Rudy Rucker's Blog, page 34

November 13, 2013

THE BIG AHA goes live!

The Big Aha

A Novel by Rudy Rucker

From Transreal Books. Paperback and Ebook. (Hardback coming soon.)

330 pages and 14 illustrations.

***

Biotech has replaced machines.

Qrude artist Zad Plant works with living paint.

Career’s on the skids, wife Jane threw him out.

Enter qwet—it’s quantum wetware!

Qwet makes you high, and gives you telepathy.

A loofy psychedelic revolution begins.

Oh-oh! Mouths in midair, eating people!

Zad and Jane travel through a wormhole—and meet the aliens.

Stranger than you ever imagined.

What is the Big Aha?

***

Browse the entire The Big Aha novel for free as an illustrated web page.

Buy ebook and print editions of The Big Aha.

More info at the website for The Big Aha.

And one more thing: Notes for The Big Aha , a book-length writing journal.

Click for a larger version of The Big Aha cover flat.

November 12, 2013

Ramp up for THE BIG AHA. Locus interview talk about it, May, 2013.

My new novel The Big Aha will be going live quite soon. Available in paperback and ebook via Transreal Books.

By way of building towards the official release, I’m gong to post some background material. Here’s excerpts of an interview taped by Liza Groen Trombi for Locus magazine in May, 2013. The complete interview appeared in the June, 2013, issue, and I recently added it to my “All the Interviews” document online.

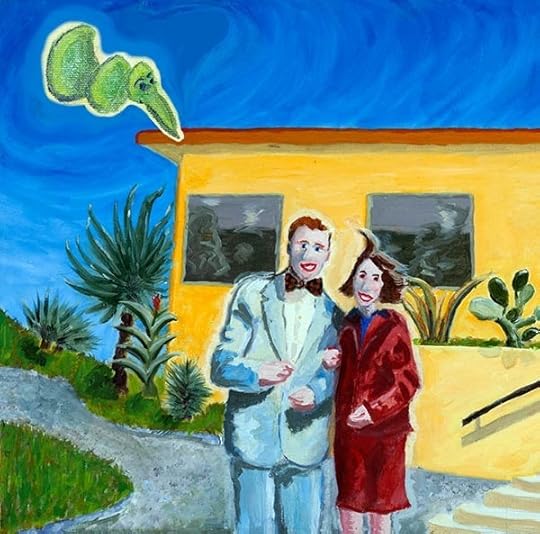

So the rest of this post is me talking May, 2013. I’ll put in some images of my paintings that I used as chapter illustrations for The Big Aha.

The Big Aha is set in Louisville, Kentucky, where I grew up, and I’m enjoying that. If you stay in Louisville, then all the people around you are people you’ve known your whole life, and you can pretty much say anything to them. Nobody cares. I’ve been visiting Louisville lately, and it’s strange.

I enjoy writing books about genomics and the biotech revolution. I think that’s going to be one of the really big technologies of the 21st century. We’re still just barely wading into that. I don’t think it’s unreasonable to suppose that in a century or so, lots of our devices won’t be manufactured machines anymore. They could be plants and animals that have been designed to behave in ways that we consider useful. Even things like a knife or a glass, it’s easy enough to imagine plants growing such things for us. Primitive peoples drink out of coconut shells, but we could tweak it so it’s more what we like. And for communication devices, there’s all this interest in squid skin—that would be a great visual display. Electric eels send out electromagnetic pulses, so that could be the basis of wireless communication.

I wrote a book a few years ago called Frek and the Elixir, set in 3003, where everything was biotech. I wanted to come back to a world like that. In The Big Aha , I wanted to have a book where the technology is based on living things. It’s not set too far into the future, more like 2100.

I was born in 1946, so the Summer of Love was the year I graduated from college. I really liked that period. It was over so quickly. It was getting really good, and suddenly it was over. I wanted to have a story where something like that was happening, but I didn’t want it to be based on drugs. By now everyone has ossified opinions about drugs, they’re for them or they’re against them. It sort of closes the imagination.

I wanted to have something to give people a cosmic experience. I thought, “I’ll use quantum mechanics.” As a science fiction writer, there are various nebulous “bogosity-generator” tools I can use. Something about quantum mechanics that interests me is there are two modes in quantum mechanics. You can think of the world as evolving in a smooth wavelike pattern, but then as soon as you start measuring things, you find a choppy discrete pattern. It’s what they call the quantum collapse, the collapse of the wave function.

In my own mind, I feel like there’s a pulse, where I’ll sort of merge into the place around me and then snap back. Say it’s a nice day, and you’re not really verbalizing to yourself, you’re not really forming opinions in your mind, you’re not doing anything consciously. And then you snap back and you think, “There’s so-and-so, I have to ask them for something; it’s such-and-such o’clock, I have to get in the car and go somewhere.” There are two modes, and I call them the cosmic mode and the robotic mode. It’s almost like sonar—you ping out with the cosmic mode and you pull back with the robotic mode.

The gimmick in The Big Aha is that people get quantum wetware. “Wetware” is already an intriguing word—it’s what’s going on in your body, your DNA, your chemicals. And then make it quantum, so you can consciously control how rapidly you do the oscillations between the cosmic mode and robotic mode. So my characters are party people, they just wedge their minds open to the cosmic, and they’re cosmic all the time. It’s like they’re acidheads, but they’re not taking any drugs. And they can teep each other. And instead of mechanical technology it’s all biological, so instead of a car you have a road spider, and you ride on its back. The animals you create can have quantum wetware as well. You can get in the vibe with them, and make them change their form. And so the world becomes more spacey.

Then, of course, you always need something bad to happen in a novel. It’s always good to have an alien invasion. So there are these things like mouths sticking into our world from another dimension, and they’re eating people. I call it The Big Aha because people always have the dream of getting a Big Aha experience! The big vision beyond the white light. My characters are seeking that. There’s also the Zen idea: “I was looking for enlightenment but it was here all along.” Just for a moment, you feel it—the big aha.

At this point [that is, in May, 2013] I’m not sure who’s going to publish The Big Aha . I’m unsure about my chances with publishers. And I’m starting to wonder if they’re worth the months or even years of waiting, and the begging for such meager pay.

I’m putting a little more sex into The Big Aha than I used to do for my Tor books. David Hartwell once said to me, “If you’re talking about the 13-year-old audience, there are some 13-year-olds who are very interested in sex, and some who aren’t. And you can guess which group is the one that reads science fiction.”

Not that The Big Aha is mainly about sex. But maybe it’s hard for me to judge what’s acceptable. Like I’ve been out there so long that I don’t even know what’s supposed to be normal. In any case I’m having a lot of fun with the book.

I like using the classic tropes of SF—I call them the “power chords.” That’s how I thought of cyberpunk, as a way of taking the classic SF things, like alien invasions, telepathy, giant ants, and making them rock a little harder. That’s what I’m doing in The Big Aha.

I’m confident I can publish The Big Aha with Transreal Books. Maybe I’ll do a Kickstarter. We’ll see how it goes. [End of interview material.]

And it went good! The release is soon!

November 10, 2013

England #3. The “Gherkin.” With Lewis Carroll in Oxford. More V&A.

The last two or three weeks I’ve been laboring on the files for my novel, The Big Aha, and its equally-sized companion, Notes for The Big Aha. Putting them out in ebook, paperback and (what the heck) hardback, also as free browsable webpages. Soon come. I’m sore from the long hours at my computer.

But let’s return to a more restful time…my recent trip to England with my wife.

Happy at the vast outdoor courtyard within the Victoria and Albert Museum. Old, but not as old as I look in some other photos. Good pink light off those striped red and white stone walls. Great museum cafe behind me. English children splashing in the great fountain pool in this enormous courtyard.

A must-catch bot-shot, taken from a bridge in Green Park, near Buckingham Palace. Enchanted towers.

Okay, this was one of my favorite things in London, a very large new building called the Gherkin, set in the financial district, plump and gravid, like a living UFO about to spawn.

I had a nice sandwich at a Pret a Manger near here. Great food chain all over London, I’ve seen them in NYC too. Hunching over my sandwich on its wrapping paper, grunting with pleasure. I come to your world from the Gherkin, yes.

Great contrast of the Gherkin with the old gray stone buildings around it.

On the Tower Bridge, another fab spot. Awesome ye olde metal smithing of the bridge. That’s a new building called the Shard in the background. The new buildings are really taking over, there’s still just a scattering of them, and they still seem interesting and cute. Like when you have two gophers instead of two hundred.

This building is called, I believe, the Walkie Talkie, although I might have called it the Toaster. It’s a lot fatter at the top than at the bottom. Like a cartoon building. Supposedly it’s easier to make odd-shaped structures now that we have computerized blueprints. The reverse of what you might have thought. Computers free us to design odder-looking and less-boring shapes.

In London, maybe because I wasn’t a native, the crazy people seemed cuter than in the US. This man in front of the old Tate museum is doing a Scottish jig while carrying signs relating to the Bible and to global politics. Seems more like an eccentric than a dangerous psycho like back home.

I like these silhouettes in the National Museum. We visited a Peter Bruegel painting there, The Adoration of the Kings. I first saw that painting in London around 1995, it was when I decided to write my As Above, So Below novel about Bruegel’s life.

A note I made in my Journals after that first visit: “The gallery note by the picture says that Bruegel put soldier in his pictures because for most of his life the Netherlands were occupied by Spanish soldiers. This touch makes it seem so real. Makes me want to write Bruegel’s life. The rainy Flemish day.”

Love the curves of the chair and the table. Someone taking the trouble to design and build these things, someone taking the trouble to put them in a cafe. Civilized.

Gotta get your shot of Big Ben. All that detail. It appears over and over in movies, setting a time in the viewers’ minds.

Happy in the National Museum cafe, photo shot with Sylvia’s phone.

So now we’re in Oxford, walking around town. Lots of parts are fenced or walled off, these are the “colleges.” Hard to quite understand how it works, all these separate colleges, each with dorms, dining hall, teachers, and student body. Parts of a university.

I was here in 1976 for a math conference, a Logic Colloquium, I wrote about it in my autobio Nested Scrolls. I talked on “The One/Many Problem in the Foundations of Set Theory.”

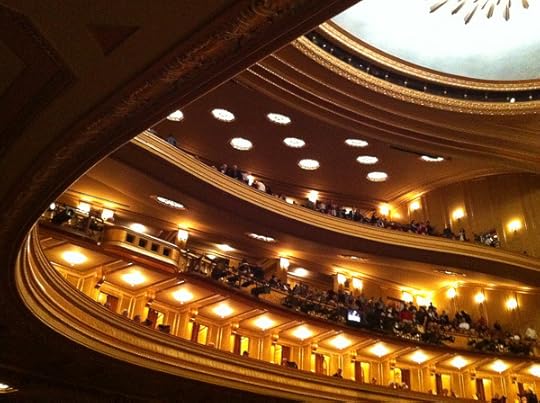

This is the Sheldonian Theatre, used for university ceremonies and for little concerts. We saw an awesome string quartet playing Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons” interleaved with an Argentinean composer’s semi-joking “Four Seasons” pieces written in riposte to Vivaldi, so eight pieces in all, SO frikkin’ civilized.

Looking up at the Sheldonian ceiling during the string quartet, I saw this (just a cell phone snap). The place was designed by Christopher Wren, architect of the famed St. Paul’s cathedral of London. I had some fun looking at the odd polygonal shapes on the ceiling of the Sheldonian, speculating about how Wren put them together, and about how one would go about constructing this pattern in some convincingly unique way. Visualizing a short article in Mathematics Magazine about this, but not quite getting the key insight.

This is Christ Church college where my man Lewis Carroll, a.k.a. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, spent most of his life. He went to the college, then stayed on, teaching mathematics. His Alice came out in 1865, when he was 33. On its grounds, Christ Church has a very large meadow that runs down to the Thames on one side and the Cherwell on the other, both rivers rather narrow here. You can walk slowly around the meadow in an hour and I did this with great joy, thinking about Carroll being here, and imagining his creatures among the cows.

Here’s the meadow…surely Lewis Carroll often enjoyed this view. Symbolic to see the stump, the fallen tree, the missing Lewis Carroll. I sat on it for awhile drawing sketches of Wonderland creatures in the field.

Greedy goose eating an apple core I gave her after I (greedy too) at the apple. This is by the Thames by that Christ Church meadow where Lewis Carroll used to hang.

Birds landing and taking off in the Thames.

Walking around Lewis C.’s meadow I was alert to transformations in the plants an animals. Here’s a tree with a pfumpf-pfumpf face. Dowager Dough tree.

Sitting by the Cherwell for a peaceful half hour there, I’m looking at the leaves on the passing stream, thinking of them like planets in the galaxy, and that one drop of water on the one leaf is a tarn, a sea, home to thousands of microbes, like us lifing on our Earth, drifting amid cosmic debris.

A side-arm of the Cherwell, not flowing, overgrown with duckweed, marvelous name for a plant. Carroll had a friend called Duckworth, he was a master of classics and published, I seem to recall, a book on Vergil’s Aeneid, which I read with my class read in Latin IV in high-school.

Another Carroll creature near the Christ Church meadow. Weirdly animate, this tree, no? Claw, living fork.

Leaving the meadow, I see a bum by the stream, with shopping bags, the ducks edge up to him, he alternately feeds them and shoos them away.

A trim woman jogs past. Bum holds out his thumb as if to hitch a ride, guffaws. She smiles and runs on.

I walk on a bit further, then pause on a tiny hillock by the stream to admire the longhorn cattle in the meadow, behind them are the dreaming spires of Christ Church College and all Oxford.

“Oxford” means a placve wehre they herded cattle across the Thames, which is called the Isis River here as well.

Still more semi-animate plant/animals in the Oxford botanical garden next to Christ Church. This teeth like a Milne heffalump, with great walrus teeth.

And now the bum approached me. Naturally he was Lewis Carroll. Naturally he led me though a series of melting stone walls. to a secret tower room—his ghostly lodgings for, lo, these 200 years.

Naturally he produced a tiny, battered teapot of his own design, and poured out a dram of that magic elixir which has brought me to this “Wonderland” from which I send this very last message to my old workaday world…

And here are the mean, mocking flowers from Through the Looking Glass. Carnivorous plants, by the way.

A few more of them, plotting against Alice.

A pamphlet of paint chips on the lawn. A group of passing tourist youths gawks at me taking this picture. Are they missing something?

In the streets. Just love those dreaming spires of Oxford. So frikkin’ quaint. Would be nice to live here for a couple of years, somehow connected with the university. Going to seminars. Craving something academic, I went into the great bookstore, Blackwell’s, right by the entrance to the campus, and picked up a wonderful book on vector calculus called Div, Grad, Curl And All That. I’d read it before, when teaching a course on this stuff, but now I reread it passionately, getting hyped on a studious frame of mind, reviewing the fact that Maxwell’s equations for electromagnetism are couched in the language of vector calculus with it’s div, grad, curl and all that. Reading it in the coffee shops, in the room.

I couldn’t do some of the problems in the book, and when I got home, I managed to get a solution manual from the publisher. But haven’t gotten back into the frame of mind to read through them. Not on vacation anymore, back here at home.

A British churchyard, in a Cotswold village not far from Oxford. Old as I am, I don’t like graveyards very much anymore. They used to seem quaint and thought-provoking, but now they seem creepy. Bony Death is getting too damned close to my heels.

The wee kirk with kneeler pads crocheted by the ladies of the congregation. British much?

Fab clouds in the Cotswolds, with rain coming on. I would have liked to wander down the lanes and paths here for days, but somehow didn’t manage that. You do what you can on a trip, bouncing around, working with what you’re able to make happen, working with what does happen.

This is one of my favorite snaps from the trip. The clouds echoing off the roof line.

The White Hart hotel in Stow on Wold. Gotta get back here sometime. We were in the area visiting Sylvia’s childhood friend Andrea, who’s a landscape artist. Great to be in her home. She drove us over to check out Stow on Wold. An SF reader thinks of Arthur C. Clarke’s jovial stories, Tales From the White Hart.

Let’s roll back to some more shots from London.

Love this Greek boar-head mug in the Victoria & Albert museum. Thousands of years old. People have been so clever for so long. So many of us making things.

Love this type of sculpture. The lovely woman. The neoclassical rococo schmeer. The elegant handling of the transparent stone drapery across her face…I forget her name, was it Truth? Liberty? The Dream Of Freedom?

Love this kind of sculpture too. It’s glass art, I think, in the V & A, a spiky red egg about a foot long. Mounted vertically, standing on one end, but I turned the picture sideways. More dynamic this way, more like a UFO. A door opens in the tip of each spike and out step 279 ants from Mars. “Can we interest you in some real estate? We’re offering very nice homesteading tracts in Nix Crater, with extremely pliant settlement terms.”

In the art glass gallery some more. Losing myself in the reflections and refractions. You can see on the of ants from mars on my shirt collar, twittering into my ear.

Love the free-sweeping wrought-iron loops. Like shapes you make with an oldtime sparkler or a newtime glo-stick. The work by a guy in Villingen, Germany. I went to a boarding school for a year near there, in a town called Königsfeld, where all the grown-ups called each other Brũder and Schwester. Brother and Sister.

Dig the old master with the Hell’s Angel goatee. The ubiquity of art.

Outside Westminster Abbey. That insanely green English grass. The abbey like a stone fractal, detail upon detail within.

Nice statue of Death here, he’s poking at someone with a spear. The opposite of St. George and the dragon. Can’t make out Death’s profile too well here…he just has his upper teeth and his lower jaw is gone. Dig the ribcage showing through is cloak, and his bony foot. Taking Death really personally and immediately, these oldtime artists.

Doing the postcard thing. I guess that’s the House of Parliament, seen out the side door of Westminster Abbey. Complete with English puddle.

The food market inside the fabled up-market Harrods department store. Seemed like largely foreigners shopping in here…tourists or rich people from the Middle East. Beyond luxury.

Arty mannequins posed by the escalators in Harrods. The walls decorated in an Egyptian theme. I saw a guy buying a $10K Hasselblad camera “for a friend” like he was buying a handkerchief. Not really a camera nut, not asking questions, just like, “I suppose this is a good one. Or should I get the Leica?” The whole place kind of nauseating after awhile.

Art Nouveau door on Harrods. Like the red and white striped stone building in the reflection, lots of buildings like that around London.

Nice blue-painted plywood wall closing off a yard or something. The paint worn in a nice way. I like how natural patterns don’t repeat.

Walking through an alleyway in London Chinatown, not far from Covent Garden. Nice to get off the crowded sidewalks into an alley.

Steam venting in the Chinatown alley. The buildings all solid and brick.

Sunset from our room in South Kensington. That whole chimney-pots thing. Mackerel sky. Golden, changing every second. Like I always say, if it were for some reason difficult to see clouds, what a fetish of them we’d make. But how little I remember to stare at them. The world going all out, every moment of every day. Taking a trip helps me wake up.

Lavender, mauve, purple, violet, I’m never quite sure about that zone of color names. Nice against the classic pillar.

From the design section of the V&A museum, a 1920s fabric with faces as sheets of paper. A witty way to represent writers putting themselves forward.

Photo like this is pretty much a no-brainer. A bot could catch it. Spire with leaves. St. George and the Dragon.

Meanwhile a lone human figure ceaselessly rummages in the mazes of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Lost in Borges’ Library of Babel.

October 23, 2013

England #2. Crowds, Churches, Pubs

In London, we rode around a lot in those classic double-decker red buses. Public transportation. They’re better than tour busses—you get up on the high level and you really see a lot. And you’re with the locals. And if you get on the wrong bus, doesn’t matter, you’re still seeing London. One “wrong” bus led me to one of the biggest bookstores in the world: Foyle’s. My old hacker pal John Walker had recommended it to me. Spent a half hour there, comfortable, reading new science books.

I was surprised how crowded London was—I have this nostalgic tendency to think of London as lonely and foggy like in an old black and white movie, with echoing footsteps on the damp pavements. Many of the sidewalks were filled to capacity people—particularly a shopping area like Oxford Street on a weekend. And the subway trains can be as full as in NYC or Tokyo.

Looking up a site about sizes of city-sprawls or “agglomerations,” I later found Tokyo at #1 with 34 million, New York at #10 with 21 million, London at #24 with 13 million people, and San Francisco (including the whole Bay Area, that is, Oakland and San Jose) at #46 with 7 million.

Lots of white people in London—in NYC or the SF Bay Area you don’t see quite as many. And these English white people, they’re really white…they’re, like, the archetype of whiteness. In the US, we’re programmed by decades of Madison Ave propaganda to think of them as the norm, the Platonic ideal. Many of them are indeed very beautiful or handsome.

I saw a lots of pairs of young women going around together, like hunting teams, with, almost invariably, one blonde and one brunette. The bare legs often quite doughy. Tough-looking short-haired pasty-faced guys as well. Many interracial groups.

Many Indians, Africans, Arabs, and West Indians are in London as well—blow-back from the Imperial days. These two West Indian guys were doing a show in a big square at Covent Garden.

The deal with these outdoor shows is that you yell for a really long time, it’s your chance to shine, and maybe your eventual tricks aren’t all that amazing—these guys were leading up to a limbo routine. But the crowd enjoys the shouting, the rhythm, and the simple feeling of being in a horde.

Peaceful in the churches of course. Sleeping sarcophagus people in Westminster Abbey (or is that the leg-weary Rudy and Sylvia in their hotel room.) Westminster an amazing place, one of those tourist attractions that far outstrips expectations, so full of stuff, with so many levels of detail. Like a fractal.

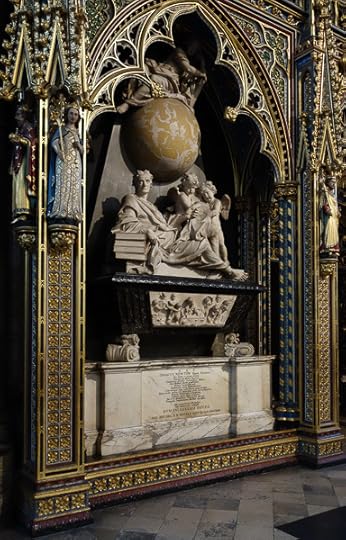

I was ultra-psyched to see Isaac Newton’s grave. Newton! The laws of motion, calculus, the spectrum, gravity—Newton! “He invented calculus?” said Sylvia dubiously. “I don’t think that’s much to be thankful for.” I stood there for awhile, communing with Newton’s big soul. I dug that they had special spot for the graves of scientists, and other spots for artists, and for writers.

Awed and unsure, a woman makes her way past the (replica) sacarphogi in the Victoria and Albert museum. One of those symbols-of-our-daily-life photos.

At one point we managed to attend a church service in Christopher Wren’s St. Paul’s cathedral. I liked sitting there with the lovely, echoing choir music. I was counting things—like the number of panels set into the arches. Odd numbers like 11 and 13. Clever numerical rhythms in the stilled stone.

Studying my guidebook, I’d learned of this seriously old pub on (yes!) Fleet Street called “Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese.” Rebuilt shortly after the Great Fire of London in 1666. Samuel Johnson lived practically next door, and it’s believed (at least by the pub’s aficionados) that Johnson went in there from time to time with Boswell. Like he’d say, “Let’s take a walk on Fleet Street.” Possibly reticent here, as Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese was also, in the old days, a brothel.

The name cracked me up, so we went in there, a windowless place with many nooks and crannies, populated by yuppyish workers from the nearby law courts, dank, echoing, unchanging. Inspired by the Johnson connection, I got Boswell’s “Life of Samuel Johnson” for my Kindle from gutenberg.org, and started reading it every evening. Soothing, mildly amusing.

[Photo above was taken near the way-too-crowded Portobello Road Market on a Saturday in Notting Hill, with two old guys playing John Lee Hooker songs behind the woman checking her phone.]

Another day we stopped by a more congenial pub, the Spread Eagle in Camden Town, with windows, couches and old wooden tables. It was a Sunday, and people were settling in for the afternoon, certainly drinking and laughing, but in a more sociable, slow-paced way than in an American bar. One couple was even playing the Jenga stacking game—the pub had a stack of games behind one of the couches. Like a lodge, kind of. Or a shared living-room. Albeit with a large puddle of questionable liquid on the floor outside the basement bathrooms—a bit manky, that. Even so, I’d happily frequent the Spread Eagle if it were in my neighborhood. You could even sign up to have a convivial Christmas dinner there. And in the evenings—well, I think of James Joyce’s phrase, “shoutmost shoviality.”

The wallpaper in our hotel bedroom had elephants on it. Back in the day, the sun never set on the British Empire, right?

And the nice lady guard at Buckingham Palace holds a machine gun.

October 16, 2013

England #1. Apples, Jetlag, V&A Hoard

I’ve been in England for two weeks with my wife, and along the way I visited my daughter and her family in Madison, Wisconsin, on the way. It was a nice break, and I didn’t do any writing at all. I took quite a few photos. I’m going to put up a series of posts with the images along with whatever relevant or irrelevant comments I happen to think of.

Views from the air are amazing, and almost all of them are good. Even if you’re shooting with a cellphone through a plastic double window. I like the stripes of alternating crops here, I think they call this contour farming.

My grandchildren caught a beautiful frog near the family garden patch. They let him/her go after awhile.

My grandson doesn’t have any guns, but he and I built some futuristic little models with his Legos. Bascially, all you need for a gun is a right angle. One of their neighbors had a yard sale which included some Legos, and the seller had perhaps ignorantly sorted the Legos by color. So I bagged a bucket of the black Legos. What the seller probably didn’t realize is that the black Legos are the quarks, the tau mesons, the Higgs particles of the Lego world—that is, all the weird special-purpose, triple-hinge, worm-gear, fantastically rare gear-axle kinds of Legos are black. Very useful for ray-guns.

We went apple picking and were initially wondering if it was okay of we ate some free extra apples off the trees, but the farmers said go ahead. The trees were way overloaded, with scores or hundreds of fallen apples beneath each tree. A big year for the crop.

I always like getting out in the countryside. Always fun when there’s a window framing a view of a landscape. A living hologram.

So then we made it to London. One of the first places we wanted to visit was the new Tate Modern Museum, housed in a retrofitted power plant by the Thames. They’re especially known for a vast “Turbine Room” that’s used for special giant ultramodern displays but, unfortunately that room was closed for a year-long upgrade of some kind. In any case the funky galleries have a rich hoard of modern art. The image above is from a Russian revolutionary poster and the caption is, naturally, “KAPITAL.” The Ur-Unca-Scrooge.

There’s a nice footbridge across the Thames near the Tate Modern, and we noticed some new buildings in the financial district of a London. They have special names for them—the Gherkin, the Shard, the Cheesegrater, the Walkie-talkie…only the last two are visible here. Much more on the Gherkin in a later post…

So I had jetlag the first couple of nights, snapping awake at 1 am and staying awake till about 4 am. I’ve learned just to go with the flow on jetlag. I get up and read something, or play with my computer. At this point I was reading Thomas Pynchon’s wonderful new novel Bleeding Edge as an ebook—my paper version seemed a bit fat to lug along. I’d go in the bathroom to read so Sylvia could keep sleeping.

On the second day, we hit the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington district of London, not far from our hotel. I’d never been here before, it’s an amazing place. Kind of like the Smithsonian in DC, or like the craft sections of the Met in NYC.

Like, the ceramics gallery has a mashed together collections of pots from all over the world and throughout history, all jammed into case after case of displays, sorted by style or by theme.

In a central area of the ceramics section they had some modern stuff like a dangling cascade of blown glass lamps, trailing down a couple of hundred feet into the lobby area.

Loved this porcelain white hot dog, tied sacrificially to a cutting stand. Wheenk!

Regarded from below and turned on its side, the dangling chandelier becomes a particle-beam tingler-ray.

A really vile-looking bagpipe. What is it about those things? Tools of the devil, morphed genitalia, squealing skugs. Squonk!

That’s it for today. Back in California, I have jetlag again, and I’ve been awake since about 4 am this morning. Time to go lie in the sun in my beloved patch-of-grass back yard. No place like home.

September 24, 2013

“In Her Room.” Revised Art Book: Paper, HTML, and Ebook.

I finished another painting recently.

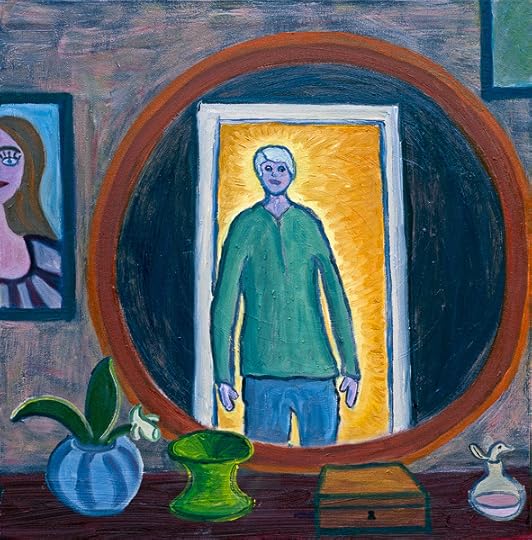

“In Her Room,” oil on canvas, September, 2013, 22” x 22”. Click for a larger version of the painting.

This is a painting of our bedroom, showing my wife’s mirror and some of the things on her dressing-table. That painting on the left is by her, it’s called Kate Croy. I got the idea for the painting when I was coming into our room, and it was dark, and the hall-light behind me was on, haloing my silhouette in light, and I saw myself in the mirror. I like the little objects on the dressing-table, they’re like symbolic icons in a medieval portrait. That green shape is a bridge between two realities.

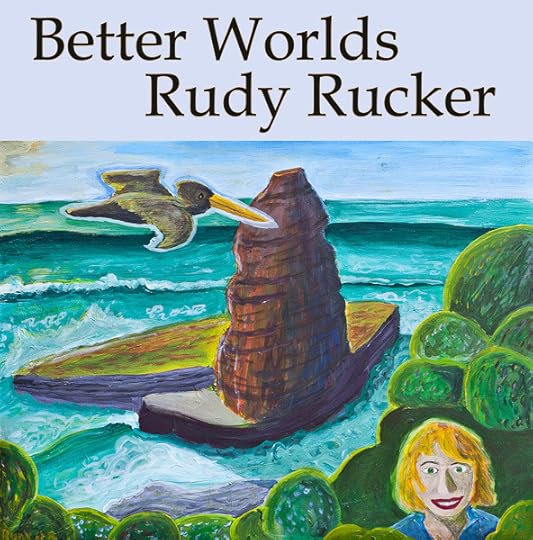

I put together a revised 2013 edition of my art book, Better Worlds. The book includes high-quality images, and a descriptive catalog of my paintings.

You can access the book in a variety of ways. First of all, you can buy it as a quality paperback. This is a high-quality art book that sells for well under the list price of $25.

I’ve also made a free and lightweight PDF file. This small 2K file includes all the catalog commentary, but with only small thumbnails of the paintings.

I made a large free web page. This 12 Meg file includes big images of the paintings as well as commentary. Large file size means it takes a few minutes to load into your browser.

There’s a Kindle Ebook. Commercial ebook edition.

Free Creative Commons ebook editions, in two formats. Large file sizes means the downloads take a few minutes.

MOBI, for use with the Kindle.

EPUB, for use with the iBooks, Chrome and Firefox readers, Nook, etc.

Enjoy.

September 19, 2013

Designing THE BIG AHA. Commas, Fonts, Serifs.

I’ve been working on my books as usual. Rolling right along. Photo of a Santa Cruz roller rink below.

I’m done with the copy-editing and proofreading for The Big Aha , and it’s in good shape. I went through some soul-searching about the serial comma, that is, which do I prefer” “Gray fur, yellow teeth and a naked pink tail.” or “Gray fur, yellow teeth, and a naked pink tail.”

In principle, I’d prefer always to use the serial comma, as then I don’t have to think about it. But maybe sometimes I leave it out without noticing. So I might use it and not use it in the same document. And copy-editors like uniformity. So the copy editor suggested that I take out all the serial commas in The Big Aha.. And at first I went along with that, and then, later today, after putting up my first version of this post, I changed my mind.

[Patio at the legendary Phil’s Fish Market in Moss Landing. We happened to get there at 10 am and it was empty. Had an awesome grilled salmon sandwich.]

Backing up a little, yesterday, after I took them all the serial commas out, some of the more complicated lists became hard to read, so then I put serial commas for some of them. Like “The myoor was shaking, the plants were warbling, and the unborn gubs were cheeping from within the myoor’s flesh.”

It’s considered okay to do that, that is, to generally not use serial commas, but to put them in when it seems really necessary. Not that the readers generally notice either way.

But then, this afternoon, dammit, (and goaded somewhat by my correspondent Mark Dery) I decided I did want my serial commas back, all of them, and I put them back in. Fortunately I had a backup version of my original MS and I could find the serial commas by searching for “, and” — I mean that turns up other commas too, but it does show you all the serial ones.

What writers think about…

This photo was taken during a ride along the edge of the percolation salt ponds in the SF Bay near the San Jose Airport. Up at the north end of 1st Street in Alviso above San Jose. I was riding there with my 79-year-old friend Gunnar, who’s generally fitter than I am. The water drains back and forth between the ponds with the tides and you get cool vortices.

Anyway, this week I’ve been working on the book design for The Big Aha. Picking a font is a process that I’m still getting used to. I didn’t want to use the ubiquitous Times Roman—it’s nice, but I want the book to look not quite so generic. I used Garamond on Turing & Burroughs, and I was pretty happy with that until my cantankerous book dealer friend Gregory Gibson said, “Garamond looks…squatty.” That is, the vertical strokes, like in a t or an m, are shorter than in some other fonts, and the thick parts, like in the diagonal of an s, are a little fatter than normal.

Here in realtime, they’re tearing down a nearby neighbor’s house. It sold, and the new owners want more of a mansion on the big lot. It’s kind of sad and wistful to see an old house being shattered. And how easily they’re destroyed! Mortality.

Back to the fonts. My friend Michael Blumlein recently published his story collection, What the Doctor Ordered, with Centipede Press. The publisher is labeling it Horror, but I’d put it closer to Literary Fantasy. I wrote an intro for the collection. It’s a really nice-looking book, and I thought the font was cool, so I asked the publisher what he’d used, and he said Electra.

Now, Electra isn’t one of the more common fonts that you’d find already living on your computer, so I went and bought it online from Linotype.com, it’s like $30 for the regular letters and $30 for the italics, and more if you want the bold faces, or even the “display” versions that look good when blown up to huge sizes for signs. It’s conceptually interesting to buy a font.

After setting The Big Aha book in Electra, I decided I didn’t like the look of it. A little too spidery, with the letter elements overly thin, so that, at least to my eye, the letters felt a little gray or even broken. Maybe Centipede Press used a different version of Electra, I don’t know…but their book does look great.

Anyway, just to be safe, I went to a classic font that I could find on my computer, Caslon, that is, the Adobe Caslon Pro font. I like this one a lot. For me the idea of a font is that it should feel comfortable and be totally easy to read.

I was at a little BoingBoing-organized conference in San Francisco a few weeks ago. Longtime SF character John Law was there with samples from his Doggie Diner collection. John was an early activist in the Billboard Liberation Front—tweaking public signs in meaningful ways.

Saw an awesome octopus at the Monterey Bay Aquarium this week. His mouth isn’t open, but it’s the pinhole sphincter opening at the center of the star of tentacles, where they all meet, not that you can make that out in this dim-light iPhone shot. Inside the mouth lurks the dreaded cephalopod beak! I think about those beaks all the time. The ultimate vagina dentata. The octopus’s “head” is a big watery sac, used for breathing and for siphon squirts.

The actual “body” isn’t much bigger than a rabbit, it’s a lump on top of the tentacles, and its hidden in the false head sac. For sex, the male passes the female a spermatophore or “nuptial gift,” a packet of sperm, and she opens it days or weeks later, when she’s ready to lay eggs, in a spot that’s safe and with plenty of food. After the eggs hatch, the mother dies.

Love, love, love the tentacles. So serif. Which leads back to…

A little more talk about fonts. I can’t believe that people ever set a book in a sans-serif font. The serifs—those little blobs and curlicues at the corners of the letters—are such a help to the reader. Like handholds on a rock wall. Two more font bugaboos: using a really small font, and using gray letters instead of black or, even worse, white letters on a gray background. I think sometimes people use small fonts to save paper and cut production costs? Are you kidding me? Like giving a TV dinner to someone in a restaurant. Or a miniscule photo of a sandwich.

Dig these sweeping architectural lines at the San Francisco Opera. Love this place. Sylvia and I saw Mefistofele there this week. Not the greatest musical score, but a wonderful production, completely over the top. By no means what you’d call “sans-serif.”

Getting back to my rant about font design—one bad thing that that can happen is, I think, that a book or (more often) a web page might be designed by someone who doesn’t actually read.. They want to be different and cool and hardcore and they don’t actually like text. So—they go with 9 point Arial beige type on a brown background.

When doing a web page, such a person might compound their affront by putting in hard line breaks so the text doesn’t flow into new box-shapes, and they fail to use a screen-size-limited page width, so if you try and enlarge the web page by zooming the view, the text block grows right off the edge of the screen and you have to scroll back and forth like chicken pecking up cracked corn…but you don’t peck for long before you give up on reading the story. And the text-hating designer wins. But, hey, who reads, right?

Recently Sylvia and I found this amazing huge Richard Serra sculpture behind the Cantor Museum at Stanford. It’s like walking around inside a huge typographic letter, say an S or an 8. Before I experienced them in person, I used to think Serra’s sculptures were dull. Like sans-serif fonts. But when you’re inside one of them, it’s a whole experience. Emotional. Fear, awe, joy, mathematical exaltation.

I saw some jellyfish at Monterey too. Sea nettles. Love these guys. Being there reminded me of visiting that aquarium with Bruce Sterling years ago, and we wrote our epic tale, “Big Jelly.” You can read it free online. Readable design…

September 10, 2013

Gnarly SF Reality. #2: Change the World

This post and the previous one are drawn from an essay called “Gnarly SF” which appears in my Collected Essays. You can read the complete essay online as part of the Collected Essays. I split my excerpts into two pieces: “What is Gnarl?” in my previous post, and “Change the World,” which is today’s post. The illos are drawn from my backlog of photos.

Our society is made up of gnarly processes, and gnarly processes are inherently unpredictable.

My studies of cellular automata have made it very clear to me that it’s easy for any kind of social system to generate gnarl. If we take a set of agents acting in parallel, we’ll get unpredictable gnarl by and repeatedly iterating almost any simple rule—such as “Earn an amount equal to the averages of your neighbors’ incomes¬ plus one—but when you reach a certain maximum level, go bankrupt and drop down to a minimum income.”

Rules like this can generate wonderfully seething chaos. People sometimes don’t want to believe that such a simple rule might account for the complexity of a living society. There’s a tendency to think that a model with a more complicated definition will be a better fit for reality. But whatever richness comes out of a model is the result of a gnarly computation—which can occur in the very simplest of systems.

As I keep reiterating, the behavior of our gnarly society can’t be predicted by computations that operate any faster than does real life. There are no tidy, handy-dandy rubrics for predicting or controlling emergent social processes like elections, the stock market, or consumer demand. Like a cellular automaton, society is a parallel computation, that is, a society is made up of individuals leading their own lives.

The good thing about a decentralized gnarly computing system is that it doesn’t get stuck in some bad, minimally satisfactory state. The society’s members are all working their hardest to improve things—a bit like a swarm of ants tugging on a twig. Each ant is driven by its own responses to the surrounding cloud of communication pheromones. For a time, the ants may work at cross-purposes, but, as long as the society isn’t stuck in a repetitive loop imposed from on high, they’ll eventually happen upon success—like a jiggling key that turns a lock.

But how to reconcile the computational beauty of a gnarly, decentralized economy with the fact that many of those who advocate such a system are greedy plutocrats bent on screwing the middle class?

I think the problem is that, in practice, the multiple agents in a free-market economy are not of consummate size. Certain groups of agents clump together into powerful meta-agents. Think of a river of slushy nearly-frozen water. As long as the pieces of ice are of about the same size, the river will move in natural, efficient paths. But suppose that large ice floes form. The awkward motions of the floes disrupt any smooth currents, and, with their long borders, the floes have a propensity to grow larger and larger, reducing the responsiveness of the river still more.

In the same way, wealthy individuals or corporations can take on undue influence in a free market economy, acting as, in effect, unelected local governments. And this is where the watchdog role of a central government can be of use. The central government can act as a stick that reaches in to pound on the floes and break them into less disruptive sizes. This is, in fact, the reason why neocons and billionaires don’t like the idea of a central government. When functioning properly, the government beats their cartels and puppet-parties to pieces.

Science fiction plays a role here. SF is one of the most trenchant present-day forms of satire. Harsh truths about our present-day society can be too inflammatory to express outright. But if they’re dramatized within science-fictional worlds, vast numbers of citizens may be willing to absorb them.

For instance, Robert Heinlein’s 1953 classic, Revolt in 2100, very starkly outlines what it can be like to live in a theocracy, and I’m sure that the book has made it a bit harder for such governments to take hold. John Shirley’s 1988 story, “Wolves of the Plateau” prefigured the eerie virtual violence of online hackerdom. And the true extent of the graft involved in George Bush’s neocon invasion of Iraq comes into unforgettably sharp relief for anyone who reads William Gibson’s 2007 Spook Country.

Backing up a little, it will have occurred to alert readers that a government that functions as a beating stick is nevertheless corruptible. It may well break up only certain kinds of organizations, and turn a blind eye to those with the proper connections. Indeed this state of affairs is essentially inevitable given the vicissitudes of human nature.

Jumping up a level, we find this perennial consolation on the political front: any regime eventually falls. No matter how dark a nation’s political times become, a change will come. A faction may think it rules a nation, but this is always an illusion. The eternally self-renewing gnarl of human behavior is impossible to control, and the times between regimes aren’t normally so so very long.

Sometimes it’s not just single regimes that are the problem, but rather groups of nations that get into destructive and repetitive loops. I’m thinking of, in particular, the sequence of tit-for-tat reprisals that certain factions get into. Some loops of this nature have lasted my entire adult life.

But whether the problem is from a single regime or from a constellation of international relationships, one can remain confident that at some point gnarl will win out. Every pattern will break, every nightmare will end. Here is another place where SF has an influence. It helps people to visualize alternate realities, to understand that things don’t have to stay the same.

One dramatic lesson we draw from SF simulations is that the most wide-ranging and extreme alterations can result from seemingly small changes. In general, society’s coupled computations tend to produce events whose sizes have an unlimited range. This means that, inevitably, very large cataclysms will occasionally occur. Society is always in a gnarly state which the writer Mark Buchanan refers to as “upheavable” in Ubiquity: The Science of History…Or Why The World Is Simpler Than You Think (Crown, 2000 New York), pp. 231-233.

Buchanan draws some conclusions about the flow of history that dovetail nicely with the notion of gnarly computation.

History could in principle be like the growth of a tree and follow a simple progression towards a mature and stable endpoint, as both Hegel and Karl Marx thought. In this case, wars and other tumultuous social events should grow less and less frequent as humanity approaches the stable society at the End of History.

Or history might be like the movement of the Moon around the Earth, and be cyclic, as the historian Arnold Toynbee once suggested. He saw the rise and fall of civilizations as a process destined to repeat itself with regularity. Some economists believe they see regular cycles in economic activity, and a few political scientists suspect that such cycles drive a correspondingly regular rhythm in the outbreak of wars.

Of course, history might instead be completely random, and present no perceptible patterns whatsoever …

But this list is incomplete … The [gnarly] critical state bridges the conceptual gap between the regular and the random. The pattern of change to which it leads through its rise of factions and wild fluctuations is neither truly random nor easily predicted. … It does not seem normal and lawlike for long periods of calm to be suddenly and sporadically shattered by cataclysm, and yet it is. This is, it seems, the ubiquitous character of the world.

In his Foundation series, Isaac Asimov depicts a universe in which the future is to some extent regular and predictable, rather than being gnarly. His mathematician character Hari Seldon has created a technique called “psychohistory” that allows him to foretell the large-scale motions of society. This is fine for an SF series, but in the real world, it seems not to be possible.

One of the more intriguing observations regarding history is that, from time to time a society seems to undergo a sea change, a discontinuity, a revolution—think of the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Industrial Revolution, the Sixties, or the coming of the Web. In these rare cases it appears as if the underlying rules of the system have changed.

Although the day-to-day progress of the system may be in any case unpredictable, there’s a limited range of possible values that the system actually hits. In the interesting cases, these possible values lie on a fractal shape in some higher-dimensional space of possibilities—this shape is what chaos theory calls a strange attractor.

Looking at the surf near a spit at the beach, you’ll notice that certain water patterns recur over and over—perhaps a double-crowned wave on the right, perhaps a bubbling pool of surge beside the rock, perhaps a high-flown spray of spume off the front of the rock. This range of patterns is a strange attractor. When the tide is lower or the wind is different, the waves will run through a different repertoire—they’ll be moving on a different strange attractor.

During any given historical period, a society has a kind of strange attractor. A limited number of factions fight over power, a limited number of social roles are available for the citizens, a limited range of ideas are in the air. And then, suddenly, everything changes, and after the change there’s a new set of options—society has moved to a new strange attractor. Although there’s been no change in the underlying rule for the social computation, some parameter has altered so that the range of currently possible behaviors has changed.

Society’s switches to new chaotic attractors are infrequently occurring zigs and zags generated by one and the same underlying and eternal gnarly social computation. The basic underlying computation involves such immutable facts as the human drives to eat, find shelter, and live long enough to reproduce. From such humble rudiments doth history’s great tapestry emerge—endlessly various, eternally the same.

I mentioned that SF helps us to highlight the specific quirks of our society at a given time. It’s also the case that SF shows us how our world could change to radically different set of strange attractors. One wonders, for instance, if the world wide web would have arisen in its present form if it hadn’t been for the popularity of Tolkein and of cyberpunk science fiction. Very many of the programmers were reading both of these sets of novels.

It seems reasonable to suppose that Tolkein helped steer programmers towards the Web’s odd, niche-rich, fantasy-land architecture. And surely the cyberpunk novels instilled the idea of having an anarchistic Web with essentially no centralized controllers at all. The fact that that the Web turned out to be so free and ubiquitous seems almost too good to be true. I speculate that it’s thanks to Tolkein and to cyberpunk that our culture made its way to the new strange attractor where we presently reside.

In short, SF and fantasy are more than forms of entertainment. They’re tools for changing the world.

September 6, 2013

Gnarly SF Reality. #1: What Is Gnarl?

This post and the next one are drawn from an essay called “Gnarly SF” which appears in my Collected Essays. You can read the complete essay online as part of the Collected Essays, but I decided to extract two blog posts from it. Also note that the essay appears in my small collection Surfing the Gnarl, 2012, brought out by the estimable PM Press of Oakland, California.

I’m going to split my excerpts into two pieces: “What is Gnarl?” in today’s post, and “Change the World,” which will be in my next post.

The illos are drawn from my backlog of photos. As is customary in my blogs, the only thing linking the images to the text is the Surrealist principle of juxtaposition.

I use gnarl in an idiosyncratic and somewhat technical sense; I use it to mean a level of complexity that lies in the zone between predictability and randomness.

The original meaning of “gnarl” was simply “a knot in the wood of a tree.” In California surfer slang, “gnarly” came to describe complicated, rapidly changing surf conditions. And then, by extension, something gnarly came to be anything with surprisingly intricate detail. As a late-arriving and perhaps over-assimilated Californian, I get a kick out of the word.

Do note that “gnarly” can also mean “disgusting.” Soon after I moved to California in 1986, I was at an art festival where a caterer was roasting a huge whole pig on a spit above a gas-fired grill the size of a car. Two teen-age boys walked by and looked silently at the pig. Finally one of them observed, “Gnarly, dude.” In the same vein, my son has been heard to say, “Never ever eat anything gnarly.” And having your body become old and gnarled isn’t necessarily a pleasant thing. But here I only want to talk about gnarl in a good kind of way.

Clouds, fire, and water are gnarly in the sense of being beautifully intricate, with purposeful-looking but not quite comprehensible patterns. And of course all living things are gnarly, in that they inevitably do things that are much more complex than one might have expected. As I mentioned, the shapes of tree branches are the standard example of gnarl. The life cycle of a jellyfish is way gnarly. The wild three-dimensional paths that a humming-bird sweeps out are kind of gnarly too, and, if the truth be told, your ears are gnarly as well.

I’m a writer first and foremost, but for much of my life I had a day-job as a professor, first in mathematics and then in computer science. Although I’m back to being a freelance writer now, I spent twenty years in the dark Satanic mills of Silicon Valley. Originally I thought I was going there as a kind of literary lark——like an overbold William Blake manning a loom in Manchester. But eventually I went native on the story. It changed the way I think. I drank the Kool-Aid.

I derived my notion of gnarl from the work of the computer scientist Stephen Wolfram. I first met him in 1984, interviewing him for a science article I was writing. He made a big impression on me, and introduced me to the dynamic graphical computations known as cellular automata, or CAs for short. The so-called Game of Life is the best-known CA. You start with a few lit-up pixels on a computer screen. Each pixel “looks” at the eight nearest pixels, counts how many are “on” and adjusts its state according to this total, using a fixed rule. All of the pixels do this at once, so the screen behaves like a parallel computation. The patterns of dots grow, reproduce, and/or die, sometimes generating persistent moving patterns known as gliders. I became fascinated by CAs, and it’s thanks in part to Wolfram that I switched from teaching math to teaching computer science.

Wolfram summarized his ideas in his illuminating 2002 tome, A New Kind of Science. To me, having known Wolfram for many years by then, the ideas in the book seemed obviously true. I went on to write my own tome, The Lifebox, the Seashell, and the Soul, partly to popularize Wolfram’s ideas, and partly to expatiate upon my own notions of the meaning of computation. A work of early geek philosophy. Most scientists found the new ideas to be—as Wolfram sarcastically put it—either trivial or wrong. When a set of ideas provokes such resistance, it’s a sign of an impending paradigm shift.

So what does Wolfram say?

He starts by arguing that we can think of any natural process as a computation, that is, you can see anything as a deterministic procedure that works out the consequences of some initial conditions. Instead of viewing the world as made of atoms or of curved space or of natural laws, we can try viewing it as made of computations. Keep in mind that a “computer” doesn’t have to be made of wires and silicon chips in a box. It can be any real-world phenomenon you like. Does this make the world dull? Far from it.

Having studied a very large number of visually interesting computations called cellular automata, Wolfram concluded that there are basically three kinds of computations and three corresponding kinds of natural processes.

Predictable. Processes that are ultimately without surprise. This may be because they eventually die out and become constant, or because they’re repetitive. Think of a checkerboard, or a clock, or a fire that burns down to dead ashes.

Gnarly. Processes that are structured in interesting ways but are nonetheless unpredictable. Here we think of a vine, or a waterfall, or the startling yet computable digits of pi, or the flow of your thoughts.

Random. Processes that are completely messy and unstructured. Think of the molecules eternally bouncing off each other in air, or the cosmic rays from outer space.

The gnarly middle zone is where it’s at. Essentially all of the interesting patterns in physics and biology are gnarly. Gnarly processes hold out the lure of being partially understandable, but they resist falling into dull predictability.

Anything involving fluids can be a rich source of gnarl—even a cup of tea. The most orderly state of a liquid is, of course, for it to be standing still. If one lets water run rather slowly down a channel, the water moves smoothly, with a predictable pattern of ripples.

As more water is put into a channel, the ripples begin to crisscross and waver. Eddies and whirlpools appear—and with turbulent flow we have the birth of gnarl.

Once a massive amount of water is poured down the channel, we get a less interesting random-seeming state in which the water is seething.

Now, the pay-off for this whole ine of thought is that it becomes possible, via some computer-science legerdemain, to argue that all of the interesting processes of nature are inherently unpredictable.

What, by the way, do I mean by “predicting a process”? This means to have some procedure for determining the processes result very much faster than the time it takes to simply let the process run. Saying that a gnarly process is unpredictable, means there are no quick short-cut methods for finding out what the process will do. The only way to really find out what the weather is going to be like tomorrow is to wait twenty-four hours and see. The only way for me to find out what I’m going to put into the final paragraph of a book is to finish writing the book.

It’s worth repeating this point. We will never find any magical tiny theory that allows us to make quick pencil-and-paper calculations about the future. Sometimes scientists—or science-fiction writers—have speculated that there’s some compact master-formula capable of predicting the future with a few strokes of a pencil. And many still have an internal faith in some slightly more sophisticated restatement of this.

But we have no hope of control. On the plus side, the gnarly is a bit better behaved than the fully random. We can’t predict the waves, but we can hope to ride them.

As a reader, I’ve always sought the gnarl, that is, I like to find odd, interesting, unpredictable kinds of books, possibly with outré or transgressive themes. My favorites would include Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs, Robert Sheckley and Phil Dick, Jorge-Luis Borges and Thomas Pynchon.

Once again, a gnarly process is complex and unpredictable without being random. If a story hews to some very familiar pattern, it feels stale. But if absolutely anything can happen, a story becomes as unengaging as someone else’s dream. The gnarly zone lies at the interface between logic and fantasy.

William Burroughs was an ascended master of the gnarl. He believed in having his work take on an autonomous life to the point of becoming a world that the author inhabits. “The writer has been there or he can’t write about it… [Writers] are trying to create a universe in which they have lived or where they would like to live. To write it, they must go there and submit to conditions that they might not have bargained for.” (From “Remembering Jack Kerouac” in The Adding Machine: Selected Essays, Seaver Books 1986.)…

In order to present some ideas about how gnarl applies to literature in general, and to science-fiction in particular, I’m going to make up four tables to summarize ho gnarliness makes its way into science-fiction in four areas: subject matter, plot, scientific speculation, and social commentary.

In drawing up my tables, I found it useful to distinguish between low gnarl and high gnarl. Low gnarl is close to being periodic and predictable, while high gnarl is closer to being fully random.

Keep in mind that I’m not saying any particular row of the table is absolutely better than the others. My purpose here is taxonomic rather than prescriptive. Rather than using the words “predictable” and “random” to refer to the lowest and highest levels of complexity, one might use the less judgmental words “classic” and “surreal.”

Just so you have a general idea of what I’m talking about, here’s how I see some of my favorite authors as located on the complexity spectrum:

Complexity Level

Sample Authors

Classic

Golden Age F&SF. J.R.R. Tolkein, Isaac Asimov, Kage Baker.

Lower Gnarl

Robert Heinlein, William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, Cory Doctorow, Karen Joy Fowler.

Higher Gnarl

Charles Stross, Robert Sheckley, Phillip K. Dick, Eileen Gunn, me.

Surreal

Douglas Adams, John Shirley, Terry Bisson, Anna Tambour.

Let me stress again that I admire the work of all the authors in this table. The point here is simply to point out that one can use various modes and approaches to writing SF. Note that some authors may write novels in various modes—Terry Bisson’s Pirates of the Universe for instance, is high gnarl and transreal, rather than random and surreal.

September 5, 2013

Things I Saw This Summer

I’m emptying out some of my backlog of “to blog” photos. Today’s are mostly from this summer. I have some free time now as I finished assembling the second draft of The Big Aha—as I mentioned in my previous post.

When you revise a painting, you basically keep ruining it and then trying to fix it. When you revise a novel, it’s more of a positive, steady-progress feeling. You just keep making it better. Part of the difference is that painting lacks an Undo function, that is, what Windows users call the Control-Z key.

Photos are something else entirely. Seeing moments and patterns while they’re there. And then—the less obvious and more digital part—tweaking them in Lightroom or Photoshop. The tweak stage has become an integral part of the process for me although, yes, I know there’s some who claim it’s purer to go with the original shot. No point arguing about it. Many roads to Rome, and all that. I just know that I enjoy the tweaking as an exercise of craft, and (thanks to Undo), I’m free to play with the picture until I’ve got what seems to be to be the very best image.

Balloon flower at a kiddie birthday party. Note the stegosaurus piñata as well. As a boy, I only knew of piñatas from Donald Duck comic books. Now in California, they’re rather common. They are strong and leathery, not brittle. The kids whack and whack and eventually the piñata handler lowers the thing near the ground and the kids tear it apart like coyotes on a wounded wild piglet.

Awesome arch off Anacapa Island, part of the Channel Islands near Ventura, CA. We stayed at a nice cheap Vagabond motel in Ventura and rode a ferry out to the islands two days in a row. This summer’s big outing. I went snorkeling here. I was really scared, as the water was so cold and deep and clear, and the place so isolated. So cold I felt like a frozen French fry in boiling oil, not that that makes sense.

Very funky old infrastructure on Anacapa, which is mainly cliffs and a seagull rookeries.

Took this at the cafe at Nepenthe, the insanely crowded yet insanely scenic stop on Rt. 1 near Big Sur.

Back on Anacapa, two seagulls stand guard.

A gnarly tree stump at Moonstone Beach near Cambria. A pretty spot, although the motels here were an insane ripoff in terms of prices. I think a lot of people are there to see the Hearst Castle. Feels like the world population has doubled in the last, what, thirty years?

Awesome aloes near the Mission in Santa Barbara. Kind of cephalopods, no?

Admirable hunks-o-cheese topiary patterns in Cambria.

The elephant seals near Gordo, between Big Sur and Cambria. Supposedly only one male gets to mate with all the females in the herd, and all the other males are continually cringing and challenging, trying to work his way to the top. That one on the left bellowing looks a lot like a U.S. Congressman, no?

Festive flags against a mackerel sky in Santa Barbara. There was a passageway there with some nice cafes, and we went to the same one two days in a row. Not quite as good the second day.

I love Virgin of Guadalupe imagers (this one is in the Santa Barbara mission). The Mandelbrot-set aura. And note the polychrome faux marble on the wall.

A wedding party ramping up for the ceremony at a spot called Ragged Point south of Big Sur. There’s a little-known (to me) series of sights down there.

Odd view through an underpass in Cambria on Moonstone Beach. Like that’s the afterworld or a visionary Peaceable Kingdom on the other side.

The historically giant Moreton Fig tree in Santa Barbara near the passenger train station. The ridges of the roots make veal-pen type separators, forming little sleeping areas for some of the numerous homeless people in S.B.

Rudy Rucker's Blog

- Rudy Rucker's profile

- 583 followers