Theodora Goss's Blog, page 43

December 30, 2011

Doing Publicity

Yesterday, I made a mistake: I drank coffee. But it was so delicious, a Starbucks skinny peppermint mocha, that I couldn't help it. All right, I could have helped it. Either way, I could not get to sleep until 4:00 a.m., which gave me plenty of time to work on "Blanchefleur" (the story I'm writing right now). But this afternoon I was so tired that I fell into a deep sleep, and when I woke up I was so dazed that I drank water the wrong way. The way where you get it all over your chin. Trust me, I've tried it and it doesn't work. (You can still try it yourself, of course. I'm just saying.)

So anyway, this post is about doing publicity.

I'm not very good at doing publicity. As I've mentioned before, I'm introverted and hypersensitive, which basically means that I tend to be overwhelmed by both physical and mental stimuli before people who aren't those things (physical stimuli = anything sensory, such as noise or smells; mental stimuli = stress). I'm in a profession with high levels of both those things. So into my daily routine, I incorporate moments of rest, moments of silence. Reading is highly restful for me, as is writing: I can escape into writing, as though into my own country.

Although writing is restful, publicizing your writing is stressful, whether it's online or in person. (I love conventions, but especially at conventions I need to find quiet spaces. I love the noise and the bustle, and even the stress of it for a while – but after that while I need to lie down in a dark room.) But you have to do publicity. If you want a writing career nowadays – and I don't mean if you want to write, because all that takes is writing, but if you want a writing career – you do need to be willing to publicize your work. So what do you do?

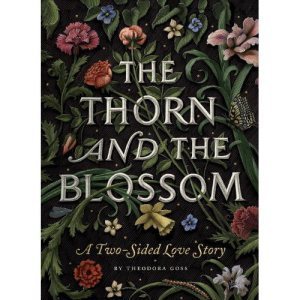

Well, I have a book coming out in January. (Have you heard? As though I haven't mentioned it enough!) It looks like this:

And it works like this:

So I'm trying to make sure that people hear about it. Of course, in the grand scheme of things there's not a lot I can do: the publisher has a publicity department, and the people there know so much more about this than I do, and are so much better than I am. But I want to do what I can, in part because I care about this book, as I care about all my stories and poems – I feel almost as though they were my children (the children of my mind and heart), and I don't want to simply sent them into the world without support.

So what to do? Well, first, you'll see a new page on this website, listed in the menu above: Novels. I'm considering The Thorn and the Blossom my first novel, and on that page I'll have information about the book. I'll also be writing about the book on this blog – about how I wrote it, what I was thinking at the time.

Second, I've already posted this on Facebook and tweeted about it on Twitter, but I'll mention it here as well: if you're a blogger and you'd like a review copy, send me your address and URL, and I'll try to get you one. (You can contact me on Facebook or Twitter, or simply by email: tgoss@bu.edu.) And I'll probably link to and quote from reviews here.

Third, once the book is out, I'll remind people that if they do decide to read it, they can review it on the book's Amazon or Goodreads pages. Even if you don't have a platform like a blog, you can offer your opinion. Or, you know, you can just rate it. Or even just press "like." (Well, assuming you like it, of course!) Those are all ways of getting the word out.

Oh, and by the way, I've been updating my Amazon Author Page. Feel free to "like" that too (but only, you know, if you actually do!).

(This is for writers, but did you know that if you have a story in an anthology and you're listed in the table of contents, you need to tell Amazon so you're listed as an author? It's not done automatically. This is the sort of thing writers need to know when they're starting out, because they often start with short stories, and it can look as though they haven't written anything when in fact they've been published and reprinted in a number of places.)

And then there will be the more personal things, like readings. Soon, I'll be posting where you can see me in 2012, but it will certainly include Boskone, the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts, Readercon, and the World Fantasy Convention. And at least some readings around Boston . . . I'll post a more complete schedule.

It sounds kind of exhausting, doesn't it? There are things I love about it, because I do genuinely love talking to people. (I don't blog, or use Facebook or Twitter, because I want to publicize myself or my work. I do it because I want and need to maintain a connection with people, including friends of mine who are so far away, and people I barely know who are nevertheless fascinating and brave and kind.) But honestly, I don't love it as much as I loved being awake last night at 3 a.m., with Ivan (called the Idiot) in the castle of the Lady of Cats.

December 29, 2011

The Holographic Universe

I've always had a weird relationship with reality. Part of it comes, I suppose, from having an especially vivid imagination. When I wake up in the morning, if I've had especially vivid dreams, it often takes me a moment to reestablish that the real world, or what we call the real world, actually exists. (It's often a relief, actually.)

When I read about scientific theories, I have a tendency to ask myself, not whether they are true, but whether they are interesting and useful. So, for example, I find Sigmund Freud's theories of the human mind incredibly useful for analyzing literature, but reading the case history he recorded in Dora: Fragments of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria destroyed any belief I might have had in his ability to understand an actual human mind. It was so obvious to me that, in Dora's case, he was simply making stuff up (and ignoring evidence of actual underlying abuse).

I've been very interested recently by the strange experiments being done in physics. I love the idea of quantum entanglement, which seems to confirm in some way my fundamental instinct that the universe is much stranger than we think. And recently I came across the theory of the holographic universe. (I think I followed a facebook link to an article that led me to a book by Michael Talbot called The Holographic Universe: The Revolutionary Theory of Reality.)

So you know what I'm talking about, I'll quote from an article of his I found online called "The Universe as a Hologram:"

"Does Objective Reality Exist, or is the Universe a Phantasm?

"In 1982 a remarkable event took place. At the University of Paris a research team led by physicist Alain Aspect performed what may turn out to be one of the most important experiments of the 20th century. You did not hear about it on the evening news. In fact, unless you are in the habit of reading scientific journals you probably have never even heard Aspect's name, though there are some who believe his discovery may change the face of science.

"Aspect and his team discovered that under certain circumstances subatomic particles such as electrons are able to instantaneously communicate with each other regardless of the distance separating them. It doesn't matter whether they are 10 feet or 10 billion miles apart. Somehow each particle always seems to know what the other is doing. The problem with this feat is that it violates Einstein's long-held tenet that no communication can travel faster than the speed of light. Since traveling faster than the speed of light is tantamount to breaking the time barrier, this daunting prospect has caused some physicists to try to come up with elaborate ways to explain away Aspect's findings. But it has inspired others to offer even more radical explanations.

"University of London physicist David Bohm, for example, believes Aspect's findings imply that objective reality does not exist, that despite its apparent solidity the universe is at heart a phantasm, a gigantic and splendidly detailed hologram. "

That's actually inaccurate. If you read Talbot's article carefully, what you find is that a hologram is a useful metaphor for how the universe works. That's what the science actually implies. But I'm going to quote a little more:

"This insight suggested to Bohm another way of understanding Aspect's discovery. Bohm believes the reason subatomic particles are able to remain in contact with one another regardless of the distance separating them is not because they are sending some sort of mysterious signal back and forth, but because their separateness is an illusion. He argues that at some deeper level of reality such particles are not individual entities, but are actually extensions of the same fundamental something.

"To enable people to better visualize what he means, Bohm offers the following illustration. Imagine an aquarium containing a fish. Imagine also that you are unable to see the aquarium directly and your knowledge about it and what it contains comes from two television cameras, one directed at the aquarium's front and the other directed at its side. As you stare at the two television monitors, you might assume that the fish on each of the screens are separate entities. After all, because the cameras are set at different angles, each of the images will be slightly different. But as you continue to watch the two fish, you will eventually become aware that there is a certain relationship between them. When one turns, the other also makes a slightly different but corresponding turn; when one faces the front, the other always faces toward the side. If you remain unaware of the full scope of the situation, you might even conclude that the fish must be instantaneously communicating with one another, but this is clearly not the case.

"This, says Bohm, is precisely what is going on between the subatomic particles in Aspect's experiment. According to Bohm, the apparent faster-than-light connection between subatomic particles is really telling us that there is a deeper level of reality we are not privy to, a more complex dimension beyond our own that is analogous to the aquarium. And, he adds, we view objects such as subatomic particles as separate from one another because we are seeing only a portion of their reality. Such particles are not separate 'parts,' but facets of a deeper and more underlying unity that is ultimately as holographic and indivisible as the previously mentioned rose. And since everything in physical reality is comprised of these 'eidolons,' the universe is itself a projection, a hologram.

"In addition to its phantomlike nature, such a universe would possess other rather startling features. If the apparent separateness of subatomic particles is illusory, it means that at a deeper level of reality all things in the universe are infinitely interconnected.The electrons in a carbon atom in the human brain are connected to the subatomic particles that comprise every salmon that swims, every heart that beats, and every star that shimmers in the sky. Everything interpenetrates everything, and although human nature may seek to categorize and pigeonhole and subdivide, the various phenomena of the universe, all apportionments are of necessity artificial and all of nature is ultimately a seamless web."

This makes perfect sense to me, and it fits with the way I write about the world we live in. The underlying assumptions on which my writing is based are that the world is stranger than we can understand, but that it does have an underlying pattern, and that we see only part of that pattern. I think that's why Miss Emily Gray weaves in and out of my stories.

Later in the article, Talbot proposes some things that you might think go too far: for him, the theory explains things like coincidences, premonitions, etc. All the small indications we have that the universe is following laws different than the ones we learned about in school, which we tend to ignore because they make us uncomfortable. I tend to ignore them too, despite the fact that they happen to me with some frequency: dreaming about the future, for example. In a sense, what he's proposing is a sort of magical universe, or a universe in which magic can happen because the reality we think we live in is not actually the reality that exists – that underlying reality is far stranger than we can guess.

And true or not, that theory is interesting and useful. It certainly describes the universe I write about.

December 28, 2011

Unfinished Stories

Today, I was going through my files, trying to figure out what I have in them. In general, my writing files are very organized. But in both my story and poetry files, I have a folder called something like "current" or "working." And I had completely forgotten what I had in those folders. Well, as it turns out, in my story file, in that folder, I have stories that I started but never finished. A long, long time ago, because nowadays I never start a story that I don't finish. (Seriously. By the time I start a story, I have the entire trajectory in my head. So the story is always finished, always eventually published.)

I thought I would post a little bit of what I have in that folder, just the first few paragraphs of a couple of unfinished stories I have in there. What do you think, should I finish them? At this point, I would rewrite them, probably from the beginning. I'm a better writer than I used to be (at least, I hope I am). But I still remember what these stories are about, who the characters are and how the plots go.

Here they are:

Red as Blood and White as Bone

There is always a kitchen maid. Who do you think sweeps the ballroom, the morning after a ball? In poorer kingdoms, she dusts the Wicked Queen's mirror, washes the Prince's underwear. When the Princess begs to be let in, she says "We don't need your kind here" and shuts the kitchen door. But she is never, ever important.

This is not that fairy tale.

I. Black as Night

It had been raining all day, and I had been crying for at least an hour in a corner of the kitchen. Every once in a while, I would wipe my eyes and look at the cabinet where Frau Greta kept tea, sugar, anything else she thought might be stolen or eaten by mice. On its highest shelf, behind a locked door, lay the only book I had every owned, other than a Bible the Mother Superior had given me on the day I left the convent.

"Fairy tales!" Frau Greta had said, snatching it out of my hand. "So this is what you've been doing, while I've been ironing Miss Teresa's sheets! What do you think the Mother Superior would say, if I told her you were reading this trash? If she hadn't asked me herself, I would never have taken in such a careless girl. Can't you see that the meat is almost burned underneath?"

She was right, the venison roasting on a spit in the kitchen fireplace had an undercoat of black char. I had been told to turn it slowly and steadily, but watching the spit turn around and round had made me so sleepy that I had gotten the book from under my mattress, where I kept it hidden. It would do no harm to read as I turned, and anyway reading would keep me awake. I had been in the middle of "The Old Woman of the Forest." I had not heard Frau Greta coming up behind me.

"Clearly the time I've taken to teach you has been wasted. I'm going to do my duty and throw this trash into the fire, where it belongs."

"No!" I cried. "Oh, you can't! My mother gave it to me." I clutched at Frau Greta's apron and pulled, which made her tilt forward and almost fall on top of me.

"Stop that at once! Where are your manners? You're behaving like a monkey." She pulled her apron from my hands and placed the book on the top shelf of the cabinet. Then she locked the door and slipped the key into her pocket. "I'll decide what to do with your book later. You make certain that meat doesn't burn. I'm going to finish the potatoes. And I warn you, miss. I'll have my eye on you."

To Merlin, With Love

My friend,

Will you read this letter? I know so many things: that the Black Death is caused, not by exhalations from the northern marshes, as our physicians have supposed, but by the bacterium Yersina pestis. That the two-headed Worm Grimante, whose bones were discovered by Sir Bedivere, is a Tyranosaurus rex curiously entangled with a common cow. But the sun will burn itself out from its own brilliance, and this great clock, the earth, will wind down toward its final stillness, without my knowing if you have read this letter.

(Who would have thought the girl had so much poetry in her? It is the influence of our English poets. I have, over the years, spent considerable time with poets. Shakespeare, for instance. A short man, balding, fond of cats.)

But I am wandering. Toward the end, I am inclined to wander. Perhaps whatever separates the worlds begins to slip, as my mind ages. Or perhaps the old are always closer to madness.

(You will think I am mad, certainly, if you read this letter.)

One of the novices brings me breakfast. I am the only one at the convent for whom they knock, the final courtesy due a discarded queen. In the garden below my window, doves are walking along the paths, between knots of chamomile. One roosts in the apricot tree that has never yet bloomed. I could tell the sisters that it will never bloom in this English climate. But it was sent at great expense from a convent in Boulogne, and the sisters wait for it to bloom with patient pride. They would say to me, with faith in the Lord, everything is possible.

You and I place our faith in the laws of the universe. How well I remember the scientific instruments of which you were so proud! Your astrolabe, your crucibles created by the glassmakers of Venice, your dragon's egg. (If I had the time, I would describe an emu. Although it occurs to me, what do I have but time?) Perhaps that is why we understood each other, you and I. Neither of us believed in a benevolent power guiding the universe. But you never trusted me. You could never bring yourself to trust beautiful women.

A Thief in the Night

"The Latin mus, meaning mouse, comes to us from a Sanskrit word meaning to steal. The Book of Leviticus calls the mouse unclean, which we might be tempted to connect to its activity in the granaries of the Israelites. Even soldier of the Great War, who found the insulation on the wiring of their vehicles chewed by small teeth, identified the mouse as a thief."

Letitia Easton shuts the book, using her pencil as a bookmark. The eraser and the end of the yellow shaft have been chewed. Sometimes she wonders if she has begun to catch their habits, if when she does not notice her nose twitches.

It is time to feed the mice.

She puts the book beside her on the bed, which is already covered with books: The History of the Mouse in twelve volumes, Our Mutual Friend, the most recent issues of Mouse Fancy. The floor around the bed is covered with books, in piles. She should put them back on the shelves, in the paneled room her father called the library. But those shelves are occupied, and anyway she is small. She has no problem sleeping on one side of the bed.

She stands, a process that takes longer than it used to. When did her back begin to ache? Perhaps it comes of sleeping with twelve volumes beside her on the bed. Not that she sleeps much, nowadays. She lies awake in the darkness, listening to their sounds: scamper across the floors of cages, shuffle of paper, rattle of exercise wheels. She finds it soothing, like listening to the sea in a shell. Sometimes, after midnight, she wanders around the house. She does not need a flashlight, has known it since childhood. In the darkness, the silver satins shimmer like ghosts.

But now it is time to feed the mice.

December 27, 2011

Living in My Head

Sometimes it's difficult, living in my head.

Today I got an idea for a story (yes, another idea – I get story ideas all the time). It comes from two true stories, both of which affected me significantly when I first heard them.

The first story is about the man who was turning into a tree. (Do you remember? Everyone was talking about it, several years ago.) Of course he wasn't really turning into a tree. He was a fisherman from Indonesia who had a rare immune disorder. Whenever he was cut or scraped, warts would grow in that place, and they would not stop growing. His immune system could not stop them. Eventually the growths were enormous, grotesque. (I won't link to stories because the pictures are disturbing, but if you want to see for yourself, just google "man turning into tree.") He joined a freak show – it was the only sort of work he could get. When pictures began circulating, doctors became involved and he was finally treated. I don't know how he's doing now, but I hope he's doing well. There are plenty of news stories about his condition online, but there seems to be nothing about what happened to him after doctors began treating him. I suppose that wasn't as exciting. (I, for one, would like to know if he's OK.)

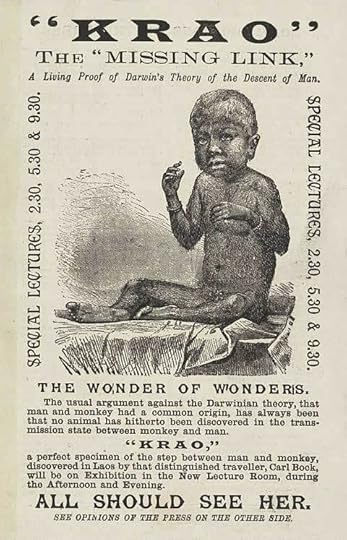

The second story is one I researched for my dissertation. It's the story of Krao, a girl from what was then known as Indochina who was brought to England and displayed as a freak. Based on pictures of her, it's obvious that she's a fairly standard "bearded lady," meaning that she has the sort of facial hair one would expect on a man. But at the time she was advertised as a Darwinian "missing link," an atavistic throwback who demonstrated the validity of evolutionary theory. She was first displayed as a child. Eventually, she grew up and married the showman who had first discovered her. She continued to perform in freak shows for the rest of her life. (I'm using the scholarly terminology here – this is how scholars who study the history of freak shows speak about the participants, as performers. Their relationships with the people who displayed them could certainly be exploitative. But some of them also exercised agency and created lives for themselves.) I can't find a photograph of Krao that isn't exploitative, but you can see from this advertisement how she was presented to the public:

Of course the advertisement is exploitative as well. The story fascinates me because of all the ways Krao was understood and presented – when of course what she was, really and truly, was a little girl, and eventually a woman. I wonder how she perceived her life, how she would tell her own story.

So what was the story idea? It was an idea about a child who has an immune disorder like the Indonesian fisherman's, in the 1860s. Like Krao, she is put in a freak show, and the man who displays her deliberately cuts and scratches her to create the effect of a tree. She is advertised as a Living Dryad. The story would be from her point of view. You see how fascinating and horrible the idea is? That's why it's worth writing about. Because the story would be about exploitation and love, about what it means to be human and perceived as monstrous.

(Why am I describing this idea rather than keeping it all to myself until I can write about it? Writers who are just starting out often worry that their ideas are going to be stolen. Well, you're welcome to steal this idea, because no matter how hard you tried, you couldn't write the story that I would write about it, any more than Earnest Hemingway could write Mrs. Dalloway. Can you imagine his version of Virginia Woolf's novel? I would of course make it as beautiful, as romantic, as possible. That's what I always do with the horrible. Because it heightens the horror.)

But can you see what an uncomfortable place it is, my head? It comes up with ideas like this one. Sometimes even I want to leave it. Tell it, come up with ideas on your own. I'm out of here. Because the ideas never stop . . .

December 26, 2011

The Poetry Notebooks

Tonight, I'm organizing the poetry notebooks.

There are three of them: Childhood-1995, 1996-2005, and 2006-Present. They're woefully disorganized. The first one is filled with handwritten scraps of paper, some of them torn out of spiral notebooks. There are some typed poems toward the end. It may seem silly to type them all up – after all, most of them will never see the light of day (if I can help it). But who knows, perhaps Ophelia will want to read them someday, and I do want to keep a record of what I've written, even if it's early, early work. (Meaning, from when I was a teenager. I think the first poems in the notebook are from high school.) The middle one is all right, although I just created new dividers, and I will probably reprint a number of the poems. There are a least a few from those years that have been published and that are worth including in a collection. The last one has to be created. I thought I'd kept better track of what I'd written, but evidently not. And that's where the bulk of the poetry I've published has come from.

I've told you that I'm cleaning up the mess, right? This is part of that process. Today I bought a cork board to go over my desk, so I can stop putting yellow stickies on the wall. And I bought my day-planner for next year. (I always get the day-planner of all day-planners, the one that lets you fill in daily, weekly, and monthly schedules.) At the moment I'm in the middle of dealing with the poetry notebooks, because if I'm going to put a poetry collection together, I may as well clean up my notebooks as well.

So today you won't get much of a blog post from me. I'm cleaning and organizing.

But I did write a poem today, and I thought I would share it. Here it is:

What Would You Think

What would you think

if I told you that I was beautiful?

That I walked through the orchards in a white cotton dress,

wearing shoes of bark.

In early morning, when mist lingered over the grass,

and the apples, red and gold, were furred with dew,

I picked one, biting into its crisp, moist flesh,

then spread my arms and looked up at the clouds,

floating high above, and the clouds looked back at me.

By the edge of a pasture I opened milkweed pods,

watching the white fluff float away on the wind.

I held up my dress and danced among the chickory

under the horses' mild, incurious gaze

and followed the stream along its meandering ways.

What would you think

if I told you that I was magical?

That I had russet hair down to the backs of my knees

and the birds stole it for their nests

because it was stronger than horsehair and softer than down.

That when the storm winds roiled,

I could still them with a word.

That when I called, the gray geese would call back

come with us, sister, and I considered rising

on my own wings and following them south.

But if not me, who would make the winter come?

Who would breathe on the windows, creating landscapes of frost,

and hang icicles from the gutters?

What would you think, daughter, if I told you

that in a dress of white wool and deerhide boots

I danced the winter in? And that in spring

dressed in white cotton lawn, wearing birchbark shoes,

I wandered among the deer and marked their fawns

with my fingertips? That I slept among the ferns?

Would you say, she is old, her mind is wandering?

Or would you say, I am beautiful, I am magical,

and go yourself to dance the seasons in?

(Look in my closet. You will find my shoes of bark.)

Right now this is just an experiment, one I'm still working on. But that's what I did today – organize, write a poem.

Oh, and you should have an illustration for it. She's not wearing birchbark shoes, but here you go: Windflowers by John William Waterhouse.

December 25, 2011

A Quiet Christmas

Perhaps I'm getting more selfish, but I decided some time ago that on holidays, I wasn't going to do anything I didn't want to. That means no long trips to see relatives. No elaborate decorating, because I don't really see the point. A Christmas tree with silver and red glass balls, ornaments of painted wood, white lace snowflakes (many of which I made myself), strings of popcorn and cranberries, with a white lace angel on top. Among the branches, small white lights twinkling like stars. Hanging from the mantle, the stockings I made. And Christmas cards on the mantle and bookshelves. Add presents under the tree, and I'm not sure what else you need. No enormous meals, just some of the treats one rarely gets during the year. Christmas morning is the one morning of the year when one can legitimately eat a chocolate Santa for breakfast, for example. (As Ophelia did this morning. Although I believe part of his torso may still be left.)

So what does one do? Read. Get some rest. It makes for a very quiet holiday.

I bought myself a Christmas present: I went to the local crafts store and had three pictures framed (a Ruth Sanderson engraving I bought at the World Fantasy Convention, a painting by Janet Chui that I bought long ago, and a limited-edition print by an artist whose name I no longer remember – I can't make out the signature – that I bought in a small gallery). And I got a present in my stocking: a certificate to get the antique slipper chair I bought reupholstered. (And some perfume and chocolate.) But at a certain point in life, you have everything you need, and you find yourself wondering how to get rid of things, rather than how to acquire more. (Of course Ophelia received many presents. But then, she's still in the process of acquiring, and can one really have too many fossils and origami kits?)

What did I do? I rested, but I also made a list for myself of the stories I'd like to write this year. The list looks like this:

Elena's Egg

England under the White Witch

A Green Thought in a Green Shade

From the Journal of Imaginary Anthropology: Cimmeria

To Merlin, with Love

Red as Blood and White as Bone

Dresses White and Shoes of Bark

Song of the South

The Music Lover

The Blue Women of Ubar/Ulan

How to Dress for the Firing Squad (Wild Rose)

Blanchefleur

I'm not sure when I'll have time to write all these stories, but today I started on "Blanchefleur," which I've been meaning to write for a long time. Next semester is going to be very, very busy, but I do want to make sure that I focus on the writing. After all, this is why I did the dissertation – so I could get to a point where I can write steadily.

I think there is a kind of selfishness inherent in the creative life. You make sure that you have time to work on your own projects, that your creative work is a priority – as much as possible. So you carve out time and resources for it. In a sense, it teaches you a valuable lesson – that it's possible to choose a quiet Christmas, that peace and comfort and joy are not only what the holiday is about, but things you can actually have. And, as important as all those, you can also have meaningful work.

Next week, I will take Ophelia to museums and parks. And I will prepare for the next semester, and try to finish one of those stories. I'm very glad this holiday was restful.

December 24, 2011

The Lion's Roar

You'd think that on Christmas Eve I would have some words of wisdom, but I don't. Except that for the first time I had Christmas pudding, and the experience was positively Dickensian. I understand why the Victorians would have loved that dense ball of fruit and sweetness, in the middle of winter when sugar and even dried fruit were probably hard to come by, but it put me to sleep for hours and hours. My stomach is still grumbling in protest.

(I'm telling it that we all have to sacrifice for historical research.)

What I really did today, when I wasn't eating Christmas pudding or putting packages (including a contract for a story I'll tell you about soon) in the mail, was think about what I want to write in the coming year. I made a list of all the stories I have ideas for, the novels I want to work on. I think I know what I want to do for the next six months. I just I hope get, or can make, the time to do it.

Several days ago, a commenter left me a link to a song on YouTube. It was "The Lion's Roar" by First Aid Kit. I thought you might like it as much as I do, and for some reason, I think it's perfect for Christmas:

And while I was on YouTube, I found another song by First Aid Kit that I particularly liked, called "I Met Up With the King":

I love how strange and oblique these songs are, how I don't understand exactly what they mean but they suggest so much. What I want in the next year is a genuine creative life, the sort of life I've been struggling to have because there was always a dissertation to write. Now, there's no dissertation to write. There's still a lot of work to get done – teaching to do, just ordinary life to live. But I'm looking forward to working on some of the projects I've put off for so long.

I think I'm hearing the lion's roar . . .

December 23, 2011

Three Sentences

This is a post about writing news. I thought you might like to know that my story "Pug," which was originally published in Asimov's, is going to be in Rich Horton's Year's Best Science Fiction and Fantasy anthology for 2012. Here's the cover and the table of contents.

"The Silver Wind" by Nina Allan

"Martian Heart" by John Barnes

"East of Furious" by Jonathan Carroll

"Late Bloomer" by Suzy McKee Charnas

"The Last Sophia" by C.S.E. Cooney

"Walking Stick Fires" by Alan DeNiro

"The Adakian Eagle" by Bradley Denton

"Rampion" by Alexandra Duncan

"And Weep Like Alexander" by Neil Gaiman

"Pug" by Theodora Goss

"Widows in the World" by Gavin Grant

"Ghostweight" by Yoon Ha Lee

"Choose Your Own Adventure" by Kat Howard

"Younger Women" by Karen Joy Fowler

"The Man Who Bridged the Mist" by Kij Johnson

"The Sighted Watchmaker" by Vylar Kaftan

"Mulberry Boys" by Margo Lanagan

"Canterbury Hollow" by Chris Lawson

"Some of Them Closer" by Marissa Lingen

"The Summer People" by Kelly Link

"The Choice" by Paul McAuley

"A Small Price to Pay for Birdsong" by K.J. Parker

"Woman Leaves Room" by Robert Reed

"My Chivalric Fiasco" by George Saunders

"Fields of Gold" by Rachel Swirsky

"The Smell of Orange Groves" by Lavie Tidhar

"The Girl Who Ruled Fairyland, for a Little While" by Catherynne M. Valente

"The Sandal-Bride" by Genevieve Valentine

"The Cartographer Wasps and the Anarchist Bees" by E. Lily Yu

I'm also going to have at least two new short stories coming out in 2012, as well as at least two reprints. I'll tell you about those once I know when they'll be coming out!

I was thinking about my writing today. When I teach writing, I tell my students to think about the central themes of their papers. I often ask them to make a list of words that capture those central themes. I don't have a list of words for my stories – but I do have a few sentences that seem, to me, to capture what at least some of my stories are about. The stories that are, perhaps, most me – most the stories that come directly out of my understanding of the world. Here are the sentences:

There is a ground under your feet, even thought you feel as though you're walking on air.

There is a meaning to it all, even though you don't know what that meaning is.

Life is dangerous, but it can also be magical.

Now that I read over them again, it seems to me that they are fairy-tale sentences. Fairy tales, after all, teach lessons like those. And maybe that's what I'm really writing: fairy tales, told as though they were stories. Pretending to be stories. I don't know, but it's at least an interesting provisional thought. (Someone, in a review I think, once said that I write fantasy as though it were realism. And I think that's essentially right.)

December 22, 2011

Solstice Night

Last night was the longest night of the year.

Today I've been sitting at my desk and working, working, working. Which is actually not all that good for me. I need to get out into the world, or at least take a break and read. And I haven't been doing much of that. But the work needs to get done.

Today, on the Tor blog, there was a post called Picturing Winter: A Solstice Celebration. Tor asked fantasy artists to send their favorite images of winter, and it's a wonderful collection. I'm going to include a few of my favorites here, but go and look at them all. Here you go, my favorites:

Last night was the longest night of the year, and I have a strange feeling, as though I'm stuck in a sort of trench, a dip in the year, a time when nothing much happens. Or at least when nothing much seems to be happening, but things are happening underneath, secretly, where I can't see them. And I'll see the results of them later, maybe not for months. It's a strange feeling, and like all intuitions, I question it – I wonder if I'm simply making it up. But my intuition has generally led me right before.

I think the only thing to do, when you're in a trench, a dip, a time when nothing seems to be happening, is wait. I think it's the time of darkness, when nothing seems clear, when the way doesn't seem to be there. And you just wait, and look at pictures of winter, and do the work you have to, and trust that somehow, somewhere, things are coming right.

December 21, 2011

Early Poetry

The new issue of Stone Telling has a very interesting article called "The Poetry of Joanna Russ, Part I: An Introduction," by Brit Mandelo. It's on the poetry that Joanna Russ wrote when she was young, just in college actually. It starts like this:

"Joanna Russ (1937-2011) is well-known for her incisive, transformative work in science fiction, feminist theory, and literary criticism—often, all three at once—but her early works, which include a considerable amount of poetry, are rarely discussed. While her first publication in the SF field was a short story, "Nor Custom Stale," in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1959, it was not her first magazine appearance by far: she had already been published several times as a poet, from the age of seventeen onwards, and much of that poetry was what we would now deem speculative in that it dealt with apparitions, fantasies, and myths."

Joanna Russ wrote poetry: who knew? I certainly didn't. But it makes sense. So many of us do start writing poetry, and so many of us give it up. The article speculates as to why she would have given it up, and then makes a case for paying attention to that early work. What it doesn't do, and I wish it did, is reprint any of the poems. For that, I think we need to wait for Part II. Mandelo writes, "In the second installment of this study, I will discuss the actual poems that are the subject of the preceding histories and speculations, the poems that are so generally invisible in the critical conversation about Russ-the-artist." I assume that means she will at least be quoting from them. I'd love to see them – evidently they're not actually available anywhere, and a Google search yields nothing. This is where scholars become important. They preserve and bring to our attention what would have been lost otherwise.

The article made me think of the poetry I wrote when I was younger. I don't have time to write a real blog post tonight, because I'm still finishing some work from the semester. So I thought I would include a few of those poems. They're from 1993-1995, when I was just graduating from law school and starting to work as a lawyer. I knew that I wanted to be a writer – I'd written part of a first novel, The Queen of Myr, during law school, when I should have been studying. (I'm sure it's still somewhere, although I have no idea which of the boxes it's in.) But I didn't know how to get there. I would sit in my office on the 42nd floor of the MetLife building, during my lunch hour, and write poetry. I was pretty desperate, back then. And I'm not sure I could have imagined where I am now – in a place where I can write whatever I want to, where I'm not exactly financially free (because you know, stockings and fans), but where I don't have the crushing burden of debt I did then. Anyway, because I have work to get back to, I'll just give you these poems. The first one has been published (and I may have posted it here before). The others haven't.

Beauty to the Beast

When I dare walk in fields, barefoot and tender,

trace thorns with my finger, swallow amber,

crawl into the badger's chamber, comb

lightning's loose hair in a crashing storm,

walk in a wolf's eye, lie

naked on granite, ignore the curse

on the castle door, drive a tooth into the boar's hide,

ride adders, tangle the horned horse,

when I dare watch the east

with unprotected eyes,

then I dare love you, Beast.

I Knew a Woman

I knew a woman kind as any star.

She wrapped the night wind warm about her neck.

She sang like crickets chirping in a jar.

She called the violet twilight her true home

and dusted constellations. For her sake

the moon swept out its pewter-powdered dome.

Black clouds would scorn to sail on common ponds

and light upon the liquid of her mind.

They flared and ruffed their fluted wings like swans.

And when she spoke the poplars strove to hear,

and when sometimes she cried out in the wind,

her voice was more than all the stars could bear.

The Genius

If you have met him shining among the cobbles,

that genius whose yowl will frighten the moon,

that werewolf-man, if you have witnessed him at noon

whistling, walking tattered with the natty rabbles,

if you have seen him among bankers and bakers, ragged and shining,

and thought him lucky: every night the night devours him.

(I may have posted that last one here before as well, I don't remember.) So that's what you get today, my early poetry. Back to work:

(Almost. I found one more I want to post. And if they bother you as well, you will immediately know what this poem is about.)

The Goblins

I have frequented the ways, even the byways of men,

I have gone forth silently, still-countenanced and cold;

they have not noticed clustered at my hem

the tattered-earned smirking little goblins bold.

I have bowed and seemed to smile and seemed to converse with them,

while my face remained pale and my words retained their chill,

and the little goblins chattered and clattered at my hem

in voices triumphant and shrill.