Joe Friel's Blog, page 2

January 12, 2018

Sleep, Part 2

I apologize for the long gaps between posts to my blog. Even though I am now retired from one-on-one coaching it seems there’s still never any time for writing here. But one thing I seldom pass up in the daily bustle is sleep. In Part 1 on this topic I railed against athletes having so many responsibilities in their lives that they have to cut out something, and that, unfortunately, is usually sleep.

As I tried to explain in Part 1, giving up time in bed means a reduction in your adaptive response to training. That means you don’t reap the full fitness benefits of the day’s workout. It’s during sleep that the good stuff you want happens. Your fitness increases as naturally occurring anabolic (“tissue-building”) hormones are released. This is why I often say that hard workouts don’t make you more fit—they only produce the potential for increased fitness. It’s during recovery, especially sleep, that this occurs.

Hormones are released in waves in certain sleep cycles during the night. There are several repeating cycles as you doze. The two that seem to be most productive, as far as increased fitness due to hormone release, are the rapid-eye movement (REM) and deep sleep cycles. These are when scientists who study sleep agree that tissue-building hormone production is greatest resulting in adaptation to the physical stresses you experienced that day. REM sleep seems to be especially critical. It happens about every 90 minutes to two hours and lasts only a few minutes at a time making up perhaps 20 to 25 percent of your sleep time—if you have a full night of sleep. And, curiously, REM sleep appears to occur mostly late in sleep—in the final hours before you wake up. So artificially shortening your sleep with an alarm early in the morning may well be costing you fitness. A portion of the previous day’s workout was for naught.

All of this is why, when I was coaching, I urged my clients to get as much sleep as they could. Adequate sleep means greater fitness and that means improved race performance and, therefore, goal achievement.

And I should make one other important point here. A common thought among athletes is that they can cut their short sleep Monday through Friday and then “catch-up” on the weekends. It doesn’t work that way. You can’t hold hormones in reserve for a few days and then release them in larger quantities later on. The daily opportunities were simply lost. It’s good to sleep on the weekends, but that doesn’t mean everything having to do with adaptation is therefore going to balance out for the week. It was just lost opportunities.

So how do you know if you’re getting enough siesta time? If you are waking up naturally—no alarm clock—then you are probably doing pretty well in regards to the benefits of sleep. That probably means around seven hours in the sack. But if you’re like most of the athletes I coached over the years, you’d like to see the data that supports this assumption. The best I have found is a device called Emfit QS. It measures and reports your nightly sleep-cycle durations and much more, such as total sleep time, heart rate patterns throughout the night, heart rate variability, breathing patterns, sleepless movement, and more. All of this appears on your smart phone once you are out of bed for the day.

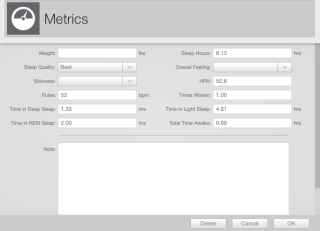

The most basic sleep data is also automatically uploaded to your TrainingPeaks.com account every morning as shown here.

It’s simple to use, which I really like. No chest strap or other devices to wear. No manually turning it off and on. You just go to bed and it starts working. The device looks like a short belt that is placed between your mattress and box springs beneath where you sleep and perpendicular to your body position when in bed. It’s then connected to your local Wi-Fi network. Once set up you never have to touch it again. It’s pretty amazing that it can check all of these parameters given my 14-inch mattress and yet never appears to include my wife’s data from the other side of the bed. Is the data accurate? I can’t say as I have nothing to compare it with. But if it is simply dependable that is ok by me.

The downside, as with many of these amazing high-tech devices on the market these days, is cost. The cheapest I’ve found is $235 on Amazon.

The bottom line, whether you actually measure your 40 winks or not, is that to fully reap the benefits of your training, lengthy and regular sleep is necessary. Artificially shortening your nightly sleep means less fitness and reduced performance.

December 2, 2017

Sleep, Part 1

I’m now retired from hands-on coaching. It was challenging work for thirty-plus years, mostly because there was never a break. All of the athletes needed unwavering attention whether I was on vacation or not. Yet I still tremendously enjoyed it and, in a sick sort of way, now miss the pressure of preparing an athlete for competition. What especially made it so hard was that, for the most part, I coached athletes who had very high goals—podium at a national championship, qualify for Ironman Hawaii, win a highly competitive race, set a personal best time, or whatever. What really made it so challenging was that for most of the athletes I coached such goals were near the high end of their athletic potential. To improve their chances of succeeding we had to get everything right. That wasn’t just their workouts, but also their lifestyles. The latter was by far the more difficult thing to align with their goal.

To achieve such goals the athlete invariably had to agree to make lifestyle changes. They usually did so willingly. But this meant I had to get to know them quite well and then make suggestions about what had to change. That usually involved the primary aspects of life that affected performance and, especially, recovery. It required understanding and possibly altering their nutrition, friend and family support, the mental aspects of training and racing, physical limiters such as a propensity for injury or physiological imbalances, and lots more. Most athletes were quite willing to address and attempt to correct such limiters. The one that was always most difficult to correct was their sleep schedules. Yet this was almost always the most critical to their success as sleep is when adaptation (read: “increased fitness”) occurs. Without adequate sleep, adaptation is severely restricted.

It’s not that they were opposed to sleeping more, as I almost always had to suggest, but that they simply had so much stuff in their lives that “had to get done” every day. It was nearly always the same: career, family, personal time, other responsibilities, and training. There was never enough time in a day for everything they wanted to do. Something had to give. The most flexible time constraint was almost universally time spent in bed. So they chopped off the needed time there—before I came along. They typically got to bed late for a myriad of quite good reasons. Then they set an alarm to go off a few hours later so they could get going again on their list of daily must-does. They saw sleep as an interference—something that must be done but was sort of a waste of time. I can’t tell you how many times I was told that, “I can sleep when I’m dead.”

That may be the case. And, in fact, shortchanging sleep may well lead to an early grave. I can’t support that with research, don’t know of any, but I can support what limited sleep means to performance. It isn’t good. And the older you are, the more of a problem reduced sleep time is when it comes to high performance.

Personal example… When I was a college student I was on the track team. Training in the 1960s was nothing like today. Our coach knew only one way of training. Back then I called it “intervals ‘til you puke.” We’d warm-up and then he’d blow his whistle meaning we should all report to him where he was seated in the bleachers at the track sipping a Coke. We knew what was coming next. After a few comments from him on our next competition he’d tell us to line up on a mark he’d made on the track with his foot (it was cinders back in those days). We knew what was next. We were going to do 440-yard intervals (there were few 400-meter tracks in the US back then) until he decided we’d had enough. There was never any discussion of goal times we should be aiming for—only that we should “run faster.”

Everything about the workout was entirely by the seat of his pants. We never knew how much recovery we’d get between the fast intervals. It could be a few seconds to a couple of minutes. We just stood bent over with hands on knees breathing heavily after each one as he told us how slow we were. Then he’d say, “line up” and we’d do it again. We may do 10 x 440, or 15 x 440, or 20 of them. We never knew in advance how many. When he got tired of blowing the whistle we were done. The only other thing that seemed to affect that decision was our reaction to the workout. But in a weird sort of way. When runners started throwing up we knew the end was in sight. That’s why I called it “intervals ‘til you puke.” I was often one of the pukers.

The amazing thing back then was that we’d often do this workout five days a week (no one trained on the weekends in the 1960s—at least no one I knew). Somehow, at age 20, I was able to bounce back day after day for this. And on top of that I crammed in late-night college classwork and led a life full of other stuff common to twentysomethings. There was little time for sleep. And yet I would do this workout day after day with no sign of performance loss. Now one such day of intervals ‘til you puke would leave me knackered for several days. There’s no way I could do that again, day after day.

Why not? Well, despite getting little sleep for days at a time I, like all the other young guys (there was no women’s track and field then) on the team, had youth on our side. That largely came down to the endocrine system where anabolic (“tissue-building”) hormones were aplenty. That’s such naturally occurring stuff as erythropoietin (EPO), steroids, human growth hormone, testosterone, and more. I, like the others, had an abundance of such hormones at that young age. But as I got older my hormone production plummeted, as is common in all aging humans. It’s just life.

So why would sleeping more as we get older have an impact on hormones and performance? It’s because that after tearing down tissues with hard workouts, rebuilding by means of such hormones is necessary. And they are most available to the body during slumber. That’s why I usually had to push my clients to sleep more.

Most of them had to change their daily patterns in some way to fit in more bedtime. The first thing that had to go was the alarm clock. For serious athletes having sleep artificially shortened by an alarm is one of the worst things they can do. Awaking should be a natural occurrence, not an artificial one. This meant that the athletes I coached would have to change their lifestyles some how. It wasn’t just going to bed earlier. That’s a given. It meant something in their lives had to go. That had to be their decision, not mine. It might have come down to cutting out late evening TV shows. Or reducing voluntary community responsibilities. Or something else. It’s not an easy decision to make, but it’s necessary especially for the older athlete with high performance goals. The more important the goal, the more important this lifestyle change is.

We have many ways of monitoring and measuring the effectiveness of sleep these days. I’ll touch on a few of those in Part 2 of this topic. Soon—I hope.

November 28, 2017

Sunglasses

Several years ago I was provided training products by a company that eventually let down one of my coaching clients. It reflected badly on me as I had suggested the athlete use their product. When it failed to perform the company refused to stand behind it. I left them and ever since have been very cautious with the businesses I suggest athletes use. That’s why there so few companies I work with closely—only Specialized bikes, D2 Shoe, and ADS Sports Eyewear. They’re all featured on my blog’s home page. I’ve come to trust these companies’ product quality and customer service

ADS has especially been on my mind of late. I recently had my eyes examined as objects in the distance were getting a bit blurry (lesson: avoid growing old). The exam showed that I needed a significant change in my prescription. So after the exam I sent the new prescription, along with my existing frames—both daily wear and sunglasses—to ADS for new lenses. It had been a couple of years since I last used their services.

A lot has changed on the ADS website recently making buying glasses online a lot easier. The site now provides ways to help you select frames based on a pair you currently have that fits you well. There’s a simple measurement you do. Previously there was a lot of guesswork in selecting frames that may or may not fit requiring you to try on lots of them in a store to find what’s right. They now also group the sunglasses by sport and gender. And they are willing to send you sample frames to try on if all else fails.

Lens technology is also changing now making for a wider field of usable vision in wrap-around sunglasses.

ADS provides frames by popular sport sunglass companies such as Adidas, Oakley, Nike, Rudy Project, Under Armour, and lots more.

If you give them a try please let me know what your experience was like by leaving a comment on my blog.

July 21, 2017

Unconventional Thinking

I suppose I'm a bit of a heretic. I seldom accept things at face value just because that's "the way we've always done it" or just because an "expert" says it should be done that way. Or, my favorite, which always starts with, "everybody knows..." I always ask myself why. Why should it be done that way. I've seen these three "reasons" be wrong so many times in my life that I am continually skeptical. You've probably seen the results of my skepticism many times in this blog. It shows up in such topics as nutrition, hydration, periodization, training methods, and lots more. This doesn't mean that everything we've "always done" or that experts have told us to do are always wrong. Not at all. I have often found that there's merit to much of what I’ve questioned. That's a good thing. It means that I can accept the idea and use it with some degree of certainty.

I've sought answers over the years to those things I've questioned by experimenting - first with myself and then with clients. A good example of this is midsole cleats for cycling. This idea was suggested to me in 2005. I thought at first that it sounded ridiculous. After all "we've always" put the cleat under the ball of the foot. “Everybody knows” that's how it should be placed. “Experts” even tell us that. So, with all of this in mind, I set out to prove the midsole cleat position was wrong. I discovered just the opposite: it worked well for me—I climbed and time trialed better and rode more efficiently. So I then tried it with willing clients I coached. For many it also worked better. But not all of them improved as I and others had done. That's not unusual. In my Training Bible books I write about the principle of individualization in sport. The effect of midsole cleats is but one small example of this principle at work.

Besides experimenting I also like to read research to find answers to my questions. The more research I can find on a topic, such as cleat position, the better. The research doesn't always agree. That's ok. It still gives me more information about the topic at hand. For more than 30 years I've started almost every day by reading a research abstract. I keep a stack of them at my desk. If the abstract interests me I seek out the whole study to get a deeper understanding. You can read abstracts for yourself by going to PubMed. Should you be a geek like me you can search out the abstracts for topics that interest you. I suspect there are only a few who would want to do that. But before you assume somebody is wrong because "that's the way it's always been done," or "experts" say we should, or "everybody knows" be sure to do an in-depth review of the research. And try it yourself. You may find, as I have many times, that the alternative method works for you. Or not. That's good. Now you know.

A little skepticism is a good thing. Because of this way of seeing the world I have great respect for others who question what I say. They help to make me a better coach and person.

May 29, 2017

CTL Concerns

The following is a portion of an email I received today from a US serviceman in Afghanistan. He expresses quite well a common concern I hear from athletes in regards to their Chronic Training Load (CTL) on the TrainingPeaks Performance Management Chart (PMC).

++++++++++++++++++++++++++

The email:

Joe,

I’m something of a CTL junkie when it comes to training. If the blue line isn’t going up at 5+ ramp rate/week, then I’m not happy. But lately, I’ve realized that under my current time restrictions (around 10 hours a week of training time), there’s simply no way to maintain that level of increase, and I’ve begun to wonder what’s the point.

I got back into recreational road cycling last year as a way to lose some weight and improve fitness. But I have aspirations of racing when I get home. Last year, my CTL peaked at ~65 (starting at a hard zero), before tapering off when the weather got cold and the days got short. So I essentially re-started from zero again when I got here, and now I’m at around 80. I’m in great shape, about 7% body fat, ~150 lbs, FTP went from 180ish to 233 (@ 6000’ elevation).

So now my question is this: Should I stop worrying so much about what the blue line does, and start doing focused workouts that target FTP, VO2max, etc? Say my CTL hovers at 80 for the next 8 months… does that even matter if I’m able to increase my FTP 50 more watts and add 10% to my VO2max? Or are the two inextricably linked? E.g., my FTP/VO2max won’t actually increase if my CTL stagnates?

Jeff

My reply:

Hi Jeff,

Good questions. It sounds as if cycling race performance is your primary goal. CTL is not an expression of performance but rather a proxy for fitness. Performance and fitness aren’t the same things. You can be quite fit and yet perform poorly. The other way around is unlikely, however. FTP is a better predictor of performance than is CTL. But it’s not perfect either. It doesn’t speak to time trial pacing, sprinting, stamina, or climbing—all important subsets of cycling performance. And that doesn’t include the mental side of the sport. Or strategic and tactical skills. And many other predictors of performance such as heat tolerance and refueling. The only true predictor of race performance is racing. This is not to say that fitness markers are unimportant. But just because CTL plateaus doesn’t mean that race performance can no longer improve.

I like to see a rider’s CTL increase rapidly throughout the base period and then show only small increases during the build period. The purpose of the build period is race readiness. While that includes fitness it also includes all of the above markers that aren’t reflected in the CTL.

The bottom line is that there is no single metric in TrainingPeaks that is the end-all and be-all of race performance. But at the same time, there are metrics there; such as CTL, FTP, EF, VI, TSB, and more; that show you how you’re doing. Performance preparation should not be boiled down to just one of these metrics. There are likely several that are unique to your personal performance weaknesses. I call these your “limiters.” Those should also be measured and frequently monitored to see how you are progressing.

I hope this helps a bit. Thanks for your service to the country and all the best for your training.

Joe

April 10, 2017

Training: Stress, Fatigue, Recovery, Adaptation

A hard workout only creates the potential for fitness. It’s realized when you recover afterwards. When you take it easy after a hard workout the body’s adaptive process kicks in and you become more fit. During recovery the body restores itself by rebuilding damaged cells, creating new neural pathways, expanding capillary beds, rebalancing its chemistry, developing muscles, and much more. During this physiological renovation it makes all of the body’s systems affected by the workout slightly better able handle the stress that produced the need for rest in the first place. This is called overcompensation. The overcompensation process is at the heart of adaptation and therefore race performance. The ultimate result is that the three determiners of your endurance fitness—aerobic capacity, anaerobic/lactate threshold, and economy—improve slightly. The amount of improvement is determined by the type of workout stress applied and how long the recovery lasted.

Recovery and adaptation are essentially the same thing. This adaptive process takes some time and can’t hurried. How much time you need to reduce fatigue and gain fitness depends on how great the preceding workout stress was. If it was only slightly more difficult than what your body was already adapted to then you will probably be ready for another stressful workout again in around 48 hours. A workout that was a great deal harder than your current level of adaptation was capable of handling requires a longer period of recovery.

Following a hard workout you experience fatigue. That is how nature tries to keep you from doing back-to-back hammer sessions that would tear the body down so much it could no longer adapt. An exceptionally high level of fatigue, indicating a very stressful workout, is risky. Combine this with too little recovery time and you’re on the way to overtraining. But the other side of the training coin isn’t much better. Only doing easy workouts day after day or taking several days off results in a loss of fitness. This is the opposite of overcompensation. The key to effective training is to strike a balance between these two determiners of high-performance—stress and recovery—so that fatigue is created and then reduced.

So there is no improvement in fitness without at least some fatigue. How much fatigue is necessary for this? Unfortunately, that’s hard to nail down because fatigue isn’t as easily measured as fitness, at least not yet. Precise tests, such as those used in measuring VO2max or anaerobic threshold, don’t exist for fatigue. That makes recovery an art more than a science. While there are some ways of determining it, fatigue requires a lot of guesswork in order to come up with the proper recovery dose for the given stress load that produced it. This means recovery from fatigue is mostly based on self-perception and sensations. But we’re slowly getting better at measuring it. Sport science generally comes up with something every few years for gauging what the body is experiencing following a hard workout or period of training. One such tool is heart rate variability. Such breakthroughs allow us to make better-educated guesses at how much recovery may be needed following a given workout. Even with such measurement, however, it’s still imprecise.

What further confounds all of this is that recovery is highly individualized. Not all recovery methods work equally well for all athletes following the same types of training sessions with similar levels of fatigue. The challenge is to figure out what works for you. The two most common and most effective are sleep and nutrition. But there are other options such as compression garments, pneumatic compression devices, massage, alternating hot-cold water emersion, and many more. There could be several things to try before finding the best for you. Even then their effectiveness may vary from one workout to the next. The solutions may be found by simply trying things. This isn’t easy because there are quite a few and some involve using special and somewhat expensive gear. They are also quite individualized. But you probably already have a great deal of experience with some of the methods. Most advanced athletes soon figure out these things as their racing careers progress.

Here’s one example of the individuality of recovery. Most advanced athletes find that an easy session—called “active recovery”—stimulates recovery and therefore contributes to adaptation whereas most novice athletes and many intermediates (second and third years in their sports) find that a day off from training—“passive recovery”—is usually the better option.

Connecting the dots for all of this leads to the conclusion that fatigue is good because it implies the potential for fitness, and that decreasing fatigue is an indicator of adaptation and therefore realized fitness. That’s a big deal. So the overarching lesson here is that recovery is just as critical to your success in sport as are hard workouts. If you are good at doing one but not the other you will fall well short of your potential. It takes both the stress of training and the adaptive process of recovery to be race ready.

March 21, 2017

Time, Family, and Training

I just got a DM from a guy who is experiencing what it’s like to try to train and race at the same time the family and career responsibilities are increasing. Here was my response:

I can relate, Jim. Lots of athletes ask about things related to this topic. (I once had a guy tell me he had been sentenced to a 30-year mortgage and 3 kids. Seems a bit harsh but that was how he saw his life.)

When my son had his first child in his 30s I told him he was now coming into the hardest time of life for a male (it's certainly not easy for females at this stage of life either, but in a different way, usually). You are expected to be a good father - and yet you are also expected to grow your career in order to support your family. No matter which you spend more time and energy on you're wrong. I went through that myself many years ago.

From a sport perspective I think the key is goal setting. The goals must be easily within the boundaries of what you could accomplish before the family got larger. Then, assuming you don't have much time, intensity becomes the key to accomplishing those goals. So it's best to have goals that are for shorter, high-intensity races. And probably not too many of them in a season. Other than that it requires a lot of patience.

It will be a long road. But a fun time in many ways that you’ll look back on later in life with a sense of accomplishment. The bottom line is that it will get easier as the kids grow up and your career rounds into shape. Good luck!

February 12, 2017

My Email to a 16 Year-Old S African Rider

Thanks for your email. I’m glad to hear that you have high goals for the sport and dreams of becoming a pro. Dreams at your age are always the starting place for anyone who eventually becomes a pro. Otherwise, there are many differences in the backgrounds of the pros. But not when it comes to their dreams. There are a few other things they mostly had in common as juniors. Most had coaches. That is the best way, without a doubt, to pursue your dream. Someone who knows the sport and can meet with you occasionally and even ride with you. You didn’t say if you had a team to train and race with. That’s another thing that was common for most of the pros when they were younger. A team can provide much of the support you need in achieving your dream.

You mentioned occasionally missing workouts. It’s ok to have times when you don’t train. In fact, it’s probably healthy for you. But ultimately the key to success is consistent training. Missing workouts frequently is counterproductive and will lead to lackluster performance. But well-timed breaks from training are to be expected and good.

The bottom line for achieving your dream is a good coach and a supportive team. I hope you are seeking both of these. And, in fact, they may be overlapping. If you have a team you are also likely to have a coach.

I’d also suggest reading the biographies of pros from the last 40 years or so to see how they progressed as juniors and what worked for them in becoming pros. There are several such books out there on Merckx, Fignon, Lemond, Froome, Wiggins, and more. These will help with motivation while also offering suggestions on paths to take.

All the best for your success. Please let me know how I can be of help.

Joe Friel

January 15, 2017

Max Heart Rate and Performance

I received a couple of interesting questions about max heart rate (HRmax) this week...

Question: Does declining max HR with age affect max performance?

First, there is no research I’m aware of on exactly this topic as it relates to aging. So this is my opinion only. Something related we do have research on has to do with short-term changes in HRmax due to performance changes (Zavorsky 2000). This is, in a way, a reverse of your question. We know, for example, that as VO2max (aerobic capacity) increases HRmax decreases—as much as 7% according to some research. The more aerobically fit you become the lower your HRmax becomes. And the other side of the same coin is that as aerobic fitness declines HRmax increases. In other words, it is not a foregone conclusion that a decrease in HRmax means a decline in performance. That’s a very common but unsupported view of athletes who are ill informed about the science behind heart rate. They assume a high HR means a high level of performance. Not true. For example, I once coached a cyclist in his 60s with a HRmax in the upper 140s. He broke the US record for the 40km time trial despite his relatively low HR.

But your question has to do with declines in performance related to changes in HRmax. First of all, we don’t know why HRmax changes with age. It appears to, but those studies were done almost entirely using aerobically untrained subjects. Not only had their HRmax changed but they also experienced many other changes with aging such as a loss of muscle mass. And since all the heart does during exercise is respond to the demands of the muscles (for O2 and fuel, primarily), if there's a loss of muscle power the demand will be low so the HRmax will also be low. Maybe. Again, no research.

So does performance decline with age? Definitely. Exactly why that happens is open to conjecture. One of the most common explanations is a loss of VO2max power as a result of the heart’s stroke volume (blood pumped per beat) declining. Why does that happen? We don’t know for sure. Perhaps, among the many possibilities, it has to do with a change in lifestyle as we age. As a young person the athlete may have done highly intense training. But as he/she ages there is often a shift toward long, slow distance exercise with less intense training. We know that such a shift causes a reduction in stroke volume (along with decreased muscle mass—the demand thing again). So the physiological process of aging may not be the culprit at all. It may simply be lifestyle.

My guess is that HRmax has nothing to do with performance. Unfortunately, that thought is totally rejected by athletes who see their heart rates as the end-all and be-all of training. That’s all they know how to measure (“for a hammer the whole world is a nail”). So it’s not a popular position to take if you want to win support for a different way of training—such as power- or pace-based training or something else.

Question: What considerations should a woman in her 50s, for example, have regarding the Fitbit training zones (which are based on set percentages of a 220-Age Max), compared to someone in her 30s (recognizing that the formula may be off due to individual differences, are there age-related differences as well?)

That's correct about such formulas. Research has shown the 220-age formula may be off by +11 to -11 (Robergs 2002), which makes the formula pretty much unusable. A 22-beat per minute range is gigantic. Personally, mine is off by about 33bpm. A guess would be at least as accurate—probably more so.

I believe it’s far better to base zones on anaerobic/lactate threshold HR as it is much more easily determined and less dangerous to discover. It also reflects more about one’s fitness (Faude 2009) than does HRmax. How fast or powerful one is at a sustained threshold HR speaks volumes about the person’s fitness. The gap between threshold and HRmax also indicates a great deal about aerobic fitness. If you and I have the same HRmax but you achieve threshold (go anaerobic) at 85% of HRmax and I do that at 65%, you are much more aerobically fit. I’ll be suffering at 75% while you are just cruising along. That's why I believe threshold is a better metric for setting zones than is HRmax.

Additionally, a true HRmax requires the motivation accompanying a gun to the head. Most people, including athletes, are unable to push themselves hard enough to see a true HRmax. It’s much too painful. They get a moderately high number after a few minutes of suffering and assume that’s it. They’re nearly always wrong as this commonly results in a much lower number than they are physiologically capable of producing under the right circumstances such as a short, all-out race or perhaps a clinical test. And not only that but it’s also dangerous to suggest to untrained people who aspire to set up HR zones that they exercise to a maximal HR. I would never suggest that.

Finally, there is absolutely no reason to compare HR zones. It tells us nothing about either person as far as fitness, health, or performance is concerned. It’s like comparing shoes sizes to determine how fit people are. There is little in the way of an absolute and direct relationship between the two.

January 1, 2017

How Important Is Training Volume?

Last week I received an email from an athlete who was concerned about her training for the coming year. She had wisely decided that she needed to include a rest and recovery week every third week. But she was concerned that this would reduce her volume and therefore her race performance. That caused me to look back in my blog archives to see if I had a post on this topic. I did. That blog was originally posted December 9, 2007. While that’s a long time ago, very little has changed.

But back to the email…

Her concern about decreasing volume set off a couple of alarms in my head. There’s no question that taking one’s training volume very low will have a negative effect on race readiness. (Volume is the combination of workout duration and workout frequency.) If an athlete has been training with a volume of 10 hours per week, cutting that to 5 would certainly have negative consequences. Given unique physiologies and lifestyles, every athlete has a sweetspot when it comes to weekly hours or miles or kilometers. I have no way of knowing what that may be for the athlete who contacted me.

Here’s the first alarm: I’m not convinced that by reducing volume every third week that the reduction would significantly impact her race performance. I’d suggest that it may actually help performance when compared with no R&R in order to keep volume high.

It’s also important to mention here that an R&R “week” doesn’t mean it has to be 7 days long. In fact, it may only be 3 to 5 days of reduced training load as 7 are seldom necessary, I’ve found. When you honestly feel like the fatigue is gone following a break from the normal training routine it’s time to start back at it again. If the fatigue is only slight coming into the R&R week and, especially, if you normally recover quite quickly, then 3 days is probably adequate. On the other hand, if you’re really tired or if you tend to recover slowly then 5 days is likely to do the trick. With a day or two of testing following the R&R break you should be ready to get back to serious training.

Another alarm had to do with her emphasis on volume—with no apparent concern for intensity. Intensity wasn’t even mentioned despite the fact that reducing her training load in a R&R week also would reduce intensity. Nope, volume was her only concern. That’s quite typical. It’s rare to find an athlete, even a highly experienced one, who doesn’t also share that same worldview about the volume-intensity relationship when it comes to endurance training. They tend to believe that volume is the key to performance, in fact, the most important key. Why is that? There are a couple of reasons for this, I think.

First, in the early years of an athlete’s training it soon becomes apparent that increasing volume improves performance. There’s no doubt that it does, especially at that stage of experience. That mindset stays with the athlete for years.

Second, volume is easy to measure and talk about. Intensity doesn’t easily lend itself to weekly, cumulative measurement. Volume does. That doesn’t make volume more effective for race preparation, however. There are many research studies showing that intensity is at least as critical for race preparation as volume, and most found intensity is more important. You can find a list of such studies below (if you go to PubMed, copy and paste one of the references from below into the search function, you can read the abstract for yourself).

A good example of this high emphasis on volume in training takes me back to a runner I coached many years ago. If I scheduled a 45-minute run on mountain trails and she got back to her car in 42 minutes she’d run laps around it for 3 minutes. That’s a quite common mindset. Most athletes see workout duration, and therefore volume, as the golden chalice. It must be achieved at all costs.

So that’s what I think about volume. But what about intensity? For the purpose of this discussion I’m taking high-intensity training to mean doing workouts at race intensity or higher. If your race will take an hour or less then the average intensity will be quite high—probably near your anaerobic threshold. As the race gets longer the average intensity decreases. Road cycling, however, presents a slight contradiction to this rule. While the average intensity may not be higher than what would be common for a steadily paced event such as a running race, the bike race will typically have many brief episodes with extremely high peak intensities. Training for such a race means you must focus on these peak intensities. The race outcome will be determined by them.

The longer your event is the more likely I believe you’ll benefit, at least in the long term, from doing workouts near and above your anaerobic threshold. So, for example, if I were training a triathlete for an Ironman, even if it would take 12 or more hours to finish, I’d have them do a bit of anaerobic threshold interval training throughout the seasonal preparation. Because of this they would not only produce better results than if they only trained slowly, their fitness (VO2max, threshold, and economy) would be easier to maintain at high levels for several years to come. Otherwise, I would expect to see these physiological markers of fitness decline rather rapidly with age. (There was a nice study a few years ago on this topic that compared the race fitness of otherwise similar triathletes who focused on training for either Ironman- or Olympic-distance races, but I can’t seem to find it. If familiar with this please send it my way. Thanks.)

Also, the more your available time for training is constrained by career, family or other factors, the more important high-intensity training becomes. If you’re short on time, doing intervals will bring better results in the long term than doing short but relatively slow workouts. It just comes down to how often you do the short but hard sessions.

So how relatively important are volume and intensity for the advanced athlete (“advanced” meaning more than 3 years in the sport)? I’d suggest that on race day 60% of the athlete’s race readiness is determined by the intensity of their training. The remaining 40% is a result of volume. If volume was high but intensity was neglected then I wouldn’t expect a good race performance. However, if volume was low but intensity high I’d expect a better race performance. I’d rather err on the side of too little volume than too little intensity.

I should also point out here that when I'm promoting intensity as the more critical of the two variables when it comes to race performance, that doesn't mean that all of your workout intensities should be pushing your limits. There are times for high intensity and there are times for low intensity. That blend is entirely determined by your unique capacity for training.

So what’s the bottom line here? I’d suggest you do as much volume as possible so long as it doesn’t interfere with your readiness to do high-intensity workouts. If a regularly scheduled long workout or an emphasis on successive moderately long workouts leaves you too tired to do a subsequent high-intensity workout then I’d suggest cutting back on the long duration or the weekly volume and allowing for more recovery between sessions. This also includes frequent R&R weeks. Whatever you do, don’t place so much emphasis on volume that you are too tired to do intense training. That’s counterproductive.

I might also suggest here that the ultimate solution may be found in thinking about your training in terms of Training Stress Score—the combination of duration and intensity into a single number. It will change your training mindset for the better.

References

Costill, D.L., et al. 1991. Adaptations to swimming training: Influence of training volume. Med Sci Sports Exerc 23:371-377.

Gomes, P.S. and Y. Bhambhaniy. 1996. Time course changes and dissociation in VO2max at maximum and submaximum exercise levels as a result of training in males. Med Sci Sports Exerc 28(5):S81.

Fry, R.W., et al. 1992. Periodisation of training stress–a review. Can J Sport Sci 17:234-240.

Laursen, P.B. and D.G. Jenkins. 2002. The scientific basis for high-intensity interval training: Optimizing training programmes and maximising performance in highly training endurance athletes. Sports Med 32(1):53-73.

Lehmann, M., et al. 1996. Unaccustomed high-mileage vs intensity training-related changes in performance and serum amino acid levels. Int J Sports Med 17(3):187-192.

Midgley, A.W., et al. 2006. Is there an optimal training intensity for enhancing the maximal oxygen uptake of distance runners?: Empirical research findings, current opinions, physiological rationale and practical recommendations. Sports Med 36(2):117-132.

Mujika, I., et al. 1995. Effects of training on performance in competitive swimming. Can J Appl Physiol 20(4):395-406.

Seiler, S., et al. 2009. Intervals, thresholds, and long slow distance: The role of intensity and duration in endurance training. Sportsci 13:32-53.

Joe Friel's Blog

- Joe Friel's profile

- 91 followers