Joe Friel's Blog, page 11

April 24, 2013

Another Block Periodization Study

Earlier this month I reported on a study of block

periodization that found it superior to a traditional (linear) periodization model. This

study lasted 4 weeks with well-trained cyclists in the two groups (Block and Traditional

periodization) doing the same workouts. The only difference was that the Block

group did 5 of the 8 high intensity training sessions (HIT) in the first week

and then only 1 HIT per week in the following 3 weeks. The Traditional group

did 2 HIT each week. They both also did low intensity training (LIT).

The results were rather remarkable. The Block group had an

increase in VO2max of 4.6%, peak power at VO2max rose 2.1%, and their power at

approximately their aerobic thresholds rose a whopping 10%. There were no

changes for the Traditional periodization group, which seems strange but may

tell us that 4 weeks of traditional periodization is not enough to stimulate

significant change. Perhaps.

So along comes a 12-week follow-up study from the same Norwegian group of researchers at Lillehammer University. They

used the same study design only did the above 4-week mesocycle 3 times for

each group. The results were even more remarkable. I’ll come back to that

shortly. But first let’s take a look at what the researchers called “high” and

“low” intensity workouts.

Using heart rate monitors, all workouts were divided into

three zones:

Zone 1 60-82% of max HR (MHR)

Zone 2 83-87% of MHR

Zone 3 88-100% of MHR

At 82% of MHR an athlete is usually in the vicinity of their

lactate threshold heart rate (LTHR), the point at which heavy breathing begins

and is marked by the sensation of being “redlined.” Some athletes’ LTHRs are at

a higher percentage of MHR and some are lower. (This is why I recommend LTHR

rather than MHR for setting up heart rate zones; it’s simply a more accurate

way of defining the most critical heart rate intensity for serious athletes.)

All of the cyclists (15 well-trained riders) in this study

did LIT in zone 1. Their HIT was in zone 3. These HIT sessions are critical to

understanding this study as these are more than likely what produced the

remarkable results.

All HIT was done as intervals. They did either 6 x 5 minutes

at zone 3 with 2.5-minute recoveries, or 5 x 6 minutes at zone 3 with 3-minute

recoveries. So they totaled 30 minutes of zone 3 in a single session. These are killer workouts. Extremely hard. If you

use my heart rate zone system, their zone 3 is the equivalent of my high zone 5b

and zone 5c. In other words, the athletes were doing intervals at right around

their VO2max. Other research has shown that well-trained cyclists can only maintain their VO2max velocity for

about 3 to 5 minutes. VO2max velocity and VO2max heart rate aren’t exactly the

same thing but I think it safe to say that each interval was nearly a max

effort. And the recoveries were very brief. For a VO2max interval I usually

assign a recovery after each that is about the same duration as the preceding

high-intensity piece. Here they did recoveries that were only half as long.

I wouldn’t recommend doing such a workout, let alone 5 times

in a week as the Block athletes did in this study. I can imagine how difficult

it must have been for the subjects to finish each subsequent session in the 5

HIT-session weeks (in weeks 1, 5 and 9).

But the results were, indeed, impressive. And as may be

expected, the numbers were higher than with the 4-week study I reviewed above.

In this more recent research VO2max for the Block athletes rose on average 8.8%

compared with 3.7% for the Traditional group. Power at 2mmol/L lactate (about aerobic

threshold) rose 22% for Block and 10% for Traditional. They also did a

40-minute time trial to see what average power they could produce. The Block

athletes’ rose 8.2% while the Traditionals’ went up 4.1%. The difference

between these time trial results was insignificant.

The protocol used for the Block group in both of these studies is similar to

what is sometimes called “crash” training as described in my Triathlete’s Training Bible, Cyclist’s Training Bible, and Mountain Biker’s Training Bible books. In this extreme training strategy, workload is greatly increased for

several days followed by several days of reduced training. This has been shown

to stimulate significant changes in fitness, but the risks are also extreme.

You can read more about it in my books.

This is an excellent study as research on periodization of

endurance athletes is rare. There are only a few as most use weight lifting as

their sport focus. And the fact that this one lasted 12 weeks also makes it

exceptional. The downside of all periodization studies is what I mentioned in

my last piece on the subject—both the subjects and the researchers know who is

following which protocol. That always introduces the placebo effect as a

variable.

Nevertheless, I am convinced that block periodization is

superior to traditional (linear) periodization for the advanced athlete. By “advanced” what I mean is someone who

has been training seriously and consistently for years, has attained a very

high level of performance, and is so close to their potential that producing

greater fitness improvements is extremely difficult to do. Most professional

endurance athletes and elite age group athletes fall into this category. They

would more than likely benefit from a block periodization program—if they know

how to do it. It’s not as simple as it seems from these studies and requires

careful planning to pull off.

Athletes who are not what I am calling advanced here are

still better off following a more traditional periodization program as

described in my books. For them a block plan may well produce a loss of fitness

since the training emphasis is focused on only one or two abilities in each

mesocycle.

Crash training may be done by either group but must be used

with caution as it can easily result in injury, illness and burnout. Again,

read more about it in my Training Bible books before attempting it.

April 11, 2013

Tapering and Peaking Review

I was asked twice this week how I taper athletes for their

A-priority races, once by an athlete and also by a coach. I told them that I

would write about it in my blog, but later realized I had already done so several

times. So rather than do it all over again I’ll just provide the links to four posts on the topic. I’ll also summarize

each so you can pick out the one that best matches your interests, should you

want to read about it (click on the title to go to the post).

In this post from 2009 you will find an explanation of the

three elements of race preparedness – fitness, fatigue and form. This is

essential to understanding what’s happening when you peak properly. It goes on

to describe the basics of the peaking process through the interplay of

intensity and rest/recovery with an emphasis on the latter.

This post is also from 2009 and is a follow up to the one

above providing graphic illustrations of how I taper and peak athletes. This

will make much more sense if you use a power meter (bike) or speed-distance

device (run) along with the Performance Management Chart (PMC) at TrainingPeaks or WKO+

software.

The two charts show the actual peaking design for a road cyclist and an Ironman

triathlete.

Here you will find a discussion of how I was preparing a

road cyclist for his A race. The PMC for the athlete is also provided along

with more subtle nuances of the indicators of race readiness.

Tri vs. Roadie

Peaking Power Distribution

As the title implies, this very short piece uses two of the

athletes I coached in 2010 – a 70.3 triathlete and a road cyclist – to compare

graphically how their bike power was distributed by training zones as they went

through their final preparations for their A races.

If you search for “peaking” on the home page of my blog you’ll find much more detail on peaking including topics such as

projecting race readiness, strong and weak form, and peak performance

predictors.

April 4, 2013

Updates on Compression Clothing and Block Periodization

One of my favorite pastimes is reading sports science

research. Most days start with me grabing an abstract from the top of my to-be-read list and seeing what’s new. I know,

I’m weird that way. But I expect we are each strange in some way. My weirdness occasionally pays off. Recently I came across some new studies on topics I’ve

written about before – compression clothing and block periodization. Here are

some research updates.

Compression clothing

I first wrote on compression clothing in October 2007 after seeing so many athletes in the Hawaii Ironman wearing them in the race

that year. They continue to be used extensively in many endurance sports. There

wasn’t much in the research literature on them then, and over the years only a

little has been added. I’ve continued to follow the topic and done updates

periodically (March 2009, February 2011, May 2011). Here are two more recent studies followed by comments.

de Glanville KM, Hamlin MJ. 2012. Positive effect of lower body compression garments on subsequent 40-kM

cycling time trial performance. J Strength Cond Res,

26(2):480-6.

Fourteen

male triathletes were divided into two test groups. One group wore a full

leg-length compression stockings and the other a similar looking non-compression

garment continuously for 24 hours after a 40k time trial. Following the day of

recovery while wearing the stockings they took them off and once again did the

40k TT. One week later the groups reversed the clothing worn and repeated the

entire 40k time trial-24 hours of recovery wearing the socks-40k time trial

protocol.

After

wearing the compression stockings performance time in the second time trial

improved, on average, by 1.2% and average power increased 3.3% compared with

wearing the non-compression stockings. The athletes’ rating of perceived

exertion during the subsequent tests did not change significantly.

Born DP

, Sperlich B, Holmberg

HC. 2013. Bringing light into

the dark: effects of compression clothing on performance and recovery. Int J Sports

Physiol Perform, 8(1):4-18.

This is a review of the existing literature on the effect of

compression garments on performance and recovery. The review found little

change in performance while wearing the garments, but they noted improvements

in recovery when the subjects wore them.

My opinion on compression clothing has not changed since I

first wrote about them five years ago. I doubt there is a significant

improvement in performance while wearing them. In a triathlon, the time to put

them on in T1 is probably greater than any time gained while wearing them. But

there may be a post-workout benefit that could speed recovery prior to the next

workout or race. I’ll keep watching for this topic in the literature and let

you know what I find.

Block periodization

Back in 2011 I described a relatively new way of organizing training

time for advanced athletes called “block periodization” (here, here and here). In block periodization the athlete focuses on only one or two aspects of

fitness (what I call “abilities:” aerobic endurance, muscular force, speed

skills, muscular endurance, anaerobic endurance and sprint power) within a

block lasting for a short time – usually three to six weeks. As explained in

the above previous blog posts, block periodization is intended only for

advanced athletes. Moderately trained athletes are best advised to follow a

linear (“classic “or “traditional”) periodization plan as described in my

Training Bible books.

There is very little research done on periodization and that

which is available usually uses strength athletes as subjects. Such studies of

endurance athletes are rare. But here is one that is a recent update on the

topic of periodization.

Rønnestad BR, Hansen J, Ellefsen S.

2012. Block periodization of

high-intensity aerobic intervals provides superior training effects in trained

cyclists. Scand

J Med Sci Sports.

Nineteen experienced and fit cyclists were divided into two

groups for this Norwegian study comparing block and traditional periodization.

Each group trained for 4 weeks and did 8, high-intensity interval sessions and

otherwise low-intensity aerobic training. Their training volume, both for high-

and low-intensity workouts, was the same over the 4 weeks. The only difference

was how the weeks were structured.

The 10 riders following the block periodization protocol did

5 of their 8 interval sessions in the first week and then only one each in the

last 3 weeks (along with the low-intensity sessions). This concentration on only

one ability for a brief period of time followed by maintenance is common in

block periodization.

The other group of cyclists who followed the traditional

periodization plan spread the 8 intense workouts over the 4 weeks doing 2 each

week along with the low-intensity sessions on the other days.

So what was the result? Those following a block

periodization program improved their VO2max (one physiological indicator of

aerobic fitness) by 4.6% (+/-3.7%). This group started with an average VO2max

of 62.2 mLO2/kg/minute so they bumped the average up to just over 65. Their

peak power at VO2max increased by 2.1% (+/-2.8%). And this group elevated their

power at 2mmol/L of lactate (approximately their aerobic thresholds, similar to

low zone 2) by 10% (+/-12%). The traditional periodization group saw no significant

changes in these same metrics.

The block periodization group’s numbers are all remarkable

given that the gains would have almost certainly been attained in just the

first week with only 5 hard workouts. That makes me wonder. One of the problems

with such a study is that it isn’t possible to use a double-blind protocol in

which neither the subjects nor the researchers know who is following which

protocol. This raises the question of a placebo effect. But also note that some

of the block periodization subjects had decreases in both their VO2max (-0.7%)

and aerobic threshold (-2%) power. That’s a good sign in a way as it confirms

what happens in the real world – some positively respond to the protocol and

some get worse. It happens in nearly all aspects of training. Such is life.

So far the few studies I’ve seen on the topic have indicated

that there may be good reasons for advanced and highly fit athletes to follow a

block periodization program. If you fall into this rather small club be sure to

read my other blog posts listed above before making such significant changes to

your training.

March 5, 2013

Keep It Simple - Bike Skills

There have been some big gaps between my posts here this

winter. This is my busy season with lots of travel. It seems there is never

enough time. I’m sure you know the feeling.

In my last blog as an intro to the topic of keeping it simple I explained how I've

been on a quest the last couple of years to make training more user friendly by

focusing on those few things that are most likely to produce rapid and positive

change – what I've come to call the "Big Rocks." I also explained there that the most basic of

the Big Rocks is skills. Unfortunately, this is usually the last thing

endurance athletes are concerned about because many see aerobic and muscular

fitness as the only aspects of fitness that are truly important to performance.

But skills are also related to fitness, just not in a way we’re used to.

Most athletes could make significant and often immediate

improvements in performance by refining their sport-specific skills. By

"skills" what I mean is the ability to make the movements of the

sport in an efficient and effective manner.

"Efficiency" in sport has to do with the metabolic

cost of movement – how much stored energy, especially carbohydrate (glycogen

and glucose), it takes to make the movement. If the cost is higher than what is

necessary and common for advanced athletes then the inefficient athlete, in

order to go faster, must either produce excessive effort (and hence a greater

cost) or figure out how to reduce the expense (more skillful movement). Most

opt for the first choice and give lip service to the second.

I'm using "effective" here to mean making the

movements of the sport in such a way as to produce intended and beneficial

performance results. In other words, an effective endurance athlete is one who

is fast and powerful. This usually also requires making changes in one’s

skills.

So what I'd like to do next is get down to the Big Rocks of

efficiency and effectiveness – the skills of sport. And since the readers of

this blog are typically triathletes and road cyclists I will focus on three

sports — swimming, biking, and running. In the interest of the cyclists I'll

start with the bike so they can skip the swim and run posts that are to follow

(when I again find time!).

There is only one Big Rock for cycling. Pretty simple. This

is the starting point every season

for every cyclist regardless of the

their level of performance – pro or novice.

Get a Bike Fit

This is so simple it's almost embarrassing. Regardless, get

a bike fit done every year at the start of the winter base training period.

Yes, every year. Even if it’s the

same bike you were fit on last year. Things change. You get stronger or weaker,

more or less flexible, have developed a little niggling injury or gotten rid of

one, will do different types of races in the coming season, or forgot that you

lowered your saddle by 3mm six months ago or changed to a new stem. You may

also learn, unfortunately, that the bike you are riding simply doesn't fit you.

The frame is too big or too small. I hope that isn't the case as it means a big

out-of-pocket. I see riders in this sad situation in almost every race I go to,

especially triathlons.

Go to a professional bike fitter to have this done. Don't

have your spouse or friend do it (unless he or she is a professional fitter).

Don't ask a training partner to take a look while you're riding along. Use a

professional. Bike fitting used to nearly be all art; now it is mostly a

science. A good fitter will put you in a position that optimizes your physique,

physiology, and purpose. You'll learn how to sit on a saddle (many do it

wrong), what your head, spine and hip posture should be, and how to be more

aerodynamic.

The bottom line is that your pedaling and bike handling efficiency

and effectiveness will improve after a good fit. You’ll waste less energy and be

more powerful. And your risk of injury in the coming season will be decreased.

If you are a road cyclist who does crits, road races and

time trials you'll more than likely need two bike fits. Triathletes typically

need only fit the bike they race on.

If you're unsure who to go to for a fit ask around with

others in your sport. A good fit will cost you a few bucks ($100-200 is common

in the US but can be a lot more depending on what is done). If you are truly

serious about improving performance on the bike it's some of the best money

you'll spend. You'll come away after an hour or two as a better cyclist without

even breaking a sweat.

In the next post I’ll write about swimming. While becoming

more efficient and effective on the bike is quite simple, the swim is much more

complex.

February 18, 2013

Keep It Simple

Training for peak performance in endurance sport does not

need to be complicated. I came to understand that only recently. More than 30

years ago I earned a masters degree in exercise science while competing in

endurance sports. One thing I always liked was the complexity of training. I'm

a nerd at heart--or at least an "engineer" who likes to solve the

difficult problems. To date I have written or contributed to 13 books on the

topic. All have been somewhat complex, at least to many who have read them and

written to me with questions. They never seemed complex to me, but they apparently were.

In the last couple of years I've tried to simplify things.

This started because so many athletes, especially triathletes, kept asking me

the same questions after reading my best selling book of the bunch, The Triathlete's Training Bible. My first book, The Cyclist's Training

Bible, was the same way, I suppose, but since there was only one sport to master it came across as less complex. Simplicity and brief statements of how to do it were clearly missing

from both. So a couple of years ago I wrote Your

Best Triathlon which, essentially, walks the serious triathlete through his

or her season by suggesting weekly and monthly routines along with daily

workouts as the season progresses toward the first, big A-priority race of the

year. I've gotten very few questions from the readers of that book asking what

they should do or why, since that was described in each chapter. (A similar

book for road cyclists is still lurking in the back of my mind.)

In the past year I've done clinics and camps (see my 2013 appearance schedule in the right hand column of this page--click here if viewing this in an email) in which I've

tried to further simplify training. It's amazing how much better athletes perform when they fully understand what they need to do to improve

and how to go about making the changes. When I'm with athletes in clinics and

camps I tell them about the "Big Rocks"--the very few, most important

things that must be done to improve performance. And I do mean "few."

There really aren't that many things one must do to perform well in endurance

sport. The key is knowing what the Big Rocks are and incorporating them.

There are lots of "little rocks"--and even tiny

sand particles--that many in sport science and coaching insist must be done by

every athlete. I used to subscribe to this way of seeing training, also. And,

I'll have to admit, still like discussing the merits of such minutiae. With a

background in exercise science it can be fun to talk about "how many

angels can dance on the head of a pin" with another would-be scientist.

The little rocks, and even the sand particles become

increasingly important as the absolute performance of the athlete improves. At

the highest level of sport everything is a Big Rock. There's no room for anything to be

done even somewhat haphazardly for a world class athlete, especially one who

makes a living from competing. But it isn't that way for the rest of us "normal" people.

So how did I come to this simplified conclusion in my

coaching career? Golf. Yes, golf. Talk about a game with a lot of little rocks!

I started playing in 1966. By 1972 I had mostly given up the game due to the

pressures of earning a living and being a father. Becoming good at golf is at

least as challenging as becoming a good endurance athlete. By 1998 my wife had

started playing so I saw the game as a good way for us to spend quality time

together. As training partners we were a failure--the couple workouts were too

easy for me and too hard for her. Golf would allow us to spend some time

together each week. I had no idea I'd come to take it so seriously.

I figured, and rightly so, that the best way to learn the

game would be to do what I tell serious endurance athletes to do--hire a coach.

Over the last 15 years I've had perhaps six golf coaches. My handicap, the best

gauge of how you are doing, has gone from 19 to 7. Lower, in this sport, is

good. The coaches get most of the credit for this.

The best golf coach I've had is the one I'm now wroking with--Kay Kennedy, a former LPGA

player, who is now an instructor at McCormick Ranch Golf Course in Scottsdale,

Ariz. What Kay is good at is keeping it simple. I listen to other instructors

on the practice tee with their clients and hear a lot of little rocks. All it

seems to do is freeze the student. They will stand staring at the ball in the

address position for a looong time before initiating a feeble, and obviously,

confused swing. During the time in which they appear to be golf statues they

are going through a long checklist of what all must be done in the 1.5 seconds,

at most, that the ensuing swing will take.

Kay simplifies

it. She will watch me hit a few shots and suggest one small change.

Then we work on that one for the remainder of the lesson until it is well

engrained. That's largely the reason my handicap has dropped by 3 strokes since

I began working with her about four years ago. It's simple.

I soon learned to adopt and adapt her recipe for simplicity

and teach it to those I am trying to help in my clinics and camps. The camps are by far the

best when it comes to obvious performance improvement. By the end of a

triathlon camp, which I do far more of than cycling camps (another entire blog

post could address why this is), the improvements are usually obvious and measurable in a matter of a few days.

The starting place for these improvements is the refinement

of skills. Endurance athletes, with the possible exception of 1500-meter pool

swimmers, show little more than a passing interest in skills. For us it's

cardiovascular and, perhaps, muscular fitness that really matters. Everything

else is a distant third. But most amateur athletes would see a bigger return on

their time investment, at least initially, by mastering the skills of their

sport rather than trying to continually push their heart rates higher in some

strange quest to find their max beats per minute.

Skill is the true heart and soul of any sport. If one is

sloppy in their movements, energy is wasted and it takes a great deal of

"extra" fitness to overcome the loss. I've learned to start my camps

and clinics with skill refinement. It's remarkable how rapidly the athletes

improve after that.

But keeping it simple is much more than just skills. It's

also how we train--the daily workouts, the weekly scheduling, and the long-term

planning. In the next couple of posts, as time permits (this is my busy time of

year with camps and clinics), I'll touch on the Big Rocks of skills and

training.

Here's the downside of doing that (at least for me): I'm

going to wind up with a lot of athletes and coaches who are mad at me because

I've omitted their "Big Rocks" from those I emphasize. Mine have been learned from more than 30 years of reading research and observing

athletes of all abilities. Might my ideas of what the Big Rocks are change at

some point in the future? Sure. That's a possibility. My view of the world of

sport is always evolving. That's simply the way learning works. Those who

refuse to change their minds on anything, or even consider another way, are

doomed to a life without progress during which they become "dinosaurs." The people we tend to admire most are the free

thinkers who have come to change their minds on important topics and move on. Currently, one of the best at this is professor Tim Noakes, a sport scientist at the University of Cape Town. I had the great honor of meeting him while in South Africa recently. I'll tell you about him in another post. Time permitting.

In my next few posts I'll tell you about the Big Rocks when it comes to sport skills.

February 5, 2013

Pedaling, Tri-Novice and Runner's Trots

I get lots of questions from athletes in my email. Here are three recent ones.

Pedaling Technique

Q: While

riding this weekend and working on my form, I recall you saying not to lift on

the backstroke of the pedal, just un-weight it. May I ask why?

A: If you ride

steady (not climbing or sprinting) for a long time and try to pull up on the

pedals one of two things will happen. Either your hip flexors will tire very

quickly and you'll soon stop doing it or you will slow your cadence

tremendously simply because you can't maintain a high cadence and pull up at

the same time very easily. Even the pros don't do that. The slide I used to

illustrate this involved two national team riders. And if you recall even they

had a hard time getting their leg weight off of the recovery side pedal. When

climbing and sprinting you can pull up as the cadence is very low (climbing) or

the duration is very brief (sprinting).

Tri-Novice

Q: My name is

Matt I'm a 34 year old new cyclist.

I am just starting out.

Should I be

getting caught up with my posture , training programs, computers on my bike to

tell me rpm and speed.

What should a person just starting out concentrate on?

My goal is eventually an Ironman.

There is so much literature its frustrating.

I just wanna ride right.

I don't even know what these training ratios

mean.

Can you lead me to a beginner article or book or something please.

A: It is

confusing. When I started in the 1970s it was exactly the opposite—almost no

info at all, except from my training mates and an occasional magazine article.

I wrote a book about how to get started in triathlon called, “Your First

Triathlon.” I think it will help you figure out what’s important. To see it go

here. http://velogear.com/product/velopress-your-first-triathlon-80100-1.htm

Runner’s Trots

Q: I met you at a tri camp recently and

mentioned to you that I was having trouble with having to use the bathroom

about 20 minutes into my runs. It is very frustrating and to be honest, really

depressing. You said you may have some information that could help me. I would

appreciate any help.

A: What you're experiencing is not unusual

for runners but is rare in other sports. This may be because of the upright

position, jarring, and effect of gravity while running compared with other

sports. One study found that 25-30% of runners experience this. It’s been a

while since I read the literature on this topic, but there used to be only two

theories for what causes “runner's trots.” The first is intestinal

ischemia--decreased blood flow to the gut. There has not been much support for

this theory. The other is an increase in a hormone called motilin that

increases the movement of the bowels. This has been more widely accepted.

Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately), you can't do anything to directly

decrease motilin production. So what can you do? There's no science on this,

but here are suggestions from what Owen Anderson, PhD once suggested in Running Research News that may help.

* Know your own bowel patterns and habits and

adapt your running schedule to them.

* Avoid fiber in the 12 hours or so before

long runs with calories coming mostly from liquids.

* An hour or more before the run drink warm

fluids or a light meal to stimulate the gastric-colic reflex - food in the

stomach stimulates the large bowel to empty.

* Run a 10-15 minute loop at the start of

your run that brings you back past your house where you can use the bathroom.

* Train your bowels to empty first thing in

the morning out of bed by going straight to the bathroom. This may take weeks

to accomplish.

None of these are perfect, I realize.

Unfortunately, this is one of those things we need to figure out for ourselves

given our unique situations.

January 6, 2013

My Most Read Blog Posts of 2012

The following are the five most read posts on

my blog in 2012. There is only one that is new to the list. The others are

perennials.

1. A Quick Guide to Setting Zones (November, 2009)

This one moved up from #3 last year. If you

want to know how to set your heart rate, power, or pace zones for cycling, running

or swimming this should help. It takes you through the step-by-step process of

setting them up. It’s one I send readers to who have questions along these

lines.

2. Road Bike Posture (September, 2007)

This one was also #2 two

of the last three years - #1 in 2011. It discusses hip position in a seated

position on a road bike and shows examples of two riders, one with a position I

like and another that’s not quite as nice, but common.

3. Simplified Base Bicycle Training (December,

2008)

This was #5 last year.

It’s basic advice for the road cyclist in the winter months. Here I discuss

“Christmas Star” riders, training patiently, and the 3 abilities I have riders

work on at this time in the season.

4. Cleat Position (January, 2007)

This was the first blog

post I ever wrote and it continues to be one of the most read of all time. It is

slowly slipping down the list having been #1 or #2 for the last five years.

Here I discuss a midsole alternative to the traditional forefoot cleat position

for cycling shoes. There have been numerous comments posted to this blog by

readers, many of which describe their experience after moving their cleats.

Some with pictures. There have also been follow-up posts to this blog which you

can find by doing a search on “cleat position” on the home page www.joefrielsblog.com. And, yes, I

still use a midsole cleat and wouldn’t go back.

5. Why You Need a Power Meter (January, 2012)

This is the only new addition to the list.

And its popularity confirms what I find no matter where in the world I travel

to speak – more roadies, triathletes, mountain bikers and other cyclists are

adopting power-based training. Just a couple of years ago if I asked a crowd of

100 at one of my talks how many have power meters, two or three hands would go

up. Now it’s more like 25 to 30. There are probably lots of reason for this,

but contributing factors are more products available in the past year and

prices have remained stable or even come down a bit. In a few years I expect to

see well over half of an audience using power meters in addition to their heart

rate monitors.

On to 2013.

December 17, 2012

Five Fundamentals of Training

This is the time of year when most endurance athletes are

starting to think about and perhaps even plan for the coming season. That makes

it a good time to remember what’s most important when it comes to training for

peak performance – the basics. Here are five fundamentals I frequently remind

myself of when designing a training plan. There are certainly more than five concerns,

but I believe these are the most basic. I’ve linked each of them to a previous,

more expanded discussion in case you want to learn more.

1. Train with

moderation. Frequently doing extreme workouts that leave you tired for two or more or days

afterward do more harm than good. If you’re not recovered from most of your training sessions within 48

hours of their completion then you’re not training with moderation. This will

eventually catch up with you. Over the long term, the body responds best when the

adaptive changes required are slight. This is not to say you should never do

extremely hard workouts. In fact, it’s been shown that a block of several days

of pushing one’s limits results in a greatly increased level of fitness once

adequate recovery has also had time to remove the resulting fatigue. In my

Training Bible books I call this “crash” training. For most athletes this should not be done more

frequently than once every six weeks.

2. Train consistently.

If you follow the first fundamental in your training then this one probably won’t

require anything more of you. It will more than likely take care of itself. Moderation

usually results in consistent training. That means you don’t miss workouts. In

training, zero is a big number. If you have a lot of them in your training log

then you are giving away hard-earned fitness. Sometimes zeroes simply can’t be

avoided. With the holiday season now in full swing it’s likely you’ll miss a

workout or two. The good news is that it’s probably several weeks until your

first A-priority race of 2013. Zeroes in the last 12 weeks prior to your race significantly

degrade performance.

3. Make workouts

increasingly like the race. As the training year progresses your workouts should become increasingly like

whatever it is you are training for. What you’ve done in the last six weeks of build

period training before the race has a greater impact on how well you will

perform on race day than what you did in the first six weeks of base period training.

If those last six weeks were devoted to race-like sessions then you will be

ready to race well. If the workouts were unlike the race then you are giving

away performance. That seems apparent to most athletes and yet this time of

year I read of a lot of athletes following what they call a “reverse”

periodization plan. What this means is that their workouts are race-like in the

base period but not like the race at all in the build period – training becomes

less like the race as the season progresses. It’s reversed. That’s what true reverse periodization would be

(periodization is correctly based on what you are training for, not the

modulation of absolute intensity and duration). What I think most of them mean

is that they are training with high intensity now and will do more miles later

in the year. For events like an Ironman that is not reversed at all. That’s

becoming more race-like. But for a cyclist who does crits that could be

disastrous at the first race. Lots of miles done slowly in the last few weeks

before such a short, high-intensity race is a sure way to race poorly.

4. Intensity is the

key. Sports science hasn’t been around very long as compared with the other

sciences. There are only a few things we have definitively learned from it

about training. Perhaps the most common lesson is that the key to performance

is how you modulate the intensity (power, pace, speed, effort, heart rate) of

training. Performance is not

dependent on how many miles or hours you do in a week - volume. Unfortunately,

most athletes seem to think volume is the Holy Grail. For the experienced and

serious athlete, in their order of importance, the keys to performance are 1)

race-like workout intensity, 2) race-like workout duration, and 3) weekly

volume. In fact, #3 is a distant third. I think the reason volume is so revered

by athletes is that it’s easy to measure. Just add up the daily miles.

Intensity, on the other hand, is hard to quantify. Now I should point out that

this holds true only for the experienced and serious athlete – those who have

been training with a performance focus for three or more years. Novices do

benefit remarkably by focusing on duration and training frequency (volume).

That’s because any intensity – including very low – will prove beneficial for

them. They just need to get to the finish line.

5. Rest when needed. If you employ an appropriate training load you will frequently need to reduce

the stress of training in order for your body to recover and adapt. Continued

stress without rest eventually results in a breakdown of some sort –

overtraining, illness, injury, or mental burnout. How often you recover and

what exactly you do to enhance recovery is an individual matter. Some athletes

recover quickly, others slowly. Some recover with light exercise; others need a

day off. So there is no set pattern that all of us should follow. For some the

best plan is to have no plan – recovery on demand. Recover when your body says it’s time and until it’s ready to go again.

Unfortunately, many athletes are extremely poor at listening to their bodies

and are likely to disregard the common indicators of fatigue thus pressing

ahead in order to get their weekly miles number in the training log. These

folks need a plan for when to rest. Such a plan should include weekly, monthly,

and annual rest periods.

December 6, 2012

Periodization on Demand

Some time ago I wrote about recovery on demand. This is a method of training in which

recovery is not planned in advance, but rather done when the need arises. For

the athlete who is good at self-monitoring, this is a very effective way of recovering

as it maximizes one’s use of training time. Unfortunately, many athletes tend

to ignore their body’s signs of overreaching and with such a method would probably

press ahead without ever allowing time for recovery, eventually resulting in

full-blown overtraining.

“Periodization on demand” is a similar concept. Most

athletes think that periodization is a rigid system in which a training plan is

created which must be followed regardless of all other factors. My books have

probably given that impression as everything on the plan is quite detailed and time-specific.

I still think that’s a good idea as it provides a roadmap for where you are

going. It doesn’t, however, mean that you must follow it without change. There

can be several factors that require straying, such as illness, injury, periods

of mental stress, unusual demands on your time, and more. One such factor that

is seldom discussed is rate of adaptation – how quickly your fitness changes.

Physiologically, the purpose of training is stress the body

with some combination of workout intensity, duration and frequency causing it

to adapt. We call this adaptation “fitness.” The planning of periodization

assumes the body will achieve a given level of fitness at a given time by

following the plan. That may well be the case. Historically, the problem with

this assumption has been that there was little in the way of data to confirm

that the planned adaptation had occurred. That’s now changing due to

technology.

A power meter for cycling or a GPS for running has taken

some of the guesswork out of the measurement of adaptation. Such devices (there

are more to come) allow you to more accurately measure performance changes – if

you know what to measure. (I touched on this idea in my last blog post.)

Typically, in the Base period an endurance athlete wants to

improve aerobic endurance, muscular force and speed skill. The first two can be

measured using some combination of a heart rate monitor, power meter and GPS.

Speed skill is still difficult for us to measure in a field test. But expect

that to change when second generation power meters – yet to be released –

provide more analytical information on pedaling mechanics such as individual

leg contribution to power output and the range of effective force application

to the pedal per stroke. In the mean time, we can easily measure aerobic

endurance and muscular force adaptation.

I’ve previously written about the “Efficiency Factor” (EF)

as a way of gauging changes in aerobic endurance. It’s based on the simple concept that as aerobic

fitness improves, heart rate decreases at any given power output (or speed in

running) [Lucia, et al, Heart rate and performance parameters in elite

cyclists: A longitudinal study. Med Sci

Sports Exerc, 2000, 32(10):1777-82]. Or, to reverse that, if heart rate stays the same, over time, power (or running

speed) will increase as aerobic fitness improves. Heart rate by itself tells us

absolutely nothing about fitness. It must be compared with something to have

meaning.

This brings us back to the idea of periodization on demand.

The optimal way to train, I believe, is to frequently measure your adaptation changing your training only when it’s evident that fitness has plateaued at a

higher level or achieved a predetermined level. By doing this you take the

guesswork out of training and move on to a newer form of stress only when your

body says it’s time rather than when the plan changes. Again, this doesn’t mean

don’t plan. Follow it, but be willing to change it when the time is right. This

will usually require that you modify the plan going forward.

How about I give you an example of this from my own

training.

I use a block training form of periodization. With this method the focus of training during any given period (“block”) is

quite focused with generally only one or two aspects of fitness being

addressed. In block 1 this fall I focused on aerobic endurance as measured by

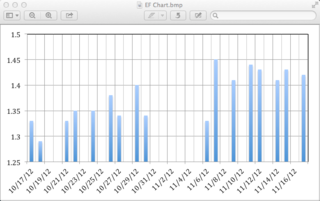

EF. The accompanying chart shows the progression over the course of four weeks

(Oct 17-Nov 17). During this time I did the same EF workout 17 times. This

involved warming up for 30 minutes and then riding one hour at a fixed aerobic

threshold heart rate in low zone 2 (120-125, in my case), followed by a

30-minute cool down. I used the same two courses for these sessions and the

same equipment with the workouts at about the same time of day. After the

workout I compared normalized power for that hour with average heart rate for

the same hour (NP/AHR). That produced a ratio that ranged from a low of 1.29 to

a high of 1.45. You can easily see the progression of EF in the chart. Only the

EF workouts are shown here (the blank days were missed workouts due to travel,

easy recovery rides, or a cycling camp from Nov 1-3).

By the middle of November it was obvious that my aerobic

endurance (as reflected in the EF ratio) had plateaued. Power had increased at

the same heart rate but was no longer rising. It was time to move on to the

next training block, which I am currently in.

The takeaway message here is not block training or aerobic

endurance training, but rather making changes to training when your body says

it’s time, rather than when the plan calls for it. Some day we’ll have software

that does such monitoring for you and suggests when it’s time to change your

training and what those changes might be. Until then you need to pay close

attention to that which is appropriate and measurable.

November 19, 2012

That Which Is Measured Improves

“Training is principally an act of faith.” –Franz

Stampfl

For serious athletes, the

purpose of training is to improve performance relative to a specific event – an

A-priority race. Throughout the Base and Build periods you should be looking for

indicators of improving readiness for this event. The closer you get to race

day, the more important it is to have some idea of how well you may do. Not

only does this build confidence, it also allows you to plan alternative

strategies and consider your tactical responses given certain race situations.

Not all workouts

throughout your preparation for the race are of equal value when it comes to

predicting race readiness. The Base period merely prepares you for the

challenging workouts of the Build period, which typically starts 10 to 12 weeks

prior to race day. The workouts in Base are seldom good predictors. The Build

weeks leading up to the start of the Peak period, or “taper,” is the most critical

time in the season. How your training goes during the 8 or 9 weeks of Build

largely determines how well you will race. Many of these Build sessions will

tell you if progress is being made.

During Build you should be

getting frequent feedback from training sessions that serve as indicators

– predictors – of how you will do on

race day. If all is going well these predictors should steadily improve so that

by the time you start to taper, 2 or 3 weeks prior to the race, there is little

doubt that you will be race-ready. The most important question is: What are

good predictors?

Below I’ve listed several

commonly used metrics – things that are measurable in training sessions – which

are often used to get this “how am I progressing” feedback. Some metrics are

better predictors than others. I’ve categorized them here as Weak, Moderate,

and Strong Performance Predictors. I primarily rely on Strong predictors

whenever possible. These are the most likely to give you reliable clues as to

how race day will go. But occasionally I’ll check a Moderate predictor just

because there hasn’t been a recent Strong indicator. Also, several Moderate

indicators all indicating the same trend may well be a strong predictor.

We may disagree on whether

or not a predictor is Weak, Moderate, or Strong. And, in fact, for some

athletes who are training for unique events, what is usually a Moderate

predictor may be Strong. Weak predictors are unlikely to make the leap all the

way up to Strong.

The metrics I’ve listed below

are not all-inclusive. They are the ones I commonly get from analysis software

such as TrainingPeaks or WKO+.

There are other personal metrics

I haven’t listed that for some may prove to be Strong performance predictors.

For example, depending on the athlete and the event terrain, watts per kilogram

(“w/kg”) or pounds per inch of height could be a Strong predictor. An athlete who is carrying excess weight

potentially will race better simply by dropping a few pounds/kilograms even if all

other metrics change. But for other

athletes weight may not be limiting performance at all. All that’s included below

are session-related data.

I frequently refer below

to “key workouts.” I define these as the most important sessions in a Build period training week.

They are usually either high intensity, long duration, or both. They generally fall into the category of

“advanced abilities” as described in my Training Bible books: muscular

endurance, anaerobic endurance, and sprint power. Race simulation sessions are

always key workouts. Other key sessions may be intervals, repeats, hill

training, or group workouts – whatever is critical to your preparation.

Weak Performance

Predictors

● Max or lactate

threshold heart rate

● Average cadence for a

workout or week

● Weekly miles/kilometers/hours/TSS

● Calories/kilojoules

expended/produced per week

● Feet or meters of

vertical ascent in a week (“VAM”)

● Time in heart

rate/power/pace/speed zones per week

Moderate Performance

Predictors

● Minimal heart rate

increase or power fade at aerobic event intensity – “Decoupling” (P:HR)

● Improving power/pace

relative to aerobic heart rate over time – “Efficiency Factor” (EF)

● “Performance Management

Chart” (PMC) data – “CTL,” “ATL,” and “TSB.”

● Distance/duration of

key workouts

● Event-specific pacing

of key workouts (“Variability Index”)

● Power Profile

comparisons

● Event-specific calories/kilojoules expended/produced in

key workouts

● Event-specific “Training Stress Score” (TSS) for key

workouts

● Previous performance in

the same event

● Time in power/pace zones

in key workouts

● “Rating of Perceived

Exertion” (RPE) relative to power/pace in key workouts

Strong Performance

Predictors

● Functional Threshold

Power/Pace (“FTP”)

● Peak power/pace for

event-critical durations (6 sec, 5 minutes, 30 minutes, 3 hours, or etc)

● The accumulation of

seasonal-best peak power/pace in the last few weeks of Build

● Event-specific power/pace for an event-specific duration

in key workouts

● Recent tune-up race

performance

Joe Friel's Blog

- Joe Friel's profile

- 91 followers