Rod Dreher's Blog, page 596

April 7, 2016

View From Your Table

Lake Louise, Alberta, Canada

Isn’t that something, that view? That beer belongs to Peter Leithart, who was sitting to the left of the frame. I was drinking the same kind. What a gorgeous, gorgeous place. A group of us went walking in Johnson Canyon, part of Banff National Park, in the Canadian Rockies. Then we dropped by to see Lake Louise, which is still frozen over. We had a beer at the hotel on the lake.

I apologize for being away from the keys all day. I thought I would get some work done this afternoon, but we were in the mountains. I leave on a 6 am flight from Calgary in the morning, ultimately headed to Bozeman, Montana. Somehow, I went into the woods here in the Great White North without being molested by a Sasquatch. I hope I have similar luck in Montana.

Man, did I ever have a great time with these Lutherans up here!

April 6, 2016

The World Through SJW Eyes

This is too, too good. This happened at the University of Indiana at Bloomington:

Rumors of a klansman on campus have proven false after a priest innocently made his way through Bloomington.

Last night around 9:15 PM, social media became a furious storm of confusion regarding a man in white robes roaming along 10th St. and purportedly armed with a whip.

Students thought the white robes indicated Klu [sic] Klux Klan affiliation.

You have to go to the story to see the social media freakout. Here’s a post that one nitwit put on Twitter:

iu students be careful, there's someone walking around in kkk gear with a whip.

— sanchez (@babyynini_) April 5, 2016

It turns out the Klansman with a whip was a white-robed Dominican priest with a rosary on his belt. “Sanchez” wasn’t the only student who went nuts. But when she was called on it, she was unapologetic:

the priest mistaken for kkk didn't start with me simply warned my peers about a warning that was going around campus pic.twitter.com/cRTm6yCY45

— sanchez (@babyynini_) April 6, 2016

She continued on, being proud of her ignorance. Her Twitter feed indicates a rich inner life. But she’s right: this was a typical SJW campus meltdown. Read the story from The Tab, the Bloomington publication that broke it. And here is a photo of a Klansman with a whip white-robed Dominican with rosary meeting the Dalai Lama.

Oh Social Justice Warriors, don’t ever change…

View From Your Table

Social Media Vs. Girls

In the 2 1/2 years she spent researching her book, Sales interviewed more than 200 teenage girls around the country about their social media and Internet usage. She says girls face enormous pressures to post “hot” or sexualized photos of themselves online, and she adds that this pressure can make the Internet an unwelcoming environment.

“I think a lot of people are not aware of how the atmosphere has really changed in social situations … in terms of how the girls are treated and how the boys behave,” Sales says. “This is a kind of sexism and misogyny being played out in real time in this really extreme way.”

More:

On how males’ and females’ pictures differ on Tinder

I talked to an 18-year-old girl who is talking about looking at Tinder with her older brother and … she said she was struck by the way in which the boys and men’s pictures were very different than the girls’. Guys tend to have a picture like, I don’t know, they’re standing on a mountain looking like they’ve climbed the mountain, or they’re holding a big fish or they’re doing something manly, or in their car. … But the girls’ pictures … tend to be very different; they tend to be a lot more sexualized.

This is a pressure on social media that goes back, for women and girls, a long time. … I trace the origins back to a site called “Hot or Not” which came out in 2000. … The whole idea of “hotness” has become such a factor in the lives of American girls, unfortunately, because according to many, many studies, including a really landmark report by the American Psychological Association in 2007, this has wide-ranging ramifications for girls’ health and well-being, including studies that link this pressure to sexualize on all kinds of things like rising anxiety, depression, cutting, eating disorders. It’s a thing that I don’t think that boys have to deal with as much.

More:

On boys asking girls for nude photos

I think the fact that so often we’re talking about nudes and sexting is because kids are watching porn. There’s multiple studies that say that they are. We know that they are. They’re curious. They’re going through puberty. They’re watching porn. And yet, nobody really talks about it or talks about the fact that it has an effect on how they behave and what they think about sex and sexuality and how they deal with each other. And there’s really no guidelines for girls about how to react to all of this. …

Some 13-year-old girls in Florida and New Jersey both told me that if they didn’t [send photos] they had been threatened with boys sending rumors about them, sending around a picture that actually wasn’t them and saying it was them. I mean, there’s a kind of thing in adult life that we know about called revenge porn, and that happens among kids as well, unfortunately.

It’s very risky for girls to send nudes because when they do, if they chose to, those photos are not private. They can be shared and very often they are shared. I heard story after story of situations where girls had pictures of themselves sent around to groups of people. It has become such a normal thing to them.

Read — or listen — to the whole thing.

Sales goes on to say that online pornographers have determined that the more extreme the sexual act, the more clicks they generate. And now, extremely perverse acts (which thankfully she didn’t describe) are appearing in teenage sexuality.

There was a famous (infamous?) scene in “Hardcore,” a 1979 movie in which George C. Scott plays a Midwestern father who discovers that his teenage daughter has left home and has begun making pornographic films. He watches a stag film in which his daughter on the screen doing filthy things, and screams.

You don’t have to go to an X-rated movie theater to see this stuff now, apparently. You just have to look at the smartphones of boys in town. As the secularist crank James Howard Kunstler likes to say in other contexts: We are a wicked people who deserve to be judged.

By the way, if you missed it last November, read the part of the “This American Life” episode transcript in which young teenage girls talk about how managing their brand on social media has become an all-consuming thing for them in their social world. Madness. Feel like that if I have to throw myself in front of a train to save my daughter from all of this garbage, I will.

The Price Of Purity

A reader writes:

I am 100 percent on board with your indictment of technology for kids. How does a family, however, handle the isolation and loneliness that comes with being “disconnected” from others? My husband and I have flip phones and our four teenagers still have no phones (we homeschool). My husband runs a proxy server at our house and only allows the kids to access a very few select websites on computers mounted to the wall in our family room. He and I use a filter on our password protected computers, but a lot of junk still gets through that we would prefer they not see.

The few people who still bother with us think we are nuts. We are social outcasts, and I really think it has to do with the technology thing. One by one, we have seen good families cave in and get iPads and smart phones for their kids. When we mention the serious problems with this, we get blank stares or they politely change the subject and soon distance themselves from us.

I continuously weigh the social isolation against my kids’ purity and feel we are paying a very heavy price for virtue. Sometimes I don’t know how long we can hold out. My husband was one of a small group of Catholic men who saw this problem brewing on the horizon in the early 1990s and started a small Internet filtering company in 1997. He heard so many sad stories of families destroyed by porn even back then.

This gets to me, and reminds me of the desperate need we have for community. But it has to be a community where all the parents are united in their policy towards smartphones and the Internet. A community is not really a community if it cannot say “thou shalt not” and enforce its standards. I think the overwhelming majority of parents would rather pretend that this is not an issue, because if it is an issue, then the work they would have to do even to begin to address it is too hard.

I’m not saying this from a high-and-mighty position. I’m in this struggle too, raising kids. Advice?

Your Job Or Your Faith

Elliot Milco writes, about the Catholic Church in the present day:

There was a hope in the 1960s that the integrity of secular liberalism and its humanitarian values would dovetail with the mandates of the Gospel, making Church and State partners in the advancement of the material and spiritual welfare of mankind. Unfortunately, secular liberalism has continued on its own path. Far from becoming the friend to the Gospel envisioned by the Council Fathers at Vatican II, the modern liberal state has become host to a welter of nihilistic materialism and utilitarianism. As the liberal state moves further away from the Church, the balance between political secularism and free exercise shifts further and further toward the former, and the friendship once hoped for is replaced by hostility and oppression. Already there are a number of professions that cannot be occupied by Catholics in America. That number is increasing, and will continue to increase, as the state blesses the exclusion of Catholics from one area of public life after another.

In the present moment, that distinctively American Catholicism so lionized after Vatican II seems to have failed. For us, as American Catholics, this is rather embarrassing. With the pax between Church and State reaching its end, we need to re-think our political engagements and re-examine the foundations of the compromise, in order to better grasp the range of alternatives before us.

And so, the Benedict Option conversation spreads.

Yesterday I was talking to a Canadian pastor whose son is thinking about becoming a doctor. The pastor said that the Canadian Supreme Court declared that euthanasia is a right, and ordered the government to come up with a right-to-die law by this June. The final legislation is not expected to contain a conscience clause for doctors, Christian and otherwise, who want nothing to do with this form of killing. Wesley J. Smith writes:

Doctors aren’t the only ones threatened with religious persecution under Canada’s looming euthanasia regime. Provincial and federal commissions have both recommended that nurses, physician’s assistants, and other such licensed medical practitioners be allowed to do the actual euthanizing under the direction of a doctor.

This is particularly worrying from a medical conscience perspective, because it leaves no wiggle room to say no. For example, objecting doctors might be able to defend their refusals by claiming that the euthanasia requester is not legally qualified. Nurses, however, would not even have that slim hope, since they would merely be delegated the dirty task of carrying out the homicide. This leaves nurses with religious objections to euthanasia with the stark choice of administering the lethal dose when directed by a doctor, or being insubordinate and facing job termination. The same conundrum would no doubt apply to religiously dissenting pharmacists when ordered to concoct a deadly brew.

Even Catholic and other religious nursing homes and hospices may soon be required by law to permit euthanasia on their premises, for the federal commission recommended that federal and provincial governments “ensure that all publicly funded health care institutions provide medical assistance in dying.” That is a very broad category. Canada has a single-payer, socialized healthcare financing system that permits little private-pay medical care outside of nursing homes. Not only that, but as Alex Schadenberg, director of the Canada-based Euthanasia Prevention Coalition told me, “religiously-affiliated institutions [in Canada] have become the primary care facilities for elderly persons, those requiring psychiatric care, and dying persons. They are now being told that as a condition of providing those services they will be required to permit doctors to kill these very patients by lethal injection. If they refuse, they will find themselves in a showdown with the government.”

So what do you do, if you are a Canadian doctor, nurse, or other medical professional, who cannot allow yourself to be complicit in what you regard as a form of murder? You refuse, and go to jail. You quit your job and find another line of work. Or you emigrate to a country where you will be protected (for now, the US offers these protections).

All those outs require paying a massive personal cost. But this is what it means to live in a post-Christian society.

We Americans had better start having these Benedict Option conversations. What will you do when you are driven out of your profession, or, in some other way, the public square, because of your faith? For Canadian doctors, it’s very soon not going to be an abstract or alarmist question.

A reader wrote the other day, commenting on this passage from the most recent Prof. Kingsfield missive (the quote below is from Kingsfield):

We have to stop caring about what the world and the media think. They will call us bigoted no matter how loving, winsome, and fair-minded we are–see the actual Ryan Anderson vs the caricature of him, or the actual Doug Laycock vs. the activists’ efforts to subpoena his email and phone records. We have to figure out how not to care. And that will require far more withdrawal from mainstream media than most people can stomach.

The reader writes:

It is also hard, however, to separate this out from basic job security. I don’t care if I am liked. I do care if I can’t keep working at my company anymore because I am considered a toxic bigot. We are going to have to pray for prudence and shrewdness.

I have had further conversations with this reader about the nature of his work. In his company, to simply be known as someone who opposes same-sex marriage is to push hard against the margins of tolerance. The fact that he is an orthodox Christian on this issue marks him, even if he never says a word about homosexuality. He gave me some examples of what happened to another person in the company over this. I’m not going to talk about it, for the sake of privacy, but this reader is not exaggerating, at all.

Porn: A Virus Emasculating Men

A young Muslim reader who blogs under the name Jones had a fascinating comment in yesterday’s thread about the porn calamity:

That’s the tip of the iceberg, honestly. It’s interesting, it’s very unlikely that you’re going to get an open and truthful discussion of these issues because they have to do with sex, and for all of our supposed enlightenment it’s still a taboo subject. Surprise! Maybe we should just crank up the knobs of social reeducation further? The reason it’s taboo is that it affects our interests, desires, and identities too closely, that it really is incompatible with civilization as we try to live it, even according to this fairly degenerate understanding of “civilization.” So even when “sex” comes into the public sphere, it comes in according to pre-digested notions of what is appropriate, some unholy melange of third-wave sex positivism and public health.

The problem is not just pornography; it’s also a pornogrified culture. The rest of pop culture, and girls themselves, are increasingly aware of themselves as competing with pornography for male attention.

Just an example pulled at random from the recent news: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/24/fashion/raiding-the-sex-shop-for-the-latest-fashion.html

The author writes, critically: “The big question is whether or not porn use is a “public health crisis.” In other words, the main problem with porn is not moral or spiritual but that it keeps men from fornicating with lots of women.”

I actually think that the moral/spiritual problem is the least of it. It’s so much worse than that. Expanding on his critique, he writes, of porn: “It has actually delivered to us a generation of men who think of women as objects to be used and abused for their sexual pleasure. It has not given us men who know what virtue and honor are. It doesn’t teach men to pursue their joy in self-sacrificially loving and being sexually faithful to one woman for life.”

That’s all true, but it’s pretty old hat. I can sort of imagine a society straggling along in a state of protracted decadence. To believe that something is immoral, you don’t have to believe that it’s functionally destructive, or biologically maladaptive. You can morally condemn a perfectly stable state of affairs. But it’s so much worse than that.

I have to admit I think that Christian conservative thinking on sex and gender relations is pretty weak at this point. It’s just too far removed from reality; it’s not remotely keeping up with actual conditions. I recently looked up some of the Christian advice on the internet for men trying and struggling to remain chaste until marriage. I mean, the advice was horrendous. If I was a man, I would spit it back out immediately.

The problem seems to be the same across the board, for conservatives and liberals alike: no one has any understanding or ideal of masculinity. No one has any conception of what masculine interests are, how they connect to responsibilities, or what the appropriate give-and-take between men and society should be. “Men” hardly exist as a category–they’re basically being written out of our conceptual vocabulary. Conservatives and liberals alike are steeped in ignorance and confusion on this subject. The consequences are vast: school shootings, terrorism, the breakdown of the family, all of these things intersect with the demise of masculinity in some way. A lot of behavior that our society currently deems “irrational” and inexplicable suddenly becomes sensible when you have some functional understanding of masculinity.

A classic example is the fact that conservatives like Burk, when they lament porn, usually do so by remarking on how it leads to the objectification of women, may contribute to sexual violence, etc. The main concern, which conservatives and liberals shared, seemed to be that men would watch porn and go out to commit sex crimes, or something.

But the actual problem is more like the opposite, and is much worse. Porn actually leads to what you could call a dissociated sexuality. The problem is that it disconnects a man from the world, by misdirecting his sexual energies. This ultimately leads to a lack of interest in the real world, an inability to be motivated by it. How many young men do you know who seem disaffected, unmotivated, apathetic, aimless, irritable? Yeah, it’s porn. In every single case. This is a subtle but incredibly consequential effect, especially across an entire society.

Does it sometimes seem to you like our civilization is drifting and rudderless? Like our focus, our energy, our sense of purpose has disappeared? This is what happens when you lose your men — rather, when your men lose their manhood. Above all, porn is emasculation.

The drive for sex, above all in men, is one of the most fundamental and powerful drives present in mankind. Most of the work of civilization consists of controlling this drive and aiming it in socially productive directions (Freud). We used to have some institutions that did that: marriage, along with the concomitant prohibition on premarital sex. (One is completely pointless without the other.) This gave society some say in where a man’s most basic desires would lead him. That is all no more.

I’m not some sort of special enthusiast of masculinity. But I feel compelled to try to understand it, because no one else seems to.

April 5, 2016

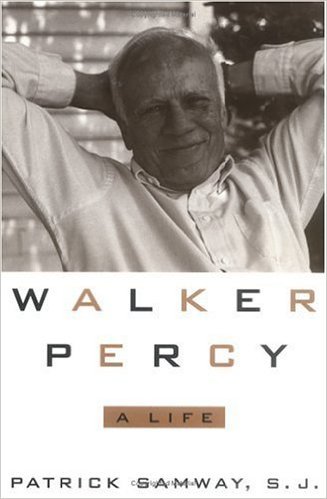

Patrick Samway To Walker Percy Weekend

News from Walker Percy Weekend: We’ve just added two excellent panelists to the Walker Percy & Catholicism discussion, hosted by Jason Berry.

News from Walker Percy Weekend: We’ve just added two excellent panelists to the Walker Percy & Catholicism discussion, hosted by Jason Berry.

Panelist Patrick Samway, SJ, wrote Percy’s authorized biography. Here is an excerpt from Chapter One. And here is an excerpt from Robert Coles’s review in The New York Times:

By setting clear limits on his authorial role, by attempting to evoke through letters and interviews and a weighty factuality the various worlds Walker Percy inhabited, Father Samway brings his narrative to full life. We meet an American original: his voice at once skeptical and innocent, earnestly hopeful and yearning, but also cranky and gloomy — a worried, doubtful pilgrim who had an exquisitely inviting way with irony and a genuine modesty, even as he rarely missed taking the witty or mordantly satirical measure of our follies. Above all, as this portrait keeps revealing, he practiced what he preached, his own self-critical apprehensions in that regard notwithstanding — no small victory for a Christian moralist who also happened to be a lively storyteller. He (and his two brothers as well) broke free of the past; lived long, committed, loving lives as husbands, fathers and grandfathers — an achievement for them, for any of us.

You will get to meet Father Samway if you come to town. Get him to sign your copy of his book. Hear him tell stories about Walker and the faith.

Our second panelist is Dr. Phillip Thompson, executive director of the Aquinas Center for Theology at Emory University. He wrote us to say that Percy’s writing changed his life. We asked him to come talk about Percy and the faith. Given Dr. Thompson’s background in science, technology and religion, and given how much that interested Percy, I’m hoping he will get into that on the panel.

Look, you’ve just got to come to this event. First weekend of June (3-5). It’s so much fun. Here’s the Walker Percy Weekend website, on which you can buy tickets. Remember, we only have a limited number of tickets, and all the good B&Bs and hotel rooms will be sold out if you wait too long.

Alberta, Mon Amour

Hey, I’m in the Canadian Rockies tonight, drinking beer with Lutherans. I love me some Canadian Lutherans. They’re the good kind, the ones who actually believe. Talking to some after I got here, I am all filled in on the ridiculous situation orthodox Christians are facing in Canada, thanks to the March Of Progress. I heard good things about Calgary’s Catholic bishop, Fred Henry, who, I am told, is no friend of progressives. “He tells them to go pound sand,” said one Lutheran pastor, appreciatively.

On the long flight up from Houston, I transcribed more of my interviews with the Norcia monks, and was once again excited about the Benedict Option book (it has been a long slog through bronchial infection and the Enlightenment). I can’t wait to commit their words to the printed page. I’m going to be sharing some of what they said tomorrow with the audience here. I’ve got to tell you, this stuff is plain Christianity, but solid gold. Just you wait. Encountering their words again made me want to be back in Norcia for another week, just listening and being with them.

Unfortunately for me, I was waiting for compline tonight, and suddenly BOOM, the fact that I got up at five a.m. to drive to the New Orleans airport caught up with me all at once. I made my excuses, then retired to my room. More tomorrow. Did I tell you how much I like this crowd of Canadian Lutherans?

Death Of White Working-Class Culture

A reader sends in this op-ed from a teacher, writing in The Guardian about the death of white working-class culture for British kids. The author, a white man, was raised working class, and focuses on a new think tank report showing that white working-class youth are at the bottom of the barrel when it comes to educational achievement. The writer blames Thatcherism for breaking the unions in the 1980s. Excerpts:

It is simply that a specific part of their [white working class] culture has been destroyed. A culture based on work, rising wages, strict unspoken rules against disorder, obligatory collaboration and mutual aid. It all had to go, and the means of destroying it was the long-term unemployment millions of people had to suffer in the 1980s.

Thatcherite culture celebrated the chancers and the semi-crooks: people who had been shunned in the solidaristic working-class towns became the economic heroes of the new model – the security-firm operators, the contract-cleaning slave drivers; the outright hoodlums operating in plain sight as the cops concentrated on breaking strikes.

We thought we could ride the punches. But the great discovery of the modern right was that you only have to do this once. Suppress paternalism and solidarity for one generation and you create multigenerational ignorance and poverty. Convert Labour to the idea that wealth will trickle down, and to attacks on the undeserving poor, and you remove the means even to acknowledge the problem, let alone solve it.

More:

Thatcherism didn’t just crush unions: alone that would not have been enough to produce this spectacular mismatch between aspiration and delivery in the education system. It crushed a story.

And what the most successful Chinese, Indian and white Irish children probably have – although you would need more research than offered here to give this assertion rigour – is a clear and compelling story.

In my first week at university, myself and a few other working-class kids on our course were quizzed by our middle-class peers: “You must be exceptionally bright to get here, against these odds,” was the theme. We were incredulous. We had been headed for university since we picked up Ladybird books. Without solidarity and knowledge, we are just scum, is the lesson trade unionism and social democracy taught the working-class kids of the 1960s; and Methodism and Catholicism taught the same.

To put right the injustice revealed by the CentreForum report requires us to put aside racist fantasies about “preferential treatment” for ethnic minorities; if their kids are preferentially treated, it is by their parents and their communities – who arm them with narratives and skills for overcoming economic disadvantage.

If these metrics are right, the present school system is failing to boost social mobility among white working-class kids. But educational reforms alone will barely scratch the surface. We have to find a form of economics that – without nostalgia or racism – allows the working population to define, once again, its own values, its own aspirations, its own story.

I am not in a position to comment knowledgeably on the writer’s pinning this on Thatcherism. The trade unions had brought Britain to an economic standstill by the late 1970s, and that’s the kind of thing Thatcher was elected to stop. I find it hard to believe that all would be well if Britain had been governed by Old Labour instead of the Tories during the 1980s, or New Labour in the 1990s. But I’m willing to hear that case.

That said, just as in this country the Trump campaign has forced many of us to reconsider the destructive social effects of free trade deals — so popular with Republicans and Clinton Democrats — on the white working class in the US, it’s worth considering the social effect of neoliberal economics on the British white working class. Whatever the validity of this left-wing author’s take on Thatcherism, I’m less interested in that than in his contention that the white working class lost a narrative that gave them pride and helped them make sense of their lives in a constructive way. Economic liberals tend to say that there’s nothing wrong with the working class (of whatever race) that high-paying jobs wouldn’t fix. Maybe. But how do you give a “tribe” back its story, its myth?

You know what this sounds like? Native Americans, their worldview shattered by being conquered by alien Euro-American culture, sinking into chronic despair.

(Readers, please be patient with my approving comments today. I’m traveling to the Canadian Rockies to hang out with Lutheran pastors for the week, and talk Benedict Option.)

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 509 followers