Joe Friel's Blog, page 3

November 16, 2016

Travel and Training

The emailed question…

Joe:

I have been training for triathlon since 2010 and I use the concepts of your book for planning my annual and weekly training. I have a fundamental question about that. I'm an executive and usually travel internationally at least once every two months. When it happens, I try to keep up my training at a hotel gym, but it's definitely not the same. The consequence is that it's difficult to keep the training as it is planned especially if it coincides with a high volume training week. Any suggestions?

FS

My reply…

Hi FS,

I understand your dilemma. I also travel quite a bit. I’m currently in the UK for 2 weeks and just returned from 3 weeks in E Europe. I’m gone, on average, about a week in every month. So I miss a fourth of my training. It isn’t so bad for running and swimming - usually. But cycling is nearly impossible during such trips. I’m sure you can relate to that. I’ve had to give up racing in the last three years mostly because of this. Before the last three years my travel was much less than one week per month on average. Then I was able to keep my training going ok if I tried to work everything - travel timing and training periodization - out well in advance of trips. The idea was to arrange it so that the travel time coincided with a recovery week. That worked usually pretty well. But not always. There really is no simple solution for my current level of travel when it comes to race prep. Missed workouts can’t simply be “made up.” Inconsistent training has a greater impact on performance than any other training errors one can make. I’m sorry to tell you that there is no easy solution. About all you can do is 1) try to make travel weeks coincide with rest weeks, 2) do as much as you can before leaving on the trip, 3) do all you can when on the road, and 4) get right back to it as soon as you return home. “Crash” training, which you can read about in my Training Bible, may prove helpful for #2. This post from some time back may also prove helpful.

Joe

October 31, 2016

What’s New About the All-New Triathlete’s Training Bible, 4th Edition

The following is a list of the biggest changes in the All-New Triathlete’s Training Bible. It really is “all new.” That’s not just a marketing ploy. The only thing that stayed about the same was the chapter topics. But even that changed a little. Writing it took me a year and half. That’s because it is almost twice the size of the original going from about 75,000 words in the first edition in 1998 to more than 140,000 now. I’m pleased with how it turned out. But the most important thing is that I hope you find it helpful for your training. That was my motivation for taking on such a huge task.

Here are the biggest changes.

The single most important change is that it is now easier to personalize your training with several periodization options for planning your season and workouts based on your unique needs and preferences. The original Training Bible offered only one way of doing everything. This alone makes the book a much more valuable reference when preparing for a triathlon.

The increasingly popular technologies of power- and pace-based training are discussed from various perspectives such as understanding how they can be used to improve race performance and how they can be blended into your seasonal planning.

The science of training has expanded considerably in recent years and you will learn how to apply the newest of the proven concepts to improve your race performance. This includes TSS-based training that is becoming quite popular among serious endurance athletes. And with good reason: It’s a much more effective way to gauge training load.

Skill development, especially for swimming, is one area where age group triathletes typically are overwhelmed with overly granular information—most of it intended for elite athletes. In this latest edition swimming skills are simplified to four basic movements that you can easily master and result in faster swimming immediately. Illustrations accompany the discussion of this. Bike and run skills are also included.

The strength program is updated to provide more options on how to best develop the functional strength to swim, bike, and run more efficiently and more powerfully. If you are time-constrained, as many triathletes are, you’ll find that not all strength training needs to be done in the gym. Much of it can be done in the sport without the need to lift weights. That greatly decreases the training time needed for those who are already very busy. For those who want to follow a gym-based strength program the exercises are updated to provide the most benefits for the time invested along with alternatives when time and energy allow for them. All of the options are explained with both the pros and cons along with illustrations.

The unique recovery needs of the busy and serious triathlete are described in detail to help you design a personalized plan for bouncing back after challenging training sessions.

The effective analysis of training data is critical to the continued improvement for the triathlete who has high aspirations for the sport. In this edition new ways of looking at training information are discussed with an eye to examining just the right workout data to more precisely train for high performance while limiting the time for analysis.

The swim, bike, run, and combined workouts in the appendices are expanded to include power and pace in addition to heart rate along with simplified explanations. Options for how they may be used in your training program are also included.

I hope you like my newest book. Please let me know what you think of it.

August 25, 2016

Muscle Cramps Question

Muscle cramps are one of the most perplexing problems endurance athletes face in training. I get several questions on what can be done about them every year. Here is such a question I just received.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Hi Joe,

I have recently purchased the Fast After 50 book and currently working through it and trying to come up with a training plan for an up and coming mountain race (running) > 4hrs in about 9 weeks. I have pretty good base fitness and have completed similar races already this season. I have one question. I suffer from cramps in long races, which I think is related to muscle fatigue, and basically I think the issue is that my race pace is much faster than the my long run pace I use in training. So the advice I have seen is that I need to train nearer my race pace. So would I make my long aerobic threshold run at a pace closer to my race pace? But if I do this will I lose the advantage of "teaching the body to use fat fuel" as part of my long run? So not too sure what to do but need come up with an approach to sort out the cramps.

Any feedback greatly appreciated.

Cheers,

Al

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Hi Al,

Thanks for your note. Good question. I agree with your conclusion - it’s probably neuromuscular fatigue that triggers leg cramps. Recently a couple of new products have come to market that also agree with that assumption and may offer a solution. I really don’t know if they work or not. They are based on research in the last few years showing that the nervous system reaction that causes cramps can be interrupted by stimulating nerves in the mouth. That research was done using pickle juice. I don’t recall what all of the new products are called but one of them is explained here.

The question you pose about training is also a good one. I’d suggest you need both - aerobic threshold long runs (easy - zone 2 using my heart rate system) and also race intensity (or slightly greater) runs. The latter would be done as tempo intervals such as 5- to 20-minute work intervals at just above race intensity (preceded by a warm-up and followed by a cool down). In my pace zone system this would probably be zone 3 for your type of racing. The recoveries between intervals would be about 1/4th as long as the preceding work interval. As an ultra-runner you would probably need to gradually increase to about 40 minutes (possibly to 60 minutes depending on your capacity for training) of total work interval time in a workout and probably do this once weekly in the Build period starting about 12 weeks before the race. These should be done on a soft but firm surface such as a track or trail. And if you mostly tend to cramp on hills then these intervals would probably best be done climbing. This should stimulate greater endurance at race pace and may help prevent fatigue and therefore cramps. But then, some athletes are so prone to leg cramps that they experience them even when it great shape. I’m afraid we just don’t know a lot about them, unfortunately.

You can read more about muscle cramps here, here, and here.

Good luck!

Joe

July 2, 2016

The 9-Day Training Week

Since I wrote Fast After 50 I’ve gotten lots of queries from aging athletes about how to set up nine-day training “week” as I describe in the book. If you’ve read it you know that I suggest this for athletes who find they aren’t recovering as quickly as they did when younger—which is most all 50-pluses. With the standard seven-day training week typically only two hard training days can be included due to the need for extended rest. Whereas when younger the athlete may have done three hard days in a week. So, essentially, by going to a nine-day week you can do more high-quality sessions throughout a training period and still get plenty of recovery time. The downside is that such a training schedule may not fit into your lifestyle, especially the common Monday through Friday workdays with weekends off. The first day you have to do a long training session and be at work by 8 a.m. you’ll fully appreciate the dilemma. So the nine-day week works best for over-50 athletes who are retired or have a flexible lifestyle.

Most of the inquiries I’ve gotten on how to do this have come from triathletes. Setting up a nine-day training week for a triathlete is a challenge. The bottom line for most triathletes is that it comes down to doing two high-intensity (HIT--near and well above lactate/anaerobic threshold or FTP) workouts in two different sports every third day with two light (very easy up to aerobic threshold which is about the bottom portion of HR zone 2 using my system) workouts on the two days in between. So the pattern could look something like this:

Day Workouts

1 run HIT

bike HIT

2 swim easy

run easy

3 bike aerobic threshold (or easy)

swim aerobic threshold (or easy)

4 run HIT

swim HIT

5 bike easy

run easy

6 swim aerobic threshold (or easy)

run aerobic threshold (or easy)

7 bike HIT

swim HIT

8 bike easy

run easy

9 bike aerobic threshold (or easy)

swim aerobic threshold (or easy)

The easy days following the hard days may be changed to one workout only on a given day to allow for even more recovery time if you find fatigue is quite high with two easy sessions on those days.

After 18 days (two of these weeks) it’s likely time for an extended period of recovery before starting the next period with a slightly increased training load. For most over-50 triathletes five days of such recovery is adequate, although some may be able to get by with four or even three. Notice that days 8 and 9 are already easy-session days (which could each be made into single workout days). By adding another three days of easy workouts (usually one each day) a five-day R&R period is ready to go. After that you start back over with Day 1.

Of course, this isn't meant to be a plan designed specifically for you or anyone else. It's just a sample of one way of doing it. I'm sure that with some thought you can come up with something that better fits your unique needs.

April 10, 2016

Cross Training and Performance

I often get questions about cross training. This is one that came in today from “Jack.” Most of it had to do with the athlete’s advancing age and having read my new book, Fast After 50. I’ve omitted all of that, but I’m most appreciative of his kind comments. Here is the focus of the email that gets at his question about cross training…

“I continue to train and ride, seeking the next sportive challenge. I’ve got my eye on the Assault on Mt. Mitchell in 2017 (May timeframe). That will be at age 53. I know, I know, I’m still a young pup. Anyway, I do have a question for you if I may. Although the book was quite extensive, I wish to know more about benefits of cross training. As I’m still working (Mon-Fri), I have a limited amount of time to spend training and therefore, devote almost all of it to cycling or the gym (two to three times per week). I don’t see a lot of room in my schedule for something else, but if there is a benefit, I’m willing to reconsider.”

And my reply…

Hi Jack,

Thanks for your note. And for your kind comments about my book.

Cross training is an interesting topic. Many do it who have “health” goals instead of “performance” goals. It’s great for health in part because the variety makes for high motivation and since many who are focused only on health are limited by lack of motivation for such a vague goal.

In answering your question I’m assuming that you are quite serious about cycling, as your email suggests, and that performance is your primary focus. If that’s the case then in order to reap a benefit from cross training the other activity you choose must overlap considerably with the physiological demands of cycling to prove beneficial. There are two broad categories for these demands—cardiorespiarory fitness and muscular fitness. Essentially, any mainstream endurance sport (swimming, running, cross country skiing, etc) will benefit the heart and lungs. This is actually not much of a challenge. The muscular system is a big challenge. If you’re not using the muscles in the same way they are used when on the bike then there is no significant muscular benefit. It may even be a waste of training time for achieving a high performance goal. For example, while you may use your legs quite a bit while running, the two movements are not even close in terms of the muscles. One relies on eccentric contractions of the calf muscles primarily (run) while the other calls for a great deal of concentric contraction from the quads primarily (bike). One of the best cross training activities for cycling has been shown in research to be weight lifting—especially heavy loads with low reps. But even then the movement must simulate cycling. Doing curls or even knee extensions won’t be of much benefit. Compound (multi-joint) strength-building exercises such as squats, step ups, and lunges come quite close to replicating the muscle activity on a bike.

The other issue is periodization. When should you do cross training activities and to what extent? There’s nothing in the way of research I’ve seen on this. My 35 years of experience as a coach and athlete tells me, however, that the closer you get to a targeted event, the more like the event your training must become. So the other side of this coin is that the farther away in time your event is, the less like the event your training can be. All of this suggests that cross training is best done many weeks and even months before the event. In common periodization-speak that would be the “base” period. But in the “build” period (last 12 or so weeks leading up to the event) you should make your training increasingly like the demands of the event. That implies cutting back on cross training in the build period. How much you do of it is determined by how lofty your performance goals are. For example, I can guarantee you that you won’t see a pro Tour de France GC contender running, swimming, or XC skiing in the last few weeks before the event starts. It would have to be an extremely unusual circumstance (perhaps an injury that precludes riding) for that to happen. And it would be a sure death knell for his race performance with such a lofty goal.

So bottom line is, some cross training is ok, especially well in advance of a high-goal event, but less so in the final few weeks.

February 27, 2016

The Weightlifting PMC, Part 2

In Part 1 of this two-part series on setting up a Performance Management Chart on TrainingPeaks for strength training I only got as far as describing why you should only have one combined chart for all sports reflecting your total fatigue. All of the other sport activities should have separate PMCs since fitness (CTL) and form (TSB) don’t significantly cross over between sports.

It isn’t really necessary to have a separate PMC for weightlifting, but knowing how focused some athletes can be on quantifying their training, I understand the request for how to do it. (It is possible to get carried away with tracking data. For example, I’ve also been asked if a stretching PMC would be informative. No, it wouldn’t.)

To have a useful PMC for strength training requires having a Training Stress Score (TSS) for every workout. This reflects how hard the workout was. For endurance sports the two components of TSS are workout intensity and workout duration. But in weightlifting, which isn’t an endurance activity, duration doesn’t play a role in the outcome. It’s strictly intensity that determines how hard the workout was. So you need to come up with a method of gauging only intensity for a weightlifting session.

That could be done simply with a rating of perceived exertion. But that’s quite subjective. Serious lifters do it by tracking “tonnage”—how much total load they lifted in a workout. Tonnage is based on the load lifted multiplied by the number of reps, times the number of sets. This is done for each exercise and then the totals are added together for a tonnage score.

An endurance athlete would do something similar—but with a new wrinkle to get TSS. After determining the tonnage for the session you’d have to decide how hard that was relative to what you normally do. If it was an average strength workout for you it could be given a TSS of 50. As the tonnage increases or decreases from the norm with each session you would assign a new TSS number either higher or lower than 50.

For example, you may find that your average weightlifting session is 3.5 tons. That would yield a TSS of 50 and would mean 14.2 TSS per ton (50 / 3.5 = 14.2). So a harder 4-ton session would be a TSS of 64. An easier 3-ton workout would have a TSS of 36.

Of course you must also realize that the fitness changes reflected in a PMC don’t say anything about what you’re fit for. If you’re a cyclist and spend all of your time running the PMC may say your fitness is quite high. But it’s doubtful that this would be reflected in your bike racing. In the same way, if you’re a runner and all you do in the gym when weightlifting is arm curls then you can’t expect to see much if any improvement in your running. Whatever you do in training, whether endurance training or weightlifting, must be specific to the sport for which you are training. But that’s a topic for another blog post.

February 17, 2016

The Weightlifting PMC, Part 1

I’ve been asked a few times recently how to set up a Performance Management Chart on TrainingPeaks for weightlifting. It’s that time of year when strength work is a major focus of training for many athletes. If you know what you’re doing in the gym it’s a way of developing greater muscular force for the coming season. That force can eventually be converted into power as your sport-specific speed skills should also be rounding into shape now. So it’s a good question.

Let me start by saying that if you do decide to track weightlifting that you do it with a PMC separate from your others. In fact, all PMCs should be for a single sport only—except for one. I’ll come back to that one shortly. So, for example, if you’re a triathlete and manage your performance in this way you might have four separate PMCs—one each for swimming, cycling, running, and weightlifting. If you’re a cyclist or runner you’d have two PMCs. These PMCs would primarily reflect what’s happening to your fitness (CTL), fatigue (ATL), and form (TSB) in each training mode.

But, as mentioned, I’d suggest you have one that shows only fatigue (ATL) for all stressful training activities. That would be five for a multisport athlete and three for single sport athletes. Why not combine them all into one chart showing everything you do? Because the fitness benefits are not equal across the board. Let’s say you’re a triathlete. You may do a lot of running, riding, and weightlifting, but never swim. How good do you think your swim fitness would be? Poor. Right? But a combined chart wouldn’t tell you that. It could say that, in general, your fitness is great. But specifically, it isn’t when it comes to swimming. A combined chart is simply too general. It doesn’t tell you what’s going on with each sport.

So what I’m suggesting is that fitness (and also form) is specific to a sport. You can get into great shape with other sports, but how great is the benefit for a sport you never do? That brings us to the topic of specificity of training that I’m not going to get into now. It’s covered in some detail in my Training Bible books.

The one PMC that combines everything stressful that you do, including strength training, is only effective for one of the three metrics—fatigue (ATL). You can do a hard bike ride today and be tired tomorrow no matter what that day’s activity is. So this would make up the fifth PMC for a triathlete who lifts weights and the third for a single sport athlete who also lifts.

That brings us back to the topic of charting weightlifting with a PMC. I’ll return to that topic in Part 2 of this post.

January 14, 2016

How Should I Train? It Depends...

I often get emails from athletes asking me how they should train as if there is a single answer that fits everyone. There’s only one answer I can give that fits everyone: It depends. It depends on all of the athlete’s unique variables such as sport experience, age, limiters, body type, training time available, and many more. The list is quite long.

With this in mind I’m going to try to answer that basic question. But before answering it let’s select only one of the variables from the above “it depends” list—sport experience.

At the most basic level there are three categories of athletes when it comes to experience—novice, intermediate, and advanced. There are several ways we could define these broad categories. For the sake of this discussion let’s say that novices are those in the first year in their sport, intermediates are in years two and three, and advanced athletes have been in the sport for more than three years.

Generally, each type of athlete needs to focus on training in a unique way. And since there are only four factors to consider in designing a workout plan—mode, frequency, duration, and intensity—the answers are pretty simple. (Let’s omit “mode” from the list since we can assume that in designing a plan you know what sport to work on.)

Of the three remaining factors, I believe novices should primarily focus on the frequency of their training. This has to do with how often they workout. Simply get out the door and do some easy workouts. Do this frequently. Question answered for novices.

Intermediates should focus mostly on duration—how long the workouts are since they need to build endurance and should have the frequency thing well-established by now. Question answered for intermediates.

Advanced athletes should focus on the intensity of their training. OK, this is a much tougher one to answer. It will take some head scratching. But before doing that let me point out that way too many advanced athletes never progress beyond the frequency and duration answers (taken together, we call these “volume”). They continue to believe that the key to their performance is how many hours, miles, or kilometers they put in during a week. They’re wrong. There’s a considerable body of research going back several decades showing that how fast (or slow) and advanced athlete trains has a greater impact on performance than how much volume they do in a week. And this holds true across all endurance sports.

This is not to say that volume is unimportant. So if both volume and intensity are important for the advanced athlete, how much more important is intensity? I answer this question with a ratio of the two factors. I propose that how well such an athlete performs on race day is determined 60% by the intensity of their recent training and 40% by their recent volume. Can I prove that? No. It’s just my opinion. And I realize it isn’t necessarily true for every athlete in every race. It’s just a ballpark estimate that helps me make decisions when assisting an advanced athlete in designing a training program. In other words, I know that if there’s a decision to be made about doing more volume or more intensity, the resolution is more likely to be on the side of intensity.

In my last post I proposed that an athlete should do a broad range of intensities throughout the year with only the distribution of that intensity varying. It’s based, in part, on the polarized 80-20 training research studies that have been gaining traction among athletes in the last 10 years or so, and, in part, on my personal experience. Several of you have noted that it’s a slight shift from what I’ve said in some of my books. And you’d be right. The times have changed. Training has changed. I’ve changed. (It seems that politicians are the only people who should never change their minds on anything.)

Some have written to me assuming the table in that last post was written just for them. It was written for everybody and for nobody. It was merely an example of how a fictitious athlete’s intensity distribution over the course of a season could look. It wasn’t necessarily a triathlete, cyclist, runner, or rower. The only thing I can say for sure is that it was for an advanced athlete, not a novice or intermediate.

January 10, 2016

Periodization of Intensity

There was a time when athletes believed that in the Base period one should only do long, slow distance. And in the Build period we were to primarily do high-intensity interval training. Those who believe this are now in the minority, I suspect. That’s only my opinion since there’s no way of knowing how many serious athletes still train with these “rules” in mind. I’m sure there are some, but I hear from them less every year, especially in the winter months, it seems.

The trend now, and perhaps the current majority point of view, is that there should be a wide variety of intensities throughout the training year with the mix varying by period. The intensities I’m talking about here run the gamut from very slow and easy, all aerobic workouts to extreme top end, anaerobic capacity repeats—and everything in between. That means training volume at any given time in the season includes several intensities. All that changes is how much of each intensity is included in a given period.

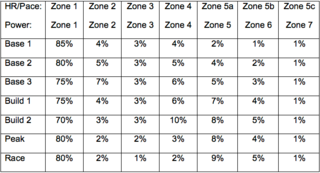

So what does that mean when it comes time to plan a season? Well, we might think of this in terms of the seven zones in my heart rate and pace-based training method (as found here and in The Triathlete’s Training Bible) or Dr. Andy Coggan’s with his seven power zones (also at the above link and in Training and Racing with a Power Meter). While a heart rate zone does not translate directly into a pace or power zone (see here for an explanation of why not), a hypothetical endurance athlete who is preparing a two-hour race might train with intensity distributions throughout the season something like what is suggested in this table (click to enlarge)…

Now please keep in mind that this table is not supposed to represent how you—or anyone else, for that matter—should train in the build up to a race. It’s just a hypothetical example. The intensity is a little too perfectly distributed to be how anyone would train in the real world. It might vary considerably from what you see here due one's individual limiters, the weather, and individual lifestyles, not to mention the type of event for which one is training (Olympic-distance triathlon, bicycle road race, half marathon, etc). The purpose here is simply to show that there is at least some time spent in each zone throughout the season. It isn’t all or nothing determined by the Base and Build periods.

Some old-time coaches and athletes might complain that the inclusion of anaerobic training (zones 5a, 5b, 5c and 5, 6, 7) “nullifies” the benefits of aerobic training in the Base period. I’ve looked for research showing this to be the case for more than 20 years and have never found one such study. I seriously doubt there is one (if you know of such research please let me know). I’ve also never seen an athlete I’ve trained experience a noticeable loss of aerobic fitness from having done “too much” training above the anaerobic threshold.

The bottom line here is that there are no known downsides to doing at least a small amount of training in each zone throughout the preparation for a race. And, in fact, such a variety may even produce better race fitness over the course of a season as there is no need to “start from scratch” in building a specific type of fitness in the initial stages of a new training period.

December 5, 2015

Managing Training Using TSB

I’ve posted a few times here on how you can use the Performance Management Chart to manage your training with topics on CTL (“fitness”), ATL (“fatigue”), and TSB (“form”). If you are unfamiliar with these three TrainingPeaks terms you can find brief definitions here. A topic I’ve never written about before is how you can use TSB on the PMC to manage your training throughout the season to achieve what you are aiming for at any given time.

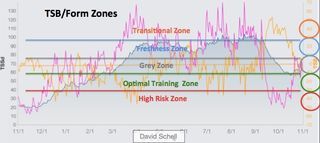

The accompanying chart (click to enlarge) for Dave Schell, a TrainingPeaks employee, shows his training for an entire year. The jagged lines are CTL (blue), ATL (fuchsia), and TSB (yellow). What I want to focus on with his chart is TSB. That’s a proxy for “form,” or in another word, “freshness.” Basically, it has to do with race readiness. As the yellow TSB line falls on the chart Dave is becoming less fresh—he’s losing form. As the line rises, Dave is becoming more fresh—“coming into form.” When TSB is above the dashed yellow line in the middle of the chart Dave is “on form.” But if that line gets too high, as it was at the end of his race season around 9/1 to 10/1 on the right end of the chart, then he is very fresh, but has lost so much fitness (CTL dropped precipitously) that he is certainly not ready to race.

All of this is how TSB is typically used to monitor training. But I’d like to show you another way to think about TSB—and help you manage your training.

On the right side of the chart is the yellow TSB legend. Notice that there’s a “0” (zero) in that legend about in the middle. That’s the balance point for TSB. Above that is positive TSB/form ("fresh") and below it is negative TSB/form ("not fresh"). The more positive (the higher above 0), the fresher Dave is. The more negative (dropping below 0), the more tired Dave is.

Now notice the circles also on the right side legend. I’ve put circles around five, numerical “TSB zones.” Each of these represents a zone indicating a stage in the training process. Those colored zones are also indicated by similarly colored straight lines across the chart. I’ve put a title in each zone. I’ll walk you through each of them.

Let’s start at the bottom with the red “High Risk Zone.” Back on the right side legend again you can see this zone is below -30 TSB. I call it “High Risk” because if you spend much time here you will create great fatigue and are flirting with extreme overreaching that would likely become overtraining if continued for too long. Notice that Dave was in this zone several times throughout his season, but only one episode was long enough to be risky—in the last few days of March and early April. This represents a period of very hard training for Dave. In early April he backed off by doing easier training and his TSB began to rise indicating he was moving toward freshness. That’s exactly the way you should react when you find yourself deep in the High Risk Zone. This is the time to reduce training so that you exit the red zone quickly. How quickly you need to react depends on your unique capacity for training stress. It’s usually best to stay there no more than a few days at a time. You may only get into this zone two to four extended times in a season with an R&R break ending each of them.

The green circle and horizontal line mark the “Optimal Training Zone.” On the TSB legend the green circle covers the range of -10 to -30. Notice that Dave is spending quite a bit of TSB time here throughout the season. That’s good because, as the title indicates, this is typically when the most effective training occurs.

Going up the legend, the grey circle (-10 to +5) and grey line indicate what I call the “Grey Zone.” You don’t want to spend too much training time here because there’s not much happening that will improve fitness. You’re sort of at a plateau in training. This is typically the zone you are in during a rest and recovery week, when tapering for an A-priority race, and when returning to hard training following an extended break.

The “Freshness Zone” (blue) extends from +5 to +25. Some place in this zone is probably where you should be on race day when coming into form for an A race or at the end of the season when taking an extended break (the “Transition” period). You can see that Dave’s yellow TSB line is in this zone just a few times for races and when entering end-of-season recovery (about 9/1 to 10/15). Freshness is fully realized when in this zone, but how high an athlete may want to be here on race day varies. Some athletes race better when high in the zone around +20 to +25, and others when low in the zone at about +5 to +10. That’s one of thing you can only determine from trial and error.

The orange “Transitional Zone” is typically only entered at the end of the season when in the Transition period. The only other times you may unfortunately find yourself in this zone is when you have an extended break due to injury or illness. In other words, this is the zone of little to no training. It’s very safe, but fitness is also very low.

So that’s it. I should also point out that the numerical ranges I’ve described here for each zone will work for most athletes, but there are many outliers for whom the zones are either too high or too low. Adjustments should be made based on experience. This is just another reason why having a smart coach is a good idea. He or she can manage all of this—and a lot more—taking the burden off of you.

Joe Friel's Blog

- Joe Friel's profile

- 91 followers