Rudy Rucker's Blog, page 37

April 5, 2013

Leviathan Feeds On Us Via 4D Einstein-Rosen Bridges!

I had a big SF revelation this week, a breakthrough for my story. Today’s post will include some illustratiave drawings, also some semi-relevant or irrelevant (but nice-looking) photos.

I’m still working on my novel, The Big Aha. I’m about 75% done. Ever since the early chapters, I’ve had these two mysterious glass balls hanging around: the oddball and the dollshead. I wasn’t quite sure what they were going to do for me, but I had a sense that thought ought to be Einstein-Rosen (or “ER”) bridges to a parallel world that I call Fairyland. See my recent post “Four-Dimesional Portals to Other Worlds” for the story on ER bridges.

In the morning I wrote a scene at the start of where something like an elephant is pulled into the dollshead and it disappears. The mental image made me laugh: the fat elephant with trunk outstretched, thick legs star-fished out, thin tail trailing. Passing into and through the little Xmas-tree ball. While the elephant is going through, the ball swells up like a wobbly giant soap bubble, then shrinks back.

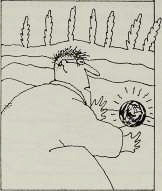

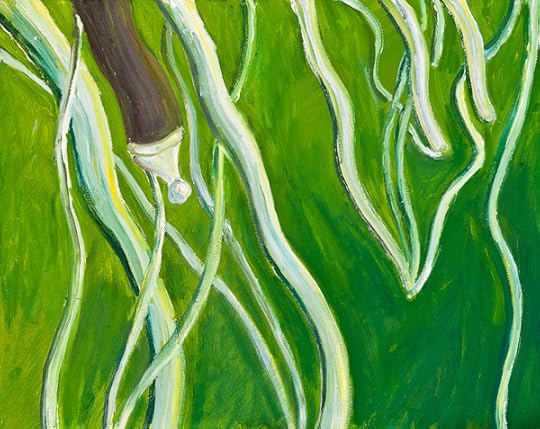

Then I went for a lovely and revivifying hike up over St. Joseph’s Hill above our house, the meadows green, the trees bosky, the sky adrift with plump sharp clouds. Lying there, fully at ease, I was wondering how some creature could contain an ER bridge and yet be an animal or monster with a body and a skin and so on. How would that work? I mean, an ER bridge is a wormhole connecting two spaces. How do you wrap a body around that?

I’ve been coughing for six weeks, and I’ve been thinking I might have pneumonia. I took a little nap on some soft long green grass and when I awoke, I felt like I was finally well. And, as an additional gift, I now had an aha moment. I had a vision of a largish creature, maybe as big as a whale, or maybe even bigger. Call him a leviathan. He lives in the parallel world. And the creature has a number of ER bridges within his body. They’re like vacuoles in the body of a paramecium.

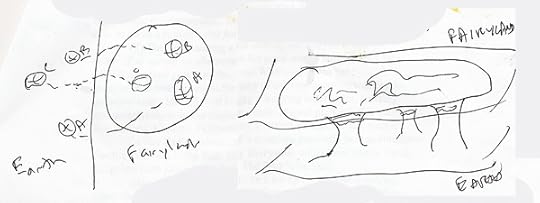

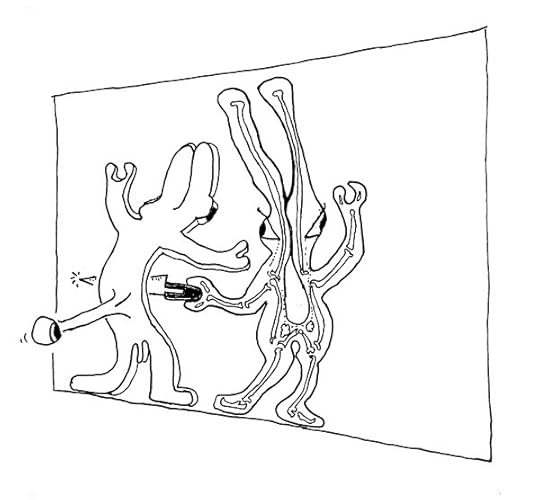

I scrawled the two preliminary images below on a manuscript page I’d brought along on my outing. And the next day I drew something more elaborate. I’ll show those later in this post, but first here’s the crude ones.

In order to discuss the situation further, I’ll use special names for two worlds. I’ve been calling them the Universe and Fairyland, but now I’d like to employ a more neutral usage that I coined in Postsingular and Hylozoic: Lobrane and Hibrane. We live in Lobrane, and Hibrane is the parallel world.

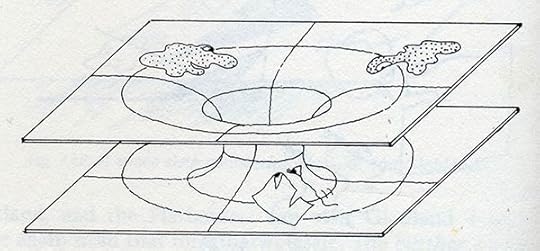

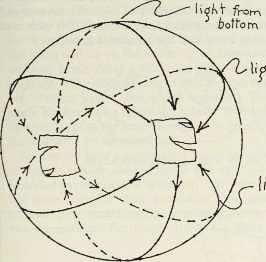

The two ends of an ER bridge between two 3D branes or worlds will appear to us like spheres. So, as I’m saying, the Hibrane ends of a group of ER bridges could very well be spherical vacuoles within the leviathan’s body, and these vacuoles connect to oddball-like spheres down here in our Lobrane.

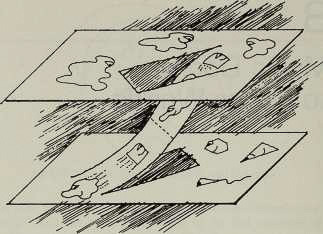

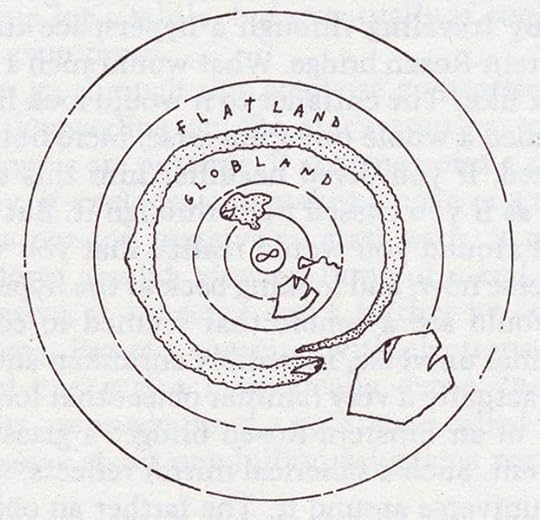

I arrived at this image by thinking of a Flatland model. In the Flatland version we have the two planes with one or more ER wormhole throats connecting them. We draw a big dark glob on the upper plane. The leviathan. And the ER throats are within his body. And—crucial point—his dark flesh extends about 30% or even 90% of the way down each of the throats, holding those throats bulged out. But the flesh doesn’t go all the way down as the leviathan wants to be living primarily in the upper plane.

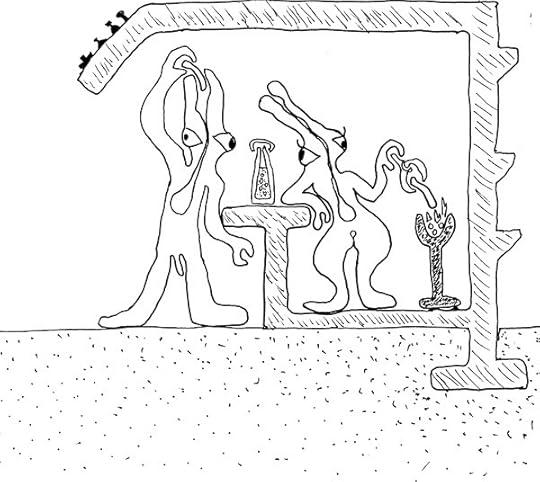

What happens if a Lobrane person sails in through one of the ER mouths? The leviathan is flexible, possibly even jellyfish-like, so the mouth can freely enlarge. Even an elephant can fit through. Fine. But what happens when you encounter the dark flesh of the leviathan drooping down from the Hibrane?

The traditional panic-mongering SF option is that the leviathan dissolves and absorbs you on contact, subsuming you as food. Or he somehow chews you up and swallows you. And this may sometimes happen. Certainly I’d like to see one of my viallains meet his end this way. Possibly the kindly elephant Darby gets eaten in this fashion as well. Maybe a few of Darby’s bones slide back out or are spit out. Grisly effect in the barn there. Maybe just one big, dramatic bone. The ER sphere burps, and out comes a bloody tibia, three feet long and a foot across.

But we’ll suppose that when my hero and heroine go into one of the leviathan’s ER maws, the creature doesn’t invoke its digestive processes. Perhaps our hero and heroine wallow through the jellied leviathan flesh and emerge from its skin in the Hibrane.

The next day I was thinking about the leviathan as soon as I woke up in the morning, and I thought about it all day, off and on, although in the meantime I had to prepare all my tax papers and bring them to the accountant, also go to the dentist. It was good to have the geometry and topology of the leviathan to think about while I was getting my teeth cleaned. It was as if, for once, I wasn’t really there. Dear Mamma Mathematica!

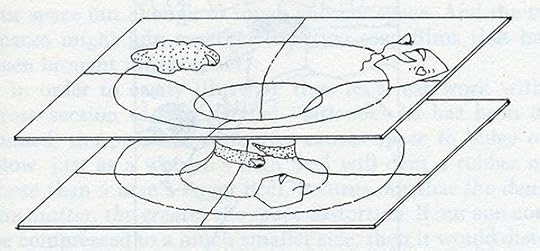

Anyway, the concept I slowly arrived at is that the leviathan flesh that protrudes down into the ER tunnel can have a mouth in it. On the one hand, the mouth can either lead to a toothed-vagina style channel in which you’re ground up, and then moved by peristalsis into one of the leviathan’s stomachs. On the other hand, the mouth may lead through a channel out to the leviathan’s surface, delivering you via a kind of birth canal into the Hibrane world.

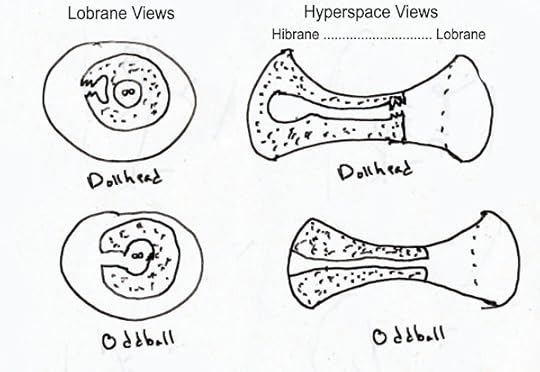

I decided that the likeable oddball should be an ER bridge of the “good” latter kind, a channel to the higher world. And the dollhead ER bridge will be a “bad” one, a route to being devoured.

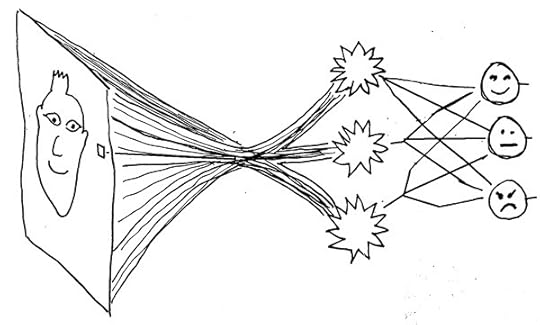

So below I’ve drawn, on the left, the Flatland images of the two ER balls, and on the right the diagrams of the two kinds of ER bridges involved. The tiny lazy-eight infinity signs inside the two images on the left indicate that really that central region contains the whole endless world of the Hibrane. The images on the left are oddly warped perspective images, but they indicate how a Lobraner would actually see the ER bridges.

Now for more details. When my hero and heroine were handling the oddball in their apartment it didn’t feel like it had a mouth or an opening. It felt like a smooth glassy ball—and I’ve draw it that way in the figure above. We can think of the oddball or dollhead as wearing a rind. A clear outer surface over the actual leviathan flesh. Like a cornea. And when they want to get down to business, they split the cornea, and it drops off like a husk. Or with might better think of the transparent cover of the ball as like a nictitating membrane on the eye of a bird or a reptile. When it retracts, it’s covering, say, only the “back” half of the ball.

Alternately the cover gets soft and you can push through it.

The glassy oddball (with shiny rind still intact) will have a golden brownish sphere in the center, with shiny skin. And in this sphere there’s a puckered slit. After the oddball sheds or opens its rind, the mouth is uncovered. It opens up. Looking inside you’re seeing up along a tube that goes through an ER bridge. The tube may open up into Fairland, in which case you’ll “read” that as seeing a lot of tiny objects inside the mouth.

Fabulous! Eureka! Aha!

I’d been waiting for this series of insights and I wasn’t sure they were going to come, but now the Muse has favored me. Thanks in part to logic and math and weeks of butting my head against the wall and, ultimately, taking a nap on a grassy hillock one California spring day.

Okay, now to watch some Futurama on Netflix. 46 episodes done, and nearly as many to go.

March 31, 2013

Garry Winogrand. Shooting Wide-angle Lens.

Today’s post is about the photographer Garry Winogrand and wide-angle lens street photos. If you don’t know anything about Winogrand, here’s good lengthy link-laden post by the photographer Eric Kim. Or, even simpler, you can do what I’ve been doing lately, just do a Google image search.

There’s a big Winogrand show at the SFMOMA just now, which is what got me focused on him again. With (here’s links to more Google Image searches) Lee Friedlander and Diane Arbus, and Robert Frank, Winogrand was one of the last really renowned black-and-white photographers. In the mid-1970s, William Eggleston flipped the game over to color photography.

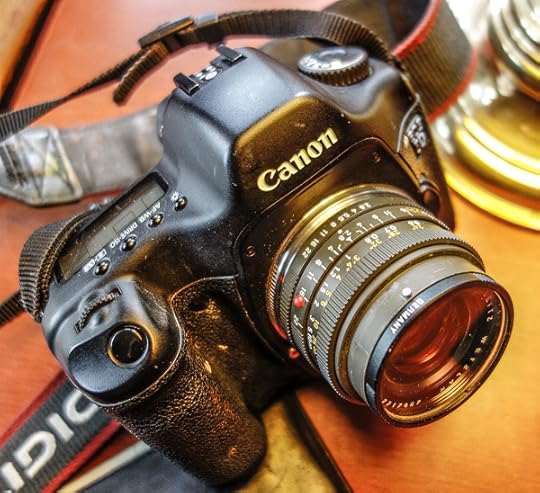

Winogrand used a wide-angle lens (I think 28 mm) on a Leica M4 film camera. As it happens, I used Leicas when I shot film in the 1960s – 1990s, and I have a very nice German-built 28 mm Leica lens that, with a slight bit of effort, I can use on my digital Canon full-frame 5D. So for the last week or two, I’ve been shooting “Winogrand” style, using that lens.

With a wide-angle lens, you can stand really close to someone to get their picture. Winogrand was a fairly pushy guy, I think. So I took an ugly picture of myself clutching my new ten-pound-heavy (?) Winogrand catalog. Recently I’ve been trying to make a brand-new ugly face in the mirror before bedtime every day. I’ve got kind of a Lee Harvey Oswald being shot by Jack Ruby thing happening for me here. With a 28 mm lens it’s pretty easy to shoot in a mirror. Not that I’m going to pursue that in any relentless kind of way.

Your average pocket digicam has a 28 mm lens zoom mode of course. But those cameras don’t really pick up the tonal range that you can get with a heavy duty SLR with some quality glass. I’d toyed with the idea of buying a new Canon 28 mm lens. But those things, they weigh over one pound each. And, like I say, I had this lens right here. My camera body has paint on it because one of the main things I use it for these days is getting shots of my paintings—walking about I’m more likely to have my latest pocket-sized digicam. But now I want to do the lugging routine again for awhile. Like in the old days.

This is our friend Paul and his wife Lydia. They helped organize an Easter picnic that I went to with my son and his family today. Paul’s theatrical, an artist, and he emcees in his pink rabbit suit. So San Francisco.

Most of Winogrand’s pictures are of people—really his primo shooting spots were the crowded cross-walks in Manhattan. So many faces going by. Legally you can shoot a stranger’s picture and sell prints of it and put it in a book, as long as you don’t put defamatory comments about the person. I’ve never had the right personality for getting up close to complete strangers and snapping them.

Another issue about Winogrand—which I won’t delve into at length here—is that he was really into getting photos of passing women whom he considered attractive. And photos of down-and-outers. There can be predatory aspect to street photography, and it can become disturbing. This said, photos of people really are interesting.

Diane Arbus took a different approach than Winogrand did. She’d hang around with her subjects, at least for a few minutes, sometimes for hours, sometimes for days. Really getting to know them. And in her photos you sometimes have the feeling the subjects are looking at Diane and thinking, “This woman is really strange.”

Winogrand was more about the grab shot—although he said he was never surreptitious about it, he’d be looking through his viewfinder. And he’d try to defuse the tension by smiling at the subject.

When you’re comfortable with it, it easy to grab shots of people with the wide-angle lens. The lens has a large depth of field. You only need to set an approximate distance. (The autofocus feature doesn’t work when you marry an old lens to a new camera like I’m doing.)

Another thing about wide-angle lens photography is that the horizon line becomes less important to you. If you’re using a single-lens-reflex, you’re looking through the lens, turning it this way and that, trying to fit more of the world in, composing you scene. Why is the standard horizontal and vertical so sacred? Let it go. Big inspiration from Winogrand.

People would ask him why his photos were tilted and with a straight face (he was stubborn), he’s insist they weren’t tilted. “That’s how the picture is.”

But, like I say, I’m not going out and shooting strangers. I’m happy with something like the sun on these drops of juice.

It’s kind of disappointment to drop back and do a non-tilted shot. Kind of a Joseph Cornell box thing here. That red rubber thing is the mighty flying Troton, an insufficiently recognized and seldom used beach toy.

Landscapes get a looming, creepy look with the wide lens. This is the brain-wave controller device atop Bernal Hill.

It is of course possible to take bad wide-angle lens pictures. You need to have stuff in them. In the last years of his life Winogrand was living in LA, which unlike NYC, is pretty dead on the streets. And he shot, like, a hundred thousand mostly bad pictures of empty streets with like one person half a block away. Reading between the lines, I get the feeling that he was drinking very heavily at this point. His friendlier critics have struggled for some years to find nuggets in the dross of Winogrand’s later work, and there are a handful. But, hey, sometimes when you’re old, you lose it.

Like this guy…

March 30, 2013

Four Dimensional Portals to Other Worlds

Today’s post is about the fourth dimension and about the nature of portals between parallel worlds.

As it happens, in the Bay Area this spring there are not one but two classes being taught on the subject of the fourth dimension of space. And I was invited to give guest lectures at both these classes.

People sometimes dismiss the notion of the fourth dimension by saying, “Oh, that’s just time.” But mathematicians and SF writers are interested in a more bizarre kind of fourth dimension—an actual direction of space or, more properly speaking, a direction in hyperspace.

First, as I mentioned in my post of March 11, 2013, I gave a talk at Alan Weinstein’s mathematics of the fourth dimension class at Berkeley. They were using my very first book as a text, Geometry, Relativity, and the Fourth Dimension, by Rudolf v. B. Rucker. And then I gave a talk at Thomas Banchoff’s freshman level class on the fourth dimension at the University of San Francisco.

I recorded my talk at Banchoff’s class, talking about the fourth dimension of space, Edwin Abbott’s Flatland, and ideas about portals to parallel worlds. The podcast ends with a reading of the second half of my story, “Message Found In A Copy of Flatland,” which you can read online. You can find the recording of the talk at the link below, and I’ll say a bit more about the talk further down.

(Note that Feedburner only shows my most recent podcasts. For older audio files, see my archive on Gigadial, which runs back to 2005.)

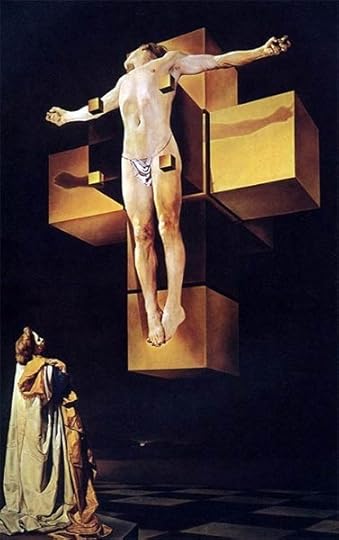

Banchoff has consulted with the artist Salvador Dali about his work, and he famously helped Dali design his painting Christus Hypercubicus, shown below. You can find a video of a full-length lecture by Banchoff on the four-dimensional geometry and theology of Dali online. I believe Tom is giving a version of this talk at USF on June 30, 2013, but I don’t presently have a link for this.

Banchoff invented that paper model of the hypercube shown in Dali’s painting. I was discussing this with him at lunch, and he said, “I have a paper model of a six-dimensional hyperhypercube folded up in my suitcase.” So we went to his office where he had the “suitcase” in which he keeps his lecture supplies.

Tom explained this model to me—bascially you use the three extra dimensions (4, 5, and 6) for bending the model around to glue together each of its opposite sides. If I didn’t grasp this as clearly as he did, that’s because he wrote his Ph.D. thesis on the model.

“I thought if it while I was folding shirts onto cardboards,” Tom told me. “I made the model and took it to my thesis advisor. He said, ‘You’ve found a gold mine.’”

Such a mathematician-style talk. Looking at that cardboard honeycomb and saying it’s a six-dimensional gold mine.

My talk depended on a timeworn analogy. 4:3 as 3:2. That is, in thinking about the mysterious fourth dimension, it helps to imagine a flat two-dimensional creature trying to imagine a third dimension. The flat creatures we usually talk about are Edwin Abbott’s Flatlanders.

The drawings I’m showing here were done by my artist friend David Povilaitis for my book, The Fourth Dimension, which is currently available in used editions only, but which is due to be reprinted in a new edition in 2014 or 2015. I’m sorry about the small size of the images I’m showing here today, but these are old scans, I didn’t want to rescan them.

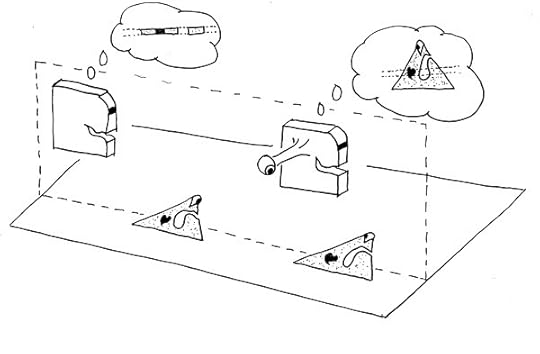

One of the specific things I talked about was the nature of a portal to a parallel world. This is a commonplace in fantasy and SF movies—a magic door to another world. Dropping down to Flatland, we can think of the two worlds as being parallel “sheets” of space. The Flatlanders live on the lower world and some other flat creatures—let’s call them Globbers—live in the upper world.

If we want to make the simplest kind of path between the worlds, we fold up a tab from the lower world and glue it to a tab from the upper world. This is what a door-like portal to another world is like. One problem here is that you need to be very careful not to slide off the edges of the path between the world. Or you might dissolve into Nothingness.

The right way to do it is to use what’s called an Einstein-Rosen bridge. You make a wormhole or throat that runs smoothly from one sheet of space to the other. In seeing this picture, people often worry that the Flatlanders who slide through the throat to the alternate world will end up on the “underside” of that space’s sheet. But you want to think of these sheets as having no thickness so that being on one side of the sheet is the same as being as the other. Or think of the sheets as soap-films with the Flatlanders and Globbers as being like colored patterns in the soap.

Moving up to an Einstein-Rosen bridge between two 3D universes, we can think of our 3D spaces as floating in a 4D hyperspace, and having a “bent” region that connects the spaces. And our 3D spaces have no essential 4D hyperthickness.

In The Fourth Dimension, my character A Square wants to go off to a private place with a Flatland woman called Una. She’s married a jealous Hexagon. In the two images above, we see Square and Una hesitating at the mouth of the ER Bridge. And in the second image, they’ve slid through the portal in the land of the Globbers, and a helpful Globber has wrapped himself around the throat of the ER bridge so that A Hexagon can’t see through.

The image above shows how the situation looks to the 2D Hexagon. He views the mouth of the portal as a circle [in our version we’d see a sphere]. Globland lies within the circle, Flatland lies outside. And the point at infinity lies at the seeming center of the ball—that is, a whole endless world fits into the ball with everything getting smaller and smaller as it approaches the center.

In terms of our space, we can visualize an Einstein-Rosen bridge as resembling a shiny Christmas ornament ball, a sphere within which you seem to see whole world. There are two kickers if the “ball” is the mouth of an ER bridge to another world. (a) The world you see inside the ball isn’t the same as our world. (b) The ball doesn’t have a solid surface, it’s zone that you can walk or crawl through.

I describe an ER bridge in my story “The Last Einstein-Rosen Bridge,” which is also online as part of my Complete Stories. In the story, my character finds the portal lying in an asparagus field near Heidelberg, Germany.

I also describe an Einstein-Rosen bridge in my novel Realware, which is now in print as part of the four-volume The Ware Tetralogy, including Software, Wetware, Freeware, and Realware.

I’ll reprint a scene from Realware where my character Phil goes through an ER bridge, which he calls a “powerball.” In Phil’s case, what’s on the other side of the bridge is a small hyperspherical world, which is why he sees images of himself at the very end.

The powerball came in across the water, low down at Phil’s level, flying straight at him. Phil braced himself, wrapping his arms tight around his knees. The powerball looked like a big, glowing crystal ball, reflecting and refracting light, though not so smooth as a glass ball, perhaps a bit more like a drop of water.

As it drew closer there was an odd effect on the rest of the world: things seemed to melt and warp, distorting themselves away from the magic ball.

Closer and closer it came, yet taking an oddly long time to actually arrive. It was as if the space between Phil and the ball were stretching nearly as fast as the ball could approach. The ball was like a hole opening up in the world. Everything was being pushed aside by it; the sky and waves were being squeezed out along its edges.

Phil looked back over his shoulder; there was still a little zone of normality behind him—the nearest section of the rocky cliff s looked much the same. But so strong was the space warping of the powerball that the beach to the left and right seemed to bend away from him and, as Phil watched, this effect grew more pronounced. In a few moments it was as if Phil stood out on the tip of a little finger of reality, with the glowing powerball’s hyperspace squeezing in on every side. Back there at the other end of the finger, back in the world, Wubwub and Shimmer were peeking out of their cave entrance watching him, the cowards. He fought down an urge to run at them, and forced himself to turn back to face the engulfing ball. What could he see within the ball? Nothing but funhouse mirror reflections of himself: jiggling pink patches of his skin against a blue background filled with moons and stars—his shirt.

And then, like a mighty wave breaking, the warped zone moved over Phil. He felt a deep shock of pain throughout his body, as if something were pulling and stretching at his insides. His lungs, his stomach, his muscles, his brain—every tissue burned with agony.

“Phil! Phil!”

Phil didn’t dare turn; he felt as if the slightest motion might tear his innards in two. But, peering from his pain-wracked eyes, he realized there was no need to turn, for with the powerball centered on him, his view of the world had changed. The entire world was squeezed into a tiny ball that seemed to float a few feet away from him like a spherical mirror the size of a dinner plate. And there in the little toy world, like animated figurines, were Cobb and Yoke. Running toward him. Phil instinctively reached out towards them but—swish—something flashed past his fingers like an invisible scythe. And then—pop—the little bubble that had been the normal world winked out of view, and Phil was alone in the hypersphere of the powerball.

Phil’s guts snapped back to normal; the pain and its afterimage faded. He found himself comfortably floating within an empty, well-lit space that contained glowing air, his body and seemingly nothing else.

[image error]

See you on the other side!

March 22, 2013

Anselm Hollo, 1934 – 2013

[Photo of Anselm Hollo with me in Boulder, Colorado, June, 2004. ]

I just learned that my dear friend and mentor, the poet Anselm Hollo died on January 29, 2013. He’d been ill for nearly a year.

I think of a poem of Anselm’s in which he describes a dream of his dead father. He had the dream three months after his father died. The poem, untitled, appeared in his slim and epic 1972 collection, Sensation, and the poem is reprinted in his tellingly titled autobiographical essay, “Anselm Hollo, 1934-,” which in turn appears in his later collection Caws and Causeries. I’ll quote the last half of the poem here.

…I knew where he lay

went on & entered

the room light & bare

no curtains no books

his head on the pillow

hand moving outward

the gesture “be seated”

i started talking, saw myself from the back

leaned forward, talked to his face

intent, bushy-browed

eyes straining to see

into mine

“a question i wanted to ask you”

would never know what it was

but stood there & was

so happy to see him

that twenty-sixth day of april

three months after his death

“& was / so happy to see him”

Sigh.

I took this photo across from the legendary beat Caffe Trieste in North Beach where my wife and I had coffee with Anselm and Jane Dalrymple some twenty years ago. Anselm not there today.

I first heard of Anselm Hollo in 1972 when my writer friend Gregory Gibson mailed me a copy of that pamphlet-like book or chapbook, Sensation , published by a group calling themselves the Institute of Further Studies, in Gloucester, Massachusetts, traditional home of outrider poets such as Greg himself and of course Charles Olson. Not that Anselm was living in Gloucester. Born and to some extent raised in Finland, he was at this point drifting around the US from one visiting-poet gig to the next.

I read Sensation over and over, fascinated by its colloquial style and by Hollo’s trick of putting more than one twist into each poem—later when I met him he once remarked of some other poet’s work, “Just has one twist at the end, that’s not enough.”

Anselm’s poems are nicely musicked, yet elliptical and hard to pin down. What do they mean? No matter, never mind.

Here’s another poem from Sensation, also untitled. The saying that Anselm attributes to his father has stuck with me for all these years.

it is a well-lit afternoon

and the heart with pleasure fills

flowing through town in warm things

yes what do you know

it’s winter again

but the days are well-lit

what’s more

they’re beginning to stay that way longer

that is a fact

and I am moving

through a town

in a fur hat

the third one in my life

or is it only the second?

the expeditionary force

will have to check up on that

back there in the previous frames

while I move forward

steadily, stealthily

like a feather

I am a father

bearded and warm

and listen to words coming through

the fur hat off a page

in the Finnish language

“when there’s nothing else to do

there’s always work to do”

my father said that

in one of his notebooks

and it’s true

I walk through a town

and up some steps

and through a door

it closes

now you can’t see me anymore

but the lights go on, and you know I’m there

right inside, working out

Naturally you’ll want to read more of Anselm’s poems. At present, the most complete collection of Anselm’s poems is Notes on the Possibilities and Attractions of Existence: Selected Poems 1965-2000 (Coffee House Press, 2001). You can preview the first 60 or so pages of this book via Google Books. But certainly you should buy it, or get it from your library.

I met Anselm in person in the summer of 1984. My family and I lived in Lynchburg, Virginia, at this point. Some of our new Lynchburg friends invented a semi-imaginary society called the Lynchburg Yacht Club. In the summer of 1984 they organized a big party at the boathouse at Sweetbriar College, about fifteen miles north of Lynchburg.

Sylvia and I were excited about the event, and she even sewed me a new Hawaiian shirt, traffic-yellow with fans and cerise designs, billowing and lovely. At the party we danced to a live jazz band, jabbered, drank and flirted. Some of us rowed in the lake, some jumped in naked.

[Anselm and a woman in a two-dimensional world.]

Kind fate brought Anselm Hollo to the Yacht Club party too. He was in Sweetbriar as a writer-in-residence that year. Although he was a dozen years older than me, we immediately recognized each other as kindred spirits. Fellow beatnik writers. And he’d even read my first couple of SF novels.

Anselm had an encyclopedic knowledge of world literature, and an exquisite mastery of the spoken word. He was wonderfully serious about writing. Whenever I was with him, I felt like I was talking to a sage on Mount Olympus, not that there was anything solemn about him. He’d often break into wheezing laughter while we were batting the ideas around. He had a cosmopolitan accent, having grown up Finnish. Anselm once remarked that every Finn deserved to have a biography written. But Anselm’s short, pungent poems are the most accurate memoirs of all, like X-ray snapshots of instantaneous mental states.

We hung out with Anselm quite a bit over the months to come. Anselm and I enjoyed drinking heavily together and talking about art and reality—and ringing strange changes on the words we heard or used. I remember us taking special delight from a line in Rene Daumal’s book, A Night of Serious Drinking: “I have forgotten to mention that the only word which can be said by carp is art.” Inspired by Anselm’s companionship I self-published a book of my poems called Light Fuse and Get Away, saying it was from Carp Press. [This was a 50-copy Xerox edition, later reprinted in my 1991 omnibus, Transreal!.]

Covers of Rudy and Anselm’s paperback double. Click for a larger version of the image.

When we moved to California in 1986, we saw Anselm a few times. I think he was living in Baltimore part of the time, and then in Salt Lake City. I’d written a scroll-type memoir in the style of Jack Kerouac’s On The Road. Ninety feet long. No big publishers would touch it, but I met a poet called Lee Ballentine who ran a small press called Ocean View.

Lee agreed to publish my memoir—it was called All the Visions—back to back with a collection of Anselm’s “science fiction poems” that he called Space Baltic. It came out in a nice “sixty-nine” style format, that is, with the two books bound together upside down relative to each other, so both sides of the book function as a “front cover.” The illo above shows the two covers.

To increase the joy of this event, we got the ultra cool hot-rod underground artist Robert Williams to let us use one of his images as the cover of my half. All the Visions/Space Baltic is out of print, but you can find various editions for sale online, new or used, softcover or hardback. (My own press, Transreal Books, is likely to reprint my half in a new edition this year or the next.)

We saw Anselm for the last time when I was a guest teacher at the Naropa Institute (a.k.a. The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics) in Boulder, Colorado, in June, 2004.

We’d been to Naropa years earlier, around 1980, and that time we’d had a chance to hang around a bit with Burroughs, Ginsberg, and Corso. Of course by 2004, the school was less chaotic. But they were keeping it real with Anselm on the permanent faculty/ Anselm was now settled there with his wonderful wife Jane Dalrymple.

The class I taught was about “Transreal SF Writing,” and while teaching the course, I wrote a transreal SF story called “MS Found in a Minidrive”—funny, gnarly, heavy. I worked in transreal stuff about my nostalgia for the days of Burroughs. The storys narrator, is a would-be-writer who’s attending a Naropa writing workshop. You can find the story online as part of my Complete Stories..

I got to read the story at the end of my Naropa week, back to back with Anselm reading some of his latest poems. We had crowd of about 300 people, it was a wonderful night, the best reading I’ve ever been part of, unforgettable. Rocking it with the Master.

On June 12, 2004, I said my last farewell to dear Anselm. We hugged goodbye and he gave me a sharp, sad, knowing look, perhaps the same look I was giving him, both of us aware that one of us might die before we could meet again. He was seventy, and he’d had a quadruple bypass. But he got over that and went on for eight or nine more years. But now it’s over. As Anselm wrote after the death of Allen Ginsberg:

brave old lion

gone out of reach now

through the one door

awaits us all

One more book of Anselm’s to mention, a book of essays and reminiscences, Caws & Causeries, (La Alameda Press, 1999). Anselm is good at stirring up the old “ontological wonder-sickness,” as the philosopher William James termed it. Why does anything exist at all? Why Anselm, why me?

I’ll close with a poem I found reprinted in Caws & Causeries; it’s originally from Anselm’s 1974 poetry collection, Black Book (Walker’s Pond Press). The poem is a remembrance of Anselm living for a few years with his ninety-year-old grandfather Paul Walden in the south of Germany when Anselm was in his early twenties. Walden was an academic chemist with an interest in the history of science.

THE WALDEN VARIATIONS (for Robert Creeley)

White hair

fine fringes

under the brim

old sunshine on twigs

grandpa

a sturdy

alchemist

old sunshine on twigs

*

old sunshine on twigs

& on the pigs

we ate

together

he & i

deaf alchemist

loud grandson

*

ate together

teeth fell out

& died

old sun

Adios, King.

March 11, 2013

“The Two Gods,” 4D, Networked Matter

I’ve been writing a lot lately, working on my novel The Big Aha, and on a short story called “Apricot Lane.” I also gave a guest lecture at UC Berkeley and participated in a workshop at the Institute for the Future in Palo Alto. In today’s post, I’ll catch up on some of this.

In The Big Aha I have these two mysterious spheres kicking around, about the size of softballs. They’re called the oddball and the dollshead, although their actual names might be Alef and Zeee.

They’re otherworldly beings of some kind, and in the books’ final chapters they’ll transfer one or two of my characters to a higher world for some extra adventures. This is a standard move from the Monomyth or Hero’s Journey pattern, which was famously described in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With A Thousand Faces. (Note that, with a few tweaks, you can get a variation on the pattern that works for a Heroine’s Journey as well.)

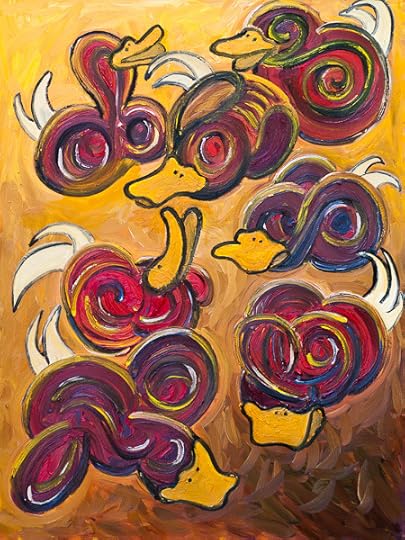

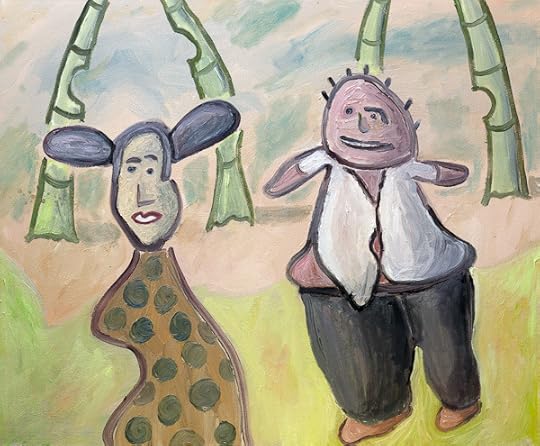

As I sometimes do when I’m stalled or unsure in a novel, I did a painting of these two beings, and I call it The Two Gods.

“The Two Gods,” oil on canvas, March, 2013, 24” x 324”. Click for a larger version of the image.

They’re like lizards, a little bit, with long tails going off into the beyond. I posted a little about my plans for the oddball before on February 5, 2013, in “The Bogosity Generator Tool in Science Fiction,” and when I wrote that post I was thinking about trying to basing my painting “The Two Gods,” on the start sequence seen in Warner Brothers cartoons of the Merrie Melodies or Loony Toons ilk.

On the art front, my show is still hanging at Borderlands Café on Valencia Street in San Francisco. It’ll be up until March 27, 2013, and I have a video of the show below. I marked the prices of my paintings way down for the show, and I’ve sold four in the last month. More info on my Paintings Page.

Rolling back to earlier this month, as I mentioned, I gave a talk on the fourth dimension at Alan Weinstein’s math class at UC Berkeley. The class is using my very first book as their text, Geometry, Relativity and the Fourth Dimension (Dover Publications, 1977). Incredibly this little book is in its seventeenth printing, with over a hundred thousand copies sold.

Above is a scan of one of my older copies. For the class I got into some illos from my novel on the fourth dimension, that is, Spaceland, which was inspired by Edwin Abbott’s 1884 novel Flatland .

Flatland describes higher dimensions in terms of a two dimensional square being, A Square, shown above in my painting of the square and his wife, who is a line segment. In the novel Flatland, A Square is lifted into the third dimension, and gets a view of our world as seen from a higher dimension. There’s a few issues that come up here. If you tug A Square up into 3D space, do his innards spill out? And how can his flat eye with its 1D retina see much of anything in 3D?

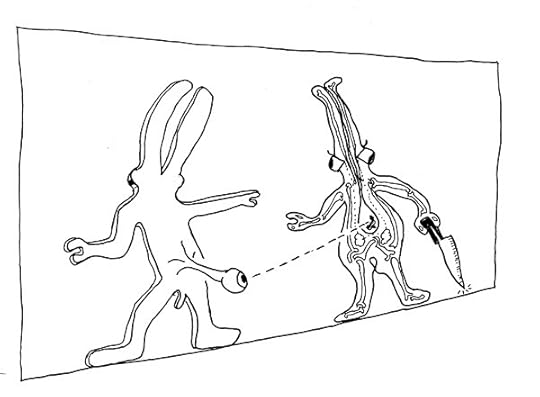

I got into these issues in my novel Spaceland. My solution was that, before a 4D being tugs my hero Joe Cube up into 4D space, Joe is “augmented,” that is, he’s given a bit of a 4D hyperthickness, his upper “side” is sealed off with new skin, and he grows himself a hyperdimensional extra eye that projects out into hyperspace from the center of his brain.

The rather complex image shown above depicts these moves in terms of A Square, up in the higher (3D) space looking down at his father, who is a triangle. If the Square tries to use his normal eye, he only sees a 1D cross section of his father. He needs that higher-D eye to get full 2D images on his retina so he can form mental images of 3D objects.

In the same sense, if you try and use your normal eye to see in 4D space, you’ll only see 2D cross sections of things. And what you want is to have a 4D eye with a 3D retina, so you can look at, like a person, and see all of their inner organs at once. Like the way you see your house in your mind, with every closet and drawer open to your inspection.

A little more fun with the higher-dimensional eye. Suppose that the Flatland creatures aren’t simple squares, but are more like organisms with bones and a stomach. Suppose that “Dad” here has been augmented with some thickness and with a higher dimensional eye. So he can see that flat “Mom” is hiding a knife behind her back.

Mom makes her move, but Dad bulges his belly out into a higher dimension!

I always go check out Telegraph Avenue when I’m in Berzerkistan. Been doing that for forty years. These days the Ave is at a bit of a low ebb. The epic Cody’s bookstore is gone, indeed all four corners of that block are deserted, and, at least on the day I visited, the street denizens seemed to have arranged a pair of trucks so as wall off access to People’s Park. Note the edited street sign.

At least Rasputin’s and Amoeba record stores are still there, not that they’re very flush. All kinds of media stores are fading away…books, CDs, DVDs…all dissolved in the digital torrent.

I’m a bit of a connoisseur of images of the Pig Chef—that traitorous being who delights in slaughtering, cooking and devouring his peers—and I saw this well-executed Pig Chef on a truck by People’s Park. If you’ve never read it, do check out my Pig Chef story, “The Men in the Back Room at the Country Club” in my online Complete Stories. Not to give too much away, in my tale, the Pig Chef is a Sta-Hi-type character who ends up BBQ-ing people and feeding them to alien preying mantises…

Another thing I did recently was to attend Institute For The Future workshop on the theme of objects joining the internet. See the IFTF post on “The Coming Age of Networked Matter.” My host was David Pescovitz, who also does some work at IFTF.

IFTF has commissioned me to write a short SF story on networked matter, the story to appear for free on Boing Boing and in other spots—it’ll be Creative Commons licensed. Madeline Ashby, Cory Doctorow, Warren Ellis will be writing stories as well. For now I’m calling my story “Apricot Lane,” and that’s what I’m working on right now.

I wrote about a rather enjoyable world with tagged and even “living” objects in my novels Postsingular and its sequel Hylozoic. And note that a free CC version of Postsingular exists.

But this time around, for the purposes of “Apricot Lane,” I’m thinking that it wouldn’t necessarily be pleasant if the objects around you could talk to you or exchange information with you.

Thinking along these lines, I remembered the “dogsh*t day” scene in Phil Dick’s novel A Scanner Darkly. Bob Arctor’s car has malfunctioned. He’s pulled over at the side of a freeway with his freaky and possibly evil friend Barris. He’s hallucinating that his engine block is smeared with dog crap, and Barris somehow knows this and is teasing Arctor, smiling at him from behind his mirrorshades. And then Arctor starts to hear the parts of the engine talking to him and he throws up.

He felt, in his head, loud voices singing: terrible, as if the reality around him had gone sour. … The smell of Barris still smiling overpowered Bob Arctor, and he heaved onto the dashboard of his own car. A thousand little voices tinkled up at him, shining at him, and the smell receded finally. A thousand little voices crying out their strangeness; he did not understand them, but at least he could see, and the smell was going away.

Good old Phil.

February 18, 2013

Visit to Manhattan

My wife and I were in Manhattan for seven days this month, basically just there for a vacation. We stayed at pleasant hotel at 41st St. and Madison Ave, just a block away from the NYC Library on 5th Ave, and close to Grand Central Station. Wonderful to see the perpetual steam-smokestack in the intersection with the slushy taxis doing their thing.

The back of the NYC library after a snowstorm.

We made three trips to the Oyster Bar at the Grand Central Station. Truly the freshest clams and oysters in the world. I graduated this time from littleneck clams to the more-to-chew and almost-too-big cherry stones. Also sampled the legendary “ pan roast,” made in special steel pans-on-hinges behind the counter, and consisting of a pint of piping hot cream with toast and oysters and chili sauce in it—a little overwhelming, but you gotta have it once, although next time I’d get the pricier “oyster clam lobster scallop” version.

As a boy I was fascinated by images of the NYC skyscrapers. The Chrysler is still one of the loveliest of them all. You have to wonder why they can’t make such an interesting building anymore.

The Empire State Building has always been my favorite skyscraper. I love how it pops out at you from around corners if you’re within ten or fifteen blocks of 34th St. Sometimes the Empire poses for you in a perfectly framed photo shot.

I guess I ought to say something about the lost Twin Towers. I always thought they were a little dull to look at, wasn’t crazy about them. I never got around to taking the elevator to their top, I wish I’d done that. I still resent Osama and Al Qaeda for having screwed up the opening decades of the twenty-first century. And I’m glad we’ve got the new tower coming up in the footprint of the old ones. But this trip, we didn’t make it that far downtown there again. We were down at Ground Zero in April, 2012, though, and I posted about it then.

This time we only hit mid-town, uptown, Soho, had a lunch at Sylvia’s soul food restaurant in Harlem, and I made a somewhat abortive solo reconnaissance visit to Williamsburg in Brooklyn, where I ended up getting off at the wrong subway stop (twice) and had to walk about ten blocks, guided by the Google Maps beacon of Spoonbill & Sugartown Books, near 5th & Bedford. Bought an intriguing mental-exercises book, D. I. Y. Magic, by Anthony Alvarado, then had a chai across the street, then schlepped to the Marcy St. subway stop and rode back to *ah* the tall buildings of old Manhattoes. Nothing beats being an ant in the cracks of those canyons.

One of the very first things we did in New York was to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Here’s the great entrance hall. A secular cathedral.

A random fop in the galleries of the Met. What often happens here is that we have an intention to see, let us say, galleries A, B, and C. But on the way from A to B, we always pass some heretofore unnoticed gallery that’s filled with amazing, unexpected things. The Met is a fractal.

A design gallery showing a ray-gun-like device that was, if I remember correctly, used to spritz bubbles into water.

I rode the bus down Fifth Ave to meet my old Tor editor David Hartwell in the Flatiron building, another great NYC icon. And grabbed this dirty-window shot. My Pop showed it the Flatiron to me when the two of us visited NYC in 1959. I always feel proud when I have a little business to do here.

My favorite views of the skyscrapers are from Madison Square park at 23rd and Madison, not to be confused with Madison Square Garden. One thing I’ve slowly learned over the years is that sometimes a photograph is better if you use a tilted horizon. The iconography of this building is interesting: the giant CLOCK. They inhabitants might have been selling insurance…

I visited the new MOMATH or Museum of Mathematics which is on Madison Square. I wasn’t super impressed with the space—it was small, and too many of the exhibits were simply computer programs on screens. Changing the physical computer controls to “look fun” doesn’t change the fact that you’re looking at a program you could be running at home. But MOMATH does have a few physical displays that are good, especially this tricycle with square (!) wheels. I was allowed to mount it, and it rides very smoothly—because it’s going on a surface made up of inverted catenary curves.

One other nice thing in MOMATH was this Truchet tile pattern on the wall of the bathroom. Can you see what it says?

A big snowstorm hit Manhattan while we where there—the storm was stronger in New England, but even in NYC we got three or four inches. As California tourists with no particular agenda, the snow was simply fun for us. Wonderful to see it tumbling down in the night, we went up onto the roof of the hotel with our friend Eddie Marritz and his wife Hana Machotka.

The morning after the storm, Bryant Park by the NYC Library was full of views. The trees snow-edges among the towers.

A a traditional snow photo, nice to encounter it in real life.

I might have been waiting for a bus here, taking shelter in the entrance way of yet another wonderful old-time skyscraper, it’s portal clad with bronze.

This was near the bus stop on Madison Ave where we’d embark uptown. Although I love subways, you get to see more from busses. The red balloons advertised a luncheonette.

One snow-day we walked up through Central Park past the back of the Met arriving at the Neue Galerie and its Viennese cafe. I like how some of the buildings seen from the park seem like castles.

Walking through the snowy park, the colors of a tunnel’s tiles popped out. Fleshy, in a way, a dragon’s maw.

We came upon an old friend, the Egyptian obelisk known as “Cleopatra’s Needle,” and mounted in Central Park behind the Met. I like the contrast between the rigid obelisk and the snaky tree. Yang and yin.

I’ve always loved the iron crabs supporting Cleopatra’s Needle. The crabs have human faces, though you can’t see that here, and some have Greek letters on their claws.

We met up with Eddie Marritz at the Neue Galerie. What a great cafe they have. The art’s good too, although in the shadow of the Met, every gallery pales. But good to see some German Expressionists. Looking at all the paintings—naturally we hit the (non-math) MOMA too—I thought of a dozen “new” ways I could try to paint.

New F*ckin’ York. I’ll be back. One of the things I love most there is simply the urban architecture, block after block of insanely large buildings, and so many of them are from the 30s and 40s, and encrusted with lovely detail work. The glass box era was a wasteland, but finally they’re turning the corner and putting some interesting facets, beveled corners, polyhedral slants and spike-towers onto the boxes.

The other thing I love most in NYC is the people. The anthill! Being in it, scuttling and bustling, peacefully anonymous, with a freedom to glance at and browse the moving encyclopedia of humanity.

February 5, 2013

The “Bogosity Generator” Tool In Science Fiction

As most of you probably know, filmmakers use the term “MacGuffin” to stand for some object that various characters in the tale are competing for. A secret paper, a formula, a stunning gem, a statue of a Maltese falcon…

In Fantasy and SF novels we have a slightly different convention—a special device or procedure or organism with special powers that affect the flow of the story. The writer very often works backwards, that is, they get some visually or conceptually interesting thing happening in their story, and only then posits a gimmick that will make the effects possible.

There must be some standard generic name for these gimmicks, and if so, I’ve probably heard it, but for whatever reason, I can’t think of a completely apt and standard phrase today. Deus ex machina isn’t quite right, as that’s more specifically a miraculous something that saves your characters. Pixie dust is fairly accurate, but it doesn’t have the technological feel that I’d like. I’ve seen handwavium too, and that’s not bad, but I guess I’d like a new phrase for this.

Let’s call what I’m talking about a bogosity generator. Kind of like a tank of helium, useful for inflating your pretty balloon animals so they can bobble across the ceiling. Or, more obviously, like an electrical generator that sets the great streams of sparks to arcing across your mad-scientist lab.

The rules are that fantasy authors aren’t expected to justify or to explain their bogosity generators, but an SF writer is expected to cobble together some kind of semi-plausible, paralogical, science-like explanation—that’s considered part of the fun of SF. The styles of these hand-waving explanations change with the intellectual fashions of the times. Over the years, preferred bogosity-generator-justifiers have included radio waves, radioactivity, the subdimensions, relativity, psi powers, black holes, quantum mechanics, parallel worlds, nanotechnology, chaos theory, superintelligent AI, an escalating technological singularity, bioengineering, and our dear friend the Higgs particle.

One point that’s worth making over and over is that an SF writer’s explanations for his or her bogosity generators serve a creative purpose. The theory behind your bogosity generator is not idle bullsh*t. Why? Because in the process of making up the explanation, you get ideas for new things to do with the bogosity generator.

When you’re thinking about the explanation, it’s like you’re reading an instruction manual for some cool new device. Admittedly, you yourself are writing the instruction manual at the same time that you’re reading it, but the manual is not a complete fabrication—it’s constrained by having to be logical, concise, intellectually appealing, internally consistent and, to a certain degree, externally consistent with some cherry-picked facts of science.

When you get a really fine explanation for your bogosity generator, it’s no longer the case that your story tells a lie . If the explanation is really cooking, the lie tells your story. Yeah, baby. That’s where you want to be. It’s a variation on a carnie grifter saying: “Don’t run the con. Let the con run you.”

It sometimes happens that an author invents the bogosity generator before deciding what it’s supposed to do. You might dream one up early in a novel simply because you know you’ll be needing some explanatory device sooner or later, even if you haven’t quite yet decided what kind of weirdness you’ll be needing to explain. Or you’ll have a nice mental image for a funky bogosity generator, and you go ahead and describe it without even knowing what it does or how it “works.”

This is the situation that I’m in with my novel-in-progress The Big Aha . About a quarter of the way into the novel, I introduced a bogosity generator called an oddball. It has some of the qualities of a MacGuffin, in that some of characters immediately set to work stealing the oddball from each other like the spies vying for that Maltese falcon. But it’s also meant to be a bogosity generator. I’m expecting great things from my oddball. Only I still have to figure out what those things will be—and what’s the “explanation” for the oddball. And I’m glad I still have to figure these things out, as I need material for the second half of the novel!

Here’s some text from the draft scene, where the oddball is introduced. I might mention that by a “nurb,” I mean a biotweaked plant or animal. In the future era where The Big Aha is set, somewhere near the end of the 21st century, tailored organisms have almost entirely replaced machines. “Teep” is telepathy. “Qwet” means “quantum wetware,” which is a bogosity generator of its own, it provides people with teep and with an ability to get their heads into a high “cosmic” state.

A scratched, glassy object sat upon a carved wooden shelf. It was a sphere the size of a robin’s egg, transparent on the outside, with an opaque core. This central core was dark purple. I’d often studied the object, trying to decipher its origins and its purpose, wondering over the sparks of reflected light that danced within. The deeply maroon central core was a spiky compound assemblage, a stilled explosion that resembled a sea urchin.

The really odd thing about this particular curio was that its appearance continually changed. The calligraphic scratches on its surface tended to wriggle and drift; the central core wobbled and varied in size. Once in a great while, if I’d fiddled with the curio enough, I’d see a stumpy cylinder grow out of the central core and out through the curio’s transparent side. This cylinder was like a smooth, leathery tube, but its outer end gave the appearance of having been roughly severed.

My wife Jane called this little sphere her amazing oddball. She’d picked it up in Manhattan, on the East Village beach that bordered the now-submerged Alphabet City district. Jane liked to claim that the oddball had called her by whispering her name. We’d never quite decided what it actually was. At first we’d taken it for a plastic amulet with an embedded holographic display—but then we’d decided it was biological, probably a nurb. Not that it resembled any nurb that had ever gone into production. Nor did it have any obvious commercial purpose. An abandoned experiment? A wild nurb that had emerged on its own?

I centered myself and took the oddball in my hand. It nestled against my palm, and I seemed to feel a faint glow of teep from it. Not something I’d ever noticed before. Was the curio somehow synching with my qwet mind?

Two months ago, I formed the desperate plan of having my oddball be someone’s severed third eye, to be used in concert with hopping from our world up to a parallel world called fairyland. I described this far-fetched idea in my December 10, 2012 blog post, “Cosmic Fairyland 2: Third Eye”.

That was a useful idea in that it helped me to continue writing. But the whole fairyland and third eye thing is too baroque to maintain. It introduced too many extra story elements into my novel. So I’m downgrading the oddball’s abilities. My character Loulou didn’t actually use the oddball to travel through another dimension to a parallel world and then hurl small green pigs, known as “gubs,” into our world for the other characters to see. (Gubs are described in my post of November, 30, 2012, “Gubs and Raths”.)

Instead, I’m now only requiring that the oddball has the effect of allowing Loulou to (a) make herself invisible without in fact leaving our world, (b) to project images and seemingly solid objects into reality, somewhat in the style of what spiritualists call a “physical medium.”

Fairyland was only Loulou’s hallucination, but the oddball allowed Loulou to become invisible, those around her thought she might be off in fairyland, and her ability to reify her imagined gubs made it seem like she might be off in fairyland tossing gubs into our world.

So now I’m trying to get more specific about what the oddball does, and how it works. I’m thinking I’ll say that contact with the oddball allows telepaths to begin converting normal matter into something I call wacky matter. Of course, wacky matter is merely a subsidiary bogosity generator. But it’s getting closer to something useable. I was already thinking about wacky matter a year ago, see my Jan 16, 2012, blog post, “Future Ads. Fun with Wacky Matter.”

So, repeating what I just said, I’ll assume that people who have access to the oddball can turn objects into wacky matter that they control. And later on, people who merely have an understanding of the powers involved in the oddball can create and control wacky matter too.

Let’s back up and describe wacky matter again. Wacky matter is like psychic Silly Putty. It takes on shapes and patterns to match any outré mind state. Peoples’ houses might change into big shoes or have rooms with ceilings one inch tall, or maybe look like Dogpatch scenes from Al Capp’s Li’l Abner. You might dose your surroundings to make them more vibrant, more cartoony, more congenial. Instead of you getting high, your house gets high! Don’t run your con, let your con run you.

Why do I want wacky matter? The Big Aha is about a future psychedelic revolution that arrives in scientific form. It will be kind of perfect if my qwet, qrude, loofy characters can taint the physical world with wacky matter—thanks to their quantum wetware and their oddball energy. Did Kesey and Leary change the world around them? For awhile. And then the world pushed back. We got hit with Charlie Manson and with disco. Wacky matter became a destructive and repressive force.

Over the past year, I’d forgotten all about wacky matter. But recently I stumbled across the contemporary real-tech notion of “metamaterials”—which reminded me of my fictional concept. Metamaterials are engineered to contain regular lattices of atoms that subject light rays and other electromagnetic fields to transformation optics—a bit like a lens does. Supposedly a metamaterial can become invisible via a so-called electromagnetic cloak or “metamaterial cloaking.” As the Wikipedia article puts it, “The guiding vision for the metamaterial cloak is a device that directs the flow of light smoothly around an object, like water flowing past a rock in a stream, without reflection, rendering the object invisible.”

I don’t want to use the word “metamaterials” more than once in The Big Aha, and then simply as a background justification for wacky matter. The thing is, I can barely understand the Wikipedia explanations of metamaterials, and the factuality of the concept limits me, and I don’t want to be playing catch-up-ball. Better to take a little inspiration from the science, but then be working with a completely bogus concept that I’ve invented, and which will obligingly have any properties that I require. Writing my own instruction book for my bogosity generator. Wacky matter, not metamaterials.

I can straight-up use the metamaterial cloaking routine for oddball/wacky-matter invisibility. And projecting images and objects into wacky matter can be explained with a rap about atoms being quantum computers, and the telepaths’ quantum wetware minds getting entangled with the “minds” of the atoms. You can make insubstantial illusions simply by selectively tweaking the refractive index of the air. And for objects, you go ahead and do a transmutation of matter routine.

But I still need to involve the oddball. How is it letting people make wacky matter? Maybe the oddball is helping with the entanglement part.

And, the payoff part, what can the oddball and the wacky matter do? What’s in the back pages of the instruction manual?

I imagine exploding an object into atoms, but have the atoms remember where they came from so you can play the explosion backwards. Like the atoms were connected to their original locations by rubber-band spacetime threads.

I want my qwet-heads to reach the Big Aha, which might be the light visible between our thoughts, the white light of the Void.

Naturally the oddball and wacky matter will pose a threat to the continued existence of the world. The world is a consensus illusion, and the oddball might nudge everyone/everything out of this illusion. We might lose our balance like a tightrope-walker looking down past the rope to the yawning chasm below.

The oddball will want to reproduce. In its initial state, it was blocked from so doing. Unwittingly my artist character Zad helps it begin to spread. He incorporates the oddball into one of his new sculptural artworks, hoping to enhance his work for a big come-back show at the Idi Did gallery. But then the work eats the gallery—and most of downtown Louisville, Kentucky.

Also I need to limn the origin of the oddball. Possibly a wetware hacker made the oddball, partly by accident. Perhaps it evolved—but could the evolution have been directed by…the Big Aha?

[A visit from the Golden Age computer theorist, Ted Nelson.]

One scene I want to do, it’s the ultimate “spaced friend” scene. My character Junko appears one morning and, thanks to the oddball and wacky matter, she’s altered the dimension signature of the spacetime in her body. Her body has, like, two-dimensional time and two-dimensional space. She slides into the commune’s morning breakfast room, sliding across the floor.

“Rough night, Junko?”

Don’t write the bogosity generator, let the bogosity generator write you.

January 23, 2013

Teep Scenes

So I’m still working on my novel The Big Aha. I reached the halfway point about a week ago. And then I ran into what my old mentor Robert Sheckley called a “black point.” I can’t see the land that I sailed off from, and I can’t see the land I’m sailing towards. A black zone in the sea of story. Whither now?

One obvious step that I took is to print out the first half of the novel and begin rereading it and marking it up. The process gives me a feel for where I am. Also it smoothes out the earlier stuff to match with where I’ve progressed to during this unpredictable growth if this particular “magic beanstalk.” Doing the revision can give me some momentum for the next chapter. And I can take inventory of the various plot threads that I already planted. Pretty soon now I ought to begin reeling them in.

Another thought is that I might as well put in an evil, psychotic, ruthless, murderous, half-mad human villain. I’ve often shied away from using characters like this, as I find them to be unrealistic and counterrevolutionary. That is, (a) I’ve never met anyone that’s really evil like that, and (b) presenting images of such bogeymen is in bad for the public discourse in that it promotes hysterical fear that leads to blind acceptance of police-state-style security measures. Usually, when I have a villain, they’re presented with a modicum of sympathy—like the tortured Jeff Luty in Postsingular. But maybe not this time.

After all, I’m only spinning a tale here, a fairytale, really, so why not have an utterly unsympathetic ogre or a witch? The mad killer is a traditional action-fiction plot device. No need to turn up my nose at this time-honored move. Intense puppet-show conflict is good for the story, it gets the readers’ pulses pounding, and the villains work to set up good ticking-clock crisis scenes— will he kill again?

Looking forward to the next chapter, I’d like it to be an homage/evocation of the psychedelic Sixties. I want something of the flavor of William Craddock’s Be Not Content. .

Maybe even with an introductory line like: “I’m going to fast-forward through the following weeks, hitting highlights. Thanks to our budding scene, people all over the world would be doing qwet teep by the end of November. And then of course, the big problems with fairyland would kick in. But at the start, everything was good. We were turning people on. For many of us, life took on the feeling of a joyful waking dream.”

My rough idea of the flow is that, as I mentioned, more and more people are drawn into qwet—which (a) gives you the ability to jam your head into a trippy “cosmic” mode and (b) gives you a kind of teep, or telepathy, with the other qwetties.

I think of Leary’s Millbrook redoubt, with seekers coming to dabble in acid. I also see the cops starting to bug them. And we want a crisis involving the emerging parallel reality called fairyland.

I’d like giant group qwet teep session, sort of like an orgy, or maybe like an early Stinson Beach Acid Test party or a Furthur bus scene—only it’s in Louisville, Kentucky. And, while deep into the trip, the participants can pick up echoing vibes from qwet teepers in some other town, maybe New York, or maybe just Cincinnati.

Two months seeming like two years. Someone develops an ability to “bookmark” past psychic states, and hops up and down the timeline. Someone else gets stuck in a loop, circling around one particular instant over and over again.

A shrill argument that quantum amplifies out until a building collapses. The qwetties dust themselves off, laughing in the rubble, then restore the structure by talking to the individual atoms. The arguing couple swap personalities. Or mesh, exchanging only the contents of their left brains.

A guy gets fully into the consciousness of a housefly, absent-mindedly slaps it and kills it when it crawls into his nose, he freaks out, spends a day as a dead fly, oozes back. Some qwet tripper gets stuck in the alternate reality of fairyland, and only a few pieces of them come back.

A dream you can’t wake up from. Or you do wake up, but only into another dream, level upon level, transfinitely many of them. Someone gets an early premonition of the Big Aha beyond it all. Beyond mundane reality, beyond fairyland.

“Ve going to za Vite Lite, my friend. Yaveh’s house.“

January 14, 2013

Charles Stross’s RULE 34 — And the Nature of Mind

Before reading Charles Stross’s novel Rule 34, I’d been under the misapprehension that the title was referring to cellular automata or CAs.

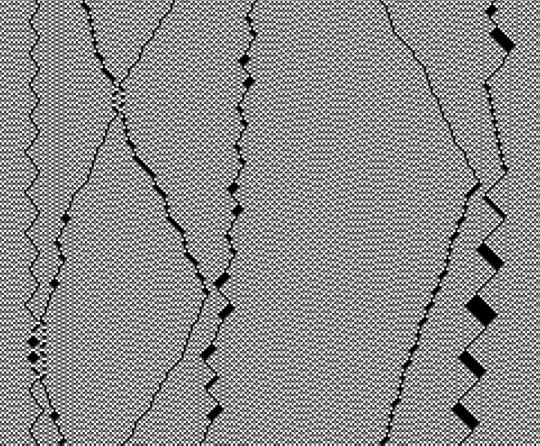

[A reversible 1D Ca rule that I dubbed “Axons” in my and John Walker's Cellab package.]

In the 1980s, the computer scientist Stephen Wolfram enumerated the simplest possible CAs in a list numbered from 1 to 255. Rule 30 is a very good generator of pseudorandom sequences, and Rule 110 is in fact a universal computer, capable of emulating any possible computational process. The CA Rule 34 is, however a very dull one, which produces patterns of parallel diagonal lines.

But it turns out “Rule 34” is hacker slang for the dictum: “If it exists, there is porn of it. No exceptions.” (You can find a nice summary of internet rules in this 2009 essay.)

So…Rule 34. Bowling ball porn? Check. Squid porn? But of course. Lightbulb porn? No doubt. Sally Field? Please no.

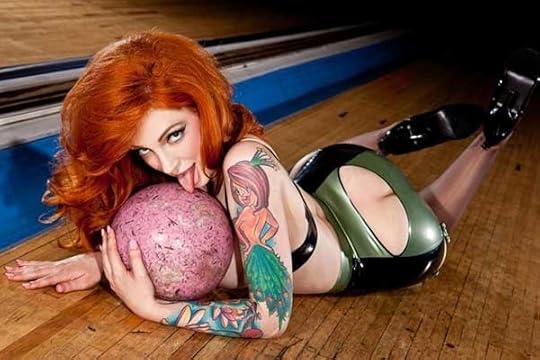

[Spicy photo of the divine Vanessa Lake with bowling ball, © Vanessa Lake 2012 --- found on a Tumblr site called “A Purple Haze of Porn and JD.”]

You can test Rule 34 for whatever entity ____ you want by Googling “porn ____” and then selecting the Image option on the Google results page. You might want to adjust your Safe Search filter level to an ‘adultness’ level you’re comfortable with. Alternately, try searching “Tumblr porn ____” The reason for narrowing down to Tumblr sites is that these pages aren’t encrusted with intense adware (and possible malware).

Anyway, the heroine of Stross’s novel Rule 34 is working in the playfully dubbed “Rule 34” branch of the Edinburgh police department, tasked with investigating the more kinky and dangerous things that the online locals might be getting up to.

In recent years, Charles Stross has become my favorite high-tech SF writer. And he’s not working in the sterile, Arthur Clarke mode of futurology, no, he’s writing druggy, antiestablishment satire, in some ways similar to cyberpunk—a mix of nihilistic humor and apocalyptic speculation. (Here’s a page listing Stross’s US editions.)

In 1995, I read Stross’s novel/story-sequence Accelerando. For several years before this, SF writers have been p*ssing and moaning and saying, “Gosh, we really can’t see past the Singularity.” And then Stross just goes in there and plows ahead. Machines as smart as gods? Why not. Hell, even the Greeks knew how to write about gods. You just do it. Pile on the bullsh*t and keep a straight face.

Accelerando gave me the courage to write my own Singularity novel—which I called Postsingular — it exists in paperback, ebook, and free CC editions. See also the sequel, Hylozoic.

The notion of a Singularity became a quasi-religious belief among some techies, a millennial conviction that computers would essentially eat everything and we’d all be living in a giant videogame. Stross and Cory Doctorow took this line of thought to a maximal level in their recent novel/story-sequence Rapture of the Nerds, quite a wiggy romp.

But Stross and Doctorow aren’t Johnny One-Notes, not messianic Singulatarians. That whole rap is just one particular goof. Stross’s Heinlein-inspired far-future novel Saturn’s Children is more like retro, old-school SF, a book in which the author actually worries about things like rockets having enough fuel to fly from planet to planet within our solar system. And Doctorow’s engaging novels Makers and Little Brother and Pirate Cinema are tightly linked into near-future possiblities—the latter two might even be viewed as insurrectionary manuals for our youth.

Coming back to Stross’s Rule 34 , this book, like its loose prequel, Halting State , are quite close to the present-day world. It’s a world where some AI type behaviors have emerged among the applications that run on the Web. What do we mean by AI?

Stross observes, “If we understand how we do it, it isn’t artificial intelligence anymore. Playing chess, driving cars, generating conversational text… Perhaps we overestimate consciousness?”

He makes the point “We’re not very interested in reinventing human consciousness in a box. What gets the research grants flowing is applications.”

And, again: “general cognitive engines [are all] hardwired [to] project the seat of their identity onto you … what we really want is identity amplification.”

In my opinion if you have a really effective AI system, it’s in fact pretty easy to give it a sense of having a conscious self. It’s basically just a matter of equipping your program with a mental image of itself. Here’s a summary of my views of consciousness and AI:

(Thesis) The slowly advancing work in AI seems to indicate that any clearly described human behavior can be emulated by a machine— if not by an actually constructible machine, then at least by a theoretically possible machine.

(Antithesis) Upon introspection we feel there is a mental residue that isn’t captured by any scientific system; we feel ourselves to be quite unlike machines. This is the sense of having a soul.

(Synthesis) Sensing that you have a soul—or, more simply, feeling a sense of “I am”— can be modelled by equipping your mental computation with a self-symbol, setting up a “movie-in-the-brain” emulation of the self-symbol in the world, and then going one step further to tabulate the ongoing feelings of your self-symbol as it watches the mental movie. And the program watches the movie, and itself in the movie, and the tabulations of its feelings about itself and the movie…and that’s what it means to be conscious.

I admit that the synthesis step is a little confusing the first time you hear about it. I had to think about it for several years before it made sense. And, truth be told, I’m still revising it every time I come back to it. I got the idea from Antonio Damasio, The Feeling of What Happens. And I write about it in my tome, The Lifebox, The Seashell, and The Soul, available in paperback or in sample form as a free online PDF file — here’s a link to the section relevant to what I’m talking about here: Section 4.4 of Rucker’s LIFEBOX Tome: “I Am”.

And here’s an illustration from that section, showing a game-design-style sequence of building up to the simulation of consciousness…and on beyond conscousness to empathy. I was teaching courses on videogame programming when I came up with this picture.

Left to right and top to bottom, the six cartoon frames represent, respectively:

immersion *** seeing objects

movie-in-the-brain with proto-self *** feelings

core consciousness *** empathy

(The core consciousness is represented as a weighting table of “feelings” here.)

“I seem to be…an ever-changing lookup table.”

But I’m off on a tangent here—emulating consciousness isn’t a main theme in Rule 34 —although, near the end, Stross can’t resist dropping the reader into the stream of consciousness of an intelligent program.

Most of the novel works to dramatize the fact that we can go a long way towards the illusion of intelligence with a large database, some clever search software and a smidgen of creative intelligence. To some extent, we’re simply beating the problem to death by having faster and bigger computers.

Where does that extra pinch of AI come from? Do we need a big insight into how we think? Maybe not. The AI programming method known as neural nets works by letting a machine program learn and get smarter. Given enough time and hardware, it may be that neural nets can bring us to something that feels AI. Even though we won’t know, in any exact sense, how it works. So, once again, we’ll just have a huge data base with a neural net that’s self-evolved a zillion effective weights to put onto the links between inputs and possible outputs.

(A great description of this process can be found in an excellent but less-than-well-known book On Intelligence by Jeff Hawkins and Sandra Blakeslee.)

The end result is a construct too complicated to design. It can only evolve. Stross sees the evolution as happening “in the wild,” that is, in the context of AI spam generators versus AI smart filters. “…much span is generated by drivel-speaking AI, designed purely to fool the smart filters by convincing them that it’s the effusion of a real human being… Slowly but surely the Turing Test war proceeds…”

[A neural net that takes a bundle of pixel-level inputs and decides what expression a face has.]

On another note, I relished Stross’s wry and realistic view of which of our past dreams do and do not come true:

“Even when they’re working, online conferencing systems just aren’t quite good enough to make face-to-face meetings obsolete. Working teleconferencing is right around the corner, just like food pills, the flying car, and energy too cheap to meter.”

And: “Reliable automatic face recognition is right around the corner next week, next year, next decade, just like it’s always been.”

Last week, I was nearly scammed by some Nigerian(?) people (or bots) who pretended to invite me to give a talk in London, all expenses paid, with a good speaker’s fee, under the condition that I obtain a UK work permit which would, it slowly came out, cost $1400, to be paid in cash via Western Union (and at this point I balked). What made the scam initially believable was that a variety of different addresses were emailing me about it. Stross explains this tactic in Rule 34.

“I have Junkbot establish a bunch of sock puppets… Junkbot then engages [the target person] in several conversation scripts in parallel. A linear chat-up rarely works—people are too suspicious these days—but you can game them. Set up an artificial reality game … built around your victim’s world, with a bunch of sock puppets who are there to sucker them into the drama.”

The Phil Dick option: What if all your email friends are sock puppets? What is it that they’re trying to make you do?

January 8, 2013

Art Show & Reading At Borderlands Books

I’m venturing forth from my office this weekend to do some promo at Borderlands Books at 866 Valencia St. in San Francisco.

I’ll be hanging a show of my paintings in the Borderlands Books café with a reception on Friday, Jan 11, 5-7 pm. And I’ll give a reading and Q&A session for my novel Turing & Burroughs: A Beatnik SF Novel on Saturday, Jan 12, at 3 pm—you can visit with the paintings then as well.

View of my home office from my desk chair. Click for a larger version of the image.

I number my paintings, and I have an overview image of all my paintings below, showing paintings #1 – #94. The pictures in the show will from the bottom rows, that is, in the range #79 – #94. Further down in today’s post I’ll put in images of the individual pictures that will be in the show, with notes on each picture. The pictures are for sale, and you can also buy prints of them online or (for a few of them) at Borderlands Books. The prices of the paintings can be found on my paintings page.

Overview of my paintings. Click for a larger version of the image.

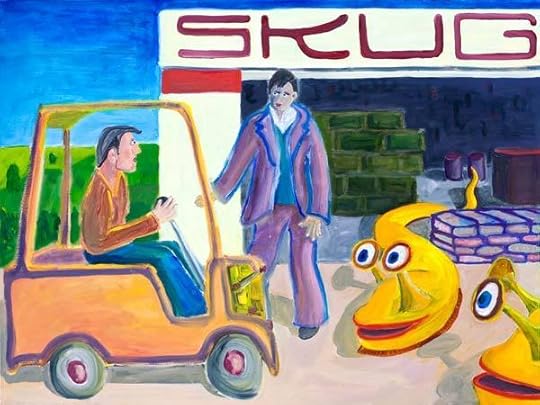

All the pictures I’ll be showing have not been shown before, except for one, Turing and the Skugs, which relates to my Turing & Burroughs novel. This older picture appeared in my last Borderlands Books cafe show, which was in November, 2010.

“Turing and the Skugs”, 40″ x 30″ inches, Oct 2010, Oil on canvas.” Click for larger version.

I made Turing and the Skugs while gearing up for my Turing & Burroughs novel involving the computer pioneer Alan Turing, the beatniks, and some shape-shifting beings called skugs. I got the word “skug” from my non-identical twin granddaughters, aged three. When I used visit my son’s house in Berkeley, I always liked to open up his worm farm and study the action with the twins. We found a lot of slugs in there, and we marveled at them. The girls tended to say “skug” rather than “slug,” and I decided I liked the sound of this word so much that I’d use it for some odd beings in my novel. I’m supposing that Turing has carried out some biochemical experiments leading to the creation of the skugs. Here we see Turing outside the Los Gatos Rural Supply Hardware garage, with two skugs backing him up. Alan is meeting a handsome man who may well become his lover. Unless the skugs eat the guy.

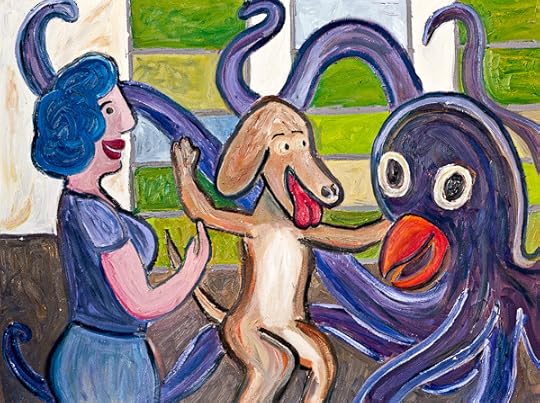

“A Skugger’s Point of View”, 40″ x 30″ inches, January, 2011, Oil on canvas.” Click for larger version.

In A Skugger’s Point of View I wanted to render an extreme first-person point of view…in which we see the dim zone around a person’s actual visual field. The person in question is the Alan Turing character in my novel The Turing Chronicles. He has become a mutant known as a “skugger,” and he has the ability to stretch his limbs like the cartoon character Plastic Man. He’s traveling across the West with two friends, a man and a woman. In this scene, Turing’s cohort is being attacked by secret police, one of whom bears a flame-thrower. Turing is responding by sticking his fingers into their heads, perhaps to kill them, or perhaps to convert them into skuggers as well. We can see Turing’s arms extending from the bottom edge of his visual field. Even though it’s not quite logical, I painted in his eyes as well because they make the composition better

“V-Bomb Blast”, 40″ x 30″ inches, July, 2011, Oil on canvas.” Click for larger version.