Joe Friel's Blog, page 7

April 25, 2014

Basic Questions About Power Meters

A UK-based magazine recently asked me some questions for a piece they are working on regarding getting started with power-based training. I thought they were good ones, especially for those who are new to power or considering buying a power meter. Below are their questions and my answers.

On a related topic, TrainingPeaks.com just released a free ebook called How to Start Training With Power. It can be downloaded here.

And on yet another related topic, I wrote a book for the power newby called The Power Meter Handbook. It may also prove helpful in getting started.

Question: What type of cyclist can benefit the most from using a power meter? Are they best for serious riders or can newer cyclists benefit too?

Answer: I tell first year cyclists that their primary concern is training frequency. Just get out on the road as often as possible. After the first year and with frequent training well established, they should start focusing on workout duration. By about the third year of training with solid training frequency and duration at moderate to high levels the emphasis shifts toward training intensity. This is when a power meter will begin to pay big dividends. Up until this point in their budding cycling career a standard handlebar computer is all they need. This may include a heart rate monitor.

Question: Are they really better than heart rate monitors and if so why?

Answer: It’s not that they are better or worse, but that power meters are different. They measure something that can’t be determined from heart rate – performance. A heart rate monitor only tells the rider how great the effort is. This is a measure of “input.” Heart rate doesn’t say anything at all about what one is accomplishing. That’s where the power meter comes in with an “output” measurement. By knowing both output and input we know the cyclist’s efficiency. Dividing the Normalized Power (a high-fangled version of average power) from a standard aerobic ride or interval by the average heart rate for that same standard aerobic ride or interval the rider determines his or her Efficiency Factor (EF). (EF is something that TrainingPeaks.com calculates for you.) As EF rises over time we know that the athlete’s fitness is also rising. So not only do we know effort and performance, we now also know how to quantify aerobic fitness.

Question: What are the most important power numbers – FTP, PowerMax etc – we should be looking at when we’re training and racing and what are they telling us?

Answer: The single most important power number for the serious rider is his or her Functional Threshold Power (FTP). All of the rider’s training zones are based on FTP and it also serves as an absolute measure of performance potential. Several research studies have shown that the velocity or power one can produce when at or near the lactate threshold is an excellent predictor of endurance performance.

Over the course of the annual season FTP will rise and fall with training changes. When it’s rising one can assume that the potential for high performance is also rising. And the opposite is also true when it’s declining. It should be tested every few weeks to gauge progress toward race goals and to update training zones.

Question: How do power zones work - what are the benefits of working out in different zones?

Answer: The zones (Coggan’s system) are simply ranges within the full spectrum of power outputs that the rider can produce. They are divided into zones in such a way that each zone represents a critical physiological intensity. For example, zone 2 is typically about where the rider’s aerobic threshold occurs while zone 4 encompasses the anaerobic/lactate threshold. Zone 5 is the aerobic capacity (VO2max) intensity. By training in zones such as these the rider can pinpoint what physiological outcome he or she wants from a given workout.

Question: Is there a danger that you can become over-reliant on ‘numbers’?

Answer: Yes, certainly. The bottom line is always that a rider should be able to race well without any numbers on the handlebars. Using a power meter in training allows the rider to gauge progress and also to establish a “feel” for what the appropriate race intensities feel like. Even if the power meter was never used during the race, afterwards the rider can analyze the power data to see where there is room for improvement. For example, burning too many matches early in the race is a common flaw that the rider may discover during post-race analysis even if he or she never even glanced at the power meter during the race. Without such hard data race analysis is based entirely on perceptions which may be clouded by imprecise memory, macho beliefs, or poor guesses as to what happened and when. So even though it may not be used during the race, a power meter helps the athlete to grow as a racer.

Question: In what situations does having access to your power numbers really make a difference? Essentially how can you use power numbers to make you a better climber, ride better for longer or go faster!

Answer: During training the value of a power meter is immense. All workouts can be based on developing precise physical abilities or on achieving an adequate level of recovery. This includes improving climbing by focusing on a specific power zone and maintaining it throughout the climb (such as zone 4 during a very long climb). By using power it removes the guesswork as to what the intensity should be and if it’s being achieved. Then over the course of time the EFs from several such climbs may be compared to measure climbing progress (power should be rising at the same heart rate).

Within a race the most valuable use is during time trials and triathlons. For example, if doing a 40-km time trial that will take about an hour, the rider knows that this is best accomplished at his or her FTP. So by riding steadily (assuming flat terrain) at that intensity the best possible pacing and outcome are assured.

Question: Do you have any favourite power-based sessions for boosting climbing, speed or endurance?

Answer: The workout I have riders do the most frequently is the aerobic threshold steady state ride. After warming up the athlete will ride for a given period of time (in the range of 1-4 hours depending on the duration of the race he/she is preparing for) in zone 2 heart rate. Power is not observed during the ride. But afterwards Normalized Power and heart rate are compared to determine EF (as described above). The athlete has no way to manipulate the two variables so it is a pure measure of aerobic fitness when compared with previous EFs for the same workout or climb.

This same training concept using zones can be applied to any type of workout from sprints to time trials to short, steep hills.

Question: Are there any tricks to boosting your power output? Is it all down to building strength and losing weight or is there more to it than that??

Answer: Nothing in the physiology of training has changed just because the rider begins using a power meter. He or she is now simply better able to design and execute well-defined workouts, precisely analyze training and racing, measure performance potential, and determine fitness changes. All of these were left largely to guesswork before. For more than a century riders and coaches guessed at the progress being made in training. There was practically no way of knowing until race day. Cycling was the least scientific of all the major endurance sports throughout the last century. All training was based on feel and guesswork. Since the invention of the power meter cycling has arguably become the most precise endurance sport. Without a power meter the rider is still training as if it was 1900.

April 19, 2014

Airbus Symposium

On Tuesday this week I had the rare experience of speaking to a group of upper-level managers from Airbus at a resort in Travemünde on Germany’s Baltic Sea coast. Airbus makes commercial airliners used by all of the major airlines around the world. Their primary competitor is Boeing.

I don’t normally speak to a roomful of people who aren’t all skinny, serious athletes, although I later discovered that some of the managers were athletes. The 54 managers who attended are responsible for the final assembly of aircraft in Hamburg, Germany; Toulouse, France; Tianjin, China; and Mobile, Alabama. I got to take a tour of two of the Hamburg assembly lines. It’s quite impressive to see several huge aircraft being put together all in the same hangar. I can only imagine how challenging their work must be. Seeing the enormity of the operation made me quite glad that I don’t have a “real” job.

Their work responsibilities are enormous, and so you might expect that such a symposium would focus only on the technical aspects of production, such as engineering, personnel management and quality control. Yet the first day of the Symposium was devoted to a topic near and dear to my heart – health. The Symposium was designed by Alexander Dahm and his staff. Alexander is the vice president of the Airbus final assembly. He is quite a rare person. He understands the importance of employee health to the health and performance of the company. All of the day 1 topics were designed with healthy leadership in mind.

I spoke on the importance of exercise through sport for health. This is an important topic given the current state of citizen health in all of the countries represented at the event. My fellow US colleague, Nell Stephenson, talked about the role of nutrition in health. Florian Wolf from YourPrevention talked about the role of stress management in an occupational setting.

The managers were encouraged to workout in the mornings prior to breakfast and the first session. Different athletic activities were provided for this from group runs to yoga classes and strength training. All meals and snacks were designed by Nell and prepared by the resort’s chef. They were delicious – and healthy.

The first evening, after a full day focused solely on health, Jens Maier, PhD of the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland, spoke during dinner on the leadership role of production line managers. The next day back in the classroom he took the topic to the next level.

This was my first presentation to a corporate group, but I found it quite energizing. For the two days I was there individual managers would corner me to ask personal questions about their own health, exercise and diet. Most wanted to talk about common challenges that many athletes face: how to fit exercise into a busy day, trying to find the right type of exercise given a body that isn’t perfect, getting their families onboard especially with dietary changes, and managing body weight. I look forward to hearing the impact of this initial phase and the long-term project for improving Airbus employee’s health and work performance.

April 2, 2014

Recovery for Runners

Some time ago a magazine asked me some questions about recovery for runners for a piece they were writing. Recently an athlete asked similar questions and got me to thinking about this topic once again. The topic is a critical one for runners due to their propensity for injury. But recovery is also of great importance to athletes in other sports. Here are the magazine's questions and my answers.

Q: How important are recovery days for recreational athletes? Is there a difference in recovery for someone training for her first 5k, and someone training for her first marathon?

A: There are two types of recovery - passive and active. Passive means rest with no physical activity. This is generally best for novices. Taking a day off from exercise will allow the novice's body (and mind) to recover and grow stronger. Working out will almost certainly be too fatiguing for the already tired novice athlete.

Active recovery is often better for the experienced and highly fit athlete. This means doing a short, low-intensity workout. The intensity part is easy. That means zone 1, for example, if using a heart rate monitor or GPS pacing device. A "short" workout may vary greatly between athletes. For someone training 12 hours per week "short" may mean 45 minutes. For another athlete who does about 4 hours weekly "short" is more likely something such as 10 minutes. Experienced athletes also need passive recovery days from time to time, just not as frequently as novices.

If in doubt about what to do - passive or active, 45 minutes or 10 minutes - be conservative. It's always better to err on the side of too little rather than too much when it comes to training.

Q: Why should a runner resist the temptation to run day after day, with little or no breaks?

A: It always concerns me when someone tries to set a record of running some pre-determined number of days without a break. That's not good for either physical fitness or mental health. Typically, something bad is going to come of this. I have always had everyone, even the pros I've coached, take periodic breaks from training. These breaks generally occur weekly, monthly, and annually. This usually leads to performance improvements for it’s during rest that the body grows stronger.

Q: On recovery days from running, is it OK for a runner to participate in non-impact cross-training, like swimming or yoga?

A: It's alright for experienced and highly fit runners to cross-train. In fact, this is the best option for most runners on a recovery day. Running is orthopedically quite stressful. The joints take a real pounding, especially when the surface is pavement. While the course surface may contribute to injury, several consecutive days of running have been shown to be the most common reason for running injuries. On the other hand, swimming and cycling are very low stress activities and can help to maintain cardiovascular fitness on an active recovery day. There are other low-stress modes of exercise that also may be used, such as stair climbers, cross-country skiing, and elliptical machines.

Q: What tools do you most recommend to aid in recovery?

A: The most effective ways to recover are sleep and nutrition. In terms of sleep, if one has to use an alarm clock to get up in the morning then sleep is insufficient. The solution is to go to bed earlier. Most of us need around 8 hours each night; some need more. As for nutrition, the first order of business following a workout for most athletes is carbohydrate along with some protein. Beyond the initial recovery period (which may last several hours depending on the preceding workout) the most critical nutritional components are micronutrients - vitamins and minerals. In their order of micronutrient density, the best foods are vegetables, seafood and fruit. Again, sleep and nutrition should always be the first considerations when recovery is needed. Other commonly used passive recovery methods are massage, stretching, floating in water, alternating hot- and cold-water immersion, icing, leg elevation, compression stockings, pneumatic compression devices, and others. The benefits of some of these are not well-established by research, but all of these are commonly used by athletes of all abilities.

March 27, 2014

Personal Update

It’s been almost three months since I lasted posted anything here. That’s a record for me, and I’ve been pretty good over the years at leaving big, empty gaps from time to time. This gap has been mostly due to the usual excuse – work. I’m writing what will be my 14th book in 18 years. It’s based on the long “Aging” series I posted to my blog last fall starting here. I spent June through October last year reviewing the latest research on the subject and writing about what I was learning every few days. I learned a lot and hope to share it with you. As you might guess, the topic of the book currently in progress on my Mac is about senior – over-50 – endurance athletes. I’m really enjoying writing it but it takes a lot of time to do it right. Tentatively it will be called “Fast After 50” and will release about the end of the year.

I also put on a seven-day triathlon camp in Mallorca, Spain last week. With preparation, admin, and follow-up there was little time for anything else for about two weeks.

But those aren’t the only things that have kept me away from this blog for so long recently. The biggest consumer of my time in the last nine weeks was related to recovering from a bike crash on January 24. That resulted in seven broken bones including the clavicle and scapula, a concussion, blood clots in both legs and lungs, a partially torn rotator cuff and shoulder labrum, and what docs call “adhesive capsulitis” (also called “frozen shoulder”). After six days in the hospital trauma center, all of these injuries required numerous trips to various medical specialists, X-rays, CT scans and an MRI. Then there have been three weekly visits to my physical therapist (Endurance Rehab) going on since late February. All of this left little time for anything else.

As I know some will be interested, here’s what happened with my crash. There may be a lesson here for someone other than me. On January 24 it was a windy morning in Scottsdale, Arizona. In fact, there was such a strong wind that I considered not even riding. But being the typical greedy athlete (I was less than one TSS point from breaking a CTL of 90 – my highest ever in January) I decided to press on. I had ridden in strong winds before. I was about 36 minutes into an easy two-hour recovery ride when a very strong, rogue gust of wind hit me from the left side as I was going down a slight hill at around 25 mph. It blew me into the curb. As near as I can tell the bike flipped and I landed on my left shoulder and side. I have no memory of anything from the time when I realized I was about to crash until four hours later when I awoke in a hospital bed. I think riding with Zipp 404 wheels was related to being blown off the road. These rims are quite deep providing a kind of sail effect (I have since purchased Zipp 101s which have a smaller rim).

I was fortunate that the driver in the car behind me was also a cyclist. He stopped to help, called 911, then checked my wrist ID and called my wife. Had I not had an ID on and being unconscious, my wife wouldn’t have known about it for at least four hours. I highly recommend wearing an ID bracelet when training as you never know what might happen.

I won’t bore you with more details as I’m sure that if you’re a cyclist you’ve also had your share of crashes and don’t like to read about them. I know I don’t. So let’s move on.

In two weeks (April 10) I’m speaking in Parsippany, New Jersey for the Tri City Orthopeadic Center. For more details go here. If you live in the area, I hope you can make it. And the following week renown Paleoista Nell Stephenson and I have been invited to speak to Airbus (aircraft manufacturer) upper management at their Global Leadership Symposium in Hamburg, Germany. That’ll be fun!

But with this travel it’s likely you won’t here from me again for some time. We’ll see.

January 2, 2014

Recovery and Intensity Factor

I received an interesting question from an athlete today. He asked...

Question: "Is there research available on recovery time vs. Intensity Factor (IF)?"

Explanation: "IF" is a TrainingPeaks and WKO+ term which refers to how hard a workout is relative to the athlete's Functional Threshold Power (bike) or Functional Threshold Pace (run, swim, etc). FTP is similar to anaerobic or lactate threshold--the level of intensity just below the effort at which lactate begins to accumulate. It's when you start to "redline." IF is expressed as a percentage of FTP. So if, for example, your FTP on the bike is 250 watts and you rode your bike during the entire workout at an average of 200 watts, your workout IF would 80% (200 / 250 = 0.8). It's a nice way of talking about how hard a workout was.

My answer: "That's an interesting question. No, I've not seen any research precisely on the relationship of IF and rate of recovery. But as with all things in exercise physiology, the answer would be highly dependent on many factors, mostly related to individuality. For example, one such individual determiner would be what the physiological predisposition of the athlete is as compared with the type of workout done. For example, if the athlete is better adapted to aerobic stress as opposed to anaerobic, and the workout's IF was primarily based on anaerobic intensity, then the rate of recovery could be expected to be slower than for another athlete who is more anaerobically inclined. The opposite pairing would also be true, I believe. And there are many, many more such individual markers of recovery such as age, diet, experience, prior training, type of exercise, sleep, psychological stress, lifestyle, etc. The topic of recovery is very complex."

Conclusion: I don't know.

December 9, 2013

Hard-Easy Training

“Polarized training” is a fancy new name for a basic old concept—train either at low or high intensity, but keep the moderate training time between these extremes relatively small. So what are low, moderate and high intensities? All of the recent polarized research studies define them, usually using heart rate as the standard, as follows…

Low. Called “zone 1.” Below the ventilatory threshold which is, essentially, the aerobic threshold (AeT). AeT is best determined in a lab test. It’s very roughly 30bpm below your anaerobic threshold (or lactate threshold, functional threshold, etc). This is a very easy workout that is commonly used for active recovery. (The reference to zones here is strictly for the purposes of these studies and not the same as the zones normally used by athletes.)

High. Called “zone 3.” Most of the studies use the respiratory compensation threshold. For our purposes, that is the equivalent of your anaerobic threshold (AnT). AnT is the intensity above which breathing becomes labored. This is a very hard workout intended to improve performance.

Moderate. Called “zone 2.” As you might have guessed by now, this is the range between AeT and AnT.

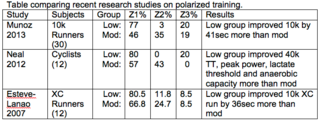

The most recent study on this subject was reported in the May 2013 edition of the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance (1). A group of researchers from the European University of Madrid assigned 10k runners to either a polarized (emphasis on low intensity—zone 1) or a between-thresholds (emphasis on moderate intensity—zone 2) training protocol for 10 weeks. After the training period they repeated a 10km race on the same course used to establish a baseline before the 10-week period began. Both groups improved their performance times, but the polarized (low-high/zones 1 and 3) improved by 41 seconds more than the between thresholds (moderate-high/zones 2 and 3) group. The high intensity training time was about the same for both groups. The only thing that differed was how much time was spent in the low (z1) and moderate (z2) ranges.

The accompanying table summarizes this Spanish study along with two other older studies that followed a similar protocol (click to enlarge). Note that the groups which trained low-high performed better in the post-tests than the groups that trained moderate-high—in all three studies. (You can read the abstracts for each of the studies by clicking on the references below.)

Two other studies in the last few years took a look at how athletes distributed their intensities as they trained for real-world competitions. The first of these, from the same Spanish researchers again, followed 8, sub-elite, young (23 +/- 2 years old), male runners as they prepared over a 6-month period for the national cross country championships (4km and 10km) (4). Their average intensity distributions were:

Z1 = 71.3%

Z2 = 21.0%

Z3 = 7.6%

The researchers found that there was a close correlation between how much time was spent in zone 1 and performance time. In other words, the more zone 1 training, the faster they raced.

A second study out of Norway followed 11 junior Nordic skiers for 32 days of normal training and observed their intensities based on heart rate, ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) and lactate samples (5). The distributions for each of these testing methods was remarkably similar so I’ll just report heart rate distribution as the other studies have done:

Z1 = 75%

Z2 = 8%

Z3 = 17%

Following athletes as they train in the real world is often more revealing than lab studies. Note that the runners in the latter Spanish study did relatively little zone 3 training having 92% below AnT (combined zones 1 and 2). This is what I would expect to see from self-coached athletes. The Norwegian skiers had coaches, as we can tell from the lactate samples being taken. Note that they appear to have polarized the training intensities quite nicely.

One take-home message here is that there is nothing wrong with training below your aerobic threshold. In other words, really easy. Recovery is important. Too many athletes think the way to better performance is to raise the intensities on their recovery days. Not good. Easy, recovery workouts must be done in zone 1. And due to a lot of one’s training time being spent in zone 1, the quality of the high-intensity workouts (zone 3) improves. Doing a lot of zone 2 for recovery may well detract from your capacity to do the more valuable training above the anaerobic threshold.

Actually, I wish it was that simple. In the real world there are races done right smack-dab in zone 2, between AeT and AnT. For example, the race intensities of marathons, half marathons, Ironman and 70.3 triathlons all fit into this category. In fact, almost any race longer than an hour is a zone 2 event. One exception is road cycling in which the outcomes are determined largely by zone 3 (>AnT) efforts even though the race is mostly zone 2. So should you avoid training in this “toxic” zone? Perhaps not. It depends on what you are training for. As I continue to hammer home: You must prepare for a race by making your training increasingly like the race as you get closer in time to it.

The bottom line here is that the real issue is hard-easy training, not necessarily training predominantly in zones 1 and 3. It just so happens that each of the cited studies used subjects training for relatively short events. But that may not be you. Chances are it isn’t. So let’s say you are training for a 70.3 triathlon. Doing a workout with several 20-minute intervals in zone 2 (between AeT and AnT) with short recoveries could easily be a hard workout and yet not exceed AnT.

So “hard” is best defined relative to what you are training for and what the total stress load of a given workout may be—not necessarily what heart rate zone you were in. “Easy” is more easily defined, regardless of event duration, as being below your AeT.

Are you training in this way? The challenging part for most athletes is getting a lot of zone 1 time. But that’s the starting point. The quality and volume of your “hard” workouts will never be hard enough if you insist on trying to recover above your AeT.

References

November 27, 2013

Aging: The Last Post

This is my last aging post. I started this series back in June as a pre-birthday gift to myself. I wanted to understand what was happening with my performance that seemed to be in decline. There was a very good chance that what I saw happening was age-related as I approached my 70th birthday (next month). I wasn’t seeing a big drop off in performance, but there were little things going that I couldn’t explain. The most significant of these was an inability to regain my normal long- and short-duration bike power outputs of previous years. So I began to dig into the aging-athlete research of the past 20 years to see if I could find answers.

The amount of research on aging has grown tremendously since I last seriously reviewed it in the mid-1990s as I was writing a book called Cycling Past 50. That book grew out of the same quest for understanding of getting older as I moved into my 50s. Because of this recent blog series I know a lot more about the topic than I did then. In fact, that book now seems rather naïve and touches only on a few high points of the discussion. That’s because there’s been a much greater need for society to understand its senior citizens as the Baby Boomers reached their 50s and 60s. Now that those same post-WWII babies are approaching their 70s they are changing the world. For a number of reasons they are much more physically active than any previous generation. That has its upsides – longevity and quality of life – but also has some downsides, such as placing long-term demands on the medical system. For those of us interested in maintaining performance with aging, we’re learning a lot about how to train by observing what happens with the best of the Boomer athletes. That’s what I focused on with this series.

I never thought this series of aging blog posts would go on for six months. At the start I had no idea there was so much to write about. In this series I've only touched the surface of the topic. So I’ve decided to write another book for aging athletes. This one won’t be just for cyclists, as the first was, but for senior athletes in all endurance sports such as triathlon, road cycling, mountain bike racing, running, swimming, Nordic skiing, rowing and paddling. In this book I’ll tweak what I’ve written about in my blog as the questions you’ve asked have helped me to focus. So if you read the book you’ll find some of the same information you’ve been reading here, only with a different twist. There will also be a lot of topics that weren’t included in the blog, such as the latest aging research and my observations on:

Diet and muscle maintenance

Nutrition in recovery – both long- and short-term

Acid-base balance and bone density

Effects of strenuous training on the heart

Menopause and performance

Training with osteoarthritis

Unique mental approaches to training with aging

Motivation and aging

Determining performance potential as a senior athlete

Age-specific performance measurement

I’ll also write about what I’ve learned and my personal performance improvements that came from it. It’s been an eye-opening project for me. And I’m looking forward to sharing it all with you. But it won’t be available right away. While writing the book won’t take that long – perhaps 6 months – the editing, printing and distribution will take many more months. Don’t expect to see it before the end of 2014. I’ll certainly let you know when it’s available.

Until then it’s back to normal blog posts here on topics related to training and performance regardless of age. Thanks for hanging in there with me through all of this.

November 21, 2013

Aging: The Veteran’s Transition Period

So far I’ve covered all of the common periods in the season and how they might be tweaked to match the unique needs of the senior athlete – Prep, Base, Build, Peak and Race. That brings us to the last period of the macrocycle – Transition. This one is easy to explain because not only is it inherently simple, there are also no tweaks in it due to age. So what I described in my Training Bible books may be applied regardless of age. But just in case you don’t have one of those books (shame on you!), I’ll explain it here.

The Transition period is so named because it serves as the bridge between the previous macrocycle – the one that just ended with the last race of the season – and the next macrocycle that will prepare you for your next A-priority race. Its purpose is to give you a much-needed break from the singular focus on structured and challenging training. An athlete who spent the previous several months working hard needs mental recovery as much as a physical break. The desire for rest and a lifestyle change, albeit short-lived, is a good sign that the athlete gave it their all in the previous macrocycle.

As for training in the strictest sense of the term, there is none in the Transition period. That doesn’t mean you should all of a sudden become a couch spud. Continue to exercise, but do not “train.” Exercise in this case means short duration, low intensity and done only for fun. Don’t exercise if you don’t feel like it. There is no planning. Decide every day what you will do, if anything. An alternative sport is often a good idea. For example, if you are a runner, go for bike rides or swims or whatever you feel like doing mixed in with a little running. Dismiss the feeling of guilt because you aren’t training hard. All of this low-key approach now will pay off with better mental focus and enthusiasm as you return to training later. Getting started too early on the next macrocycle may eventually come back to haunt you in the form of burnout – the mental burden of seeing no end to this concentration on high performance.

Besides providing a break from training, the Transition period also gives you the opportunity to evaluate how the previous macrocycle went. Good questions you might ask yourself now are: If I did it over again, what changes would I make in my preparation? What did I learn about myself and the sport?

The Transition period may be as short as five days or as long as two months. The shortest periods are typical after in-season races when you have another one coming up in a few weeks. The longest Transitions usually occur at the end of the season. For example, if you have two A-priority races in a season separated by, let’s say, two months, you may have a five-day Transition after the first and after the last race take a much-needed break of four weeks.

For the senior athlete it’s alright to now omit the workouts I’ve emphasized you should have been doing throughout the season – strength training and high-intensity aerobic capacity workouts. But I’d suggest going no longer than about four weeks without doing these. You need a break. So if your Transition period lasts for longer than a month, begin reintroducing such training after four weeks. Use the fartlek workout type I described earlier and keep the total high-intensity in a single, weekly workout on the low end, around three to five minutes. Strength training should resume with the Anatomical Adaptation (AA) phase (scroll to bottom of page here). Some athletes may be able to reintroduce these earlier in Transition and some later. Only you, and perhaps your coach, can make that decision. There’s some wiggle room here.

So what should you do if you have planned an A-priority race following your “regular” season, perhaps in a related but somewhat different sport (such as triathlete running a marathon or a road cyclist doing a cyclocross race)? This presents a huge problem if you are mentally and physically drained at the end of your season. In that case you certainly need a long Transition and another race jeopardizes your next macrocycle. But if you have committed to another race you may have to shorten or forego the Transition period. Sometimes that works out alright and other times it’s a great mistake. So what should you do? There is no one-size-fits-all formula for solving this conundrum. The options are 1) to start training after a very short Transition and take your chances that you’ll come through it ok with no deleterious effects on the next regular season, and 2) change the next race from A- to B-priority and get some much-needed rest and recovery now. Then do what you can with the remaining time to prepare for the race. If you choose option #1 I can’t tell you how to periodize the preparation. There are far too may variables to offer a solution that fits everyone. Only you (or your coach) know enough to decide that.

So that’s it. In my next post I’ll wrap up all of this aging stuff and tell you where it’s leading me. Stay tuned.

November 13, 2013

Aging: Customizing the Race Period

We’ve now got the Prep, Base, Build and Peak periods behind us. We’re almost there: The race is just a week away. Actually, there isn’t much to change in this period from what’s described in my Training Bible books.

Let’s start with how to set up a routine for the week of the race. In my next post we’ll take a look at the Transition period. This last one’s a piece of cake.

The last few days before the race is called the Race period. Not only is it short – just 6 or 7 days typically – it’s also simple. For the veteran senior athlete the purposes of this period are to 1) maintain the aerobic capacity and strength gains of the last several weeks, 2) eliminate any remaining traces of fatigue and 3) prepare mentally and physically for the race. To accomplish these objectives I’ve been using a race-week routine for several years that stays the same regardless of the endurance sport or it’s distance. It’s proven to be quite effective with a wide variety of athletes and events.

What I’ve been doing grew out of a research study by Canadian triathlon coach Barrie Shepley and associates at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. The researchers divided a group of well-trained, collegiate, cross country runners who ran 45 to 50 miles per week into three sub-groups for a one-week taper before a race. Group 1 stopped training and rested all week. So they reduced all three workout variables: duration, frequency and intensity. Group 2 ran 18 miles total for the week at a slow pace. So they reduced workout duration and intensity for 6 days. Group 3 is where it becomes interesting. They ran 5 days in a row and did not train at all the day before the race. On each of those 5 running days they warmed up and then ran 500m work intervals at their goal race pace with 6 to 7 minutes of recovery between them. Here’s their routine. With 6 days to go until the race they ran 5 of these intervals. The next day they did 4. Four days prior they did 3 intervals. With 3 days to go they ran 2 intervals. Two days before the race they ran only 1 of the 500m intervals. Then the day before the race they rested completely. So this group reduced workout duration by tapering it a bit every day while keeping intensity high. The “race” was a test to see how long they could run at their maximal-effort 1500m pace they had done in a pre-test before the taper started. So what happened? Group 1 (total rest) did not improve their performance at all. In fact, they covered about 3% less distance. Group 2 (reduced duration and intensity) improved the distance they could run at their previous 1500m pace by 6% (105 meters). Group 3 (tapered duration with race-intensity intervals) ran 22% farther (387 meters). Impressive!

Here's the take-home lesson from Shepley’s study. In the Race week period the first thing that must happen is a reduction in training volume. That should primarily be done by reducing the duration and possibly the frequency of training, but not the intensity (Houmard). Intensity is the key to a successful race week. It must be maintained at race effort (or pace, power or heart rate). To workout at a low intensity – even if you reduce workout duration and frequency – will result in a rather large drop in fitness and race-day performance. Do not reduce intensity.

But, of course, the study used college-age athletes. That's quite common since researchers at universities have easy access to a lot of young people. What about us old geezers? Does such a routine work just as well for us? There's no such research, or least none I've found. My experience has been that it works just as well for seniors. I’ve used this training pattern for many years with athletes of all ages across a variety of sports. It’s typically proven to be successful. But I’d suggest making some adjustments. Note in the following example that I’ve made some small changes in what Shepley used in his study. Each of the following workouts is preceded by a warm-up and finishes with a brief cool down.

Monday

Fartlek with 3 minutes total of aerobic capacity pace, power or effort and one very brief Strength Maintenance (SM) session in the gym

Tuesday

5 x 90 seconds at goal race intensity (minimum of zone 3) with at least 3 minutes of recovery between intervals

Wednesday

4 x 90 seconds at goal race intensity (minimum of zone 3) with at least 3 minutes of recovery between intervals

Thursday

3 x 90 seconds at goal race intensity (minimum of zone 3) with at least 3 minutes of recovery between intervals

Friday

Day off

Saturday

1 x 90 seconds at goal race intensity (minimum of zone 3)

Sunday

Race

The above is for a Sunday race. For a Saturday race keep Monday the same but move Wednesday’s workout to Tuesday, Thursday’s to Wednesday, etc.

“Goal race intensity” is generally easy to determine for triathlons, time trials and running races since they are typically fairly steady pacing – or at least should be. For an event that has more variable pacing, such as a bicycle road race or mountain bike race, this may be the highest intensity demanded of you on race day. Or it could be the goal intensity for a critical portion of the race such a particular hill. If that intensity will be in one or more brief episodes lasting less than 90 seconds then adjust the length of the intervals above appropriately. By race day you should have a great “feel” for race goal intensity which improves your chances of getting it right, especially at the start when goal race intensity is usually screwed up. Having rehearsed race intensity and many of the details of your race almost daily for the past two weeks you should also feel mentally prepared for competition.

Triathletes present a unique challenge to the above routine. They may do two workouts each day and divide the intervals between the two sports (for example on Wednesday swim with 2 x 90-second intervals followed by a bike ride with 2 x 90-second intervals). This is probably most beneficial as combined swim-bike or bike-run sessions so transitions can also be practiced. For most triathletes the critical sport is the bike so doing that every day isn’t a bad thing. The day before the race I’ve often had triathletes do all three sports with 1 x 30-second effort at race intensity in each.

Regardless of your sport, do not increase the number of intervals or reduce the recovery time between intervals in an attempt to make the workout harder. Rest – not more fitness – is the essential now. The only purpose of the intervals is to maintain fitness while becoming completely familiar with the goal race intensity. You’re not trying to improve it.

You probably noticed that I moved the day off to two days before the race rather than the day before as Shepley had done. At one time I scheduled the day before as a rest day but so many athletes reported feeling “flat” on race day that I changed it. That seemed to resolve the problem. And since we often travel to races two days prior, the day off comes at the right time.

I’ve found this to be an effective way to train the week of the race for athletes in a wide variety of sports. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t tweak it to better fit your unique situation. Feel free to experiment. But always bear in mind that the goal is shedding fatigue, not gaining fitness.

References

Houmard JA. 1991. Impact of reduced training on performance in endurance athletes. Sports Med 12(6):380-93.

Shepley B, MacDougall JD, Cipriano N, et al. 1992. Physiological effects of tapering in highly trained athletes. J Appl Physiol 72(2):706-11.

November 9, 2013

Aging: Customizing the Peak Period

The Peak period follows Build 2b and is one of the shortest of the

season. Now you’re down to just a couple of weeks until race day. Gaining

fitness is out of the question. There isn’t enough time to have a significant

effect and, besides, the cost of recovery is now becoming too great. Your mindset must change in order

to accomplish the two objectives of this period:

Peak Objective #1: Shed

fatigue. Over the past several weeks

of the Base and Build periods the stress of training was at times quite high

with key workouts every second or third day focused on aerobic capacity,

strength, aerobic and muscular endurance and race-like training. Your training

volume may have also been high. Despite frequent R&R microcycles there was

undoubtedly some deep fatigue accumulating. You’ve become so accustomed to it

that you may not even realize just how tired you are. Now, in the Peak period,

by gradually getting rid of that fatigue and becoming fresher you will come

into “form.”

Peak Objective #2: Maintain

fitness. When you reduce the

training load by cutting back on training duration, which is only one of the

three workout variables you can modify (the others are intensity and

frequency), fitness is gradually lost. You can’t gain fitness by training less.

If you could then sitting on the sofa and watching TV would be a key workout in

the Base and Build periods. But it’s understandable that athletes would think

they are gaining fitness by tapering their training. If only a little fitness

is lost but a lot of fatigue is shed over the course of several days, you will

certainly feel fitter. And, if

everything goes right, you’ll also race faster (Mujika). This is called “strong form.”

The tricky part is to shed most all of the fatigue while losing

very little fitness. The way to do that is to make big cuts in workout duration

(Banister, Kubukeli) over what you’ve been doing in the Build period while

doing a challenging race-like intensity workout every third day (Neary) - the red days above. The

race-simulation sessions should also gradually get shorter. This will bring you

to a peak of race

readiness.

As you did in the Base period, include some aerobic capacity

fartlek in one of these sessions in the Peak microcycle. It won’t take much to

maintain your seasonal gains. A total of 3 to 5 minutes of zone 5 (power, pace

or effort – heart rate is not an

effective way to gauge intensity for such brief intervals) in one session

should do it. This could be done during or following a race-like simulation

workout. Also including one Strength Maintenance (SM) gym session (see details

for cycling or triathlon) early in this microcycle should also be

adequate to maintain your strength gains.

For the senior athlete I’d suggest using a Peak period shorter than

that explained in my Training

Bible books. There the standard Peak mesocycle duration was

described as 14 days. But since the senior athlete is likely to lose fitness at

a more rapid rate when tapering in Peak (my opinion as there is no research on

this), I’ve shortened this period to 9 days regardless of whether the athlete

has been using a 9- or 7-day microcycle pattern previously. That means 5 fewer

days of tapering than I recommend for younger athletes.

Note that each of the following examples starts with the day where

the previous examples left off in the Base period post. (If you’ve been closely following this daily

progression you’ll notice I’ve made a two-day adjustment here in the 9-day Peak

microcycle as I found a previous error.)

Former 9-day microcyles (9 days total for Peak)

Peak Mesocycle – 9

days (S,

S, M, T,

W, T, F,

S, S)

Former 7-day microcyles (9 days total for Peak)

Peak Mesocycle – 9

days (S,

S, M, T,

W, T, F,

S, S)

The red days highlighted above (Sunday, Tuesday, and Friday) are the days I’d suggest doing

the key Peak workouts. These are the race-simulation sessions with one of them

including a few minutes of aerobic capacity fartlek for maintenance. Sunday or

Tuesday in the example are the best days for this. And one red day would also

be a day when the SM strength session is done. The gym workout is best done

after the sport-specific session or several hours before.

The two days following each red day are for recovery. They should

both be short - for you - and low intensity (zones 1-2). As with the red days, these

recovery sessions get shorter as the Peak period progresses.

By following such a routine you should feel quite rested at the end

of the 9 days. If you’ve never tapered like this before you may also feel quite

apprehensive. It’s not emotionally easy to reduce training so much right before

a big race. But it’s critical that you do as it’s likely that fatigue will

reduce your performance potential. You must be rested to race near your

potential.

As the Peak period comes to a close you should be ready to move on to the last few days leading up to your race. In the next post I’ll take a

look at the Race period relative to the senior athlete's unique needs.

References

Banister EW, Carter JB, Zarkadas PC. 1999. Training theory and

taper: Validation in triathlon athletes. Eur

J Appl Physiol 79(2):182-91.

Kubukeli ZV, Noakes TD, Denis SC. 2w002. Training techniques to

improve endurance exercise performances. Sports

Med 32(8):489-509.

Mujika I, Goya A, Padilla S, et al. 2000. Physiological responses to a 6-d taper in middle-distance runners:

influence of training intensity and volume. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32(2):511-7.

Neary JP, Martin TP, Quinney HA. 2003. Effects of taper on

endurance cycling capacity and single muscle fiber properties. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35(11):1875-81.

Joe Friel's Blog

- Joe Friel's profile

- 91 followers