Rudy Rucker's Blog, page 39

October 30, 2012

Oblivious Teep

Today’s short post recapitulates my previous one, with a little more detail. I’m obsessed with a new concept of telepathy (or teep) just now, as I want to work it into this novel I’m getting started on. Today’s post is, by the way, lifted from my latest draft of the novel, and this means that I’ve sanded and smoothed it down quite a bit.

Teep plays a big part in the tale I’m telling you, and I need to say a little more about it. Teep has to do with what my inventor friend Gaven called quantum psychology.

If you ever take a serious look inside your own head, you’ll notice that have two styles of thought. Let’s call them the “robotic” and “cosmic.” Robotic thought is all about reasoning and analysis. Cosmic thoughts are wordless. It’s easy to be dominated by your endlessly-narrating inner robotic voice. Step past the voice and you can see the cosmic mode. Analog consciousness, like waves on a pond. Merged with the world. Without any opinions.

Ordinarily your mind oscillates between the cosmic and the robotic at a rate of about ten cycles per second. Having both modes helps you get by. The cosmic state is a merge into your surroundings, and the robotic state is when draw back and say, “Okay, it’s me against the world, now I’ll plan what I do next to stay alive.”

Gaven’s technical discovery was that we have a specific physical brain site that controls when our state of consciousness flips between the cosmic and the robotic. And for a joke he called the site the gee-haw-whimmy-diddle [Just click the X to get past the “subscribe” pop-up on this site].

So, okay, your gee-haw-whimmy-diddle controls when your consciousness flips back and forth between the cosmic and the robotic. And Gaven’s quantum wetware tweak of the gee-haw-whimmy-diddle allowed you to keep your mind in the merged cosmic state for a longish period of time.

So how does that lead to teep? From a physicist’s point of view, your mind isn’t your physical brain. Your mind is a Hilbert space wave function that happens to look like a brain. Matter and wave, one and the same. And if you and someone near you are both in the merged cosmic state, then your quantum wave functions can overlay into a single combined wave system. And that’s teep.

Your brain waves overlay each other to make moiré, op-art, watered-silk type patterns. And that’s some serious dark beauty, qrude.

I know I’m droning on for too long. It’s like I’m an old-school professor who’s tap-tap-tapping his piece of chalk on his freaky, dusty blackboard. But there’s one more gotcha I have to tell you about.

The thing is, whenever you make a mental note about what you’re experiencing, you automatically bust your mind state down into the robotic mode. And any teep connection breaks. As long as you’re staying in the teep state, you’re cosmic, and you’re not laying down any organized memories.

Putting it another way, qwet teep is oblivious. As in unseeing, unaware, ignorant, forgetful. This means that when you teep with someone, your memories of the trip will be as vague and flaky as the memories of a dream.

October 24, 2012

The Two Mind Modes. Telepathy.

I’ve been circling around and around some ideas that I want to use in my next novel, The Big Aha. In today’s post, I’ll expand on some of the remarks in my October 15, 2012, post, “SF Religion 3: Qwet.” But my focus isn’t on religion in today’s post, it’s on the nature of mind and the possibility of telepathy.

Open your (inner) eyes to your true mental life. Your state of mind can evolve in two kinds of ways that I’ll fancifully call—“robotic” and “cosmic”. The “robotic” mental processes proceed step-by-step—via reasoning and analysis, by reading or hearing words, by forming specific opinions. Every opinion diminishes you.

The “cosmic” changes are preverbal flows. If you turn off your endlessly-narrating inner voice, your consciousness becomes analog, like waves on a pond. You’re merged with the world. You’re with the One. It can be a simple as the everyday activity of being alert—without consciously thinking much of anything. In the cosmic mode you aren’t standing outside yourself and evaluating your thoughts.

The cosmic mode is what’s happening between/behind/around your precise robotic communicable thoughts. The idea is to notice the spaces between your thoughts, or to avoid being caught up in your thoughts. This is a fairly common meditation exercise.

We might have some specific brain sites that control when our state of consciousness flips from being with the One, that is, in a smooth, mixed, continuous or “cosmic” state—of being with the Many, that is, down to the “robotic,” specific-opinion state. If you’re a dreamy sort of person, your natural trend is to drift out to unspecificity, out the One. But other personality types tend always to be pushing down into the robotic, studying the details of the Many.

I’m imagining a qwet treatment that helps you can get into—and remain within—a smooth state for a longish period of time.

As I’ve often said, I have the experiential sensation that my mind oscillates between One/Many about sixty times per second. Between the “cosmic”/”robotic” consciousness modes. You do need both modes to get buy. The One state is like a radar ping you reach out into the world around you, and the Many state is when you say, “Okay, I’m alone here, it’s me against the world, what do I do next to stay alive?”

Breaking away from the cosmic mode can be thought as involving a quantum collapse. You go from a broader, more ambiguous state to a more specific state. How does the collapser work? It affects not just you, but the things that you’re looking at and coupled to. Everything around you becomes overly precise, that is, robotic instead of cosmic. Less interesting. Like—think of they way that some people can make a whole scene dull just by the way they start talking about it. “How much did that cost? Is that safe to have around? Did you notice the scratch on it?”

Do animals have collapsers? Do physical objects? Let’s say “not usually.” Might the ability to collapse be connected to having consciousness? Let’s say “yes.”

What if I use the Antonio Damasio’s definition of consciousness as “the ability to visualize yourself visualizing yourself.” You can watch a model of yourself watching yourself. It’s a three-level map. Actor, strategist, analyst. The actor just does things, like an animal. The strategist observes the actor and makes corrections. The analyst observes the strategist’s decisions and improves on them.

Suppose that this is a kind of physical map, a three-tier flow of quantum information, and that for a fixed-point theorem type reason, these flows cause quantum collapse—they throw a system into an eigenstate, that is, into a robotic, non-cosmic, fixed point. Humans are the main things that are three-tier collapsers, but such collapsers do occur naturally in certain places, just as certain types of crystals or mirrors might be found in nature. The spots with collapsers seem to have bad juju, that is, they’re inherently boring.

I see the collapsers as being like snags in a rushing muddy river of quantum flow. And the snags leave precise ripple wakes. And there can be a kind of beauty to the moiré patterns of the overlaid wakes—this is what we call our human culture.

In my novel, I want to work with the idea that managing to stay in the uncollapsed cosmic state, they can achieve a kind of telepathy. You can couple your “cosmic” mental state to the “cosmic” state of another person. I won’t be like a phone conversation. Your thoughts aren’t at all like a page of symbols—they’re blotches and rhythms and associations.

Key Plot Point: For quantum theoretic reasons, a quantum link between the two systems isn’t of a kind that can leave memory traces, otherwise the link is functioning as an observation that drags consciousness back down to the robotic mode. So you can’t directly exchange specific, usable info via quantum teep. In my novel this will be a disappointment to the government backers of the qwet experiments.

But your mind state will be changed by your teep interactions. But not in the obvious way of “remembering what they ‘said’.” After teeping with someone, when you later drop back down into your chatty “robotic” state, you’ll find that you are saying things you wouldn’t have said before the merge. But maybe you’re not sure why.

This isn’t so different from a memory of a very deep, close, intense conversation with someone—a talk where you really got onto the same wavelength. Like a talk in bed with a lover, or chatting happy with a pal, or, getting into deep concepts with an admired mentor—telepathy happens.

October 21, 2012

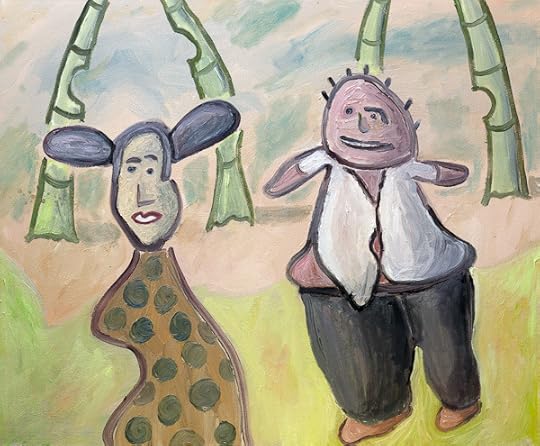

Hard Sell By The Louisville Artist

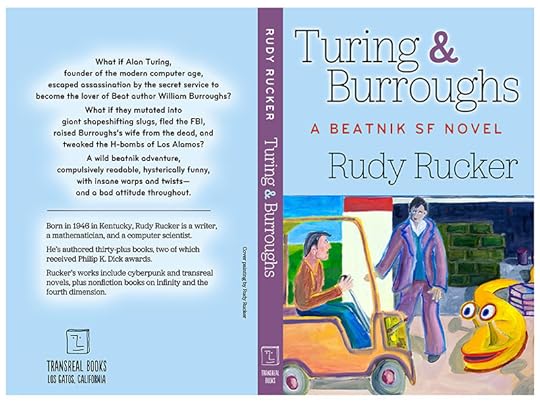

Did you know that I grew up in Louisville, Kentucky? Here’s a new oil-painting I did, kind of a parodistic self-image riff, it’s called “Louisville Artist.” And the woman? Well, she might be my muse, or my wife, or a Japanese-Californian wetware engineer character from the next novel I hope to write.

And that’s me on the right of course. Shirt all untucked and with no fingers on my hands, I’m here to buttonhole you, urging you to buy a copy of my new novel Turing & Burroughs.

I’ve knocked the price of the ebook down to $3.95, and we’ve got paperback editions for less than $16 at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Still unsure? I’ve got some background info on the book’s home page, including a Locus Online review by Paul De Filippo.

And you can browse the whole book as a web page!

I’m looking for readers here, minds to feed, souls to win. So I’ve even got a whole range of free downloadable Creative Commons licensed editions. Read the whole darn thing for free, if you want.

But it’d be nice if you’d buy a version.

The book’s a lot of gnarly fun.

October 15, 2012

SF Religion 3: Qwet

This is my third post on SF religion, and I probably won’t post on this again for awhile. I’m interested in the topic these days as I’d like to have the founding of a religion be a plot element in my next novel, The Big Aha.

I’ll start with a physical process that produces an unusual state of consciousness. And then I’ll trace out the sense of excitement and personal liberation among the adepts; the wider public’s incomprehension and fear; the denunciations and attacks from the politicians and the exponents of existing religions; and the inescapable international tsunami of interest.

I want the catalyzing, mind-altering spark to be something involving quantum mechanics. Not a drug. A technique of mind-alteration that’s literally physics-based. I’m going to call it qwet, which is short for quantum wetware. The users of this technique are called qwetties.

In a nutshell, qwet gives you a certain type of telepathic power—called teep for short. You can share the mind states of other people, and animals and, to some extent, the “mind states” of plants and objects. You’re sharing the states in the sense of merging-into, rather than in the sense of observing-from-the-outside.

At the end of today’s post I’ll say a little more about the nature of quantum wetware and about how this quantum-mediated teep is going to work.

But first let me talk about some models for the birth of a modern religion. The psychedelic movement was in some ways an event of this kind. And it was based upon science, that is, upon the use of a specific newly-discovered synthetic chemical. The idea of a physical or chemical process that leads to a cult or a religion is very SFictional.

It’s easy to replace LSD by qwet teep and recast the cultural history of the psychedelic revolution: the early voices-in-the-wilderness Beats, Tim Leary’s high-minded proselytizing, the Pranksters’ street psychedelia, and then the mass fad, complete with convivial freakouts and light shows.

I see a qwettie wearing a button: Are you qwet yet?

How do we get from qwet as a method to qwet as a religion? The acidheads were interpreting a certain brain phenomenon in religious terms—what you might call experimental of mysticism. But street psychedelia never attained the status of a sanctioned religion—although the traditional Peyote Religion did find cover as the Native American Church.

Mormonism is another intriguing model of a modern religion. The underlying physical object here is the Book of Mormon, said to have been found inscribed on golden plates and deciphered via two “stones of sight” called Urim and Thummim. What if the plates had been left on Earth by a UFO? Or what if they’d welled up from a hidden, subdimensional level of reality? Not that I want to pick on the Mormons. We could ask the same kinds of questions about the origins of any religion.

But this move interests me: what if the techniques of quantum wetware were unearthed rather than invented? What if the qwet rats from Dimension Z fed them to us?

Yet another modern-religion story is that of Dianetics/Scientology. As I understand it, Dianetics was originally a scientifically inspired tool for exploring one’s personality—the E-meter, a fairly simple device that measures the changing resistance of a person’s skin—not unlike a simple lie detector. In order to fend of unwelcome government scrutiny of his E-meter technique and of any health claims made for it, L. Ron Hubbard changed his movement to a religion, that is, to Scientology, and the E-meter results were now viewed as religious phenomena rather than as diagnostic medical results. This origin story provides a scenario I could use in my book.

(As with Mormonism, I don’t mean to disparage Scientology. I’m only mentioning these two religions in somewhat abstract way—in terms of historical patterns that might play out in my SF novel. I don’t want my comments thread to become a battleground! To this end, I’m going to be blocking out comments advocating or criticizing these religions. I’d much prefer that you comment on Qwet!)

Getting back to my main line of discussion, I can see a situation in which the qwet technique might initially be viewed as a practical communication channel, or as an empathy-promoter, or simply as an offbeat mind-toy. But then it evolves into the Qwet religion. The switch might initially be a tactic to forestall some type of governmental crackdown.

But then we’ll get an SF kicker—a big aha—whereby there are in fact some higher-level beings revealed by the qwetties’ telepathic visions. Weird and otherworldly experiences. Odd critters living behind straight-reality’s sets. Like rats on a sound stage.

Qwet is real!

So what is quantum wetware and how does it give you telepathy?

(In a way, “quantum wetware” is a pleonasm, like “hot fire.” I’m using wetware to mean a person’s biological material, viewed as a kind of computer. Not just the DNA, but all the other chemicals as well. The interactions of these complex biochemical molecules are ruled by quantum mechanics. So any wetware is already in some sense quantum.)

This said, our PowerPoint descriptions of something like DNA often depict it in a classical-physics, Tinker-toy, Turing-machine kind of way. Indeed, there really is a crisp, mechanistic quality to the actions and reactions of our bodies’ proteins and enzymes. Quantum mechanics is the playing field, but the players are solid little lumps.

But now I want to get away from that. Since it’s states of consciousness I’ll be talking about, I’m particularly interested in having neurons and neurotransmitters that are in the so-called mixed states of quantum mechanics. Not yes, not no, but both.

And if you get some quantum catalyst in your system (it’s transmitted like a sexual disease), all of your bodies processes can take on a fey, QM quality. And this is going to lead to telepathy, a.k.a. teep.

One way of starting to imagine telepathy: my thoughts aren’t at all like a page of symbols—they’re blotches and rhythms and associations. Open your (inner) eyes to your true mental life. A related notion that continues to inspire me is the mind-as-quantum-system notion that my philosopher-sage friend Nick Herbert calls quantum tantra.

Your state of mind can evolve in two kinds of ways that I’ll fancifully call—“robotic” and “cosmic”. The “robotic” mental processes proceed step-by-step—via reasoning and analysis, by reading or hearing words, by forming specific opinions.. Every opinion diminishes you.

The “cosmic” changes are preverbal flows in which several opinions can co-exist. If you turn off your endlessly-narrating inner voice, your consciousness becomes analog, like waves on a pond. You’re merged with the world. It can be a simple as the everyday activity of being alert—without consciously thinking much of anything. In the cosmic mode you aren’t standing outside yourself and evaluating your thoughts.

As Nick Herbert has explained in his “Quantum Tantra” essay that you can find in the link that I mentioned above, it’s natural to regard the cosmic, analog mental process as essentially quantum mechanical. And once you’ve got QM happening, you can get quantum entanglement, whereby you couple your “cosmic” mental state to the “cosmic” state of another person, or even to the state of another object.

For quantum theoretic reasons, the link between the two systems isn’t of a kind that can leave memory traces, otherwise the link is functioning as an observation that drags consciousness back down to the robotic mode. So you can’t directly exchange specific, usable info via quantum teep. (And in my novel this will be a disappointment to some government backers of the qwet experiments.)

But your mind state will be changed by your teep interactions. And whenever you drop back down into the chatty “robotic” state, you’ll find that you are saying things you wouldn’t have said before the merge.

One more hit: Synchronicity might be evidence that we’re all parts of some higher being. The higher mind’s cosmic states filter down into surprising links within our mundane robotic reality.

And—look out!—here come the qwet rats!

What might be some rituals of the Qwet religion? Once I was at the Esalen Institute south of Big Sur with Terence McKenna. He and I were leading a seminar entitled “Wetware and Stoneware.” A cute woman in the group was talking about “sacred dancing.” Cheryl from Carmel—she was a follower of Terence’s, and she talked about driving up from Esalen to the River Inn in Big Sur to get in some sacred dancing. By way of explaining this, she held her upraised hands together and moved her head back and forth.

If you have qwet teep, you can do sacred dancing without having to be in the same place as the other dancers, and there doesn’t have to be an audible sound. I’m thinking of a Silent Disco scene I saw at the San Jose Zero1 Biennial this September, where each dancer had a pair of earphones, and we were dancing in a virtual soundscape.

[As mentioned above, I'll be curating the comments on this post, so please don't try posting any passionate screeds pro or con existing religions. Other than that, we're wide open.]

October 8, 2012

SF Religion 2: Xiantific Mysticism

I’m presently working on a novel called The Big Aha in which I might have my characters be involved in a religion based on the experience of telepathy. The telepathy is brought on by a (SFictional) biophysics maneuver that I’m calling quantum wetware.

The idea of having a religion based on an actual physical phenomenon is intriguing. One model for this kind of sociocultural phenomenon would be the quasi-religious attitude of the first acidheads in the late 1960s. But in my novel want the movement to emerge from something other than drugs.

Over the years, I’ve thought of two religions whose birth I could be involved with. The first is The Church of the Fourth Dimension, an idea invented by the famed and beloved science writer Martin Gardner in one of his columns. Maybe I’ll blog about that another time.

The religion I want to post about today is what I might call Xiantific Mysticism. “Xiantific” has a nice sound to it—the rebellious leading X, the conflation with Christian=Xian, and the pronunciation Xiantific=Scientific. I called this “religion” Scientific Mysticism in my novel Master of Space and Time. It relates to my essay, “The Central Teachings of Myticism,” which I posted about a few days ago.

Here’s a passage from Master of Space and Time, featuring an encounter between my characters Joe Fletcher and Alwin Bitter. Alwin Bitter is actually a carry-over character from my earlier novel The Sex Sphere. And he’s a member of the Church of Scientific Mysticism.

Sunday morning we went to church, the First Church of Scientific Mysticism. The religion, vaguely Christian, had grown out of the mystical teachings of Albert Einstein and Kurt Gödel, the two great Princeton sages. My wife Nancy and I didn’t attend regularly, but today it seemed like the thing to do. According to the evening news, a giant lizard like Godzilla had briefly appeared on the Jersey Turnpike.

The sun was out, and the two of us had a nice time walking over to church with our daughter Serena.

The church building was a remodeled bank, a massive granite building with big pillars and heavy bronze lamps. Inside, there were pews and a raised pulpit. In place of an altar was a large hologram of Albert Einstein. Einstein smiled kindly, occasionally blinking his eyes. Nancy and Serena and I took a pew halfway up the left side. The organist was playing a Bach prelude. I gave Nancy’s hand a squeeze. She squeezed back.

Today’s service was special. The minister, an elderly physicist named Alwin Bitter, was celebrating the installation of a new assistant, a woman named — Sondra Tupperware. I jumped when I heard her name, remembering that my friend Harry Gerber had mentioned her yesterday. Was this another of his fantasies become real? Yet Ms. Tupperware looked solid enough: a skinny woman with red glasses-frames and a Springer spaniel’s kinky brown hair.

Old Bitter was wearing a tuxedo with a thin pink necktie. The dark suit set off his halo of white hair to advantage. He passed out some bread and wine, and then he gave a sermon called “The Central Teachings of Mysticism.”

His teachings, as best I recall, were three in number: (1) All is One; (2) The One is Unknowable; and (3) The One is Right Here. Bitter delivered his truths with a light touch, and the congregation laughed a lot — happy, surprised laughter.

Nancy and I lingered after the service, chatting with some of the church members we knew. I was waiting for a chance to ask Alwin Bitter for some advice.

Finally everyone was gone except for Bitter and Sondra Tupperware. The party in honor of her installation was going to be later that afternoon.

“Is Tupperware your real name?” asked Nancy.

Sondra laughed and nodded her head. Her eyes were big and round behind the red glasses. “My parents were hippies. They changed the family name to Tupperware to get out from under some legal trouble. Dad was a close friend of Alwin’s.”

“That’s right,” said Bitter. “Sondra’s like a niece to me. Did you enjoy the sermon?”

“It was great,” I said. “Though I’d expected more science.”

“What’s your field?” asked Bitter.

“Well, I studied mathematics, but now I’m mainly in computers. I had my own business for a while. Fletcher & Company.”

“You’re Joe Fletcher?” exclaimed Sondra. “I know a friend of yours.”

“Harry Gerber, right? That’s what I wanted to ask Dr. Bitter about. Harry’s trying to build something that will turn him into God.”

Bitter looked doubtful. I kept talking. “I know it sounds crazy, but I’m really serious. Didn’t you hear about the giant lizard yesterday?”

“On the Jersey Turnpike,” said my wife Nancy loyally. “It was on the news.”

“Yes, but I don’t quite see — ”

“Harry made the lizard happen. The thing he built — it’s called a blunzer — is going to give him control over space and time, even the past. The weird thing is that it isn’t really even Harry doing things. The blunzer is just using us to make things happen. It sent Harry to tell me to tell Harry to get me to — ”

Bitter was looking at his watch. “If you have a specific question, Mr. Fletcher, I’d be happy to answer it. Otherwise … ”

What was my question?

“My question. Okay, it’s this: What if a person becomes the same as the One? What if a person can control all of reality? What should he ask for? What changes should he make?”

Bitter stared at me in silence for almost a full minute. I seemed finally to have engaged his imagination. “You’re probably wondering why that question should boggle my mind,” he said at last. “I wish I could answer it. You ask me to suppose that some person becomes like God. Very well. Now we are wondering about God’s motives. Why is the universe the way it is? Could it be any different? What does God have in mind when He makes the world?” Bitter paused and rubbed his eyes. “Can the One really be said to have a mind at all? To have a mind — this means to want something. To have plans. But wants and plans are partial and relative. The One is absolute. As long as wishes and needs are present, an individual falls short of the final union.” Bitter patted my shoulder and gave me a kind look. “With all this said, I urge you to remember that individual existence is in fact identical with the very act of falling short of the final union. Treasure your humanity, it’s all you have.”

“But — ”

Bitter raised his hand for silence. “A related point: There is no one you. An individual is a bundle of conflicting desires, a society in microcosm. Even if some limited individual were seemingly to take control of our universe, the world would remain as confusing as ever. If I were to create a world, for instance, I doubt if it would be any different from the one in which we find ourselves.” Bitter took my hand and shook it. “And now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got to get home for Sunday dinner. Big family reunion today. My wife Sybil’s out at the airport picking up our oldest daughter. She’s been visiting her grandparents in Germany.”

Bitter shook hands with the others and took off, leaving the four of us on the church steps.

“What’d he say?” I asked Sondra.

Sondra shook her head quizzically. Her long, frizzed hair flew out to the sides. “The bottom line is that he wants to have lunch with his family. But tell me more about Harry’s blunzer.”

October 6, 2012

SF Religion 1: The Central Teachings of Mysticism

Any SF writer wonders from time to time if he or she might be able to found a successful religion. I’ve had some thoughts along these lines recently.

But never fear, I’m thinking in terms of a novel I’m writing, and not in terms of “dominating the world.”

This week I’m going to put up two, or maybe three, posts on the SF-related religion theme. Today I’ll get started with a piece I wrote thirty years ago, not without interest in its own right, and in the following posts, I’ll talk about how this fits into my current grand scheme.

The Central Teachings of Mysticism

Introductory Note

I wrote “The Central Teachings of Mysticism” in 1982 and gave it as a talk. It appeared in my collection Transreal!, WCS Books, 1991, and is in my Collected Essays, Transreal Books, 2012.

When I wrote this talk in 1982, my wife and I were living in Lynchburg, Virginia, and a poet friend of ours named Mary Molyneux Abrams had been taking classes at Sweetbriar College so she could get her Bachelor’s degree. She and her husband David Abrams were friends of ours there. David is a photographer. I used Mary as a model for Sondra Tupperware in Master of Space and Time, and David took the photo of me which appeared on the dustjacket of the hardback edition of The Secret of Life.

In the fall of 1982, Mary decided to stop going to school, and her husband said, “Why not give Mary a graduation party anyway?” He made up engraved invitations mentioning me as the commencement speaker. At the party, I handed out mimeographed copies of “The Central Teachings of Mysticism” and read it to the audience of some forty people.

My father Embry Rucker, Sr., who was an Episcopal priest, happened to be there and he gave a blessing. And at the end of the ceremony we sang “Take Me Out To The Ballgame.”

The Talk

This is not going to be very funny, but I hope it’s at least interesting. One reason I like to talk about mysticism is that talking weird gets me high: the air gets like thick yellow jelly, you know, and everyone’s part of the jelly-vibe jelly-space jelly-time…

All is One. That’s the main teaching, that’s the so-called secret of life. It’s no secret, though. It’s a truism that we’ve all heard dozens of times. The secret teachings are shouted in the streets. All is One, what can I do with that? How can I use it in the home? If that’s the answer, what’s the question?

I guess the most basic problem we all have to deal with is death. In Zen monasteries, the entering students are given koans to solve. A koan is a type of problem unsolvable to the rational mind: What was your face before you were born? This is not a stick. [Holds up a stick.] What shall I call it? Each of us on Earth has a special koan to work on, it’s the death-koan, handed out at birth: “Hi, this is the world, you’re alive now and it’s nice. After awhile you die and it all stops. What are you going to do about it?”

The mystic escapes death by denying that he or she exists as an individual bag of meat. “I am God,” is the easiest way to put it, though this doesn’t always go over too well. “Hi, I’m God, this is my wife, she’s God, too. These are the children, God, God, and…” What I have in mind here is that God—or the One, if you want to be more neutral-sounding—what I mean is that God is everywhere and we are all part of God. We are like eyes that God grows to look at each other with.

The word “God” does grate. Organized religion puts a lot of people uptight (we will be passing out the plates soon) and when a lot of us hear that word (get your hands outta there, friend) our first impulse is to find a brick and throw it, or just leave or go to sleep (you’re gonna burn for this)…

Here’s where the second central teaching comes in. All is One, fine. But: The One is Unknowable. “God”—that’s just a noise I’m making up here, a kind of pig-squeal. We don’t know God’s name, and we never will. The ultimate thing, the fundamental Reality—it’s not something the rational mind can tie up in a net of words. I can’t really tell you what I’m thinking about. In a way it’s pointless to talk about mysticism at all. “If you see God, only piss to mark the spot”—that’s a line from a poem I wrote when I was thirty. I was down in the islands, standing on a beach at night. If you see the Buddha in the road, kill him.

So here’s two teachings: All is One, and The One is Unknowable. The third (and last) teaching is The One is Right Here. You’re totally enlightened right now, right as you are. You see God all the time; you can’t stop seeing Him. We’re all in heaven and there is no hell.

First I claim that all of reality is one single thing, a sort of giant orgasm or something. Then I say that this One is unknowable, but right away I turn around and say that the One is perfectly easy to see, it’s everywhere. Do we have a contradiction? How can the mystics say that, on the one hand, God is unknowable, and that, on the other hand, God is everywhere?

People who have a traditional view of religion are perfectly comfortable with the idea of God as something way up there, something unattainable: the Commander in Chief, the Head Technician, our Fearless Leader, the Great Scientist who put all this together. The Church of Christ, Cosmic Programmer. What’s God thinking about? Smart stuff, hard stuff, stuff we can never understand. That’s the God is Unknowable teaching. No rational human description can exhaust the riches of the One.

The other side of the coin is that we know the One perfectly well. You can’t describe God in any complete way, but God’s as much a part of you as your body is. You can know something in an immediate way without knowing it in any kind of analytic way. You don’t need to be a geneticist to know how to make babies.

So when mysticism says The One is Unknowable and then says The One is Right Here, there isn’t really a contradiction. It’s just that there’s two kinds of knowing. We can’t know the One rationally, but we can know it in an immediate and mystical way. Anyone can go into the temple, but you have to leave your shoes outside. “Temple” stands for a mystical vision of God, and “shoes” stands for conventional ways of talking. You take off your shoes and walk into the temple.

We don’t have to go to the Far East to find mystical religion. Christianity is based on the idea that, on the one hand, God is way up there in seventh heaven, and that, on the other hand, Jesus comes down to live in our hearts. It’s a strange thing that many of us are more comfortable with Buddhism than we are with Christianity. It’s strange, but the reasons are pretty obvious—I mean, imagine if there were a 24-hour-a-day Buddhist Broadcasting TV network:

“Friends, I want to talk to you about samadhi. This blessed state of union with the Void—Void being Nothingness, friends—this blessed state was first experienced in a little town near the Ganges River. God brought a man—a man, friends, and not a woman—God in His wisdom brought forth this human—a human, friends, and not a Communist—God brought to this seeker a vision of the Void. How best might you, in your ignorance, in your sin, in your present debased circumstances, how might you best seek the Void? The Void can be found in your wallet, dear seeker, if only you will send its contents to me…”

So you go turn on the radio, man, and instead of music there’s some grainy-voiced guy yelling:

“…hatred. Yes, hatred, my fellow enlightened ones, Buddha came to preach hatred. I know this may sound strange to some of you out there in the radio audience, but it’s not a matter of conjecture. God hates the unbeliever, just as the unbeliever hates me…”

There is so much negative stuff associated with religion, that many of us would just as soon never talk about God at all. But there’s still that death-koan hanging overhead: life is beautiful, life ends, what can I do? If I decide not to think about bad stuff like death and loneliness, then I end up spending all my energy on not thinking. I can buy lots of stuff, but every visit to the repair shop is an intimation of mortality. I can get real high, but I always have to come down. And not choosing anything at all is itself a choice.

Mysticism offers a way out. It’s really just a simple change of perspective. A person’s life is like a design in an endless spacetime tapestry. Molecules weave in and out of your body all the time. Inhale/Exhale; Eat & Excrete. You breathe an atom out, I breathe it in. I say this, you answer that. Atoms, thoughts and energies play back and forth among us. We are linked spacetime patterns, overlapping waves in an endless sea. No one exists in isolation, everyone is part of the Whole. If a person can only take the word, “I,” to be the Whole, then that “I” is indeed immortal. In the book of Exodus, Moses asks God what His real name is. God answers: “I AM.” All is One, All is One.

If this were just an abstract idea, then mysticism would not be very important. What makes mysticism important is that you can directly experience the fact that All is One.

I used to read about mysticism and wonder how to score for some enlightenment. There’s something so slippery about the central teachings—the way the One is supposed to be unspeakable, yet everywhere all the time—it used to really tantalize me. And then finally I started getting glimpses of it, sometimes with chemicals, sometimes for no reason at all. I’d see God, or feel the world synch into full unity, and I’d love it, but whenever I tried to grab onto it, the life would somehow drain out, and I’d just have some dry abstract principle.

After I got so I could occasionally feel that All is One, I started being uptight that I couldn’t be there all the time. I bought lots of books by totally enlightened men. Eventually I concluded that no one does stay up there all the time. You can’t always be having a shining vision that All is One; you have to do other stuff, like deal with your boss, or fix the car, meaningless social hang-ups, the stuff like walking and eating and breathing. You can’t always be staring at the White Light.

But you can. That’s the next level, you see. The Light is everywhere, all the time. Being unenlightened is itself a kind of enlightenment. There are no teachings, and there’s nothing to learn.

Congratulations, Mary.

Addendum

(Recall that the “Mary” I mention at the end was the woman for whom this “graduation talk” was for—as mentioned in the introductory note.)

Rereading my little lecture twenty or thirty years later, I enjoy its flow, but I feel like it’s missing something. God (or the One) isn’t just some kind of logic puzzle, the Absolute can directly touch your heart. Over the years I’ve added a fourth and a fifth “teaching.” These are: (4) God (or the Cosmic Light) is Love, and (5) The One will help you if you ask. Help you do what? To be less selfish, more loving, less driven, and more serene—to let go and stop trying to run everything. Seek and ye shall find.

October 1, 2012

CC “Turing & Burroughs.” “Rapture of Nerds.” Telepathy.

This week I read a free Creative Commons licensed version of a novel on my Kindle. And that set me to thinking that I should do a CC release of Turing & Burroughs. In the past, I’ve done this for some of my other books—Postsingular and The Ware Tetralogy. My experience is that, in today’s odd post-crash potlatch iterary economy, doing a CC doesn’t seem to hurt my sales.

So I posted some free CC versions of the new book, see the link on the Turing & Burroughs page. Dig in and snarf ‘em up, but don’t let that stop you from buying the book! Keep in mind that Transreal Books does have a nice paperback edition of the novel as well as commercial Kindle, NOOK, EPUB and MOBI editions. At present the paperbacks are only on Amazon, but in a month or so they should be on the other book sites and even in some physical bookstores. In time for Xmas.

By the way, Turing & Burroughs got a great review by Autodesk founder and computer maniac John Walker.

Anyway, the catalyzing book that I was reading in a CC edition this week was Cory Doctorow and Charles Stross’s long-awaited Rapture of the Nerds . It’s great fun, very clever and postsingular. The cloud of simulated minds living in outer-space dust is a real place now, an accepted SF trope. The novel resets the bar of what one expects from an SF novel—indeed, for an SF writer, it’s a bit daunting to read. And, rather than being a straight-on geek-fest, the book gains transreal richness by getting into the main character’s issues with his/her parents. (Gender is mutable in the postsinglar world.)

The style of Rapture of the Nerds is at times very beautiful. Just at random, here’s a sentence from Rapture of the Nerds that I really loved—I’ve always been fond of odd lists crafted in the manner of Jorge-Luis Borges.

Out the window, where there should be iron gray Welsh sky and the crashing sea, there is, instead, a horizon-spanning skybox hung with ornament-sized pieces of reality, hung in serried ranks: trees, houses, buildings, people, livestock, CO2, rare earths, bad ideas, literary criticism, children’s books, food additives, tumbleweeds, blips, microorganisms, lamentable fashion, copy editors’ marks, pulsars, flint axes, cave drawings, mind-numbingly complex mathematical proofs, van art, mountains, molehills, uplifted ant colonies.

Yeah, baby!

I’m so glad to have Stross and Doctorow around. They keep the game interesting.

Moving on, I also want to discuss some ideas about telepathy and the possible shock thereof.

Some of the characters in Turing & Burroughs have telepathy with each other, and they don’t find it that disturbing. And in Rapture of Nurbs, the characters handle greatly expanded states of consciousness fairly easily as well. But I’m thinking that, in my next novel, The Big Aha, I think telepathy will be treated as something that’s more disorienting, at least initially, than we SF writers usually admit.

My ideas along these lines relate to something I was pondering this past weekend at the Phil Dick Fest. I have a long-standing peeve about consensus history—our rulers’ “history” is all about politicians, fat cats, nobles, and wars. But the consensus history you learn in school is only one path through the superspace of human thought, one threaded traversal of the mindscape.

In reality, each of us has our unique version of history. And so does a grain of sand or a bird or a table leg (getting into my Hylozoic trip of every object in the world having a mind). And if you were sufficiently telepathic, thanks to, let’s say, quantum wetware, you’d get an awareness of all the life stories and the whole block of the mindscape.

And this effect would be a big aha—or at least he start of one.

How will the big aha feel? You might, at least initially, be incapacitated, or you might find some way to deal. I’m thinking about this in terms of writing an SF novel. And I do know that the merging with all minds thing has been done. So I’d like to find a fresh angle. I’ll list some of the possible effects of the telepathy-big-aha on the visionary, all of which have been used, but some of which seem more amenable to being used again.

Odd-ball twist: the visionary becomes a chimera with body parts from other beings. Would be good to mix some of this in, it’s good to have a funky, meaty objective correlative for the fanciful abstract mind state. Maybe my character oey Moon undergoes this when he has a fit of telepathy fueled higher consciousness. Would be a tasty scene.

A “roving I” montage where you flip through different points of view. Recently I read this as the “Transplant” sequence in Robert Sheckley’s Immortality Incorporated, and I think I did something like this in Frek and the Elixir. But I’m not sure this can be made interesting again. It’s dull and stale if you just start cataloging a sequence of random bizarre points of view. At the very least you’d want a metastory thread connecting the points of view.

A mystical white light blank-out—this is coma thing.

Slightly less incapacitating: an omniscient mind-lift to a god-like and synoptic Hilbert Space viewpoint. I did some of this with my “Big Pig” scenes in Hylozoic.

A hive mind synergy where you’re working with the minds around you. People hate the idea of hive minds, of course. Un-American! (Of course any society really is a hive mind.)

But instead of a hive mind we talk about a network of hubs where each of us is reaching out and assimilating the other viewpoints while still holding our own.

I like the network image best for a telepathy-big-aha story. I was getting into this frame of mind sitting in a field up on a hill near my house at dusk the other day. Imagining I was “in” the trees around me, in the rocks, in the deer wandering around (a small herd lives up there). Although I was reaching out into the other mind flows. I was still an integrative center. As if the other minds were webpages I was browsing on multiple screen, while I’m still being me in my Aeron office chair as it were.

Keep in mind that any scene involving exalted telepathic states can quickly founder on the reader’s impatient question: “So what?” The whole interest of a character is that they embody a specific point of view. It’s important to keep the individuality even if my character is teeping a lot of stuff around him.

I’m also thinking that, after the telepathy-big-aha, I’ll have to move on to a stronger marvel. Giant ants? Branching time? Transdimensional aliens? A cloud of nants? Another run at hylozoism, where every natural object gets a mind? Or something unheard of.

I’ll keep pushing on it, and see where the Muse takes me.

Meanwhile, check out Turing & Burroughs!

September 24, 2012

Haunted by Phil Dick

Today’s post is an edited version of talk that I gave at the Philip K. Dick Festival in San Francisco, on September 22, 2012. It was a good time at the fest. I saw my old friends Charles Platt and Michael Travers, got to hang out a little with the exultant SF-ghetto-escapee Jonathan Lethem, and made some new friends, including Ted Hand, Gregg Rickman, David Gill, John Simon, Kitty Gainer, Autumn, Brad Scheiber, and Erik Davis.

I’ll also be posting an audio file of the talk the next week or two.

[My ancestor, Howell Cobb, one-time governor of Georgia. Shown here apropos of, uh, living in the South.]

In the spring of 1982, I’d just learned I was losing my day-job as a professor in lowly Lynchburg, Virginia, and I was singing in an amateur punk band called the Dead Pigs.

Phil Dick died around then, and I started thinking about him a lot. Every day, starting out, I’d pray to Phil Dick and ask him for guidance—to some extent I was trying to run a mental emulation of him.

I heard I’d been nominated for the first Philip K. Dick award (for my novel Software) and I felt I had a good chance of getting it. I begged Phil, or my internal simulation of him, to make sure I would get it. I’d done five SF paperbacks at this point, and was getting zero recognition. I really needed a break.

That winter—in January ‘83—my wife and I went out to a party at a house in the country. We didn’t know too many of the people—they were sort of rednecks, where those days in the South a redneck was person with long hair and a scraggly beard. It was mellow, plenty of weed, loud music, and everyone getting off.

[Actually this is Paul Di Filippo. Who can you believe?]

At some point I glanced across the room and in walked Phil Dick. He didn’t say he was Phil Dick, but he looked to be wearing his circa-1974 body…hair still dark, beard…hell, I don’t know what Phil Dick “really” looks/looked like, but I knew this was the guy.

At first I just grinned over at him slyly—like Aphid-Jerry eyeing “carrier people” in A Scanner Darkly. Then, finally, I introduced myself and drank beer and whisky in the kitchen with him for awhile. Of course I was too hip to confront him with my knowledge of his true identity.

The man’s cover was that he was in the garbage business. “The Garbage King of Campbell County.” He said he had a fleet of trucks, and that he’d furnished his entire house with cast-off items gleaned from the trash-flow.

I steered the conversation around to science fiction, mentioning my novel Software.

“What’s it about?”

“It’s about robots on the moon. In a way they’re black people. The guy who invented them—he’s my father—is dying and the robots build him a fake robot body and get his software out of his brain.”

“Go on.”

“They run the software on a computer, but the computer is big and has to be kept at four degrees Kelvin. It follow him around in a Mr. Frostee truck. There’s a big brain-eating scene, too.”

“Sounds all right!”

In March of 1983, I got the Philip K. Dick award for Software. My wife and I flew up to New York City for the awards ceremony. Earlier that evening we had dinner with some SF people. Our whole party walked over to Times Square, where we saw Bladerunner. Phil’s friend Ray Faraday Nelson said, “Phil would have loved this movie.”

The award ceremony was in an artist’s loft, with the hallways covered in reflective silver paint. One of the first people I ran into was my artist friend Barry Feldman from college. Incredibly, he was wearing a suit, and he looked like Chico Marx. Although Barry was a great painter, he wasn’t breaking into the gallery scene. On a sudden whim, I told Barry he could pose as me and enjoy the fame.

As I was such an outsider to the SF scene, nobody knew what I looked like, and the substitution worked for about half an hour. Barry stood by the door shaking hands and signing books, twinkling with delight. I stood across the room, drinking and hanging out. And eventually I met some people too.

Later that evening I stood on the bar at one end of the silvery room and delivered a short speech that I’d composed on the plane up from Lynchburg.

“I’d like to just say a few words about immortality. I have a theory about how artistic immortality works. When you’re reading a well-written book, and totally into it, then you are, for those few moments, actually identical with the person who wrote the book. It’s my feeling that artistic immortality means that the artist is, however briefly, reborn over and over again. We could express this idea in terms of computers. If you can somehow write down most of your program, then some other person can put this program onto his or her brain and become a simulation of you.

If I say that Phil Dick is not really dead, then this is what I mean: He was such a powerful writer that his works exercise a sort of hypnotic force. Many of us have been Phil Dick for brief flashes, and these flashes will continue as long as there are readers.

Up till now I’ve talked about immortality in very abstract terms. Yet the essence of good SF is the transmutation of abstract ideas into funky fact. If it is at all possible for a spirit to return from the dead, I would imagine that Phil would be the one to do it. Let’s keep our eyes open tonight, he may show up.

So hi, Phil, wherever you are, and thanks for everything.”

I switched from teaching to being a freelance writer fulltime, not that my advances were especially good. Over the next couple of years in Lynchburg, I saw the Garbage King of Campbell County a couple more times at parties. One time we were in a house, a house like a house I often dream about, with a front and a back staircase, and the King and I were on a landing, him and his good-looking wife, and he says, “What was that writer guy you talked about? Philip Jay Dick?” Only then he gave me a sly wink. I was stoned enough at the time to think that the “Jay” was a psychic reference to the fact that the first Dick book I ever owned was Time Out of Joint.

I wrote Wetware in the spring of 1985, just before moving to California. Once I got rolling, I wrote Wetware at white heat. I think I finished the first draft during a six-week period from February to March of 1986. I made a special effort to give the boppers’ speech the bizarre Beat rhythms of Kerouac’s writing—indeed, I’d sometimes look into Jack’s great Visions of Cody for inspiration. Wetware was a gift from the muse—insane, mind-boggling, and, in my opinion, a cyberpunk masterpiece.

And later in 1986 we moved to San Jose, California—I’d gotten a job teaching computer science at San Jose Statue University. And in San Jose and I saw Phil again.

The way I found Phil in San Jose involves my friend Dennis Poague. My Wares novel character Sta-Hi, also known as Stahn, also known as Stanley Hilary Mooney, was transreally inspired by a Dennis, occupation freelance mechanic, legal status Blank (like the “Blank Reg” character in Max Headroom), long-term resident of San Jose.

I’d first met Dennis in the mid-seventies when I was teaching college in up-state New York, a state college in a small town called Geneseo, described as “Bernco” in White Light. Dennis’s brother Lee was an English professor who lived across the street from us. Dennis orbited through our town about twice a year. One time he had a whole suitcase full of cheap green pot. It was so bad that he cooked a pound of it into tea. He took the rest of it to the Mardi Gras and got robbed.

Dennis and I got along very well together, each of us happy to meet such a madman. He seemed to have no internal filter—whatever he thought, he said. And it crossed my mind that he could be a god-in-the-gutter sidekick to inspire me in the way that Neal Cassady inspired Jack Kerouac.

When I got to San Jose in the summer of 1986, I hadn’t seen Dennis in a few years, and I was a little nervous about it. He phoned up, and asked me to stop by his apartment in downtown San Jose.

Where he lived wasn’t actually a real apartment, it was simply a small room at the head of a flight of stairs in someone’s house. Wherever Dennis lives there are always four or five half-assembled cars in the driveway and backyard. He was fixing one or several of these cars in return for being allowed to live there. His room was not much larger than a bed; there were shelves on the wall piled with electronic music equipment, cartons of old Heavy Metal magazines, car parts, ragged clothes and hundreds of T-shirts.

“You got no idea how glad I am to see you, Rudy.”

I gave him a Xerox of the typescript of Wetware, and then Dennis took me downstairs to meet his speed connection, a muscular, shirtless fifty-year-old Filipino called Buffalo Bill. I watched them crush up some crystal, snort it, and begin to jabber about skin-diving for jade boulders as big as cars.

[Toaster handmade from ore and oil, by Thomas Thwaites, seen at SJ Zero1 Biennale.]

I sat around and enjoyed the scene. When it was time to go, I opened the wrong door, a door which led down into the basement. Standing there on the basement stairs was a punk in painter’s clothes and just below him, staring up at me like out of a cover of the PKDS news-letter, was the real Phil Dick, not too tall, balding with a beard with a white stripe in it, and with the unmistakable aura of a hologram from Hell. He and the punk painter were snorting lines of meth off a pocket mirror.

I freaked and closed the door right back up. “Who was that?” I asked Dennis as soon as we got outside. “On the stairs, who were the two guys on the basement stairs?”

“Hell that’s just Tommy the painter. His father owns the place. The other guy with him rents the back room by the garage. He doesn’t talk much. Just…” Dennis made loud piglike snorting noises, the same noise he’d made earlier when I’d asked him what he would do if he really did make a lot of money off jade.

“The other guy, Dennis, that’s Phil Dick. You know, the Philip K. Dick award I got for Software? That was him in the basement. He must not really be dead! He’s living right here in your building!”

“Why didn’t you talk to him?”

“What would I say? But, look, Dennis, do one thing for me. After you read Wetware, give it to him. It’s dedicated to him, wave? ‘For Philip K. Dick, 1928–1982, One must imagine Sisyphus happy.’ That’s from Camus, see, Sisyphus being the proletarian of the gods, you understand, daily proving that scorn can overcome any fate, rolling another wad of paper up to the top of the same old mountain and letting it blow away, just imagine him happy. Does he seem happy?”

“I’ll ask him.”

But Dennis never did talk to Phil. Phil got on his motorcycle and left that house for good, right after I did. I saw him in my rearview mirror, right before I turned onto Route 17. He was all in black, idling on the putt, wearing shades, a greasy old biker, calm with meth. Looked to me like he was headed for South San Jose. He never waved.

A couple of years later, in 1989, Wetware would win me a second Philip K. Dick award.

This award ceremony was at a smallish regional SF con in Tacoma, Washington. It wasn’t like the artists’ loft in New York at all. It was in a windowless hotel ballroom with a dinner of rubber ham and mashed potatoes.

I still wasn’t making much money from my writing, and I’d started working two day jobs, teaching computer science and programming in Silicon Valley. I didn’t have time to write as much as before, which was putting me into a depressed state of mind. Winning the award, I felt like some ruined Fitzgerald character lolling on a luxury liner in the rain—his inheritance has finally come through, but it’s too late. He’s no longer a free man.

In my acceptance speech, I talked about why I’d dedicated Wetware to Phil Dick, and why, in particular, I’d added a quote from Albert Camus about Sisyphus.

“I see Sisyphus as the god of writers or, for that matter, artists in general. You labor for months and years, rolling your thoughts and emotions into a great ball, inching it up to the mountain top. You let it go and—wheee! It’s gone. Nobody notices. And then Sisyphus walks down the mountain to start again. Here’s how Camus puts it in his essay, The Myth of Sisyphus: ‘Sisyphus, proletarian of the gods, powerless and rebellious, knows the whole extent of his wretched condition: it is what he thinks of during his descent. The lucidity that as to constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory. There is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.’”

As so often happens to me, nobody knew what the f*ck I was talking about. Outside the weather was pearly gray, with uniformed high-school marching bands practicing for something in the empty streets.

[Charles Platt in a hat made from a newspaper he found lying on the ground this weekend. I was dragging Charles to Ocean Beach, and he didn't want to buy a nifty $24 billed cap from the surf shop. On the beach, the hat fell apart, and he was reduced to holding a piece of paper over his head. I was telling him that "Platt's Hat" might become a standard example in philosophical discourse, along the lines of Occam's Razor or Buridian's Ass or the Thompson Lamp.]

Did I ever see Phil Dick again? Sure. This weekend I was at an academic P. K. Dick festival in San Francisco, and Phil spare-changed me in the parking lot. I gave him a dollar, and he said he was going to get me a movie deal. From Phil’s mouth to God’s ear!

September 21, 2012

Interview On My TURING & BURROUGHS Novel.

On Saturday, September 22, 2012, I’ll be at the Philip K. Dick Festival on the SFSU campus in south San Francisco. I’m scheduled to give a talk, “Haunted By Phil Dick” at 2 p.m. that day, and I’ll be on a panel with Jonathan Lethem and other Dickians at 5 p.m. as well.

For today’s longish post, we have the text of an email interview about my novel Turing & Burroughs that the young writer Nas Hedron conducted with me from Brazil.

Hedron is the author of the novel Luck & Death which, like my own novel, involves Alan Turing. You can learn more about Hedron via the links on his blog The Turing Centenary, where his interview with me also appears.

[image error]

$16 paperback, $6 in ebook.

Q 1. I wonder if you can set the stage for us with reference to Alan Turing, you, and writing. Who was Alan Turing to you before you wrote Turing & Burroughs: A Beatnik SF Novel? And what gave you the impulse to write your novel about him?

A 1. In the course of getting my Ph.D. in mathematical logic, I learned the technical details of Turing’s theorems about the idealized computers that came to be called Turing machines. I read his epochal 1937 paper “On Computable Numbers” numerous times, and I was struck by the clarity and the depth of his thought.

Being interested in the possibilities of intelligent machines, I also studied Turing’s 1950 paper, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” a non-technical paper in which he proposes the so-called Turing imitation game as a test for true AI: you might say that a program is intelligent if you can’t tell it from a human when you’re exchanging emails with it. It’s worth noting that Turing initially framed his “imitation game” in terms of someone trying to distinguish between a woman and a man.

Later I became interested in using so-called cellular automata programs to simulate the patterns that emerge in the tissues of plants and animals—patterns like the the spots on leopards, the markings on butterfly wings, the zigzags on South Pacific cone shells. This is what Turing was working on near the end of his life. In 1952 he published an amazing paper, “The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis.” In the morphogenesis paper he explains how, by dint of days of hand computation, he emulated a biological cellular automaton process to produce irregular black spots like you might see on the side of a brindle cow.

To me Turing is a heroic and inspiring figure. He worked on deeply fascinating things without getting lost in merely technical mathematics.

The other compelling aspect of the Turing story is that he was openly gay, he was persecuted for it, and that he had a strange and tragic death—which is usually described as a suicide.

Regarding Turing’s death by cyanide poisoning, I’ve always felt there’s a real possibility that he was in fact assassinated by agents of the British government. This seems even likelier now that we know Turing was involved in a top-secret code-breaking effort during World War II. In the 1950s, there was a collective hysteria over the possibility of homosexuals being a security risk.

Before I began contemplating my own novel, I’d read some stories and plays about Turing. But I didn’t feel that any of these works captured the vibrant image of Turing that I wanted to project. There can be a tendency to write about homosexuality in a lugubrious tone—as if a homosexual is a pathetic person who’s afflicted with a lethal disease. But Turing was anything but downcast about his predilections.

A 1 (Continued).

In the spring of 2007, I wrote a short story about Turing, “The Imitation Game.” And this story later came to be the first chapter of my novel. In the short story, Turing escapes being poisoned by British government agents. And to escape, he swaps appearances with his dead male lover. And here comes the science fiction: Turing grows two new faces by using principles that he described in that paper where he generates the shape of a spot on a black-and-white cow.

As sometimes happens to me, I had difficulty in selling my story. Maybe it wasn’t sufficiently solemn and lugubrious—and I was presenting Turing was a gay outsider, heedless of proprieties, and by no means a victim. In any case, in 2008 my story appeared in the British magazine Interzone and in 2010 in The Mammoth Book of Alternate Histories, edited by Ian Watson and Ian Whates.

Early on, I began wondering if there might be some way to expand my Turing story into a novel. At the end of my story, Turing escapes to Tangier, and I formed the notion that he ought to connect with the Beat writer William Burroughs, who was living there at that time. Two brilliant men, gay, outcast—perhaps they’d hit it off.

I’ve been a huge Burroughs fan ever since I first came across an excerpt of Naked Lunch in the beatnik magazine, The Evergreen Review—this would have been back in 1960, when I was fourteen. My big brother had a subscription to the magazine, and I’d leaf through it, looking for smut. Instead I found a literary career.

I particularly admire the irresponsible and laceratingly funny style of the letters Burroughs wrote to his friends from Tangier. And so I decided to write my second Turing story in the form of letters from Burroughs to Kerouac and Ginsberg.

This second story, “Tangier Routines,” was so gleefully scabrous that I didn’t bother sending it to any magazines, science-fictional or otherwise. Instead, in the fall of 2008, I printed it in a webzine Flurb that I’d managed to start. And then in 2010 and 2011, I ran two further Turing & Burroughs stories in Flurb—“The Skug” and “Dispatches From Interzone.”

I was still unsure about how to build my tales into a full novel, but in 2010 I finally read Alan Turing: The Enigma, the wonderful biography by Andrew Hodges, And here I learned that Turing was everything I could have hoped. Stubborn, unrepentant, impulsive, and with a very warm and human personality.

I discovered that, as part of some psychological therapy he was undergoing, Turing himself made a start at writing a transreal speculative novel late in his life—and this allayed any uneasiness I’d felt about dragging his name into the gutter of science-fiction.

So why did I write a beatnik SF novel about Alan Turing? In short, I’d come to think of him as my friend, and I wanted to give his character a cool place to live.

Q 2. What interested you about bringing the mathematician Alan Turing together with the Beat writer William Burroughs?

A 2. To some extent this was a matter of convenience. I needed Turing to flee England in 1954 to escape assassination by the secret service. Even though Turing has changed his face in my novel, it seemed like he’d feel safer taking trains and ferries than in trying to get on a plane.

From my familiarity with Burroughs, I knew that Tangier was an open city at this time, a good place to take refuge—Burroughs often referred to it as Interzone. And, checking my references, I realized that he was indeed living in Tangier at this time.

Having my two heroes meet seemed perfect. Having them connect also solved a problem I was having in figuring out how to write a gay male character in an effective way.

William Burroughs is a queer writer whom I’ve always found easy to identify with. He has an outspoken zest and a defiant rudeness that make it seem cool and reasonable and entirely desirable to be a homosexual heroin addict.

Even though I myself am merely a punk SF writer, I sometimes feel a certain social opprobrium regarding my esoteric interests, and, over the years, I’ve occasionally girded myself by adopting Burroughsian attitudes and mannerisms. Wearing the old master’s character armor.

One of the challenges in writing a William Burroughs character was that I had to deal with the fact that, a couple of years before the start of my novel, Burroughs had shot and killed his wife Joan in Mexico City. At first I felt like this was too explosive and difficult to write about directly. But then I realized that I had to face the killing.

So my Turing and Burroughs end up going to to Mexico City, resurrecting Joan, and letting her run a number on Burroughs. I wanted to give Joan a voice, and to give her a chance to get even.

I wrote the Mexico City chapter from the Burroughs point of view, writing very fast. It was like I was possessed—but in a good way. The experience was heavy and ecstatic. For months I’d been anxious about writing the chapter, and all at once it was done

I’m always happy when I’m being Bill Burroughs. He didn’t give a f*ck what people think. And neither did Alan Turing.

Q 3. Its impossible to read Turing & Burroughs without comparing and contrasting Turing’s real life with his life in your novel. Two of the simplest ways in which one might develop a story about an outsider’s relationship with the world are victory and defeat. In a victory story, the outsider transforms the world into something more congenial; in a defeat story, the world crushes the outsider.

In Turing’s real life, defeat was the way things played out. But throughout much of The Turing Chronicles, it looks as though Turing is headed for victory or at least for a rapprochement. He and his allies are turning everyone into shapeshifting mutants like themselves—what you call “skuggers.” But then, at the end of your novel, you return to something closer to Turing’s real life, something like defeat. Your Turing character saves the world, and he dies. Did you plan this in advance?

A 3. That’s a very interesting question, and I hadn’t thought about this so clearly before.

I’ve always been piqued and annoyed by the defeat aspect of Turing’s actual life. Either he was goaded into suicide or he was murdered outright. So, as I mentioned before, In writing Turing & Burroughs: A Beatnik SF Novel, I wanted to create a world in which Turing escapes his tragic fate and lives on to have wonderful adventures.

But I knew from the start of my novel that, even though my Turing character has escaped England, he’s a marked man. The pigs, the bullies, the scumbag straight-arrows—they’re unrelenting in their efforts to bring down our Alan. So my novel takes on the quality of a long chase.

It would have been possible, at least in principle, to write a novel in which Turing manages to convert everyone in the world into a shapeshifting skugger like himself. But fairly early on, we begin to understand that this wouldn’t be a pleasant endpoint to reach. We want to be ordinary humans, not skuggers.

So I needed for Turing to somehow undo the mutations—but without killing off all the people who’d become skuggers. And this wasn’t going to be easy, with the cops and feds breathing down his neck. So before long, Turing was heading towards a world-redeeming self-sacrifice. But this felt like the most dramatic way to go. Turing as Savior. It’s a big, strong ending.

I think one can argue that Turing doesn’t truly suffer defeat here. He transcends. As the Beat writer Jack Kerouac would put it, Alan ends up safe in heaven dead. And in the context of my novel’s world, heaven is a real place.

Q 4. In Turing & Burroughs, Turing experiments with what one might call computational human flesh. This bears a certain family resemblance to “flickercladding,” the soft robot flesh you imagined in the Ware Tetralogy, in which each grain of the cladding acts as a processing unit. This particular feature of your work puts me in mind of the effects that director David Cronenberg uses in his movie version of Naked Lunch—I’m thinking of his Burroughs character’s soft, genitalia-like typewriters. Are you conscious of a reason why you like conflating computation and flesh?

A 4. I’ve always been bored by the idea of rigid, clunky, machine-like robots. I wanted robots to be funky and wiggly and sexy. I think it’s likely that if we ever have really useful and intelligent robots, they’re going to be more like tentacled octopi than like brittle ants. Of course thirty years ago, when I started writing about flickercladding and piezoplastic “moldie” robots in my Ware novels, this wasn’t at all a familiar idea.

Having gotten used to the idea of soft machines, it became natural for me to turn things around—and to have the cellular structure of human flesh become as malleable as the material of a computer display.

In my Ware novels there’s a drug called “merge” that lets people melt together inside a tub called a love puddle. And in Turing & Burroughs, a person who’s a skugger can turn into something like giant slug. There’s a scene where Turing and another skugger have sex by twisting themselves around each other while hanging from a rafter at Burroughs’s parents’ house. Mrs. Burroughs throws them out.

Reading a draft of Turing & Burroughs, my wife said, “Oh, you’re always doing this, having people merge together, it’s so icky.” And I’m like, “Yeah, but that’s sex, isn’t it? That’s how it is.”

We’re biological organisms—we’re not computers, and we’re not machines.

A 5. In your free downloadable book-length Notes for the Turing & Burroughs novel, you mentioned the possibility of having J. Edgar Hoover be a character. I’m a little disappointed that he didn’t make it into the book. I had a hankering to see Turing and Hoover go head to head. What kinds of considerations are important in making decisions about what to leave out and what to put in?

A 5. My sense was that I didn’t want to put too many famous people into my book. If you overdo that, then you’re name-checking, and it gets to be like a bus tour of the homes of the stars. And the stars dazzle away the reality of the characters whose lives you want to delve into.

If I am going to recreate a historical character, I want it to be an interesting person whom I like. And for sure that’s not J. Edgar Hoover! He’s a dead horse. Just because I write something in my notes for my novels, doesn’t mean I’m really serious about using it. Often in my notes I’m just killing time and goofing around. Waiting for the Muse.

Given that I had Burroughs and Turing in my novel, I did feel that I ought to bring in some other Beats and at least one other scientist. I went for Allen Ginsberg, Neal Cassady, and the mathematician Stanislaw Ulam.

Ulam isn’t too well known, but he did a lot of fascinating things. He helped invent the hydrogen bomb, he wrote some of the first interesting computer programs, and he worked with lava-lamp-like continuous cellular automata. His friends thought he was too scattered, too much of a playboy. My kind of guy.

I was happy to have Ginsberg and Cassady show up in a Cadillac. My friend Gregory Gibson read a draft of the novel and he said that scene was like in a circus when you see the wild clowns getting out of a car.

I held back from putting Kerouac into Turing & Burroughs, as Jack would have been too much. He would have taken over. Remember that the main Beat I wanted to write about was William Burroughs.

When I was in the middle of writing the novel, I happened to see some video footage of Burroughs at his house in Lawrence, Kansas, taken a year or two before he died. And I knew right away I could use this scenario for the last chapter of my book. So the last chapter is set as a transcript of Burroughs talking to a video camera.

“And now I’m turning off the machine.”

That’s the book’s last sentence, with Burroughs talking. I like that ending. You might say that it captures the theme of the book.

You can turn off the machines and get wiggly. Even if you’re Alan Turing. Long may he wave.

[Curious? Go to Transreal Books or try browsing free sample version of Turing & Burroughs online as a webpage.]

September 20, 2012

What Is Beatnik SF?

Today’s post relates to my new book, Turing & Burroughs: A Beatnik SF Novel. I presented an expanded version of this material as a talk at the Gloucester Writers Center, on August 28, 2012. My “What Is Beatnik SF” rap breaks into four parts:

1: Transreal SF.

2: William Burroughs as an SF Writer.

3: Transreal SF and Beat Writing.

4: Turing & Burroughs: A Beatnik SF Novel.

1: Transreal SF

From 1960 onward I wanted to emulate the closely observed and confessional writing of the Beats, particularly the work of Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs. But I also wanted to be a science-fiction writer, playing with such classic power chords as aliens, robots, higher dimensions, shape-shifting, and intelligent plants.

In 1967-1968, during my senior year at Swarthmore College, the Gloucester writer Gregory Gibson and I were roommates. We both wanted to be writers, we both admired William Burroughs, and we both liked science fiction. We were, you might say, two piglets in the same litter, nuzzling at the same sow.

After college, Greg and I wrote each other frequent letters about our diverging lives—typed letter on pieces of paper. The letter-writing formed my real apprenticeship as a writer. I learned to write with natural cadences and a casual vocabulary.

In 1968, Greg and I tried writing a novel together, mailing sections back and forth. I saw the projected book as a science-fiction novel called The Snake People—about telepathic, wriggling beings that dart through your mind when you’re high. Greg saw the book as a wry slice-of-life description of a young guy’s experiences in the Navy. The main characters were fictional versions of Greg and me. Parts of the draft made me laugh a lot. But we didn’t push The Snake People to a conclusion. We thought we had more important things to do.

I learned something from our experiment. I found that using myself and my friends as characters in a science-fiction novel appealed to me very much. As Greg remarked a little later on, “The cool thing to do would be to write a science-fiction novel, but write it about your actual life.”

And so the model of the Beats—and later the example of Philip K. Dick—led me to a style of writing that I came to call transrealism in my “Transrealist Manifesto.” In my transreal books I use the surreal oddities of SF to illuminate the human psyche.

I like for the characters of my novels to be based on actual people, or on combinations of actual people. The characters should do more than woodenly move the plot along. They should be sarcastic, miss the point, change the subject, break the set, and do surprising things.

It’s liberating to have quirky, unpredictable characters—instead of the impossibly good and bad paper dolls of mass-culture. Lifelike characters are the “real” part of transreal.

As for the “trans” part—I use the special effects and power chords of SF as a way to thicken and intensify the material. The tools of science fiction can be a way, if you will, to directly manipulate the subtext, that is, a way to add a more artistic shape to the suppressed fears and desires that you inevitably incorporate into your fiction.

Time travel, levitation, alternate worlds, aliens, telepathy—they’re all symbols of archetypal modes of experience. Time travel is memory, levitation is enlightenment, alternate worlds are travel, aliens are other people, and telepathy is the fleeting hope of finally being fully understood.

I saw transrealism as a way to describe not only immediate reality, but also the higher reality in which life is embedded. And I saw transrealism as way to smash the oppressive lie of the news-media’s consensus reality.

One of the simplest ways to write a transreal novel is to model the main character on yourself, and I’ve done this numerous times, as in my novels Spacetime Donuts, White Light, The Sex Sphere, The Secret of Life, Saucer Wisdom, and Mathematicians in Love.

But I often write transreal novels without using myself as a character. Not having a specific Rudy-inspired character can give the other characters more space to develop and to open up. And if they’re not me, they can do more shocking things than I have.

2: William Burroughs as an SF Writer

For whatever reason, most people don’t think of William Burroughs’s novel Naked Lunch as science-fiction, but it is. I feel that it’s transreal SF—that is, an autobiographical SF novel in which the author’s experiences are made more vivid by transmuting them into SFictional tropes.

Burroughs often wrote admiringly about SF in his letters, and he sometimes said that’s what he was indeed writing. But people tend to ignore this. Perhaps it’s that so few SF works aspire to such a high literary level, or that Naked Lunch doesn’t have a straight-through plot-line. But if you look at the tropes in the book, it really is SF—aliens, imaginary drugs, telepathy, talking objects … the gang’s all there.