Theodora Goss's Blog, page 45

December 7, 2011

Writer and Author

Writer. From the Old English writere, Middle English writer. A person who can write; one who practices or performs writing. More specifically, one who writes, compiles, or produces a literary composition; the composer of a book or treatise; a literary man or author. In English, the word goes back to at least the 800s.

Author. From the Latin auctor, Anglo-Norman autour or auteur. The person who originates or gives existence to anything. One who gives rise to or causes an action, event, circumstance, state, or condition of things. An inventor, constructor, or founder. In a more specific sense, one who sets forth written statements; the composer or writer of a treatise or book. (In this specialized sense, the word goes back to the 1300s.) The Creator.

It's a much grander thing to be an author, isn't it?

The definitions above come from the Oxford English Dictionary. For me, the writer is the craftsman, the one who does the work. Who sits down in front of the computer every day and puts words on the screen. (Or in my case, words on paper, since I still write most of my first drafts out longhand.) The author is the one who goes to conventions and gives readings, who is a public presence. The one who is given credit for being the originator, the inventor, the constructor of worlds. There's a reason God is identified as the author of our being.

I suspect the words also reflect the old distinction between the Anglo-Saxon and therefore low, and the Latinate and therefore elevated, like pig and pork, cow and beef. When it's running around the farm, it's pig and cow. When it's served at the Lord's table, it's porc and beouf.

I was talking to a friend of mine about the proper behavior for a writer, when readers comment on a book. And we agreed that the proper behavior was to remain silent. Here's what I mean: most writers track what is being said about a book. They check Amazon reviews, they check Goodreads, they Google. They just do. And when they do, they sometimes come across reviews they disagree with, opinions they might want to contest. What should they do? Remain silent. Here's why.

Once you write the book and it's published, it's no longer yours. It belongs to the reader. The reader creates the book in his or her head, based on what's on the page. He or she enters into a relationship with the book. And in that relationship, you have no place. Yes, you can certainly thank someone for a nice comment. But you must never respond to criticism. It's like interrupting someone else's date.

Because you see, once the book has been published, you as the writer no longer exist. Instead, what exists is the author, and you are not the author. (What? you say. Don't I get to be God? And the answer is, no, you don't.) The author is constructed by the reader based on the book itself. The author exists in the reader's imagination, as the creator of the book he or she has read. The author is not you. Is, in fact, someone a lot cooler than you.

(I know, I'm using these terms in a slightly different way than the OED. But I get to do that, because I'm the writer.)

The writer is the craftsman, and by the time the book is published, the writer has already gone on to the next book. What remains is the author, who is a shadow that the book itself casts.

The writer can conspire to create the author, can create an image of himself or herself. Many writers do. But I suspect that effort only works if the image fits the writing, fits the book. That's what we call branding, nowadays. I'll show you an example from a hundred years ago.

Here is the writer Christina Rossetti (second from left):

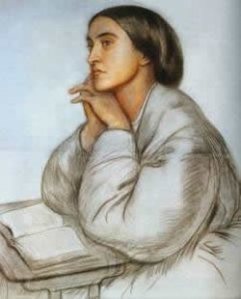

And here is the author Christina Rossetti:

Can you see the different? The portrait (by her brother Dante Gabriel) is the pre-Raphaelite equivalent of a publicity photo.

So, the writer can participate in creating the author, but in the end, the author is created by the reader, based on the book. Because it's the relationship between the reader and the book that matters. The author can, in fact, change the writer – turn him or her into a reflection of the reader's expectations. But in this process, the writer, the real writer who gets up in the morning and has cereal for breakfast, and needs to get a haircut, and forgot to pay rent – that person should remain silent. His or her job is to write the next book.

It's an intensely consoling thought, actually. I'm a writer, which means that I can sit in front of the computer in my pajamas, writing a mess of a first draft. The writer is the one who loves the craft, loves putting words on paper or screen. Every once in a while it's nice to dress up and be the author, but I would rather let her wander around the internet, existing in people's imaginations and on their blogs – when they talk about Theodora Goss. In the meantime, Dora can sit cross-legged in her chair, in pjs and warm socks, writing.

December 6, 2011

Girl Monsters

Do you remember a story of mine called "The Mad Scientist's Daughter"? It was originally published on Strange Horizons, and will be reprinted in The Mad Scientist's Guide to World Domination. I've been thinking, for a long time now, of turning it into – not a play exactly, but what is sometimes called a "read-aloud play." To be read by seven participants (since there are seven characters). I've been thinking that if I can turn it into a play of that sort, I could present it instead of doing a reading at Readercon. The story is already mostly a series of conversations – my characters talking and telling stories to one another.

I think I could get it down to an hour. It would be interesting to see it come to life. If if works, if it's any good, I could publish the script and make it available for anyone to put on. I think there are groups out there who might be interested, who might identify with my girl monsters. I've even thought (because I tend to think this way) of doing some sort of YouTube video. That would probably take a Kickstarter campaign, and already I'm thinking, what am I getting myself into? Because I have more than enough going on in my life right now. But wouldn't it be fun?

And then I need to get back to working on the novel version, and figure out a way to get to London next summer so I can do the research for it. (This is why I don't think I'm going to regret, on my deathbed, having worked too much. Because all of my work is so incredibly cool.)

So, I'm going to give you a sense of what I'm thinking. First, the characters. This is what they should look like, more or less. Of course what they actually look like will depend on the participants, but this is how I imagine them.

Catherine Moreau: Catherine was created from a puma and worked for years as a sideshow freak. She has dark skin, dark hair. She should look vaguely feline. Most importantly, she should have visible scars on her face from the surgery.

Justine Frankenstein: Justine should be tall, as tall as possible. She should look Swiss. I imagine her rather droopy, with pale, lank hair. She can speak ordinary English because although she was created from a Swiss girl, she grew up in England.

Beatrice Rappaccini: Beatrice is Italian. She should speak with an Italian accent, and she should be very, very beautiful. The poisons in her system have made her particularly alluring.

Mary Jekyll: Mary should look like a stereotypical English girl. She is logical, rational. I might give her glasses. Of my girl monsters, she's the one who seems most normal.

Diana Hyde: Diana is wild, uncontrollable. She needs to be played by someone who can curse, laugh raucously. I imagine her looking like a stereotypical gypsy. Whereas Mary is all logic, Diana is all emotion.

Helen Vaughan: Helen is older than the others. She has a daughter. Wait, maybe I should include the daughter in some way? Mother and daughter both look Greek.

Mrs. Poole: All of the others should be dressed as Victorian ladies, although I would recommend aesthetic dress. They are radical, after all. Mrs. Poole is the housekeeper. She should look like a nice, ordinary older woman.

And now I'm going to give you some dialog, scarcely altered from the original. Which may mean that it won't make a very good play, perhaps. But when I read it, I always seem to get a good response. So here you go, just a bit of "The Mad Scientist's Daughter":

Catherine: Sometimes we talk about our fathers.

Justine: My father loved me. He made me from the corpse of a girl who had been a servant of the Frankenstein family. She had been hanged for a crime she did not commit, and he had preserved her body, anticipating that some day he might be able to once again give her life. He even gave me her name, to commemorate her innocence. I can't begin to tell you what a wonderful childhood I had! My father guided me gently through the various stages of knowledge. He taught me the words to describe the world around me: the birds, the plants, the phenomena of nature. He taught me to read, and in the evenings we would read together: Paradise Lost, The Sorrows of Werther, Plutarch's Lives. But he was always haunted by the memory of the creature he had created, and eventually that creature came for him. At his death, I lost my father and my only friend. Until – until I found you." (Justine blows her nose into a handkerchief.)

Beatrice: For so many years I was angry at my father. I thought, he had no right to make me poisonous, to make my only playmates the plants of his garden.

Helen: He had no right. Seriously, Beatrice, you're too forgiving. You need to learn to stand up for yourself.

Mary: For goodness' sake, let her finish. You're always interrupting.

Helen: That's because I can't stand to see any of you justifying them. I mean, seriously. They were abusive bastards, and that's all there is to it.

Catherine: I have to agree with Helen. Abusive bastards seems, you know, fairly accurate. I mean, look at my father.

Beatrice: I don't think you can compare my father to yours, Cat. No offense, but your father was a butcher. Mine brought me up himself, in a beautiful garden –

Mary: I agree that there are relative degrees of – well, although I don't like to say it, abusive bastardhood. But Bea, he never taught you anything. All that time on his hands, and he never took any of it to sit you down, teach you about your own biology. So you ended up poisoning the man you loved, basically by accident –

Beatrice: I should have known.

Diana: Why in the world would you blame yourself? I'm with Helen. They were bastards, the lot of them, even Justine's sainted Papa Frankenstein. Look at me, born in a brothel. My mother died of syphilis.

Mary: You can't generalize your story to all of us.

Diana: Oh, right, now you're taking the other side. My story is our story, or have you forgotten, sister?

Justine: For goodness' sake, why are we arguing? I know perfectly well that my father wasn't perfect. But why should I remember all his faults? Why can't I remember the good times we had together, how kind he could be?

Helen: Because that's like lying to yourself. We've all been lied to. Do we really want to lie to ourselves as well? My father was a scientist, like yours. He took my mother from the gutters, where she was starving, fed her, educated her, seduced her, and then experimented on her. She had a vision. She saw something she could not, or perhaps did not have the guts to, understand – the god Pan, source of all order and disorder, Alpha and Omega, to whom all things in the end will come. Nine months later I was born, daughter of the respectable Dr. Raymond and of Pan. It's not hard to understand why, as a teenager, I tried to destroy the world. Sometimes I wish I had. I mean, look at it. The other day, a man tried to steal my pocketbook. He was drunk, red-eyed and reeking of gin, and I turned and started hitting him with my umbrella. I thought, I could have destroyed you all – the beggars, the bankers, the filthy streets of London.

Catherine: So, why didn't you?

Helen: Well, I married Arthur around that time, and then Leda was born. I would have had to destroy Regent's Park, and ice cream, and prams. It just didn't seem practical. Besides, I didn't want to give my father the satisfaction.

Mrs. Poole (enters): Would any of you ladies like some tea?

December 5, 2011

Having No Regrets

First, I'm sorry that I haven't commented on posts for the last few days. This is the last week of the semester, and I'm so tired! I promise that I'll catch up. (It's the sort of deep tiredness you have when all you've been doing is working. No museums, no going to antiques stores. Barely reading, although I left Shadow hanging on the tree, and I don't know whether he'll live or die. Quantum Gaiman.)

Second, I have one final item listed in the auction for Terri Windling:

Offered: Signed Copy Of The Thorn And The Blossom, With Bonus Manuscript, By Theodora Goss

Offered: A signed copy of The Thorn and the Blossom, by Theodora Goss, with cover art and illustrations by Scott McKowen. This book is coming out early next year, so you will be among the first people to have a copy. It's a wonderful book to give as a gift, to someone else or yourself! And because one of the main characters, Evelyn, is a poet, Theodora will also include a signed manuscript of a poem she might have written.

One enchanting romance. Two lovers keeping secrets. And a uniquely crafted book that binds their stories forever.

When Evelyn Morgan walked into the village bookstore, she didn't know she would meet the love of her life. When Brendan Thorne handed her a medieval romance, he didn't know it would change the course of his future. It was almost as if they were the cursed lovers in the old book itself . . .

The Thorn and the Blossom is a remarkable literary artifact: You can open the book in either direction to decide whether you'll first read Brendan's, or Evelyn's account of the mysterious love affair. Choose a side, read it like a regular novel,and when you get to the end, you'll find yourself at a whole new beginning.

Here is the cover of the book (actually the slipcase):

And here is a video showing how it works:

Opening bid: $15

Auction ends at 5 p.m. Pacific Time, December 15th 2011

The publisher has just told me that there will also be bookmarks, so I will of course include some of those as well.

Today I'm too tired to write about literature or art. So instead I'm going to write about life. I came across a blog post called "Regrets of the Dying" by Bronnie Ware. Here is what she says:

"For many years I worked in palliative care. My patients were those who had gone home to die. Some incredibly special times were shared. I was with them for the last three to twelve weeks of their lives.

"People grow a lot when they are faced with their own mortality. I learnt never to underestimate someone's capacity for growth. Some changes were phenomenal. Each experienced a variety of emotions, as expected, denial, fear, anger, remorse, more denial and eventually acceptance. Every single patient found their peace before they departed though, every one of them.

"When questioned about any regrets they had or anything they would do differently, common themes surfaced again and again."

She lists the five most common, which I'm going to list here, without the accompanying explanations. You can read those in her post. Instead, I want to think about my life, and whether I'm going to have those particular regrets as I'm dying. (I know, this is a bit grim. But it's a way of checking myself. You can check yourself as well.)

1. I wish I'd had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.

I think I'm doing pretty well at this. The life others expected of me was the life of a corporate lawyer in Manhattan. That's what I was trained for. (After all, I went to law school with the President. And here I am teaching writing to undergraduates.) But it wasn't my life, so I left it. I went back to school for the training I wanted, to be both a teacher and a writer. I could have taken an easier route and worked toward an MFA, but I felt that a PhD in literature would be the best training for the sort of writing I want to do. And for my particular temperament. Although the PhD has, at times, caused my much anguish and some boredom, I think I was right. I think this was the degree I was supposed to get.

I think I am living a life true to myself. The next step in living that life is focusing on the writing.

2. I wish I didn't work so hard.

I'm not sure what to say about this one, because the work I do is work I love . There's the work I have to do, of course, because I have to keep myself in stockings and fans (that's a Cold Comfort Farm reference, in case you were wondering). But the honest truth is that I love teaching. And in addition to the teaching, there's writing, and doing publicity for my writing, and all the other projects connected to the writing that I seem to have so little time for.

I do think I need to keep in mind that I need more time to rest, more time to simply experience the world. Go to museums. So that's something to remember.

3. I wish I'd had the courage to express my feelings.

Yeah, I'm terrible at this one. I was raised in a European family with distinctly old-fashioned expectations, in which one did not express inappropriate feelings. Let's just say I'm working on being more honest about what I want and need out of life.

4. I wish I had stayed in touch with my friends.

This one, I need to work on. There's so little time. But I need to make time to talk to friends. Or the only one coming to my funeral will be my therapist.

5. I wish that I had let myself be happier.

I don't think it's a matter of let, with me. I tend to take hold of any chance at happiness I get. I never refuse chocolate, or free tickets to anything. Preventing yourself from being happy is the stupidest thing you can possible do. Why would you do that to yourself?

I've been to the depths, to the shadowlands. Happiness is a glorious gift. I'll take it whenever and wherever I can find it.

How did I come out? Pretty well, I think. And I know what I need to do: connect more, express more. Those have always been my problems, and I'm going to work on them. Assuming I survive this week.

December 3, 2011

Telling the Truth

My Klout score is 58. This morning, I weighed 126 pounds. The advance for my first book was $0. The advance for my last book was $5,000.

Why am I telling you this?

About a week ago, I read a story in The New York Times about Klout.com, which claims to track and score your social influence. I had no idea what it was, so of course I checked it out. And now I know my Klout score. What I learned in the process is that, although everyone I asked about it told me how silly it was, how it made the internet seem like high school, many of the people I know and follow were on Klout. They were presumably checking their Klout scores as well. (I won't name names. You know who you are.) The higher their score, the more likely they were to be registered on the site.

And this got me thinking about all the things we don't talk about.

There are so many of them!

I think it's because we don't want to seem shallow, vain, narcissistic. We don't want to seem overly concerned with money. (When you're in a group of writers who are just starting out, they talk about craft. When you're in a group of professional writers, and all of you in that group are professional writers, you know what they talk about? Money. And sales. That's where you get the real information.) We know that we're supposed to focus not on our weight, but on our health. We know we're not supposed to compare ourselves to others (although we don't, don't we?). We're supposed to be inclusive rather than competitive. But the truth is that many of us are competitive and ambitious. We just politely disguise the fact that we are. And of course there are the things we're ashamed to talk about, because they might expose that we've failed.

The problem with not telling the truth is that we end up not telling each other things – withholding information. I spent years reading ridiculous and potentially harmful diet books before I realized that the people who actually maintained the shape I wanted to be in all monitored their weight carefully. So now I count calories, and I weigh myself every morning. If I weigh more than I would like to, I cut back on my calories. When I say that I need to lose five pounds, I always get "Oh no, you look fine," as though my statement were some sort of code for self-doubt or criticism. But what I actually mean is that in the next month, I intend to lose five pounds. I take ballet classes. If I don't understand and have control over my body, I could injure myself.

Similarly, we are often given the impression that people with writing careers got them in some mysterious way – by luck, by good fortune. That may sometimes happen, but it's rare. The people I know who have writing careers built them – they are ambitious, they kept track of their progress. They publicized in specific and targeted ways.

I'm always fascinated by stories of how people got where they are, like this article on how Imogen Heap makes and markets her music. How she has found her own way in the music industry, which is even harder to navigate than the publishing industry. And when I read stories like that, I think, is there a lesson in it for me? For what I do? Because I am ambitious, and silly as a Klout score genuinely is (what does it mean, anyway?), I'm going to keep track of it. And if it falls, I'm going to wonder why.

I'm always grateful to people who tell the truth, rather than practicing polite reticence or obfuscation. People like Catherynne Valente or Tobias Buckell (who once gathered and posted information on book advances – the first information some people had ever seen on what is standard in the industry). And I think that if you're a writer, telling the truth is important. That's the business we're in, after all: truth-telling, even if we tell it with elves or dragons. If you're a writer, you have no business maintaining polite fictions.

I think society expects us to make it look easy. Like ballet: a good ballerina will make it look as though anyone can jump that high. But it takes a lot of work. If I didn't watch calories, I would gain weight fairly quickly, because I like food. A lot. I want my next advance to be higher (if any publishers are listening). And I'm going to keep working on this writing career of mine, because it really, really matters to me.

Also, and this is the final thing I'll say, in our society there's a tremendous sense of shame associated with failure. I'm always so grateful when people talk about their failures (Imogen Heap was dropped from record labels twice), because it makes me feel as though my failures are not so bad, nothing to be ashamed of. Simply bumps on the road. So in the interest of truth-telling, I did not get into graduate school the first time I applied (my essay was not particularly good, and I wasn't mentally ready – it was a failure, but turned out to be good for me because I ended up in the program where I belonged). My hair color is Naturtint 7G Golden Blonde, and yes it's close to my natural hair color, but redder, brighter, because I like it that way. And I deal, on and off, with depression, which is not a mood but a recurring illness. I've been dealing with it a lot this year.

If I can think of anything else to tell the truth about, I'll let you know.

December 2, 2011

The Real Miéville

This happens to you a lot as a writer: you watch a television show, and you can see the clever, intricate way it's going to end, and then it doesn't. The show ends with one fewer plot twist than you had foreseen, and you're disappointed that the writers weren't clever enough to see the final twist that would have made it so much better.

Recently, I read an article by China Miéville called "M.R. James and the Quantum Vampire." When I started the article, I thought, what a clever parody of academic prose! Because of course Miéville is a Ph.D., which means he must have encountered a lot of that prose, but he's also a writer, so he knows what's wrong with it, ridiculous about it. We all do. And I had a great deal of respect for him, because I thought it was a brilliant, and incredibly funny, parody.

As I continued reading, I started wondering – was it a parody, or was he actually just writing like that? Because if he was actually writing like that, in all seriousness, then – I didn't know what to make of it.

Here are the first two paragraphs:

"0. Prologue: the Tentacular Novum

"Taking for granted, as we do, its ubiquitous cultural debris, it is easy to forget just how radical the Weird was at the time of its convulsive birth.(1) Its break with previous fantastics is vividly clear in its teratology, which renounces all folkloric or traditional antecedents. The monsters of high Weird are indescribable and formless as well as being and/or although they are and/or in so far as they are described with an excess of specificity, an accursed share of impossible somatic precision; and their constituent body parts are disproportionately insectile/cephalopodic, without mythic resonance. The spread of the tentacle – a limb-type with no Gothic or traditional precedents (in 'Western' aesthetics) – from a situation of near total absence in Euro-American teratoculture up to the nineteenth century, to one of being the default monstrous appendage of today, signals the epochal shift to a Weird culture.(2)

"The 'Lovecraft Event', as Ben Noys invaluably understands it,(3) is unquestionably the centre of gravity of this revolutionary moment; its defining text, Lovecraft's 'The Call of Cthulhu', published in 1928 in Weird Tales. However, Lovecraft's is certainly not the only haute Weird. A good case can be made, for example, that William Hope Hodgson, though considerably less influential than Lovecraft, is as, or even more, remarkable a Weird visionary; and that 1928 can be considered the Weird tentacle's coming of age, Cthulhu ('monster [ . . . ] with an octopus-like head') a twenty-first birthday iteration of the giant 'devil-fish' – octopus – first born to our sight squatting malevolently on a wreck in Hodgson's The Boats of the 'Glen Carrig', in 1907.(4)"

What's so funny about this? First, numbering the prologue 0, then calling it "The Tentacular Novum." Classic examples of academic pretentiousness, the 0 and the introduction without definition of the term "novum" (from Darko Suvin), but punctured by calling the novum "tentacular." Then, the inclusion of terms that seem to define a category, but are also somewhat ridiculous: "high Weird," becoming the even fancier French "haute Weird" in the second paragraph. The use of scientific terms applied to the literary: "teratology," "teratoculture." (Teratology is the study of developmental defects.) The glancing reference, without explanation, to Georges Bataille's The Accursed Share. The paragraphs are dense with academicspeak, and the funniest thing of all is what they describe: the birth of a new genre that has gotten absolutely 0 academic respect because it's about gods with octopus heads. He's writing about the grotesque in a way that is itself grotesque, by which I mean that his writing is continually reaching out like tentacles to incorporate the most ridiculous instances of academicese. Tentacular novum indeed!

I'm going to include a few examples of what I consider particularly funny passages because of the way in which they parody academicspeak.

"In short order, the two key figures in the French pre-Weird tentacular, Jules Verne and Victor Hugo, produced works – Verne in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1869) and Hugo in The Toilers of the Sea (1866) – which include extraordinary descriptions of monster cephalopods. These texts, while indispensable to the development of the Weird, remain in important respects pre–Weird not only temporally but thematically, representing contrasting oppositions to the still-unborn tradition, to varying degrees prefigurations of the Weird and attempts pre-emptively to de-Weird it."

Pre-emptively to de-Weird it! All right, he's putting us on. I know he is. This is The Pooh Perplex with tentacles.

"Weird writers were explicit about their anti-Gothic sensibility: Blackwood's camper in 'The Willows' experiences 'no ordinary ghostly fear'; Lovecraft stresses that the 'true weird tale' is characterised by 'unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces' rather than by 'bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains according to rule'.(24) The Weird entities have waited in their catacombs, sunken cities and outer circles of space since aeons before humanity. If they remain it is from a pre-ancestral time. In its very unprecedentedness, paradoxically, Cthulhu is less a ghost than the arche-fossil-as-predator. The Weird is if anything ab-, not un-, canny."

All righty. It's ab-canny (refering to Julia Kristeva's notion of the abhuman) rather than un-canny (referring to Freud's notion of the uncanny). Clever clever.

And of course he refers to Freud, Lacan, Kristeva. How could he not? The article contains (or attempts to contain – there you go, now I'm being all academicy myself) an excess of references. It's easiest to read with Wikipedia on standby, although if you haven't read Freud, Lacan, Kristeva, you're not going to get the references anyway.

But then I start to doubt, because it goes on for so long, and it's all like this. So maybe it's not a parody after all? Maybe Miéville is taking himself completely seriously? As he goes on, the academicese drops away to a certain extent and the article sounds more like an actual standard academic article, rather than a parody of one.

(I just have to point out that when he mentions "the protoplasmic formlessness of the dying vampire Carmilla (1872)," he must be thinking of Helen Vaughan from The Great God Pan, because we do not actually see how Carmilla dies – her protoplasmic formlessness comes earlier in the text.)

Although you still have paragraphs like this:

"There is, in 'Count Magnus', and in James in general, no aufhebung of the Weird and hauntological. The two are, I suggest, in non-dialectical opposition, contrary iterations of a single problematic – hence in 'Count Magnus' the peculiarly literal and arithmetic addition of Weird to hauntological (with the latter privileged, precisely because James is, fundamentally, somewhat ghostlier than he is Weird)."

Aufhebung: a term used by Hegel to explain what happens when a thesis and antithesis interact, meaning something like "abolish," "preserve," or "transcend." (Hunh? Wikipedia, you are not being helpful. Maybe I need to just go ahead and read Hegel.)

And it's shortly followed by this: "If the contradiction between Weird and hauntological was sublatable, then such drives would surely have led to the monstrous embodiment of any putative 'resolved' third term between Weird and haunt." Which I understand, but which is tiring to read. But then Miéville tells us what such a resolved third term would look like, a human skull surrounded by tentacles, and suddenly the article is funny again. There you go, there's your aufhebung! It looks like a biker tattoo.

I don't need to go on, right? You get the point. I don't know whether to read the article as parody or not, but I'd like to read it as parody, because Miéville is wonderful at writing in different genres (as in The City and the City, which was clever beyond clever), and he must be aware that he's doing all the things that academics complain about in academic papers. And doing them to excess.

And Miéville seems aware of that. After all, the article is subtitled "Weird; Hauntological: Versus and/or and and/or or?" (seriously? I think not), and he ends the article with his own illustration of the aufhebung: a skulltopus! Also, his blog is a perfect parody of what a blog should be, or what we are all told a blog should be. It's an anti-blog.

In March, I'm going to be at the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts, where Miéville will be one of the guests of honor. I look forward to hearing what he has to say, and to getting him to sign some books. But I wonder: who is the real China Miéville? Is he the guy who takes himself seriously enough to write an article like that, without seeing the parodic elements? Or is he the guy who wrote the parody I think I'm reading? I hope he's the latter. I hope I'm seeing the right plot twist.

December 1, 2011

Auction for Terri

I was so tired last night, after teaching all day and then a committee meeting, that I couldn't even write a blog post. So I'm making up for it by writing an extra one today, to tell you some more about the auction I described in my previous post. You can learn about the auction by going to its website:

And here is some information on why the auction is taking place:

"Beloved editor, artist and writer Terri Windling is in need, and we are asking for your help in a fundraising auction to assist her. This auction will combine donations from professionals and fans in an online sale to help Terri through a serious financial crisis.

"Terri is the creator of groundbreaking fantasy and mythic art and literature over the past several decades, ranging from the influential urban fantasy series Bordertown to the online Journal of Mythic Arts. With co-editor Ellen Datlow, she changed the face of contemporary short fiction with The Year's Best Fantasy and Horror and other award-winning anthologies, including Silver Birch, Blood Moon and The Green Man: Tales from the Mythic Forest. Her remarkable Endicott Studio blog continues to bring music, poetry, art and inspiration to people all over the world."

There are many people I need to thank for my writing career, but Terri is at the top of the list. She bought stories and poetry of mine when I was just starting out, and she wrote the introduction to my short story collection In the Forest of Forgetting, which was an enormous privilege for me. And I was deeply influenced by her novel The Wood Wife, which showed me new ways of thinking about fantasy. She's one of my favorite people ever, but I think a lot of people say that about Terri.

I'll tell you about two items I've donated to the auction. Click on the links to get to the items offered.

A Critique by Award Winning Writer/Writing Teacher Theodora Goss

Offered: A critique of your short story or first chapter of your novel (up to 10,000 wds.) by Theodora Goss.

Theodora says: I'm offering to critique up to 10,000 words of a short story or novel. The critique will include a mark-up of your manuscript, a typed critique, and a conversation with me (in person if you live near Boston, by Skype if you live farther away). I am a World Fantasy Award-winning writer, the author of In the Forest of Forgetting, Voices from Fairyland, and the forthcoming The Thorn and the Blossom. I am also the co-editor (with Delia Sherman) of Interfictions. I teach writing at Boston University and have taught novel and short story workshops at Readercon and Boskone. I have also taught at the Odyssey and Alpha writing workshops.

Opening bid: $30

The second is signed copies of my two short story collections, one of which is no longer available, plus a signed manuscript of a story of your choice.

Offered: Anthology and Chapbook by Theodora Goss , Covers by Virginia Lee/Charles Vess

Offered: In the Forest of Forgetting and The Rose in Twelve Petals and Other Stories, plus a bonus story manuscript, all signed by the author.

In the Forest of Forgetting is a hardback with a cover illustration by Virginia Lee.

The Rose in Twelve Petals and Other Stories is a chapbook with a cover illustration by Charles Vess. Only 500 copies were printed, and they sold out in a matter of months. No more will ever be produced.

In addition, you can choose one story from either book and the author will send you a signed manuscript of the story.

Goss's stories and poems are a haunting mix of cobwebby fairy tale elegance and tough-as-concrete contemporary sensibility. – Charlene Brusso, sfsite.com

Opening bid: $50

There are so many amazing items offered in the auction that I'm just going to list some of the ones I covet.

Offered: Be A Character In An Upcoming Animated Film "Xibalba"

Offered: David Wyatt Print, "In the Word Wood With Terri and Tilly"

Offered: Limited Edition Print by Virginia Lee – "Miss Birch"

Offered: Original James A. Owen Illustration

Offered: Die a Gruesome Death! This one is really special:

Offered: Shirley Jackson Award winner Lucius Shepard will Tuckerize you and kill you dead! The author will use your name and general description for a character in an upcoming story and kill you gruesomely. He says that he is currently working on two different sci-fi/horror stories so this is a grand opportunity to be brutally and creepily dispatched by one of the best writers in the field!

Offered: Tuckerization in a Jeffrey Ford Story

Offered: Rare Limited Edition Print, "Gereint" by Alan Lee, #193 of 200

Offer: Handwritten Poetry Manuscript, Patricia McKillip

Offered: Manuscript critique by Author and Writing Teacher Christopher Barzak

Offered: Advance Reader's Copy, Radiant Days by Elizabeth Hand

Offered: Exclusive mp3 of New, Unrecorded S.J. Tucker Song with Handwritten Lyric Sheet

Offered: A Jane Yolen Poem Starring Yourself!

Offered: Lunch or Dinner with Tamora Pierce

Offered: Personalized Copy, Arthur Spiderwick's Field Guide

Offered: Character Naming Rights, Catherynne M. Valente Fairyland Novel

Those are just a few of the items being offered. Go to the website to see all of them!

And I have to tell you one more thing, which hasn't been announced yet. I asked Quirk Books if I could donate a signed copy of The Thorn and the Blossom. I just heard that I can. Why is this a big deal? Because whoever won it would get it several weeks before the date it will be offered in stores – he or she would be one of the first people in the world to read the book. I'll let you know once that item is up!

November 29, 2011

Simplicity

First, let me tell you about the auction to benefit Terri Winding. Terri has been one of the benefactresses of the fantasy community for many years. She is a writer, artist, and editor, and writes one of my favorite blogs, The Drawing Board. She is also one of the loveliest people you are ever like to meet. Because she's been dealing with medical and legal issues, her friends have set up an auction to help her out. The most astonishing things are being auctioned: art by some of the best fantasy artists, plenty of signed books, opportunities to have your manuscripts critiqued, and some truly strange and interesting items. If you'd like to see what the auction has to offer, click here:

I've donated some items to the auction as well, and when they are listed, I'll let you know!

Today's blog post is inspired by a post written by Damien G. Walter, the Guardian columnist who does such a wonderful job bringing attention to important fantasy works and writers.

Yesterday, he wrote a post called "Why Crap Books Sell Millions." It's a response to an interview with Umberto Eco in The Guardian in which Eco says, "I was always defined as too erudite and philosophical, too difficult. Then I wrote a novel that is not erudite at all, that is written in plain language, The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, and among my novels it is the one that has sold the least. So probably I am writing for masochists. It's only publishers and some journalists who believe that people want simple things. People are tired of simple things. They want to be challenged."

Walter has a different opinion. He writes,

"I wish I could agree with Umberto Eco (who I LOVE) in The Guardian when he says that 'people are tired of simple things, they want to be challenged.' And by wish, I mean that every fibre of my superior, snobby little soul is vibrating in agreement. But the rational part of my mind that retains a tenuous engagement with reality knows that more people will watch X-Factor this Saturday than will ever read any one of Mr. Eco's sublime novels.

"When it comes to complexity in novels, it is lost on most people. Worse than lost, it will likely make a text incomprehensible to most people. Because most people, whilst literate, just aren't very good at reading. Dense, poetic prose, rich in symbolism and thematic depth, the things us writerly smarty pants all love so much, will just confuse the hell out of most people. That prose passage you're so proud of, the one that switches seamlessly between the internal monologues of the novel's five key protagonists whilst expanding the narratives core philosophical argument? Most people just couldn't make it go in to their head even if they tried. You may as well expect them to read pure binary machine code.

"Bestselling books are, by and large, simple books. Simple stories, simple language, simple ideas. But, simple is as simple does. Perhaps the real art of the novelist is saying the most complex things in the simplest ways, so that even stupid people can understand."

I disagree with Walter's use of the word "stupid" here because I think it's imprecise. I know people who put one of Eco's novels down after a couple of pages. They're not stupid. The ones I know personally tend to be doctors and lawyers, and they're more likely to watch (and love) Downton Abbey than X-Factor. They like to read John Grisham. They pay attention to the latest bestsellers. They've read The Da Vinci Code and Eat, Pray, Love. They like nonfiction, such as Atul Gawande's books on the medical practice or books by political figures.

Bestselling books are generally simpler, I think that's true. Two summers ago, I was staying at Lake Balaton in Hungary. The house had very few English books in it. I ended up reading a John Grisham. After a while I began skipping, because I realized that if I read random pages, I could still follow the plot. And I recently read Paulo Coelho's The Alchemist.

I mostly liked it, although it lost me toward the end, when Santiago turned into the wind. At that point it became too religious and mystical for me. I lost the connection the book had made, all along, between my personal journey and Santiago's allegorical journey. And for some reason, I didn't like that Santiago's journey was to find his treasure, while the journey of the woman he loved was to find him – her love. She should have been on a quest to find her own treasure. I don't think your treasure can be another person. (Imagine the pressure you put on someone, expecting them to be your life's goal!) But I could absolutely see why the book had sold as well as it had.

It's a simple book, in that its meaning is immediately accessible, and I think Walter is absolutely right that simple books, without the sorts of erudite complexities that one sees in Eco, appeal to a much wider audience. So often when we sit down to read, we want simplicity: a clear path into the book, an easy escape from the reality we're leaving behind. If the book contains a lesson, we want it to be evident, not hidden from us.

That's not necessarily a bad thing. Simplicity can be done badly, or done well. The Little Prince is a lovely book, and it's simple, accessible. The novelist has to make choices, and one of those choices is prose style: between "dense, poetic prose, rich in symbolism and thematic depth" and something else. I suspect the reason Eco's supposedly simpler book did not sell well is that it wasn't written in his style. When people buy Eco, they want Eco. They are prepared to be challenged. If they weren't, they would buy something else.

So I suppose what I'm doing here is, first, saying that "simple" and "crap" are not the same things – that simplicity is an important tool for the writer, that there is a reason simplicity sells, and that it can be used well. And second, I'm saying that what Eco claims may be true for Eco. Readers may go to him when they are tired of simplicity. What is true for one writer may not be true for another – after all, Eco's best-selling book is The Name of the Rose, and how many readers put it down when they get to the chapter in Latin and just watch the movie? Simplicity and complexity are tools for the writer. You need to know which tool you're using and why, and also know yourself – which tool is appropriate for the writer you are.

(I write this as someone who has been advised in the past, by a kindly relative who no doubt wanted to see me on a bestseller list, to read Dan Brown and write more like that. Just so you know.)

November 28, 2011

Reading and Writing

Did you know that Goodreads is running a giveaway for 30 free copies of The Thorn and the Blossom? The contest ends in a couple of days, on November 30th. If you'd like to enter, click on the link below:

The contest is only for readers in the United States. I'm sorry about that, but I assume the shipping costs are too high for foreign readers. (I'm not the one running the contest, of course. I actually only found out about it by looking at Goodreads.)

Today I thought I would talk about the importance of reading, when you're a writer.

One of the nicest aspects of being a writer is that all sorts of things that are entertainment for other people are work, for you. Watching a movie is work. Watching television is work. And of course reading is work. It's work because when you're a writer, you can't help analyzing whatever it is you're watching or reading. You can't help paying attention to setting, characterization, style. Your brain is always taking those things in, and when you go to write, they come back to you. They help you think about story.

Right now, I'm reading American Gods, by Neil Gaiman – the author's preferred version, which I was given for free at the World Fantasy Convention. (I came back with all sorts of books from the World Fantasy Convention.)

I'm fascinated by several things about the book. First, by how well Gaiman has created an American mythology, has captured a sort of American-ness, considering that he grew up in England. It makes me think that I may be able to capture something English in my book, despite having grown up here. It helps that the England I want to write about isn't the real England, but literary England – the one created for us by Charles Dickens and Arthur Conan Doyle. Second, by how easy the book is to read, how you sink into it even though parts of it are unpleasant. The places it describes aren't places I want to spend time in, and yet I'm enjoying spending time in the book itself. Third, by how he breaks rules that I know aren't really rules, but that I had nevertheless internalized. For example, his story is digressive – it goes off into other stories. And that's all right, because I always want to come back to the main story. And the digressions are interesting in themselves. That gives me a sense for how I could write my own novel.

Some writers say that since starting to write professionally, they no longer enjoy reading fiction. That hasn't happened to me (and how awful if it did happen!). What has happened instead is that I read differently. It's as though I read with two parts of my brain at the same time: one part is living in the story, and one part is analyzing it. That doesn't lessen my enjoyment of it – but it changes that enjoyment. I'm like a dancer watching a dance, knowing the names of the steps. I'm glad to be in that position, of an insider as it were.

Being an artist means you get to – have to – live fully and consciously. You can't be lazy in your approach to life. Everything around you is to be experienced, so you can keep the experience until later, when you write the story. That requirement changes the way you approach life. It means that rather than simply experiencing, you are always also observing the experience, mentally recording it. But I think it leads to a richer and more interesting way to live. It gives life a particular intensity.

So if you're an artist, say to yourself, I have permission to experience everything, because it's material. And in particular, make time to watch movies or television, to read. Because those are stories, and you need to experience how other people create stories so you can create stories yourself – so you can think about the art of story-making. But reading is especially important, because you want to know what other writers are doing with words. That gives you a sense for what you can do – for your own possibilities.

And if people accuse you of wasting time because you're watching a police procedural on television, tell them it's because you're working. (Sometimes I watch those terrible true crime shows, because I want to write murder mysteries. It's very useful, learning about different ways to murder someone. We can be somewhat macabre, we writers.)

(When I tweeted a thought about this yesterday, someone responded that using social media also counted as work, for a writer. And I agree with that. But that's for another post. In the meantime, if you want to follow me on twitter? Click here.)

November 27, 2011

Being a Heroine

(If you're male and reading this, substitute hero for heroine and vice versa. I'm writing about being a heroine because I'm female, and I'm thinking about this blog post in terms of myself. But really, what I'm going to write about is not particularly gender-specific.)

I don't know where the phrase "Be the heroine of your own story" originated. It's been knocking about the internet for a while, and Nora Ephron has said it, but I don't know if she was the first.

I think it's an important phrase because we understand the world by telling stories about it, and if we want to change our lives, we need to change our stories. And we can – we can change the stories we tell about our lives and ourselves. And those stories can have significant impact, because what you believe about yourself affects your life in many ways. It affects what you focus on, what you strive for. How you allocate your time.

So I want to try to understand it better. What does it actually mean to be the heroine of your own story?

The heroine has a journey.

In a story, the heroine is on a journey from somewhere to somewhere else. It can be an external or internal journey – of course, it is often both. But she is in progress, on the move. There may be periods of stasis, times she needs to spend up a tree or in the underworld. But those periods are part of the journey, not permanent stopping-places. And they are often times when internal progress happens, when she becomes something different than she was internally, and can then change her external circumstances.

And the heroine defines her journey. It is defined by the choices she makes along the way. She decides whether to climb the glass hill in iron shoes. (Yes, there are stories in which the heroine is passive, but we have been tricked into thinking that is the typical storyline by Disney. In the old fairy tales, the true stories, the heroine is almost always active. She decides whether to be nice to the witch in the woods, whether to weave her brothers shirts of thorns. Whether to marry the white bear.

The heroine has adventures.

This is different from having a journey. On that journey, things happen to the heroine that she cannot control. Those are the adventures. She has to respond to them by making choices, but sometimes there are no good choices. Sometimes it's the glass hill in iron shoes. What that means, in practical terms, is that sometimes the heroine's life sucks. Sometimes she has to serve the witch in the woods for seven years. Sometimes she's stuck in the underworld, which is a boring place, let me tell you.

But if she understands that she's the heroine in a story, she knows that the times that suck are her adventures, and she needs to make it through them with a combination of courage, determination, common sense, and whatever magical implements she can find.

Being the heroine of your own story means that when the bad times come, and they will come if you're the heroine (only non-heroines get to live happy, uneventful lives), you get to tell yourself that they're part of the story. And you get to show that courage, determination, common sense, etc. Which is a lot better, I think, than sitting around and saying, wow, life sucks.

The heroine has flaws.

The heroine always has character flaws. She is curious, opinionated. She does not follow the rules. If the hero says, you may never see my face at night, what is she going to do? Find a candle, of course. Those character flaws get her into trouble. But you know what? They are also the reason we love her. If she were genuinely perfect, we wouldn't care about her, because perfect people are not interesting.

That means you get to have character flaws, and your character flaws are loveable. Even, perhaps especially, when they get you into trouble. (Remind yourself of that, when you get into trouble.)

The heroine is at the center of her story.

You get to be at the center of your story. No one else does. There are going to be people who call you selfish because you want to be at the center of your story. Because you want it to be about you, about your choices. That's because they want to be at the center of your story. Parents do this more often than I think they realize – want to be at the center of their childrens' stories. But your story is about you.

The heroine is not dependent on the hero.

The hero is there, for the heroine to fall in love with, form a partnership with. But he is not at the center of her story. He has his own story, his own journey to go on. While she is climbing the iron hill, he is resisting the advances of the ogress. She can't simply wait around for him to show up – he is not her story. He may be a part of it, their stories may intersect. But she has to go on a journey as well. Otherwise, it's not much of a story, is it? (They met, they married, they lived happily ever after. What's the point?)

The heroine gets interesting clothes.

She may wear a cloak made from the fur of a hundred animals. She may wear a dress as bright as the stars. She may wear a suit of armor. But she gets the interesting clothes. She gets to look like a heroine. Unless she's in disguise. (Are you in disguise? When I worked at the law firm, I was in disguise. Sometimes you have to disguise yourself, among people who don't understand how these things work.)

(I mentioned that this was not particularly gender-specific, so I'll just say here that the hero gets some smashing outfits as well, like magical suits of armor. Plus, he often gets to turn into an animal.)

These are all good things to remind yourself of, if you're the heroine. You're on a journey, and parts of it are going to suck because that's just the way journeys are. But you're going to overcome them – you're going to grow as a person, and lop off the ogress' head. And all your faults and flaws and inadequacies are signs of character – don't let anyone convince you otherwise. You're going to make mistakes because of them, but that's part of the journey too. And don't let anyone tell you that the story is not about you, because it is. Finally, and this is an important finally, you get to look the part, whatever you think looking the part is. Are you the sort of heroine with a gamine haircut who knows how to use a sword? Are you the sort of heroine with hair to your waist who charms animals? There are all sorts of heroines, and you get to decide which sort you are. Because (did I say this already?) it's your story.

November 26, 2011

Style as Story

The title of today's post comes from a line in a blog post by Justine Musk called "How to Be a Genius (Or Just Look Like One)":

"Style is the story you tell about yourself to the world."

In it, she talks about the style of Coco Chanel, and I've written about Chanel before myself. She had extraordinary style. If you are a woman, look into your closet: you will find any number of items influenced by Chanel. As I type this, I am wearing a black knit cardigan over a black knit shirt. Chanel. (Also jeans and Keds, which I'm sure she would never have worn, but she did give us women who dressed like boys – and that's how I'm dressed today, by late nineteenth-century standards. Like a boy ready for sports. A late nineteenth-century woman would never have worn what I'm wearing. It was Chanel who gave us sportswear for women.)

Why did that line catch my attention so much? I suppose because I like to watch people, and so often I find that how they present themselves tells a story – the story of what they think of themselves. Where they see themselves in the world. People tend to place themselves, and style tells you about that place – where it is, what it's like.

I think of style as having three components. First, there is how you look. Then, there is how your surroundings look. And finally, there is something more complicated – the style of your art.

I was thinking of the second today because I recently met a person who told me that he had installed a flat-screen television in his bedroom so he could watch sports. And in the same conversation he told me that his family used paper napkins at dinner. And I realized that was the opposite of how I had grown up – we had no television, because my mother was convinced that it would ruin us intellectually, but we ate with the family silver. And always had cloth napkins. Those are both choices, and the universe won't end if you choose not to have a television (although if I didn't have one now, I'd miss watching Once Upon a Time, or Being Human on DVDs – the BBC version, of course) or use paper napkins. But your choices do reveal your priorities.

I bought two things recently that I thought were very much in my style. The first is an old bowl, probably late nineteenth or early twentieth century, with red transferware and hand- painted details.

I think it's rather pretty. The second is a set of silver plate with a flower pattern on the handle.

These are both things I saw and fell in love with, in one of the antiques stores in Concord. I think style is like that: it's organic, made up of the things you love, the things that are important to you. But it's also something you can think about and develop. Because style is a story we tell about ourselves to the world, and that story is always changing. In a way, if you change your style, you can change your story. So if you want to change that story, if you want the world to perceive you differently, or you simply want to feel differently about yourself, you can do it by changing the way you look, the way you put together your surroundings.

Style is something fun, individual. Or is should be. (Shouldn't the story you tell about yourself to the world, and to yourself, be fun, individual?) And style is also a process of self-discovery.

What I've been thinking about recently is how I want the three aspects of my style to work together. To express who I am, or think I am. I spent a lot of time being confused about that, trying to be who I thought I should be – who people seemed to want me to be. But at some point in your life you have to discover, or perhaps decide, who you are. And that's when you find your personal style. That's when you realized the story you want to tell the world about yourself.

And I think that's important – thinking about that story, because we do all have our stories, and we're always telling them, whether we're aware of it or not.

As for my personal style, well, you can see it all over this blog, can't you? And strangely enough, you can see it all over my books as well. I'm not quite sure how, because I haven't always had a say in how they looked, but they have that modern pre-Raphaelite look I love.

I know this isn't a particularly coherent post: I'm trying to talk about something I'm just beginning to think about, and that makes for some incoherence. But the idea of style as story is a powerful one – and one I want to explore further, because I'm a storyteller, and because I think stories are how we come to know ourselves.