Theodora Goss's Blog, page 57

June 11, 2011

The Second Frustrating Day

Yesterday was the second frustrating day.

In the morning, I took my laptop into the Information Technology center at Boston University. I was told to call at the end of the day to see if it needed to stay over the weekend. Just to take the suspense out of this blog post: it did. This weekend, I do not have a laptop. That's not quite correct, because after all, here I am typing this post. I have my old, very old, laptop. The one I had before I bought the new one. Technology changes so quickly. A laptop that I used for years, and that was the best I could find at the time, now seems slow and clunky. It's difficult to type on.

Which makes me think of two things. The first is the extent to which I depend on technology that is easy to use. My laptop, where everything is configured for me, where I can move around the internet with the fewest possible clicks, going from my website to facebook to twitter without having to input passwords. It's almost as easy, for me, as writing on paper with a pen. My cell phone, which allows me to be in constant touch with the world, even in airports. When something breaks down, it feels as though I have been displaced, as though a part of me is in the wrong place. Donna Harraway is right: we are all becoming cyborgs. Or at least I am. I can live without my tech. But I can't live with tech that malfunctions.

And my life requires things to work. It's a life in which things happen quickly, in which I need to turn documents around. Not having the ability to do that is so frustrating.

The second thing I thought about was how I deal with that sort of frustration. What did I actually do to deal with it?

First, I cleaned and mended. No, seriously. I cleaned my closet, and I mended three skirts and one sweater. On one skirt, I needed to secure the hook and eye more firmly. On the second, I needed to sew up some tears near the zipper. The third was a skirt with seven tiers, each using more fabric than the last, so that it flares around my calves. On those sorts of skirts, the places where the tiers are sewn together are not always strong, and the thread can break. So I sewed the places where the tiers had come apart. And the sweater had a run, which I secured and sewed over. So, in a small way, I put things that had come apart, back together. And in my closet, I put a set of low shelves on which I could fold all my sweaters. It's now much neater. And there is finally room for all the shoes. Although honestly, most women would probably laugh to see how few clothes I have, how few shoes. Everything fits into one closet, one dresser. Which is all a part of traveling lightly.

Second, I read. Specifically Joan Aiken's Armitage family stories. The book I was reading is called The Serial Garden: The Complete Armitage Family Stories. It's published by Small Beer Press, and you can buy it from Small Beer Press here and from Amazon here. The wonderful thing about these stories is that there's no interference. What I mean is, I never find myself thinking, that could be been put in a better, clearer way. Aiken's prose is exactly what it should be: clear, lucid, precise. The sort of prose I would very much like to write myself. The sort I'm trying to write.

It's a story about a family that has magical adventures that, to them, are perfectly ordinary. The first chapter begins,

"Monday was the day on which unusually things were allowed, and even expected to happen at the Armitage house.

"It was on a Monday, for instance, that two knights of the Round Table came and had a combat on the lawn, because they insisted that nowhere else was flat enough. And on another Monday two albatrosses nested on the roof, laid three eggs, knocked off most of the tiles, and then deserted the nest; Agnes, the cook, made the eggs into an omelet but it tasted too strongly of fish to be considered a success. And on another Monday, all the potatoes in a sack in the larder turned into the most beautiful Venetian glass apples, and Mrs. Epis,who came in two days a week to help with the cleaning, sold them to a rag-and-bone man for a shilling."

And so on. Interestingly, typing those lines, I can see how Aiken's prose must have influenced Kelly Link, because for some reason that description reminds me of Kelly's "The Fairy Handbag."

Third, I danced. Sort of, not actual dancing but the dance and yoga and pilades moves I put together into my exercise routine. I put on S.J. Tucker's Blessings. And then, I moved: bending and twisting and lifting, making sure all the muscles were stretched and strengthened, going from downward dogs to pushups and back again, from roll-ups and rollovers to shoulder stands. Just trying to get the tension out.

It's difficult not to dance when you have music like this:

[image error]

Or this:

This is going to be a frustrating weekend. I want Monday to come already. Until then, I'm going to keep cleaning, mending, reading, dancing. What else is there to do, in the face of frustration?

June 9, 2011

The Frustrating Day

It's been a frustrating day.

I was in the middle of printing out the comments on my dissertation chapters – the comments on the revised versions that I need to respond to in the next set of revisions, when my computer told me it had a virus. So I had to shut it down. (First I had a virus and now, just when I've mostly stopped coughing, my computer has one.)

What could I do? Everything I needed to work on was on the computer. Except the YA novel, so I sat down with pen and paper to write the third chapter. So far I have two chapters typed, one chapter handwritten. I'm not sure what I'll call them yet, but here are some preliminary chapter titles.

Chapter I: 221B Baker Street

Chapter II: Seeking Hyde

Chapter III: The Mutilated Body

I'm not happy with the first one, but I'll work on it.

I was going to write about the YA novel tomorrow, tell you how I was doing at the end of the week. But I may as well write about it tonight, because I'm too tired and frustrated to write about anything else. Before I start, notice how many participants we have for the YA Novel Challenge! Remember that you can join and leave at any time. If you want to join, just send me your name and blog URL, and I'll add you to the list.

So first, there's been a lot of controversy over YA novels this week. Meghan Cox Gurdon wrote an article in The Wall Street Journal called "Darkness Too Visible," complaining about how dark and depressing YA novels are becoming. The article starts like this:

"Amy Freeman, a 46-year-old mother of three, stood recently in the young-adult section of her local Barnes & Noble, in Bethesda, Md., feeling thwarted and disheartened.

"She had popped into the bookstore to pick up a welcome-home gift for her 13-year-old, who had been away. Hundreds of lurid and dramatic covers stood on the racks before her, and there was, she felt, 'nothing, not a thing, that I could imagine giving my daughter. It was all vampires and suicide and self-mutilation, this dark, dark stuff.' She left the store empty-handed.

"How dark is contemporary fiction for teens? Darker than when you were a child, my dear: So dark that kidnapping and pederasty and incest and brutal beatings are now just part of the run of things in novels directed, broadly speaking, at children from the ages of 12 to 18.

"Pathologies that went undescribed in print 40 years ago, that were still only sparingly outlined a generation ago, are now spelled out in stomach-clenching detail. Profanity that would get a song or movie branded with a parental warning is, in young-adult novels, so commonplace that most reviewers do not even remark upon it."

In response, Sherman Alexie, the author of The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, which was mentioned as one of those dark, depraved novels in Gurdon's article, wrote a response, also in The Wall Street Journal, called "Why the Best Kids' Books Are Written in Blood." His article ends like this:

"Teenagers read millions of books every year. They read for entertainment and for education. They read because of school assignments and pop culture fads.

"And there are millions of teens who read because they are sad and lonely and enraged. They read because they live in an often-terrible world. They read because they believe, despite the callow protestations of certain adults, that books – especially the dark and dangerous ones – will save them.

"As a child, I read because books – violent and not, blasphemous and not, terrifying and not – were the most loving and trustworthy things in my life. I read widely, and loved plenty of the classics so, yes, I recognized the domestic terrors faced by Louisa May Alcott's March sisters. But I became the kid chased by werewolves, vampires, and evil clowns in Stephen King's books. I read books about monsters and monstrous things, often written with monstrous language, because they taught me how to battle the real monsters in my life.

"And now I write books for teenagers because I vividly remember what it felt like to be a teen facing everyday and epic dangers. I don't write to protect them. It's far too late for that. I write to give them weapons – in the form of words and ideas – that will help them fight their monsters. I write in blood because I remember what it felt like to bleed."

Where do I come out on this? First, I don't know how old Gurdon is, but the books that were around when I was a young adult were just as dark and depressing as the ones that are out now, my dear. For the most part, I avoided those books. That was partly because by the time I was eleven, I was already reading adult novels. I have a vivid memory of reading Angélique and the King in sixth grade. If you don't know anything about the Angélique series, it's about a woman in eighteenth-century France who loses her fortune and has a series of adventures, which involve her becoming involved in one torrid romance after another. In Angélique and the King, Angélique becomes the mistress of Louis XIV. What I remember most about the book is that it was a thousand pages long. It was excellent preparation for my future career as an adventuress.

I also, that same year, read most of the Anne McCaffrey Pern books. My friend Amy Lawrence and I would sit on the swings, talking about how nice it would be if a dragonrider came (a bronze one would be best, but we would make do with a brown) and took us to Pern. Again, excellent preparation for my future career as a dragonrider.

There were a lot of books out there when I was a teenager. I had an instinct for the ones I needed. I didn't need books about teen pregnancy or prostitution. What I needed were books that gave me a vision of life as more adventurous, more exciting, than the life I was living. The Angélique and Pern books did me no harm, if little good. But that year I also read The Lord of the Rings, and that book did me great good. It showed me a world in which beauty, truth, and honor were actually important. In which magic was real. It showed me a set of ideals that guided me later in life. It became part of who I am.

Young adults will find the books that they individually need. Some of those books will help them become who they are meant to be. I seriously doubt that any of those books will harm them. The more books they read, the more they will learn to judge for themselves, find their own way.

So what about my own YA novel? I don't know, I'm worried. Because what I'm doing in this first draft is simply getting the story down on paper, making sure the plot works, the characters are consistent. But at this stage, it's missing something – it's missing a soul. I hope I find that soul as I go along. I hope I find what the book is centrally about. I think it's about monsters, what it means and how it feels to be one. But I'm not sure that's anywhere in the first draft.

I think I'm discovering the soul of the book as I go along, and I'm worried that it's not going to be in the story itself. Or that I'll have to rewrite extensively to put it in. I don't know. I think there's going to be a lot of rewriting anyway.

There are two things I want to end with. First, I lost a week, but I seem to be writing an average of about 500 words a day. That's partly because I'm ending up writing the chapters by hand. They don't come easily enough to simply type. So I hand write a chapter one day, then type it up the next. Second, I'm having to remind myself of something that I emphasized in the Wiscon writing workshop. I'm going to write it here in case it helps anyone else.

Take a look at the ends of your chapters. Are they good places for your reader to put down the book? Take a short break? If so, you're doing it wrong. You want each chapter to end in a way that leads into the next chapter. That makes it difficult for your reader to put the book down. We have a tendency to seek closure. But closure at the end of each chapter defeats your purpose, which is to keep the reader reading. I'd like to give you an example from the end of Chapter 2, but it's on my virus-y computer. So here is a preliminary example from the end of Chapter 3, which at the moment is just a mass of handwriting.

"Mary was already thinking of the box of documents Mr. Guest, her solicitor, had sent her. It would take hours, perhaps all night, to go through them. Well, she would have Mrs. Poole make a strong pot of tea. What secrets had her father kept from his family? She did not know, but she wanted to find out."

That's all right, it does gesture toward the next chapter, but it's not as impelling (is that a word?) as I want it to be. It needs something more. The second chapter ends with the information that there has been another murder. I need something like that. Well, hopefully I'll find something.

And hopefully I'll get my computer back tonight. This has been a very frustrating day.

June 8, 2011

The Half-And-Half Life

Normal people sing in the shower.

I am a writer. Therefore, I am not a normal person. Instead of singing in the shower, I write dialog. There I was this morning, in the shower, imagining what Mary and Diana would say to one another as they were going through Jekyll's documents, what they would find. I thought, how will they learn about Beatrice? Then realized that of course, Mrs. Poole would tell them. She's the one who buys the penny papers. She would have seen the advertisement.

This blog post is a follow-up to the one called "The Inner Life." That post made me realize the extent to which I live half in and half out of the world. I think all writers do.

In that post, I mentioned riding the T, looking at the people. (Normal people don't look at one another, on the T.) Sometimes, I try to guess who they are, what they do, based on their external appearance. You can tell the students, for example, but you can even tell the law school students from the undergraduates. Our external appearance, how we present ourselves to the world, conveys so much information about who we are, who we think we are, what we want to be. It's fascinating to study people in that way, try to guess their stories.

And you can pick up details that you can use in your own stories. A construction worker and a student may wear the same pair of boots, but will wear them differently. Those boots will mean different things on the student and construction worker. If I say, "She wore a great deal of gold jewelry, around her neck, on her fingers," you will immediately start to get a sense for the kind of woman I'm talking about, although you'll wait to hear more details. But you will expect something different from a woman who "wore a necklace of small, regular pearls around her neck."

I suppose what I'm trying to say, really, is that as a writer you never turn it off. You are always only half in the world. You are also at the same time half somewhere else.

I'm not sure how that affects other writers, but it affects me in some relatively strange ways. For instance, it's easy for me to lose a sense for what's real. I will be walking through the Arnold Arboretum, looking at the lilacs, remembering them so I can describe their look, their scent. (English and Russian lilacs are completely different. Did you know? You need to pay attention to these details, when you're a writer.) So I can write, "She walked down the avenue of lilacs, their panicles just starting to open, trying to capture their elusive perfume." Something like that. And suddenly I'll remember where I am, somewhere much less romantic than where I imagined.

It can be a little scary, living half in and half out of the world.

On the other hand, the world becomes a magical place, filled with stories. With possibilities, because stories are possibilities. I think writers tend to seek out stories. Tonight, I watched part of a travel show on PBS. The traveler was visiting all the tourist sights in Budapest, a city where I have spent some time. And I thought, how dull! He's missed the whole magic and romance of Budapest. What you want to do in Budapest is walk along the twisting old streets, looking at the nineteenth-century architecture. Stop at a grocery store, buy bread and butter and cheese and salami and tomatoes. (Remember to bring your own bag, because they don't give you plastic bags in the grocery stores in Budapest.) Or stop at a restaurant that has been in the same place for the last hundred years. Sit in the courtyard, order a thick, spicy stew over dumplings with a Hungarian wine. And in the afternoon, go to the Café Gerbeaud and have chestnut paste with whipped cream (which is one of my favorite desserts in the world).

The half-and-half life is a life that becomes magical, romantic, because you can always tells stories about it. And you can always find stories in it.

I'm not sure that I'm describing it very well.

It's a life in which your imagination is always working. In which it is always gathering material for stories, and always imagining stories. Sometimes you have to bring yourself back to reality, make sure the bills are paid. But it also allows you to see the genuine magic of the world we live in, the romance of a city, the beauty of an avenue of lilacs (which does actually exist at the Arnold Arboretum).

It provides insight. It's like the fairy ointment that allows visitors to fairyland to see things they could not otherwise see.

(It also allows you to see that some of the things we believe are real are actually stories. The stock market, for instance. Can you think of a better example of magical thinking? The value of a share of stock exists because we believe it exists. Like fairies.)

And of course, the half-and-half life allows you to write stories. Which allow other people to see fairyland too. That's part of your function as a writer, allowing other people to see things they might not otherwise see themselves, to say, "Yes, that is actually how lilacs smell," or "I'd like to walk down the twisting, narrow streets of that city."

These are preliminary thoughts. What I'm trying to do is describe how I experience the world, which I think is as a writer. But it's a difficult topic, isn't it? And I don't know if other writers experience it the same way.

The Messes

I meant to start cleaning up the messes on June 1st, but I was too sick. And then I was sick all week.

By the messes, I don't just mean the physical messes, although there are those. Would you like to see? The mess beside the shelves:

The mess on top of the shelves:

The mess on top of the other shelves:

The mess on the desk:

If you've been reading this blog for a while, you know that I can't stand messes. So today, I started cleaning them up. That's what I'm going to be doing this summer, cleaning up the various messes in my life. The physical ones will be the easiest. I started today by making lists of the things I need to get done, the dates by which I need to get them done. Here's what the summer looks like:

June:

Make final revisions to dissertation, draft introduction.

Prepare for and teach Odyssey Writing Workshop.

Write Folkroots column on the myth and magic of Narnia.

Write first third of the YA novel.

July:

Revise dissertation introduction, draft abstract.

Prepare for and attend Readercon.

Write second third of the YA novel.

August:

Dissertation will go to committee.

Write Folkroots column on – I'm thinking werewolves or unicorns?

Write third third of the YA novel.

That's the general list. I also have a list of specific things I need to do now, sending in an invoice, doing an interview, that sort of thing. And I have some short stories I've promised to people. I have to go look at the deadlines – I know they're distant, but I should get started on some of the stories, or at least start thinking about them.

Of these things, the dissertation takes first priority, and the YA novel last. That's the one thing I'm doing purely for my own sanity, to keep myself from feeling as though I'm not doing anything at all for myself. I can't take a vacation this summer, I simply don't have the time, so roaming around London with Mary and Diana (they haven't met the other girls yet because I've only written two chapters) will be my vacation.

There is a sense in which, this summer, I will be working rather than living. But that's the price for cleaning up the various messes in my life. It's the price for getting to the fall and starting fresh. (Remember that messy bookshelf? Someday in the not-too-distant future, all those books will go back to the university library.)

Sometimes I'm overwhelmed, sometimes I'm not sure I can do it all. But I have friends who are usually reliable telling me I can, and why should I distrust them about this one thing? And I've already accomplished so much this year, I'm already in such a different place than I was last August. I'm already almost at the end of the road, and while I'm not sure where it leads, I think it will be somewhere exciting. Somewhere I can create the life I want for myself.

I don't want to leave you with images of messes, so I'll leave you with something that is not a mess, but a rather nice order. It's the top of my dresser:

In front of my mirror, I have a silver tray on which I have set my frog pottery bowl filled with acorns, a candle on a silver ashtray, a piece of driftwood with some shells, and my rock with BELIEVE carved on it. It's an image of order and natural beauty. And it inspires me.

As do all of you, writing about your own lives and the issues you're dealing with. If you're a writer, an artist, a creative type, those issues will always be there. And we have to deal with them as best we can. We will all find our own tools. I believe in making lists; in creating pleasant environments for yourself so you can pay attention to the messes more effectively; in finding inspiration where you can, even if it's a rock. And remembering that you're not alone. We're all in this together, cleaning up the messes, creating the lives we want for ourselves.

June 7, 2011

The Inner Life

In a comment to yesterday's post, Sarah wrote,

"I'd be interested in reading about how you create an 'inner' life that supports your writing. In other words, a focus or groove or way of seeing things that allows you to sit down whenever you have the chance and simply get on with writing."

Sarah, I hope you don't mind my reposting your words here. They struck me as very interesting, in part I suppose because they raised an issue that I'd never thought about much. How do I create that inner life? Because it's true that nowadays, when I sit down, I do in fact simply get on with writing. I sit down, and the words come.

If there's a magic to it, I think it's the magic of habit. It didn't use to be that way for me, and I think it's not that way for many people. They sit down and – they wait. That doesn't happen to me anymore. What does sometimes happen is that I sit down, start writing something, and it's the wrong thing. It doesn't work. But the writing is still happening, even if it's the wrong writing (as it were).

I think if you want to be able to sit down and have the words simply come, you have to get into the habit of them coming. It's like anything else. We are creatures of habit: we get into habits in our eating, our sleeping. If we want to become healthier we need to exercise, but it only works if it becomes a habit. And that takes a while.

It's the same with writing.

Think about a sport, or perhaps dance. A dancer would never expect to be able to dance every once in a while, and then get up on stage to perform. And yet writers often expect to be able to do just that. (Not Sarah, I'm sure. But I've met writers who do.) A baseball player who expects to hit home runs has practiced hitting a lot of home runs.

If you want writing to become a habit, you need to keep doing it, and that implies a sort of dedication. Which means you've already decided, within yourself, that writing is important. Your writing is important. I'd always believed that writing was important, and that my own writing could be – perhaps, one day. But at some point I had to decide that my writing was important – not one day, but now. I had to believe. And that only happened about two years ago.

So, I suppose what I'm describing (you see how hesitant I am here, because this is something I haven't thought about much) is a sort of edifice in which belief in the importance of my own writing is the foundation. And on top of that is a structure of habit.

Bound together in places by tricks. For example, if I do sit down to write and can't seem to get words out, I write in a different form. Sometimes I need to write a story by hand. Sometimes I type it. If you could see the YA novel chapter I'm working on now, you'd see that I began writing it by hand, then went to making an outline of certain events to understand their chronology, then made a chart of when certain people were born and when other people died. The page is criss-crossed with arrows. I add text in the margins. Someday, perhaps, it will form an interesting study for a scholar. (There, you see, is the belief. My writing will be important. Of course I can't know if it will be. But I have to believe it to write.) It won't come together as a draft until I type it.

I'm very tired today, and I don't know how the writing will go. I spent the day going to the doctor, confirming that I don't have pneumonia, and indeed I'm actually starting to feel better. The coughing still comes back in fits and starts, but for the most part I can breath, I can work. Perhaps tonight I'll even be able to sleep.

Nevertheless, here I am, writing a blog post. Creating the habit of sitting down and writing. Telling myself that when I sit down, the words come. And they do.

There's one final thing I want to add, which is that underlying the foundation of belief is something deeper, something like a sort of calm. It's as though when I sit down to write, my mind goes home – to the place it always wants to go. To a fishing village in Cornwall, or nineteenth-century London, or wherever my writing takes me, but really to the shore of the sea of imagination. The place where all invention comes from.

Imagine standing on a shore, looking out at the sea, a strange green sea whose waves are always coming in, edged with foam. And the waters of that sea, and the spray, are always forming into shapes: hippocamps, sorceresses, castles. Magical rings, glass mountains, dragons. Warriors. Witches. Trees that bear flowers and leaves and fruit all at once. All the ingredients of story. (I suppose in a way I'm playing with J.R.R. Tolkien's image of the soup. Because the soup of story is made by human beings, but the sea of imagination – that existed long before us, and will exist long after.)

In a sense I always live both where I physically am, and on the short of that sea. Because throughout the day, my mind is imagining. I'm living as a writer even when I'm not writing. (And I'm not joking here. I used to sit on the T, which is what the subway is called in Boston, looking at the faces of the passengers and imagining what historical eras they would fit into most naturally, what they would be in those eras. There are people who are thoroughly modern, people who look medieval. It was a sort of game I played, when I was bored. Try it yourself: look at people and imagine what sorts of roles they would play in a story. What sorts of characters they might inspire.)

So, where were we, before I waxed all lyrical?

I'm the sort of person who likes to make lists, so let's make a list.

1. You need to live an imaginative life, just in general. Spend the day going around and imagining. Don't worry, you'll still look perfectly normal. No one will realize that you're imagining a stranger on the T as the Grand Inquisitor.

2. You need to believe in the importance of your own writing. That deep and fundamental belief will allow you to have the faith you need to put in the hours. The many, many hours.

3. You need to make writing a habit, a regular practice. That's the way you'll be able to, consistently, sit down and write. Some people may not need to do this, may be natural geniuses, I don't know. I rather doubt it? But I know that I need to.

And each of these things supports the other. The more you write, and particularly the more you publish, the more you will believe in the importance of your own writing. (Because that reinforcement really does help.) And the more you will live in your imagination, because you'll be living in your stories, even when you're not writing them.

I suppose what I'm reinforcing, really, is the quotation from Mario Vargas Llosa in the blog post I called "The Tapeworm": that writing is not a hobby, not something you can do on the side. Not if you want to do it well. It's something that will become your life, that will determine how you look at the world, relate to others – relate even to yourself, because you will live in part by the shore of the sea of imagination, which is a magical place to live but also means that you will only ever be half in the ordinary world. Half of you will be elsewhere. And that will be disconcerting to the people around you.

But perhaps artists are always disconcerting, I don't know.

June 6, 2011

Unconsumption

So, as you know, I've been sick.

I've been coughing and coughing, and some days are better, and then the next days are worse, so I haven't known where this whole thing is going. I suppose it's silly of me to complain of a cold, or whatever this is, when it's only lasted a week. After all, some people are really sick. It goes to show, I suppose, how used I am to being healthy. To being able to push myself to do things. This week, I haven't been able to push myself at all.

Last night, I couldn't sleep again except in fits and starts, then I finally got some sleep this morning and had the best dream (about meeting a friend I haven't seen in a long time). When I woke up, I was better, not so much coughing, but very tired. I didn't have the energy to do anything. Except – write.

On one of those nights when I hadn't been able to sleep, I'd hand-written a chapter of the YA novel, and today I was able to type it up. Which is good, because at this point I'm terribly behind on my word count. But the best laid plans of mice and men do you know what, and today I was able to type 2000 words.

I don't know if they're good words, I don't know anything at this point, I'm stuck in radical uncertainty. I may be learning how not to write a YA novel. But I'm holding on to one thing. Last summer, at the Sycamore Hill writing workshop, as a critique of the story I had brought, someone said, "I wanted to read a Theodora Goss story." So I've been thinking, how does Theodora Goss write a YA novel? I don't know yet, but I do know that I'm writing it in the way I write anything – it's complex, layered, allusive. And it has Sherlock Holmes in it. (Don't worry, he's not going to play a leading role. But it's late nineteenth-century England, so why not?) I'm just going to write it and then other people can tell me, later, whether it's any good.

It's useful that, when I can't do anything else, I can still write, and that writing is such a relief for me. It's my greatest challenge and pleasure, both.

But my blog post for today is about an article I read in Craft Magazine that led me to a blog called Unconsumption. Consumption is about buying stuff. Unconsumption is about recycling and reusing stuff. It's about what you do with stuff that has already been bought.

I'm writing about this concept partly because after I managed to actually get up today, I put on a navy-blue t-shirt from Land's End Canvas and a tan linen skirt that I had bought at a thrift store. It's a beautiful skirt, heavy linen with an embroidered hem, almost like early twentieth-century embroidered table linens. (You'll know what I mean if you've ever seen them in antiques shops.) And partly because I had just been to Wiscon, and I had already written about the people there, about how they are constantly creating and altering. Those are both examples of unconsumption. Shopping at a thrift store is a sort of unconsumption because it deals with something that has already been taken out of the consumer economy, that has already been bought and used and discarded. I suppose we could think of it as the secondary thrift economy. And creating and altering are of course examples of unconsumption because they are either alternatives to consumption or ways of making what has already been consumed your own.

For me, the idea of unconsumption is interesting and important because it supports the creative life. It demands creativity, but also, living less expensively and more simply supports your life as an artist. It means you're calmer, not so anxious. (At least, I know that complication and expense cause me anxiety.) It means you don't need to do as much to support yourself outside of your art. Don't get me wrong, I love material things as much as anyone. We are material things ourselves, we live in the world, and beauty calls to us. But I find that the most beautiful things are, anyway, the things that are unconsumed. The things that have been around for a while, that have the patina of age and use. Old furniture, old linens. When I spurge on something, it tends to be on art, which doesn't feel like consumption but like participating in the cycle of creativity.

There should be a way to tie the two parts of this blog post together, my writing about progress on the YA novel (unless it's regress? I just don't know yet) and the idea of unconsumption, of taking a different attitude toward the consumer culture in which we live. I feel as though they are related, two parts of a single effort, which is to live as an artist. The life supporting the art, the art supporting the life. That's what I'm aiming for anyway, and if I ever write that book on writing, that's what I'll include, because no one seems to talk about it (except perhaps Terri Windling). But I think it helps, if you're an artist of any sort, to have a life that makes art possible, a life that supports you rather than one you're constantly fighting against. (I sometimes feel as though I'm fighting against my life, particularly when I'm commuting or paying bills. Hence the impetus to change my life, about which more all over this blog, in case you haven't noticed.)

This is a rambling post, because you know, the Hacking Cough Disease has affected my ability to think clearly. So I will end in the best way I know, with two pictures of my thrift store skirt.

Yes, I know, it's wrinkled. I don't usually bother ironing linen. But isn't that a nice embroidered hem?

June 5, 2011

The Ring

For a while now, I've been wanting to write about one of my favorite short stories, Isaak Dinesen's "The Ring." If you'd like to read the story, you can do so here.

I recently received additional impetus to write about it because of something Nicola Griffith said. You may or may not know that there has been quite a lot of controversy recently about women writers. Some of it came from V.S. Naipaul's statement that he was better than any woman writer, which is discussed in an article in The Guardian. Some of it came from a poll in The Guardian that asked readers for their favorite science fiction stories. Most of them turned out to be by men. So there's been an ongoing dialog about women writers, and specifically women science fiction writers, in the press.

Nicola called on writers to take what she calls the Russ Pledge:

"The single most important thing we (readers, writers, journalists, critics, publishers, editors, etc.) can do is talk about women writers whenever we talk about men. And if we honestly can't think of women 'good enough' to match those men, then we should wonder aloud (or in print) why that is so. If it's appropriate (it might not be, always) we should point to the historical bias that consistently reduces the stature of women's literature; we should point to Joanna Russ's How to Suppress Women's Writing, which is still the best book I've ever read on the subject. We should take the pledge to make a considerable and consistent effort to mention women's work which, consciously or unconsciously, has been suppressed. Call it the Russ Pledge. I like to think she would have approved."

I'm not going to talk about male writers today, so I'm not worried about that sort of parity. But in a post called "Female Invisibility Bingo," Cheryl Morgan said,

"If we want women writers to get recognition we have to do something about it. We have to talk about them, and we have to get them back into print. Nicola's post, having noted the problem, was very much all about how we needed to do something, not just sit back and complain."

And Nicola said, in comment to Cheryl's post, "To that end, I'd like to encourage everyone to use their platform to discuss one book/story by a woman this month: a Classic or an Unknown or a Young Turk, doesn't matter."

Well, this is my platform, and I've been meaning to discuss this story for a while. I'm doing it not because Dinesen is a woman but because I think she's one of the best writers in the English language. Significantly better than Naipaul. But it's nice that doing so gives me an opportunity to show support for Cheryl's and Nicola's positions.

So, "The Ring." This is now it starts:

"On a summer morning a hundred and fifty years ago a young Danish squire and his wife went out for a walk on their land. They had been married a week. It had not been easy for them to get married, for the wife's family was higher in rank and wealthier than the husband's. But the two young people, now twenty-four and nineteen years old, had been set on their purpose for ten years; in the end her haughty parents had had to give in to them.

"They were wonderfully happy. The stolen meetings and secret, tearful love letters were now things of the past. To God and man they were one; they could walk arm in arm in broad daylight and drive in the same carriage, and they would walk and drive so till the end of their days. Their distant paradise had descended to earth and had proved, surprisingly, to be filled with the things of everyday life: with jesting and railleries, with breakfasts and suppers, with dogs, haymaking and sheep. Sigismund, the young husband, had promised himself that from now there should be no stone in his bride's path, nor should any shadow fall across it. Lovisa, the wife, felt that now, every day and for the first time in her young life, she moved and breathed in perfect freedom because she could never have any secret from her husband.

"To Lovisa – whom her husband called Lise – the rustic atmosphere of her new life was a matter of wonder and delight. Her husband's fear that the existence he could offer her might not be good enough for her filled her heart with laughter. It was not a long time since she had played with dolls; as now she dressed her own hair, looked over her linen press and arranged her flowers she again lived through an enchanting and cherished experience: one was doing everything gravely and solicitously, and all the time one knew one was playing. It was a lovely July morning. Little woolly clouds drifted high up in the sky, the air was full of sweet scents. Lise had on a white muslin frock and a large Italian straw hat. She and her husband took a path through the park; it wound on across the meadows, between small groves and groups of trees, to the sheep field. Sigismund was going to show his wife his sheep. For this reason she had not brought her small white dog, Bijou, with her, for he would yap at the lambs and frighten them, or he would annoy the sheep dogs. Sigismund prided himself on his sheep; he had studied sheep-breeding in Mecklenburg and England, and had brought back with him Cotswold rams by which to improve his Danish stock. While they walked he explained to Lise the great possibilities and difficulties of the plan.

"She thought: 'How clever he is, what a lot of things he knows!' and at the same time: 'What an absurd person he is, with his sheep! What a baby he is! I am a hundred years older than he.'"

Although Sigismund and Lise are both technically adults, they are still very much children. Lise, at least, is almost playing at her life, particularly her married life. From his shepherd Mathias, Sigismund receives news that some of the sheep are sick. He also hears that there is a sheep thief in the neighborhood. The thief stole some sheep and even killed a man who attempted to prevent the theft. Since Sigismund needs to deal with the sick sheep, he tells Lise to walk on ahead. He will catch up.

"So she was turned away by an impatient husband to whom his sheep meant more than his wife. If any experience could be sweeter than to be dragged out by him to look at those same sheep, it would be this. She dropped her large summer hat with its blue ribbons on the grass and told him to carry it back for her, for she wanted to feel the summer air on her forehead and in her hair. She walked on very slowly, as he had told her to do, for she wished to obey him in everything. As she walked she felt a great new happiness in being altogether alone, even without Bijou. She could not remember that she had ever before in all her life been altogether alone. The landscape around her was still, as if full of promise, and it was hers. Even the swallows cruising in the air were hers, for they belonged to him, and he was hers. She followed the curving edge of the grove and after a minute or two found that she was out of sight to the men by the sheep house. What could now, she wondered, be sweeter than to walk along the path in the long flowering meadow grass, slowly, slowly, and to let her husband overtake her there? It would be sweeter still, she reflected, to steal into the grove and to be gone, to have vanished from the surface of the earth from him when, tired of the sheep and longing for her company, he should turn the bend of the path to catch up with her.

"An idea struck her; she stood still to think it over.

"A few days ago her husband had gone for a ride and she had not wanted to go with him, but had strolled about with Bijou in order to explore her domain. Bijou then, gamboling, had led her straight into the grove. As she had followed him, gently forcing her way into the shrubbery, she had suddenly come upon a glade in the midst of it, a narrow space like a small alcove with hangings of thick green and golden brocade, big enough to hold two or three people in it. She had felt at that moment that she had come into the very heart of her new home. If today she could find the spot again she would stand perfectly still there, hidden from all the world. Sigismund would look for her in all directions; he would be unable to understand what had become of her and for a minute, for a short minute – or, perhaps, if she was firm and cruel enough, for five – he would realize what a void, what an unendurably sad and horrible place the universe would be when she was no longer in it. She gravely scrutinized the grove to find the right en-trance to her hiding-place, then went in."

Something interesting has happened here. If I could describe exactly what it was, this story wouldn't be as powerful as it is. But we see a thought in Lise, the child. A thought that indicates the potential for change in her. The possibility of a sort of cruelty, and the desire for things she has never had before – solitude, power. And a kind of mystery.

Dinesen's stories are great in part because they operate on the moral principle of fairy tales. Fairy tale morality is different from the morality of ordinary human society. In fairy tales, you must figure out the proper moral action for any particular situation. Sometimes you must sew a stone into the wolf's stomach. Sometimes you must thrust an old woman into an oven. It is a morality that is closer to the natural world, to nature itself, than to abstract human laws. Lise is imagining what it would be like to make her husband feel sorrow, and in that moment she is also finding herself. The self that she genuinely and truly is. The adult that will understand cruelty and tragedy and loss. But because she is still a child, she is playing with those concepts.

In the grove, she sees a man.

"She took him in in one single glance. His face was bruised and scratched, his hands and wrists stained with dark filth. He was dressed in rags, barefooted, with tatters wound round his naked ankles. His arms hung down to his sides, his right hand clasped the hilt of a knife. He was about her own age. The man and the woman looked at each other. This meeting in the wood from beginning to end passed without a word; what happened could only be rendered by pantomime. To the two actors in the pantomime it was timeless; according to a clock it lasted four minutes.

"She had never in her life been exposed to danger. It did not occur to her to sum up her position, or to work out the length of time it would take to call her husband or Mathias, whom at this moment she could hear shouting to his dogs. She beheld the man before her as she would have beheld a forest ghost: the apparition itself, not the sequels of it, changes the world to the human who faces it.

"Although she did not take her eyes off the face before her she sensed that the alcove had been turned into a covert. On the ground a couple of sacks formed a couch; there were some gnawed bones by it. A fire must have been made here in the night, for there were cinders strewn on the forest floor.

"After a while she realized that he was observing her just as she was observing him. He was no longer just run to earth and crouching for a spring, but he was wondering, trying to know. At that she seemed to see herself with the eyes of the wild animal at bay in his dark hiding-place: her silently approaching white figure, which might mean death.

"He moved his right arm till it hung down straight before him between his legs. Without lifting the hand he bent the wrist and slowly raised the point of the knife till it pointed at her throat. The gesture was mad, unbelievable. He did not smile as he made it, but his nostrils distended, the corners of his mouth quivered a little. Then slowly he put the knife back in the sheath by his belt."

She has gone into the forest and met a man who symbolizes everything outside the comfortable life she has known. He symbolizes the wilderness, and the wildness of human life itself. This is from directly after the last quotation:

"She had no object of value about her, only the wedding ring which her husband had set on her finger in church, a week ago. She drew it off, and in this movement dropped her handkerchief. She reached out her hand with the ring toward him. She did not bargain for her life. She was fearless by nature, and the horror with which he inspired her was not fear of what he might do to her. She commanded him, she besought him to vanish as he had come, to take a dreadful figure out of her life, so that it should never have been there. In the dumb movement her young form had the grave authoritativeness of a priestess conjuring down some monstrous being by a sacred sign.

"He slowly reached out his hand to hers, his finger touched hers, and her hand was steady at the touch. But he did not take the ring. As she let it go it dropped to the ground as her handkerchief had done.

"For a second the eyes of both followed it. It rolled a few inches toward him and stopped before his bare foot. In a hardly perceivable movement he kicked it away and again looked into her face. They remained like that, she knew not how long, but she felt that during that time something happened, things were changed.

"He bent down and picked up her handkerchief. All the time gazing at her, he again drew his knife and wrapped the tiny bit of cambric round the blade. This was difficult for him to do because his left arm was broken. While he did it his face under the dirt and suntan slowly grew whiter till it was almost phosphorescent. Fumbling with both hands, he once more stuck the knife into the sheath. Either the sheath was too big and had never fitted the knife, or the blade was much worn – it went in. For two or three more seconds his gaze rested on her face; then he lifted his own face a little, the strange radiance still upon it, and closed his eyes.

"The movement was definitive and unconditional. In this one motion he did what she had begged him to do: he vanished and was gone. She was free."

Lise turns around and leaves the grove. Sigismund sees her and calls to her, then catches up to her. He sees something in her face that makes him ask her what is the matter. She tells him that she has lost her wedding ring.

"As she heard her own voice pronounce the words she conceived their meaning. Her wedding ring. 'With this ring' – dropped by one and kicked away by another – 'with this ring I thee wed.' With this lost ring she had wedded herself to something. To what? To poverty, persecution, total loneliness. To the sorrows and the sinfulness of this earth. 'And what therefore God has joined together let man not put asunder.'

"'I will find you another ring,' her husband said. 'You and I are the same as we were on our wedding day; it will do as well. We are husband and wife today too, as much as yesterday, I suppose.'

"Her face was so still that he did not know if she had heard what he said. It touched him that she should take the loss of his ring so to heart. He took her hand and kissed it. It was cold, not quite the same hand as he had last kissed. He stopped to make her stop with him."

Sigismund asks her if she remembers where she had the ring on last, where she lost it. To both questions, she answers "No." And that's how the story ends.

It's a strange, enigmatic story, one of my favorites. It's about a woman who has, in one moment, become an adult. Who has realized that her former life was a sort of game she can no longer play. She thought of playing at cruelty and loss, and then she encounters it, the reality of it. The reality of the tragic impulse at the heart of things, which is more evident perhaps in the natural world than in human society, particularly for a wealthy young woman.

For me, this is in a strange way a love story. In the grove, Lise encounters her opposite and complement, the wild man who shows her the path to her own identity. She is not, after all, the Lise she thought she was. And something happens to him as well, although we do not know what. They are both transformed by the encounter. The wife Sigismund had yesterday is not the same one he has today. We do not know where Lise will go from here, what will happen to her. But it will not be at all what her family wanted or expected for her. She will go on a different path.

Dinesen often ends stories like this, with us not knowing, and yet knowing, what will happen. But the heart of the story is the transformation in the grove. Lise loses something (the ring, her old certainties), and yet this is also the way to become the person she must become. That vision – of needing to understand a way of being that is not society's way, but the way of the natural world or the fairy tale – is perhaps what I value most about Dinesen as a writer. And why, although her stories contain almost no magic, I nevertheless find them magical.

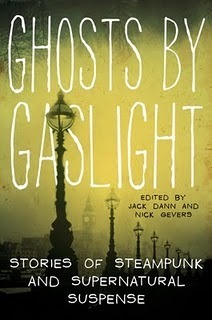

Ghosts by Gaslight

My goal for today was to change out of pajamas, and I'm happy to say I achieved that goal. Around noon, after thoroughly dosing myself with Robitussin and Mucinex, I was able to get up. I spent the afternoon in a t-shirt and gypsy skirt, sitting on the bed, making final revisions to the Secret Project. (You know what a gypsy skirt is, don't you? It's a skirt in tiers, perfect for dancing and proofreading in. Like the one I tangoed with Genevieve in, at Wiscon.) It took forever, because my brain is working at a fraction of its usual speed. But I'm hoping that yesterday was the worst of it, and that I'm actually starting to get better.

Now, I have to confess something. Every once in a while (which is a euphemism for often), I check my name on Ice Rocket. Do you know what Ice Rocket is? You should, if you're a writer. If you go to the site and put in your name, you can see where people are mentioning you online: on blogs, facebook, twitter, etc. It's a useful way to track reviews of stories, comments on blog posts, that sort of thing. And today I noticed that Jack Dann had posted a picture of the cover for Ghosts by Gaslight. Here it is:

Isn't that a great cover? Here's what Jack says about the book: "Ghosts by Gaslight, an anthology Jack has edited with Nick Gevers, will be out in September. It has a great line-up of stories by James Morrow, Peter S. Beagle, Terry Dowling, Garth Nix, Gene Wolfe, Margo Lanagan, Sean Williams, Robert Silverberg, John Langan, John Harwood, Richard Harland, Marly Youmans, Theodora Goss, Lucius Shepard, Laird Barron, Paul Park, and Jeffrey Ford."

Can I just point out what fantastic company I'm in? This is an anthology of ghost stories set in the nineteenth century, and it contains my story "Christopher Raven." If you're interested, you can pre-order it here.

(At this point, the post was interrupted by a fit of coughing and another shot of Robitussin. I really am doing better. I even slept most of last night, other than the tossing and turning and waking up before dawn. But this cough is going so, so slowly.)

I mention Ice Rocket because I've noticed something interesting. Internet mentions of writers go up when they've just had something come out: a novel, a story. For example, right now everyone is talking about Ellen Datlow's Teeth and the new Bordertown anthology, Welcome to Bordertown, edited by Ellen Kushner and Holly Black. The writers in those anthologies are getting a lot of mentions. So as a writer, your internet buzz will depend on what you have coming out, when.

I know, you may hate the whole idea of internet buzz. But the internet is where we live nowadays, just as, a hundred years ago, we might all have wanted to live in Paris. And if you think about it, that really is liberating. We don't have to move into artists' enclaves in Montparnasse, drink absinthe in cheap bars with showgirls, although some of you might like to. And internet buzz is helpful because it lets people know that you're out there. Writing, available for projects.

If you blog, you have something coming out, something people can discuss, as often as you post. You can, if you decide, have something coming out every day. It's not the equivalent of a novel, not even the equivalent of a story. But it's something. And if people like what you post, they look out for your stories and novels.

I write all this because when I went to the Odyssey writing workshop, I was introduced to the idea of buzz. It was a mysterious thing that writers like Kelly Link and Ted Chiang had, and no one knew exactly how it was generated. At one point, I think around the time my first short story came out, I was told that I had buzz, and I was worried that whatever it was, whatever it represented, I would somehow miss it. Especially since shortly after, I had a child and had to work very hard and did not do much writing for about three years.

Recently, a friend of mine, a very good short story writer who was contemplating writing his first novel, told me that he was afraid he'd missed his opportunity. I told him that was ridiculous. That although chance does enter into writing and publishing, as it does into anything else, more often than not we make our own opportunities. Which reminded me of a post I had read by Dean Wesley Smith on whether or not it was possible to kill a writing career. His response was that the only way to kill a writing career is by not writing. And I have certainly seen writers do that.

There's no magic to buzz. It depends on the quality of your writing and the frequency with which you get it out there. Talent and frequency together are a magical combination.

And so, whether you're a beginning writer or a writer whose career isn't going as well as you would like, you need to do the same things. Write as well as you can. Get your writing out there as often as possible. Chance will still be a factor in the equation. I've had a friend tell me that the best story he's ever written did not get attention when it was first published. To which I say, offer it for free on your website. Publish it as an ebook. Make it available. If it's that good (and it is), it will get the attention it deserves.

For better or for worse, we're living in a brave new technological world. It offers writers opportunities they've never had before. When have writers had the opportunity to be published every single day? And yet, as soon as I click on the "Publish" button to the upper right hand corner of my screen, I will have published what is essentially a short essay. Which is exactly what I'm going to do – right – NOW.

June 4, 2011

The Creative Mind

This morning, I called in sick. This consisted of me saying, to anyone who could hear me, "I'm sick. I'm not going to do anything today." I don't know if anyone actually heard me, since no one was in the room at the time, but it seemed to have had the desired effect. I have not done anything today. Except sleep.

I've spent the day alternately sipping small amounts of Robitussin, one of the most disgusting liquids ever invented, like drinking medicinal Maraschino cherries, out of a small plastic cup, and sleeping. The Robitussin has allowed me to sleep, for which I am most grateful. Although I'm worried that I'll become an addict, end like a twenty-first century Lizzie Siddal, overdosing on that sickly red syrup. (Don't laugh. Laudanum, Robitussin. It could happen.)

I did eventually get up and turn on the computer. And on the Clarion Workshop blog, I read a post by John Kessel called "Desperation." It's about a song called "Trying to Tell You I Don't Know" by Freedy Johnson, whom I'd never heard of before. You can listen to the song here (just click the play button).

Here's what John has to say about the song:

"This song is autobiographical. Freedy Johnston was a smart homely kid from Kansas, not the source of a lot of world famous rockers or anything else, and he wanted desperately to make it. He kicked around for a number of years in the 1980s, dropped out of college, lived in Lawrence playing various loser gigs, moved to New York City, and was not getting anywhere. So when his grandfather died and he inherited the family farm, he sold it in order to raise money to record an album.

"Think about that.

"You want to create so bad, you are so convinced that you have something in you that is worth saying, that you will sell your birthright in order for the chance to speak what you hope is in you. To regular people it's insane, even some sort of crime. You yourself don't even understand why, or whether it is worth it. You know it's crazy, you are in radical doubt about your ability, you just sold the house where you learned to walk for the chance to go on the road and play a bunch of miserable one-night gigs, to pay the band, to spend fifty bucks for the van, to get your guitars out of hock – your grandfather's sweat and blood being dribbled away for something he would probably scorn. It hurts you to do this, you're bleeding. You owned the map to the fucking sky and sold it for a chance to play to a bunch of strangers you don't even know. Are you nuts?

"Well, in the eyes of the world, maybe you are. You are a writer, or you ache to be one. You will make big sacrifices in order to come to Clarion, to spend six weeks of your life taking your best shot. You leave your family behind, you quit your job, you break up with your boyfriend, you spend thousands of hard earned dollars, maybe go into debt, all on a wild chance to write stories for strangers. You are taking a big risk. You may not make it. Even if you do, like a toddler learning to walk, you are going to fall down a lot before you learn to walk. Always."

Reading what John wrote above, I thought – yes, that's what it feels like. "You want to create so bad, you are so convinced that you have something in you that is worth saying, that you will sell your birthright in order for the chance to speak what you hope is in you." And you know what? You'll do it without thinking twice about it, because that's simply the way it is, that's simply what you have to do to survive. Because if you don't get out what is in you, if you don't speak with the voice you have, you're going to die. At least, that's how it feels.

And if you're sane enough, you realize how completely crazy that sounds to other people. And you realize that you're not like other people, and will never make the choices they make. And that somehow puts you on the edge – of society, of your family (unless you come from one of those crazy families, and most of us don't). The hardest part of it is that "you are in radical doubt about your ability" – you don't know whether you can do it until after you've done it, and then you don't know whether you can do the next think until after you've done that. You're constantly on the edge of uncertainty.

But in order to do what you need to do, you'll take uncertainty.

We all experience artistic creativity in various ways, so I can't say that what John wrote is true for all of us. But I can say that it's true for me, and I suspect it's true for a lot of you.

I have one addendum, which is that it's dangerous to keep an artist from creating, from practicing her art. It's dangerous to say, "Don't make that album, stay on the farm. Live the life your family has always lived." Because the artist will literally not be able to do that. It's as dangerous to keep an artist from her art as it is to keep a mother bear from her cub. And as likely to end badly.

What John wrote reminds me of a quotation I've always liked from Pearl S. Buck:

"The truly creative mind in any field is no more than this: a human creature born abnormally, inhumanly sensitive. To him, a touch is a blow, a sound is a noise, a misfortune is a tragedy, a joy is an ecstasy, a friend is a lover, a lover is a god, and failure is death. Add to this cruelly delicate organism the overpowering necessity to create, create, create, so that without the creating of music or poetry or books or buildings or something of meaning, his very breath is cut off from him. He must create, must pour out creation. By some strange, unknown, inward urgency he is not really alive unless he is creating."

Yes, I feel this too. I sometimes have to remind myself that a touch is not a blow, a misfortune is not a tragedy, failure is not death. Although it's rather useful, actually, that a joy is an ecstasy. But that overwhelming necessity to create: I saw it among my friends at Wiscon. They are constantly making things. When they buy things, they are constantly altering them. They compulsively alter the spaces around them, create spaces that are individual, their own. They can't help it.

Which may be why, even though I've been sick all week, even though I declared this an official sick day, I'm sitting here in pajamas writing a blog post.

My goal for tomorrow: change out of pajamas.

June 3, 2011

Who Killed Amelia?

A couple of status reports. First, two more writers have joined the YA Novel Challenge and blogged about their goals. Take a look at these posts:

Second, I'm still sick. I can't seem to get rid of the cough, and the cough won't let me sleep, so I've been staying up late working. Last night I stayed up, writing the scene in 221B Baker Street. Despite being sick, staying up late imagining dialog, imagining what the inside of 221B Baker Street looks like, is a deep, deep pleasure. (There's a stuffed alligator on the sofa. And a lot of cigarette ash. Mary is not amused.)

That's is, there's no third. That's all the status report I have for you today.

But a long time ago, I promised that I would tell you who killed Amelia Price. (If you still even remember that post. If not, look here.) And we'll pay attention to the reading protocols.

(Last night, I sat in front of the television, coughing and watching one of the police procedurals. For about ten minutes, until The Actor Who Always Plays the Killer showed up. At that point, the show was over for me. I knew the show wouldn't do anything as interesting as NOT make him the killer, so the rest of the hour would involve elaborate ways for the other characters to not realize that he was the killer. If the show wasn't going to treat me like a knowledgeable viewer, what was the point of watching?)

On to the murder mystery. Let me summarize.

1. Amelia Price lives with her aunt, Emmaline Price. Amelia has just finished her third year at Harvard before coming home from summer vacation. One June night, she is shot. Her body is found the next morning in one of the fields close to the Frobishers' house. She was shot at relatively close range, from the front so she probably saw her killer. Emmaline is the housekeeper for the wealthy Frobishers. There are three of them: Elaine Frobisher, who is a widow, and her two sons, Lance and Galahad Frobisher. Lance works at the law firm his father founded. He was Amelia's boyfriend until they broke up over Thanksgiving break. Galahad is in college at Princeton. He has always had a crush on Amelia, but she has always rejected him.

2. On the night of the murder, there was a break-in at the Frobishers' house. The Frobisher were at a local charity ball, but Lance says he took a telephone call from a client for an hour and Galahad says he wandered around outside for a while because he hates to dance. When he came back, he couldn't find his mother, although she swears she was in the ballroom the entire time. The butler, James, had the night off. He was at the local bar, and two of his buddies swear that he was with them until they took him home, drunk. The maid, Maire Ross, was there, but she says that she slept through the whole thing. Maire, who is from Ireland and has overstayed her visa, is pregnant with Lance's child.

3. Amelia's father, Martin Ames, came from a wealthy family. His mother, Hillary Ames, left Amelia a lot of money in a trust fund. Elaine Frobisher, who was a friend of Hillary, is the trustee. Amelia's father is in jail for shooting Amelia's mother. He was an alcoholic and shot her one night while he was drunk. He claimed it was an accident, but the jury convicted him of manslaughter. Amelia was really Amelia Ames, but when she went to live with her aunt Emmaline, she took her mother's name. She was only seven. Martin Ames was released from jail a week ago. He's supposedly clean and sober. He's been sleeping in the woods around the Frobishers' house.

4. There are a couple of other things you should know. James is not the butler's real name and he has a rap sheet. Lance has been accused of being physically abusive by a former girlfriend. Galahad has pictures of Amelia, a lot of them. He keeps them in a dresser drawer. In her safe, Emmaline has pictures of Elaine Frobisher from when she worked in a gentlemen's club. (Yes, she was a stripper. And probably a prostitute.) And Amelia was shot with the same gun that her father used to kill her mother.

I received a number of ingenious answers when I first posted this scenario. Let me take you through how I thought about it myself.

One important murder mystery protocol is that under the right circumstances, anyone can commit murder. So everyone is a suspect. Here are possible reasons and ways in which any of these characters could have murdered Amelia.

Lance: could have snuck out of the charity ball and killed her because he's still angry over their breakup. He wants her back and she won't agree to it.

Galahad: could have snuck out of the charity ball and killed her because he's obsessed with her and she won't pay attention to him.

Maire: could have lied about sleeping through the burglary and gone out to kill Amelia because she and Lance were planning on getting back together, and Maire would be alone with an illigitimate child.

Martin Ames could have killed Amelia because he's mentally unstable. In fact, he's probably going to be the first suspect. But Darcy Chase, my detective, will know at once that it couldn't be him. In fact, she will suspect that the killing of his first wife was in fact accidental. He's a broken man who just wanted to see his daughter again. He's unlikely to have shot her. And he's not the most likely person to have his gun, not after all these years.

By the way, halfway through the investigation the gun is found in the forest, as though Martin had simply left it there. Darcy will correctly deduce that someone is trying to frame him.

Another important reading protocol is that when there are two crimes, you need to untangle them. Here, there was a burglary on the same night. There is initially suspicion that Darcy saw the thieves and they shot her, but if she had seen strange men in the woods at night, she would have run, whereas the evidence shows that she was not afraid. She was killed by someone who was able to approach her, get close to her. That rules out Martin as well, because she would never have trusted him that much, not after all the stories she's been told.

Hercules Poirot says that we must allow for one coincidence and no more. The burglary happening that night was a coincidence. It's suspicious that Maire slept right through it, but not if she was given sleeping pills. The person who could most easily have given them to her is James, the butler. She would never suspect him bringing her a glass of milk, whereas she would be astonished if one of the Frobishers did so (even Lance).

James and his friends, the ones who provided the alibi, are the burglars, which lets them out of the murder. The two crimes are almost never linked in that way.

So, we've gotten rid of Martin, James, and Maire. Who's left? Lance and Galahad had motive and opportunity. Elaine had opportunity but no motive. Emmeline had opportunity, but why in the world would she want to kill her own niece? In fact, she loses a small income she earned while her niece was alive, for serving as her guardian. We have to ask about money, but when Amelia dies, the fortune in her trust fund goes to a hospital. So no one gets it.

Now what? We can trace the gun. Hillary Ames had it for a while, but no one knows what became of it when she died. If I were writing an actual murder mystery, at this point I would probably muck around a bit with Lance's alibi, show that it was valid, then that it wasn't, all based on different time zones.

Here's how Darcy solves the mystery. There's one person who has never seriously been suspected. Emmaline Price actually loses money when her niece dies. But for several years now, Emmaline has been blackmailing Elaine Frobisher with those pictures. Elaine isn't actually as wealthy as she seems. Her husband's death has left her in a difficult financial situation. (Lance is actually trying to save the firm.) So she's been taking money from Amelia's trust fund. She tells Emmeline that she's been taking the money, and that as soon as Amelia turns twenty-one, which will be in three weeks, the entire game will be up. Elaine will be exposed as a former stripper and a current thief. But worse, Emmeline will be exposed as a blackmailer. Emmeline has been respectable her entire life. She is not about to let that happen.

She tells Elaine to give her Martin's gun. (Elaine is the one who has it, and the only one who could, logically. After the trial, it was returned to Hillary. It's an antique gun and has significant value. Elaine was Hillary's friend and Amelia's trustee. Hillary passed it on to her in case Amelia should ever ask about it. She wanted Amelia to be the one to decide whether it should be kept in the family, put in a museum, or destroyed.)

She chooses that night because the Frobishers will be away, but also because she's seen Martin in the woods. As far as she's concerned, he killed her sister and deserves to be framed for Ameila's murder. Emmeline has no compunctions in killing Amelia, whom she thinks of as an Ames rather than a Price. She meets Amelia in the woods, and when Amelia gets close enough, she shoots her.

Elaine was absent from the charity ball for a while because she was giving the gun to Emmeline. Galahad really did wander around outside for a while.

If Emmeline had succeeded in casting the blame on Martin, the trust funds would have passed to the hospital, where Elaine is on the board. She would have ensured that the trust was never investigated thoroughly. So both she and Emmeline would have been safe.

I've fudged a bit over why they needed to kill Amelia that night, with such urgency. I think I'll have to invent an impending visit from a lawyer. But I hope this all makes sense? And it's clear how I'm thinking about and responding to the protocols?

I've been sitting up for a while writing this draft, and I need to go lie down again. I've noticed that with the constant diet of cough drops, I'm simply not hungry for ordinary food. But I'm tired all the time, so I'd better get some rest.

I hope my solution to the mystery makes sense. Emmeline is the logical killer in terms of the protocols. She seems so sweet throughout, until you realize that she's done. There are all sorts of things I haven't done here, all sorts of ways I haven't played with the protocols. But perhaps I have shown a bit about how they work. Emmeline is exactly the sort of person who is the murderer in murder mysteries. Real life doesn't work quite that way, does it?

Seriously, I'm going to pass out. So more later. But this exercise has been very interesting. Could I write a murder mystery? You know, I just might pull it off . . .