Felicity Hayes-McCoy's Blog, page 3

June 16, 2016

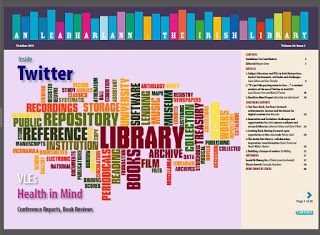

Libraries at The Edges of The World

The protagonist of my latest book is a local librarian called Hanna Casey and I’ve created a fictional county for her to live in. It’s on the south west coast - say somewhere between Cork, Kerry and Clare - Wild Atlantic Way country where the stunning scenery brings hosts of summer holidaymakers and the local council is bent on keeping the tourist numbers up.

We’re talking feelgood summer reading here, so Hanna starts out as a sad divorcee living in the back bedroom of her monstrous mother’s retirement bungalow, and ends up independent, re-empowered and reinvigorated, taking her time before taking the plunge into an affair with a younger man.

We’re talking feelgood summer reading here, so Hanna starts out as a sad divorcee living in the back bedroom of her monstrous mother’s retirement bungalow, and ends up independent, re-empowered and reinvigorated, taking her time before taking the plunge into an affair with a younger man. So far, so fictional. But as well as writing what in effect is pastoral comedy, I wanted to explore the realities of contemporary rural Irish life and the importance of focal points like library buildings and of the mobile services that bring library books to those who can't otherwise access them.

In my novel a scattered, dysfunctional community comes together to oppose the closure of its local library, the value of which hadn’t even been noticed until it came under threat. My characters’ belated awareness of the need to assert their own cultural requirements is a reflection of a growing concern in the real rural Ireland; how do you maintain a balance between branding and selling your locality as a tourist destination and maintaining it as a place where you yourself would want to live?

In the countryside, where a sense of isolation often results in high stress levels, local schools, post offices, libraries, police stations and social services are vitally important. Their absence or presence is barely noticeable to tourists who turn up for a few days in one place and then move on to the next. But, for the people who run the B&Bs and the boat trips, juggle farm work with shifts in call-centres, teach, keep shops, and own small businesses, they’re necessary for a healthy community life. They don’t, however, matter to a mind-set that sees the countryside as a sort of theme park in which the primary function of those who actually live there is to provide increasing streams of tourists with a dash of local colour.

That’s a view that makes sense if your sole concern is to thrust Ireland to the forefront of an aggressive global marketplace. But clearly there ought to be more to our thinking than that. In any given locality the actual point of seeking to increase tourist figures is the economic benefit that ensues if your efforts succeed. Local people work in local businesses. The local economy is what provides the option to build a desirable and viable future in the place where you grew up or have family roots. Here in Ireland having that option is still a significant matter; most of us over the age of forty can remember a time when emigration was the norm. You left because you had to, choice didn’t enter into it. And, in tourist areas at least, the spectre of emigration has never really gone away. A serious shift in exchange rates, one terrorist incident, even a couple of lousy reviews on TripAdvisor, and last year’s destination of choice can become this year’s wasteland.

That’s a view that makes sense if your sole concern is to thrust Ireland to the forefront of an aggressive global marketplace. But clearly there ought to be more to our thinking than that. In any given locality the actual point of seeking to increase tourist figures is the economic benefit that ensues if your efforts succeed. Local people work in local businesses. The local economy is what provides the option to build a desirable and viable future in the place where you grew up or have family roots. Here in Ireland having that option is still a significant matter; most of us over the age of forty can remember a time when emigration was the norm. You left because you had to, choice didn’t enter into it. And, in tourist areas at least, the spectre of emigration has never really gone away. A serious shift in exchange rates, one terrorist incident, even a couple of lousy reviews on TripAdvisor, and last year’s destination of choice can become this year’s wasteland. So rural Ireland knows that it has to keep ahead of the game. People adapt – brilliantly in most cases – rebranding what they have to offer in accordance with perceived fashion, and watching with eagle eyes for discernible trends. Foodie Breaks become Wellness Weekends; Walking Trips are resold as Adventure Experiences; and Cultural Tourism has knocked plain old Holidays into a cocked hat.

And nothing wrong with that, you might say. But if ‘cultural tourism’ is to be anything more than a cynical catch-phrase, the living culture of an area is just as important as a carefully-packaged version of its past. As voters, we empower central and local government to choose where to target our tax-spend. But we also need to consider the results of choices made on our behalf. How, for example, do we justify investing in a centre that interprets an area’s heritage for visitors if we fail to invest in the cultural future of those of us who actually live there?

Communities require focal points, and local libraries are a brilliant example of what that means in practice. Library buildings are centres for community information and venues for book clubs and other gatherings, as well as repositories of books and digital material. They’re cross-generational spaces serving groups and individuals from childhood to old age. They offer a portal to other libraries and resources via the internet. And if you’re isolated, housebound or suffering from rural Ireland’s lack of consistent broadband, their mobile library services provide physical links to the mother ships which can change people’s lives.

In fact, as a breed, local and community librarians ceaselessly challenge the constraints of isolation, and not only in the countryside. As an author who lives both in Ireland and the UK, I’m often in a position to admire their dedication and enterprise. London’s Hackney, for example, has a Telephone Book Club for housebound and handicapped readers whose age-range spans more than seven decades. According to Chris Garnsworthy, the librarian, the changing face of Hackney is increasingly affecting the club’s older members; their daycentre has closed, the local pub is boarded up, and the church has turned into six trendy flats. But by creating a new sense of community the book club’s existence has mitigated a damaging sense of dislocation.

The kind of change Chris describes is familiar here in Ireland, and maybe it’s inevitable. Indeed, there’s a case for calling it preferable to the ‘heritage’ approach that, for fear of losing their perceived attractiveness to tourists, refuses to allow rural communities to develop. But if change is important, so is continuity; and, if our tourist destinations are genuinely to thrive, so must the people who live and work and rear families in them.

Buy your copy of The Library at The Edge of The World here.

A version of this piece appeared in The Irish Times Culture Section June 8th 2016

A version of this piece appeared in The Irish Times Culture Section June 8th 2016

Published on June 16, 2016 07:04

Libraries at The Edge of The World

The protagonist of my latest book is a local librarian called Hanna Casey and I’ve created a fictional county for her to live in. It’s on the south west coast - say somewhere between Cork, Kerry and Clare - Wild Atlantic Way country where the stunning scenery brings hosts of summer holidaymakers and the local council is bent on keeping the tourist numbers up.

We’re talking feelgood summer reading here, so Hanna starts out as a sad divorcee living in the back bedroom of her monstrous mother’s retirement bungalow, and ends up independent, re-empowered and reinvigorated, taking her time before taking the plunge into an affair with a younger man.

We’re talking feelgood summer reading here, so Hanna starts out as a sad divorcee living in the back bedroom of her monstrous mother’s retirement bungalow, and ends up independent, re-empowered and reinvigorated, taking her time before taking the plunge into an affair with a younger man. So far, so fictional. But as well as writing what in effect is pastoral comedy, I wanted to explore the realities of contemporary rural Irish life. Not the version that comes with shamrocks, leprechaun hats, or even the excitement of a visit from Top Gear, but the actual downsides of living and coping with the goose that, at least at the moment, is laying golden eggs.

In my novel a scattered, dysfunctional community comes together to oppose the closure of its local library, the value of which hadn’t even been noticed until it came under threat. My characters’ belated awareness of the need to assert their own cultural requirements is a reflection of a growing concern in the real rural Ireland; how do you maintain a balance between branding and selling your locality as a tourist destination and maintaining it as a place where you yourself would want to live?

In the countryside, where a sense of isolation often results in high stress levels, local schools, post offices, libraries, police stations and social services are vitally important. Their absence or presence is barely noticeable to tourists who turn up for a few days in one place and then move on to the next. But, for the people who run the B&Bs and the boat trips, juggle farm work with shifts in call-centres, teach, keep shops, and own small businesses, they’re necessary for a healthy community life. They don’t, however, matter to a mind-set that sees the countryside as a sort of theme park in which the primary function of those who actually live there is to provide increasing streams of tourists with a dash of local colour.

That’s a view that makes sense if your sole concern is to thrust Ireland to the forefront of an aggressive global marketplace. But clearly there ought to be more to our thinking than that. In any given locality the actual point of seeking to increase tourist figures is the economic benefit that ensues if your efforts succeed. Local people work in local businesses. The local economy is what provides the option to build a desirable and viable future in the place where you grew up or have family roots. Here in Ireland having that option is still a significant matter; most of us over the age of forty can remember a time when emigration was the norm. You left because you had to, choice didn’t enter into it. And, in tourist areas at least, the spectre of emigration has never really gone away. A serious shift in exchange rates, one terrorist incident, even a couple of lousy reviews on TripAdvisor, and last year’s destination of choice can become this year’s wasteland.

That’s a view that makes sense if your sole concern is to thrust Ireland to the forefront of an aggressive global marketplace. But clearly there ought to be more to our thinking than that. In any given locality the actual point of seeking to increase tourist figures is the economic benefit that ensues if your efforts succeed. Local people work in local businesses. The local economy is what provides the option to build a desirable and viable future in the place where you grew up or have family roots. Here in Ireland having that option is still a significant matter; most of us over the age of forty can remember a time when emigration was the norm. You left because you had to, choice didn’t enter into it. And, in tourist areas at least, the spectre of emigration has never really gone away. A serious shift in exchange rates, one terrorist incident, even a couple of lousy reviews on TripAdvisor, and last year’s destination of choice can become this year’s wasteland. Rural Ireland knows that it has to keep ahead of the game. People adapt – brilliantly in most cases – rebranding what they have to offer in accordance with perceived fashion, and watching with eagle eyes for discernible trends. Foodie Breaks become Wellness Weekends; Walking Trips are resold as Adventure Experiences; and Cultural Tourism has knocked plain old Holidays into a cocked hat.

And nothing wrong with that, you might say. But if ‘cultural tourism’ is to be anything more than a cynical catch-phrase, the living culture of an area is just as important as a carefully-packaged version of its past. As voters, we empower central and local government to choose where to target our tax-spend. But we also need to consider the results of choices made on our behalf. How, for example, do we justify investing in a centre that interprets an area’s heritage for visitors if we fail to invest in the cultural future of those of us who actually live there?

Communities require focal points, and local libraries are a brilliant example of what that means in practice. Library buildings are centres for community information and venues for book clubs and other gatherings, as well as repositories of books and digital material. They’re cross-generational spaces serving groups and individuals from childhood to old age. They offer a portal to other libraries and resources via the internet. And if you’re isolated, housebound or suffering from rural Ireland’s lack of consistent broadband, their mobile library services provide physical links to the mother ships which can change people’s lives.

In fact, as a breed, local and community librarians ceaselessly challenge the constraints of isolation, and not only in the countryside. As an author who lives both in Ireland and the UK, I’m often in a position to admire their dedication and enterprise. London’s Hackney, for example, has a Telephone Book Club for housebound and handicapped readers whose age-range spans more than seven decades. According to Chris Garnsworthy, the librarian, the changing face of Hackney is increasingly affecting the club’s older members; their daycentre has closed, the local pub is boarded up, and the church has turned into six trendy flats. But by creating a new sense of community the book club’s existence has mitigated a damaging sense of dislocation.

The kind of change Chris describes is familiar here in Ireland, and maybe it’s inevitable. Indeed, there’s a case for calling it preferable to the ‘heritage’ approach that, for fear of losing their perceived attractiveness to tourists, refuses to allow rural communities to develop. But if change is important, so is continuity; and, if our tourist destinations are genuinely to thrive, so must the people who live and work and rear families in them.

Buy your copy of The Library at The Edge of The World here.

A version of this piece appeared in The Irish Times Culture Section June 8th 2016

A version of this piece appeared in The Irish Times Culture Section June 8th 2016

Published on June 16, 2016 07:04

May 1, 2016

Bábóg na Bealtaine: Mayday Ritual In Ireland

May Day, on May 1st, is celebrated throughout the northern hemisphere as the first day of summer. In Ireland the roots of the festival lie in ancient Celtic rituals held at the turning point between the seasons of Imbolc and Bealtaine.

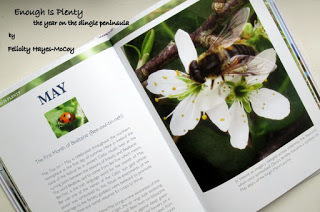

Here in Corca Dhuibhne May brings a new awareness of the garden. Each day, from first light, the air rings with birdsong. Nesting crows creak past overhead. Bees hum on blossoms and tiny, blood-red fuchsia buds shine against deep green foliage. One year behind the old byre I found flowers on a pear tree which, two years previously, we'd liberated from a supermarket. It had been a sad, dry stick with its roots wrapped in plastic. Now each year , as the sap rises, it promises baked fruit puddings flavoured with ginger and honey.

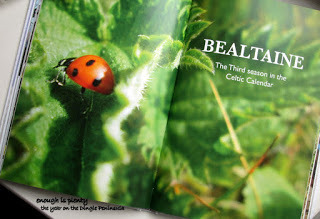

The word Bealtaine (Pronounced something like 'Bee-owl-tin-neh'), said to come from Bel Tine which means 'Bel Fire', is the Irish language word for the month of May. Bel was one of the names of the Celtic sun god whose power was symbolised by fire. Ritual re-enactments of his marriage to the fertility goddess Danú were believed to promote the sunshine and rainfall required for crops to thrive.

In Ireland, as imagery merged across milennia, the blossom which once symbolised Danú's fertility became a symbol, on May altars, of the Virgin Mary's purity.

The Celts' fertility goddess had three aspects, encompassing potential, fulfilment and death. She was the Maiden, the Mother and the Crone, an image of an optimistic world view which saw ageing as a vital stage in a cycle in which death leads to rebirth as inevitably as winter leads to spring.

In rural Ireland, within living memory, it was a May custom for girls to carry a doll, or bábóg (baw-bogue), decked in lace and flowers from door to door, singing to welcome the summer. It's a ritual as ancient as the worship of Danú, whom the bábóg originally represented. Schoolchildren here in Corca Dhuibhne sing the same song today.

"Bábóg na Bealtaine,

Maighdean an tSamhraidh,Suas gach cnoc isn. síos gach gleann,Cailíní maiseacha bán-gheala gléasta,Thugamar fhéin an tSamhraidh linn.

May-time Dolly,Maiden of Summer,Up each hill and down each glen,Girls dressed up in bright-white garments,We brought the Summer along with us."Enough Is Plenty: The Year on the Dingle Peninsula Visit my Author Page on Facebook

Published on May 01, 2016 04:43

April 22, 2016

The Big Walk

Ballyferriter April 22nd 2016. Preparing for the re-enactment of the Volunteers' march across the Conor Pass April 22nd 1916.

Ballyferriter April 22nd 2016. Preparing for the re-enactment of the Volunteers' march across the Conor Pass April 22nd 1916.

As the 1916 centenary commemorations continue, two things become increasingly evident. First, that the Dublin-centric version of Ireland's Easter Rising on which many of us were raised has obscured a far wider, national story. Secondly, how many personal stories have yet to come to light.

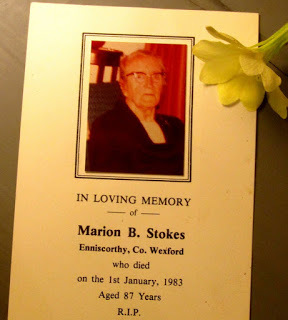

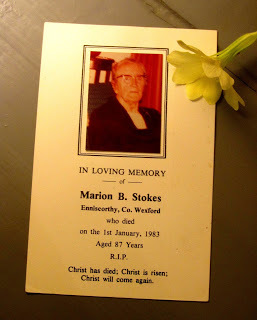

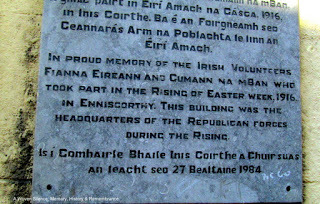

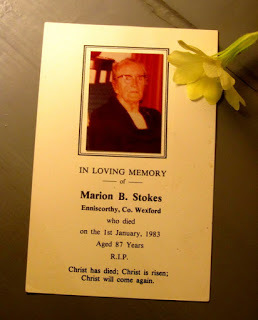

Marion Stokes. Cumann na mBan. Enniscorthy garrison Easter Rising 1916

Marion Stokes. Cumann na mBan. Enniscorthy garrison Easter Rising 1916My book A Woven Silence: Memory, History & Remembrance was inspired by a sense that I ought to know more about my grandmother’s cousin, Marion Stokes, one of three Cumann na mBan women who raised the tricolour over Enniscorthy’s Athenaeum in Easter Week 1916. County Wexford rose late, confused at first, like the rest of the country, by MacNeill’s order countermanding the rising, then responding to subsequent orders from the GPO to destroy the eastern railway approaches to Dublin. The Athenaeum garrison was the last to surrender, holding out stubbornly until its commanders were brought under a white flag to Kilmainham to receive personal orders from Pearse as Commander In Chief.

In writing the book – and as a result of responses to it I’ve received through social media – I’ve learned much about Marion and her comrades. I've also learned a great deal about how little most Irish men and women were taught about what happened outside the capital before, during and after Easter Week. The reasons for that ignorance are complex and, I believe, should be explored and understood as part of the centenary commemorations. It’s heartening, therefore, to see how many stories are emerging across the country.

On Easter Monday morning I was in Dublin, speaking about lost memories of the women of 1916 as part of RTÉ’s Reflecting The Rising. That afternoon I was in Enniscorthy where the Athenaeum has been beautifully restored for the centenary. This week I’m back in Corca Dhuibhne, in a stone house that was once home to a couple called Paddy Martin (An Máirtíneach) and Neillí Mhuiris Ní Conchubhair.

Neillí Mhuiris Ní Conchubhair and her brother James.I’ve lived here for fifteen years but it’s only now in the year of the centenary that I’ve found Neillí was a member of Cumann na mBan and that, on April 22nd 1916, Paddy, a fisherman, took part in a night march across the Conor Pass with over a hundred other armed Volunteers from the Gaeltacht and Dingle town. The weather was bad and the road worse and many of them reached Tralee barefoot. Their mission, though at the time they were unaware of it, was to liaise with Casement after the landing of the Aud, the ship on which he was bringing arms from Germany.

Neillí Mhuiris Ní Conchubhair and her brother James.I’ve lived here for fifteen years but it’s only now in the year of the centenary that I’ve found Neillí was a member of Cumann na mBan and that, on April 22nd 1916, Paddy, a fisherman, took part in a night march across the Conor Pass with over a hundred other armed Volunteers from the Gaeltacht and Dingle town. The weather was bad and the road worse and many of them reached Tralee barefoot. Their mission, though at the time they were unaware of it, was to liaise with Casement after the landing of the Aud, the ship on which he was bringing arms from Germany.In the 1960s personal statements were collected from surviving Gaeltacht participants in the march, all of whom had assumed they were marching to battle. They tell an extraordinary story of courage and physical resilience. Among them is one from Paddy who remarks, almost in passing, that he and a companion undertook the forty mile trek to Tralee after a sleepless night out fishing off Ard na Caithne.

When one of the men who set out to cross the Conor Pass was warned that he might not return he replied philosophically: ‘más é ár lá é, ‘sé ár lá é’- ‘if it’s our day, it’s our day’. But in the event, Casement was captured, the Aud with its cargo of arms was scuttled and Robert Monteith, who had accompanied Casement from Germany, brought the news to Tralee where the men of West Kerry were waiting. It was the discovery of the loss of the Aud that precipitated MacNeill's order to postpone the rising. And as Pearse and others frantically made plans to go ahead anyway, those who had gone on An tSiúlóid Mhór (The Big Walk) returned from Tralee to Dingle on a train commandeered by their captain.

It’s easy to forget that throughout Ireland similar Volunteer and Cumann na mBan companies were ready and prepared to rise during Easter Week, and that the fact that they didn’t doesn’t change the fact that they’re part of the 1916 story.

As with the story of Marion Stokes and her companions in Enniscorthy, An tSiúlóid Mhór has never had a place in the wider national consciousness. But today members of the families of the men who made that march are re-enacting it on foot, starting from An Buailtín, Baile ‘n Fheirtéaraigh. When they gathered this morning they were joined by girls from the local school and others, and the beginning of the long march over the mountain was accompanied by pipers and other musicians. A hundred years ago the local Volunteers gathered on a nearby beach and made their way to join their comrades in Dingle in secret.

An Buailtín April 22nd 2016

An Buailtín April 22nd 2016

An tSiúlóid Mhór April 22nd 2016

An tSiúlóid Mhór April 22nd 2016 Among those who attended the preparations for the re-enactment wearing their families' 1916 medals was the nephew of Mary Sheehy (Mold) of Baile Eaglaise who, like her neighbour Neillí here in Corca Dhuibhne and Marion in Enniscorthy, was only in her teens when she joined Cumann na mBan. During the War of Independence that followed the Rising, Mary Sheehy and other Cumann na mBan members all over Ireland acted as a network of support for their male companions in arms. Gearóid Mac an tSíthigh, Mary's nephew, said he was there to make sure she was remembered.

An Buailtín April 22nd 2016

An Buailtín April 22nd 2016

An Buailtín April 22nd 2016

An Buailtín April 22nd 2016 Mary Sheehy's Cumann na mBan medals As I'm typing this the marchers are on the road to Dingle.

Mary Sheehy's Cumann na mBan medals As I'm typing this the marchers are on the road to Dingle.Tonight they'll cross the Conor Pass.

And in a Gaeltacht area where the oral tradition still flourishes the story of An tSiúlóid Mhór will be remembered and passed on as integral to the story of the Rising.

Visit my Author Page on Facebook

Published on April 22, 2016 08:10

April 5, 2016

Book Promotion in Springtime

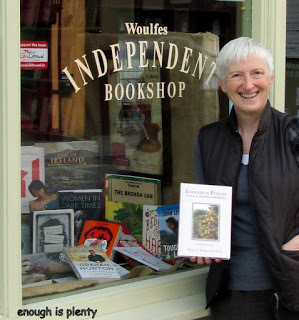

Book promotion in Dingle can be more complex than you might expect.

Especially if you grow spuds.

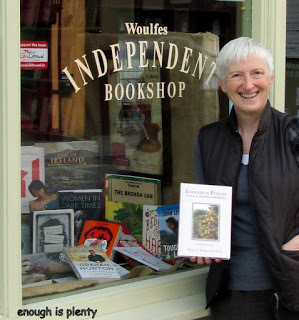

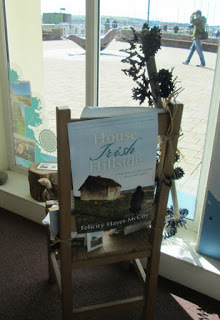

Last year the tourist office in Dingle town offered me a window display to advertise The House on an Irish Hillside and Enough Is Plenty.

We put a kitchen chair, some posters, a couple of copies of the books and a pile of promotional postcards in the back of the car, added a twist of oat straw and a spade from the shed and drove them into town.

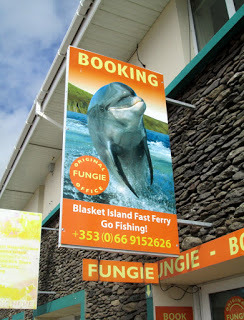

The lovely staff at the tourist office gave us a corner window facing onto the pier, right by the office where you book trips to visit Fungie ....

... and right through the year book lovers have paused to peer through the glass or come in to pick up a postcard and be told which shops in the town will sell them my books.

Then today I dropped into a friend's restaurant in Green Street ...

... and suddenly I realised Spring has arrived.

Her restaurant interior has been relaid out and redecorated. Her cards and menus are being planned and designed ...

.... everything's being set up for great days and nights of great food, drink and hospitality in Fentons - and back home in our garden we need to start setting our spuds.

Our spade, however, is an integral part of our window display there by the statue of Fungie.

Drastic measures were required.

And that is why, if you visit Dingle's tourist office this season, you'll find an entirely new agricultural implement leaning against our kitchen chair in the corner window.

While the spade is being used to set the spuds.

Visit my Author Page on Facebook

Visit my Author Page on Facebook

Published on April 05, 2016 13:06

March 23, 2016

Reflecting The Rising

Somewhere in this photo are twenty year old Marion Stokes of Enniscorthy, her twenty four year old brother Tom and their fifteen year old brother Patrick. The Easter Rising of 1916 has just ended and along with their comrades in Cumann na mBan, The Irish Volunteers and Fianna Éireann, they're being marched out of Enniscorthy's Athenaeum, the last garrison in Ireland to surrender.

Marion, who was my grandmother's cousin, lived to be eighty seven. When my mother and aunts were growing up she was like a sister to them. I remember her well from my own childhood and she died when I was at university. While she was alive I never heard of her involvement in the 1916 Rising. According to my mother, she 'didn't like to talk about it.'

So I don't know the nuances of what drove Marion and her brothers to take up arms and fight for an independent Ireland. But I know that the Proclamation of Independence read out from the steps of the GPO in Dublin guaranteed equality for all citizens, whose loyalty it claimed. After the Rising Cumann na mBan, the women's organisation of which Marion was a member, reiterated its dedication to the idea of an independent State founded on the principle of equality for all. In the absence of memory, I must assume that equality was at least one of the aims for which Marion was ready to die.

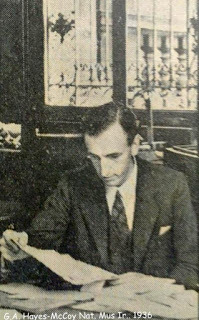

When he was working there in 1941, my father, who was a historian, curated the The National Museum of Ireland's first full-scale exhibition commemorating the 1916 Rising. He never spoke to me about Marion's involvement, though he knew her well and had advised her when she was involved in setting up a museum in Enniscorthy Castle in the 1960s. I visited that museum in my childhood. There was no reference there to her involvement in The 1916 Rising or to the fact that, with two other Cumann na mBan women, she had raised the tricolour over Enniscorthy's Athenaeum. As my mother said, she didn't like to talk about it.

Marion wasn't alone. Thousands of Irishwomen were involved in the cultural revival and the struggle for independence in the early decades of the twentieth century. Both Citizen Army and Cumann na mBan women rose with the men in Easter Week and hundreds of others across the country were prepared to join them. Very few of those women seem to have wanted to speak of it afterwards. Those who did spoke in voices that weren't heard, often because of State and Church censorship. And Irish historians of the period had much to deal with in terms of State control and manipulation of information.

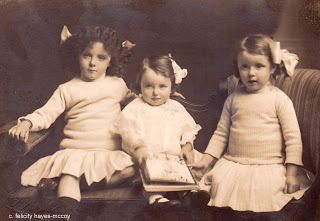

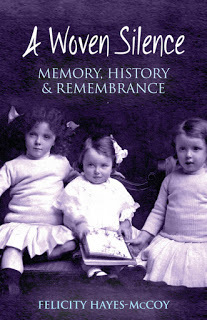

The children on the cover of my latest memoir are my aunts Cathleen and Evie and my mother. The State in which they and I grew up was not based on the principle of equality. Instead it was characterised by inequality, isolationism and censorship and by a web of lies, myths and denial about the complexities of the past.

The children on the cover of my latest memoir are my aunts Cathleen and Evie and my mother. The State in which they and I grew up was not based on the principle of equality. Instead it was characterised by inequality, isolationism and censorship and by a web of lies, myths and denial about the complexities of the past.Since then Ireland has moved on. In the centenary celebrations and commemorations of the 1916 Rising this coming weekend women's voices will be heard as loudly as men's, and women's role in Rising will actively be recognized. Yet it's worth noticing that, even now in the year of the centenary, the fact that three women raised the flag over Enniscorthy is hardly spoken of.

I don't know how Marion felt and thought as Easter week approached a hundred years ago. She could have told me. She may have told my mother. I don't know. I don't know if she and my grandmother, whose image appears on the spine of A Woven Silence, ever talked about it either. I know that my grandmother opposed The Rising. But she had three small girls to think about. Marion had little brothers and sisters, though. And after her mother died in 1917 while her brother Tom was imprisoned in England, she ended up raising siblings who blamed her for the tragic effect that The Rising had had on the whole family. Tom died too, only months after his mother, of tuberculosis contracted in Frongoch Prison Camp. Those may be some of the reasons why she didn't like to talk about it.

Lost stories like Marion's can never be regained and the fact that they were lost, by chance or by censorship, is something we need to remember.

Join me in Dublin on Easter Monday when, as part of RTÉ's 1916 Centenary event 'Reflecting The Rising', I talk about Family Memory and The Women of 1916

Join me in Dublin on Easter Monday when, as part of RTÉ's 1916 Centenary event 'Reflecting The Rising', I talk about Family Memory and The Women of 1916

Published on March 23, 2016 16:16

January 25, 2016

Rebel Women Betrayed

It was not as if I was unaware that Marion Stokes had been a member of Cumann na mBan, the women's militant nationalist organisation that took part in Ireland's Easter Rising in 1916. But along with that information came an unspoken sense that questions about it would not be welcomed. Marion, my grandmother’s cousin, lived to be 87 and died in 1983, so I could have had an adult relationship with her. But, as it happened, I didn’t. I left Ireland for London in the late 1970s. My mother often came to visit me and once, on a walk by the River Thames, she mentioned that though Marion had grown up in Enniscorthy and died there, she had spent time nursing in England. I remember asking why she left Ireland and my mother shaking her head and saying that she didn’t know. Marion, she said, “didn’t like to talk about the past”. I could well believe it. The Marion I knew in my childhood was not someone who would let her hair down, put her feet up and engage in girly chats. My mother said she had always been like that and I suppose that, when she told me so, I assumed it went with a lifetime of responsibility, starched aprons and hard work.

It was not as if I was unaware that Marion Stokes had been a member of Cumann na mBan, the women's militant nationalist organisation that took part in Ireland's Easter Rising in 1916. But along with that information came an unspoken sense that questions about it would not be welcomed. Marion, my grandmother’s cousin, lived to be 87 and died in 1983, so I could have had an adult relationship with her. But, as it happened, I didn’t. I left Ireland for London in the late 1970s. My mother often came to visit me and once, on a walk by the River Thames, she mentioned that though Marion had grown up in Enniscorthy and died there, she had spent time nursing in England. I remember asking why she left Ireland and my mother shaking her head and saying that she didn’t know. Marion, she said, “didn’t like to talk about the past”. I could well believe it. The Marion I knew in my childhood was not someone who would let her hair down, put her feet up and engage in girly chats. My mother said she had always been like that and I suppose that, when she told me so, I assumed it went with a lifetime of responsibility, starched aprons and hard work. Most of my teenage years were spent locked in silent conflict with my mother about everything and anything, but I had long conversations with her as an adult. In the years after my father died, she and I took several holidays together and many of the family stories she related come back to me now coloured by the sound of waves slapping against the prow of a Rhine boat or the scent of salt and wildflowers on a high cliff on one of the Scilly Isles. I wish now that I had asked her more questions about Marion. But I doubt that I’d have got more answers.

When I was a child my favourite season was autumn. My mother’s favourite was spring. I once asked her why that was so, and she told me that she loved its sense of expectation. The memory of that conversation still touches me and leaves me faintly angry, because she was one of a generation of Irishwomen whose legitimate expectations for herself and for her children were betrayed.

In the absence of written or oral record I cannot be certain what exactly caused 20-year-old Marion Stokes to go out and fight in Easter Week 1916, when she was one of the three women who raised the tricolour over the rebel headquarters in Enniscorthy town. Her primary motivation may have been nationalist, feminist, political or purely cultural. In the absence of memory I am left with inference. But two things I do know. One is that the Proclamation of the Irish Republic issued at the outset of the 1916 Rising “claims the allegiance of every Irishman and Irishwoman” and “guarantees religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens”. The second is that a statement issued afterwards by Cumann na mBan asserted that by “taking their place in the firing line and in every other way helping in the establishment of the Irish Republic” its members had “regained for the women of Ireland the rights that belong to them under the old Gaelic civilisation, where sex was no bar to citizenship, and where women were free to devote to the service of their country every talent and capacity with which they were endowed”.

That reference to “old Gaelic civilisation” is questionable: it ignores, for example, the fact that for centuries, if not millennia, native Irish society, like many others, used slaves of both sexes as units of currency. But, setting aside bad history and concentrating on political aspiration, it seems fair to assume that Marion and her companions, male and female, were prepared to sacrifice their own lives to secure a state founded on the principle of equal rights and opportunities regardless of gender. Yet I grew up in a state with a constitution that declared the proper aspiration of women to be marriage, our proper function to be child bearers, and our proper sphere the home.

That constitution, drafted for – and to a large extent by – Éamon de Valera, who had been a leader of the Rising, passed into law in 1937. So in only 25 years the aspirations of 1916 had been eroded to the extent that the rights of half of the State’s citizens were reduced. And that is the terrible part. When one section of society effectively becomes second-class citizens, the balance and health of the community as a whole are affected. Among the visible results in Ireland were levels of state-sanctioned institutional brutality which have only recently begun to emerge. Another was the fact that my mother, along with thousands of women of her generation, was told that marriage should be her highest aspiration, childrearing her only creative outlet, and that economic dependence was her civic duty. That in its turn produced levels of misogyny, emotional sterility and civic immaturity still evident in Ireland today.

Many women protested in public and in private during the drafting of de Valera’s constitution. The Irish Women Workers Union many of whose members had been involved in the 1916 Rising, expressed outrage; a letter from the secretary to de Valera, quoting the clauses which referred to the position of women, said: “it would hardly be possible to make a more deadly encroachment upon the liberty of the individual”. But by then women no longer held significant positions of influence in Ireland. The constitution was accepted. And a combination of revisionism and isolationism in the years that followed left the majority of Ireland’s citizens ignorant of the legacy we had been denied. And as I write this now, Irish citizens are still protesting about gender inequality, homophobia and the denial of Irishwomen’s basic human rights. Yet, in theory at least, the battle for equal rights was fought and won in Ireland 100 years ago.

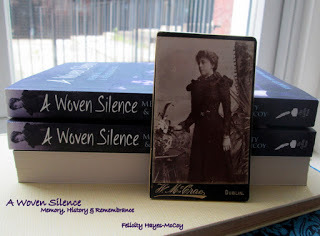

That anomaly, the mixed messages of the Ireland in which I grew up in the 1960s and ’70s, and the knowledge that the rights for which my grandmother’s cousin Marion was ready to die were denied to my mother’s generation and my own, all inspired my book A Woven Silence: Memory, History & Remembrance. The silence surrounding the aspirations of the women who took part in the early political life of the Irish state did not come about by accident: though, as the title of my book implies, its genesis was complex. As the centenary bandwagon lumbers up to the starting line, we should examine that complexity and take steps to counteract its continuing pernicious effect on contemporary Ireland.

The children whose photo appears on the cover of A Woven Silence are ( l to r) my aunts Cathleen and Evie and my mother May.

The children whose photo appears on the cover of A Woven Silence are ( l to r) my aunts Cathleen and Evie and my mother May.A version of this piece appeared in November 2015 in The Irish Times.

Published on January 25, 2016 14:13

November 28, 2015

Memory, History and Remembrance

In my mind I'm climbing a winding stair. The steps are cold and worn, and the only light comes in through narrow windows. I'm touching the curved wall with one hand, and with the other I'm hanging on to Marion's skirt. She is formidable and elderly, square and calm in her tweed coats and skirts, neat shirt-blouses and sensible shoes. Looking back now, I remember that day in Enniscorthy Castle. I was about nine years old. I remember her black leather handbag which always contained a white cotton handkerchief, and the fearsome bottle of Mercurochrome she used as an antiseptic to treat childhood cuts.

I never knew that in her teens she was a revolutionary, trained in arms and ready to fight and die for Ireland's independence in the Easter Rising of 1916.

A year after I finished university I left my home city of Dublin for London. My mother often came to visit me there and once, on a walk by the River Thames, she mentioned that though Marion had grown up in Enniscorthy and died there, she had spent time nursing in England. I remember asking why she had left Ireland and my mother shaking her head and saying that she didn't know. Marion, she said, 'didn't like to talk about the past'. I could well believe it. The Marion I knew in my childhood wasn't someone who would let her hair down, put her feet up, and engage in girly chats. She carried an air of authority and you didn't wriggle when she reached for the Mercurochrome. It was not as if I was unaware that she had been a member of Cumann na mBan. But along with that information, absorbed in my childhood, came an unspoken sense that questions about it wouldn't be welcomed.

And so, although Marion lived to be eighty seven and died in 1983, when I could have had an adult relationship with her, I never heard her story. Like so many Irishwomen of her generation, she remained silent about her experience during the Rising and afterwards. And, like so many Irishwomen of my mother's generation and my own, I grew up with a cultural, social and political inheritance which, in the hundred years since the the Rising, has fostered misogyny, lack of communication and a lack of powerful female role models, both in Irish politics and society.

Last month I visited Enniscorthy Castle again, to take part in an RTÉ television documentary which begins Ireland's national broadcaster's 1916 Centenary programming. I was speaking about my recent book A Woven Silence: Memory, History & Remembrance, which maps my own family's stories onto the story of the founding and development of the Irish State. In an early draft of the book its working title was 'The Absence of Memory' and, among other themes, it explores that silence with which I grew up.

The documentary, the first of a series of four called Ireland's Rising is a powerful piece of television and, as its trailer (link below) shows, it celebrates the beginning of a new era of awareness, discussion, debate and exploration of Ireland's national identity and values.

I hope that the emphasis that Marion Stokes and her comrades placed on equality as the basis for a healthy society will form a central aspect of that debate. And I'm heartened by the fact that the children in this programme seem to believe that it should.

Ireland's Rising. Episode 1. Trailer

Buy your copy of A Woven Silence here.

Buy your copy of A Woven Silence here.

Published on November 28, 2015 05:39

September 5, 2015

Memory and Potential

To the Celtic ancestors of peoples who now live all across Europe, the in-between spaces between one season and another were taut with energy. They were the points of balance between memory and potential, when the belief that all things contain all other things was expressed in communal ritual.

This is the season of Lughnasa when the wheel of the year turns again and the world prepares to enter the months of darkness which we see as cold and dead and the ancient Celts saw as pregnant with new life. It's a time for gathering in, for celebrating life and expressing mutual support.

The ancient Celts' rituals were held in in-between places - on beaches between land and sea, on mountain tops between earth and sky, and on water which is the basic necessity for life.

Here in Corca Dhuibhne memories of those ritual gatherings are still to be found at Lughnasa. All around the peninsula boat races are held, in which crews from the different communities pit their skills against each other.

On a beach near Ballyferriter called Béal Bán, a name that translates as The White Mouth, horse racing echoes the ritual races once held in honour of Lugh, the Celtic sun god.

To the ancient Celts everyone and everything in existence was interdependent because everything in the universe was sentient, and shared a living soul. The emphasis on community in their seasonal gatherings expressed the place of the individual within that worldview. And their annual celebrations of Lugh's union with Danú the Earth Mother expressed their belief in the interconnectivity of the universe in terms of the human family.

Tomorrow, on Béal Bán when the tide is out, the drumming of horses' hooves will echo the ancient communal gatherings at which drumming and dancing promoted a world of harmony and balance.

Races at Lughnasa are life-enhancing family celebrations. Whole communities gather on the beach; mums and dads, babies and adolescents. People of all generations participate in the contests, lay bets on outside chances, make music, share stories, eat ice-cream or just hang out.

And this year, on other beaches in other parts of Europe, individuals and families who have been torn from their communities are also experiencing in-between spaces, praying for a restoration of balance, and giving thanks for life.

https://www.facebook.com/helpforhumansireland?fref=ts

https://www.facebook.com/events/1047978998546751/

This is the season of Lughnasa when the wheel of the year turns again and the world prepares to enter the months of darkness which we see as cold and dead and the ancient Celts saw as pregnant with new life. It's a time for gathering in, for celebrating life and expressing mutual support.

The ancient Celts' rituals were held in in-between places - on beaches between land and sea, on mountain tops between earth and sky, and on water which is the basic necessity for life.

Here in Corca Dhuibhne memories of those ritual gatherings are still to be found at Lughnasa. All around the peninsula boat races are held, in which crews from the different communities pit their skills against each other.

On a beach near Ballyferriter called Béal Bán, a name that translates as The White Mouth, horse racing echoes the ritual races once held in honour of Lugh, the Celtic sun god.

To the ancient Celts everyone and everything in existence was interdependent because everything in the universe was sentient, and shared a living soul. The emphasis on community in their seasonal gatherings expressed the place of the individual within that worldview. And their annual celebrations of Lugh's union with Danú the Earth Mother expressed their belief in the interconnectivity of the universe in terms of the human family.

Tomorrow, on Béal Bán when the tide is out, the drumming of horses' hooves will echo the ancient communal gatherings at which drumming and dancing promoted a world of harmony and balance.

Races at Lughnasa are life-enhancing family celebrations. Whole communities gather on the beach; mums and dads, babies and adolescents. People of all generations participate in the contests, lay bets on outside chances, make music, share stories, eat ice-cream or just hang out.

And this year, on other beaches in other parts of Europe, individuals and families who have been torn from their communities are also experiencing in-between spaces, praying for a restoration of balance, and giving thanks for life.

https://www.facebook.com/helpforhumansireland?fref=ts

https://www.facebook.com/events/1047978998546751/

Published on September 05, 2015 10:38

June 30, 2015

The Dublin Table

First there was the Galway chair. There was a family story that it was made as a wedding present. I don't if that's true. I know that it once stood in my grandfather's home in Galway, in a room above his barber's shop in Eyre Square. I know that, when the shop was sold after his death, it came to Dublin with my grandmother, a charming, angry woman, who took to her bed on arrival and stayed there, in a temper, till she died.

I know that when I was born, my father shortened the legs so my mother could use it as a nursing chair.

I remember kneeling in front of it when I was five, playing house; I put a pastry board across the arms as a roof, and tucked my teddy to sleep on the seat.

When my mother died it went from our house in Dublin to my brother's house in Enniscorthy. On the twenty fifth anniversary of my own wedding I asked him if I could have it as an anniversary present and it crossed the the country again, from Wexford to Corca Dhuibhne

As I worked down through the layers of paint that had accumulated on it, the memories blurred and refocused. The top layer was white. That was put on by my brother after my mother's death. Beneath it, was a layer of Wedgewood blue. That went on when my father died. I remember my mother, alone in the home they had made together, afraid that even to change the colour of a chair was somehow to betray his memory. Underneath the layers, a creamy undercoat clung to the spindles and the seat, and needed digging out of the legs. I worked on it for months, revealing the knots and scratches, the marks of other, older tools, and the colours and grains of the different woods chosen by the man who made it. Beneath it I found the initials of his name.

Under the steady, repeated gestures of chipping and sanding, turning and dusting, my mind played with ideas for a new book. That was two years ago. Now the book is written and the Galway chair has been joined by the Dublin table.

It was made by a man who worked as a joiner in Ireland's National Museum. There's a family story that he used offcuts of timber from a display case. My father, who also worked in the museum, had responsibility for its Military History and War of Independence collections. The table was built for him to write on, though I never remember him working at it. I don't think it would have been big enough for his manuscripts and books.

At different times it stood against different walls in our Dublin house. I remember rubbing Ronuk Polish into its mahogany surface and buffing it with a pad made from a worn cotton sheet. There was a pewter bowl of oranges that always stood on it at Christmas time. My mother guarded table top carefully against heat marks, scratches and stains.When she died it went to my sister's house. When my sister died and that house was sold, her husband offered it to me.

Yesterday Wilf and I drove from Dublin to Corca Dhuibhne with the table in the back of the car. The day before that we had been in Enniscorthy, talking about the book, which I've just finished editing. It's called A Woven Silence: Memory, History & Remembrance and it maps my own family's stories onto the history of the Irish State, seeking and exploring blurred communal memories and the reasons why they were lost.

The cover shows a photo of my mother and her sisters taken in Dublin about 1915, when their father's cousin was in the British Army, fighting in Flanders, and their mother's cousin was drilling in the fields outside Enniscorthy with Cumann na mBan. In my mother's clenched hand is a coin. The memory of its story would have been lost forever had she chosen not to pass it on.

The cover shows a photo of my mother and her sisters taken in Dublin about 1915, when their father's cousin was in the British Army, fighting in Flanders, and their mother's cousin was drilling in the fields outside Enniscorthy with Cumann na mBan. In my mother's clenched hand is a coin. The memory of its story would have been lost forever had she chosen not to pass it on.As I reached the last chapter, I told my publisher that I couldn't finish writing the book till the marriage referendum was over. It ends with Pantibliss on the stage of the Abbey Theatre, crowds singing in the yard of Dublin Castle, and three faceless stones on an Enniscorthy hill.

Yesterday Wilf unscrewed the table top, so we could fit it into the car. Sixty years earlier, a man whose name I don't know fitted those ten screws, each an inch and a quarter long, into place, and fastened the top to the base. They came out easily when Wilf turned the screwdriver, having been put in with no more pressure than was required to do the job right.

We carried the Dublin table into the house in Corca Dhuibhne in two pieces and reassembled it on the floor. Now it stands here beside the Galway chair. I don't know what will happen to either of them next.

A Woven Silence: Memory, & Remembrance will be published by The Collins Press in September 2015

Published on June 30, 2015 15:21