Joe Friel's Blog, page 10

September 24, 2013

Aging: Is It Just a Number in Your Head?

People such as Diana Nyad who recently swam

from Cuba to Florida at age 64 change the standards of what it means to be “old.”

There are hundreds of aging athletes who have made great sports achievements

but most of us never hear of - such as Bob Scott.

At age 75 racing Ironman Hawaii Bob set a new course record

for his age group of 13:27:50. Winning and breaking triathlon records is

nothing new for him. He also set the men’s 70-74 age group record four years

earlier with a 12:59:02 finishing more than 90 minutes ahead of the second age

group finisher.

Or how about Libby James, age 76, of

Fort Collins, Colorado who set a new half marathon world record of 1:45:56 for

her 75-79 age group this year. She easily demolished the previous record of

1:55:19. Few women half her age can run such a time. Such a list of amazing

accomplishments from aging athletes could go on and on.

Most of what we think we know about aging

didn’t come from people such as Diana, Bob and Libby, but rather from aging,

sedentary folks watching TV in their La-Z-Boy recliners. As a result much of

the research on what the future holds is meaningless for those of us who

continue to push the limits of performance as we grey. The oldest athletes from

the Baby Boomer generation are now in their mid- to late 60s and have been redefining

what “old” means for almost 20 years. How can we explain their rather sudden changes

in aging performance?

As

I attempted to describe in my last post here, the aging process appears to

be part biology and part lifestyle. No one knows exactly what the mix is –

which has the greater impact. The trend in research currently appears to be

that lifestyle has the greater affect. Leyk and associates at the German Sport

University in Cologne summed it up: aging is a “biological process than can be

considerably speeded up or slowed down by multiple lifestyle-related factors.”

Every recent research study I’ve read on aging agrees that biology and

lifestyle do indeed determine the effects of aging. But is it 30-70, 50-50, 70-30 or some other mix? That’s currently unknown and undoubtedly depends on who

we are talking about. How we age biologically and how we choose to live are

highly individual matters with training playing an important role on the

lifestyle side of the equation for athletes.

To

find such answers it is sometimes best to study athletes from the highest

levels of performance to know what is possible. Let’s take a look at one such longitudinal

study.

Starting

in the 1970s, 21 male, elite masters runners were tested three times over 20

years for various physiological markers including maximum heart rate, body

weight, bone density and aerobic capacity (Pollock). When first tested the

average age was 50. The follow-ups were done at about ages 60 and 70. By around

70 each formerly elite athlete was categorized into one of three general groups

– 9 who continued to train and race at a high duration, volume and intensity and

remained elite age groupers, 10 who continued frequent but moderately rigorous

endurance training and 2 who greatly reduced training to a low level.

What they found was that, compared with age 50, 1) all lost 10 to 14 bpm

of max heart rate, 2) the two more active groups maintained their age-50 body

weights but the low-level group gained 2 to 2.5% additional fat, 3) those who

lifted weights had greater bone density and 4) all, including the most active

groups, lost 8 to 15% of their aerobic capacities with the most active

experiencing the smallest decline. Of course, the number of subject here is

quite small, but the results are pretty similar across most of the research

I’ve read.

So

what can you do to maintain or even improve fitness and performance? What

drives the physiology of training for high performance when you are old is no different than what it was

when you were 40 years younger. The principles of training don’t change. What

changes is our capacity – physical and psychological – to handle the stresses

associated with focused and serious workouts. In the next post I’ll offer my

suggestions for what aging athletes can do to maintain or even improve

endurance performance.

References

Leyk D, Erley O, Gorges W, et al. 2009.

Performance, training and lifestyle parameters of marathon runners aged 20-80

years: results of the PACE-study. Int J

Sports Med 30(5):360-5.

Pollock ML, Mengelkoch LJ, Graves JE,

et al. 1997. Twenty-year follow-up of aerobic power and

body composition of older track athletes. J Appl Physiol 82(5):1508-16.

September 22, 2013

Aging: What's Behind the Decline?

There’s

no doubt that there is a loss

of athletic performance with aging. We will never see a

70-year-old athlete take gold in the Olympic Games marathon. Sports scientists

have offered several

reasons why age robs us of the ability to compete with young endurance

athletes at the highest level. In my last post I described a couple of studies

examining the loss of muscle mass as this is one of the commonly accepted

reasons for slowing down as we get older.

What’s

not fully understood is why muscles atrophy. We know that muscle fibers get

smaller and even seem to disappear later in life. It has to do with some

combination of the well-documented physiology of aging and the less understood changes

that typically occur in lifestyle resulting in our being less active as we get

older. How much of the loss of performance can be attributed to these two

variables – physiology and lifestyle – is open to speculation. Which causes the

greater drop in performance over the years? The research I described here on muscle and aging still

leaves the question unanswered.

But

many scientists have come to conclusion that the major contributor to the

decline is not really age, but rather lifestyle, especially a reduction in

strenuous activity. They believe the physiology-lifestyle balance is around

30-70. In other words, 70% of our lowered performance may be explained by

changes in lifestyle (training) with the changes due to aging accounting for

only 30%.

Besides

muscle wasting, there are other physical changes that science tells us to

expect as we get older. Perhaps we can find an answer as to what the balance is

between physiology and lifestyle as the root causes in one of them.

One other such critical marker of aging is aerobic capacity (VO2max). This is one of the most

studied markers of endurance performance. Perhaps we’ll find the answer here.

But

before getting into that, let’s review the big picture of what accounts for our

performance in endurance sports. Science tells us there are three physiological

predictors of your endurance performance regardless of age:

�* Aerobic capacity has to do with how much

oxygen you use per minute relative to your body weight when at a sustained, maximal workload. This intensity can be maintained for only a handful of minutes by

highly fit athletes. The greater the aerobic capacity, the greater the

likelihood you can produce a high level of performance.

�* Lactate threshold is the percentage of aerobic

capacity at which you begin to “redline” meaning that you start to experience

an increase in the acidity of muscles and body fluids. Highly fit athletes can

maintain this intensity for about an hour.

�* Economy measures how efficiently you

use oxygen to produce a given output (pace, speed, power). The greater the

economy, the less wasted oxygen (and energy) and therefore the better your

performance.

Of

these three, science tells us that the best marker of age-related performance

decline is aerobic capacity and secondarily lactate threshold while economy is

a distant third and seems to remain stable (Tanaka, Tanaka, Wiswell). That

economy would not be a good age-related performance predictor makes sense since

after decades of training and racing the movement patterns of older athletes

have become well-honed. So it’s aerobic capacity that we need to examine

closely to see what might be expected as the candles on the birthday cake

increase.

Aerobic

capacity is largely dependent on how much oxygen-carrying blood your

cardiovascular system can deliver to the muscles. So the starting point is your

heart’s stroke volume (how much blood is pumped per beat). Among the many other

aerobic capacity determiners are aerobic enzymes found in the muscles. Both of

these and a bunch of other aerobic capacity determiners – such as how elastic your

blood vessels are and how much red blood cell-building, natural levels of EPO

you produce – have been shown to decline with age.

Ok,

so aerobic capacity decreases as we get older. I can accept that. But by how

much, and more importantly, why? Let’s go back to the research to look for

answers.

There

is quite a bit of research on age and aerobic capacity. How come? I suppose it’s

because aerobic capacity is so easily measured in the lab (it’s been a common

procedure since the 1920s) and it doesn’t require invasive techniques such as taking

muscle biopsies or pricking the skin to draw blood (ouch!).

Since

VO2max testing has been so common for so long we now finally have some

longitudinal studies in which athletes are tested over several years to see how

their aerobic capacities change. This offers hope of finding the affect of

lifestyle on performance as distinct from the aging process. Let’s look at a

few such studies.

Research tells us that the decline has a lot to do with how active we are as we

get older. For example, a paper released in 2000 examined the combined affects

of age and activity level over time (Wilson). The researchers reviewed 242

studies on aging and VO2max involving 13,828 male subjects. Each of the

subjects was assigned to one of three groups based on how active they were:

sedentary, moderately active exercisers and endurance-trained runners. Aerobic

capacity was highest in the runners and lowest in the sedentary. No surprises

there. The aerobic capacity changes per decade of life were sedentary -8.7%, active

-7.3% and runners -6.8%. So if at age 30 a man had a VO2max of 60 and for the

next 30 years didn’t exercise and lived a “normal” life (sedentary) he could expect

his aerobic capacity at age 60 to be around 46. If moderately active it would

be about 48. And if he trained it would be in the neighborhood of 49. Those are

not significant changes.

But

the study further reports that the subjects who were “endurance-trained runners”

significantly decreased their volume (miles/kilometers run per week) and training

intensity as they got older. I’ve found that as a common practice with aging

athletes. There could be many reasons for this (which I’ll address in the

following post). So maybe it’s not simply working out that maintains aerobic

capacity and therefore, in part, race performances, but rather how much

training you do and how intensely you do it. This is an important lesson

That

aerobic capacity declines with aging and reduced training is not surprising.

I’ve mentioned “use it or lose it” several times in this on-going discussion. This

brings us back to the question of what the balance between age and lifestyle is

when it comes to performance.

Three

other reviews of the literature in the last decade or so examined the

relationship between aging and training status to figure out the relative

contributions of both (Hawkins, Wiswell, Young). They confirm that reductions

in training volume and intensity are primary contributors to the loss of

aerobic capacity with advancing age.

Let’s

dig a little deeper to find which is more important to the maintenance of

aerobic capacity with aging from a strictly training perspective – volume or

intensity. The answer may provide some insights into how to train as age sneaks

up on you – assuming you want to maintain, or at least slow, the drop in

performance which probably first becomes apparent in your 50s and greatly

accelerates somewhere beyond 70.

In

the 1970s a team of researchers at the University of Illinois measured the

aerobic capacities of 24 masters track runners who were 40 to 72 years old at

the time (Pollock). Ten years later they were retested. Over the decade all

continued to train but only 11 were still highly competitive. The other 13 quit

racing and decreased their training intensity. The competitive athletes

maintained their training intensities and, consequently, their aerobic

capacities. There was no significant change. The non-competitive, low-intensity

group lost about 12% of their aerobic capacities over 10 years.

So what’s the bottom line here? The research team led by Wilson showed

us that the changes in aerobic capacity with aging are not too different

between sedentary subjects and runners who

reduce their training. Several other studies also showed us that decreases

in training workload have a significant impact on aerobic capacity with the key

being intensity, according to the Pollock paper. When training intensity was

maintained by master runners over a 10-year period, aerobic capacity remained

unchanged. When training volume remained about the same but intensity

decreased, aerobic capacity dropped by an average of 1% per year.

That’s a clear message. It isn’t just exercising slowly for long periods

of time that keeps our performance, at least in terms of aerobic capacity, from

dropping rapidly; it’s primarily the intensity of the exercise that matters.

That raises new issues (problems?) that I’ll address in my next post.

References

Hawkins S, Wiswell R. 2003. Rate and mechanism of maximal oxygen consumption decline with aging:

implications for exercise training. Sports Med 33(12):877-88.

Pollock ML, Foster C, Knapp D, et al. 1987. Effect of age and training on aerobic capacity and body composition of

master athletes. J Appl Physiol 62(2):725-31.

Tanaka H, Seals DR. 2003. Invited review: Dynamic

exercise performance in masters athletes: insight into the effects of primary

human aging on physiological functional capacity. J Appl Physiol 95(5):2152-62.

Tanaka H, Seals DR. 2008. Endurance exercise

performance in masters athletes: age-associated changes and underlying

physiological mechanisms. J Physiol

586(1):55-63.

Wilson TM, Tanaka H. 2000. Meta-analysis of the

age-associated decline in maximal aerobic capacity in men: relation to training

status. Am J Physiol Heart Cric Physiol 278(3):H829-34.

Wiswell RA, Jaque V, Marcell TJ, et al. 2000. Maximal aerobic power,

lactate threshold, and running performance in master athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32:1165-70.

Young BW, Medic N, Weir PL, Starkes JL.

2008. Explaining performance in elite middle-aged

runners: contributions from age and from ongoing and past training factors. J Sport Exerc

Psychol 30(6):737-54.

September 18, 2013

Aging: What’s Happening to My Muscles?

Scientists who study aging have been telling us for years that we can

expect a loss of muscle mass as we get older. We’re simply destined to lose muscle

fibers, especially type II fibers – the fast twitch ones (Deschenes, Iannuzzi-Sucich,

Karakelides, Proctor, Short,

Wilkes). We are told to expect about a 40% to 50% loss by age 80 (Doherty, Faulkner,

Karakelides, Lemmer). Depressing for someone of my advanced age (69).

Several more recent studies, however, are now concluding that the

changes with aging reported in such research are largely the result of disuse

and not as much due to the ravages of age as previously believed (AAgaard, Maharam,

Melov). How is it that science is finally coming to this conclusion? By

measuring what’s happening with older masters athletes who continue to compete

and comparing them with young athletes and with the oldsters’ sedentary age

peers.

For example, Wroblewski compared athletes aged 40 to 81 in a cross-sectional

study and found that although body fat increased with age, quadriceps muscle

mass and strength were similar across all ages. All of the subjects, regardless

of age, trained four or five times weekly as runners, swimmers, cyclists or

triathletes. Use it or lose it. Right?

Of course, the confounding element in cross-sectional studies such as this is that the

older athletes may have self-selected. In other words, perhaps they didn’t

maintain their muscle mass because they were athletes, but rather they were

athletes because they maintained their muscle mass. Those who couldn’t maintain

muscle mass with age may have quit their sport or never even started such

strenuous activities. So the research still leaves us wondering.

It could be inevitable that you will eventually lose some muscle, but it

may be insignificant for decades if the more recent research is to be accepted

at face value. The most common reason given for this happening is a decrease in

the body’s production of anabolic (muscle- and tissue-building) hormones such

as testosterone, estrogen, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor. But

then exercise is anabolic also – it may help us hold onto muscle as we get

older by slowing the demise of these hormones (Arazi, Kraemer, Cadore).

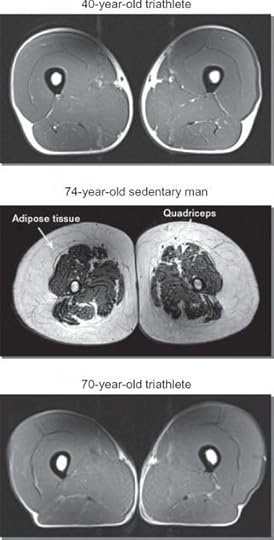

The accompanying pictures of the cross-sectional areas of three people of

different ages illustrate this belief (Wroblewski). These MRIs compare the

thigh muscles of two male triathletes at ages 40 and 70 with those of a

sedentary 74-year-old male. Note the atrophied muscles and surrounding fat on

the thighs of the sedentary man and how similar the muscle mass of the two

triathletes are regardless of age. Is this what we can expect? These pictures

made the rounds on the internet about a year ago and lend support to the idea

that remaining active through strenuous

exercise may well be the best thing you can do to hang on to your muscle mass

as you age.

One of the authors of this study believes that aging accounts for only

about 30% of the decline in athletes (Wright), whereas most cross-sectional

studies of sedentary older people place 50% to 70% – or more – of the blame on

age alone. Could exercise keep your muscles young?

A couple of recent, unique studies from the University of Western

Ontario lend support to the “use it or lose it” concept (Power, Power). The

researchers counted the number of motor units in both young and old subjects. A

motor unit is a group of muscle fibers activated by a single nerve in the

spine. With aging (or is it disuse?) those nerves die and their associated

muscle fibers atrophy. And so we lose muscle size, strength and power. This has

been known for quite a long time with aging rats. But how about with people? The

initial Power’s study done in 2010 was the first to examine this phenomenon in

humans.

Basically, the researchers found that we’re quite similar to rats in

this respect. Runners in their 60s had about the same number of motor units in

their tibialis anterior (a shin muscle) as runners in their 20s. But when they

counted the motor units in sedentary but healthy people also in their 60s the

scientists discovered the inactive older folks had 35% fewer motor units than

the same-age runners. Essentially, the old runners had young leg muscles.

The Canadian researchers logically wondered if this finding meant that

all the muscle motor units in an aging runner’s body were maintained, or just

the running-related motor units? So in a similar follow-up study they counted motor

units in the biceps brachii (upper arm) of aging runners, young runners and

aging sedentary. They found that the older runners had about 48% fewer motor

units than the young runners and about the same as the older sedentary.

Apparently, exercise does not maintain muscles unless they are strenuously

trained. So there is now little doubt – use it or lose it. Right?

But, again, could this result could be the consequence of who the

subjects were? After all, it was a cross-sectional study. The subjects may have

self-selected. People who maintained their motor units may have continued to

compete into old age while those who didn’t maintain them dropped out of sport at a much younger age.

I wish we could take a look at some longitudinal studies of aging to see if these

results hold true when athletes are followed for several years. Unfortunately,

such research is lacking.

So it still comes down to opinion. Mine is that the existing research is

probably accurate and that while aging has some affect on muscles mass, the

greater cause of the decline is more than likely lack of use – an increasingly

sedentary lifestyle as we get older. I see this even in master athletes. The

older they become, the less strenuous their training.

In the next post I’ll take a look at sport science’s somewhat depressing view of aerobic

capacity (VO2max) and aging. Then we’ll move on to what I think the solutions

may be for maintaining (or even improving) muscle mass, VO2max and performance as we get older. I know

some won’t like my conclusions. Everyone is entitled to an opinion when we

have little in the way of data.

References

AAgaard P, Svetta C, Caserotti P, et al. 2010. Role

of the nervous system in sarcopenia and muscle atrophy with aging: strength

training as a countermeasure. Scand J Med

Sci Sports 20(1):49-64.

Arazi H, Damirchi A, Asadi

A. 2013. Age-related hormonal adaptations, muscle circumference and strength

development with 8 weeks moderate intensity resistance training. Ann

Endocrinol (Paris) 74(1):30-5.

Cadore EL, Lhullier FL, Brentano MA, et al. 2008. Hormonal responses to resistance exercise in

long-term trained and untrained middle-aged men. J Strength Cond Res 22(5):1617-24.

Deschenes MR. 2004. Effects of aging on muscle fibre type and size. Sports Med

34(12):809-24.

Doherty TJ. 2003. Invited review: aging and sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol 95(4):1717-27.

Faulkner JA, Davis CC, Mendias CL, Brooks SV. 2008. The aging of elite

male athletes: age-related changes in performance and skeletal muscle structure

and function. Clin J Sport Med

18(6):501-7.

Greenlund LJ, Nair KS. 2003. Sarcopenia--consequences, mechanisms, and potential therapies. Mech Ageing Dev 124(3):287-99.

Iannuzzi-Sucich M, Prestwood KM, Kenny AM. 2002. Prevalence of sarcopenia and predictors of skeletal muscle mass in

healthy, older men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 57(12):M772-7.

Karakelides H, Nair KS. 2005. Sarcopenia of

aging and its metabolic impact. Curr

Top Dev Biol 68:123-48.

Kraemer WJ, Hakkinen

K, Newton RU, et al. 1999. Effects

of heavy-resistance training on hormonal response patterns in younger vs. older

men. J

Appl Physiol 87(3):982-92.

Lemmer JT, Hurlburt DE, Martel TBL, et al. 2003. Age and gender

responses to strength training and detraining. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32:1505-12.

Maharam LG, Bauman PA, Kalman D, et al. 1999. Masters athletes: Factors

affecting performance. Sports Med

28(4):273-85.

Melov S, Tarnopolsky MA, Beckman K, et al. 2007. Resistance exercise

reveres aging in human skeletal muscle. PLOS

One 2(5):e465.

Power GA, Dalton BH, Behm DG, et al. 2010. Motor unit number estimates

in masters runners: Use it or lose it? Med

Sci Sports Exerc 42(9):1644-50.

Power GA, Dalton BH, Behm DG, et al. 2012. Motor unit number survival in

lifelong runners is muscle dependent. Med

Sci Sports Exerc 44(7):1235-42.

Proctor DN, Balagopal P, Nair KS. 1998. Age-related sarcopenia in humans is associated with reduced synthetic

rates of specific muscle proteins. J Nutr 128(2 Suppl):351S-355S.

Short KR, Nair KS. 1999. Mechanisms

of sarcopenia of aging. J Endocrinol Invest 22(5 Suppl):95-105.

Wilkes EA, Selby AL, Atherton PJ, et al. 2009. Blunting of insulin

inhibition of proteolysis in legs of older subjects may contribute to

age-related sarcopenia. Am J Clin Nutr

90(5):1343-50.

Wright VJ. 2012. Masterful care of the aging triathlete. Sports Med Arthrosc 20(4):231-6.

Wroblewski AP, Amati F, Smiley MA, et al. 2011. Chronic exercise

preserves lean muscle mass in masters athletes. Phys Sports Med 39(3):172-78.

September 16, 2013

Aging: More on Science

The

traditional advice from the medical community is that older people (usually

meaning age 50 and up) should avoid strenuous exercise. Instead, once we reach

that doddering age, we should walk – not too fast, mind you – work in the

garden and, at most, square dance on occasion or participate in water aerobics

classes.

I

suspect that since you are reading blog that you don’t listen to such advice.

Your parents may have, but not you.

If

you’re on the AARP mailing list then you are helping to redefine the

expectations of aging by training and competing at a high level. Fifty-plus Boomers,

as a whole, are more active and fit than their parents were at age 20. Why the

change? That’s way beyond the scope of this post, but I suspect it has

something to do, in part, with people such as Kenneth Cooper, David Costill, Frank

Shorter, Albert Salazar, Mark Spitz, Julie Moss, Dave Scott, Mark Allen, Greg

Lemond, Gary Fisher, Jacquie Phelan and other endurance-sport trend setters and

athletes from the late 1960s through the early 1980s. The rise in popularity,

at least in the US, of fitness, running, swimming, triathlon, road cycling and

mountain biking can be traced to such people. The change didn’t come from

science.

Sport

science has a poor record when it comes to leadership. It almost always lags

behind the most obvious changes that happen in sport. For example, sport

science didn’t come up with the Fosbury Flop high jump technique, but later on

explained why it was so much more effective than the previous eastern and

western roll methods (the jumper’s center of gravity passes under the bar

rather than over it). Now all high jumpers do the Flop. Sport science didn’t

invent the bicycle aerobars. That was the brainchild of a Montana ski coach by

the name of Boone Lennon. Sport science later reported on why they worked so

well (they greatly reduced drag caused by the body which is the greatest

impediment to going fast on a bike). I’ll bet you have some in your garage and

wouldn’t think of doing a time trial or triathlon without them. And the list of

things sport science learned about after the fact could go on and on. It’s rare

when science leads the way on anything.

There

are rare exceptions. Training periodization came from sport scientists in the

Eastern Bloc countries in the early 20th century based on the work

of scientists such as Tudor Bompa, PhD of Romania. But he was also a coach. More recently we’ve seen the

development of power data analysis tools (WKO+ and TrainingPeaks.com) from the American sport

scientist Andrew Coggan, PhD. Of course, he's also an athlete - road cyclist. There’s no doubt that such contributions to sport

have had a significant impact on how athletes train. But such breakthroughs

aren’t common. It’s largely athletes and coaches, not scientists, who do the innovating.

And

so we come back to aging and how athletes are revising the way we think about

“old” people.

In

my last post here I listed some of the

performance-detracting consequences of aging that sport science has identified for

us. It’s rather demoralizing – and this is only a partial list:

Declining

VO2max

Reduced

maximal heart rate

Decreased

volume of blood pumped with each heart beat

Lowered

lactate threshold

Less

economical movement resulting in wasted energy

A

decrease in muscle fibers and strength

Less

effective and less abundant aerobic enzymes

Reduced

blood volume

Decreased

growth hormone production

Loss

of muscle mass

With sport science’s record of lagging behind sport in general it’s no

wonder that we should question their conclusions. There’s little doubt,

however, that our physiology changes as we get older. The issue is, by how

much? I’ll examine some of the above age-related changes in the next post.

September 8, 2013

Aging: Research

In

the last five posts here I’ve been examining the effects of aging on my

training, racing and life in general (vision, recovery, more on recovery and vision, race weight, performance). It appears that I’m starting to realize the consequences of 69 years of

living. Due in part to my level of physical activity for most of those nearly seven decades I’ve seen very little reason to be concerned about my decline. It’s

been minimal to non-existent. But as I explained in my last post on performance, the changes seem to be accelerating this year as I approach my 70 birthday in

a couple of months. Or are they? It’s hard to see the forest for the trees. I’m

sure it will be a year or more until I know for sure. But for right now I’m

focused on understanding what’s happening and doing my best to control the rate

of decline.

So

what is it that happens to athletes as we age? There is a ton of research on

this topic, some better than others. There are two types of studies you find when searching the

scientific literature. The most common are called “cross-sectional” studies.

These examine two groups of subjects – one “older” group (the researchers are

kind in never referring to us as “old”) and a group of young athletes. They

typically assign these groups so that gender, body size, training and other variables are

similar. Then they simply measure the physiological differences between the two

groups and assume the differences are the result of aging. These studies are relatively easy to do because, for one thing, they don’t take

much time. The study can be completed in a few weeks time.

The

other type of aging study is “longitudinal.” This is the gold standard. A group

of athletes is studied over time, often for several years or even decades, to see

what happens to them physiologically speaking. Cross-sectional studies are

hugely dependent on how the subjects were selected (was a key element of change

unaccounted for when selecting the subjects, such as lifestyle or diet or

smoking or type of work or even culture?). Something overlooked could account

for much of the change and have little or nothing to with aging. That would

render the results useless in trying to understand what happens to athletes as

they age.

On

the other hand, in longitudinal studies the independent variables are just a

part of life and can be assumed to help account, at least in part, for the

physiological changes taking place over time. They sometimes become obvious

predictors of change, such as reducing training load or stopping training

altogether. The data is more reliable since it’s real people living real lives as we follow their progress.

The downside of these studies is that the researchers must invest years and

years into following the subjects (people move, become difficult to reach and even die) and

measuring the changes the athletes experience in their lives. It may be 10 or

20 years – or even longer – until the study is completed, and there’s no

guarantee it will be published then.

So,

with all of this in mind, what does the research say we should experience as we

become “older” endurance athletes? Here’s a partial shopping list of changes as

revealed in some of the research:

Declining VO2max

Reduced maximal heart rate

Decreased volume of blood

pumped with each heart beat

Lowered lactate threshold

Less economical movement

resulting in wasted energy

A decrease in muscle fibers

and strength

Less effective and less

abundant aerobic enzymes

Reduced blood volume

Loss of muscle mass

There’s more, but that’s

enough to make you want to avoid birthday parties. Incidentally, not all of the

research agrees on all of the above results of aging.

Which of these do I seem to

be experiencing now? Is there anything that can be done to delay and reduce the

negative changes? I’ll address that in my coming posts. Stay tuned.

A Word From Our Sponsors

AudioFuel and I have created a pair of MP3 sessions that can be used this

winter as you ride or run indoors. They each take you through one hour workouts

for improving your muscular endurance, a key to becoming a better cyclist or

runner. You can find them here.

TriDynamic and I are preparing for my third annual triathlon camp in beautiful

and warm Mallorca in the Mediterranean off the

southern coast of Spain, 15-22 March 2014. The training is great and I‘ll guarantee you’ll

come away a fitter and smarter athlete. Go here for details.

September 3, 2013

Aging: My Performance

I’ve got training logs that go back to the 1970s when I

first started recording my workouts. My heart rate data started in 1983, power in

1995. I had intended to go back and review all of that before sitting down to

write this. But last weekend we flew to Lucca, Italy, where I am now. Preparing

to leave is always a hassle. But being gone from my office for two months meant

getting a lot done before the trip. I never got around to checking my training

records, so much of what follows is based on memory. And it seems the older I

get, the better I used to be.

Things appear to be changing this year. I’m not sure if it’s

my age that’s behind it, just an aberration, or the inevitable circumstances of

a busy life in 2013 with lots of travel. Of course, it could be some

combination of all of these – and more. Regardless, it’s disturbing and has me

wondering.

By “changing” I mean I’ve become less powerful. And it seems

like it happened all of a sudden. In March I tested my Functional Threshold

Power (FTP) and it was right where it has been for the last six springs when I first

started testing this marker of performance. This was done in Scottsdale, Ariz.

where I spend my winters. My summers are in Boulder. My power is always

considerably lower in the latter due to the altitude. And sure enough, my FTP

was where it always is in the first few weeks after arriving at 5500 feet –

down about 8% from Scottsdale where I live at around 1800 feet.

Usually, around a month into my adaptation to the higher

altitude about half of the lost watts come back. By the end of the summer when

I’m ready to head south to Scottsdale, my FTP in Boulder is about

what it was at the lower altitude in March. Then when I get back to the

lower altitude I see my peak FTP for the season.

But not this year. Things were different. My FTP in Boulder

never rose. It stayed at the -8% decrement all summer. And when I got back to

Scottsdale, it didn’t come up – at all. To add to the concerns, my sprint power

is the lowest it’s been since I started testing it. Could these changes be the

first signs of age catching up with me?

For many years my FTP and sprint have been about the same

with only seasonal or environmental (altitude in Boulder, summer heat in

Scottsdale) shifts. My power for specific types of workouts, especially

intervals and tempo rides (here’s the questionable memory part), has changed

very little since 1995. As a 50-something rider I was slightly above average

at, for example, time trials and climbing back then. Fifteen years later I’m a

much better-than-average senior rider for TTs and hills. I don’t think I improved;

my age peers just slowed down more. But now I may be catching up with them, it

seems.

Of course, we are all going to have reduced athletic performance in

endurance sports as we age. It’s inevitable. But we really don’t expect to see it happen - ever. And when it does, as I seem to be experiencing this

year, it’s a bit frightening.

How much of a change should we expect? And when?

There was a great study that came out of Boise State

University in 2009 – “Masters Athletes: An Analysis of Running, Swimming and

Cycling Performance by Age and Gender” (Ransdell). The problem with most

studies on athletes and aging is that they look at broad cross sections of various

age categories by gender. That means they are comparing a wide range of

abilities – front to back of pack – with motivation having a lot to do with

performance. Some people simply aren’t motivated to train. And as the number of

participants in endurance sports increases, the percentage of those who could

not care less about performance and are only doing it for social reasons is

likely to increase. That waters down the data so that we really don’t know what

the true impact of age on performance is likely to be.

The authors of the Ransdell study examined only current US

and World record holders by age groups in three sports – swimming, running, and

cycling. That means we are now able to better understand what happens when

motivation to train and compete is taken out of the equation leaving only age

and gender as the modifiers of performance.

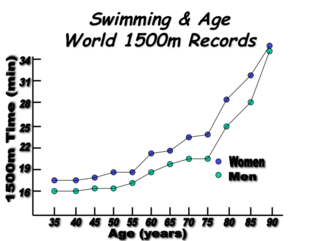

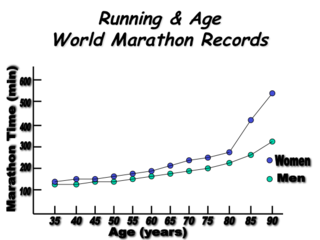

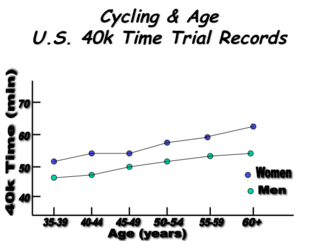

The following three charts are based on data from this

study. While the scientists looked at several event distances within each

sport, I’ve selected out only the longest and most common, long-endurance

distances – 1500m swim, marathon, and 40k time trial. On the left side of each

chart (the X axis) are the times of the records and across the bottom (Y axis)

are the age groups. The charts aren’t terribly precise but give us a good look

at trends.

Note from these charts that in the age groups from 50-59 there is a

slight decrease in performance with it being greatest in swimming (the times get slower as indicated by rising

lines). Women’s performances tend to decline even faster than the men’s,

especially in running. Swimming shows the least gender-related decline.

These findings are roughly in agreement with other papers

that also studied elite age-group athletes. For example, Wright and Perricelli

looked at the performances of senior Olympians (50+) in the 2001 National

Senior Olympic Games. Both male and female performances declined by about 3 to

4% per year from age 50 to 85, but at a great rate after age 75.

Tanaka and Seals looked at US Masters Swimming Championship

results from 1991 to 1995. They found a steady decline in performance until

about age 70 when times started declining at an exponential rate. The declines

were greater in women than in men.

Many other researchers have found similar rates of decrease

in elite master-athlete performances at national championships in swimming

(Donato, Fairbrother) and triathlon (Lepers). In the triathlon paper Ironman

age group performances declined faster than for those doing Olympic-distance

races. I’ll get to the assumed reason why from the authors in an upcoming post

here.

So it appears we can expect to slow down significantly some

time in our 50s and experience the greatest negative rates of change in our 70s

and beyond. (Want to guess what my next birthday will be? Right. 70.) The key

questions are, why are these changes taking place and what can be done to slow

them? That’s what I’ll take a look at in my next three posts.

References

Donatao AJ,

Tench K, Glueck DH, Seals DR, Eskurza I, Tanaka H. 2003. Declines in

Physiological Functional Capacity with Age: A Longitudinal Study in Peak

Swimming Performance. J Appl Physiol

94(2):764-9.

Fairbrother JT.

2007. Prediction of 1500-m Freestyle Swimming Times for Older Masters

All-American Swimmers. Exp Aging Res

33(4):461-71.

Lepers R,

Sultana F, Bernard T, Hausswirth C, Brisswalter J. 2010. Age-Related Changes in

Triathlon Performances. Int J Sports Med

31(4):251-6.

Ransdell LB,

Vener J, Huberty J. 2009. Masters Athletes: An Analysis of Running, Swimming

and Cycling Performance by Age and Gender. J

Exerc Sci Fit 7(2):S61-S73.

Tanaka H, Seals

DR. 1997. Age and Gender Interactions in Physiological Functional Capacity:

Insight from Swimming Performance. J Appl

Physiol 82(3):846-51.

Wright VY,

Perricelli BC. 2008. Age-Related Rates of Decline in Performance Among Elite

Senior Athletes. Am J Sports Med

36(3):443-50.

August 7, 2013

Aging: My Race Weight

I’ve always considered my racing weight to be 154 pounds

(70kg). Why? That’s what I weighed when I was 18 years old. Over the years my

out-of-season weight has gradually climbed. In my 30s and 40s I had no trouble staying

around 154 pounds year round. In the following decade it rose to the high 150s.

In my 60s it would climb to the mid-160s in the winter. I had to very careful

with how much I ate. I viewed weight management as calories in vs. calories out

(more on that shortly).

What I’m going to describe here is the changes I’ve made in

my diet in the past year and what the results have been both for body weight

and performance. Not all can expect the same results from dietary changes.

These are quite individualized. So please realize that I am not telling you or

anyone else how to deal with body weight issues. In fact, I usually avoid

talking or writing about either nutrition or weight. Both are hot button issues

for a lot of people and for some unknown reason produce emotional reactions. I

get angry emails from people whenever I write about either. It always amazes me

that there is such a reaction. I’m afraid some get nutrition and religion

confused. Both are generally belief-based systems. I much prefer to work with

data rather than belief. So that’s what I’m going to describe here.

With that caveat out of the way, let’s get back to racing

weight and age.

Why do we commonly gain weight as we age?

The following excerpt is from the book, Why

We Get Fat by Gary Taubes and may help to explain

what’s going as we age.

“One reason men get fatter above the

waist as they age is that they secrete less testosterone, a male sex hormone, and

testosterone suppresses LPL [an enzyme – lipoprotein lipase] activity on the

abdominal fat cells. Less testosterone means more LPL activity on the fat cells

of the gut, and so more fat.

In women, the activity of LPL is high on

the fat cells below the waist, which is why they tend to fatten around the hips

and butt, and low on the fat cells of the gut. After menopause, the LPL

activity in women’s abdominal fat catches up to that of men, and so they tend

to put on excess fat there, too.”

So, back to my personal battle with about 10 pounds of

annual fat gain. Last fall I started following Tim Noakes on Twitter. He’s the

author of The Lore of Running and several other excellent books. It just so happens that Noakes was also

dealing with a weight gain issue as he aged into his 60s. He’s a runner. He had

discovered a solution and tweeted about it frequently. In fact, he still does

(you can follow him on Twitter at @proftimnoakes). He simply adopted a

low-carb, high-fat diet (LCHF). It’s not like this was his invention. LCHF has

been around for well over a century (you can read his brief summary of this way

of eating in his new book Challenging

Beliefs). I

decided to give a try.

At first, I was a bit reluctant to do it for several reasons

which I’ll get to soon, but I’ve always used myself as a lab rat when it comes

to new ideas. I’ve discovered some interesting things this way of which I

originally was skeptical. That’s largely how the training methodology I

describe in my Training Bible books came about. I just tried new stuff I heard

of from other athletes, coaches and sports scientists. This is how I came to

eat a Paleo diet and why I now place my bike cleats

at the midsole.

So why was I a bit reluctant to give LCHF a try? Well, for

one I was concerned about my training and racing. Would my glycogen stores be

low? Might that mean poor performance? Also, we’ve been told by the US government,

the medical profession and nutritionists since the 1970s that dietary fat

causes coronary artery disease. And in my world (I enjoy racing well and

being alive!) these were big concerns. So I began to read anything I could find

on these topics. I’m not going to go into all of these here as it’s now been 10

months of almost daily reading of online articles, books and research. (If interested

in an introduction to these topics I’d suggest reading The Art of and Science of Low Carbohydrate Performance and Good Calories, Bad Calories as starting points.)

After initially reading both sides of the issues, I decided

to give it a try. The bottom line is that last fall I lost 8 pounds in 9 weeks

by eating more fat and less carbohydrate. That was 5% of my body weight (160

pounds – at the time I was well on my way to my normal winter weight). I was

never hungry. In fact, it seemed like the more fat I ate, the more weight I

lost.

I learned that weight loss is not just calories in vs

calories out. I used to lose weight that way. It works in the short term. When it was time to

lose weight in the base period I’d workout, estimate the calories burned and

not quite replace all of them. But there is an obvious downside. Not replacing

the calories means you are hungry - a lot. So in order to lose excess fat by

relying on not replacing expended calories, I had to be willing to put up with

hunger. This isn’t easy for me or anyone else. But I used to view it as one of

the “sacrifices” I must make to perform well. As soon as the race season ended and

I abandoned frequent hunger the weight would slowly come back. Hunger is not

pleasant. There is a limit to how long I could put up with it.

What I learned from all of this is that weight loss can also

be achieved by changing the foods I eat. Hunger does not have to be an issue.

This is where LCHF comes in. It has to do with insulin production and also with

something called “insulin resistance” in more extreme cases than mine. (I’m not

going to go into the physiology of insulin here as that’s a bit outside of the

scope of this post. But if you want to read the details go here and here.)

The primary change I made was greatly reducing sugar and cutting

back on fruit. I used to eat 5 to 7 servings of fruit a day. That’s roughly 600

calories of carbs from fruit, about 20 to 25% of my calories for the day. I now eat less

than one serving per day on average. Foods high in fat I now eat a lot more of

are olive oil, coconut milk, nuts, nut butter, eggs, avocado, and bacon along

with the normal Paleo foods I’ve eaten since 1994 — animal products, especially

fish and poultry, and vegetables. Foods high in fat I eat only a little of are

dairy products. I avoid as best I can trans fats (“hydrogenated” on the label)

and omega 6 oils (for example, soy, peanut, cottonseed, corn, safflower). Both

categories are found in almost all processed and packaged foods in the grocery,

especially junk foods. I seldom eat grains — probably less than one serving per

month. I once used these as recovery foods on an almost daily basis.

So what’s happened to my training and performance since the

switch to LCHF?

During rides I take in only water unless it lasts longer

than 4 hours. In that case I will carry a sports drink in one bottle and save

it for the latter portion of the workout. I typically do intervals of various

intensities both above and below the lactate threshold, tempo, and aerobic

endurance sessions. These are all less than 3 hours. Water only. In the summer

I do rides well in excess of 3 hours in the mountains of Colorado with Intensity Factors generally between 75 and 85%. I’ve done rides of greater than 5 hours several

times this summer at 70 to 80% taking in no more than a few ounces of a sports

drink. There has been no bonking, unusual fatigue or loss of performance from how

I’ve done in the past when I was taking in a lot of sports drink.

So what’s going on? Apparently my body has adapted to using

more fat for fuel thus sparing glycogen since my diet changed back in October.

In exercise physiology terms this would be called a lowered respiratory

quotient (RQ).

I should point out that eating a LCHF diet has not directly

improved my performance. I’m not faster now than I was before. This is common

in the research I’ve read on the topic. What it has improved is getting to and

staying at race weight without calorie counting or hunger.

Of course, what’s missing in my recent experience is long

road races with lots of deeply anaerobic efforts with each lasting several

seconds to a few minutes. I’ve not been able to do any such races this year (a long

story that has to do with my annual pilgrimage from Arizona to Colorado every

summer). It could well be that my top end power in frequent max efforts during

a race won’t be sustainable on this diet. Such efforts are typically the determiners

of road race and criterium outcomes. But I don’t see any downsides for steady

state events done at or below the lactate threshold. This would include non-drafting

triathlon, road running, and time trialing.

Will this work for you? I can’t say. There are simply too

many variables when it comes to the metabolic systems of individuals. All I’ve

done is an experiment with 1 subject – me. And, obviously, there was no control

or double blind administration. There’s only one other person who has tried it

along with me – a friend of many years, Bill Cofer. Bill is a 65-year-old, serious

recreational cyclist who has been trying to shed more than 30 pounds for the

last 20-some years by restricting calories. He started a LCHF diet in February

and has so far dropped 27 pounds. His experience with hunger and refueling in

workouts has been much the same as mine.

Okay, so now I have n=2. But again, that doesn’t mean you

should expect the same results.

This post is not intended as a general guideline for all

aging athletes on “how to lose weight” or “how to improve performance.” It is

simply a description of something that seems to have been working for me for

about 10 months. I’ve still got a lot of learning to do on this subject.

As always, your comments on personal experiences with an

LCHF diet would be greatly appreciated.

July 16, 2013

Aging: Update on Recovery and Vision

It seems there is never enough time to do all I want to do.

By the time I watch the Tour de France, work out a few hours, answer emails (it

seems that is what I mostly do these days), and other stuff I can’t always

account for, there is not enough time left to devote to things I enjoy such as

writing. I expect you have the same problem. I thought when I cut back on

working (I’m now retired from full-time coaching—more on that at another time)

that there would be more free time. Ain’t so.

Back to Recovery

Speaking of aging, I was in the mountain community of

Breckinridge, Colorado on the July Fourth holiday weekend. While there it

dawned on me that there is another aspect of my recovery I didn’t mention in my

last post on the topic.

My family drove up to Breck on the afternoon of July 3. That

morning I did my normal Wednesday workout in Boulder: 2 x 25-minute hill climbs

on a 9% grade at about 90% of FTP followed by 8 to 12 minutes of short,

anaerobic endurance intervals at 120% of FTP. These latter intervals are also

on a hill, but not as steep. With warm-up and cool down the session lasts about

2.5 hours. It pretty well leaves me wasted for a day or so.

What struck me while in Breck was that two days after the workout,

despite riding easily and sleeping and eating well, I was still not even close

to being recovered. That’s unusual. Then it dawned on me: I was living and

sleeping at about 9600 feet (3100m) and my “easy” rides had taken me to over

11,000 feet (3600m). You simply don’t recover as quickly at such altitudes.

The same is true when back in Boulder, where I spend my

summers. Our home here is about 5200 feet (1680m). That altitude also has

negative consequences for recovery and makes sleep, nutrition and everything

else I do to hasten recovery even more important. There’s an obvious difference

to how much training stress I can manage here as compared with Scottsdale,

Ariz. where we stay in the winter – 1800 feet (580m). In Boulder I can manage

only two high-stress workouts per week. In Scottsdale it’s usually three and

even four when in the base period.

The aerobic-enhancement advantage of living at a high

altitude may well be offset by the slower recovery and decreased power

production of all workouts. (What I’ve learned about how to modify training at

altitude is a another topic for a future post.)

Also of interest on this topic of aging and recovery are the

comments that older athletes have posted and the emails I have received from

others in the past two weeks. Most have agreed that they also have experienced

a slowing of their recovery rate as they age. The most common solutions they

report using are decreasing the total weekly workload and allowing more time

for recovery between challenging workouts. Please continue to give me your

thoughts on this.

And My Aging Eyes

I guess this could be called an ad for one of my sponsors,

but it’s warranted. I managed to break my every-day glasses last week. And I

only brought one pair with me from Scottsdale. That made driving at night,

going to movies and watching TV a bit challenging. So I asked ADS Sports Eyewear, which I

mentioned in a previous post on this topic, to make some replacement glasses with clear lenses for me using the same frame

as they used for my prescription Oakley sunglasses. I had them in a week and I’m happy to now have my vision back. They’re fast

and the quality is excellent. Thanks ADS!

Moving On

The next topic I want to write about is another common one

for aging athletes: weight gain. I hope to do that as soon as I get caught up

with email.

June 30, 2013

Aging: My Recovery

When I was

in college around 50 years ago (wow, am I really that old?) I was a runner on

the track team. The coach used to have us do what I now call "Anaerobic

Endurance" intervals 3 to 5 times each week. Back then I called them

"intervals 'til you puke." Because that's basically what we did.

We'd warm-up

on our own and then the coach would blow his whistle. That meant we were to jog

over to where he was sitting in the stands next to the start-finish line on the

track. He looked a bit like Buddha with a whistle, stopwatch and can of Coke.

We knew what was next: 440-yard intervals (we didn't have metric tracks back

then) with short recoveries. We never knew how many we were going to do, how

fast we should run them (other than "as fast as possible"), how to

pace them or how long the recoveries were going to be. We may wind up doing a

dozen or 15 or 7. Nobody knew, not even the coach. When people started throwing

up he'd give us a longer recovery and only a couple more intervals. We always hoped

that someone would toss their cookies so we could get it over with as soon as

possible. That's sports science 50 years ago.

Interesting

thing was, in my youth I could do that workout night after night for days and

even weeks with only 2 days of recovery in a week (no one trained on the

weekends back then). And I would be ready to go hard again the next day. Today

if I tried to do 3 to 5 AE interval workouts ('til I puked!) in a single week

I'd soon be totally wasted and by the third back-to-back interval day my

performance would be going rapidly south. The fourth or fifth such session (if

I managed to even start them) would be a joke. There's simply no way I could do

that workout day after day now.

In fact,

this is what I hear from nearly every aging athlete I talk with about getting

old. There is little in the way of research on this, especially with truly

“old” athletes, by which I mean over age 55. But one study from a few years ago

compared the perceptions of 9 older (45 +/-6 years) and 9 younger (24 +/-5

years) well-trained athletes (1). All of the subjects did 3 consecutive days of

30 minute time trials. Each reported their subjective measures of soreness,

fatigue and recovery daily. While there were no significant changes in

performance over the 3 days for the subjects in either group, the older

athletes reported significantly higher levels of soreness and fatigue and lower

levels of recovery.

One study

isn’t much in the way of evidence, but based on what I’ve experienced and what

older athletes tell me, it seems to be the case. We simply don't recover as

quickly as we did when younger. And it seems getting everything dialed in just

right is increasingly critical to our recovery. The two most critical are sleep

and nutrition--as they are for all athletes. It's just that when you are young

you can mess these up and still get away with it. In college I'd stay up most

of the night studying, eat crappy food, and still manage to do "puke

intervals" several times a week with little degradation in performance.

The

few studies I can find on the topic of nutrition, recovery and aging, indicate

that older athletes may need more protein in recovery than do younger ones

(2,3). This implies that there may be a reduced need for carbohydrate during

recovery. In fact another study found that healthy, elderly men (non-athletes)

had a reduced capacity to oxidize carbs and an increased capacity to use fat

for fuel (4). Whether or not this also applies to athletes is currently open

for conjecture.

I've been

doing some tinkering with my nutrition in the last 8 months and the results have been

really interesting. I'm going to devote an entire post to that soon, so won't

touch on it now. Whatever you've found works well for you when it comes to diet

simply can't be compromised as you get older. Only a few aging athletes who are truly unique can continue eating lots of junk food and still perform at a high level

well into their 50s, 60s and 70s. I've certainly found that I can't.

Sleep is an

interesting phenomenon. In college I could sleep 10 to 12 hours straight on a

weekend regardless of whether I was in-season and training hard or not. Now it seems I only need 6 to 7 hours a night

regardless of training. It's rare that I sleep more than 7. I don't know what's

going on here, but I've had a few other senior athletes also tell me this. But

it's got to be every night. I can’t

miss a few hours of sleep like I used to and still perform well.

I know of

some older athletes who swear napping is successful for them. I don't doubt

them at all, but it seems there is no way to fit that into my lifestyle.

Something would have to change. Maybe you can do. It's probably a good thing.

So that's

the Big Two for recovery--sleep and nutrition.

I've also

tried lots of stuff beyond those two to speed recovery. Some have helped a

little (compression socks, elevating legs, massage, cold water immersion, and

some new recovery products such as Firefly and Barefooter shoes). Of course, when the change is barely perceptible I always

wonder if it's a placebo effect or "real." The only thing I've found

that seems to have a significant

impact on speeding up my recovery from hard workouts is “Recovery Boots.”  (That’s my granddaughter, Keara, demo’ing the Boots in this picture.)

(That’s my granddaughter, Keara, demo’ing the Boots in this picture.)

I got these

two years ago and, as always, was somewhat skeptical at first (it’s a good idea

to be skeptical of everything as we motivated athletes tend to buy

any snake oil that comes along if we think it may give us a slight edge). But

that never stops me from trying something. (I like to use myself as a lab rat,

as you’ll see in my next blog post.) I was soon convinced. I use them after all

hard workouts and races now. Typically, I spend an hour in them in the evening

after a high workload day. They are a bit like the combination of massage and

compression garments. They slowly inflate starting at the foot and ankle, next

apply pressure up the lower leg, then the knee and lower thigh, and finish with

the upper thigh. The pressure is released and it starts over again. By the next day my legs are noticeably more recovered than

when I don't use them (which happens when I travel). Again, is it placebo? I

don't know but I'm unwilling to go without them for several days to find out.

I'd be

interested in hearing what other older (50+) athletes have found works for them

when it comes to recovery. Please feel

free to post a comment here. I've been thinking about writing a book on this

subject, so any ideas and leads I can get from you would be much appreciated.

Thanks.

1. Fell J,

Reaburn P, Harrison GJ. 2008. Altered perception and report of fatigue and

recovery in veteran athletes. J Sports

Med Phy Fitness, 48(2):272-7.

2. Thompson

LV. 2002. Skeletal muscle adaptations with age in activity and therapeutic

exercise. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther,

32(2):44-57.

3. Dorrens

J, Rennie MJ. 2003. Effects of ageing and human whole body and muscle protein

turnover. Scand J Med Sci Sports,

13(1):26-33.

4. Krishnan

RK, Evans WJ, Kirwan JP. 2003. Impaired substrate oxidation in healthy elderly

men after eccentric exercise. J Appl

Physiol, 94(2):716-23.

Next: Aging

and my nutrition.

June 10, 2013

Aging: My Eyes...

and Prescription Cycling Sunglasses

It's been quite a while since I posted here. I used to think I was simply too busy due to travel, but now that I'm on vacation in Boulder for the summer I'm coming to realize that I'm just lazy. It's well past the time to get involved again.

-------------------------------------------------

Lately I've been thinking a lot about my age.

I’m 69. When I was younger it never occurred to me that I’d

ever be this old. But some how it happened. In the following weeks I’ll write

about some of the physiological changes I’ve experienced due to aging and what

I’ve learned about them. It isn’t pretty. Some are big deals – such as tendencies

to add body fat and slow recovery from exercise. Others are merely nuisances.

That’s where I’m going with this first post on the topic.

One of the greatest inconveniences of aging, I’ve found, is the

loss of near vision – the need for bifocals. It seems that every product on the

market, from home thermostats to cell phones, was designed by someone who is 30

years old with excellent eyes. Why do they all use such small fonts? Don’t they

understand that it’s mostly people over 50 who can most easily afford them? In

this hard-to-read category are bicycle handlebar computers and head units.

Some head units are easier on old eyes than others. But in

the aero position with the head tucked in and low, the only way to read my

Garmin 800 is to raise up to get some distance between my eyeballs and the head

unit thus greatly increasing drag, or to wear bifocals which is beyond

nuisance. I’ve tried stick-on bifocals on my prescription Oakley sunglasses. That didn’t work too well. I’m nearsighted so having a bifocal on top of the

prescription lens made for fuzzy vision up close. They worked OK with non-prescription

sunglasses but became cloudy over time. And without the prescription lens,

looking up the road was always a bit blurry. Exasperating.

Recently I heard of a company making prescription-cycling

lenses using a new digital technology - ADS Sports Eyewear. So I had a

pair of lenses made for some Oakley frames.  What a difference! Now with a free-form,

What a difference! Now with a free-form,

digital, progressive bifocal I can easily read my head unit while low in the

time trial position, and I can see clearly up the road. It’s remarkable how

such a seemingly small thing as this could so greatly improve my enjoyment of

riding a bike.

In addition, my peripheral vision with a wrap-around frame

is just as crisp and clear, as it is front and center. And the ADS lenses are

no thicker than my old non-prescription Oakley lenses. This is a clear

improvement over the prescription, wrap-around sunglasses I’ve had before with

the corrective lens “sandwiched” on to a standard, non-prescription lens. That

technology made for limited peripheral vision and bulky, ugly sunglasses – and without

bifocals.

I was so impressed by ADS’s lenses and service that I asked

them to be one of my sponsors (you can see them in my new sponsor section on

the right side of my blog home page).

The price for a pair of ADS sunglasses depends on several

variables. ADS can use your existing frames so long as they are in good

condition and will work with their lens. The lens-only price ranges from $119.00 for a clear, single vision lens

to $219.00 for the polarized version. A progressive bifocal section in

the bottom will add about $200.00 to the lens price. Or you can buy a

lens and frame package. Frame

prices average between $79.00 and $200.00. Standard cycling frames are

available from several companies such as Oakley, Nike, Adidas, Kaenon, Wiley,

Bolle and Smith. The ADS web page for cycling sunglasses shows your options. All of the

sunglasses on the page are prescription-ready.

In my next post

I’ll comment on recovery devices I’ve been trying out over the last several months and what I’ve discovered

about them. All, of course, from the perspective of aging. That will be

followed by the topic of body weight and aging. Again, I’ve been tinkering,

reading research and found some interesting stuff.

Joe Friel's Blog

- Joe Friel's profile

- 91 followers