Rudy Rucker's Blog, page 38

December 24, 2012

Fun Boschian Nurb Scene from BIG AHA

Some fun reading for the holiday week, a new passage from my novel in progress, The Big Aha.

A half hour later, the five of us were riding up a curving nurb-grass driveway in Glenview—me, Dad, Loulou, Joey and Rikki—with our spooked roadspiders staring up towards the Roller mansion. Unlike its half-timbered, white-brick, or columned plantation-style neighbors, the Roller home was modeled on a Norman castle, with immensely high battlements of yellowish stone. The walls were pierced by diamond-paned windows and corniced slits. Decorative turrets sprang from each turning of the walls, and a substantial master tower rose beside the arched entrance. Besotted by old movies, Mr. Roller’s father had built the place in the 2020s.

A great, jellyfish-like nurb hovered above the mansion, tethered to the pointed peak of the high tower. The flying jellyfish was what we called a laputa—iridescent and the size of a small house, with well-appointed staterooms on the lower level. The jellyfish nurb had hydrogen-filled bladders on its upper level, and dangling tentacles below. A cluster of the tentacles led to the tower.

“Kenny lives in the laputa,” said Joey.

“I know all about it,” I said. “Kenny had Jane and me up there for dinner a few months back. Him and his boyfriend Kristo. Kenny got wasted and pretended he was going to push me out through a porthole. Only he wasn’t really pretending. He’s always been a jerk. I don’t know how Kristo puts up with him.”

“I’ve seen Kenny,” interposed Loulou. “He’s handsome. That counts for a lot. If you’re a handsome jerk, you’re romantic and damned. If you’re an ugly jerk—forget it.”

A rock thudded into the ground beside us, then another and another. The roadspiders made herky-jerky evasive moves. Joey lost his seat and fell to the ground. The seeming rocks uncurled to become many-legged gray scuttlers—overgrown versions of those woodlice or pillbugs you find in rotting leaves. A hundred meters above us, a maniac laughed.

“I hate you, Kenny!” screamed Joey, shaking his fist. The pillbug nurbs were staring at us with bright eyes—sending our images to Kenny.

“Come on up!” called Kenny from above. His head was a small dot in one the jiggling laputa’s windows. “Brunch time! Bloody Marys! I see Joey, Loulou, Zad, Mr. Plant, and—who’s the geek girl?”

We left our roadspiders in the stable beside the mansion. Dad walked back down the hill to visit with Weezie Roller in the gate house, a solid red-brick affair with a gray slate roof. I led the others up the steps to the manor. The nurb lock on the great doors recognized me.

In my boyhood the Roller castle’s interior had been pure old-school, with walnut wainscoting, ornately patterened glass panels, hanging brass lamps, tile or parquet wood floors, and oriental carpets. Over the years Mr. Roller had added a mad hodgepodge of upgrades. Given that he’d expanded his business from producing nurb chow to marketing actual nurbs, he had access to the latest and greatest nurbs being made. And so, over wife Weezie’s and daughter Jane’s objections, Mr. Roller had evolved the mansion’s interior into a bizarre and bustling nurb habitat. Son Kenny had been all for it.

Right in the front hall, a large leathery nurb armchair had given birth to a litter of four-footed baby chairs. They scampered away from us into the parlor, their woody legs pattering on the yielding flesh of a living rug. A nurb chandelier thrust a pair of brassy stalks around a corner, peering at us with dim eyebulbs.

At the far end of the hall lay a mound of busted-open Roller nurb chow bags. I supposed Kenny and Kristo—or their choreboy nurbs—were hauling in chow to keep the menagerie alive. Our three pillbug nurbs scooted past us towards the food. Their overly numerous feet made an unpleasant skritchy sound.

I saw a hungry nurb teapot on the mound of chow, rooting with its spout. A bendy grandfather clock used its pendulum like a tongue. The newborn leather chairs were rooting into the food, as were a clutch of slithering rugs. A fat couch had bellied up beside them, gobbling chow with a toothy mouth beneath its plump arm. A weathered pair of pants was feeding as well, and a pair of table lamps fluttered over, their shades pulsating against the air.

“Like jungle animals at a watering hole,” said Rikki. “And look at the tendrils running down from the ceiling. It’s covered with some nurby growth up there. Colored fungus?”

“Old Weezie was mad when they put on that stuff,” I said. “Mr. Roller had always wanted a fancy coffered ceiling like in the lobby of the Brown Hotel downtown. A 1920s movie theater look, you wave, with embossed squares and polychrome flowers and cartouche scenes of dancing nymphs. He got some hairball at United Mutations to design a nurb lichen that was supposed to emulate all that. But it’s not even close.”

“Qrude,” said Joey, his head thrown back. “The shapes are layered onto each other in sequences—like the motion trails you see when you’re really high. Like a 3D scribble.”

“I wave the pungent colors,” added Loulou. “Looking at them hurts my sinuses almost. For sure I’d wear a dress like that.”

“Mrs. Roller got all worried that spores were drifting down from the ceiling and poisoning her food,” I said. “That’s when she moved down to the gate house. And a year after that out, Mr. Roller died. So maybe she was right about the spores. Jane said Mr. Roller had this sick rash on his back. She said daffodils and shamrocks?”

“Don’t want to think about that,” said Rikki. “If we move in here, I’ll slap together some annihilator nurbs to clear off that crap. Banzai beetles and cannibal squid. Meanwhile let’s climb that tower. I mean—if you guys really do want to visit with Kenny?”

“Might as well get it over with,” I said. “He’s a key player here.”

Leaving the spying pillbugs behind, we ascended three flights of stairs. Each of the manor’s levels had its own peculiar fauna.

The second floor had held the bedrooms, and was now a dimly lit jungle of wiry bedspring vines, with hairbrushes and hankies flitting through the tangled thickets like little birds. Rabbity pillows foraged in the undergrowth, and beds lolled like cows. A pair of tattered humanoid sex nurbs were back there as well, their faces frozen in vegetal leers.

In pre-nurb days the third floor had held Jane and Kenny’s play rooms. Weezie Roller had tended an eccentric vegetable garden up there as well. I saw some of the expected horror-movie-type talking toys, also two competing tribes of nurb vegetables: the carrots versus the beets. The carrots sped about like hyperactive inchworms; the beets ricocheted off the walls. They bore healthy tufts of leaves, and vied at pressing their foliage to the sunny windows. They rooted in some old troughs of dirt as well.

Nurb disks were buffing the wooden floors, and long-legged feather-dusters cleaned the wandering tables and chairs. A steady stream of toy soldiers were using a little planes to ferry in nurb chow from below.

The final flight of stairs led into the small tower room—only a few yards across and crowded by the slimy roots of the hovering laputa. The tendrils writhed like a dish of living spaghetti, feeding on yet another stash of Roller nurb chow. Several of the strands displayed eyestalks. Kenny’s laputa was observing our arrival.

“Hop on,” blubbered a slit mouth in one of the laputa’s thicker tentacles. “Free ride.” The thick tentacle’s flesh flowed and formed holes in itself, making a column of four seats just inside one of the tower’s large open windows. Not letting ourselves think about it too much, Loulou, Joey, Rikki and I hopped aboard.

As if on a carnival ride, we were drawn out the window and up into the sky.

December 17, 2012

Fantasy and/or Science Fiction

This’ll be my last post of 2012. Lots of family coming to town, hooray.

We had a festive lunch at the Fairmont hotel in SF this weekend. Dig the Xmas tree reflected in the grand piano. “Why can’t it always be like this?” said one of our group.

My wife and I were out at the beloved Four Mile Beach north of Santa Cruz last week to look at the unusually low tide, a so-called “king tide.” The surfers were out in the water as usual, working the waves, finding new breaks. I always like to imagine that being a professional writer is a little like being a surfer—you’re out in the gnarl just about every day you can get the chance, taking the flows as they come.

My writing on my new novel The Big Aha has been going well for the last month or two. Unlike my customary practice—at least for the last few novels—I didn’t write up a detailed outline for this one. At the start of my career, I didn’t use outlines either. Back then I just dove in and trusted the muse, making it up as I went along. And now I’m back to that again. So far it’s fun—although eventually I’m likely to hit what Robert Sheckley called a “black spot,” which is when it becomes really hard to keep the story going.

When I get at all stuck, I like to invent semi-bogus explanations for whatever fantastic events I’ve already written in. The explanations themselves may impose constraints or they may open possibilities—in either case, this can lead to new scenes, sequences, and even subplots.

The picture above shows a room at the SF MOMA where there’s a special art installation on the floor this month. Black and white tiles, and as the artist’s crew laid the tiles, they used something like a coin-flip to randomly pick the color of each and every tile as they went along. Patterns emerge. We see things. We hear voices in the noise.

Just because I invent explanations doesn’t mean I’ll always think that they’re true, I mean not for the rest of my life. I do like to convince myself that my latest SF gimmicks are true for as long as I’m working on a story that uses them. “Profiting from” a delusion as opposed to “suffering from” one.

It’s maybe a little late for Xmas shopping, but you certainly ought to get a Turing & Burroughs for a New Year’s gift—if not for yourself then for one of your friends or relatives. Beatnik SF—today’s reader needs it special.

I read Murakami’s long novel 1Q84 this month and enjoyed it a lot. Certainly it could have been about a third shorter, but it kept me reading, and I became fond of the characters. And it had some nice fantasy/SF action in it. Murakami is one of us. Whoever “we” are.

The title is like 1984, but with a Q instead of the 9. The idea is that the main characters spend most of the novel off in an alternate timeline or in an alternate reality. So far as I can tell, Murakami is not an author who spends his spare time in figuring out logical and rigorous explanations for his worlds—complete with spacetime diagrams. He’s more on the “fantasy” end of our field, as opposed to being on the “science-fiction” end.

But that’s fine, Murakami’s book hangs together as well as it needs to, and it has a strong ending.

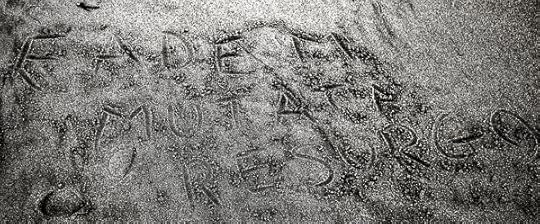

Out at Four Mile beach, I wrote, as I often do at the start of a novel, a favorite slogan of mine in the sand: EADEM MUTATA RESURGO. It means, “The same, yet altered, I arise again.” It was originally meant to be used as the epitaph for a mathematician who did some ground-breaking work on the nature of the so-called logarithmic spiral, the one that swoops out really fast like the exponentially expanding side of a snail shell. I’ve posted about this slogan several times,

Murakami’s 1Q84 inspires me to be looser than usual about the scientific logic in my Big Aha. At least I’m letting myself be be loose while I’m dreaming up scenes and writing them. Just let whatever seems interesting happen.

And then later, due to my SFish nature, I’ll skulk back and cobble up an explanation after all. No harm in this—as I say, the explanation will give me an idea for another scene. Like rainwater streamlines angling away from a gutter-stuck leaf.

I don’t think I’ve ever dreamed up a weird event for which I was unable to craft some kind of bogus explanation. Like taking a random squiggle and fitting it into a sketch of a realistic scene. That’s what it means to be a scientist, no? Rigorous logic.

Have a great holiday season, and all best wishes for 2013!

I’ll meet you in the heart of the Sun.

December 10, 2012

Cosmic Fairyland #2: The Third Eye.

In my current series of posts, I’ve mostly been discussing ideas for my novel in progress, The Big Aha. Recently I was been talking about a cosmic/robotic flip between two mental modes—see my October 24, 2012, post “The Two Mind Modes. Telepathy.” I’ll quote a bit of that post here as a reminder:

Open your (inner) eyes to your true mental life. Your state of mind can evolve in two kinds of ways that I’ll fancifully call—“robotic” and “cosmic”. The “robotic” mental processes proceed step-by-step—via reasoning and analysis, by reading or hearing words, by forming specific opinions. Every opinion diminishes you.

The “cosmic” changes are preverbal flows. If you turn off your endlessly-narrating inner voice, your consciousness becomes analog, like waves on a pond. You’re merged with the world. You’re with the One. It can be a simple as the everyday activity of being alert—without consciously thinking much of anything. In the cosmic mode you aren’t standing outside yourself and evaluating your thoughts.

And in my post of December 7, 2012, “Cosmic Fairlyand #1: How To See It” I was talking about a fairy/mundane flip between two reality modes. It would clutter my Big Aha novel (and beggar common sense) if I were to claim that these are two distinct axes, two distinct kinds of flips.

But I can’t just say that cosmic mode and fairyland are one and the same. Because when you can go into the fairyland state you disappear from physical view, and in the merely cosmic state you’re still around. When you go to fairyland, you physically cross a gap between the two levels. You can get off the floor and glue yourself to the ceiling.

The “explanation” for the first flip, that is the cosmic/robotic mode flip in The Big Aha is that my characters get into a so-called quantum wetware state. And they have access to a so-called “gee-haw-whimmy-diddle” brain switch.

By the way, I can’t stand to keep using my character Gaven Garber’s stupid name: “the gee-haw-whimmy-diddle switch” throughout The Big Aha. I’ll have my character Loulou begin calling it “the third eye,” which is the name they used in my novel Spaceland.

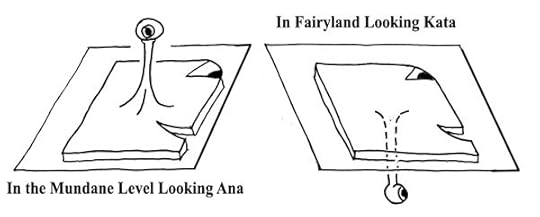

A 2D Flatland Character with a 3D Third Eye (from Spaceland). He can now see behind his wife and observe that she’s about to stab him.

So, as in Spaceland, we suppose that the third eye depends on an organelle that can stick up into 4D by a small amount. I’d considered having it be a macromolecule, but hell, let’s have it be bigger, like a lobster’s eye or crab’s eye on a short stalk. And we’ll say the gap between the mundane level and the fairyland level is fairly substantial, like maybe an inch. Forget about making it a mere atom’s width. I want some hyperthickness to maneuver in!

The third eye lives in your pineal gland of course. When the third eye is lifted or extended, you get unblocked access to a wider area—note that brainwave vibes pulse out into the full hyperthick space. With your third eye up on the alert, you can synch with more distant things. And that puts you into cosmic mode.

And—here’s today’s aha moment—if the third eye projects even more, if you really really stretch out the eye stalk, then your eye can bump into and adhere to the “fairyland” level of our hyperspace slab, and it can haul you up there, like a filament of web lifting a spider!

The 2D Being “A Square” with a 3D Third Eye Points Ana or Kata (from Spaceland)

Once you’re in fairyland, you can lie flat in it, or you can extend your third eye’s stalk back in the direction whence you came, as shown beloe. We’ll suppose that you can’t push the stalk out through the hyperspace box that contains our dual-level cosmos. I’ll explain about “ana” and “kata” in just a second.

In discussing the direction that the eyestalk points, it’s worthwhile to have words for the 4D correlatives of “up and down.” As in Spaceland, I’ll use “ana and kata,” following the writings of Charles Howard Hinton—see my June 8, 2009, blog post about Hinton.

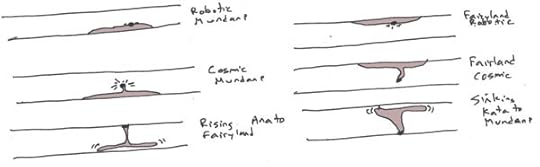

Mode: Eye Stalk: Body Is On:

Robotic Mundane retracted floor

Cosmic Mundane extended floor

Robotic Fairy retracted ceiling

Cosmic Fairy extended ceiling

Thus we have four possible modes. Your eyestalk can be extended, that is, pointing ana or kata into the hyperspace box of our space. Or it can be retracted, that is, fully contained within your body. As I already mentioned, when extending the probe, you need to push it ana when on the floor and push it kata when on the ceiling. And we get the four possibilities in our table because your body can either be ana on the “floor” or kata on the “ceiling.”

Cosmic, Mundane, Robotic and Fairy Modes

You might cycle through the four stages in the order shown in the figure above, jumping ana running down the left column and jumping kata running down the column on the right.

I’ll post more about these topics before too long, also I’ll want to say a little about the practice of inventing detailed explanations for SF/fantasy effects.

December 7, 2012

Cosmic Fairyland #1: How To See It.

I changed the name of the alternate world in my Big Aha book from “Gubland” to “fairyland.” I didn’t want to be fixated on the small green pig-like gubs that I posted about on November 30, 2012 in “Gubs and Raths.” Lots of other critters in fairyland besides gubs. I could also call the place Wonderland, but that’s too specifically the world of Lewis Carroll’s Alice.

In today’s post, I’m coming back to my post of November 28, 2012, “SFictional Higher Realities.” In that post I was wondering where to locate my alternate world of fairyland.

I’ve decided that fairyland is an unseen world that overlaps the mundane. Not a parallel world, closer than parallel. Not two sheets, one sheet. One world. We’re in fairyland all the time—if we notice.

There’s a tiny physical distance between here and there. That is, our 3D hypersheet of space has a miniscule hyperthickness, something on the order of the diameter of an atom. We slide around on the bottom, on the “floor,” and the fairylanders slide about on the underside of the “ceiling.” For this reason we can easily “move through” (that is, “sidle past”) each other, and we’re close to invisible to each other. In studying the drawing below, keep in mind that “ana” and “kata” are traditional words for the analogues of “up” and “down” in the direction of the fourth dimension along which our world’s hyperthickness lies.

[image error]

Admittedly the hyperthick model sounds very much like a two-sheets model with parallel worlds. But there’s a slight difference. In the two sheets model, you have a void of empty hyperspace between the two sheets. In the hyperthick model, you have two zones in one shared “room.” Particles can drift across from one zone to the other, and switching zones isn’t so difficult as switching sheets. Think of manta rays raising and lowering themselves within a very low-ceilinged cave.

Since we’re in one room, a certain amount of energy radiates out into the full hyperthickness of our space sheet, so we can faintly see fairyland if we try. And vice-versa.

Some entities—like hills and trees—reach through from the mundane to the fairy zones. So we have pretty much the same geography and landscape in the two zones. But things look different. The trees seem soft up there, they writhe and they talk. Our houses look like holograms over there, like shapes of light.

To go to fairyland, you jolt your worldview. You do a mundane/fairy shift. And suddenly everything looks fresh and new. Or incredibly strange. Jamais vu—“I’ve never seen this.” Maybe for a moment you can’t remember the ordinary names of things.

Let’s say fairyland is somewhat like in the old tales. Perhaps people told those stories for a reason; perhaps the tales encode a racial memory of some things that are actually true. Things appear and disappear. Odd doors lead into odd rooms. The darting creatures you see from the corners of your eyes are real.

Not that I want to be stuck having to do standard fairytale things, nor do I necessarily want to present the traditional cast of fairyland in any standard way. But I’d like to give the world a try. I’ve been reading the VanderMeers’ The Weird, a compendium of stories that are something like fairytales. But there’s no fixed setups being used in these tales, and each of them is fairly unique. The Hollywood/Tolkein-land hegemony needn’t be the only fairyland.

Stepping into fairyland, my character Loulou hears the horn of some hunters. They’re all angles and swords, like the face cards in a deck (à la Alice in Wonderland). They’re blowing the horn and crashing through the woods and getting closer. Like a fox-hunt and Loulou the vixen is the fox.

I was at the dentist the other day, and while I was being tormented in the chair, I managed to space out and imagine the room around me to be a fairyland scene. I wasn’t on any meds, not even novocaine—I was just doing a mental reality warp. Those colored tools in my mouth? Fairyland implements.

The mundane segues into fairyland when you study an ambiguous figure such as the duck/rabbit, the vase/faces, the crone/girl, or the reversing Necker cube.

I went for a ride on my bike today. I was hoping to find my way into fairyland, and at times I did. The trick is not to be worrying about my career or my duties or my fears or expectations. Instead I have to fully in the now. Marinating in wonder at the trees, wonder at the street signs with the arrows painted on the streets, wonder at the vehicles and bipeds to be seen.

Trying for jamais vu. ”I don’t know what I’m looking at. There is no I. Only these sights, and this body, pedaling.” As with any meditation practice, I repeatedly fell away from the vision, dropping from fairyland down to the mundane. But then I’d remember and go there again. Losing myself in the clouds.

Coming up in “Cosmic Fairyland #2: The Science.” —- A scientific model for my conception of fairyland, explaining how it fits in with my distiction between the cosmic and robotic mental modes.

November 30, 2012

Gubs and Raths

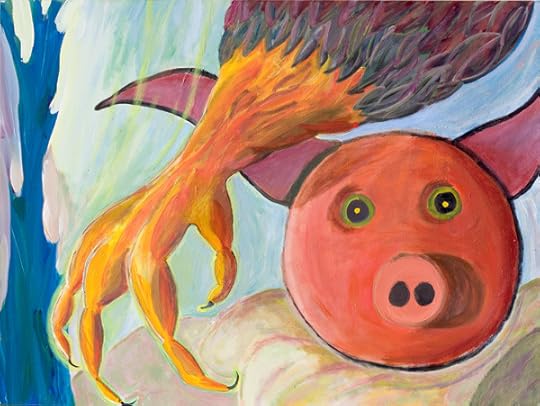

I want to write about some creatures called gubs in my novel The Big Aha. A gub is a small green pig from the Higher World, about the size of a football, with floppy triangular ears, and in place of a curly tail, a writhing bunch of purple tentacles. One of them might appear in your room, go gub-gub-gub-wheenk! Then streak across the room and disappear right before ramming into your wall.

Thinking about the gubs, I remembered that I wrote about small green pigs once before, in the Freeware volume of my Ware Tetralogy, where they were called raths.

[Find paperback, ebook, or CC versions of The Ware Tetralogy]

So today I’m posting a couple of passages from Freeware dealing with the raths. By way of introducing the material, let me give you a little background on Freeware. People have found a way to program lumps of soft intelligent plastic. The stuff can take on all sorts of forms, such as the large, smart descendents of robots who are now known as moldies. My character Corey Rhizome is making small programmed plastic toys that he calls Silly Putters. He’s family friend of a woman named Darla, and her twin daughters Joke and Yoke.

And now let the “reading” begin…

On the girls’ eleventh birthday, Corey showed up with a set of six brand-new Silly Putters. Chuckling and showing his gray teeth, he upended his knapsack to dump the lively plastic creatures out on the floor. “Remember Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky, girls?” he cried. “Jokie, can you recite the first two verses?”

“Okay,” said Joke and declaimed the wonderful, time-polished words.

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.”

Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!

As Joke spoke, each of the six new Silly Putters bowed in turn: the tove, a combination badger and lizard with corkscrew-shaped nose and tail; the borogove, a shabby mop-like bird with long legs and a drooping beak; the rath, a small noisy green pig; the Jabberwock, a buck-toothed dragon with bat wings and long fingers; the Jubjub bird with a wide orange beak like a sideways football and a body that was little more than a purple tuft of feathers; and the Bandersnatch, a nasty monkey with a fifth hand at the tip of his grasping tail.

Joke and Yoke shrieked in excitement as the Jabberwocky creatures moved about. The Jubjub bird swallowed the rath and regurgitated it. The freed rath gave an angry squeal that rose into a sneezing whistle. The Jabberwock flapped its wings hard enough to rise a few inches off the floor. The tove alternately tried to drill its nose and its tail into the floor. The borogove stalked this way and that, peering at the others but not getting too close to them. And the Bandersnatch snaked its tail behind Yoke and felt her ass.

“Don’t!” said Yoke, slapping at the Bandersnatch’s extra hand. The Bandersnatch gibbered, rubbed its crotch, capered lewdly, and then seized the back of Joke’s leg, shudderingly hunching against the young girl’s calf.

“I better do some more work on him,” wheezed Corey, grabbing the Bandersnatch and stuffing the struggling Silly Putter back into his knapsack. “I put so much of myself into each of them that I’m never quite sure how they’ll react to new situations. Quit staring at me like that, girls.”

“Uncle Corey’s a frumious Bandersnatch,” giggled Yoke.

“It was so sick how that thing was pushing on my leg?” said Joke.

“Doing it,” whooped Yoke. “Oh, look, the Jubjub bird is going to swallow the rath again and make it outgrabe!”

“The present tense is outgribe,” corrected the literate Joke. “It’s like give and gave.”

[Now we jump to five or ten years later. At this point, a kind of mind-virus is infecting such soft plastic creatures as the larger "moldies" and the small toy Silly Putters. You need to know that an uvvy is a soft plastic telephone. And Corey Rhizome is worried about a Silly-Putter-like toy dog called Rags that some enemies had sent to attack Darla. And now Darla and her daughters phone Corey.]

Joke told her uvvy to call Corey, and moments later Corey picked up. With their uvvies linked, Darla and her daughters could channel Corey together.

“What?” screamed Corey. “Who the f*ck is it?” Instead of using his uvvy, Corey was yelling at an ancient tabletop vizzy phone with a wall-mounted camera and a broken screen. The brah’s only incoming info was audio. The vizzy’s camera showed Corey slumped at a filthy round kitchen table with the rath and Jubjub bird on top of the table, scrabbling over mounds of tattered palimpsest. The table was further cluttered with ceramic dishes of half-eaten food, a clunky Makita piezomorpher, some scraps of imipolex, and, of course, Corey’s vile jury-rigged smoking equipment.

The Jubjub bird opened its mouth hugely and clapped it down on the rath’s curly tail. The rath outgrabe mightily, combining the sound of a bellow, a sneeze, and a whistle. Corey winced and leaned forward into his smoke filter to take a long pull from his filthy hookah.

“Corey,” spoke up Darla before Joke could say anything. “I’ve been worried about you.”

“Darla?” Corey drew his head out of the fume hood and, shocking to see, there was thick gray smoke trickling out of his nose and mouth. “What happened to Rags, Darla? They took my uvvy away. Things are f*cked-up beyond all recognition. How did you deal with Rags?”

“I killed him with the needler, no thanks to you. At least the two Silly Putters that I can see in your place look normal.” The rath extricated its tail from the Jubjub bird’s beak and reared back to drum its green trotters on the Jubjub’s minute, feathered cranium. The Jubjub bird lost its footing and slid off Corey’s table, taking a stress-tuned lava cup with it to clatter about endlessly in the low gravity. The rath outgrabe triumphantly, and the Jubjub bird let out a deep angry caw.

“It’s funny about those two,” said Corey. “Whenever the others try to infect them, they shake it off . They’re stupid, of course, but certainly no stupider than the Jabberwock or the borogove. I think maybe they’re immune because Willy used a cubic homeostasis algorithm on them instead of the usual quadratic one. It’s been a while. I made them for Joke and Yoke’s eleventh birthday, remember?”

“You and your gunjy Bandersnatch,” uvvied Darla nastily.

“The Bandersnatch is bad news,” said Corey. “I admit it.” On the floor, the Jubjub bird and the rath were vigorously playing a game of full-tilt leapfrog; repeatedly smacking into the walls and then bouncing around all over the kitchen floor, cawing and outgribing and biting at each other.

So that’s it for the reading. Check out the whole Ware Tetralogy if you like. And meanwhile I’m looking forward to having fun with my gubs. Raths redux!

Gub-gub-gub-wheeeeeeeeeeenk!

November 28, 2012

SFictional Higher Realities

I like thinking about a higher or alternate forms of reality. In The Big Aha, I want to give my characters access to a more cosmic or far-out level. And then some of my characters learn to jump bodily into this higher world. And they find some creepy vermin living there. Creatures who do not have humankind’s best interests at heart.

So what is the higher world? Offhand I can think of at least six SFictional possibilities.

(0) This is the traditional one. The “other” world is a physical place in our space. Either on our planet, as in mysterious voyage tales, like an island, an undersea cave, in the Antarctic, in a hidden valley. Or off-world, like on another planet. Or sort of on our planet, but not in an obvious place, like inside the hollow earth, or on a cloud.

(1) It could be a parallel sheet of spacetime, perhaps with a different kind of physics. But I used this option in Postsingular and Hylozoic, and I don’t want to recycle it here.

(2) It could be a higher-dimensional hyperspace. And then our world is a sheet inside this hyperspace, and the hyperbeings move about in the higher dimensions at will. They may dip into our world now and then. I used this model in Spaceland.

(2a) The hyperspace model can be adapted to a religious or spiritualist notions of incorporeal beings looking down on our world. Ghosts, spirits, demons, angels, gods, devils. Spaceland works somewhat along these lines.

(2b) An alternate use of a higher dimensional level is to suppose that the higher beings aren’t particularly aware of or interested in us, they’re simply rooting like moles or writhing around like lampreys, and if they happen to pass through our world it’s more or less an accident. Although then, of course, they might develop a taste for our hyperflat bodies. And then we’re flank steak. Cold cuts. I might like this. I do like the idea of there being stupid, unaware beings in the higher world.

(3) Another idea is to suppose that the “higher” world exists at very small size scales. In what’s sometimes called the subdimensions. I used this approach in Jim and the Flims, where the higher world could be found inside an electron. Lots of room at the bottom!

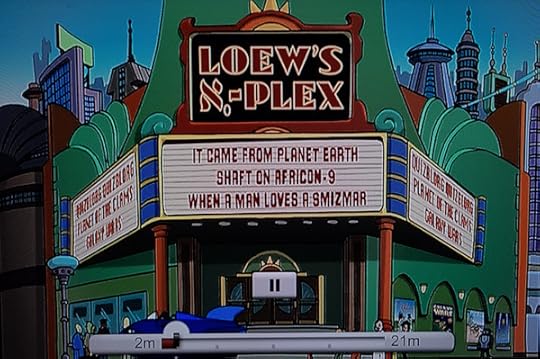

[Lowe's Alef-Null-Plex from FUTURAMA, episode 19 or so, the "Raging Bender" one where Bender becomes a wrestler.]

(4) Or we can go to the “big” direction. That is, put the higher world at an infinite distance from Earth. Out past aleph-null. I used this move in White Light, and at the very end of Hylozoic.

[Our friend Ronna Schulkin with two of her paintings, one painted on the real level, one appropriated on the subtle level.]

(5) Another angle is something more vague—a higher world that overlays ours in the same space, but which is, for whatever reason, generally imperceptible. Perhaps their quantum wave functions are perpetually 180 degrees out of phase with ours. Putting this differently, it may be that the creatures in the higher world are made of a “dark” or subtle type of matter which doesn’t interact with us. And it may be that each of does in fact have a subtle matter soul. You can learn to do a hyperdimensional somersault that twists your elementary particles into bits of subtle matter. That is, you can do a “chin-up” that lifts you into the subtle world. I think this one is the one I like best just now.

A traditional fairy-tale variation on the subtle world is that there’s a secret world right under our noses but we don’t notice it. Elves and fairies that most of us can’t see.

“Night of Telepathy,” oil on canvas, November, 2012, 40” x 30”. Click for a larger version of the image.

One way or another, you end up in the higher world with the archetypes and dreams and thoughts walking around! But! Look out for the subtle rats!

November 23, 2012

Interviewed by Kelly Burnette for Duckter Yezno’s

Today I’m reprinting an email interview that Kelly Burnette of Lakeland, Florida, did with me in October,in order to run it in the first issue of the Duckter Yezno’s webzine—which went public this week, and has a lot of other qrude pieces in it.

Kelly Burnette’s incisive interview centers around my recent novel Turing & Burroughs.

As usual I’ve illustrated this post with “randomly” but perhaps “synchronistically linked” photos from my recent reality gleanings.

The numbers on the questions and answers in the interview relate to my ongoing practice of accumulating all of my email interviews into one giant interview that I keep online as a PDF document called “All the Interviews.”

Here comes the Duckter Yezno’s bus, climb aboard!

Q 368. Your entire family seems to be academically or artistically inclined. You say that you discovered Burroughs, for instance, in a copy of the Evergreen Review that belonged to your older brother. Can you tell us a little about how your family life shaped your interests, what you do today?

A 368. My brother and I grew up in the 1950s in the countryside near Louisville, Kentucky, and our chief form of entertainment was reading books. Our mother encouraged us to read—every Christmas morning there would be a circle of books around the tree, and a fair number of these were science-fiction. A lot of Heinlein. Not that Mom was an SF fan at all, but she’d get advice from the book shop lady. My father had a wood business and then he became an Episcopal priest. He was an independent-minded man, and he encouraged my brother and me to be intellectuals. I met my wife at Swarthmore College; among her attractions were her cultured, intelligent and artistic qualities. Our first conversation involved Pop Art and Andy Warhol. All three of our children are creative types, and all three are self-employed. We have a family tradition of not being cogs in the Big Machine—although admittedly my day job for about thirty years as being a state university professor.

Q 369. I was really happy to hear you weren’t planning on founding a religion to dominate the world! Oh wait! That might well be a much better world. But to jump ahead a little…Mysticism is a tricky concept. On the one hand, it could just be a fancy name for certain kinds of mental experience. On the other, it could be actual transcendence. You’re fascinated with the idea. Can you talk about your take on mysticism within the context of your novel Turing & Burroughs? Do you believe we have a soul?

A 369. I’m agnostic on the soul question. Maybe we have an afterlife, maybe we don’t. Keep in mind that, whatever its literary qualities, Turing & Burroughs is a science-fiction novel, so I don’t necessarily think that everything in it is true. For the purposes of the story it was useful to suppose that dead people could in fact reappear as ghosts animated by immortal souls. My novels White Light and Jim and the Flims touched upon SFictional afterworlds as well. Mysticism is much less intense type of religious belief. It hinges on the notion that you can get a direct perception of the cosmos as a One. An inner light, a big aha, a cozy goo that you can merge into. If you pay close attention to your mental states, this is almost obvious. All is One, the One is ineffable, we can have a direct perception of the One, and Love is all you need. The secrets of the spoken are shouted in the streets. But esoteric philosophy isn’t something you want to be talking about in a novel. A novel is supposed to be fun. It’s better to talk about ghosts.

Q 370. I noticed some very nice, subtle character descriptions in Turing & Burroughs that reflected the individual’s personality well. For example, when you first describe Alan’s love for vacuum tubes, that definitely had a phallic ring to it. It was sexual subtext on par with D.H. Lawrence. How do you think your prose has improved over the years?

A 370. I don’t really see vacuum tubes as penises, but I guess you could. For people of my or Alan Turing’s generations, vacuum tubes were a magical part of daily life. They glow, they get warm, they’re made of glass, they have lots of little doodads inside them, a zillion weird pins on the bottom, and you used to be able to take them to the drugstore and plug them into a testing machine, possibly buying a replacement tube in a little cardboard box. Even now when I look at a city like New York or Tokyo from the air, I’m reminded of the inside of the vacuum tube radio I had by my bed as a boy. Regarding my prose, I’d like to think that it’s still improving—I polish it a little more than I used to. Five or ten years ago, I read John Gardner’s classic how-to book The Art of Fiction, and it had a good effect on me. He talks about paying attention to the spoken rhythms of your text, and about working on the prose at various levels: word, sentence, action, paragraph, chapter, and so on.

Q 371. How much fun was it for you to write in Burroughs’ voice and did you produce it rather naturally (as he’s such an influence), or did you have to work on it, refine it? The letters were a blast to read. Especially the transition from the letter to Jack to the letter to his parents. That was very funny.

A 371. I’ve read Burroughs’s letters many times, particularly the ones in the Yage Letters book, and the ones written while he was in Tangier. While I was writing my pastiches of his letters, I was looking through the actual letters, keeping that voice fresh in my mind. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, I find Burroughs’s bad attitude to be appealing. He’s always been such a breath of fresh air in the face of propriety and social constriction. I once got to hear Burroughs give a seminar talk at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, and I asked him if he laughed while he was writing. “I might,” he said. “If it’s funny.” I laughed quite a bit while writing my Burroughs routines. But it got serious and heavy when it was time to deal with his slain wife.

Q 372. Road trips are significant for two reasons: they’re symbolic of a journey of self-discovery and they’re almost immediately identifiable with the Beats. Alan’s revelations on the road were significant. Did Alan portend that he was becoming a true Christ typology as opposed to superficially saying it one night in Louisiana? Or – can you take us through the course of Alan’s self-discovery while on the road? When did he realize that his greatest gift was sacrifice?

A 372. You could compare Alan to Christ, given that, at the end of Turing & Burroughs, he sacrifices himself for the good of mankind. And early in the book, Alan does in passing think of himself as Christ with his Apostles. But maybe that was a red herring on my part or even a false step. Really I don’t think Turing is coming at his adventures in terms of a Christian framework. The Christians don’t own the redemption myth. It’s a deeper archetype. More like something from Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With A Thousand Faces. Alan has brought a potentially destructive elixir into the world, and he does something about it by transcending to a higher level of existence. He doesn’t really want to die, it’s more that he’s cornered in a certain situation and makes the best of it—by using the SF toolkit that he’s developed as part of his personal growth during the flow of the novel.

Q 373. Is telepathy a correlative for higher consciousness? And is the next step of evolution a conscious one?

A 373. Telepathy is a concept that’s fascinated me for as long as I can remember. I call it teep in my novels. These days I don’t see teep as being at all like a normal conversation. It’s more that you and someone else get onto the same wavelength. Like a talk in bed with a lover, or a deep rap with a pal, or some heavy conceptual play with a mentor. And an outsider is, like, “So what did they tell you?” And maybe you can’t verbalize the details, maybe it’s easier to talk about how having had the conversation makes you feel. Telepathy represents the dream of being understood. Telepathy relates to the notion of merging your personality into the broader world, and this is, once again, an aspect of a higher mystical consciousness. It’s interesting to wonder, as you suggest, if telepathy is an evolutionary step that we’re coming up on. Kind of a Childhood’s End scenario. It’s an interesting SFictional trope, but in reality I don’t actually see humanity as making an abrupt change. I suspect that we’ll have a whole spectrum of personality types, and some will be evolving towards higher consciousness and some will be devolving away from it just as fast. “The squares you will always have with you,” to paraphrase our Lord.

Q 374. Was the Turing & Burroughs character Susan Green based on anyone real? Are you yourself into musique concrète?

A 374. Even though I call myself a transrealist, I don’t always base my characters on actual people. Susan Green was more like a collage of various women I’ve known. I was looking for a strong and idiosyncratic female character to counterbalance all the men in Turing & Burroughs. A woman who’s every bit as outspoken and independent as any man. I recalled that Burroughs was very interested in the idea of taping ambient sounds and collaging them together, and I thought it would interesting to have a woman composer who’s actually doing this. For research, I read the Tara Rodgers compilation of interviews, Pink Noises: Women on Electronic Music and Sound. I’m not in fact a big fan of electronic music, although I do like the idea of it. I made a point of watching the classic SF movie Forbidden Planet, which has a great electronic soundtrack created by Bebe Barron and her husband Louis.

Q 375. Can you tell us a little bit about why you chose to allude to Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore’s novel Fury? Was it simply because Burroughs also used it in The Ticket That Exploded? You remark that it’s a seminal urtext. What’s the significance for you here?

A 375. Okay, this is all about the Happy Cloak. It’s a symbiotic or parasitic alien being, a bit like a coat or a scarf, and it plugs into the nerves in your neck and hangs down your back, and you get into an altered and somewhat ecstatic state of consciousness. Kuttner’s 1947 novel introduces this notion, and Burroughs read the novel during one of his drug-kicking treatments in a Tangier clinic. Later Burroughs incorporated material about the Happy Cloak into in his 1962 novel, The Ticket That Exploded. As a teenager I also read Brian Aldiss’s 1962 fascinating novel, Hothouse, where a morel fungus attaches itself to a character’s neck and begins helping him while controlling him. I always loved that expression “Happy Cloak” because of the contrast between the bland, childish name, and the rather sinister nature of the being. I included a Happy Cloak in my Software, both as an homage to Burroughs and because it was very useful thing to have. A Happy Cloak made of computational plastic attaches itself to my character Sta-Hi’s neck on the Moon, and wraps itself around him to function as a space-suit. Happy Cloaks play a part in the later volumes on the Ware Tetralogy as well. I’m always looking for chances to talk about them.

Q 376. Is there any one book of yours that you’d really love to see made into a film? Cronenberg comes to mind, but who do you picture directing your film?

A 376. Oh, man—any of my books, any director. The Hacker and the Ants would be good as a retro 1980s computer scene movie. The Wares could be epic. Hollywood came close to filming them a couple of times. Master of Space and Time would be a fun movie, for awhile Michel Gondry was all set to do do that. Mathematicians in Love would be very cool, with the surfers and the San Francisco scenes and the flying mollusks. The Hollow Earth could become a huge, big budget production, complete with Edgar Allan Poe, giant sea cucumbers, and an intense racial theme. Turing & Burroughs itself would be a good film, given that there’s some interest in movies about the Beats just now. As for directors, Cronenberg did a great job on Naked Lunch, but I’m guessing it would be a younger person who’d want to take on one of my books. I used to think that sooner or later the mass market would catch up with me. But maybe I’m on a divergent timeline. And that’s okay too. I’m glad I got to write my books.

November 18, 2012

Joey Goes Chimera

Most of my writing energy is going into my novel these days, The Big Aha. It’s only when I’m in a special kind of mode that I manage to blog a lot.

Today’s offering? A short uttake from The Big Aha, involving a tool called a “geener” which sends rays into a living organism to change its wetware in real time.

Also I have some pictures. These days I have an oversupply of pictures.

“How I feel about reading minds!” cried Joey, aiming the geener at himself. “I’ll show you!” The geener hissed, and now Joey had a long rat’s tail. Hiss again, and flydino wings sprouted from his back. Another hiss—and his hips were those of a woman’s.

The security guard was almost upon Joey.

“Oink,” said Joey, whirling around just in time to zap the man.

Artie the guard dropped to all fours—and became a spotted Gloucestershire pig, which was a breed the Trasks had been fond of farming. Pink with black spots. Calmly the pig rubbed his snout across the ground, maybe sniffing for acorns. Meanwhile Skungy, frightened by the chaos, had clambered back onto my shoulder.

Moving slowly, regally, as if fascinated by his own magnificence, Joey unfurled his leathery wings and made as if to flap into the sky—

November 5, 2012

“A Night of Telepathy.” Hidden Aliens.

I’ve been posting about telepathy or teep recently. And in the novel I’m working on, The Big Aha, my characters Morton Plant and Loulou Sabado are now connected by teep.

“Night of Telepathy,” oil on canvas, November, 2012, 40” x 30”. Click for a larger version of the image.

And today I finished a big new painting of the couple, and it’s called Night of Telepathy. I posted a draft of it the other day. Note that the picture now includes six little rats. They’re alien beings called jumbies. I’ll be talking about then below.

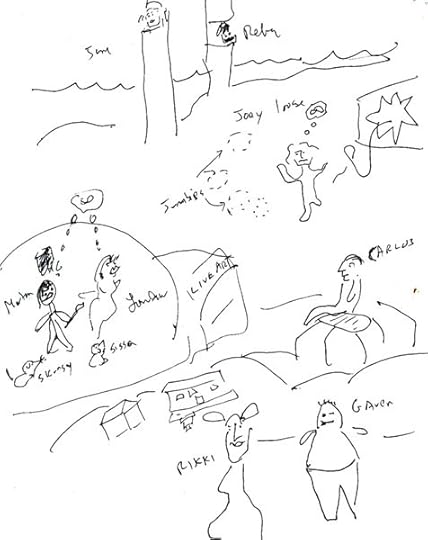

Morton and Loulou met at a picnic in Louisville—the scribbly drawing above was my rough plan for the chapter about them.

I got interested in the awkwardly drawn figures in the lower right corner of my drawing. It’s hard to draw that badly and childishly if you’re paying attention. Expression at a deeper level. Despite the labeled names in my original sketch, I now think of these two as being my characters Morton and Loulou.

Looking for something new, I put theses two into a painting that I jokingly called “The Louisville Artist.” I’ve posted this image before.

So what’s up with those six little rats in my “Night of Telepathy” painting?

“Loulou and Skungy,” oil on canvas, February, 2012, 30” x 30”. Click for a larger version of the image.

Rats play an integral part in The Big Aha. I did a painting involving Loulou and a rat all the way back in February, 2012, when I posted about it. Not that I had any solid ideas at all about my novel then. The paintings really do guide me. And then I ended up writing Chapter One about a quantum wetware rat.

Anyway, the morning after their big Night of Telepathy together, Morton and Loulou are talking about aliens. Morton is narrating.

“I’ve always had a thing for space aliens,” I said, sidestepping a capped youth steering a roadhog limo. The six-legged pig had a depression on his back, with two rows of passenger seats. Funny that the limo had a chauffeur driver. An absurd luxury these days.

Loulou was still thinking about my remark. “If there’s aliens at all, the likeliest place to find them might be in the cosmic mind mode,” she said,

“How do you mean?”

“I always hear rustling and scrabbling when I’m teeping,” said Loulou. “Like there’s things that creep around beneath our reality.”

I’m deeply into the notion of there being odd critters living behind straight-reality’s sets. Like rats on a sound stage. The unseen, ghostly Qwetland darters.

It would be too corny to have the secret aliens be bug-eyed-monsters in UFOs. Better if they’re tachyonic, subdimensional, crooked-beetle, spirit-like beings emerging from an alternate view of reality. “Mighty Mites From Quantum Land.”

Note that I’ve already written about these kinds of aliens as “subbies” in my novels Postsingular, and its sequel Hylozoic, and in “Elves of the Subdimensions” with Paul DiFilippo.

The subbies relate to the quantum wetware thing of The Big Aha. You plug into the cosmic wave function and it’s wiggy. And you can get stuck in this merged state, you’re hearing the “voices of the gods,” you’re lost, talking to all the objects around you.

Scuttlers behind the baseboards of reality, yeah. I like to do a seen-from-the-corners-of-the-eyes routine about these Qwetland darters, or I might call them jumbies—creatures that live out in the analog mindspace. The heretofore invisible aliens whom, for whatever reason, we’re ordinarily unable to perceive. Those flashes of light you see out of the corner of your eye sometimes—those are alien beings.

Putting it differently, the jumbies can be figure/ground kinds of creatures—they were always here, but we weren’t noticing them.

The word jumby, sometime spelled jumbee, is a Caribbean word for ghost. I remember my sister-in-law Noreen telling me about them in Grand Turk in the British West Indies. In the town of Grand Turk, they have zigzag boards on the ridges of houses called “jumby boards.” These are meant to keep those Qwetland darter spirits from alighting on your house like pigeons.

“The Lovers,” by Rudy Rucker, 24 x 20 inches, January, 2012, Oil on canvas. Click for a larger version of the picture.

As long as I’m running so many of my Big-Aha-related paintings in today’s post, I’ll also put in my painting from January, 2012, called “Telepathy” or “The Lovers.” Here’s a link to my old post about it.

November 2, 2012

Magic Mirror Paintings

My character Joey Moon says he’s an artist. He wanted his friend Morton Plant to show his work in an art gallery, but Joey wouldn’t tell Morton the gallery-owner what his work looks like. So at this point, I need to decide what Joey’s work does look like, so I can be prefiguring it, and so I can set it up for a role in the story of The Big Aha.

I’m thinking Joeys work should be nurb-related—where nurbs are the wetware tweaked biocomputational “devices” that we’ll be using in a hundred years. Simple idea: Joey’s works are squidskin displays that mirror the viewer’s face, but with some processing tweaks added.

Call it a magic mirror.

[Here’s a draft of a painting of Joey Moon and Loulou Sabado, characters in “The Big Aha.” The painting is called “Night of Telepathy.” An earlier painting of these two people appears below. Joey doesn’t really look like this, but it’s how he visualizes himself. Actually this might be Joey’s friend Morton Plant, and not Joey himself in the picture. Doing these paintings is helping me a lot with the novel.]

But I need more, something to kick it up a level. Another person’s face can kind of hypnotize you, and you sometimes feel compelled to mimic it. Speaking of fascination, think of the way that you can become enthralled with your own mirror-image, especially if you’re a teenager, or bored, or vain. So the magic mirror’s is showing you your own face slightly tweaked, and you start reacting to the image, and you get into a feedback loop that drives you toward some extreme emotional state.

The extreme state you reach varies according to the viewer’s emotional make-up. The magic mirror simply feels around interactively for the biggest reaction on your part.

Some viewers fully freak out—raging in anger, weeping hysterically, frantically apologizing, roaring in rage, getting lost in grimaces. Their faces get so distorted that they look like Francis Bacon paintings. And the magic mirror might then freeze on a little blither-loop of that peak intensity image.

Later, if you want, you store that clip into memory and reset the magic mirror and collect another image. Or maybe not—maybe Joey freezes all images of himself or of those around him and those are the finished works he sells. If you can do-it-yourself it has more the feeling of a toy than of an artwork, so you ask as high a price.

I saw something a little like this at the San Jose ZeroOne festival in fall, 2012. You’d lie on your back and right over your face you’d see an interactive video image of your face that was tweaked to show your face decaying like a corpse, and with flies, and with fungi growing on it.

Joey doesn’t want to show his magic mirror works to anyone until they go on sale, as the idea could be relatively easy to pirate.

Re. the software in the magic mirror, we can suppose that Joey has some nurb-hacking abilities. It’s fairly non-technical, in that you don’t use a formal computer language. You just need to learn to nurbs in a certain way—perhaps it’s like how the Unipuskers speak in my novel Frek and the Elixir, that is, every sentence is an imperative.

The same two people in a painting called “Louisville Artist,” oil on canvas, October, 2012, 24” x 20”. Click for a larger version of the image.

Rudy Rucker's Blog

- Rudy Rucker's profile

- 583 followers