Rod Dreher's Blog, page 601

March 23, 2016

Millennial Landslide

Wouldn’t want to disturb your complacency or anything, but here’s news:

The percentage of Americans who prayed or believed in God reached an all-time low in 2014, according to new research led by San Diego State University psychology professor Jean M. Twenge.

A research team that included Ryne Sherman from Florida Atlantic University and Julie J. Exline and Joshua B. Grubbs from Case Western Reserve University analyzed data from 58,893 respondents to the General Social Survey, a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults administered between 1972 and 2014. Five times as many Americans in 2014 reported that they never prayed as did Americans in the early 1980s, and nearly twice as many said they did not believe in God.

Americans in recent years were less likely to engage in a wide variety of religious practices, including attending religious services, describing oneself as a religious person, and believing that the Bible is divinely inspired, with the biggest declines seen among 18- to 29-year-old respondents. The results were published today in the journal Sage Open.

“Most previous studies concluded that fewer Americans were publicly affiliating with a religion, but that Americans were just as religious in private ways. That’s no longer the case, especially in the last few years,” said Twenge, who is also the author of the book, “Generation Me.” “The large declines in religious practice among young adults are also further evidence that Millennials are the least religious generation in memory, and possibly in American history.”

This decline in religious practice has not been accompanied by a rise in spirituality, which, according to Twenge, suggests that, rather than spirituality replacing religion, Americans are becoming more secular. The one exception to the decline in religious beliefs was a slight increase in belief in the afterlife.

“It was interesting that fewer people participated in religion or prayed but more believed in an afterlife,” Twenge said. “It might be part of a growing entitlement mentality — thinking you can get something for nothing.”

Of course. One of the tenets of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism is that God wants little more from you than to be happy and nice, and everybody is going to heaven except people like Hitler. We must have that psychological hedge to wall off the abyss, and to prevent us from having to consider the full implications of atheism. Nietzsche and Sartre were far more honest atheists.

There’s a new study out in the American Journal of Sociology that challenges the long-held thesis that the United States is an outlier in secularization, compared to Europe. The abstract:

Virtually every discussion of secularization asserts that high levels of religiosity in the United States make it a decisive counterexample to the claim that modern societies are prone to secularization. Focusing on trends rather than levels, the authors maintain that, for two straightforward empirical reasons, the United States should no longer be considered a counterexample. First, it has recently become clear that American religiosity has been declining for decades. Second, this decline has been produced by the generational patterns underlying religious decline elsewhere in the West: each successive cohort is less religious than the preceding one. America is not an exception. These findings change the theoretical import of the United States for debates about secularization.

A year ago, Peter Foster of the Telegraph quoted David Voas, a co-author of the new study, saying that America appears to be on the same track towards unbelief as Europe:

Analysis of European secularisation might provide us some pointers for the US going foward. There, according to analysis by David Voas, a sociologist at Essex University, it is clear that the rise of so-called “fuzzy fidelity” – ie those with no explicit religious affliation, but who still believe in some kind of higher power and go to church on Christmas – has proved to be a “staging post on the road from religious to secular hegemony”.

“Indifference,” Voas writes in his 2008 paper The Rise and Fall of Fuzzy Fidelity in Europe, “is ultimately as damaging for religion as scepticism.”

If that’s the case in the US, then the belief among many Evangelicals that the “nones” are still fundamentally religious may prove to be wishful thinking.

Pardon me for re-quoting some material I put up in the Donald Trump post earlier today. I do this for people who come to this blog through Twitter, and who wouldn’t necessarily have seen much of this material in that post from this morning. Earlier this week, I read Lost In Transition: The Dark Side of Emerging Adulthood, a 2009 book by sociologist Christian Smith and several academic colleagues. It’s about the moral lives of 18-23 year olds, who, I guess, would be in their mid-20s and early 30s today. It is a depressing study to read. Too many details to get into here, but the basic finding is that most Americans of that generation believe in nothing outside their own feelings, and cannot even make an argument for much of anything. It’s all about what they feel. They are completely obsessed by material, sensate culture, and aspire to nothing higher than being comfortable, entertained, and happy. Here’s an excerpt from the book:

Ultimately we come back to core existential questions. What are humans? Do they have any purpose? If so, what is it? What is good in life and the world? How do we make sense of suffering, tragedy, evil, and death? Are history and the world going somewhere meaningful, or is it all just random chance? Our point is not to push particular answers to these questions. Our point is that human beings and cultures recurrently, inescapably ask and answer these questions one way or another. For better or worse, people and cultures recurrently find themselves drawn to answers that reflect horizons that are higher, bigger, more transcendent, or more meaningful than the prosaic, immanent, natural, mundane world. Humanity can live for some time on mere bodily comfort and material security. But over time that does not seem to satisfy the human spirit. Such a limited horizon cannot last. Either material security gives way or the human spirit seeks to push beyond it. If so, then the standard cultural horizons of most emerging adults today, and thus of the culture that has raised them, cannot be said to reflect a high point of the human imagination and aspirations.

The authors emphatically do not blame these emerging adults, but rather the older adults — parents, teachers, churches, communities, institutions — who formed them. “But if these emerging adults are lost, it is because the larger culture and society into which they are being inducted is also lost,” the authors write. More:

We are failing to teach them how to deal constructively with moral, cultural, and ideological differences. We are failing to teach them to think about what is good for people and in life. We are failing to equip our youth with the ideas, tools, and practices to know how to negotiate their romantic and sexual lives in healthy, nondestructive ways that prepare them to achieve the happy, functional marriages and families that most of them say they want in future years. We are failing to teach our youth about life purposes and goals that matter more than the accumulation of material possessions and material comfort and security. We are failing to challenge the too-common need to be intoxicated, the apparent inability to live a good, fun life without being under the influence of alcohol or drugs. And we are failing to teach our youth the importance of civic engagement and political participation, how to be active citizens of their communities and nation, how to think about and live for the common good. On all of these matters, if our analysis is correct, the adult world is simply abdicating its responsibilities.

Moreover, if our analysis is correct, we in the older adult world are failing youth and emerging adults in these crucial ways because our own adult world is itself also failing in those same ways. It is not that the world of mainstream American adults has something great to teach but is simply teaching it badly. That would also be a problem, but at least a remediable one. Rather, we suspect that the adult world is teaching its youth all too well. But what it has to teach too often fails to convey what any good society needs to pass on to its children.

In short, if our sociological analysis in this book is correct, the problem is not simply that youth are bad students or that adults are poor teachers. It is that American culture itself seems to be depleted of some important cultural resources that it would pass on to youth if it had them — and yet not just for “moral” but also for identifiable institutional reasons, as repeatedly noted above. In which case, not only emerging adulthood, but American culture itself also has a dark side as well.

The point of the book is not that Millennials are bad people, but rather that they have not been given any clear way to determine what is right and what is wrong, and how to use their reason. So they fall back on what feels right in a given moment. We have thrown our kids into the deep end of a pool, but failed to teach them how to swim.

And look at this finding:

What we have found so far is, first, that 61 percent of emerging adults we interviewed have no problems or concerns with American materialism and mass consumerism. These emerging adults are essentially quite happy with our social system of shopping, buying, consuming, and disposing. Second, another 30 percent of emerging adults mention certain concerns about mass consumerism, but none they think they can do anything about and none that especially affects how they personally think or live. … Structuring and governing the outlooks of nearly all of the 91 percent of interviewed emerging adults represented above is the dominant cultural paradigm of liberal individualism. … All that society is, apparently, is a collection of autonomous individuals who are out to enjoy life.

This is who we are. This is who we have raised our kids to be, whether we intended to or not. Smith et al. warn against “doom-and-gloomers,” though I’m not quite sure why, and they also warn against older adults who say, “Aww, that’s how kids are, they’ll grow out of it.” That’s a dangerous complacency, they say. And they also warn against drawing firm conclusions based on anecdotal data. They say there’s a lot of bad journalism out there that sees, for example, young people volunteering for political campaigns, and concludes, “See, the kids really are all right. They’re engaged!” The sociological data do not remotely justify that conclusion.

It is not going to get any better in the foreseeable future, only worse, and more difficult. This is why we orthodox Christians who want to resist the spirit of the age, and who want to raise kids able to be resilient, need the Benedict Option. Church youth group, parochial or religious school, and church on Sunday is not enough. Not remotely enough.

Donald Trump, Über-American

On Monday, I read a 2009 book by sociologist Christian Smith and his research team, called Lost In Transition: The Dark Side of Emerging Adulthood. It talks about the inner lives — the moral lives — of young adults 18-23.

We are failing to teach them how to deal constructively with moral, cultural, and ideological differences. We are failing to teach them to think about what is good for people and in life. We are failing to equip our youth with the ideas, tools, and practices to know how to negotiate their romantic and sexual lives in healthy, nondestructive ways that prepare them to achieve the happy, functional marriages and families that most of them say they want in future years. We are failing to teach our youth about life purposes and goals that matter more than the accumulation of material possessions and material comfort and security. We are failing to challenge the too-common need to be intoxicated, the apparent inability to live a good, fun life without being under the influence of alcohol or drugs. And we are failing to teach our youth the importance of civic engagement and political participation, how to be active citizens of their communities and nation, how to think about and live for the common good. On all of these matters, if our analysis is correct, the adult world is simply abdicating its responsibilities.

Moreover, if our analysis is correct, we in the older adult world are failing youth and emerging adults in these crucial ways because our own adult world is itself also failing in those same ways. It is not that the world of mainstream American adults has something great to teach but is simply teaching it badly. That would also be a problem, but at least a remediable one. Rather, we suspect that the adult world is teaching its youth all too well. But what it has to teach too often fails to convey what any good society needs to pass on to its children.

In short, if our sociological analysis in this book is correct, the problem is not simply that youth are bad students or that adults are poor teachers. It is that American culture itself seems to be depleted of some important cultural resources that it would pass on to youth if it had them — and yet not just for “moral” but also for identifiable institutional reasons, as repeatedly noted above. In which case, not only emerging adulthood, but American culture itself also has a dark side is well.

That’s the heart of it. The book is filled with sociological data and personal interviews with the 18-23 year olds the team studied. If I got started writing specifics, I would be on this blog all day. It’s a fascinating book. In this post, though, I want to focus on a particular aspect of the study: the thorough emotivism of that generation.

Smith et al. found that most of the emerging adults (EAs) they studied have no way to think through moral and ethical dilemmas. None. They go with their gut. They are terrified of proclaiming moral rules that everyone should follow, lest they seem judgmental. Broadly speaking, they believe that if an action makes you happy, then it is good, for you — even if they themselves could not imagine doing the same thing. “Moral individualism” is the rock upon which their inner lives are built, with “moral relativism” a significant additional source for many of them. If they feel something is true or right, then it must be so.

This is emotivism, and it is impossible to reason with. As MacIntyre has said, you cannot have a cohesive society built around emotivism. Public rationality and deliberation become impossible.

Smith et al. stress repeatedly that this did not come out of the blue. The individuals and institutions (church, school, media, etc.) that formed these EAs are to blame, because these EAs cannot have what they were not given. The authors also stress that older adults who say that kids will be kids, and that they will grow out of it, are engaging in a dangerous “complacency” about the situation. The point, as the authors say above, is not that there is something wrong with the Millennial generation (though there is); the point is that the moral vacancy of the young indicates that there is something wrong with America. We have become the sort of country in which most people decide right and wrong based on what they desire. Reasoned deliberation based on an objective set of principles is not what we do.

Which brings us to this Scott Adams blog post about Donald Trump. Excerpts:

Donald Trump is a con man. He’s also a fraud, a liar, a snake-oil salesman, and a carnival barker. Clearly he is running a scam on the country.

Trump calls himself a “deal-maker.”

I call Trump a Master Persuader.

It’s all the same thing. Trump says and does whatever he needs to do in order to get the results he wants. And apparently he does it well. Given the facts, you can either see Trump as highly skilled or morally flawed. Maybe both. I suppose it depends which side you are on.

More:

The evidence is that Trump completely ignores reality and rational thinking in favor of emotional appeal. Sure, much of what Trump says makes sense to his supporters, but I assure you that is coincidence. Trump says whatever gets him the result he wants. He understands humans as 90% irrational and acts accordingly.

Rand Paul, on the other hand, treated voters as if they were intelligent creatures who make decisions based on the facts. His campaign didn’t last long with that message. Rand Paul knows about a lot of stuff. He’s a smart guy. But apparently psychology is not on the list of things he knows. And psychology is the only necessary skill for running for president.

Trump knows psychology. He knows facts don’t matter. He knows people are irrational. So while his opponents are losing sleep trying to memorize the names of foreign leaders – in case someone asks – Trump knows that is a waste of time. No one ever voted for a president based on his or her ability to name heads of state. People vote based on emotion. Period.

You used to think Trump ignored facts because he doesn’t know them. That’s partly true. There are plenty of important facts Trump does not know. But the reason he doesn’t know those facts is – in part – because he knows facts don’t matter. They never have and they never will. So he ignores them.

Right in front of you.

And he doesn’t apologize or correct himself. If you are not trained in persuasion, Trump looks stupid, evil, and maybe crazy. If you understand persuasion, Trump is pitch-perfect most of the time. He ignores unnecessary rational thought and objective data and incessantly hammers on what matters (emotions).

Read the whole thing; it’s seriously good.

Trump is the Uber-American, a man of his time. When you look at him, America, you see yourself in the mirror. We made him. He is us. Crass, passion-driven, materialistic, vain — this is who we have become.

There is not a lot of difference between Donald Trump and the campus Social Justice Warriors who base their thinking and appeal entirely on emotion. Except Trump is a lot better at it, and there are a lot more Trump supporters in this country than there are Social Justice Warriors. The difference is that the SJWs stand a good chance of moving into the institutions through which power flows in this country. But guess what? Trump stands to seize the most important institution: the presidency of the United States.

‘The World’s Wealthiest Failed State’

The country of just 11.2 million people faces widening derision as being the world’s wealthiest failed state — a worrying mix of deeply rooted terrorist networks; a government weakened by divisions among French, Dutch and German speakers; and an overwhelmed intelligence service in seemingly chronic disarray.

It is also home to what Bernard Squarcini, a former head of France’s internal intelligence, described as “a favorable ecosystem: an Islamist milieu, and a family milieu,” which played an important role in sheltering Mr. Abdeslam and also perhaps in Tuesday’s attacks.

“It shows that they were in a neighborhood that can shelter cells for months, because it is a neighborhood that is favorable to them,” he said, referring to Molenbeek, a Brussels district. It is where the Paris attackers lived and where Mr. Abdeslam was able to hide among family and friends.

The cultural code of silence in the heavily immigrant district, as well as widespread distrust of already weak government authorities, has provided what amounts to a fifth column or forward base for the Islamic State.

More:

Others emphasized that progressive layers of new security measures can go only so far. Absent a military-style occupation, the threat from a well-established network with some degree of local complicity can never be completely forestalled, experts said.

“This shows the limits of the actions you can undertake in a state of emergency,” like the one Belgium had in place for weeks, said Philippe Hayez, a former official with the D.G.S.E., the French external intelligence service.

“These are time-specific, superficial,” added Mr. Hayez, who has written extensively on Europe’s intelligence challenges. “But unless you occupy it militarily, you don’t hold a town just by circulating police cars. We’re talking about guerrilla terrorism. And there’s a population that’s complicit.”

Read the whole thing.

There’s a population that’s complicit. In Belgium last month, 100 refugees in a camp got into a massive brawl over a Syrian woman who refused to wear a headscarf. Yes, by all means, bring more men like this into Europe, Chancellor Merkel. What could possibly go wrong?

SJWs Will Elect Trump, Round 2

A reader at Emory University in Atlanta writes with news that the campus is freaking out because someone wrote “TRUMP 2016″ on the sidewalk there, and put other pro-Trump graffiti around campus. New York magazine’s Jesse Singal writes:

The article gives no indication the chalkings were themselves racist or otherwise offensive, other than that they expressed support for a gross political candidate, though one did read “Accept the Inevitable: Trump 2016.”

A group of activists responded on Monday not by laughing at how any of their students could be dumb enough to support a tiny-handed buffoon, or chalking their own anti-Trump messages, but by going nuclear — at least by college-student standards: They immediately started protesting the Emory administration and, eventually, confronted the president himself for failing to act against the the brutal overnight mass-chalking.

The mewling children confronted Jim Wagner, Emory’s president, in the administration boardroom and, after talking about their feelings, lit into him. From the Emory student newspaper’s account:

University President James W. Wagner, who had been standing just inside the threshold of the door, had been called into the board room by students and listened at the head of the table while they described how the appearance of the chalkings made them feel. He addressed several questions throughout the time in the board room, including “Why did the swastikas [on the AEPi house in Fall 2014] receive a quick response while these chalkings did not?” to which Wagner replied that they “represented an outside threat” and clarified that it was a second set of swastikas that received a swift response from the University. “What do we have to do for you to listen to us?” students asked Wagner directly, to which he asked, “What actions should I take?” One student asked if Emory would send out a University-wide email to “decry the support for this fascist, racist candidate” to which Wagner replied, “No, we will not.” One student clarified that “the University doesn’t have to say they don’t support Trump, but just to acknowledge that there are students on this campus who feel this way about what’s happening … to acknowledge all of us here.”

Naturally, they also demanded greater “diversity” in the faculty and “higher positions” at the university.

I would like to report that Jim Wagner, an actual adult who leads a real university, stood up to this mob, told them to grow the freak up, learn to respect free speech, and to get the hell out of his office and back to class. Wouldn’t that be nice? Nope, he caved. They always do. Gutless, spineless, useless cowards that they are. And get this: Emory says it’s going to use security cameras to try to identify the chalkers, and, if possible, punish them. Jesse Singal writes:

A college using using security-camera footage to track down and possibly punish students who expressed political speech? The only way to fairly describe that is, well, the only way to fairly describe the spectacle of a Trump rally delivered to a deliriously cheering crowd: extremely creepy, and a sign that something has gone seriously wrong.

Indeed. Later, the Student Government sent out a letter campus-wide (full text below), saying that it’s their policy not to endorse particular candidates or political positions, and “committed to an environment where the open expression of ideas and open, vigorous debate and speech are valued, promoted, and encouraged,” per official university policy. That said, OMG, Trump! Some of our students feel unsafe because there are Trump supporters on campus, and triggered by the words, “Trump 2016″!

The Student Government at Emory University — I remind you, an actual college — is providing “emergency funds” to pay for any SJW encounter group to get together to talk about how they are all traumatized and emotionally incapacitated by anonymous persons expressing support for a candidate for President of the United States. I’m not making this up. Read the letter below.

But first, this comment by the reader who sent me the information about this appalling incident:

So [for the SJWs], there is no legitimate reason why one might publicly express support for Trump, even in jest, even in response to (or in order to provoke) precisely this kind of priggish, self-righteous pathologization of dissent from SJW orthodoxy.

I largely share your opinion of Trump, the man is a clown and possibly a dangerous one. Not in the Hitler/Mussolini sense–that’s ridiculous–more in the George W. Bush way of being completely out of his depth. At the same time, he is literally the only person in either party right now who is willing to tell these people where to shove it. That doesn’t mean that I trust he wouldn’t immediately cave to the SJW cadres in corporate America… but on the other hand, I know with 100% certainty that Hillary will be right there at the forefront, leading the charge. So it goes with just about everything.

So I don’t know. I find myself a lot more ambivalent about Trump than you seem to be.

I told the reader that it takes everything in me to remind myself that just because Trump makes these idiots lose their mind does not make Trump a safe bet to run the most powerful nation on earth. But the reader is right: it is breathtaking that this kind of thing happens over and over and over again on university campuses, and not a single leader except Donald Trump dares to confront the issue of liberal student mobs trampling the principle of free speech and free expression. What a scandal!

Last night, on a different post, a reader invited me to consider what the country would be like if Trump loses and the SJWs feel that they had a hand in that. It is by no means unreasonable to consider what a Hillary Clinton administration would do both concretely and in terms of setting the tone for toleration of free speech in this country. I think it would get worse than it is now. That concern cannot be easily dismissed. Very few liberals ever stand up to the SJWs when confronted by their insane intolerance. I’m telling you, in the same way that normal Republicans rarely if ever said anything to the right-wing nuts who demonized any opposition (Marxists! RINOs!), because it suited their purposes to keep the fire stoked up on their side, and now the fire is consuming them — the same thing is going to happen to the liberals. I can easily see why people on the right who may not like Trump are tempted to vote for him because he’s the only one who doesn’t give a rip what they think, and will say so. That is his best quality, according to me.

Here’s the letter from the Emory Student Government to the inmates at an asylum where you pay $45,700 yearly in tuition and fees to be coddled by administrators who allow themselves to be bullied by petulant children who weaponize petty grievances:

Yesterday, students awoke to find the statements, “Accept the inevitable, Trump 2016”, “ Vote Trump 2016”, “Build the Wall” among others displayed prominently on property and public buildings in and around central campus.

First, as student advocates and population-wide representatives, we do not endorse any particular candidate or any political philosophy, as to do so would be to overstep the authority of our offices and to abuse the public trust placed in us. As we are the principal organizations tasked with advocating for concerned members of the community, we remain “committed to an environment where the open expression of ideas and open, vigorous debate and speech are valued, promoted, and encouraged” pursuant to our University’s Open Expression Policy.

That being said, by nature of the fact that for a significant portion of our student population, the messages represent particularly bigoted opinions, policies, and rhetoric directed at populations represented at Emory University, we would like to express our concern regarding the values espoused by the messages displayed, and our sympathy for the pain experienced by members of our community.

We remain unapologetically dedicated to inclusion, diversity, and equity, but even more so, we remain unwavering in the premium we place on the safety, physical and emotional, of the students we represent. Any language that has to do with a person’s identity that creates an unsafe or unproductive educational environment directly undermines the respect for one another that time and time again we as a community have rallied behind. This display endorses such language, and having served to divide us as a community, runs antithetical to this principle of respect.

Let this not undo the important work that has begun this year or undermine efforts of this institution to better itself nor the important dialogues that have begun as a result of the Racial Justice Retreat. Let this serve only as a reminder of why such work is so important. Should we use this as an opportunity to come closer together instead of moving further apart, we will finally be choosing action over words and taking measurable steps toward true community.

It is clear to us that these statements are triggering for many of you. As a result, both College Council and the Student Government Association pledge to stand in solidarity with those communities who feel threatened by this incident and to help navigate the student body through it and the environment of distrust and unease it has created.

To that end, Emergency Funds within the College Council monetary policy were created to provide time-sensitive funds during circumstances involving discrimination based on race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, and such funds are available to any student organization looking to sponsor events in response to this incident. Additionally, we are personally available to discuss how we can make Emory a more supportive environment for you. We are holding open office hours this week during the following times:

Thursday 3:30 – 5:00 PM (College Council Office in Eagles Landing)

Thursday 10:00 – 11:00 AM (SGA Office in Eagles Landing

>We address you, our classmates, to reaffirm the commitment of both College Council and the Student Government Association to fostering a community that stands against violence, prejudice, and hate. A community that promotes safety, respect, thoughtful dialogue, and sustained social change. As representatives of this community, we hear you, we see you, and we stand with you.

Should you find that you have comments, questions, concerns, or a desire to talk through this incident or the way in which it has affected you, please feel free to reach out to any of us.

Sincerely,

-The 60th College Council

-Max Zoberman; 50th Student Government Association President

-Gurbani Singh; 50th Student Government Association Executive Vice President

March 22, 2016

America Is Not A Reality Show

Ross Douthat, continuing to crack the whip hard on Republicans who won’t stand up to Trump, and thereby are complicit in handing over the GOP to Trump:

The irony is that I say all this as someone who has little love for the Republican Party as it currently exists, who was initially happy with the prospect of some Trumpian creative destruction, who might ultimately prefer the party that (eventually) emerged from the post-Trump rubble to what we have right now. So I’m not sure what it says that I (and not a few others in the reform-minded conservative commentariat) now seem to feel more urgency about stopping Trump than the men who actually lead the actual-existing G.O.P.

That we enjoy the liberty of punditry rather than wearing the manacles of politics is no doubt part of it. Still, since pundits are also prone to overreaction, it’s important to keep in the mind the possibility that we’re wrong, that we’re being hysterical, that Trump’s progress isn’t a good reason to suspend the normal rules of politics or deliberately split the party or otherwise go to anti-Trump extremes.

And I try to keep that possibility in mind. But you know, read the transcript of Donald Trump’s meeting with the Washington Post editorial board. Just read it. This is from yesterday, less than twenty-four hours before the atrocity in Brussels. This is the man who will be the Republican nominee for president, representing the party of Eisenhower and Nixon and Reagan and George H.W. Bush, at a moment when the Western/liberal order is more fragile than it’s been since 1991. [Emphasis mine — RD] And of all the leaders of the Republican Party, all the men and women who hold high office, is history really going to record that this demagogic, blathering clown was opposed forthrightly and absolutely only by a defeated presidential nominee, a Senate backbencher, and a retired Senator lately recovered from cancer? Really?

I had not thought Trump had undone so many.

I pretty much agree with this, and I say that as someone who takes real pleasure in the devastating walloping Trump is giving to the GOP, and who is sympathetic to many of the concerns Trump is alleged to have about the direction of America. But when the man took the stage in the televised debate a couple of weeks ago and assured the nation he seeks to lead that his penis was big, that’s when I knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that the country would be taking an extreme risk putting a man like that in the White House. So, look, if you haven’t read the WaPo transcript, you really should. He went in there to meet with the editorial board of the major newspaper in the nation’s capital, and he talked about his penis, and his real estate prowess.

Can you imagine somebody with a temperament like that as Commander in Chief of the US Armed Forces? Can you imagine someone so utterly trivial in the White House? Here is a man who has suddenly emerged as possibly the most significant American political figure since Reagan, a man who has, in less than a year, nearly destroyed the once-formidable Republican Party from within, and yet he still finds time to bitch on Twitter about a Fox newscaster:

So the highly overrated anchor, @megynkelly, is allowed to constantly say bad things about me on her show, but I can’t fight back? Wrong!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 20, 2016

No, you juvenile boob, you can’t fight back, because you are running for President of the United States, and you ought to be above staging a pissing contest with a newsreader. America is not a reality show!

And you can never really be sure what Trump truly stands for, because he doesn’t know himself. This morning, he said on the news that we should close our borders in response to the ISIS attack in Brussels. Then he turned around and denied he said it. Here is the evidence. Remember when he flip-flopped on the H1B visas? The man does not know his own mind. He just says whatever pops into his head and suits his interests at the time.

On the other hand, Ted Cruz. Gack. What a wretched election we face. Notice, by the way, the news today about the woman the Republican Party chose to run as vice president in 2008:

The gavel is in Sarah Palin’s court — well, it will be.

The former Alaska governor will star in a reality-TV courtroom, according to a report from People magazine.

Palin signed a deal in February to preside over a “Judge Judy”-type show expected to premiere in the fall of 2017. A source told People that the Donald Trump surrogate will meet with stations, create a pilot episode and then sell it.

The Threat From ‘Extreme’ Christians

A day like today, with dozens dead and hundreds injured in Brussels because of Islamic extremists, makes all of us more anxious about religious fanaticism. All of us who are not Islamic extremists ourselves agree that what ISIS did in Brussels qualifies as religious extremism.

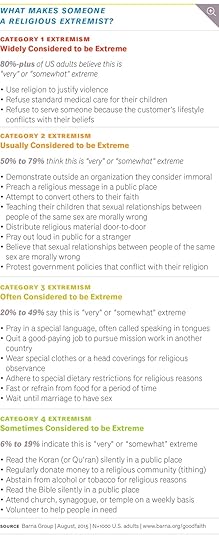

But here’s something disturbing from the Barna Group, the Evangelical Christian research firm: huge numbers of Americans believe that things that were until just yesterday considered a normal part of American life are now “extremist”. Look at this chart:

From Barna Research

Says David Kinnaman, head of Barna:

“The research starkly demonstrates the ways in which evangelicals and many practicing Catholics are out of the cultural mainstream. In fact, skeptics and religiously unaffiliated are now much closer to the cultural ‘norm’ than are religious conservatives. In other words, the secular point of view, which says faith should be kept out of the public domain, is much closer to the mainstream in U.S. life.

“This fact explains why millions of devout Christians are experiencing such frustration and concern. They are feeling out of step with social norms and the cultural momentum. This is most significantly felt when it comes to social views, such as evangelicals’ convictions on same-sex relationships. However, the perception of ‘social extremism’ also applies to many other beliefs and practices, including personal evangelism and missions work.”

Kinnaman and Gabe Lyons have a new book out, Good Faith, in which they address these new social and cultural realities that orthodox Christians have to navigate in post-Christian America.

On The Atlantic‘s site, Evangelical writer Jonathan Merritt says that casual use of the word “extremist” is dangerous:

In an age of religious terrorism, “extremist” is too damaging a word to be tossed around with such little discretion. When society slaps the E-word on something, it marks it for marginalization. And if the data is right, tens of millions of religious Americans may be at risk of being ostracized, sidelined, or banished from social acceptability because of their beliefs. These are the very communities best positioned to attack genuine religious extremism. But labeling them ‘extremist’ simply encourages alienation and radicalization.

One of the great ironies of this politically correct age is how those who most champion tolerance are often in such great need of the virtue themselves. Society calls “extremist” those believers they consider to be rigid, narrow-minded, and unaccepting of others.

Carelessly painting such wide swaths with a caustic descriptor is its own form of intolerance. It’s refusing to accept those who are less accepting. It’s coercing someone to convert to your way of thinking to keep them from converting others to their own. It’s marginalizing one group to keep them from shaming some other marginalized group. It contributes to the very problem it’s trying to solve.

Amen. Look, if you are a religious conservative of any sort, this is going to affect you. “Extremist” means “dangerous.” This is the country, and the culture, in which we live now. You had better find the sources for resilience, or you’re not going to make it through with your faith intact, nor will your kids. Like I said at the Q Conference last year in Boston, you can be as winsome as you like, but if you’re faithful to orthodox Christianity, they’re still going to hate you.

Benedict Option, Augustine Option

Powerful speech by Philadelphia’s Catholic Archbishop Charles Chaput at BYU today. Excerpts:

I have a friend of many years, a man committed to his wife and family, well-educated and very Catholic, whose son attended West Point. Over the years he’s taken great pride in his son, and in the ideals of the military academy. He’s still proud of his son. And he still admires the legacy of West Point.

But he would never send another child to a service academy. He simply doesn’t believe that America, as it currently stands, is the same country he once loved. And, in his words, it’s not worth risking a son or a daughter to fight for it. The America he sees now—an America of abortion, confused sex, language police, entitlements, consumer and corporate greed, clownish politics, and government bullying of religious groups like the Little Sisters of the Poor—is different in kind, not merely in degree, from the nation he thought he knew. It’s no longer a country he considers his own. And keep in mind that this is a man of the cultural right, where support for the military has typically been strong.

Now those are harsh feelings. But I do understand them.

Me too. More:

Sexual confusion isn’t unique to our age, but the scope of it is. No society can sustain itself for long if marriage and the family fall apart on a mass scale. And that’s exactly what’s happening as we gather here today. The Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision approving same-sex marriage last June was a legal disaster. But it didn’t happen in a vacuum. It fits very comfortably with trends in our culture that go back many decades, even before the 1960s. It’s useful to read or reread Wilhelm Reich’s book from 1936, The Sexual Revolution. Reich argues that a real revolution can only be made at the level of sexual freedom. And it needs to begin by wiping away institutions like marriage, family and traditional sexual morality.

What’s interesting about Reich’s work is that, 80 years ago, he saw the United States as the most promising place for that kind of revolution, despite its Puritan history. The reason is simple. Americans have a deep streak of individualism, a distrust of authority and a big appetite for self-invention. As religion loses its hold on people’s behavior, all of these instincts accelerate. The trouble is that once the genie is out of the bottle, sexual freedom goes in directions and takes on shapes that nobody imagined. And ultimately it leads to questions about who a person is and what it means to be human.

And:

There’s a lot of talk in Christian circles today about the need to protect believing families from a flawed culture that often seems to be getting worse. And the talk frequently turns to a thing called the “Benedict Option.” It’s an idea worth explaining. Benedict of Nursia was a sixth century Italian saint and the founder of Western monasticism. The son of a Roman nobleman, he left Rome as a young man for the peace of the countryside. He eventually founded 12 religious communities that grew into the worldwide Benedictine Order of monks we have today. So the core of a modern “Benedict Option” involves finding a way to preserve people from the most dysfunctional elements of the secular world—either by building new communities or withdrawing mentally, or even physically, from the public culture around us.

It’s a compelling idea. Critics don’t do it justice if they write it off as a form of escapism. But for me as a bishop—and I’ve heard this from many other believers—I think an even better model is St. Augustine, who led the fifth century Church in the North African city of Hippo Regius. Augustine lived and worked in the thick of his people. As a bishop, he engaged the problems of the society around him every day—even as the Roman world fell apart, and his own city came under siege.

I think we need to think and act in the same way Augustine did. Our task as believers, whatever our religious tradition, is to witness our love for God and for each other in the time and place God puts us. That means we have duties—first to the City of God, but also to the City of Man.

I appreciate the Archbishop’s kind words about the Ben Op. I know this won’t be clear to people until I publish the book, but I want to say that the Benedict Option is not really about actual, physical withdrawal (though it could entail that), but about learning how to live as orthodox Christians, resiliently, in an anti-Christian culture. Living as orthodox Christians has to mean caring for the common good; after all, the Lord told the captive Israelites, through the Prophet Jeremiah, to “pray for the peace of the city” — Babylon — because if the city prospers, so will they. This is what the Tipiloschi, a Ben Op community in Italy, do. But the Tipiloschi are keenly aware that the only way they can be of authentically Christian service to the wider community is by first deepening and strengthening their own particular community in its Catholic faith and practice.

To me, that is the Benedict Option at its best. I think it entails what Archbishop Chaput is talking about when he mentions Augustine. I chose “Benedict” for several reasons: 1) because I endorse Alasdair MacIntyre’s view of the roots of our crisis, and he said we are looking for a new, quite different St. Benedict; 2) because the Rule of St. Benedict is full of practical instructions for how to live and to thrive as a Christian community; and 3) because the fidelity of the Benedictines, over time, did serve those outside the monasteries, and ultimately laid the groundwork for the rebirth of civilization in western Europe.

Those early Benedictines are an example of what Pope Benedict XVI called a “creative minority.” Rabbi Jonathan Sacks devoted his 2013 Erasmus Lecture to the idea of creative minorities. Excerpts:

So you can be a minority, living in a country whose religion, culture, and legal system are not your own, and yet sustain your identity, live your faith, and contribute to the common good, exactly as Jeremiah said. It isn’t easy. It demands a complex finessing of identities. It involves a willingness to live in a state of cognitive dissonance. It isn’t for the fainthearted. But it is creative.

Fast forward twenty-six centuries from Jeremiah to May 13, 2004, to a lecture on the Christian roots of Europe by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, later to become Pope Benedict XVI. There he confronted the phenomenon of a deeply secularized Europe, more so perhaps than at any time since the conversion of Constantine in the third century.

That loss of faith, Ratzinger argued, had brought with it three other kinds of loss: a loss of European identity, a loss of moral foundations, and a loss of faith in posterity, evident in the falling birthrates that he described as “a strange lack of desire for the future.” The closest analogue to today’s Europe, he said, was the Roman Empire on the brink of its decline and fall. Though he did not use these words, he implied that when a civilization loses faith in God, it ultimately loses faith in itself.

More:

What if at least one creative minority had long ago seen what Toynbee and other historians would eventually realize? What if they had witnessed the decline and fall of the first great civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt, Assyria? What if they had seen how dominant minorities treat the masses, the proletariat, turning them into forced labor and conscripted armies so that rulers could be heroes in expansionist wars, immortalized in monumental buildings? What if they saw all of this as a profound insult to human dignity and a betrayal of the human condition?

What if they saw religion time and again enlisted to give heavenly sanction to purely human hierarchies? What if they knew that truth and power have nothing to do with one another and that you do not need to rule the world to bring truth into the world? What if they had realized that once you seek to create a universal state you have already begun down a road from which there is no escape, a process that ends in disintegration and decline? What if they were convinced that in the long run, the real battle is spiritual, not political or military, and that in this battle influence matters more than power?

What if they believed they had heard God calling on them to be a creative minority that never sought to become a dominant minority, that never sought to become a universal state, nor even in the conventional sense a universal church? What if they believed that God is universal but that love—all love, even God’s love—is irreducibly particular? What if they were convinced that the God who created biodiversity cares for human diversity? What if they had seen the great empires conquer smaller nations, and impose their culture on them, and had been profoundly disturbed by this, as we today are disturbed when an animal species is driven to extinction by human exploitation and carelessness?

What if these insights led a figure like Jeremiah to reconceptualize the entire phenomenon of defeat and exile? The Israelites had betrayed their mission by becoming obsessed with politics at the cost of moral and spiritual integrity. So taught all the prophets from Moses to Malachi. Every time you try to be like your neighbors, they said, you will be defeated by your neighbors. Every time you worship power, you will be defeated by power. Every time you seek to dominate, you will be dominated. For you, says God, are my witnesses to the world that there is nothing sacred about power or holy about empires and imperialism.

Read the whole thing. Christians of the small-o orthodox kind are now minorities in this country, and will increasingly be so. The American Empire, by which I mean the American idea, is falling. Maybe this is something to be mourned, maybe not. But it’s happening, and it’s happening largely because we have turned our back on the God of the Bible, and instead turned to the worship of Self, and power. Just as the Jews in Babylonian captivity could only serve themselves and the wider community by being faithful Jews (as opposed to assimilated ones), so too can orthodox Christians in our time only serve the West by being authentically and uncompromisingly Christian. Our assimilation into mass consumerism, individualism, and hedonism destroys that possibility. Destroys it.

I would say, then, that if we are going to be good Augustines, we first have to be good Benedicts: willing to turn inward in our thought and practices so that when we turn outward to the world, they will see the face of Christ instead of a mirror. There is no other realistic option. Not if you want your children and your children’s children to remain Christian.

Carnage In Belgium

Dozens murdered by terrorists in Brussels this morning. From the NYT:

Since the Paris attacks, security experts have warned that Europe was likely to face additional assaults by the Islamic State and by other terrorist groups. The Paris attacks showed that the scale and sophistication of the Islamic State’s efforts to carry out operations in Europe were greater than first believed, and analysts have also pointed to Europe’s particular vulnerabilities. They include the huge flow of undocumented migrants to the Continent from the Middle East last year, the movement of European citizens between their home countries and Syria to fight with the Islamic State, and persistent problems with intelligence sharing among European countries and even between competing security agencies in some nations.

Few countries have been more vulnerable than Belgium. It has an especially high proportion of citizens who have traveled to Iraq, insular Muslim communities that have helped shield jihadists, and security services that have had persistent problems conducting effective counterterrorism operations, not least in its four-month effort to capture Mr. Abdeslam.

If the Islamic terrorists can pull this off in the heart of a European capital that is already expecting something like this (as they must have been after the arrest of Abdeslam, is anywhere in Europe safe?

Good luck pressing on with that open door to Middle East refugee migration, Chancellor Merkel. The future belongs to leaders like Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban, who gave a powerful speech a week ago today, on Hungary’s national holiday. Here it is, with English subtitles; a bit of the transcript follows:

The main danger to Europe’s future does not come from those who want to come here, but from Brussels’ fanatical internationalism. [Note: By “Brussels,” he means the European Union. — RD] We should not allow Brussels to place itself above the law. We shall not allow it to force upon us the bitter fruit of its cosmopolitan immigration policy. We shall not import to Hungary crime, terrorism, homophobia and synagogue-burning anti-Semitism. There shall be no urban districts beyond the reach of the law, there shall be no mass disorder. No immigrant riots here, and there shall be no gangs hunting down our women and daughters. We shall not allow others to tell us whom we can let into our home and country, whom we will live alongside, and with whom we will share our country.

We know how these things go. First we allow them to tell us whom we must take in,

then they force us to serve foreigners in our own country. In the end we find ourselves being told to pack up and leave our own land.

Therefore we reject the forced resettlement scheme, and we shall tolerate neither blackmail, nor threats.

The time has come to ring the warning bell. The time has come for opposition and resistance.

The entire transcript can be read at Gates of Vienna.

To be clear, we don’t know whether the terrorists who did this were home-grown or came with the migrating masses. That’s not the point. The point is that Europe is already full of alienated, militant young Muslim men — and European leaders are importing more and more of them by the day. This is not going to end well for Europe. Hungary, it will be fine. [UPDATE: Let me revise that opinion in light of the fact that Hungary’s fertility rate is absolutely cratering. — RD]

UPDATE: From BuzzFeed News’s reporter in Belgium:

One Belgian counterterrorism official told BuzzFeed News last week that due to the small size of the Belgian government and the huge numbers of open investigations — into Belgian citizens suspected of either joining ISIS, being part of radical groups in Belgium, and the ongoing investigations into last November’s attacks in Paris, which appeared to be at least partially planned in Brussels and saw the participation of several Belgian citizens and residents — virtually every police detective and military intelligence officer in the country was focused on international jihadi investigations.

“We just don’t have the people to watch anything else and, frankly, we don’t have the infrastructure to properly investigate or monitor hundreds of individuals suspected of terror links, as well as pursue the hundreds of open files and investigations we have,” the official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the media, said.

“It’s literally an impossible situation and, honestly, it’s very grave.”

UPDATE.2: A reader in the UK writes:

Brace yourself for the familiar refrain from our dear leaders:

‘Shocked’ by these horrific, totally unexpected attacks

Je suis bruxellois

Islam is a Religion of Peace

Nothing to Do with Islam

Nothing to do with mass Islamic immigration

Racist to second-guess Frau Merkel’s policies

Only a tiny minority

Large peaceful majority expecting backlash from the Far Right

Special precautions to protect mosques, madrassas etc.

Further restrictions on ‘hate speech’ which causes these attacks

We are safer in the EU than out

Diversity is strength

War is peace

Freedom is slavery

UPDATE.2: Reader Kurt Gayle sends a link to the complete transcript of Orban’s speech.

Wipeout —Then a Reformed GOP?

Joel Kotkin bids farewell to the Republican Party. Excerpts:

Against weak and squabbling opposition, Trump has employed his crude persona, and equally crude politics, to dominate the primaries to date. But in the process he has broken not only the party structure, but also its spirit. Indeed, some of the party’s most promising emerging leaders, such as Nebraska U.S. Sen. Ben Sasse, have made it clear they cannot support a candidate who seems to have little respect for the Constitution, or any other cherished principle.

In contrast, the Democrats, for all their manifest divisions, remain united by a desire to reward and parcel out goodies to their various constituencies. Hillary Clinton, as the troublesome Bernie Sanders fades, will gather a Mafia-like commission of Democratic “families” – feminists, greens, urban land speculators, public unions, gays, tech oligarchs and Wall Street moguls. Given the self-interest that binds them, few Democrats will reject her, despite her huge ethical lapses and appearance of congenital lying.

Kotkin blames economic elites for driving the GOP off the cliff:

Those most responsible for the party’s decline, however, are those with the most to lose: the Wall Street-corporate wing of the party. These affluent Republicans placed their bets initially on Jeb Bush, clear proof of their cluelessness about the grass roots – or much else about contemporary politics. They used to attract working- and middle-class voters by appealing somewhat cynically to patriotism and conservative social mores, which also did not threaten their property and place in the economic hierarchy. Now these voters no longer accept “trickle down” economics or the espousal of free trade and open borders widely embraced by the establishments of both parties.

The fecklessness of the party leadership has been evident in the positions taken by corporate Republicans. Reduce capital-gains taxes to zero? Are you kidding, Marco? New trade pacts may thrill those at the country club, but not in towns where industries have fled to Mexico or China.

And then there’s immigration.

It didn’t have to be this way, but the mandarins couldn’t see what was happening to them, and reform themselves. Kotkin is not a Trumpkin (“The election of Trump would elevate an unscrupulous, amoral and patently ignorant bully to the White House”), and he believes that though Trump will draw some blue-collar white Democratic vote away from Hillary, she will win — and Democrats may well win the Senate, too

… leaving Clinton a clear path to dominate the Supreme Court. This will strip away the only barrier to ever more intrusive rule by decree. Clinton has already made it clear that, unlike her husband, she is ready to circumvent Congress if it dares decline her initiatives.

In this way, the rest of the country will increasingly resemble what we already have in California – a central governing bureaucracy that feels little constrained about expanding its power over every local planning and zoning decision. The federal republic will become increasingly nationalized, dispensing largely with the constitutional division of power.

Centralism, as known well in California, comes naturally to a one-party state. Businesses, particularly large ones, faced with uncontested political power, will fall in line.

Read the whole thing. Lots to chew on there. Kotkin says that if the GOP loses the White House for the third time in a row, it will be shattered. The only hope for conservatives is that the country will be so fed up with Hillary overreach after four years that it will elect a decentralizing president and Congress in 2020.

Hey, you take hope where you can find it. And for religious conservatives like me, a Hillary victory would be a catastrophe. She is fully on board with pro-abortion feminism. Remember when she gave the speech last year saying that religious beliefs worldwide had to be changed to make abortion more widely available? And her going all-in for the LGBT agenda means she would be an unmitigated disaster for religious liberty. She has already endorsed the Equality Act. Andrew T. Walker explains what that means for dissenting religious institutions, like colleges:

The reality or effect of the Equality Act would be to cudgel dissenting institutions whose views on heavily disputed categories, such as sexual orientation and gender identity, do not line up with government orthodoxy. In effect, if an institution takes sexual orientation or gender identity into account, it is seen as violating federal non-discrimination law. The conflict this poses for religious institutions that do not agree with the morality of LGBT ideology, which would be protected in federal law, is enormous.

The conflict is reflected in the now-infamous exchange heard in the Obergefell oral arguments:

Justice Alito: Well, in the Bob Jones case, the Court held that a college was not entitled to taxexempt status if it opposed interracial marriage or interracial dating. So would the same apply to a university or a college if it opposed same-sex marriage?

[Solicitor] General Verrilli: You know, I don’t think I can answer that question without knowing more specifics, but it’s certainly going to be an issue. I don’t deny that. I don’t deny that, Justice Alito. It is — it is going to be an issue.

“It is going to be an issue.” Never has a government lawyer been so forthcoming.

Consider this: Scalia is gone, and his seat will be filled either by Obama this year, or Hillary, if she wins. Either way, a Democrat. Ruth Bader Ginsburg is 83 and in poor health. She is likely to retire or expire in the next president’s term. Justice Kennedy is the second-oldest justice, at 79. It would not necessarily be a loss to religious liberty and other causes dear to social conservatives, but it would give President HRC an opportunity to appoint a younger liberal to sit on the court for decades. Justice Breyer is 77, and if he so pleased, could retire knowing that a Democratic president would replace him with a liberal.

And if Hillary gets a Democratic Senate, she’ll be able to name whoever she wants to the Supreme Court. If Ginsburg, Kennedy, and Breyer leave the court, she could lock in a solid 6-3 liberal majority for a very long time.

Get your Benedict Option plans ready, folks.

Wipeout — Then A Reformed GOP?

Joel Kotkin bids farewell to the Republican Party. Excerpts:

Against weak and squabbling opposition, Trump has employed his crude persona, and equally crude politics, to dominate the primaries to date. But in the process he has broken not only the party structure, but also its spirit. Indeed, some of the party’s most promising emerging leaders, such as Nebraska U.S. Sen. Ben Sasse, have made it clear they cannot support a candidate who seems to have little respect for the Constitution, or any other cherished principle.

In contrast, the Democrats, for all their manifest divisions, remain united by a desire to reward and parcel out goodies to their various constituencies. Hillary Clinton, as the troublesome Bernie Sanders fades, will gather a Mafia-like commission of Democratic “families” – feminists, greens, urban land speculators, public unions, gays, tech oligarchs and Wall Street moguls. Given the self-interest that binds them, few Democrats will reject her, despite her huge ethical lapses and appearance of congenital lying.

Kotkin blames economic elites for driving the GOP off the cliff:

Those most responsible for the party’s decline, however, are those with the most to lose: the Wall Street-corporate wing of the party. These affluent Republicans placed their bets initially on Jeb Bush, clear proof of their cluelessness about the grass roots – or much else about contemporary politics. They used to attract working- and middle-class voters by appealing somewhat cynically to patriotism and conservative social mores, which also did not threaten their property and place in the economic hierarchy. Now these voters no longer accept “trickle down” economics or the espousal of free trade and open borders widely embraced by the establishments of both parties.

The fecklessness of the party leadership has been evident in the positions taken by corporate Republicans. Reduce capital-gains taxes to zero? Are you kidding, Marco? New trade pacts may thrill those at the country club, but not in towns where industries have fled to Mexico or China.

And then there’s immigration.

It didn’t have to be this way, but the mandarins couldn’t see what was happening to them, and reform themselves. Kotkin is not a Trumpkin (“The election of Trump would elevate an unscrupulous, amoral and patently ignorant bully to the White House”), and he believes that though Trump will draw some blue-collar white Democratic vote away from Hillary, she will win — and Democrats may well win the Senate, too

… leaving Clinton a clear path to dominate the Supreme Court. This will strip away the only barrier to ever more intrusive rule by decree. Clinton has already made it clear that, unlike her husband, she is ready to circumvent Congress if it dares decline her initiatives.

In this way, the rest of the country will increasingly resemble what we already have in California – a central governing bureaucracy that feels little constrained about expanding its power over every local planning and zoning decision. The federal republic will become increasingly nationalized, dispensing largely with the constitutional division of power.

Centralism, as known well in California, comes naturally to a one-party state. Businesses, particularly large ones, faced with uncontested political power, will fall in line.

Read the whole thing. Lots to chew on there. Kotkin says that if the GOP loses the White House for the third time in a row, it will be shattered. The only hope for conservatives is that the country will be so fed up with Hillary overreach after four years that it will elect a decentralizing president and Congress in 2020.

Hey, you take hope where you can find it. And for religious conservatives like me, a Hillary victory would be a catastrophe. She is fully on board with pro-abortion feminism. Remember when she gave the speech last year saying that religious beliefs worldwide had to be changed to make abortion more widely available? And her going all-in for the LGBT agenda means she would be an unmitigated disaster for religious liberty. She has already endorsed the Equality Act. Andrew T. Walker explains what that means for dissenting religious institutions, like colleges:

The reality or effect of the Equality Act would be to cudgel dissenting institutions whose views on heavily disputed categories, such as sexual orientation and gender identity, do not line up with government orthodoxy. In effect, if an institution takes sexual orientation or gender identity into account, it is seen as violating federal non-discrimination law. The conflict this poses for religious institutions that do not agree with the morality of LGBT ideology, which would be protected in federal law, is enormous.

The conflict is reflected in the now-infamous exchange heard in the Obergefell oral arguments:

Justice Alito: Well, in the Bob Jones case, the Court held that a college was not entitled to taxexempt status if it opposed interracial marriage or interracial dating. So would the same apply to a university or a college if it opposed same-sex marriage?

[Solicitor] General Verrilli: You know, I don’t think I can answer that question without knowing more specifics, but it’s certainly going to be an issue. I don’t deny that. I don’t deny that, Justice Alito. It is — it is going to be an issue.

“It is going to be an issue.” Never has a government lawyer been so forthcoming.

Consider this: Scalia is gone, and his seat will be filled either by Obama this year, or Hillary, if she wins. Either way, a Democrat. Ruth Bader Ginsburg is 83 and in poor health. She is likely to retire or expire in the next president’s term. Justice Kennedy is the second-oldest justice, at 79. It would not necessarily be a loss to religious liberty and other causes dear to social conservatives, but it would give President HRC an opportunity to appoint a younger liberal to sit on the court for decades. Justice Breyer is 77, and if he so pleased, could retire knowing that a Democratic president would replace him with a liberal.

And if Hillary gets a Democratic Senate, she’ll be able to name whoever she wants to the Supreme Court. If Ginsburg, Kennedy, and Breyer leave the court, she could lock in a solid 6-3 liberal majority for a very long time.

Get your Benedict Option plans ready, folks.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 509 followers