Theodora Goss's Blog, page 46

November 25, 2011

The Searchers

I found this quotation on Jonathan Carroll's blog:

"I am one of the searchers. There are, I believe, millions of us. We are not unhappy, but neither are we really content. We continue to explore life, hoping to uncover its ultimate secret. We continue to explore ourselves, hoping to understand. We like to walk along the beach, we are drawn by the ocean, taken by its power, its unceasing motion, its mystery and unspeakable beauty. We like forests and mountains, deserts and hidden rivers, and the lonely cities as well. Our sadness is as much a part of our lives as is our laughter. To share our sadness with one we love is perhaps as great a joy as we can know – unless it be to share our laughter. We searchers are ambitious only for life itself, for everything beautiful it can provide. Most of all we love and want to be loved. We want to live in a relationship that will not impede our wandering, nor prevent our search, nor lock us in prison walls; that will take us for what little we have to give. We do not want to prove ourselves to another or compete for love."

It comes from James Kavanaugh's There Are Men Too Gentle to Live Among Wolves, I think perhaps from the introduction? Because the book itself is a book of poetry.

Every once in a while, you come across a quotation that perfectly expresses what you think, who you are. And this quotation does that for me. I feel as though I'm one of the searchers. There have been times this year when I've been deeply unhappy, but for most of my life I've been relatively happy – although not, as Kavanaugh points out, content. Because I've always wanted something more than what I've had. I've always wanted to experience the magic of the world, and I feel as though for most of my life, it's eluded me. I've seen it only in glimpses.

I've seen it sometimes while walking by the ocean, which is magical for me. I've seen it in apple orchards, or on mountains when they are covered with mist. I've seen it walking through cities at night. And I think in the end, that's what I'm ambitious for: life itself. To experience it fully. There is a way of going deeply into life. You can do it by sitting quietly in a garden. You can do it by creating something, a story or a work of art. You can do it by dancing. You can do it by seeing people at night, passing you on city streets. There are all sorts of ways.

And yes, in the end you want someone who can share that with you. Someone whose love will not be a prison, because love can be a prison. It can be the strongest prison, because it can convince you to lock yourself into a life in which you're no longer searching, in which you're not pursuing the life you imagined for yourself. In which you give up your art, your participation in the larger life of the world. If you're one of the searchers, you need a love that is also freedom. (Because love can free you. Loving and being loved is one way to be free.)

I'm not sure why this picture reminds me of the quotation, but it does:

It's called "Abysm of Time," and it's by Edmund Dulac, from his illustrations for The Tempest. I suppose it reminds me of the quotation because Miranda is a searcher herself, wanting to understand life, waiting for love. Sitting by the ocean. And of course she has red hair, like me, and she's wearing a dress I would love to wear myself.

Today I slept a lot, and I read and read, and then I did some work I needed to do. Dull, not particularly interesting work. But through it all I was thinking, and what I was thinking is that at this point in my life, I am more of a searcher than ever before. I want even more to find the secrets of life (because I believe that life has many secrets), to live as fully as I can.

This past year was for transformation. I emerged from it a different person than I was when it started. This next year is for starting to live as fully as possible, for learning how to do that. For searching.

November 24, 2011

Writing Poetry Again

I've started writing poetry again.

It's a struggle. I'm not sure why it's such a struggle for me now. I think it's partly because I've been writing so many other things, and somehow I've lost the rhythm. There was a time when I could sit down with a pad of paper and something would come out. Not necessarily something good, but the rhythm of it would be there. But writing a dissertation, and then writing a lot of prose, put you into a different frame of mind. You tend to lose the rhythm. Or perhaps it's just me, perhaps I've lost that sense for it lately.

What I do know is that I haven't written poetry for a long time. And now I'm trying to put together a poetry collection, and thinking about what works and why. And I want to write more poetry, and I'm trying to figure out how.

So there it is.

Earlier this week I started two poems, both of which I finished today. I'm going to include one of them below. I think that what I want to write now is not something finished, polished, perfect. But something broken, almost fragmentary that nevertheless has some power. I don't know if that makes any sense. I have a sort of instinct for where I want to go, but it's difficult to explain.

Anyway, here it is.

Autumn's Song

You are not alone.

If they could, the oaks would bend down to take your hands,

bowing and saying, Lady, come dance with us.

The elder bushes would offer their berries to hang

from your ears or around your neck.

The wild clematis known as Traveler's Joy

would give you its star-shaped blossoms for your crown.

And the maples would offer their leaves,

russet and amber and gold,

for your ball gown.

The wild geese flying south would call to you, Lady,

we will tell your sister, Summer, that you are well.

You would reply, Yes, bring her this news –

the world is old, old, yet we have friends.

The squirrels gathering nuts, the garnet hips

of the wild roses, the birches with their white bark.

You would dress yourself in mist and early frost

to tread the autumn dances – the dance of fire

and fallen leaves, the expectation of snow.

And when your sister Winter pays a visit,

You would give her tea in a ceramic cup,

bread and honey on a wooden plate.

You would nod, as women do, and tell each other,

The world is more magical than we know.

You are not alone.

Listen: the pines are whispering their love,

and the sky herself, gray and low, bends down

to kiss you on both cheeks. Daughter, she says,

I am always with you. Listen: my winds are singing

autumn's song.

It's Thanksgiving day, and I've been spending a lot of time reading and resting, for which I am grateful. And I ate my share and more of turkey, mashed potatoes, candied yams, cranberry relish, bread stuffing, peas, and gravy. I'm thankful for all that, but also for the fact that I'm writing – and going back to some things I haven't done for a long time. I think I'm still in the recovery process from this long, long year. Trying to find myself again. And writing poetry is part of that process.

November 23, 2011

Anne McCaffrey

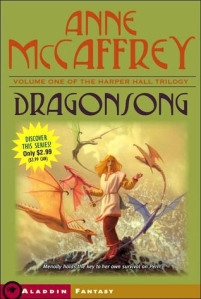

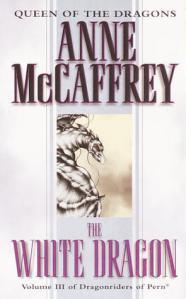

I was so sad to hear that Anne McCaffrey had died.

I first read the news on GalleyCat, a blog about the publishing industry. Here is the obituary. The obituary reprints this advice from her blog:

"First – keep reading. Writers are readers. Writers are also people who can't not write. Second, follow Heinlein's rules for getting published: 1. Write it. 2. Finish it. 3. Send it out. 4. Keep sending it out until someone sends you a check. There are variations on that, but that's basically what works."

Which I think is good basic advice for all of us. It's certainly what she did. To tell you why I was so sad, I have to tell you a bit about my childhood. It won't surprise you, I'm sure, to learn that I was an inveterate nerd. In school I always felt like an outsider, partly because I liked to read when other children didn't, and partly because I couldn't for the life of me kick a ball. It would go off in the wrong direction. My family moved around a lot, and so I went to a lot of different schools. In sixth grade, I went to a school where the crucial social skill was playing kickball. I was hopeless.

That year, my best friend was named Amy. She was as much of a nerd as I was. I'm not sure which Anne McCaffrey book I read first. I think it may have been The White Dragon. But I was immediately hooked on Pern. I particularly liked the Harper Hall books, with Menolly. Her heros and heroines, like Jaxom and Menolly and Piemur, were outsiders as well. I could relate to them and to all their troubles. And of course I loved the dragons and fire lizards. What would I have given to have a fire lizard of my own? My soul, probably. Amy and I would swing on the swings near my house and talk about what it would be like if somehow, by accident, a dragon from Pern went between and ended up in a nearby field, and took us to Pern. Where we could be dragonriders, of course, and there was a particular dragonrider we were in love with, but I don't remember his name.

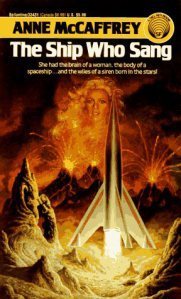

I read a number of her books around that time, when I was twelve or thirteen. I remember The Ship Who Sang in particular, because it was a love story and a story about a woman who discovers her individuality and vocation. McCaffrey had female characters I could relate to. They were strong, flawed, but ultimately heroic. It was quite a change from Middle Earth and Narnia, where adult women are mostly absent or evil. I couldn't imagine growing up to be the White Witch or Galadriel, but I could imagine growing up to be Lessa.

The other fantasy writer who influenced me deeply around this time was Ursula Le Guin, so I was influenced by two important female fantasy writers. Now that I think about it, Le Guin didn't have those sorts of compelling female characters. I ask myself if that can be right, because I generally think of Le Guin as a strong feminist. But the character I remember most from her books is Ged. He's the one who comes most alive for me.

From McCaffrey, I think I got my love of story. From Le Guin, I think I got my love for words and their power. Le Guin was the superior stylist. But McCaffrey had something that I think is important. Many years later, when I was in the middle of my PhD program and inclined to dismiss writers like McCaffrey as inferior to the literary writers I was reading, I decided to reread one of the Harper Hall books. At the time, I lived in an apartment with a claw-foot bathtub, and every night I took a long bubble bath. With a LOT of bubbles and a good book. I made the mistake of starting the book in the bathtub. An hour later, I was sitting in a cold bath, with no bubbles, unable to stop reading. I could see all the problems with her world – the aristocratic system was based on the work of "drudges" (yes, they were called that) who were barely characters at all. Lessa was a drudge, but like Cinderella, she was really the dispossessed heiress, so of course she would eventually regain her proper social role. So there was quite a bit to criticize – and yet, the woman could write a gripping story.

She had courage, too. After her divorce, she moved with her children to Ireland, living off child support payments and what she could earn by writing. I wish she hadn't collaborated so much, and those collaborations aren't novels I would read. But I will never judge another writer for how he or she makes money from writing. It's just too hard of a profession to say, you shouldn't have written that. She supported herself and her children, and that's heroic.

I want to write another time about her novels, about what I think of them now, how they've influenced me. But this post is already long enough, and all I really want to say here is, Ms. McCaffrey, you were such an important part of my childhood, and part of the reason that I'm now a writer. I'm so sorry that you're gone, but so glad that you were here for a while, and that you wrote your books. Thank you.

November 22, 2011

Reading Coelho

I've been sad today.

Several years ago, a friend of mine introduced me to an aspiring writer. I heard, afterward, that he'd had a play produced. Every once in a while, my friend would tell me that the writer was following my career, glad that it looked as though I was doing well. I never actually knew him, but I heard news of him from my friend. Yesterday, I learned that he had committed suicide. It took a week for people to realized what had happened. (Sometimes, he would stop answering emails and the telephone for a week or two. So people weren't worried that he wasn't getting back to them.)

I didn't really know him, as I said, but somehow I've been thinking about him all day. My friend has organized a tea in his honor, and so far over a hundred people are planning to go. It's funny how you can feel lonely even though over a hundred people want to remember and celebrate your life.

Today, I went into the bookstore and picked up Paul Coelho's The Alchemist. It's part of my ongoing research into being a writer. It's such a popular book, and I want to understand why.

I haven't started the book yet, but I did read the introduction. I'm going to post a few excerpts here.

" . . . we all need to be aware of our personal calling. What is a personal calling? It is God's blessing, it is the path that God chose for you here on Earth. Whenever we do something that fills us with enthusiasm, we are following our legend. However, we don't all have the courage to confront our own dream."

(I should make clear here that to me, God translates as whatever power there is in the universe that directs our ends, that has a purpose for us. I believe there is such a power, and that we can call it whatever we like, and that it's immanent in nature rather than separate from it. I want to make that clear because God is such a loaded term, loaded with two thousand years of history and controversy. And what I'm talking about is completely separate from religious doctrines, which are created by human beings. So when Coelho says God, that's what I mean by the term, which may be completely different from what he means.)

He says there are four obstacles to following our personal calling.

"First: we are told from childhood onward that everything we want to do is impossible." I remember being told that I would never be a great writer because English was not my first language. And I remember having the general sense that being a great writer was impossible – that great writers were geniuses, and of course I wasn't one of those, so why write? I mean, I wasn't going to be Hemingway.

The second obstacle is love: "We know what we want to do, but are afraid of hurting those around us by abandoning everything in order to pursue our dream." Coelho goes on to say that we eventually realize "that those who genuinely wish us well want us to be happy and are prepared to accompany us on that journey." You know what? I think that's overly optimistic. Often it's the people who love us most who sabotage us, because they love us and want use to be safe and comfortable. Following a personal calling is likely to make us unsafe, uncomfortable.

The third obstacle is "fear of the defeats we will meet on the path." Here Coelho says something very useful: "The secret of life, though, is to fall seven times and to get up eight times." He also says that we "must be prepared to have patience in difficult times and to know that the Universe is conspiring in our favor, even though we may not understand how."

And he talks about why it's important to follow a personal calling: "Because, once we have overcome the defeats – and we always do – we are filled by a greater sense of euphoria and confidence. In the silence of our hearts, we know that we are proving ourselves worthy of the miracle of life. Each day, every hour, is part of the good fight. We start to live with enthusiasm and pleasure." Which I think is true. He also says, "Intense, unexpected suffering passes more quickly than suffering that is apparently bearable; the latter goes on for years and, without our noticing, eats away at our soul, until, one day, we are no longer able to free ourselves from the bitterness and it stays with us for the rest of our lives."

I think what he means by that last statement is that the suffering you endure while trying to follow your personal calling is more bearable than the suffering of not following it, of choosing to be comfortable, doing what other people tell you to do, but knowing that you're not doing what you're supposed to.

He says, "Having disinterred our dream, having used the power of love to nurture it and spent many years living with the scars, we suddenly notice that what we always wanted is there, waiting for us, perhaps the very next day." This is the part that made me think of the writer I mentioned at the beginning of this post. You have to keep waiting for the next day. I understand, very well, how it can become too hard. But that's the key, isn't it? To wait for the next day and see what it will bring. Because it will probably, at least, bring something different.

The fourth obstacle is "the fear of realizing the dream for which we fought all our lives." Because we think we are unworthy of it, because we feel a sense of guilt about our achievement. As though we did not deserve it. He says, "This is the most dangerous of the obstacles because it has a kind of saintly aura about it: renouncing joy and conquest. But if you believe yourself worthy of the thing you fought so hard to get, then you become an instrument of God, you help the Soul of the World, and you understand why you are here."

I don't think I've made it to the fourth obstacle yet! But I do feel as though I've fought the other three. And the fight is never over, because you encounter those obstacles over and over again. You always return to doubt, guilt, fear. You're always confronted with them.

This has been a rather dramatic blog post, hasn't it? I didn't mean it to be. But it's difficult to talk about a death, particularly that kind of death, without becoming dramatic. Without making a vow that you will overcome the obstacles, follow the dream that seems to keep calling you onward.

November 21, 2011

Extraordinary Lives

Today, I read an article titled "The Unleashed Mind: Why Creative People are Eccentric." I've linked to a preview of it on Scientific American. Here is the abstract:

"People who are highly creative often have odd thoughts and behaviors – and vice versa.

"Both creativity and eccentricity may be the result of genetic variations that increase cognitive disinhibition – the brain's failure to filter out extraneous information.

"When unfiltered information reaches conscious awareness in the brains of people who are highly intelligent and can process this information without being overwhelmed, it may lead to exceptional insights and sensations."

That seems intuitively right to me. I think it's fair to assume that I would test highly for creativity on the sorts of tests the article mentions (I mean, I am a professional writer). And I know that I test highly for intelligence (since I was tested for the school gifted program, and let me just say that I think there are a lot more important things in this world than scores on an IQ test). And I do think I'm eccentric, although I've learned a series of social conventions, as we all have. And I generally follow them, although I think I'm more aware, than most people, of their constructedness.

But cognitive disinhibition: I know exactly what the article is talking about. It's that sense of having one layer of skin fewer than most people. Of being extraordinarily sensitive to incoming stimuli, whether it's ideas, music, even the weather. It makes life just that little bit more challenging.

On the other hand, it can also lead to exceptional insights and sensations.

What I wanted to talk about today were people with extraordinary lives, but I think you could classify them as exceptionally creative people as well.

Two days ago, I watched a PBS documentary called My Life as a Turkey. (You can watch the full documentary by following the link.) Here is a description:

"After a local farmer left a bowl of eggs on Joe Hutto's front porch, his life was forever changed. Hutto, possessing a broad background in the natural sciences and an interest in imprinting young animals, incubated the eggs and waited for them to hatch. As the chicks emerged from their shells, they locked eyes with an unusual but dedicated mother. One man's remarkable experience of raising a group of wild turkey hatchlings to adulthood."

Hutto is a wildlife artist who routinely lives with wild animals. The footage in the documentary is amazing, and the access he got to wildlife, to a wild life, is amazing as well. It's as though he was given the key to a kingdom that most of us will never enter. He saw things most of us will never see.

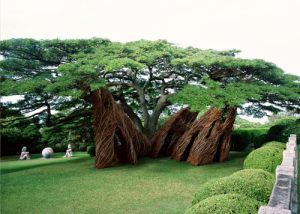

I'm not sure why, but he reminded me of one of my favorite artists, Patrick Dougherty, who creates art that looks like this:

Hutto and Dougherty are both creative, eccentric people. (Who spends a year in the company of wild turkeys? Who builds houses out of sticks?) They both live extraordinary, although very different, lives. (Hutto lives with wild animals. Dougherty travels to museums and public spaces all over the world to create his art.)

I think you only do the sorts of things they do because you feel compelled – you feel as though you have to do it, that doing it fulfills some deep and fundamental desire within you. It's the feeling that you're doing the thing for which you were made – and that feeling creates a sense of happiness, of joy.

The article says that people who are highly creative are more prone to magical thinking, and I think that's true as well. What I just wrote is an example of magical thinking, because I actually believe in it: I actually believe that the universe calls us (maybe not all of us, I don't know, but at least some of us) to do something, and if we do that thing, that's when we are happy. And that's when we can bear with all the negative things – pain and loneliness and all the things creative people are prone to. (That we are all prone to, but that creative people often feel most acutely.) When they are in the service of a higher goal.

I don't know if I've had an extraordinary life so far. It's been unusual, certainly. But I am at least aiming to do some extraordinary things. Like, you know, write stories that people will want to read, that they will relate to.

November 20, 2011

Pater vs. Wilde

I know that I haven't been updating regularly. I can't absolutely promise that I will do so, but I'm going to try, because this is important to me. I want to try to write at least 500 words a day on this blog. It's for myself, really, because if I don't write out my thoughts, it's as though they get all blocked up, and that's not good for me. I need to keep them flowing.

You might be pleased to hear that I'm working on a new story. It's called "Estella Saves the Village," and so far I have about 3500 words written. I think it's going to be about another 1500.

I'm getting to a place with my writing – it's an interesting place, and I'm not entirely sure how to describe it. It's a place where when I write, I feel as though I'm doing so with clarity and precision. The way I want to do dance steps. No vague steps, no steps that signal indecision, as though I'm not sure where to go. When I write, I want nothing extra. Nothing pretty simply for the sake of prettiness. In a review, the reviewer will often take a sentence, or a couple of sentences, out of context. Simply to show how pretty the writing is. That's not what I want.

My favorite writers have that clarity and precision: E.M. Forster, for example. Willa Cather. That's what I'm looking for.

But I wasn't going to write about my own work today. Instead, I was going to focus on the two writers I've been teaching this week: Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde.

We've been looking at Pater's Conclusion to Studies in the History of the Renaissance, which I think everyone should read and reread. This is the conclusion to the conclusion:

"One of the most beautiful passages of Rousseau is that in the sixth book of the Confessions, where he describes the awakening in him of the literary sense. An undefinable taint of death had clung always about him, and now in early manhood he believed himself smitten by mortal disease. He asked himself how he might make as much as possible of the interval that remained; and he was not biassed by anything in his previous life when he decided that it must be by intellectual excitement, which he found just then in the clear, fresh writings of Voltaire. Well! we are all condamnés, as Victor Hugo says: we are all under sentence of death but with a sort of indefinite reprieve – les hommes sont tous condamnés mort avec des sursis indéfinis: we have an interval, and then our place knows us no more. Some spend this interval in listlessness, some in high passions, the wisest, at least among 'the children of this world,' in art and song. For our one chance lies in expanding that interval, in getting as many pulsations as possible into the given time. Great passions may give us this quickened sense of life, ecstasy and sorrow of love, the various forms of enthusiastic activity, disinterested or otherwise, which come naturally to many of us. Only be sure it is passion – that it does yield you this fruit of a quickened, multiplied consciousness. Of such wisdom, the poetic passion, the desire of beauty, the love of art for its own sake, has most. For art comes to you proposing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moments' sake."

What Pater says, in brief, is that our lives are brief, and to make of them the most we can, we should experience all we can. How to do that? How to compress the most and best experiences into the given time, into a finite number of pulses? Art, Pater tells us. Because art gives us the most, the highest, experiences.

Wilde was deeply influenced by Pater, and The Picture of Dorian Gray is, in a sense, an experiment in Paterianism, with Wilde's usual tongue in cheek.

On Friday, I asked my students, would you rather be Wilde or Pater? I was startled when they said Wilde. Because after all, Wilde went to prison for two years. He suffered terribly. He also created art so much greater than Pater's that even comparing them is a silly exercise. But to my students, Wilde had experienced more. He had truly lived, while Pater had spent a life being comfortably intellectual. Never giving in to his desires as openly as Wilde did, although we do have evidence now of at least one romance with an Oxford undergraduate.

I was startled because having a life like Wilde's is so, so hard. To live fully, to mock society openly, to allow yourself to become an object of ridicule in your pursuit of what you believe to be the beautiful and true. Wilde suffered. Why would anyone want to suffer like that? (Honestly, I'm not sure my students realize, yet, what living that sort of life entails.)

There's really only one reason to do so – when you can't help it, when everything you are draws you to a life that is extraordinary, rather than containing ordinary peace and pleasures. When you can't make any other choice. Wilde could not have chosen to not be Wilde.

I think choosing the life of a serious artist always entails some degree of suffering. (Serious is a key word here.) It's not a comfortable life, and the only reason to choose it is that you really have no choice in the matter.

November 16, 2011

Author Photos

It's been a long day, and I have absolutely no energy to write a blog post tonight. So I'm just going to write quickly about author photos. I need to get some – every author needs photos. But I haven't had time to get professional photos taken. So instead, to a recent request, I've sent the following.

The first three are informal.

The next three are more formal.

These are the raw, untouched photos. No cropping, no photoshop.

Once, I heard a woman – a not particularly nice woman – call writers narcissists because they did things like blog, post pictures of themselves. It made me want to laugh hysterically. She had no idea how difficult it is, for people as introverted as most writers are, to do those sorts of things. I wanted to tell her, you follow this profession and see whether you can handle it! (There are things I avoid, although I shouldn't. Signings, unless I have a book just out, are one of them. That's probably not a smart thing for a writer to do.) Being so public makes you hyperaware of all your flaws.

I also wanted to tell her, where do you think the books you read come from? Writers who do these sorts of things to make sure their books are read. Because if you're a writer and you don't have an online presence, and you're not J.D. Salinger, you're going to pass under the radar. I've seen it happen to several of my friends, wonderful writers who don't get the attention or readership they deserve.

So there you go, that's my blog post for today: pictures, and a minor rant. I'll probably post them on my Press page, temporarily. But it's time to call a photographer and get real ones taken. I think I'm at that place, as a writer. (I probably was some time ago.)

Yes, this publicity thing is hard, when you're an introvert . . .

November 15, 2011

Going to London

I think I need to go to London. As you know, I've been very tired recently. I'm still catching up on all the work I got behind on because of the defense. So I've been reading, just a little, as I have time: The Ruby in the Smoke by Phillip Pullman.

(Except mine has a better cover.) I like it a lot – I just finished it today on the T, headed to Brookline for an appointment. It's not as rich as the Dark Materials series, not as complex or intellectual, but it's more fun. And although I've never been to nineteenth-century London, it gives me an excellent idea of what it would be like.

That's what I need to do with The Mad Scientist's Daughter: I need not only to research nineteenth-century London, but to go to London, imagine what nineteenth-century London would have looked like. Get a sense for the geography. How long it would take to travel from place to place, walking or by horse-drawn cab. I want my book to have that sense of deep reality, which many historical books don't seem to have. But Pullman's certainly do.

So the question is, how to get to London? Earlier today, I tweeted about it, and a friend has already offered me a place to stay that I believe is within walking distance of the British Library. And now I need to think about the travel expenses. I may already be in Budapest this summer, so it would be a matter of getting from Budapest to London. The cheapest way would probably be to fly.

It's exciting to think about this, because I've never been to London, and I haven't been to Europe in – two years, I think. Which I suppose is not that long for most people, but I was born there, and it feels long to me. This is the sort of thing I could do, now that the dissertation is done. The sort of thing I could never do before, because I had to spend the summers writing. And once I'm in England, there are plenty of friends to visit.

Oh, I don't know if it will actually work out, but I do know that I want to go, and that all it will take, now that I'm done with the dissertation, is some planning.

(There's one place in The Ruby and the Smoke where I thought, you know, even if I'm writing for young adults, I can write about anything. It was at the beginning of Chapter 11, the second paragraph: "She woke just after dawn. The sky was clear and blue; all the horrors of opium and murder seemed to have vanished with the night, and she felt lighthearted and confident." If Pullman can write about opium and murder, well then, I can write about anything, can't I?)

November 14, 2011

Christopher Raven

Today's post is going to be about a few things I have coming out, so I hope you don't mind some self-promotion.

First, my story "Christopher Raven" came out in Fantasy Magazine today. There's also an interview with me about how I wrote the story.

If you like the story, consider buying the anthology it's in, Ghosts by Gaslight.

Second, one of my favorite people, Charles Tan, has put together a list of "Short Story Collections for the Aspiring Speculative Fiction Writer." And he's included In the Forest of Forgetting! The other books on the list are as follows:

Magic for Beginners by Kelly Link

The Girl in the Flammable Skirt by Aimee Bender

The Elephant Vanishes by Haruki Murakami

The Fantasy Writer's Assistant and Other Stories by Jeffrey Ford

In the Mean Time by Paul Tremblay

Objects of Worship by Claude Lalumière

Twelve Collections and The Teashop by Zoran Živković

After the Apocalypse by Maureen F. McHugh

Yellowcake by Margo Lanagan

Honestly, it's amazing to be included in a list with such wonderful writers.

And finally, I have a story being reprinted in what looks like it's going to be a great anthology, Witches: Wicked, Wild & Wonderful. Here's the cover:

And here's a description and the table of contents, including my story, "Lessons with Miss Gray."

Surrounded by the aura of magic, witches have captured our imaginations for millenia and fascinate us now more than ever. No longer confined to the image of a hexing old crone, witches can be kindly healers and protectors, tough modern urban heroines, holders of forbidden knowledge, sweetly domestic spellcasters, darkly domineering, sexy enchantresses, ancient sorceresses, modern Wiccans, empowered or persecuted, possessors of supernatural abilities that can be used for good or evil – or perhaps only perceived as such. Welcome to the world of witchery in many guises: wicked, wild, and wonderful. Includes two original, never-published stories.

"The Cold Blacksmith" by Elizabeth Bear

"The Ground Whereon She Stands" by Lean Bobet

"The Witch's Headstone" by Neil Gaiman

"Lessons with Miss Gray" by Theodora Goss

"The Only Way to Fly" byNancy Holder

"Basement Magic" by Ellen Klages

"Nightside" by Mercedes Lackey

"April in Paris" by Ursula K. Le Guin

"The Goosle" by Margo Lanagan

"Mirage and Magia" by Tanith Lee

"Poor Little Saturday" by Madeleine L'Engle

"Catskin" by Kelly Link

"Bloodlines" by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

"The Way Wind" by Andre Norton

"Skin Deep" by Richard Parks

"Ill Met in Ulthar" by T.A. Pratt (original)

"Marlboros & Magic" by Linda Robertson (original)

"Walpurgis Afternoon" by Delia Sherman

"The World Is Cruel, My Daughter" by Cory Skerry

"The Robbery" by Cynthia Ward

"Afterward" by Don Webb

"Magic Carpets" by Leslie What

"Boris Chernevsky's Hands" by Jane Yolen

This is a book I'd buy anyway, because I love stories about witches. So, in case you want to read any stories by me, "Christopher Raven" is online now, and "Lessons with Miss Gray" is coming out again, and of course you can always just order yourself a copy of In the Forest of Forgetting. Because, you know, Charles said so!

November 12, 2011

Readability

I meant to write a blog post earlier, but I became fascinated by a documentary on the dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones. It was about his creation of a dance based on the life and impact of Abraham Lincoln. If you want to see what a magnificent dancer he is, here is a YouTube segment that will give you at least a sense for how he moves.

But what fascinated me about the documentary is what always fascinates me about those sorts of things: seeing an artist work. And Jones is an artist with a capital A, brought up on modernism and its sense of the centrality of art and the artist. (The segment will demonstrate, also, something I've always believed: that dancers are the most beautiful people. Jones is sixteen years older than I am, and I could never hope to have a body as strong, as limber, as beautiful as his.)

The dance he was choreographing was particularly important because he wanted it to be accessible for a general audience, while not insulting the sort of intellectual audience that usually goes to see modern dance.

And that's really my subject for today, because I've been reading Stories, edited by Neil Gaiman and Al Sarrantonio.

And I've noticed something: certain writers are remarkably readable. They just keep you reading. You know what I mean, right? The Harry Potter series are remarkably readable. The Steig Larsson novels are as well. Readability does not mean a novel is great literature. But it's an important quality to think about.

So I've been looking at these stories in terms of their readability. Gaiman himself is always remarkably readable, and I read "The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountains" in one sitting. I liked how it was structured, the twists and turns. Michael Swanwick's "Goblin Lake" was readable and humorous. Elizabeth Hand's "The Maiden Flight of McCauley's Bellerophon" was readable and classic Hand, meaning simple on one level and intensely complicated on another. And beautiful, and a joy to read. But I expect that from her. I haven't read many of the other stories, but I'll confess that I could not get through Joyce Carol Oates' "Fossil-Figures" (it just kept going on and on, so I skipped to the end), and I'm in the middle of Walter Mosley's "Juvenal Nyx" and may end up doing the same thing because it's a vampire story and it too keeps going on and on, as though the technical aspects of life as a vampire were interesting. But Mosley is also a readable writer, as anyone who has read his detective stories knows.

I also recently read "Covehithe" by China Miéville, which is lovely in the way Miéville often is at his best, which is that he turns the grotesque into the lovely. (Who else could give me a vision of oil rigs mating under the sea?) And he, too, is a readable writer. At least in Un Lun Dun and The City and the City, although I confess that I became bogged down in Perdido Street Station.

I know, readability is a strange word to use, because technically all writers should be readable – I mean, we read them. But what I mean is having a sort of narrative pull. This is important to me because I want my writing to have that, to pull the reader along. I want it to be remarkably readable, for the reading experience itself to be a pleasure. (Remember, it doesn't have to be. There are important writers whose writing is not particularly readable in that sense. Whose writing you have to work at.) I honestly don't know if my writing has that – I think it does in my best stories, and it's something I want to work on.

Maybe accessibility is another way to look at it – like the dance on Lincoln, I want my writing to be accessible to everyone, but not to insult an intellectual reader. If that's possible.

I've been thinking a lot about issues like this, reading consciously. Because now that my dissertation is done, I want to be the writer I can become. And I'm not sure what that is yet, exactly.