Theodora Goss's Blog, page 56

June 19, 2011

Four Things

First, I saw the video, and it reminded me of the painting, which reminded me of the photograph and a poem I had written some time ago. But I'll give you the poem first, then the photograph, then the painting, then finally the video. This is the way my mind works, most of the time: the world becomes a continual series of links.

The River's Daughter

She walks into the river

with rocks in her pockets,

and the water closes around her

like the arms of a father

saying hello, my lovely one,

hello. How good to see you,

who have been away so long.

The eddying water

tugs at the hem of her dress,

and the small fish gather

to nibble at her ankles, at her knees,

to nibble at her fingers. They will find

it all edible, soon, except

the carnelian ring by which her sister

will identify her.

Bits of paper

float away, the ink now indecipherable.

Was it a note? Notes for another

novel she might have written, something new

to confound the critics? They will cling

to the reeds, will be used

to line ducks' nests, with the down

from their breasts. The water

rises to her shoulders, lifts her hair.

Come, says the river. I have been waiting

for you so long, my daughter.

Dress yourself in my weeds,

let your hair float in my pools,

take on my attributes: fluidity,

the eternal, elemental flow

for which you always longed.

They are found not in words but water.

You will never find them while you breathe,

not in the world of air.

And she opens her mouth

one final time, saying father,

I am here.

June 18, 2011

Exquisite Things

My poor old camera is on its last tripod (get it? on its last legs, but cameras don't have legs? sorry, it's been that sort of day). And I still haven't had time to figure out my lovely new camera yet. So I apologize in advance for the quality of these pictures.

As you know, I've been having one of those weeks. I've been working very hard, and today I needed a break. So first, I went to downtown Lexington. I bought myself some ice cream, a scoop of heath bar with extra heath bar pieces on top. With my ice cream, I climbed up to my favorite place in Lexington: the top of the bell tower hill. There's a large rock up there, and from it you can see all around. Here I am on the rock, in weekend working gear (an old v-neck shirt, an old pair of jeans that are two sizes too large but very comfortable, Keds with no shoe laces because they broke and I've never bothered buying new ones). Looking somewhat ragged, but then I was up until 3:00 a.m. last night, reviewing and correcting.

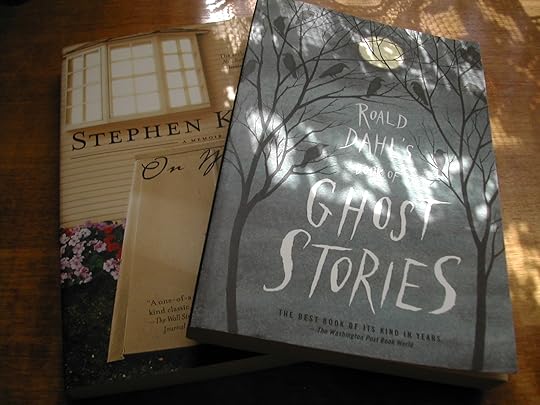

Then, I went to the library, which was having a book sale, and bought two books: an anthology of ghost stories edited by Roald Dahl and On Writing by Stephen King. I've actually read very little by Stephen King, having been traumatized by Pet Sematary when I was a teenager. Also, he writes in a style that I've never found all that compelling, although perhaps I haven't read the right stories. But I'm interested in what he has to say about writing.

And then I drove in the other direction, toward the town of Bedford, to an antiques store that had been recommended to me. There, I bought three things. The first was a small silver pin. I'm afraid the photograph did not come out well, and also the silver is tarnished and needs cleaning, but it has a glass insert at the center with a design of oranges and leaves. It's a pretty thing for me to wear on sweaters.

The second was a green Wedgewood plate. I have several pieces of green Wedgewood, and this is a nice addition to my collection.

The third was a Chinese snuff bottle with a reverse-painted design of rabbits on both sides. I love Chinese snuff bottles, and I liked this design.

Part of what makes these things exquisite is their size: the pin is about an inch and a half long, the plate is about four and a half inches in diameter, and the snuff bottle is about three inches tall. (And I'm 5'4″, but I wasn't counting myself among the exquisite things. Not looking as ragged as I did today. And I don't know yet whether the books will be exquisite, but I rather think not.)

Then I came home again, to get to work once more. But just as it was getting dark, I walked around the yard, and in one corner I saw three white bellflowers. No one would see them where they were, in the middle of a lilac bush, so I cut them and put them into a vase. They are now sitting on a corner of my writing desk. I think I'll take a picture of them with my cell phone – right now – so you can see what they look like. They're exquisite too. (That's my glass of lime fizzy water, on a coaster I sewed ages ago from cotton scraps.)

And here I am, back home, getting back to work, reviewing and correcting. I'll probably be up until 3:00 a.m. again tonight.

I've been thinking a lot about meaning – what is the meaning of my life, and why do I keep going, even when the going is as tough as it has been lately? Sometimes, to be honest, I'm not entirely sure. It's at those times that exquisite things can help. That I can look to my right, as I'm looking now, and see bellflowers in a vase, and think – yes, lovely. And that gets me through, at least a little while longer.

June 17, 2011

YA Challenge Friday

This week, my work on the YA novel came to a screeching halt. Why, you ask? Because of a sort of writing emergency, something that needed immediate attention. That happens sometimes, when you're a writer. It's happened twice in the last couple of months, on two different projects. Often it has to do with problems that come up just before publication. And then you swing into emergency mode, and there you are, making sure that everything is fixed. Making sure that when the reader gets the book or magazine, it's perfect. Or as perfect as you can make it.

But before I get back to my own YA novel progress, what about the other participants? I've had some comments from people who want to participate, but have not sent me their URLs. If you want me to link to your blog, send me your name and URL (to tgoss@bu.edu), because I can't tell if what you have in the comment is what you want me to use. And I've been terrible about responding to comments lately. I'm so sorry! It's, you know, what I wrote above. Emergencies, and my own exhaustion.

So, those of you writing or revising YA novels, how are you doing? I'd love to hear from you! Here's how I'm doing so far. I have the first five chapters:

1. The Great Detective

2. Seeking Hyde

3. The Mutilated Body

4. Rappaccini's Letter

5. The Poisonous Girl

Those are tentative titles, of course. Some chapters are typed, some handwritten, one still just plotted. I'm going to get back to it soon. I just need to, somehow or other, catch up with everything else.

But working on the novel and on the writing emergency I described above has gotten me thinking about the importance of technique.

We are all readers. We are not all writers. Writing is, at least in part, a craft that is learned. And that craft consists of being able to lead a reader through a story in such a way that the reader participates in it, lives in the story. The story becomes real to the reader. That's a particular skill, and there are techniques the writer uses. What the writer does is craft an experience for the reader.

I'll give you two examples.

She entered the room and heard three knocks. She wondered if it could be his ghost.

She entered the room – knock, knock, knock. What had she heard? Could it be his ghost?

Do you see the difference? You read the first, you participate in the second. You hear the knocks along with the character.

That's the writer's craft. The tools of that craft are words, punctuation marks, even blank spaces. So, for example,

She had finally realized what she should have known all along, that she loved him.

She had finally realized what she should have known all along – that she loved him.

She had finally realized what she should have known all along: that she loved him.

Those sentences mean different things, even though the only actual difference is a punctuation mark. In the first one, "that she loved him" redescribes "what she should have known all along." In the second one, the dash seems to hold those two parts of the sentence in tension. "That she loved him" starts to look more like a conclusion, what she finally realized. And in the third, "that she loved him" is a definite conclusion coming out of the rest of the sentence. It is her realization. All of the sentences say the same thing. But they emphasize different aspects of it. The third one is the most definite.

A good writer knows how to use all the available tools to create effects. A good reader is sensitive to those effects, having been trained by years of reading.

A good reader can feel when he or she is in the hands of a good writer. He or she relaxes, knows that everything will be all right. Characters may die, the world may be destroyed, but the one terrible thing, the one forbidden thing, will not happen – the reader will not be thrown out of the book. The reader will not be out in the cold, looking in, saying, "I don't believe it. It's just a bunch of words."

There's more to writing than technique, of course. There's art, which raises writing above mere effect. Which gives it mind and soul. But I find that I return to technique often. I return to it whenever something isn't working, when I think, how in the world am I going to make this chapter interesting to my reader? How am I going to make it vivid? And I find that the best writers have great technical skills: Kelly Link, for instance. Her story "Travels With the Snow Queen" begins,

"Part of you is always traveling faster, always traveling ahead. Even when you are moving, it is never fast enough to satisfy that part of you. You enter the walls of the city early in the evening, when the cobblestones are a mottled pink with reflected light, and cold beneath the slap of your bare, bloody feet."

You're there, right? At least by the words "bare, bloody feet."

I've spent the last couple of days trying to fix things. Which should be fixed soon, and then perhaps I'll be able to catch up with everything else, and then perhaps I'll be able to rest, and this horrible exhaustion will go away. I hope.

But I miss writing my novel. I'm just at the point where Mary and Diana have found out about Beatrice, and they're about to go see the exhibition in which she kills various things merely by breathing on them. And they talk to her, and she tells them about the other girls. And that's the real beginning, when all five girls, my lovely monsters, are together. That's the beginning of what they call the Athena Club. (Oh, I'm not giving anything away. All this information will eventually be on the jacket, you know.) And there's a murder to be solved.

I want to get back to late nineteenth-century London. Because when I write the novel, that's the only time I get to do anything like what the reader will eventually do – live inside it. After it's written, when I'm revising, I'll be outside looking in – making sure that the novel works for the reader, which is a completely different experience. But I want to get back to London and see my poisonous girl in action.

Soon, soon, soon.

June 16, 2011

On Darkness

When I was a teenager, I read Flowers in the Attic. You probably did too, if you are female and around my age. I don't remember much about it, although every once in a while I see a movie version as I'm clicking past some obscure TV channel.

It's a story of cruelty and abuse, rather crudely written. About four children who are locked in an attic, almost starved. And the beautiful older girl has her hair cut off. That's about all I remember.

I mention this book because of the recent controversy about darkness in Young Adult fiction. We're living on internet time now, and that controversy has already blown over, although I suspect it will occur again. These things are cyclical. But no one is seriously going to suggest censoring Young Adult fiction, or negatively affect a genre that is so profitable. After all, we live in a capitalist system. The market decides.

While it was still going on, serious and thoughtful people suggested that there was something troubling about offering such dark images to teenagers, that they genuinely thought such images did harm. And I thought back to my own reading of Flowers in the Attic. Did it harm me?

I have a complicated answer to that question that begins, yes. Reading that book, and others equally dark, put images into my head that I have sometimes wished weren't there. Such books do have the ability to familiarize us with cruelty. They do make our minds cruder. There is a way in which they desensitize us to the real cruelty of the world by familiarizing us with representations of it.

But – and I write this as someone who kept her hands over her eyes during most of Nightmare on Elm Street and never went to see a horror movie again – for me, they acted like a vaccine. I was a sensitive child, and in a way, reading about darkness prepared me for the much greater cruelty and crudity of the world. Reality is worse than almost anything we can write. Growing up involved learning that lesson. Learning not to be shocked by the photographs of Abu Ghraib. It may sound silly to say that Flowers in the Attic prepared me for that. But the book did prepare me for the idea that people could behave in that way. The lesson shocked me then – the reality still does. But it was something I had to learn, to function in the world. (Which, after all, doesn't actually work a whole lot like Little Women.)

There was another kind of literary darkness that I also read, and that affected me differently. It was the darkness of Edgar Allan Poe, of H.P. Lovecraft. The darkness in which Hyde roams London, in which Dracula feeds. That was not crude, ordinary human darkness, but a deeper psychological and metaphysical darkness – and it was profoundly freeing. Its message was – there is something more than this, more than ordinary human society, with its rules and judgements. There are monsters.

In a way, the second kind of darkness offered an alternative to and even combated the first. In the first, darkness was crude, meaningless. Just the way the world was. In the second, darkness offered something. In the darkness, you could fight monsters, or become one. Becoming a monster, in particular, meant escaping from ordinary human meaninglessness. Monsters didn't wait for Godot. (They had probably eaten Godot in the first place.)

The second kind of darkness was valuable not because it conferred immunity, but because it provided the possibility of freedom. At least, I felt it was freeing. By the time I finished college, I had read every Poe and Lovecraft story I could find. The Lovecraft stories were more difficult to find back then. They had not yet entered the cultural mainstream. When you saw Campus Crusade for Cthulhu stickers and Miskatonic University sweatshirts, you smiled because you knew – here was one of your tribe.

I feel as though I should come to some sort of grand conclusion about darkness in literature, about the two types of darkness I've written about here. But I don't have one. Today has felt dark, and I'm grateful that there's a hand in that darkness, as monstrous as my own, to clasp. Perhaps my grand conclusion is this: I recently bought a new edition of At the Mountains of Madness, which I have not read for a long time. I think it will be the next book I keep on my bedside table, to read before I go to sleep each night. I will find it profoundly reassuring. And when I read the news, about what the crude, ordinary, human monsters are doing, I will think about how wonderful it would be if they could be eaten by Shoggoths. And I will look out into the darkness of the night, and feel that there is so much more than these human lives we live, this human world we have created for ourselves. There are wonders in the darkness.

Monstrous Dora:

June 15, 2011

Dreaming of Fairyland

One of my favorite poems is W.B. Yeats' "The Man Who Dreamed of Fairyland."

He stood among a crowd at Dromahair;

His heart hung all upon a silken dress,

And he had known at last some tenderness,

Before earth took him to her stony care;

But when a man poured fish into a pile,

It seemed they raised their little silver heads,

And sang what gold morning or evening sheds

Upon a woven world-forgotten isle

Where people love beside the ravelled seas;

That Time can never mar a lover's vows

Under that woven changeless roof of boughs:

The singing shook him out of his new ease.

I have fallen terribly behind. As you know, I was sick for two weeks. And then my computer was sick, and now I have so much to do, and so I haven't been able to get to the smaller things at all, like answering emails or responding to comments on this blog. I've had to focus on the larger things: responding to copyedits on the Secret Project, preparing to teach at Odyssey, writing my next Folkroots column, and revising my dissertation. All very large things.

"His heart hung all upon a silken dress, / And he had known at last some tenderness": he found love, mortal love, but all the silver fish sang of Fairyland, "Where people love beside the ravelled seas; / That Time can never mar a lover's vows." Where love is immortal.

He wandered by the sands of Lissadell;

His mind ran all on money cares and fears,

And he had known at last some prudent years

Before they heaped his grave under the hill;

But while he passed before a plashy place,

A lug-worm with its grey and muddy mouth

Sang that somewhere to north or west or south

There dwelt a gay, exulting, gentle race

Under the golden or the silver skies;

That if a dancer stayed his hungry foot

It seemed the sun and moon were in the fruit:

And at that singing he was no more wise.

Some people work at desks, and when I type, I do it at a desk, of course. But so much of my work I do wherever I have space. So, for example, the work I was doing today, I spread out on my bed. (Today: responding to copyedits.)

When I write, I often do it on the bed, lying on my stomach and leaning on one elbow. Or leaning back against the headboard, with the notebook propped on my knees. Or in my chair, with the notebook on one broad arm. (It's a mission-style chair, the arms are very broad).

"His mind ran all on money cares and fears, / And he had known at last some prudent years": so finally he wasn't worrying about money, as we all do. At last he had some savings, but the lug-worm (which, by the way, is large marine worm of the phylum Annelida) sang of a place where there are no money cares and fears at all. Where value is calculated otherwise.

He mused beside the well of Scanavin,

He mused upon his mockers: without fail

His sudden vengeance were a country tale,

When earthy night had drunk his body in;

But one small knot-grass growing by the pool

Sang where – unnecessary cruel voice –

Old silence bids its chosen race rejoice,

Whatever ravelled waters rise and fall

Or stormy silver fret the gold of day,

And midnight there enfold them like a fleece

And lover there by lover be at peace.

The tale drove his fine angry mood away.

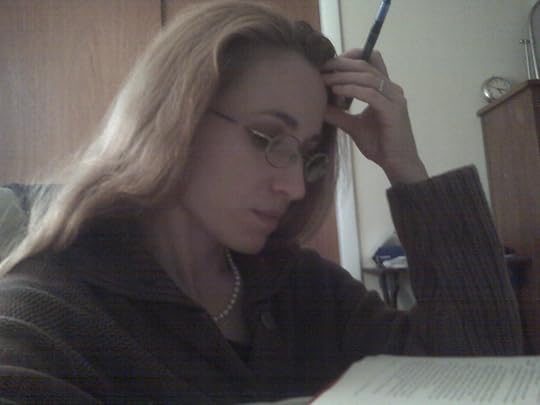

Today, I spread the copyedits out on the bed and knelt beside it, as though it were a low table. Which looked rather like this, except that this is obviously posed, because I'm holding the pen in my left hand (for effect). I'm right handed, so usually I would be holding it in my right hand. But I couldn't get a picture from that direction that wasn't backlit. This is me in full working mode: glasses, comfortable sweater.

Don't I look all pensive and writerly? Which was I today, the writer in the world, thinking of cares and fears, or the writer dreaming of Fairyland? Because of course the poem is really about being a poet, a writer. It's about what the writer experiences, living that half-and-half life I described. A writer dreams of Fairyland, and that dream transforms ordinary life. Sometimes it makes ordinary life difficult to live.

He slept under the hill of Lugnagall;

And might have known at last unhaunted sleep

Under that cold and vapour-turbaned steep,

Now that the earth had taken man and all:

Did not the worms that spired about his bones

proclaim with that unwearied, reedy cry

That God has laid His fingers on the sky,

That from those fingers glittering summer runs

Upon the dancer by the dreamless wave.

Why should those lovers that no lovers miss

Dream, until God burn Nature with a kiss?

The man has found no comfort in the grave.

Even in death, he has found no comfort – the man who dreamed of Fairyland. Even in the grave he dreams of a place beyond the ordinary world. There is no peace for him, once he has seen Fairyland, and there never will be.

I'm not sure why I combined these two things, the pictures of me responding to copyedits and Yeats' poem. Except that I think they represent the two halves of a writer's life. One half of you dreams of Fairyland and will find no peace in this world, except perhaps when you are piecing together the fragments of that dream, turning them into a poem, a story, a novel. And the other half is depositing checks and responding to copyedits, which are both things I did today. It's a strange life, a life that takes a sort of double consciousness.

Which may be why I ended the day with a terrible headache.

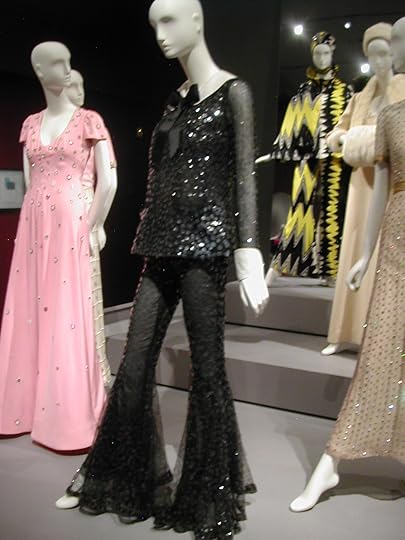

The Scaasi Exhibit

I promised that I would show you pictures of the Arnold Scaasi exhibit, so here they are. The exhibit was small, all in one room, but quite rich in terms of its range and the outfits themselves. You could spend an hour wandering around that room, looking at all the details.

These are clothes as clothes, not clothes as art. For that, you're going to have to wait for Alexander McQueen. So I'm going to critique them as just that – clothes one might actually wear (or not).

The first section of the exhibit focused on the 1960s. You can see the 1960s silhouette in the following dresses. I like that the red velvet cape has a silver lining that echoes the fabric of the dress, and the silver dress has a red velvet bow that echoes the cape. You could be a sorceress in this dress. You would certainly cast a spell.

The polka-dot dress feels so contemporary. This is still the early 1960s, which was influenced by Christian Dior's New Look. The waist was still at the waist, and skirts were still pouffy. This isn't my style (there's no magic in it), but I like the dress.

I liked the details on several of these outfits, like the pink bow on the suit. In any suit like this, I think we're seeing the influence of Coco Chanel. It's still the Chanel suit silhouette. I would wear something like this, if it weren't so heavily beaded.

The short black dress was worn by Natalie Wood. Here we get to the late 1960s silhouette, where you start to lose the waist. You could wear a dress like this to a party (I wouldn't), but it starts to feel retro, whereas the earlier dresses feel more contemporary.

One thing that startled me about the exhibit was the mix of fabrics and other materials. Many of the dresses mixed silk and synthetics. The beading on the turquoise and coral dress below is coral – and plastic. The silhouette on the coral suit is still Chanel.

Here we transition from the 1960s to the 1970s. The dress on the left is late 1960s, the dress on the right is already 1970s. Most of the 1970s outfits were made specifically for Barbara Streisand, and you can see that they represent a different way of thinking about the female body. It's no longer a woman's body. It's a pretty boy's. Slender, without an obvious waist. An Empire silhouette, with pants rather than skirts (although that may have been Streisand's individual preference.) Honestly? I don't know who these would actually look good on. They certainly didn't look good on Streisand.

I do like the long white wool coat with fur collar, hat, and muff (although I don't wear fur). It's very Dr. Zhivago. The black mesh outfit was the one Streisand wore to accept an Academy Award. Under the lights, it looked see-through (although it wasn't). Which was scandalous at the time, although nowadays we think of it as rather ordinary, don't we? We expect wardrobe malfunctions. Bell bottoms: seriously, Scaasi?

You can see the Empire silhouette here – Empire silhouette jumpsuits, which are so 1970s. As is that particular peachy pink, which does not look good on any skin tone. I do like the detailing, though. It looks almost Egyptian.

Oh yes, the strange 1970s lightning-pattern outfit! Obviously created for Streisand in her incarnation as a space alien. Scaasi, what were you thinking? And here we transition to the 1980s, which is the silhouette I grew up with, in the dress covered with black, white, and silver leaves. It's difficult for any woman to look attractive in a dress that fussy.

Didn't quite a lot of us wear a variation of this dress to prom? Scaasi's is the high-end version, but it's no more attractive for its expensiveness. It looks more dated, to me, than the polka-dot dress at the beginning of the exhibit. And why would anyone bring back the bustle?

But this was a beautiful dress! A Snow Queen dress. I would wear this dress in a heartbeat. Anywhere. To the opera, to do dishes. The mix of gauzy white fabric, silver embroidery, and luxurious fur make it magical. You could walk through an enchanted forest in this dress. I want one just like it (with fake fur). It looks simple, without being simple at all.

I liked this dress too. It's a bit over the top, with its feathers and fabric roses and silver embroidery and fur. But still, it's a Queen of the Birds sort of dress. It's dramatic, unusual, and lovely. It just needs something around the shoulders. Or maybe a crown.

And here we come to everything that was wrong with the 1980s. The black and hot pink dress! What were you thinking, Scaasi? It's not even appropriate for prom. And the shoulders! No one should ever wear puffed shoulders. Chanel taught us not to wear puffed shoulders. Listen to Chanel, my sisters! And banish puffed shoulders from your closets forever. On the other hand, the suit on the right is quite nice.

What ordinary dresses Scaasi designed in the 1980s! Or is it that I grew up seeing the knock-offs of these dresses? But there is absolutely nothing distinctive about these.

Or these. And the colors. Yuck! Like wearing scoops of sorbet.

And with the Watermelon Dress, we come to a silhouette that is attractive on no one (except perhaps a few select supermodels). And the blue dress with the white lace appliques is just blah.

So what lessons can we learn from the Scaasi exhibit, my sisters?

1. Dresses from the 1960s can still look fresh and fabulous.

2. The 1970s were a regrettable decade. And let's just pretend that the 1980s never existed.

3. Chanel was always right about fashion. (Other things, not so much. Like collaborating with the enemy in World War II. But the woman knew what looked good on other women.)

4. If you get a chance to look like the Snow Queen, go for it. Don't even think twice.

June 14, 2011

Women Becoming

While I was sick, I watched a movie that had been given to us as a gift and that I had never watched: Julie & Julia. I thought it would be the sort of movie one could watch while sick, and it was.

It's about a blogger, Julie Powell, who decides to cook all of the recipes in Julia Child's Mastering the Art of French Cooking. Half the movie is about Julie's life, half about Julia's life in France learning to cook and developing the cookbook with her partners, Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle. One criticism of the movie is that the Julia parts are more powerful and interesting than the Julie parts. And they are, because – and I write this with no disrespect to the actual Julie Powell – in the movie, Julia is a more interesting character. After all, she doesn't just try to cook from a cookbook for a year. She spends years learning to cook, mastering the actual art of French cooking, and then meticulously trying to adapt French cooking for the American home cook. In other words, she spends years becoming the person we now call Julia Child. The person who changed food culture in this country.

I don't think that's too broad of a claim. Child changed the way we look at food and cooking. I collect old cooking and gardening books, mostly because they are time machines showing me how people once lived. If you've ever seen a cookbook from the nineteen sixties, you'll know what I mean when I say that no one, nowadays, would ever want to cook from them. No one eats like that anymore. (If you've never seen one of those cookbooks, I'll give you an example from one of mine, called Cooking for Two, which charmingly begins, "You have returned from your honeymoon and are about to start the great adventure of homemaking." For dinner, Cooking for Two suggests that you serve the following: Broiled Liver, Potatoes Anna, Creamed String Beans and Mushrooms, Lettuce with Russian Dressing, and Baked Apple Dumplings. Or alternatively, Tomato Juice Cocktail, Halibut Steak with Cheese, Baked Potatoes, Wilted Dandelion Greens, Pear Salad, and Gingerbread with Whipped Cream. Which are the strangest combinations of foods I think I've ever seen.)

The Child sections of the movie were fascinating because it's always fascinating to watch someone work on a project that he or she cares passionately about. The number of eggs she had to poach, so she could get the instructions just right! The number of rewrites she had to do! And she was a fascinating personality, of course. And she was played by Meryl Streep, which doesn't hurt: one technical perfectionist playing another.

But the reason I thought about the movie further, rather than simply dismissing it as something I had watched while sick, was that I had recently seen Coco before Chanel. So here were two movies about women in the process of becoming what they were later to be, and be known as: Julia Child and Coco Chanel. It reminded me that some time ago I had seen The Hours, which is at least partly about Virginia Woolf, unfortunately played by Nicole Kidman in a fake nose.

Three women, each of whom changed the way we do things, deeply and fundamentally: the way we cook, the way we dress, the way we write.

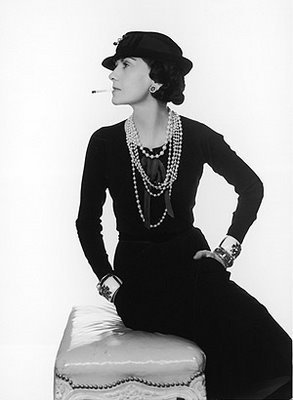

Here is how we dressed before Chanel:

And here is how we dressed after Chanel:

Here is the beginning of Middlemarch:

"Miss Brooke had that kind of beauty which seems to be thrown into relief by poor dress. Her hand and wrist were so finely formed that she could wear sleeves not less bare of style than those in which the Blessed Virgin appeared to Italian painters; and her profile as well as her stature and bearing seemed to gain the more dignity from her plain garments, which by the side of provincial fashion gave her the impression of a fine quotation from the Bible, – or from one of our elder poets, – in a paragraph of to-day's newspaper. She was usually spoken of as being remarkably clever, but with the addition that her sister Celia had more common-sense. Nevertheless, Celia wore scarcely more trimmings; and it was only to close observers that her dress differed from her sister's, and had a shade of coquetry in its arrangements; for Miss Brooke's plain dressing was due to mixed conditions, in most of which her sister shared. The pride of being ladies had something to do with it: the Brooke connections, though not exactly aristocratic, were unquestionably 'good': if you inquired backward for a generation or two, you would not find any yard-measuring or parcel-tying forefathers – anything lower than an admiral or a clergyman; and there was even an ancestor discernible as a Puritan gentleman who served under Cromwell, but afterwards conformed, and managed to come out of all political troubles as the proprietor of a respectable family estate. Young women of such birth, living in a quiet country-house, and attending a village church hardly larger than a parlour, naturally regarded frippery as the ambition of a huckster's daughter."

And here is the beginning of Mrs. Dalloway:

"Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.

"For Lucy had her work cut out for her. The doors would be taken off their hinges; Rumpelmayer's men were coming. And then, thought Clarissa Dalloway, what a morning – fresh as if issued to children on a beach.

"What a lark! What a plunge! For so it had always seemed to her, when, with a little squeak of the hinges, which she could hear now, she had burst open the French windows and plunged at Bourton into the open air. How fresh, how calm, stiller than this of course, the air was in the early morning; like the flap of a wave; the kiss of a wave; chill and sharp and yet (for a girl of eighteen as she then was) solemn, feeling as she did, standing there at the open window, that something awful was about to happen; looking at the flowers, at the trees with the smoke winding off them and the rooks rising, falling; standing and looking until Peter Walsh said, 'Musing among the vegetables?' – was that it? – 'I prefer men to cauliflowers' – was that it? He must have said it at breakfast one morning when she had gone out on to the terrace – Peter Walsh. He would be back from India one of these days, June or July, she forgot which, for his letters were awfully dull; it was his sayings one remembered; his eyes, his pocket-knife, his smile, his grumpiness and, when millions of things had utterly vanished – how strange it was! – a few sayings like this about cabbages."

I'm not picking on George Eliot, whom I like, although not as much as Jane Austen or Charlotte and Emily Brontë. But you can see how her prose resembles those pre-Coco dresses. It feels heavy (what I've included here is only half of the first paragraph). You can't wear it in a modern city. It would get caught in the door of the bus. It would (to be more precise) sound like a caricature. I have never yet read an attempt to write nineteenth-century prose that didn't. Woolf's style is lighter, more modern. Now that I read it again, I can see how it's influenced me. I mean, it's all over "Pip and the Fairies," in which I skip between the past and present and even future based on what my protagonist is thinking about.

(Of course, Child, Chanel, and Woolf did not change things by themselves. No one ever does. But they were important parts of changes that were taking place at the time.)

Three women who changed things. You know me by now, so you know what I'm thinking. Will I change anything? Not that I have to, necessarily. At least, not anything on such a scale. But I would like what I do to count. Three women who became themselves. What will I become?

There's only one way to find out. Start cracking eggs.

June 13, 2011

Thinking about Cassatt

I was thinking about Mary Cassatt.

Actually, I was thinking about myself, and this past year. It seems to me that something happened last summer. Something changed or began to change. And I started to see both myself and the world differently. There are a number of things that can do that to you. A work of art can. A place can. A person can. Seeing yourself through the eyes of a person who sees you differently than you see yourself: that can change you.

This year, I've been thinking of myself differently, not just as a person but also as a writer. And I've been changing both as a person and a writer. I've believed in myself more, I've dared more in my work. I'm writing things I don't think I would have written before. It's as though since last summer, I've become more myself, more the person I was supposed to be all along.

I'm taking myself more seriously.

The reason I was thinking about Mary Cassatt is that often, I use other art forms to help me think about writing. So I'll use dance to think about writing, or I'll use music or visual art. And what Cassatt did was combine innovative techniques, taken from the Impressionists and particularly from her mentor Edgar Degas, with subject matter that was not itself particularly innovative. In a way, she combined Impressionism with certain aspects of Victorian genre painting. The mother and child paintings, for example. Like this one:

So often when we think of experimental art, nowadays, we think of art that is not particularly pleasant to look at. Cassatt created an art that was aesthetically pleasing, that actually created a sense of comfort and stability, but that was nevertheless challenging because it did not idealize, the way Victorian genre painting did. Her mothers and children were particular mothers and children.

What I like about the painting above is the richness of color. She had that glorious color sense that makes walking into a room of Impressionist paintings like walking into a garden. In the Museum of Fine Arts, there is just such a room, and when you walk into it, you feel free. You think, yes, I can breathe here.

You can see that color sense in the yellows and violets in the painting above. They remind me of France. But I also like the girl's plaintiveness, which is not the plaintiveness of children in Victorian genre paintings. This child looks as though she has lost something specific. As though she is actually thinking about it. Not as though she is a representation of loss in the abstract.

In the last two pictures, the painting above and the print below, you can see how she adapted techniques from Japanese prints. They are so flat, comparatively. I like the blues and yellows, so vibrant. There is a crucial combination in these pictures that I want to think about: the aesthetic pleasure they provide, which creates that comfort I described, and yet the challenge they present. They ask you, the viewer, to find aesthetic pleasure in a different way. We can tell they presented a challenge at the time: Cassatt's paintings were repeatedly rejected at the Salon.

Some of the writers I love from that time period, Virginia Woolf, E.M. Forster, were doing the same thing. Even James Joyce was. They were creating work that provided aesthetic pleasure and yet presented a challenge. I get a certain feeling from reading them, the same feeling I get from walking into the Impressionist room at the MFA. A feeling of lightness, airiness, and yet strength. Unity and structure, yet freedom.

Honestly, the writing I've been doing recently isn't particularly challenging in that way. I think I've been focusing on beauty and aesthetic pleasure, on providing those. I want to be able to write a prose that is filled with light, the way Woolf's is. But I also want it, or at least some of it, to go to an edge. Not in the way modern art often does, but in the way Cassatt did.

How difficult it is to describe all this! And it's the last thing I can think about, right now. But since last summer, I've been feeling more and more as though I'm moving toward something, in myself, in my work. Something that is the self I'm meant to be. And I want that movement to continue.

Catching Up

My computer is back!

I can't tell you how lovely it feels to be cruising through cyberworld at my usual speed. Like something out of Blade Runner, or am I thinking of some other science fiction movie? The Fifth Element, perhaps?

I thought that I would post a few pictures I took during that time and could not upload. Just to catch up.

First, here is me on the day I relinquished my computer to IT, actually on the way there. I don't think I've ever looked so bedraggled in photographs I've uploaded here. (Well, except for ones taken first thing in the morning, or in which I had green goop on my face. But those were deliberately bedraggled.) This is me tired, frustrated, worried, on a day when I'd like to be working but on which I had to drive an hour to drop my computer off at the computer hospital.

And here are some things that cheered me up during that sad and lonely wait. First, after dropping my computer off, I went into the Boston University Barnes and Noble, and guess what I saw? Happily Ever After on the shelf, as a staff pick!

And remember when I said that I mended a tiered skirt? Well, this was the skirt. It's made of a soft, swingy brown corduroy. It has all those tiers, and some of them were coming apart just a bit, so I had to sew them back together.

And I didn't mention this, but during that time I bought two pillows. I don't usually buy things out of frustration, but this time I have to admit that it did happen. But I like the pillows. They have geraniums on them, and the colors match – well, everything else I own. Here's one behind Dani (the bear I got on my first birthday), on the mission-style chair in my room.

And finally, I didn't mention this either, but another thing I did was restring some of my pearls. In my family, girls are given pearls. I got mine when I was sixteen. Ophelia has already gotten hers. I had decided years ago that I did not like how mine were strung, so I took the strand apart but never put it back together. One night while my computer was being attended to, I sat down and restrung some of them, knotting the silk as one should between pearls, attaching a silver clasp. This is about eighteen inches, and I should have enough for another shorter strand. (I was given quite a lot of them, a long string. But I simply never wore them that way.)

No, I don't actually wear pearls around the house, especially not when I'm writing. (How can you tell I'm writing? The glasses. The hair up, out of my way.) But these had lain for a long time in a tin, and they weren't as lustrous as they should be. Pearls warm up, take on a shine, when they are next to skin. So I wore them today to get them to their usual pearliness.)

This is a nothing, an amuse-bouche of a blog post. A sorbet. So I'm going to post something else somber and serious, I promise. But I'm giddy with relief at having my responsive instrument back, on which I can type so quickly, which is such a part of my life.

Thank you, computer doctors!

June 12, 2011

A Sense of Discontent

I've stopped coughing, but I'm still very tired – the aftermath of the Coughing Plague, I think. Nevertheless, today I wanted to go to the Museum of Fine Arts, mostly for a banana split but I do also like those pictures and things they have hanging on the walls. So we went.

I can't show you any photographs, because this computer doesn't have a program that can download them. Honestly, I feel as though I'm stuck in the technological dark ages.

After the banana split, which was a thing of beauty that is a joy for at least half an hour, I focused on two exhibits. The first was Scaasi: American Couturier. There were two exhibits related to fashion that I wanted to see this summer. The first was the Isabella de Borchgrave exhibit I described in earlier blog posts, but it was too early in the summer. I couldn't make it out to San Francisco by the time the exhibit closed. The second is the Alexander McQueen exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which I'm definitely not going to miss. (New York friends, I should be there the first week of August, which is also the last week of the exhibit. New York is so much easier than San Francisco, just an inexpensive bus ride.) Because I missed Isabella de Borchgrave, it was nice to make the Scaasi exhibit, although not quite the same, not as artistically interesting. But still. (I have photos and will post them as soon as I have a twenty-first century computer and not one that runs on horsepower.)

Did you know that Arnold Scaasi was Arnold Isaacs (read Scaasi backward) when he first came to the United States? The dresses themselves were very interesting. You could see the fashions changing decade by decade, see the different silhouettes and materials. It was a useful education for a writer. I wish Genevieve Valentine had been there; I would have liked to hear her comments.

Then I went into my second exhibit, Artists Abroad: London, Paris, Venice, and Rome 1825-1925. And here I ran into a problem: my own sense of discontent. Because while Scaasi had been fun, here was real art: engravings and watercolors by Mary Cassatt, James McNeill Whistler, and their ilk. It was a small exhibit: small works (in terms of size, in terms of their importance) in a small room. But you could see, for example, how Cassatt was experimenting, how she was making these smaller works in preparation for larger ones. Experimenting with techniques. And there were two Whistler engravings that looked like no engravings I have ever seen. He had found a way to capture the sheen of light on water in an engraving, which seems like an impossible thing to do. I looked at them and thought, Whistler, you cool, crazy dude. And there were other artists I had never heard of who nevertheless belonged to the artistic ferment in those cities.

The discontent came from wanting to participate in something like that. An artistic ferment, but also more importantly artistic experimentation. Cassatt and Whistler were so clearly in the process of trying to find out what it meant to be Cassatt and Whistler. I wanted to be in the process of finding out what it meant to be me, artistically. Whether that was part of a ferment or not. (But Cassatt was deeply influenced by her milieu, as I think artists always are. And I do think I have a milieu, which consists of writers who are trying to blend what are often called fantasy and literary fiction. And that is currently in ferment.)

You know what Virginia Woolf said: five hundred pounds a year and a room of her own. I have often longed for the modern equivalent. I want to go deeply into myself, find out what it is I have to say. I don't know whether my doing so is justified or not. It may turn out that my writing is not important enough to justify that sort of immersion. That introversion and taking of time. But if I don't do it, I'm not sure that I'll ever find out. I'd like to find out what I can do, not in the rag-ends of time I seem to have nowadays, when I'm so often writing after midnight, exhausted. But in large swaths of time.

Well, all I can do right now is the work I have in front of me, finish that and then see where I come out. Where, after that's done, writing fits. But I'm working toward having the necessary space and time. Because, while I don't yet know what I can do, I think it's time I found out.

(On the way home, I read Cassatt's biography on my cellphone. It was nice to see that, even though her family was wealthy, she too had problems she had to overcome. More problems than I have, certainly – being a female artist in the nineteenth century. And I learned something useful: at one point, desperate to support herself, she decided to give up painting and move out West for a job. Luckily, she was given a commission and returned to Paris the next year. Mary Cassatt was going to give up. You know what that means, right? All of us go through the same things. Without exception.)