt and dangerous identification of Church with State, and of Christianity with Irishness.

In The US, Irish-Americans in Boston have already seen their St Patrick's Day parade threatened by the pernicious homophobia of the Trump administration, and, on March 17th, NYC will see 'Irish Stand', a rally to assert that anyone who supports Trump's travel ban has 'forgotten the Irish story'.

And all over the world, the 'greening' of rivers, symbolic landmarks and buildings will push the message of Ireland as a great place to be altogether, and the perfect destination in which to spend your holiday money.

Though, maybe less so if you're a woman of childbearing age. Or a refugee. Or someone desperately trying to discover whether the Church falsified official documents, buried your sibling in an unmarked grave, or trafficked him or her to America.

Meanwhile, on the hills and in the valleys of Ireland, the earth itself is going green. And this was the wonder celebrated by the druids. Because, for our pagan ancestors, the ritual fire kindled in darkness at the feast of Bealtaine symbolised the triumph of light over darkness, the return of seedtime, and the eternal need for balance.

They too gathered to celebrate with dancing and music, parades, religious rites and wild parties. But they needed no explanation of the concept of a triple-aspect deity. Their own vision both of springtime and balance was contained in the image of a triple-aspect goddess, the Maiden, the Mother and the Crone. She was memory and potential, childhood, maturity and old age.

Here in Corca Dhuibhne her name was Danú, which means Water. Elsewhere she has other names. But everywhere she brings health and balance to the universe and fertility back to the earth.

This St Patrick's Day it might be good to remember that the hallmark of authoritarianism is the desire to control and corrupt the stories of who we are and where we came from.

Dingle And Its Hinterland: People, Places and Heritage

Out April 2017 from The Collins Press.

Published on March 13, 2017 06:00

February 28, 2017

The Mysterious Eggs

This year the last weekend before Lent brought snow on the mountain. We went walking on Sunday, along the bóthairín, where the rutted mud crunched underfoot, and on the beach, where the wind and the hailstones cut like knives. And when we came back, there on the windowsill was a mysterious box of eggs.

No note, and no indication of who had left them. Just eggs left by a neighbour, which often happens round here. Proper new-laid eggs, grubby and unequal in size, from which a tiny, downy feather may flutter when you open the box.

The box was a supermarket one, but that's often the way.

The box was a supermarket one, but that's often the way.

Today is Pancake Day - Shrove Tuesday, the last day before Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent. The fire is still needed in the evenings, but a bunch of daffodils, carried up from Jack's, fills the house with scent.

Pancakes aren't traditionally eaten in Corca Dhuibhne on Shrove Tuesday. Instead, people cooked a big meal of whatever they had in the house the night before Lent started, in preparation for the six weeks of fasting and abstinence before Easter. But tonight, the pancakes added to the scent of our daffodils, filling the house with the aromas of nutmeg, lemons and frying apples.

When Jack was young, Catholic weddings didn’t take place during Lent, so this was often a popular day for wedding, sometimes with the match being made the previous Sunday. A bride married on Shrove Tuesday had to take care to move all her belongings to her new home by midnight. Otherwise, she had to continue to live with her parents until Easter – even if her husband’s home was only across the road.

Round these parts, there was much mockery of unmarried men. Neighbours would threaten to round them up and send them off to the island of Skellig Mór where, traditionally, Lent began later and marriages could still be made.The oldest bachelor was supposed to captain the boat.

Round these parts, there was much mockery of unmarried men. Neighbours would threaten to round them up and send them off to the island of Skellig Mór where, traditionally, Lent began later and marriages could still be made.The oldest bachelor was supposed to captain the boat.No one remembers boats actually being sent off to the Skellig, though. Instead, after the horseplay, everyone went home to the fire and the huge meal.

We ate our pancakes with lemon and the fried apples, and there was a scatter of nutmeg in the batter mix, which definitely isn't traditional.

We ate our pancakes with lemon and the fried apples, and there was a scatter of nutmeg in the batter mix, which definitely isn't traditional. The happenstance of a timely gift left by a neighbour definitely is, though.

The happenstance of a timely gift left by a neighbour definitely is, though.*Latest book

Dingle And Its Hinterland: People, Places & Heritage is currently available for pre-order from online outlets.

Publication Date April 18 2017

Publication Date April 18 2017

Published on February 28, 2017 13:36

October 29, 2016

Home For Halloween

Halloween is the hag at the gate ...

... apples gathered from the garden ....

... onions hanging in the trees to dry ....

... and their nourishment combined to make spicy chutney.

It's toasted brack with butter and blackcurrant jam, eaten after long walks on shining October beaches ....

... and jelly snakes in a bowl in the porch, waiting for those who brave the hag and come knocking.

Visit The House on an Irish Hillside on Facebook

Published on October 29, 2016 07:25