Rod Dreher's Blog, page 598

March 31, 2016

Religious Liberty Is So Passé

A reader sends in two essays — one from 2014, the other from 2015 — talking about the wide divergence now in public law, particularly around religion. This is really important stuff, re: the future of religious liberty.

In the 2015 piece, Marc DiGirolami, the Catholic law professor, writes about the ideologization of legal scholarship. Excerpts:

For some time now, I have believed that the political and ideological divides among legal academics in the law and religion field have been growing. They have now reached cavernous dimensions. Paul Horwitz argues in this (superb) piece that law and religion scholars have been in a state of general consensus about free exercise/accommodation issues until extremely recently, but I see things a little differently. The disagreements about free exercise have been manifest at least since I have been studying and writing in the area–about a decade now and probably longer than that. But Paul is right that they have increased dramatically even within that period.

Paul is also right that there was a period of such consensus. But it was a much earlier time. It was the period when, for example, giants including Kent Greenawalt and Doug Laycock and Vince Blasi and Jesse Choper came of scholarly age, the period when Leo Pfeffer’s views were dominant in this area, and only a few outliers arguing for non-preferentialism like James O’Neill existed. One could be a liberal nel vecchio stile and with great complaisance in those days, but still support exotic religions (traditional Christian religions were never really on the agenda), confident in the view that the “great minds” of the past—Jefferson and Madison (Marshall, Adams, and so many others were rarely mentioned)—were on board in spirit. One bought one’s bona fides to argue for relatively expansive free exercise protections (it was the ‘60s and ‘70s, and people should be free to follow their stars and make themselves into whatever they wanted) with iron separationism when it came to establishment. But the bottom line was that one’s Establishment Clause views always drove the boat then, as, it seems to me, they do now. Free exercise in that period was an afterthought—a concession to the unusual and the strange. Sort of like the way many discuss the nature of excuses in criminal law. One is excused for one’s conduct because, notwithstanding its wrongfulness, one makes a concession to human weakness by allowing that one is not blameworthy for that conduct. That’s how religion was perceived—as basically somewhere between odd and wrongful, but not culpable, and therefore excusable conduct which should be accommodated where possible for those in need of such ministrations.

That period is dead. It has been dead since long before Paul or I started writing about these matters. For those who followed in the wake of the liberal consensus, what happened was—again, beginning from an ever-hardening view of what the Establishment Clause demanded—the end of the ‘60s and ‘70s with its taste for exoticism and weird pluralism. In its place arrived a new zest for notions of equality, nondiscrimination, leveling, and so on. To argue for “pluralism” full stop and for its own sake today is something of an anachronism (this comes through nicely in the column Paul reacts to today by Frank Bruni). Exactly what is there of worth about pluralism as an intrinsic good? In the interim from then to now, sexual equalities of various sorts have gone mainstream (they were not so when the earlier consensus reigned; at least one liberal law and religion scholar of the ancien regime only began to support gay marriage in the last decade or so). Equalities of other kinds have taken center stage.

The illusion of consensus could be maintained, for a time at least, but only until the new egalitarian mandarins were challenged. Those challenges have come in the abortion context and other substantive due process areas. With some exceptions, the challenges have largely failed. But they had never come from the religion clauses proper (or their statutory analogues). Now they have. And they have made manifest the instability of the former consensus and the fact of its breakdown over many years. To invoke religious freedom is no longer to appeal to a commonly recognized constitutional freedom; it is to whistle to your favorite mangy dog.

This is important. He’s saying that in the not too distant past, most law professors, whether liberal or conservative, shared a view of the importance of religious liberty. Now that has gone. Egalitarianism is what drives the left — and they do not recognize that religious liberty is an important value to defend, even when it contradicts egalitarianism.

DeGirolami draws on an earlier (2014) Harvard Law Review piece by Paul Horwitz, who uses the Hobby Lobby case as an occasion to take stock of the role ideology plays in legal scholarship around religious liberty issues. Excerpts:

Legally, it discusses a key element of the American church-state consensus as it existed until recently: the accommodation of religion. That consensus is aptly summed up by Professor Andrew Koppelman: Religion is “a good thing,” and “[a]ccommodation of religion as such is permissible.” We may debate whether courts or legislatures should be responsible for it, but it is generally agreed “that someone should make such accommodations.” Until recently, there was widespread approval for religious accommodation. That consensus found strong expression in RFRA, which passed just two decades ago with the overwhelming support of Congress. There have been dissenters from this consensus. On the whole, however, it enjoyed “taken for granted” status. In Lessig’s terms, disagreement over religious accommodations was a background issue, not a foreground issue.

The past few years have witnessed a significant weakening of this consensus. Contestation over religious accommodations has moved rapidly from the background to the foreground. Accommodations byanyone — courts or legislatures — have been called into question, including by those who acknowledge that until recently those accommodations would have been uncontroversial. Whether religion is “a good thing” — whether it ought to enjoy any kind of unique status, and whether that status should find meaningful constitutional protection — has itself come up for grabs.

This legal contestation has been accompanied by — indeed, may be driven by — significant social dissensus. Although Hobby Lobby itself involves a controversial social issue — the status of women’s reproductive rights — much of the reason for the shift in views on accommodation involves another contested field in the American culture wars: the status of gay rights and same-sex marriage. The cause of marriage equality, which seems to be a fait accompli awaiting final confirmation from the Court, has come increasingly into conflict with the views of religious objectors to same-sex marriage. Same-sex marriage and its consequences have become a central, foregrounded, socially contested issue. The church-state consensus, drawn into the gravitational pull of this contest, has been put up for grabs as a result. Part III offers some thoughts about the lessons and implications of this debate, both for religious liberty and for the general culture wars that have featured so heavily in the Hobby Lobby controversy.

Remember, this came out a year before the Obergefell decision. The Horwitz comments illustrates what I have been saying for many years, but none of my readers on the left wanted to hear it: same-sex marriage unavoidably affects religious liberty in this country; it’s in the inescapable nature of the thing. Not just lawyers, but the American people held a broad consensus that religious liberty was a good thing. Not anymore. We are living through a critical moment. More Horwitz:

Precisely because these pivotal moments are moments of foregrounded contestation and uncertainty, drawing on the deep divisions that characterize the culture wars on particular issues, the real battle in these moments, within and beyond the law, is over what Lessig calls “utterability.” Moving an issue “on the wall,” so that it forms a legally plausible argument, is only the first part of the game. More important still, if one wants to guarantee or consolidate a victory — particularly one that involves social as well as legal contestation — is to define what can and cannot “be said” over the long run, to define a particular argument as “indecent” and thus unutterable.

This is an old game. It is at least as old as the once-common suggestion that admission to polite legal circles requires one to avow that Brown was wholly correct and Lochner terribly wrong. As with that conventional wisdom, it is always open to recontestation. But the goal — especially when the issue is contested, and much more so when it is both socially and legally contested — is to end the contest, preemptively if possible, by declaring certain arguments unutterable. So it is with the arguments in and around Hobby Lobby. The battle is for the definitional high ground: to define particular religious accommodations, or accommodation in general, as something that will “harm [a] state’s reputation as well as its legal culture”; to define the contraception mandate as part of a “war on religious liberty”; to define accommodations in the area of same-sex marriage as “Gay Jim Crow”; or to describe the Court’s reading of RFRA in Hobby Lobby as utterly beyond Congress’s imagining and liable to lead to terrible consequences. Or — as I have described it here — as an “easy” decision that is easy to fix.

These kinds of efforts are understandable, but deeply ironic. They are most true when they are least needed. No one expends that kind of rhetorical energy, or succeeds in sparking public interest to this extent, on an easy case involving an uncontested social issue. Hence the rhetorical heat of the Hobby Lobby moment. These arguments are inevitably pitched in terms of what the law already and incontestably is — about what RFRA, or prior cases, or the Religion Clauses themselves, “clearly” mean. It is not always evident whether those arguing in such terms believe it. Indeed, it may very well be the mark of a moment of foregrounded social contestation that the participants in the argument do believe that what they are saying is clearly and incontrovertibly right, even when they should know better.

In any event, the truth is otherwise. The important arguments in moments of deep social and legal contestation — including the Hobby Lobby moment — are not arguments about what the law is; they are assertions about what our values should be. They are a battle for the descriptive high ground: for mastery over the terms of utterability. The heated level of rhetoric in and around Hobby Lobby — seemingly everywhere but in Justice Alito’s aggressive but tempered opinion — stands as a recognition of the limits of legal reasoning in such transitional moments. It is an indirect acknowledgment that the answers to the questions posed by such cases — Is religion special? Should we accommodate it? Can we make room for both LGBT rights and religious liberty? How much room is there for pluralism in the marketplace? — lie outside the scope of any statute or judicial opinion, Hobby Lobby included. For better or worse, at least in particular moments of foregrounded legal contestation, everything is utterable and even what was once sacred is up for grabs.

The whole article is here, in PDF form.

What these pieces mean is that religious liberty is fast becoming a dead letter in American culture, especially legal culture. Pluralism around religious issues has long been considered a fundamental good, though we have naturally contested its boundaries. This country is now moving, and moving quickly, into a legal culture in which most lawyers — from whose ranks we find tomorrow’s jurists — don’t believe that.

In 2012, Dale Carpenter wrote about a survey of over 400 constitutional law professors, asking them for their personal opinions on same-sex marriage, and for their professional opinions about whether the Constitution mandates it (keep in mind that this was three years before SCOTUS judged that the Constitution does mandate it). An astonishing 87 percent of con law profs favored gay marriage, and 54 percent of them thought it was constitutionally required. Carpenter, who supports SSM, commented:

Not surprisingly, constitutional law professors overwhelmingly support same-sex marriage. Indeed, the 87% figure exceeds even what I expected. (Many among the remaining 13% volunteered that they would support the creation of civil unions or other legal protections for gay couples.) It certainly exceeds the percentage of the American people who support same-sex marriage (about 50%, depending on the poll). Indeed, I cannot think of a demographic group that can match this impressive solidarity in favor of gay marriage — including adults under 30, atheists, those with graduate degrees, and even gays themselves (among LGBT respondents in a recent poll, 85% support same-sex marriage, 12% oppose it, and 3% are unsure). This represents a huge shift toward support for same-sex marriage among constitutional law experts, who just three decades ago would have greeted the idea with bemusement if not disdain.

This is massive. Around religion, egalitarianism is smashing pluralism. Carpenter goes on to cite something I’ve heard from lawyer friends:

Support for SSM is a strong cultural and political norm in most American law schools among both students and faculty. Opposing same-sex marriage might be considered a professional disadvantage, either for those seeking tenure or for those seeking promotion.

The point is that law school culture, and professional legal culture, in America is overwhelmingly pro-SSM. Now that SSM is a constitutional reality, that does not settle the issue. If the legal world is overwhelmingly pro-gay, and religious liberty as a shared constitutional ideal is disappearing, then what do you think the future holds for religiously traditional individuals and institutions who, because of their faith commitments, dissent from gay rights orthodoxy?

Religious liberty as a constitutional right only really matters when your religious practice is unpopular. It’s one thing to hold to an unpopular belief, as long as the legal system recognizes that no matter how repugnant your belief may be to the majority, we live in a pluralistic society where some reasonable accommodation must be made for dissenters. It’s quite another when the law won’t protect you because lawyers and judges refuse to recognize that the right meaningfully exists.

This is a big reason I keep banging on about the Benedict Option. We orthodox Christians have to prepare ourselves to pay a heavy price for fidelity to what we hold to be true. Don’t lie to yourself: it’s coming. This is not alarmism. This is reality.

Our side lost the culture war. Now we have to learn to live under indefinite occupation.

UPDATE: If the only comment you have to make on this thread is the same old boilerplate “you don’t have a right to bigotry claim,” save it; I’m not going to post it. Make a substantive comment, or don’t comment at all.

March 30, 2016

Underground Railroad For Muslim Women?

I need your help, readers. Well, it’s not me, but it’s a young woman from a Muslim country who is here in the US on a visa. Her family has decided that she must return and enter into an arranged marriage. She doesn’t want to do this. The family’s relatives in the US are threatening to kill her if she doesn’t do the will of her family. She is terrified, and doesn’t know what to do.

I don’t know this woman. I was contacted by a friend and reader of this blog whom I trust absolutely, and who is trying to save this young woman’s life, and her future. I was able to put the reader in touch with some folks I know who work in this area, and who might be able to help. But the situation is extremely dire, and life-threatening. I know more about the situation than I’m letting on here, but trust me, this is real, and it’s happening right now.

The Muslim woman is afraid to talk to anybody, out of fear that her US relations will kill any American who helps her.

Can you help? Write me privately if you prefer — I’m at rod (at) amconmag — dot — com. I will pass on any useful information you give me to the reader. Don’t wait. Both the Muslim woman and the reader, who is trained in dealing with domestic violence cases, believe that her life is in danger right now. It is hard to believe this is happening in America, but, well, here we are. I’m trying to crowdsource a solution out of desperation, frankly.

It is hard to overstate the degree of terror this Muslim woman has internalized. And again, the reader, who knows the world of domestic violence trauma, believes it is real. There is evidence. That’s all I can say here. Understand that if the woman defies her family and escapes without harm, she will never be able to see them again. They have told her she will be dead to them. She is facing the prospect of being all alone, in a strange land, with no family, no friends, and nothing but her freedom. That is a very frightening prospect. Could you leave every single person you have ever known behind, forever?

Said my reader/friend:

She asked me, “If I stay and walk away from my home, my family, and my friends, what then? Can the strong woman I know I am make enough difference in this world to make up for everything I give up? And is my purpose to be the woman who starts on the path so other women have the courage to take it and go farther? Maybe I don’t become great, but some woman after me chooses this road and does something great. Was what I gave up to be the first one worth it? Am I sure I am supposed to be the first one? If so, it is worth it. If not, I give up everything in believing a lie.”

Did I mention she is an amazing young woman?

From what I understand, the woman does not want to leave her faith, but may have to for the sake of her own life, if she bolts from the arranged marriage plan. At this point, she is at the point of surrendering and returning to her home country. It breaks my reader friend’s heart. The reader and I are trying to find solutions … which is why the reader gave me permission to reach out to the rest of you.

If you can help, or have any ideas, please let me know, either privately or in the comments section. If you pray, please pray for this desperate woman.

Walker Percy & The Trumpening

Walker Percy (Photo courtesy Christopher R. Harris, who owns the copyright)

If you know anything about Walker Percy, it has probably crossed your mind to wonder what the author of Love In The Ruins would make of our current political mess. Well, if you come to the Walker Percy Weekend 2016, you can hear Matthew Sitman of Commonweal talk about it. The title of his talk is, “Where All Good Men Belong: Walker Percy & Politics in Low-Down Times”. Don’t worry, we’re not a partisan festival, and this is not going to be an occasion of argumentation and despair. We’re eating crawfish and drinking beer — that’s despair?

There’s lots of other good stuff too, including Ralph Wood and Jessica Hooten Wilson on Dostoevsky and Percy, and an exhibition of Christopher R. Harris’s photographs of Walker (see above for an example; that’s from the 2016 poster, which we will have out soon). Plus the front-porch Bourbon Stroll, the aforementioned mudbugs, cold beer, cocktails under the live oaks at Grace Church … and I’ve even gotten permission from Laura Dunn and Jef Sewell, the makers of the fantastic new Wendell Berry film The Seer, to screen it at the Percy festival. Jef and Laura are hoping to make it. If we can figure out how to fit the screening into the schedule, and find a screening room, we’ll make it happen.

If you’re the kind of person who thinks talking Wendell Berry, Walker Percy, and a sense of place with new friends while peeling boiled crawfish on a hot Louisiana summer night is fun, then you had better hurry up and buy your tickets and make your hotel reservations before the thing sells out. This year, the 100th anniversary of Walker Percy’s birth, you will have the chance to meet both of Walker and Bunt’s children, Mary Pratt and Ann. And readers of this blog will get to see familiar names and faces: Franklin Evans, Bernie, Leslie Fain, and others. The festival sold out both previous years, and once these tickets are gone, they’re gone.

It’s a great time. Come see us. You’ll be glad you did.

From the 2014 Walker Percy Weekend

Trump Attempts To Abort Candidacy

Donald Trump stepped in it bigtime:

“I am pro-life,” Mr. Trump said after a few attempts. Asked how an abortion ban would be put in place, he said, “You go back to a position like they had where they would perhaps go to illegal places. But you have to ban it.”

Finally, Mr. Matthews asked Mr. Trump, “You’re about to be chief executive of the United States. Do you believe in punishment for abortion, yes or no?”

Mr. Trump responded: “The answer is there has to be some form of punishment.”

“Ten days?” Mr. Matthews asked. “Ten years?”

Mr. Trump replied: “I don’t know,” adding, “It’s a very complicated position.”

This is how you know Trump hasn’t thought about abortion for more than five seconds, much less has had contact with the pro-life movement. Almost everybody in the pro-life movement rejects the idea of punishing women who abort their children.

It sounds illogical to the pro-choice side, and they have a point. If abortion is tantamount to murder, then why let the woman who hired the hit man abortionist get away without penalty?

The answer is because the pro-life side is not so much interested in punishing women as it is in saving the lives of unborn children. Ross Douthat, in an exchange last year with the feminist Katha Pollitt, provided a good answer to a tough question. The question below comes from Pollitt:

8. Murder. If zygotes are people, abortion is infanticide, a very serious crime. Kevin Williamson, a correspondent for National Review, has said that women who have abortions should be hanged. That’s going pretty far. After all, if every woman who had an abortion were executed, who would raise the children? But if abortion becomes a crime, what do you think the punishment should be? I’m assuming you approve of jailing the provider, but what about the parent who makes the appointment, the man who pays, the friend who lends her car? Aren’t they accomplices? And what about the woman herself? No fair exempting her as a victim of coercion or manipulation or the culture of death. We take personal responsibility very seriously in this country. Patty Hearst went to prison despite being kidnapped, raped, locked in a closet and brainwashed into thinking her captors were her only friends. Our prisons are full of people whose obvious mental illness failed to move prosecutors or juries. Why should women who hire a fetal hit man get a pass?

This is the hardest and most reasonable question, and the place where I least expect my answer to convince. But here I think the pro-choice side of the argument, the argument for not making abortion illegal at all, rests on a belief that many pro-lifers actually share: That while abortion is killing, while it is murder, it is also associated with a situation, pregnancy, that’s unlike any other in human affairs, and as such requires a distinctive legal response. No other potential murderer has his victim inside his body, no other potential murder victim is not in some sense fully physically visible and present to his assailant and the world, no other human person presents herself (initially, in the first trimester) to her potential killer in what amounts to a pre-conscious state. And again: no other human experience is like pregnancy, period, whether or it comes expectedly or not.

These are not, in my view, strong arguments for the pro-choice view that we should license the killing of millions of unborn human beings. But I think they are strong arguments for maintaining the distinctive approach to enforcement that largely prevailed prior toRoe v. Wade, in which the law targeted abortionists and almost never prosecuted women. And I don’t think pro-lifers should be afraid to say that a pregnant woman’s decision to take a first-trimester life is simply a different kind of murder than the murder of a five-year-old, and one where the law should err on the side of mercy toward the woman herself in a way that it shouldn’t in other cases, and reserve the force of prosecution for the abortionist, the man or woman who isn’t experiencing the pregnancy, instead.

This approach is, yes, exceptional in terms of how the state treats homicide. But its “exception from the general rule seems to be justified by the wisdom of experience,” as a pre-Roe court ruling put it. And while — again — pregnancy is unique, it is not the only situation where older legal forms approached killing in distinctive ways. Suicide, for instance, was historically treated as a form of murder in many jurisdictions, but attempted suicides were hardly ever prosecuted for the attempted murder that they had committed, whereas people who assisted in suicide were more likely to be charged. And a version of that distinction survives today: Suicide itself has now been largely decriminalized but assisting a suicide is still illegal, though of course a subject of much culture-war controversy, in most U.S. states.

Could one argue that this combination is illogical — that if we don’t throw attempted suicides in jail we shouldn’t make it illegal to help them make their quietus? Certainly; this is an increasingly popular position. But I think the older position, which recognizes the reality that suicide is murder but also treats it distinctively and assigns legal culpability in a particular-to-that-distinction way, is actually the one more consonant with justice overall. And in a different-but-related way, the same is true for abortion: A just society needs to both recognize abortion as murder and grapple with its distinctives, and that’s what an effective pro-life legal regime would need to do.

What Trump did was violate pro-life movement orthodoxy in a way that plays right into the hands of the left. See, they’ll say, that’s exactly what these anti-choice fanatics really want to do! It’s not remotely true, but now advocates for one socially conservative cause that’s actually making headway, however limited, will have to hit the ground distancing themselves from Trump. And this is exactly the kind of statement that will bring out feminists and liberals in droves to vote for Hillary this fall, if Trump is the nominee — especially given his long, documented history of disrespect for women.

He’s like the Pope Francis of the Republican Party. He just says whatever comes to mind.

UPDATE: Aaaaaaaand … he’s recanted.

Sanctimonious SWPL Governors

Washington Gov. Jay Inslee has joined other government officials in banning nearly all official travel to North Carolina because of the state’s law halting anti-discrimination rules.

Inslee joins New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who on Monday issued an executive order forbidding state employees from doing non-essential travel to North Carolina on state business, on account of they might not get to see man-junk in the ladies’ room, like they can at home.

I should hope that Gov. Cuomo prohibits all non-essential travel anywhere on the New York taxpayer’s dime. Why should taxpayers pick up the tab for state employee travel anywhere, unless it’s essential? Are New York state workers in the habit of making unnecessary trips to North Carolina? This might be news.

Haha! Of course this is a meaningless gesture by both Cuomo and Inslee. North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory, responding to Cuomo’s jerkbutt preening:

“Syracuse is playing in the Final Four in Houston where voters overwhelmingly rejected a nearly identical bathroom ordinance that was also rejected by the state of North Carolina,” said Governor McCrory Communications Director Josh Ellis. “Is Governor Cuomo going to ask the Syracuse team to boycott the game in Houston? It’s total hypocrisy and demagoguery if the governor does not, considering he also visited Cuba, a communist country with a deplorable record of human rights violations.”

Is it really essential for Syracuse’s team to travel to homo-hating Houston? Is sports really more important than The Principle Of The Thing?

And here’s what life is like for gays in Cuba, a communist dictatorship to which Andrew Cuomo has no aversion traveling.

Look, I get that Inslee and Cuomo reject what North Carolina is doing. But do they really want to go down this path of ostracizing states that don’t live up to their highly selective standards of ideological purity? Because two can play at that game. But we shouldn’t. It’s none of Andrew Cuomo’s and Jay Inslee’s business how North Carolinians govern their state, and it’s none of Pat McCrory’s business how New Yorkers and Washingtonians choose to govern theirs. Pat McCrory, though, does not make it his business to shun socially liberal states.

Andrew Cuomo presides over one of the most corrupt political establishments in the US. Is he really in a position to dictate morals to others?

GOP Civil War

A very angry reader writes (I’ve slightly edited for clarity and civility):

I haven’t made any secret about the fact that, at times, I’ve found your rhetoric concerning the “GOP elite” a bit over the top.

But then I read this piece on NRO’s The Corner by Jim Geraghty.Heaven knows I am not a Trump supporter in any way, shape or form, but get a load of this:

Technically we’re supposed to welcome previous Trump fans-turned-foes with open arms. But barring some miraculous comeback by Ted Cruz, the Trump campaign will have cost the Republican Party the presidency after eight years of Obama, and perhaps the Senate and even the House – and Scalia’s replacement on the Court as well. Years of effort spent attempting to dispel the accusations of inherent Republican misogyny, xenophobia, hypocrisy, ignorance and blind rage have been undone by Trump’s campaign. And every Trump advocate in front of a camera had a hand in this.

We’re not just gonna hug it out.

The reader continues:

Why did I find this infuriating? Let me count the ways:

Not a single mention of WHY people are supporting Trump, what they find attractive about his candidacy.

Not a word about how the GOP and conservatives generally have failed to advance an agenda, as candidates or actually in Congress.

Not a word about how maybe, just maybe, the GOP isn’t fielding very appealing candidates. I love Rubio’s story, but why did he never catch fire with folks? Because we’re all Trump-loving dotards? Wrong.

Not a word about how political elites from both parties have frittered away the trust of people as insider deal makers interested only in themselves.

No mention whatsoever of the very real issues that both Trump and Sanders have put forward (e.g. immigration, crony capitalism), issues that are resonating with voters, that NO establishment candidate or figure will discuss except as a talking point.And the tone of this piece! I’ll grant Gingrich is a schmendrick, but “we’re not gonna just hug it out”? He might as well tell us troglodytes to slither back to the swamps while Those Who Matter make the decisions.

I have frankly doubted your “GOP civil war” talk, but I have to admit that you may be right. Geraghty’s words are indeed fighting words — you want a fight, buddy boy, you got it.

Did you see Ross Douthat the other day schooling the Wall Street Journal editorial board, which thinks there’s nothing wrong with the GOP that another tax cut won’t fix? Excerpt:

In other words [Douthat says, summing up the WSJ’s view]: Do nothing, change nothing, and hope Trump simply does his destructive work and passes on. And if the party is reduced to actual rubble in the process, well, the important thing is that the purity of a policy vision from thirty-five years ago has been preserved in its pristine, handed-down-from-heaven form.

The best that can be said of this “strategy” is that it aspires to follow the fourth path for G.O.P. elites that David Frum (if I may quote a splittist even more defective in his interpretation of Reaganism than the reform conservatives) laid out in his essay on the Republican Party’s rendezvous with Trumpism; it redefines “political victory” to just mean “what we have, we hold,” and treats the presidency “as one of those things that is good to have but not a must-have, especially if obtaining it requires uncomfortable change.” Better to reign in the House, in this theory, than to ever compromise your way to something more; better to hunker down and hope to live through Trumpism than to sully the purity of supply-side ideas and donor priorities with anything that might pander to all the “lucky duckies” in the government-addicted 47 percent.

Douthat goes on to say that the Journal‘s proposal is “only a good strategy if your primary obsession isn’t the actual fate of conservatism, but your own power and influence within whatever rump remains.”

Similarly, I think, with Geraghty’s remarks from deep inside the conservative tank. Trump voters may end up costing the Republican Party the presidency for the third election cycle going. Exactly the wrong thing to do is to stage a Night of the Long Knives to rid the party of its unreliable element. The thing to do is to rebuild out of the rubble, keeping front to mind why grassroots Republican voters were so alienated from the party’s leadership that they chose a demagogic clown like Trump as the GOP standard-bearer.

It is not the case that everything was going well with the Republican Party until Donald Trump came along to poop in the punch bowl. But you watch: if Trump gets the nomination and loses this fall, that’s exactly the self-serving narrative that conservative elites in the donor class and throughout the movement network will tell themselves. And they’ll keep losing until they reform.

What did Edmund Burke say? “A state without the means of some change is also without the means of its conservation.” This is also true of political parties.

Can Dead Commies Be Good?

My son Matt has very strong views on communism. He went through a two-year period in which he was deeply interested in Soviet Russia, and read everything he could get his hands on about Soviet history, including Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago. A kid who will read The Gulag Archipelago at 14 is bound to be strong-minded.

He is deeply bothered by the double standard our contemporary culture has regarding Nazism and communism. He’s like me in that way. When I lived in DC in the early 1990s, a new bar opened, the theme of which was Soviet kitsch. I went there once with friends for a drink, but found I couldn’t stay. The ideology that the bar made celebrated ironically was responsible for the deaths of tens of millions, and untold human suffering. The Cold War was over, but this was still not funny, and never should be. That was my view.

That became Matt’s view too, not because he heard it from me, but because he read deeply into Soviet history. And Matt, because he had read so deeply, trying to understand how something like that could have happened to Russia, had vastly more facts to draw on to reach that conclusion than I did. Not too long ago, he was in a t-shirt shop looking around, and was so offended by the Che Guevara shirt and other communist kitsch on sale there that he left the store. I was talking to him about it afterward, and he was genuinely upset, saying that he did not understand why it’s okay to traffick in symbols of communism, but not Nazism. In his view, if we don’t see communism as equally evil as Nazism, we are not seeing it clearly, and we do a great injustice to its victims.

I told him I believe he’s right about that. I explained that the main reason for the double standard is that the left dominates the news and entertainment media, and therefore cultural framing of issues like this. You won’t find many of them endorsing communism, but by far the greater sin is anti-communism. They are less bothered by going soft on Stalin than by going soft on Joe McCarthy. Besides, there are a lot of liberals who would agree that communism went too far, but forgive the Soviets because they think their hearts were in the right place. They just wanted a better world for all (goes the thinking). I think this is morally obscene sentimentalism, but that’s how a lot of people are.

Which brings me to the case of Max Edwards, a 16-year-old Englishman who made a name for himself with a precociously written blog, The Anonymous Revolutionary, in which he expounded insightfully on the many virtues of Marxism. There was not the slightest bit of irony in this kid. Excerpts:

The USSR believed it would reach ‘true’ communism by 1980, yet was proven wrong. China, sixty-seven years after the revolution, still asserts that it’s at the beginning of the road to equality (as if it was ever on it in the first place). This is very much a final conclusion, and will certainly not be achieved with ease. Yet the communist project is not a simple, and often not a glamorous one, but one both inevitable and necessary. In the words of Fidel Castro, ‘A revolution is not a bed of roses. A revolution is a struggle between the future and the past’.

If we applied this reasoning, reaching a completely equal society in the relatively near future may not be beyond our grasp.

And this credo:

I am a Marxist, Leninist, Bolshevist and internationalist. I’d consider myself a Marxist in the

orthodox sense, which is to say that I uphold the traditional view that the tyrannies of capitalism shall only be quashed through class struggle. In that sense, I’m also an anti-revisionist and am opposed to tendencies like Post-Marxism.

To develop a more in-depth understanding of the ideals I hold, you can look at writings by and about individuals such as Marx, Engels or Lenin. I’d recommend the free online source Marxists Internet Archive to do this.

Additionally, my posts provide some of my own ideas and theoretical contributions to Marxist theory, although my views have changed significantly over the course of writing this blog, meaning that they may not be a reliable account of my current opinions. For example, I once referred to myself as a Trotskyist. No longer the case.

He even shared my son’s astonishment at the commercialization of communism. Excerpt:

Yet what really puzzles me is how the capitalist world can endorse communist imagery in such a way. Yes, it’s joked about, but not in a way that seems nearly sufficient given what the industry is actually doing. It also seems as if, by promoting the ideas of revolution, even in the shallowest sense possible, the capitalists are advertising the struggle against capitalism itself, yet I think the manufacturers (who would probably rather view themselves as someone simply building their own business and making a living, rather than a link in the global capitalist network) are probably too short-sighted to care.

In any case, I certainly believe that whoever has managed to pull this off deserves a reward. Nothing in the communist world, not even the Stalinist regime of terror and political repression, claiming to act in the interests of socialism – and thus humanity – has managed to get away with such blatant irony. Those behind the manufacturing of these products have exemplified something fascinating: they have clearly demonstrated capitalism’s remarkable ability to sell you absolutely anything, even the face of its greatest opposition.

Later, Max Edwards wrote, “Long live Bolshevism.”

Well. Grigory Zinoviev, one of the top leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution, said in 1918:

To overcome our enemies we must have our own socialist militarism. We must carry along with us 90 million out of the 100 million of Soviet Russia’s population. As for the rest, we have nothing to say to them. They must be annihilated.

And Lenin, once in power, telegrammed to Bolsheviks outside of Moscow, ordering them to engage in “mass terror.” One of his telegrams, concerning the liquidation of the kulaks (prosperous peasants) read:

“Comrades! The kulak uprising in your five districts must be crushed without pity … You must make example of these people. (1) Hang (I mean hang publicly, so that people see it) at least 100 kulaks, rich bastards, and known bloodsuckers. (2) Publish their names. (3) Seize all their grain. (4) Single out the hostages per my instructions in yesterday’s telegram. Do all this so that for miles around people see it all, understand it, tremble, and tell themselves that we are killing the bloodthirsty kulaks and that we will continue to do so …

Yours, Lenin.

P.S. Find tougher people.”

This was Max Edwards’s hero. Hey, a revolution is not a bed of roses.

Adam Jones, a genocide scholar at Yale University, has written that aside from Maoist China and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, “there is very little in the record of human experience to match the violence unleashed between 1917, when the Bolsheviks took power, and 1953, when Joseph Stalin died and the Soviet Union moved to adopt a more restrained and largely non-murderous domestic policy.” Robert Conquest, the great scholar of Stalinism, estimated that the number of victims of Bolshevism is 20 million, and in no case is lower that between 13-15 million.

As John J. Walters wrote a few years ago:

The 94 million that perished in China, the Soviet Union, North Korea, Afghanistan, and Eastern Europe easily (and tragically) trump the 28 million that died under fascist regimes during the same period.

During the century measured, more people died as a result of communism than from homicide (58 million) and genocide (30 million) put together. The combined death tolls of WWI (37 million) and WWII (66 million) exceed communism’s total by only 9 million.

And yet … Max Edwards.

I used the past tense to write about Max Edwards, because he died a few days ago at the age of 16, from cancer. In a piece published in The Guardian a week before his death, Edwards wrote:

Finally, I feel it has helped to process the whole issue selflessly. Some people might find it helpful to know that they are loved, that people care about them and that they won’t be forgotten when they die. I can understand this and I see how it’s comforting, but I also find it consoling to take the opposing view: stop dwelling on personal suffering and carry on as before.

This approach seems to help deflate the hype that terminal diagnoses carry. Pity, grief and sympathy are all natural emotions, and they certainly have their place, but I’ve found the message of “Stop whining and get on with it” far more effective. Stoicism, I feel, is more effective than grief: a simple reality-check helps to set my perspectives in place.

It helps to remind myself that even if I’m dying, it’s not all about me. At the end of the day I’m one in seven billion, a number that – like my cancer – will continue to grow and multiply over the coming months and years. While my life may be all I know, I’m nothing more than a dot on this planet. When you take into account the dozens of people I know, the billions I don’t, the thousands of miles that separate us, and the ever running river of time on which we all finitely float, you may come to the inevitable and strangely comforting realisation that we are all going to die: me, you and everyone else. Get over it.

That is both astonishingly brave and ice-cold. I could imagine the young man who wrote this saying the same thing to the wife and children of the kulak he ordered to be shot for the sake of Bolshevism.

Still, Max Edwards was a beautiful boy, and it is a terrible thing to die at 16. He was loved by his parents, who are suffering the worst thing a parent can suffer. God help them. Max recently published a book of his communist writings, which, unlike the pensées of whiz-kid fascists, is available in bookstores all over England.

Max Edwards was the same age as my son. I told Matt about Max Edwards last night, and about his death. Matt detected in my voice a sense of sorrow. He said, “Let me ask you: if he had been a teenage Nazi, would you feel the same way?”

It was a very good question. As a parent, it’s impossible for me not to feel sorrow at the death of a child, so yes, I would have felt sorrow for the dead boy’s parents, and for him, having wasted his short life propagating an evil philosophy. Besides, it’s not unheard of for smart teenagers to get obsessed with comprehensive ways of thinking about the world, to fall so in love with the ideal that they fail to see the human cost of that ideal in practice. Idealism is both the blessing and the curse of youth. Max Edwards, so far as we know, never hurt anybody. May he rest in peace, and may his family be comforted. As a Christian, I see Max as a beloved child of God, a God in Whom he did not believe, and I hope that God received Max home safe.

But I take Matt’s point: if Max Edwards had written an equally intelligent blog called, “The Anonymous National Socialist,” he would not have had a book deal, and he would not be remembered fondly in the pages of The Guardian, or any newspaper.

This is wrong. This is deeply, horribly wrong. And this is not Max Edwards’s fault. It’s the fault of our hypocritical society.

Here is a link to a blog post I wrote a couple of years ago, quoting survivors of the Rumanian gulag. In truth, this the world our young Bolshevik saint, Max Edwards, extolled. I suppose those who survived the communist dungeons should just “get over it.” Take a look at this 33-minute documentary on the horrors of the Rumanian communist prison camp called Pitesti.

This is what we honor when we play with the symbols of communism. Max Edwards dedicated himself to an evil that was no less wicked than Nazism. Why won’t we recognize that?

March 29, 2016

View From Your Table

Isle of Mull, Inner Hebrides, Scotland

This summer, Julie and I are going on a religious pilgrimage to the Isle of Mull, in Scotland’s Inner Hebrides. I’m eager to pray there, but also to eat their seafood. The peerless James C. has been there for the past few days, and sends some great shots. His description of what you see above:

Looking out across the water to the Holy Island of Iona. That’s the Caledonian MacBrayne ferry in the middle ground. I got a seafood platter of fresh local lobster, langoustines, salmon, crab and prawns (with a steaming cup of delicious cullen skink (Scottish haddock chowder) from the seafood shack at the harbour, following my return from a God-smackingly transcendent visit to Iona. There are no words!

Yes, James, but the oysters. What about the Isle of Mull oysters? The ones I am going to consume like mad once I’m there?

Alas the oysters hadn’t yet come in that day, but I managed to get some tonight in Tobermory, on the other side of the island. Transcendent. I was tempted to try slurping them with a single malt whisky, but in the end I played it safe with a delightfully dry rosé from the Pays d’Oc.

Here’s what else James got up to.

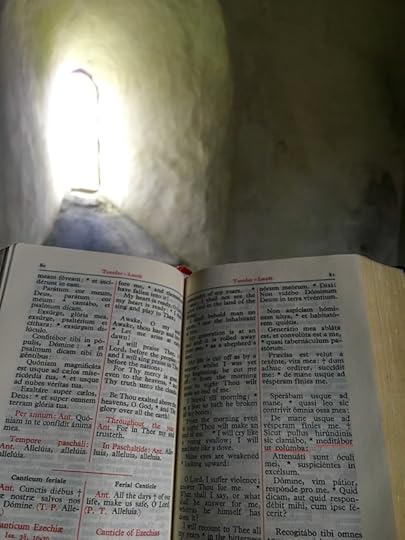

Singing Lauds all alone in the 12th-century cemetery chapel near the abbey church (you MUST pray here with your group—the echoey sound is transporting!), I came across this:

James adds:

How appropriate! St Columba, pray for us to endure this new Dark Age!

And then:

All in all, glorious. Mull is magical. Wait till you see the scenery, and the evocations of the numinous all around you.

SJW Fashion Police Brutality

Bonita Tindle, a black Social Justice Warrior, fighting the power:

Campus police at San Francisco State University have launched an investigation into a viral video that shows a female student confronting a male student on campus about his dreadlocks.

Campus officials confirmed to KRON 4 News that the video took place on campus Monday afternoon and that both individuals are students, but neither are employed by the school.

The 46-second video shows an African-American student confronting a white student on campus about his dreadlocks.

She tells him in the video that he is appropriating her culture and when he tries to walk away she obstructs his path.

“Yo, stop touching me right now,” the man says he tries to walk up the stairs. She then grabs his arm to keep him from leaving.

Where would the world be without Bonita Tindle bravely taking a stand against … hair? I ask you. Had that underfed-looking white dude chalked “Trump 2016″ in that stairwell, the campus would have had to go into lockdown.

UPDATE: SFSU has a Program In Race And Resistance Studies. Bonita Tindle was probably just doing her homework.

UPDATE.2: I agree that it looks a bit staged — Bonita Tindle doesn’t look angry — but apparently it wasn’t. The dreadlocked guy, Cory Goldstein, has been writing about it on his Facebook page. He says that he filed a complaint with the university, but doesn’t intend to file a complaint with the police.

The Sacramental Laurus

I was reading to the kids the other night from Land of the Firebird: The Beauty of Old Russia, by Suzanne Massie. It’s a wonderfully written book. Here’s a passage that caught my eye. Christianity first came to Russia in 988, with the conversion of the Kievan Prince Vladimir to Orthodoxy. In this passage, Massie explains how the Slavs brought their own traditions into the forms handed to them from Byzantium:

For the Slavs, the destines of man, animals and plants were all blended into one; they blossomed and died together. For them, beauty lay primarily in an all-embracing, all-encompassing nature. To their church, the Russians brought this close feeling for nature. The Earth was the ideal of Eternal Womanhood, and so in Russia, there never was the extreme Latin veneration and cult of the Virgin as the Virgin of Purity but more importantly as the Virgin of Motherhood, fertility, and compassion; the Virgin was rarely portrayed without a child. Permeated by this sense of unity with nature and the earth, the Russians interpreted Christians rebirth quite literally as the beautifying and transfiguration of human life. The church building itself had a twofold meaning. It embodied the significance of the Resurrection and was also part of the natural world, blending harmoniously into the landscape.

More:

The Orthodox believe that it is possible to recognize the presence of the Holy Spirit in a man and to convey it to others by artistic means. Therefore, the function of an icon painter had much in common with that of a priest, and although it was important for an icon painter to be a good artist, it was essential for him to be a good Christian. Those who painted icons had to prepare themselves spiritually: fast, pray, read religious texts, for it was a true test, not only a pictorial work in the usual sense.

… For an Orthodox worshiper, icons were far more than paintings; they were the palpable evidence of things hidden and a testimony to the possibility of man’s participation in the transfigured world which he sought to contemplate. The role of icons was not static but alive, a dynamic means by which man could actively enter into the spiritual world, a song of faith to man’s spiritual power to redeem himself by beauty and art.

It’s important to point out here that no Orthodox Christian would say that man could “redeem himself”; the theologically correct thing to say would be “a song of faith to the ability of man to enter into a redeeming communion with God through beauty and art.” God does the redeeming, but the important point here is that for Orthodox Christians, with their sacramental mentality, the entire world testifies to God’s presence in Creation. This was especially true in medieval Latin Christianity too. One of the most common Orthodox prayers even today hails God as “everywhere present and filling all things.” Laurus conveys the imagination of the medieval Russian, who does not recognize a clear division between nature and supernature. Indeed, later in the book, as he matures spiritually, the healer Arseny recognizes that the healing herbs and gestures he has been using were nothing but vehicles through which the Holy Spirit worked.

Anyway, I bring this up because these passages from the Massie book helped me put my finger on what I didn’t like in my Torchy’s Taco-buying friend Alan Jacobs’s somewhat negative review of Laurus, a novel I’ve come to love. Alan is a very sophisticated reader, but I’m wondering if his Evangelicalism caused him to miss certain aspects of this very Russian novel. (Similarly, I wonder if the fact that I have been worshiping in the Russian Orthodox tradition for almost a decade revealed certain things to me about the novel that I would not have understood without that experience.)

Alan writes:

Indeed, Jesus Christ does not play a large role in Arseny’s consciousness. He is in constant conversation not with his God but with those dear to him who have died, and this seems to be related more to his temporal dislocation than to any faithful hope for the resurrection of the dead. His constant proximity to what certain Celtic spiritual traditions call the “thin places,” where the boundaries between this world and another are porous, doesn’t seem to be related to any particularly Christian ideas. When another such porous one, traveling with Arseny through Eastern Europe, comes upon the future site of Auschwitz and senses the evil yet to come troubling the medieval air, we shudder along with him; but such disruptions of conventional realistic narrative—and there are many of them in Laurus—seem, in this reader’s mind anyway, to owe little to any identifiably Christian understanding of the supernatural.

Well, see my first point about the Orthodox imagination reading all of Nature as a revelation of the Triune God of Holy Scripture. This is, as I said, very much the same outlook as the medieval Western Christian. It did not occur to me, as a reader, to see anything particularly unusual about Arseny never, or rarely, mentioning Christ. I took it as given; his life would not make sense without Christ. I’m interested to hear from Catholic and Protestant readers of Laurus, to see if what we brought to the reading of Laurus affected our ability to grasp its message.

About the wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey stuff. The wonder-working elder, or starets, is an old and venerable figure in Russian Orthodoxy. In Orthodox Christianity, there is a long tradition of certain elders receiving the gift of clairvoyance. In recent times, St. Paisios, an Athonite monk, had this gift, and demonstrated it (this amazing book, by one of his spiritual children, discusses this at length). But he also made some wild prophecies that have not come true, and seem quite unlikely to be realized. As ever, we have to be careful and discerning about these things. The point here, though, is that in the Orthodox Christian tradition, clairvoyance is rare, but still considered a spiritual gift that God grants to a few particularly holy elders.

Second, and, I think, more important, Vodolazkin plays with the concept of Time to reveal the essential unity and timelessness of all things in God. It is a mystical insight that has a long history in Christianity. St. Benedict of Nursia, for example, was granted a vision in which he saw all of creation unified “in a single ray of light,” according to his biographer, Pope St. Gregory the Great. In Dante’s Paradiso, at the end of the pilgrim’s journey, Dante had his final vision:

O grace abounding, by which I have dared

To fix my eyes through the eternal Light

So deeply that my sight was spent in it!

Within its depths I saw gathered together,

Bound by love into a single volume,

Leaves that lie scattered through the universe.

Substance and accidents and their relations

I saw as though they fused in such a way

That what I say is but a gleam of light.

The universal pattern of this knot

I believe I saw…

Granted, this is fiction, but the point is the same: all things that exist exist in God, Who is eternal. Time is an illusion to God. This is a metaphysical point. In the late Middle Ages, many Western theologians came under the sway of Duns Scotus’s concept of “univocity,” which meant that God is not Being, but rather a being, within the broader category of Being. This began the intellectual process, aided by nominalism, that separated God metaphysically from Creation. Orthodoxy never lost that understanding, and it is still present within the Thomistic metaphysical structure of Roman Catholicism. As far as I know, it does not exist within Protestantism, and certainly it is not stressed in contemporary Catholicism. Maybe that is why such an intelligent and perceptive reader as Alan didn’t recognize this material in Laurus as Christian.

Furthermore, reviewing Laurus, Justin Lonas said:

The way time moves (or doesn’t) in Laurus is reminiscent of Slaughterhouse-Five, with Arseny “unstuck” in time. Whereas Vonnegut’s clock-play evokes an underlying banality to life, what Vodolazkin achieves is more akin to prophecy—unfolding reality with a rising spiral of metaphysics.

Events and themes seem to reverberate through the book and beyond. What occurs is never in isolation from everything else in the story, but reaches across time and space to give significance to what comes before and after. Like biblical prophecies, which so often have immediate, intermediate, and ultimate fulfillments as they ripple out from their proclamation, the phases of Arseny’s story rhyme, often with repeated phrases and mirrored scenes. For example, early in the book, Arseny sees his older self staring back at him through a fire; the same few paragraphs are retold from the perspective of the old man some 200 pages later, as they behold one another and weep together.

The one constant in time within the story is writing. Characters are constantly quoting Scripture, things of importance are always written down, and Arseny reads and re-reads a few key texts and the manuscripts his grandfather had scribbled into pieces of birch bark.

“For Christofer, the written word seemed to regulate the world. Stop its fluctuations. Prevent notions from eroding. This is why Cristofer’s sphere of interest was so broad. According to the writer’s thinking, that sphere should correspond to the world’s breadth…Cristofer understood that the written word would always remain that way. No matter what happened later, once it had been written, the word had already occurred.”

I hope you will read Alan’s review. I don’t want to overquote it, but he has some interesting things to say about the parallels between a Hindu ascetic’s life and Arseny’s. Here’s one more passage of the review I want to comment on. Alan writes of a moment in the book where Arseny asks Christ for direction in life. I’ve slightly edited this to avoid plot spoilers:

“And so, O Savior, give me at least some sign that I may know my path has not veered into madness, so I may, with that knowledge, walk the most difficult road, walk as long as need be and no longer feel weariness.” He speaks this aloud, and is overheard:

What sign do you want and what knowledge? asked an elder … . Do you not know that any journey harbors danger within itself? Any journey—and if you do not acknowledge this, then why move? So you say faith is not enough for you and you want knowledge, too. But knowledge does not involve spiritual effort; knowledge is obvious. Faith assumes effort. Knowledge is repose and faith is motion.Arseny replies, somewhat comically, that he just wants to know the “general direction” of his journey; to which the elder replies, “But is not Christ a general direction?” That Arseny does not grasp the full import of this question may be seen in the question that he in turn asks a few lines later: “Then what should I be enamored of?”

I think this scene is clearly meant to be the fulcrum of the novel—and the “repose” the elder speaks of is echoed in the title of the next section, “The Book of Repose”—but it is not clear to me that Arseny ever really understands, much less practices, what the elder says to him. Such repose as he achieves strikes me as all too consistent with what he wants from his pilgrimage’s very beginning, an atonement to be earned by lengthy penitence. To be sure, there is grace for him, but it strikes me as a novelist’s kind of grace, not God’s.

Boy, do I disagree with this conclusion — and again, I suspect the difference between Alan’s reading of it and my own may simply be theological. I can’t talk about it in too much detail without spoiling the story, so bear with me. In the novel, the Elder who gives Arseny direction is telling him that he needs to quit walking around the world looking for redemption, but to go within, to be contemplative, not active, and to meet Christ there. In the stunning conclusion of the novel, Arseny — now called Laurus — sacrifices everything he had gained in life, in radical humility, to save the life of someone who wronged him. Because of Christ, and through Christ, he lived as Christ when he was put to the test. That is not “earning” atonement, but the ultimate repentance of the sin of Pride, which is what caused Arseny’s terrible fall as a young man — a fall that resulted in two deaths. If it weren’t for Arseny’s radical death to self as a Christian monk and ascetic, he would not have been open to the grace that allowed him to offer himself in the place of another.

By the way, Vodolazkin addressed these themes himself in the interview I did with him:

RD: I think one of the most important moments in Laurus occurs when an elder tells Arseny, who is on pilgrimage, to consider the meaning of his travels. The elder advises: “I am not saying wandering is useless: there is a point to it. Do not become like your beloved Alexander [the Great], who had a journey but no goal. And do not be enamored of excessive horizontal motion.” What does this say to the modern reader?

That it is time to think about the destination, and not about the journey. If the way leads nowhere, it is meaningless. During the perestroika period, we had a great film, Repentance, by the Georgian director Tengiz Abuladze . It’s a movie about the destruction wrought by the Soviet past. The last scene of the film shows a woman baking a cake at the window. An old woman passing on the street stops and asks if this way leads to the church. The woman in the house says no, this road does not lead to the church. And the old woman replies, “What good is a road if it doesn’t lead to a church?”

So a road as such is nothing. It is really the endless way of Alexander the Great, whose great conquests were aimless. I thought about mankind as a little curious beetle that I once saw on the big road from Berlin to Munich. This beetle was marching along the highway, and it seemed to him that he knows everything about this way. But if he would ask the main questions, “Where does this road begin, and where does it go?”, he can’t answer. He knew neither what is Berlin, nor Munich. This is how we are today.

Technical and scientific revelation brought us the belief that all questions are possible to solve, but that is a great illusion. Technology has not solved the problem of death, and it will never solve this problem . The revelation that mankind saw conjured the illusion that everything is clear and known to us. Medieval people, 100 percent of them believed in God – were they really so stupid in comparison to us? Was the difference between their knowledge and our knowledge as different as we think? It was not so! I’m sure that in a certain sense, our knowledge will be a kind of mythology for future generations. I reflected this mythology with humor in Laurus, but this humor was not against medieval people. Maybe it was self-irony.

RD: Timelessness is one of the main ideas of Laurus, which leaps suddenly and unexpectedly from the medieval present, to our own time. What does this mean?

EV: Time doesn’t exist. Of course time exists if we’re speaking in everyday terms, but if we think from the perspective of eternity, time doesn’t exist, because it has its end point. For medieval people, God was the most important thing about life, and the second most important thing was Time. On the one hand, medieval people lived rather short lives, but on the other hand, life was very, very long, because they lived with their minds in eternity. Every day is an eternity in the church, and all that surrounded these people. Eternity made time very long, and very interesting.

If you would think about the first patriarchs, Adam, Methuselah, and others, they had an incredible long life. Adam lived 930 years, Methuselah lived, as far as I remember, 962 years. Because they had eternity in their memories, eternity could not disappear at once. This eternity disappeared slowly, dissipated in the long life of the patriarchs. Medieval people, by comparison to us, are these patriarchs. Their life was very long because they had as part of daily life this vertical connection, the connection to the divine realm, a connection that most of us in modernity have lost.

The book is Laurus. Evgeny is flying all around now, getting ready for the release of his follow-up novel, The Aviator, which comes out on April 8 (not sure when it will be released in English). Not sure what the plot of this one is, but he tells me it is very different from Laurus. You can imagine how anxious I am to read it.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 509 followers